Submitted:

08 December 2023

Posted:

08 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We adopt CRISP-DM Methodology, analyzing six distinct time stages, enhancing the temporal accuracy of forest fire predictions.

- We Implement feature selection techniques to refine and improve the prediction quality and reduce potential noise from irrelevant data.

- We systematically compare a variety of machine learning models to determine the most effective one for forest fire prediction.

- To simulate the effectiveness of our procedure, we apply the models on a real-world dataset which resulted in superior predictive outcomes, showcasing an enhanced level of accuracy in forecasting when compared to results reported in previous literature.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Bibliometric Analysis

2.2. Systematic Review

3. Methodology

3.1. CRISP-DM Methodology

3.2. Data Understanding

3..3. Data Preparation

3.4. Modeling

4. Result

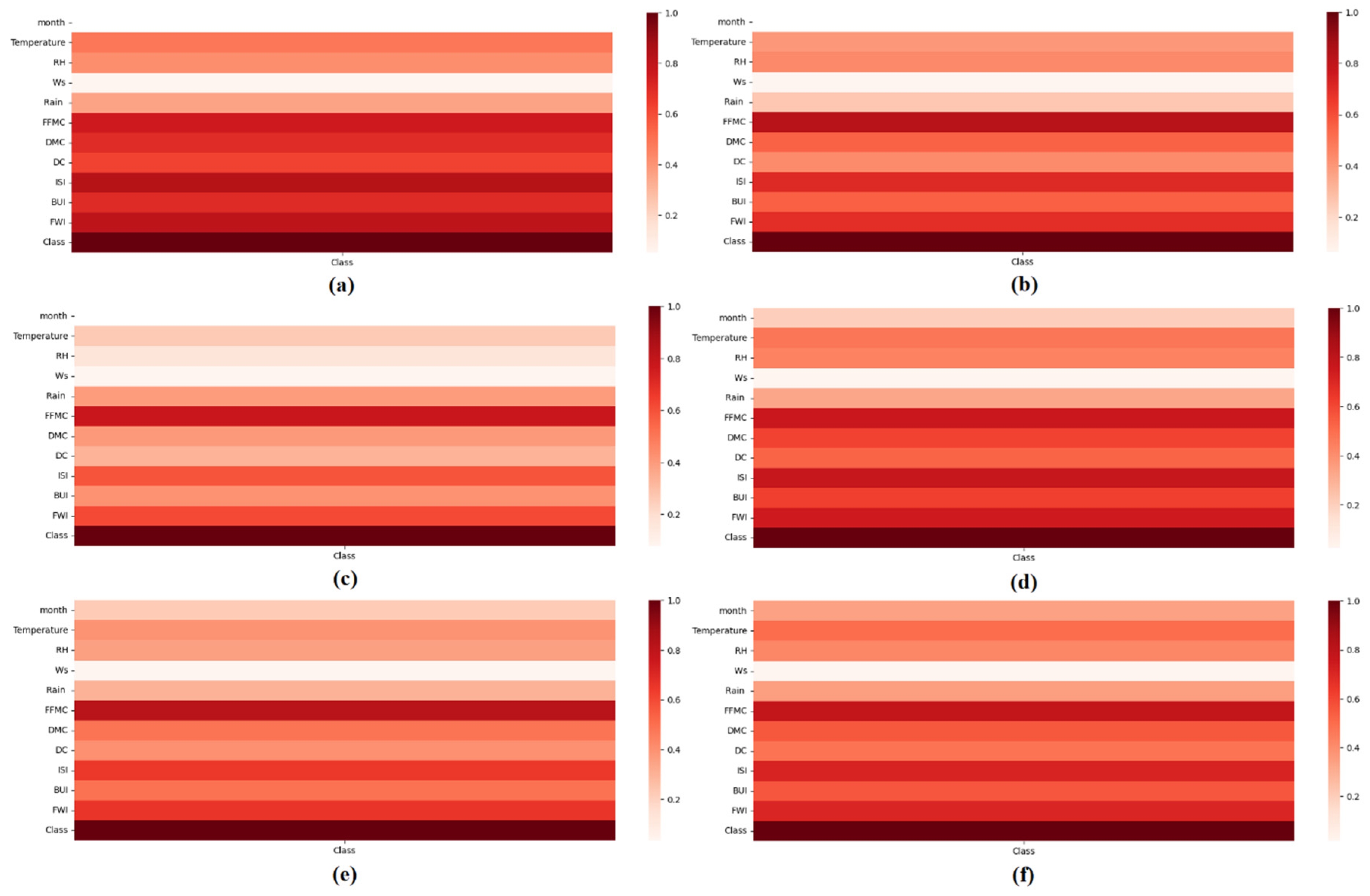

4.1. Feature Selection

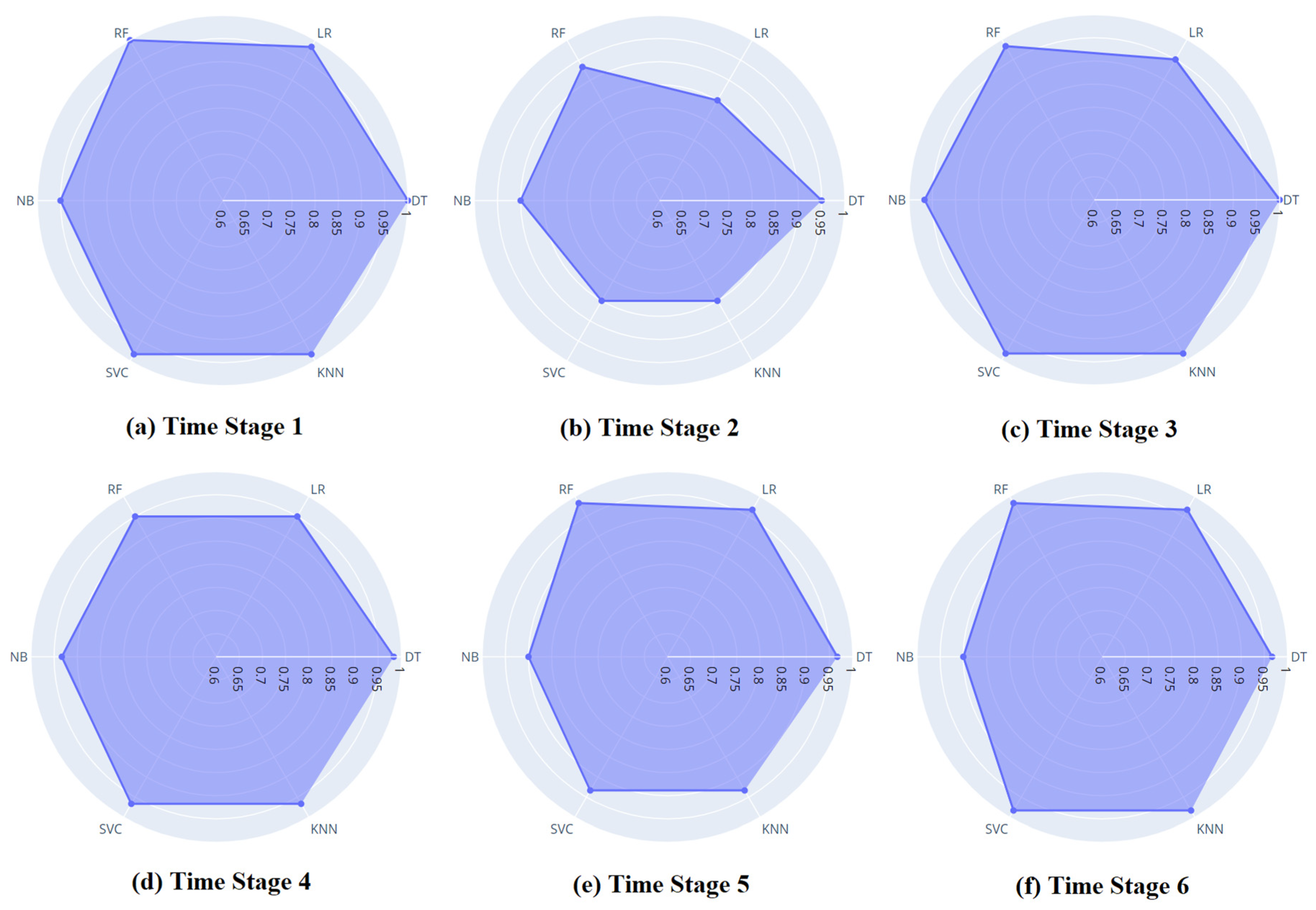

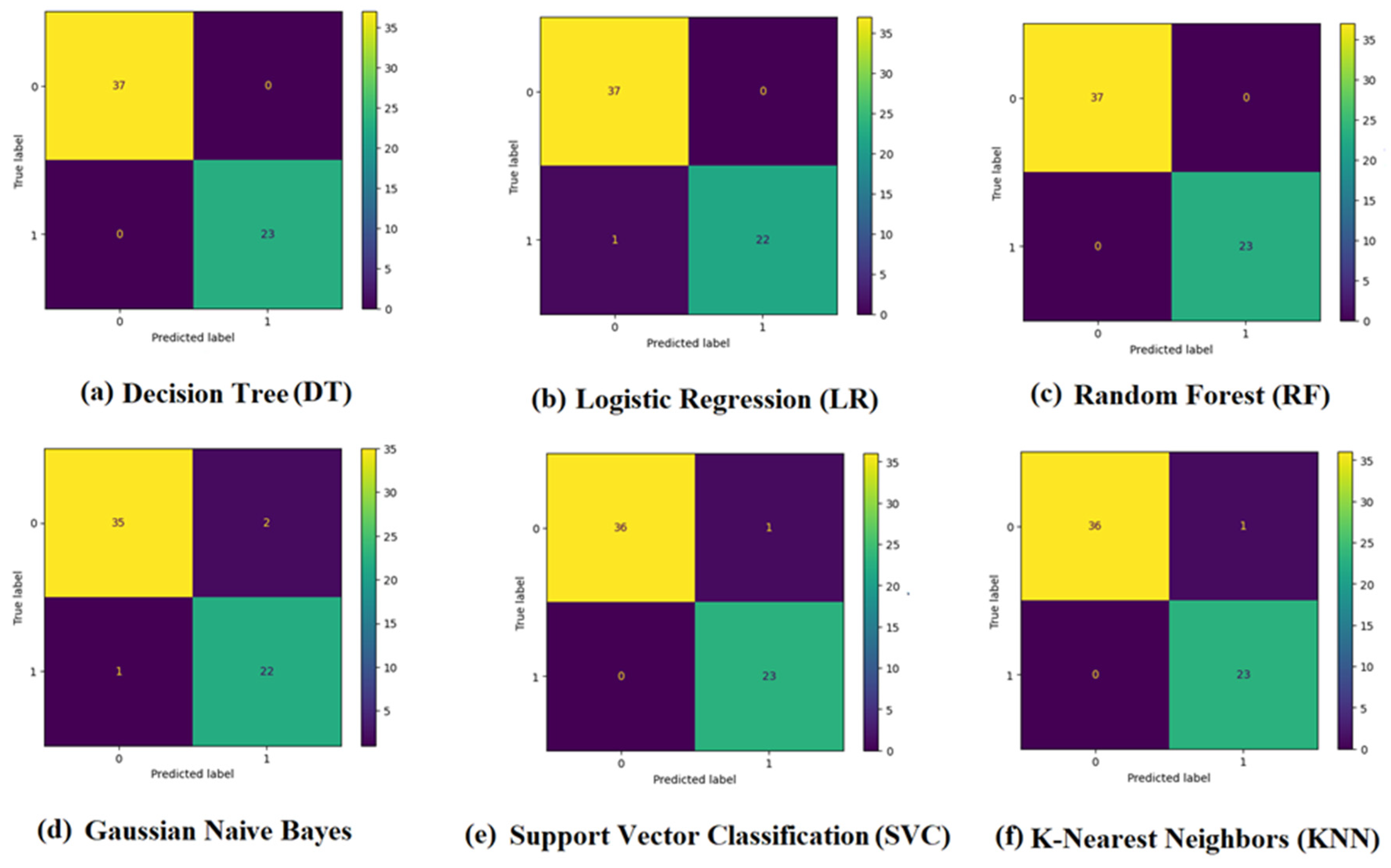

4.2. Best Time stage

5. Conclusion

References

- Cheng, T.; Wang, J. Integrated spatio-temporal data mining for forest fire prediction. Trans. GIS 2008, 12(5), 591-611. [CrossRef]

- Mitri, G.; Gitas, I. A semi-automated object-oriented model for burned area mapping in the Mediterranean region using Landsat-TM imagery. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2004, 13, 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Amil, M. Forest fires in Galicia (Spain): Threats and challenges for the future. J. For. Econ. 2007, 13, 1–5.

- Bianchinia, G.; Denhama, M.; Cortésa, A.; Margalefa, T.; Luquea, E. Improving forest-fire prediction by applying a statistical approach. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 234(S1), 210. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Du, Y.; Niu, S.; Zhao, J. Modeling Forest lightning fire occurrence in the Daxinganling Mountains of Northeastern China with MAXENT. Forests 2015, 6(5), 1422-1438. [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, S.; Mandal, R. Forest fire occurrence, distribution and future risks in Arghakhanchi district, Nepal. J. Geogr. 2020, 2, 10–20. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341701669 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Avilaflores, D.Y.; Pompagarcia, M.; Antonionemiga, X.; Rodrigueztrejo, D.A.; Vargasperez, E.; Santillan-Perez, J. Driving factors for forest fire occurrence in Durango State of Mexico: A geospatial perspective. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 491–497. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, Z.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H. Forest Fire Occurrence Prediction in China Based on Machine Learning Methods. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5546. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.R.; Neethu, K.P.; Madhurekaa, K.; Harita, A.; Mohan, P. Parallel SVM model for forest fire prediction. Soft Comput. Lett. 2021, 3, 100014. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yang, Y.; Peng, L.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J. Spatio-Temporal Knowledge Graph Based Forest Fire Prediction with Multi Source Heterogeneous Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3496. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Jaafari, A.; Zenner, E.K.; Pham, B.T. Wildfire spatial pattern analysis in the Zagros Mountains, Iran: A comparative study of decision tree-based classifiers. Ecol. Inform. 2018, 43, 200–211. [CrossRef]

- Gholamnia, K.; Gudiyangada Nachappa, T.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Blaschke, T. Comparisons of Diverse Machine Learning Approaches for Wildfire Susceptibility Mapping. Symmetry 2020, 12, 604. [CrossRef]

- Thach, N.N.; Ngo, D.B.-T.; Xuan-Canh, P.; Hong-Thi, N.; Thi, B.H.; Nhat-Duc, H.; Dieu, T.B. Spatial pattern assessment of tropical forest fire danger at Thuan Chau area (Vietnam) using GIS-based advanced machine learning algorithms: A comparative study. Ecol. Inform. 2018, 46, 74–85. [CrossRef]

- Goldarag, Y.J.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Ardakani, A. Fire risk assessment using neural network and logistic regression. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2016, 44, 885–894. [CrossRef]

- Jaafari, A.; Razavi Termeh, S.V.; Bui, D.T. Genetic and firefly metaheuristic algorithms for an optimized neuro-fuzzy prediction modeling of wildfire probability. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 243, 358–369. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moayedi, H.; Mehrabi, M.; Bui, D.T.; Pradhan, B.; Foong, L.K. Fuzzy-metaheuristic ensembles for spatial assessment of forest fire susceptibility. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 109867. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Jones, S.; Shabani, F.; Martínez-Álvarez, F.; Tien Bui, D. A novel ensemble modeling approach for the spatial prediction of tropical forest fire susceptibility using LogitBoost machine learning classifier and multi-source geospatial data. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 137, 637–653. [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Jaafari, A.; Avand, M.; Al-Ansari, N.; Dinh Du, T.; Yen, H.P.H.; Phong, T.V.; Nguyen, D.H.; Le, H.V.; Mafi-Gholami, D.; Prakash, I.; Thi Thuy, H.; Tuyen, T.T. Performance Evaluation of Machine Learning Methods for Forest Fire Modeling and Prediction. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1022. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Bonazountas, M.; Kallidromitou, D.; Kassomenos, P.; Passas, N. A decision support system for managing forest fire casualties. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 84(4), 412-418. [CrossRef]

- Vakalis, D.; Sarimveis, H.; Kiranoudis, C.; Alexandridis, A.; Bafas, G. A GIS based operational system for wildland fire crisis management I. Mathematical modelling and simulation. Appl. Math. Model. 2004, 28(4), 389-410. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for Bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2009, 84(2), 523–538. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetrics 2017, 11(4), 959–975. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Iliadis, L.S. A decision support system applying an integrated fuzzy model for long-term forest fire risk estimation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2005, 20(5), 613-621. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, E.E.; Formaggio, A.R.; Shimabukuro, Y.E.; Arcoverde, G.F.B.; Hansen, M.C. Predicting Forest fire in the Brazilian Amazon using MODIS imagery and artificial neural networks. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 2009, 11(4), 265-272. [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.V.K.; Izquierdo, E. A probabilistic approach for vision-based fire detection in videos. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2010, 20(5), 721-731. [CrossRef]

- Sakr, G.E.; Elhajj, I.H.; Mitri, G. Efficient Forest fire occurrence prediction for developing countries using two weather parameters. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2011, 24(5), 888-894. [CrossRef]

- Özbayoğlu, A.M.; Bozer, R. Estimation of the burned area in forest fires using computational intelligence techniques. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 12, 282-287. [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.; Kang, D.J. Fire detection system using random forest classification for image sequences of complex background. Opt. Eng. 2013, 52(6), 067202. [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.D.; de Neufville, R.; Claro, J.; Oliveira, T.; Pacheco, A.P. Forest fire management to avoid unintended consequences: A case study of Portugal using system dynamics. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 130, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Karouni, A.; Daya, B.; Chauvet, P. Applying decision tree algorithm and neural networks to predict forest fires in Lebanon. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2014, 63, 282-291.

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Xu, L.; Guo, H. Deep convolutional neural networks for forest fire detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Forum on Management, Education and Information Technology Application, Atlantis Press, 2016; pp. 568-575.

- Saputra, F.A.; Al Rasyid, M.U.H.; Abiantoro, B.A. Prototype of early fire detection system for home monitoring based on Wireless Sensor Network. In 2017 International Electronics Symposium on Engineering Technology and Applications, IEEE, 2017; pp. 39-44.

- Muhammad, K.; Ahmad, J.; Baik, S.W. Early fire detection using convolutional neural networks during surveillance for effective disaster management. Neurocomputing 2018, 288, 30-42. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Peng, M. Forest fire forecasting using ensemble learning approaches. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 4541-4550. [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Jaafari, A.; Avand, M.; Al-Ansari, N.; Dinh Du, T.; Yen, H.P.H.; Phong, T.V.; Nguyen, D.H.; Le, H.V.; Mafi-Gholami, D.; Prakash, I. Performance evaluation of machine learning methods for forest fire modeling and prediction. Symmetry 2020, 12(6), 1022. [CrossRef]

- Rosadi, D.; Andriyani, W.; Arisanty, D.; Agustina, D. Prediction of forest fire occurrence in peatlands using machine learning approaches. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Seminar on Research of Information Technology and Intelligent Systems, IEEE, 2020; pp. 48-51.

- Heyns, A.M.; du Plessis, W.; Curtin, K.M.; Kosch, M.; Hough, G. Decision support for the selection of optimal tower site locations for early-warning wildfire detection systems in South Africa. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 28(5), 2299-2333. [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Alghamdi, K.K.; Sahel, S.A.; Alosaimi, S.O.; Alsahaft, M.E.; Alharthi, M.A.; Arif, M. Role of machine learning algorithms in forest fire management: A literature review. J. Robot. Autom. 2021, 5, 212-226.

- Natekar, S.; Patil, S.; Nair, A.; Roychowdhury, S. Forest fire prediction using LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference for Emerging Technology, IEEE, 2021; pp. 1-5.

- Li, B.; Zhong, J.; Shi, G.; Fang, J. Forest Fire Spread Prediction Method based on BP Neural Network. In 2022 9th International Conference on Dependable Systems and Their Applications, IEEE, 2022; pp. 954-959.

- Pawar, S.; Pandit, K.; Prabhu, R.; Samaga, R. A Machine Learning Approach to Forest Fire Prediction Through Environment Parameters. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Engineering, IEEE, 2022; pp. 1-7.

- Sung, J.H.; Ryu, Y.; Seong, K.W. Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Fire Occurrence with Hydroclimatic Condition and Drought Phase over South Korea. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26(4), 2002-2012. [CrossRef]

- Budiningsih, K.; Nurfatriani, F.; Salminah, M.; Ulya, N.A.; Nurlia, A.; Setiabudi, I.M.; Mendham, D.S. Forest Management Units’ Performance in Forest Fire Management Implementation in Central Kalimantan and South Sumatra. Forests 2022, 13(6), 894. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.K.Z.; Sakif, S.M.; Sikder, N.; Masud, M.; Aljuaid, H.; Bairagi, A.K. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Assisted Forest Fire Detection Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2023, 35(3).

- Charizanos, G.; Demirhan, H. Bayesian prediction of wildfire event probability using normalized difference vegetation index data from an Australian forest. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 73, 101899. [CrossRef]

- HOLGADO-VARGAS, M.R. Forest Fire Management and Territorial Governance. J. Surv. Fish. Sci. 2023, 10(3S), 2391-2414.

- Anandaram, H.; Nagalakshmi, M.; Borda, R.F.C.; Kiruthika, K.; Yogadinesh, S. Forest fire management using machine learning techniques. Meas. Sens. 2023, 100659. [CrossRef]

- Wirth, R.; Hipp, J. CRISP-DM: Towards a Standard Process Model for Data Mining. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on the Practical Applications of Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2000; pp. 29–39.

- Chapman, P.; Clinton, J.; Kerber, R.; Khabaza, T.; Reinartz, T.; Shearer, C.; Wirth, R. CRISP-DM 1.0. Step-by-step data mining guide, 2000.

- Abid, F. et al. Predicting Forest Fire in Algeria using Data Mining Techniques: Case Study of the Decision Tree Algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development (AI2SD 2019), Marrakech, Morocco, 08-11 July 2019.

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Xu, L.; Guo, H. Deep convolutional neural networks for forest fire detection. In 2016 International Forum on Management, Education and Information Technology Application, Atlantis Press, 2016; pp. 568–575.

- Kumar, V. and Minz, S., 2014. Feature selection: a literature review. SmartCR, 4(3), pp.211-229. [CrossRef]

- Saadabadi, M S E: Malakshan, S R; Kashiani, H; Nasrabadi, N M. CCFace: Classification Consistency for Low-Resolution Face Recognition, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, G. and Sahin, F., 2014. A survey on feature selection methods. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 40(1), pp.16-28.

- Hall, M.A., 1999. Correlation-based feature selection for machine learning (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Waikato).

| Reference | Year | Data | Novelty/Objective | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | 2005 | Forest fire data from the central Forest Management Service in Athens. | Estimating the forest fire risky areas | Applying an inference mechanism based on fuzzy sets and fuzzy machine learning techniques using a decision support system | Providing successful estimates of areas at risk of forest fire |

| [24] | 2009 | NDVI values calculated from MODIS imagery | Predicting forest fire and detecting areas of high risk of forest fire in the Brazilian Amazon | Employing ANN and multitemporal imagery from the MODIS/Terra-Aqua sensors | Achieving an MSE value of around 0.07 in predicting forest fires in high-risk areas |

| [25] | 2010 | MESH database, which is formed of catastrophe related videos | Proposing computer vision-based fire detection method for identifying fire in videos | Exploiting Naïve Bayes for extraction of features and classification | average false-positive rate of 0.68% and a false-negative rate of 0.028% |

| [26] | 2011 | Weather data provided by the Lebanese Agricultural Research Institute (LARI) | Forest fire occurrence prediction by reducing the number of monitored features. | Artificial neural network (ANN) and support vector machine | outperformance of ANN over SVM by 0.17 on fires and SVM over ANN in the binary classification of fire/no fire scenario |

| [27] | 2012 | 7,920 forest fire records from 2000 and 2009 provided by the Department of Forestry in Turkey | Estimating the burned areas using historical forest fire records and prediction of the lost area and the corresponding fire size | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Radial Basis Function Networks (RBFN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and fuzzy logic | Indicating performance of above 60% in the estimation process. Demonstrating MLP model as the best one using only two inputs (humidity and wind speed) with a more than %65 success rate. |

| [28] | 2013 | Extracting 10,000 and 40,000 of a fire and non-fire samples from video images, of tunnels, downtown, and mountain area. |

Presenting a fire alarm system based on image processing | Random forest (RF) and Markov chain | Detecting fires precisely, robustly, and with high reliability in public places. |

| [29] | 2013 | Forest fire data from Portugal | Exploring the impact of interactions between physical and political systems in forest fire management | System dynamics model | Presenting the unintended consequences of management decision-making when it focuses on fixing rather than preventing problems |

| [30] | 2014 | Meteorological data of the year 2012 for North Lebanon | Forest fires prediction | Using decision trees and backpropagation forward neural networks | Achieving 98.9% precision using a 4-inputs feed-forward neural network in prediction |

| [31] | 2016 | Collecting and creating a dataset with 237 fire images from various online resources | Forest fire occurrence detection using fire images | Exploiting SVM and CNN as classifiers | Achieving accuracy of 90% on global image-level testing using Deep CNN. Demonstrating the accuracy of 92.2% by SVM and 93.1% using CNN |

| [32] | 2017 | Using data from temperature, humidity, CO, and smoke sensors | Early fire detection and home monitoring based on fuzzy logic and wireless sensor network | Fuzzy logic in wireless sensor network | Error ratio: 6.67% (test for 30 sample data) |

| [33] | 2018 | CCTV surveillance cameras and 68,457 images collected from different fire datasets | Proposing an early fire detection framework using for CCTV surveillance cameras | Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) | Accuracy: 94.39% Precision: 0.82 Recall: 0.98 F-Measure: 0.89 |

| [34] | 2019 | Forest fire dataset collected from the northeastern region of Portugal | Predicted the burned area of forest fires and the occurrence of large-scale forest fires | Ensemble learning, including random forests (RFs) and extreme gradient boosting (EGB) | Reaching a prediction accuracy of 72.3% by EGB |

| [35] | 2020 | 57 historical fires and a set of nine spatially explicit explanatory variables | Performance evaluation of machine learning methods for forest fire modeling and prediction | Bayes Network (BN), Naïve Bayes (NB), Decision Tree (DT), and Multivariate Logistic Regression (MLP) machine learning methods | BN model (AUC = 0.96), DT model (AUC = 0.94), NB model (AUC = 0.939), and MLR model (AUC = 0.937) |

| [36] | 2020 | Topographical and meteorological data from South Kalimantan Province | Evaluation of machine learning methods for predicting forest fire occurrence in peatland areas. | Support vector machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighborhood (kNN), Logistic Regression (logreg), Decision Tree (DT), Naïve Bayes (NB), and AdaBoost (DT based) | Accuracy: SVM = 91.8% KNN = 91.8% Logistic Regression = 83.6% Decision Tree (DT) = 90% Naïve Bayes = 86.9% Adaboost (DT Based) = 91.8% |

| [37] | 2021 | Publicly available raster data | Decision support for the selection of optimal tower site locations for early-warning wildfire detection systems | Single-site solution framework and System-site solution framework | Obtaining layouts by the optimization framework significantly outperforms the initial layout concerning both covering objectives. |

| [38] | 2021 | Various resources | Providing a comprehensive review of the usage of different machine learning algorithms in a forest fire or wildfire management | Summarizing recent trends in the forest fire events prediction, detection, spread rate, and mapping of the burned areas | Identifying some potential areas where new technologies and data can help better fire management decision-making. |

| [39] | 2021 | Temporal data of wildfires collected in India | Investigation of wildfire prediction strategies dependent on computerized reasoning. | LSTM network, a time series forecasting Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) | Presenting the ability to predict forest fires with 94.77% accuracy |

| [40] | 2022 | Simulated fire spread raster data obtained by FlamMap | Proposing a method suitable for edge computing to use neural networks to predict the spread of forest fires | Backpropagation (BP) neural network | Achieving a computing speed of 5 seconds which is appropriate for edge computing |

| [41] | 2022 | Forest Fire Dataset | Predicting forest fire through environment parameters | Logistic regression (LR), support vector machine (SVM), and multiple linear regression | Accuracy: Logistic Regression = 80% SVM = 78% Multiple Linear Regression = 75% |

| [42] | 2022 | Forest fire activities and climate data over South Korea | Evaluating the effects of climatic conditions and drought phase on occurrence frequency (OF) of forest fire | Deep Belief Network | Model using only relative humidity (RH): R2 = 0.819 Model using a combination of RH and wind speed (WS): NSE = 0.828 |

| [43] | 2022 | Forest fire management policy, forest fire control practices, and their constraints, and also FMU’s capacity | Analyzing the performance of forest fire-related policy implementation based on Forest Management Units (FMUs) | Measuring the performance of the FMUs by the achievement of the policy objectives and effectiveness of policy implementation | Showing clarity of the policies, standards, and objectives to manage fire for FMUs, and challenges in their implementation, such as limited capacity and resources |

| [44] | 2023 | Dataset for Forest Fire Detection from Mendeley Data | Proposing a forest fire detection method based on a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with separable convolution layers | Identifying forest fires within images with a 97.63% accuracy, 98.00% F1 Score, and 80% Kappa |

| [45] | 2023 | Nine years of data were gathered across Australia | Predicting the wildfire event probability based on a set of environmental predictors and forest vulnerability | Bayesian multiple logistic regression | Predicting a low probability for wildfire events during winter and autumn (< 6%), 31.5% during an average summer and 64.6% during extreme summer conditions |

| [46] | 2023 | Scopus, EBSCO, and SCIELO databases | Analyzing the interaction between both terms to identify what is known about the topic, the existence of previous studies | Searching protocol model with three phases: planning, execution, and results | Governance is inherent to forest fire management |

| [47] | 2023 | Using the temperature (TOA and Ground) and intensity values | Presenting a method for the quantitative evaluation of the efficiency of fire safety management in universities | Data envelopment analysis (DEA) | Proposing accurate method in detecting the forest fire |

| Attribute | Description |

| Region | The region where the data was collected: Sidi Belabbas or Bejaia |

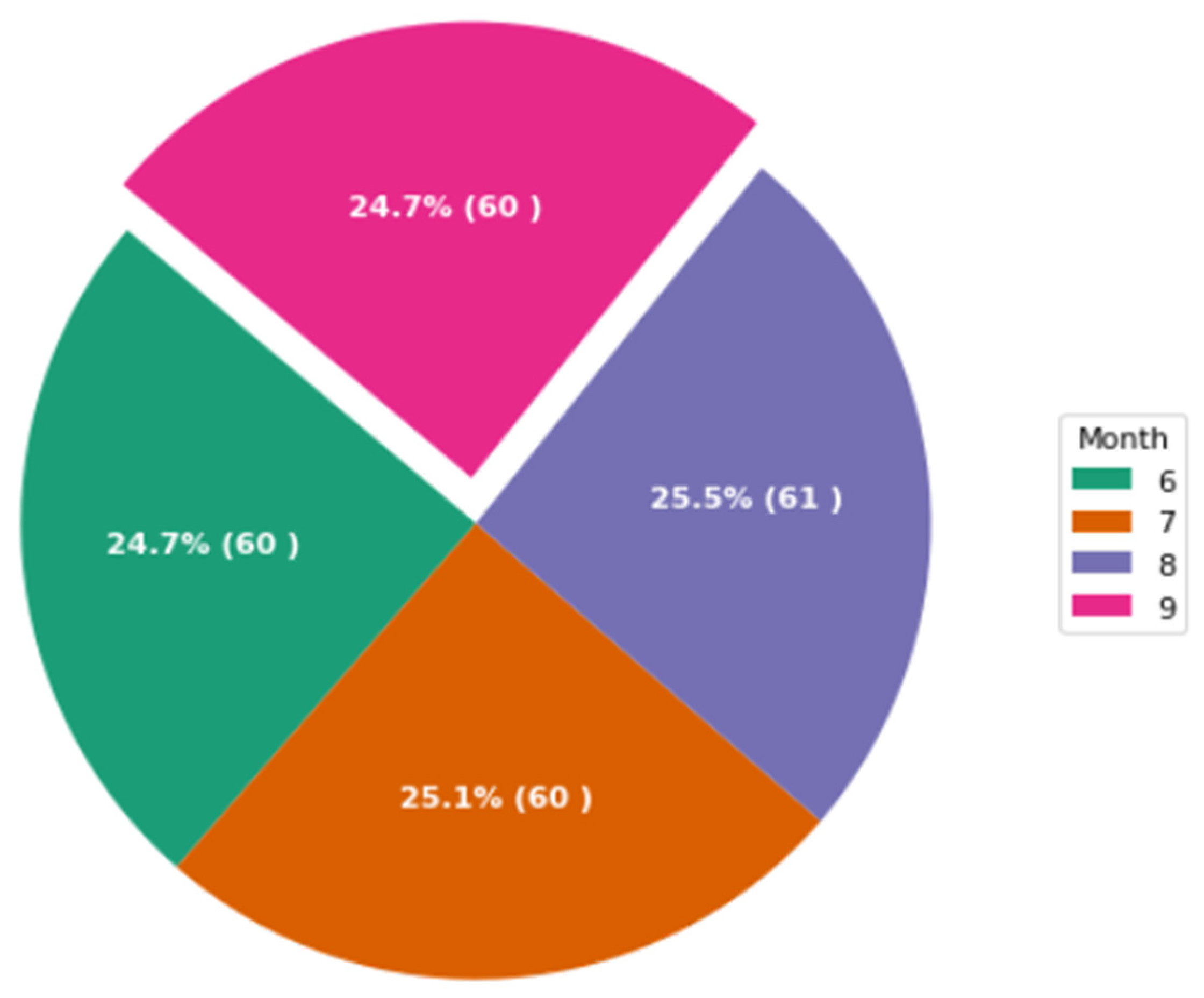

| Date | The date of the meteorological observation |

| Temperature | The temperature in Celsius |

| RH | The relative humidity as a percentage |

| Wind | The wind speed in km/h |

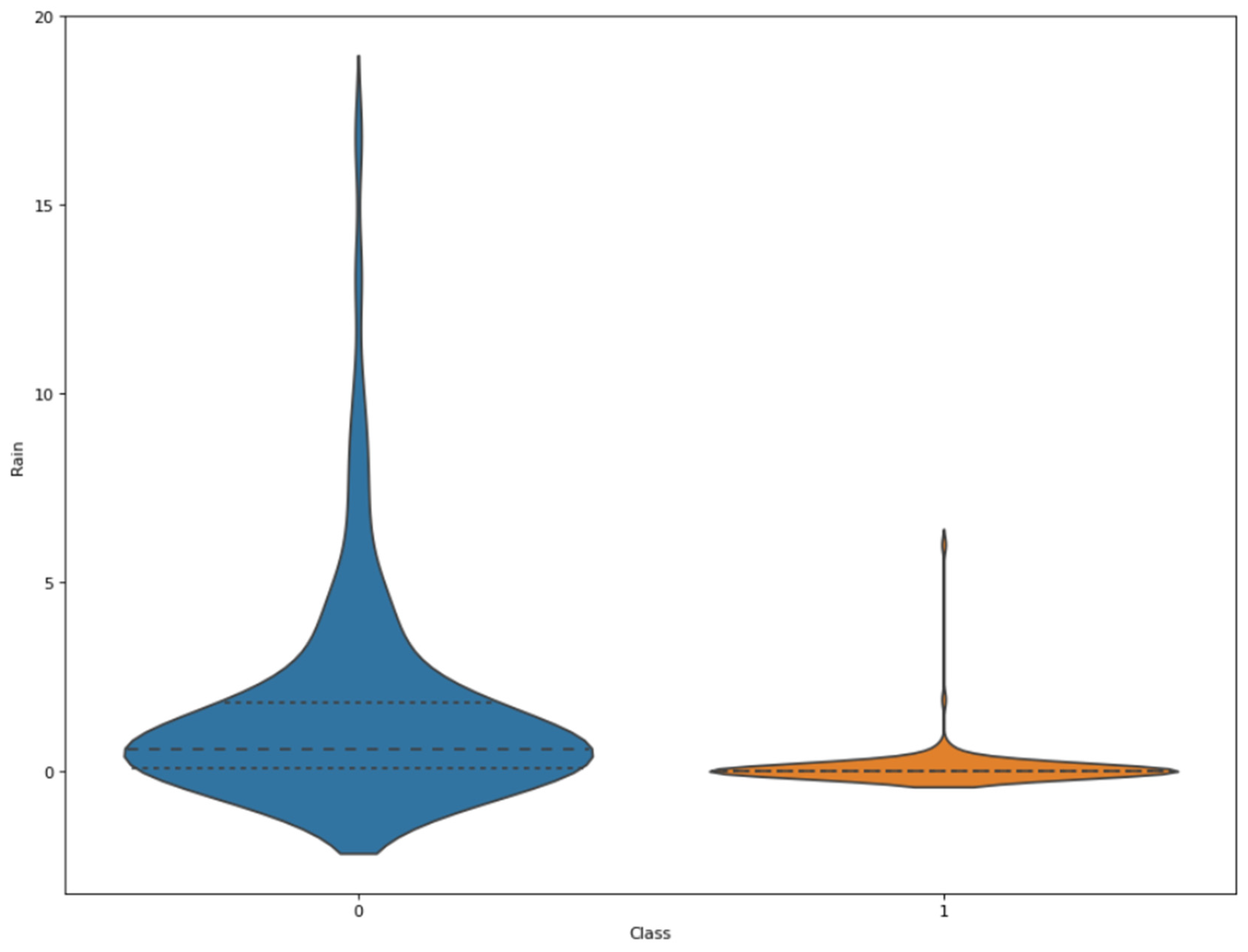

| Rain | The amount of rainfall in mm |

| FFMC | The Fine Fuel Moisture Code, an indicator of the ignition probability |

| DMC | The Duff Moisture Code, an indicator of the fuel consumption potential |

| DC | The Drought Code, an indicator of the fuel moisture content |

| ISI | The Initial Spread Index, an indicator of the potential rate of spread of a fire |

| BUI | The Buildup Index, an indicator of the total amount of fuel available for combustion |

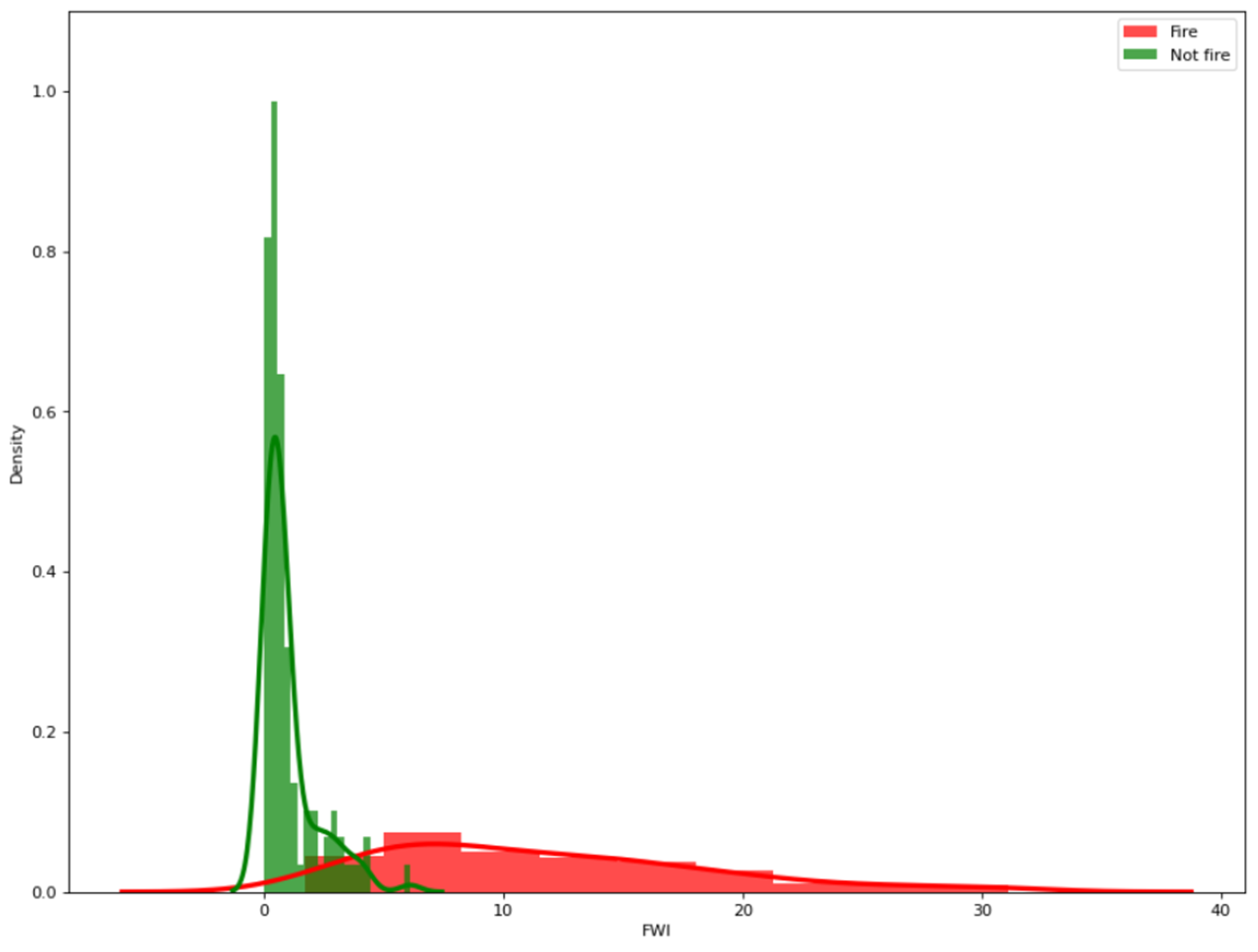

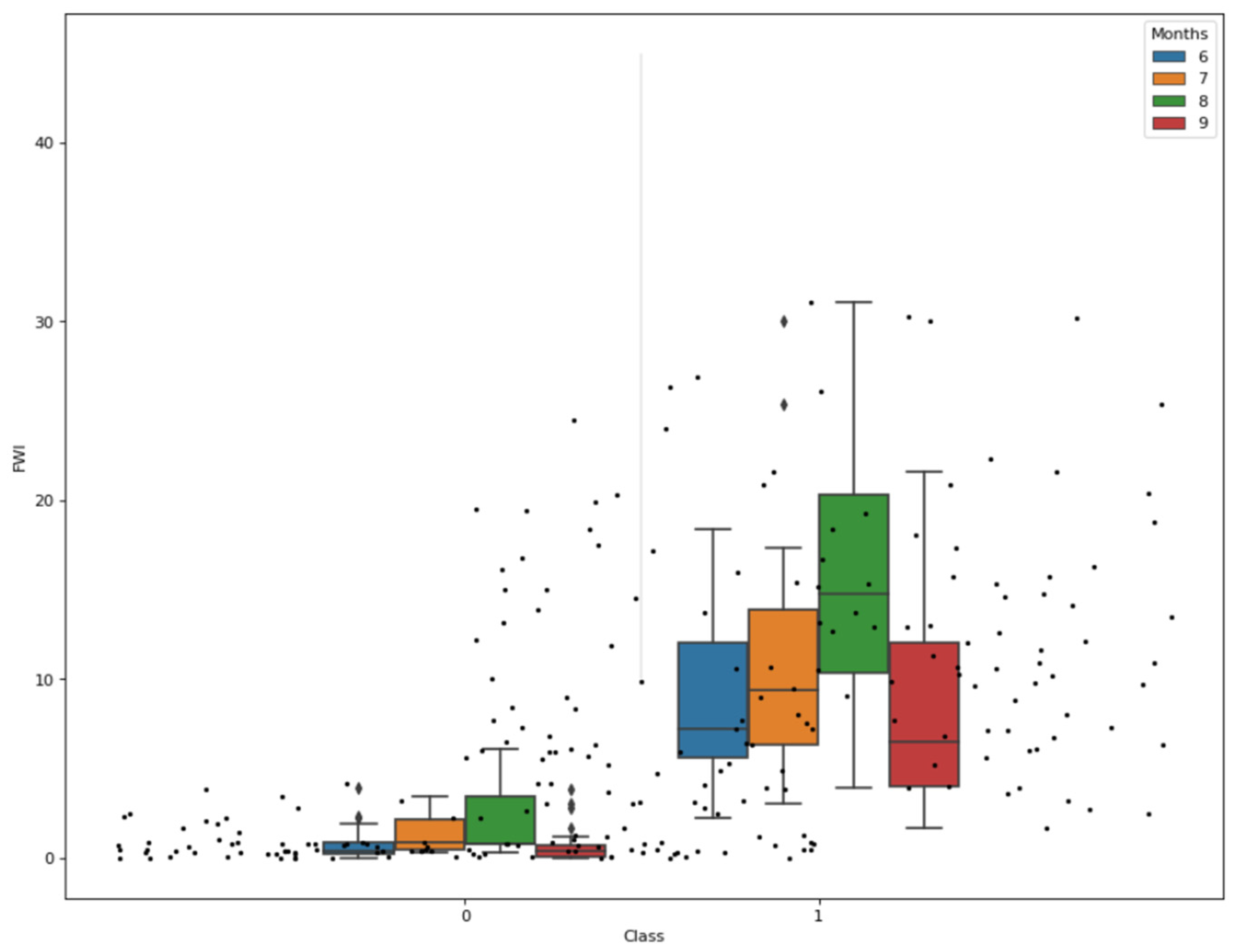

| FWI | The Fire Weather Index, a numerical rating of the potential fire intensity |

| Time Stage one | Time Stage two | Time Stage three | Time Stage four | Time Stage five | Time Stage six | |

| Month | ||||||

| Temperature | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | |

| RH | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | |

| WS | ||||||

| Rain | ☒ | ☒ | ||||

| FFMC | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ |

| DMC | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ |

| DC | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | |

| ISI | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ |

| BUI | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ |

| FWI | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ | ☒ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).