1. Introduction

CrAssphages were the first phages that were officially recognized by the International Committee for Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV,

https://ictv.global/taxonomy) despite the fact that they had not been isolated as individual entities [

1,

2]. CrAssphages have been discovered when analyzing NGS sequencing data using cross-assembly software [

3]. Previously, phages of uncultivated prokaryotes were not systematized and incorporated into the modern taxonomic system. The discovery and recognition of the CrAssphages ensured the search and study of new phages among the metagenome assembled genomes (MAGs). Despite the fact that some phages that were found in the metagenomes were subsequently cultivated and isolated, most of them have been studied only in terms of the organization of their genomes [

4,

5,

6].

СrAss-like phages are double-stranded DNA viruses that infect bacteria from the phylum Bacteroidetes [

1]. Previously, all CrAssphages were assigned to the order Crassvirales and divided into four groups (families): Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta [

2]. ICTV recently approved new family names for crAss-like phages: the

Intestiviridae,

Steigviridae,

Crevaviridae, and

Suoliviridae families (corresponding to the former Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta groups, respectively). These four families currently include ten subfamilies, 42 genera, and 73 species [

6].

The first crAss-like phage that has been isolated from the culture of

Bacteroides intestinalis was p-crAssphage or ΦCrAss001 (now

Kehishuvirus primaries from the

Steigviridae family, former beta crAss-like phage group) [

4]. Later, another 30 crAssphages were identified, cultivated, and studied that allowed them to be attributed to 11 different species of the

Steigviridae family. Most of them infect

Bacteroides intestinalis; three species infect

Bacteroides cellulosilyticus and one is specific to

Bacteroides tethaiotaomicron [

7,

8]. In 2021, the ΦCrAss002 phage belonging to the

Jahgtovirus secundus species, the

Intestiviridae family (former alpha group of сrAss-like phages) was isolated from

Bacteroides xylanisolvens [

5]. No сrAss-like phages of other families were isolated from the bacterial culture. Many cultured crAss-like phages require long-term cultivation, while even at high titers they do not lyse planktonic cultures and do not form plaques on a lawn of sensitive cells, or plaques are poorly visible [

5,

6]. It is assumed that members of the

Crevaviridae family were observed by electron microscopy of fecal filtrate containing significant amounts of crAss-like phages [

2].

The study of crAssphages has shown their important place in the intestinal microbiota and revealed their wide prevalence and great diversity [

6,

9,

10,

11]. It has been shown that certain groups of crAss-like phages dominate in industrialized countries, while other crAss-like phages are more common among the rural population of developing countries. The prevalence of crAss-like phages in the urban population is substantially higher than in the rural population [

8,

12,

13]. This fact can be partly explained by the association of

Bacteroides with the diet of the urban population [

14]. Due to the high prevalence of crAssphages in the human intestine, their monitoring in the environment has been currently proposed to control the level of contamination with human faeces [

15,

16,

17].

Recently, two new groups of Crass-like phages have been identified among the intestinal circularized MAGs [

18]. These groups that were named Zeta and Epsilon showed sabstantial genetic distance from other crAss-like phages assigned to four approved families. CrAss-like phages of the Epsilon group do not encode DNA polymerases, unlike other members of the Crassvirales order, which mainly encode the B family DNA polymerase and sometimes A family DNA polymerase (some species of the

Steigviridae family and zeta crAssphages) [

18]. It has been proposed to separate CrAss-like phages of Zeta and Epsilon groups into new families [

6,

18]; however, ICTV currently does not assign them to any families.

In this study, a new epsilon crAss-like phage was found in the human intestinal metagenome. It was shown that this phage encode several atypical proteins (DNA primase, virion RNA polymerase, reverse transcriptase, and receptor binding protein) that substantially differ from those found in other crAss-like phages. The presence of the conservative prophage repressor and anti–repressors that belong to the lysogenic-to-lytic cycle switches indicated that the studied phage and several other epsilon crAss-like phages could be temperate.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of the Phage Genome

Virome shotgun library was constructed from a stool sample from a healthy voluneer (Project: PRJNA1025976; BioSample: SAMN37731570; SRA: SRR26322353). After sequencing and de novo assembly, a 151,256 bp gapless contig was identified using the SPAdes genome assembler. An average coverage was 126 and it was a pseudo-circular MAG that suggested that this is the complete genome of the unknown Caudoviricetes phage. “Cut open” of this MAG was carried out using PhageTerm analysis and the starting point of the genome was predicted with a probability value 1.5 × 10-22. The name crAssE-Sib was proposed for this phage. The complete genome sequence of crAssE-Sib phage was submitted into the GenBank database with the accession number OR575929.

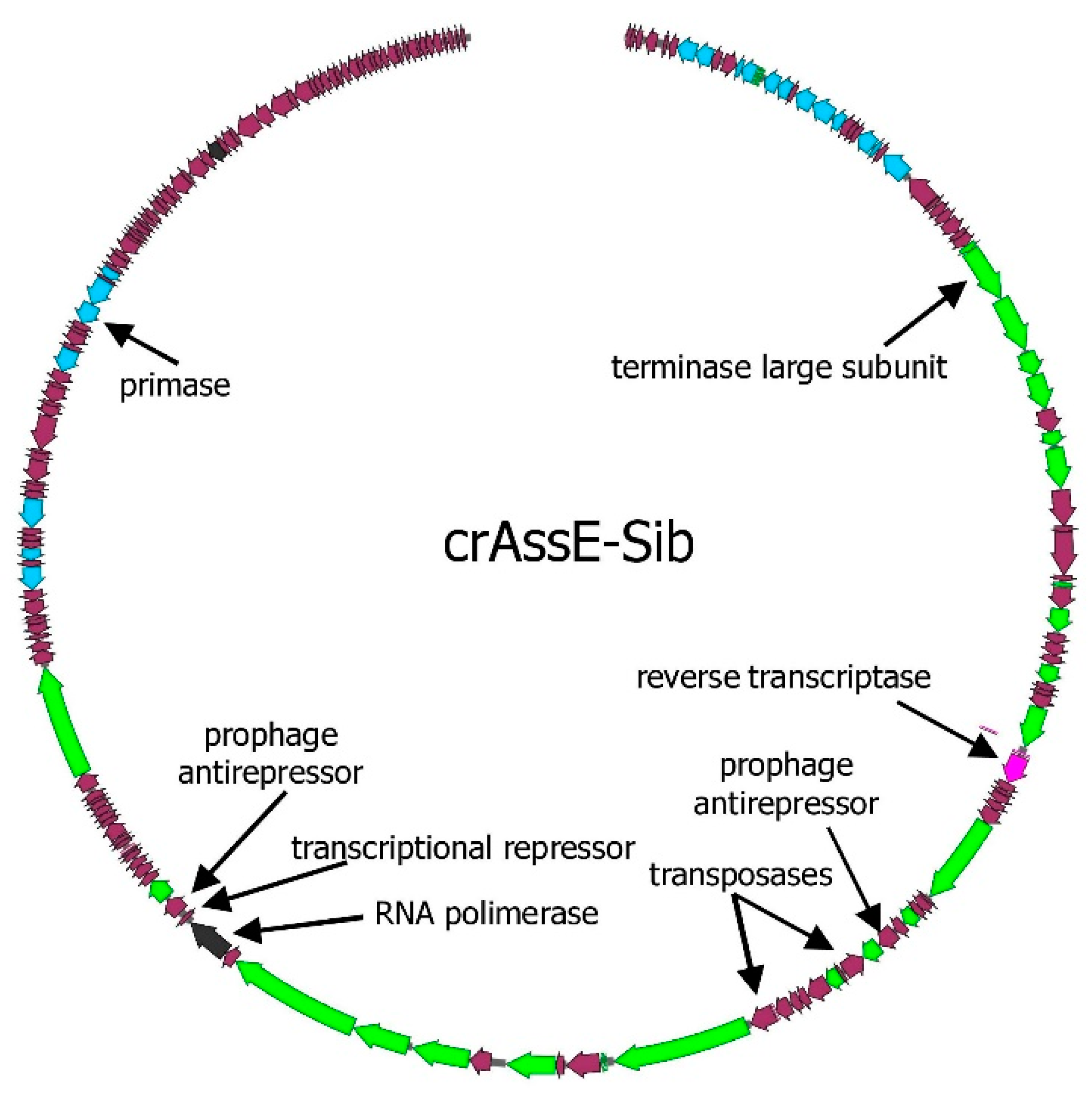

Genome of crAssE-Sib phage encodes 202 putative ORFs, six of them encode tRNAs (

Figure 1). Of the 196 ORFs, 76 encode proteins with predicted functions, which were determined based on the similarity of their amino acid sequences and domain structure with the described proteins. The remaining 122 ORFs were defined as hypothetical.

2.2. Comparative Analysis of the CrAssE-Sib Phage Genome

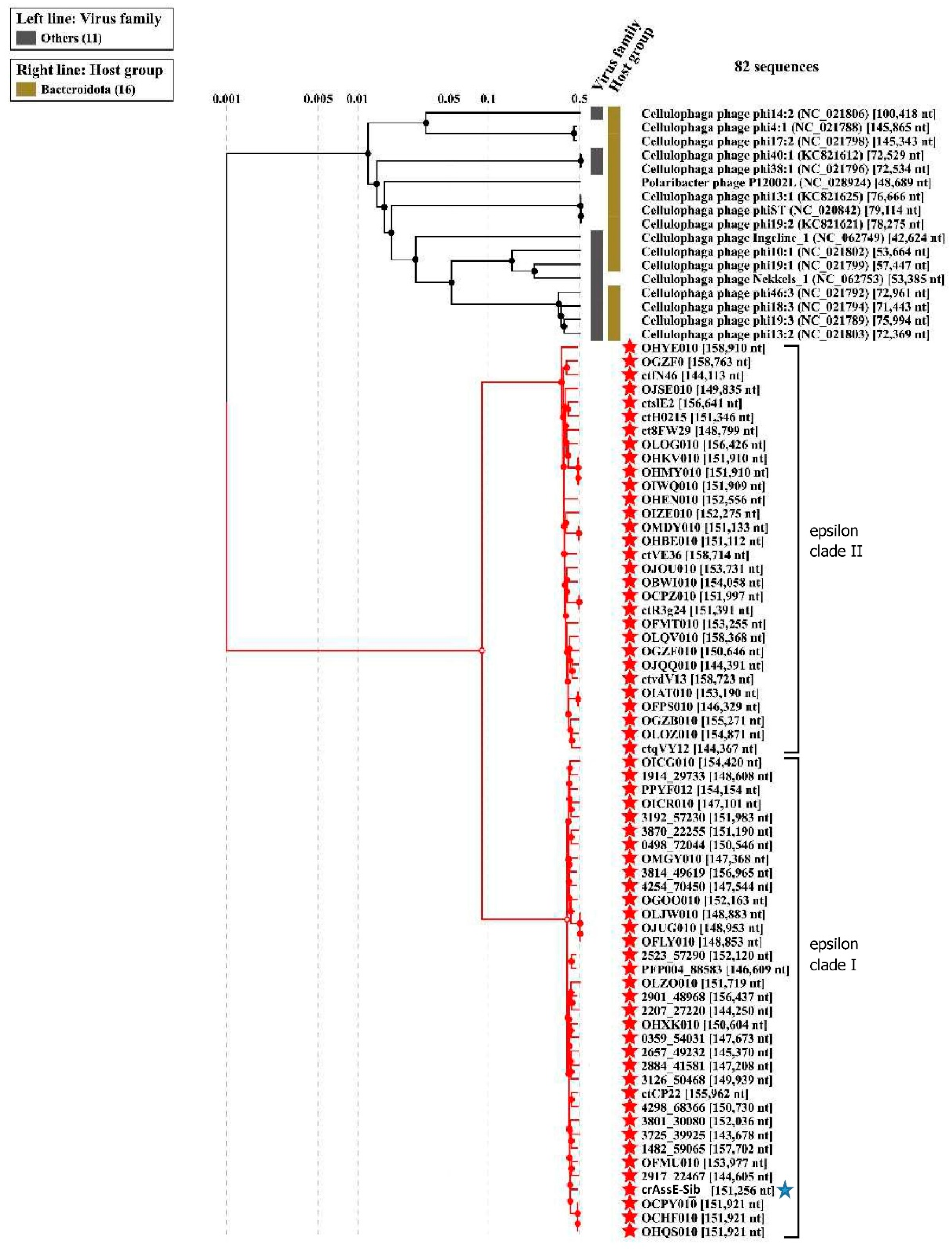

Comparison of the crAssE-Sib genome using BLASTn revealed the highest sequence identity with members of a new group of epsilon crAss-like phages. From this group, sequences with a length of more than 140,000 bp were taken for further analysis. Previously, sequences of epsilon crAss-like phages of this length have been characterized as pseudo-circular MAGs, indicating that these were complete phage genomes [

18]. The analysis of the proteomic tree calculated using ViPTree (

Figure 2) confirmed that the crAssE-Sib phage belongs to the epsilon crAss-like group of phages. In addition, comparative ViPTree analysis indicated that epsilon crAss-like phages formed two clades: clade I and clade II (

Figure 2). Clade I contains 35 sequences, including crAssE-Sib; clade II combines 30 sequences (

Figure 2). All epsilon crAss-like phages have similar genome lengths ranging from ~144 to 159 kb. Close to epsilon crAss-like phages there were phages infecting Bacteroidota: sixteen Cellulophaga phages and one Polaribacter phage. The lengths of their genomes are smaller than those of epsilon crAss-like phages and vary from 42 kb to 149 kb; however, most of genomes are 70–80 kb. Significant differences of epsilon crAss-like phages proteomes from their close relatives and other crAss-like phages allowed us to distinguish them into a separate family.

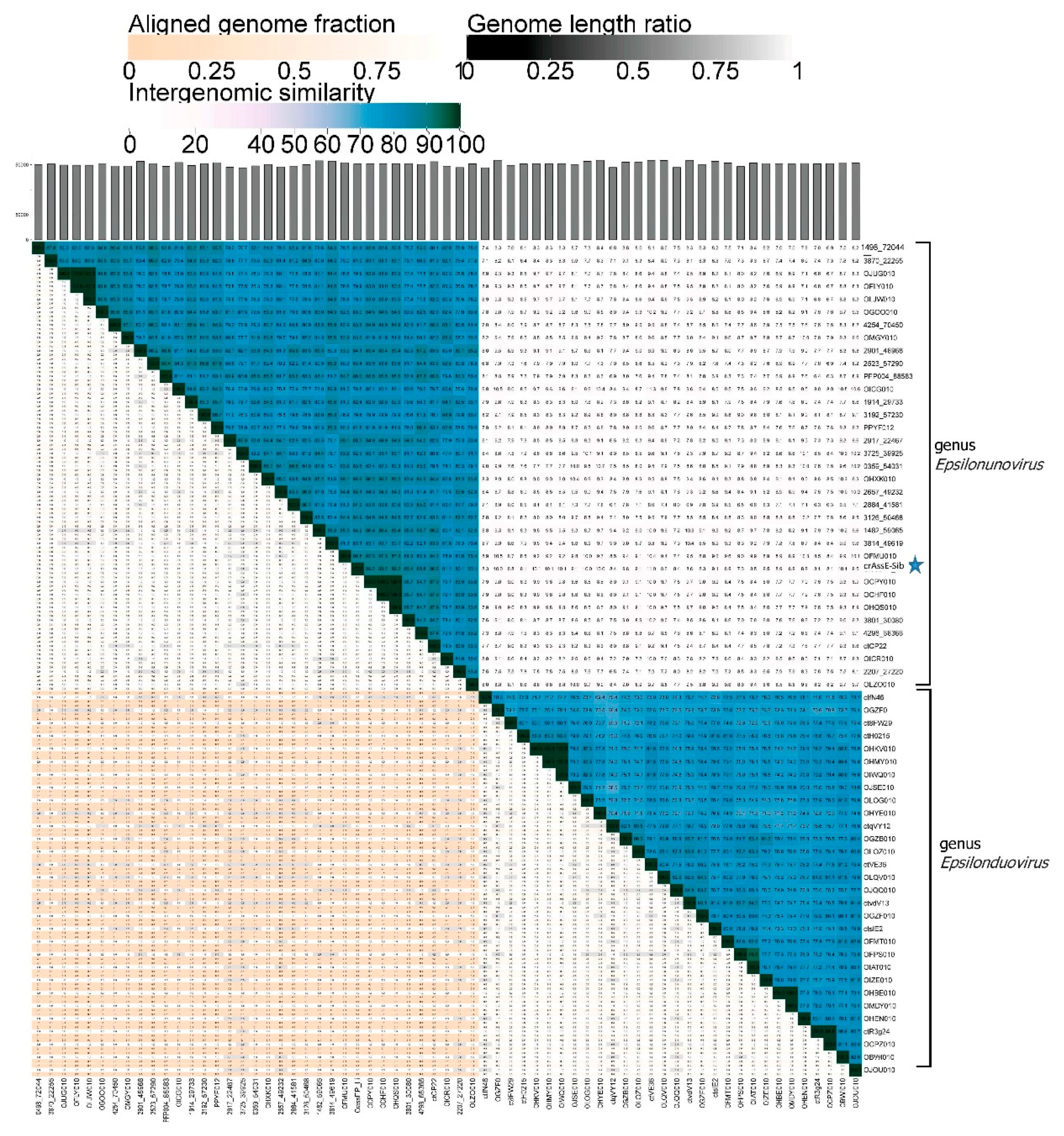

To clarify the taxonomy of epsilon сrAss-like phages, a matrix of intergenomic similarities was constructed using the Virus Intergenomic Distance Calculator (VIRIDIC) (

Figure 3). A comparative genome analysis was performed on the base of intergenomic similarity, aligned genome fraction, and genome length ratio. The obtained results confirmed the division of epsilon crAss-like phages into two subgroups, which represent two proposed genera Epsilonunovirus and Epsilonduovirus in the group of epsilon crAss-like phages. It can be concluded that there are at least 31 different species in genus Epsilonunovirus, including crAssE-Sib, and 25 species in genus Epsilonduovirus. In some cases, individual species are represented by 2–3 sequences (

Figure 3).

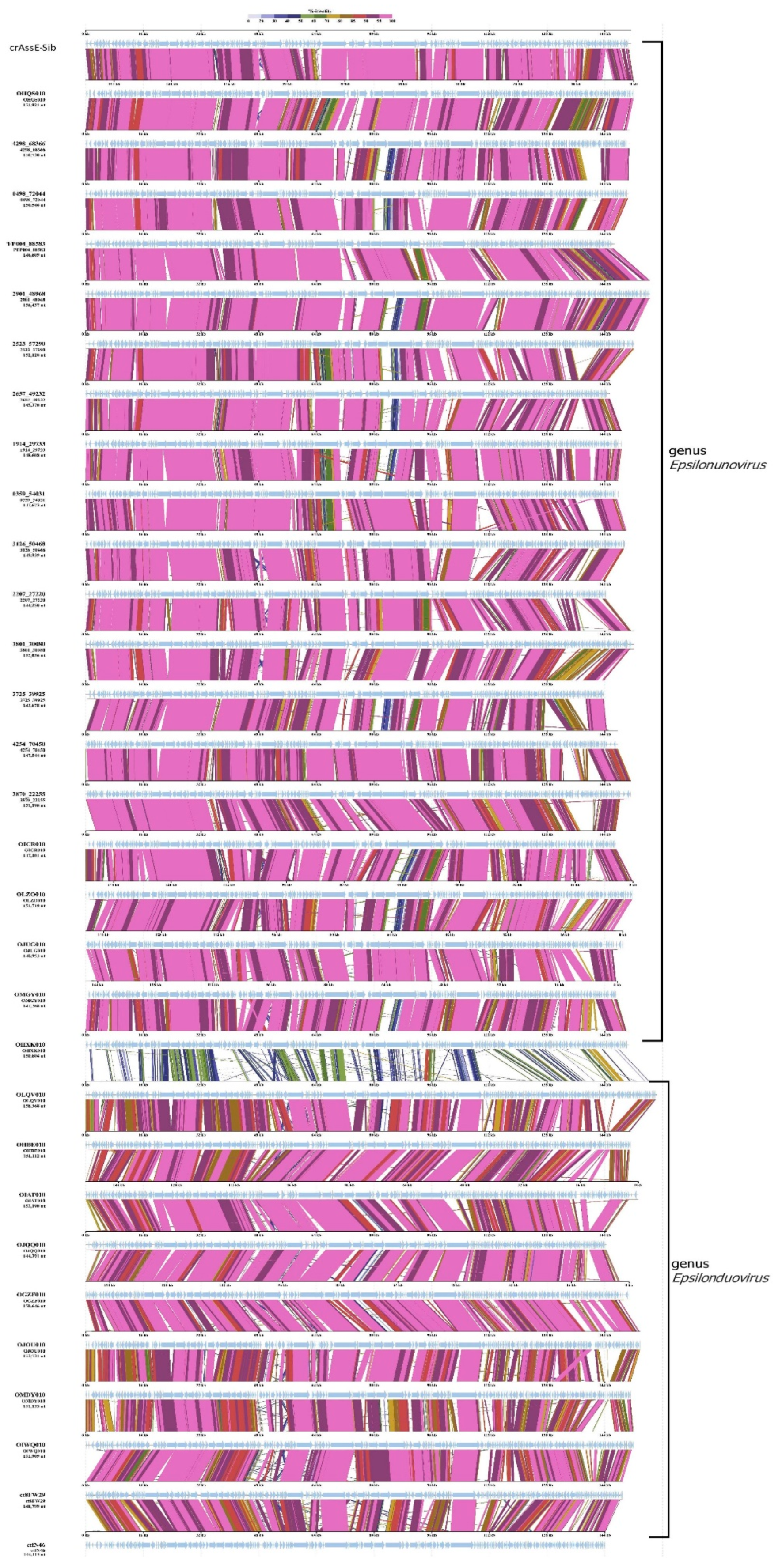

Comparative genome alignment of the epsilon crAss-like phages obtained using the ViPTree tool indicated high level of gene synteny both within the proposed genera and between them (

Figure 4). Sequences with minimal nucleotide similarity (from 0.582 to 0.700) were taken for the analysis. There were 20 and 10 sequences of the Epsilonunovirus (includes crAssE-Sib) and Epsilonduovirus genera, respectively (

Figure 4). At the beginning of the genomes, there is a region that is highly homologous between the related genomes. This region demonstrates the most similarity of sequences between the genera Epsilonunovirus and Epsilonduovirus. This region includes the genes encoding the terminase subunits and genes of structural proteins, namely portal, major capsid, and ring proteins. In addition, a significant homology was found in some other proteins of phages from both the Epsilonduovirus and Epsilonduovirus genera (carbohydrate-binding protein, muscle protein, and some proteins of the replicative apparatus).

2.3. Analysis of the crAssE-Sib Proteins

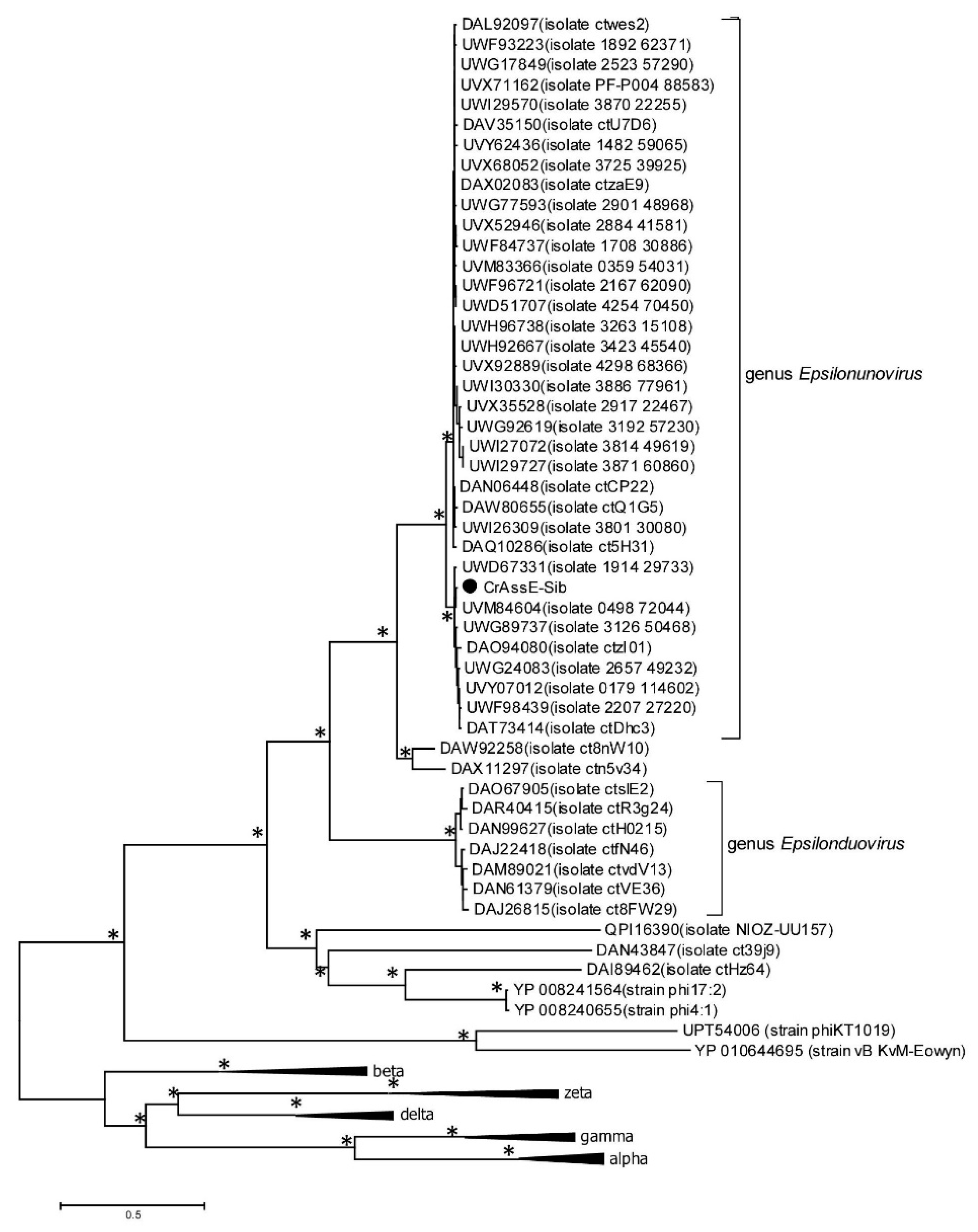

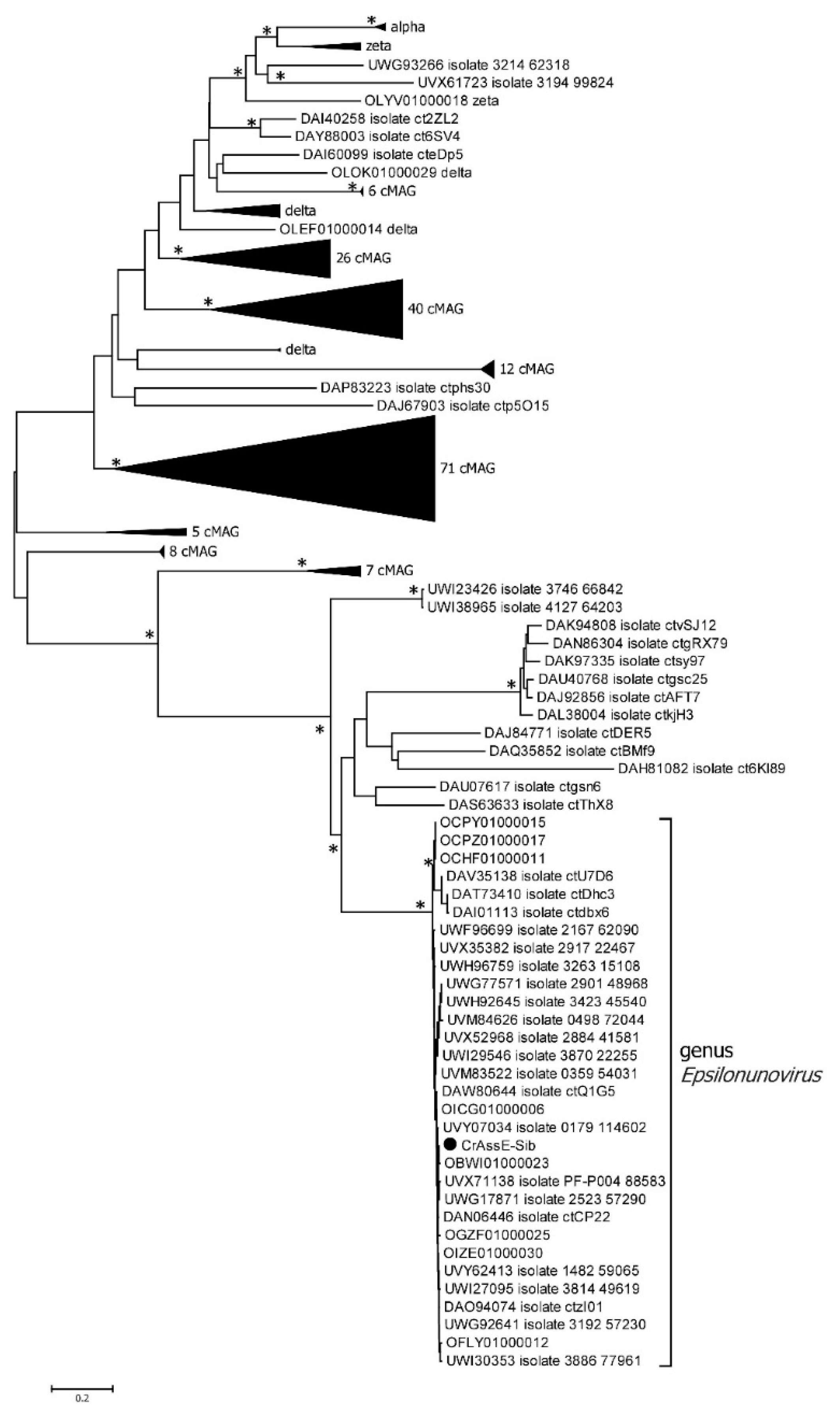

In order to verify the taxonomy of the crAssE-Sib phage and relative phages, phylogeny of the large subunit of terminase and DNA primase along with their most similar orthologs was analyzed. On the maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of the terminase large subunit (

Figure 5), sequences of epsilon crAss-like phages are divided into two clades according to the Epsilonunovirus and Epsilonduovirus genera, as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. In addition, they form an outer group to the rest of the crAss-like phages. This fact confirms that epsilon crAss-like phages should be isolated into a separate family. Notably, there are two additional sequences that are closely related but are not members of the proposed genera Epsilonunovirus and Epsilonduovirus. However, these sequences of the terminase large subunit are derived from short (less than 30 kb) nucleotide sequences, and taxonomic analysis of these phages is impossible.

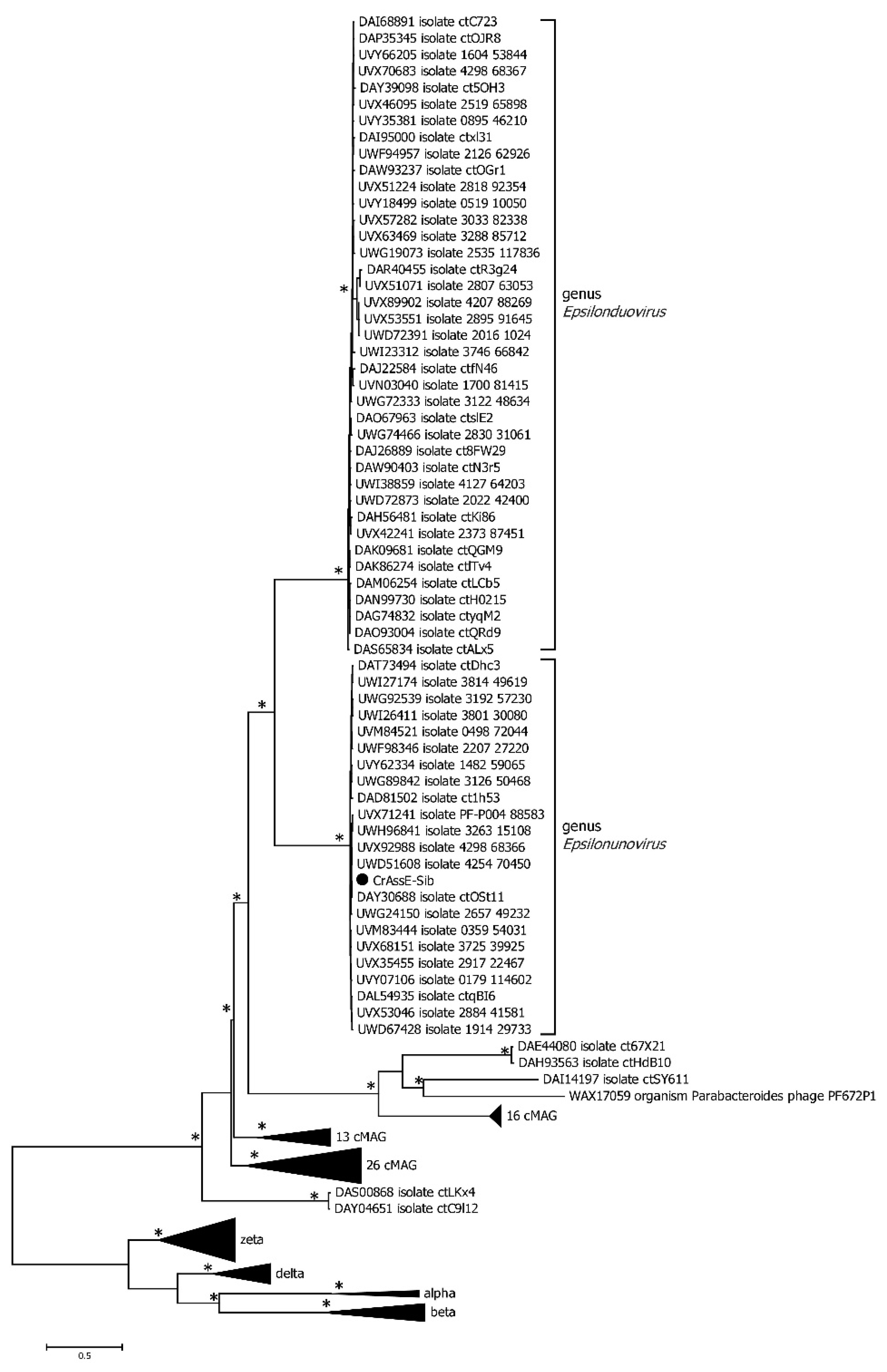

Phylogenetic analysis of the phage primase showed that, as in the case of the large terminase subunit, two clades corresponding to the genera Epsilonunovirus and Epsilonduovirus can be distinguished (

Figure 6). The primase sequences of epsilon crAss-like phages are significantly differ from those of other crAss-like phages indicating that epsilon crAss-like phages belong to a separate family.

In addition to the genes encoding the terminaze large subunits and DNA primase, several other genes that substantially differed from those in other crAss-like genomes were found in crAssE-Sib. Thus, the gene encoding the RNA polymerase that distinguished from those in crAss-like phages was revealed in crAssE-Sib (

Figure 1, Data S1). HHPRED analysis showed that the crAssE-Sib virion RNA polymerase is similar to that of the phage phi14:2 with 95% probability [

19]. This phage with a heterogeneous group of other phages formed a neighboring cluster on the ViPTree dendrogram (

Figure 2). The crAssE-Sib virion RNA polymerase was conservative for epsilon crAss-like phages, and according to phylogenetic analysis, this polymerase significantly differed from the RNA polymerases of other crAss-like phages (

Figure 7).

In addition, two transposases genes were found in the genome of the crAssE-Sib phage (

Figure 1, Data S1). These two-directional genes encode proteins with an aa identity level of 18.2% between themselves and both transposases are members of the RNA-guided endonuclease TnpB protein family. The probable function of TnpB is to maintain a transposon in the genome. Notably, these genes are absent from the genomes of most epsilon сrAss-like phages.

Moreover, the crAssE-Sib phage genome encodes the NinG protein, transcriptional repressor, and two prophage antirepressors that both are the podoviridae phage lytic switch antirepressors (

Figure 1, Data S1). These genes were found only in members of the Epsilonunovirus genus. The presence of such proteins indicates a temperate lifestyle of the phage.

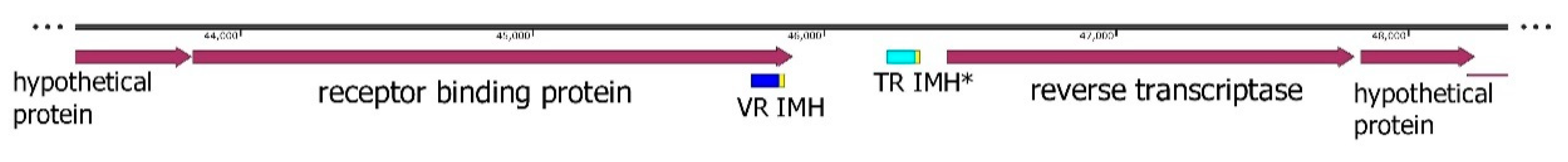

2.4. Analysis of the Diversity-Generating Retroelement (DGR)

DGR cassettes are widely presented in the genomes of various Crass-like phages; some of them contain complete DGR cassettes, whereas only DGR fragments or nothing are found in other phages. In the crAssE-Sib phage genome, the reverse transcriptase (RT) gene was found using HPRED analysis. In addition, sequences located next to the RT gene were identified as the target gene (receptor binding protein, RBP), variable repeat (VR) located at the 3′-end of the target gene, template repeat (TR), initiation of the mutagenic homing (IMH) sequence that was found at the 3′-end of the VR, and IMH* sequence that was detectedat the 3′-end of the TR (

Figure 8). All these sequences are essential elements of the complete DGR-cassette [

20,

21,

22].

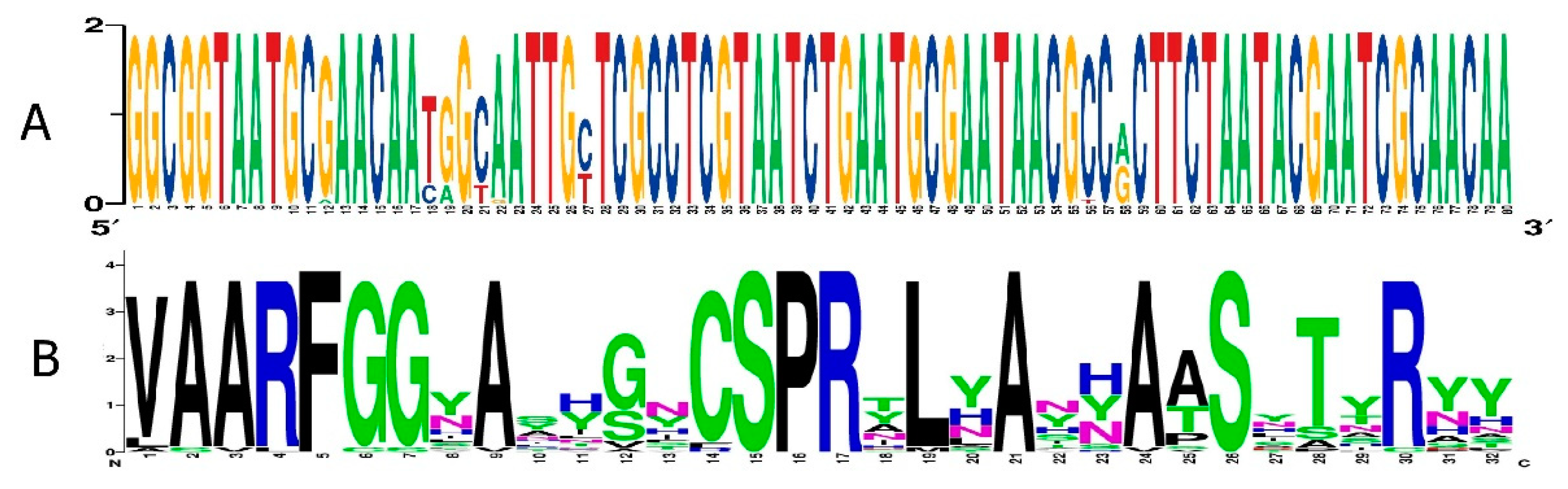

Screening of the available genomes of epsilon crAss-like phages showed that DGR cassettes were found only in a large group of phages from the Epsilonunovirus genus UNO, whereas DGRs were absent in members of Epsilonduovirus genus (

Figure 4 and S1). Notably, all genomes of phages from the genus Epsilonunovirus encoded conservative RBPs. All VRs in these RBPs showed a certain amino acid (aa) pattern despite the variability in their aa sequences (

Figure 9). Unlike the gene encoding RBP, the RT gene in some phages was fragmented or deleted indicating that retrohoming is not used by some members of the Epsilonunovirus genus. In addition, TRs were conservative in those DGR cassettes that were complete (

Figure 9).

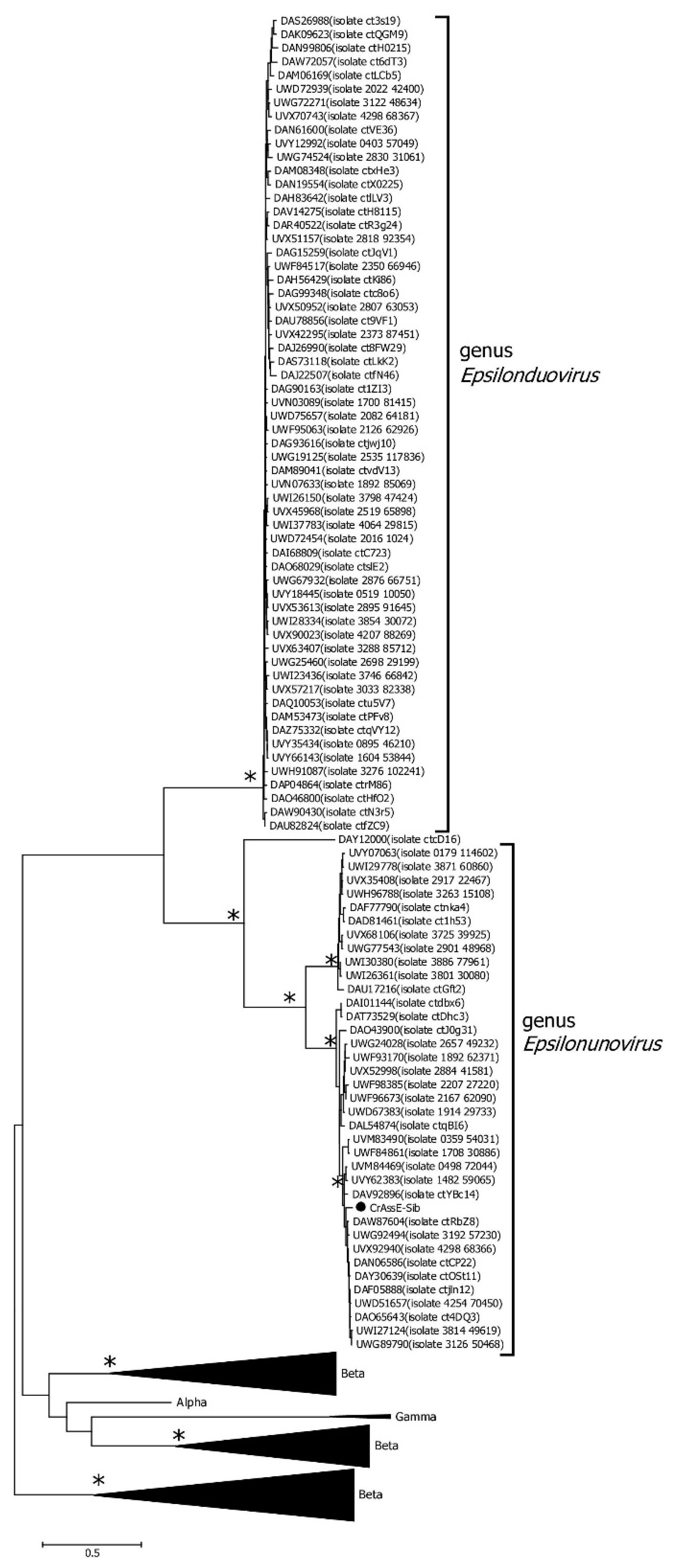

Analysis of the RT phylogeny of the crAss-like phages indicated that sequences from the Epsilonunovirus genus formed a monophyletic group that substantially differed from those from the Intestiviridae (alpha) and Suoliviridae (delta) genera as well as zeta crAss-like phages (

Figure 10).

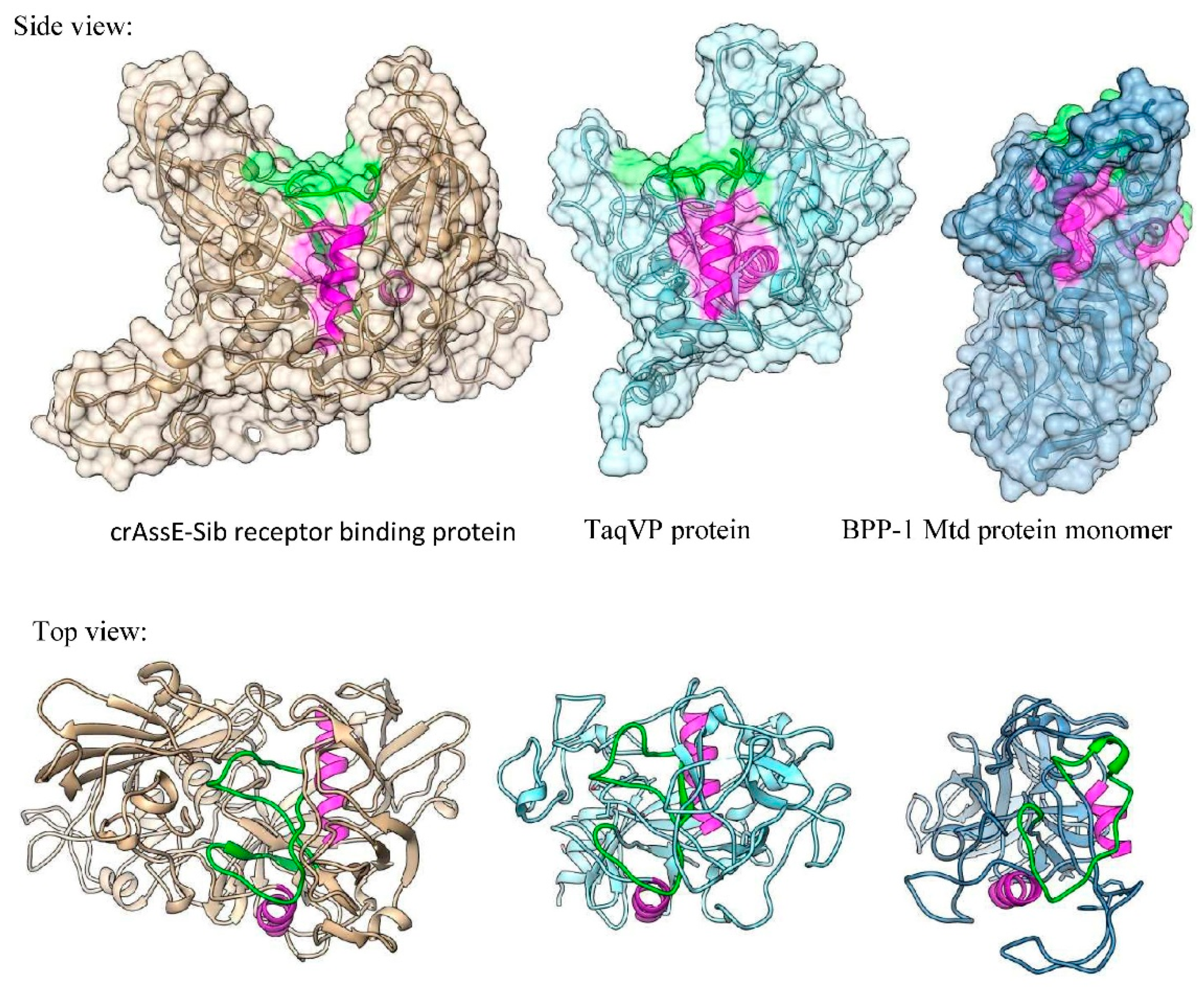

Three-dimensional (3D) modeling of RBP that was encoded by the crAssE-Sib phage was performed using Alphafold2 (

Figure 11). Comparison of the obtained model using DALI server with structures of similar proteins showed that RBP has a structural similarity with proteins containing the C-type lectin domain (

Figure 11 and Figure S2). The highest similarity of the crAssE-Sib RBP was revealed with the TaqVP protein (pdf 5 VF4, DALI Z-score 19.7) that is encoded by the gene located in the DGR cassette found in Thermus aquaticus (

Figure 11 and S2) [

23]. However, RBP of crAssE-Sib contained an additional N-terminal part that was absent in TaqVP and probably played a role in the protein attachment to the virion. RBP of crAssE-Sib also showed high similarity to the variable protein 1 from Treponema denticola (pdb 2Y3C, DALI Z-score 11.7), which is also hypermutated by DGR [

24]. In addition, structural similarities were found with some enzymes, including the human formylglycine-generating enzyme (pdb 6MUJ, DALI Z-score 10.2). On the contrary, the structure of crAssE-Sib RBP differed from that of the target Mtd protein found in the DGR cassette of the BPP-1 phage (

Figure 11). In the Mtd protein, the VR region is located on its surface, whereas it is hidden in a cavity in RBP of the crAssE-Sib phage.

3. Discussion

In this study, the complete genome encoding a new phage crAssE-Sib belonging to a group of epsilon crAss-like phages was found in the human virome. A detailed comparative analysis of the crAssE-Sib genome and genomes of available epsilon crAss-like phages indicated that all epsilon crAss-like sequences can be divided into two proposed genera Epsilonunovirus and Epsilonduovirus. This result is confirmed both by analysis of phages proteomes and phylogeny of phage proteins, including signature ones. In addition, the crAssE-Sib genome contained several genes that significantly differed from their orthologs found in members of the Intestiviridae, Steigviridae, Crevaviridae, and Suoliviridae families and zeta-group of crAss-like phages.

Thus, it has been previously suggested that DNA primase is the only protein that is conservative for all crAss-like phages, with the exception of epsilon ones [

6]. It has been shown that the DNA primases of crAss-like phages form a monophyletic clade and probably descended from one crAss-like phage ancestor [

1,

6,

18]. In this study, the primase genes were found in genomes of epsilon crAss-like phages; however, the primase of epsilon phages varied and were not part of the monophyletic clade with the primases of other crAss-like phages (

Figure 6). We also found the gene encoding RNA polymerase in the crAssE-Sib genome (

Figure 7). This finding became possible when the structure of the virion RNA polymerase of the phage phi14:2 had been available [

19], since this enzyme has certain similarity with that of crAssE-Sib.

It was shown that the crAssE-Sib genome contains DGR cassette with all essential elements, namely the RT gene, target gene encoding RBP, VR, TR, IMH, and IMH*, and RBP undergoes mutagenic retrohoming in this phage (

Figure 9). Despite the fact that the RT gene was detected with high confidence in the crAssE-Sib phage genome, the myDGR program [

25] did not find the presence of DGR in crAssE-Sib and other epsilon crAss-like phages genomes. It can be explain by the fact that crAssE-Sib RT contains the GxxxSP motif in its fourth domain, instead of the characteristic GxxxSQ motif found in DGRs. Usually, the GxxxSP motif is detected in most retroviral and retrotransposon RTs and group II intron maturases [

26] and finding this motif in RT from the DGR cassette was unexpected. When we changed this motif in RT of crAssE-Sib, myDGR perfectly detected the RT gene and hence DGR. It should be noted that myDGR is widely used to search and study DGRs. The presence of RT with unusual aa motifs in DGRs would prevent the detection and study of these DGRs. So, prevalence and diversity of DGRs in viral and prokaryotic genomes are insufficiently studied.

As for RBD of crAssE-Sib that is a target protein in DGR, no similar phage proteins were found in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). However, despite low sequence similarity, this RBD showed structural similarity with C-lec fold-containing proteins that are the predominant type of target proteins in DGR cassettes [

23]. The highest structure similarity was found between crAssE-Sib RBD and the target protein from DGR of

Thermus aquaticus (

Figure 11 and Figure S2).

Surprisingly, the genes encoding prophage repressors and anti–repressors absent in crAss-like phages were found in the epsilon crAss-like genomes. It has been previously shown that antirepression system is associated with the switching of the life cycle in the temperate podoviridae phages [

27,

28]. There are two prophage anti-repressor genes and one transcription repressor gene in the crAssE-Sib phage genome (

Figure 1). The alignment of these two prophage antirepressor sequences indicated their significant identity, which suggests that these antirepressors are probably paralogs (Figure S3). Analysis of other crAss-like phage genomes showed that these genes are unique to the

Epsilonunovirus genus. Within this genus, one prophage antirepressor gene and one transcriptional repressor gene are conservative.

Attempts were made to detect prophage sequences related to epsilon crAss-like phages in the bacterial genomes. We found two incomplete prophage sequences in chromosomes of Parabacteroides distasonis BFG-238 and Parabacteroides merdae CL06T03C08. Comparative analysis of their proteomes with crAssE-Sib (genus Epsilonunovirus) and OLQV010 (genus Epsilonduovirus) suggested that these prophage sequences belong to unknown genera of temperate Parabacteroides phages. This supposed genus could be the third one in the epsilon crAss-like phages family. Notably, the prophage sequence from the Parabacteroides distasonis BFG-238 strain demonstrates close levels of similarity with the Epsilonunovirus and Epsilonduovirus genera, like these genera among themselves (Figure S4).

Based on sequence similarity of CRISPR spacers in microbial genomes and sequences of crAss-like phage genomes, it has been previously supposed that epsilon crAss-like phages infect bacteria from the

Bacteroides,

Parabacteroides, and

Porphyromonas genera (class Bacteroidia) [

9,

18]. So, we can assume that the crAssE-Sib phage also infects bacteria from one of these genera.

Our search for the integrase gene in the epsilon crAss-like phages genomes using FASTER and IntegronFinder 2.0 failed. A number of genes involved in recombination processes have been discovered, and the gene encoding the NinG protein is one of them [

29]. However, it is impossible to say whether the epsilon crAss-like phage genomes can be inserted into the host genome. It has been known that some temperate phages may not integrate their genomes into the host genome, but save them in the cell as episomes or linear genomes, and that the genes of such phage genomes are expressed along with bacterial genes [

30,

31,

32]. Possibly, the lysogeny of epsilon crAss-like phages occurs by this mechanism. When crAss-like phages from the I

ntestiviridae,

Steigviridae,

Crevaviridae, and

Suoliviridae families were studied, it was suggested that these crAss-like phages are lytic and incapable of lysogeny. However, these phages could be pseudolysogenic since they are capable of long-term persistence in the host culture, and the probable mechanisms of pseudolysogeny can be

the carrier state or chronic infection hibernation inside infected cells [

4,

6,

33,

34]. As for members of the genus

Epsilonunovirus, we probably found the true temperate crAss-like phages. Finding of prophages that are relative to this genus can confirm this assumption.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phage Genome Sequencing

Isolation of viral DNA from a fecal sample was described in detail previously [

35]. Briefly, the sample was clarified by repeated centrifugation and treated with DNase I, 5 U (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and Proteinase K 100 μg/ml (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Then, phenol-chloroform extraction and subsequent ethanol precipitation were used to purofy DNA. The resulting DNA was diluted in 50 µl of TE buffer and DNA concentration was measureed using Qubit 4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). Virome shotgun library was constructed using the NEB Next Ultra DNA library prep kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA). For sequencing, a MiSeq Benchtop Sequencer (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and a MiSeq Reagent Kit 2 × 250 v.2 (Illumina Inc., CA, USA) were used. After de novo assembly of the genome using the SPAdes software V.3.15.2 [

36], the resultant single contig was further analyzed.

This work was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Center for Personalized Medicine, Novosibirsk (protocol #2, 12 Febriary 2019). The written consent of healthy volunteer was obtained in accordance to guidelines of the Helsinki Ethics Committee.

4.2. Phage Genome Analysis

With the help of PhageTerm [

37] (

https://galaxy.pasteur.fr, access date 25 August 2023), the termini of the genome that was obtained in a “pseudo-circular” form were determined. Online RAST server v. 2.0 [

38] was used for the identification of ORFs and possible tRNA genes within the genome. The prediction of the tRNA genes was additionally performed by tRNAscan-SE V 2.0 [

39]. Genome function annotation was done by InterProScan (

www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/), HHPpred (toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/tools/hhpred), HHblits (toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/tools/hhblits) and BLASTP (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA). Predictions on the architecture of the domain and functional motives were made using CD-BLAST (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.3. Comparative Phage Analysis

Identification of nucleotide sequences similar to the crAssE-Sib phage genome was performed using BLASTN. Comparative analysis of crAssE-Sib phage proteome was performed by ViPTree version 3.7 web server (

https://www.genome.jp/viptree, accessed on 3 August 23) with default parameters [

40]. ViPTree analysis based on genome-wide sequence similarities computed by tBLASTx. The intergenomic similarity was determined using the VIRIDIC tool (

http://rhea.icbm.uni-oldenburg.de/VIRIDIC) [

41]. The genera were predicted using thresholds of the intergenomic identity 70% [

42,

43].

4.4. Analysis of Proteins

Amino acid sequences with significant similarity to the studied ones were downloaded from GenBank using crAssE-Sib phage proteins as query in BLAST search against NCBI’s protein database. Protein sequences were aligned using the M-Coffee method in the T-Coffee program [

44]. The levels of amino acid identity of proteins were calculated by the BioEdit 7.2.5 program [

45]. Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic trees were generated by the IQ-tree program v. 2.0.5 [

46]; the best fit substitution model according to ModelFinder [

47] was used. Branch supports were assessed using 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates [

48]. The resulting trees were midpoint rooted and visualized in FigTree v1.4.1. Analysis of the genes included in DGR was carried out by the myDGR program [

25]. The search for phage integrase genes was performed using programs IntegronFinder 2.0 [

49] and FASTER [

50]. Sequence logos representations of amino acid and nucleic acid multiple sequence alignment were calculated by WebLogo version 2.8.2 [

51].

4.5. 3D Modeling of Protein Structures

Ribbon and surface representations of proteins were predicted in the AlphaFold2 program available at

https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb [

52]. The resulting structural models were downloaded and edited using UCSF Chimera molecular visualizer, version 1.17 [

53]. 3D-model of the RBP part (aa residues 85−678), which was encoded by the crAssE-Sib phage genome, was modeled using Alphafold2 with a high degree of confidence. The analysis of the models was performed using DALI server [

54]

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.V.B. and N.V.T.; formal analysis, I.V.B., A.Y.T., I.K.B, and N.V.T.; investigation, I.V.B., A.Y.T., and I.K.B.; data curation, I.V.B., A.Y.T., I.K.B, and N.V.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.V.B. and N.V.T; writing—review and editing, I.V.B. and N.V.T.; supervision, N.V.T.; project administration, N.V.T; funding acquisition, N.V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, Project No. 21-14-00360. 3D modeling were supported by the Ministry of Education and Science, Project No. 121031300043-8.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of theDeclaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Center for personalized medicine, Novosibirsk (protocol #2, date of approval 12 January 2019) including the written consents of healthy volunteers to present their fecal samples for scientific purposes (according to guidelines of the Helsinki ethics committee).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all healthy volunteers involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and the order of authors, and there is no financial interest to report. All co-authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Yutin, N.; Makarova, K.S.; Gussow, A.B.; Krupovic, M.; Segall, A.; Edwards, R.A.; Koonin, E.V. Discovery of an expansive bacteriophage family that includes the most abundant viruses from the human gut. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerin, E.; Shkoporov, A.; Stockdale, S.R.; Clooney, A.G.; Ryan, F.J.; Sutton, T.D.S.; Draper, L.A.; Gonzalez-Tortuero, E.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. Biology and taxonomy of crAss-like Bacteriophages, the most abundant virus in the human gut. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutilh, B.E.; Cassman, N.; McNair, K.; Sanchez, S.E.; Silva, G.G.Z.; Boling, L.; Barr, J.J.; Speth, D.R.; Seguritan, V.; Aziz, R.K.; Felts, B.; Dinsdale, E.A.; Mokili, J.L.; Edwards, R.A. A Highly Abundant Bacteriophage Discovered in the Unknown Sequences of Human Faecal Metagenomes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkoporov, A.N.; Khokhlova, E.V.; Fitzgerald, C.B.; Stockdale, S.R.; Draper, L.A.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. ΦCrAss001 Represents the Most Abundant Bacteriophage Family in the Human Gut and Infects Bacteroides intestinalis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerin, E.; Shkoporov, A.N.; Stockdale, S.R.; Comas, J.C.; Khokhlova, E.V.; Clooney, A.G.; Daly, K.M.; Draper, L.A.; Stephens, N.; Scholz, D.; et al. Isolation and Characterisation of FcrAss002, a CrAss-like Phage from the Human Gut That Infects Bacteroides Xylanisolvens. Microbiome 2021, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Goldobina, E.; Govi, B.; Shkoporov, A.N. Bacteriophages of the Order Crassvirales: What Do We Currently Know about This Keystone Component of the Human Gut Virome? Biomolecules 2023, 13, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hryckowian, A.J.; Merrill, B.D.; Porter, N.T.; Van Treuren, W.; Nelson, E.J.; Garlena, R.A.; Russell, D.A.; Martens, E.C.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron-Infecting Bacteriophage Isolates Inform Sequence-Based Host Range Predictions. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Barbero, M.D.; Gómez-Gómez, C.; Sala-Comorera, L.; Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Morales-Cortes, S.; Mendoza-Barberá, E.; Vique, G.; Toribio-Avedillo, D.; Blanch, A.R.; Ballesté, E.; Garcia-Aljaro, C.; Muniesa, M. Characterization of crAss-like phage isolates highlights Crassvirales genetic heterogeneity and worldwide distribution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulyaeva, A.; Garmaeva, S.; Ruigrok, R.A.A.A.; Wang, D.; Riksen, N.P.; Netea, M.G.; Wijmenga, C.; Weersma, R.K.; Fu, J.; Vila, A.V.; Kurilshikov, A.; Zhernakova, A. Discovery, diversity, and functional associations of crAss-like phages in human gut metagenomes from four Dutch cohorts. Cell Rep. 2021, 38, 110204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomofuji, Y.; Kishikawa, T.; Maeda, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Otake-Kasamoto, Y.; Kawabata, S.; Nii, T.; Okuno, T.; Oguro-Igashira, E.; Kinoshita, M.; Takagaki, M.; Oyama, N.; Todo, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Sonehara, K.; Yagita, M.; Hosokawa, A.; Motooka, D.; Matsumoto, Y.; Matsuoka, H.; Yoshimura, M.; Ohshima, S.; Shinzaki, S.; Nakamura, S.; Iijima, H.; Inohara, H.; Kishima, H.; Takehara, T.; Mochizuki, H.; Takeda, K.; Kumanogoh, A.; Okada, Y. Prokaryotic and viral genomes recovered from 787 Japanese gut metagenomes revealed microbial features linked to diets, populations, and diseases. Cell Genom. 2022, 2, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargin, E.; Roach, M. J.; Skye, A.; Papudeshi, B.; Inglis, L. K.; Mallawaarachchi, V.; Grigson, S. R.; Harker, C.; Edwards, R. A.; Giles, S. K. The human gut virome: composition, colonization, interactions, and impacts on human health. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 963173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honap, T.P.; Sankaranarayanan, K.; Schnorr, S.L.; Ozga, A.T.; Warinner, C.; Lewis, C.M. Biogeographic study of human gut-associated crAssphage suggests impacts from industrialization and recent expansion. PLoS One, 2020; 15, e0226930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.A.; Vega, A.A.; Norman, H.M.; Ohaeri, M.; Levi, K.; Dinsdale, E.A.; Cinek, O.; Aziz, R.K.; McNair, K.; Barr, J.J.; et al. Global Phylogeography and Ancient Evolution of the Widespread Human Gut Virus crAssphage. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Paul, S.; Dutta, C. Geography, Ethnicity or Subsistence-Specific Variations in Human Microbiome Composition and Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Ferrando, E.; Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Falcó, I.; Randazzo, W.; Sánchez, G. Monitoring Human Viral Pathogens Reveals Potential Hazard for Treated Wastewater Discharge or Reuse. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 836193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabar, M.A.; Honda, R.; Haramoto, E. CrAssphage as an Indicator of Human-Fecal Contamination in Water Environment and Virus Reduction in Wastewater Treatment. Water Research 2022, 221, 118827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, K.; Linke, R.; Ballesté, E.; Reischer, G.; Mayer, R.E.; Vierheilig, J.; Kolm, C.; Stevenson, M.E.; Derx, J.; Kirschner, A.K.T.; et al. Have Genetic Targets for Faecal Pollution Diagnostics and Source Tracking Revolutionized Water Quality Analysis Yet? FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2023, 47, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yutin, N.; Benler, S.; Shmakov, S.A.; Wolf, Y.I.; Tolstoy, I.; Rayko, M.; Antipov, D.; Pevzner, P.A.; Koonin, E.V. Analysis of metagenome-assembled viral genomes from the human gut reveals diverse putative CrAss-like phages with unique genomic features. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobysheva, A.V.; Panafidina, S.A.; Kolesnik, M.V.; Klimuk, E.I.; Minakhin, L.; Yakunina, M.V.; Borukhov, S.; Nilsson, E.; Holmfeldt, K.; Yutin, N.; et al. Structure and Function of Virion RNA Polymerase of a crAss-like Phage. Nature 2020, 589, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Gingery, M.; Abebe, M.; Arambula, D.; Czornyj, E.; Handa, S.; Khan, H.; Liu, M.; Pohlschroder, M.; Shaw, K.; Du, A.; Guo, H.; Ghosh, P.; Miller, J.; Zimmerly, S. Diversity-generating retroelements: natural variation, classification and evolution inferred from a large-scale genomic survey. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Arambula, D.; Ghosh, P.; Miller, J.F. Diversity-generating retroelements in phage and bacterial genomes. Microbiol Spectrum, 2014; 2, MDNA3-0029-2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Paul, B.G.; Bagby, S.C.; Nayfach, S.; Allen, M.A.; Attwood, G.; Cavicchioli, R.; Chistoserdova, L.; Gruninger, R.J.; Hallam, S.J.; et al. Ecology and Molecular Targets of Hypermutation in the Global Microbiome. Nature Communications 2021 12:1 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, S.; Shaw, K.L.; Ghosh, P. Crystal structure of a Thermus aquaticus diversity-generating retroelement variable protein. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0205618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coq, J.; Ghosh, P. Conservation of the C-type lectin fold for massive sequence variation in a Treponema diversity-generating retroelement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108, 14649–14653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, F.; Ye, Y. MyDGR: A Server for Identification and Characterization of Diversity-Generating Retroelements. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, W289–W294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, T.; Lisfi, M.; Chi, J. Analysis of a comprehensive dataset of diversity generating retroelements generated by the program DiGReF. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ryu, S. Antirepression System Associated with the Life Cycle Switch in the Temperate Podoviridae Phage SPC32H. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 11775–11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yong, S.; Zhou, X.; Shen, J. Characterization of a New Temperate Escherichia Coli Phage vB_EcoP_ZX5 and Its Regulatory. Protein. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, T.A.; Mooney, D.; Thomason, L.C.; Stahl, F.W. Gene Products Encoded in the ninR Region of Phage λ Participate in Red-mediated Recombination. Genes to Cells 2002, 7, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Hargreaves, K.; Abedon, S.T.; Sullivan, M.B. Lysogeny in nature: mechanisms, impact and ecology of temperate phages. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łobocka, M.B.; Rose, D.J.; Plunkett, G., III; Rusin, M.; Samojedny, A.; Lehnherr, H.; Yarmolinsky, M.B.; Blattner, F.R. Genome of Bacteriophage P1. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 7032–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravin, N.V. N15: the linear phage-plasmid. Plasmid. 2011, 65, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Yutin, N. The crAss-like Phage Group: How Metagenomics Reshaped the Human Virome. Trends in Microbiology 2020, 28, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedžet, S.; Rupnik, M.; Accetto, T. Broad Host Range May Be a Key to Long-Term Persistence of Bacteriophages Infecting Intestinal Bacteroidaceae Species. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babkin, I.; Tikunov, A.; Morozova, V.; Matveev, A.; Morozov, V.V.; Tikunova, N. Genomes of a Novel Group of Phages That Use Alternative Genetic Code Found in Human Gut Viromes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garneau, J.R.; Depardieu, F.; Fortier, L.C.; Bikard, D.; Monot, M. PhageTerm: A tool for fast and accurate determination of phage termini and packaging mechanism using next-generation sequencing data. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations Using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, T.M.; Chan, P.P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: Search and Contextual Analysis of Transfer RNA Genes. Nucl. Acids Res. 2016, 44, W54–W57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kuronishi, M.; Uehara, H.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. Viptree: The viral proteomic tree server. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, C.; Varsani, A.; Kropinski, A.M. VIRIDIC—A novel tool to calculate the intergenomic similarities of prokaryote-infecting viruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, E.M.; Brister, J.R. How to Name and Classify Your Phage: An Informal Guide. Viruses 2017, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Adriaenssens, E.M. A Roadmap for genome-based phage taxonomy. Viruses 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notredame, C.; Higgins, D.G.; Heringa, J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 302, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Nguyen, M.A.T.; von Haeseler, A. Ultrafast Approximation for Phylogenetic Bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Néron, B.; Littner, E.; Haudiquet, M.; Perrin, A.; Cury, J.; Rocha, E. IntegronFinder 2.0: Identification and Analysis of Integrons across Bacteria, with a Focus on Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A Better, Faster Version of the PHAST Phage Search Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W16–W21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L.; Laiho, A.; Törönen, P.; Salgado, M. DALI Shines a Light on Remote Homologs: One Hundred Discoveries. Protein Science 2022, 32, e4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

CrAssE-Sib phage genome map. CDS (coding DNA sequences) are colored according to their proposed function: DNA replication – blue, head assembly and structural – green, transcription – black, and reverse transcriptase – pink.

Figure 1.

CrAssE-Sib phage genome map. CDS (coding DNA sequences) are colored according to their proposed function: DNA replication – blue, head assembly and structural – green, transcription – black, and reverse transcriptase – pink.

Figure 2.

ViPTree analysis of the crAssE-Sib phage. Dendrogram plotted by ViPTree using crAssE-Sib and phages with SG values > 0.001. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a blue asterisk; phage sequences that were downloaded from the NCBI GenBank manually are marked with red phylogenetic branches.

Figure 2.

ViPTree analysis of the crAssE-Sib phage. Dendrogram plotted by ViPTree using crAssE-Sib and phages with SG values > 0.001. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a blue asterisk; phage sequences that were downloaded from the NCBI GenBank manually are marked with red phylogenetic branches.

Figure 3.

Bidirectional clustering heatmap visualizing VIRIDIC-generated similarity matrix for the crAssE-Sib and close phage genomes. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a blue asterisk.

Figure 3.

Bidirectional clustering heatmap visualizing VIRIDIC-generated similarity matrix for the crAssE-Sib and close phage genomes. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a blue asterisk.

Figure 4.

Comparative genome alignment of the crAssE-Sib and close phage genomes. Analysis was performed using VipTree software. The percentage of sequence similarity is indicated in color; the color scale is shown at the top. .

Figure 4.

Comparative genome alignment of the crAssE-Sib and close phage genomes. Analysis was performed using VipTree software. The percentage of sequence similarity is indicated in color; the color scale is shown at the top. .

Figure 5.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib terminase large subunit generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates are marked with asterisks. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 5.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib terminase large subunit generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates are marked with asterisks. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 6.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib primase generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates are marked with asterisks. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 6.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib primase generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates are marked with asterisks. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 7.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib RNA polymerase generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates are marked with asterisks. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 7.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib RNA polymerase generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates are marked with asterisks. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 8.

Map of a crAssE-Sib genome fragment containing a receptor binding protein (RBP) and reverse transcriptase (RT) genes.

Figure 8.

Map of a crAssE-Sib genome fragment containing a receptor binding protein (RBP) and reverse transcriptase (RT) genes.

Figure 9.

Sequence logos representations of (A) nucleotide multiple sequence alignment of TRs from DGR cassettes and (B) amino acid multiple sequence alignment of VRs from target genes of crAssE-Sib and related sequences.

Figure 9.

Sequence logos representations of (A) nucleotide multiple sequence alignment of TRs from DGR cassettes and (B) amino acid multiple sequence alignment of VRs from target genes of crAssE-Sib and related sequences.

Figure 10.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib reverse transcriptase generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance are marked with asterisks calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 10.

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of the crAssE-Sib reverse transcriptase generated using IQ-tree software. The crAssE-Sib phage is marked with a black circle. Nodes with 95% statistical significance are marked with asterisks calculated from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) replicates. The scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

Figure 11.

Comparison between 3D model of crAssE-Sib receptor binding protein (RPB) and experimental structures of TaqVP protein from Thermus aquaticus and Mtd protein of the BPP-1 phage. VR regions are in green, magenta alpha helices show similar orientation of the molecules.

Figure 11.

Comparison between 3D model of crAssE-Sib receptor binding protein (RPB) and experimental structures of TaqVP protein from Thermus aquaticus and Mtd protein of the BPP-1 phage. VR regions are in green, magenta alpha helices show similar orientation of the molecules.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).