Submitted:

13 December 2023

Posted:

14 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Health Impacts of Microplastics

2.1. Physical Hazard

2.2. Chemical Hazard

2.3. Microbiological Hazard

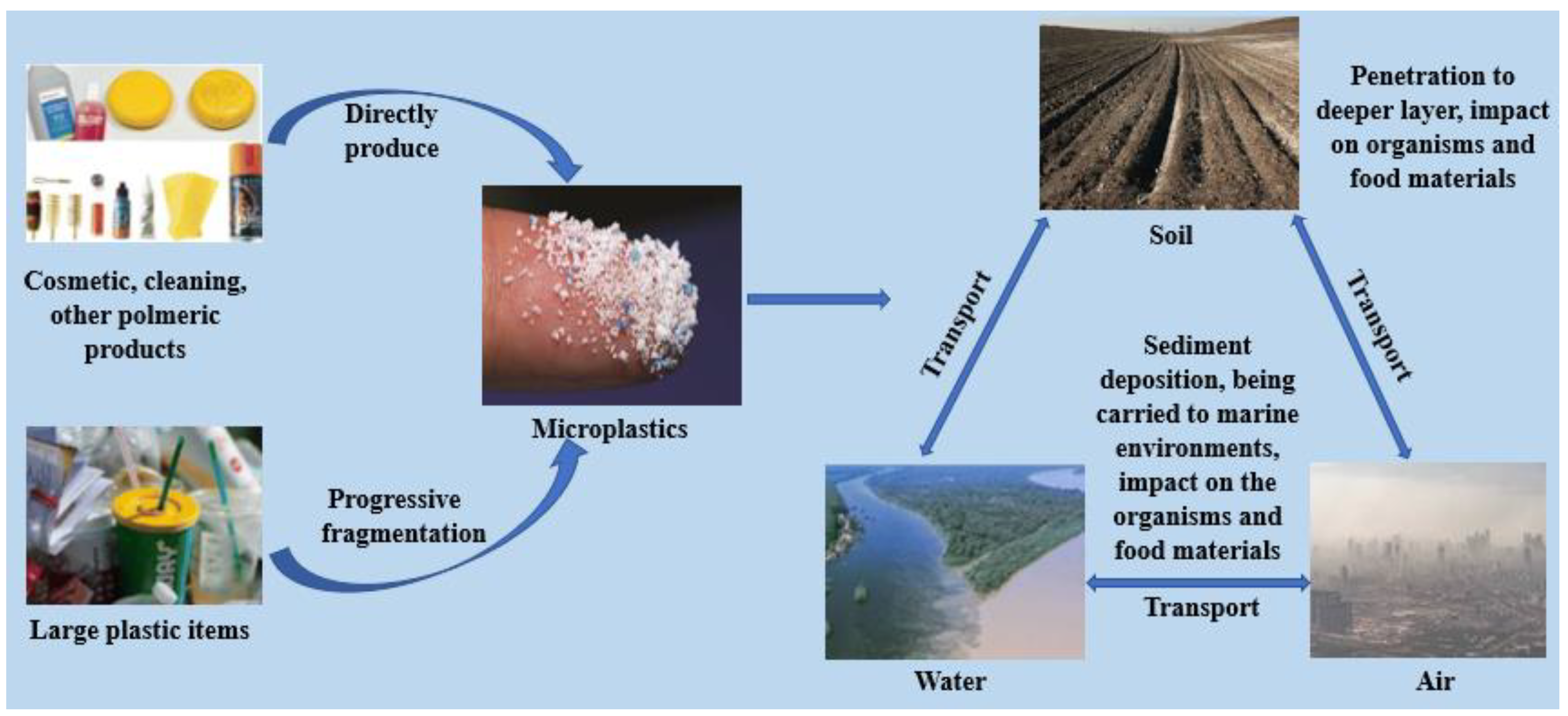

3. Sources and Transport of Microplastics

3.1. Wastewater Effluent

3.2. Run-off from Land-based Sources

3.3. Combined Sewer Overflows

3.4. Atmospheric Deposition

3.5. Industrial Effluent

3.6. Drinking-Water Production and Distribution

3.7. Fragmentation and Degradation of Macroplastics

4. Analysis of Microplastics

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Extraction and Isolation

4.3. Identification and Characterization of Microplastics

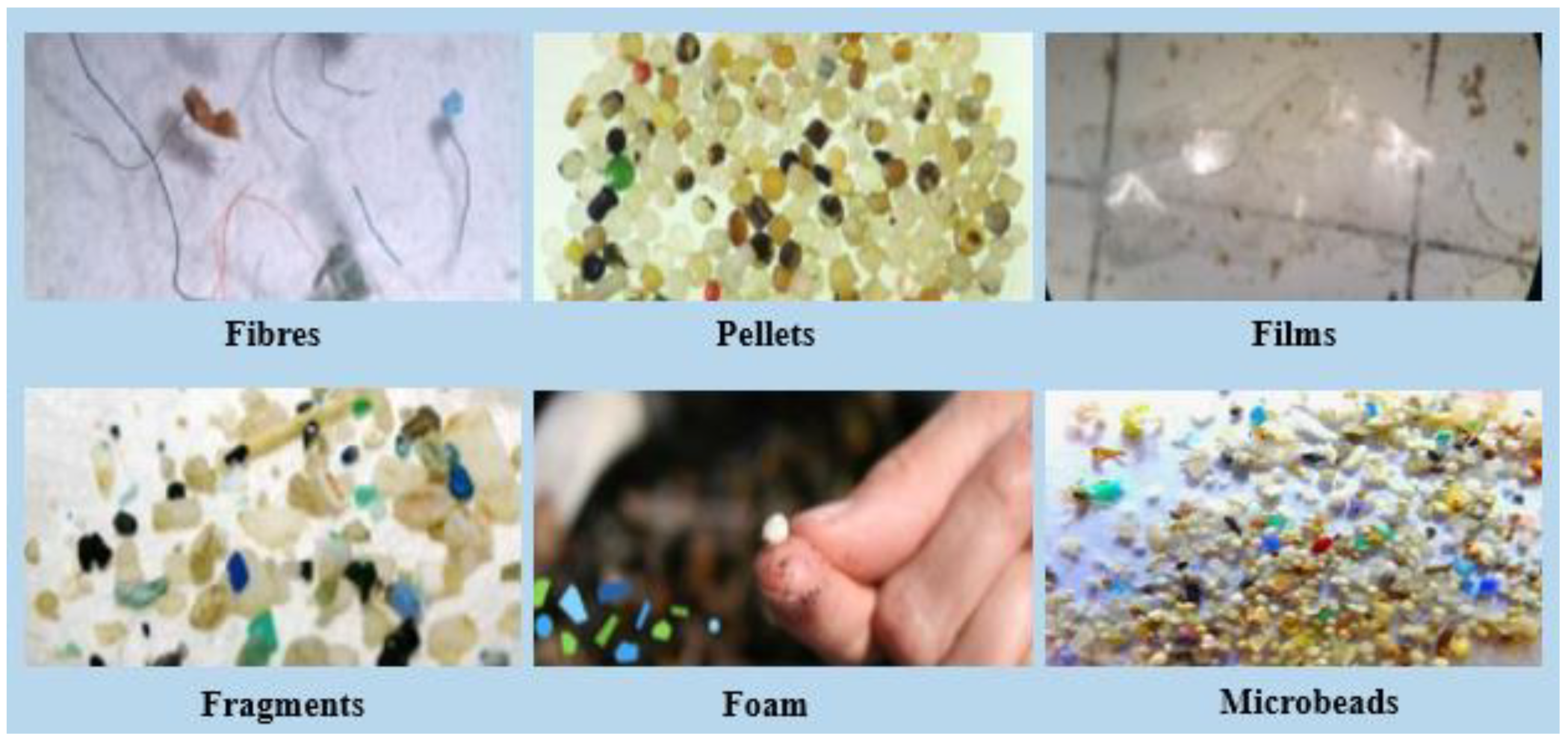

4.3.1. Visual Identification

4.3.2. Density Separation

4.3.3. Spectroscopic Method

- 4.3.3.1. Raman Spectroscopy

- 4.3.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

4.4. Thermo-analytical Method

4.5. Chemical Method

4.6. Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) Method

4.7. Combined Method

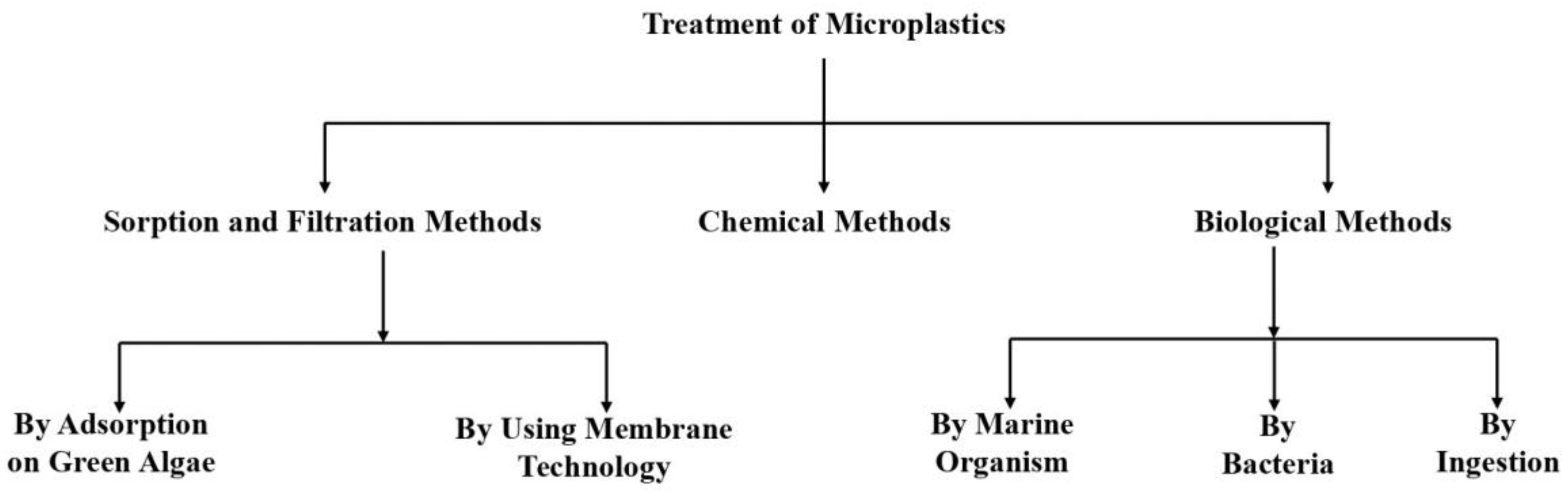

5. Treatment of Microplastics

5.1. Sorption and Filtration Methods:

5.1.1. By Adsorption on Green Algae

5.1.2. By Using Membrane Technology

5.2. Chemical Methods

5.3. Biological Methods

5.3.1. By Marine Organisms

5.3.2. By Bacteria

5.3.3. By Ingestion

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasi, S.; Keshavarzi, B.; Moore, F.; Turner, A.; Kelly, F.J.; Dominguez, A.O.; Jaafarzadeh, N. Distribution and potential health impacts of microplastics and microrubbers in air and street dusts from Asaluyeh County, Iran. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 244, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidli, S.; Toumi, H.; Lahbib, Y.; El Menif, N.T. The first evaluation of microplastics in sediments from the complex lagoon-channel of bizerte (Northern Tunisia). Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Shahid, M.; Azeem, F.; Rasul, I.; Shah, A.A.; Noman, M.; Hameed, A.; Manzoor, N.; Manzoor, I.; Muhammad, S. Biodegradation of plastics: current scenario and future prospects for environmental safety. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 7287–7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbal, F.; Camcı, S. Copper, chromium and nickel removal from metal plating wastewater by electrocoagulation. Desalination 2011, 269, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhbarizadeh, R.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B. Investigating a probable relationship between microplastics and potentially toxic elements in fish muscles from northeast of Persian Gulf. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 232, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimi, O.S.; Farner Budarz, J.; Hernandez, L.M.; Tufenkji, N. Microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments: Aggregation, deposition, and enhanced contaminant transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1704–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.J.; Warrack, S.; Langen, V.; Challis, J.K.; Hanson, M.L.; Rennie, M.D. Microplastic contamination in Lake Winnipeg, Canada. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 225, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. (2007). Biodegradability of polymers. In Physical properties of polymers handbook, 951-964. Springer, New York, NY.

- Andrady, A.L. The plastic in microplastics: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Tarazona, M.C., Villarreal-Chiu, J.F., Barbieri, V., Siligardi, C., & Cedillo-González, E.I. (2019). New strategy for microplastic degradation: Green photocatalysis using a protein-based porous N-TiO2 semiconductor. Ceramics International, 45(7), 9618-9624. [CrossRef]

- Arossa, S.; Martin, C.; Rossbach, S.; Duarte, C.M. Microplastic removal by Red Sea giant clam (Tridacna maxima). Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, S.Y.; Bruce, T.F.; Bridges, W.C.; Klaine, S.J. Responses of Hyalella azteca to acute and chronic microplastic exposures. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 2564–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auta, H.; Emenike, C.; Fauziah, S. Distribution and importance of microplastics in the marine environment: A review of the sources, fate, effects, and potential solutions. Environ. Int. 2017, 102, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auta, H.; Emenike, C.; Fauziah, S. Screening of Bacillus strains isolated from mangrove ecosystems in Peninsular Malaysia for microplastic degradation. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1552–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, L.K. Evaluation of Bis (2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) in the PET Bottled Mineral Water of Different Brands and Impact of Heat by GC–MS/MS. Chem. Afr. 2022, 5, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.K.; Sharma, A. Estimation of Physico-Chemical, Trace Metals, Microbiological and Phthalate in PET Bottled Water. Chem. Afr. 2021, 4, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.K. (2022b). Microplastics (MPs) in Drinking Water: Uses, Sources & Transport. Futuristic Trends in Agriculture Engineering & Food Science, IIP Proceedings, Volume 2, Book 9, Part 1. ISBN: 978-93-95632-65-2.

- Bhardwaj, L.K.; Jindal, T. Persistent organic pollutants in Lakes of Grovnes Peninsula at Larsemann Hill Area, East Antarctica. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 4, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.; Sharma, S.; Ranjan, A.; Jindal, T. Persistent organic pollutants in lakes of Broknes peninsula at Larsemann Hills area, East Antarctica. Ecotoxicology 2019, 28, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.K., & Jindal, T. (2022). Polar Ecotoxicology: Sources and Toxic Effects of Pollutants. New Frontiers in Environmental Toxicology, 9-14.

- Bhardwaj, L. K., & Vikram, V. (2023). Air Pollution and Its Effect on Human Health. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.K. Occurrence of microplastics (MPs) in Antarctica and its impact on the health of organisms. Marit. Technol. Res. 2023, 6, 265418–265418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L. K., Singh, V. V., Dwivedi, K., & Rai, S. (2023). A Comprehensive Review on Sources, Types, Impact and Challenges of Air Pollution. [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, S.U.A.; You, X. Spatial distribution of microplastics in Chinese freshwater ecosystem and impacts on food webs. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 293, 118494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J., & Friot, D. (2017). Primary microplastics in the oceans: a global evaluation of sources (Vol. 10). Gland, Switzerland: Iucn.

- Brandon, J.; Goldstein, M.; Ohman, M.D. Long-term aging and degradation of microplastic particles: Comparing in situ oceanic and experimental weathering patterns. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 110, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, U. (2018). Sampling, preparation and detection methods. Discussion paper, microplastics analytics, eds. Stein U, Schritt H. Berlin: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (https://bmbf-plastik. de/en/publication/discussion-papermicroplastics-analytics, accessed 26 June 2019). 26 June.

- Cera, A., Cesarini, G., & Scalici, M. (2020). Microplastics in freshwater: what is the news from the world? Diversity, 12(7), 276.

- Cesa, F.S.; Turra, A.; Baruque-Ramos, J. Synthetic fibers as microplastics in the marine environment: A review from textile perspective with a focus on domestic washings. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 598, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M., Sharma, A., Pervez, A., Upadhyay, P., & Dutta, J. (2022). Growing Menace of Microplastics in and Around the Coastal Ecosystem. In Coastal Ecosystems, 117-137. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Cocca, M., Di Pace, E., Errico, M.E., Gentile, G., Montarsolo, A., Mossotti, R., & Avella, M. (2020). Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Microplastic Pollution in the Mediterranean Sea. Springer Nature.

- Collard, F.; Gilbert, B.; Eppe, G.; Parmentier, E.; Das, K. Detection of anthropogenic particles in fish stomachs: An isolation method adapted to identification by raman spectroscopy. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015, 69, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Qiang, H.; Yang, Z.; Guo, X.; Gao, S. Which factors mainly drive the photoaging of microplastics in freshwater? Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 858, 159845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.L.; Kawaguchi, S.; King, C.K.; Townsend, K.A.; King, R.; Huston, W.M.; Nash, S.M.B. Turning microplastics into nanoplastics through digestive fragmentation by Antarctic krill. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghani, S.; Moore, F.; Akhbarizadeh, R. Microplastic pollution in deposited urban dust, Tehran metropolis, Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 20360–20371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Manuscript prepared for submission to environmental toxicology and pharmacology pollution in drinking water source areas: Microplastics in the Danjiangkou Reservoir, China. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 65, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, M.; Wang, J. Microplastics in surface waters and sediments of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, M.J.; Watson, W.; Bowlin, N.M.; Sheavly, S.B. Plastic particles in coastal pelagic ecosystems of the Northeast Pacific ocean. Mar. Environ. Res. 2011, 71, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerkes-Medrano, D.; Thompson, R.C.; Aldridge, D.C. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Res. 2015, 75, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M. , Lebreton, L.C.M., Carson, H.S., Thiel, M., Moore, C.J., Borerro, J.C., Galgani, F., Ryan, P.G., & Reisser, J. (2014), Plastic pollution in the world's oceans: more than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PloS one, 9(12), e111913. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Mason, S.; Wilson, S.; Box, C.; Zellers, A.; Edwards, W.; Farley, H.; Amato, S. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of the Laurentian Great Lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C.; Beltrán, J.M.G.; Esteban, M.A.; Cuesta, A. In vitro effects of virgin microplastics on fish head-kidney leucocyte activities. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europe, P. (2019). Plastics–the facts: an analysis of European plastics production, demand and waste data. Plastics Europe, Brussels https://www.plasticseurope.org/download_file/force/2367/181. Accessed, 11.

- Fok, L.; Cheung, P. Hong Kong at the Pearl River Estuary: A hotspot of microplastic pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 99, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.M.; Jensen, O.P.; Mason, S.A.; Eriksen, M.; Williamson, N.J.; Boldgiv, B. High-levels of microplastic pollution in a large, remote, mountain lake. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 85, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Wang, J. Current practices and future perspectives of microplastic pollution in freshwater ecosystems in China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 691, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatidou, G.; Arvaniti, O.S.; Stasinakis, A.S. Review on the occurrence and fate of microplastics in Sewage Treatment Plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 367, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.D.; Wertz, H.; Leads, R.R.; Weinstein, J.E. Microplastic in two South Carolina Estuaries: Occurrence, distribution, and composition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 128, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, N.M.; Berry, K.L.E.; Rintoul, L.; Hoogenboom, M.O. Microplastic ingestion by scleractinian corals. Mar. Biol. 2015, 162, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.B., Huffer, T., Thompson, R.C., Hassellöv, M., Verschoor, A., Daugaard, A.E., Rist, S., Karlsson, T., Brennholt, N., Cole, M., Herrling, M.P., Hess, M.C., lvleva, N.P., Lusher, A.L., & Wagner, M. (2019). Are we speaking the same language? Recommendations for a definition and categorization framework for plastic debris.

- He, S.; Tong, J.; Xiong, W.; Xiang, Y.; Peng, H.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Hu, M.; Yang, Z.; et al. Microplastics influence the fate of antibiotics in freshwater environments: Biofilm formation and its effect on adsorption behavior. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.; Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G. Microfibres from apparel and home textiles: Prospects for including microplastics in environmental sustainability assessment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 652, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A. (2017). Microplastics in the Freshwater Environment. A Review of Current Knowledge. FRR0027. Foundation for Water Research, Marlow, UK.

- Horton, A.A.; Dixon, S.J. Microplastics: An introduction to environmental transport processes. WIREs Water 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Svendsen, C.; Williams, R.J.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E. Large microplastic particles in sediments of tributaries of the River Thames, UK – Abundance, sources and methods for effective quantification. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 114, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.-Q. Occurrence of microplastics and its pollution in the environment: A review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 13, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, P.J. (2015). Biodegradable Plastics and Marine Litter: Misconceptions. Concerns and Impacts on Marine Environments.

- Koelmans, A.A.; Nor, N.H.M.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Res. 2019, 155, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooi, M., Besseling, E., Kroeze, C., Van Wezel, A.P., & Koelmans, A.A. (2018). Modeling the fate and transport of plastic debris in freshwaters: review and guidance. Freshwater microplastics, 125-152.

- Kosuth, M.; Mason, S.A.; Wattenberg, E.V. Anthropogenic contamination of tap water, beer, and sea salt. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0194970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lares, M., Ncibi, M.C., Sillanpää, M., & Sillanpää, M. (2018). Occurrence, identification and removal of microplastic particles and fibers in conventional activated sludge process and advanced MBR technology. Water research, 133, 236-246. [CrossRef]

- Laskar, N.; Kumar, U. Plastics and microplastics: A threat to environment. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 14, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, O.-W.; Wong, S.-K. Contamination in food from packaging material. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 882, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, Y.C.; Jang, M.; Heo, N.W.; Han, G.M.; Lee, M.J.; Kang, D.; et al. Relationships among the abundances of plastic debris in different size classes on beaches in South Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, R.; Enders, K.; Stedmon, C.A.; Mackenzie, D.M.; Nielsen, T.G. A critical assessment of visual identification of marine microplastic using Raman spectroscopy for analysis improvement. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Busquets, R.; Campos, L.C. Assessment of microplastics in freshwater systems: A review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 707, 135578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, G.; Yu, H.; Xing, J. Dynamic membrane for micro-particle removal in wastewater treatment: Performance and influencing factors. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 627, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Qian, L.; Wang, H.; Zhan, X.; Lu, K.; Gu, C.; Gao, S. New insights into the aging behavior of microplastics accelerated by advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 3579–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löder, M.G.J.; Gerdts, G. Methodology used for the detection and identification of microplastics—A critical appraisal. Mar. Anthropog. Litter 2015, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Geng, J.; Ding, L.; Ren, H.-Q. Uptake and accumulation of polystyrene microplastics in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) and toxic effects in liver. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4054–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Su, L.; Craig, N.J.; Du, F.; Wu, C.; Shi, H. Comparison of microplastic pollution in different water bodies from urban creeks to coastal waters. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 246, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A.L.; Burke, A.; O’connor, I.; Officer, R. Microplastic pollution in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean: Validated and opportunistic sampling. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 88, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, M.J.F.; Mota, C.F.; A Pearson, G. Sex-biased gene expression in the brown alga Fucus vesiculosus. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 294–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathalon, A.; Hill, P. Microplastic fibers in the intertidal ecosystem surrounding Halifax Harbor, Nova Scotia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 81, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuguma, Y.; Takada, H.; Kumata, H.; Kanke, H.; Sakurai, S.; Suzuki, T.; Itoh, M.; Okazaki, Y.; Boonyatumanond, R.; Zakaria, M.P.; et al. Microplastics in sediment cores from Asia and Africa as indicators of temporal trends in plastic pollution. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2017, 73, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.Z.; Watts, A.J.; Winslow, B.O.; Galloway, T.S.; Barrows, A.P. Mountains to the sea: River study of plastic and non-plastic microfiber pollution in the northeast USA. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloloža, M.; Grgić, D.K.; Bolanča, T.; Ukić. ; Cvetnić, M.; Bulatović, V.O.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Kušić, H. Ecotoxicological assessment of microplastics in freshwater sources—A review. Water 2020, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintenig, S.M., Int-Veen, I., Löder, M.G., Primpke, S., & Gerdts, G. (2017). Identification of microplastic in effluents of wastewater treatment plants using focal plane array-based micro-Fourier-transform infrared imaging. Water research, 108, 365-372. [CrossRef]

- Mintenig, S.M.; Löder, M.G.J.; Primpke, S.; Gerdts, G. Low numbers of microplastics detected in drinking water from ground water sources. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 648, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morritt, D.; Stefanoudis, P.V.; Pearce, D.; Crimmen, O.A.; Clark, P.F. Plastic in the Thames: A river runs through it. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 78, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F.; Quinn, B. Wastewater treatment works (WwTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, T.M.; Hartmann, N.B.; Kleijn, J.M.; Garnæs, J.; van de Meent, D.; Hendriks, A.J.; Baun, A. The toxicity of plastic nanoparticles to green algae as influenced by surface modification, medium hardness and cellular adsorption. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 183, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuelle, M.-T.; Dekiff, J.H.; Remy, D.; Fries, E. A new analytical approach for monitoring microplastics in marine sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oßmann, B.E.; Sarau, G.; Holtmannspötter, H.; Pischetsrieder, M.; Christiansen, S.H.; Dicke, W. Small-sized microplastics and pigmented particles in bottled mineral water. Water Res. 2018, 141, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paço, A.; Duarte, K.; da Costa, J.P.; Santos, P.S.; Pereira, R.; Pereira, M.; Freitas, A.C.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.A. Biodegradation of polyethylene microplastics by the marine fungus Zalerion maritimum. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 586, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padervand, M.; Lichtfouse, E.; Robert, D.; Wang, C. Removal of microplastics from the environment. A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiponen, K.-E.; Räty, J.; Ishaq, U.; Pélisset, S.; Ali, R. Outlook on optical identification of micro- and nanoplastics in aquatic environments. Chemosphere 2018, 214, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.; Xu, P.; Zhu, B.; Bai, M.; Li, D. Microplastics in freshwater river sediments in Shanghai, China: A case study of risk assessment in mega-cities. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perren, W.; Wojtasik, A.; Cai, Q. Removal of microbeads from wastewater using electrocoagulation. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3357–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, S.; Park, J.; Din, M.F.M.; Taib, S.M.; Talaiekhozani, A.; Yadav, K.K.; Kamyab, H. Microplastics pollution in different aquatic environments and biota: A review of recent studies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2019). Our World in Data. 2019. Mental Health URL: https://ourworldindata. org/mental-health [accessed 2019-08-15].

- Sadri, S.S.; Thompson, R.C. On the quantity and composition of floating plastic debris entering and leaving the Tamar Estuary, Southwest England. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 81, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarijan, S.; Azman, S.; Said, M.I.M.; Jamal, M.H. Microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: a recent review of occurrence, analysis, potential impacts, and research needs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 1341–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, D.; Goldbeck, C.; Humpf, H.-U.; Fürst, P. Analysis of microplastics in water by micro-Raman spectroscopy: Release of plastic particles from different packaging into mineral water. Water Res. 2017, 129, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serranti, S.; Palmieri, R.; Bonifazi, G.; Cózar, A. Characterization of microplastic litter from oceans by an innovative approach based on hyperspectral imaging. Waste Manag. 2018, 76, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasaki, N.; Matsushita, T.; Matsui, Y.; Marubayashi, T. Effect of aluminum hydrolyte species on human enterovirus removal from water during the coagulation process. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 284, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighicelli, M.; Pietrelli, L.; Lecce, F.; Iannilli, V.; Falconieri, M.; Coscia, L.; Di Vito, S.; Nuglio, S.; Zampetti, G. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of Italian Subalpine Lakes. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Rani, M.; Lee, J.; Shim, W.J. A comparison of microscopic and spectroscopic identification methods for analysis of microplastics in environmental samples. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 93, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sruthy, S.; Ramasamy, E. Microplastic pollution in Vembanad Lake, Kerala, India: The first report of microplastics in lake and estuarine sediments in India. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolte, A.; Forster, S.; Gerdts, G.; Schubert, H. Microplastic concentrations in beach sediments along the German Baltic coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 99, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Xue, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, D.; Kolandhasamy, P.; Li, D.; Shi, H. Microplastics in Taihu Lake, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 216, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Q.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.; Ni, B.-J. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Detection, occurrence and removal. Water Res. 2019, 152, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundbæk, K.B.; Koch, I.D.W.; Villaro, C.G.; Rasmussen, N.S.; Holdt, S.L.; Hartmann, N.B. Sorption of fluorescent polystyrene microplastic particles to edible seaweed Fucus vesiculosus. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2923–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Yu, X.; Cai, L.; Wang, J.; Peng, J. Microplastics and associated PAHs in surface water from the Feilaixia Reservoir in the Beijiang River, China. Chemosphere 2019, 221, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofa, T.S.; Kunjali, K.L.; Paul, S.; Dutta, J. Visible light photocatalytic degradation of microplastic residues with zinc oxide nanorods. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebskorn, R.; Braunbeck, T.; Grummt, T.; Hanslik, L.; Huppertsberg, S.; Jekel, M.; Knepper, T.P.; Krais, S.; Müller, Y.K.; Pittroff, M.; et al. Relevance of nano- and microplastics for freshwater ecosystems: A critical review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 110, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP, U. (2018). Single-use plastics: a roadmap for sustainability. Plásticos De Un Solo Uso: Una hoja de ruta para la sostenibilidad.

- Urbanek, A.K.; Rymowicz, W.; Mirończuk, A.M. Degradation of plastics and plastic-degrading bacteria in cold marine habitats. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7669–7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hal, N.; Ariel, A.; Angel, D.L. Exceptionally high abundances of microplastics in the oligotrophic Israeli Mediterranean coastal waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 116, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedolin, M.; Teophilo, C.; Turra, A.; Figueira, R. Spatial variability in the concentrations of metals in beached microplastics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoor, A., De Poorter, L., Dröge, R., Kuenen, J., & de Valk, E. (2016). Emission of microplastics and potential mitigation measures: Abrasive cleaning agents, paints and tyre wear.

- Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Tan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Chen, Q.; Cai, L. Microplastics in the surface sediments from the Beijiang River littoral zone: Composition, abundance, surface textures and interaction with heavy metals. Chemosphere 2017, 171, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Kaeppler, A.; Fischer, D.; Simmchen, J. Photocatalytic TiO2 micromotors for removal of microplastics and suspended matter. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 32937–32944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zou, X.; Li, B.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Hui, H.; Yu, W.; Wang, C. Microplastics in a wind farm area: A case study at the Rudong Offshore Wind Farm, Yellow Sea, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 128, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ndungu, A.W.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Microplastics pollution in inland freshwaters of China: A case study in urban surface waters of Wuhan, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 575, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. (2015). Marine microplastic removal tool (U.S. Patent No. 8,944,253). Water Witch: World Leaders in Waterway Cleanup. (n.d.). Water Witch. Retrieved , 2020, from https://waterwitch.com/. 18 February.

- Windsor, F.M.; Tilley, R.M.; Tyler, C.R.; Ormerod, S.J. Microplastic ingestion by riverine macroinvertebrates. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 646, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.L., & Kelly, F.J. (2017). Plastic and human health: a micro issue? Environmental science & technology 51(12):6634-6647. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Wu, C.; Elser, J.J.; Mei, Z.; Hao, Y. Occurrence and fate of microplastic debris in middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River – From inland to the sea. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 659, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Nie, H.; Xu, K.; He, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J. Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in the Pearl River along Guangzhou city and Pearl River estuary, China. Chemosphere 2018, 217, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wu, C. Microplastics in freshwater sediment: A review on methods, occurrence, and sources. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 754, 141948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.M.; Elliott, J.A. Characterization of microplastic and mesoplastic debris in sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 113, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Peng, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Bao, S. Occurrence of microplastics in the beach sand of the Chinese inner sea: the Bohai Sea. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W., Liu, X., Wang, W., Di, M., & Wang, J. (2019). Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in water, sediments, and wild fish from Poyang Lake, China. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 170, 180-187. [CrossRef]

- Zbyszewski, M.; Corcoran, P.L. Distribution and degradation of fresh water plastic particles along the beaches of Lake Huron, Canada. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 220, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Su, J.; Xiong, X.; Wu, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, J. Microplastic pollution of lakeshore sediments from remote lakes in Tibet plateau, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xiong, X.; Hu, H.; Wu, C.; Bi, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Lam, P.K.S.; Liu, J. Occurrence and characteristics of microplastic pollution in Xiangxi Bay of Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3794–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhong, S.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Gao, P. Microplastics in freshwater and wild fishes from Lijiang River in Guangxi, Southwest China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 755, 142428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Leng, Y., Liu, X., Huang, K., & Wang, J. (2020). Microplastics’ pollution and risk assessment in an urban river: A case study in the Yongjiang River, Nanning City, South China. Exposure and Health, 12(2), 141-151. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, D. Microplastic in three urban estuaries, China. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 206, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhu, L.; Wang, T.; Li, D. Suspended microplastics in the surface water of the Yangtze Estuary System, China: First observations on occurrence, distribution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 86, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Gu, X.; Li, D.; Yin, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, W. Changes in life-history traits, antioxidant defense, energy metabolism and molecular outcomes in the cladoceran Daphnia pulex after exposure to polystyrene microplastics. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Sample Types | Locations | Detection Methods | Microplastic’s Concentration | Type/Color/Size of Microplastics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Microbeads from customer products | Great Lakes, USA | EDS and SEM | 0.043 particles/m3 | Blue, white and gold; <1×10−3 m | Eriksen et al. 2013 |

| 2 | 82 % of the fragments and debris, 25 % PE and 19 % PP |

Tamar Estuary, Southwest England | Sieving and FTIR spectroscopy | 0.028 particles/m3 | Yellow and black; 1–5×10−3 m PP and < 1 or 1-3×10−3 m nylon | Sadri and Thompson 2014 |

| 3 | Fragments and films | Lake Hovsgol, Mongolia | Sieving and light microscopy | 0.20 particles/m3 | White and blue | Free et al. 2014 |

| 4 | Microfibers |

Yangtze Estuary System, China | Floatation and stereomicroscope | 4137.3 ± 2461.5 and 0.167 ± 0.138 numbers/m3 | Transparent, white and black | Zhao et al. 2014 |

| 5 | Expanded PS |

Pearl River Estuary, Hong Kong | Visual sorting and sieve | Highest 2098 ± 1705, Median 520 ± 688 and lowest 94 ± 44 items/m2 | Fok and Cheung 2015 | |

| 6 | PP and PE | Urban estuaries, China | Micro-Raman spectroscopy, filtration and agitation | Ranged from 10.6 -119.8 % |

Transparent, black and white | Zhao et al. 2015 |

| 7 | PS, PP, polyvinyl chloride and PE | Tibet Plateau Lake, China | SEM and Raman spectroscopy | 8 ± 14 to 563 ± 1219 items/m2 |

Blue, yellow, white and transparent | Zhang et al. 2016 |

| 8 | Cellophane, PE, PS and PP | Taihu Lake, China | Micro-FTIR spectroscopy and SEM/EDS |

11.0–234.6 items/kg in sediment and 3.4–25.8×103 items/m3 in surface water | White (29 %) and transparent (44 %) | Su et al. 2016 |

| 9 | Fragments and fibers without plastic pellets | Lagoon-Channel of Bizerte, Northern Tunisia | Stereomicroscopy | 3000–18,000 items/kg, dry sediment |

Red, white, black, green and blue |

Abidli et al. 2017 |

|

10 |

22 % PET, 7 % PP, 22 % fluoro-polymer/Teflon, microfibers (43 % cotton) and 7 % nitrocellulose | Hudson River, USA |

FTIR spectroscopy |

0.625 to 2.45×103 fibers/m3 |

Blue, black, transparent and red |

Miller et al. 2017 |

| 11 | Secondary microplastics (91 % fragments) | River Thames, UK | Sieving, visual inspection and Raman spectroscopy | 33.2 ± 16.1×103 particles/100 kg sediment | Yellow and red |

Horton et al. 2017a |

| 12 | PE and PP |

Surface water of the urban area, Wuhan, China | Stereoscopic microscopy, SEM and FTIR spectroscopy | 1660.0 ± 639.1 to 8925 ± 1591 numbers/m3 |

50.4 % to 86.9 % transparent | W. Wang et al. 2017 |

| 13 | PP and PE | Beijiang River, China |

Flotation, SEM and FTIR spectroscopy | 178 ± 69 to 544 ± 107 items/kg sediment | Blue and brown | J. Wang et al. 2017 |

|

14 |

Low-density PE | Vembanad Lake, Kerala, India | Raman spectroscopy and wet peroxide oxidation | 252.80 ± 25.76 particles/m2 | White and transparent |

Sruthy and Ramasamy 2017 |

| 15 | Polyamides, PVC, acrylics, PS, PET, PP and PE | South Africa, Thailand, Japan and Malaysia | Density separation and FTIR spectroscopy |

100 to 1900 pieces/kg dry sediment | Black (14 %), brown (17 %) and white (57 %) | Matsuguma et al. 2017 |

| 16 | PP (29.4 %), PE (21 %) and PS (38.5 %) |

Three Gorges Reservoir, China |

Raman spectroscopy and FTIR spectroscopy |

25 to 300 numbers/kg wet weight in the sediments and 1597 to 12,611 numbers/m3 in surface water | Transparent | Di and Wang 2018 |

| 17 | 77.5 % fragments in Winyah Bay and 76.2 % fragments in Charleston Harbor | South Carolina Estuaries, USA |

Sieving, H2O2 treatment, SEM and FTIR spectroscopy |

221.0 ± 25.6 in sediment samples of Winyah Bay and 413.8 ± 76.7 particles/m2 in sediment samples of Charleston Harbor |

White, green, grey, blue, black, colorless and red |

Gray et al. 2018 |

| 18 | 75.3 % fibers in water and 68.7 % fibers in sediment |

Wind Farm, Yellow Sea, China |

Sieving, micro-FTIR spectroscopy and density separation |

2.58 ± 1.14×103 items/kg in the sediment and 0.330 ± 0.278 items/m3 in the surface water |

Black and transparent |

Wang et al. 2018 |

| 19 | PP (15 %), PS (18 %) and PE (45 %) | Italian Subalpine Lakes, Italy | FTIR spectroscopy | 4000 to 57,000 particles/km2 | Sighicelli et al. 2018 | |

| 20 | PP |

Shanghai, China |

Density separation, microscopy and micro-FTIR spectroscopy | 80.2 ± 59.4×103 items/100 kg dry weight |

Red, white, transparent and blue |

Peng et al. 2018 |

| 21 | PA (26.2 %) and cellophane (23.1 %) | Pearl River, China | Micro-Raman spectroscopy | 19.86×103 microplastic/m3 for urban and 8.90×103 microplastic/m3 for the estuary | Film, fiber and fragment | Yan et al. 2019 |

| 22 | PP (37 %) and PE (30 %) | Poyang Lake, China | Micro-Raman spectroscopy | 5 to 34×103 microplastic/m3 for surface water and 54 to 506 microplastic/kg for sediments | Fiber | Yuan et al. 2019 |

| 23 | PP and PE | Yong River, China | Raman spectroscopy | 0.5 to 7.7×103 microplastic/m3 for surface water and 54 to 506 microplastic/kg for sediments | Fiber | Zhang et al. 2020 |

| 24 | PP | Danjiangkou Reservoir, China | micro-Raman spectroscopy | 0.47 to 15.02×103 microplastic/m3 in surface water and 15 to 40 microplastic/kg in wastewater | Fiber | Di et al. 2019 |

| 25 | PS (27.7 %) | Suzhou River and Huangpu River, China | micro-FTIR spectroscopy | 0.08 to 7.4×103 microplastic/m3 | Fiber | Luo et al. 2019 |

| 26 | PP | Yangtze River, China | Raman spectroscopy | 4.92 ×105 microplastic/km2 | Fragment | Xiong et al. 2019 |

| 27 | PP (52.31 %) and PE (27.39 %) | Feilaixia Reservoir, China | micro-FTIR spectroscopy | 0.56 microplastic/m3 | Films | Tan et al. 2019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).