1. Introduction

Small-scale family horticultural production in Nariño plays a crucial role in supplying fresh food to the population in Colombia's major cities. Among the most representative crops are lettuce and broccoli. Nariño ranks second in the country for lettuce production (26% of cultivated area, 46,494 tons per year) and third for broccoli (15% of cultivated area, 2,422 tons per year) [

1]. Most of this production relies on external inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides, whose residual effects can negatively impact both producers and consumers [

2]. Despite the implementation of regulations for organic agricultural products since 2006 [

3], the progress of organic farming in Colombia remains limited, with estimates indicating that only 1% of cultivated areas are certified as organic [

4]. Subsequently, Colombian public policy, through Resolution 464, identifies agroecology as an alternative to enhance the sustainability of agriculture and food systems with the aim of increasing the availability of more nutritious and healthier food [

5]. The implementation of this policy requires support for agroecological transition processes, which involve a socio-ecological reconfiguration of agroecosystems to produce in accordance with agroecological principles [

6]. So far, these initiatives have primarily been driven by peasant organizations, making it imperative to generate new knowledge that supports the reconfiguration of agroecosystems and promotes the adoption of traditional practices, such as agricultural diversification, to reduce input dependence and mitigate the risk of productivity loss that producers may face during the transition [

7].

The ecological imbalance generated by the expansion of monocultures and the intensive use of agrochemicals leads to biodiversity loss in agroecosystems and the ecosystem services that impact crop production, such as pollination and pest regulation [

8,

9,

10,

11]. In this context, it is imperative to promote sustainable agricultural production that harmonizes food production and biodiversity conservation. As an alternative, ecological intensification is proposed, aiming to redesign agroecosystems with the goal of enhancing the functions and services of nature at both field and landscape scales to improve agricultural productivity using schemes based on ecological processes that support production, such as pest regulation, nutrient cycling, and pollination [

12,

13].

The intentional addition of functional biodiversity to crop systems at multiple spatial and/or temporal scales, or agricultural diversification, has the potential to reduce the negative impacts of intensive production while simultaneously enhancing the resilience and sustainability of agroecosystems [

14,

15]. This process involves the introduction of plants within the crop, known as "crop diversification" (e.g., rotations, polyculture, companion planting, intercropping, cover crops, green manure), or the introduction of non-cultivated plants at the field edges, referred to as "non-crop diversification" (e.g., flower strips, grass margins, inter-row vegetation management, scattered trees, etc.) [

16]. Functional diversity below ground can also be increased through the inoculation of beneficial microorganisms (mycorrhizae, plant growth-promoting bacteria) or by creating environments conducive to microorganisms through reduced tillage and the addition of organic matter [

16]. Increasing functional diversity regenerates biotic interactions that support ecosystem services such as biological pest control and pollination [

14,

17,

18]. The same applies to nutrient cycling, soil fertility, and water regulation [

18]. In this way, agricultural diversification can enhance resource use efficiency and improve production stability in agroecosystems over time.

The planting of flower strips at the edges of crops and intercropping practices favors the provision of ecosystem services such as pest regulation and pollination by improving resource use efficiency and enhancing soil water retention capacity, as well as increasing habitat diversity and quality for beneficial insects [

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, there are knowledge gaps regarding how these practices translate into improved crop yields.

One way to determine the response of this interaction between crops is through an indicator calculation based on the biomass generated by each species, comparing the yield between monoculture and polyculture, thus obtaining the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER)[

23]. This index estimates the efficiency of an intercropping system in comparison to monoculture; when the value is >1, it indicates that the combined yield of the associated crops is greater than in monoculture, while a value <1 suggests that the association is less favorable than monoculture production [

23]. The same principle is used to measure the level of competition among the species involved in the association, for which the Competitive Ratio (CR) is estimated. When values are <1, they indicate a positive effect, showing limited competition among the plants involved, whereas values >1 indicate a negative level of competition in the association [

23]. As an example, lettuce, when associated with rocket, has an LER value of 1.41 [

21]. In association with carrots, this index is 1.41, and when ground cover is implemented, it is 1.31 [

22], indicating that lettuce is a plant well-suited to intercropping. Broccoli shows a similar response when associated with beans, with an LER ranging from 1.13 to 1.44, depending on the proportions of plants used for the intercropping [

24].

Although agricultural diversification has been extensively studied, there are knowledge gaps regarding the effects of combining diversification strategies on the productivity of crops, particularly in the Colombian Andean highlands. For this reason, the aim of our study is to quantify the effects of establishing flower strips in broccoli and lettuce crops, both in association and as monocultures, under organic and conventional management schemes, with a focus on their production and economic aspects. Our hypothesis is that the introduction of aromatic strips together with intercropping will enhance crop yields and pest and disease regulation in diversified crops compared to conventional monoculture production.

Our results indicate that the combination of productive diversification strategies improves crop performance, as the introduction of flower strips at the crop edges positively impacts the LER of the intercropping between broccoli and lettuce. No effects of diversification strategies on crop damage were observed, suggesting that the observed effect may be attributed to factors such as microclimate and soil water retention, aspects that should be further investigated in future research.

2. Materials and Methods

Two experimental evaluation cycles were conducted, one in the second semester of 2022 and another in the first semester of 2023, at the Obonuco Research Center - Agrosavia, located in Pasto, Nariño, Colombia (1° 11' 52.55" N; 77° 18' 25.67" W). The location corresponds to the Altiplano subregion of Nariño at an altitude of 2841 m.a.s.l., with an average annual temperature of 12.9 °C. Based on these two climate variables and according to the Caldas-Lang classification [

25], it is categorized as a cold semi-humid climate (Fsh). The location had an average annual precipitation of 840 mm.

The experimental design corresponded to a randomized complete block design in a factorial arrangement with four replications. The experimental plot size for the first cycle was 15 m2, and for the second cycle, it was 12 m2.

In the first cycle, the treatments evaluated in the first factor were aromatic flower strips (I) and control (II). The second factor corresponded to: (I) Monoculture lettuce (62,500 plants.ha-1), (II) Monoculture broccoli (40,000 plants.ha-1), (III) Lettuce-broccoli intercropping – D1 (37,800 plants.ha-1), (IV) Lettuce-broccoli intercropping – D2 (50,000 plants.ha-1), (V) Lettuce-broccoli intercropping – D3 (62,500 plants.ha-1).

In the second cycle, the first factor remained, aromatic flower strips (I) and control (II), while the second factor corresponded to the crop management system, organic (I), and conventional (II). The planting density for the second evaluation cycle was determined in consensus with the producers during a workshop. A density of 50,000 plants per hectare (ha-1) was chosen based on factors such as the production area, land use, feasibility of farming practices, improvements in productivity, and implications for marketing. The plant species evaluated were lettuce (Lactuca sativa) variety Coolguard and broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) hybrid Legacy. The flower strip was established with the species Chamaemelum nobile (Chamomile), Calendula officinalis (Marigold), Mentha sp. (Mint), Thymus vulgaris (Thyme), and Artemisia absinthium (Wormwood). These species were selected because they are widely used by agroecological producers in the region to enhance natural biological pest control in their gardens.

Sanitary management for the first evaluation cycle was carried out organically, using plant extracts of Allium sativum and Capsicum annuum (garlic and chilli), Azadirachtin indica (neem), wormwood hydrosol (Artemisia absinthium), tea tree extract (Melaleuca alternifolia), elicitors, biocontrol agents (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Agrobacterium radiobacter, Bacillus pumilus, and Trichoderma koningiopsis), entomopathogens (Beauveria bassiana, Metharhizium anisopliae, Lecanicillium lecanii, Bacillus thuringiensis), and mineral products based on sulfur and calcium. Soil fertilization was done with 5 t ha-1 of rock phosphate and 15 t ha-1 of vermicompost, with supplementary foliar fertilization based on boron, organic carbon, nitrogen, and calcium. In the second cycle, for the organically managed plots, the same products as described for the first cycle were used. While, for conventional management, fungicides with active ingredients such as azoxystrobin, captan, flutriafol, carbendazim, metalaxil + propamocarb; insecticides based on cyromazine, acephate, permethrin, emamectin benzoate, diflubenzuron + lambda-cyhalothrin, and metaldehyde for slug management were applied in rotation. Nutrition was provided using mineral fertilizers with an application equivalent to 88, 50, and 50 kg ha-1 of N, P2O5, and K2O, respectively for lettuce, and 120, 150, and 210 kg ha-1 of N, P2O5, and K2O for broccoli. Minor edaphic elements were supplemented at a rate of 96 kg ha-1 of commercial product, and nutrition was further complemented with foliar fertilization based on phosphorus, boron, and calcium.

The soil's chemical characteristics in the experimental trial area were as follows: pH (6.18); organic matter (3.41%); in mg kg-1 for P (77.54), S (6.95), Fe (335.61), B (0.46), Mn (5.69), Cu (2.45), and Zn (3.61); in cmol(+) kg-1 for K (1.01), Ca (6.06), and Mg (1.16). There was no exchangeable acidity. The bulk density was 1.92 g cm-3.

Evaluated variables:

Dry matter: Six plants per plot were collected at harvest to determine accumulated above-ground biomass; plant tissues were dried at 65°C for 72 hours.

Yield: The useful plot of each experimental unit was harvested to determine the experimental yield (t ha-1).

Pest and disease infestation: Ten plants per useful plot in monoculture (same species) and ten plants in intercropping (5 plants of each species) were assessed for the presence of diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella), slugs (Deroceras sp. and Milax spp.), and incidence of lettuce rot (Sclerotinia spp).

Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) and Competitive Ratio (CR): Determined using data from the yields of the associated crops and their monocultures. The following formula was applied:

LER: Land Equivalent Ratio

YAL: Yield of associated lettuce

YML: Yield of monoculture lettuce

YAB: Yield of associated broccoli

YMB: Yield of monoculture broccoli

R: Competitive Ratio

PRLETTUCE: Proportion of lettuce in the crop

PRBROCCOLI: Proportion of broccoli in the crop

Economic analysis

The net income was estimated for broccoli and lettuce crops in both planting systems (monoculture and intercropping). The average yields obtained from each treatment were used to calculate the net income (NI). In the first cycle, the selling price per kilogram of broccoli and lettuce corresponds to the average price of the 19last year in two local markets in Nariño [

26]. The NI in the second cycle was calculated based on the average prices in local markets for chemical management and the prices in organic stores for organic management [

26,

27]. For the determination of production costs (PC), plot leasing, labor, plant material, and input costs were considered. The profit (COP ha

-1) was calculated as the difference between NI and PC. In treatments where flower strips were implemented, an additional cost of 5% of direct costs (inputs and labor) was estimated for the establishment and maintenance of flower strips.

3. Results

First experimental cycle

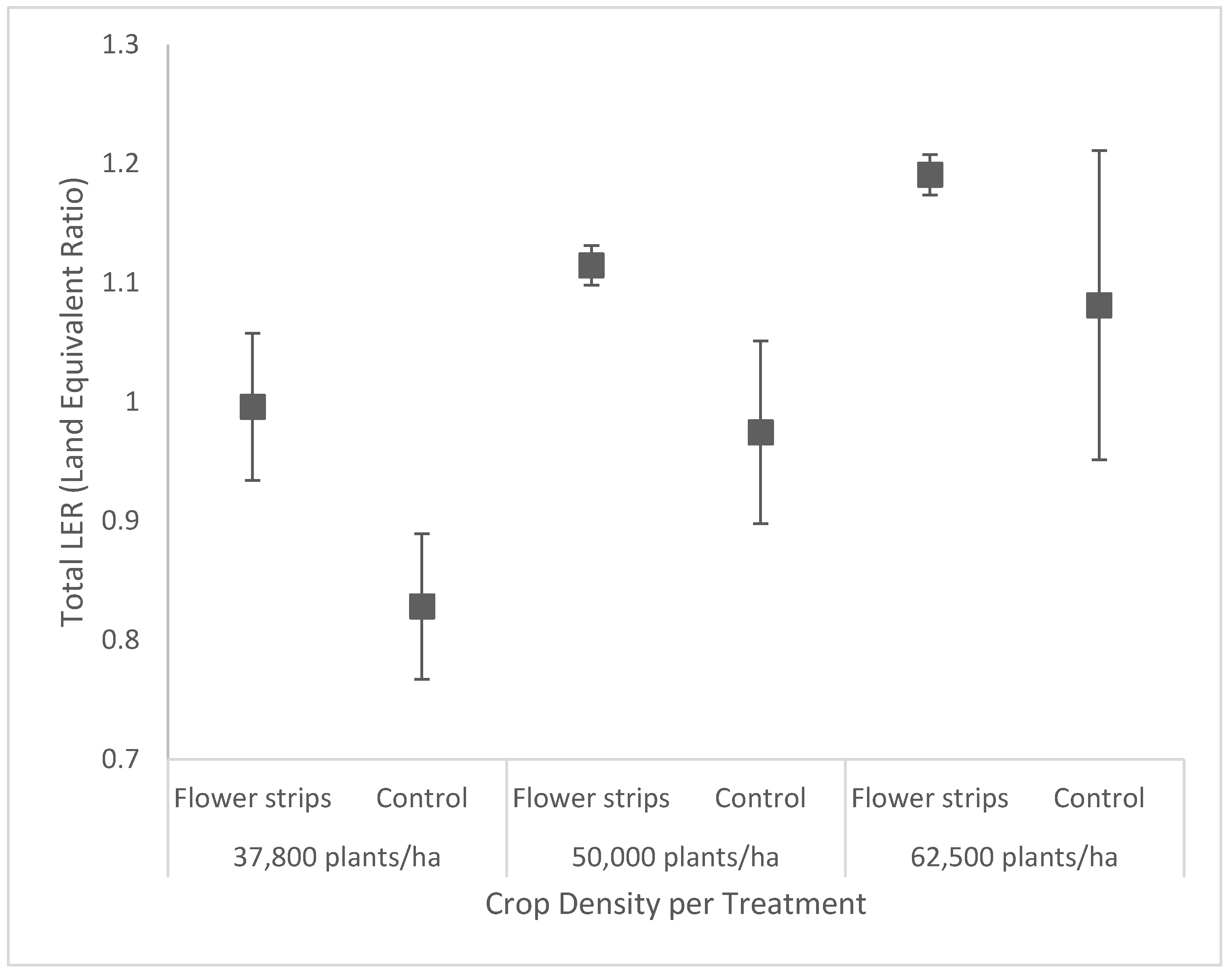

The Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) significantly differed between crops with and without flower strips and among intercrop planting densities. Land productivity efficiency in the broccoli-lettuce association increased with the presence of flower strips in all three planting densities evaluated (

Figure 1).

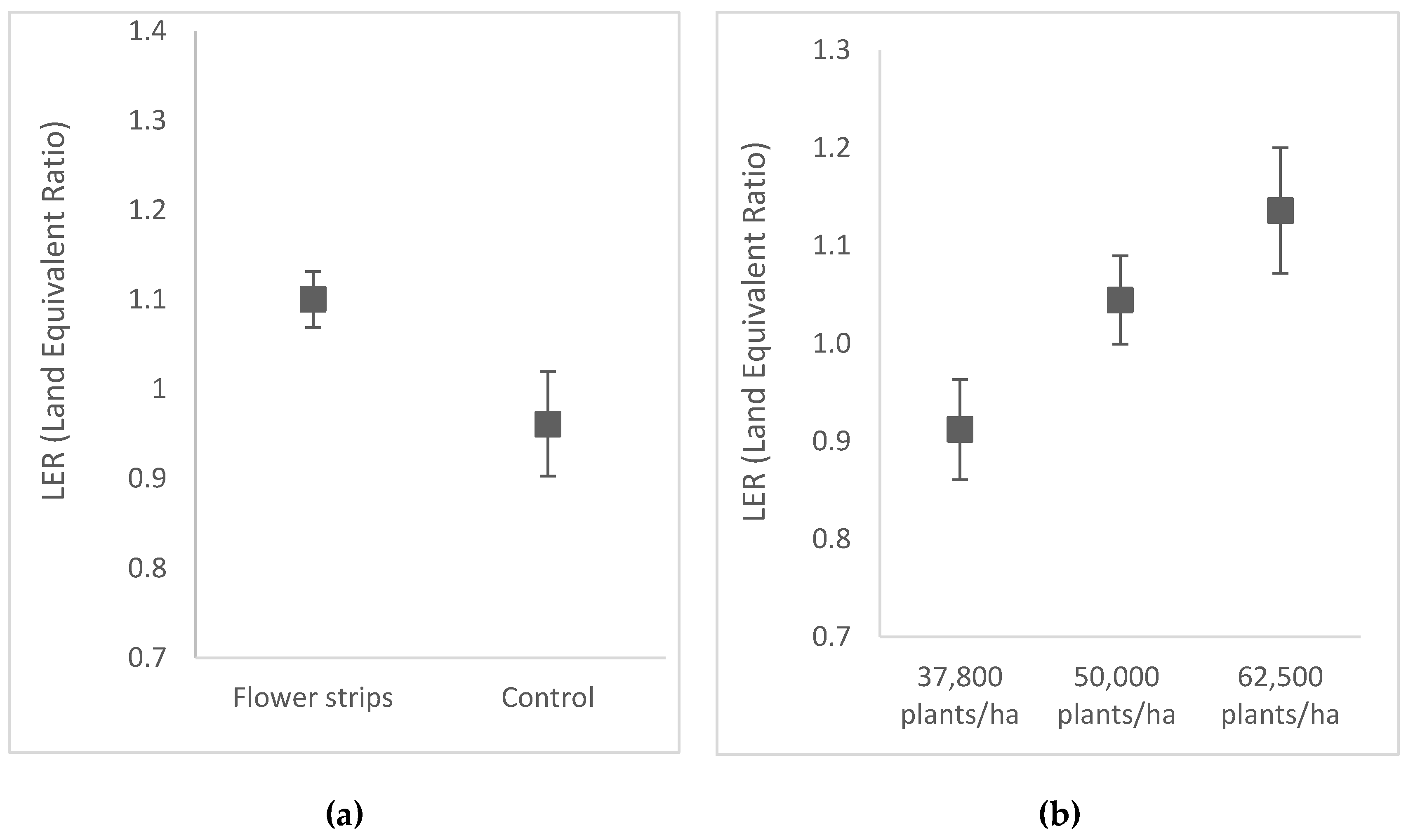

On average, the LER in plots with flower strips was 1.10 compared to 0.96 in plots without these strips (

Figure 2A). Regarding planting densities, the productive efficiency of the intercrop increased in direct proportion with the planting density: at a density of 37,800 plants.ha

-1., the LER was 0.91, at 50,000 plants.ha

−1., the LER was 1.04, and at 62,500 plants.

ha−1, the LER was 1.14 (

Figure 2B). The interaction between the evaluated factors was not significant (

Supplementary Materials, Table S1).

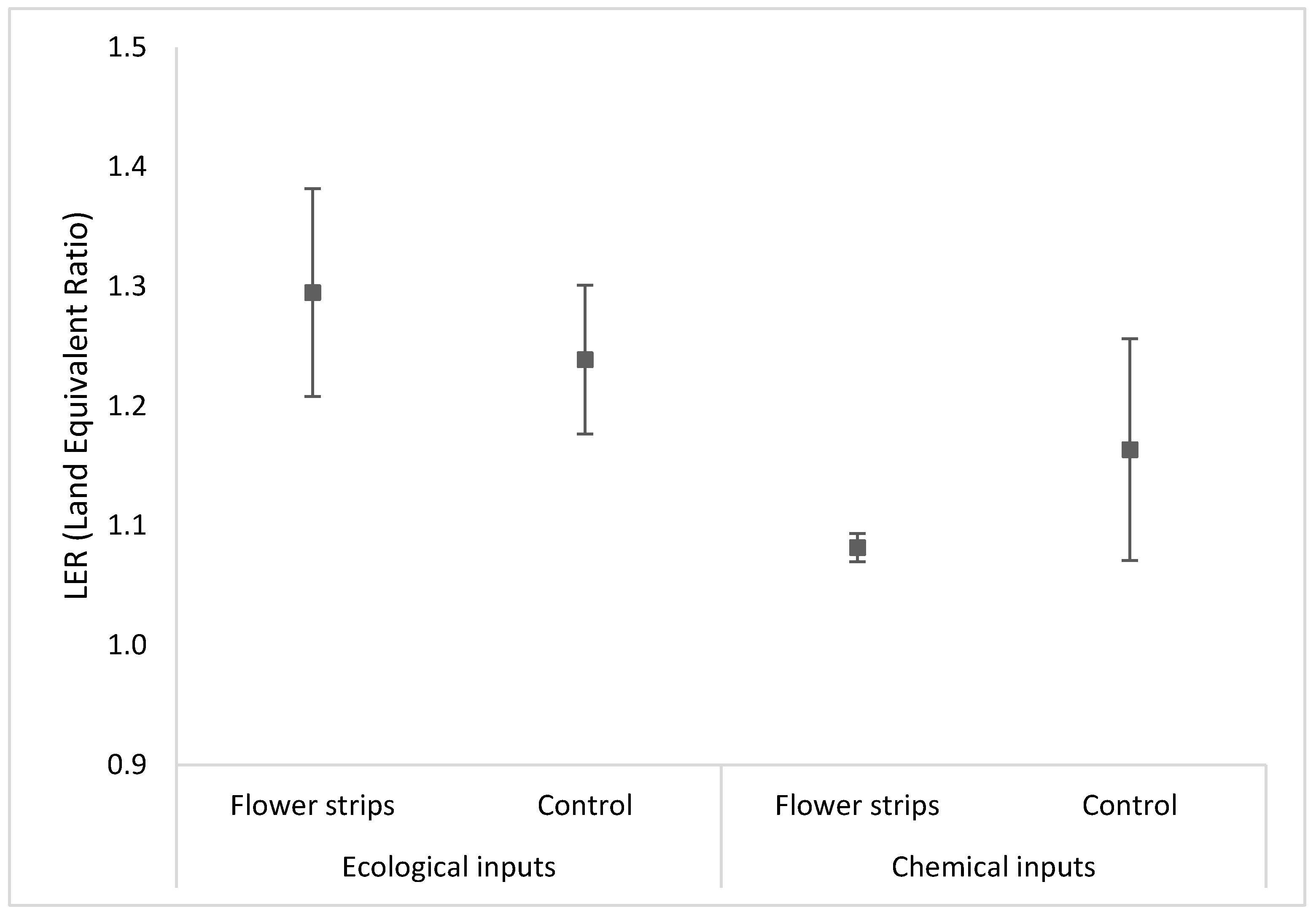

Second experimental cycle

The broccoli-lettuce intercropping increased land use efficiency in all cases (LER > 1). However, no significant differences were observed between agronomic management types or between plots with and without flower strips (

Supplementary Material, Table S2). In plots under organic management with aromatic borders, the LER was 1.29, while in plots without flowers, it was 1.23. Conversely, in the management with chemical input, the LER was 1.08 when flower strips were introduced and 1.16 without them (

Figure 3).

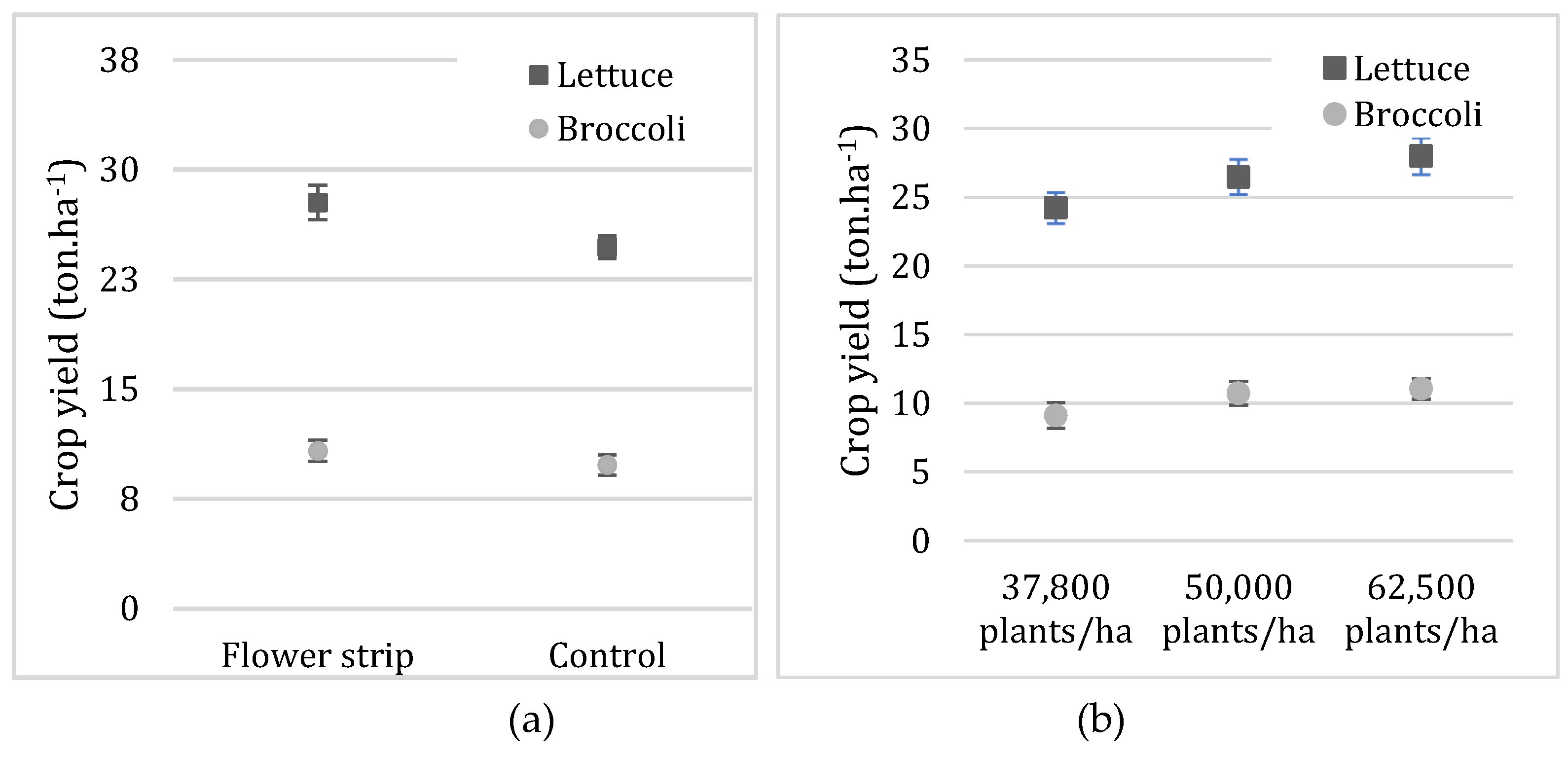

Crop yield

First experimental cycle

The yield of both crops in intercropping and monoculture was higher in plots with flower strips, except for broccoli planted at high densities (

Table 1). Lettuce associated with broccoli showed an increase in yield with the presence of flower strips by 3.1 t

ha−1 (

Figure 4A), while in the same association, broccoli did not exhibit a statistically significant increase (

Figure 4A). Regarding the effect of plant density in the intercrop, for lettuce, a positive effect was observed, with a difference of 3.77 t

ha−1 between planting in intercropping at 62,500 and 37,800 plants.ha

-1(

Supplementary Material, Table S3). In contrast, for broccoli, statistical differences in yields were evident from 50,000 plants.

ha−1 compared to 37,800 plants.

ha−1, with an average yield of 10.7 t

ha−1 and 9.12 t

ha−1, respectively (

Supplementary Material, Table S4). This indicates that broccoli in intercropping from 50,000 plants.

ha−1 did not increase yields, which could be related to a suppressive effect on head weight or size as plant density increased (

Figure 4B).

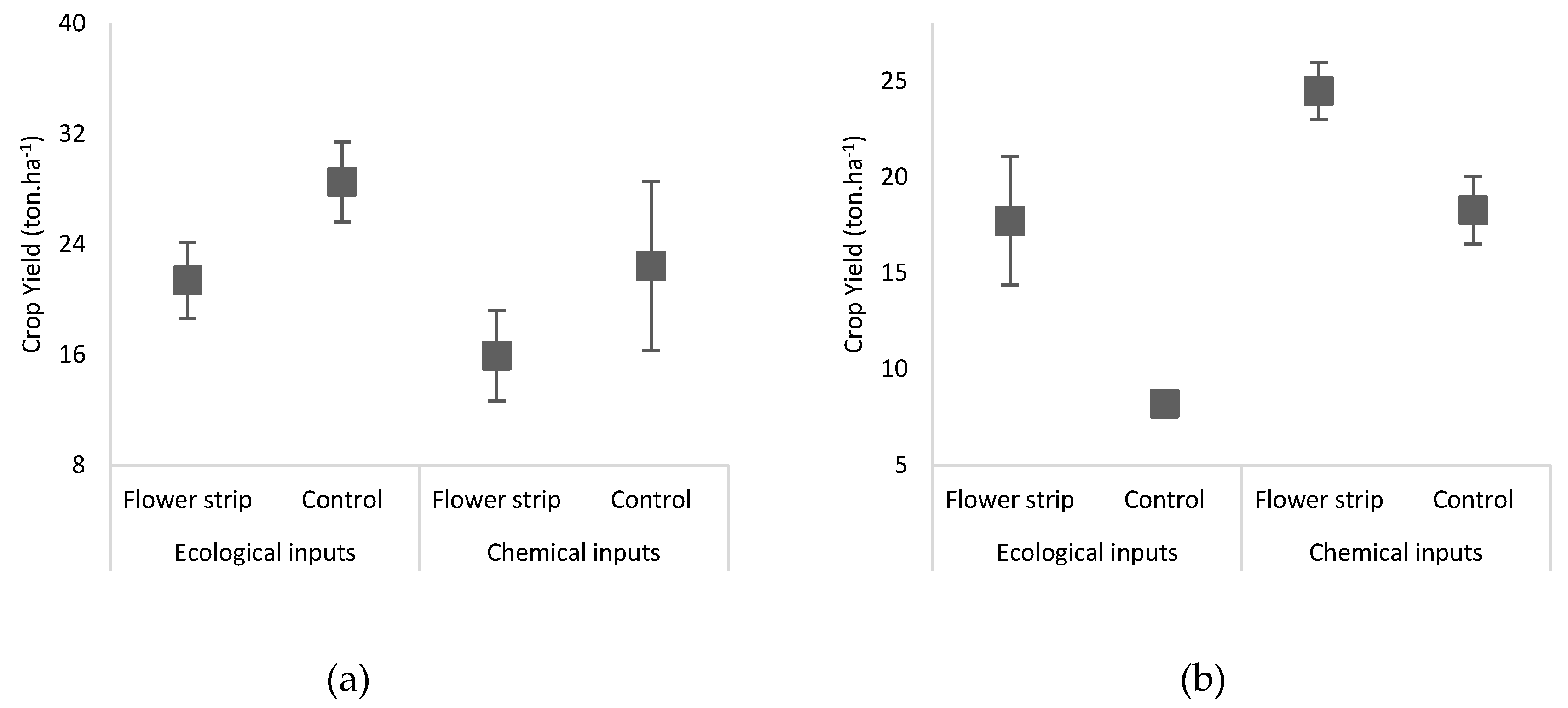

Second experimental cycle

The introduction of flowering plants affected the yield of both crops differentially. For lettuce in intercropping, yields were lower in the presence of flowering plants compared to control plots in both agricultural management schemes. However, in monoculture plots, lettuce yield was higher in the presence of flower strips regardless of the management type (

Table 2). In contrast, the yield of broccoli was significantly higher in the presence of flower strips, regardless of the diversification practice or agronomic management type (

Table 2).

Lettuce yield decreased by 25 to 40% when intercropped compared to monoculture planting. Although higher yields were observed in control plots compared to those with flowering plants, these differences were not statistically significant (

Supplementary Material, Table S5). Similarly, the type of agronomic management had no statistically significant effects on lettuce yield (

Figure 5A).

In the case of broccoli, the yield of this crop was even higher in intercropping plots compared to monoculture, specifically under organic management schemes and with the introduction of flowering plants, where production exceeded that of monoculture by 3.7 tons/ha (

Table 2). Both factors, the type of management and the introduction of flowering plants, affected broccoli yield (Fig. 5B), although their interaction was not statistically significant (

Supplementary Material, Table S6).

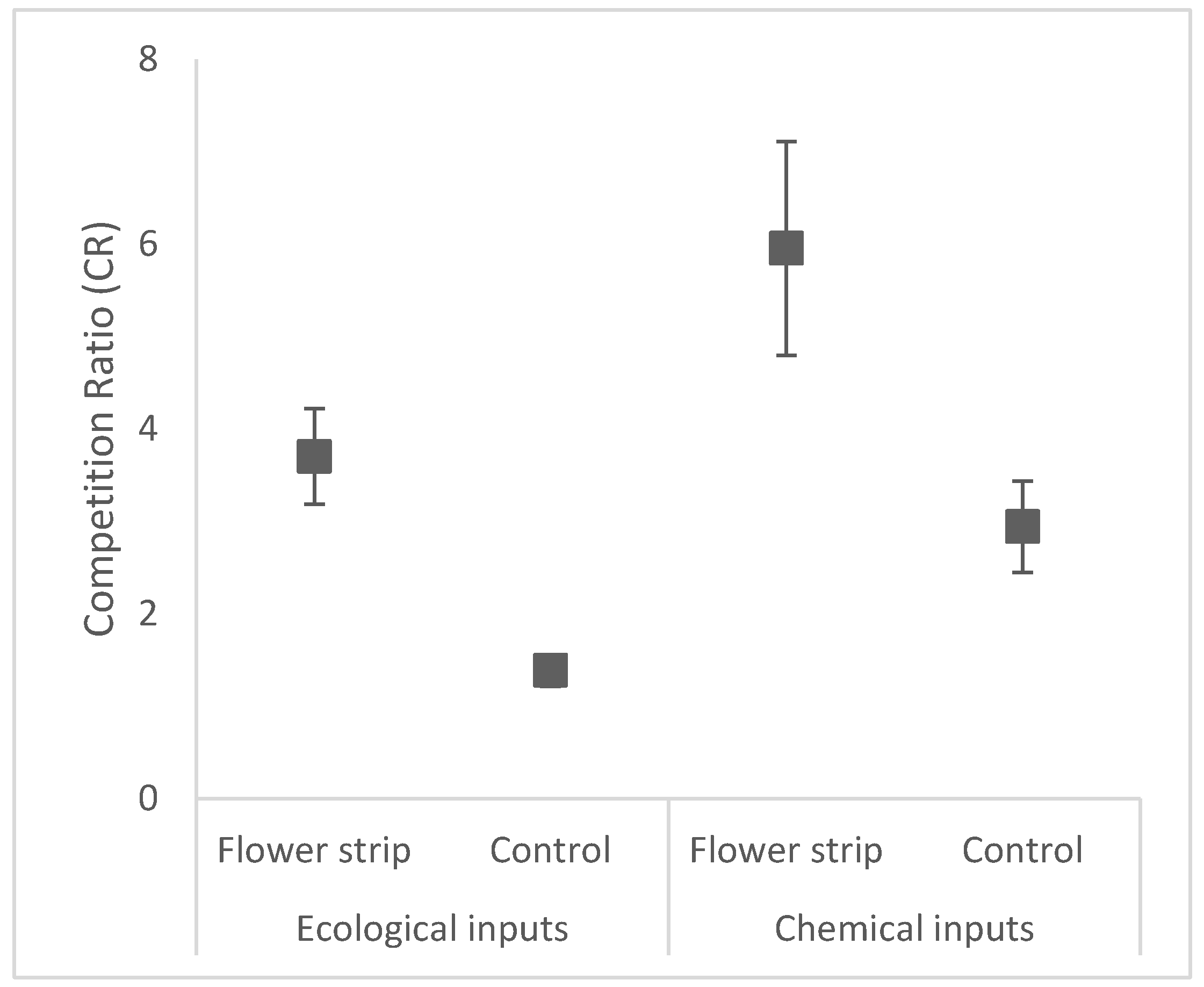

Competitive rate

In

Table 3 and

Table 4, it can be observed that the CR (Competitive Rate) values for broccoli were >1 during both experimental cycles, indicating that this crop was more competitive than lettuce, whose values were <1 in all cases. Planting density and the introduction of flowering plants did not significantly affect the competitiveness of broccoli during the first cycle, although higher CR values were observed in plots with flower strips.

In the second experimental cycle, the type of management and the presence of flowering plants affected the competitiveness of broccoli (

Figure 6). The competitiveness of this crop is higher in plots with flowering plants in chemical management (CR mean = 5.96) and in organic management (CR mean = 3.70), while in control plots, the values were 2.94 under chemical management and 1.38 under organic management. For lettuce, CR values varied between 0.2 and 0.8, and none of the evaluated factors had an effect on the competitiveness of this crop.

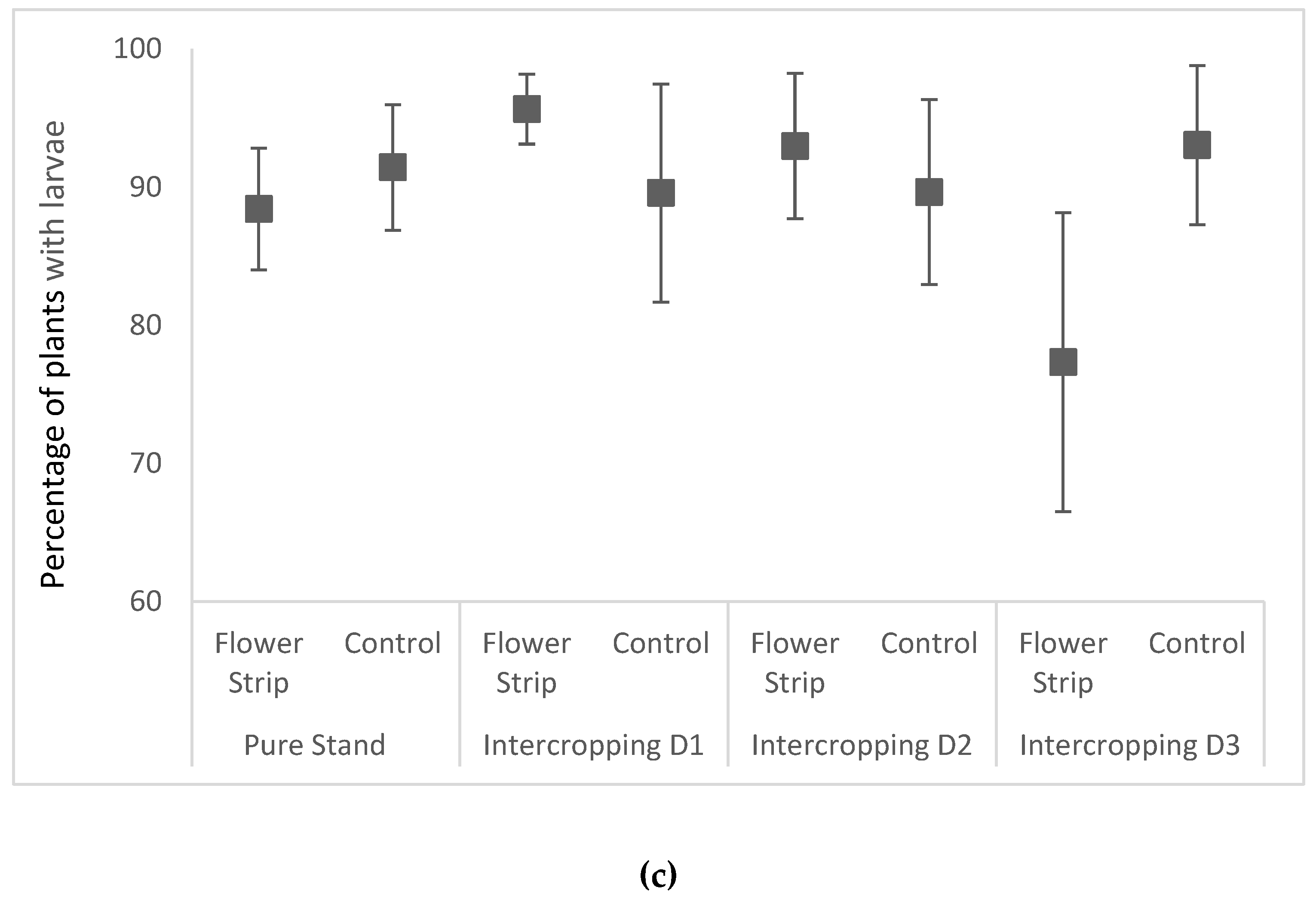

Incidence of pests and diseases

First experimental cycle

The percentage of lettuce plants with damage from

Sclerotinia sp. varied between 0.9% in monoculture without flower strips and 5.2% in intercropped plots planted at an intermediate density of 50,000 plants.ha

-1 None of the intercropping treatments or the inclusion of flowering plants had an effect on the incidence of this disease (

Figure 7A,

Supplementary Material, Table S7). In contrast, the presence of mollusks was affected by intercropping and the inclusion of flower strips (

Supplementary Material, Table S8). The lowest infestation of slugs was observed in associated plots planted at low densities and without flower strips (2.07%), while the highest values were found in associated plots planted at low density with the presence of flowering plants (47.92%). Slug infestation was lower in monocultures compared to that observed in associated crops (

Figure 7B). In broccoli, none of the intercropping treatments or the presence of flowering plants had an effect on the incidence of

Plutella xyllostela larvae (

Figure 7C,

Supplementary Material, Table S9).

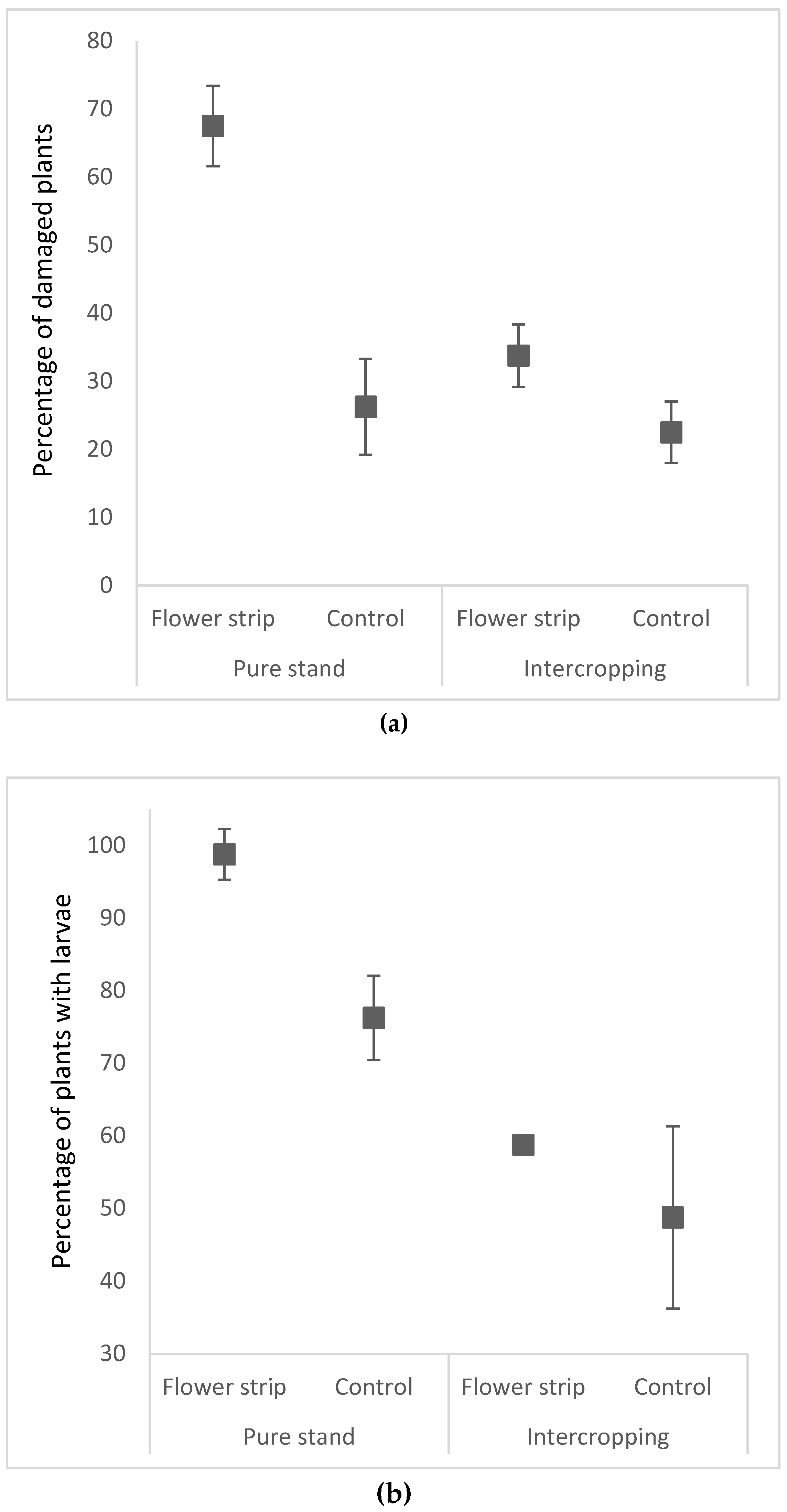

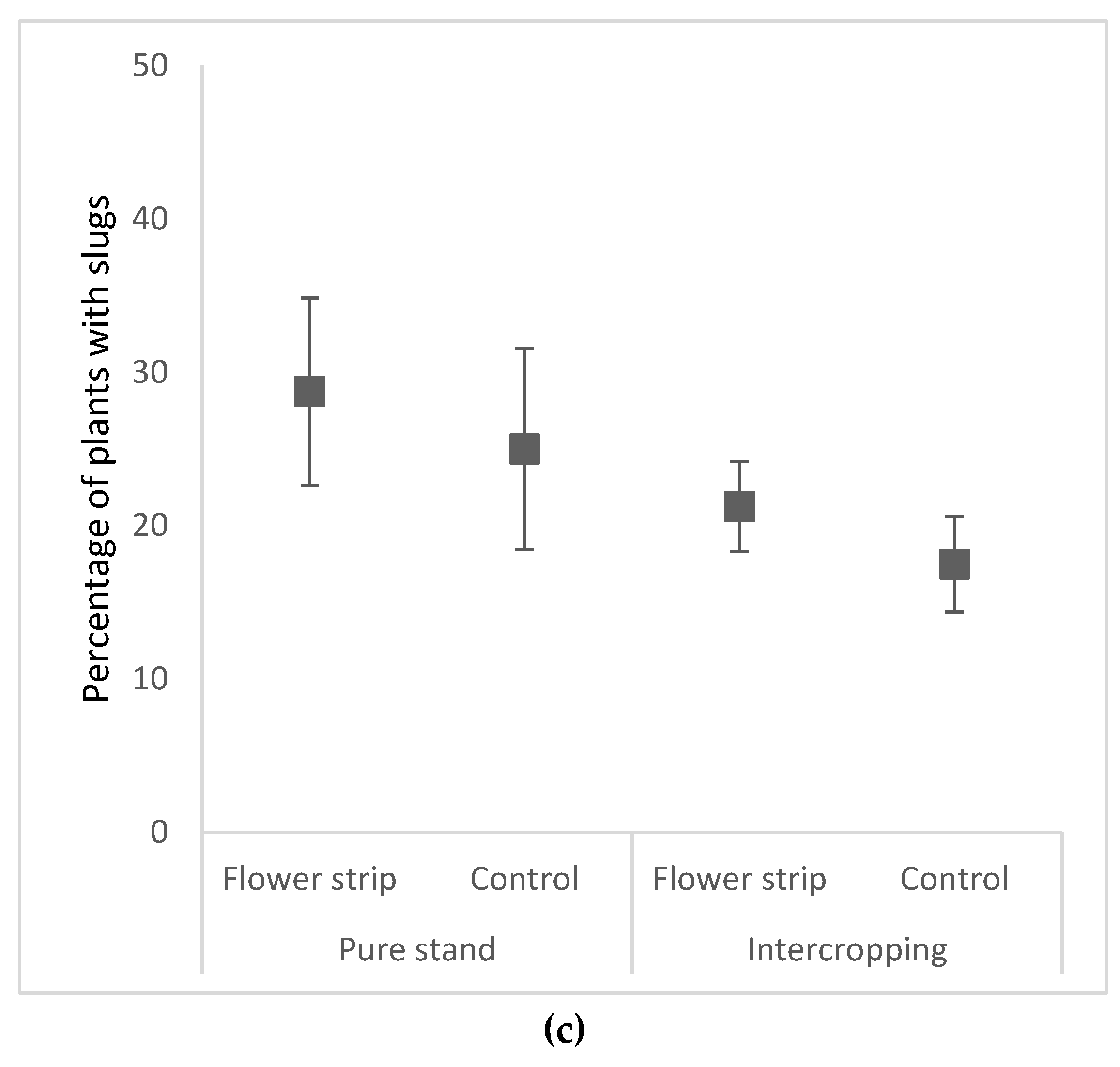

Second experimental cycle

The intercropping treatment affected the incidence of

Sclerotinia in lettuce and

Plutella xylostella in broccoli (

Figure 8,

Supplementary Material, Table S10-11). A reduction in

Sclerotinia damage was observed in plots with flower strips, where the percentage of affected plants was 60% in monoculture compared to 22% in intercropping. Similarly, the percentage of broccoli plants with

P. xylostella larvae was significantly different between monoculture (100%) and intercropping (62.5%). Regarding slug infestation in lettuce, none of the evaluated factors had an effect on the presence of the pest (

Supplementary Material, Table S12), with infestation fluctuating between 17.5% and 37.5% on average (

Figure 8).

Economic analysis

First experimental cycle

In

Table 5, the results of the profit generated by different treatments are shown. Profitability reaches up to 46.9% in lettuce crops. In intercropping, the implementation of flower strips generated higher profit compared to control plots. The increase in planting density between D1 and D2 was 3.51 million COP (Colombian pesos), while changing from D2 to D3 was 1.21 million COP, being contrasting with control intercrops, where increasing density also increases profit (D1 – D2: 2.99 million COP, D2 – D3: 3.87 million COP). With regard to broccoli monoculture, it incurs economic losses of 13.24 and 6.16 million COP with and without flower strips, respectively; the lowest losses occur in the absence of the flower strip. The depressing effect may be related to crop management, which was organic for this cycle.

Second experimental cycle

In the second production cycle, a positive economic effect of the aromatic strips was evident under both crop management systems (

Table 6). The highest profits were obtained in the organic market with monoculture of lettuce and intercropping, whereas the opposite occurred in broccoli, which recorded economic losses in organic monoculture, with a loss of 5.87 million COP ha

-1 with flower strips and 11.46 million COP ha

-1 in the control. In chemical management, profits of 14.57 and 8.66 million COP ha

-1 were reported with flower strips and control, respectively.

Discussion

This study provides an assessment of the efficiency of two agricultural diversification strategies in horticultural production in Colombia, aimed at transitioning to a low-input and more sustainable agriculture. As expected, the combination of flowering plants and intercropping has the potential to improve the ecological and productive efficiency of the land, especially under organic management schemes and at intermediate to high planting densities. With respect to intercropping, we employed a lettuce-broccoli intercropping system in a substitution series, where we observed reductions in the yields of the component crops, likely due to interspecific competition. Concerning the introduction of flower strips, the positive effect of this strategy on the yield and profitability of broccoli is highlighted when managed with conventional chemical inputs. The results revealed that organic broccoli production is only profitable in intercropping, so that growing this vegetable in monoculture faces challenges in developing planting materials well-adapted to environments with limitations on certain nutrients, as is the case in organic agriculture. The economic analysis emphasizes the importance of having markets that recognize an added value for organic production, as the productivity reductions observed in substituting chemical inputs in both crops can be compensated with a better price for the products. In this regard, lettuce production under an organic production scheme is the most profitable option under the evaluated market conditions. In this sense, this work underscores the necessity for transitions to more sustainable agriculture to be supported by consumers in differentiated markets.

Productive efficiency

In an ecological management scheme (first cycle), production shows a greater utilization of the soil with the implementation of crop diversification strategies, although there is no interaction that enhances this effect among the evaluated factors. The LER is increased with density and the implementation of flower strips in both monocultures and intercropped plots of the assessed species (

Figure 1). These results suggest that the plants forming the flower strips may exhibit positive allelopathic effects, either through the release of volatile substances or root exudates, as well as acting as a windbreak barrier, favoring better water regimes for the crops leading to higher joint yields of broccoli and lettuce when interacting with flower strips.

At low planting densities (37800 plants.ha-1), intercropping does not surpass the efficiency of monocultures (LER<1), even in the presence of flowering plants. As expected, as planting density increases, intercropping efficiency improves, with LER values ranging between 1.08 and 1.19, the latter in the presence of flowering plants. From a population density of 50,000 plants.ha-1 intercropping is more efficient in resource utilization, such as water and nutrients, compared to other non-economically relevant plants (weeds). This observation aligns with the selection of optimal planting densities made in a workshop with producers, who took into account productive aspects of yield, management, and market considerations.

In respect of the type of agronomic management (second cycle), intercropping efficiency is higher in plots with organic inputs (average LER = 1.38) compared to conventional chemical management (average LER = 1.29). The inclusion of flower strips improves this efficiency by up to 40%, compared to the 27% observed in control plots. The results indicate that the combination of aromatic flower strips with the intercropping of broccoli and lettuce, planted at a density of 50,000 plants.ha-1 and under an organic management scheme, enhances land use efficiency by up to 58%. This information is novel in the context of horticulture in countries like Colombia, where the adoption of organic agriculture is only around 1%, and small family farmers, especially, lack validated technological recommendations to facilitate the adoption of practices such as intercropping or flower strips.

Crop yield and interspecific competition

The lettuce yields in intercropping show a reduction compared to monocultures, as evidenced by comparing half of the value achieved by the monoculture to the intercropped value at a similar plant density. For the first experimental cycle, the lettuce yield was 37.95 t ha

-1 (monoculture) and 30.6 t ha

-1 (intercrop D3) in the presence of flower strips, while in the control, the monoculture reached 35.5 t ha

-1and intercrop - D3 yielded 25.3 t ha

-1, resulting in a reduction of around 20% in the presence of flower strips and 28% in the control. This reduction may be related to a low ability to compete with the other species, particularly for light, which is often the most critical factor related to crop yield in intercropping [

28]. In our study, the competition ratio (CR) of lettuce ranged between 0.48 and 0.78 across different planting densities, while broccoli exhibited CR values between 1.87 and 2.12, indicating that the latter crop is much more competitive than lettuce (

Table 3). As suggested by a previous study, broccoli might have a higher competitive ability than lettuce due to its larger and more horizontal leaves, and broccoli develops a taller canopy earlier [

29]. The phyllotaxis of the two species involved in intercropping can also influence this, as lettuce has leaves concentrated at a point, giving it a disadvantage compared to broccoli, which has a leaf arrangement that allows it to capture direct sunlight, while lettuce receives less radiation due to interference from broccoli. Similar results have been reported previously for the intercropping of broccoli-lettuce by Ohse [32], Brennan observed inhibition of lettuce growth when planted in association with larger plants [

29]. Additionally, the lower competitive ability of lettuce in intercropping has also been reported in tomato-lettuce intercropping, where the photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) intercepted by lettuce decreases as the tomato grows [

28].

Regarding management practices, conventional chemical management combined with the inclusion of flowering plants exacerbates the competitive ability of broccoli, shifting from a competition ratio (CR) of 6.0 in conventional production to 3.7 in organic management. These results demonstrate that the selected broccoli hybrid for the study is well-adapted to a type of agriculture with high input (fertilizer) where there may be synergistic effects with a favorable microclimate created by the addition of flowering plants. Specifically, the decline in broccoli yield in monoculture under organic management, from 24 t ha

-1 with chemical management to 14 ton ha

-1 in the flower strip plots and from 18.6 ton ha

-1 to 12.1 ton ha

-1 in control plots, supports the idea that the transition to organic agriculture should be facilitated by the development of varieties better adapted to nutrient-poor environments or by combining fertigation strategies that meet specific nutrient needs crucial for broccoli head development. Our results challenge the notion that intercropping with broccoli based on conventional management could provide the highest total yield, productivity, and profitability [

30] and show that organic broccoli production is profitable only in intercropping, with system productivity potentially higher when including flower strips.

Incidence of plagues and diseases

The incidence of Sclerotinia sp. does not show differences with or without flower strips. This may be related to the history of the plot prior to the experimental trial, where the disease inoculum in the soil was low. However, for the second cycle, a higher incidence of the disease was observed in monoculture compared to intercropping. This difference could be attributed to the fact that in monoculture, the entire population of lettuce plants may be susceptible to the pathogen, potentially leading to a higher disease development rate in the crop. Conversely, in intercropping, where broccoli is unaffected by the pathogen, the disease's development rate would be lower.

Our results do not provide conclusive evidence for the idea that intercropping and flowering plants are associated with better regulation of Plutella xylostella in broccoli. During the first cycle, statistically significant differences between monocultures and intercropped plots in the percentage of plants with larvae were not observed. Contrarily, in the second cycle, the incidence of larvae was significantly higher in the monoculture. Moreover, the presence of larvae on the plants did not cause damage to production. Therefore, the effect of intercropping on P. xylostella should be further assessed in larger plots.

Regarding the presence of mollusks, the damage is higher at higher crop densities and in plots with flowering plants during cycle 1, suggesting that a more humid environment in the flower strip plots may favor the presence of the pest. However, this result was not observed in cycle 2, where slugs appear to be more abundant in monocultures compared to intercropped plots, although none of the evaluated factors significantly affected the incidence of this pest.

Economic analysis

Among the main findings of the study, it is highlighted, firstly, that organic lettuce production is the most profitable activity for producers. Secondly, organic broccoli production is economically viable only when cultivated in intercropping. According to the results, all intercropping treatments are financially viable, and their profitability significantly increases when flower strips are incorporated into the system.

It is worth noting that the economic analysis has not considered the potential utilization of flower species included in the strips, which can typically be used for direct sale, home consumption of herbs, or in the crafting of natural cosmetic products. Therefore, the combination of productive diversification strategies in vegetable production emerges as an alternative for small-scale producers to address the price volatility of main crops or losses incurred due to the progression of diseases that limit crop production, such as Plasmodiophora brassicae in the study area—a disease exclusive to cruciferous crops with no technologies available to control its progression. In this regard, diversification provides socioecological resilience to producers facing the aforementioned challenges.

Another key finding of this study is that beyond production parameters, market conditions must be considered when evaluating the feasibility of diversification strategies in transitions to more sustainable agriculture. In the evaluated case, the reductions in lettuce yield in intercropping and organic production systems are offset by greater recognition of value in a specialized agroecological market (La Tulpa). Agroecological markets tend to operate on a local scale and cater to a specialized audience that values producers' efforts to reconfigure their plots and produce healthy food. In relation to the producers, these markets aim to build networks of trust between producers and consumers, ensuring fair payment to the producer and favorable prices for the consumer. Therefore, the development of more sustainable agriculture should be driven by consumers, through raising awareness about food production practices that translate into fair prices for the producer. In this way, the producer should not bear the sole risk of economic losses when transitioning to a more sustainable agriculture model.

Conclusions

The inclusion of flower strips enhances the productive efficiency of the broccoli-lettuce intercropping, especially in organic production schemes and at planting densities of 50,000 plants.ha-1. However, the selected intercropping arrangement (substitution series) reveals strong competition among the involved species. Therefore, future research suggests modifying the plant arrangement to reduce the effects of competition for light between broccoli and lettuce. Regarding agronomic management, organic lettuce production is economically viable in the analyzed context. However, organic broccoli production results in financial losses, highlighting the need for research focused on improving nutrient uptake efficiency for this species and identifying varieties well-adapted to nutrient-poor environments. In conclusion, intercropping and the introduction of flower strips enhance resource use efficiency in broccoli and lettuce production, making them technologies that should be promoted in the transition towards more sustainable agriculture. However, this strategy should be accompanied by the creation of market niches that recognize the added value of low-input production, generating healthier foods and protecting the environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.; methodology, E.M. and C.A.M.-P.; formal analysis, E.M. and C.A.M-P.; investigation, E.M., C.A.M.-P., E.G.R.-G. and E.I..; data curation, E.M., C.A.M.-P., E.G.R.-G. and E.I; writing—original draft preparation, E.M., C.A.M.-P., E.G.R.-G; writing—review and editing, E.M.; visualization, E.M.; project administration, E.M.; funding acquisition, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of the science, technology, and innovation project “Fortalecimiento de capacidades para la innovación en la agricultura campesina familiar y comunitaria tendiente a mejorar los medios de vida de la población vulnerable frente a los impactos del COVID-19 en la subregión Centro del departamento de Nariño” supported by the Science, Technology, and Innovation Fund of the Colombian general royalties’ system (Code BPIN2020000100702).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements between the participants (institutions and producers).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Gobernación de Nariño and Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria (Agrosavia) for their support through the agreement No. 2050-2020. We also like to thank producers, associations, professionals, technicians, and other institutions that committedly joined this initiative.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agronet. Área, producción y rendimiento nacional por cultivo. http://www.agronet.gov.co/estadistica/Paginas/home.aspx?cod=1. (accessed on 08 august 2023).

- Patiño, M.; Valencia-Guerrero, M. F.; Barbosa-Angel, E. S.; Martínez-Cordón, M. J.; Donado-Godoy, P. Evaluation of Chemical and Microbiological Contaminants in Fresh Fruits and Vegetables from Peasant Markets in Cundinamarca, Colombia. J. Food. Prot. 2020, 83(10), 1726-37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolución 187 de 2006. "Por la cual se adopta el reglamento para la producción primaria, procesamiento, empacado, etiquetado, almacenamiento, certificación, importación, comercialización y se establece el Sistema de Control de Productos Agropecuarios Ecológicos”. (https://www.ica.gov.co/getattachment/efc964b6-2ad3-4428-aad5-a9f2de5629d3/187.aspx). (accessed on: 10/11/2023).

- Velez, R. J. La agricultura Orgánica solo tiene 1% de hectáreas del total del mercado de alimentos. https://www.agronegocios.co/agricultura/la-agricultura-organica-solo-tiene-1-de-hectareas-del-total-del-mercado-de-alimentos-3140358. (accessed on 04/08/ 2023). 2021.

- Resolución 464 de 2017. Lineamientos Estratégicos para la Agricultura Campesina, Familiar y Comunitaria. https://www.minagricultura.gov.co/Normatividad/Resoluciones/Resoluci%C3%B3n%20No%20%20464%20de%202017%20Anexos.pdf. (accessed on: 01/10/2023).

- Tittonell, P. Assessing resilience and adaptability in agroecological transitions. Agric. Syst. 2020, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bene, C; Gomez-Lopez, M. D.; Francaviglia, R.; Farina, R.; Blasi, E.; Martinez-Granados, D. et al. Barriers and Opportunities for Sustainable Farming Practices and Crop Diversification Strategies in Mediterranean Cereal-Based Systems. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Foley, J. A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G. P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S. R.; et al. Global consequences of land use. Sci. 2005, 309(5734), 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Klein, A. M.; Kruess, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Thies, C. Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity – ecosystem service management. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács-Hostyánszki, A.; Espíndola, A.; Vanbergen, A. J.; Settele, J.; Kremen, C.; Dicks, L. V. Ecological intensification to mitigate impacts of conventional intensive land use on pollinators and pollination. Ecol. Lett. 2017, 20(5), 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, J.; Outhwaite, C. L.; Kinnersley, R.; Freeman, R.; Gregory, R. D.; Adedoja, O.; et al. Global effects of land-use intensity on local pollinator biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Bommarco, R.; Kleijn, D.; Potts, S. G. Ecological intensification: harnessing ecosystem services for food security. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28(4), 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P. Ecological intensification of agriculture - sustainable by nature. Curr.Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 8, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Kleijn, D.; Williams, N. M.; Tschumi, M.; Blaauw, B. R.; Bommarco, R.; et al. The effectiveness of flower strips and hedgerows on pest control, pollination services and crop yield: a quantitative synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23(10), 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C.; Iles, A.; Bacon, C. Diversified Farming Systems: An Agroecological, Systems-based Alternative to Modern Industrial Agriculture. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M. V.; Bocci, G.; Moonen, A. C. Utilisation of plant functional diversity in wildflower strips for the delivery of multiple agroecosystem services. Entom. Exp. Appl. 2016, 158(3), 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R. W.; Karley, A. J.; Newton, A. C.; Pakeman, R. J.; Schöb, C. Facilitation and sustainable agriculture: a mechanistic approach to reconciling crop production and conservation. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30(1), 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, G.; Bommarco, R.; Wanger, T. C.; Kremen, C.; van der Heijden, M. G. A.; Liebman, M.; et al. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6(45). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Hossain, A.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Ondrisik, P.; Gitari, H.; et al. Intercropping-A Low Input Agricultural Strategy for Food and Environmental Security. Agronomy-Basel 2021, 11(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, H. A Review on the Comparative Advantage of Intercropping Systems. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare 2015, 7(7). [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, C. S.; Cecilio, A. B.; Mendoza-Cortez, J. W.; Nascimento, C.S.; Neto, F. B.; Grangeiro, L. C. Effect of population density of lettuce intercropped with rocket on productivity and land-use efficiency. PloS one 2018, 13(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, G. D.; Fonseca., D.; Wilk, Sampaio, A.; Oliveira., L.; Marinho, J. G. Organic carrot-lettuce intercropping using mulch and different irrigation levels. J. Food. Agric. Environ. 2014, 12(1), 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Willey, R. W. Intercropping—It’s Important and Research Needs. Part 1. Competition and Yield Advantages. Field Crop Abstracts. 1979, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos-Pérez, M.; Sánchez-Navarro, V.; Zornoza, R. Intercropping systems between broccoli and fava bean can enhance overall crop production and improve soil fertility. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, H. J. Clasificaciones climáticas. Instituto Colombiano de Hidrología y Meteorología y Adecuación de Tierras - HIMAT. Bogotá. 1991.

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE].Sistema de Información de Precios y Abasteci-miento del Sector Agropecuario – SIPSA. https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/agropecuario/sistema-de-informacion-de-precios-sipsa (accessed on: 08/11/2023).

- La Tulpa. (2023). Productos. https://www.familiatulpa.com/tienda/ (accessed on: 08/11/2023).

- Cunha-Chiamolera, T. P. L.; Cecilio, A. B.; Santos, D. M. M.; Chiamolera, F. M.; Guevara-González, R. G.; Nicola, S.; et al. Lettuce in Monoculture or in Intercropping with Tomato Changes the Antioxidant Enzyme Activities, Nutrients and Growth of Lettuce. Horticulturae 2023, 9(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan; E., B. Agronomy of strip intercropping broccoli with alyssum for biological control of aphids. Biological Control. 2016, 97, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.; Turan, M. Growth, Yield And Mineral Content Of Broccoli Intercropped With Lettuce. J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 2013, 23(3), 919–922. [Google Scholar]

- Ohse, S.; Alves-Rezende, B. L.; Sleutjes-Silveira, L.; Fernandes, O. R.; Gonçalves- Cortez, M. Agronomic feasibility of broccoli and lettuce intercropping established in different growing periods. Idesia (Arica). 2012,30(2),29–37. https://www.scielo.cl/pdf/idesia/v30n2/art04.pdf.

Figure 1.

Effect of planting density and the introduction of flower strips on land use efficiency (LER) in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1). Three planting densities were evaluated: 37,800, 50,000, and 62,500 plants.ha−1.

Figure 1.

Effect of planting density and the introduction of flower strips on land use efficiency (LER) in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1). Three planting densities were evaluated: 37,800, 50,000, and 62,500 plants.ha−1.

Figure 2.

Effect of the establishment of flower strips (a) and planting density (b) on the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1).

Figure 2.

Effect of the establishment of flower strips (a) and planting density (b) on the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1).

Figure 3.

Effect of agronomic management (organic and chemical) and the introduction of flowering plants on land use efficiency (LER) in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1).

Figure 3.

Effect of agronomic management (organic and chemical) and the introduction of flowering plants on land use efficiency (LER) in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1).

Figure 4.

Effect of the establishment of flower strips (a) and planting density (b) on the yield in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1).

Figure 4.

Effect of the establishment of flower strips (a) and planting density (b) on the yield in broccoli-lettuce intercropping (1:1).

Figure 5.

Effect of agronomic management and the introduction of flowering plants on the yield of lettuce (a) and broccoli (b) planted in intercropping (1:1) and established under two agronomic management schemes (organic vs. chemical).

Figure 5.

Effect of agronomic management and the introduction of flowering plants on the yield of lettuce (a) and broccoli (b) planted in intercropping (1:1) and established under two agronomic management schemes (organic vs. chemical).

Figure 6.

Effect of agricultural management and flower strips on Competitive ratio (CR) of broccoli intercropping whit lettuce (1:1) systems.

Figure 6.

Effect of agricultural management and flower strips on Competitive ratio (CR) of broccoli intercropping whit lettuce (1:1) systems.

Figure 7.

Pest incidence: (a) Damage by Sclerotinia sp. in lettuce, (b). Percentage of lettuce plants with damage by mollusks, (c). Percentage of broccoli plants with the presence of Plutella xylostella larvae. In the intercropping treatments, D1 corresponds to a density of 37,800 plants.ha-1, D2 to a density of 50,000 plants.ha-1, and D3 to a density of 62,500 plants.ha-1.

Figure 7.

Pest incidence: (a) Damage by Sclerotinia sp. in lettuce, (b). Percentage of lettuce plants with damage by mollusks, (c). Percentage of broccoli plants with the presence of Plutella xylostella larvae. In the intercropping treatments, D1 corresponds to a density of 37,800 plants.ha-1, D2 to a density of 50,000 plants.ha-1, and D3 to a density of 62,500 plants.ha-1.

Figure 8.

Effects of intercropping and the inclusion of flowering plants on the incidence of pests and diseases in the Broccoli + Lettuce system (1:1). (a) Incidence of Sclerotinia sp. in lettuce (b). Incidence of P. xylostella in broccoli.; (c) Incidence of mollusks in lettuce.

Figure 8.

Effects of intercropping and the inclusion of flowering plants on the incidence of pests and diseases in the Broccoli + Lettuce system (1:1). (a) Incidence of Sclerotinia sp. in lettuce (b). Incidence of P. xylostella in broccoli.; (c) Incidence of mollusks in lettuce.

Table 1.

Yield of broccoli and lettuce established in diversified cropping systems at different planting densities, compared to yield in monoculture.

Table 1.

Yield of broccoli and lettuce established in diversified cropping systems at different planting densities, compared to yield in monoculture.

| Crop |

Planting System |

Sown density |

Treatment |

Mean of Crop Yield (Ton.ha-1) |

SD of Crop yield |

| Lettuce |

Intercropping |

37,800 |

Flower strip |

24.40 |

3.7 |

| |

|

|

Control |

24.10 |

1.9 |

| |

|

50,000 |

Flower strip |

28.30 |

2.7 |

| |

|

|

Control |

24.70 |

3.1 |

| |

|

62,500 |

Flower strip |

30.60 |

2.4 |

| |

|

|

Control |

25.30 |

2.3 |

| |

Pure stand |

62,500 |

Flower strip |

75.90 |

7.1 |

| |

|

|

Control |

71.10 |

7.0 |

| Broccoli |

Intercropping |

37,800 |

Flower strip |

9.90 |

2.5 |

| |

|

|

Control |

8.30 |

2.1 |

| |

|

50,000 |

Flower strip |

10.90 |

2.2 |

| |

|

|

Control |

10.60 |

2.3 |

| |

|

62,500 |

Flower strip |

11.50 |

2.3 |

| |

|

|

Control |

12.30 |

3.2 |

| |

Pure stand |

40,000 |

Flower strip |

14.6 |

2.3 |

| |

|

|

Control |

17.3 |

2.2 |

Table 2.

Yield of broccoli and lettuce established in diversified cropping systems at different agricultural management, compared to yield in monoculture.

Table 2.

Yield of broccoli and lettuce established in diversified cropping systems at different agricultural management, compared to yield in monoculture.

| Crop |

Planting system |

Agricultural Management |

Treatment |

Mean of Crop Yield (ton.ha-1) |

SD Crop Yield |

| Lettuce |

Intercropping |

Ecological inputs |

Flower strips |

21.4 |

4.7 |

| |

|

|

Control |

28.5 |

5.0 |

| |

|

Chemical inputs |

Flower strips |

15.9 |

5.7 |

| |

|

|

Control |

22.5 |

10.6 |

| |

Pure stand |

Ecological inputs |

Flower strips |

63.9 |

12.6 |

| |

|

|

Control |

58.0 |

8.6 |

| |

|

Chemical inputs |

Flower strips |

81.9 |

6.8 |

| |

|

|

Control |

58.3 |

10.9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Broccoli |

Intercropping |

Ecological inputs |

Flower strips |

17.7 |

5.8 |

| |

|

|

Control |

8.2 |

0.8 |

| |

|

Chemical inputs |

Flower strips |

24.5 |

2.6 |

| |

|

|

Control |

18.3 |

3.0 |

| |

Pure stand |

Ecological inputs |

Flower strips |

14.0 |

1.9 |

| |

|

|

Control |

12.6 |

2.8 |

| |

|

Chemical inputs |

Flower strips |

24.0 |

1.3 |

| |

|

|

Control |

18.6 |

2.0 |

Table 3.

Effect of plant density and introduction of flower strips on Competitive ratio (CR) of lettuce + broccoli intercropping (1:1) systems.

Table 3.

Effect of plant density and introduction of flower strips on Competitive ratio (CR) of lettuce + broccoli intercropping (1:1) systems.

| Sown Density |

Treatment |

CR Lettuce |

CR Broccoli |

|

37,800plants.ha-1

|

Flower strips |

0.48 |

2.12 |

| |

Control |

0.78 |

1.49 |

|

50,000plants.ha-1

|

Flower strips |

0.51 |

2.00 |

| |

Control |

0.63 |

1.87 |

| 62,500 plants.ha-1 |

Flower strips |

0.54 |

2.03 |

| |

Control |

0,.8 |

1.91 |

Table 4.

Effect of agricultural management and introduction of flower strips on Competitive ratio (CR) of lettuce + broccoli intercropping (1:1) systems.

Table 4.

Effect of agricultural management and introduction of flower strips on Competitive ratio (CR) of lettuce + broccoli intercropping (1:1) systems.

| Agricultural Management |

Treatment |

CR Lettuce |

CR Broccoli |

| Ecological inputs |

Flower strips |

0.3 |

3.7 |

| |

Control |

0.8 |

1.4 |

| Chemical inputs |

Flower strips |

0.2 |

6.0 |

| |

Control |

0.4 |

2.9 |

Table 5.

Net income, production cost, and profit (million COP ha-1) of broccoli and lettuce in monoculture and intercropped cultivation at different planting densities.

Table 5.

Net income, production cost, and profit (million COP ha-1) of broccoli and lettuce in monoculture and intercropped cultivation at different planting densities.

| Crop System |

Net Income

(millions COP ha-1) |

Production Cost

(millions COP ha-1) |

Overall Profit

(millions COP ha-1) |

Profitability (%) |

| Flower strip |

Control |

Flower strip |

Control |

Flower strip |

Control |

Flower strip |

Control |

Broccoli

Pure stand

|

27.72 |

32.85 |

40.96 |

39.01 |

-13.24 |

-6.16 |

-47.8 |

-18.8 |

Lettuce

Pure Stand

|

70.88 |

66.39 |

37.62 |

35.83 |

33.25 |

30.56 |

46.9 |

46.0 |

| Intercropping D1- 37,800 plants.ha-1 |

41.58 |

38.27 |

37.83 |

36.03 |

3.75 |

2.23 |

9.0 |

5.8 |

| Intercropping D2 – 50,000 plants.ha-1 |

47.12 |

43.19 |

39.87 |

37.97 |

7.26 |

5.22 |

15.4 |

12.1 |

| Intercropping D3 – 62,500 plants.ha-1 |

50.41 |

49.04 |

41.94 |

39.94 |

8.47 |

9.09 |

16.8 |

18.5 |

Table 6.

Net income, production cost, and profit (million COP ha-1) of broccoli and lettuce in monoculture and intercropped cultivation with different management practices.

Table 6.

Net income, production cost, and profit (million COP ha-1) of broccoli and lettuce in monoculture and intercropped cultivation with different management practices.

| Crop System |

Net income

(millions COP ha-1) |

Production cost

(millions COP ha-1) |

Overall profit

(millions COP ha-1) |

Profitability (%) |

| Flower Strip |

Control |

Flower Strip |

Control |

Flower Strip |

Control |

Flower Strip |

Control |

| Ecological |

| Broccoli Pure Stand |

35.09 |

27.56 |

40.96 |

39.01 |

-5.87 |

-11.46 |

-16.7% |

-41.6% |

| Lettuce Pure Stand |

183.42 |

167.63 |

37.62 |

35.83 |

145.80 |

131.80 |

79.5% |

78.6% |

| Intercropping |

103.56 |

93.32 |

39.87 |

37.97 |

63.69 |

55.35 |

61.5% |

59.3% |

| Chemical |

| Broccoli Pure Stand |

45.95 |

38.55 |

31.38 |

29.89 |

14.57 |

8.66 |

31.7% |

22.5% |

| Lettuce Pure Stand |

76.57 |

54.81 |

28.04 |

26.70 |

48.53 |

28.11 |

63.4% |

51.3% |

| Intercropping |

56.67 |

48.49 |

30.29 |

28.84 |

26.38 |

19.65 |

46.6% |

40.5% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).