Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

-

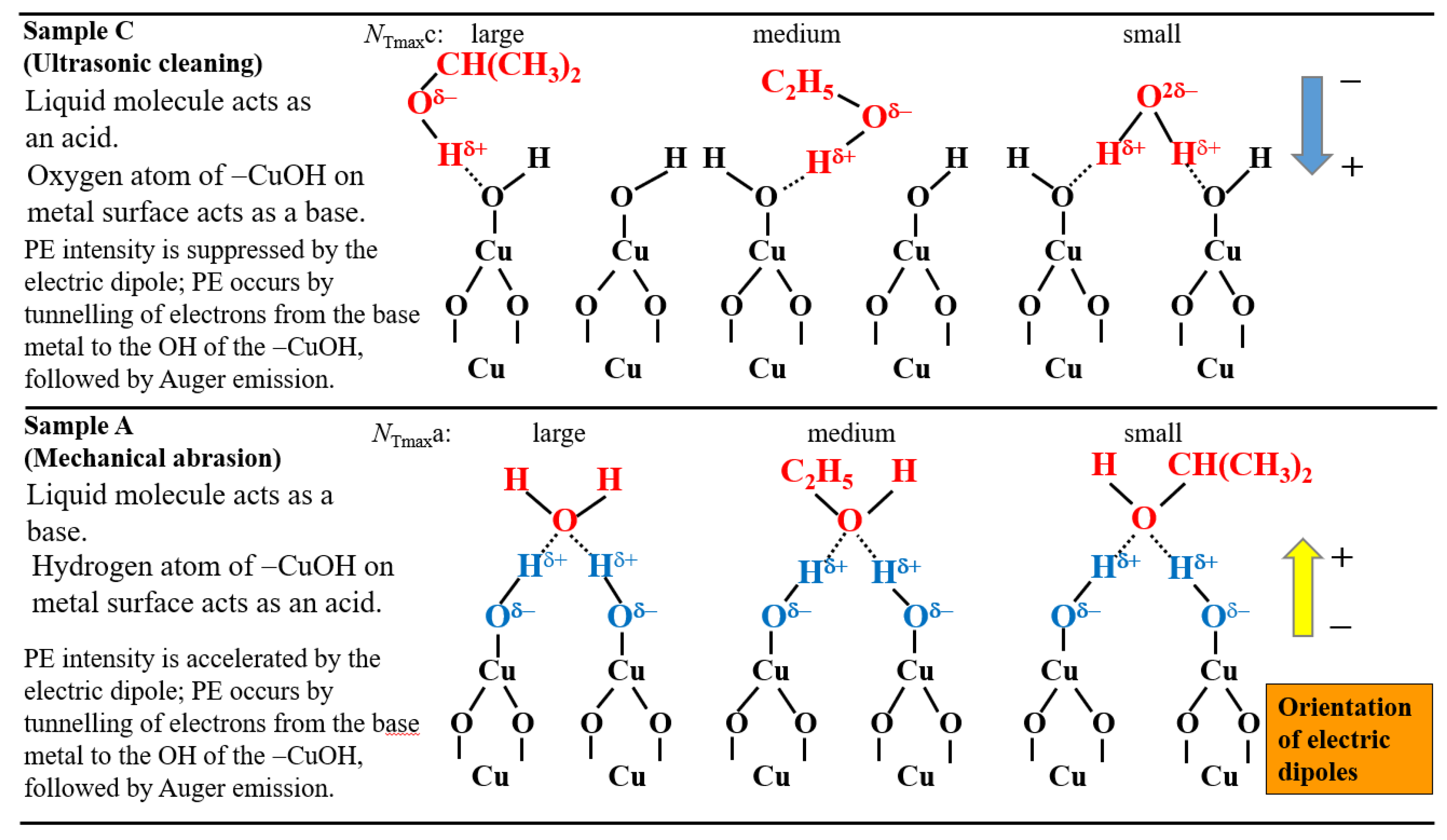

The species and interaction modes appearing in the TPPE method are as follows:(a) the key functional group: −OH group adsorbed on the metal surface and its polarity; (b) the electron density of the oxygen of −OH group, which depends on the negative electric potential and the intensity of irradiated light; (c) the orientation of adsorbate molecules due to the acid-base interaction in the adsorption on the −OH group; (d) the formation of electric dipoles between the −OH group and adsorbate molecules; (e) the change of the components of O1s spectra before and after TPPE measurement.

- (2)

-

The dependence of TPPE on temperature and environment is quantified using PE stimulation spectra [5,6]. The following data and its relationship to the properties of the adsorbate molecules are obtained:

- (a)

- The total count of emitted electrons in the incident light wavelength scan (PE total count, NT), which may correspond to the transport distance of electrons released from the base metal.

- (b)

- The photothreshold representing the minimum photon energies needed to remove an electron from the surface of a material. But in this study the values were not estimated.

- (c)

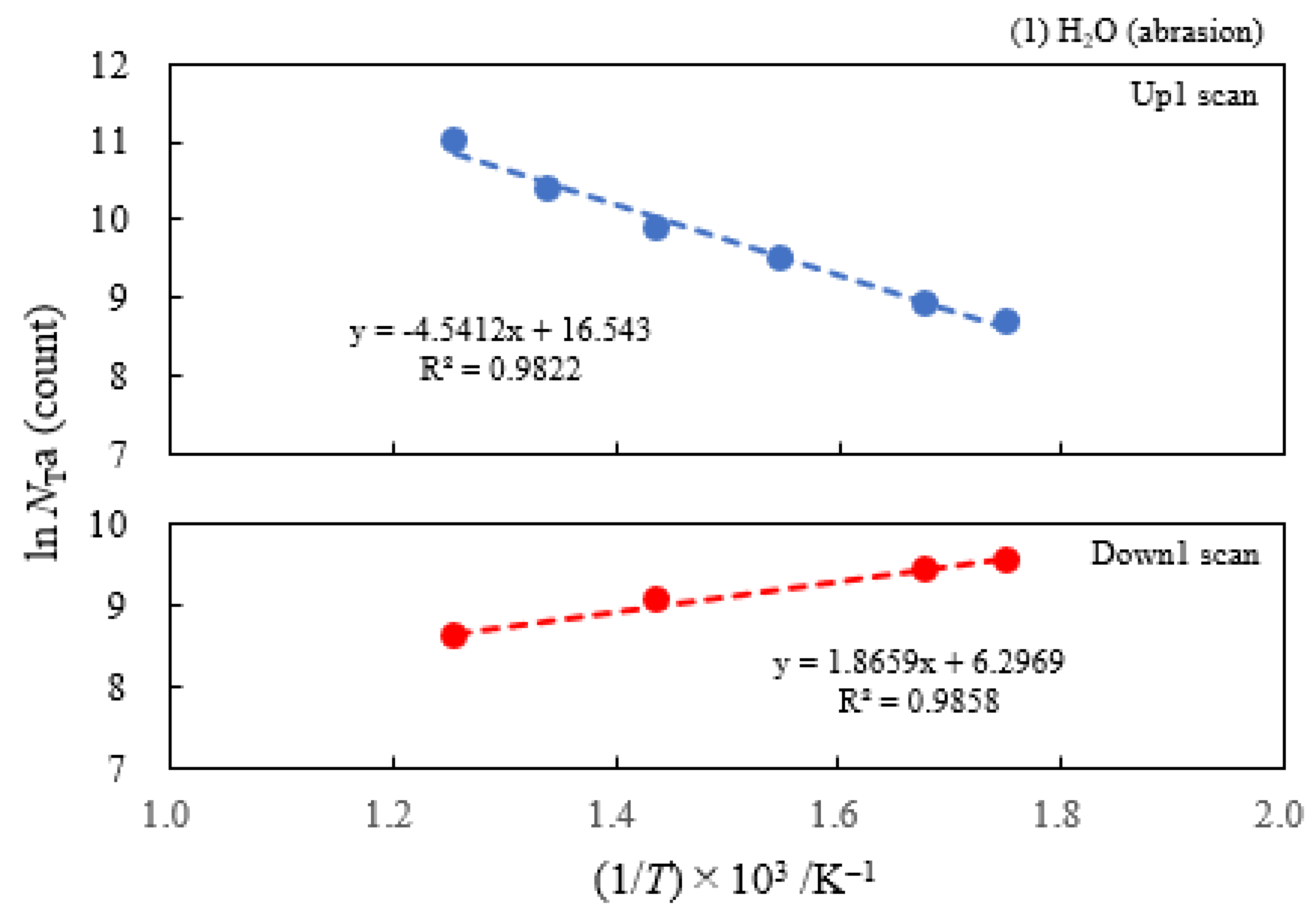

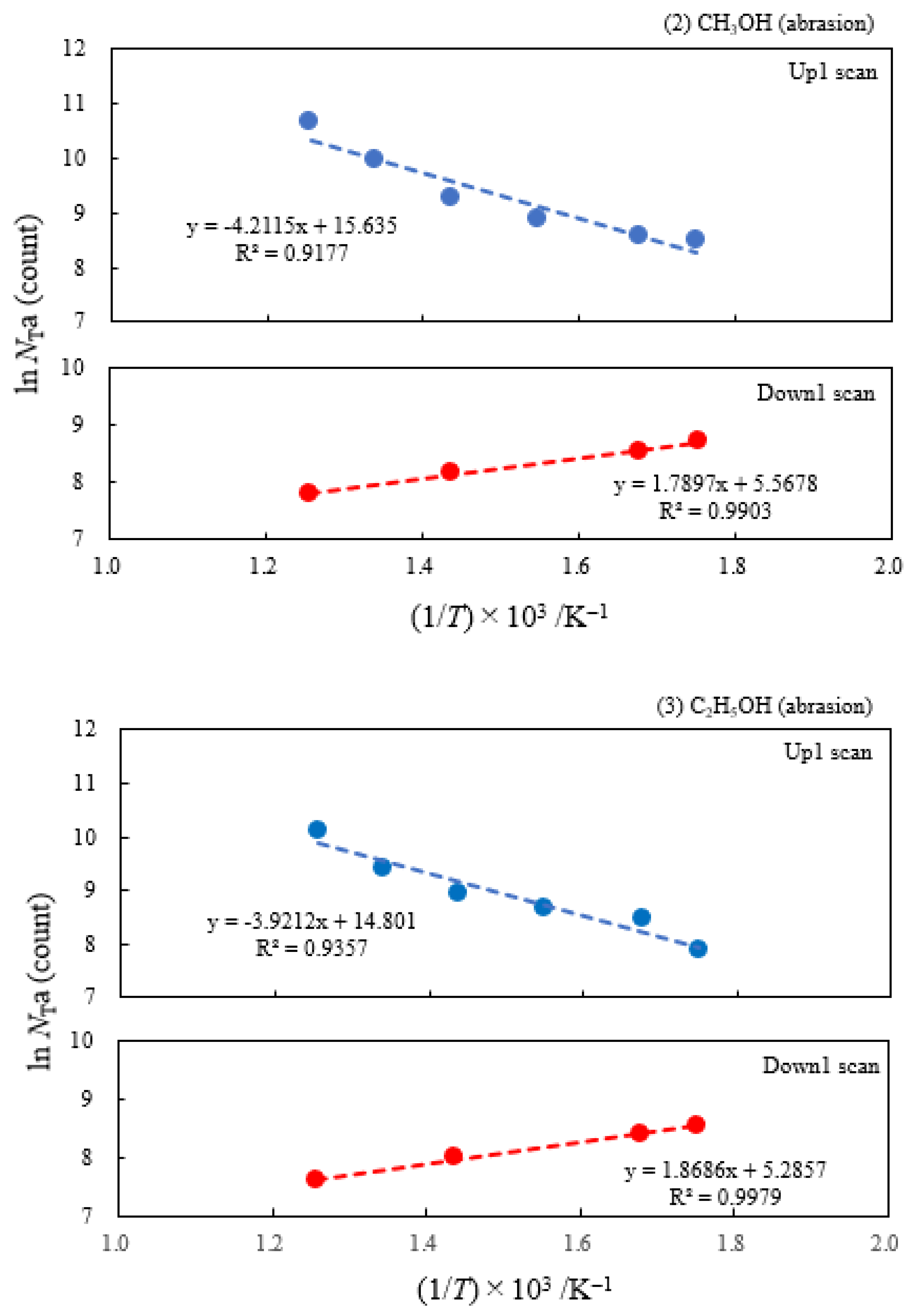

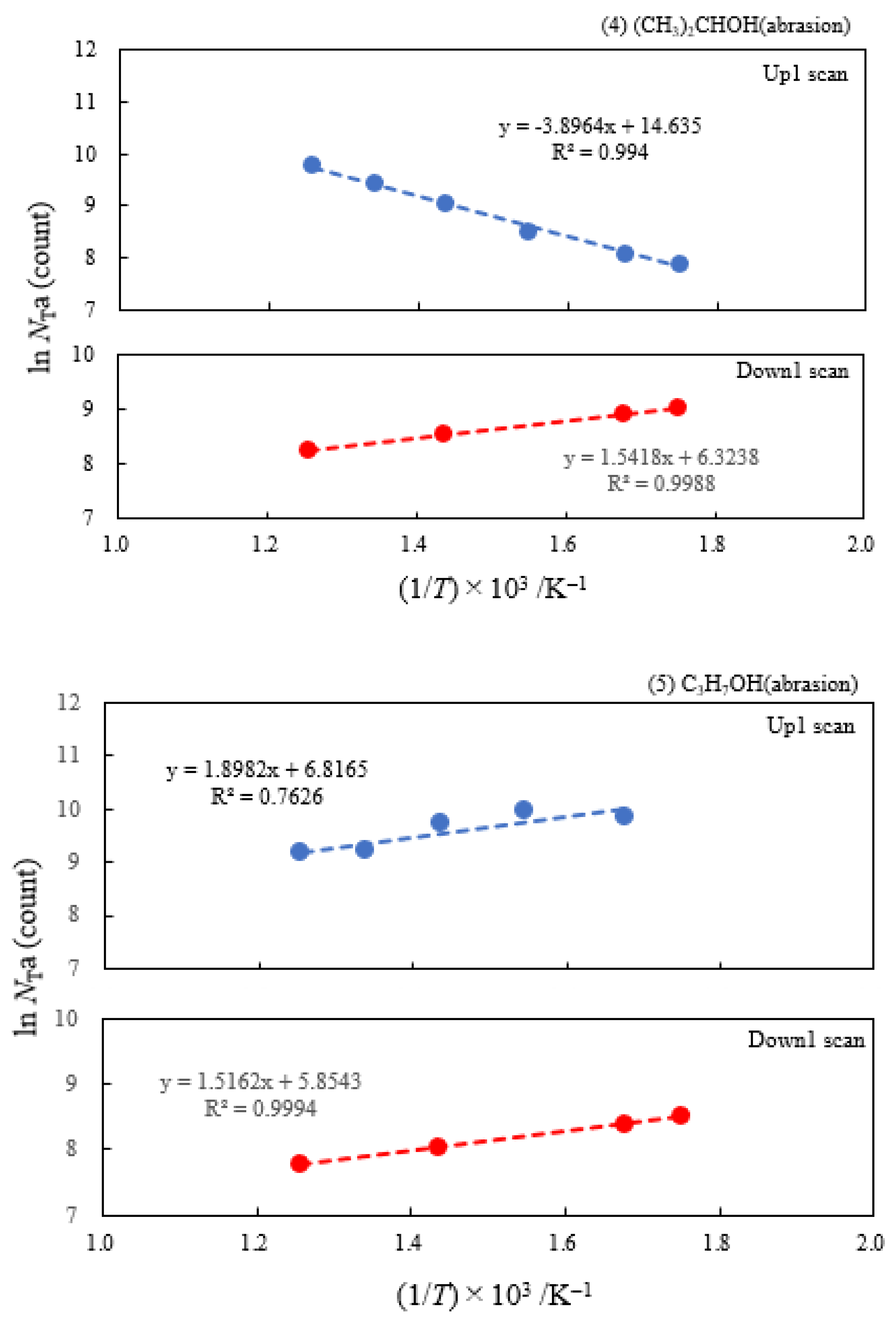

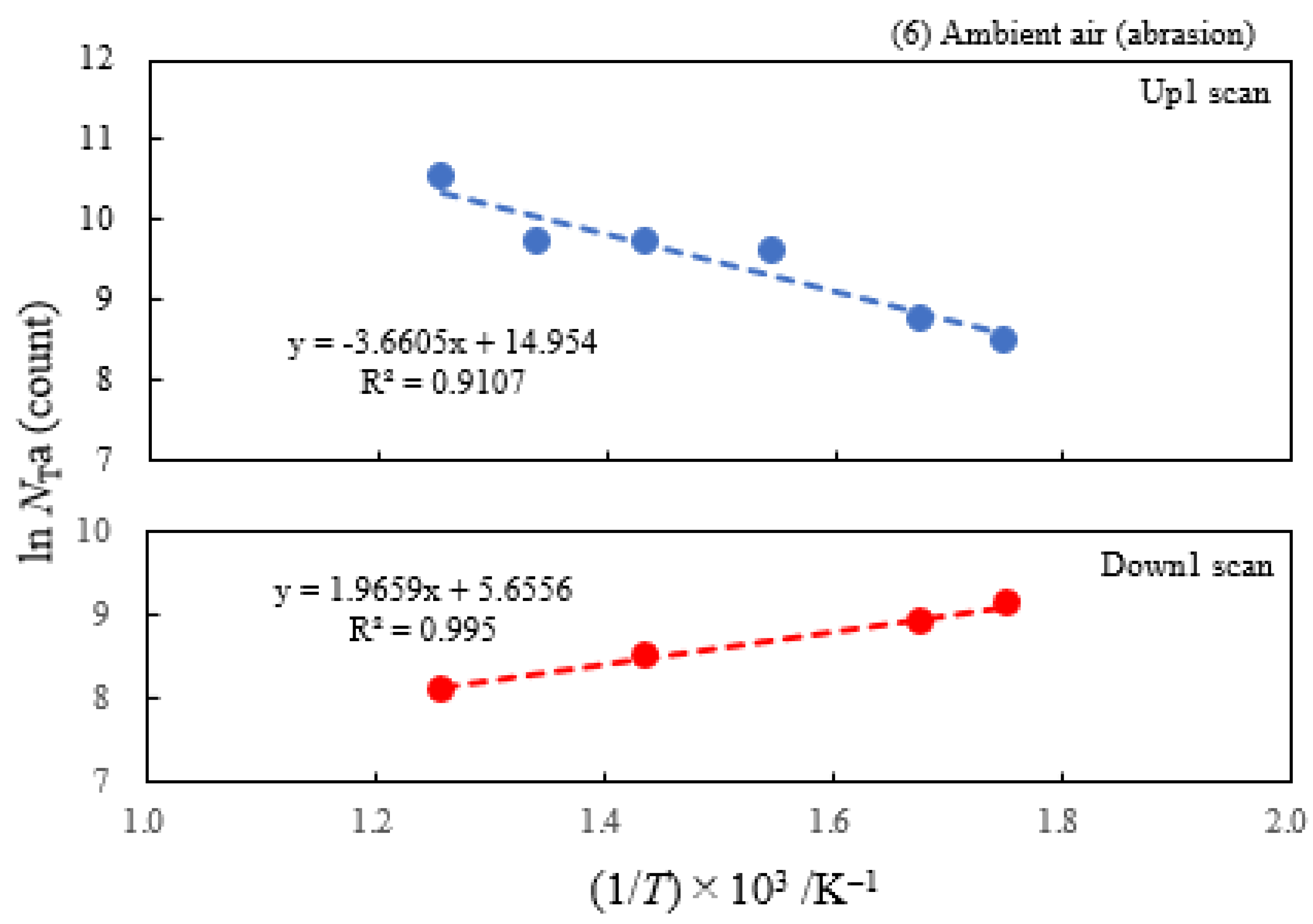

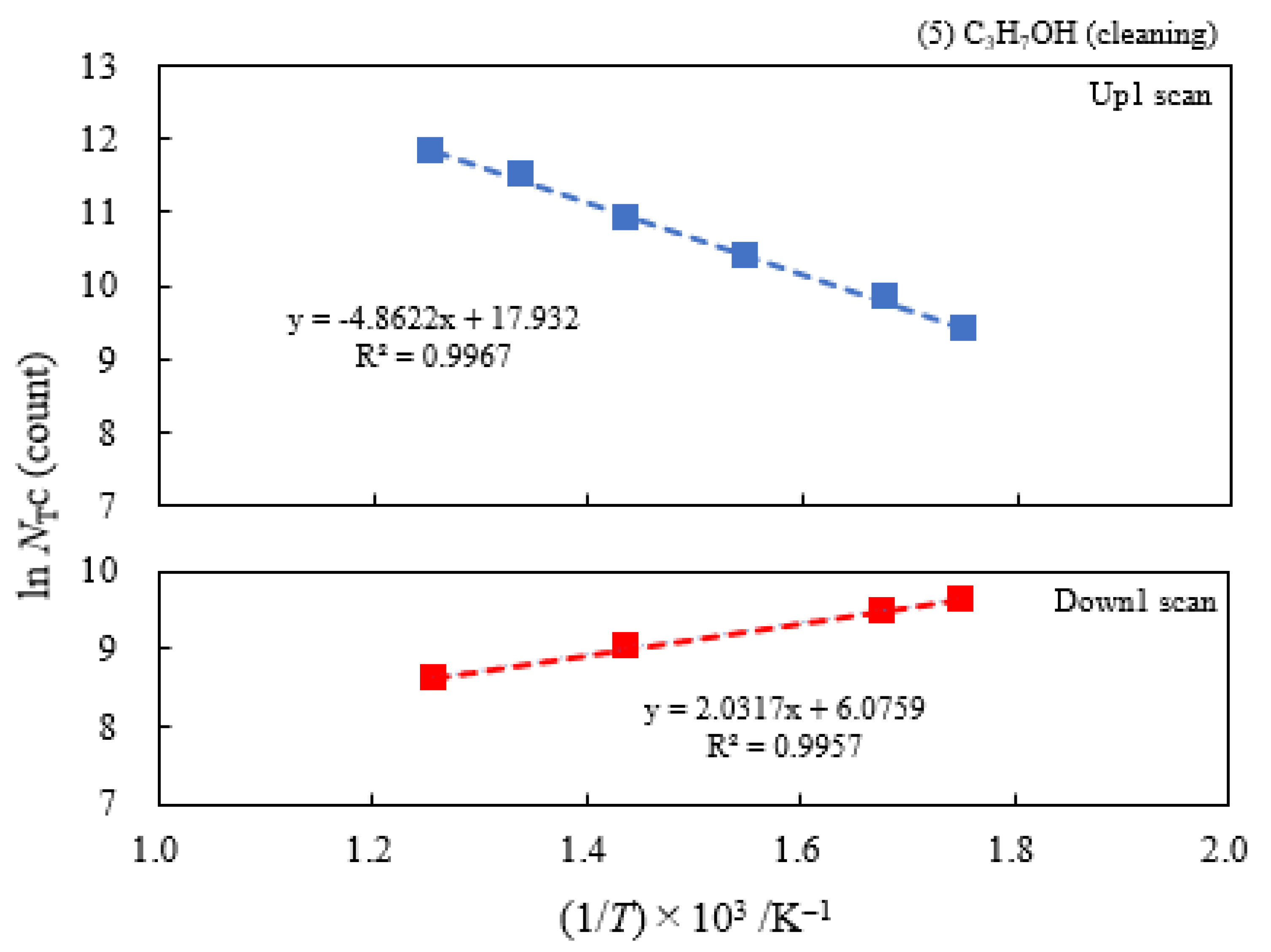

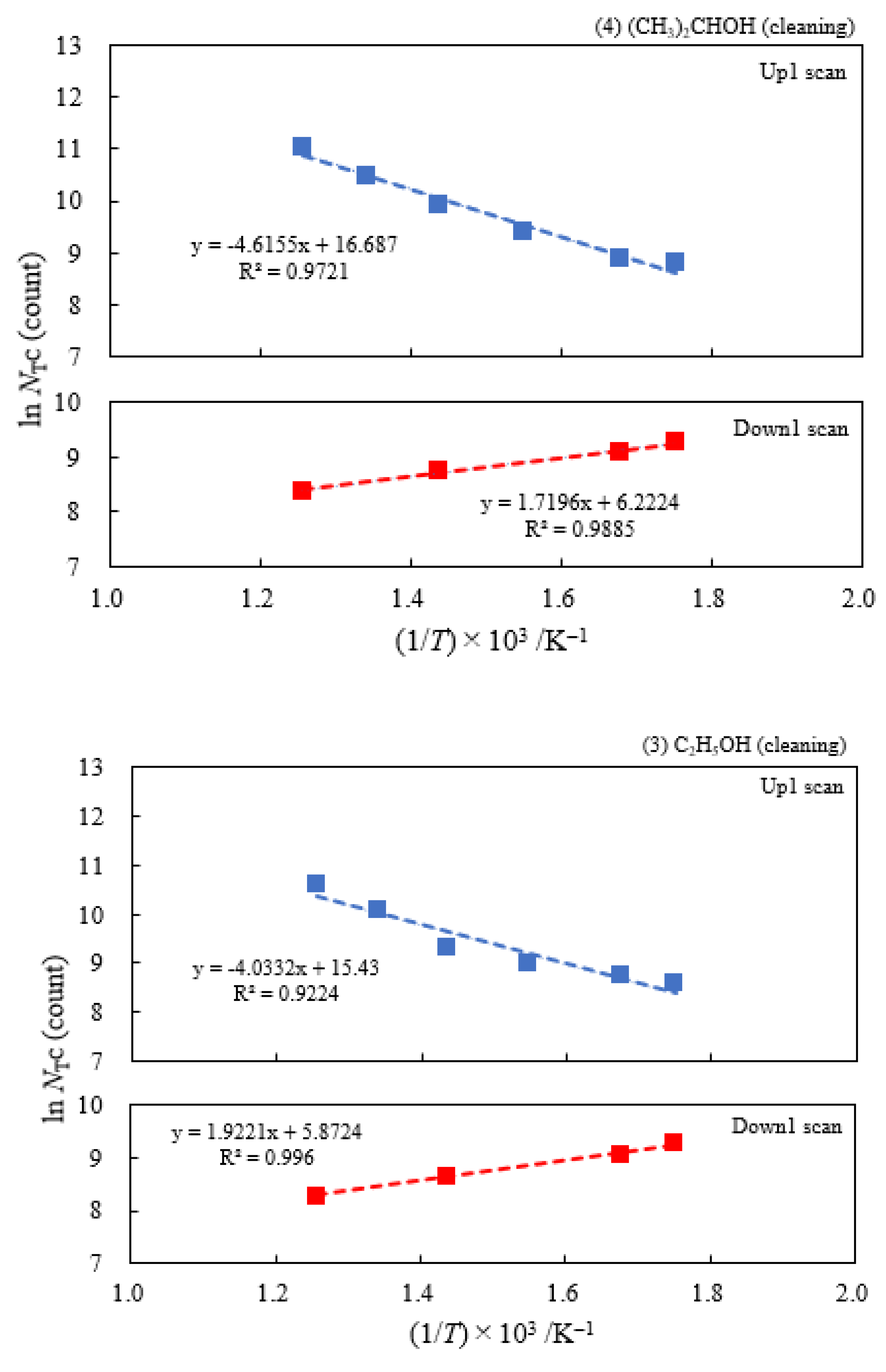

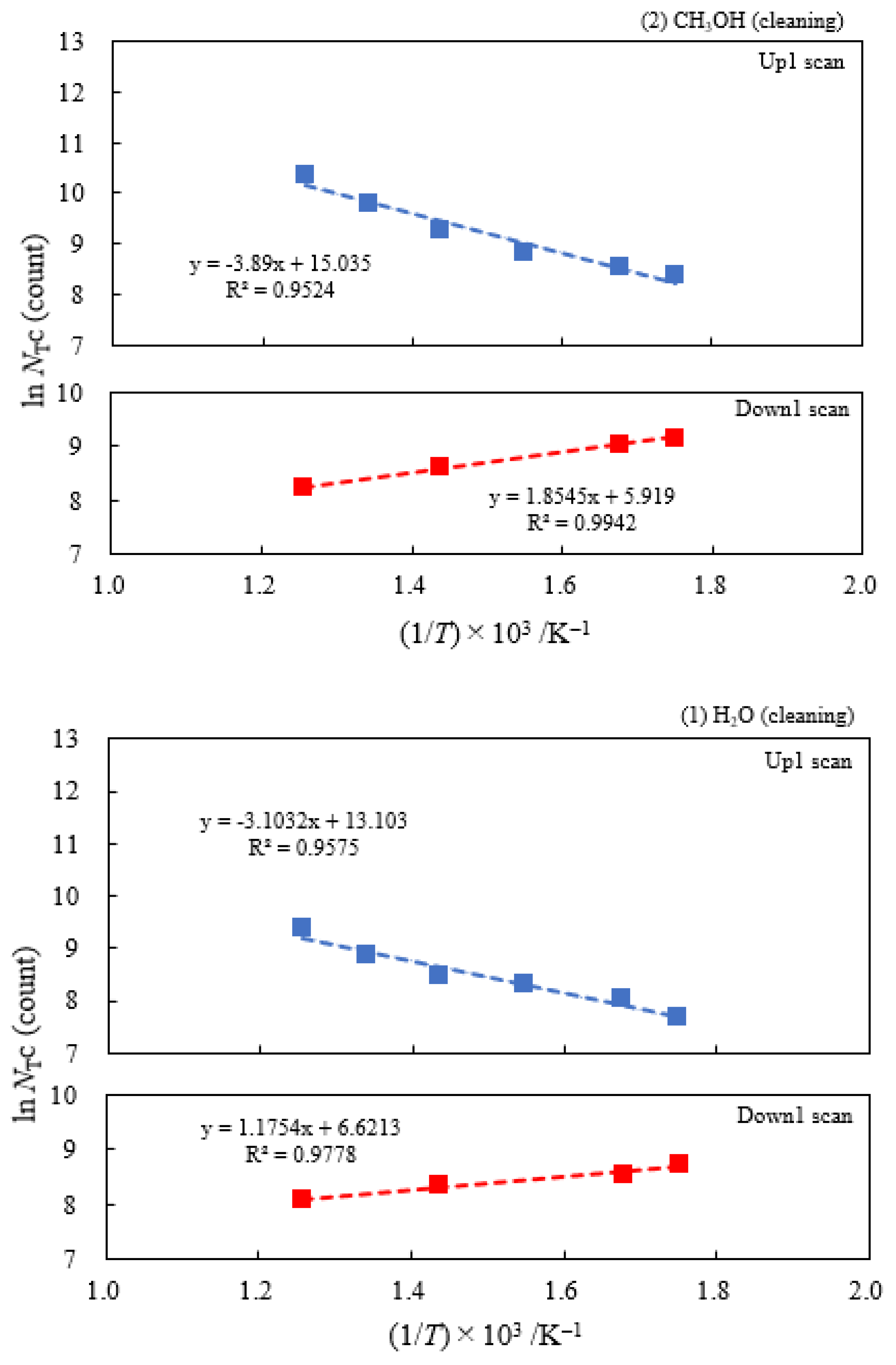

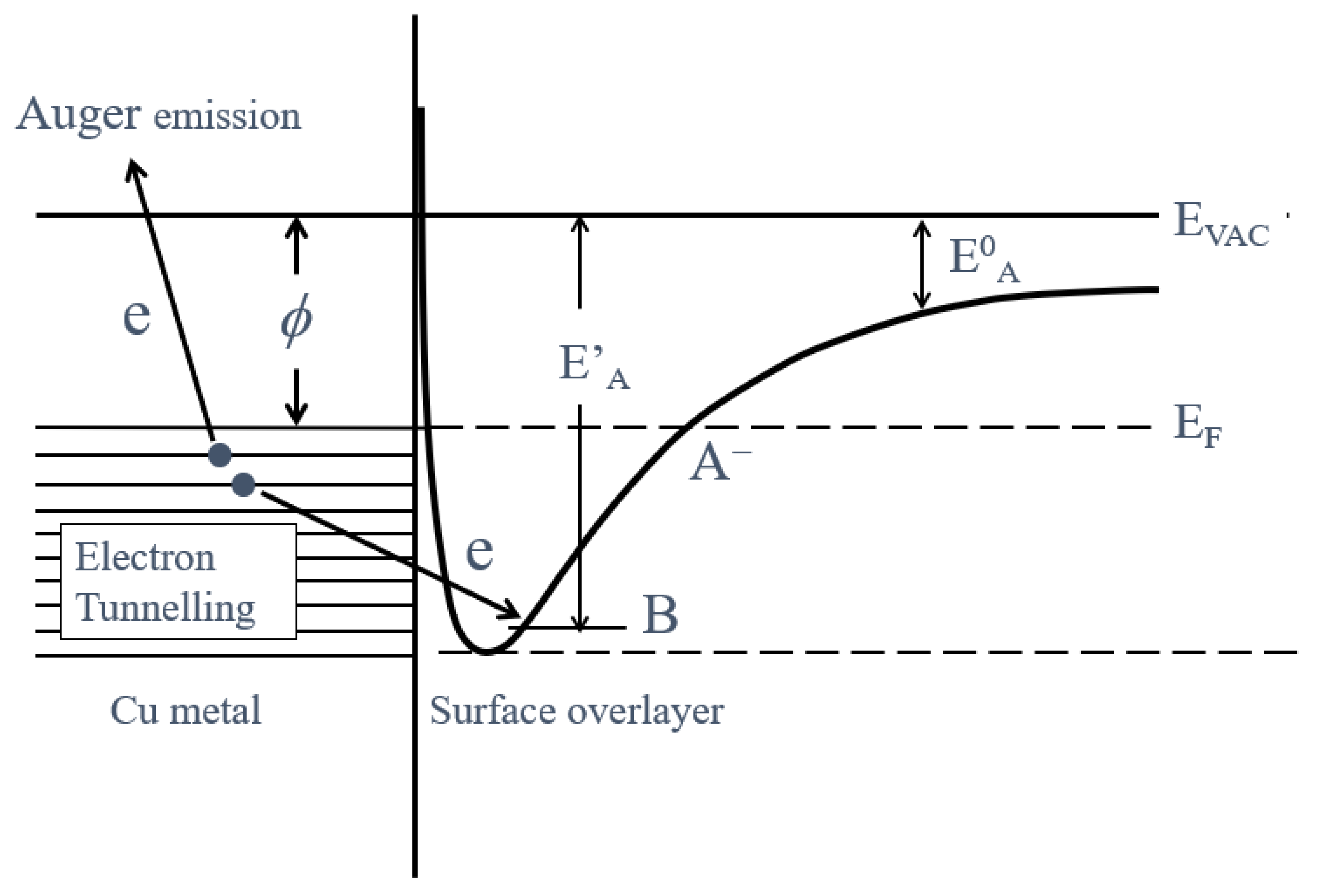

- The activation energies of NT for all Cu samples were obtained from Arrhenius type equation of NT = A0NT exp (−ΔE/kT), where A0NT indicates the pre-exponential factor, k Boltzmann factor, and T Kelvin). This expression was applied to NT values in the temperature-increase and subsequent temperature-decrease processes.

- (d)

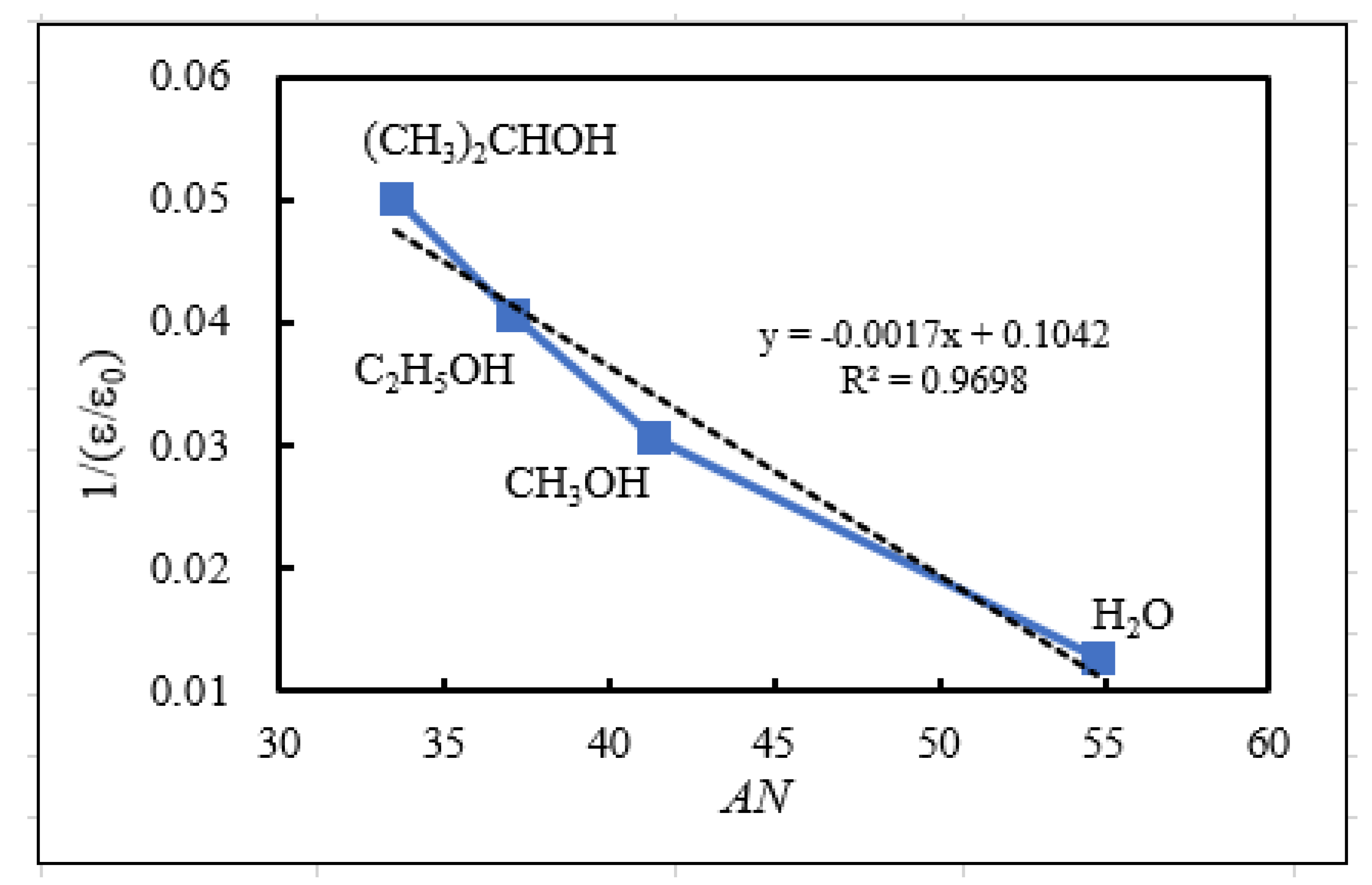

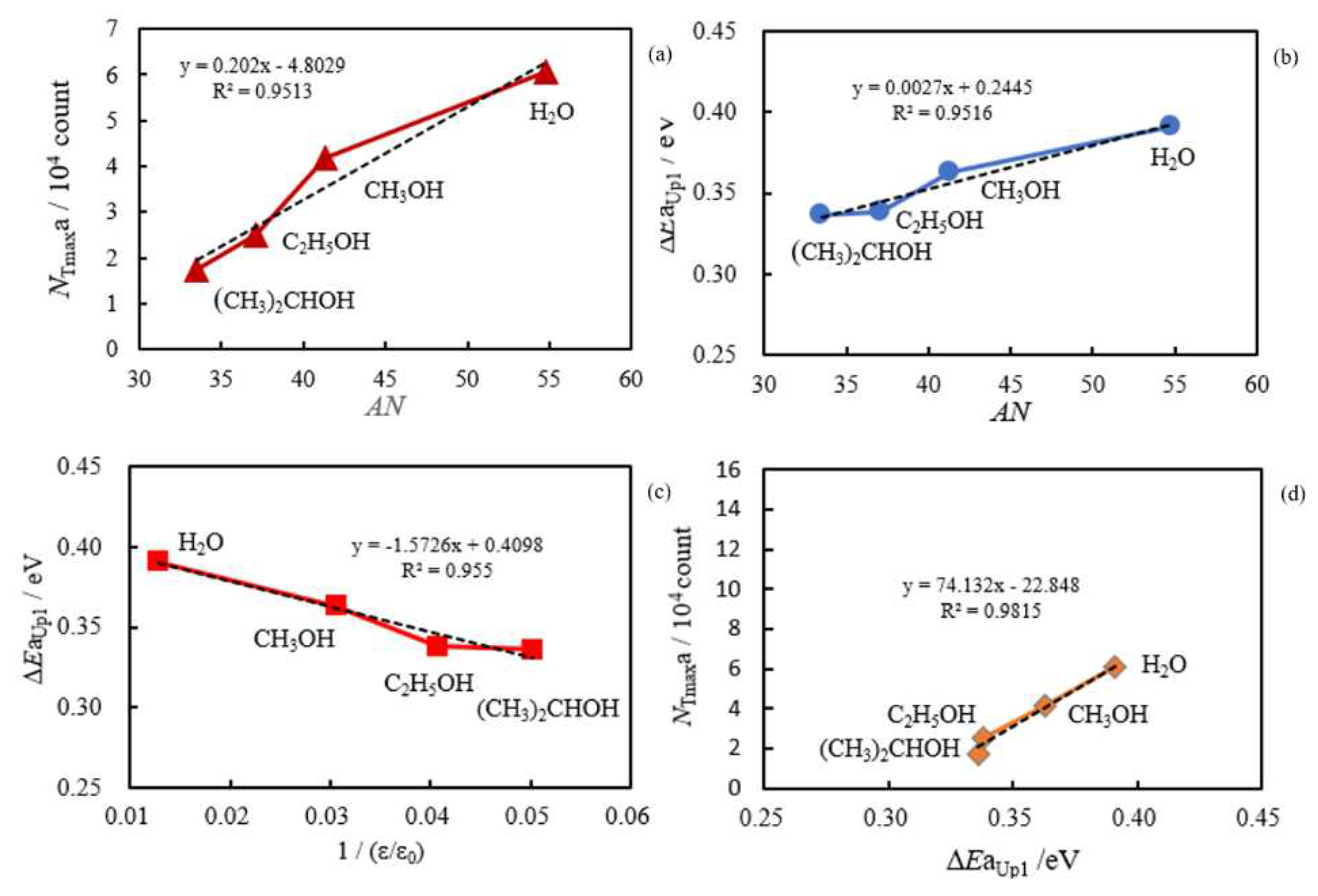

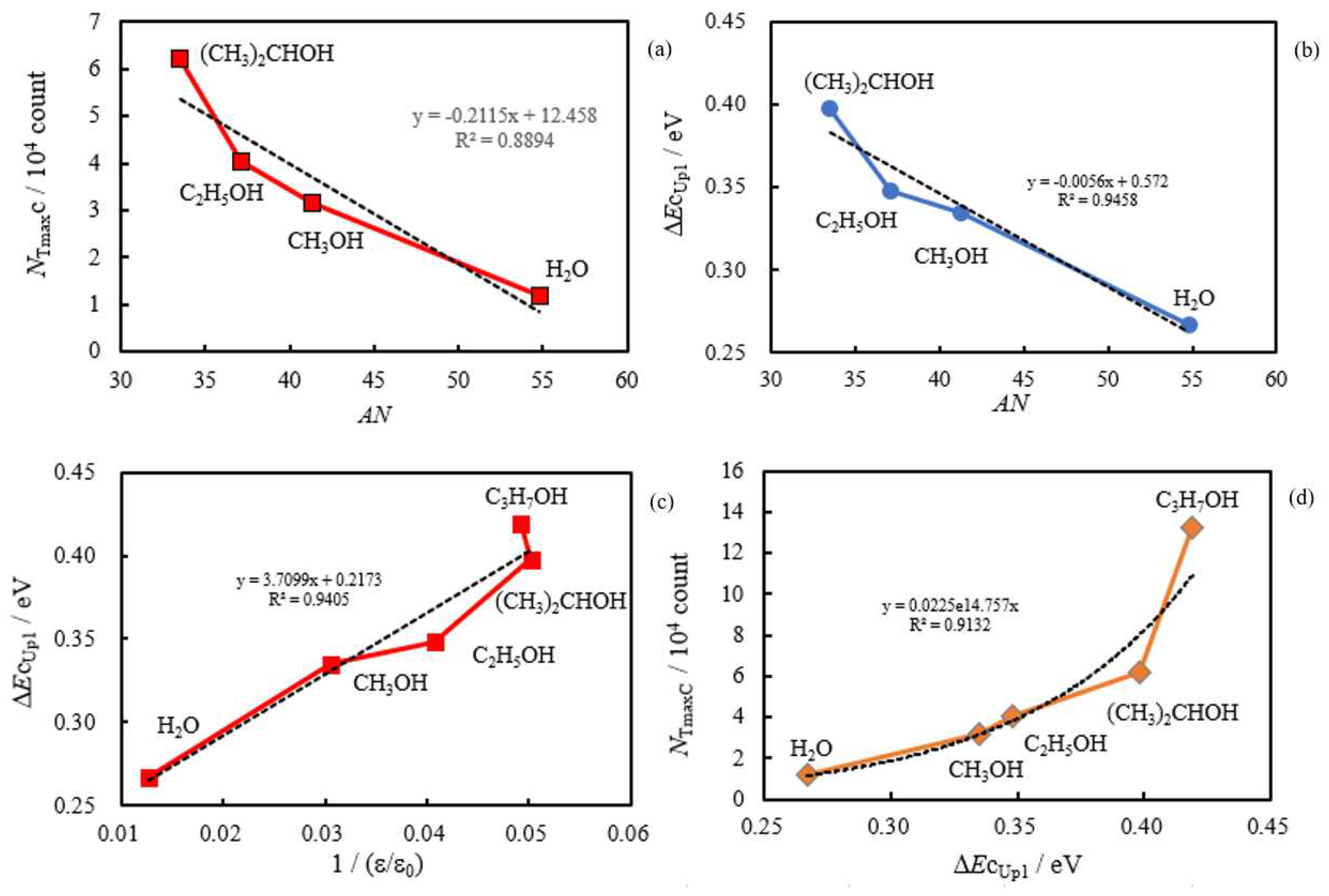

- The relation of activation energies of ΔEUp1 (Up1 indicates the 1st temperature increase process) to Gutmann’s acceptor number (AN) representing basicity and the reciprocal of dielectric constant (ε/ε0) of the used liquids is examined. Regarding contact killing of viruses by metals, the action of electrons accumulated in the neighborhood of the reaction cite is considered to be most essential according to ref. [1], because of the increase of the reducibility of the metal. As the electron emission mechanism will be described in detail later, electrons in the base metal are captured by hydroxyl group radicals adsorbed at the surface and then Auger emission occurs, giving rise to a PE stimulation spectrum. ΔE is considered to correspond to the trap depth of the hydroxyl group radical to attract electrons from the base metal. Further, we are interested in the relation of AN to 1/(ε/ε0) of the liquids, which represents the effect of the liquids to shield coulombic attractive force between positive and negative ions. It was found that the 1/(εε0) decreases with increasing AN for the liquids. The dependence of ΔE on 1/(ε/ε0) is clarified for the liquids.

- (3)

-

The relation of the TPPE to the XPS results is featured as follows:

- (a)

- Two components of O1s spectra: −OH (hydroxyl group) and O2−(oxide) are of great importance.

- (b)

- The increase of NT in PE stimulation spectra is confirmed to be strongly related to the increase of the intensity of −OH before the TPPE measurement. After the TPPE measurement only O2− component appears and the NT disappears. Although the detailed mechanism of the −OH group adsorbed at the surface is not clear, it is considered that it has the character of radical having the ability to attract electrons by tunnelling from the base metal, followed by Auger emission. The PE stimulation spectra appears as a result of the Auger emission. The ability for the hydroxyl group radical to attract electrons is influenced by the acid-base interaction between the −OH group and the liquids adsorbed around the −OH group, producing different ΔE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

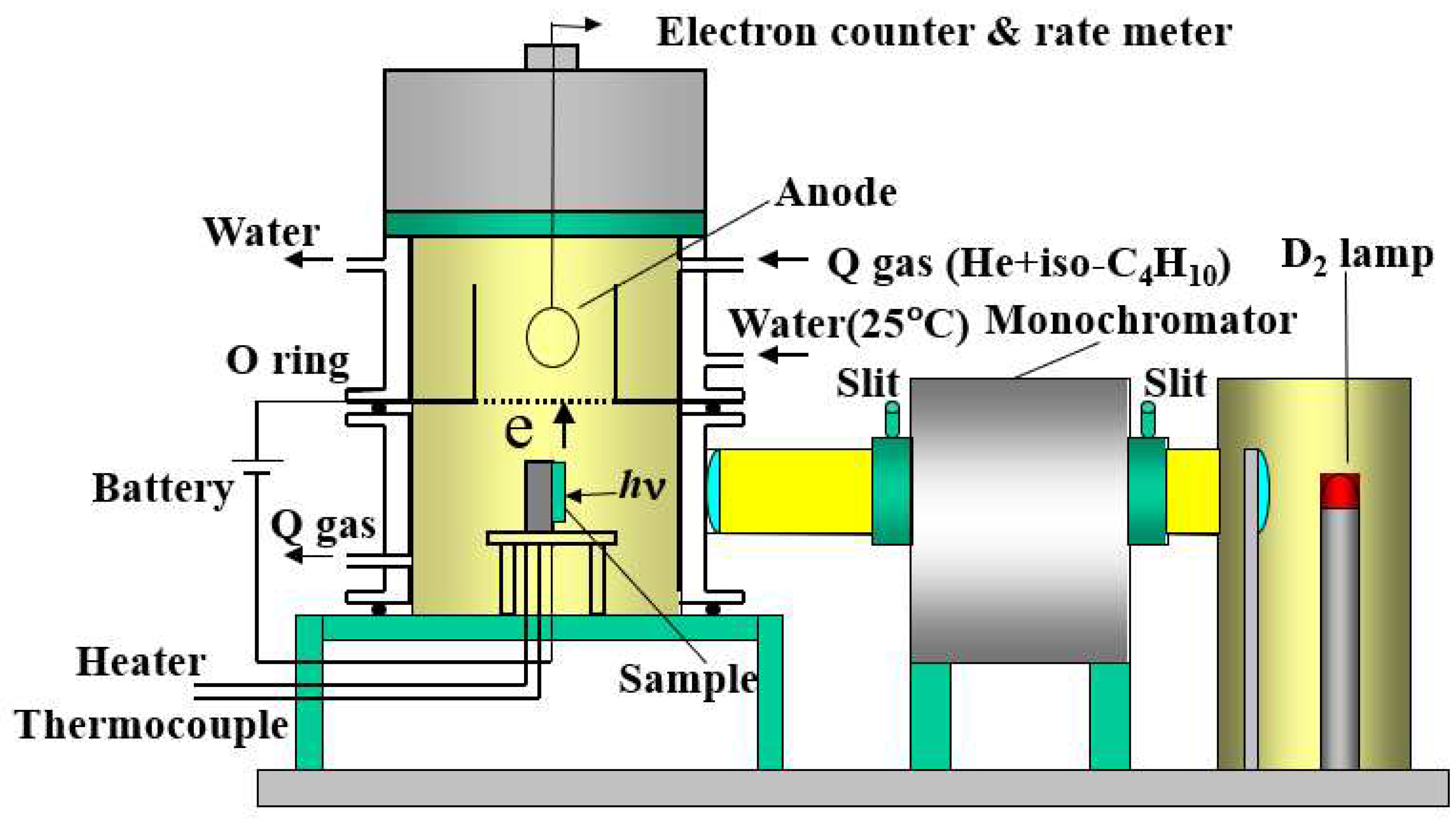

2.2 TPPE and XPS

3. Results and Discussion

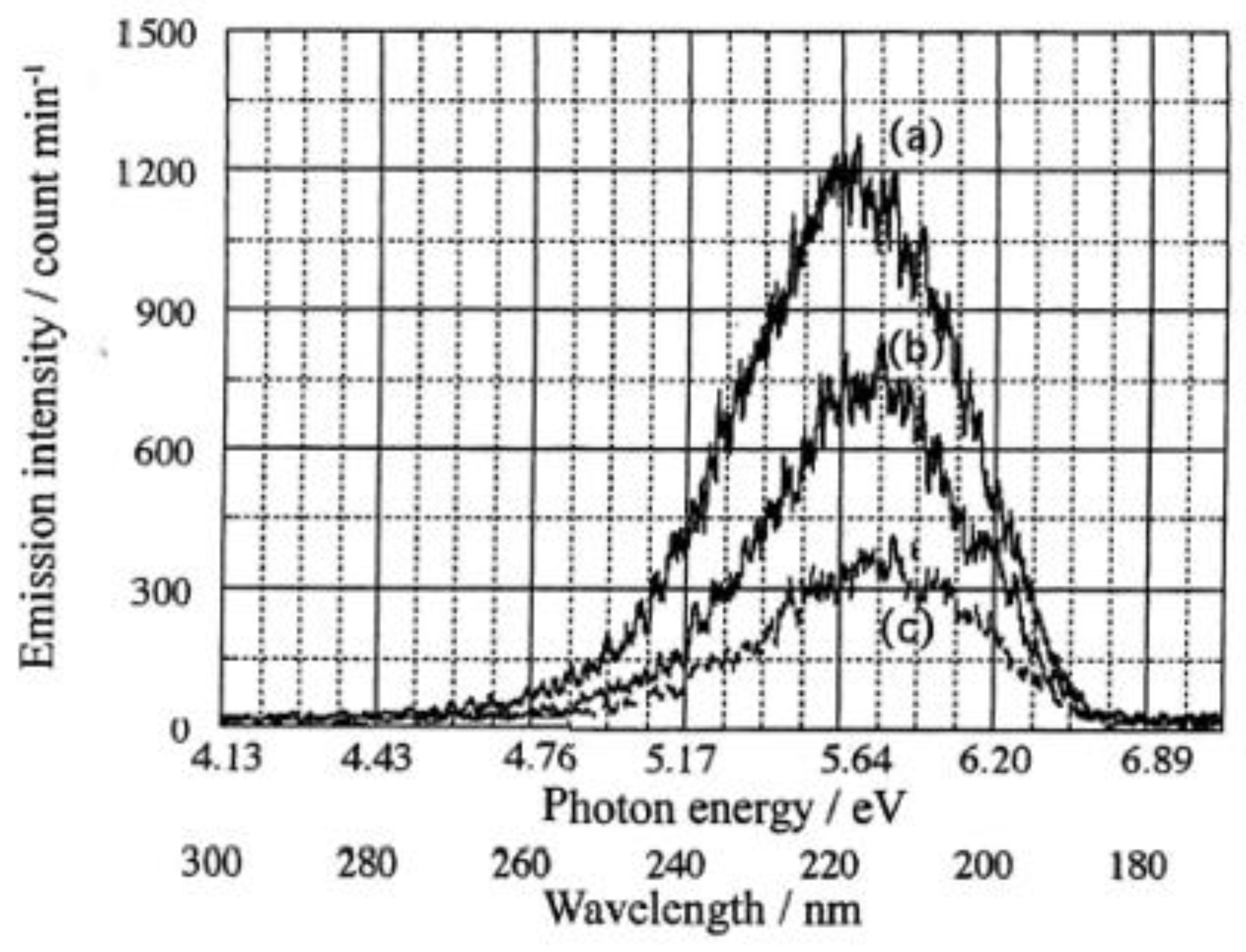

3.1. PE stimulation Spectra and TPPE Plot

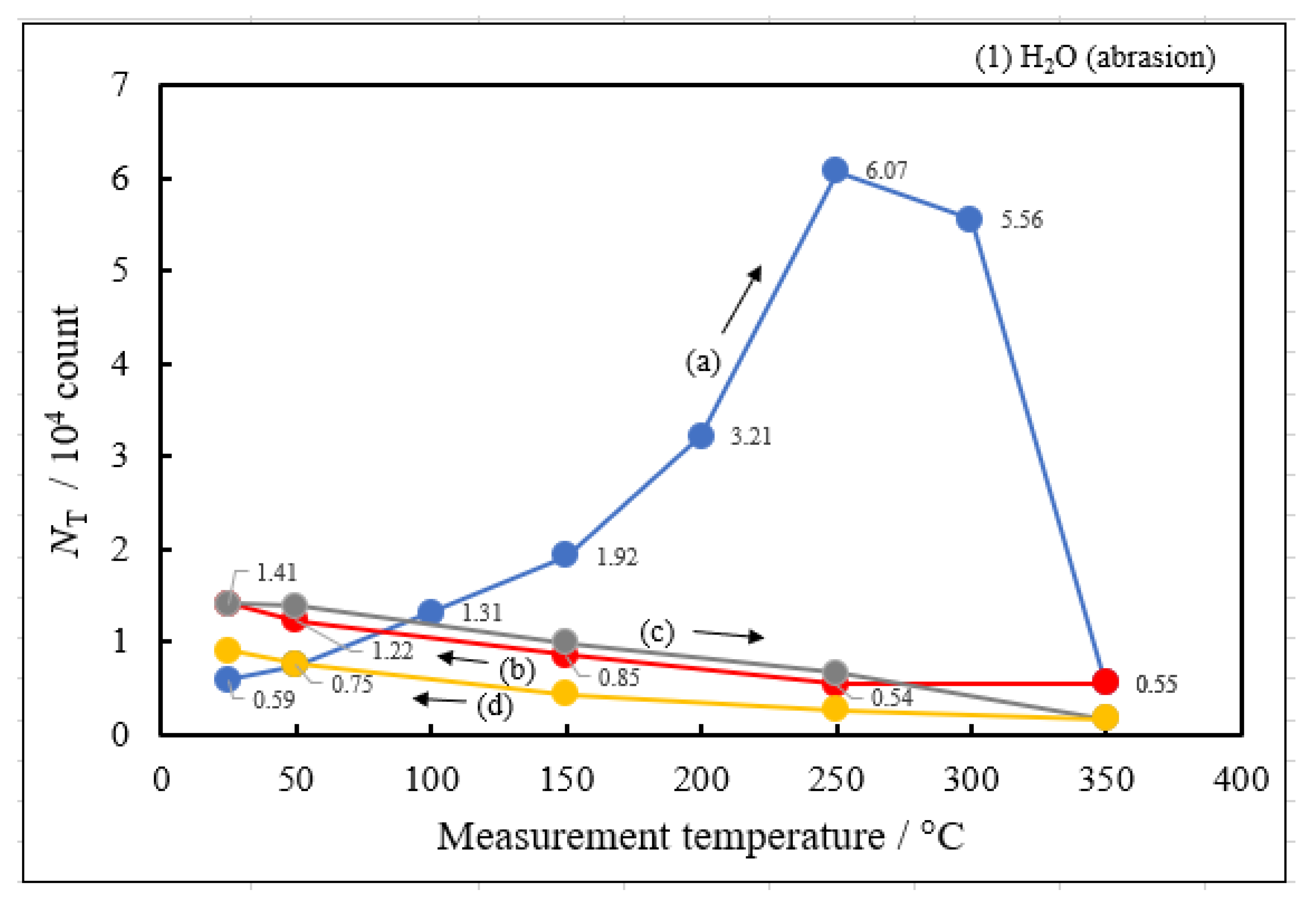

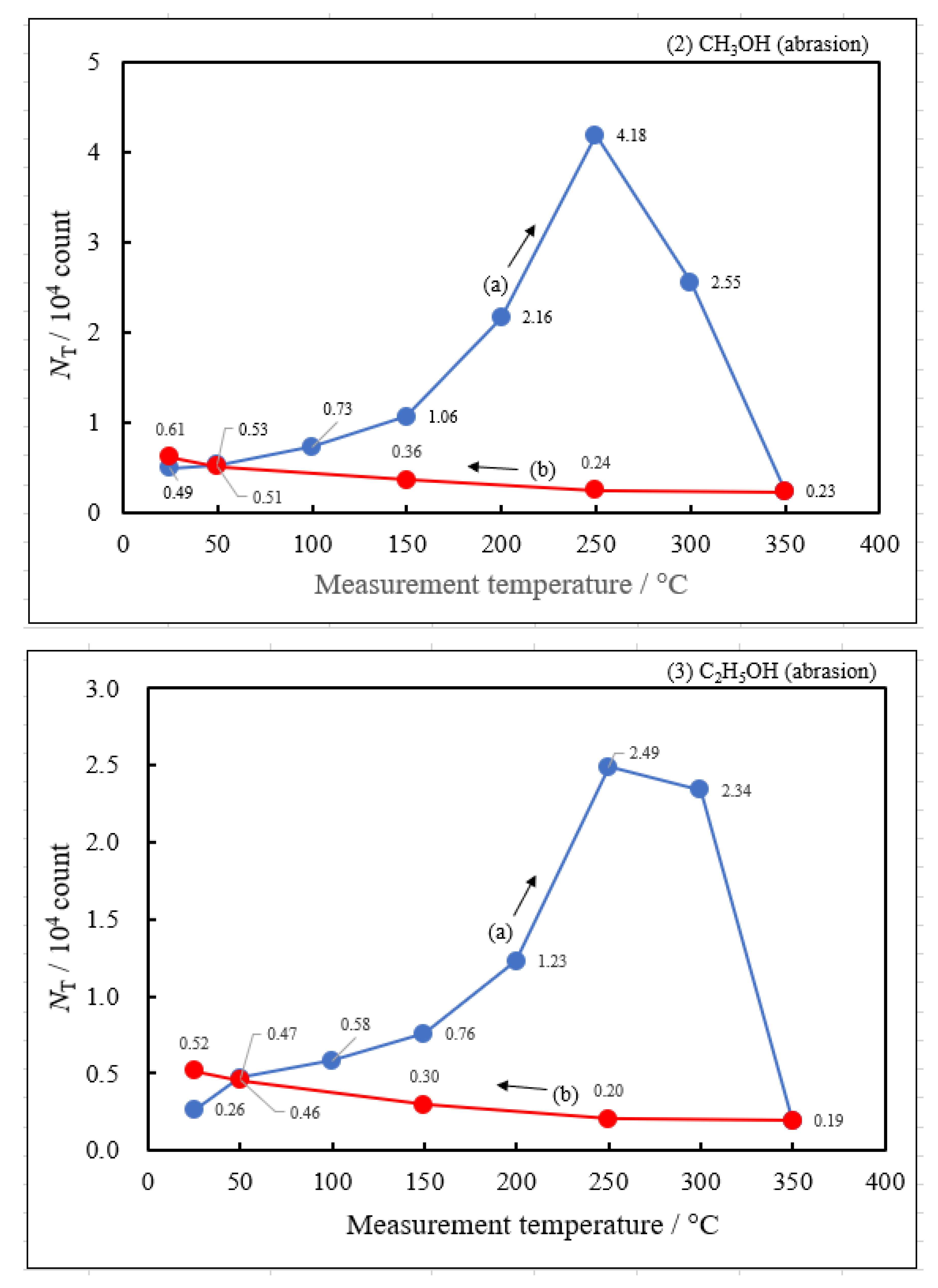

3.2. Dependence of TPPE Plots on Environments

3.3. XPS Spectra and XPS Characteristics

- (1)

- The atomic ratio of O1s/Cu2p for Cu ultrasonically cleaned alone in the liquids tended to decrease in the order H2O ≈ CH3OH > C2H5OH > (CH3)2CHOH ≈ C3H7OH. This may be related to the order of the amount of H2O being adsorbed on the surfaces after cleaning in each liquid because the adsorption of H2O most strongly decreases the NT as shown in Figure 5 (below). However, in the other cases there was little relation between the NT and the order of O1s/Cu2p and C1s/Cu2p.

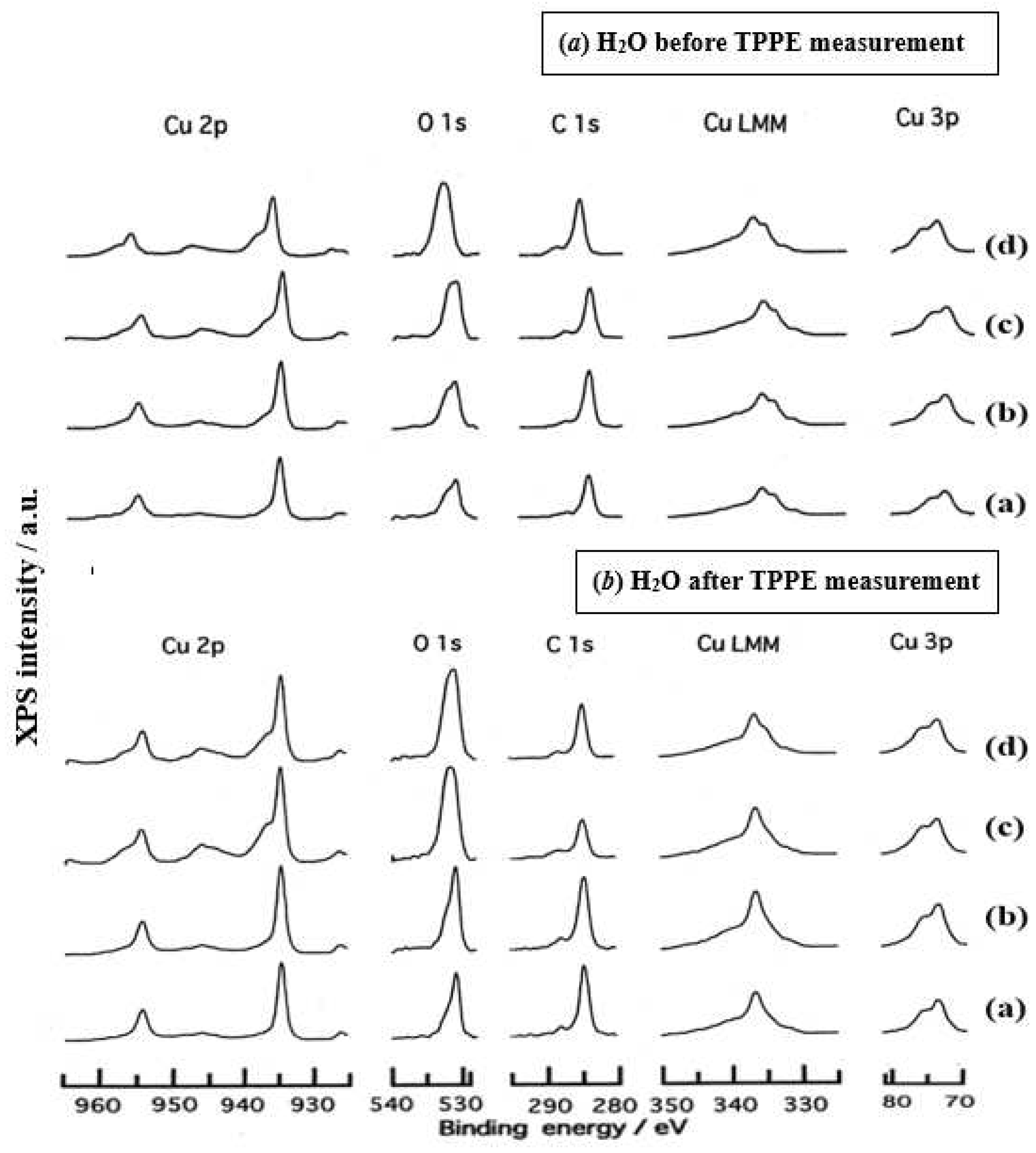

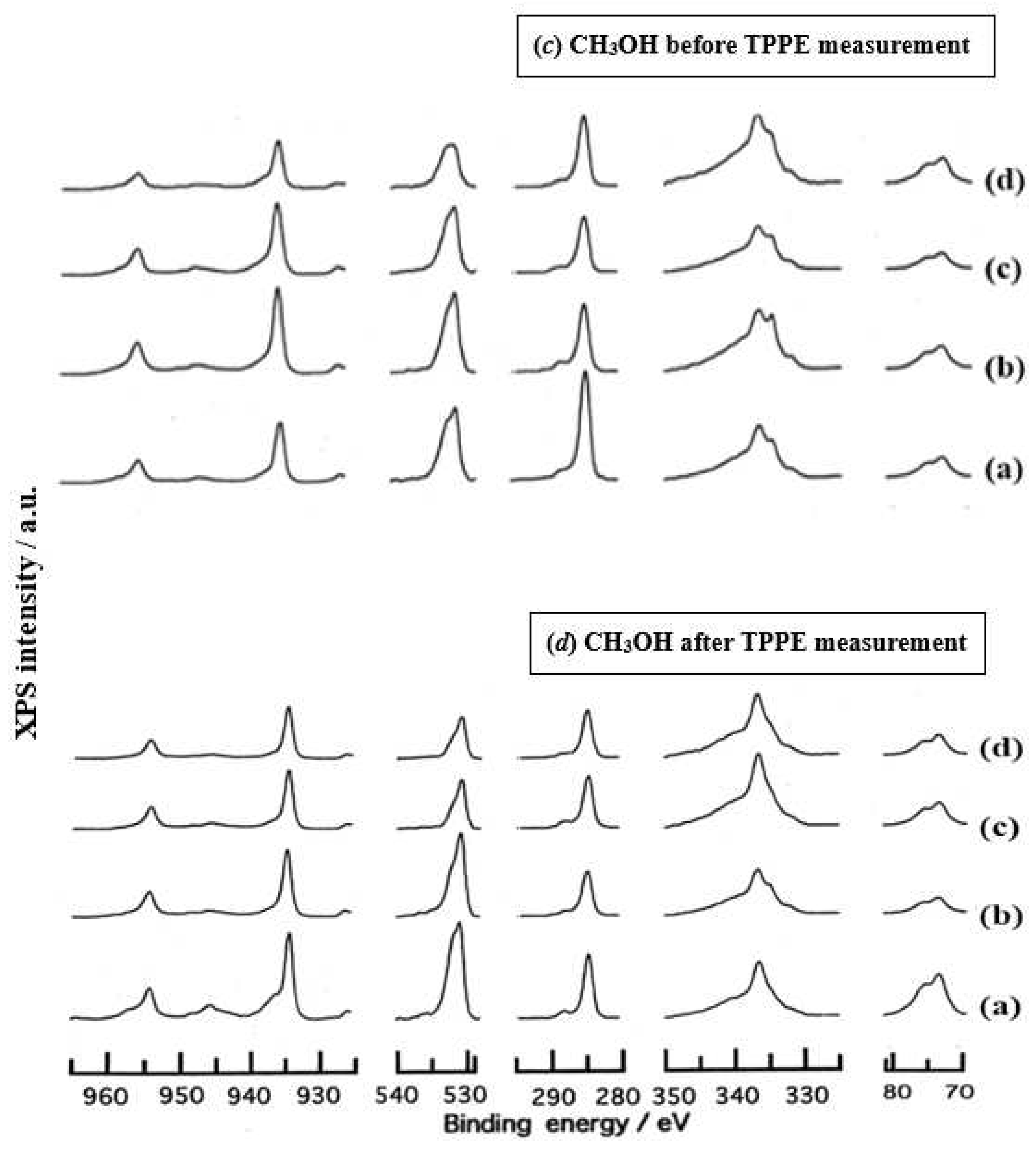

- (2)

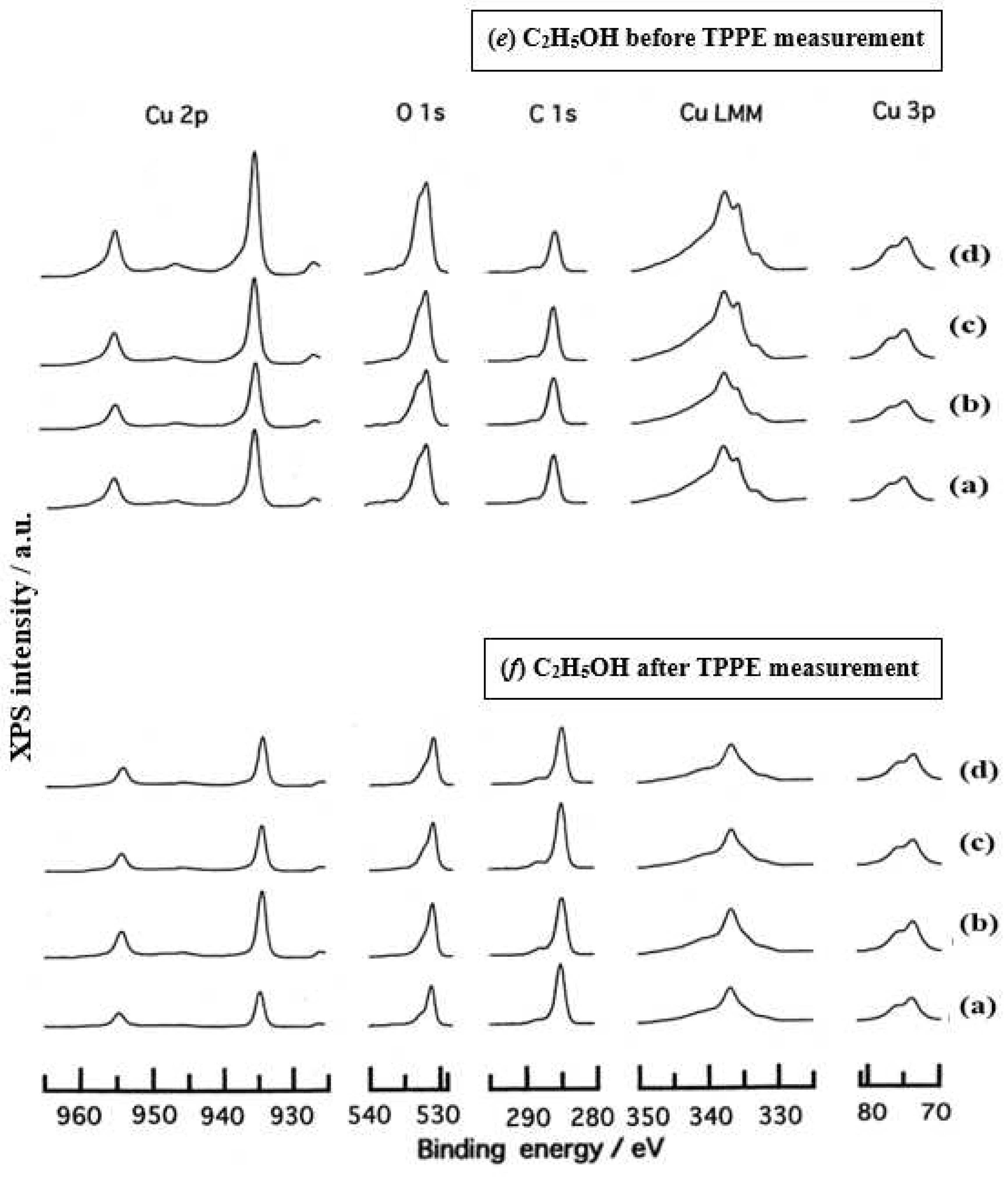

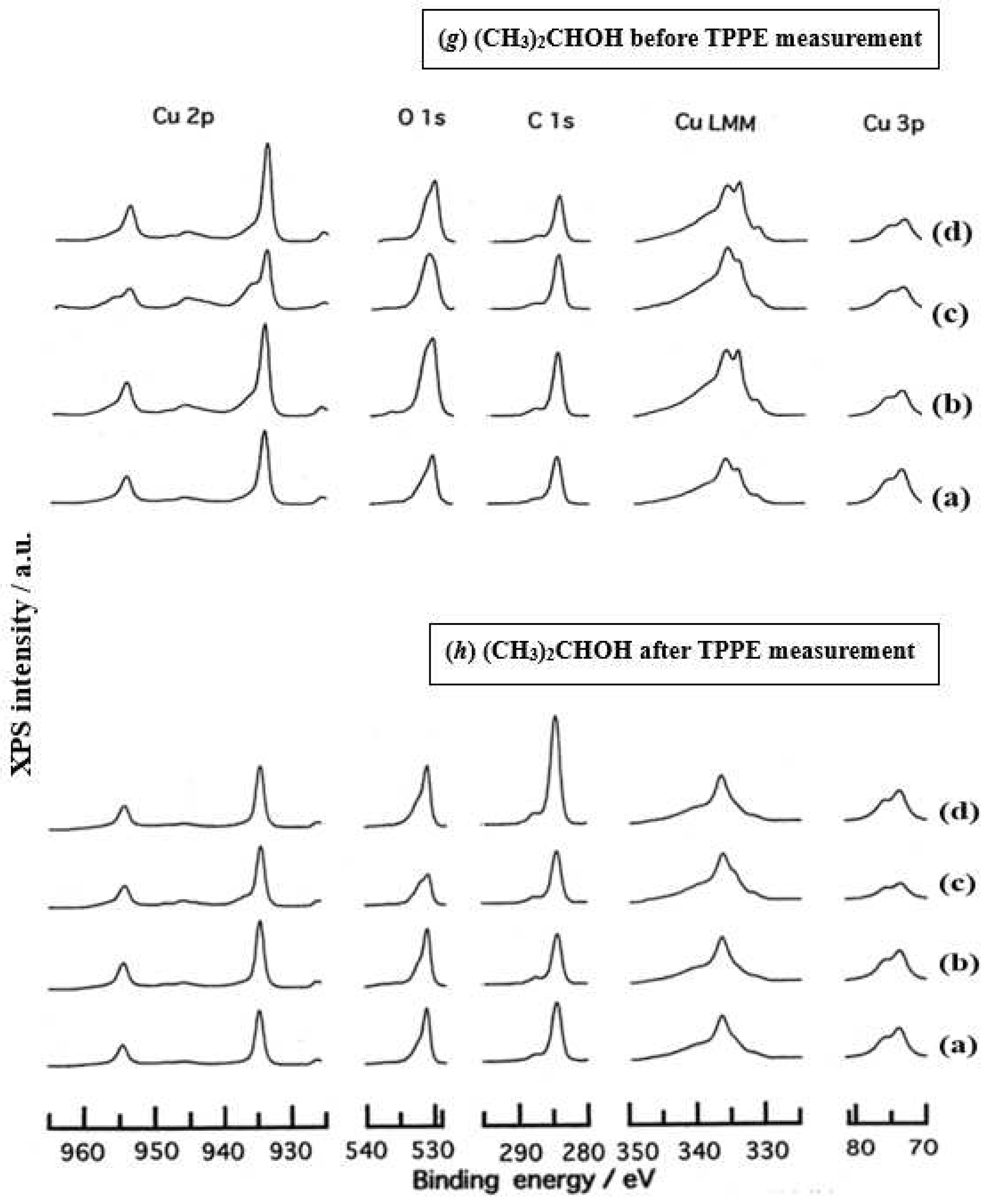

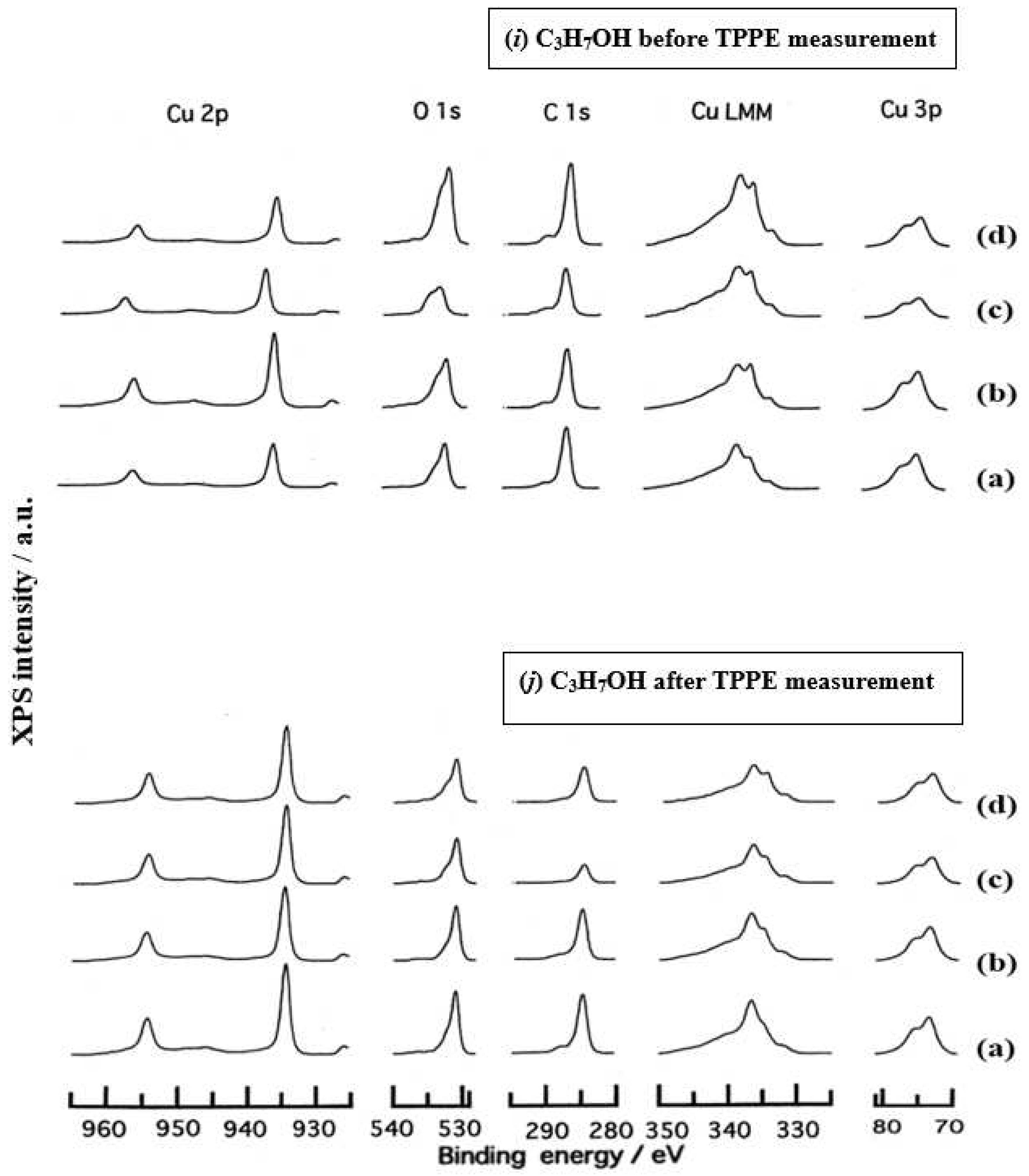

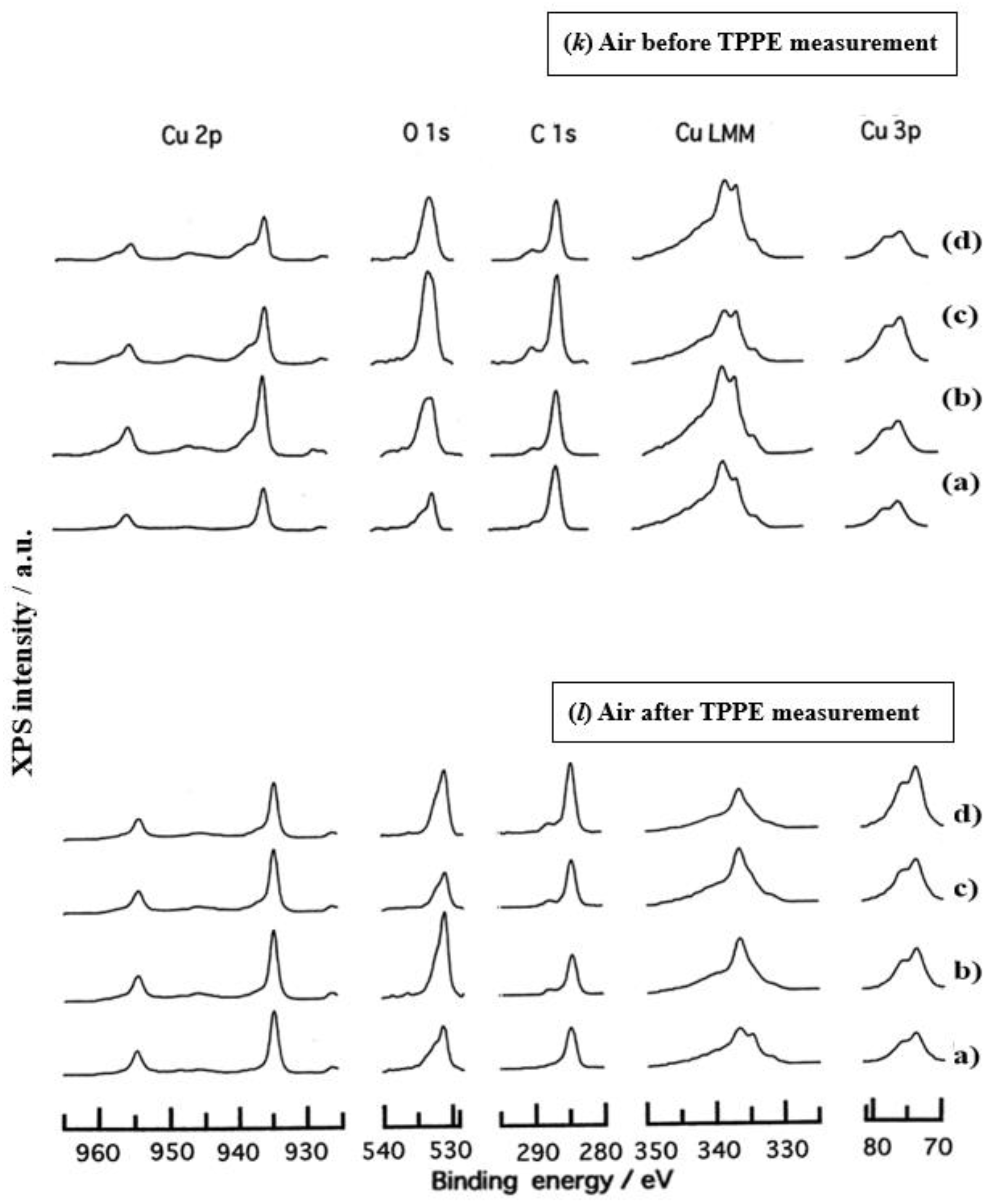

- The assignment of the XPS spectra before and after TPPE measurement in Figure 6 were conducted based on refs. [12,13,14,15] and our previous reports [7,9]. The assignment of the XPS spectra on copper and oxygen is summarized as follows. The binding energy for the oxidation state of Cu is known as follows: 932.5 eV (Cu0 and Cu+) and 933.5 eV(Cu2+) for Cu2p3/2; 335 eV (Cu0) and 337 eV (Cu+ and Cu2+) for CuLMM; a strong shake-up satellite structure 6−10 eV above the main Cu2p peak in Cu2+ compounds. Concerning the Ols peak, Evans [13] suggested that two components appearing at 529.9 eV and 532.5 eV for the oxygen chemisorbed copper can be assigned to oxygen bonded directly to copper and oxygen adsorbed onto the initial Cu-O structure, respectively. McIntyre et al. [14] also suggested that the oxygen component of higher binding energy component includes the species such as OH, Cu(OH)2, and H2O. Recently the XPS spectra of tarnished copper plates of phosphor bronze (C1220) (Cu purity: > 99.9 %) was reported [15]. The binding energies of the Cu2p, the satellite, and O1s peaks were given as follows: Cu (932.6 eV), Cu2O (932.7 eV), and CuO (933.1 eV) for the Cu2p peak; 943~948 eV (Cu2O) and 940~945 eV (CuO) for the satellite peak; 531.7 eV (Cu(OH)2), 530.7 eV (Cu2O), and 529.8 eV (CuO) for the O1s peak [15].

- (3)

- Regarding CuLMM for every sample abraded and ultrasonically cleaned before TPPE measurement in Figure 6, metallic Cu clearlyappeared at 335 eV, but after TPPE measurement the metallic Cu greatly diminished for almost all samples. This finding suggested that the appearance of the metallic component before the TPPE measurement may be related to the increase in the PE intensity, but the detail of the mechanism remained unclear.

- (4)

- For the O1s peak shown in Figure 6, two components of Cu(OH)2 and Cu2O appearing at higher and lower binding energies, respectively, were preferential, but CuO component was negligible. Regarding CuO, the reaction of Cu2O + (1/2)O2 → CuO is considered to be unlikely because of the lack of O2 in the present experiment. The two components were observed for every sample before TPPE measurement, but after TPPE measurement in almost all cases the lower binding energy component became more preferential than the higher binding component, although for samples of 10-min abrasion in H2O and ultrasonic cleaning in air both components were still preferential. This finding suggested that the change from the OH component (hydroxyl group) to the O2− component (oxide ion) partially occurred being accompanying with the desorption of H2O. Here, we suppose that this OH has a property of a radical, having the ability to attract electrons from the base metal by tunnelling followed by Auger emission, leading to the PE under light irradiation, although the mechanism of TPPE is not fully understood. We emphasize that this process becomes a key point in the increase in the TPPE intensity, as described later.

- (5)

- We examine to clarify how the Cu2p3/2 and the satellite peaks can be associated with the adsorption of oxygen. Here, the binding energies for the observed spectra are represented by actually measured values in the experiment. In Figure 6, for a sample of 10-min abrasion in H2O before TPPE measurement a sharp main Cu2p peak at 935 eV, which can be assigned to Cu and Cu2O, and a broad shoulder peak at 937 eV in the higher binding energy region of the main Cu2p peak, which may originate from Cu(OH)2, were observed, and the satellite peak was clearly observed at 940−948 eV, which may be originated from Cu(OH)2 because the satellite grew with the increase in the shoulder peak. On the other hand, for a sample of ultrasonic cleaning in H2O before TPPE measurement in Figure 6, the sharp main peak was observed, but the satellite peak was very small. Similar behavior was observed for samples abraded in (CH3)2CHOH and air before TPPE measurement. In the case of samples abraded and ultrasonically cleaned in H2O, (CH3)2CHOH, and air after TPPE measurement the satellite peak was very small except samples abraded in H2O and ultrasonically cleaned in CH3OH. For both types of samples abraded and ultrasonically cleaned in C2H5OH and C3H7OH before and after TPPE measurement the satellite peak was almost negligible. This finding may suggest that the TPPE observed for C2H5OH and C3H7OH has little relation to the Cu(OH)2 component as the source of the satellite appearing in Cu2p peak. Finally, it is considered that the chemical structure of the metal surfaces before TPPE measurement is composed of adsorbate (alcohols, H2O, air)/Cu(OH)2/Cu2O/metallic Cu.

3.4. TPPE Characteristics for Sample A and Sample C and Their Relation to the Properties of Liquids

3.5. TPPE Mechanism and Its Relation to Activation Energy

3.6. TPPE in the Down1, Up2, and Down2 Scan Processes and Activation Energy

Acknowledgments

References

- Tian, H; He, B.; Yin, Y.; Liu, L.; Shi, J.; Hu, L.; Jiang, G. Chemical nature of metals and metal-based materials in inactivation of viruses. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(14), 2345. [CrossRef]

- Grass, G.; Rensing, C.; Solioz, M. Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77(5): 1541–1547. [CrossRef]

- Scully, J. R. The COVID-19 Pandemic, Part 1: Can antimicrobial copper-based alloys help suppress infectious transmission of viruses originating from human contact with high-touch surfaces? Corrosion, 2020, 76 (6): 523–527. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, S; Notoya, T.; Osakai, T. Highly selective determination of copper corrosion products by voltammetric reduction in a strongly alkaline electrode. Anal. Sci. 2012, 28, 323-331. [CrossRef]

- Momose, Y.; Kohno, S; Honma, M.; Kamosawa, T. Temperature programmed photoelectron emission analysis of copper surfaces subjected to cleaning and abrasion in organic liquids. Proc. 2nd International conference in processing materials for properties (TMS, Warrendale, Pa. 2000) pp. 285-290.

- Momose, Y. Exoemission from processed solid surfaces and gas adsorption. Springer Series in Surface Sciences, Vol. 73. (Springer, 2023), pp.210-213. [CrossRef]

- Terunuma, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Yoshizawa, T.; Momose, Y. Temperature dependence of the photoelectron emission from intentionally oxidized copper," Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 115, 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Terunuma, Y.; Honma, M.; Takahashi, K.; Momose, Y. Photoelectron emission from copper freshly abraded in organic liquids, J. Surf. Finishing Soc. Jpn. 1996, 47, 1075-1081. (in Japanese). [CrossRef]

- Momose, Y.; Honma, M.; Kamosawa, T. Temperature-programmed photoelectron emission technique for metal surface analysis. Surf. lnterface Anal. 2000, 30, 364-367. [CrossRef]

- Kamosawa, T.; Honma, M.; Momose, Y. Observation of real metal surfaces by temperature programmed photoelectron emission technique-temperature dependence of the amount of emitted electrons and its relationship to XPS analysis-, J. Sur. Einishing Soc. Jpn. 2000, 51, 836-843 (in Japanese). [CrossRef]

- Momose, Y.; Sato, K.; Ohno, O. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 at copper electrodes and its relationship to the metal surface characteristics. Surf. lnterface Anal. 2002, 34, 615-618. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C. D. et al. Handbook of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. 1979, Eden Prairie MN, Perkin-Elmer.

- Evans, S. Oxidation of the group IB metals studied by X-ray and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Chem Soc. Faraday Trans. II, 1975, 71, 1044-1057. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N. S.; Sunder, S.; Shoesmith, D. W.; Stanchell, F. W. Chemical information from XPS-applications to the analysis of electrode surfaces. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 1981, 18 (3), 714-721. [CrossRef]

- Morohashi, H.; Shibuya, K.; Amaki, Y. Surface analysis of tarnished copper plate, Report of the Industrial Research Institute of NIIGATA Prefecture, 2021, No.50 2020, pp. 68-71.

- Ramsey, J. A. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 24, Supplement 24-4, 32-37. [CrossRef]

- Huheey, J. E. in Inorganic Chemistry, Principles of Structure and Reactivity, 3rd edn. Harper & Row, New York (1983). Japanese translation by G. Kodama, H. Nakazawa, Tokyo Kagaku Dojin (Tokyo, 1984), p. 52.

- Momose, Y.; Suzuki, D.; Tsuruya, K.; Sakurai, T.; Nakayama, K. Friction 2018, 6(1), 98-115. [CrossRef]

- Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York (1956), Japanese translation by Uno, R.; Tsuya, N.; Morita, A.; Yamashita, J., Maruzen (Tokyo, 1963), p.300.

- Juse, W, P.; Kurtschatow, B. W. Phys. Zeits. d. Sowjetunion, 1933, 2, 463.

- Mott, N. F.; Gurney, R. W. Electronic Processes in Ionic Crystals, 2nd edn. Clarendon, Oxford (1957), pp. 163-164.

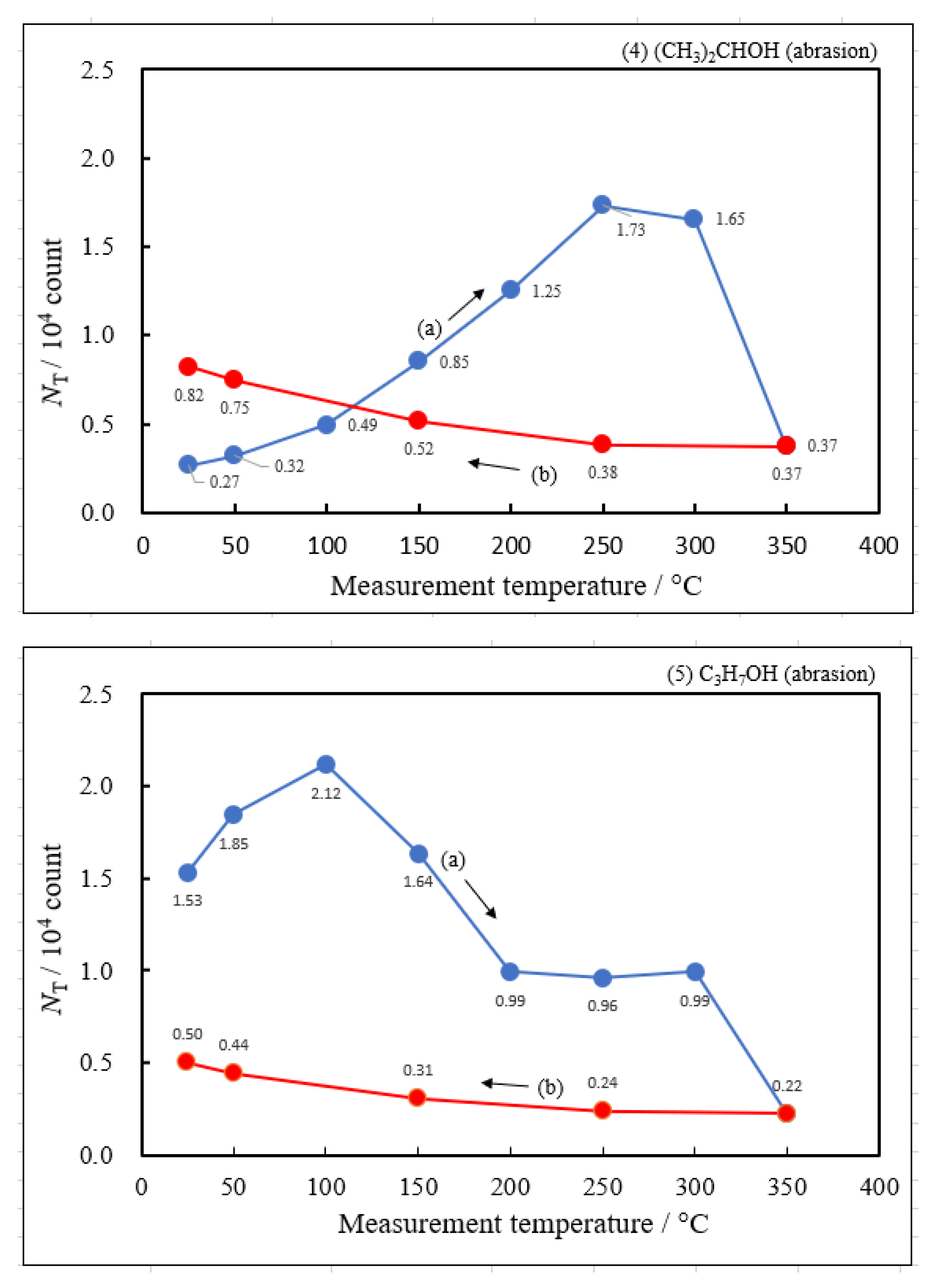

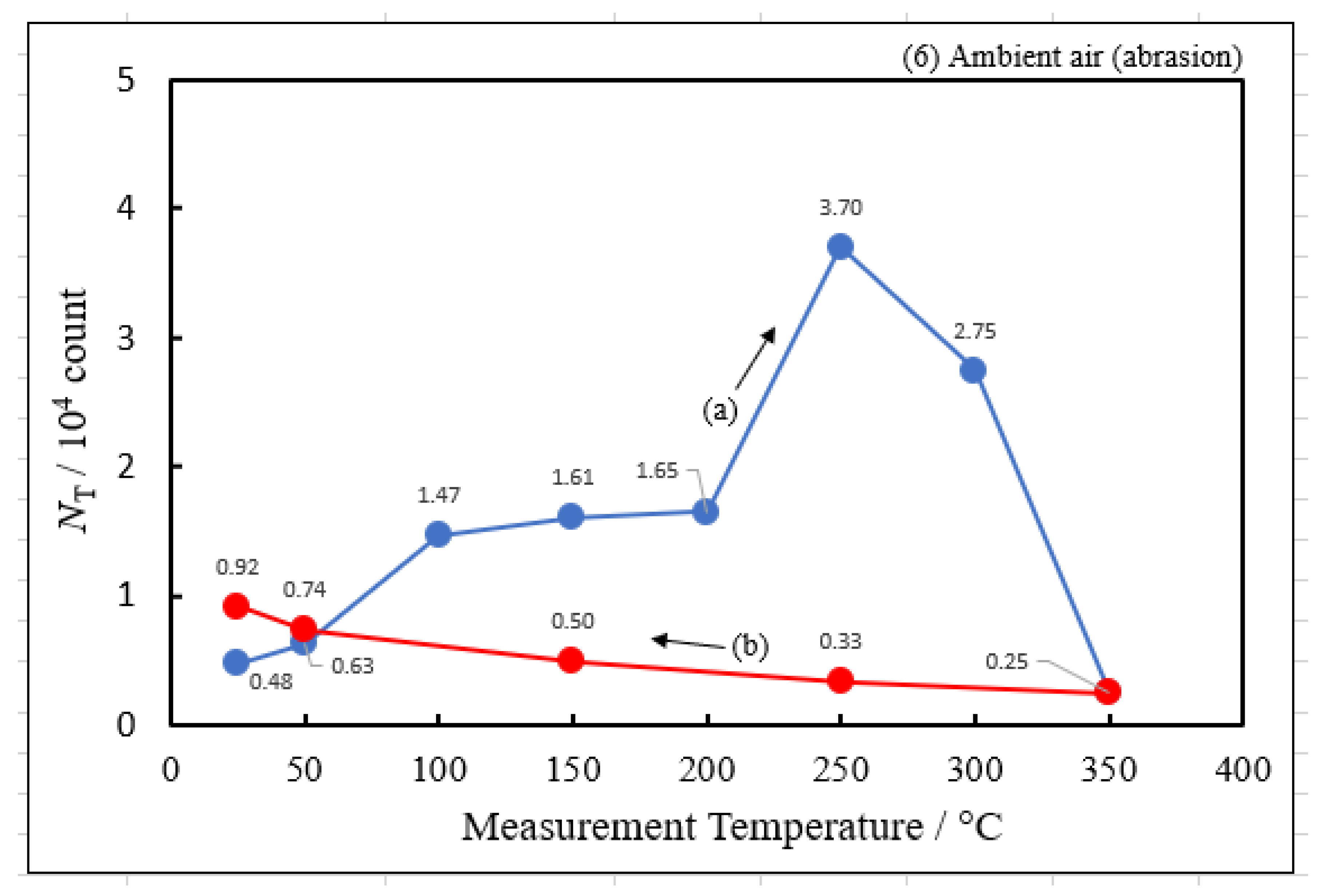

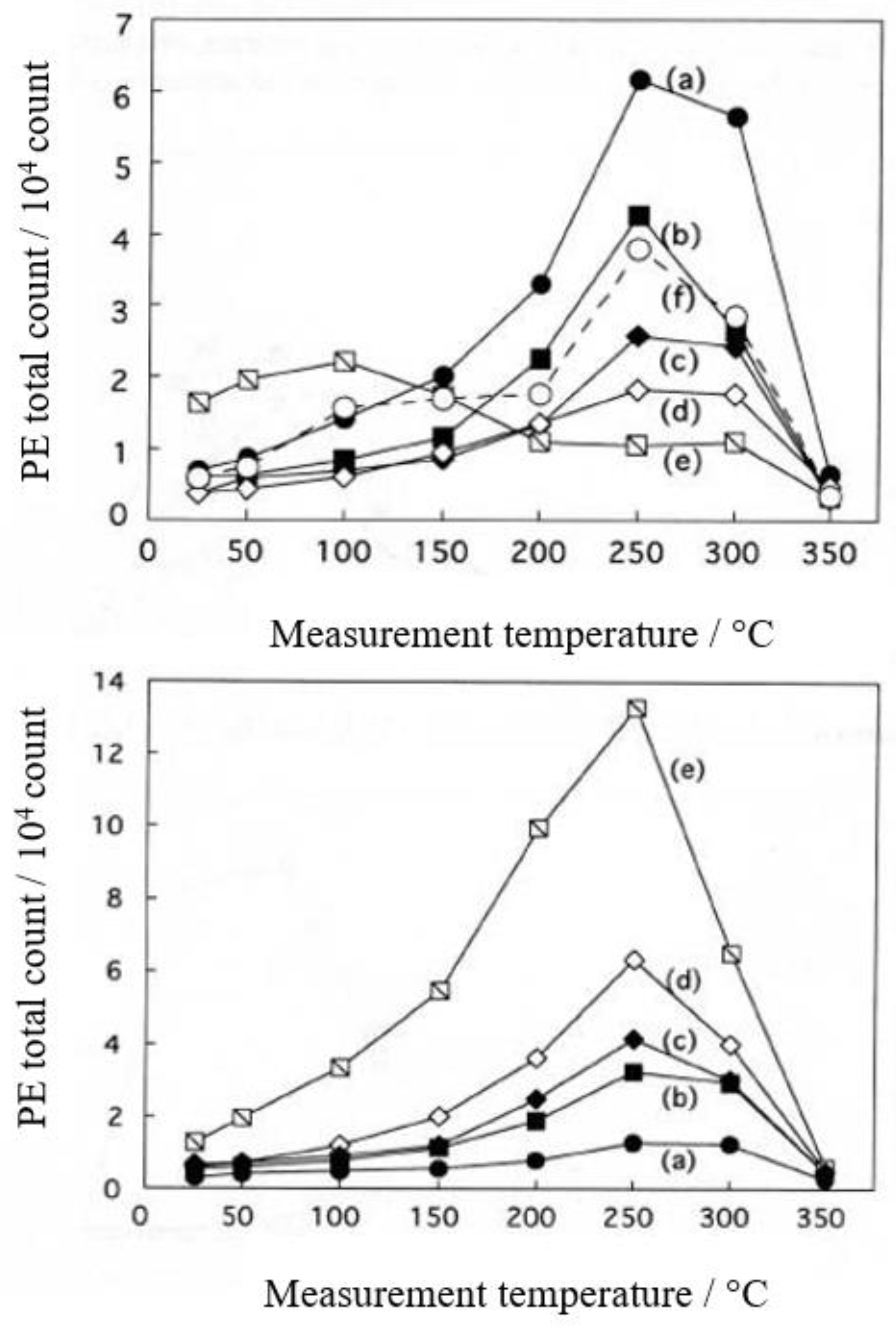

| Liquids and ambient air as environments used for abrading | Maximum of NTa during the Up1 process | Temperature of NTmaxa during the Up1 process | Activation energy in 1st temperature-increase process | Activation energy in 1st temperature-decrease process | Pre-exponential factor in 1st temperature-increase process | Activation energy in 2nd temperature-increase process | Activation energy in 2nd temperature-decrease process |

| NTmaxa / 104count | Tmaxa / °C | ΔEaUp1 / eV | ΔEaDown1 / eV | A0NTa / count | ΔEaUp2 / eV | ΔEaDown2 / eV | |

| (1) Water | 6.07 | 250 | 0.391 | −0.161 | 1.53×107 | −0.131 | −0.214 |

| (2) Methanol | 4.18 | 250 | 0.363 | −0.154 | 6.17×106 | ||

| (3) Ethanol | 2.49 | 250 | 0.338 | −0.161 | 2.68×106 | ||

| (4) 2-Propanol | 1.73 | 250 | 0.336 | −0.133 | 2.27×106 | ||

| (5) 1-Propanola) | 2.12 | 100 | -0.164 | −0.131 | 9.13×102 | ||

| (6) Ambient air | 3.70 | 250 | 0.315 | −0.169 | 3.12×106 |

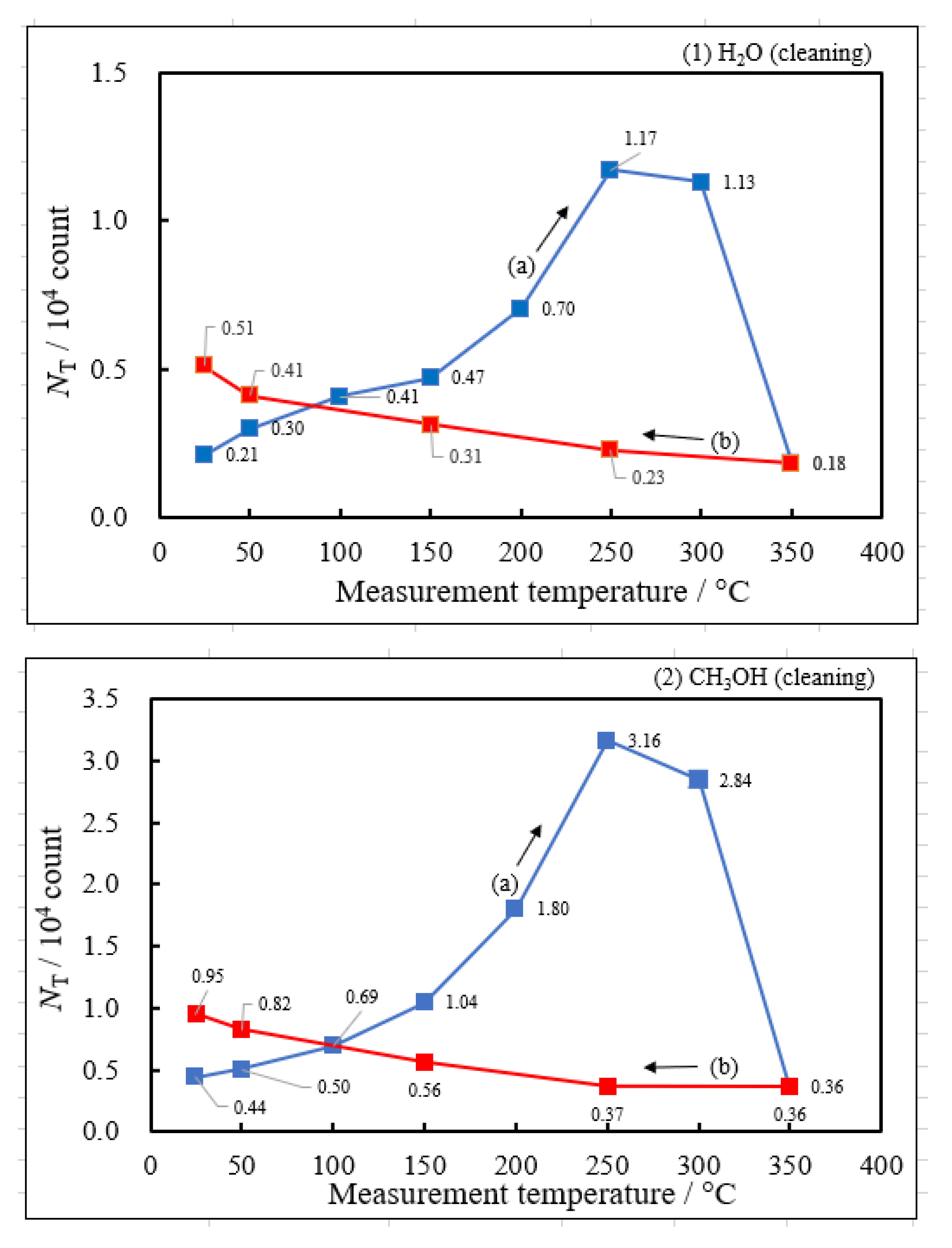

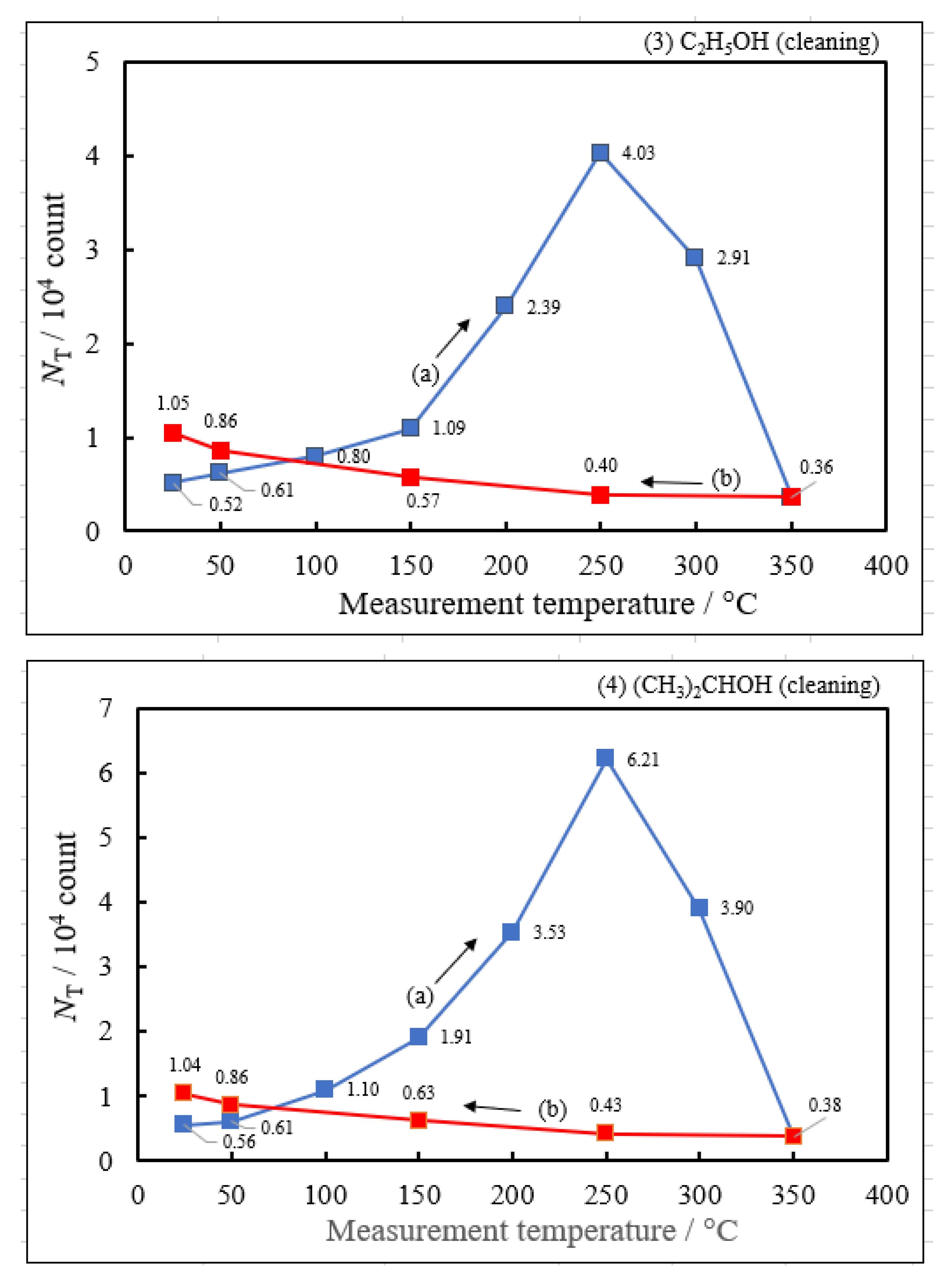

| Liquids used for cleaning | Maximum of NTc during the Up1 scan | Temperature of NTmaxc during the Up1 scan | Activation energy in 1st temperature-increase process | Activation energy in 1st temperature-decrease process | Pre-exponential factor in 1st temperature-increase process | Activation energy in 2nd temperature-increase process | Activation energy in 2nd temperature-decrease process |

| NTmaxc / 104count | Tmaxc /°C | ΔEcUp1 / eV | ΔEcDown1 / eV | A0NTc / count | ΔEcUp2 / eV | ΔEcDown2 / eV | |

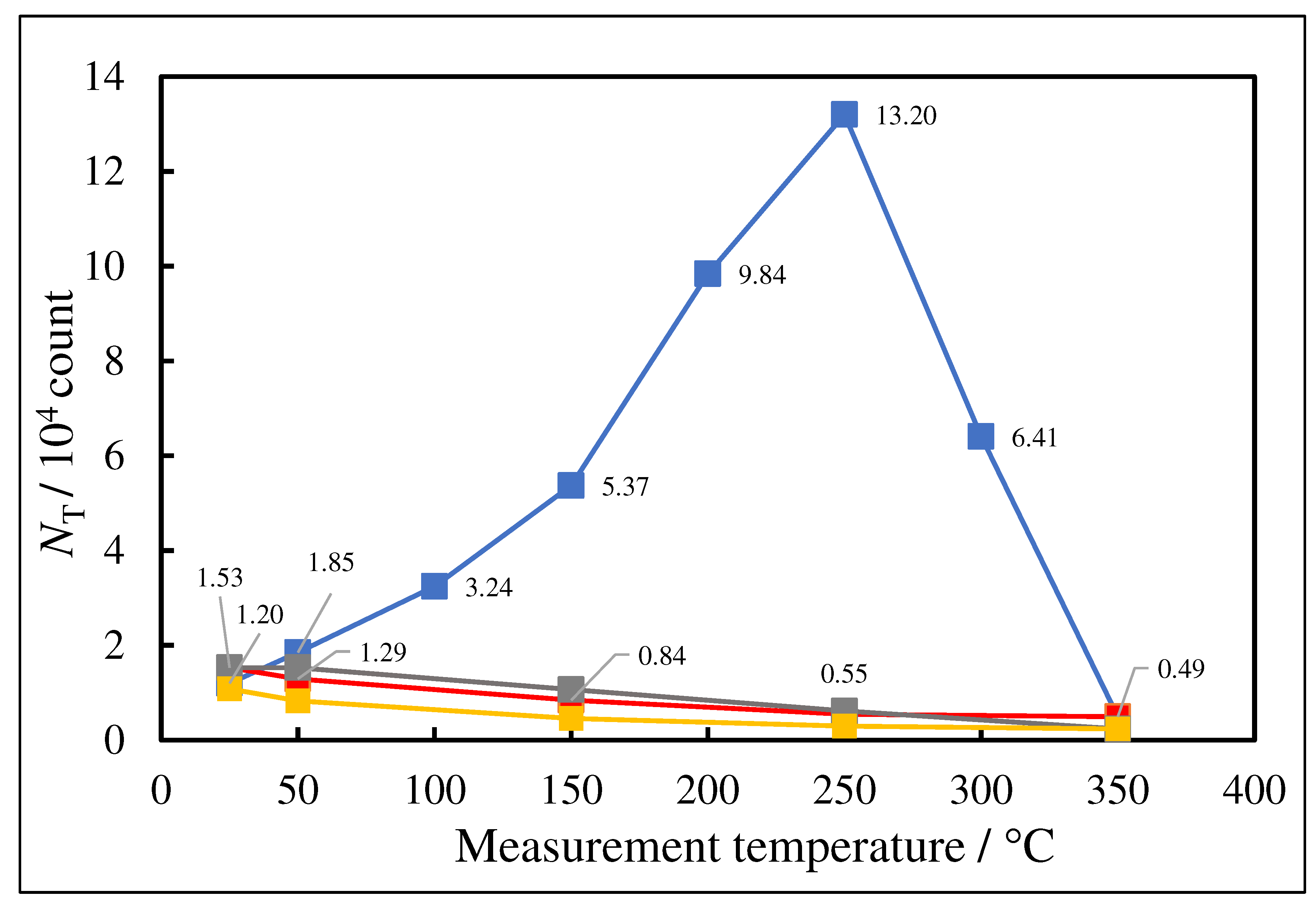

| (5) 1-Propanol | 13.2 | 250 | 0.419 | −0.175 | 6.13×107 | −0.158 | −0.222 |

| (4) 2-Propanol | 6.21 | 250 | 0.398 | −0.148 | 1.77×107 | ||

| (3) Ethanol | 4.03 | 250 | 0.348 | −0.166 | 5.03×106 | ||

| (2) Methanol | 3.16 | 250 | 0.335 | −0.160 | 3.39×106 | ||

| (1) Water | 1.17 | 250 | 0.267 | −0.101 | 4.90×105 |

| Liquids used for abrading and ultrasonic cleaning | Acceptor numbera)b) | Dielectric constant (25°C)d) | Reciprocal of dielectric constant |

| AN | e/e0 | 1/ (e/e0) | |

| (1) Water (H2O) | 54.8 | 78.39 | 0.0128 |

| (2) Methanol (CH3OH) | 41.3 | 32.70 | 0.0306 |

| (3) Ethanol (C2H5OH) | 37.1 | 24.55 | 0.0407 |

| (4) 2-Propanol (CH3)2CHOH) | 33.5c) | 19.92 | 0.0502 |

| (5) 1-Propanol (C3H7OH) | 20.33 | 0.0492 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).