Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most prevalent cancer among men and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths [

1]. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has been established as the standard treatment for metastatic PCa [

2]. However, the efficacy of ADT varies among patients, and most patients eventually develop castration-resistant prostate cancer [

3]. The use of next-generation AR pathway inhibitors (ARPIs) prolongs overall survival and PSA progression-free interval in CRPC, but drug resistance still occurred after a period of ARPIs administration [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Following the widespread clinical use of the next generation ARPIs, the proportion of AR-null prostate cancer including neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) and double negative prostate cancer (DNPC) has subsequently risen as a means of drug resistance [

8].

NEPC histologically resembles small cell lung cancer (SCLC): small cells with deeply stained nuclei and increased nucleoplasmic ratio. Common immunohistochemical diagnostic markers for NEPC include CHGA, SYP, NSE, and NCAM1, which are positive, while AR is negative [

9]. However, not all NEPCs demonstrate positive NE markers. Unlike de novo NEPC, treatment-induced NEPC (t-NEPC) is derived from adenocarcinoma of the prostate (ADPC), as numerous studies have shown that t-NEPC share almost the same genomic alterations as ADPC (TMPRSS2-ERG fusion) [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Mechanically, current research indicates that transdifferentiation of adenocarcinoma can be categorized into two stages: firstly, tumor acquires lineage plasticity under the stress of ARPIs; secondly, tumor transdifferentiate into a NEPC, accompanied by the loss of reliance on the androgen signaling pathway [

14]. This process involves numerous molecular events. At the genomic level, TP53 and RB deletions exhibit significant prevalence in NEPC in comparison to ADPC. RB1 loss is typically noticeable in about 10% of cases in metastatic CRPC and is linked to poorer prognoses [

11]. In addition, the concurrence of PTEN deletion, TP53 mutations, and RB1 loss is associated with lineage plasticity and neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC), characterized by its highly resistant response to treatment [

11,

15]. ASCL1 and MYCN amplification are also involved in NETD [

13,

16,

17,

18]. Epigenetic modifications in NEPC, including histone methylation and acetylation, as well as DNA methylation, are pervasive [

14]. In NEPC, the histone methyltransferase EZH2 is highly upregulated, which results in an increased distribution of H3K27me3 and promotes the lineage plasticity of PCa [

17]. During the acquisition of lineage plasticity in PCa, lineage-related pathways, such as Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition (EMT), WNT/β-catenin, JAK/STAT signaling, and calcium signaling, are activated [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Currently reported NEPC drivers comprise ONECUT2, ASCL1, MYCN, PEG10, BRN2, SOX2, and HP1α [

16,

18,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. While molecular characteristics of ADPC and NEPC are relatively well understood, those of DNPC are not established [

28]. Current research has shown that FGFR signaling may help AR-null prostate cancer to bypass AR signaling [

28].

ID2 has been widely researched in various diseases, and its molecular function is linked to cellular growth, senescence, differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and neoplastic transformation. In glioblastoma, the oncoprotein N-Myc increases ID2 expression and binds with Rb, resulting in its deactivation and subsequently promoting cell cycle progression [

29]. Dephosphorylated ID2 decreases self-degradation, resulting in increased intracellular levels and promoting the proliferation of neural precursor cells [

30]. ID2 decreases intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production through the inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria, thus promoting tumor cell survival in glioblastoma [

31]. ASCL1 upregulates the expression of ID2 in SCLC [

32]. However, ID2's role in NEPC has not been reported in any study. Given the comprehension of the molecular mechanisms involved in NETD and the significance of ID2 in various cellular biological processes, we carried out a study to examine the function of ID2 in the process of lineage transition of prostate adenocarcinoma.

Results

ID2 expression is upregulated in NEPC and DNPC.

To explore ID2 expression level across different prostate cancer cell line, we mined RNA-seq data from CCLE. Transcriptional sequencing data of these four cell lines were obtained from the CCLE database to compare the expression levels (TPM) of ID2. We found that ID2 transcript levels were lowest in the LNCAP cell line, which is a hormone-sensitive cell line, whereas in PC3 and 22RV1 (hormone-resistant cell lines), ID2 expression levels were elevated, and the highest levels of ID2 expression were found in NCI-H660, a de novo small cell neuroendocrine prostate cancer cell line [

33] (

Figure S1a). We next performed dual immunofluorescence analysis of ID2 and CHGA on samples from clinical neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the prostate, with the former being positive for CHGA and strongly positive for ID2, whereas in the latter, it was negative for CHGA and weakly positive for ID2 (

Figure 1a,

Figure S1b). We then mined the expression of ID2 in Beltran's data [

13], and the expression level of ID2 in CRPC-NE was significantly higher than that in CRPC-AD (

Figure 1b).

Given that only a fraction of PCa after ARPIs administration acquired resistance through neuroendocrine transdifferentiation (NETD), we investigated the differences in altered expression levels of ID2 in NETD PCa and other PCa that acquired resistance through other mechanisms. We mined RNA sequencing data from 21 paired samples after enzalutamide treatment, of which 3 samples had histologically confirmed transdifferentiation to neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC), while the remaining 18 did not develop NETD [

34]. In the 3 samples with NETD, ID2 expression levels were elevated (

Figure 1c), while in the remaining 18 samples without NETD, ID2 expression levels were either elevated or decreased, with non-significant differences.

To determine whether there exists difference in the state of chromatin in the ID2 genomic region in NEPC and ADPC, we mined CHIP-seq data for H3K27ac from a series of LuCaP PDX mice and found that NEPC has a more significant H3K37ac signal peak near the ID2 gene (

Figure 1d). H3K27ac is a histone modification that enhances gene expression and this epigenomic characteristic in NEPC is consistent with the above results of elevated transcript levels of ID2 in NEPC [

35].

To explore the differences in pathways in ID2 high-expressing tumors, 499 TCGA tumors were subjected to GSEA and grouped based on the median expression level of ID2, which showed that the activity of neurological pathways such as neuron projection guidance, regulation of neurogenesis was higher in the high-expressing group (

Figure 1e).

Transcriptomic reprograming and pathway analysis upon ID2 overexpression.

We first investigated whether ID2 induces changes in gene expression patterns. According to PCA analysis, samples with ID2 overexpression showed differences from the control group in terms of principal components. The findings revealed that ID2 leads to alterations in cellular transcription patterns (

Figure 2a). Differential analysis was performed using edgeR. 865 differential genes were identified, of which 772 were up-regulated genes and 93 were down-regulated genes (

Figure 2b). Result of differential analysis is shown in Supplementary Table 1. We analyzed the expression of the top 20 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in a panel of PCa cell lines (

Figure 2c). Heatmap demonstrates that these DEGs are moderately higher expressed in NE like PC3 cell, DU145, NCI-H660 cells. The most differentially upregulated genes were IFI6 and IFI27, which play an important role in apoptosis and may promote growth and migration of tongue squamous cell carcinoma [

36]. Notably, we also found a significant down-regulation of HOXB13, an androgen co-stimulatory factor, the absence of which leads to lipid accumulation in prostate cancer cells, which increases cell motility and causes metastasis in xenograft tumors [

37]. In addition, we stably transfected ID2 in LNCAP cells and cultured it with charcoal-stripped serum, we found that cells underwent axon generation and HOXB13 expression was downregulated (

Figure 2d, e).

Next, we aimed to know whether ID2 activates or inhibits certain pathways in PCa cells, which in turn influences its biological function. We perform GSEA using hallmark pathways from MsigDB and found that a total of 20 pathways were significantly activated or inhibited (

Figure 2f). Immune-related pathways such as IFN-α, IFN-β, inflammatory response was top significantly activated in ID2 overexpression group, and stemness-related pathways including IL-6/Jak/Stat3 signaling, TGF-β signaling. This finding was consistent in activated hallmark pathways with genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) that recapitulate the lineage transition [

38].

Most transcription factors exert their function through its modifier status without changing its expression, as RNA-seq data fails to capture post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications. Therefore, we conduct master regulator analysis to identify changes of major TF activity after ID2 overexpression, which identifies 69 activated master regulators (Supplementary Table 2). Top activated transcription factors are HMX1, TLX1, CRX (

Figure 2g). To confirmed whether these activated master regulators play more critical role in clinical de novo NEPC than ADPC, we conducted expression analysis and identified 1225 DEGs (Supplementary Table 3). Then, we took the intersection of these differentially expressed genes and the above master regulators and identified four genes, of which, ASCL1 and NKX2-1 have been confirmed to be NETD drivers by related studies [

35] (

Figure S2). Enrichment analysis of these activated regulators shows an activation in pathways associated with nervous system development and endocrine development (

Figure 2h).

ID2 attenuates AR signaling and promotes NETD.

Based on the fact that the AR pathway is less active in NEPC [

39],we then aimed to determine whether ID2 will exert a role on that. We transiently expressed ID2 in a panel of prostate cancer cell lines, western blot analysis showed decreased expression of AR and PSA in LNCAP cell, while the expression of NE markers such as CHGA, ENO2 and SYP was elevated in both LNCAP and PC3 cell (

Figure 3a). Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis showed a significant decrease of AR after overexpression in C42B cell (

Figure 3b). In 22RV1 cell, we knocked down ID2, qPCR showed that PSA and AR expression level was decreased, indicating decreased activity of AR signaling (

Figure 3c).

Next, we did transcriptome sequencing analysis of ID2 overexpressing PC3 cells, and GSEA show that Androgen response pathway was suppressed (

Figure 3d). We noticed that HOXB13 expression is downregulated in the transcriptomic data, which is an AR co-factor and highly expressed in benign prostatic tissues and ADPC, while expression is decreased or absent in NEPC (

Figure S3) and is reported to accelerate NETD [

40]. On the premise that Calcium signaling is activated in NEPC [

22], we then examined the calcium level in C42B cell and IF analysis shows a significant increase after ID2 overexpression (

Figure 3e).

In addition, we evaluated the NE scores of 499 primary prostate adenocarcinoma cases in the TCGA database. Using Beltran's NE gene set [

13], a single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was performed on prostate tumor samples, with higher scores indicating a higher likelihood of NETD, and then the NE score of each sample was correlated with the ID2 expression level. We found that the NE score of the samples had a significant positive correlation with the expression of ID2 (

Figure 3f). Similarly, the SU2C2019 data also showed a significant positive correlation between ID2 and NE score, and a significant negative correlation with AR pathway activity, as assessed by the 5-gene score [

41] (

Figure 3g).

To determine whether ID2 promotes tumor growth in vivo, we transplanted long term ID2-overexpressiong PC3 cells and control cells into nude mice, tumor volume growth curve showed that ID2 can increase growth rate of PCa (

Figure 3h).

ID2 enhances PCa cells aggressiveness.

To investigate the effect of ID2 on the common hallmark phenotype of PCa cells, we first transiently expressed ID2 in PC3 cells. CCK8 experiments showed that ID2 could promote the proliferation of PC3, while in LNCaP cells, ID2 inhibited its proliferation (

Figure 4a, b). This seemingly contradictory result was consistent with the above results that ID2 could inhibit the AR signaling pathway. Because LNCaP is a hormone-sensitive cell line, ADT can inhibit its proliferation, whereas PC3 is a hormone-resistant cell whose growth does not depend on the androgen signaling pathway. But after long term overexpression of ID2 with ADT, this inhibitory effect could be reverted. In the meantime, it can also eliminate cellular contact inhibition and confer resistance of enzalutamide to LNCaP cell (

Figure 4c). Similarly, transient expression of ID2 also had different effects on the migratory ability of different PCa cell lines. It inhibited the migratory ability of LNCaP but increased the migratory ability of PC3 cells (

Figure 4d, e). However, the results of invasion assay showed consistency: Although ID2 inhibited the proliferation and migration of LNCaP cells, it enhanced its invasion ability (

Figure 4e), which was consistent with the results of invasion assay of PC3. Meanwhile, we also demonstrated the role of ID2 in terms of EMT. Western blot showed reduced E-cadherin expression and increased β-catenin expression in ID2 stably overexpressing LNCaP cells cultured in charcoal stripped serum (CSS) median (

Figure 4f), indicating it can promote epithelial mesenchymal transition. Consistently, ssGSEA score of the AR repressed signature and RB loss up signature were elevated in ID2 overexpressing PC3 cell.

ID2 UP50 signature generation and validation of its effectiveness

Next, we focused on the most significantly upregulated genes by ID2. We generated a ID2 UP50 signature by corporate top 50 upregulated DEGs (Supplementary Table4). This signature trended upwards in CRPC and de novo NEPC cell line versus HSPC (

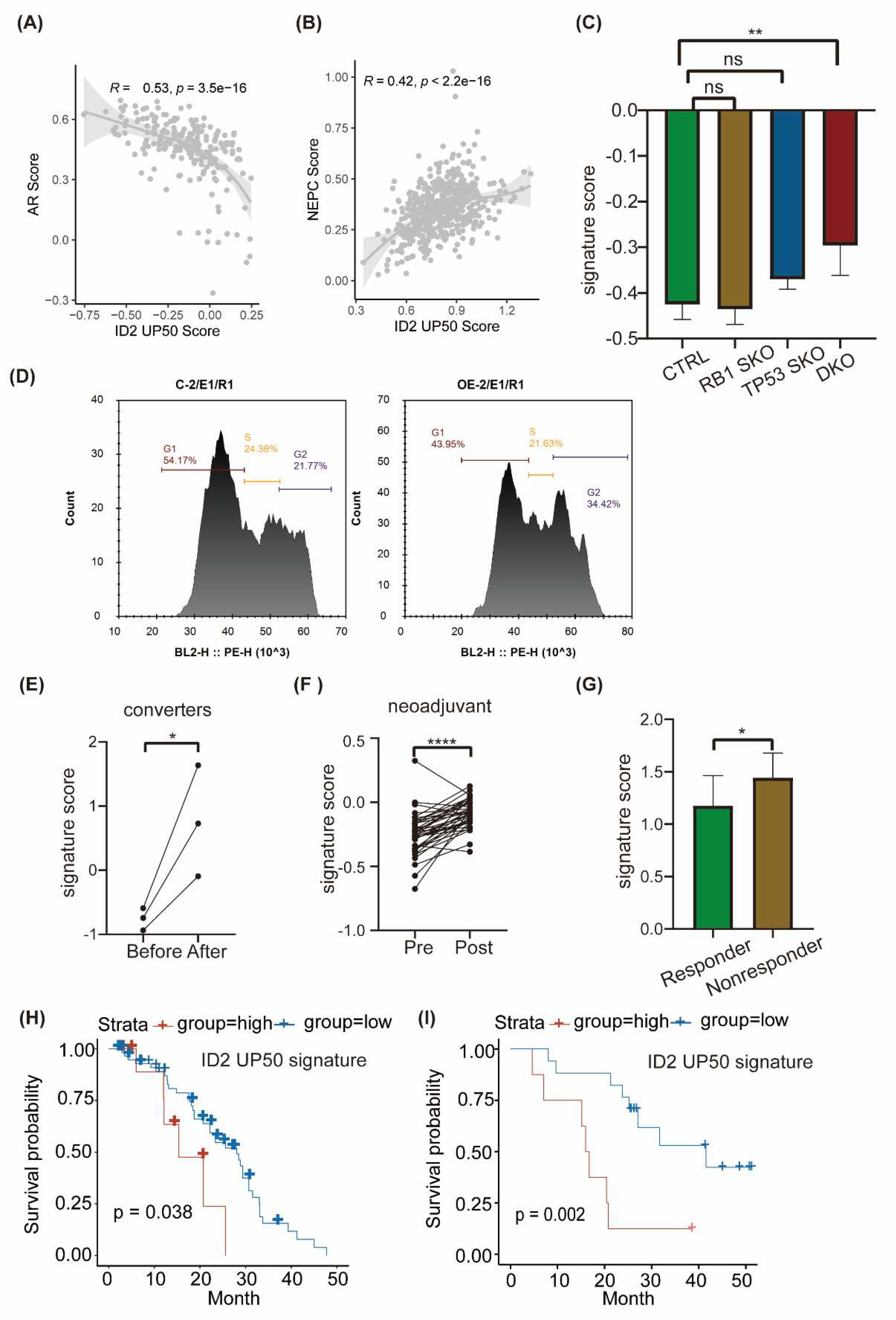

Figure S4a), which further suggests that ID2 can confer drug resistance through NETD. To test its competence to infer NETD probability, we performed ssGSEA on samples from SU2C2019 and TCGA.

We determined whether this signature could classify NEPC and ADPC by calculating signature score in samples with NE features or not. The SUC2C cohort doesn’t show significant difference of ID2 signature score in NE and Adeno phenotype (

Figure S4b), we hypothesized that some of adeno-samples may have been in the early stage of NETD because of drug administration, thus its transcriptomic profile has changed but terminal histological transformation has not. (from canonical adenocarcinoma morphology to small cell NEPC). Instead, we performed correlation analysis with ID2 signature score and NEPC score in SU2C cohort and found ID2 signature score is negatively correlated with AR score and positively correlated with Beltran NEPC UP score (

Figure 5a, b).

Previous studies have shown that loss of RB1 and TP53 is more frequent in NEPC compared to ADPC, but this genomic event is not an obligatory drive to neuroendocrine transdifferentiation, as a sub proportion of RB1

-/- TP53

-/- CRPCs loci doesn’t show an increase of NE marker such as SYP, CHGA. We thus performed expression analysis in LNCAP DKO models. Results show that ID2 UP50 signature score is not significantly changed in RB or TP53 single knock out LNCAP cell, but after RB and TP53 double knock out, it was significantly raised concomitant with EZH2 expression, a known NEPC drivers. (

Figure 5c,

Figure S4c). On the premise that ID2 can inactivate Rb to promote cell cycle progression in glioblastoma [

29], we wondered that whether it can also bind to Rb in prostate cancer. We confirmed that Id2 can binds to Rb in LNCaP cell and can promote cell cycle progression (

Figure 5d, e).

PCa can acquire enzalutamide resistance through different mechanisms, as it appears heterogeneous effects on transcriptomic profile, which can be characterized by different clusters that represent different phenotypes [

34]. We acquired RNA-seq data of matched samples that undergone NETD and found its signature score is significantly upregulated after NETD (

Figure 5f). On another cohort that undergone neoadjuvant therapy of enzalutamide, the signature score was also elevated after treatment (

Figure 5g). Besides, this signature could also shed light on whether patients will respond to enzalutamide, as it scored higher in enzalutamide non-responder than responder (

Figure 5h)

To explored whether the ID2 UP50 signature can predict clinical outcomes of PCa patients, we acquired clinical data from Abida [

42] and Alumkal [

43], then calculated each patient’s sample signature score and defined patients with top decile or median score as exposure group, survival analysis showed that exposure group have an unfavorable clinical outcome (

Figure 5i, j).

ID2 activates FGFR signaling and JAK-STAT signaling to promote lineage transition.

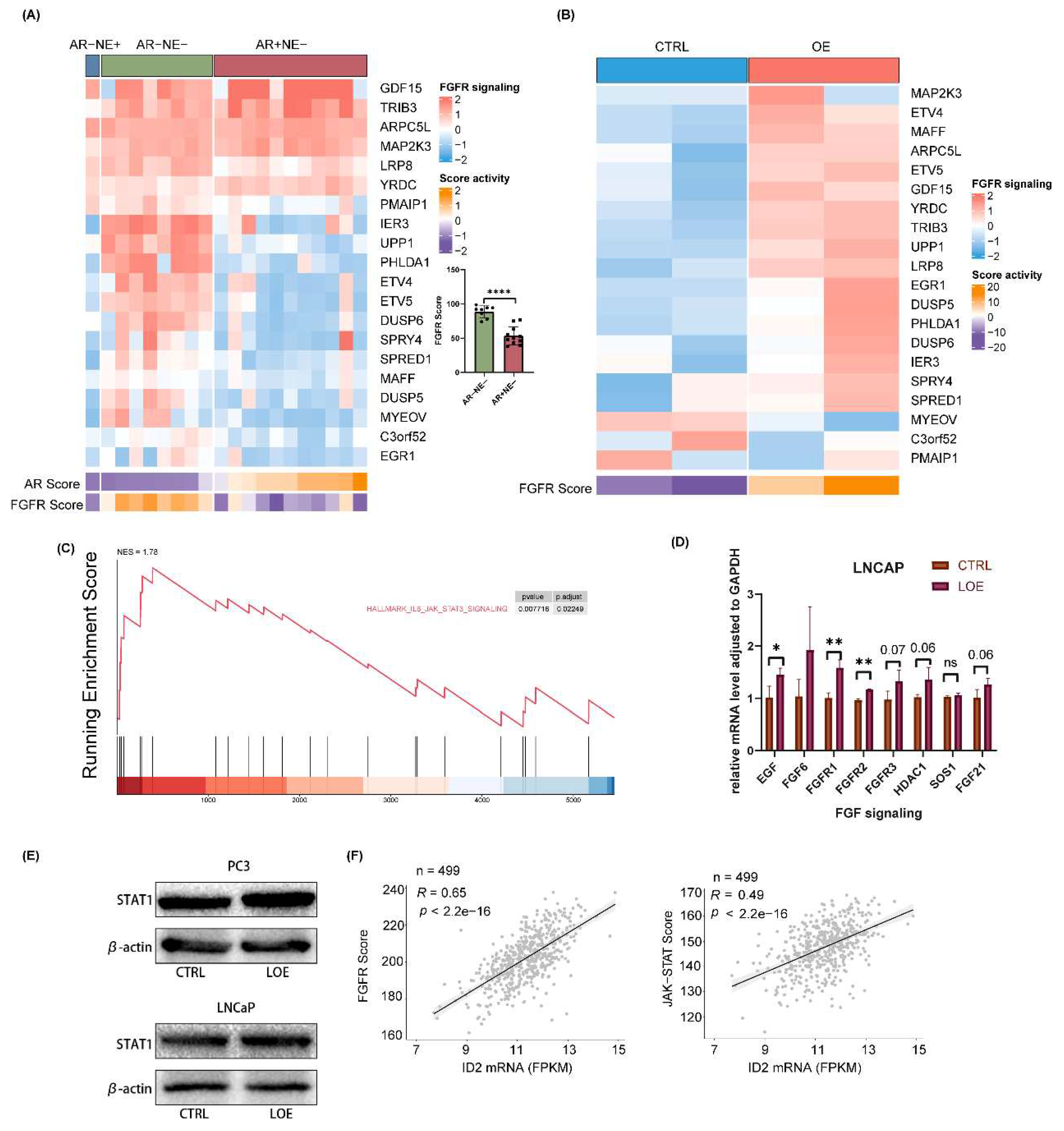

Bluemn’s research demonstrates that AR-null prostate cancer is sustained through FGFR signaling [

28]. Here, we explored the status of FGFR signaling in a panel of 20 prostate cancer cell lines. By clustering them into 3 phenotypes according to AR activity and NE activity, we found that FGF signaling is significantly activated in AR-null prostate cancer cells including DNPC and NEPC (

Figure 6a). Next, we examined FGFR signaling changes after ID2 overexpression. Our data showed that FGFR signaling is more active upon ID2 (

Figure 6b). Given that JAK-STAT activation confers stemness to prostate adenocarcinoma [

21,

44], we performed GSEA on our data by using its associated gene set and found it was activated after ID2 overexpression (

Figure 6c). To further verified FGFR signaling and JAK-STAT signaling activation, we performed ectopic expression in LNCaP cell lines, results of qPCR and western blot showed consistency in LNCaP and PC3 cell (

Figure 6d, e). We next examined FGFR and JAK-STAT activity in clinical samples from TCGA and found that it was positively correlated with ID2 level (

Figure 6f).

Discussion

The application of the new generation of ARPIs has improved the prognosis of patients on the one hand, but on the other hand it has led to an increase in the clinical rate of AR-null prostate cancer, a refractory pathological type of PCa that is ineffective against commonly used androgen deprivation therapies. The current main treatment for AR-null prostate cancer is platinum-based chemotherapy, which is rapidly becoming resistant.

The gene level, epigenetic, transcriptional and protein levels are all involved in the transdifferentiation process of PCa and are highly heterogeneous. Therefore, the discovery of universal mechanisms is crucial. Through multiple RNA sequencing datasets, we found elevated transcript levels of ID2 in AR-null PCa and confirmed it at the protein level through our clinical specimens. In addition, we also mined epigenomic CHIP-seq of H3K27ac data and result showed that the ID2 genome was also more active in NEPC. Next, we explored the altered intracellular transcriptional patterns induced by ID2 using RNA sequencing to explore the mechanism of lineage transition, and enrichment analyses showed that the pathway activated by ID2 was associated with neurodevelopment and that the AR pathway was repressed. Master regulator analysis suggested elevated protein activity of ASCL1 and NKX2-1, which are transcription factors for neural spectrum development. Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway suggests that ID2 can also promote lineage plasticity in PCa. There are numerous studies showing the presence of a higher proportion of RB1 and P53 mutations in NEPC. Using immunoprecipitation, we confirmed that ID2 can interact with RB1, which may lead to its inactivation.

Phenotypic studies showed that ID2 has different effects in several PCa cell lines, and we speculated that such differences might be due to variations in the biological background of the cells. LNCaP is an androgen-dependent cell, and our pathway analyses showed that ID2 could inhibit the AR pathway, so the results of the CCK8 experiments showed that the growth of LNCaP was inhibited by ID2, and the ability of the cells to migrate was relatively decreased, but the invasive ability of LNCaP was slightly increased. However, the invasive ability of LNCaP was slightly increased. As for PC3 cell, an androgen-independent cell that is insensitive to enzalutamide, ID2 increases its malignancy in terms of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. In vivo experiments also showed that ID2 could promote tumor growth.

Finally, we generated an ID2 signature based on DEGs and verified its effectiveness in several ways. We confirmed that the ID2 signature scored higher in the NEPC sample than ADPC sample. Correlation analysis showed that ID2 signature was positively correlated with NEPC signature and negatively correlated with AR signature. Through clinical patient survival data and corresponding sequencing sample data, we verified that patients with high ID2 signature score have an unfavorable clinical outcome.

Methods

Cell culture

LNCaP, 22RV1, C42B and PC3 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). LNCaP clones were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1% penicillin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or 5% charcoal stripped serum for ADT. 293T cells were cultured in DMEM. For in vitro ARPIs, cells were treated with 10 μmol/ENZ and harvested at the indicated time points. Drugs were all obtained from MCE (China).

Animal studies

All animal studies received prior approval from the IACUC of Washington State University and complied with IACUC recommendations. Male 4- to 6-week-old nude mice were housed in the animal research facility. 1×106 ID2-overexpressing PC3 cells or control cell were injected to injected subcutaneously into the flank of nude mice. Each group contained 8 mice. Tumor size was measured every 2-3 days by caliper after the tumor was formed. Tumor volume was calculated as length × width2/2.

Western blot

Total proteins were extracted from cells using RIPA buffer (Cat# P0013C, Beyotime) supplemented with protease inhibitor (1:100, Cat# ZJ101, EpiZyme Biotechnology, China). Protein concentration was measured by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat# 23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein were separated by electrophoresis on 10% or 15% polyacrylamide gels (Cat# PG112, PG114 EpiZyme Biotechnology, China) according to protein mass, transblotted onto 0.22 nm or 0.45 μm polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and incubated with antibodies against ID2 (1:1000, Cat# 3431S, Cell Signaling Technology), FLAG (1:1000,Cat# AF519, Beyotime), GAPDH (1:1000, Cat# sc-365062, SANTACRUZ), SYP(1:1000, Cat# sc-365488, SANTACRUZ), ENO2(1:1000,Cat# 24330T, Cell Signaling Technology), CHGA (1:1000, Cat# 60893S, Cell Signaling Technology), EZH2 (1:1000, Cat# 5246S, Cell Signaling Technology), AR(1:1000, Cat# ab108341, Abcam), PSA (1:1000, Cat# 5365T, Cell Signaling Technology), E-cadherin (1:1000, Cat# sc-8426, SANTACRUZ), N-cadherin(1:1000, Cat# sc-8424, SANTACRUZ), Vimentin (1:1000, Cat# D21H3, Cell Signaling Technology), Snail (1:1000, Cat# C15D3, Cell Signaling Technology), HOXB13 (1:1000,Cat# TA364479S, origene), RB1 (1:1000, Cat# 9313T, Cell Signaling Technology), at 4°C overnight. Afterward, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:3000, Cat# 7074S, Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-mouse IgG (1:3000, Cat#7076S, Cell Signaling Technology) secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. In some experiments, the previous primary antibody and secondary antibody were stripped from the PVDF membrane with stripping buffer (Cat# PS107S, EpiZyme Biotechnology, China) for 10~15 min. After being re-blocked, the membrane was re-incubated with another primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The following steps were the same as described above.

Cell proliferation assay

CCK8(Cat# BR3001507) assay was applied to measure cell viability. 2000 or 4000 cell was seeded into 48 or 96 well plate and were cultured as indicated in the Figures. At 0, 24, 48, 72, 96h, 10 μl or 20 μl CCK-8 working solution were added to each well, and incubated for 2 h at 37˚C. Optical densities were then measured at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Cell invasion assay

Cell invasion was assessed by utilizing Matrigel-coated BioCoat Cell Culture Inserts (24-well plates, Corning). Once Matrigel had been rehydrated at room temperature, 2x105 cells, suspended in 200 μl of RPMI-1640 medium, were seeded into each insert. At the base of each well, 500 μl of medium containing 20% FBS was added. After 48 hours of culture, non-invading cells were removed, and the cells on the lower side of the membrane were subsequently stained with crystal violet.

Cell migration assay

Cell migration was assessed in a wound-healing assay. Cells were plated on 6-well plates and incubated for 24, 48 or 72 hours after wound scratching. Wound confluence was captured at different time points using NIS-Elements Viewer. Wound closure was measured using ImageJ by comparing the mean relative wound density of three replicates.

RNA-seq and data analysis

Total RNA of PC3 and LNCaP cells was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (74106, Qiagen) following manufacturer’s procedure. Whole transcriptome sequencing libraries were prepared using TruSeq® Stranded mRNA Library PrepKit (RS-122-2101, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA-Seq libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq2500 at Princess Margaret Genomic Centre. The trimmed reads were aligned to human genome hg38 with HISAT2 and gene expression was then quantified using the fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM) method by Cufflinks (version 2.1.1) with GENCODE v24 GRCh37 GTF file.

Differential analysis was performed using edgeR package and DEGs was defined as | log Foldchange | > 1 and adjusted p.value < 0.05. GSEA was performed using the hallmark gene sets from version 4.0 of the molecular signature database (MSigDB). Master Regulator Analyses were performed by comparing ID2 overexpressing samples and control samples with the MARINa algorithm implemented in viper R package. The regulon was acquired through arcane.networks R package.

Signature score calculation

In this study, we used several gene signatures collected from public resources, including the Beltran NEPC Up gene signature; 76 gene AR-repressed signature; and the Chen, et al. RB1 loss signature [

45,

46]. The signature genes are listed in Supplementary Table 6. Summed z-score or ssGSEA are applicated to calculate signature activity. FPKM gene expression values were used as input of gsva function implemented in GSVA R package with ‘ssGSEA’ method to calculate each sample’s signature score.

Clinical data analysis

The Abida and Alumkal cohort clinical data was utilized for analysis of prognostic features. Kaplan–Meier curves were estimated using the survfit function implemented in survival R package and plotted using survminer R package. Tumors were stratified in two ways. The first was into two groups of the top decile of ID2 Up signature scores versus the remainder and the second was into median of ID2 signature score. The logrank test was used to test for differences between survival curves.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Tissue RNA Purification Kit (EZBioscience) and 1 μg was reversed transcribed using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TaKaRa). Real-time PCR was performed using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme). Target gene expression was normalized to GAPDH levels in three experimental replicates per sample. For primer sequences, please see

Supplementary Table S7.

Overexpression

The CDS sequence of ID2 was obtained through NCBI, followed by amplification using the Hieff CloneTM One Step Pcr Cloning Kit (YEASEN cat# 10911ES20). The target sequence was recombined with the double digested vector. The recombinant plasmid was transferred into transiently transfected cells using lipo3000, and the medium was changed after 6 h. The transfection efficiency was detected after 48 or 72 h using WB or qPCR. For stable overexpression, lentivirus was packaged using ID2 overexpression vector, psPAX2 and pMD2G vector.

shRNA knockdown

ID2-targeting short hairpin RNAs (ID2-shRNA) and a nonspecific control (scramble) were constructed using a PGMLV-SB3 RNAi lentiviral vector. Sequences of ID2-shRNAs are listed in supplementary Table 8. lentiviral vectors were co-transfected with psPAX2 and pMD2G vectors into HEK293T cells. Supernatants were collected at 24 and 48h after transfection. For infection, 5×104 cells were seeded in six-well plate and infected with lentiviral supernatant on the following day. Lentivirus, plasmid, and siRNAs were purchased from Genomeditech, Shanghai, China.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables can be accessed through Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

JZ, LS, and JW contributed to the study conception and design. JZ carried out the analysis and wrote the manuscript. LS had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alumkal (Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science University) for providing patient's survival data and Yan Gu (Huadong hospital, Fudan University) for providing clinical samples.

References

- Sung, H. , et al., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021. 71(3): p. 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Tannock, I.F. , et al., Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 351(15): p. 1502-12. [CrossRef]

- Klotz, L. , et al., Nadir testosterone within first year of androgen-deprivation therapy ( ADT) predicts for time to castration-resistant progression: a secondar y analysis of the PR-7 trial of intermittent versus continuous ADT. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Societ y of Clinical Oncology. 33(10): p. 1151-6. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.J. , et al., Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherap y. The New England journal of medicine. 368(2): p. 138-48. [CrossRef]

- Scher, H.I. , et al., Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemothe rapy. The New England journal of medicine. 367(13): p. 1187-97. [CrossRef]

- Beer, T.M. , et al., Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. The New England journal of medicine. 371(5): p. 424-33. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R. , et al., Apalutamide Treatment and Metastasis-free Survival in Prostate Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 378(15): p. 1408-1418. [CrossRef]

- Vlachostergios, P.J., L. Puca, and H. Beltran, Emerging Variants of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Current oncology reports. 19(5): p. 32. [CrossRef]

- Rickman, D.S. , et al., Biology and evolution of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Nat Med, 2017. 23(6): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Beltran, H. , et al., Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov, 2011. 1(6): p. 487-95. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.L. , et al., Rb loss is characteristic of prostatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2014. 20(4): p. 890-903. [CrossRef]

- Hansel, D.E. , et al., Shared TP53 gene mutation in morphologically and phenotypically distinct concurrent primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Prostate, 2009. 69(6): p. 603-9. [CrossRef]

- Beltran, H. , et al., Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med, 2016. 22(3): p. 298-305. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R., X. Dong, and M. Gleave, Molecular model for neuroendocrine prostate cancer progression. BJU Int, 2018. 122(4): p. 560-570. [CrossRef]

- Conteduca, V. , et al., Circulating tumor cell heterogeneity in neuroendocrine prostate cancer by single cell copy number analysis. NPJ Precis Oncol, 2021. 5(1): p. 76. [CrossRef]

- Nouruzi, S. , et al., ASCL1 activates neuronal stem cell-like lineage programming through remodeling of the chromatin landscape in prostate cancer. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 2282. [CrossRef]

- Dardenne, E. , et al., N-Myc Induces an EZH2-Mediated Transcriptional Program Driving Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Cancer Cell, 2016. 30(4): p. 563-577. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K. , et al., N-Myc Drives Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Initiated from Human Prostate Epithelial Cells. Cancer Cell, 2016. 29(4): p. 536-547. [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, R. , et al., EMT, stemness and tumor plasticity in aggressive variant neuroendocrine prostate cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, 2018. 1870(2): p. 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Tong, D. , Unravelling the molecular mechanisms of prostate cancer evolution from genotype to phenotype. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2021. 163: p. 103370. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.M. , et al., Lineage plasticity in prostate cancer depends on JAK/STAT inflammatory signaling. Science, 2022. 377(6611): p. 1180-1191. [CrossRef]

- Bery, F. , et al., The Calcium-Sensing Receptor is A Marker and Potential Driver of Neuroendocrine Differentiation in Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2020. 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. , et al., ONECUT2 is a driver of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 278. [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, S. , et al., The Placental Gene PEG10 Promotes Progression of Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep, 2015. 12(6): p. 922-36. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.L. , et al., The Master Neural Transcription Factor BRN2 Is an Androgen Receptor-Suppressed Driver of Neuroendocrine Differentiation in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov, 2017. 7(1): p. 54-71. [CrossRef]

- Metz, E.P. , et al., Elevating SOX2 in prostate tumor cells upregulates expression of neuroendocrine genes, but does not reduce the inhibitory effects of enzalutamide. J Cell Physiol, 2020. 235(4): p. 3731-3740. [CrossRef]

- Ci, X. , et al., Heterochromatin Protein 1alpha Mediates Development and Aggressiveness of Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res, 2018. 78(10): p. 2691-2704. [CrossRef]

- Bluemn, E.G. , et al., Androgen Receptor Pathway-Independent Prostate Cancer Is Sustained through FGF Signaling. Cancer Cell, 2017. 32(4): p. 474-489 e6. [CrossRef]

- Lasorella, A. , et al., Id2 is a retinoblastoma protein target and mediates signalling by Myc oncoproteins. Nature. 407(6804): p. 592-8. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.M. , et al., Phosphorylation Regulates Id2 Degradation and Mediates the Proliferation of Neural Precursor Cells. Stem Cells, 2016. 34(5): p. 1321-31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. , et al., ID2 promotes survival of glioblastoma cells during metabolic stress by regulating mitochondrial function. Cell Death Dis, 2017. 8(2): p. e2615. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. , et al., Landscape of transcriptional deregulation in lung cancer. BMC Genomics, 2018. 19(1): p. 435. [CrossRef]

- van Bokhoven, A. , et al., Molecular characterization of human prostate carcinoma cell lines. Prostate, 2003. 57(3): p. 205-25. [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, T.C. , et al., Transcriptional profiling of matched patient biopsies clarifies molecular determinants of enzalutamide-induced lineage plasticity. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 5345. [CrossRef]

- Baca, S.C. , et al., Reprogramming of the FOXA1 cistrome in treatment-emergent neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 1979. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. , et al., ATF3 downmodulates its new targets IFI6 and IFI27 to suppress the growth and migration of tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells. PLoS Genet, 2021. 17(2): p. e1009283. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. , et al., HOXB13 suppresses de novo lipogenesis through HDAC3-mediated epigenetic reprogramming. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.H., H. Beltran, and A. Zoubeidi, Cellular plasticity and the neuroendocrine phenotype in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol, 2018. 15(5): p. 271-286. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , et al., Molecular events in neuroendocrine prostate cancer development. Nat Rev Urol, 2021. 18(10): p. 581-596. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. , et al., Neuroendocrine prostate cancer has distinctive, non-prostatic HOX code that is represented by the loss of HOXB13 expression. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 2778. [CrossRef]

- Miao, L. , et al., Disrupting Androgen Receptor Signaling Induces Snail-Mediated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res, 2017. 77(11): p. 3101-3112. [CrossRef]

- Abida, W. , et al., Genomic correlates of clinical outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019. 116(23): p. 11428-11436. [CrossRef]

- Alumkal, J.J. , et al., Transcriptional profiling identifies an androgen receptor activity-low, stemness program associated with enzalutamide resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2020. 117(22): p. 12315-12323. [CrossRef]

- Deng, S. , et al., Ectopic JAK-STAT activation enables the transition to a stem-like and multilineage state conferring AR-targeted therapy resistance. Nat Cancer, 2022. 3(9): p. 1071-1087. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.S. , et al., Novel RB1-Loss Transcriptomic Signature Is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcomes across Cancer Types. Clin Cancer Res, 2019. 25(14): p. 4290-4299. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H. , et al., BET Bromodomain Inhibition Blocks an AR-Repressed, E2F1-Activated Treatment-Emergent Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Lineage Plasticity Program. Clin Cancer Res, 2021. 27(17): p. 4923-4936. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).