1. Introduction

Chest trauma is one of the most serious and difficult injuries. It can occur because of penetrating or blunt trauma and can be life-threatening [

1,

2]. After trauma, various complications can develop, including the development of pneumonia, hemothorax, pneumothorax, and rib fractures, all of which lead to a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch. Ventilation-perfusion mismatch (V/Q) is a serious condition that can lead to systemic hypoxia. It is also the most common cause of hypoxemia. Alveolar units can move from a low V/Q region to a high V/Q region in the case of disease. A low V/Q ratio produces hypoxemia by decreasing alveolar oxygen delivery and decreasing alveolocapillary gas exchange (PaO

2). Subsequently, the arterial oxygen level will drop. In the presence of a larger area with hyperventilated and less perfused areas of the lung parenchyma or high V/Q units, changes in oxygenation may be so slight as to be unnoticeable. Disturbance of gas exchange can be manifested by an increase in the level of CO

2 in the circulation, such as in pulmonary embolism. In these situations, physiologic compensation for V/Q disorder will be a change in the breathing frequency or H

2CO

3 levels.

The prevention or reduction of non - non-ventilated lung areas (atelectasis) and rebalancing the pulmonary vascular tone is a challenging therapeutic strategy in the treatment of patients with acute respiratory failure [

3]. An important compensatory mechanism during hypoxemia, particularly when chronic, is hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. It is a homeostatic vasomotor mechanism that is intrinsic to the pulmonary vasculature [

4,

5]. Intrapulmonary arteries constrict in response to alveolar hypoxia, diverting blood to better-oxygenated lung segments, thereby optimizing oxygen uptake in atelectasis, pneumonia, asthma, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction mediates ventilation-perfusion matching and optimizes systemic pO

2 by reducing shunt fraction [

6].

However, impaired hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, whether due to disease or vasodilator drugs, exacerbates systemic hypoxemia. High perfusion in relation to ventilation (V/Q<1) and shunting (V/Q=0) is caused by not only impaired hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction but also redistribution of perfusion from obstructed lung vessels [

7]. During the causal treatment, this imbalance must be corrected by increasing the percentage of oxygen and lung ventilation pressures which leads to the correction of hypoxemia.

We will present an approach in the treatment of V/Q mismatch and systemic hypoxemia in acute pulmonary injury and during the recovery phase in a 53–year–old male patient admitted to the Intensive Care Unit due to severe respiratory insufficiency after chest trauma. We will also show how the late consequences of lung trauma, fibrosis, and bullous lung changes, led to an impaired diffusion capacity of the lungs in this patient.

2. Case Report

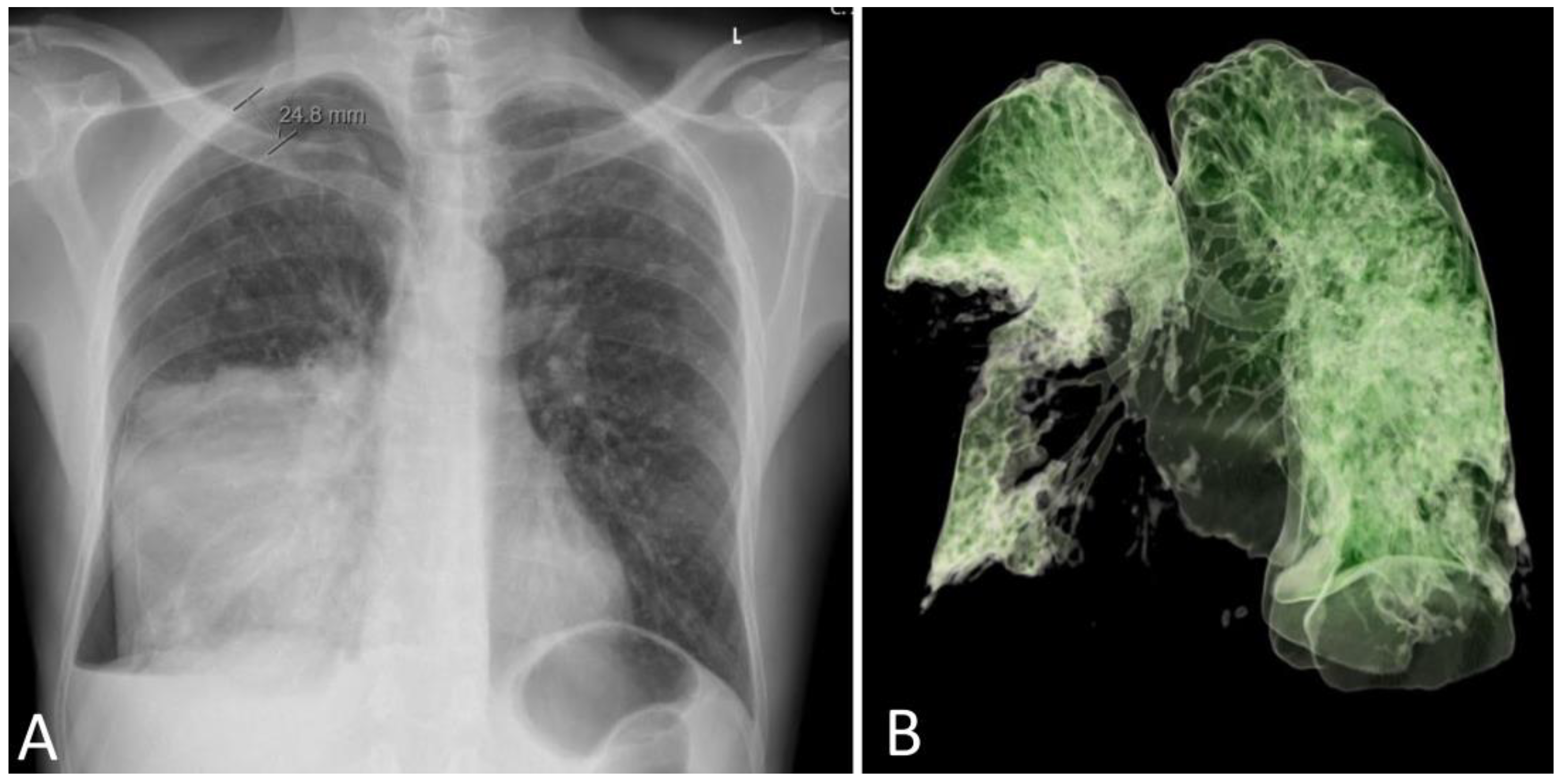

A 53–year–old male patient with no comorbidities or chronic therapy was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit due to severe respiratory failure. Five days before admission, the patient was hit by a metal object on the right side of the chest and complained of shortness of breath. Chest radiography revealed a right-sided pneumothorax and a thoracic drain was placed (

Figure 1A).

On admission, the patient was hemodynamically unstable, with an arterial blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg, a pulse of 125 beats/min, and tachypneic with a frequency of > 40 breaths/minute with oxygen saturation of 45% on room air. The leukocyte count was 5.3 × 109/L, platelet count was 138 x109/L, and C - reactive protein level was 523 mg/L (Supplemental File S1). Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis revealed a pH of 7.22, PaCO2 level of 7.22 kPa, PaO2 level of 6.8 kPa, and bicarbonate concentration of 19 mmol/L. His urine output was normal (300 mL/h). Early vasopressor therapy (noradrenaline 10–20 mL/h), oxygen therapy, and analgosedation with midazolam and fentanyl were initiated. The patient was intubated and mechanically ventilated with positive end–expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 10 cmH20 with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 0.6–0.8 on controlled mechanical ventilation (CMV) mode. Purulent secretions were drained from the thoracic drain. An emergency thoracic CT was performed and revealed extensive right-sided pneumonia of the lower and middle lung lobes and a minimal effusion of 1 cm. After microbiology samples were taken, empirical broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy consisting of cefepime (2 g every 12 hours) and levofloxacin (500 mg every 12 hours) was initiated. Due to severe hemodynamic instability, analgosedation was discontinued.

The patient's respiration did not improve within the first 2 days. Linezolid (600 mg every 12 hours) and meropenem (1g every 24 hours) replaced the previous antibiotics on day 3. He was febrile (38.9°C), unconscious on day 4, and was still ventilated with PEEP of 10 cmH2O with a FiO2 of 0.6 to obtain oxygen saturation >90%. Tracheal aspirate and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples did not confirm pathogenic bacteria. Due to paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, a cardiologist was consulted, who suggested IV propafenone therapy. On day 6, the patient was agitated, he was unconscious, unable to communicate, and breathed in synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) mode. Upon auscultation a bronchial whistling and coarse rales were audible. The abdomen was soft, peristalsis was audible. With propafenone therapy, the patient was in sinus rhythm with a frequency of 60 beats/min.

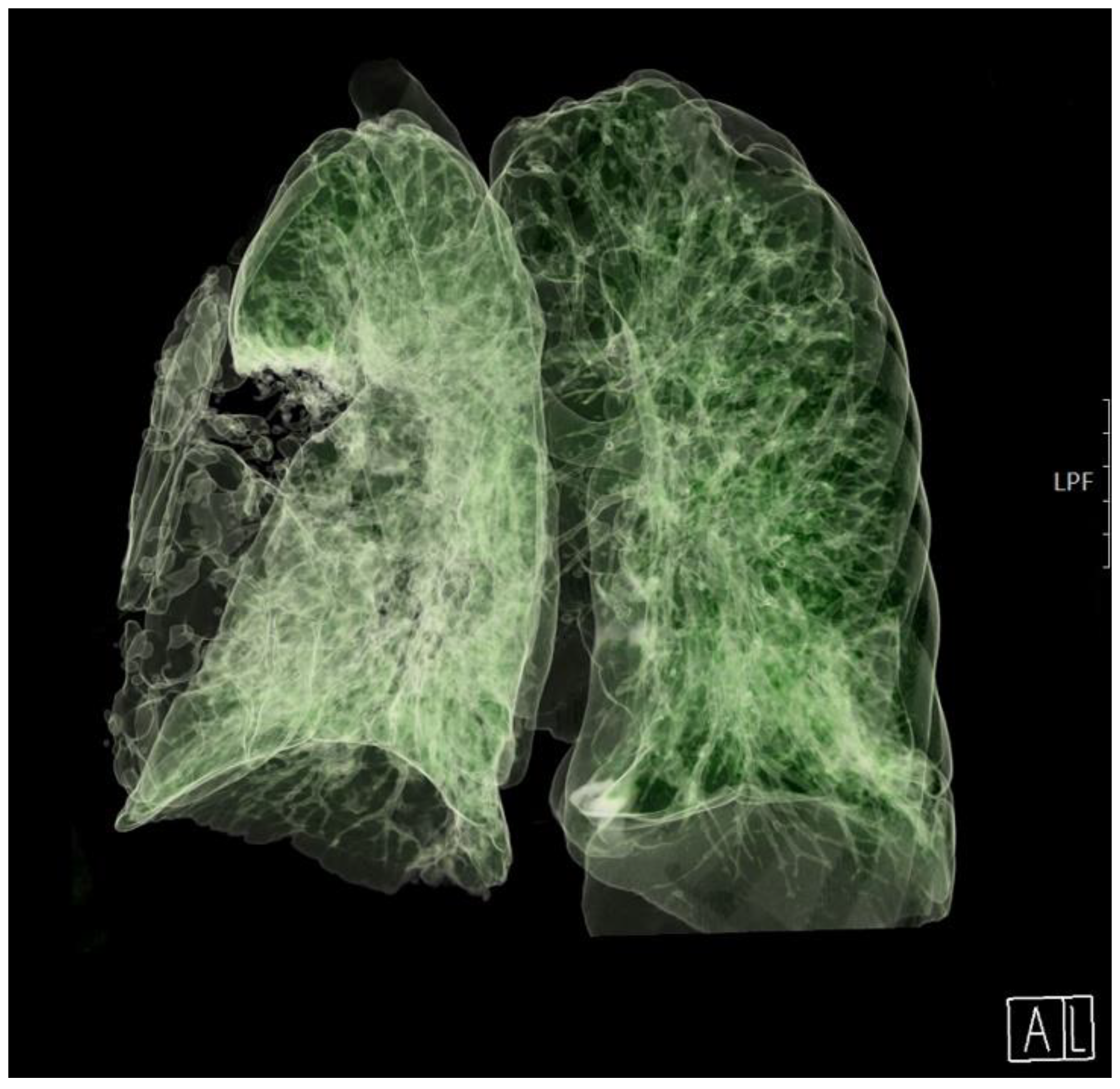

On day 8, due to the patient's restlessness and inability to synchronize with the ventilator, a continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine was introduced, followed by a continuous infusion of midazolam and fentanyl due to extremely difficult ventilation with high oxygen concentrations and respiratory pressures (Paw greater than 30). A control CT of the thorax was performed, which revealed deterioration in terms of the progression of the inflammatory infiltrate to the right lung lobe (

Figure 2, Video S1). A thoracic surgeon was consulted several times.

He was hemodynamically stable during the day, with a decline in inflammatory parameters (CRP 207 mg/L, PCT 1.53 ng/mL) and with the presence of thrombocytopenia (platelet count 68x10

9/L) (

Table 1). He regained consciousness and was successfully weaned from the ventilator on day 10. On physical examination, he still had prolonged expiration and crackles on the right side of the lung. All microbiological samples taken from the lungs remained sterile despite purulent secretions from the thoracic drain.

On day 15, a bronchoscopy with microbiology sampling was performed. After

S. maltophilia was identified from the bronchoalveolar lavage, he was treated with sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. His white blood cell count was 16.3 × 10*/L, platelet count was 361 x 10

9/L and C-reactive protein level was 203 mg/L (

Table 1).

On day 18, the patient was awake, conscious, oriented, and breathing spontaneously via face mask, and his SpO2 was 95%. The patient’s clinical status and chest radiograph both improved, and the thoracic drain was removed. The same day after the drain was removed, Sp02 decreased with silent breathing sounds apically on the right lung. Pneumothorax was suspected and confirmed after a chest radiograph. Re - thoracentesis was performed.

The patient's clinical condition improved in the following days, and he continued to breathe spontaneously with oxygenation. The control chest radiograph of the lung revealed complete expansion of the lung parenchyma with lung infiltrates on the medial and lower lung lobes. The patient's general condition gradually improved, and he was transferred to the ward on day 19 after ICU admission with supplemental oxygenation of 4 L O

2/min via the nasal catheter and frequency of 18–20 breaths/minute with adequate oxygen saturation of 95–97%. The thoracic drain was removed on the ward (

Figure 3).

FOLLOW UP. After the surgical treatment was completed, the patient’s medical therapy continued at the Department of Pulmonary Diseases. Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim was continued for a total of 14 days. He stopped smoking. Breathing problems, especially productive cough, mild tachypnea, and shortness of breath, lasted 3 months after the end of the ICU treatment.

Spirometry that was done 6 months later. It confirmed that the patient’s FEV1 was 102%; FVC was 99%, while carbon monoxide (CO) diffusion capacity was reduced to 59%, and diffusion coefficient was 56%. The proportion of residual volume (RV) was 47% of the total lung capacity, indicating hyperinflation (

Table 1).

Blood gas analysis was also normal: p02 12.33 kPa; pCO2 4,77 kPa; HCO3 22 mmol/L; pH 7.407; SpO2 97 %.

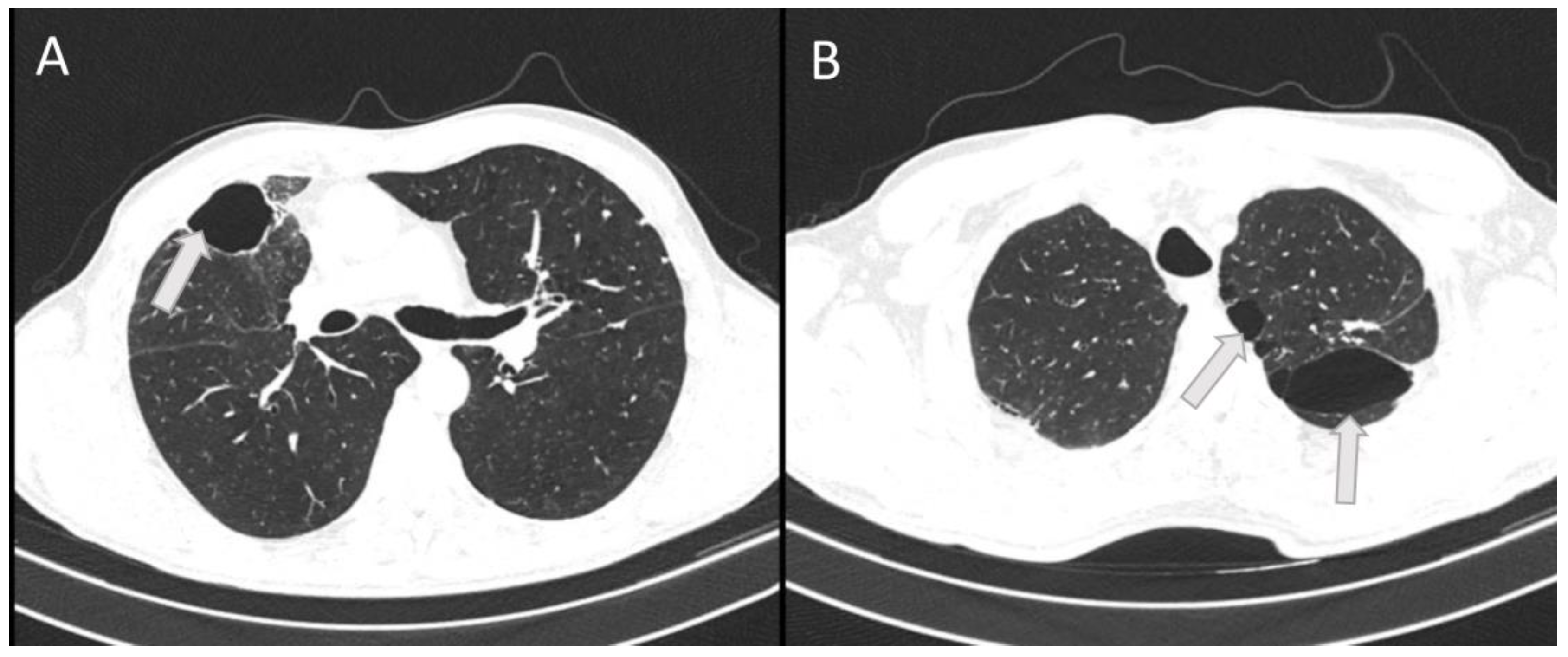

On this outpatient examination, a CT scan of the lung was performed which confirmed bullous changes in the left side of the lung (

Figure 4). Subjectively, he had discomfort when breathing and pain in the right chest. He complained about poor physical condition. His medical therapy prescribed by a pulmonologist was ipratropium bromide (Atrovent N, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co., Germany) 3 x 2 breaths.

3. Discussion

In this case report, we presented initial ventilation and supportive therapy in a patient with severe respiratory insufficiency after a blunt chest injury. The problem in treatment was the identification of the causative agent that was not confirmed by early microbiological diagnostics. Since V/Q mismatch was a consequence of lung injury, the treatment was focused on immediate management of the underlying condition itself, as well as simultaneous symptomatic treatment. The principles of management of hypoxemia include securing the airway, increasing inspired oxygen, identifying, and treating the pathogen bacteria, removal of secretions with intermittent bronchoscopies, and inclusion of respiratory support if necessary. A correction of hypoxemia, meticulous intravenous fluid management, and other supportive measures are crucial for improving the treatment outcome of patients with pneumonia [

8].

Pneumonia due to

S. maltophilia is not common. Treatment of this pathogen should be considered in cases of pneumonia with confirmed

S. maltophilia in sputum cultures, after broad-spectrum antibiotics were given for longer time period, and in patients with immunodeficiency with a high SOFA score [

9]. Since

S. maltophilia is intrinsically resistant to several types of antibiotics, it is potentially difficult to treat. In a retrospective study Shah and co-authors have demonstrated that combination therapy had similar rates of clinical efficacy and resistance development compared with monotherapy for

S. maltophilia pneumonia [

10]. The authors have observed that 30-day mortality was greater with combination therapy [

10]. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole remains the drug of choice, although

in vitro studies indicate that ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, minocycline, some of the new fluoroquinolones, and tigecycline may be useful agents [

11].

In addition to the infection treatment, maintaining adequate oxygenation was a significant clinical problem due to the large areas of crushed lung tissue that were not ventilated. An increase in inspired oxygen (FiO

2 100%), leads to an increase in alveolar oxygen tension (PAO

2) to greater than 100 mmHg, even in lung regions with very low alveolar ventilation. On the contrary, regions of the intra-pulmonary shunt are not ventilated, and those regions have an oxygen content equal to the mixed venous blood [

12].

In this patient, the maintenance of satisfactory saturation was achieved by a combination of high oxygen concentrations and moderate ventilation pressures in the most severe period of inflammation with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates that were gradually reduced. Barotrauma inevitably occurs with prolonged mechanical ventilation with high pressures [

13,

14]. We tried to reduce it by avoiding PEEP greater than 10 mmHg with a higher percentage of oxygen.

High ventilation pressures can improve oxygenation but may increase the risk of barotrauma in the healthy lung. Due to lower resistance, a larger volume of inhaled gas will be directed to healthy areas of the lungs [

13]. This is the reason that bullous changes after mechanical ventilation in our patient were also found in the lung areas that were less affected by trauma and inflammation.

Barotrauma can lead to the destruction of alveoli, parenchymal bleeding, and acute infiltration during the acute injury itself. After the resolution of the inflammatory reaction, due to the resulting residual fibrosis, these affected alveoli will not contribute to gas exchange. Impaired perfusion can also be expected in tissues after severe inflammation. The consequence of post-traumatic and post-inflammatory events in our patient was an increase in non-functional residual lung volume, with the development of emphysema, and decreased gas exchange function. A residual volume of 40% of the total lung volume measured in our patient is a poor prognostic sign [

15].

Reanalyzing this case, a shortcoming of this treatment could be that a viral respiratory panel was not analyzed on arrival. Although the treatment for most viruses is symptomatic, the recognition of the virus as the causative agent may have shortened the duration of antibiotic therapy.

In conclusion, both ventilatory and antibiotic therapy were needed to improve the patient's oxygenation and outcome after chest trauma with V/Q mismatch and pneumonia due to the resistant

S. maltophilia. It is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for resistant organisms such

as S. maltophilia infection, especially in patients who are not responding to empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics [

16]. Careful balancing between the oxygen ratio and ventilation pressure is needed to maintain oxygenation. Such an approach may alleviate the consequences of lung trauma with severe pulmonary infections.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Laboratory parameters in the patient with severe lung injury and pneumonia caused by

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.; Video S1: Lung CT after 8 days showing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: A.C., M.E., and S.K. did the manuscript draft; S.Š.C. and T.T. collected data; S.K. did data checking; A.C., S.K., N.N., J.G.T., and M.E. wrote the manuscript; A.C., T.T., S.Š.C., M.E., D.K., J.G.T., N.N., and S.K. approved and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Josip Juraj Strosmayer University, Medical Faculty; project number IP-26 (NN), and IP-19 (SK).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This report was approved by the ethics committee of the institution after the patient was discharged home (IRB no. R1/16208/2021) and the requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived.

Acknowledgments

Authors kindly acknowledge all staff members who were involved in the treatment and data acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jain, A.; Waseem, M. Chest Trauma. [Updated 2022 Aug 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-.

- Veysi, V.T.; Nikolaou, V.S.; Paliobeis, C.; Efstathopoulos, N.; Giannoudis, P.V. Prevalence of chest trauma, associated injuries and mortality: a level I trauma centre experience. Int Orthop. 2009, 33, 1425–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bein, T.; Reber, A.; Stjernström, H.; Metz, C.; Taeger, K.; Hedenstierna, G. Ventilation-perfusion ratio in patients with acute respiratory insufficiency. Der Anaesthesist. 1996, 45, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Wu, D.; Sykes, E.A.; et al. Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction: From Molecular Mechanisms to Medicine. Chest. 2017, 151, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagendran, J.; Stewart, K.; Hoskinson, M.; Archer, S.L. An anesthesiologist’s guide to hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: Implications for managing single-lung anesthesia and atelectasis. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 2006, 19, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moudgil, R.; Michelakis, E.D.; Archer, S.L. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Journal of Applied Physiology 2005, 98, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierhardt, M.; Pak, O.; Walmrath, D.; et al. Impairment of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in acute respiratory distress syndrome. European respiratory review: an official journal of the European Respiratory Society 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aston, S.J. Pneumonia in the developing world: Characteristic features and approach to management. Respirology (Carlton, Vic) 2017, 22, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imoto, W.; Yamada, K.; Kuwabara, G.; et al. In which cases of pneumonia should we consider treatments for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia? The Journal of hospital infection 2021, 111, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.D.; Coe, K.E.; el Boghdadly, Z.; et al. Efficacy of combination therapy versus monotherapy in the treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia pneumonia. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2019, 74, 2055–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicodemo, A.C.; Paez, J.I.G. Antimicrobial therapy for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases: official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology 2007, 26, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.B.; Celli, B. Venous admixture in COPD: pathophysiology and therapeutic approaches. COPD. 2008;5(6):376-381. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Li, X.; Mao, Z. Higher PEEP versus lower PEEP strategies for patients in ICU without acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care 2021, 67, 72–78. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajdev, K.; Spanel, A.J.; McMillan, S. Pulmonary Barotrauma in COVID-19 Patients With ARDS on Invasive and Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation. J Intensive Care Med. 2021 Sep;36, 1013-1017. Epub 2021 May 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, T.R.; Oh, Y.M.; Park, J.H.; et al. The Prognostic Value of Residual Volume/Total Lung Capacity in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2015 Oct;30, 1459-65. Epub 2015 Sep 12. PMID: 26425043; PMCID: PMC4575935. [CrossRef]

- Maraolo, A.E.; Licciardi, F.; Gentile, I.; Saracino, A.; Belati, A.; Bavaro, D.F. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative Efficacy of Available Treatments, with Critical Assessment of Novel Therapeutic Options. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).