1. Introduction

Despite recent advances with immunotherapies and targeted therapies, advanced lung and esophageal cancer remain highly morbid and fatal diseases with 5-year survival rates of about 5% [

1]. Although cancer care is often contextualized in terms of survival, there are other important cancer care outcomes, such as quality of life and cost of care. One increasingly recognized model that incorporates these outcomes is the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Value Framework, which “assesses the value of new cancer therapies based on clinical benefit in terms of life extension or survival” while also taking into consideration “side effects, and improvements in patient symptoms or quality of life in the context of cost” [

2]. Value-based frameworks are also increasingly utilized at system and policy levels for reimbursement and coverage decisions. For example, the Hospital Global Budget program in Maryland was implemented in 2014 with a goal of reducing unnecessary hospital utilization and encouraging primary care to mitigate health care costs and improve clinical outcomes [

3].

Palliative care (PC) is an example of a high-value intervention that improves quality of life for patients with advanced cancer and increases the likelihood of discussions of understanding of prognosis, advance care planning, and caregiver needs [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Additionally, inpatient PC and home-based PC for patients with serious or terminal illnesses have also been associated with decreased costs of care [

8]. PC teams are multidisciplinary and may involve PC physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, psychologists, chaplains, and allied health professionals. The ASCO and The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) endorse integration of PC services within 8 weeks of diagnosis of advanced cancers [

9,

10]. Although concurrent palliative care is recommended as standard of care for patients with advanced cancer, it is not universally available or integrated into care, and referrals to palliative care often occur late, if at all [

11].

While PC has numerous benefits as described previously, the impact of outpatient embedded PC in a multidisciplinary cancer clinic on inpatient outcomes and hospital value-based metrics for patients with advanced thoracic malignancies has yet to be fully described [

12]. We sought to evaluate associations between outpatient embedded palliative care and inpatient outcomes including emergency room visits, hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, 30-day readmissions, admissions within 30 days of death, inpatient mortality, time in hospice, and hospital charges.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study (IRB #00275889) of patients with advanced thoracic malignancies treated with palliative intent at the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center between 2/1/2019 and 9/30/2020. Exclusion criteria included patients receiving treatment with curative intent, patients less than 18 years old, and patients who did not receive oncologic care in the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center (located at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center).

During the study time period, a PC clinician (physician or advanced practice provider) was embedded within the thoracic oncology multidisciplinary clinic at Johns Hopkins Bayview alongside medical oncology, radiation oncology, thoracic surgery, and interventional pulmonology during three days of a five-day clinic week. The thoracic oncology clinic has a triage nurse, social worker, and pastoral care for multidisciplinary comprehensive care. Patients were referred to PC at the discretion of their primary thoracic medical oncologist or radiation oncologist, with the goal of patients being seen by the PC clinician on the same day or within 7 days of referral, either in-person or by telehealth visit. Nineteen patients in our cohort were enrolled in a clinical trial for early PC in patients with advanced lung cancer treated with palliative intent, and these patients were enrolled within 12 weeks of diagnosis of advanced disease. Prior to our study time period, which encompasses the opening of the embedded PC clinic, patients were referred to a free-standing PC clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital. The primary oncology team maintained their role as the primary prescriber for patients with guidance from the PC clinician.

We collected clinical data via chart review through EPIC. Sociodemographic and clinical variables included age, sex, race, insurance type, marital status, zip code, cancer type, cancer stage at diagnosis, dates of first outpatient oncology and PC visits, and date and location of death. Receipt of PC was defined as at least one outpatient PC visit documented in EPIC. We estimated median income by zip code as reported by the United States Census Bureau [

13]. We identified 9 high-risk zip codes (

Supplemental Figure S1) in East Baltimore that have previously been determined by our institutional cancer registry to have elevated rates of cancer mortality compared to other zip codes in Baltimore (IRB00160610). We collected clinical data regarding emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions from the Johns Hopkins Medicine hospitals (Johns Hopkins Hospital, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Sibley Memorial Hospital, Suburban Hospital, and Howard County General Hospital). We used Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t-test to determine whether sociodemographic and clinical variables differed based on outpatient PC status for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Hospital utilization and charge data was obtained from the Johns Hopkins Medicine Casemix/Datamart database, which is created and used for mandatory reporting to the state of Maryland and includes casemix information and billing data. The hospital charges included all charges regulated by Health Service Cost Review Commission (HSCRC), Maryland’s hospital rate-setting authority. This data was used to calculate average charge per day. Hospital charges from Sibley Memorial Hospital, Suburban Hospital, and Howard County General Hospital were not available, thus these hospitals were excluded from the charge analysis.

We compared clinical outcomes for those who received outpatient PC and those who did not, including number of emergency room visits, number of hospitalizations, number of ICU admissions, average and total length of stay, average hospital charges per admission and per day, total hospital charges, 30-day readmission rates, admissions within 30 days of death, inpatient mortality, average days receiving hospice services, and likelihood of PC consults during any inpatient admission. Incident rate ratios, average differences, and odds ratios were used to estimate differences between clinical outcomes for event counts, continuous outcomes, and binary outcomes, respectively. Effect sizes and p-values for event counts were calculated using generalized linear regression with a Poisson distribution, a log link, and person-time of observation as an offset. The person-time contribution [

14,

15] of each patient was defined as the time from the start of the study period (2/1/2019) until death or the end of the study period (9/30/2020), whichever came first. Simple linear regression was used to calculate effect sizes and p-values for continuous outcomes, and logistic regression was used for binary outcomes. Additionally, we created multivariable models to evaluate independent associations with outpatient PC and clinical outcomes. Whether a patient received outpatient embedded PC or not was the primary exposure of interest. Covariates were included in each model based on a priori association of these variables between our primary exposure and outcomes of interest. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.0.

3. Results

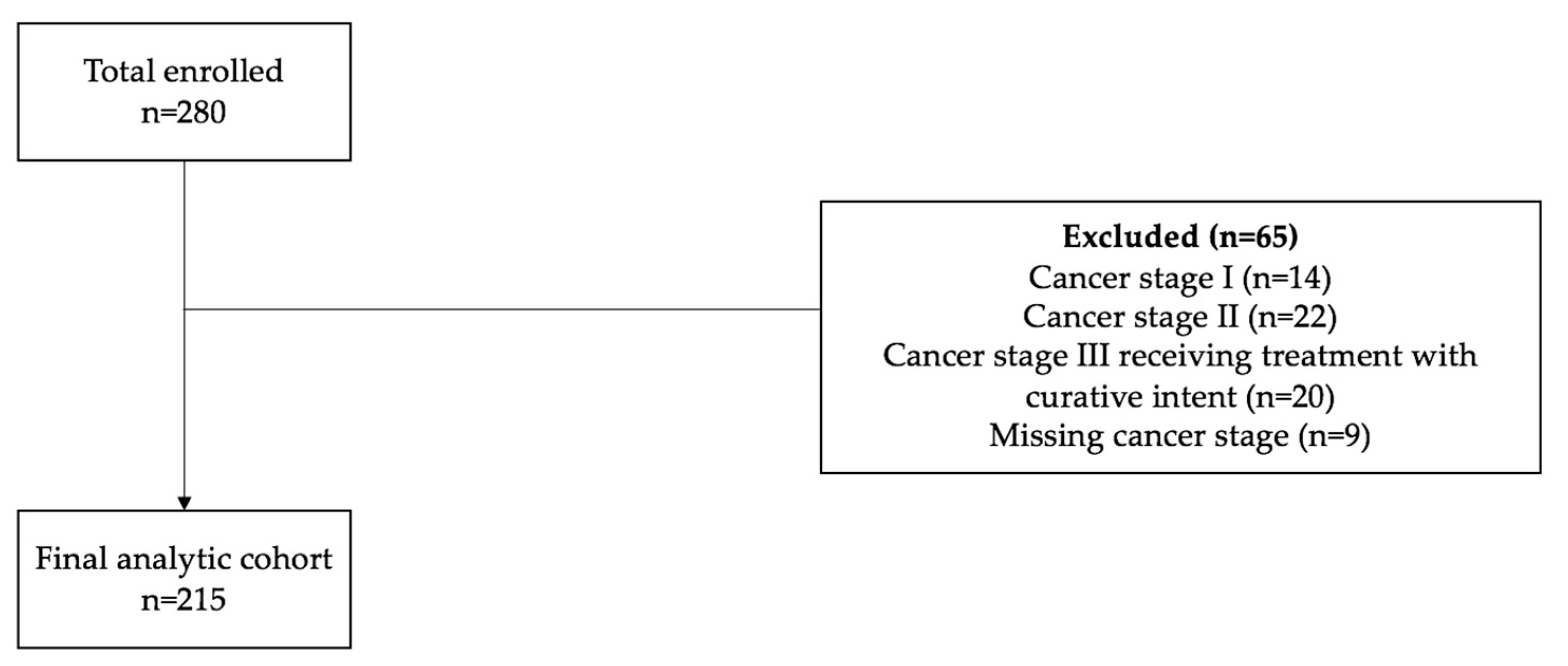

The final analytic cohort included 215 patients being treated for advanced thoracic malignancies with non-curative intent (

Figure 1). Study sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The cohort’s median age was 66 years, with 52% female patients, 69% White patients, and 60% married patients. Seventy-four percent of the cohort had non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 82% had stage IV disease at the time of diagnosis. Thirty-eight percent (81/215) of the cohort received outpatient palliative care (PC). A higher proportion of males (59% vs. 41%, p=0.011), White patients (77% vs. 64%, p=0.047), and Maryland residents (90% vs 79%, p=0.039) received PC than not. There were no significant differences in insurance type, marital status, high-risk zip code, cancer type, or stage at diagnosis between the PC and non-PC cohorts. For the entire cohort, 20% of patients died within 90 days from their first oncology visit at Johns Hopkins, 15% died within 90-180 days, and 65% lived beyond 180 days.

4. Discussion

Our study describes how an outpatient embedded PC model in a thoracic oncology multidisciplinary clinic for patients with advanced thoracic malignancies is associated hospital value-based metrics, including lower inpatient mortality, decreased likelihood of hospital admission within 30 days of death, and lower hospital charges per day. Our observations further support outpatient embedded palliative care as a high-value practice.

Both inpatient and outpatient models of palliative care have demonstrated improved quality metrics, such as inpatient mortality and hospital resource utilization. Brumley et. al performed a randomized trial of patients with terminal illnesses, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and cancer, with a life expectancy of less than one year. Patients enrolled in in-home PC were more likely to die at home (p<0.001), less likely to visit the ER (p=0.01), and less likely to be admitted (p<0.001), with lower inpatient hospital costs within the last 30 days of life [

16]. Furthermore, Vranas et. al. retrospectively evaluated 23,142 patients with advanced NSCLC at the Veterans Affairs HealthCare System who received inpatient or outpatient PC. Outpatient PC was associated with a reduced hospitalization rate within 30 days of death (aIRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.59-0.70) and lower likelihood of ER visits (aIRR 0.86; 95% CI 0.77-0.96) [

17].

Additionally, various models of palliative care are associated with lower costs. A randomized controlled trial by Gade, et. al. demonstrated that patients with a life expectancy of one year who were randomized to inpatient PC versus standard of care had a 6-month net cost reduction of

$4,855 per patient (p = 0.001) [

18]. Another study by Morrison, et. al. analyzed administrative data from 2,278 patients who received inpatient PC matched to patients who received usual care and showed lower costs per admission and costs per day for patients who received inpatient PC [

8]. We identified a significant difference in daily hospital charges for our outpatient PC cohort but did not observe a difference in average or total hospital charges. As more patients in the non-PC arm lived out of state and because we were unable to capture outcomes outside of our health system, we suspect that we were disproportionately unable to capture ER visits, hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and hospital charges for non-PC patients. Despite the likelihood of missing hospital and charge data for out of state patients, we still observed reduced charges per day in our PC arm. Furthermore, our differences in findings may be attributed partially to our collection of charge and hospitalization data throughout the patient’s disease course in this time period, not just the last 30 days or solely in patients with a life expectancy of less than one year.

While most NCI-designated cancer centers utilize free-standing PC clinics, there is growing interest in embedded PC clinics. Investigators at The Ohio State University reported in a retrospective cross-sectional cohort study that patients seen in a 12-month time period when PC was embedded, versus a 12-month period when patients were referred to a free-standing PC clinic, had a reduction in ER visits (adjusted RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.58-0.94) [

12]. Similarly to these investigators, we were only able to capture outcomes that occurred within our health system. However, we were able to capture a longer follow-up period than 12 months. Furthermore, our subset of patients who received PC was larger than was reported by Gast et. al. and did not include patients with curative-intent disease, perhaps selecting for a patient population who would benefit more from PC.

Though we could not assess for this in our study, we speculate that outpatient embedded PC may have impacted inpatient resource utilization measures due to multiple factors. Patients who saw outpatient PC may have had a different philosophy towards their illness at baseline. Furthermore, patients who received outpatient PC may have had more discussions about their understanding of their disease, prognosis, care planning, and wishes for end-of-life care. It is also possible that the presence of embedded outpatient PC may have off-target effects on oncology clinicians and patients due increased PC awareness, education, and support. Our data further supports an embedded model in the outpatient setting as being associated with improved inpatient value-based metrics, which should strongly be considered when hospitals discuss resource allocation for PC.

Our study has several limitations to consider. We have a small sample size and our study is retrospective. Our data is limited by the completeness and accuracy of documentation in the electronic medical record. Our study window includes the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and thus may reflect decreased access to appointments, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations. Our analysis did not stratify the PC cohort by early versus late PC, which may impact outcomes of measures. Additionally, we did not assess the number or frequency of visits with palliative care or ensure the TEAM (Time, Education, Assessment, Management) approach based on previous randomized trials, which may also impact outcomes [

19,

20]. While the majority of patients were seen by our embedded PC team, there were a limited number of patients who were seen by a free-standing PC clinic during the same time frame and were included in our analysis. Furthermore, we did not assess patients who were referred to outpatient PC and did not subsequently establish care with PC. Finally, our study is focused on patients with thoracic malignancies, and therefore may not be generalizable to all cancer types.

Despite the various limitations of our study, there are notable strengths to this analysis. First, this study may represent a more real-world experience of how embedded palliative care is implemented in a clinic, and even by telehealth. Secondly, our study attempted to capture outcomes throughout the continuum of care for patients with advanced cancer and still observed improved value-based metrics associated with PC. Finally, our analysis describes hospital charges in a state where hospital reimbursements are capped under the Maryland Global Budget Revenue. High-value interventions such as PC may be particularly relevant for states that are considering this type of reimbursement model in the future.

5. Conclusions

Value-based frameworks are increasingly considered in individual, system, and policy level decisions in cancer care. While the ASCO and the NCCN practice guidelines endorse early integration of PC for patients with advanced cancer, there are often barriers to providing this standard of care treatment such as availability of PC clinicians and funding challenges for PC services [

9,

10,

21,

22,

23]. Real-world implementation of outpatient embedded PC appears to be a high-value practice associated with improved hospital value-based metrics. Outpatient embedded PC, versus a free-standing PC clinic, may also be more patient-centric if aligned with oncology or infusion visits to reduce the burden of time, transportation, and associated costs to patients. Future studies are needed to understand the impacts of outpatient embedded palliative care on value-based metrics for health care systems and patient-reported outcomes. Likewise, value-based metrics, such as inpatient mortality, also require further investigation as to whether they lead to patient-centric goal concordant care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: High-risk zip codes in East Baltimore.

Author Contributions

**These two authors contributed equally. M.B., M.K., E.G., S.M., and J.F. designed the analysis. M.B., M.K., S.M., and J.F. extracted the data. E.G. performed the statistical analysis. M.B., M.K., E.G., I.B., and J.F. drafted and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins (IRB #00275889) on 03/17/2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the patients being deceased at the time of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the outpatient palliative care clinicians for our patients, including Dr. Ilene Browner, CRNP Denise Longo-Schoeberlein, Dr. Thomas Smith, and Dr. Sydney Dy, and the thoracic medical oncologists and radiation oncologists, including Dr. Julie Brahmer, Dr. David Ettinger, Dr. Patrick Forde, Dr. Christine Hann, Dr. Vincent Lam, Dr. Kristen Marrone, Dr. Jarushka Naidoo, Dr. Russell Hales, Dr. Khinh Voong and their clinical teams at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Conflicts of Interest

Josephine Feliciano: Consultant for AstraZeneca; Coherus Biosciences, Inc.; Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited; Eli Lilly and Company; Genentech, Inc.; Janssen Inc.; Johnson & Johnson; and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Grant/Research support from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers, Pfizer. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 17 registries, National Cancer Institute, 2022.

- Schnipper, L.E., et al., Updating the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework: Revisions and Reflections in Response to Comments Received. J Clin Oncol, 2016. 34(24): p. 2925-34. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.T., et al., Changes in Health Care Use Associated With the Introduction of Hospital Global Budgets in Maryland. JAMA Intern Med, 2018. 178(2): p. 260-268. [CrossRef]

- Palliative Care in Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/advanced-cancer/care-choices/palliative-care-fact-sheet.

- Thomas, T.H., et al., Communication Differences between Oncologists and Palliative Care Clinicians: A Qualitative Analysis of Early, Integrated Palliative Care in Patients with Advanced Cancer. J Palliat Med, 2019. 22(1): p. 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S., et al., Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med, 2010. 363(8): p. 733-42. [CrossRef]

- Greer, J.A., et al., Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin, 2013. 63(5): p. 349-63. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.S., et al., Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med, 2008. 168(16): p. 1783-90. Arch Intern Med. [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.R., et al., Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol, 2017. 35(1): p. 96-112. [CrossRef]

- Dans, M., et al., NCCN Guidelines Insights: Palliative Care, Version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2017. 15(8): p. 989-997.

- Smith, C.B., T. Phillips, and T.J. Smith, Using the New ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline for Palliative Care Concurrent With Oncology Care Using the TEAM Approach. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 2017. 37: p. 714-723.

- Gast, K.C., et al., Impact of an Embedded Palliative Care Clinic on Healthcare Utilization for Patients With a New Thoracic Malignancy. Front Oncol, 2022. 12: p. 835881.

- Census Bureau, U.S. Explore Census Data. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=0500000US48301&tid=ACSST5Y2019.S1901.

- Greenland, S., Introduction to Regression Models, in Modern Epidemiology, K.G. Rothman, S; Lash, TL, Editor. 2008, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia. p. 381-417.

- Szcklo, M.N., FJ, Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics. 3rd ed. 2014, Burlington: Jones and Bartlett.

- Brumley, R., et al., Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2007. 55(7): p. 993-1000. [CrossRef]

- Vranas, K.C., et al., Association of Palliative Care Use and Setting With Health-care Utilization and Quality of Care at the End of Life Among Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer. Chest, 2020. 158(6): p. 2667-2674. [CrossRef]

- Gade, G., et al., Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med, 2008. 11(2): p. 180-90. [CrossRef]

- Sedhom, R., et al., The Impact of Palliative Care Dose Intensity on Outcomes for Patients with Cancer. Oncologist, 2020. 25(11): p. 913-915. [CrossRef]

- Bakitas, M.A., et al., The TEAM Approach to Improving Oncology Outcomes by Incorporating Palliative Care in Practice. J Oncol Pract, 2017. 13(9): p. 557-566. [CrossRef]

- Schnipper, L.E., et al., American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: the top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol, 2012. 30(14): p. 1715-24. [CrossRef]

- Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: A literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):224-239. [CrossRef]

- Sedhom R, Kamal AH. Is Improving the Penetration Rate of Palliative Care the Right Measure? JCO Oncology Practice 18, no. 9 (September 01, 2022) e1388-e1391. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).