Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

01 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

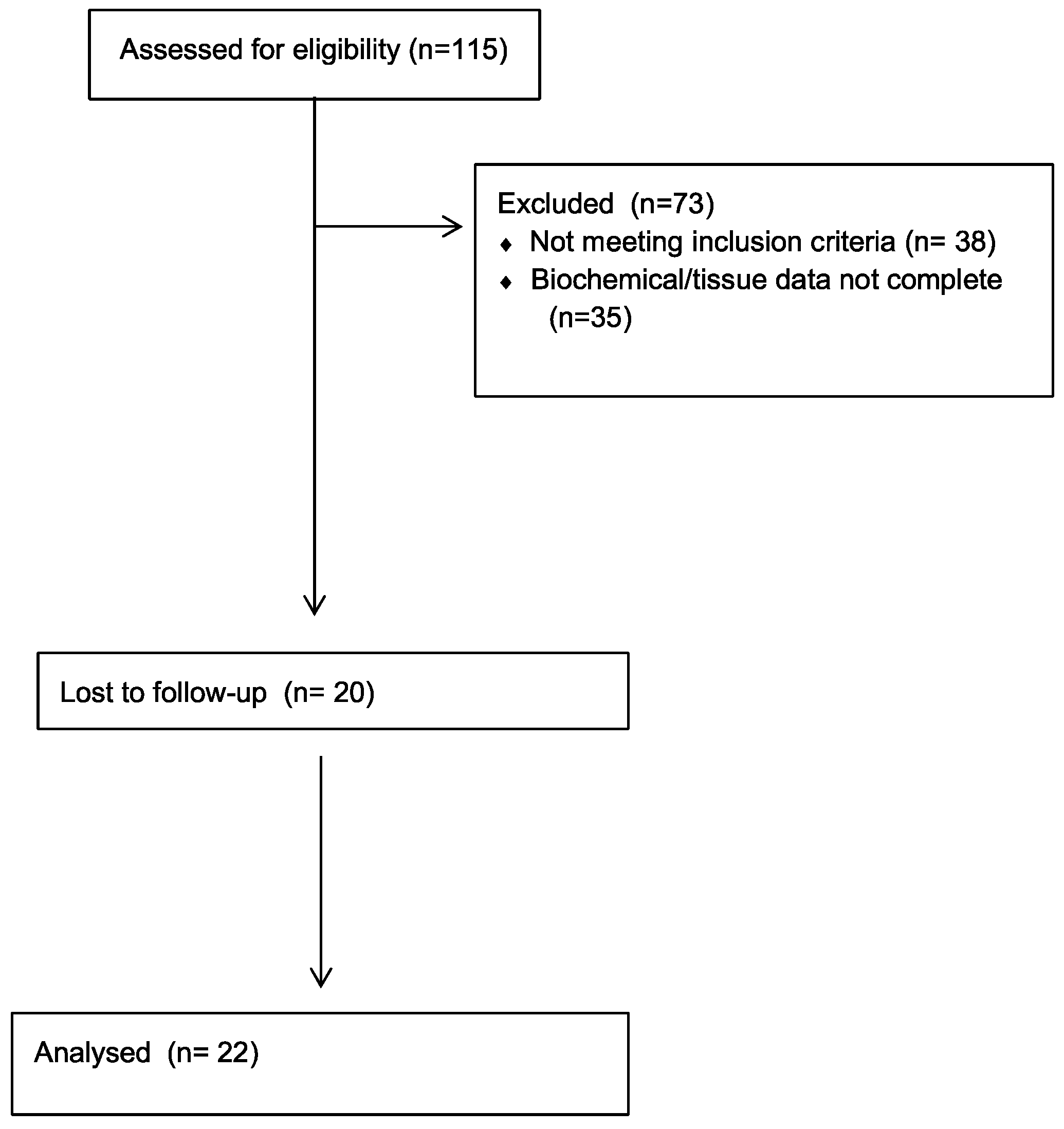

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tissue Samples

2.1.2. SA-β-Gal Activity on Cryopreserved Kidney Biopsies

2.1.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

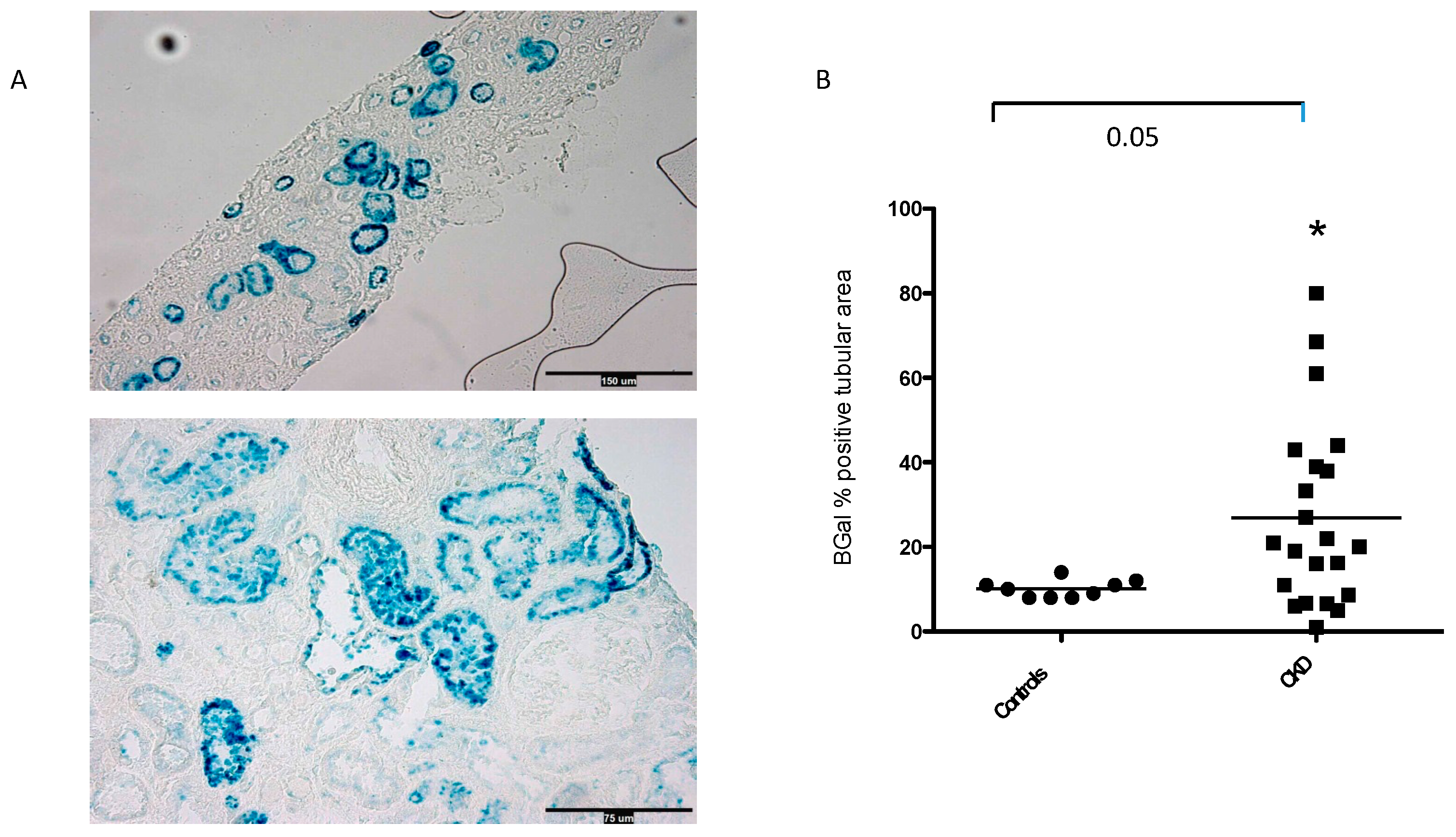

3.1. SA-β-Gal Staining in the Tubular Compartment

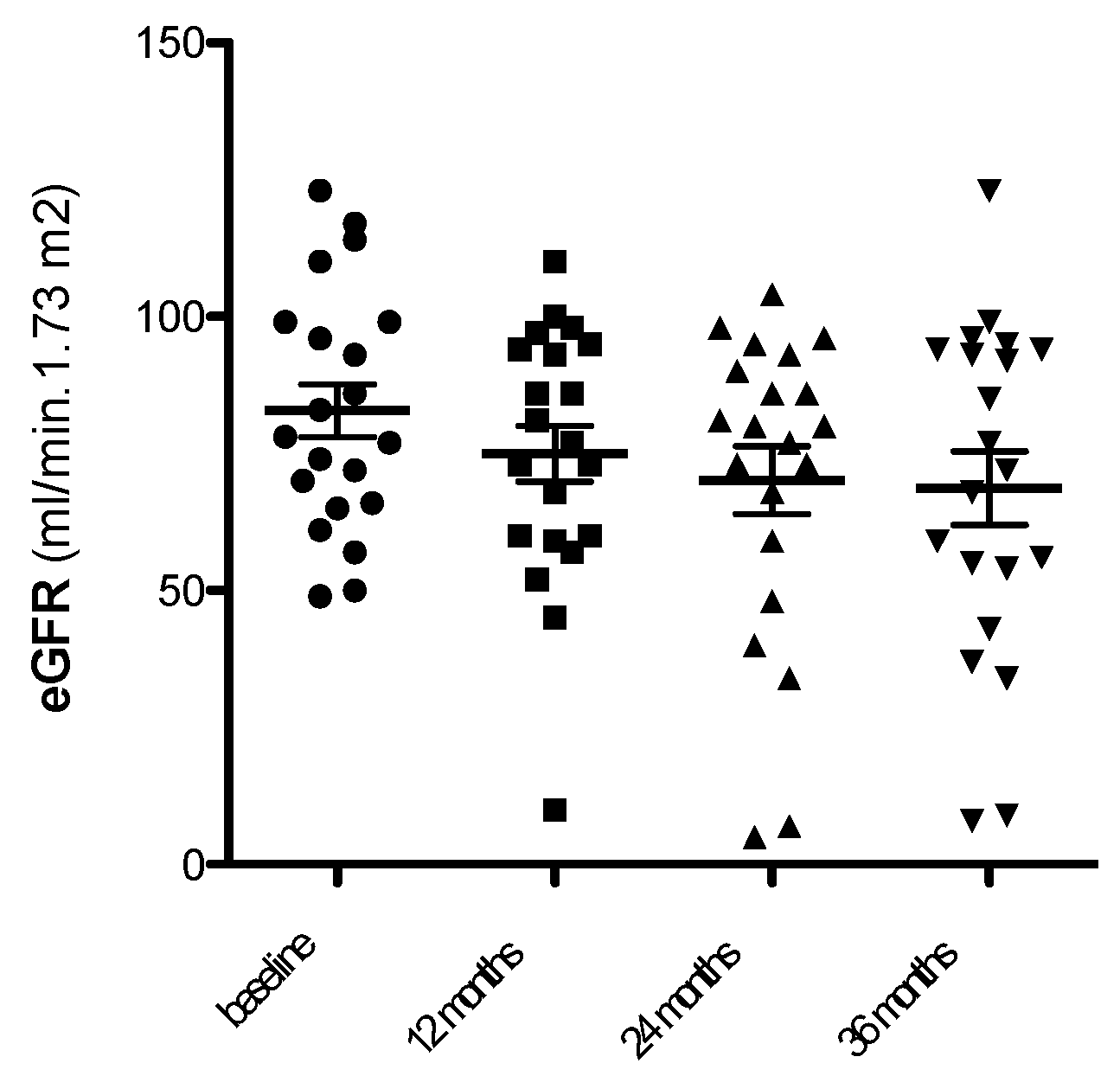

3.2. Clinical Correlates of SA-β-Gal Expression in Kidney Tubules

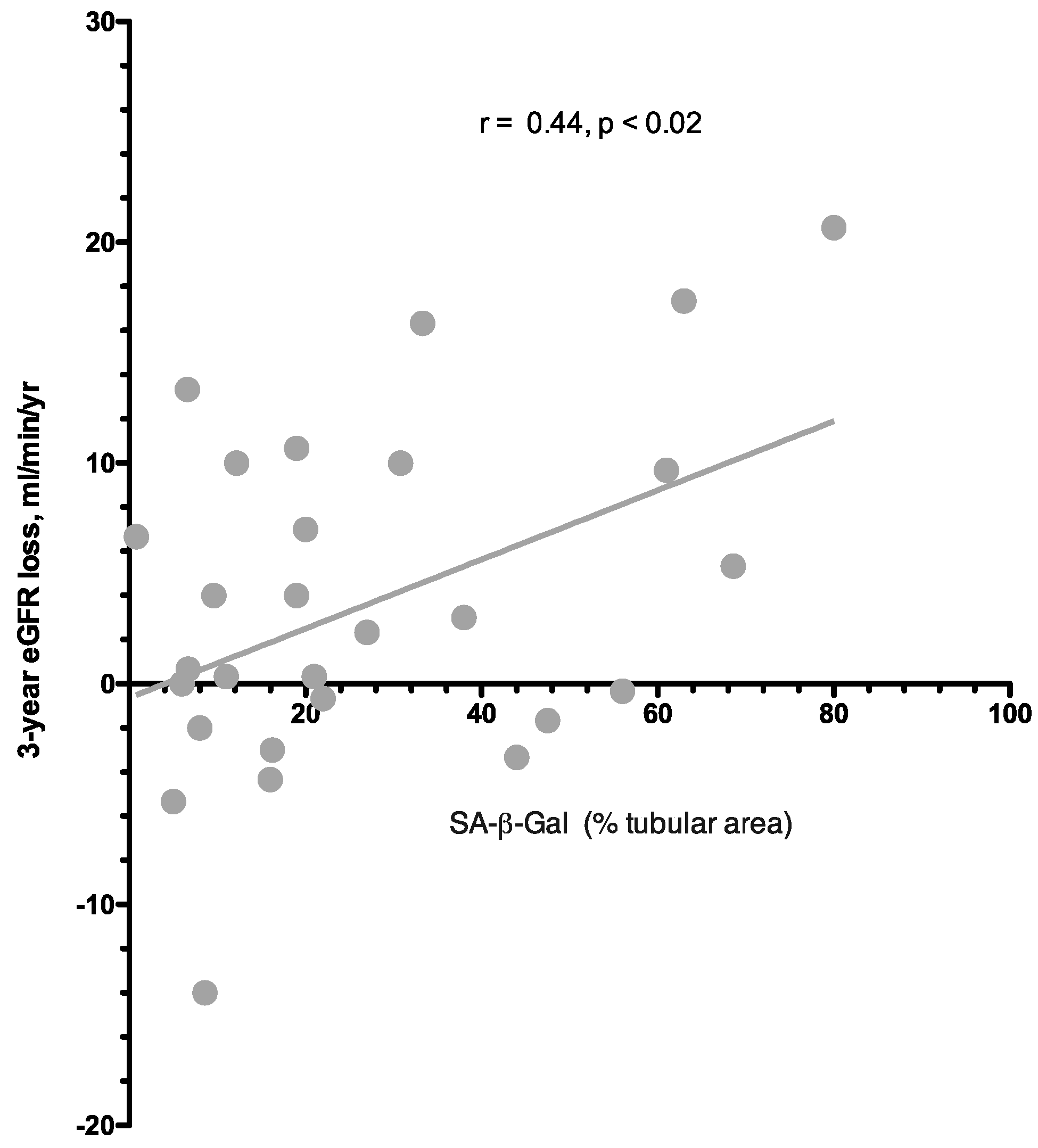

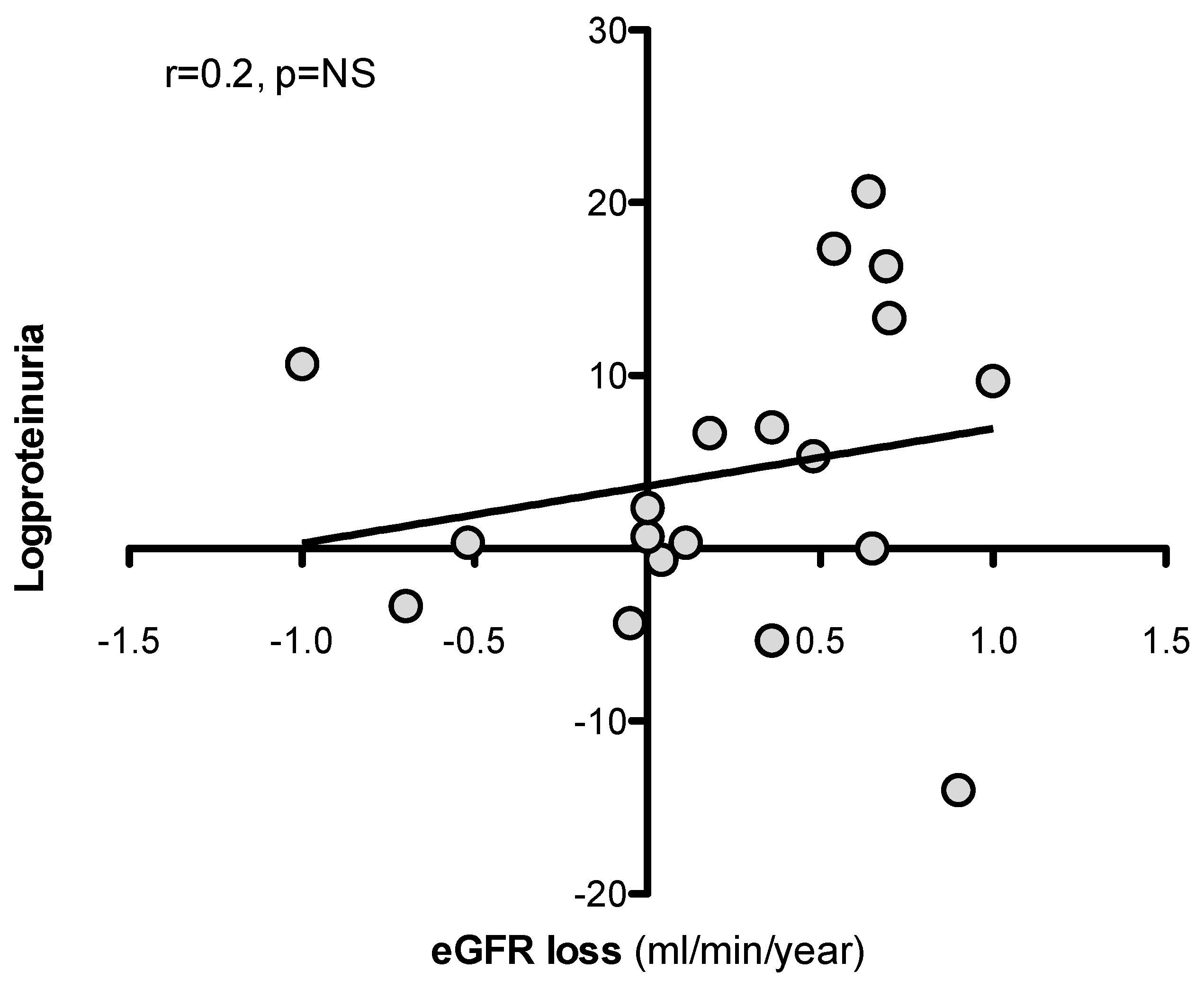

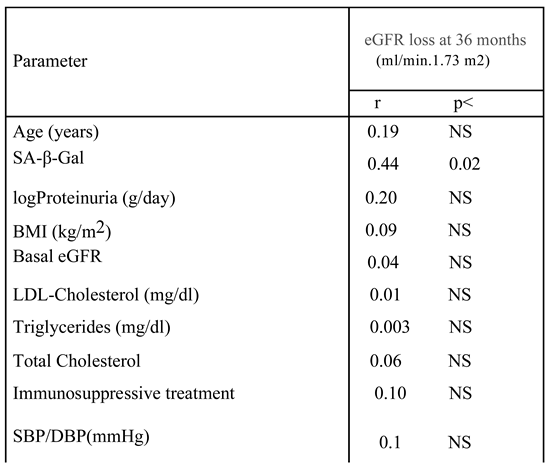

3.3. Predictors of eGFR Loss at 36 Months

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Melk A., Schmidt BM., Vongwiwatana A, et al. Increased expression of senescence-associated cell cycle inhibitor p16INK4a in deteriorating renal transplants and diseased native kidney. Am J Transplant 2005; 6:1375-82.

- Schmitt R., Melk A. Molecular mechanisms of renal aging. Kidney Int 2017; 92:569-579.

- Docherty M.H.; Baird D.P.; Hughes J., et al. Cellular Senescence and Senotherapies in the Kidney: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Front. Pharmacol 2020;11: 755-69.

- Dimri G.,P.; Lee X., Basile G., et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995; 92:9363-67.

- Coppé J.,P.; Patil C.,K.; Rodier F., et al. A human-like senescence-associated secretory phenotype is conserved in mouse cells dependent on physiological oxygen. PLoS One 2010;5:e9188.

- Childs B.,G.; Durik M.; Baker D.,J. et al. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med 2015; 21:1424-35.

- Yang L.; Besschetnova T.,Y.; Brooks C.,R. et al. Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med 2010;16:535–543.

- Melk A.; Schmidt B.,M.; Takeuchi O.; Sawitzki B.; Rayner D.,C.; Halloran P.,F. Expression of p16INK4a and other cell cycle regulator and senescence associated genes in aging human kidney. Kidney Int 2004;65:510–20.

- Docherty M.,H. ; O’ Sullivan E.,D. ; Bonventre J.,V. et al. Cellular Senescence in the Kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019 ;30: 726–736.

- Gorgoulis V.; Adams P.,D.; Alimonti A.; Bennett D.,C.; Bischof O.; Bishop C.; Campisi J.; Collado M.; Evangelou K.; Ferbeyre G.; Gil J,; Hara E.; Krizhanovsky V.; Jurk D,; Maier A.,B. ; Narita M.; Niedernhofer L.; Passos J.,F. ; Robbins P.,D.; Schmitt C.,A. ; Sedivy J. ; Vougas K. ; von Zglinicki T. ; Zhou D.; Serrano M.; Demaria M. Cellular Senescence: Defining a Path Forward. Cell 2019 ;179:813-827. [CrossRef]

- Gurung R.,L.; Yiamunaa M.; Liu S. et al. Short Leukocyte Telomere Length Predicts Albuminuria Progression in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Kidney Int Rep 2018;3:592-601.

- 12. Krishna DR, Sperker B, Fritz P, Klotz U. Does pH 6 β-galactosidase activity indicate cell senescence? Mech Ageing Dev 1999;109:113–123. [CrossRef]

- Verzola D., Gandolfo M,.T.; Gaetani G.; et al. Accelerated senescence in the kidneys of patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008;295:F1563-73.

- Debacq-Chainiaux F.; Erusalimsky J.,D.; Campisi J.; Toussaint O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc 2009;4:1798–1806. [CrossRef]

- Liu J.; Yang J.,R.; He Y.,N.; Cai G.,Y.; Zhang J.,G.; Lin L.,R.; et al. Accelerated senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells is associated with disease progression of patients with immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy. Transl Res 2012;159: 454–63.

- Verzola D.; Saio M.; Picciotto D. et al. Cellular Senescence Is Associated with Faster Progression of Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Am J Nephrol 2021;51:950-58.

- Verzola D.; Gandolfo M.,T.; Ferrario F.; et al. Apoptosis in the kidneys of patients with type II diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 2007;72:1262-72.

- O’Callaghan C.,A.; Shine B.; Lasserson D.,S. Chronic kidney disease: a large-scale population-based study of the effects of introducing the CKD-EPI formula for eGFR reporting. BMJ Open 2011; 1:e000308. 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000308.

- Li M.;Yang M.; Zhu W.,H. Advances in fluorescent sensors for β-galactosidase. Mater Chem Front 2021;5:763–774.

- 20. Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2014; 15: 482–496.

- D’Adda di Fagagna F.; Reaper P.,M.; Clay-Farrace L. et al. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature 2003;426:194-198.

- Miwa S.; Kashyap S.; Chini E.; von Zglinicki T. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cell senescence and aging. J Clin Invest 2022;132[13]:e158447. [CrossRef]

- Chiu C.,L. Does telomere shortening precede the onset of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive mice?. Hypertension 2008; 52:123–129.

- Cicalese S.,M.; da Silva J.,F.; Priviero F.,R. et al. Vascular Stress Signaling in Hypertension. Circulation Research 2021;128:969–992.

- Westhoff J.,H.; Hilgers K.,F.; Steinbach M.,P. et al. Hypertension induces somatic cellular senescence in rats and humans by induction of cell cycle inhibitor p16INK4a. Hypertension 2008;52:123-9.

- Garibotto G.; Carta A.; Picciotto D.; Viazzi F.; Verzola D. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling mediates inflammation and tissue injury in diabetic nephropathy. J Nephrol 2017;30: 719-727. [CrossRef]

- White W.,E.; Yaqoob M.,M.; Harwood S.,M. Aging and uremia: is there cellular and molecular crossover? World J Nephrol 2015; 4:19–30.

- Rhee J.,J.; Jardine M.,J.; Chertow G.,M.; Mahaffey K.,W. Dedicated kidney disease-focused outcome trials with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: Lessons from CREDENCE and expectations from DAPA-HF, DAPA-CKD, and EMPA-KIDNEY. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020; (Suppl 1):46-54. [CrossRef]

- Rossing P.; Caramori M.,L.; Chan J.,C.,N.; Heerspink H.,J.,L.; Hurst C.; Khunti K. et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: an update based on rapidly emerging new evidence. Kidney Int 2022; 102:990-999. [CrossRef]

- Xu M.; Pirtskhalava T.; Farr J.,N.; Weigand B.,M.; Palmer A.,K.; Weivoda M.,M. et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med 2018;24: 1246–56.

- Chan J.; Eide I.,A.;Tannæs T.,M. et al. Marine n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Cellular Senescence Markers in Incident Kidney Transplant Recipients: The Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Renal Transplantation (ORENTRA) Randomized Clinical Trial. Kidney Med 2021;3:1041-49.

- Koppelstaetter C.; Leierer J.; Rudnicki M.; et al. Computational Drug Screening Identifies Compounds Targeting Renal Age-associated Molecular Profiles. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2019;17:843-853.

| Clinical characteristics | SA-β-Gal (% tubular area) | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Age (years) | 0.08 | NS |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.05 | NS |

| eGFR (ml/min.1.73 m2) | −0.28 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.1 | NS |

| logProteinuria (g/day) | 0.27 | NS |

| LDL-Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 0.06 | NS |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 0.11 | NS |

| Total Cholesterol | −0.19 | NS |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.15 | NS |

| DBP(mmHg) | −0.09 | NS |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).