Submitted:

09 December 2023

Posted:

11 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

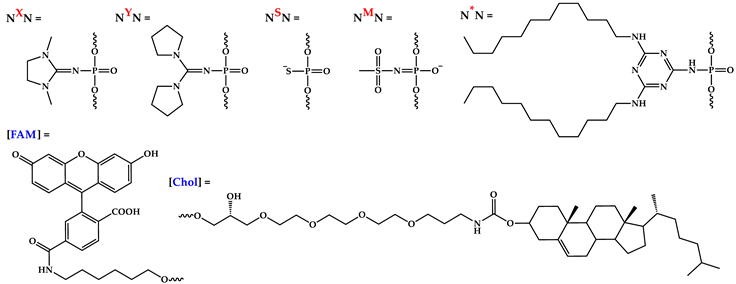

2.1. Design and synthesis of lipophilic phosphate-modified oligonucleotides

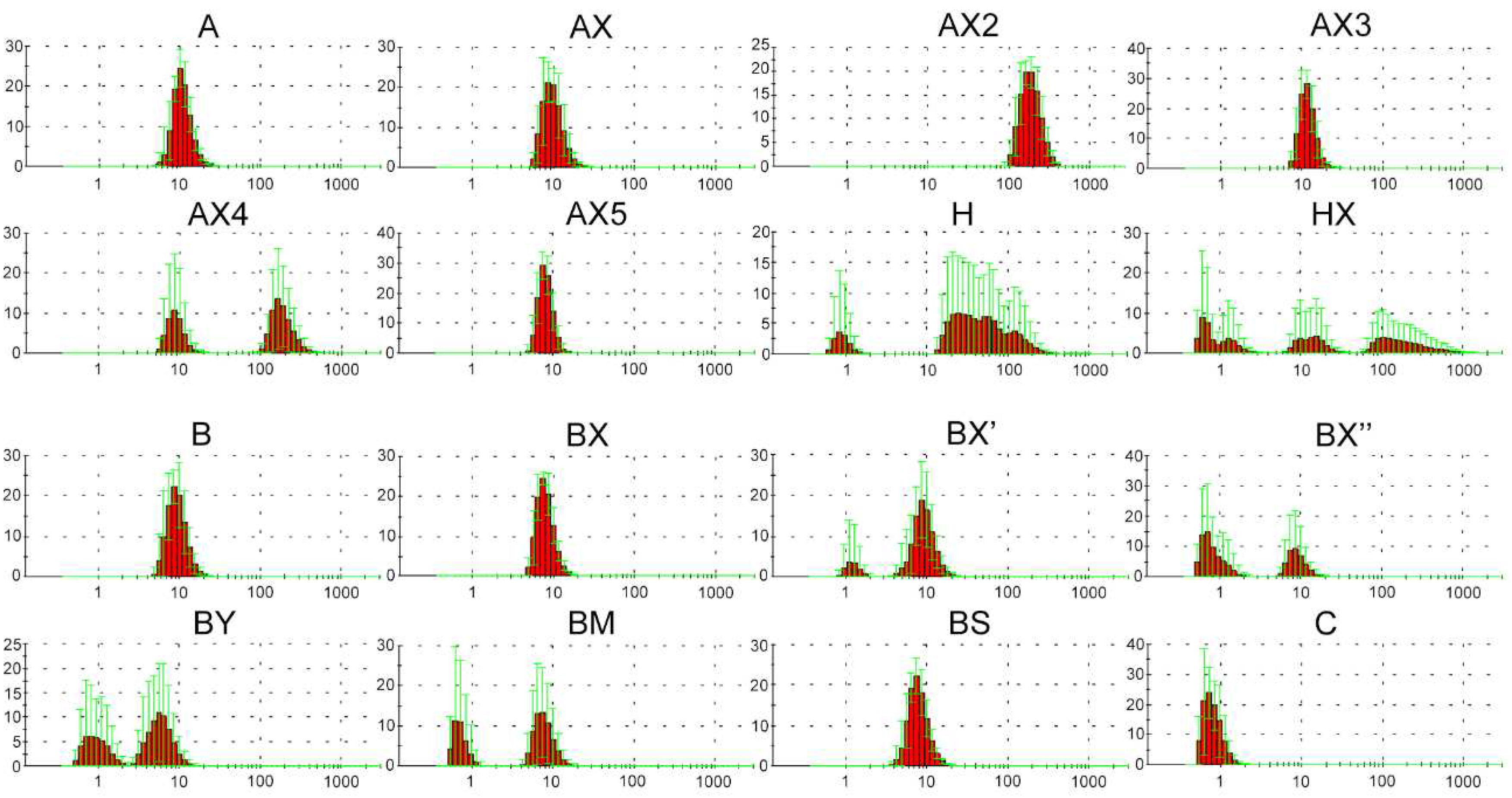

2.2. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis of supramolecular complexes of lipophilic phosphate-modified oligonucleotides

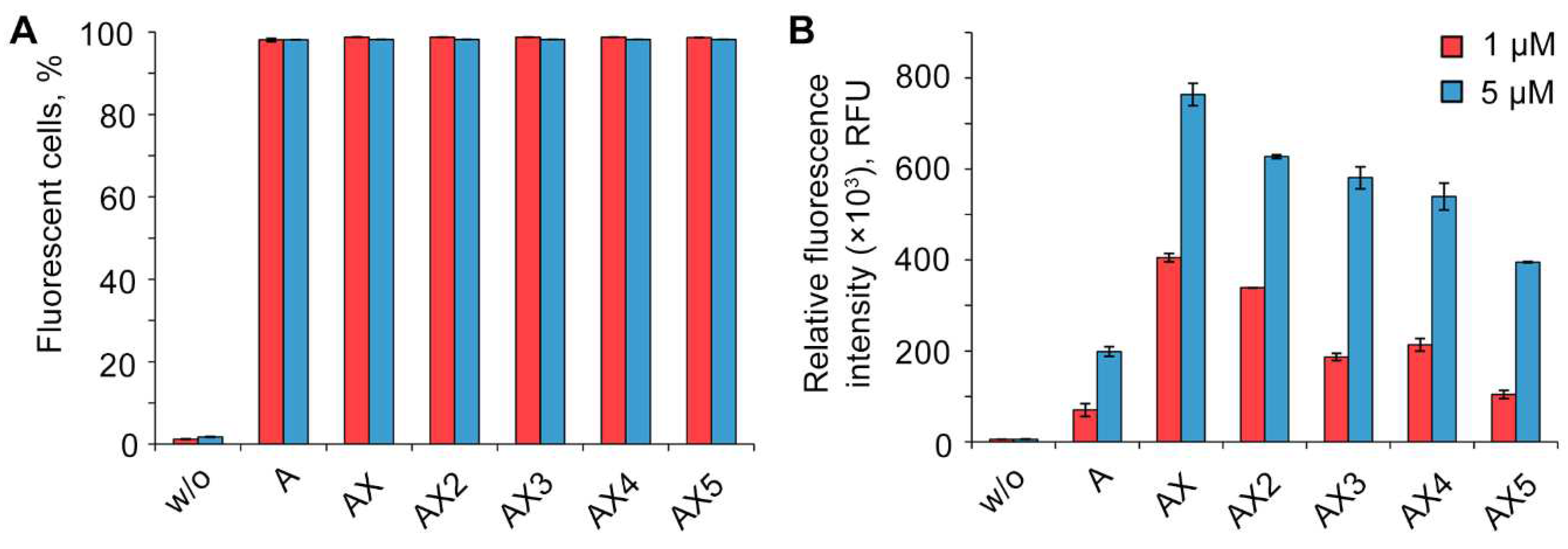

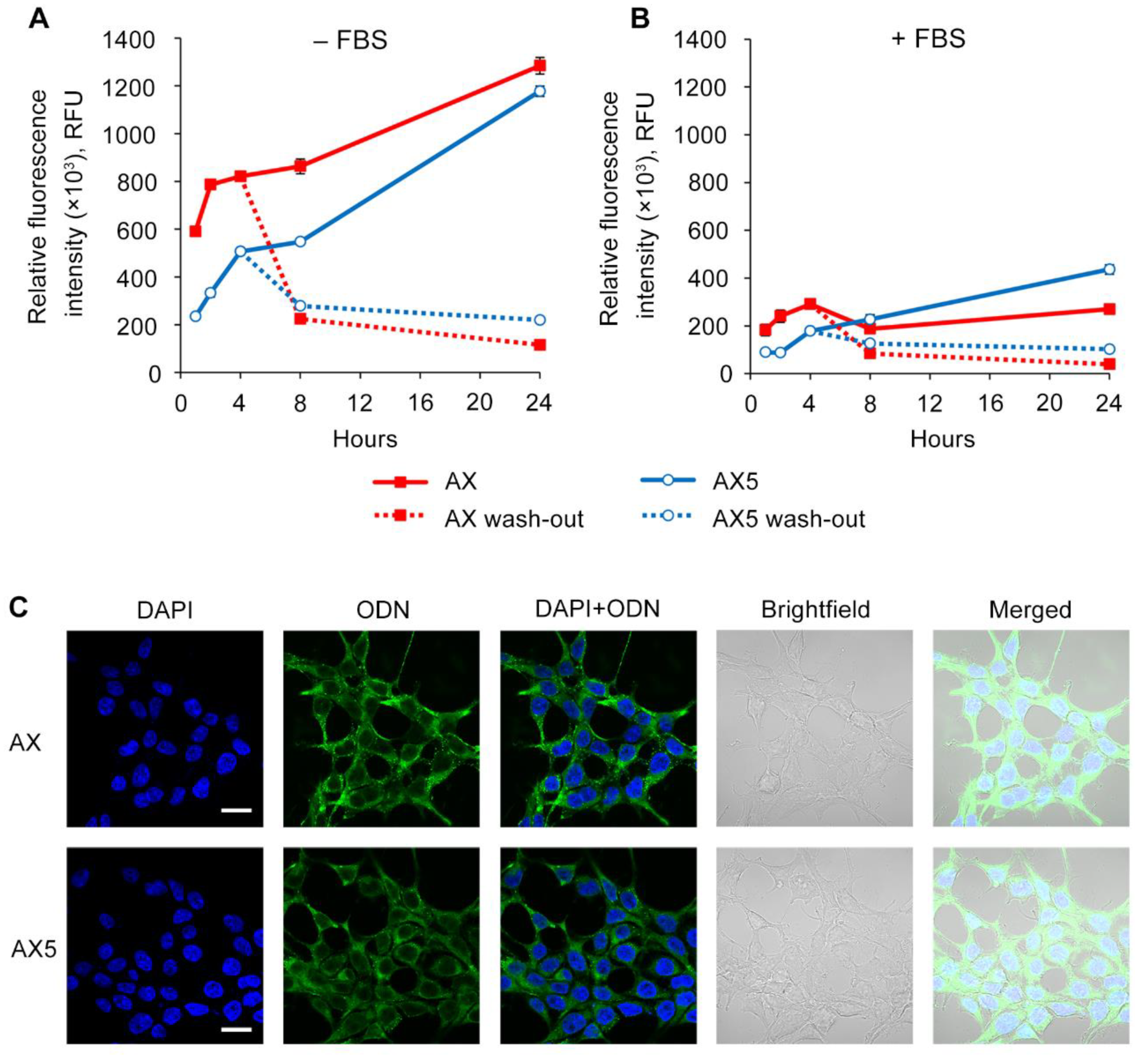

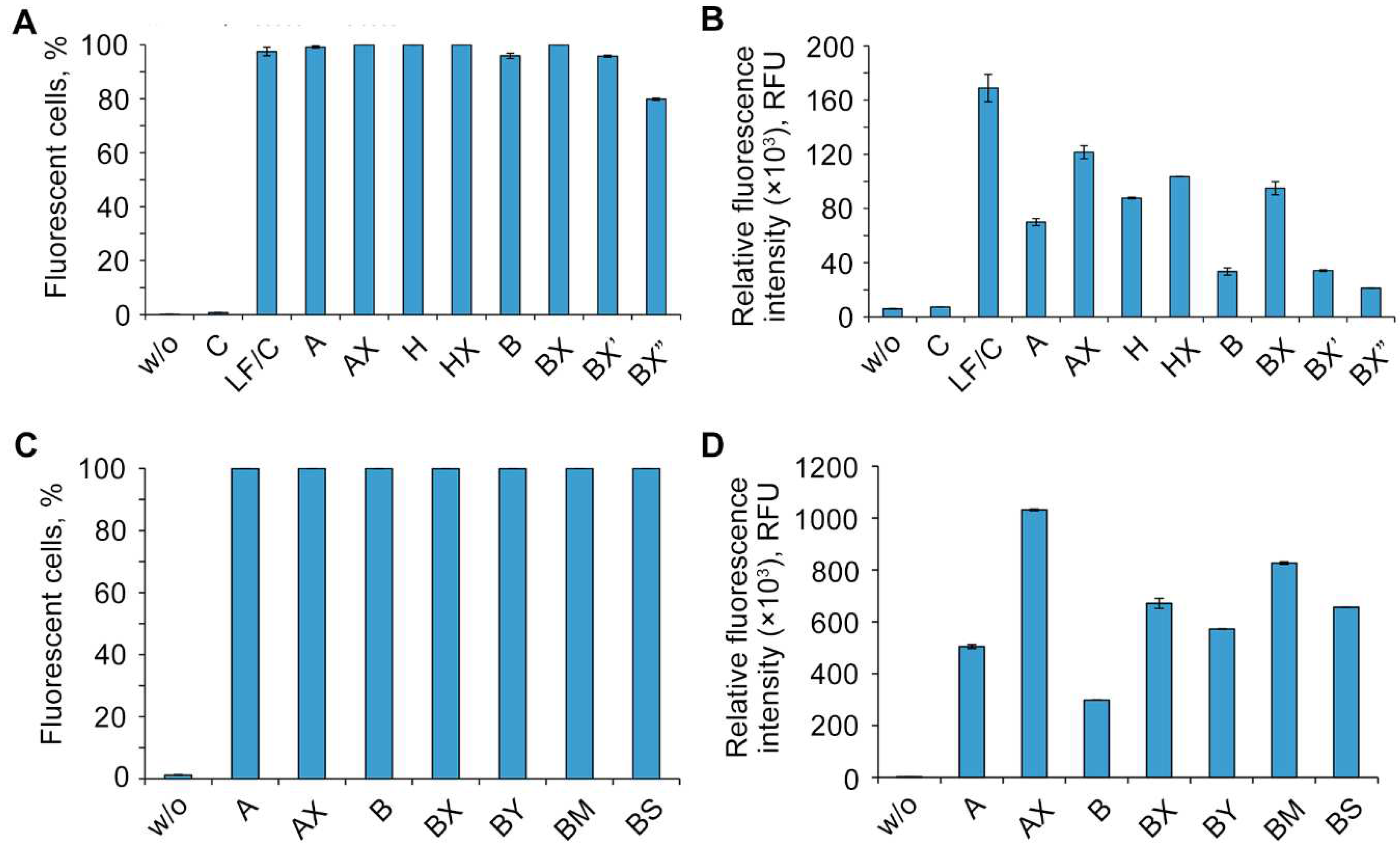

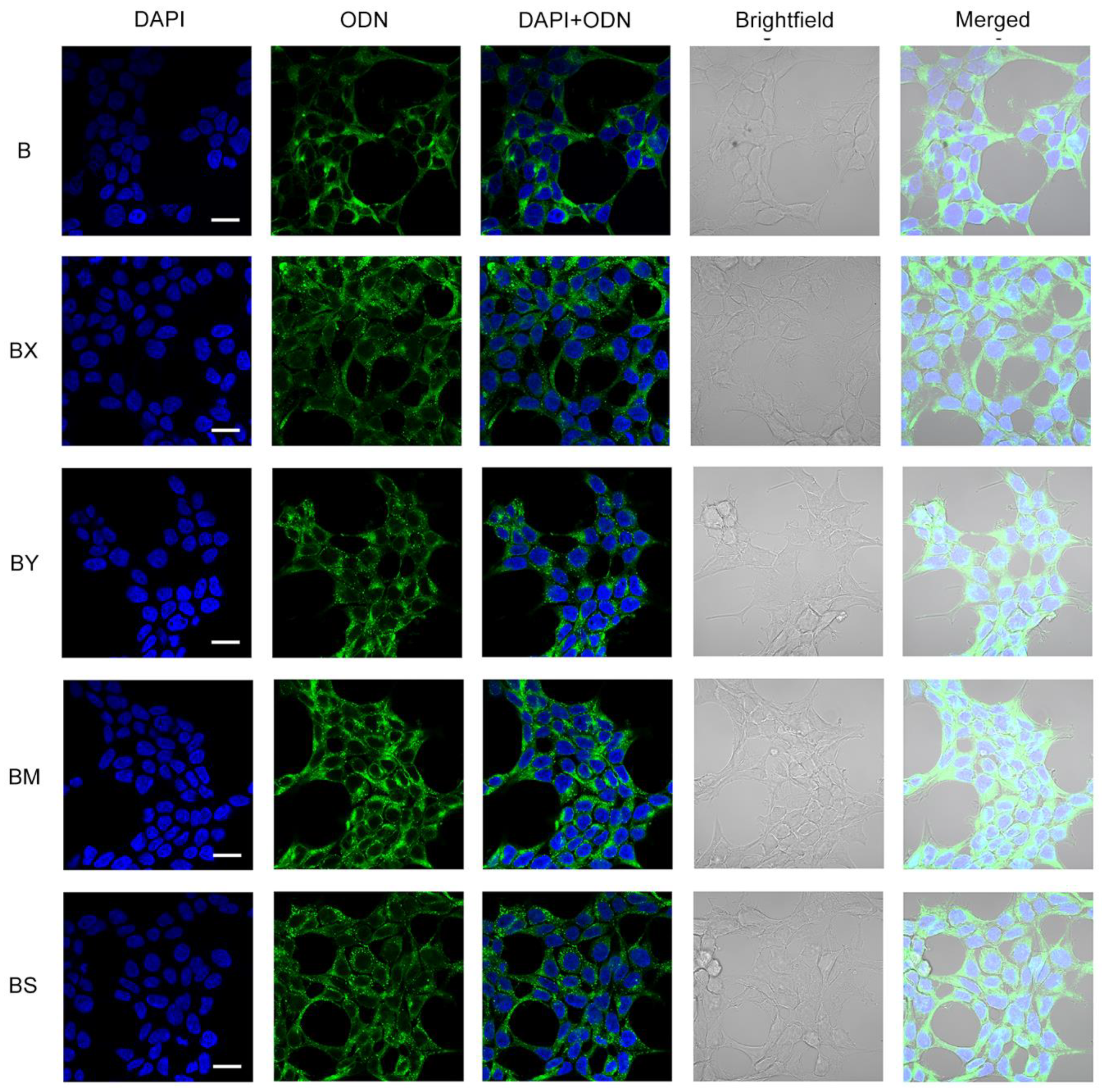

2.3. Study of the efficiency of intracellular accumulation of phosphate-modified oligonucleotides by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Oligonucleotide synthesis

4.2. Oligonucleotide Purification and Identification

4.3. Characterization of modified oligonucleotides by DLS

4.4. Analysis of Intracellular Accumulation of Oligonucleotides

4.5. Confocal microscopy

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Egli, M. and Manoharan, M. Chemistry, structure and function of approved oligonucleotide therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 2529-2573. [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. Future directions for medicinal chemistry in the field of oligonucleotide therapeutics. RNA 2023, 29, 423-433. doi: 10.1261/rna.079511.122.

- Thakur, S.; Sinhari, A.; Jain, P.; Jadhav, H. R., A perspective on oligonucleotide therapy: Approaches to patient customization. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1006304. [CrossRef]

- Crooke, S. T.; Witztum, J. L.; Bennett, C. F.; Baker, B. F., RNA-Targeted Therapeutics. Cell Metab 2018, 27 (4), 714-739. [CrossRef]

- Helm, J.; Schols, L.; Hauser, S., Towards Personalized Allele-Specific Antisense Oligonucleotide Therapies for Toxic Gain-of-Function Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14 (8). [CrossRef]

- Moumne, L.; Marie, A. C.; Crouvezier, N., Oligonucleotide Therapeutics: From Discovery and Development to Patentability. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14 (2). [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C.; Wood, M. J. A., Antisense oligonucleotides: the next frontier for treatment of neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14 (1), 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T. C.; Langer, R.; Wood, M. J. A., Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020, 19 (10), 673-694. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. I. E.; Zain, R., Therapeutic Oligonucleotides: State of the Art. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2019, 59, 605-630. [CrossRef]

- Benizri, S.; Gissot, A.; Martin, A.; Vialet, B.; Grinstaff, M. W.; Barthelemy, P., Bioconjugated Oligonucleotides: Recent Developments and Therapeutic Applications. Bioconjug Chem 2019, 30 (2), 366-383. [CrossRef]

- Quemener, A. M.; Centomo, M. L.; Sax, S. L.; Panella, R., Small Drugs, Huge Impact: The Extraordinary Impact of Antisense Oligonucleotides in Research and Drug Development. Molecules 2022, 27 (2). [CrossRef]

- Crooke, S. T.; Baker, B. F.; Crooke, R. M.; Liang, X. H., Antisense technology: an overview and prospectus. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20 (6), 427-453. [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, M.E., Jackson, M., Low, A., A, E.C., R, G.L., Peralta, R.Q., Yu, J., Kinberger, G.A., Dan, A., Carty, R. et al. Conjugation of hydrophobic moieties enhances potency of antisense oligonucleotides in the muscle of rodents and non-human primates. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 6045-6058. [CrossRef]

- Pollak, A.J., Zhao, L. and Crooke, S.T. Systematic Analysis of Chemical Modifications of Phosphorothioate Antisense Oligonucleotides that Modulate Their Innate Immune Response. Nucleic Acid Ther 2023, 33, 95-107. [CrossRef]

- Wolfrum, C., Shi, S., Jayaprakash, K.N., Jayaraman, M., Wang, G., Pandey, R.K., Rajeev, K.G., Nakayama, T., Charrise, K., Ndungo, E.M. et al. Mechanisms and optimization of in vivo delivery of lipophilic siRNAs. Nat Biotechnol 2007, 25, 1149-1157. [CrossRef]

- Osborn, M.F., Coles, A.H., Biscans, A., Haraszti, R.A., Roux, L., Davis, S., Ly, S., Echeverria, D., Hassler, M.R., Godinho, B. et al. Hydrophobicity drives the systemic distribution of lipid-conjugated siRNAs via lipid transport pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 1070-1081. [CrossRef]

- Biscans, A., Coles, A., Haraszti, R., Echeverria, D., Hassler, M., Osborn, M. and Khvorova, A. Diverse lipid conjugates for functional extra-hepatic siRNA delivery in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 1082-1096. [CrossRef]

- Raouane, M., Desmaele, D., Urbinati, G., Massaad-Massade, L. and Couvreur, P. Lipid conjugated oligonucleotides: a useful strategy for delivery. Bioconjug Chem 2012, 23, 1091-1104. [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, F., Phosphorothioates, essential components of therapeutic oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Ther 2014, 24 (6), 374-87. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, A. M.; Casper, M. D.; Freier, S. M.; Lesnik, E. A.; Zounes, M. C.; Cummins, L. L.; Gonzalez, C.; Cook, P. D., Uniformly modified 2'-deoxy-2'-fluoro phosphorothioate oligonucleotides as nuclease-resistant antisense compounds with high affinity and specificity for RNA targets. J Med Chem 1993, 36 (7), 831-41. [CrossRef]

- Crooke, S. T.; Seth, P. P.; Vickers, T. A.; Liang, X. H., The Interaction of Phosphorothioate-Containing RNA Targeted Drugs with Proteins Is a Critical Determinant of the Therapeutic Effects of These Agents. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142 (35), 14754-14771. [CrossRef]

- Crooke, S. T.; Vickers, T. A.; Liang, X. H., Phosphorothioate modified oligonucleotide-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48 (10), 5235-5253. [CrossRef]

- Guzaev, A. P, Reactivity of 3H-1,2,4-dithiazole-3-thiones and 3H-1,2-dithiole-3-thiones as sulfurizing agents for oligonucleotide synthesis. Tetrahedron Letters 2011, 52 (3), 434–437. [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, S. K.; Patutina, O. A.; Burakova, E. A.; Chelobanov, B. P.; Fokina, A. A.; Vlassov, V. V.; Altman, S.; Zenkova, M. A.; Stetsenko, D. A., Mesyl phosphoramidate antisense oligonucleotides as an alternative to phosphorothioates with improved biochemical and biological properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116 (4), 1229-1234. [CrossRef]

- Santorelli, A.; Gothelf, K. V., Conjugation of chemical handles and functional moieties to DNA during solid phase synthesis with sulfonyl azides. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50 (13), 7235-7246. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R. A.; Marcher, A.; Pedersen, K. N.; Gothelf, K. V., Insertion of Chemical Handles into the Backbone of DNA during Solid-Phase Synthesis by Oxidative Coupling of Amines to Phosphites. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2023, 62 (26), e202305373. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. A.; Freestone, G. C.; Low, A.; De-Hoyos, C. L.; Iii, W. J. D.; Ostergaard, M. E.; Migawa, M. T.; Fazio, M.; Wan, W. B.; Berdeja, A.; Scandalis, E.; Burel, S. A.; Vickers, T. A.; Crooke, S. T.; Swayze, E. E.; Liang, X.; Seth, P. P., Towards next generation antisense oligonucleotides: mesylphosphoramidate modification improves therapeutic index and duration of effect of gapmer antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49 (16), 9026-9041. [CrossRef]

- Vlaho, D.; Fakhoury, J. F.; Damha, M. J., Structural Studies and Gene Silencing Activity of siRNAs Containing Cationic Phosphoramidate Linkages. Nucleic Acid Ther 2018, 28 (1), 34-43. [CrossRef]

- Stetsenko, D.; Chelobanov, B., Fokina, A., Burakova, E. Modified oligonucleotides activating RNAse H. International Patent No. WO2018156056A1, 30 August 2018.

- Paul, S.; Roy, S.; Monfregola, L.; Shang, S.; Shoemaker, R.; Caruthers, M. H., Oxidative substitution of boranephosphonate diesters as a route to post-synthetically modified DNA. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137 (9), 3253-64. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Paul, S.; Roy, M.; Kundu, R.; Monfregola, L.; Caruthers, M. H., Pyridinium Boranephosphonate Modified DNA Oligonucleotides. J Org Chem 2017, 82 (3), 1420-1427. [CrossRef]

- Chatelain, G.; Meyer, A.; Morvan, F.; Vasseur, J. J.; Chaix, C., Electrochemical detection of nucleic acids using pentaferrocenyl phosphoramidate α-oligonucleotides. New Journal of Chemistry 2011, 35(4), 893-901. DOI . [CrossRef]

- Vlaho, D.; Damha, M. J., Synthesis of Chimeric Oligonucleotides Having Modified Internucleotide Linkages via an Automated H-Phosphonate/Phosphoramidite Approach. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem 2018, 73 (1), e53. [CrossRef]

- Kupryushkin, M. S., Zharkov, T. D., Ilina, E. S., Markov, O. V., Kochetkova, A. S., Akhmetova, M. M., ... & Khodyreva, S. N, Triazinylamidophosphate Oligonucleotides: Synthesis and Study of Their Interaction with Cells and DNA-Binding Proteins. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry 2021, 47 (3), 719-733. [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, S. A., Pyshnyi, D. V., & Kupryushkin, M. S, Synthesis of novel representatives of phosphoryl guanidine oligonucleotides. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry 2021, 47(2), 380-389. [CrossRef]

- Markov, O. V.; Filatov, A. V.; Kupryushkin, M. S.; Chernikov, I. V.; Patutina, O. A.; Strunov, A. A.; Chernolovskaya, E. L.; Vlassov, V. V.; Pyshnyi, D. V.; Zenkova, M. A., Transport Oligonucleotides-A Novel System for Intracellular Delivery of Antisense Therapeutics. Molecules 2020, 25 (16). [CrossRef]

- Zharkov, T. D.; Mironova, E. M.; Markov, O. V.; Zhukov, S. A.; Khodyreva, S. N.; Kupryushkin, M. S., Fork- and Comb-like Lipophilic Structures: Different Chemical Approaches to the Synthesis of Oligonucleotides with Multiple Dodecyl Residues. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24 (19). [CrossRef]

- Stetsenko, D.; Kupryushkin, M.; Pyshnyi, D. Modified Oligonucleotides and Methods for Their Synthesis. International Patent No. WO2016028187A1, 22 June 2014.

- Kupryushkin, M.; Zharkov, T.; Dovydenko, I.; Markov, O. Chemical compound comprising a triazine group and method for producing same. International Patent No. WO2022081046A1, 21 April 2022.

- Craig, K.; Abrams, M.; Amiji, M., Recent preclinical and clinical advances in oligonucleotide conjugates. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2018, 15 (6), 629-640. [CrossRef]

- Khvorova, A.; Watts, J. K., The chemical evolution of oligonucleotide therapies of clinical utility. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35 (3), 238-248. [CrossRef]

- Hnedzko, D.; McGee, D. W.; Karamitas, Y. A.; Rozners, E., Sequence-selective recognition of double-stranded RNA and enhanced cellular uptake of cationic nucleobase and backbone-modified peptide nucleic acids. RNA 2017, 23 (1), 58-69. doi: 10.1261/rna.058362.116.

- Baker, Y. R.; Thorpe, C.; Chen, J.; Poller, L. M.; Cox, L.; Kumar, P.; Lim, W. F.; Lie, L.; McClorey, G.; Epple, S.; Singleton, D.; McDonough, M. A.; Hardwick, J. S.; Christensen, K. E.; Wood, M. J. A.; Hall, J. P.; El-Sagheer, A. H.; Brown, T., An LNA-amide modification that enhances the cell uptake and activity of phosphorothioate exon-skipping oligonucleotides. Nat Commun 2022, 13 (1), 4036. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, P.; Liu, Y.; Aduda, V.; Akare, S.; Alam, R.; Andreucci, A.; Boulay, D.; Bowman, K.; Byrne, M.; Cannon, M.; Chivatakarn, O.; Shelke, J. D.; Iwamoto, N.; Kawamoto, T.; Kumarasamy, J.; Lamore, S.; Lemaitre, M.; Lin, X.; Longo, K.; Looby, R.; Marappan, S.; Metterville, J.; Mohapatra, S.; Newman, B.; Paik, I. H.; Patil, S.; Purcell-Estabrook, E.; Shimizu, M.; Shum, P.; Standley, S.; Taborn, K.; Tripathi, S.; Yang, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dale, E.; Vargeese, C., Impact of guanidine-containing backbone linkages on stereopure antisense oligonucleotides in the CNS. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50 (10), 5401-5423. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, P.; McClorey, G.; Shimizu, M.; Kothari, N.; Alam, R.; Iwamoto, N.; Kumarasamy, J.; Bommineni, G. R.; Bezigian, A.; Chivatakarn, O.; Butler, D. C. D.; Byrne, M.; Chwalenia, K.; Davies, K. E.; Desai, J.; Shelke, J. D.; Durbin, A. F.; Ellerington, R.; Edwards, B.; Godfrey, J.; Hoss, A.; Liu, F.; Longo, K.; Lu, G.; Marappan, S.; Oieni, J.; Paik, I. H.; Estabrook, E. P.; Shivalila, C.; Tischbein, M.; Kawamoto, T.; Rinaldi, C.; Rajao-Saraiva, J.; Tripathi, S.; Yang, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, J.; Apponi, L.; Wood, M. J. A.; Vargeese, C., Control of backbone chemistry and chirality boost oligonucleotide splice switching activity. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50 (10), 5443-5466. [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; De Hoyos, C. L.; Migawa, M. T.; Vickers, T. A.; Sun, H.; Low, A.; Bell, T. A., 3rd; Rahdar, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Hart, C. E.; Bell, M.; Riney, S.; Murray, S. F.; Greenlee, S.; Crooke, R. M.; Liang, X. H.; Seth, P. P.; Crooke, S. T., Chemical modification of PS-ASO therapeutics reduces cellular protein-binding and improves the therapeutic index. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37 (6), 640-650. [CrossRef]

- Maguregui, A.; Abe, H., Developments in siRNA Modification and Ligand Conjugated Delivery To Enhance RNA Interference Ability. Chembiochem 2020, 21 (13), 1808-1815. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhong, L.; Weng, Y.; Peng, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, X. J., Therapeutic siRNA: state of the art. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5 (1), 101. [CrossRef]

- Kenski, D. M.; Butora, G.; Willingham, A. T.; Cooper, A. J.; Fu, W.; Qi, N.; Soriano, F.; Davies, I. W.; Flanagan, W. M., siRNA-optimized Modifications for Enhanced In Vivo Activity. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2012, 1 (1), e5. [CrossRef]

- Ly, S.; Echeverria, D.; Sousa, J.; Khvorova, A., Single-Stranded Phosphorothioated Regions Enhance Cellular Uptake of Cholesterol-Conjugated siRNA but Not Silencing Efficacy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020, 21, 991-1005. [CrossRef]

- Watts, J. K.; Deleavey, G. F.; Damha, M. J., Chemically modified siRNA: tools and applications. Drug Discov Today 2008, 13 (19-20), 842-55. [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, A. S.; Yakovleva, K. I.; Epanchitseva, A. V.; Kupryushkin, M. S.; Pyshnaya, I. A.; Pyshnyi, D. V.; Ryabchikova, E. I.; Dovydenko, I. S., An Influence of Modification with Phosphoryl Guanidine Combined with a 2'-O-Methyl or 2'-Fluoro Group on the Small-Interfering-RNA Effect. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22 (18). [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Iwamoto, N.; Marappan, S.; Luu, K.; Tripathi, S.; Purcell-Estabrook, E.; Shelke, J. D.; Shah, H.; Lamattina, A.; Pan, Q.; Schrand, B.; Favaloro, F.; Bedekar, M.; Chatterjee, A.; Desai, J.; Kawamoto, T.; Lu, G.; Metterville, J.; Samaraweera, M.; Prakasha, P. S.; Yang, H.; Yin, Y.; Yu, H.; Giangrande, P. H.; Byrne, M.; Kandasamy, P.; Vargeese, C., Impact of stereopure chimeric backbone chemistries on the potency and durability of gene silencing by RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51 (9), 4126-4147. [CrossRef]

- Monian, P.; Shivalila, C.; Lu, G.; Shimizu, M.; Boulay, D.; Bussow, K.; Byrne, M.; Bezigian, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Chew, D.; Desai, J.; Favaloro, F.; Godfrey, J.; Hoss, A.; Iwamoto, N.; Kawamoto, T.; Kumarasamy, J.; Lamattina, A.; Lindsey, A.; Liu, F.; Looby, R.; Marappan, S.; Metterville, J.; Murphy, R.; Rossi, J.; Pu, T.; Bhattarai, B.; Standley, S.; Tripathi, S.; Yang, H.; Yin, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhou, C.; Apponi, L. H.; Kandasamy, P.; Vargeese, C., Endogenous ADAR-mediated RNA editing in non-human primates using stereopure chemically modified oligonucleotides. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40 (7), 1093-1102. [CrossRef]

- Kupryushkin, M. S.; Filatov, A. V.; Mironova, N. L.; Patutina, O. A.; Chernikov, I. V.; Chernolovskaya, E. L.; Zenkova, M. A.; Pyshnyi, D. V.; Stetsenko, D. A.; Altman, S.; Vlassov, V. V., Antisense oligonucleotide gapmers containing phosphoryl guanidine groups reverse MDR1-mediated multiple drug resistance of tumor cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 211-226. [CrossRef]

- Krutzfeldt, J.; Rajewsky, N.; Braich, R.; Rajeev, K. G.; Tuschl, T.; Manoharan, M.; Stoffel, M., Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with 'antagomirs'. Nature 2005, 438 (7068), 685-9. [CrossRef]

- Wada, S.; Yasuhara, H.; Wada, F.; Sawamura, M.; Waki, R.; Yamamoto, T.; Harada-Shiba, M.; Obika, S., Evaluation of the effects of chemically different linkers on hepatic accumulations, cell tropism and gene silencing ability of cholesterol-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides. J Control Release 2016, 226, 57-65. [CrossRef]

- Chernikov, I. V.; Gladkikh, D. V.; Meschaninova, M. I.; Ven’yaminova, A. G.; Zenkova, M. A.; Vlassov, V. V.; Chernolovskaya, E. L., Cholesterol-Containing Nuclease-Resistant siRNA Accumulates in Tumors in a Carrier-free Mode and Silences MDR1 Gene. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017, 6, 209-220. [CrossRef]

- LeDoan, T.; Etore, F.; Tenu, J. P.; Letourneux, Y.; Agrawal, S., Cell binding, uptake and cytosolic partition of HIV anti-gag phosphodiester oligonucleotides 3'-linked to cholesterol derivatives in macrophages. Bioorg Med Chem 1999, 7 (11), 2263-9. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Chang, C.; Kim, J. H.; Oh, C. T.; Lee, H. N.; Lee, C.; Oh, D.; Kim, B.; Hong, S. W.; Lee, D. K., Development of Cell-Penetrating Asymmetric Interfering RNA Targeting Connective Tissue Growth Factor. J Invest Dermatol 2016, 136 (11), 2305-2313. [CrossRef]

- Soutschek, J.; Akinc, A.; Bramlage, B.; Charisse, K.; Constien, R.; Donoghue, M.; Elbashir, S.; Geick, A.; Hadwiger, P.; Harborth, J.; John, M.; Kesavan, V.; Lavine, G.; Pandey, R. K.; Racie, T.; Rajeev, K. G.; Rohl, I.; Toudjarska, I.; Wang, G.; Wuschko, S.; Bumcrot, D.; Koteliansky, V.; Limmer, S.; Manoharan, M.; Vornlocher, H. P., Therapeutic silencing of an endogenous gene by systemic administration of modified siRNAs. Nature 2004, 432 (7014), 173-8. [CrossRef]

- Heindl, D.; Kessler, D.; Schube, A.; Thuer, W.; Giraut, A., Easy method for the synthesis of labeled oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2008, (52), 405-6. [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, A.S.; Dovydenko, I.S.; Kupryushkin, M.S.; Grigor’eva, A.E.; Pyshnaya, I.A.; Pyshnyi, D.V.; Amphiphilic “like-a-brush” oligonucleotide conjugates with three dodecyl chains: Self-assembly features of novel scaffold compounds for nucleic acids de-livery. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1948. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Tanioku, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Aso, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kamada, H.; Obika, S., Synthesis of multivalent fatty acid-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides: Cell internalization, physical properties, and in vitro and in vivo activities. Bioorg Med Chem 2023, 81, 117192. [CrossRef]

- Gooding, M.; Malhotra, M.; Evans, J. C.; Darcy, R.; O'Driscoll, C. M., Oligonucleotide conjugates - Candidates for gene silencing therapeutics. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2016, 107, 321-40. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Sheng, G.; Wang, J.; Lu, P.; Wang, Y., Preparation of triazoloindoles via tandem copper catalysis and their utility as alpha-imino rhodium carbene precursors. Org Lett 2014, 16 (4), 1244-7. [CrossRef]

| Code | Sequence 5′→3′ | MS (calc / found) |

|---|---|---|

| A | 5′-[FAM]CTGACTATGAAGTAT*T-3′ | 5877.5 / 5876.5 |

| AX | 5′-[FAM]XCXTGACTATGAAGTAT*T-3′ | 6067.8 / 6067.6 |

| AX2 | 5′-[FAM] XCXTXGXACTATGAAGTAT*T-3′ | 6254.8 / 6253.8 |

| AX3 | 5′-[FAM] XCXTXGXAXCXTATGAAGTAT*T-3′ | 6444.9 / 6446.0 |

| AX4 | 5′-[FAM] XCXTXGXAXCXTXAXTGAAGTAT*T-3′ | 6635.1 / 6637.0 |

| AX5 | 5′-[FAM]XCXTXGXAXCXTXAXTXGXAAGTAT*T-3′ | 6825.3 / 6827.0 |

| H | 5′-[FAM]CTGACTATGAAGTATT[Chol]-3′ | 6188.7 / 6189.0 |

| HX | 5′-[FAM]XCXTGACTATGAAGTATT[Chol]-3′ | 6375.6 / 6376.5 |

| B | 5′-[FAM]AGTCTCGACTTGCTAT*T-3′ | 6130.4 / 6132.0 |

| BX | 5′-[FAM]XAXGTCTCGACTTGCTAT*T-3′ | 6320.6 / 6321.6 |

| BX’ | 5′-[FAM]AGTCTCGXAXCTTGCTAT*T-3′ | 6320.6 / 6322.0 |

| BX’’ | 5′-[FAM]AGTCTCGACTTGCTXAXT*T-3′ | 6320.6 / 6322.0 |

| BY | 5′-[FAM]YAYGTCTCGACTTGCTAT*T-3′ | 6428.7 / 6430.0 |

| BM | 5′-[FAM]MAMGTCTCGACTTGCTAT*T-3′ | 6284.4 / 6286.0 |

| BS | 5′-[FAM]SASGTCTCGACTTGCTAT*T-3′ | 6162.4 / 6163.5 |

| C | 5′-[FAM]AGTCTCGACTTGCTATT-3′ | 5686.0 / n.d. |

| ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).