Submitted:

08 December 2023

Posted:

11 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Climate Conditions

2.2. Soil Sampling and Analysis

2.3. Leaf Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

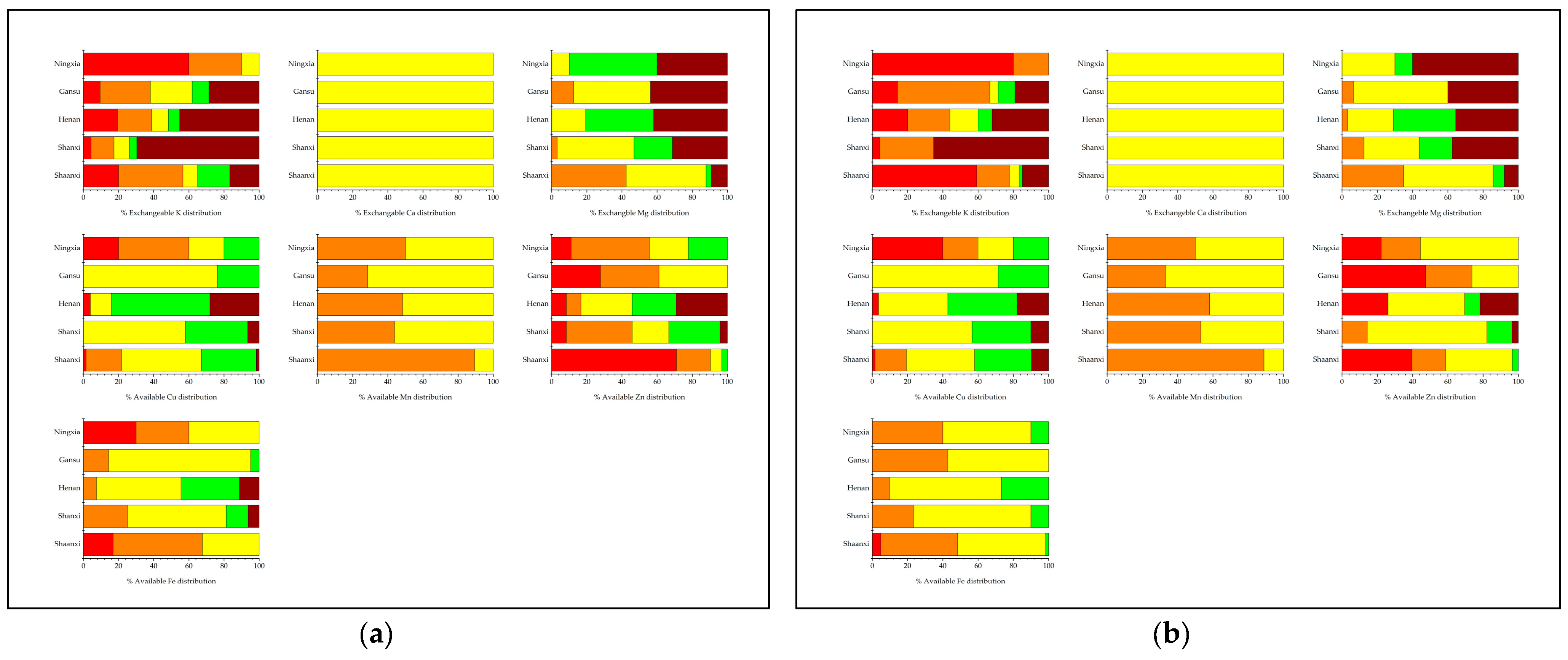

3.1. Soil pH, Exchangeable K, Ca, Mg, and Micronutrients Status and Spatial Distribution of the Main Apple Production Areas in the Loess Plateau, China

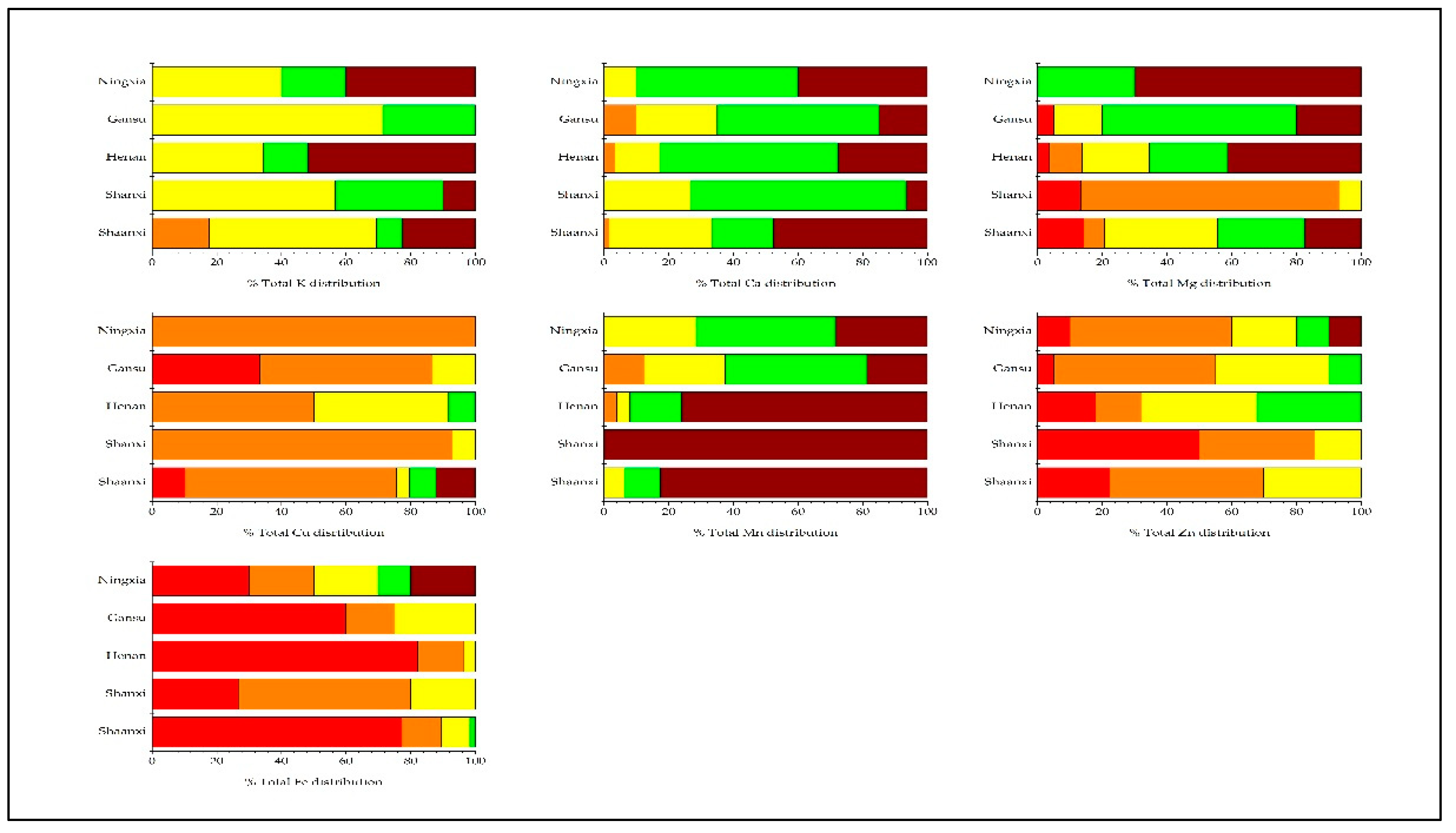

3.2. Evaluation of Leaf K, Ca, Mg, and Micronutrients Status and Spatial Distribution of the Main Apple Production Areas in the Loess Plateau, China

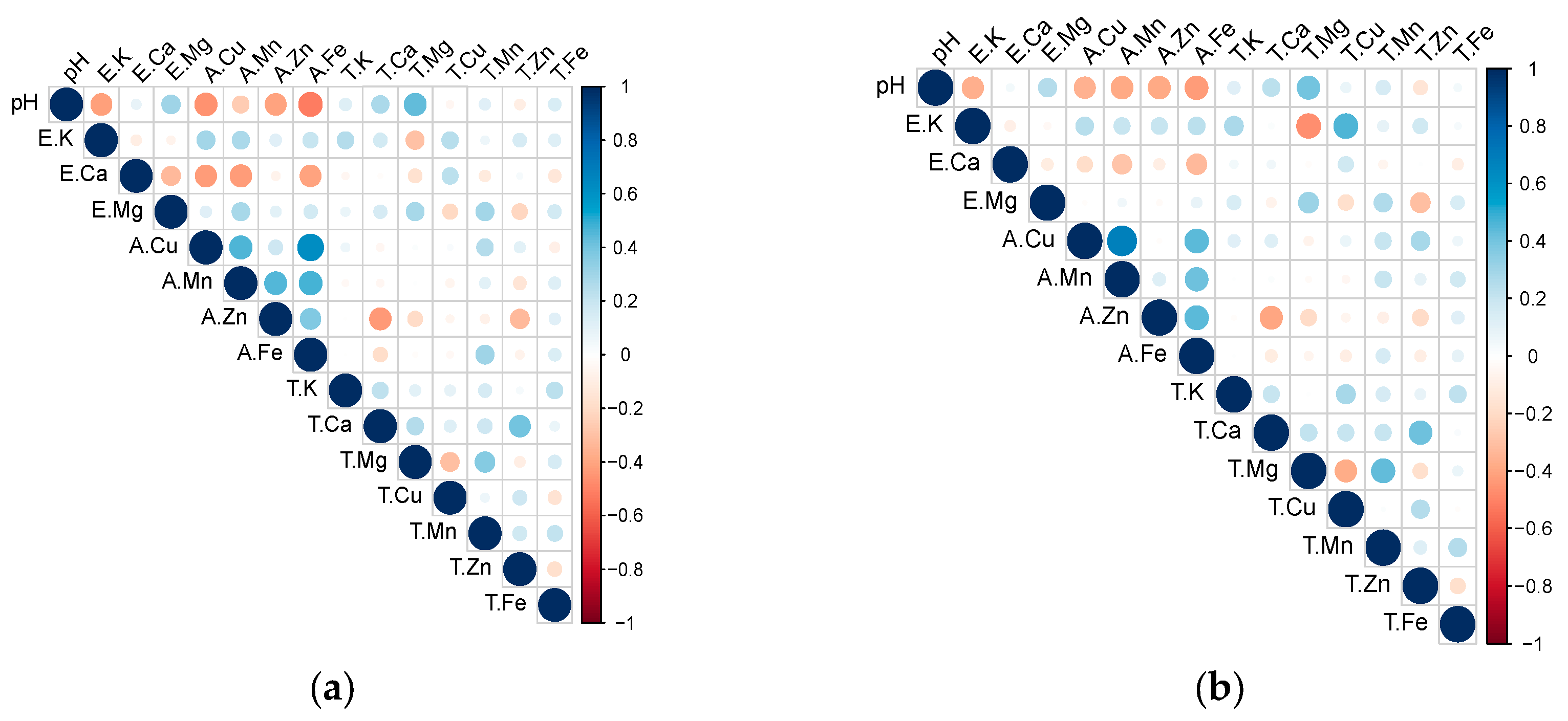

3.3. Relationship between Soil Nutrients and Leaf Nutrients for the Main Apple Production Areas in the Loess Plateau, China

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil pH, Exchangeable K, Ca, and Mg of Apple Orchard in the Loess Plateau

4.2. Soil Cu, Mn, Zn, and Fe of Apple Orchard in the Loess Plateaus

4.3. Leaf K, Ca, and Mg of Apple Orchard in the Loess Plateau

4.4. Leaf Cu, Mn, Zn, and Fe of Apple Orchard in the Loess Plateaus

4.5. Relationship between Soil Nutrients and Leaf Nutrients for the Main Apple Production Areas in the Loess Plateau, China

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). Statistical Databases. Availabe online: http://www.fao.org (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China). National Database. Availabe online: http://www.stats.gov.cn (accessed on (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Han, M. Theory and practice of apple development regulation in the Loess Plateau. China Agriculture, Beijing 2015.

- Zhang, H. My opinion on the Loess Plateau is the core producing region of high-quality apple in China. China Fruits 2019, 1, 114116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C. Spatial pattern evolution and its driving factors for apple industry in China: Based on micro perspective of farmers’ decision making. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment 2017, 31, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, Y. Long-term impact of fertilization on soil pH and fertility in an apple production system. Journal of soil science and plant nutrition 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, P.; Zhai, B.; Zhou, J. Soil moisture decline and residual nitrate accumulation after converting cropland to apple orchard in a semiarid region: Evidence from the Loess Plateau. CATENA 2019, 181, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Jin, L.; Wu, R. Assessing current conditions of fertilization on apple orchard in the Loess Plateau. Shanxi J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 63, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Shi, J.; Zeng, L.; Xu, J.; Wu, L. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on the acidity and salinity of greenhouse soils. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2015, 22, 2976–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, S.; Fang, X. Nitrogen balance under different nitrogen application rates in young apple orchards. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science 2011, 17, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H. Development status of fruit industry in China and several problems to be studied. Engineering Science 2003, 5, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, S.; Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, W. Changes of orchard soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in gully region of Loess Plateau. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science 2008, 14, 685–691. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, B.J. Micronutrients and crop production: An introduction. In Micronutrient deficiencies in global crop production; Springer, 2008; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodral-Segado, A.; Navarro-Alarcon, M.; De La Serrana, H.L.-G.; Lopez-Martinez, M. Calcium and magnesium levels in agricultural soil and sewage sludge in an industrial area from Southeastern Spain: relationship with plant (Saccharum officinarum) disposition. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal 2006, 15, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Khan, M.R.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Establishing grading indices of available soil potassium on paddy soils in Hubei province, China. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 16381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisdale, S.L.; Nelson, W.L.; Beaton, J.D. Soil fertility and fertilizers; Collier Macmillan Publishers, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R.; Miles, N.; Hughes, J.C. Interactions between potassium, calcium and magnesium in sugarcane grown on two contrasting soils in South Africa. Field Crops Research 2018, 223, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palo, F.; Fornara, D.A. Plant and soil nutrient stoichiometry along primary ecological successions. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0182569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, H.-C.; Li, S.-L.; Yan, Z.; Li, C. Understanding nutrient allocation based on leaf nitrogen isotopes and elemental ratios in the karst region of Southwest China. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 294, 106864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitondo, D.; FO, T.; Ngoucheme, M.; AD, M. Micronutrient concentrations and environmental concerns in an intensively cultivated typic dystrandept in Mount Bambouto, Cameroon. Open Journal of Soil Science 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.; Slaton, N.; Baligar, V. Nutrient management for improving lowland rice productivity and sustainability. Advances in agronomy 2003, 80, 63–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lucena, J.J. Effects of bicarbonate, nitrate and other environmental factors on iron deficiency chlorosis. A review. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2000, 23, 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenauer, H. Determination of plant-available soil manganese. In Proceedings of Manganese in Soils and Plants: Proceedings of the International Symposium on ‘Manganese in Soils and Plants’ held at the Waite Agricultural Research Institute, The University of Adelaide, Glen Osmond, South Australia, August 22–26, 1988 as an Australian Bicentennial Event; pp. 87-98. [CrossRef]

- Rengel, Z. GENOTYPIC DIFFERENCES IN MICRONUTRIENT USE EFFICIENCY IN CROPS. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2001, 32, 1163–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Rao, B.; Suresh, K.; Manoja, K. Soil nutrient status and leaf nutrient norms in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) plantations grown on southern plateau of India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences 2016, 86, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römheld, V. Chapter 11 ‐ Diagnosis of Deficiency and Toxicity of Nutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (Third Edition), Marschner, P., Ed. Academic Press: San Diego, 2012. 299–312. [CrossRef]

- Halvin, J.L.; Beaton, J.; Tisdale, S.; Nelson, W. Soil fertility and fertilizers: an introduction to nutrient management. Pretice Hall, New Jersey 2005.

- Futian, P.; Yuanmao, J. Characteristics of N, P, and K nutrition in different yield level apple orchards. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, S.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, L.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, Y. Soil Nutrient Status and Leaf Nutrient Diagnosis in the Main Apple Producing Regions in China. Horticultural Plant Journal 2018, 4, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiyang, A.; Chonghui, F.; Zhihui, D.; Junyi, Y.; Fengchan, D.; Lianrang, S. Analysis of effective factors of nutrient content in apple leaves. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 2006, 33, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Guiyang, A.; Lianrang, S.; Zhihui, D.; Junyi, Y.; Fengchan, D. Studies on the Standard Range of Apple Leaf Nutritional Elements in ShaanxiProvince. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 2004, 31, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Guo, D.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H. The contents of the microelements in leaves of apple and correlativity with firmness of fruit in West-He'nan area. Acta Agric Boreali-occidentalis Sin 2007, 16, 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, Z. Soil Nutrients of Apple Orchards in Major Production Area of Shaanxi. JOURNAL-NORTHWEST FORESTRY UNIVERSITY 2006, 21, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.-y.; Zhang, X.-z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.-f.; Han, Z.-h. Key minerals influencing apple quality in Chinese orchard identified by nutritional diagnosis of leaf and soil analysis. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2015, 14, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wei, Q.; Jiang, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Correlation analysis of fruit mineral nutrition contents with several key quality indicators in'Fuji'apple. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 2011, 38, 1963–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Gong, Q.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhai, B. Contents and distribution of soil organic matter and nitrogen, phosphate, potassium in the main apple production regions of Shaanxi Province. J. Plant Nutr. Fert 2017, 23, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Li-wei, Z.; Ming-yu, H.; Chen-xi, G.; Wen-wen, L.; Juan-juan, M. Studies of the standard range of the soil nutrients in apple orchard in Loess Plateau. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 2016, 43, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. Soil and agricultural chemistry analysis. Beijing: China agriculture press: 2000.

- Gangli, L.; Runyu, S.; Juan, S. Studies on the nutritional ranges in some deciduous fruit trees. Acta Horticulturae Sinica (China) 1987. [Google Scholar]

- WANG, G.-y.; ZHANG, X.-z.; Yi, W.; XU, X.-f.; HAN, Z.-h. Key minerals influencing apple quality in Chinese orchard identified by nutritional diagnosis of leaf and soil analysis. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2015, 14, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, F.; Gunal, H.; Acir, N. Spatial variability of soil potassium and its relationship to land use and parent material. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Mengel, K.; Kirkby, E. Principles of plant nutrition., 5th edn (Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands). 2001.

- Nie, P.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Xue, X.; Wang, J. Effects of different calcium foliage fertilizers and spraying period on apple bitter pit disease and fruit quality. J. Hebei Agric. Sci 2017, 21, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ghafoor, A.; Shahid, M.I.; Saghir, M.; Murtaza, G. Use of high-Mg brackish water on phosphogypsum and FYM treated saline-sodic soil. I. Soil improvement. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences 1992, 29, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Karajeh, F.; Karimov, A.; Mukhamedjanov, V.; Vyshpolsky, F.; Mukhamedjanov, K.; Ikramov, R.; Palvanov, T.; Novikova, A. Improved on-farm water management strategies in Central Asia. Agriculture in Central Asia: Research for Development. ICARDA, Aleppo, Syria, and Center for Development Research, Bonn 2004, 76-89.

- Cakmak, I. Plant nutrition research: Priorities to meet human needs for food in sustainable ways. Plant and Soil 2002, 247, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakouti, M. Zinc is a neglected element in the life cycle of plants. Middle Eastern and Russian Journal of Plant Science and Biotechnology 2007, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner, H. Mineral nutrition of higher plants 2nd edn. Institute of Plant Nutrition University of Hohenheim: Germany 1995. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Hao, M.; Shao, M.; Gale, W.J. Changes in soil properties and the availability of soil micronutrients after 18 years of cropping and fertilization. Soil and Tillage Research 2006, 91, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, C.; SHI, Y.; MA, L.; YE, Y.; YANG, J.; ZHANG, F. Effect of excessive copper on growth and metabolism of apple trees. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizers 2000, 6, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ma, P.; Xu, X. Comprehensive assessment of fertilization, spatial variability of soil chemical properties, and relationships among nutrients, apple yield and orchard age: A case study in Luochuan County, China. Ecological Indicators 2021, 122, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Jin, H.; Li, H.; Han, M. Influences of different rates of nitrogen on fruit quality, photosynthesis and element contents in leaves of red Fuji apples. Acta Agriculturae Boreli-occidentalis Sinica 2008, 17, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.-l.; Zhang, F.-s.; Jiang, X.-l.; Yu, Z.-f.; Wu, C.-n. Effects of different iron fertilizer on apple tree internal bark necrosis. JOURNAL-SHANDONG AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY 2003, 34, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Boaretto, A.E.; Boaretto, R.; Muraoka, T.; Nascimento Filho, V.F.d.; Tiritan, C.; Mourão Filho, F.d.A.A. Foliar micronutrient application effects on citrus fruit yield, soil and leaf Zn concentrations and 65Zn mobilization within the plant. In Proceedings of International Symposium on Foliar Nutrition of Perennial Fruit Plants 594; pp. 203–209. [CrossRef]

- Zekri, M.; Obreza, T.A. Micronutrient deficiencies in citrus: iron, zinc, and manganese; University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and …: 2003.

- Wang, R.; Dungait, J.A.; Buss, H.L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, Y. Base cations and micronutrients in soil aggregates as affected by enhanced nitrogen and water inputs in a semi-arid steppe grassland. Science of the total environment 2017, 575, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Zinc in soils and crop nutrition. 2008.

- Lindsay, W.L. Chemical equilibria in soils; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: 1979.

- Sims, J.T. Soil pH effects on the distribution and plant availability of manganese, copper, and zinc. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1986, 50, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengel, Z. Cycling of micronutrients in terrestrial ecosystems. In Nutrient cycling in terrestrial ecosystems, Springer: 2007; pp. 93-121. [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Cai, A.; Liu, K.; Huang, J.; Wang, B.; Li, D.; Qaswar, M.; Feng, G.; Zhang, H. The links between potassium availability and soil exchangeable calcium, magnesium, and aluminum are mediated by lime in acidic soil. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2019, 19, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, C.A.; Brennan, R.F.; D’Antuono, M.F.; Sarre, G.A. The interaction between soil pH and phosphorus for wheat yield and the impact of lime-induced changes to soil aluminium and potassium. Soil research 2017, 55, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaopu, Z.; Genbao, Z. Effect of continuous liming on crop growth and their absorption of nutrients. Acta Pedologica Sinica (China) 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wacal, C.; Ogata, N.; Basalirwa, D.; Sasagawa, D.; Ishigaki, T.; Handa, T.; Kato, M.; Tenywa, M.M.; Masunaga, T.; Yamamoto, S. Imbalanced soil chemical properties and mineral nutrition in relation to growth and yield decline of sesame on different continuously cropped upland fields converted paddy. Agronomy 2019, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, V. Nutrient interactions in crop plants. Journal of plant nutrition 2001, 24, 1269–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Rafique, E.; Bughio, N.; Yasin, M. Micronutrient deficiencies in rainfed calcareous soils of Pakistan. IV. Zinc nutrition of sorghum. Communications in soil science and plant analysis 1997, 28, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Shahzad, K. Micronutrients status of apple orchards in Swat valley of North West Frontier Province of Pakistan. Soil Environ 2008, 27, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Luo, W.; Xu, G. Characterisation of magnesium nutrition and interaction of magnesium and potassium in rice. Annals of Applied Biology 2006, 149, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwal, R.; Kumar, V.; Singh, J. Potassium and magnesium relationship in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.). Plant and Soil 1985, 86, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlen, D.; Ellis Jr, R.; Whitney, D.; Grunes, D. Influence of Soil Moisture and Plant Cultivar on Cation Uptake by Wheat with Respect to Grass Tetany 1. Agronomy Journal 1978, 70, 918–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.; Grunes, D.; Sumner, M. Nutrient interactions in soil and plant nutrition. Handbook of soil science 2000, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya, T.; Yamagami, M.; Hirai, M.Y.; Fujiwara, T. Establishment of an in planta magnesium monitoring system using CAX3 promoter-luciferase in Arabidopsis. Journal of experimental botany 2012, 63, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewmaker, G.E.; Johnson, D.A.; Mayland, H.F. Mg and K effects on cation uptake and dry matter accumulation in tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Plant and soil 2008, 302, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maathuis, F.J. Physiological functions of mineral macronutrients. Current opinion in plant biology 2009, 12, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhat, N.; Elkhouni, A.; Zorrig, W.; Smaoui, A.; Abdelly, C.; Rabhi, M. Effects of magnesium deficiency on photosynthesis and carbohydrate partitioning. Acta physiologiae plantarum 2016, 38, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T.; Grunes, D. Potassium-magnesium interactions affecting nutrient uptake by wheat forage. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1985, 49, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Carter, J.; Parker, M.; Gaines, T. Interaction of soil zinc, calcium, and pH with zinc toxicity in peanuts. In Proceedings of Plant-Soil Interactions at Low pH: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Plant-Soil Interactions at Low pH, 24–29 June 1990, Beckley West Virginia, USA. pp. 339–347. [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.S.; Srinivas, K. Potassium dynamics and role of non-exchangeable potassium in crop nutrition. Indian J. Fertil 2017, 13, 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, F.; Lana, M.d.C. Contribution of non-exchangeable K in soils from Southern Brazil under potassium fertilization and successive cropping. Revista Ciência Agronômica 2018, 49, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) |

|---|---|---|

| Shaanxi | 35°21′~37°71′ | 109°40′~110°30′ |

| Shanxi | 34°52′~36°13′ | 111°09′~110°73′ |

| Henan | 34°41′~34°36′ | 110°94′~116°36′ |

| Gansu | 35°54′~34°56′ | 105°73′~115°95′ |

| Ningxia | 37°49′~38°65′ | 105°84′~116°14′ |

| Soil property | Mean | Deficiency Frequency (%) |

Low Frequency (%) |

Medium Frequency (%) |

High Frequency (%) |

Excess Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil pH | 8.56 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Exchangeable K (mg kg—1) | 269.36 | 27.7 | 27.4 | 8.5 | 7.4 | 29.1 |

| Exchangeable Ca (g kg—1) | 5.14 | - | - | 100 | - | - |

| Exchangeable Mg (g kg—1) | 0.20 | - | 19.3 | 38.9 | 15.7 | 26.1 |

| Available Cu (mg kg—1) | 1.11 | 3.3 | 9.9 | 45.4 | 33.5 | 7.9 |

| Available Mn (mg kg—1) | 4.46 | - | 63.8 | 36.2 | - | - |

| Available Zn (mg kg—1) | 0.94 | 34.4 | 20.1 | 31.3 | 9.1 | 5.1 |

| Available Fe (mg kg—1) | 5.94 | 5.4 | 32.2 | 52.0 | 8.8 | 1.6 |

| Soil property | Soil depth (cm) |

Province | Mean | Sample range | CV (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaanxi | Shanxi | Henan | Gansu | Ningxia | |||||

| Soil pH | 0-20 | 8.67 ± 0.31b | 8.28 ± 0.29c | 8.27 ± 0.33c | 8.64 ± 0.27b | 9.01 ± 0.29a | 8.55 | 7.14–9.33 | 3.57 |

| 20-40 | 8.67 ± 0.25b | 8.25 ± 0.29d | 8.50 ± 0.21c | 8.62 ± 0.27bc | 8.92 ± 0.35a | 8.57 | 7.27–9.31 | 3.04 | |

| Exchangeable K (mg kg—1) | 0-20 | 258.25 ± 126.22c | 404.12 ± 141.63a | 326.47 ± 173.92b | 304.40 ± 123.83bc | 147.74 ± 69.15d | 294.78 | 71.13–677.70 | 46.54 |

| 20-40 | 185.65 ± 134.04cd | 390.70 ± 171.00a | 292.87 ± 157.02b | 237.61 ± 101.60bc | 111.97 ± 51.12d | 243.93 | 48.29–697.80 | 56.34 | |

| Exchangeable Ca (g kg—1) | 0-20 | 5.75 ± 0.44a | 4.69 ± 0.39b | 4.23 ± 0.60c | 5.70 ± 0.29a | 4.50 ± 0.29bc | 5.15 | 3.12–6.41 | 8.64 |

| 20-40 | 5.66 ± 0.41a | 4.65 ± 0.26b | 4.29 ± 0.57c | 5.72 ± 0.32a | 4.54 ± 0.62bc | 5.12 | 3.24–6.65 | 8.35 | |

| Exchangeable Mg (g kg—1) | 0-20 | 0.16 ± 0.10c | 0.22 ± 0.08a | 0.24 ± 0.08a | 0.20 ± 0.15ab | 0.26 ± 0.07a | 0.20 | 0.08–0.55 | 42.53 |

| 20-40 | 0.16 ± 0.07b | 0.21 ± 0.07a | 0.23 ± 0.07a | 0.23± 0.11a | 0.26 ± 0.07a | 0.20 | 0.09–0.44 | 39.28 | |

| Available Cu (mg kg—1) | 0-20 | 0.87 ± 0.47bc | 1.11 ± 0.59b | 1.90 ± 1.46 a | 0.92 ± 0.34bc | 0.57 ± 0.24c | 1.07 | 0.20–6.54 | 67.96 |

| 20-40 | 1.12 ± 0.85b | 1.08 ± 0.52b | 1.65 ± 1.59a | 0.88 ± 0.21bc | 0.54 ± 0.37c | 1.14 | 0.15–8.37 | 63.23 | |

| Available Mn (mg kg—1) | 0-20 | 3.30 ± 1.40c | 5.04 ± 1.04b | 5.10 ± 1.31b | 6.14 ± 1.83a | 5.29 ± 1.36ab | 4.49 | 1.43–11.36 | 30.77 |

| 20-40 | 3.53 ± 1.27b | 5.24 ± 1.49a | 4.76 ± 1.28a | 5.20 ± 1.73a | 4.87 ± 1.24a | 4.43 | 1.63–9.49 | 31.34 | |

| Available Zn (mg kg—1) | 0-20 | 0.43 ± 0.40d | 1.22 ± 0.73b | 1.80 ± 0.89a | 0.71 ± 0.29cd | 1.07 ± 0.66bc | 0.89 | 0.11–3.30 | 66.12 |

| 20-40 | 0.76 ± 0.47b | 1.37 ± 0.57a | 1.44 ± 1.07a | 0.65 ± 0.44b | 1.04 ± 0.40ab | 0.99 | 0.13–3.67 | 62.90 | |

| Available Fe (mg kg—1) | 0-20 | 4.46 ± 1.37d | 7.20 ± 2.98b | 8.65 ± 3.36a | 6.06 ± 1.56bc | 4.63 ± 1.91cd | 5.99 | 2.08–16.58 | 37.86 |

| 20-40 | 5.07 ± 1.42 c | 6.43 ± 2.01b | 7.37 ± 1.99a | 5.51 ± 1.55bc | 5.50 ± 2.37bc | 5.88 | 2.29–12.98 | 29.82 | |

| Soil properties | Deficiency | Low | Medium | High | Excessive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exchangeable K (mg kg—1) | <150 | 150–250 | 250–300 | 300–350 | >350 |

| Exchangeable Ca (g kg—1) | <2 | 2–3 | 3–7 | 7–10 | >10 |

| Exchangeable Mg (g kg—1) | <0.06 | 0.06–0.12 | 0.12–0.18 | 0.18–0.24 | >0.24 |

| Available Cu (mg kg—1) | <0.30 | 0.30–0.50 | 0.50–1.00 | 1.00–2.00 | >2.00 |

| Available Mn (mg kg—1) | <1.00 | 1.00–5.00 | 5.00–5.00 | 15.00–30.00 | >30.00 |

| Available Zn (mg kg—1) | <0.50 | 0.50–0.80 | 0.80–1.80 | 1.80–2.50 | >2.50 |

| Available Fe (mg kg—1) | <3.00 | 3.00–5.00 | 5.00–9.00 | 9.00–13.00 | >13.00 |

| Leaf nutrient | Mean | Deficiency Frequency (%) |

Low Frequency (%) |

Medium Frequency (%) |

High Frequency (%) |

Excessive Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total K (g kg—1) | 19.76 | - | 11.0 | 46.3 | 10.3 | 32.4 |

| Total Ca (g kg—1) | 24.43 | - | 2.9 | 24.8 | 38.7 | 33.6 |

| Total Mg (g kg—1) | 3.64 | 9.5 | 13.9 | 23.4 | 28.5 | 24.8 |

| Total Cu (mg kg—1) | 24.90 | 10.3 | 68.0 | 10.3 | 5.2 | 6.2 |

| Total Mn (mg kg—1) | 119.37 | - | 2.4 | 8.7 | 16.7 | 72.2 |

| Total Zn (mg kg—1) | 23.35 | 20.7 | 40.0 | 29.6 | 8.9 | 0.7 |

| Total Fe (mg kg—1) | 87.46 | 66.2 | 18.5 | 12.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Leaf nutrients | Province | Mean | Sample rang | CV (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaanxi | Shanxi | Henan | Gansu | Ningxia | ||||

| Total K (g kg—1) | 18.70 ± 5.66b | 17.70 ± 3.03b | 21.55 ± 4.23a | 20.53 ± 6.32ab | 22.73 ± 6.15a | 19.76 | 8.51–33.69 | 26.83 |

| Total Ca (g kg—1) | 26.17 ± 7.66a | 22.33 ± 3.31b | 23.36 ± 3.91b | 21.74 ± 6.11b | 25.13 ± 3.83ab | 24.43 | 10.12–39.73 | 25.36 |

| Total Mg (g kg—1) | 3.39 ± 1.51c | 1.81 ± 0.34d | 4.25 ± 1.50b | 4.10 ± 1.03b | 5.28 ± 0.93a | 3.64 | 0.43–7.26 | 36.53 |

| Total Cu (mg kg—1) | 32.13 ± 40.03a | 17.32 ± 4.82a | 22.34 ± 12.86a | 16.01 ± 11.41a | 12.85 ± 3.08a | 24.9 | 7.56–145.82 | 119.12 |

| Total Mn (mg kg—1) | 130.01 ± 33.64a | 126.83 ± 14.79a | 121.78 ± 31.88a | 80.42 ± 19.08b | 88.08 ± 21.06b | 119.37 | 43.66–202.55 | 24.77 |

| Total Zn (mg kg—1) | 19.78 ± 6.27cd | 16.10 ± 5.23d | 32.56 ± 15.81a | 24.24 ± 10.74bc | 28.40 ± 20.86ab | 23.35 | 8.65–79.19 | 46.99 |

| Total Fe (mg kg—1) | 79.54 ± 31.13c | 103.68 ± 22.24b | 71.82 ± 25.15c | 99.22 ± 25.22b | 128.55 ±40.27a | 87.46 | 20.03–187.38 | 33.13 |

| Leaf nutrient | Deficiency | Low | Medium | High | Excessive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total K (g kg—1) | <8.0 | 8.0–14.0 | 14.0–20.00 | 20.0–22.0 | >22.0 |

| Total Ca (g kg—1) | <7.5 | 7.5–0.0 | 10.0–20.00 | 20.0–26.0 | >26.0 |

| Total Mg (g kg—1) | <1.5 | 1.5–2.2 | 2.2–3.5 | 3.5–4.8 | >4.8 |

| Total Cu (mg kg—1) | <10 | 11–19 | 19–50 | 50–100 | >100 |

| Total Mn (mg kg—1) | <40 | 40–50 | 50–80 | 80–00 | >100 |

| Total Zn (mg kg—1) | <15 | 15–23 | 23–45 | 45–75 | >75 |

| Total Fe (mg kg—1) | <100 | 100–119 | 119–150 | 150–180 | >180 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).