Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Tourism, Planning, and Land-Use/Land-Cover Changes

2. Kızkalesi as a Tourism Destination

3. Research Methodology

4. Results and Discussions

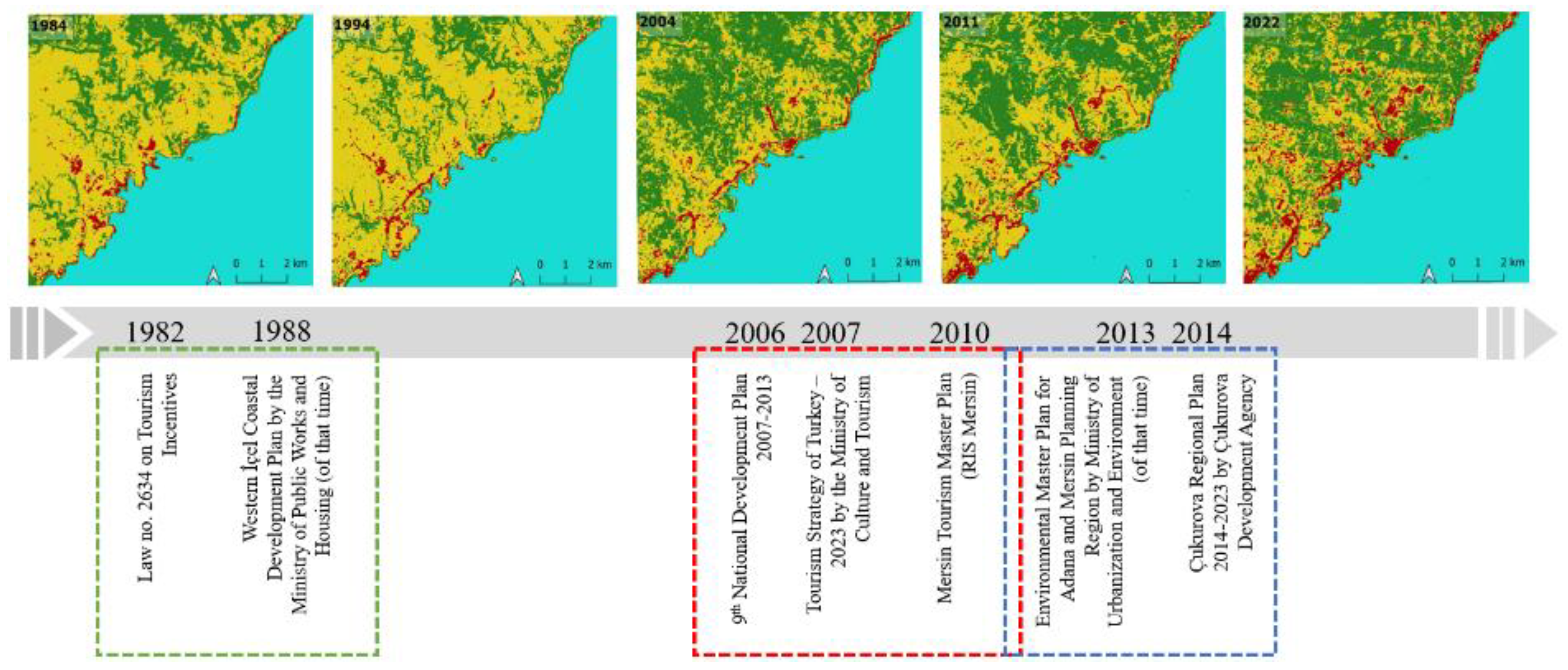

4.1. The Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Land-Use/Land-Cover in the Western Coastline of Mersin and Kızkalesi

4.2. The Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Land-Use/Land-Cover in the Western Coastline of Mersin and Kızkalesi

| Year | Document / Plan | Scale / Type | Decision / Impact on Inner Coastline Tourism Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Law no. 2634 on Tourism Incentives |

National Level Legal Document |

Increase in the number of summer houses constructed |

| 1988 | Western İçel Coastal Development Plan by the Ministry of Public Works and Housing (at that time) |

Regional Level 1/25,000 scale spatial plan |

Increase in the number of summer houses constructed |

| 2006 | 9th National Development Plan 2007-2013 |

National Level Strategic Document |

Tourism as one of the basic economic sectors to be supported |

| 2007 | Tourism Strategy of Turkey 2023 by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism |

National Level Strategic Document |

Tourism centres in the western coastline declared |

| 2010 | Mersin Tourism Master Plan (RIS-Mersin) |

Regional Level Strategic Document |

Tourism as one of the three pillars of regional/local economy |

| 2013 | Environmental Master Plan for Adana and Mersin Planning Region by the Ministry of Urbanization and Environment (as named at that time) |

Regional Level 1/100,000 scale spatial plan |

New tourism development zones especially for the construction of summer houses |

| 2014 | Çukurova Regional Plan 2014-2023 by Çukurova Development Agency |

Regional Level Strategic Document |

Keeping the existing situation along the inner coastline |

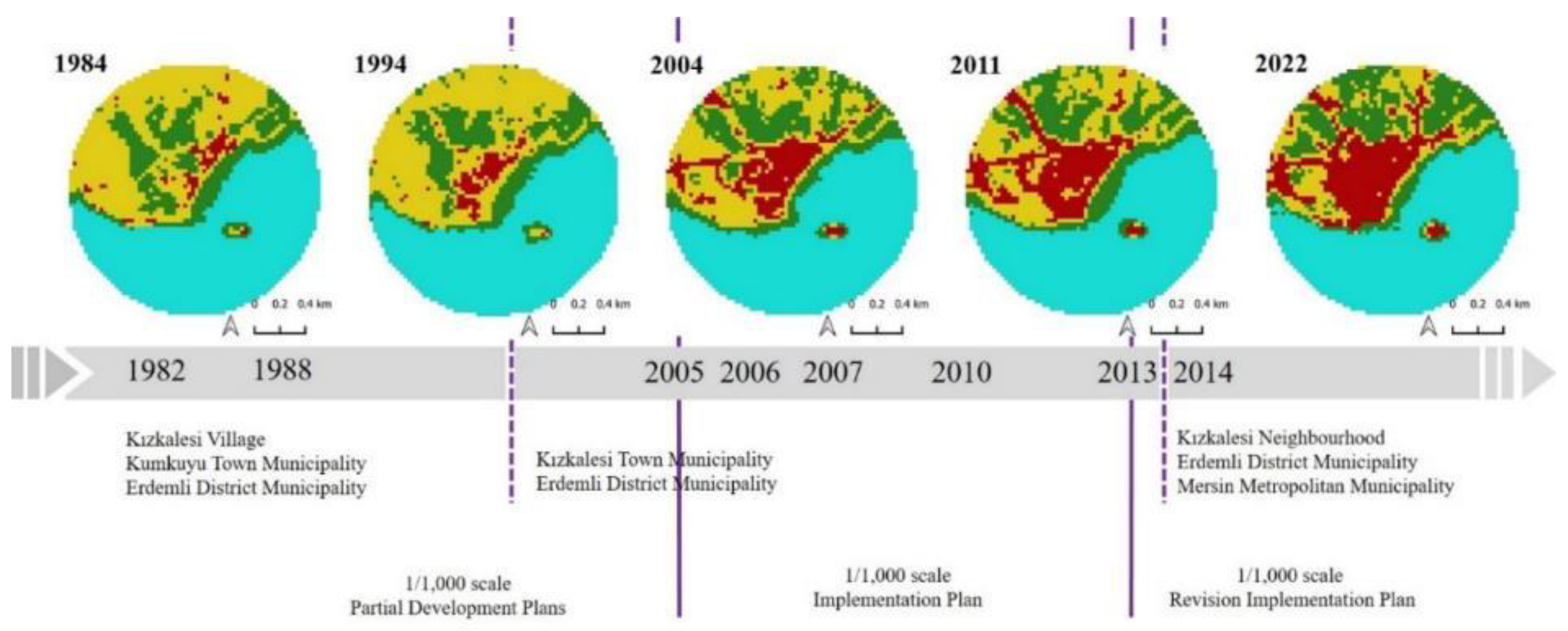

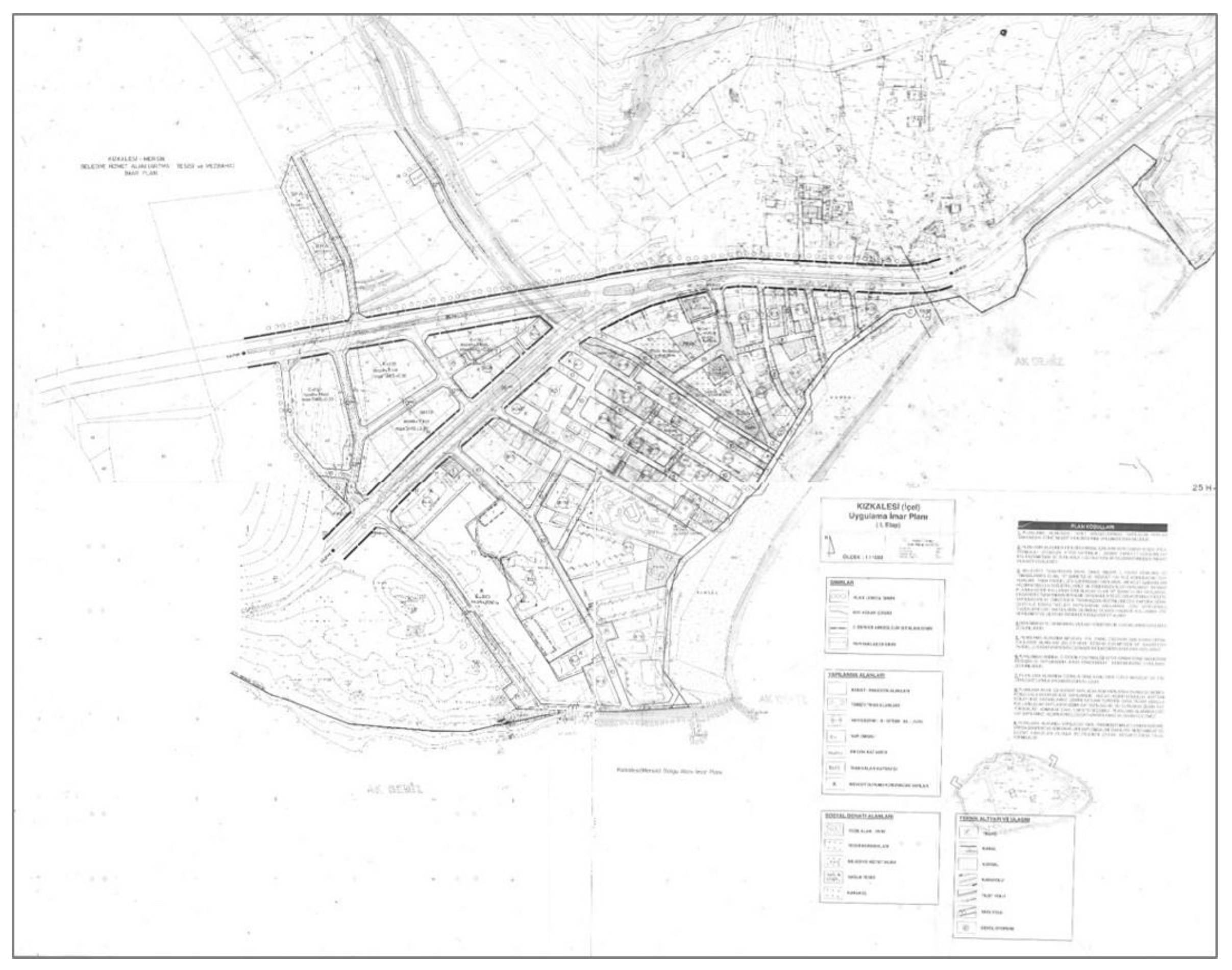

4.3. Spatial Plans and Land-Use/Land-Cover Change in Kızkalesi

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Briassoulis, H. Sustainable Tourism and the Question of the Commons. Annals of Tourism Research 2002, 29(4), 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. More than an “industry”: The forgotten power of tourism as a social force. Tourism Management 2006, 27(6), 1192–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, R.R.; Faniza, V. Land Cover Change Impact on Coastal Tourism Development near Pacitan Southern Ringroad. MIMBAR : Jurnal Sosial dan Pembangunan 2021, 37(1), 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atik, M.; Altan, T.; Artar, M. Land Use Changes in Relation to Coastal Tourism Development in Turkish Mediterranean. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2010, 19(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Boori, M.S.; Voženílek, V.; Choudhary, K. Land cover disturbance due to tourism in Jeseníky mountain region: A remote sensing and GIS based approach. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2015, 18(1), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.; Paul, S. An insight on land use and land cover change due to tourism growth in coastal area and its environmental consequences from West Bengal, India. Spatial Information Research 2021, 29(4), 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerić, D.; Czapiewski, K. Diverse Challenges of Tourism Spatial Planning: Evidence from Italy, Norway, Poland, Portugal, and Turkey. In Contemporary Challenges of Spatial Planning in Tourism Destinations; Napierała, T., Leśniewska-Napierała, K., Cotella, G., Eds.; The SPOT Project: Lodz, 2022; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risteskia, M.; Kocevskia, J.; Arnaudov, K. Spatial Planning and Sustainable Tourism as Basis for Developing Competitive Tourist Destinations. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2021, 44, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkiye Gazetesi. Mersin'de nüfus patladı, plajlar hareketlendi [Population boomed in Mersin, beaches became lively]; 22 May 2018. Available online: https://www.turkiyegazetesi.com.tr/yasam/mersinde-nufus-patladi-plajlar-hareketlendi-561322 (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Sarıkaya Levent, Y.; , Levent, T., Birdir, K., & Sahilli Birdir, S. Local Attraction Centre Kızkalesi: The Natural and Cultural Assets for Sustainable Tourism. The SPOT Project: Lodz, 2022. Available online: https://spot-erasmus.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/TurkeyCaseStudy_SPOT_vFINAL.pdf (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Gezginci. Mersin Kızkalesi Plajı [Mersin Kızkalesi Beach]; 10 June 2022. Available online: https://gezicini.com/kizkalesi-plaji/ (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Koca, H.; Şahin, İ.F. Turistik Aktiviteye Katkıları Yönünden Kızkalesi Kasabası [Kızkalesi Town in terms of Touristic Activities]. Türk Coğrafya Dergisi 1998, 33, 349–375. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Liu, J.; Kuang, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yan, C.; Li, R.; Wu, S.; Hu, Y.; Du, G.; Chi, W.; Pan, T.; Ning, J. Spatiotemporal patterns and characteristics of land-use change in China during 2010–2015. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2018, Volume 28, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleit, S.; Ennos, R.; Golding, Y. Modeling the environmental impacts of urban land use and land cover change - a study in Merseyside, UK. Landscape and Urban Planning 2005, Volume 71, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, J.S.; Kumar, M. Monitoring land use/cover change using remote sensing and GIS techniques: A case study of Hawalbagh block, district Almora, Uttarakhand, India. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2015, 18(1), 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalayer, S.; Sharifi, A.; Abbasi-Moghadam, D.; Tariq, A.; Qin, S. Modeling and predicting land use land cover spatiotemporal changes: a case study in chalus watershed, Iran. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2022, Volume 15, 5496–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaddor, I.; Achab, M.; Soumali, M.R.; Alaoui, A.H. Rainfall-Runoff calibration for semi-arid ungauged basins based on the cumulative observed hyetograph and SCS Storm model: Application to the Boukhalef watershed (Tangier, North Western Morocco). J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 3795–3808. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Cheng, G.; Ge, Y.; Li, H.; Han, F.; Hu, X.; Tian, W.; Tian, Y.; Pan, X.; Nian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ran, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, B.; Yang, D.; Zheng, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Cai, X. Hydrological cycle in the Heihe River Basin and its implication for water resource management in endorheic basins. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2018, 123(2), 890–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jia, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; El-Hamid, A.; Hazem, T. Remote sensing inversion for simulation of soil salinization based on hyperspectral data and ground analysis in Yinchuan, China. Natural Resources Research 2021, 30(6), 4641–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B.W.; Prasad, A. S. Slope vulnerability, mass wasting and hydrological hazards in Himalaya: a case study of Alaknanda Basin, Uttarakhand. Terræ Didatica 2018, 14(4), 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Kawy, O.R.; Rød, J.K.; Ismail, H.A.; Suliman, A. S. Land use and land cover change detection in the western Nile delta of Egypt using remote sensing data. Applied Geography 2011, 31(2), 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirui, K.B.; Kairo, J.G.; Bosire, J.; Viergever, K.M.; Rudra, S.; Huxham, M.; Briers, R.A. Mapping of mangrove forest land cover change along the Kenya coastline using Landsat imagery. Ocean & Coastal Management 2013, 83, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cuervo, A.M.; Aide, T.M.; Clark, M.L.; Etter, A. Land cover change in Colombia: surprising forest recovery trends between 2001 and 2010. PLOS ONE 2012, 7(8), e43943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napierała, T.; Leśniewska-Napierała, K.; Cotella, G. Theoretical Fundamentals of Sustainable Spatial Planning of European Tourism Destinations. In Contemporary Challenges of Spatial Planning in Tourism Destinations; Napierała, T., Leśniewska-Napierała, K., Cotella, G., Eds.; The SPOT Project: Lodz, 2022; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, A.; Clerici, N.; Quesada, B. A 30 m-resolution land use-land cover product for the Colombian Andes and Amazon using cloud-computing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 107, 102688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, A.; Araújo Júnior, G.; Silva, M.; Santos, A.; Silva, J.; Pandorfi, H.; Oliveira-Júnior, J.; Teixeira, A.; Teodoro, P.E.; Lima, J.; Silva Junior, C.; de Souza, L.; Silva, E.A.; Silva, T.G.F. Using Remote Sensing to Quantify the Joint Effects of Climate and Land Use/Land Cover Changes on the Caatinga Biome of Northeast Brazilian. Remote Sensing 2022, 14(8), 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midekisa, A.; Holl, F.; Savory, D.J.; Andrade-Pacheco, R.; Gething, P.W.; Bennett, A.; Sturrock, H. J. Mapping land cover change over continental Africa using Landsat and Google Earth Engine cloud computing. PLOS ONE 2017, 12(9), e0184926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rujoiu-Mare, M.R.; Mihai, B.A. Mapping land cover using remote sensing data and GIS techniques: A case study of Prahova Subcarpathians. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2016, Volume 32, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarira, D.; Mutanga, O.; Naidu, M. Google Earth Engine for Informal Settlement Mapping: A Random Forest Classification Using Spectral and Textural Information. Remote Sensing 2022, 14(20), 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, A.J.; Thenkabail, P.S.; Teluguntla, P.; Xiong, J.; Gumma, M.K.; Congalton, R.G.; Yadav, K. Mapping cropland extent of Southeast and Northeast Asia using multi-year time-series Landsat 30-m data using a random forest classifier on the Google Earth Engine Cloud. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, Volume 81, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.; Kuch, V.; Lehnert, L. W. Land Cover Classification using Google Earth Engine and Random Forest Classifier—The Role of Image Composition. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(15), 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teluguntla, P.; Thenkabail, P.S.; Oliphant, A.; Xiong, J.; Gumma, M.K.; Congalton, R.G.; Yadav, K.; Huete, A. A 30-m landsat-derived cropland extent product of Australia and China using random forest machine learning algorithm on Google Earth Engine cloud computing platform. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2018, Volume 144, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özüpekçe, S. Turizme Bağlı Olarak Büyüyen Bir Yerleşme: Kızkalesi, Erdemli/ Mersin [A Settlement Growing Depending on Tourism: Kızkalesi, Erdemli/ Mersin]. In the Proceedings of VIII. National IV. International Eastern Mediterranean Tourism Symposium, Anamur, Mersin. p. 2019.

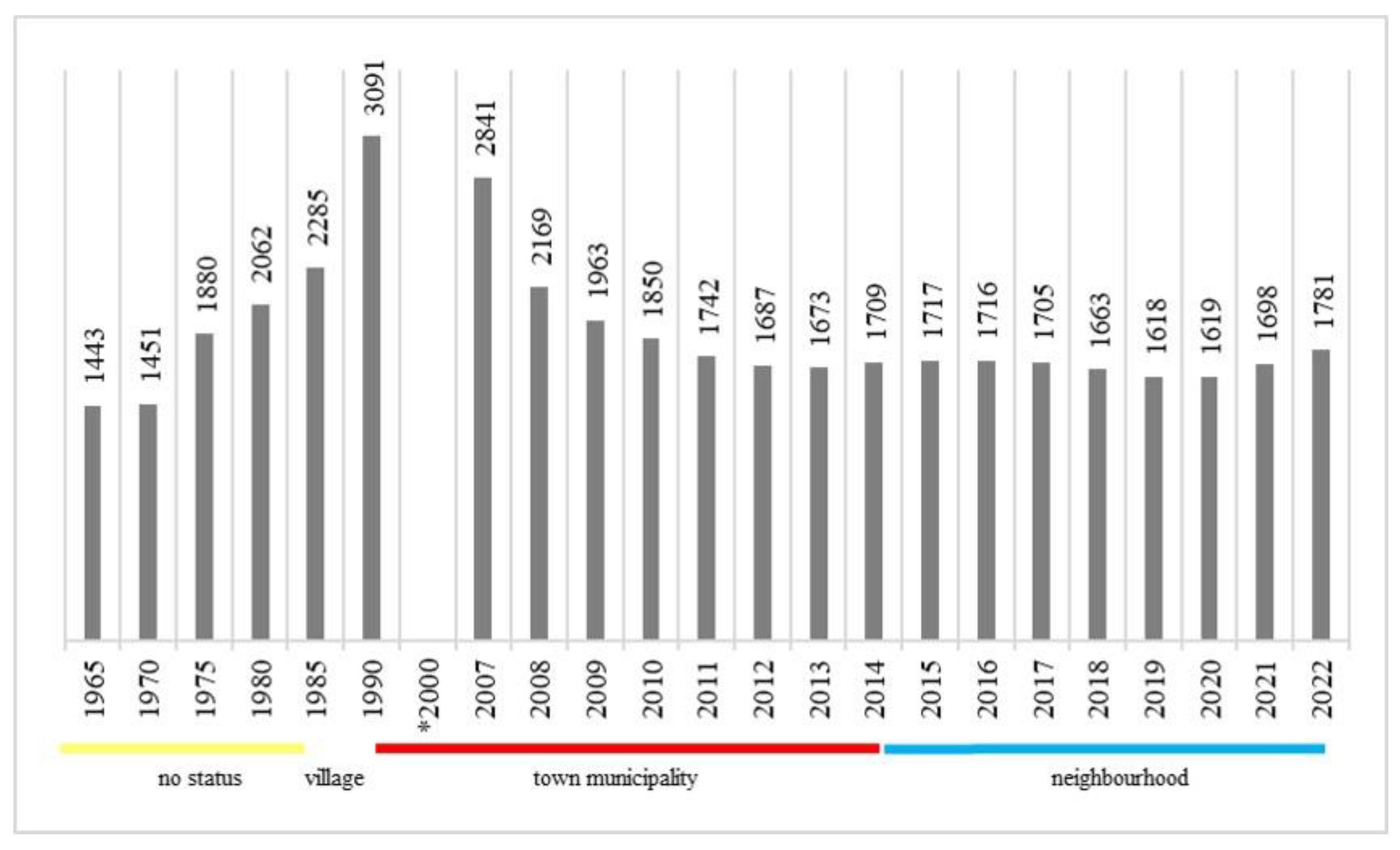

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TSI). Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Kayıt Sistemi Veri Tabanı [Address Based Population Registration System Database]. Available online: https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=95&locale=tr (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Akpınar, E. 2000 Genel Nüfus Sayımına Eleştirel Bir Bakış: Erzincan Örneği [A Critical Viev to 2000 General Population Census: Erzincan Case]. Doğu Coğrafya Dergisi 2005, 10, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Levent, T.; Sarıkaya Levent, Y.; Birdir, K.; Sahilli Birdir, S. Spatial Planning System in Turkey: Focus on Tourism Destinations. In Contemporary Challenges of Spatial Planning in Tourism Destinations; Napierała, T., Leśniewska-Napierała, K., Cotella, G., Eds.; The SPOT Project: Lodz, 2022; pp. 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolal, M. History of Tourism Development in Turkey. In Alternative Tourism in Turkey: Role, Potential Development and Sustainability; Egresi I., Ed.; Springer Cham, 2019; pp. 23-33. [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, C. Tourism Policies. Bilkent University: Ankara, 1999.

- Oskay, C. Mersin Turizminin Türkiye Ekonomisindeki Yeri ve Önemi [The Importance and Place of Tourism in Mersin in Turkish Economy]. Çukurova Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2012, 21, 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Tourism Strategy of Tukey 2023. Ministry of Culture and Tourism: Ankara, 2007. Available online: https://www.ktb.gov.tr/Eklenti/43537,turkeytourismstrategy2023pdf.pdf (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- State Planning Organisation. 9. Kalkınma Planı 2007-2013 [9th National Development Plan 2007-2013]. Official Gazette no. 26215: Ankara, 2006. Available online: https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Dokuzuncu_Kalkinma_Plani-2007-2013.pdf (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Mersin Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Mersin Bölgesel İnovasyon Stratejisi 2006 – 2016 [Mersin Regional Innovation Strategy 2006 – 2016]. Mersin Chamber of Commerce and Industry: Mersin, 2008. Available online: https://oda.mtso.org.tr/files/mersin_inovasyon_stratejisi.pdf (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Levent, T.; Sarıkaya Levent, Y. RIS-Mersin Projesi ve Mersin Bölgesel Yenilik Stratejisi: Yenilik Üzerine Yerel Bir Değerlendirme [RIS-Mersin Project and Mersin Regional Innovation Strategy: A Local Evaluation on Innovation]. In VII. Ulusal Coğrafya Sempozyumu, TÜCAUM, Ankara, 18-19 October 2012.

- Gök, T. RIS Mersin Projesi Üzerine Bir Özet Değerlendirme [A Short Evaluation on RIS Mersin Project]. Planlama 2009, 3–4, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mersin Special Provincial Administration. Mersin İli Turizm Master Planı [Mersin Province Tourism Master Plan]. Mersin, 2010. Available online: http://www.mersin.gov.tr/kurumlar/mersin.gov.tr/Genel/depo/ARASTIRMA_RAPORU(1).pdf (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Metin, H. (2010). Social and Institutional Impacts of Mersin Regional Innovation Strategy: Stakeholders’ Perspective. Master Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, 28 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Çukurova Development Agency. Çukurova Bölge Planı 2014-2023 [Çukurova Regional Plan 2014-2023]. Adana, 2015. Available online: https://www.cka.org.tr/uploads/pages_v/2014--2023-cukurova-bolge-plani.pdf (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. Mersin – Adana Planlama Bölgesi 1/100.000 Ölçekli Çevre Düzeni Planı Revizyonu (Mersin İli) Plan Açıklama Raporu [Mersin - Adana Planning Region 1/100,000 Scale Environmental Plan Revision (Mersin Province) Plan Report]. Ankara, 2017. Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/mpgm/editordosya/file/CDP_100000/ma/PLANACIKLAMARAPORU_mersinrevizyon_03042017.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. Mersin – Adana Planlama Bölgesi 1/100.000 Ölçekli Çevre Düzeni Planı Revizyonu Plan Hükümleri [Mersin - Adana Planning Region 1/100,000 Scale Environmental Plan Revision Plan Provisions]. Ankara, 2017. Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/mpgm/editordosya/file/CDP_100000/ma/PLANHUKUMLERI_03042017.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Kızkalesi Municipality. Kızkalesi Municipality Council Decision no.23 dated on 23.12.2013. Mersin Metropolitan Municipality Archive: Mersin, 2013.

- Mersin Portal. Kızkalesi'nde Bayram Yoğunluğu [Bayram Intensity in Kızkalesi]; 03 August 2020. Available online: https://www.mersinportal.com/mersin/kizkalesi-nde-bayram-yogunlugu-h57107.html (accessed on 27.10.2023).

- Turizm Günlüğü. Kızkalesi festivali ve kumdan heykeller turistleri Mersin sahillerine çekti [Kızkalesi festival and sand sculptures attract tourists to Mersin beaches]; 09 July 2017. Available online: https://www.turizmgunlugu.com/2017/07/09/kizkalesi-festivali-kumdan-heykeller-turistleri-mersin-sahillerine-cekti/ (accessed on 27.10.2023).

| Kızkalesi Tourism Facilities |

1990s | 2020s | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Bed capacity | Number | Bed capacity | |

| Hotel | 14 | 615 | 104 | 4,750 |

| Motel | 18 | 430 | ||

| Pension | 38 | 1,740 | ||

| Camping area | 2 | 200 | ||

| Summer house | 856 | 3,424 | 1,814 | 7,256 |

| Total | 928 | 6,409 | 1,918 | 12,006 |

| Satellite Image | Year | Overall Accuracy | Kappa Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landsat 5 TM | 1994 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| Landsat 7 ETM+ | 2004 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Landsat 7 ETM+ | 2011 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS | 2022 | 0.90 | 0.88 |

| 1984 | 1994 | 2004 | 2011 | 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | |

| Artificial | 246.42 | 2.07 | 247.68 | 2.08 | 295.47 | 2.48 | 428.31 | 3.60 | 708.57 | 5.95 |

| Vegetation | 4321.44 | 36.27 | 4659.12 | 39.11 | 2799.09 | 23.49 | 3108.87 | 26.09 | 2659.59 | 22.32 |

| Forest | 1974.51 | 16.57 | 1622.79 | 13.62 | 3426.21 | 28.76 | 2980.98 | 25.02 | 3154.86 | 26.48 |

| Water | 5371.38 | 45.09 | 5384.16 | 45.19 | 5392.98 | 45.27 | 5395.59 | 45.29 | 5390.73 | 45.25 |

| 1984 | 1994 | 2004 | 2011 | 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | Area (ha) | (%) | |

| Artificial | 8.37 | 2.72 | 11.16 | 3.63 | 32.49 | 10.56 | 43.20 | 14.04 | 53.37 | 17.35 |

| Vegetation | 98,55 | 32,04 | 98,64 | 32.07 | 72,09 | 23.43 | 66.33 | 21.56 | 47.79 | 15.54 |

| Forest | 54.27 | 17.64 | 53.91 | 17.52 | 57.33 | 18.64 | 54.72 | 17.79 | 61.02 | 19.84 |

| Water | 146.43 | 47.60 | 143.91 | 46.78 | 145.71 | 47.37 | 143.37 | 46.61 | 145.44 | 47.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).