2. From Arenarius to zeroless decimal systems

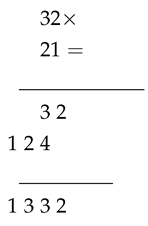

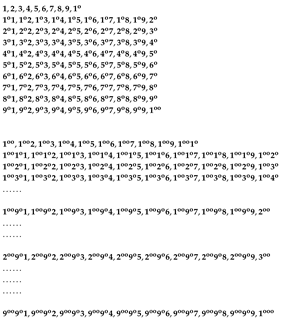

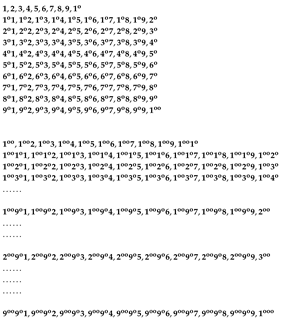

Now we consider Archimedes’ system with a symbolic notation adherent to Arenarius’ formulation given in natural language. For this purpose, we introduce a symbol expressing the end of orders and periods, realized as a circled superscript. We use an initial order of ten numerals, denoted by the usual decimal symbols 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, but ten is denoted by 1

o because it corresponds to the end of the first order. The first period is given completely, the second period is indicated, by omitting some orders.

In the above representation any numeral is a sequence of digits and symbol

for indicating the end of a cycle (order or period). A number of

k consecutive

determines a period of level

k, also called

k-period. For example,

is the numeral of the first 1-period of the first 2-period, at its third order, in the sixth position. In fact, periods are arranged in increasing levels and within a period of level

there are ten

-periods (nono-circled digits correspond to orders). These circled numerals correspond to exponentials, but their forms resemble the linguistic expression of the periodical mechanism used by Archimedes, where small circles provide the arrangement of a cyclic generation of numerals. The translation of circled numerals in exponentials is the product of the exponential interpretation of the circled digits, where:

,

and so on. For example,

represents

.

The circle, which was the central topic of many Archimedes’ investigations [

16], emerges in this symbolism as the basic mechanism of a counting process, by adding to the already seen properties of number enumerations (creativity, order, infinity) the property of recurrence. In fact, all numerals are represented by a finite sets of symbols that continuously recur in the generation. Expressions such as “third order” and “second prime period” translate respectively in 3

o and

.

An enumeration is complete when it generates the numerals of all numbers. In a complete enumeration a number denoted by a numeral coincides with its position in the enumeration. It is reasonable to suppose that John Wallis, who translated Arenarius, when introduced in 1655 the symbol ∞ for infinity,, by rotating the digit 8 in the position of ∞, impressed by the enormous size of Archimedes’ numbers, and inspired by the Archimedean term “octad”, which refers to eight consecutive powers of ten. By the way, the size of universe was evaluated by Archimedes at the eighth order of his first period with a value around (assuming particles in a sand grain, we obtain the modern evaluation for the particles contained in our universe).

The enumeration given above can be defined as a linear ordering defined on monads, where we call monad a digit in or a circled digit, that is, a digit with a number of circles as exponents. Monads are ordered by requiring that if has a number of circles greater than , or when they have the same number of circles, if the digit of is greater than the digit of (9 > 8 > 7 > 6 > 5 > 4 > 3 > 2 >1). A numeral is a sequence of monads where any monad needs to have a smaller number of circles than those on its left. Then, if are DAS numerals, when their leftmost monads and satisfy .

The Archimedes’ enumeration is not complete, because it represents numbers, but not all numbers of the natural succession. In fact, only exponentials or multiples of them appear. However, if we change the interpretation by considering each numeral as the successor of the previous one, then we get a complete enumeration. The obtained system, which we call Decimal Archimedes’ System (DAS), results to be a zeroless system very close to the usual decimal system, which we call 0-decimal system (0DS).

Now, we will translate DAS into another zeroless decimal system, which we call X-decimal system (XDS). At this end, we translate monads in strings over the alphabet of digits 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X:

and so on, for monads with greater number of circles (X, XX,

abbreviates 1X, 1XX,

respectively, when they occur as first monads, from the left). In this way, the first period of DAS in XDS becomes:

X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6, X7, X8, X9, 2X

2X1, 2X2, 2X3, 2X4, 2X5, 2X6, 2X7, 2X8, 2X9, 3X

3X1, 3X2, 3X3, 3X4, 3X5, 3X6, 3X7, 3X8, 3X9, 4X

4X1, 4X2, 4X3, 4X4, 4X5, 4X6, 4X7, 4X8, 4X9, 5X

5X1, 5X2, 5X3, 5X4, 5X5, 5X6, 5X7, 5X8, 5X9, 6X

6X1, 6X2, 6X3, 6X4, 6X5, 6X6, 6X7, 6X8, 6X9, 7X

7X1, 7X2, 7X3, 7X4, 7X5, 7X6, 7X7, 7X8, 7X9, 8X

8X1, 8X2, 8X3, 8X4, 8X5, 8X6, 8X7, 8X8, 8X9, 9X

9X1, 9X2, 9X3, 9X4, 9X5, 9X6, 9X7, 9X8, 9X9, XX

For example, the XDS translation of is . The logic of XDS enumeration is based on powers of ten. 1, X, XX, XXX, …. Any numeral is the concatenation of multiples of these powers, and their sum provides the number expressed by the numeral. It is interesting to remark that this structure resembles exactly the construction of numerals in many natural languages. However, neither DAS, nor XDS are positional systems in the strict sense of our usual decimal system with zero, but could be better characterized as polynomial systems (where monads are monomials). Polynomial system of number representation occur, in primitive forms, in many ancient systems, and in the measurement of angles. The mathematician and astronomer Claudius Ptolomaeus (first century, author of the Almagest) used circled digits, and in some contexts his circle resembles zero.

Going back to DAS numerals, we could avoid to put circles to digits when in a numeral all the monads smaller than the leftmost monad occur. In fact, in that case the level of any monad corresponds to its position. For example, is completely expressed by 136. But, if circles are deleted in and we get, in both cases, 16, which does not distinguish between the two different numerals. However, we can avoid circles if the missing monads are indicated.

Therefore zero, which was discovered at the end of fifth century within the Indo-Arabic mathematical tradition [

11], has a natural motivation in Archimedes’ periodical system, as a new digit 0 expressing the absence of any monad having a number of circles corresponding to its position (distance from the rightmost digit).

Nevertheless, zero digit is not necessary for having a positional systems, because zeroless positional systems in the sense of 0DS can be defined. One of such systems is based on the strings that can be constructed over a finite sets of digits [

2,

15]. Let us assume the ten digits (without zero) in the order:

For each digit, the sting of two digits are generated according to the following square, where ordering is from left to the right in the rows, and from the top to the bottom for the columns:

1(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

2(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

3(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

4(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

5(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

6(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

7(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

8(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

9(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

X(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X)

In general, numerals are generated by orders

, for

.

and:

where numerals of

follow those of

, and for any digit

D, the following equation holds:

with

for any

in

, and

. This is the structure of any enumeration system, over strings, based on orders and periods.

The ordering associated to this enumeration corresponds to the lexicographic ordering, characterized by the following conditions (

is the length of string

, and

are any digits):

We call this enumeration LXS (Lexicographic X-decimal System). LXS is a positional system, where digits contribute to the value of the denoted number according to their positions.

An enumeration system based on orders and periods is an Archimedean Enumeration System (AES). An AES is natural if it is represents all the numbers, it is monotone if its numerals are non empty strings over a finite set of symbols, and any numeral followed by a digit x is a numeral too, such that the number denoted by it coincides with the number of orders before the order where occurs. Such a system has period p if its initial order has p numerals. XDS, as well as the usual decimal positional system D0S, are Archimedean natural monotone enumeration systems.

The following theorem easily generalizes a well-known theorem of positional systems to natural monotone AES.

Theorem 1.

Let E be an Archimedean monotone enumeration system of period p. Then, the following recurrent equation holds in E, for any digit x:

from which the base representation equation follows.

Proof. From the hypotheses on

E, the product

represents the number of numerals before the order where

occurs, then we have the asserted equation above. If we apply iteratively equation (2), we get the fundamental base representation equation of a positional number systems of base

:

□

3. The algorithmic value of digits

One of the main novelties of digits is the

algorist trend as opposed to the

abacist approach of ancient methods of number calculation (from

abacus). In 1585 Simon Stevin published a book in Flemish, entitled

De Thiende (the Tenth) [

20], where the algorithms for computing the four arithmetical operation are given, which correspond to the methods that are now taught in the primary schools. These methods are independent from the particular basis, and essentially reduce the computation of any operation to the knowledge of its results for all the pair of digits., that is, to a finite set of basic rules. The same situation arises with zeroless positional systems.

Let us consider the zeroless lexicographic systems of four digits, having the following first 16 numerals:

| - |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

31 |

32 |

33 |

34 |

Table 1 and

Table 2 express sum and multiplication for a lexicographic systems of four digits.

For example, in the 4-lexicographic system is obtained from the above tables and provides the same result obtained in the usual decimal system:

In conclusion, zero is not necessary for having positional systems, even if it is essential for further developments of mathematics: in the infinitesimal analysis, and in the algebraic structures. In fact, the negative enumeration, which from zero goes back in the opposite direction of the natural (positive) enumeration, gives the negative of any number, makes integers an additive group with zero as neuter element.

In his 1585 book, Stevin introduces a notation essentially equivalent to usual decimal notation. Using this notation, Stevin’s division algorithm applied to , with , provides a decimal representation of type for the fraction , where are decimal digits.

The following theorem is an easy consequence of the pigeonhole principle, where is the succession of prime numbers (if n objects are distributed among cells, then there exists some cell containing more than an object).

Theorem 2. For the fraction has a decimal representation with infinite digits, obtained by the division algorithm, where a sequence of digits, called period, repeat indefinitely, and the length of the period is surely lesser that .

In virtue of the above theorem any fraction has a finite decimal representation or an infinite one, but periodical. Therefore, an infinite decimal representation that is not periodical represent a number that is not a fraction, and is called an irrational number (Greek mathematicians use the term Logoi for irrationals). In conclusion, the existence of irrational numbers follow from Stevin’s representation.

The following theorem is the converse of the above theorem, that is, for any periodical decimal representation there is an equivalent fraction.

Theorem 3.

For every fraction with (set of integers) there exist such that:

with .

Both theorems above can be easily extended to any positional system with zero and base >1. However, computing the exact periodical representation of a fraction and showing its correctness is not an easy task. After Stevin work and Napier’s formulation, in his second book on logarithms [

21], a tradition of works on decimal faction was developed in 17th and 18th centuries [

1].

Now we show as a simple theorem can give an efficient solution for a systematic and reliable determination of the exact periodical representation of fractions. In fact, the following theorem, which can be easily proven, is the basis for efficient algorithms (extensible to any base) for computing fraction periods and for checking their correctness.

Theorem 4 (Concatenation Theorem).

Stevin algorithms for the basic arithmetical operations can be “concatenated”. Let us express this fact only for division and multiplication (concatenation of additions and subtractions are obvious), where Greek letters denote strings of digits of decimal representations.

if with remainder r and with remainder 1.

For some natural n:

if for some naturals :

with and .

By using the theorem above, when arithmetic operations have a precision of p decimal digits, then operations can be concatenated by obtaining periodical representations of any period length, and proving the correctness of the obtained results.

Given the length limits of computer number representation, no computer can directly compute the exact decimal value of a simple fraction such as . The representation of fraction for , based on division and multiplication concatenations, are given below, where periods are indicated within brackets, and stars mark periods that reach the maximum possible length.

1/2 = 0,5 = 0,4[9]

1/3 = 0,[3]

1/5 = 0,2 = 0,1[9]

1/7 = 0,[142857]*

1/11 = 0,[09]

1/13 = 0,[076923]

1/17 = 0,[0588235294117647]*

1/19 = 0,[052631578947368421]*

1/23 = 0,[0434782608695652173913]

1/29 = 0,[0344827586206896551724137931]*

1/31 = 0,[032258064516129]

1/37 = 0,[027]

1/41 = 0,[02439]

1/43 = 0,[023255813953488372093]

1/47 = 0,[0212765957446808510638297872340425531914893617]*

!/53 = 0,[0188679245283]

1/59 = 0,[0169491525423728813559322033898305084745762711864406779661]*

1/61 = 0,[016393442622950819672131147540983606557377049180327868852459]*

1/67 = 0,[014925373134328358208955223880597]

1/71 = 0,[01408450704225352112676056338028169]

1/73 = 0,[013698630136986301369863]

1/79 =0,[01265822784810126582278481]

1/83 = 0,[01204819277108433734939759036144578313253]

1/89 = 0,01123595505617977528089887640449438202247191]

1/97 = 0,[0103092783505154639175257731958762886597938144329896907216494

84536082474226804123711340206185567]*

All these representations were checked by using multiplication concatenation. Moreover they coincide with those, up to 1/67, of Johann III Bernoulli’s table (1771-1773) reported in [

1]. We remark that fraction periodical representations is an issue extensively investigated by Carl Friedrich Gauss, who introduced an entire theory for their calculation [

1].

As an example, the computation of

is here reported, by using operations reliable up 12 digits.

Remainder = 3

where the open bracket is put after the last digit of the period. Namely, digits 058823 coincide the initial digits of the first division. Therefore, by concatenating the two divisions, according to Concatenation Theorem, we have:

Now, we prove the correctness of the above periodical representation, by concatenating two multiplications:

that is:

in fact,

and

, and the concatenation of the two results, according to Concatenations Theorem, is just 9999999999999999.

Gauss spent years in computing decimal periods of prime fractions. For this purpose, he developed a theory [

1] (of

indices), which was the seed of his theory of congruences. The biggest fraction he computed was 1/997, which we computed in seconds with the following Python program, by using Stevin’s division algorithm going up until a remainder is obtained that was already generated. By the way, it is interesting to observe that unitary division is the essence of any division, which is always equivalent to a multiplication of the result of a unitary division.

Let us conclude the section, by shortly reporting other crucial passages that are based on the diffusion in Europe of the positional representation of numbers, after the publication by Leonardo Fibonacci, in 1202, of his

Liber Abaci, along a process of four centuries of conceptual and notational development of the roots of modern mathematics [

3,

13].

In 1591 François Viète’s book [

23] appeared where expressions with symbol for

indeterminates appear, and

ars speciosa is also the name of a new arithmetic perspective that is the seed of modern algebra. In 1619 John Napier introduces logarithms [

21], where he provides a

synchronization between geometrical and arithmetical progressions covering with good approximation a real interval. This passage in modern mathematics is crucial and full of practical and theoretical consequences.

The passage from symbols with numeric meanings to indeterminates of unknown numeric values, on which operations can be performed independently from their meaning, is a crucial step toward variables, which become the main tool of Cartesian geometry. where in 1637 René Descartes introduces coordinates, by reversing the Greek relationship between space and numbers. From this point, the process of arithmetization of mathematics starts, toward the foundational perspectives of 19th and 20th centuries.

Table 4.

Proving that decimal period of 1/997 is correct: The column on tn the left gives, in consecutive rows, blocks of the period d of 1/997. In each equation of the second column, the last 3 digits added to the first 3 digits of the number below provides 999, therefore, according to the Concatenation Theorem, the equations above prove that . whence, being a period, it follows that .

Table 4.

Proving that decimal period of 1/997 is correct: The column on tn the left gives, in consecutive rows, blocks of the period d of 1/997. In each equation of the second column, the last 3 digits added to the first 3 digits of the number below provides 999, therefore, according to the Concatenation Theorem, the equations above prove that . whence, being a period, it follows that .

| 00100300902 |

× |

|

| 7081243731 |

× |

|

| 1935807422 |

× |

|

| 266800401 |

× |

|

| 2036108324 |

× |

|

| 97492477432 |

× |

|

| 29689067201 |

× |

|

| 60481444332 |

× |

|

| 99899699097 |

× |

|

| 2918756268 |

× |

|

| 8064192577 |

× |

|

| 7331995987 |

× |

|

| 96389167502 |

× |

|

| 507522567703 |

× |

|

| 10932798395 |

× |

|

| 18555667 |

× |

|

4. Enumerations in ordinals and in computability

Archimedes’ mark is not only in the roots of moderne mathematics, and in the infinitesimal calculus, for his introduction of geometric representation of infinitesimals, especially in his

Method, a book that got lost and was discovered at beginning of twentieth century (and lost again during the second world war, but now completely restored) [

17]. In fact, the crucial role of recurrence in Archimedes’ enumeration is apparent in Cantor’s ordinal numbers [

4], and in the theory of computability [

22]. Rigorous foundations of numbers were provided by Dedekind, Frege, and Peano [

5,

8,

18], but the most synthetic and expressive definition of numbers is that one given in terms of set theory, according to a construction due to John von Neumann:

a number is the set of numbers that precede it, in a number enumeration. In this way 0 coincides with the empty set

∅, 1 is the set containing the empty set

, 2 is the set

, and so on. In this formulation, even if “a number enumeration” is mentioned, the numbers stem prescinding from any specific system of counting, in a very abstract manner, where the process of counting results the true essence of numbers. In fact if

is any enumeration and

the corresponding numbers, then

,

,

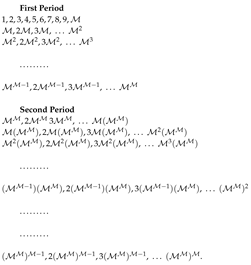

, and so on, by obtaining exactly what von Neumann defined. Moreover, the theory of ordinals can be expressed in terms of enumerations of enumerations, in the same way as Archimedes’ periods are generated, because the essence of a recurrent enumeration is that a number is the position where its numeral is, and this position is completely identified by the numeral that precede it. In this way, if a name a given to an entire enumeration, this name is a sort of hypernumeral that we can imagine as the last position of its numerals. Then, let us call

the natural enumeration

if we assume

as the first infinite order, we can go further with the following orders in an analogous way as Archimedes’ periodical system:

where the name of any (infinite) enumeration is put at the end of it, and usual symbols for ordinals are intended as names of the consecutive enumerations preceding them (enumerations of enumerations, and so on, at successive levels). It is not our intention to go into further details of such an approach to ordinals, but this short outline suggests clearly as ordinals are a natural generalization of Archimedes’ periods.

It can be shown that a 1-to-1 correspondence can be established between the natural enumeration

and ordinals at any exponential level (

), but no 1-to-1 correspondence exists between

and real numbers, which are represented by infinite sequences of decimal digits (and the set of ordinals 1-to-1 with

is an ordinal that is not 1-to-1 with

). This crucial result, based on a famous

diagonal argument, is the access gate to cardinal numbers and abstract sets, or Cantor Paradise, as Hilbert defined set theory [

10], within which any mathematical theory can be expressed.

In 1936 Turing published an epochal paper on computable numbers, that is, real numbers where the sequence of digits can be generated by means of a computing device, a Turing machine. Sets of numbers that can be generated by Turing machine, as outputs of computing process, are called Turing enumerable, or recursively enumerable, sets. However, in general, there is no Turing machine that, given a Turing enumerable set A and a number n, is able to tell, in a finite number of steps, if a does belong or not to A. The sets for which this is possible ale called decidable or recursive. The recursively enumerable sets for which this decision possibility does not hold are called semidecidable. A function is computable if, and only if its graphic is recursively enumerable.

What is really surprising is that Turing proves the existence of recursively enumerable sets, by adapting Cantor’s diagonal argument according to which real numbers are not 1-to-1 with any natural enumeration. This story tells us that an

infinity line [

12] links, along centuries, Archimedes with Cantor and Turing: these three giants follow a common idea:

counting the infinite: according to an arithmetical perspective, to a more general set theoretic perspective, or to a computational perspective of symbolic manipulation processes, performed by machines.

A function on natural numbers is Turing computable if it is computed by some Turing machine (giving as output the image of the function in correspondence to any argument given as input). Turing machines are identified by Turing programs, which are strings, which when put in a lexicographic ordering provide an enumeration. From this, again by a diagonal argument, the following theorem can be proved.

Theorem 5. Turing computable functions surely include partial functions, which do not give results in correspondence of some arguments, and no Turing machine can exist that can always tell, in finite time, if a Turing machine gives a result in correspondence of a given argument.

The numbers denoted by this method are exponentials (of base ) or multiples of exponentials, for tis reason we denoted them in the modern exponential notation. However Archimedes does not use any symbolic notation, but expresses the logic of his method in natural language (Greek), and discovers some basic properties of these numbers and in particular a rule that corresponds to the identity:

The numbers denoted by this method are exponentials (of base ) or multiples of exponentials, for tis reason we denoted them in the modern exponential notation. However Archimedes does not use any symbolic notation, but expresses the logic of his method in natural language (Greek), and discovers some basic properties of these numbers and in particular a rule that corresponds to the identity: In the above representation any numeral is a sequence of digits and symbol for indicating the end of a cycle (order or period). A number of k consecutive determines a period of level k, also called k-period. For example, is the numeral of the first 1-period of the first 2-period, at its third order, in the sixth position. In fact, periods are arranged in increasing levels and within a period of level there are ten -periods (nono-circled digits correspond to orders). These circled numerals correspond to exponentials, but their forms resemble the linguistic expression of the periodical mechanism used by Archimedes, where small circles provide the arrangement of a cyclic generation of numerals. The translation of circled numerals in exponentials is the product of the exponential interpretation of the circled digits, where: , and so on. For example, represents .

In the above representation any numeral is a sequence of digits and symbol for indicating the end of a cycle (order or period). A number of k consecutive determines a period of level k, also called k-period. For example, is the numeral of the first 1-period of the first 2-period, at its third order, in the sixth position. In fact, periods are arranged in increasing levels and within a period of level there are ten -periods (nono-circled digits correspond to orders). These circled numerals correspond to exponentials, but their forms resemble the linguistic expression of the periodical mechanism used by Archimedes, where small circles provide the arrangement of a cyclic generation of numerals. The translation of circled numerals in exponentials is the product of the exponential interpretation of the circled digits, where: , and so on. For example, represents .