1. Introduction

It has been estimated that in 2022, 6.5 million people in the US aged 65 years or older suffered from Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and an additional 13.1 million had mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [

1,

2]. Given the aging of the population, the prevalence of these disorders is expected to rise [

1,

2], making identification of modifiable factors associated with maintenance of cognitive function a public health priority.

Numerous studies examining lifestyle factors generally report decreased risk of AD and better cognitive function with higher educational attainment, light to moderate alcohol consumption, and higher levels of physical activity, cognitive engagement, and social support (see for example, [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]). Other studies investigate dietary factors, including macro- and micronutrients, and generally report that low saturated fat consumption, and high fruit and vegetable consumption were associated with decreased risk of AD and less cognitive decline (see reviews, [

3,

11,

12]). Additionally, other studies report that choline, and carotenoids such as lutein and zeaxanthin are associated with protective effects for cognitive function [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Eggs are low in saturated fat and have high levels of choline, carotenoids and other micronutrients, but few studies directly investigate the association of egg consumption with cognitive function.

Previous cross-sectional studies report either a protective effect or no association between egg intake and cognitive function. For example, higher egg consumption was associated with better cognitive function in a study of 317 Korean children aged 6-18 years [

19], and in a study of 178 institutionalized men and women from Madrid aged 65 years and older [

20]. Additionally, a study of 404 Chinese adults aged 60 years and older found that higher egg consumption was associated with decreased odds of MCI [

21]. However, another study of 160 men and 204 women in China aged 90-105 (mean=93 years), found no significant difference in frequency of egg consumption between those with and without MCI [

22].

Only two previous studies examined the longitudinal associations of egg consumption with cognitive function but yielded conflicting results. One study of a subsample of 480 Finnish men aged 42-60 years when enrolled in the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study, found that higher intake of eggs at baseline was associated with better performance on the Trail Making Test (a measure of executive function), and a verbal fluency test when cognitive function was assessed 4 years later [

23]. However, a study using representative sample of 3,835 US men and women aged 65 years and older followed over a 2-year period, reported egg consumption was not associated with measures of cognitive performance, including working memory, executive function and global mental status [

24]. Both studies had relatively short durations between the assessment of egg intake and the assessment of cognitive function, and either did not include women or did not stratify analyses by sex.

The purpose of this study is to examine the prospective association of egg consumption with multiple domains of cognitive function in a sample of 1,515 older, community-dwelling men and women followed an average of 16.3 years.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Between 1972-1974, 6,339 individuals, representing 82% of Rancho Bernardo, a predominantly Caucasian, middle-class, southern California community, were enrolled in a study of heart disease risk factors. These individuals were followed ever since with almost yearly mailed questionnaires and periodic clinic visits. A total of 2,212 individuals representing 80% of the surviving, community-dwelling participants attended a follow-up clinic visit in 1988-91 when cognitive function tests were first administered. After excluding those under 60 years of age (N=365), those missing all cognitive function tests (N=9), and those missing egg intake information from 1972-74 (N=323), there remained a total of 1,515 individuals (617 men and 898 women) who form the focus of this analysis.

This study was approved by the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Human Research Protections Program. All participants were ambulatory and gave written, informed consent prior to participation.

Procedures

A self-administered questionnaire in 1972-74 was used to obtain information on egg consumption. Specifically, participants were asked to write in the answer to the question, “How many eggs do you eat per week? (visible eggs only)”. Information on demographic characteristics including age, sex, education and cigarette smoking history were obtained. Participants were queried about their history of heart attack, (no/yes), stroke (no/yes), diabetes (no/yes), high blood pressure (no/yes), along with whether they had taken any medication prescribed by a physician in the past week for high blood pressure (no/yes), high blood sugar (no/yes), and high cholesterol, triglycerides or blood fats (no/yes). Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured in the participants’ left arm after they had been seated quietly for five minutes using a regularly calibrated standard mercury sphygmomanometer. Weight and height were measured with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes, enabling use of body mass index (BMI; weight(kg)/height(m)2) as an estimate of obesity. A blood sample was obtained by venipuncture after an overnight fast. Glucose, total cholesterol and triglycerides were measured in a CDC certified laboratory.

At the 1988-91 research clinic visit, trained personnel administered 12 cognitive function tests individually to each participant. These tests were selected with help from the UCSD Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) based on demonstrated reliability and validity [

25,

26]. Higher scores indicate better cognitive function except where noted. Cognitive function tests administered were as follows:

The Buschke-Fuld Selective Reminding Test [

27] assesses verbal episodic memory, and short- and long-term storage and retrieval of spoken words. Ten unrelated words were read to participants at a rate of one every 2 seconds for a maximum of six trials. Immediately after, participants were asked to recall the entire list. They were reminded of any words missed and asked to recall the entire list again. This procedure was followed for six trials. Points were based upon the number of items and trials needed for recall. Measures of long- and short-term memory and total recall were obtained. Higher scores on short-term memory indicate poorer performance because they reflect words not successfully encoded into long-term store.

The Heaton Visual Reproduction Test [

28], adapted from the Wechsler memory Scale [

29], assesses memory for geometric forms. Three stimuli of increasing complexity were presented one at a time, for 10 seconds each. Participants were asked to reproduce the figures immediately to assess short-term memory and after 30 minutes of unrelated testing to assess long-term memory for geometric forms. Afterwards, participants were asked to copy the stimulus figures, which assesses visuospatial impairments. Thus, three scores were obtained: immediate recall, delayed recall and copying.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

30,

31], a test of global function, assesses orientation, registration, attention, calculation, language, and recall. Total MMSE scores can range from 0-30; persons with dementia usually score <24. Two MMSE items were analyzed separately; counting backward from 100 by sevens (Serial 7’s), which assesses calculation, and spelling the word “world” backwards (World backwards) which assesses attention, both of which are measures of executive function. Maximum score was 5 for each.

Two items from the Blessed et al. information-memory-concentration test [

26] assessed concentration by having the participant name the months of the year backward, and assessed memory by asking participants to recall a five-part name and address following a 10-minute delay. Two points were given for correctly naming the months of the year backward and one point for each part of the name/address recalled correctly. Maximum score was 7.

The Trail-making Test, part B (Trails B), from the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery [

32], is a test of executive function that assesses visuomotor tracking and mental flexibility. Participants scan a page containing letters and numbers within circles and were asked to connect numbers and letters in ascending order, alternating between numbers and letters (e.g., 1 to A to 2 to B to 3 to C and so on). A maximum of 300 seconds was allowed; performance was rated by time (seconds) required to finish the test; higher scores indicate poorer performance.

Category Fluency [

33] assesses semantic fluency and verbal memory. Participants were asked to name as many animals as possible in 1 minute. The score is the number of animals correctly named; repetitions, variants (e.g., dogs after producing dog), and intrusions (e.g., apple) were not counted.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Education was dichotomized as high school or less vs. some college or more. Cigarette smoking status was dichotomized into current smoking (no/yes). Because of skewness, triglycerides were presented as medians, with values logged for testing purposes. Means and distributions for continuous variables, and rates for categorical variables were calculated. Comparisons of variables by sex were performed with independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables. Because of the significant sex differences found, all further analyses were sex-specific. Sex-specific comparisons of characteristics by categorical egg consumption was performed with analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Potential confounders of the egg consumption--cognitive function association were identified based on being known confounders in the literature, and based their associations with both egg intake and cognitive function in this study. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the associations of egg consumption as a continuous variable with cognitive function after adjustment for potentially confounding covariates. Analyses were repeated after restriction to those aged <60 years at enrollment to determine the long-term effect of egg intake at middle-age on cognitive function.

Cognitive function scores were also analyzed as categorical outcomes using cutoffs indicative of poor performance recommended by the UCSD ADRC. Cutoffs were available for five tests: Buschke Selective Reminding Test long-term memory (≤13), Heaton Visual Reproduction Test immediate recall (≤7), MMSE (≤24), Trails B (≥132) and Category Fluency (≤12). However, because <1.5% scored below the Buschke long-term recall cutoff and ≤3.2% scored below the Heaton Visual Reproduction Test cutoff, results are presented only for the MMSE, Trails B, and Category Fluency. Sex-specific logistic regression analysis was used to examine the associations of egg consumption with odds of poor cognitive function on the MMSE, Trails B and category fluency after adjustment for potentially confounding covariates.

In sensitivity analyses, comparisons of baseline characteristics between those who came to both visits and those who did not attend the 1988-91 clinic visit were performed with independent t-tests, Wilcoxon, and chi-square analysis to examine survival bias.

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC); all tests were two-tailed with p-value≤0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

In this sample, average length of follow-up was 16.3±0.8 years (range=13.9 to 19.1 years). Comparisons of characteristics at 1972-74 (

Table 1), showed that men had significantly higher body mass index (p<0.0001), glucose (p<0.0001), triglycerides (p<0.0020), education (p<0.0001), and rates of self-reported diabetes (p=0.0072), but lower total cholesterol (p<0.0001) and rates of current smoking (p<0.0060) than women. There were no significant differences between men and women on age at 1972-74 (means=59.2 and 59.0, respectively p=0.5626). Significant sex differences were observed on almost all cognitive function tests (

Table 1). Men performed significantly better than women on the Heaton immediate and delayed recall tasks, serial 7’s, Trails B, and category fluency, but worse on Buschke total recall, long-term recall, short-term recall, the MMSE, world backwards, and the Blessed items.

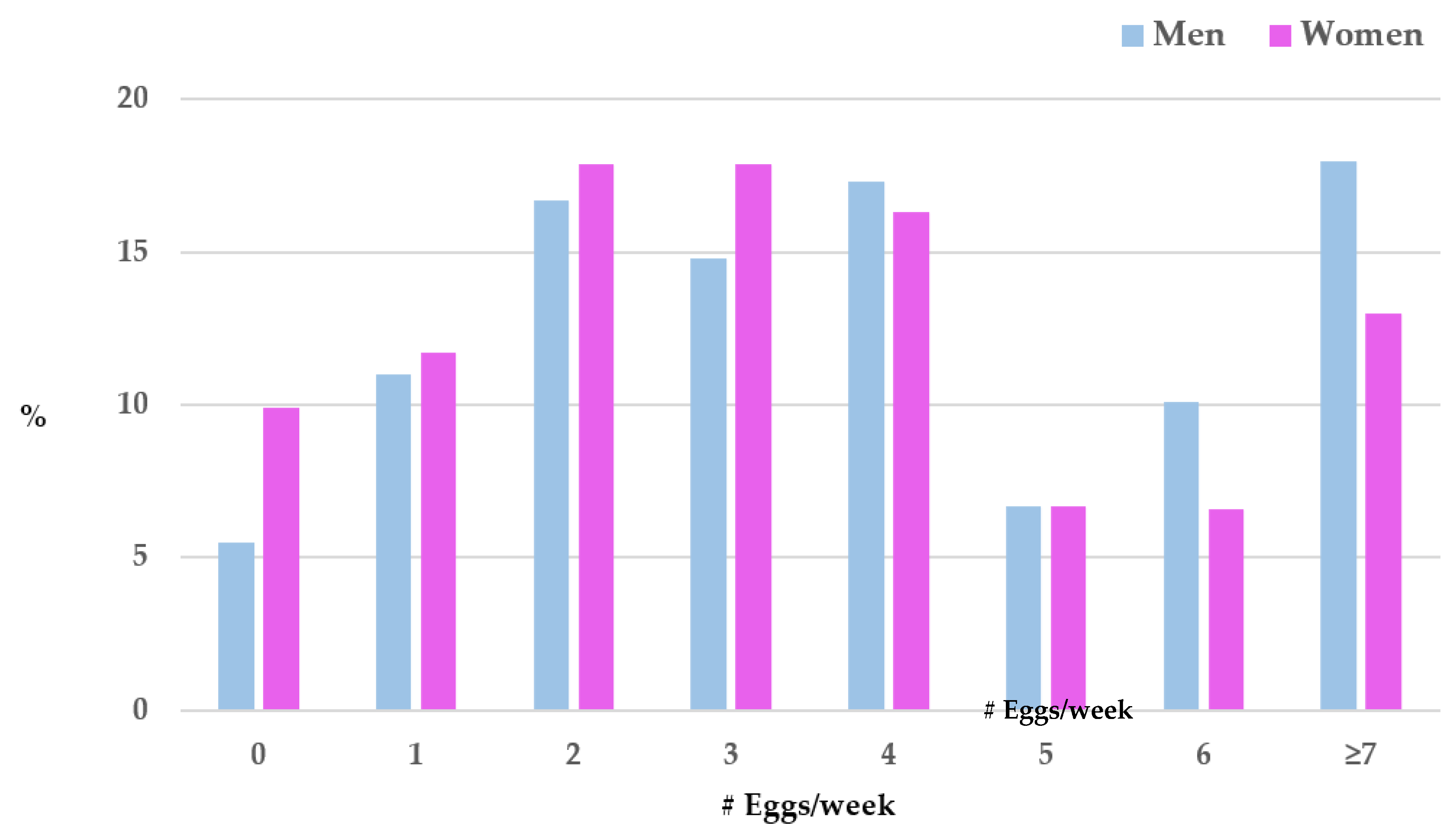

In both men and women, egg intake ranged from 0-24/week. However, men consumed significantly more eggs per week than women (mean=4.2±3.2 in men vs 3.5±2.7 in women, p<0.0001). Rates of egg consumption per week varied by sex; greater proportions of men consumed eggs at the higher levels whereas greater proportions of women consumed eggs at the lower levels (see

Figure 1). For instance, in men, 5.5% consumed no eggs/week, and 18.0% consumed 7 or more eggs/week whereas in women, 9.9% consumed no eggs/week, and 13.0% consumed 7 or more eggs per week. Because of the significant sex differences in demographic characteristics, egg consumption per week, and cognitive function, all further analyses performed were sex specific.

For both sexes, unadjusted comparisons of characteristics by egg consumption (

Table 2), showed that those who consumed 7 or more eggs/week had lower mean cholesterol and triglycerides, although differences overall were not statistically significant (p’s>0.05). Rates of cholesterol lowering medication use were lowest among those consuming 7 or more eggs/week but were too low overall for valid statistical comparisons. Mean glucose levels were lowest for those consuming 4 or 5-6 eggs/week in both men (p=0.0465) and women (p=0.0643). Other differences in characteristics by categorical egg consumption are shown in

Table 2.

Unadjusted comparisons of cognitive function test scores by categorical egg consumption (

Table 3) showed that among men, those at higher levels of egg intake performed better on Buschke total (p=0.0527), long-term (p=0.0316) and short-term recall (p=0.0391), and the MMSE (p=0.0018), but worse Trails B (p=0.0194). Men who consumed 2 or 3 eggs per week performed worse on the Heaton copying task and on the Blessed items than those with higher or lower egg intake (p’s<0.05). Among women, those at higher levels of egg intake performed better on Buschke total recall (p=0.0115) and long-term recall (0.0206), Heaton immediate (p=0.0220) and delayed (p=0.0021) visual recall tasks. Women who consumed 7 or more eggs/week also performed better on Trails B and category fluency than those who did not consume eggs (p’s<0.05).

Among men, age and education adjusted regression analyses (

Table 4) showed that egg intake as a continuous variable was significantly associated with better performance on Buschke total, long-term, and short-term recall. These associations remained significant after additional adjustment for smoking, cholesterol level, use of cholesterol lowering medications, and history of heart attack and hypertension (B=.22, p=0.0415 for Buschke total, B=.33, p=0.0245 for long-term recall, and B= -.12, p=0.0494 for short-term recall). Thus, each additional egg consumed per week was associated with an increase of .22 on total recall score, .33 on long-term recall score, and -.12 (indicating better performance) on short-term recall score. No other associations were observed between egg intake and cognitive function in men. Among women, no significant associations were observed between egg intake and scores on any of the cognitive function tests both before and after adjustment for covariates (p’s>0.05).

Restricting analyses to those aged younger than 60 years at enrollment (

Table 5) showed that greater egg consumption as assessed in middle-age was associated with somewhat better performance on most cognitive function tests approximately 16 years later, with significantly higher scores on the Heaton copying subtest (B=0.061, p=0.0352), and the MMSE (B=0.058, p=0.0154), but worse scores on Trails B (B=1.749, p=0.0110) for men. Among women, greater egg consumption in middle-age was associated with significantly higher scores on category fluency (B=0.145, p=0.0464).

Results of logistic regression analyses examining the adjusted odds of categorical poor performance on cognitive function tests by egg consumption are shown in

Table 5. For both men and women, egg intake per week was not significantly associated with increased odds of poor performance on the MMSE, Trails B, or category fluency.

Sensitivity analyses examining the possibility of survivor bias showed that compared to participants who attended both enrollment and follow-up visits, those who only attended the enrollment visit were significantly older (p<0.001), had higher total cholesterol, triglycerides (p’s <0.001) and higher rates of cholesterol lowering medication use(p<0.001). However, there were no differences in education or rates of current smoking (p’s>0.10).

4. Discussion

In this cohort of community-dwelling individuals with cognitive function assessed more than 16 years after egg intake assessment, analyses showed that that for men, greater egg consumption was associated with small, but significantly better performance on total recall, short-term, and long-term memory. Specifically, each egg consumed per week was associated with increases of .22 on total memory and .33 on long-term memory, and decreases of .12 (indicating better performance) on short-term memory. These associations were independent of age, education, cigarette smoking, cholesterol level, use of cholesterol lowering medications, and histories of heart attack and hypertension, and adjusting for these covariates did not alter the associations. No other differences in cognitive function were observed for men, and no association of egg consumption with cognitive function were observed in women. Although differences were small, analyses restricted to those younger than age 60 at enrollment suggested that egg consumption in middle-age may be associated with better performance on some cognitive function tests later in life. Egg consumption was not related to odds of impaired cognitive function in either men or women.

Results of this study are in accord with those from a subsample of 480 Finnish men from the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study which found significant prospective associations of egg intake with cognitive function [

23]. However, that study reported significant positive associations between egg intake and scores on Trails A and verbal fluency after 4-years of follow-up [

23], whereas the current study found positive associations with total, short-term, and long-term recall in men after a longer, 16-year follow-up.

Results of this study disagree with those of Bishop and Zuniga who used a nationally representative sample comprised of 3835 men and women aged 65 and older from the Health and Retirement Study and the Health Care and Nutrition Study and found that egg intake assessed in 2013 was not associated with any measure of cognitive function over a two year period [

24]. However, in that study, cognitive function was assessed with a telephone interview whereas the current study involved an in-person, face-to-face assessment. Additionally, unlike the present study, that study did not stratify analyses by sex, possibly obscuring differences in associations for men and women. Guidelines to limit dietary cholesterol were first suggested by the American Heart Association in 1968, and then widely adopted by other agencies by 1995 [

34]. Thus, unlike the present study which collected egg intake data in 1972-74 at a time temporally close to initiation of these guidelines and potentially prior to their widespread adoption, Bishop and Zuniga assessed egg intake at a time when guidelines limiting egg and cholesterol intake were widely known and had existed for over 40 years. Egg intake in the Bishop and Zuniga study [

24] was much lower than in the present study-- only .34/day on average or 2.4/week compared to 3.5/week in women and 4.2/week in men observed here. This coupled with the relatively short follow-up may have made it difficult to detect associations.

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to examine associations of egg intake with cognitive function separately for men and women. Although some associations were observed in men, no associations were observed between egg intake and any of the cognitive function measures in women. It is possible that this lack of observed associations in women may be due to fact that despite having a similar range in the number of eggs consumed per week (0-24), greater proportions of men than women consumed eggs at the higher levels, and the smaller variability of egg consumption in women may have led to attenuated, non-significant associations.

In this study, we found evidence that egg consumption in middle-age may be associated with somewhat better cognitive function later in life. This novel finding and warrants further studies with larger samples of middle-aged and younger adults as it suggests a potential long-term impact of egg consumption for cognitive health.

This study, which had the longest duration between assessments of egg consumption and cognitive function, also found no associations between egg intake and categorically defined impaired cognitive function in either men or women. These results are in accord with a cross-sectional study of 870 community-dwelling Chinese men and women aged 90 and older, which found no association of egg intake with mild cognitive impairment based on MMSE score [

22]. However, our results are in contrast to those of a cross-sectional study of 404 men and women aged 60 and older in Beijing which reported that higher daily intake of eggs was associated with lower odds of mild cognitive impairment [

21].

It is biologically plausible that egg consumption is associated with beneficial effects on cognitive function. Eggs are an excellent source of protein and amino acids as well as nutrients and bioactive compounds. Eggs contain high levels of choline, a nutrient needed to produce acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter important for memory [

35]. In 1,391 adults aged 36-83 years from the Framingham Offspring Study, those with higher choline intakes had better verbal and visual memory [

36]. Eggs are also a good source of lutein and zeaxanthin, carotenoids that are important for cognitive function in the elderly [

37,

38]. A study of 78 octogenarians and 220 centenarians from the Georgia Centenarian Study showed that higher serum and brain concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin were associated with better performance on measures of memory, executive function and language [

38]. The protective effect of these carotenoids for cognitive function may be due to anti-oxidant or anti-inflammatory actions in the brain [

38]. Small clinical trials of 12-15 institutionalized individuals with AD reported that those given lutein and zeaxanthin had less progression of AD [

39]. Additionally, a small clinical trial of 51 older community dwelling adults reported that those given 12 mg of lutein and zeaxanthin had improved attention, cognitive flexibility and performance on other tests [

40].

Several limitations of this study were considered. Rancho Bernardo Study participants are predominantly Caucasian, well-educated, and have good access to medical care, which may limit generalizability. Given the number of statistical tests performed, the possibility that observed differences were due to chance cannot be excluded. However, all comparisons were a priori attempts to understand the contradictory literature on egg consumption and cognitive function, and the sex-specific associations with egg consumption were consistently observed for the same tests. We also cannot exclude participation bias, as in any sample of older adults where those with the most impaired cognitive function do not participate. We also cannot exclude survival bias where the oldest and least healthy may have died prior to participation. However, these biases would yield conservative estimates of any true association. Finally, no brain imaging studies were performed at this visit, so we are unable to relate differences in cognitive function with egg consumption to underlying changes in the brain.

This study has several strengths however, including the large sample size of community-dwelling seniors and use of a battery of standardized measures allowed measurement of multiple domains of cognitive function. The long follow-up and focus on those aged 60 years and older at cognitive assessment assured variation in cognitive function. Additionally, the baseline assessment of egg intake was relatively close temporally to the introduction of AHA guidelines suggesting limitation of egg and dietary cholesterol intake and prior to the widespread use of statins, limiting potential bias from these factors. Finally, the homogeneity of this cohort is also an advantage as there is less confounding of test performance due to socio-cultural differences, education, or access to health care.

5. Conclusions

Results of this study are reassuring and suggest that there are no long-term detrimental effects of egg consumption on cognitive impairment or on multiple domains of cognitive function, there may be beneficial effects for verbal episodic memory for men. Results also suggest that, greater egg intake in middle-age is associated with better cognitive performance at older ages. Eggs represent a readily available, relatively inexpensive source of protein and other nutrients that are beneficial for cognitive health as well as overall health. Future studies with large samples of men and women of are needed to confirm the sex-specific associations observed here, and to examine associations in large samples of younger and middle-aged individuals followed across the life-span. Additionally, brain imaging studies are needed to determine if differences in cognitive function with egg consumption are related to underlying brain changes.

Author Contributions

DK-S was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, data analysis plans, writing—original draft preparation, project administration, and funding acquisition. RB was responsible for data analysis plans, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the American Egg Board’s Egg Nutrition Center. Data collection was originally funded by NIA grants AG07181 and AG02850, and NIDDK grant DK-31801 from the NIH. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. Both authors contributed to this work and meet the criteria for authorship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Protections Program of the University of California San Diego (IRB #191902 January 22, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved this study at the time of data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement 2022;18. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf accessed 10 February 2023.

- Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, McAninch EA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060) Alzheimers Dimen 2021;17:1966-1965. [CrossRef]

- Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, Bowen PE, Connolly ES Jr, Cox NJ, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the Science Conference statement: preventing Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:176-181. [CrossRef]

- Hersi M, Irvine B, Gupta P, Gomes J, Birkett N, Krewski D. Risk factors associated with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of the evidence. Neurotoxicology 2017;61:143-187. [CrossRef]

- Xu W, Huifu W, Yu W, Tan C, Li J, Tan L, Yu JT. Alcohol Consumption and dementia risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:31-42. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y-R, Xu W, Zhang W, Wang H-F, Ou Y-N, Qu Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors for incident dementia and cognitive impairment: An umbrella review of evidence. J Affect Disord 2022;314:160-167. [CrossRef]

- Reas ET, Laughlin GA, Bergstrom J, Kritz-Silverstein D, McEvoy LK. Physical activity and trajectories of cognitive change in community-dwelling older adults: The Rancho Bernardo Study. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2019;71:109-118. [CrossRef]

- Reas ET, Laughlin GA, Bergstrom J, Kritz-Silverstein D, Richard EL, Barrett-Connor E, McEvoy LK. Lifetime physical activity and late-life cognitive function: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Age Aging 2019;48:241-246. [CrossRef]

- Reas ET, Laughlin GA, Bergstrom J, Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E, McEvoy LK. Effects of sex and education on cognitive change over a 27-year period in older adults: The Rancho Bernardo Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;25:889-899. [CrossRef]

- 10. Penninkilampi R, Casey A-N, Singh MF, Brodaty H. The association between social engagement, loneliness, and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis J Alzheimer’s Dis 2018:66:1619-1633. [CrossRef]

- Cao G-Y, Li M, Han L, Tayie F, Yao S-S, Huang Z, et al. Dietary fat intake and cognitive function among older populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2019;6:204-211. [CrossRef]

- Solfrizzi V, Custodero C, Lozupone M, Imbimbo BP, Valiani V, Agosti P, et al. Relationships of dietary patterns, foods and micro- and macronutrients with Alzheimer’s Disease and late-life cognitive disorders. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2017;59:815-849. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Qiao S, Zhuang L, Xu S, Chen L, Lai Q, et al. Choline intake correlates with cognitive performance among elder adults in the United States. Behav Neurol 2021;2021:2962245. [CrossRef]

- Ylilauri MPT, Voutilainen S, Lonroos E, Virtanen HEK, Toumainen T-P, Salonen JT, Virtanen JK. Associations of dietary choline intake with risk of incident dementia and with cognitive performance: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2019;110:1416-1423. [CrossRef]

- Nakazaki E, Mah E, Sanoshy K, Citrolo D, Watanabe F. Citicoline and memory function in older adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Nutr 2021;151:2153-2160. [CrossRef]

- Lopresti AL, Smith SJ, Drummond PD. The effects of Lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation on cognitive function in adults with self-reported mild cognitive complaints: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Front Nutr 2022;9:843512. [CrossRef]

- Yuan C, Chen H, Wang Y, Schneider JA, Willett WC, Morris MC. Dietary carotenoids related to risk of incident Alzheimer dementia (AD) and brain AD neuropathology: a community-based cohort of older adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2021;113:200-208. [CrossRef]

- Johnson EJ, Vishwanathan R, Johnson MA, Hausman DB, Davey A, Scott TM, et al. Relationship between serum and brain carotenoids, α-tacopherol, and retinol concentrations and cognitive performance in the oldest old from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Aging Res 2013 2013:951. [CrossRef]

- Kim JY, Kang SW. Relationships between dietary intake and cognitive function in healthy Korean children and adolescents. J Lifestyle Med 2017;7:10-17. [CrossRef]

- Vizuete AA, Robles F, Rodriguez-Rodriguez E, Lopez-Sobaler AM, Ortega RM. Association between food and nutrient intakes and cognitive capacity in a group of institutionalized elderly people. Eur J Nutr 2010;49:293-300. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Yuan L, Feng L, Xi Y, Yu H, Ma W, et al. Association of dietary intake and lifestyle pattern with mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19:164-168. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Dong B, Zeng G, Li J, Wang W, Wang B, Yuan Q. Is there an association between mild cognitive impairment and dietary pattern in Chinese elderly? Results from a cross-sectional population study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-595. [CrossRef]

- Ylilaarui MPT, Voutilainen S, Lonnroos E, Mursu J, Virtabnen HEK, Koskinen TT, et al. Association of dietary cholesterol and egg intakes with the risk of incident dementia or Azheimer disease: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:476-484. [CrossRef]

- Bishop NJ, Zuniga KE. Egg consumption, multi-domain cognitive performance, and short-term cognitive change in a representative sample of older U.S. adults. J Am Coll Nutr 2019;38:537-546. [CrossRef]

- Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry 1968;114:797-811. [CrossRef]

- Buschke H, Fuld PA. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology 1974;24:1019–1025. [CrossRef]

- Russell EW. A multiple scoring method for the assessment of complex memory functions. J Consult Clin Psychol 1975;43:800–809. [CrossRef]

- Wechsler D. A standardized memory scale for clinical use. J Psychol 1945;19:87–95. [CrossRef]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state." A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [CrossRef]

- Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:922–935. [CrossRef]

- Reitan R. Validity of the Trail-Making Test as an indicator of organic brain disease. Percept Mot Skills 1958;8:271–276. [CrossRef]

- Borkowski JB, Benton AL, Spreen O. Word fluency and brain damage. Neuropsychologia 1967;5:135–40. [CrossRef]

- McNamara DJ. The fifty-year rehabilitation of the egg. Nutrients 2015;7:8716-8722. [CrossRef]

- Zeisel SH, Corbin KD. Choline. In: Erdman JW, MacDonald IA, Zeisel SH eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition 10th ed., Washington, D C: Wiley-Blackwell;2012:405-418. [CrossRef]

- Poly C, Massaro JM, Seshadri S, Sheshadri S, Wolf PA, Cho E, Krall E, Jacques PF, Au R. The relation of dietary choline to cognitive performance and white-matter hyperintensity in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1584-91. [CrossRef]

- Mewborn CM, Lindbergh CA, Robinson TL, Gogniat MA, Terry DP, Jean KR, et al. Lutein and zeaxanthin are positively associated with visual-spatial functioning in older adults: an fMRI Study. Nutrients 2018;10:458. [CrossRef]

- Johnson EJ, Vishwanathan R, Johnson MA, Hausman DB, Davey A, Scott TM, Green RC, Miller LS, Gearing M, Woodard J, Nelson PT, Chung HY, Schalch W, Wittwer J, Poon LW. Relationship between serum and brain carotenoids, α-Tocopherol, and retinol concentrations and cognitive performance in the oldest old from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Aging Res 2013;2013:951786. [CrossRef]

- Nolan JM, Mulcahy R, Power R, Moran R, Howard AN. Nutritional intervention to prevent Alzheimer’s Disease: Potential benefits of xanthophyll carotenoids and omega-3 fatty acids combined. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2018;64:367-78. [CrossRef]

- Hammond BR, Miller LS, Bello MO, Lindbergh CA, Mewborn C, Renzi-Hammond LM. Effects of Lutein/zeaxanthin supplementation on the cognitive function of community dwelling older adults: a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Front Aging Neurosci 2017;9:254. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).