Submitted:

10 December 2023

Posted:

11 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of MnO2 Nanowires

2.3. Synthesis of MnO2 Nanowires@MgLaFe LDO

2.4. Synthesis of MgLaFe LDO

2.5. Adsorbent characterization techniques

2.6. Measurement method

2.7. Adsorption experiments

2.8. Kinetics of adsorption study

2.9. Adsorption isotherms study

3. Results and discussion

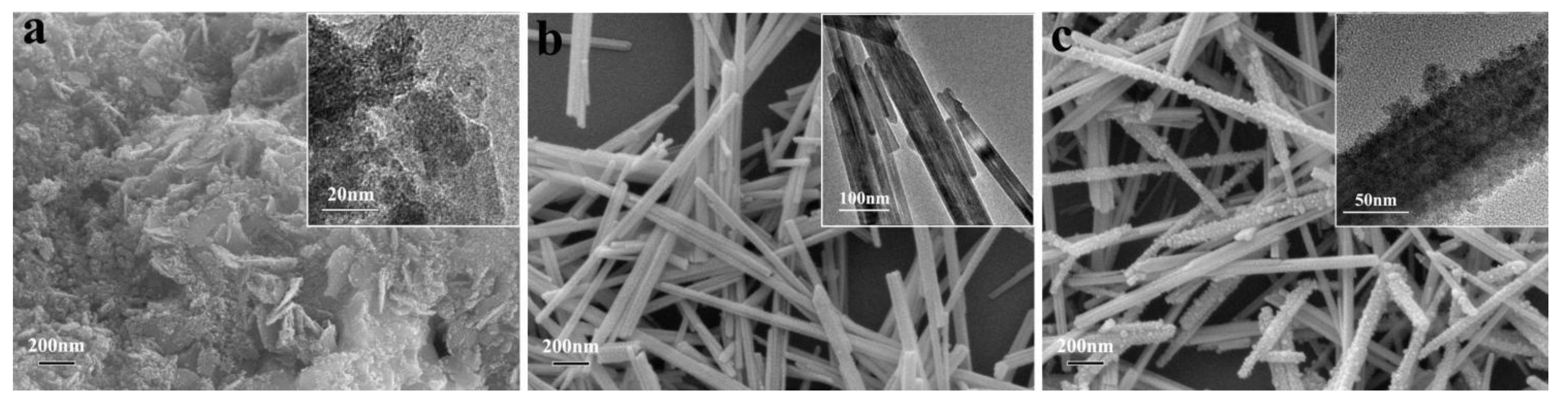

3.1. Morphology of the adsorbents

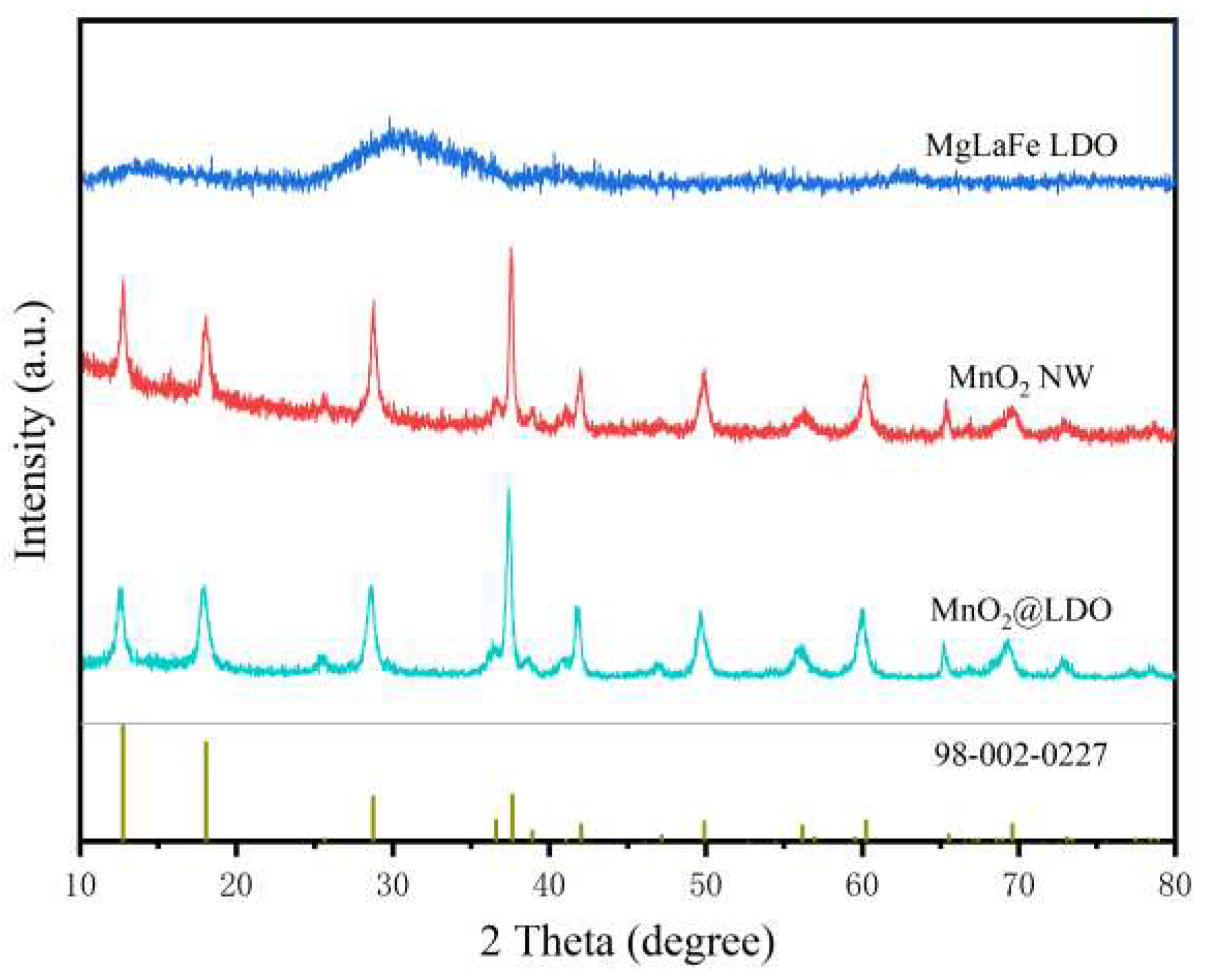

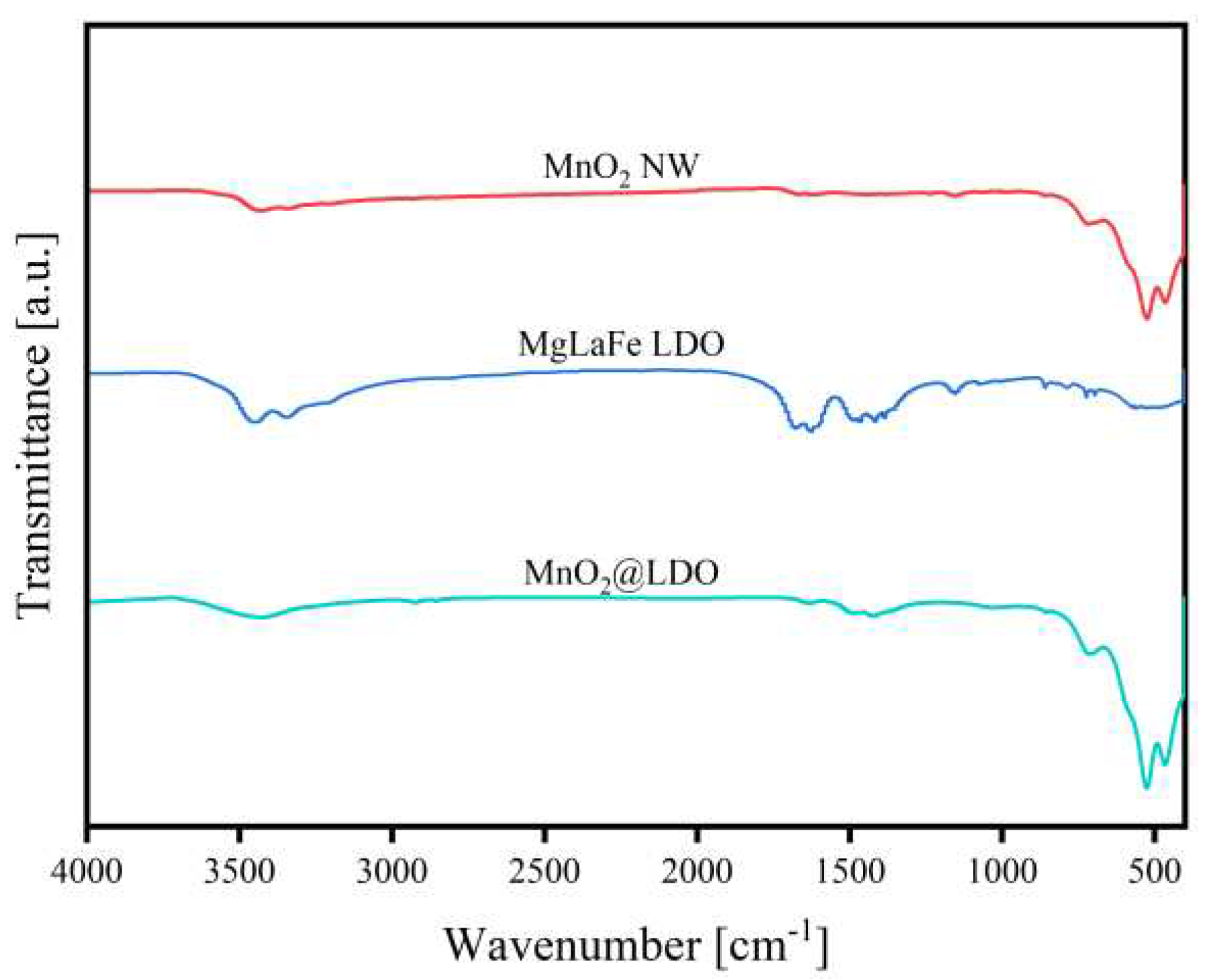

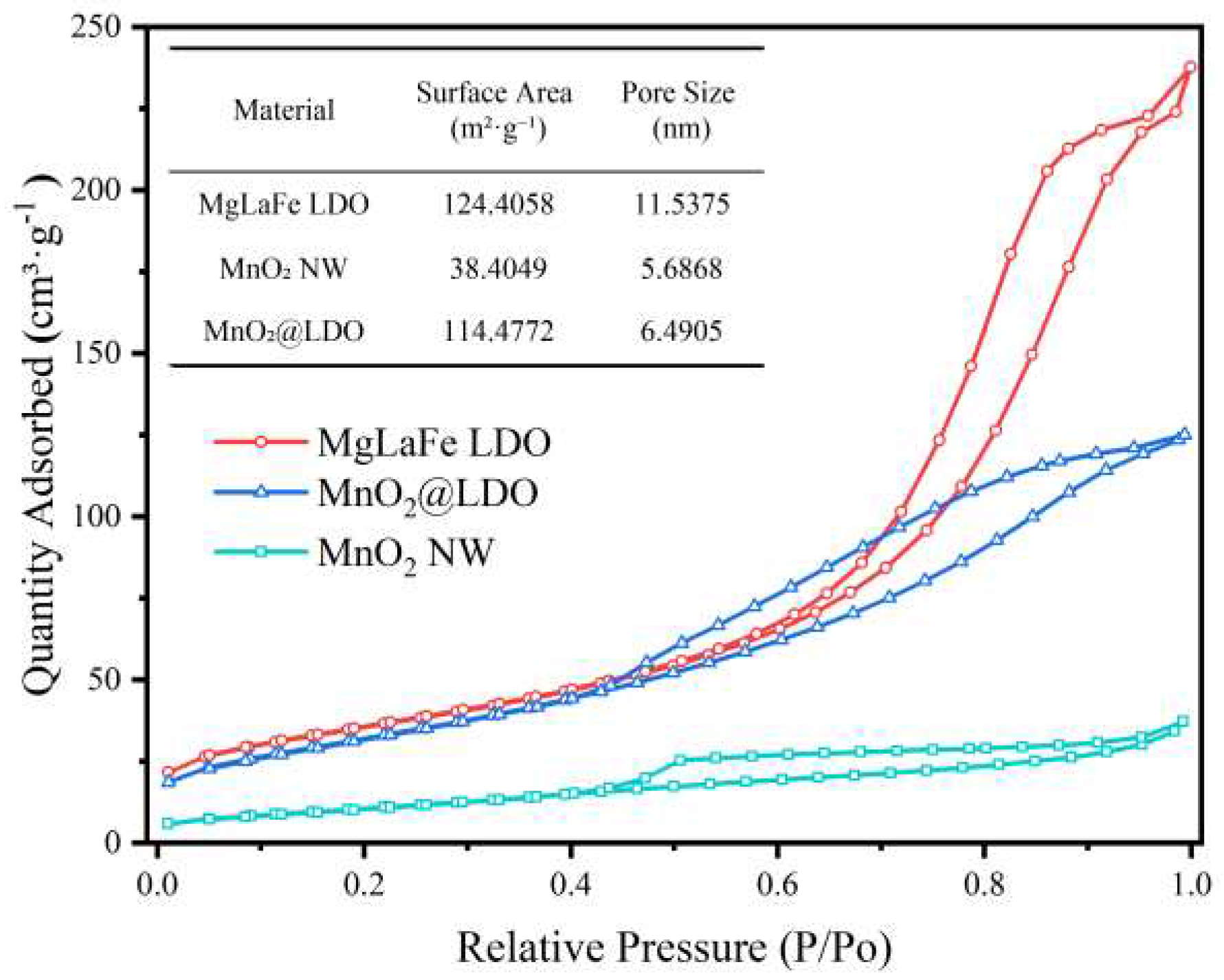

3.2. Characterization of the adsorbents

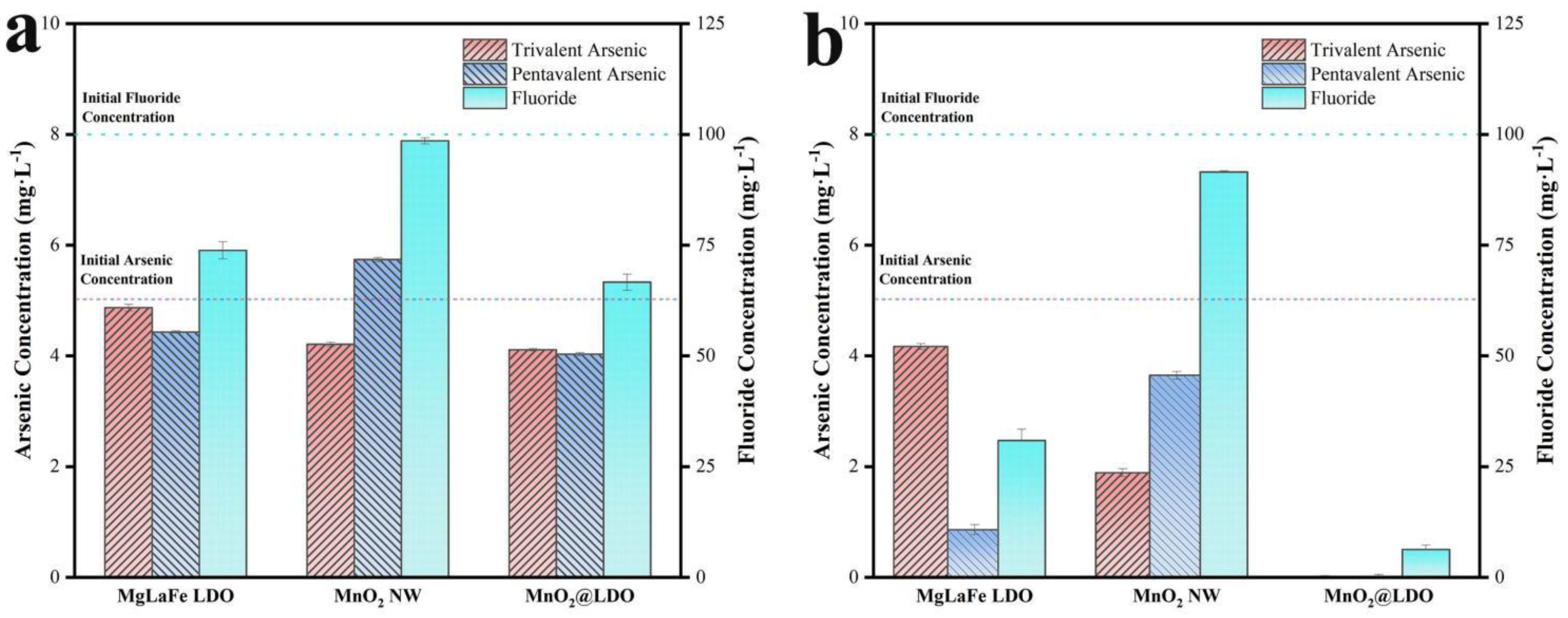

3.3. Evaluation of adsorption performance

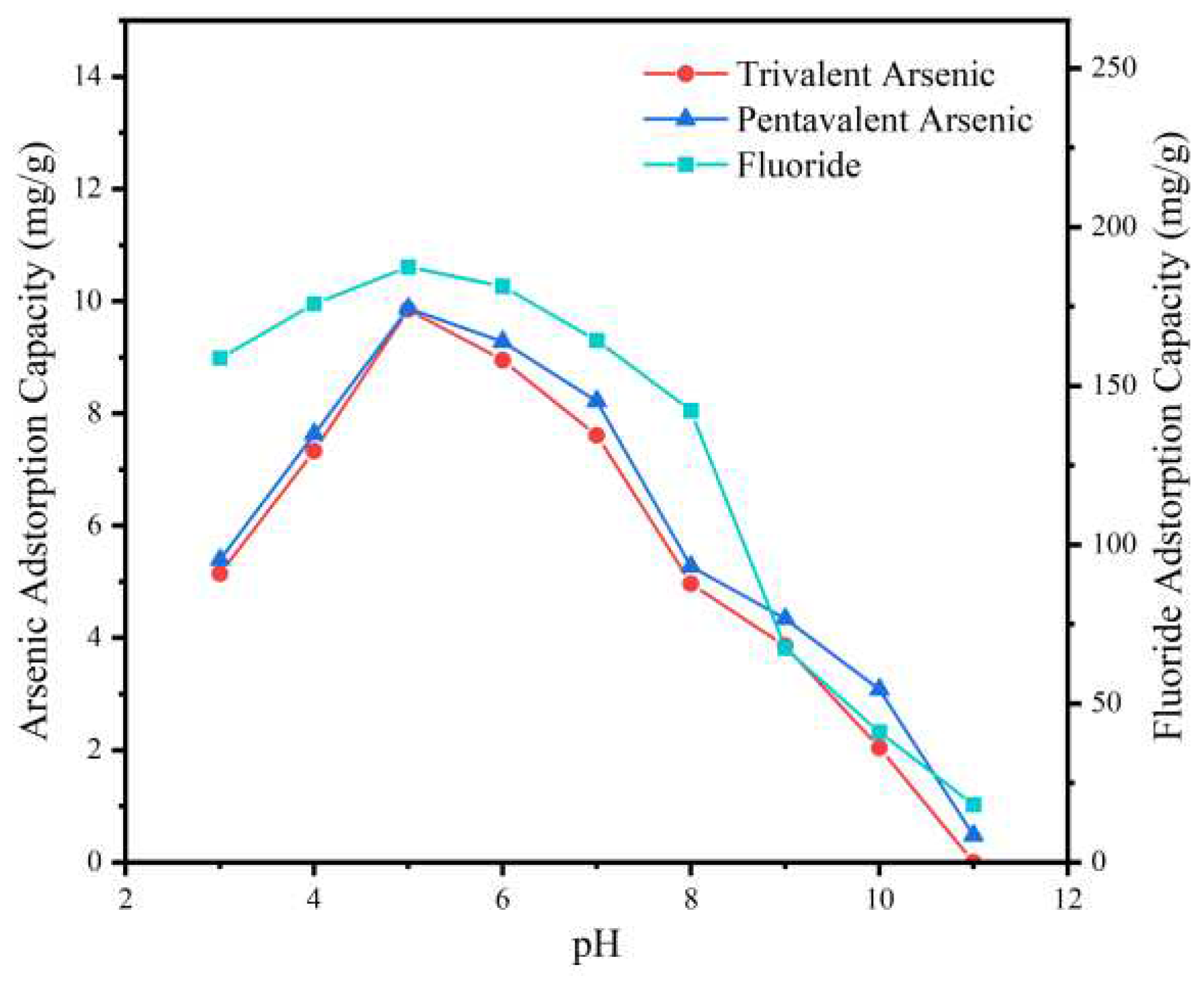

3.4. Effect of solution pH

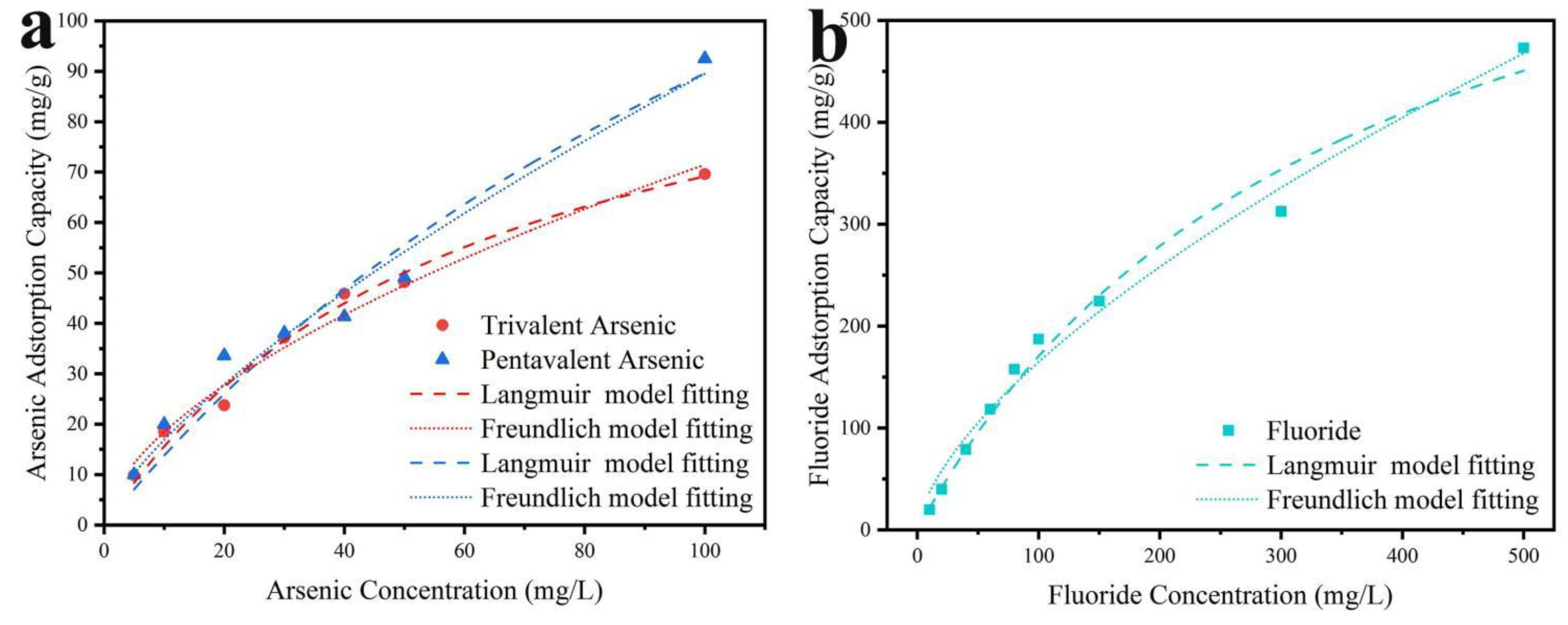

3.5. Isotherm study

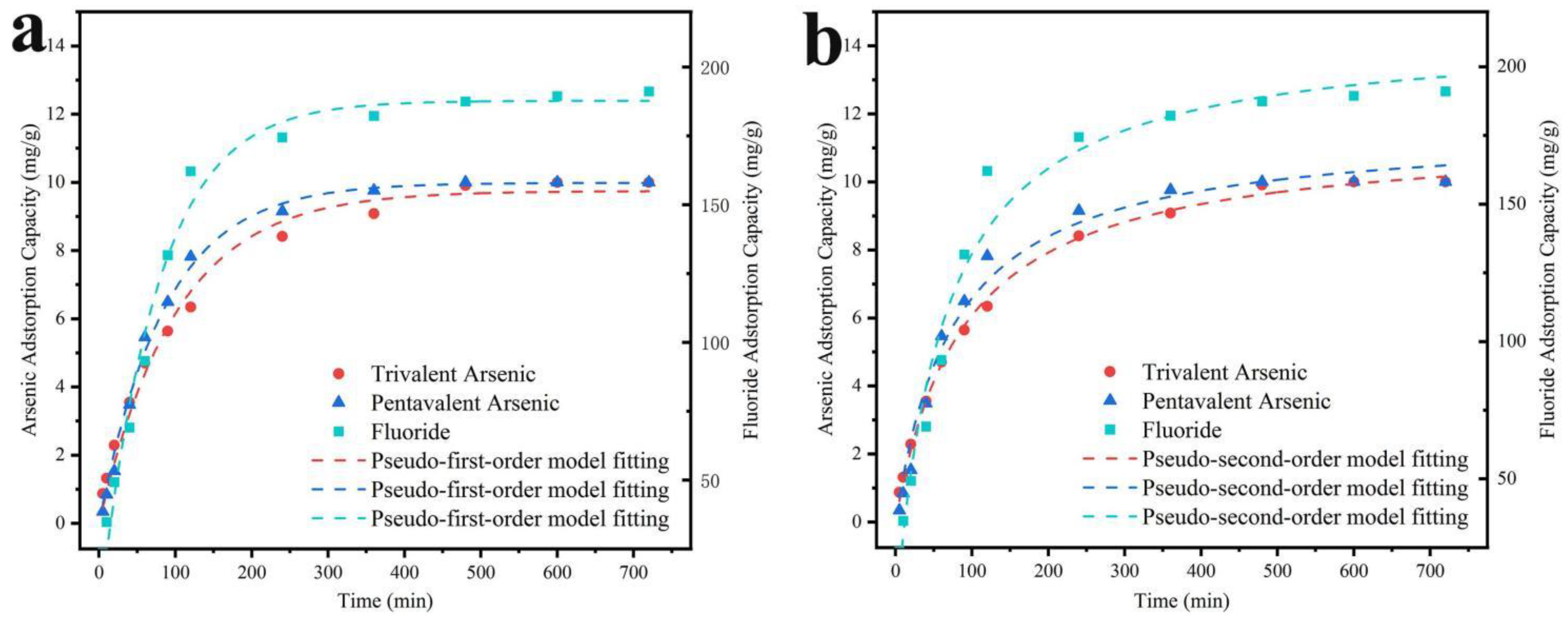

3.6. Kinetics study

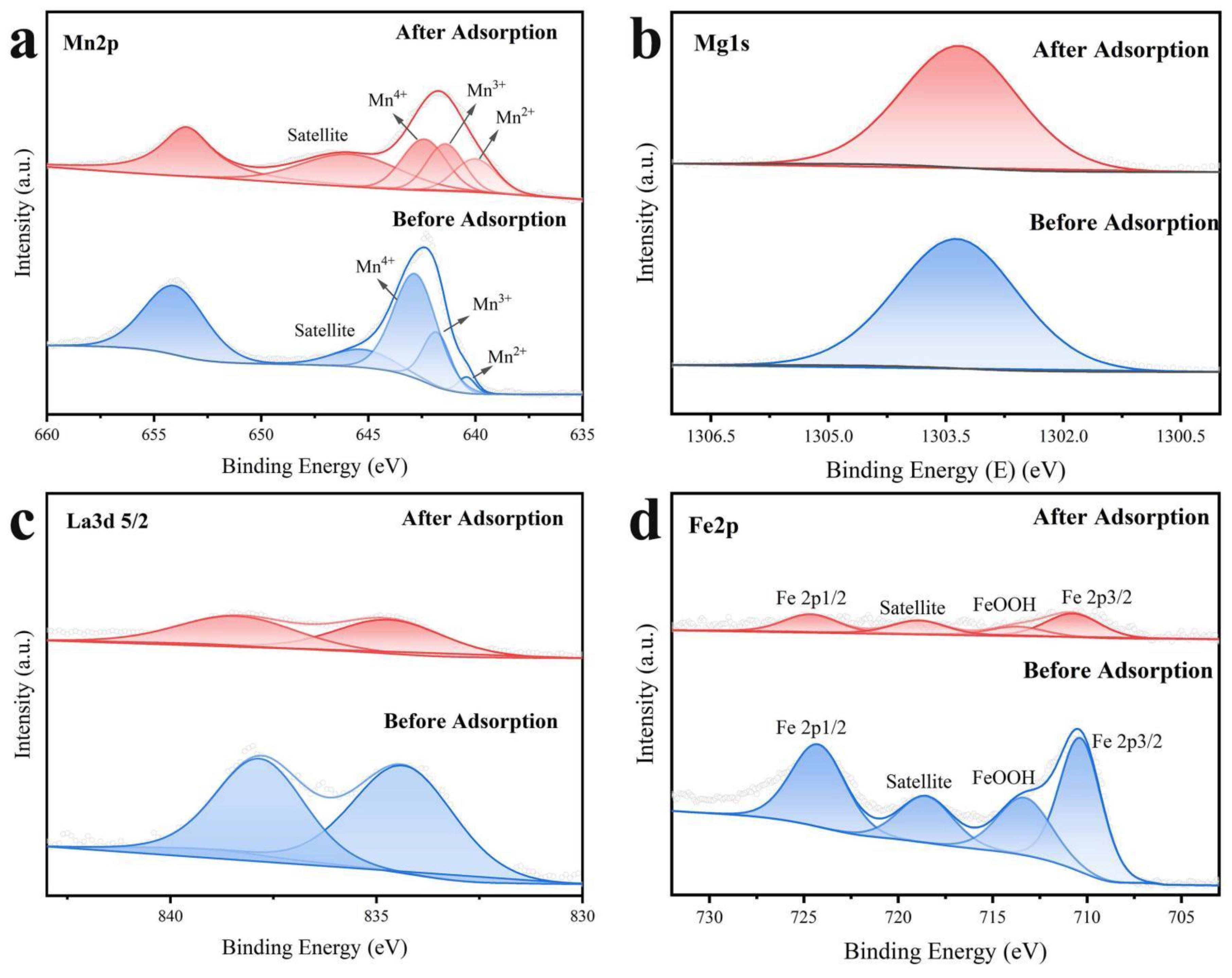

3.7. Mechanism Study

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, S.; Liu, B.; Chen, Y.; Ma, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, C., Hydro-geochemical control of high arsenic and fluoride groundwater in arid and semi-arid areas: A case study of Tumochuan Plain, China. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134657. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Goswami, R.; Patel, A. K.; Srivastava, M.; Das, N., Scenario, perspectives and mechanism of arsenic and fluoride Co-occurrence in the groundwater: A review. Chemosphere 2020, 249, 126126. [CrossRef]

- World Health, O., Guidelines for drinking-water quality: fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda. 4th ed + 1st add + 2nd add ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022.

- Podgorski, J.; Berg, M., Global analysis and prediction of fluoride in groundwater. Nature Communications 2022, 13(1), 4232. [CrossRef]

- Podgorski, J.; Berg, M., Global threat of arsenic in groundwater. Science 2020, 368(6493), 845-850. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Maiti, A., A hybrid ultrafiltration membrane process using a low-cost laterite based adsorbent for efficient arsenic removal. Chemosphere 2023, 316, 137685. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ma, J.; Ding, L.; Nie, Y.; Chen, Z.; Shen, J.; Huang, Y., Characteristics and mechanisms of As(III) removal by potassium ferrate coupled with Al-based coagulants: Analysis of aluminum speciation distribution and transformation. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137251. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M. A.; Fuentes, R.; Thiam, A.; Salazar, R., Arsenic and fluoride removal by electrocoagulation process: A general review. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 753, 142108. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Kim, K.-H.; Kumar, V.; Kim, S., A review of functional sorbents for adsorptive removal of arsenic ions in aqueous systems. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 388, 121815. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Tu, H.; Chan, T.; Jing, C., Mechanistic study of simultaneous arsenic and fluoride removal using granular TiO2-La adsorbent. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 313, 983-992. [CrossRef]

- Alka, S.; Shahir, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Ndejiko, M. J.; Vo, D.-V. N.; Manan, F. A., Arsenic removal technologies and future trends: A mini review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 278, 123805. [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B. S.; Kumar, P. S., A review on sources, identification and treatment strategies for the removal of toxic Arsenic from water system. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 418, 126299. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liang, K.; Yan, J.; Pan, Z.; Hu, G., pH effects of the arsenite photocatalytic oxidation reaction on different anatase TiO2 facets. Chemosphere 2019, 225, 434-442. [CrossRef]

- Gude, J. C. J.; Rietveld, L. C.; van Halem, D., As(III) oxidation by MnO2 during groundwater treatment. Water Research 2017, 111, 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Kumari, N.; Tyagi, M.; Jagadevan, S., LeaF-extract mediated zero-valent iron for oxidation of Arsenic (III): Preparation, characterization and kinetics. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 347, 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, N., Characteristics and model studies for fluoride and arsenic adsorption on goethite. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2010, 22(11), 1689-1694. [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Tan, X.; Xiang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, C.; Sha, Z.; Ren, L.; Wang, M.; Tan, W., Insights into the underlying effect of Fe vacancy defects on the adsorption affinity of goethite for arsenic immobilization. Environmental Pollution 2022, 314, 120268. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, X.; Pan, B., Fluoride uptake by three lanthanum based nanomaterials: Behavior and mechanism dependent upon lanthanum species. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 683, 609-616. [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Kamran, M. A.; Sultana, J.; Farooqi, A., Occurrence and methods to remove arsenic and fluoride contamination in water. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2017, 15(1), 125-149. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Meng, X.; Crittenden, J.; Qu, J.; Hu, C.; Liu, H.; Peng, P., Arsenic adsorption on α-MnO2 nanofibers and the significance of (100) facet as compared with (110). Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 331, 492-500.

- Ma, Z.; Fan, L.; Jing, F.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Fan, Y.; Dong, H.; Qin, X.; Shao, G., MnO2 Nanowires@NiCo-LDH Nanosheet Core–Shell Heterostructure: A Slow Irreversible Transition of Hydrotalcite Phase for High-Performance Pseudocapacitance Electrode. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2021, 4(4), 3983-3992.

- Chubar, N.; Gilmour, R.; Gerda, V.; Mičušík, M.; Omastova, M.; Heister, K.; Man, P.; Fraissard, J.; Zaitsev, V., Layered double hydroxides as the next generation inorganic anion exchangers: Synthetic methods versus applicability. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2017, 245, 62-80. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Cheng, W.; Liu, R.; Di, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Jiang, Z., Synergistic effect and mechanism of nZVI/LDH composites adsorption coupled reduction of nitrate in micro-polluted water. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 464, 133023. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, T.; Qin, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W., Carbon-Free, Binder-Free MnO2@Mn Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15(16), 20110-20119.

- Wang, F.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yan, Z.; Lan, D.; Lester, E.; Wu, T., A critical review of facets and defects in different MnO2 crystalline phases and controlled synthesis – Its properties and applications in the energy field. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2024, 500, 215537. [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Li, D.; Qin, P.; Tian, S.; Lu, M.; Cai, Z., Preparation of multivariate zirconia metal-organic frameworks for highly efficient adsorption of endocrine disrupting compounds. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 424, 127559. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Tanaka, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Kim, K.-W., Enhanced adsorption of arsenate and antimonate by calcined Mg/Al layered double hydroxide: Investigation of comparative adsorption mechanism by surface characterization. Chemosphere 2018, 211, 903-911. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, J.; Yao, L.; Shen, Q.; An, L.; Wang, X., Ultrahigh adsorbability towards different antibiotic residues on fore-modified selF-functionalized biochar: Competitive adsorption and mechanism studies. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 390, 122127. [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Luo, X.; Liu, C.; You, S.; Rad, S.; He, H.; Huang, Y.; Tu, Z., Enhancing mechanism of arsenic(iii) adsorption by MnO2-loaded calcined MgFe layered double hydroxide. RSC Advances 2022, 12(40), 25833-25843. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, B.; Tang, X.; Lin, X.; Li, P.; Chen, H.; Huang, F.; Wei, C.; Wei, J.; Qiu, G., Ca–La layered double hydroxide (LDH) for selective and efficient removal of phosphate from wastewater. Chemosphere 2023, 325, 138378. [CrossRef]

- Mrózek, O.; Ecorchard, P.; Vomáčka, P.; Ederer, J.; Smržová, D.; Slušná, M. Š.; Machálková, A.; Nevoralová, M.; Beneš, H., Mg-Al-La LDH-MnFe2O4 hybrid material for facile removal of anionic dyes from aqueous solutions. Applied Clay Science 2019, 169, 1-9.

- Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Li, J.; Tang, D.; Zhang, G., Simultaneous and efficient removal of fluoride and phosphate by Fe-La composite: Adsorption kinetics and mechanism. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 753, 422-432. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Xia, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, Q.; Song, S., Simultaneous Sorption of Arsenate and Fluoride on Calcined Mg–Fe–La Hydrotalcite-Like Compound from Water. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2018, 6(12), 16287-16297. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lin, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, K.; Wu, L.; Li, S.; Liu, H., As(III) removal from wastewater and direct stabilization by in-situ formation of Zn-Fe layered double hydroxides. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 403, 123920. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K. C. M.; Koong, L. F.; Al Ansari, T.; McKay, G., Adsorption/desorption of arsenite and arsenate on chitosan and nanochitosan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25(15), 14734-14742. [CrossRef]

- Pintor, A. M. A.; Vieira, B. R. C.; Santos, S. C. R.; Boaventura, R. A. R.; Botelho, C. M. S., Arsenate and arsenite adsorption onto iron-coated cork granulates. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 642, 1075-1089. [CrossRef]

- Zoroufchi Benis, K.; Soltan, J.; McPhedran, K. N., Electrochemically modified adsorbents for treatment of aqueous arsenic: Pore diffusion in modified biomass vs. biochar. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 423, 130061. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Tian, Q.; Liu, D.; Yang, D.; Qiu, F.; Zhang, T.; Sun, X., Pollution control by waste: Dual metal sludges derived Ni-Al LDOs for efficient fluoride removal. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Bo, A.; Tang, X.; Martens, W.; Kou, L.; Gu, Y.; Carja, G.; Zhu, H.; Sarina, S., High efficient arsenic removal by In-layer sulphur of layered double hydroxide. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 608, 2358-2366. [CrossRef]

| MnO2@LDO | Langmuir model | Freundich model | |||||

| Qm(mg/g) | KL(L/mg) | r2 | KF | n | r2 | ||

| As(Ⅲ) | 111.76 | 0.0162 | 0.9849 | 4.7628 | 0.5882 | 0.9778 | |

| As(Ⅴ) | 230.51 | 0.0064 | 0.9465 | 3.1986 | 0.7236 | 0.9712 | |

| F- | 765.10 | 0.0029 | 0.9808 | 8.3411 | 0.6480 | 0.9849 | |

| Adsorbents | Qm of As(Ⅲ) (mg/g) | Qm of As(Ⅴ) (mg/g) | Qm of F- (mg/g) | t (min) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnO2@LDO | 111.76 | 230.51 | 765.10 | 480 | This work |

| MnO2/MgFe-LDH | 53.79 | 1800 | [29] | ||

| ZnFe-LDHs | 62.11 | 200 | [34] | ||

| nanochitosan | 6.10 | 13.00 | 360 | [35] | |

| iron-coated cork granulates | 4.9 | 4.3 | 960 | [36] | |

| optimum modified biochar | 10.2 | 90 | [37] | ||

| Mg/Fe/La CHLc | 81.40 | 73.80 | 450 | [33] | |

| Ni-Al LDOs/sludge | 47.075 | 100 | [38] | ||

| TiO2-La | 114 | 78.4 | 900 | [10] | |

| In layer sulphur of LDH | 40.8 | 120 | [39] |

| MnO2@LDO | Pseudo-first-order model | Pseudo-second-order model | |||||

| qe(mg /g) | k1(min−1) | r2 | qe(mg /g) | k2(g/mg∙ min−1) | r2 | ||

| As (Ⅲ) | 9.75 | 0.0010 | 0.9867 | 11.40 | 0.0011 | 0.9973 | |

| As (Ⅴ) | 9.99 | 0.0117 | 0.9944 | 11.60 | 0.0011 | 0.9821 | |

| F- | 187.71 | 0.0133 | 0.9845 | 213.24 | 0.0001 | 0.9770 | |

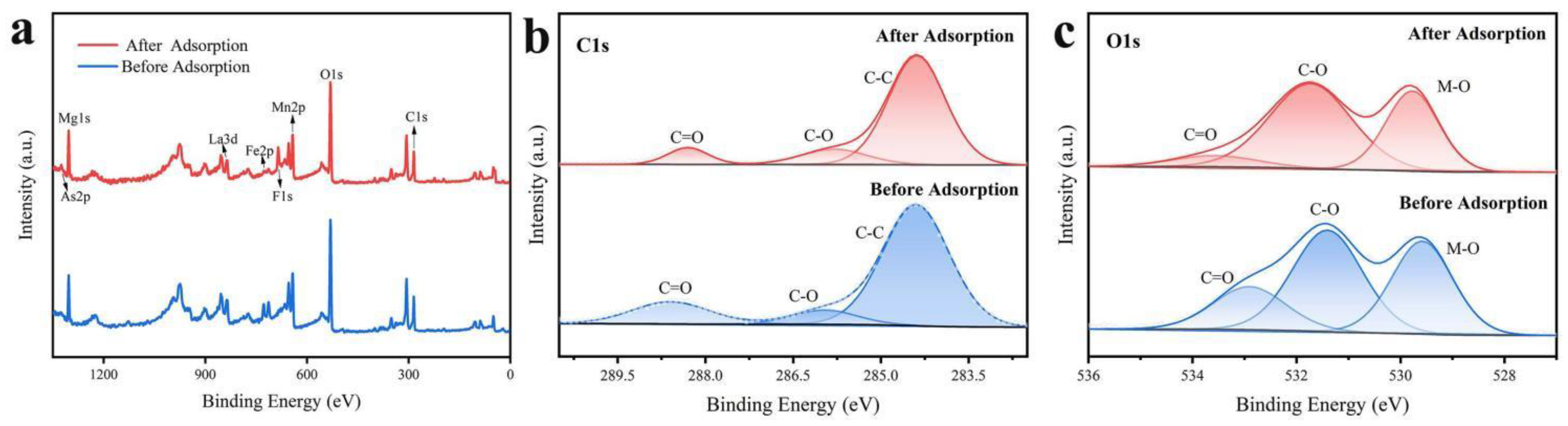

| Samples | C1s | O1s | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C=O | C-O | C-C | C=O | C-O | M-OH | |

| MnO2@LDO | 289.0 | 286.5 | 284.8 | 533.8 | 531.7 | 529.8 |

| MnO2@LDO after adsorption | 288.7 | 286.3 | 284.8 | 532.9 | 531.4 | 529.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).