Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

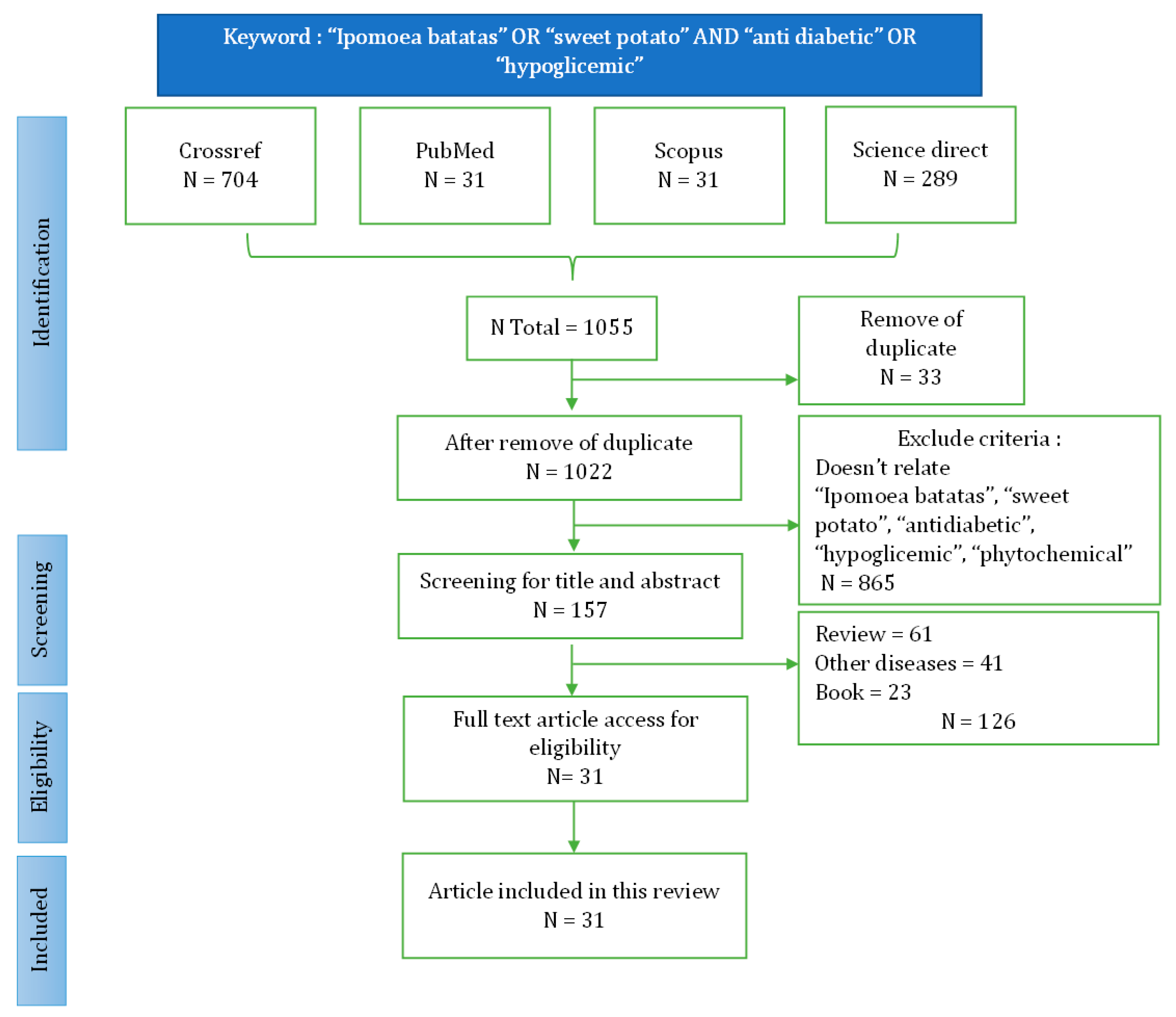

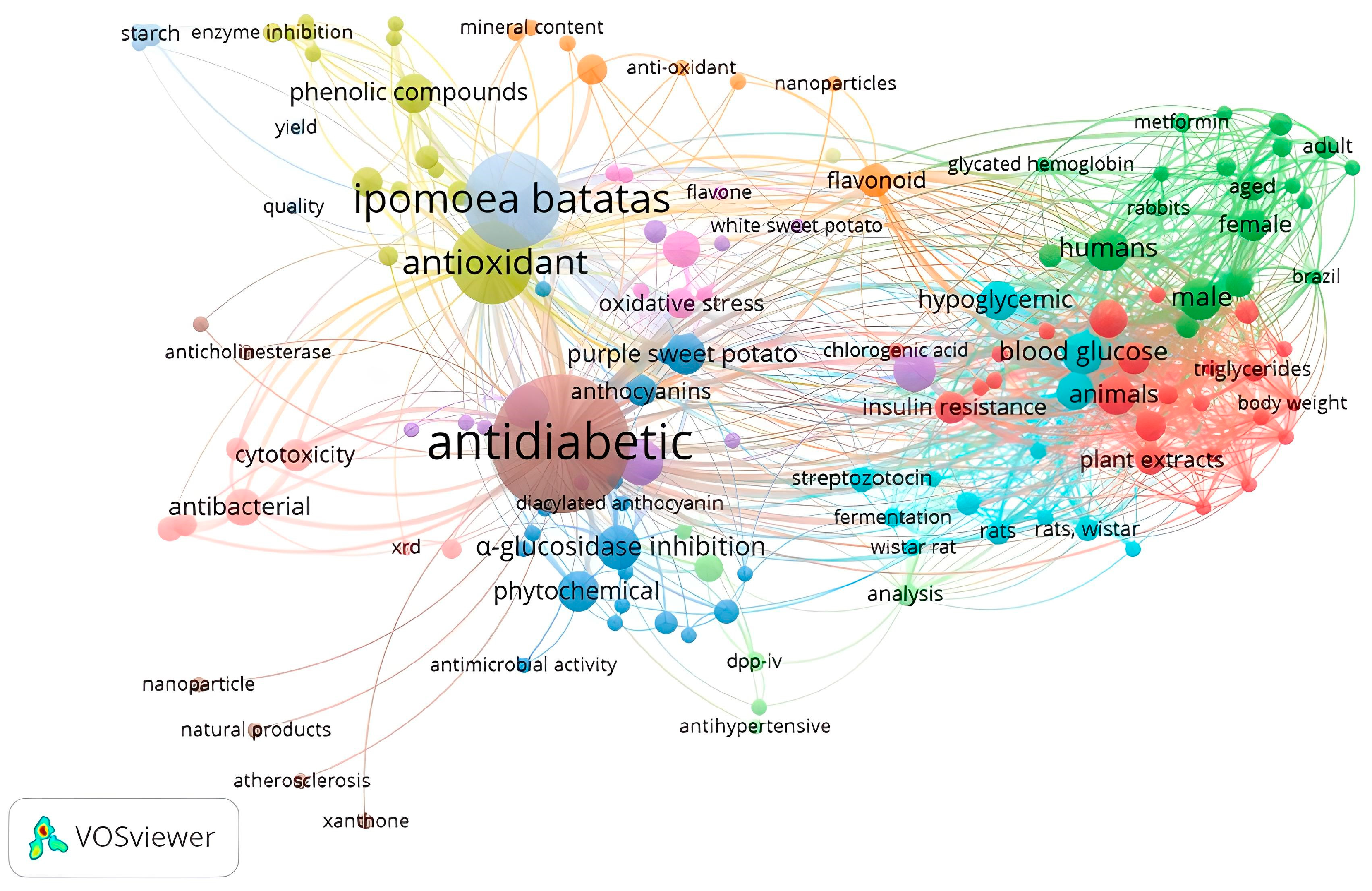

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Management

2.5. Strategy for Data Extraction

3. Results

The Literature Search

| No | Type/cultivar | Part of plant | Identified compound | Predictive Bioactive compound | Site of action | Mechanism pharmacology | Reference |

| [8]1 | IBL from cultivar Simon No.1(Beijing, China) | Leaves |

|

- | Pancreas |

|

[8] |

| - | Liver |

|

|||||

| - | Muscle |

|

|||||

| Leaves | - |

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[9] | ||

| Pancreas |

|

||||||

| 2 | Purple Ipomoea batatas were collected in Luzhu District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan |

Leaves |

|

Adipose |

|

[10] | |

| 3 | Ipomoea batatas were purchased from the local market India | Leaves |

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[11] | |

| 4 | Purple Ipomoea batatas were collected from Aan Village, Klungkung Regency, Bali Province, Indonesia |

Leaves |

|

Pancreas |

|

[12] | |

| 5 | Fresh orange-fleshed SPL (Jishu No. 16) collected from the farm in Yichun | Leaves |

|

|

Pancreas |

|

[13] |

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

|||||

| 6 |

Ipomoea batatas leaves were obtained by local farmer (Hebei province) in autumn |

Leaves |

|

Pancreas |

|

[14] | |

| 7 | Ipomoea batatas was cultivated in Slatina (central Croatia). | Leaves |

|

Pancreas |

|

[15] | |

| 8 | Ipomoea batatas L. collected in October 2015 in Anguillara Veneta (Northern Italy) | Leaves |

|

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[16] |

| Pancreas |

|

||||||

| 9 | Fresh leaves of Ipomoea batatas (family of clones B 00593) were harvested in July from the Bandungan plantation area in Central Java Indonesia. |

Leaves |

|

Pancreas |

|

[17] | |

| 10 | ‘Suioh,’ a IBL cultivar developed in Kumamoto prefecture, Japan | Leaves |

|

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[18] |

| 11 | Purple IBL | - |

|

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[19] |

| 12 | ‘Bophelo’ Orange-fleshed IBL cultivar | Tubers and leaves |

|

|

Pancreas |

|

[20] |

| Muscle |

|

||||||

| 13 | White potato Tainung No.10 | Tubers and leaves |

|

Muscle |

|

[21] | |

| 14 | Purple IBL (Cultivar Eshu No.12) were obtained from the Institute of Food Crops, Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences | Tubers |

|

|

Pancreas |

|

[22] |

| Liver |

|

||||||

| 15 | Purple IBL powder (cultivar Eshu No. 8) | Tubers | Diacylated anthocyanins |

|

Liver |

Enhancing secretion and sensitivity insulin eludidate mechanism:

|

[23] |

| 16 |

I. batatas (Linn.) Lam were purchased from Western Research Farm, National Root Crop Research Institute, Umudike, Abia state |

Tubers |

Flavonoid Terpenoid Tannin Phenol |

Pancreas |

|

[24] | |

| Gastrointestinal |

|

||||||

| Adipose |

|

||||||

| 17 | Purple IBL cv. Ayamurasaki were obtained from the Kyushu National Agricultural Experiment Station in Miyazaki prefecture (Japan) |

Tubers | Peonidin 3-O-[2-O-(6-O-E- feruloyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl)-6-O-E-caffeoyl-β-D-glucopyranoside]-5-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Gastrointestinal |

|

[25] | |

| 18 | Korean red skin IBL (Ib 1) and Korean pumpkin IBL (Ib 2) purchased from the market in Goyang, Republic of Korea |

Peel-off tuber |

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[26] | |

| 19 | White IBL (Caiapo) | Tubers |

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[27] | |

| Adipose |

|

[28] | |||||

| 20 | White-skinned sweet potato (WSSP) was purchased from the Kagawa, Japan, Prefectural Cooperative |

Tubers |

|

Adipose |

|

[29] | |

|

|

Muscle |

|

[30] | |||

|

Liver |

|

|||||

| 21 | Korean purple IBL (Shinzami, Saeungbone9, Saeungyae33, Gyebone108, Gyeyae2469, and Gyeyae2258) |

Tubers |

|

|

Liver |

|

[31] |

| 22 | Color-fleshed potatoes (Sinjami and Sinhwangmi) |

Tubers |

|

|

Adipose |

|

[32] |

| 23 | Ipomoea batatas was grown in Kagawa Prefecture, Japan | Tubers |

|

Pancreas |

|

[33] | |

| 24 | White-skinned sweet potato (WSSP) | Tubers |

|

Liver |

|

[34] | |

| 25 | Purple IBL Antin-3 cultivar from the BALITKABI Malang |

Tubers |

|

Pancreas |

|

[35] | |

| 26 | White-skinned sweet potatoes (WSSP) from the local market Faisalabad (Pakistan) | Tubers | Carotenoid | Pancreas |

|

[36] | |

|

Liver |

|

[37] | ||||

| 27 | Purple IBL from Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia | Tubers |

|

Gastrointestinal |

|

[38] |

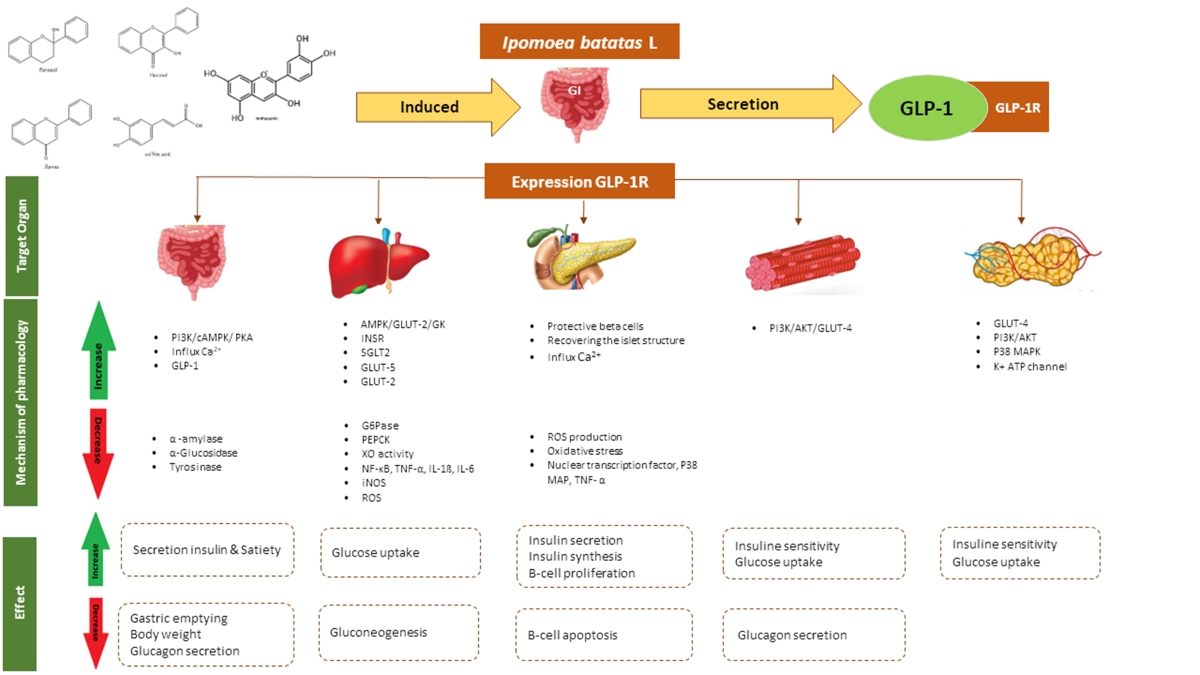

4. Discussion

4.1. Type or cultivar

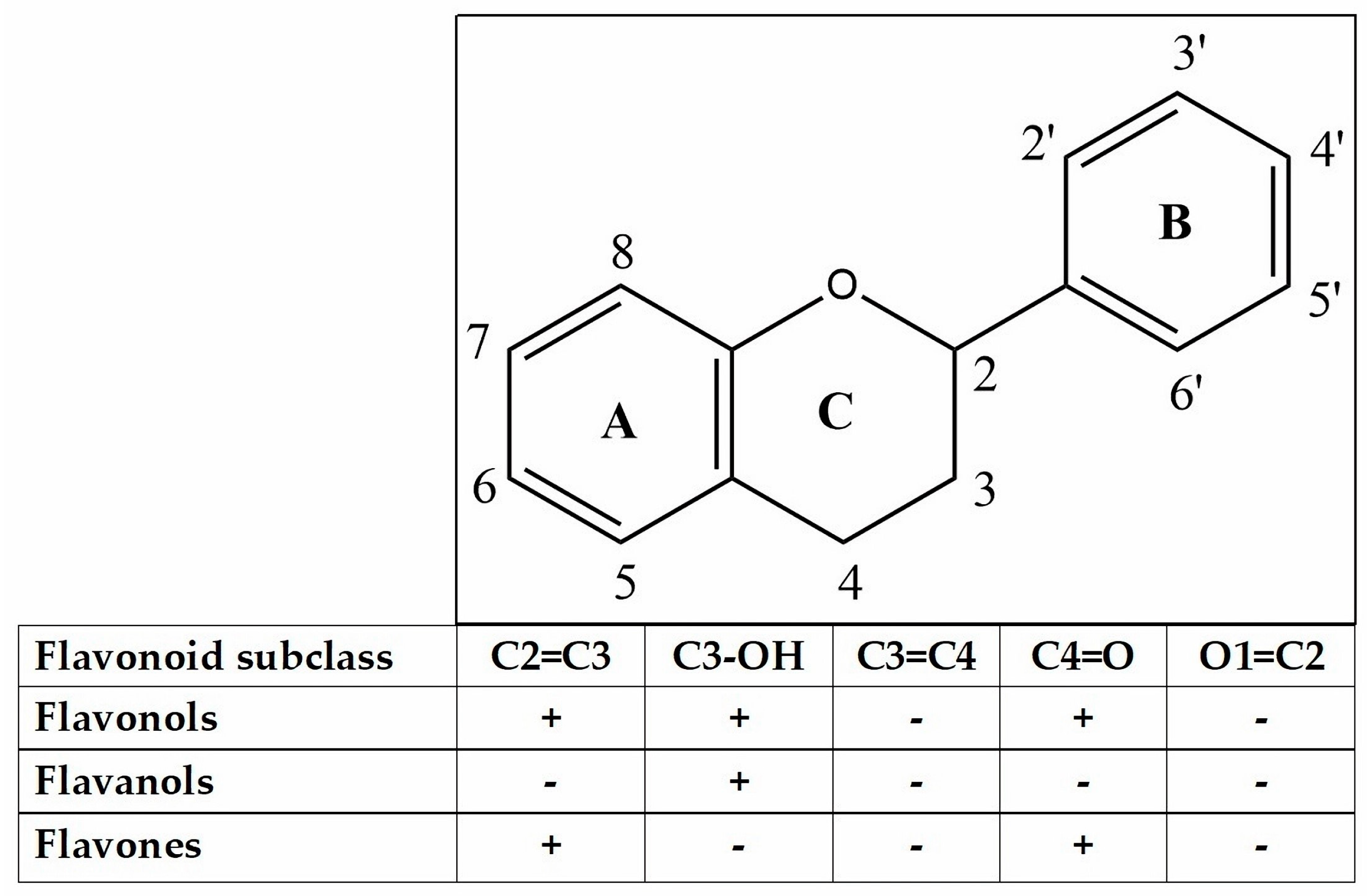

4.2. Parts of plant and phytochemical identified of IBL

4.3.1. Site of Action

4.3.2. Gastrointestinal Tract

- Regulation of carbohydrate metabolism

- b.

- Increase insulin secretion

4.3.3. Pancreas

- Inhibit apoptosis beta cell and recovering the islet structure through protective cell beta

- b.

- Suppression anti-inflammatory pathway

4.3.4. Liver

- Improving insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity by reducing glucose synthesis

4.3.5. Muscle

- Enhancing the absorption of glucose, secretion, and insulin sensitivity

4.3.6. Adiposa

- Increase glucose uptake and insulin secretion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- G. Danaei et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2·7 million participants. Lancet 2011, 378, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Ogurtsova et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 128, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. K. Al-Ishaq, M. Abotaleb, P. Kubatka, K. Kajo, and D. Büsselberg. Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: Cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels. Biomolecules, 2019, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. I. S. Arisanti, I. M. A. G. Wirasuta, I. Musfiroh, E. H. K. Ikram, and M. Muchtaridi. Mechanism of Anti-Diabetic Activity from Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas): A Systematic Review. Foods, 2023, 12, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. D. Müller et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab., 2019, 30, 72–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. Andersen, A. S. Christensen, F. K. Knop, and T. Vilsbøll. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Ugeskr. Laeger 2022, 181, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Hutton. et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: Checklist and explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 777–784. [CrossRef]

- D.Luo, T. Mu, and H. Sun. Sweet potato (: Ipomoea batatas L.) leaf polyphenols ameliorate hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 4117–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Luo, T. Mu, and H. Sun. Profiling of phenolic acids and flavonoids in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) leaves and evaluation of their anti-oxidant and hypoglycemic activities. Food Biosci., 2021, 39, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. L. Lee et al. Characterization of secondary metabolites from purple Ipomoea batatas leaves and their effects on glucose uptake. Molecules, 2016, 21, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Pal, S., A. S., Mishra, R. Maurya, and A. K. Srivastava. Antihyperglycemic and antidyslipidemic potential of ipomoea batatas leaves in validated diabetic animal models. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 7, 176–186, [Online]. Available: https://api.elsevier.com/content/abstract/scopus_id/84936852883. [Google Scholar]

- P. S. Yustiantara et al. Determination of TLC fingerprint biomarker of Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam leaves extracted with ethanol and its potential as antihyperglycemic agent. Pharmacia 2021, 68, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, Z.-C. Tu, T. Yuan, H. Wang, X. Xie, and Z.-F. Fu. Antioxidants and α-glucosidase inhibitors from Ipomoea batatas leaves identified by bioassay-guided approach and structure-activity relationships. Food chemistry 2016, 208, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. Zhao, Q. Li, L. Long, J. Li, R. Yang, and D. Gao, Antidiabetic activity of flavone from Ipomoea Batatas leaf in non-insulin dependent diabetic rats. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Zovko, R. Petlevski, Z. Kaloðera, and K. Plantak, Antioxidant and antidiabetic activity of leaves of Ipomoea batatas grown in continental Croatia. 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. Zengin et al. Chemical characterization, antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory activity, and enzyme inhibition of Ipomoea batatas L. leaf extracts. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Novrial, S. Soebowo, and P. Widjojo. Protective Effect of Ipomoea batatas L Leaves Extract on Histology of Pancreatic Langerhans Islet and Beta Cell Insulin Expression of Rats Induced by Streptozotocin. Molekul, 2020, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Nagamine et al. Dietary sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) leaf extract attenuates hyperglycaemia by enhancing the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2309–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X. Sui, Y. Zhang, and W. Zhou. In vitro and in silico studies of the inhibition activity of anthocyanins against porcine pancreatic α-amylase. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 21, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Ayeleso, K. Ramachela, and E. Mukwevho. Aqueous-Methanol Extracts of Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) Ameliorate Oxidative Stress and Modulate Type 2 Diabetes Associated Genes in Insulin Resistant C2C12 Cells. Molecules, 2018, 23, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. K. Shih, C. M. Chen, V. Varga, L. C. Shih, P. R. Chen, and S. F. Lo. White sweet potato ameliorates hyperglycemia and regenerates pancreatic islets in diabetic mice. Food Nutr. Res., 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Jiang, X. Shuai, J. Li, N. Yang, S. Deng, L., Li, and J. He. Protein-Bound Anthocyanin Compounds of Purple Sweet Potato Ameliorate Hyperglycemia by Regulating Hepatic Glucose Metabolism in High-Fat Diet/Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1596–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Shen, Y. Yang, J. Zhang, L. Feng, and Q. Zhou. Diacylated anthocyanins from purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) attenuate hyperglycemia and hyperuricemia in mice induced by a high-fructose/high-fat diet. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2023, 24, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. S. Okafor, C. Ezekwesili, N. Mbachu, K. C. Onyewuchi, and U. C. Ogbodo, Anti-diabetic Effects of the Aqueous and Ethanol Extracts of Ipomoea batatas Tubers on Alloxan Induced Diabetes in Wistar Albino Rats. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Matsui et al., Anti-hyperglycemic effect of diacylated anthocyanin derived from Ipomoea batatas cultivar Ayamurasaki can be achieved through the alpha-glucosidase inhibitory action., 2002, 50. [CrossRef]

- G. Das, J. K. Patra, N. Basavegowda, C. N. Vishnuprasad, and H.-S. H.-S. S. Shin, Comparative study on antidiabetic, cytotoxicity, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using outer peels of two varieties of Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Sakuramata, H. Oe, S. Kusano, and O. Aki, Effects of combination of Caiapo® with other plant-derived substance on anti-diabetic efficacy in KK-Ay mice. 2004. [CrossRef]

- B. Ludvik, B. Neuffer, and G. Pacini. Efficacy of Ipomoea batatas ( Caiapo ) on Diabetes Control in Type 2 Diabetic. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kusano, S. Tamasu, and S. Nakatsugawa. Effects of the White-Skinned Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) on the Expression of Adipocytokine in Adipose Tissue of Genetic Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2005, 11, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Kinoshita, T. Nagata, F. Furuya, M. Nishizawa, and E. Mukai. White-skinned sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) acutely suppresses postprandial blood glucose elevation by improving insulin sensitivity in normal rats. Heliyon 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- H. Jang, H. Kim, and S. Kim. In vitro and in vivo hypoglycemic effects of cyanidin 3-caffeoyl-p-hydroxybenzoylsophoroside-5-glucoside, an anthocyanin isolated from purple-fleshed sweet potato. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. H.-J. Kim et al. Anti-obesity activity of anthocyanin and carotenoid extracts from color-fleshed sweet potatoes. J. Food Biochem., 2020, 44. [CrossRef]

- Niwa, T. Tajiri, and H. Higashino. Ipomoea batatas and Agarics blazei ameliorate diabetic disorders with therapeutic antioxidant potential in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr., 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Oki, S. Nonaka, and S. Ozaki. The effects of an arabinogalactan-protein from the white-skinned sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) on blood glucose in spontaneous diabetic mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 596–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. A. Wicaksono, Yunianta, and T. D. Widyaningsih. Anthocyanin extraction from purple sweet potato cultivar antin-3 (Ipomoea batatas L.) using maceration, microwave assisted extraction, ultrasonic assisted extraction and their application as anti-hyperglycemic agents in alloxan-induced wistar rats. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2016, 9, 181–192, [Online]. Available: https://api.elsevier.com/content/abstract/scopus_id/84963724810. [Google Scholar]

- S. Kamal et al. Anti-diabetic activity of aqueous extract of Ipomoea batatas L. in alloxan induced diabetic Wistar rats and its effects on biochemical parameters in diabetic rats. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 31, 1539–1548, [Online]. Available: https://api.elsevier.com/content/abstract/scopus_id/85064116246. [Google Scholar]

- N. Akhtar, M. Akram, M. Daniyal, and S. Ahmad. Evaluation of antidiabetic activity of Ipomoea batatas L. extract in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2018, 32. [CrossRef]

- S. Nurdjanah,. I., S. Astuti, and N. Yuliana. Inhibition Activity of α-amylase by Crude Acidic Water Extract from Fresh Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) and its Modified Flours. Asian Journal of Scientific Research, 2020, 13, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Jiang et al. Protein-Bound Anthocyanin Compounds of Purple Sweet Potato Ameliorate Hyperglycemia by Regulating Hepatic Glucose Metabolism in High-Fat Diet/Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1596–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Akhtar et al. Anti-diabetic activity of aqueous extract of Ipomoea batatas L. in alloxan induced diabetic Wistar rats and its effects on biochemical parameters in diabetic rats. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Sakuramata, H. Ohe, and S. Kusano. Anti-diabetic effects of combination of white skinned sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) with loquat leaf extract. J. Tradit. Med. 2004, 21, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Cremonini, E. Daveri, A. Mastaloudis, and P. I. Oteiza. (-)-Epicatechin and Anthocyanins Modulate GLP-1 Metabolism: Evidence from C57BL/6J Mice and GLUTag Cells. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. P. Hjørne, I. M. Modvig, and J. J. Holst. The Sensory Mechanisms of Nutrient-Induced GLP-1 Secretion. Metabolites, 2022, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. E. Kuhre, C. R. Frost, B. Svendsen, and J. J. Holst. Molecular mechanisms of glucose-stimulated GLP-1 secretion from perfused rat small intestine. Diabetes 2015, 64, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiang et al. GLP-1 improves adipocyte insulin sensitivity following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Front. Pharmacol., 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Wu et al. GLP-1 regulates exercise endurance and skeletal muscle remodeling via GLP-1R/AMPK pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res., 2022, 1869. [CrossRef]

- O. I. Omotuyi et al. Flavonoid-rich extract of Chromolaena odorata modulate circulating GLP-1 in Wistar rats: computational evaluation of TGR5 involvement. 3 Biotech 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- A. W. Wang, Yao, H. Alkhalidy, J. Luo, E. Moomaw, A. N. P., and D. Liu. Flavone Hispidulin Stimulates Glucagon-Like peptide-1 secretion and Ameliorates Hyperglycemia in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 2020, 64, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. S. de Castilho, T. B. Matias, K. P. Nicolini, and J. Nicolini. Study of interaction between metal ions and quercetin. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2018, 7, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Horáková. Flavonoids in prevention of diseases with respect to modulation of Ca-pump function. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2011, 4, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. F. de Almeida et al. Phytochemical profile, in vitro activities, and toxicity of optimized Eugenia uniflora extracts. Bol. Latinoam. y del Caribe Plantas Med. y Aromat. 2023, 22, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Oh and H. S. Jun. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Barber, M. J. Houghton, and G. Williamson. Flavonoids as human intestinal α-glucosidase inhibitors. Foods 2021, 10, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Pal, S. Gautam, A. Mishra, R. Maurya, and A. K. Srivastava. Antihyperglycemic and antidyslipidemic potential of ipomoea batatas leaves in validated diabetic animal models. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 7, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- J. Pan et al. Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 by Flavonoids: Structure–Activity Relationship, Kinetics and Interaction Mechanism. Front. Nutr., 2022, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. M. Ackermann and M. Gannon. Molecular regulation of pancreatic β-cell mass development, maintenance, and expansion. J. Mol. Endocrinol., 2007, 38, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. M. A. G. Wirasuta. Chemical profiling of ecstasy recovered from around Jakarta by High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)-densitometry. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 2, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Xi, T. Mu, and H. Sun. Preparative purification of polyphenols from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) leaves by AB-8 macroporous resins. Food Chemistry, vol. 172. Elsevier BV, pp. 166–174, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Olivier, B. E. van Wyk, and F. R. van Heerden. The chemotaxonomic and medicinal significance of phenolic acids in Arctopus and Alepidea (Apiaceae subfamily Saniculoideae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2008, 36, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Masek, E. Chrzescijanska, and M. Latos. Determination of antioxidant activity of caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid by using electrochemical and spectrophotometric assays. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 10644–10658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. A. Wicaksono, Yunianta, and T. D. Widyaningsih. Anthocyanin extraction from purple sweet potato cultivar antin-3 (Ipomoea batatas L.) using maceration, microwave assisted extraction, ultrasonic assisted extraction and their application as anti-hyperglycemic agents in alloxan-induced wistar rats. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2016, 9, 181–192, [Online]. Available: https://api.elsevier.com/content/abstract/scopus_id/84963724810. [Google Scholar]

- R. Dhanya. Quercetin for managing type 2 diabetes and its complications, an insight into multitarget therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146. [CrossRef]

- X. C. Y. L. Xiaoqian Dai, Ye Ding, Zhaofeng Zhang. Quercetin and quercitrin protect against cytokine-induced injuries in RINm5F β-cells via the mitochondrial pathway and NF-κB signaling. Inflamm. Insul. Prod. β-cells Mitochondrial apoptosis Quercetin Quercitrin 2012, 31, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- I. M. A. G. Wirasuta, N. M. A. R. Dewi, K. D. Cahyadi, L. P. M. K. Dewi, N. M. W. Astuti, and I. N. K. Widjaja. Studying systematic errors on estimation decision, detection, and quantification limit on micro-TLC. Chromatographia, 2013, 76, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Ben-Shlomo et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 reduces hepatic lipogenesis via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Solverson. Anthocyanin Bioactivity in Obesity and Diabetes : and Periphery. Cells 2020, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- T. Wang et al. Baicalin and its metabolites suppresses gluconeogenesis through activation of AMPK or AKT in insulin resistant HepG-2 cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 141, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Chen, S. Tan, T. Ren, H. Wang, X. Dai, and H. Wang. Polyphenol from Rosaroxburghii Tratt Fruit Ameliorates the Symptoms of Diabetes by Activating the P13K/AKT Insulin Pathway in db/db Mice. Foods, 2022, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Y. Song, Y. Aihara, T. Hashimoto, K. Kanazawa, and M. Mizuno. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate induces secretion of anorexigenic gut hormones. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 2015, 57, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al. Plasma adiponectin levels and type 2 diabetes risk: A nested case-control study in a Chinese population and an updated meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Yanai and H. Yoshida. Beneficial Effects of Adiponectin on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerotic Progression : Mechanisms and Perspectives. pp. 1–25, 2019. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).