1. Introduction

High-intensity ultra-short laser pulses become inseparable from the future development of industrial applications in 3D nano-/micro-machining/printing due to Moore’s law-like increase of their average power over the last years from 2000 [

1]. Deterministic energy deposition via highly nonlinear multi-photon and avalanche ionisation is key to 3D CNC machining metals and dielectrics from TW/cm

2 to PW/cm

2 intensity window [

2]. The laser ablation thresholds in the case of ultra-short 10 - 50 fs pulses attracted interest due to better control of laser machining depth and removed volume as observed in dielectrics [

3], however absent in metals [

4]. For example, in fused silica SiO

2, the ablation threshold was 1.3 J/cm

2, i.e., 1.5 times smaller than for longer fs-pulses, and the most efficient rate of ablated volume per pulse was at 4 J/cm

2 fluence or 0.57 PW/cm

2 intensity for 7 fs pulses [

3]. Formation of an over-critical (reflective) plasma mirror at the central part of the Gaussian intensity profile defined energy deposition efficiency and high precision ablation depth control with tens-of-nm per pulse. The ablated volume per energy saturates at the 30 fs pulse duration. Plasma mirror is proposed for compression of ultra-short laser pulses to reach the exawatt intensity scale [

5]; 1 EW =

W.

A 3D printing/polymerisation at ∼TW/cm

2 becomes ionisation controlled, and absorption defines polymerisation rather than the chemical composition of photo-initiators and two-photon absorbers. Deterministic energy deposition occurs at higher intensities corresponding to the tunnelling ionisation of molecules and atoms at

PW/cm

2 [

6]. In ambient air, focusing ultra-short pulses of a few tens of fs into spots of a few micrometres in diameter is possible by reflective optical elements, which deliver intensities sufficient for the tunnelling ionisation [

7]. Such conditions were explored in this study for THz radiation using instantaneous air breakdown along pulse propagation throughout the focus, which was sub-wavelength for emitted THz radiation.

THz spectral range

THz (3 mm - 10

m in wavelength) has fundamental importance for material science due to characteristic lattice vibrations of phonon modes. Among established semiconductor-based THz emitters/receivers working on photo-activated optically gated currents (Auston switch), a new emerging direction is using nano-thin topological insulators [

8]. Another emerging direction is the use of dielectric breakdown as a tool to create short-lived (

ps) and micro-localized (sub-wavelength at THz frequencies) currents for THz emission [

9]. Coherent directional emitters at far-IR wavelengths can be realised using Wolf’s effect, where surface sub-wavelength structures of period

m for far-IR black body radiation

are defined to extract emission of the surface phonon polariton (SPP) mode

at an angle

from the normal to the crystal surface according to the phase matching condition for wavevectors

along the surface:

[

10]. In this way, acoustic/optical photon THz frequencies are extracted into free-space radiation, which is, additionally, coherent due to the sub-wavelength character of the grating.

The single-cycle high-intensity of electrical THz field of 1 MV/cm was demonstrated with fs tilted-front pulses using optical rectification in LiNbO

3 crystal [

11]. Periodically polled lithium niobate was used to produce THz emission via walk-off of optical pump and THz wave [

12]. High THz pulse energy of 10

J at a peak field strength of 0.25 MV/cm, was produced by optical rectification when phonon-polariton phase velocity was matched with the group velocity of driving fs-laser pulse and reached high visible-to-THz photon conversion of 45% [

13]. Tunable 10-70 THz emitters were realised via difference-frequency mixing of two parametrically amplified pulse trains from a single white-light seed in GaSe or AgGaS

2 crystals and reached 100 MV/cm peak field at

W peak power (19

J energy) using table-top laser system [

14]. Such high powers are usually produced by free electron lasers (FELs). The THz radiation is related to fast electrical current as per the Fourier transform, i.e., 1 ps current generates 1 THz radiation. Spin-Hall currents in tri-layers of 5.8-nm-thick W/Co

40Fe

40B

20/Pt were used as THz broadband 1-30 THz emitters generating field strength of several 0.1 MV/cm and outperformed ZnTe

emitters [

15]. An electrical conductivity induced via the Zenner tunneling can be harnessed to induce electrical transients in semiconductors and dielectrics by strong optical fields. When an optical field of 170 MV/cm was applied to the Auston switch with a 50 nm gap on SiO

2 by sub-4 fs pulse of 1.7 eV light, the currents were detected due to induced electron conductivity of 5

m

−1, which is 18 orders of magnitude higher than the static d.c. conductivity of amorphous silica [

16]. Optical control of phonon modes and Zenner tunneling can be operated without the dielectric breakdown maintaining solid-state material. High-intensity ultra-short irradiation of gasses, liquids, and solids at higher intensities, when the dielectric breakdown occurs, can also be used for producing high-intensity THz fields [

17]. By co-propagation of the first and second harmonics beams focused with

mm lens into long filaments in air plasma, the AC-bias conditions, THz emitters were realised delivering peak intensities up to 10 kV/cm [

18,

19,

20]. Polarisation of the emitted THz radiation can be set circular by introducing non-colinearity between the filaments [

21]. Irradiation of He-jet in vacuum was shown to produce coherent THz emission via the transition radiation of ultra-short electron bunches produced by the laser wakefield, which, in turn, was produced by 8 TW peak power pulses of 800 nm/50 fs [

22]. The short length of the electron bunch was responsible for the coherent emission. The field of THz sources has become an active research frontier [

23,

24,

25].

Here, we used a focused fs-laser pulse for air breakdown from sub-wavelength volumes, which can potentially lead to the engineering of high-intensity THz emitters due to the coherent addition of THz electrical fields and ultra-short duration of a few optical periods. Two pre-pulses used in this study revealed a position dependence on the THz emission and its polarisation, extending from the previous study where one pre-pulse was used [

26]. Experimental conditions of focusing and THz detection were kept the same [

26], and only two pre-pulses were introduced using a holographic beam shaping technique based on a spatial light modulator (LC- SLM) [

27]. For consistency, the same pulse energies were used for pre- and main-pulses: 0.2 and 0.4 mJ (13 GW/pulse), respectively [

26]. The range of THz emission was

THz [

26]. The experimental results were interpreted with a theoretical model accounting for the air ionisation and free electron heating, generation and propagation of a shockwave, and spontaneous generation of the magnetic field due to coupled thermal and density gradients at the shock front. Interestingly, two- or three-pulse irradiation with air breakdown and shock formation is approaching the frequencies

THz of 5G network

GHz (Technical Specification Group Radio Access Network TS 38.104).

2. Experimental results

Two-pulse experiment with pre- and main pulses [

26] revealed the required timing and spatial separation for the shocked-compressed air by the pre-pulse to be pushed into the position of the main pulse at

for the maximum emission of THz radiation. Pre-pulse had to arrive 9.7 ns earlier to the focus of the main pulse from the position

m away for the maximum THz emission. Polarisation of THz radiation was found aligned along the direction of focal positions of pre-pulse and main pulse [

26]. Here, we add a second pre-pulse of the same 0.2 mJ energy with the possibility of placing it freely in 3D space

.

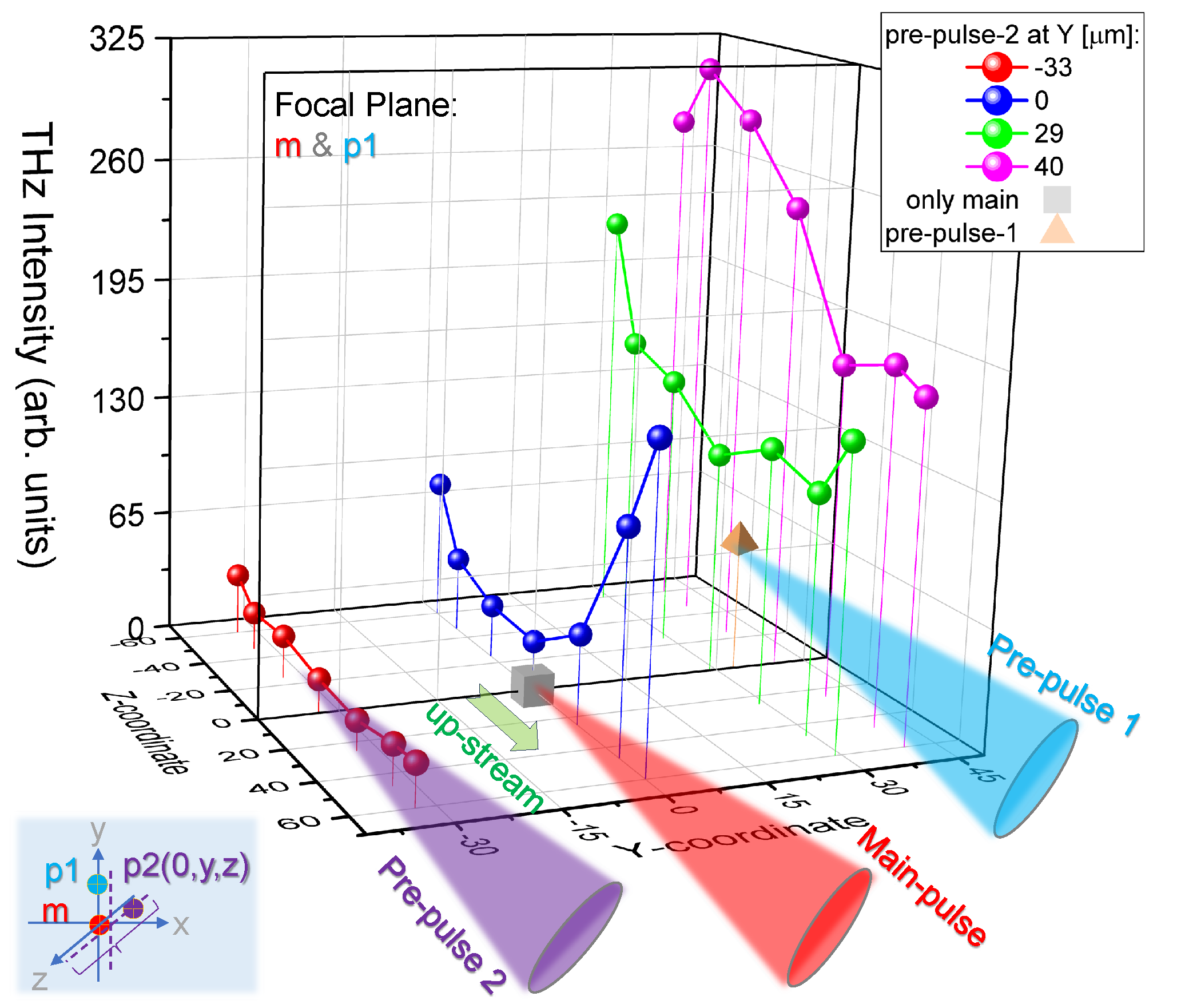

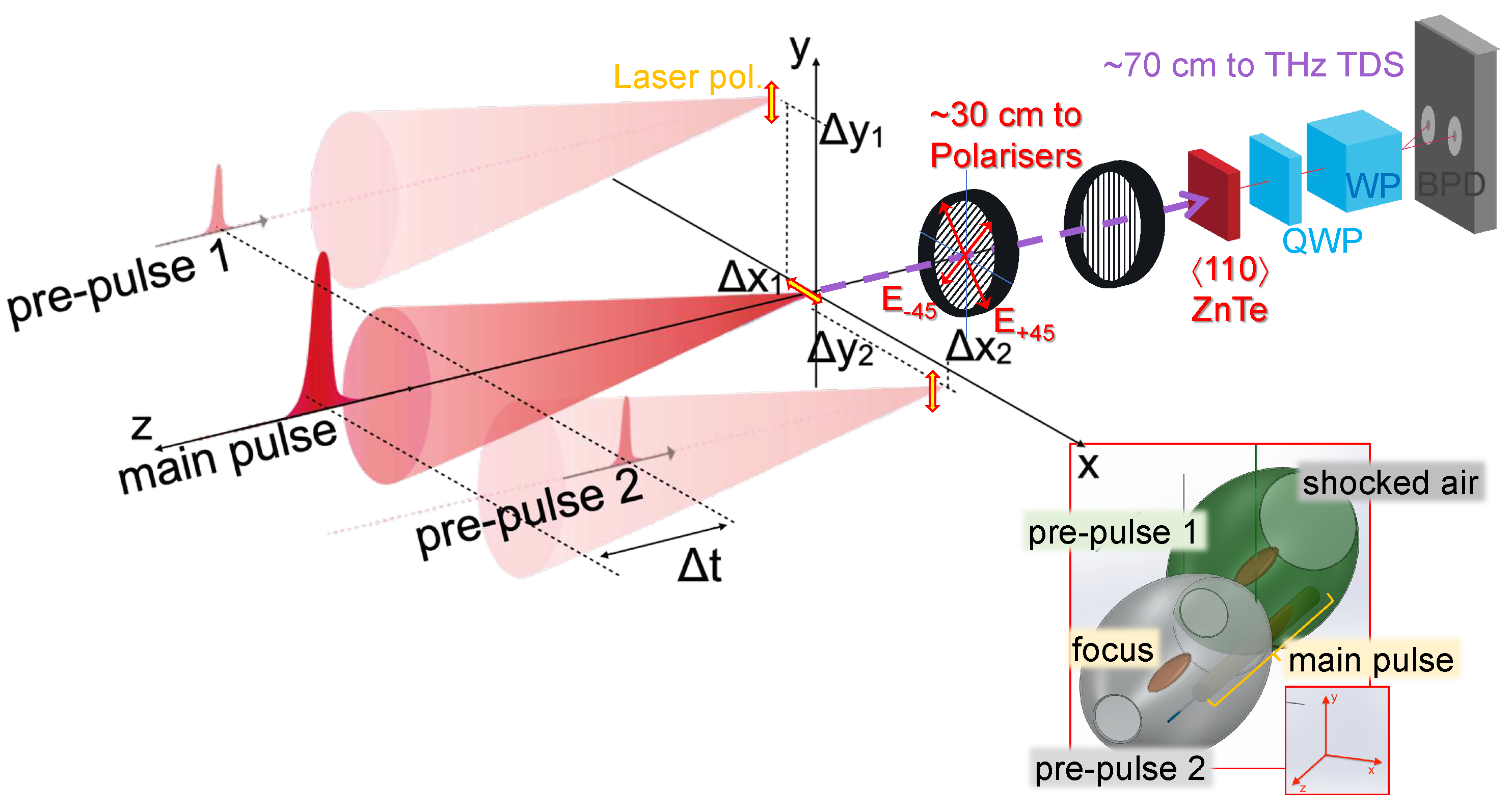

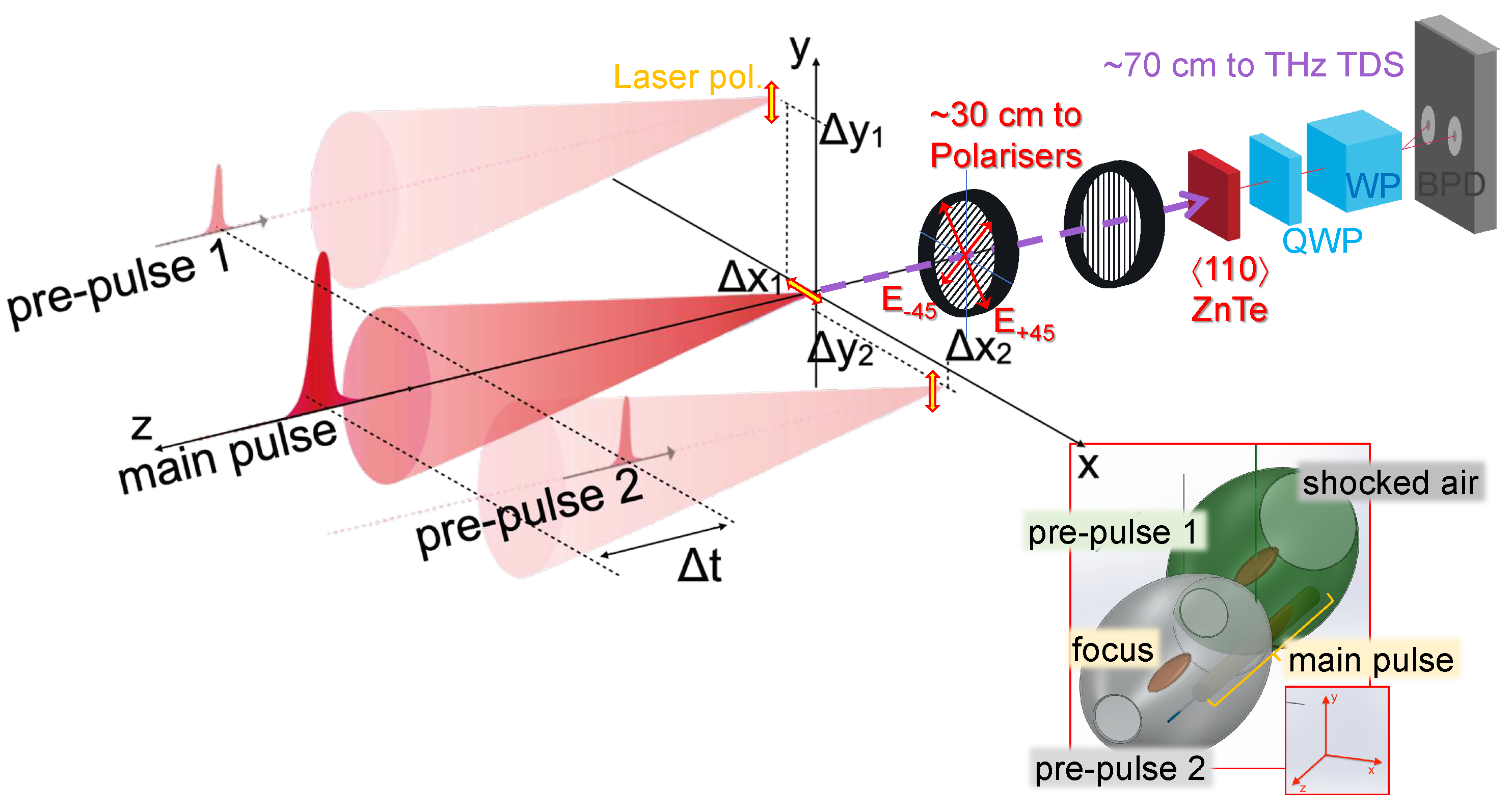

Figure 1 shows the scheme of the experiment and the diagnostics. Details of the experimental setup and the measurement methodology are described in

6. The effect of placement of the second pre-pulse on polarisation and intensity of THz radiation was systematically studied. Due to short 35 fs pulse (

m in length) and

z-position (along the beam propagation) change only tens-of-micrometers. Hence, the timing of both pre-pulses can be considered simultaneous, regardless of the actual

z-coordinate of the pre-pulse 2 within an error of

nm, which is by an order of magnitude smaller than the shockwave thickness.

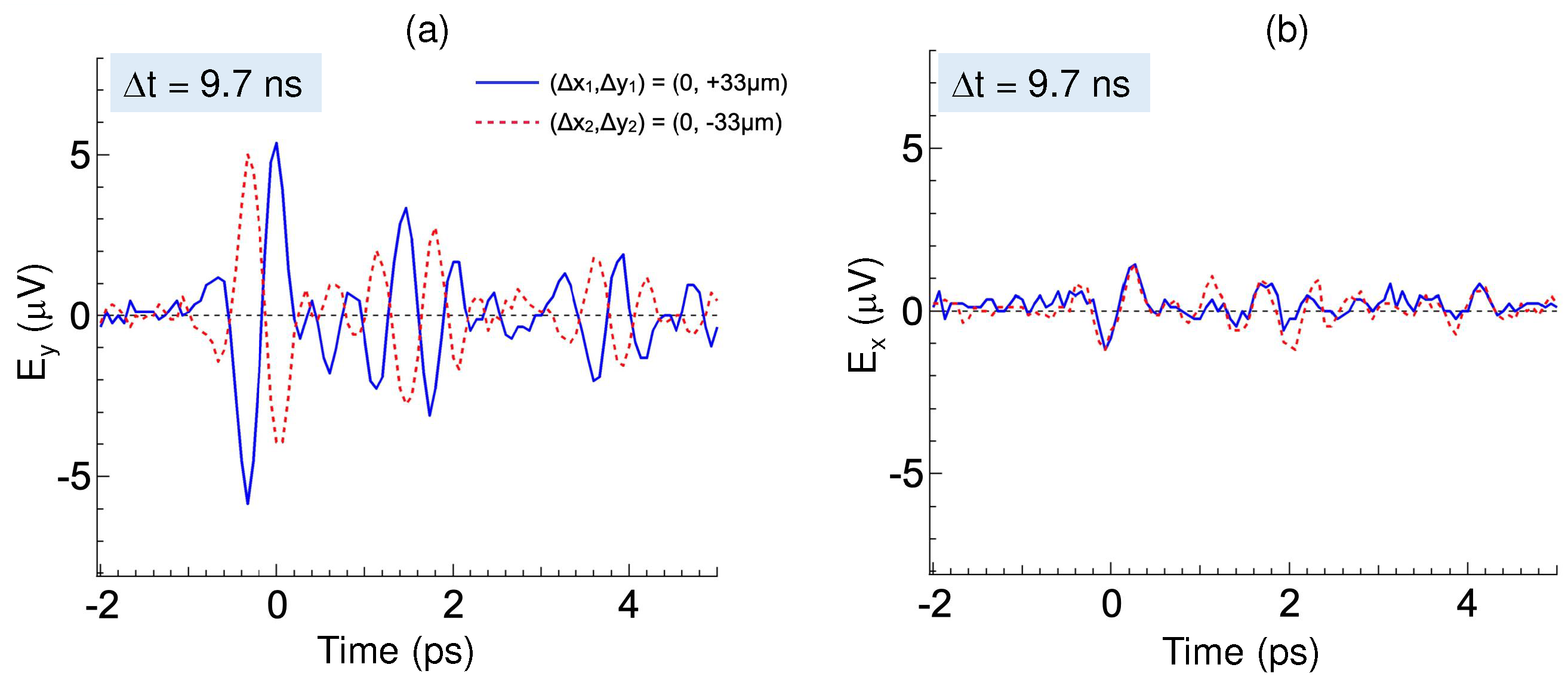

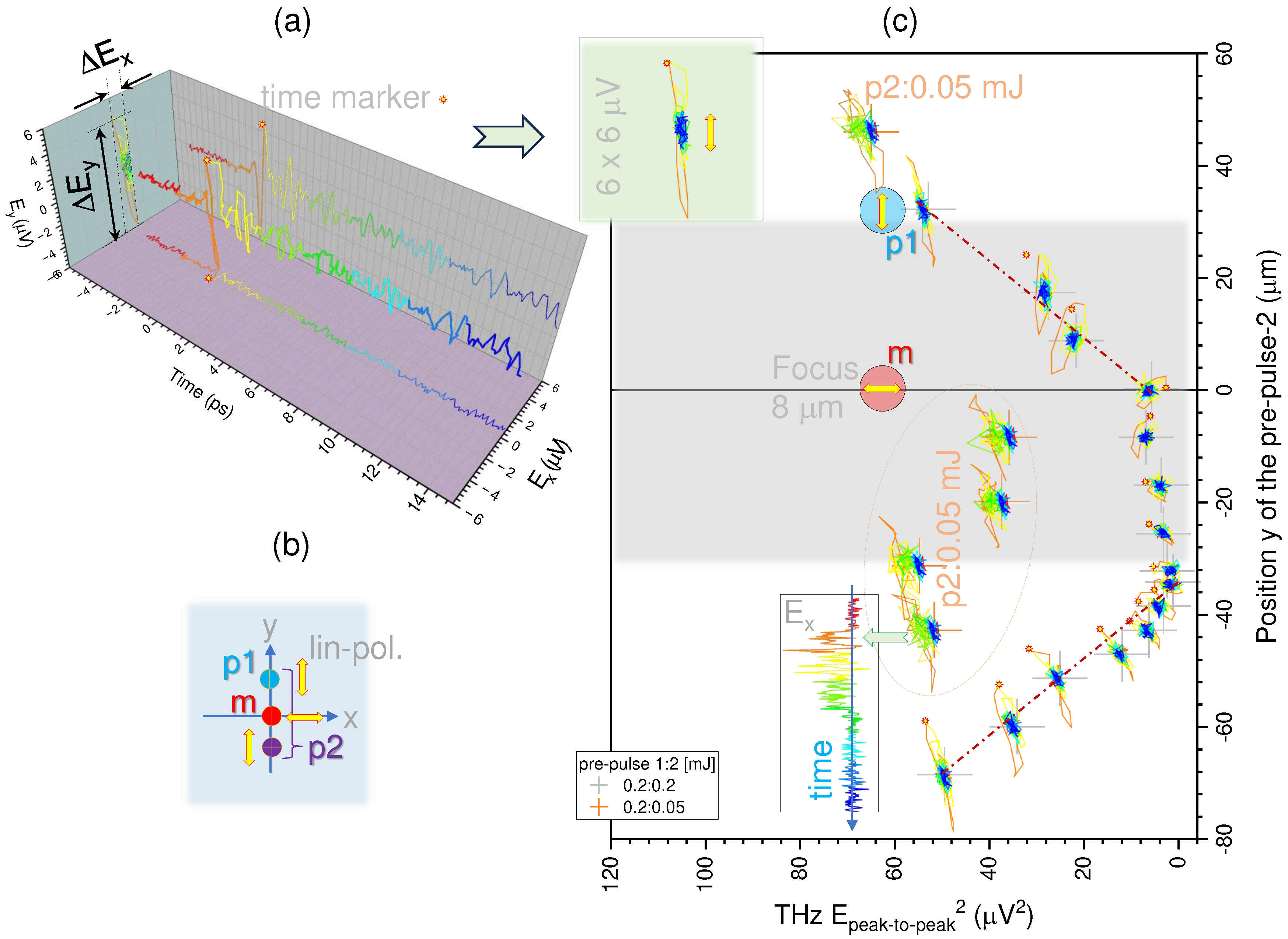

2.1. Y-position of pre-pulse 2

Figure 2 shows the emission of THz radiation (

component) for the situation when the pre-pulse 1 is focused at

m. At the same time, the second pre-pulse is focused at other

position with respect to the main-pulse focus at

; see

Figure 1. Change of

field orientation was observed over the measured range of THz frequencies as shown by the time domain transients in

Figure 2(a). When two pre-pulses were simultaneously irradiated at opposite (with respect to

) positions, the cancellation of THz

components occurred. This confirms that the air density gradient induced by the shock front is more important than the air mass density, which is increased by two colliding shocks.

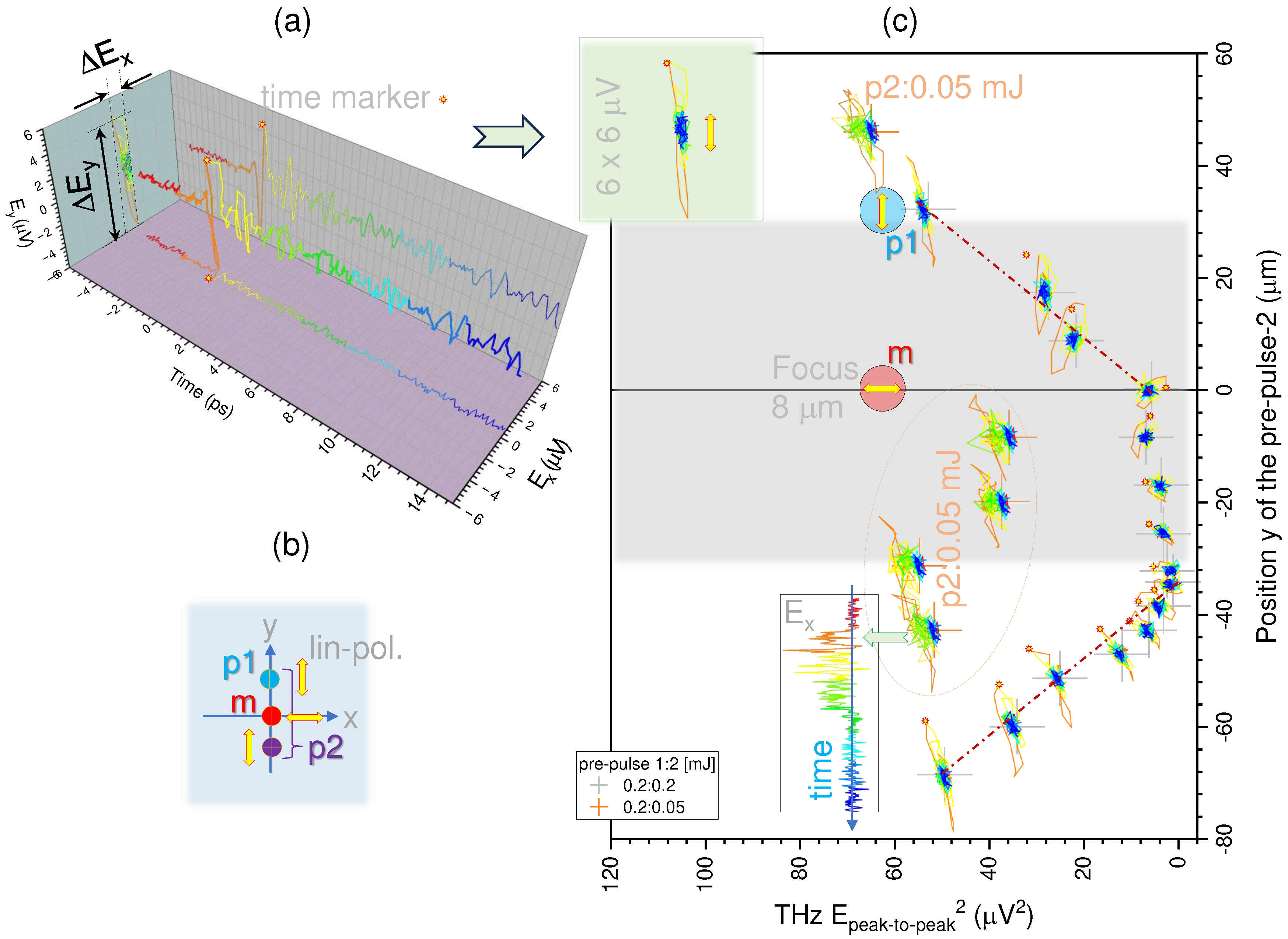

For two pre-pulse experiments, a dependence of THz emission on the offset

of the second pre-pulse was determined. The delay of the first pre-pulse of 9.7 ns was optimised, so the THz emission was the most intense. The THz intensity is calculated from the

components as peak-to-peak value (see inset in

Figure 3). A pictorial diagram for each irradiation point is presented by the projection of THz E-field on

-plane. The projection shows the overall temporal evolution of THz electric field orientation during emission time.

One pre-pulse produced enhancement of THz emission by 13 times, i.e., the value V2 compared to the value V2 without a pre-pulse. The component of the THz field becomes larger for offsets m compared to the enhancement produced by the first Conversely, when pre-pulse 2 was closer to the position where the main pulse is focused, the amplitude of THz field was reduced.

The second pre-pulse of four times smaller energy of 0.05 mJ, had no significant effect on the THz emission, regardless of the position at

, opposite side from pre-pulse 1 with respect to the main pulse focus. A different evolution in time for such 0.05 mJ second pre-pulse was observed. It showed a

ps duration of larger negative values of

component (see inset in

Figure 3(c) and colour asymmetric

markers). This is probably due to a later arrival and shorter contribution of a shock wave triggered by a four times lower pre-pulse energy. Indeed, the radius

R of a cylindrical shock wave created by the laser energy deposition on the axis

increases with time

t as

according to the Sedov–von Neumann–Taylor model [

28]. The major contribution to the THz enhancement was governed by the first pre-pulse with an energy of 0.2 mJ.

Interestingly, when pre-pulse 2 was on the same side as pre-pulse 1 at a distance from the main pulse position larger than 33

m (pre-pulse-1), the

enhancement was

times (see Sec.

Sec. 3 for discussion). In this case, the shock-affected volume from the pre-pulse 1 was crossed by the pre-pulse 2. When a shock wave propagates through a region of rarefied density

formed by the other pre-pulse, the same cylindrical explosion model predicts scaling

. When pre-pulse 2 arrived at

to

m (the opposite side of the

y-axis as compared to pre-pulse 1), it quenched the effect of THz enhancement. However, at even more negative positions of pre-pulse 2, the same enhancement was observed for arriving shocks to the position of the main pulse; see red-dashed lines drawn as eye guides in

Figure 3(c).

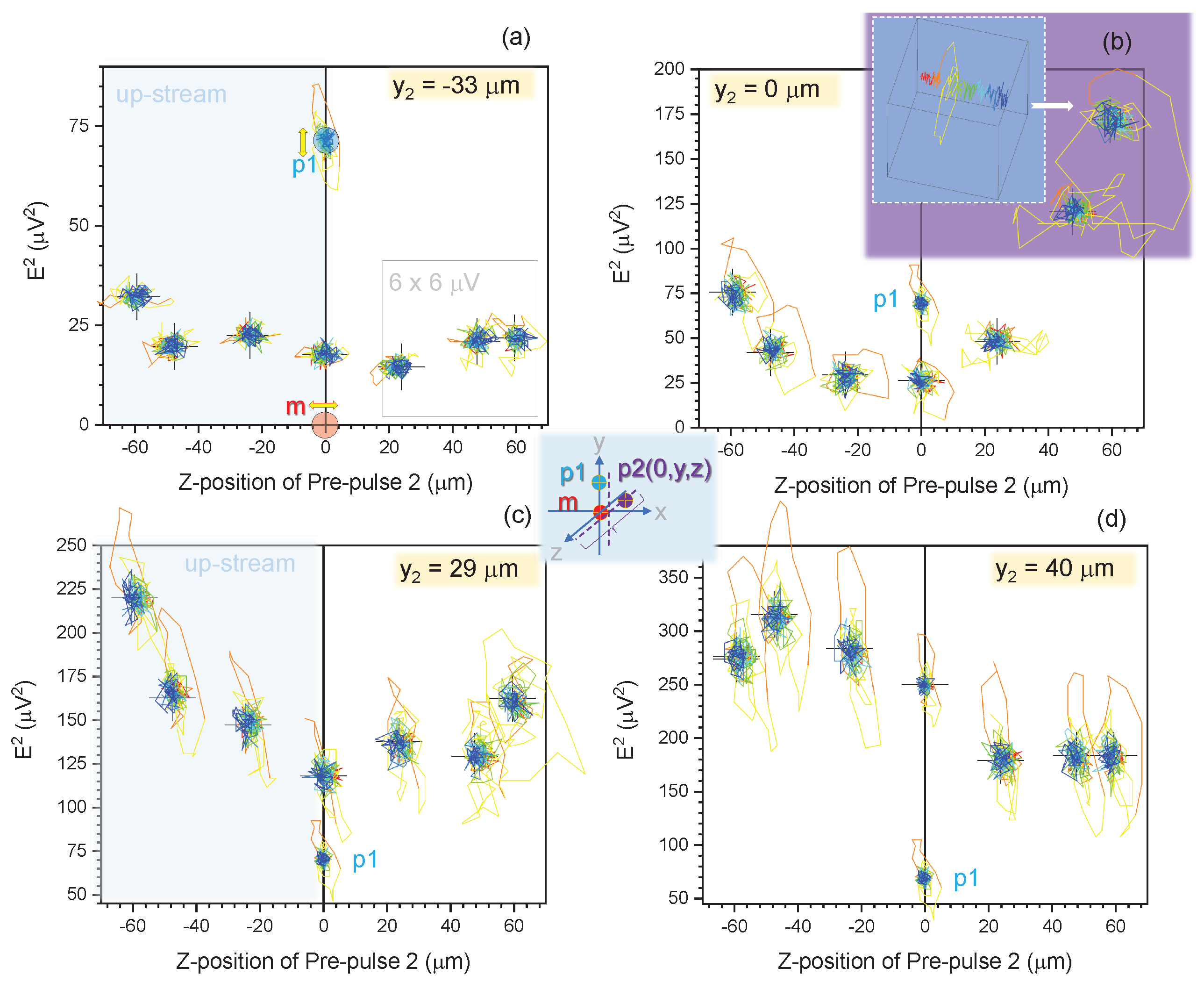

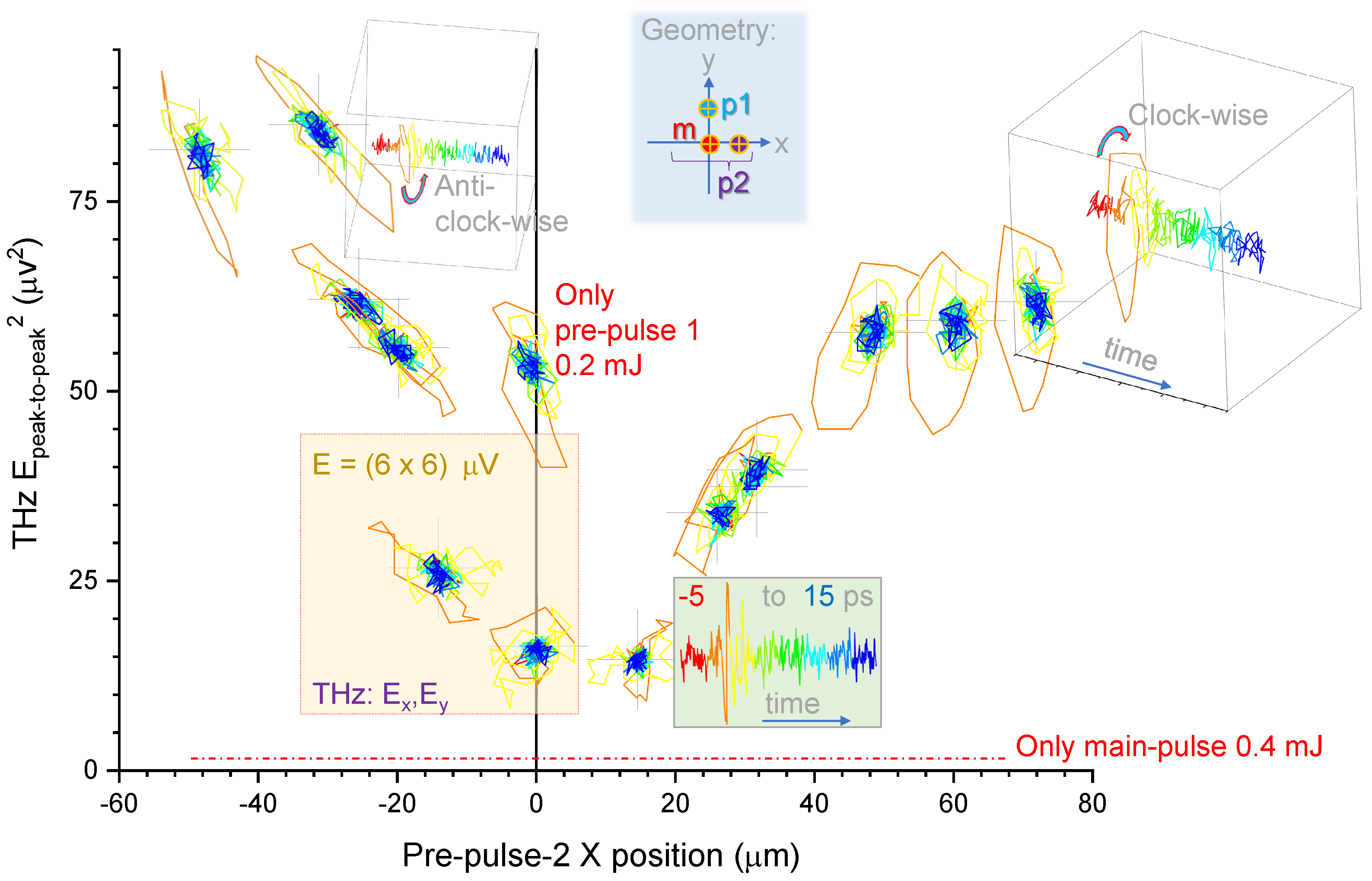

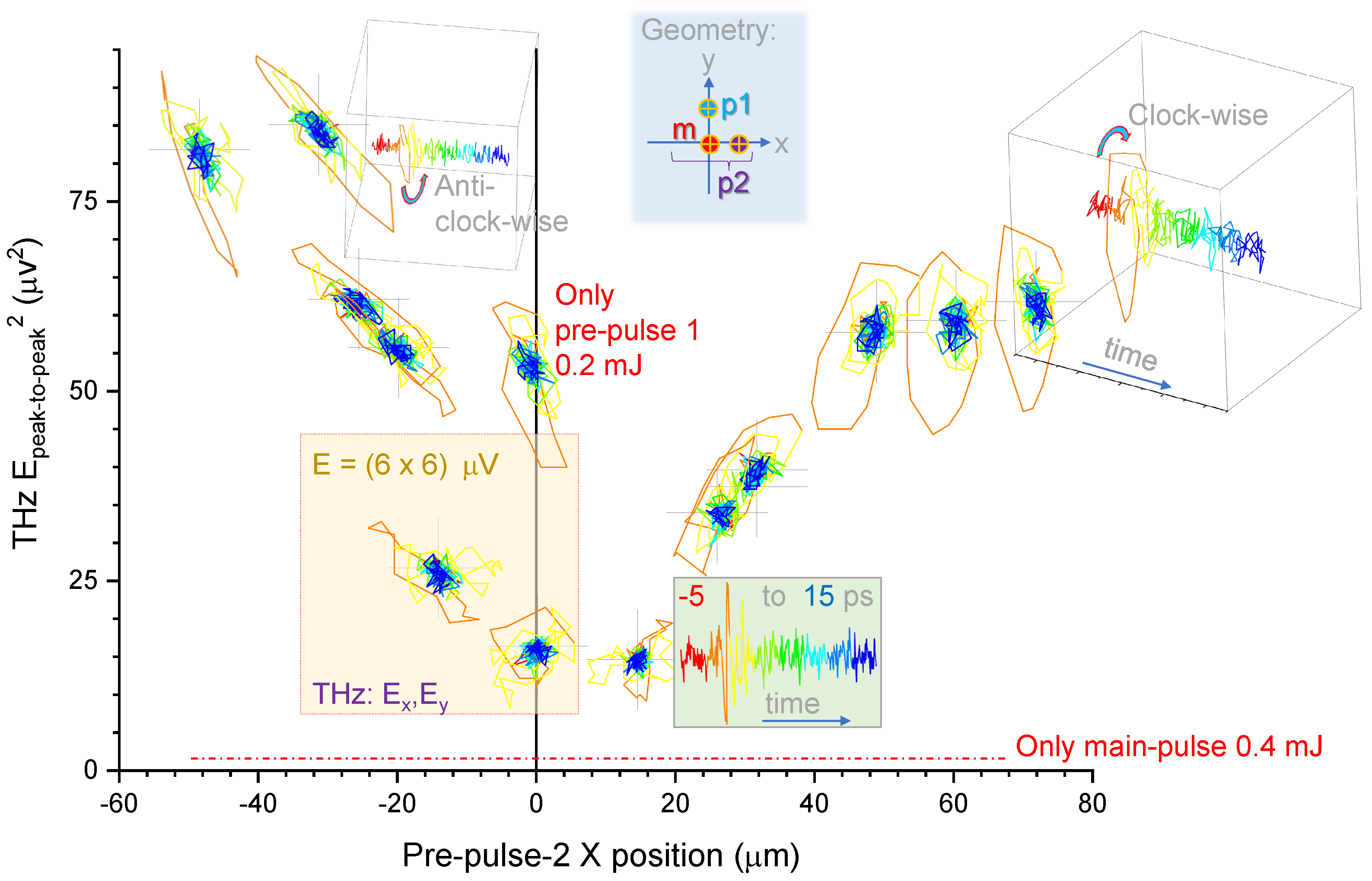

2.2. X-position of pre-pulse 2

Next, the dependence of THz emission of the

x-position of the second pre-pulse was determined, see

Figure 4. The

trajectories indicate the radial influence of the pre-pulse irradiation position with respect to the main pulse (the pre-pulse 1 was always at the

m). The ellipticity of THz polarisation was larger for the pre-pulse 2 locations (larger

). This is explained by the optimal timing of 9.7 ns for the pre-pulse position at

m from the main pulse position. This is valid along any direction perpendicular to beam propagation in the

plane. When

m, the shock arriving along the

x-axis does not fit the perfect timing for THz enhancement and alters the effect of the pre-pulse 1 arriving along a perpendicular direction. When

m, pre-pulse 2 makes a small contribution to the enhancement determined by pre-pulse 1. The pre-pulses 1 and 2 arriving at perpendicular directions define the ellipticity of the THz radiation and its handedness (see

Figure 4). The duration of the most intense THz radiation lasts approximately one cycle, corresponding to

rotation in the

plane (see a side-view cross-section along the time axis in the inset of

Figure 4).

The dependence of THz emission on the position of the pre-pulse along the

Z axis is presented in

B.

4. Discussion

The theoretical estimates for the frequency cut-off and the emitted energy are compatible with the observations. The analytical expressions for these parameters show the way of further improvements. The conversion efficiency of the magnetic field into radiation can be increased either by increasing the ratio

with a tighter laser beam focusing or by creating a non-zero average magnetic field in the plasma. This will increase the conversion efficiency by a factor of

. The structure of the magnetic field given by Eq. (

A6) corresponds to the circular laser beam interacting with a planar shock. To produce a non-zero average magnetic field one may consider an elliptic laser beam with the ellipse axis at an angle (not equal to 0 or 90°) with respect to the

x axis.

Another possibility of increasing emission consists of increasing the magnetic field energy. According to the analysis of Eq. (

8), the generated magnetic field depends effectively on two plasma parameters: electron temperature

and shock front width

. The magnetic field energy depends on electron temperature with the fifth power. So, even a modest increase in electron temperature by a factor of 1.5 will increase the emission energy by 10 times. This can be achieved by increasing the energy of the main laser pulse.

In conclusion, the theoretical analysis of THz emission in air with two laser pulses confirms the hypothesis proposed by Huang et al. [

39] that the emission is produced from a plasma created by the main pulse in the shock front. The theoretical estimates of the plasma and shock parameters are in agreement with the measurements. However, the mechanism of electromagnetic emission is different from the diffusion current in semiconductors [

36]. An electrostatic current related to the charge separation cannot be excited in plasma. Instead, a rotation current is created by non-parallel gradients of electron density and temperature. This current induces a magnetic field and produces a magneto-quadrupole electromagnetic emission. The emission wavelength is controlled by the length of the laser focal region and can be varied by changing the numerical aperture.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

By using two pre-pulses with the same timing at focal spots placed at different 3D locations with respect to the focus of the main pulse, it is possible to engineer air density gradients arriving at the main irradiation site. An addition of two perpendicular air density gradients and allows one to control the ellipticity and intensity of the emitted THz radiation. A single cycle circular polarisation THz radiation can be produced. By placing m-diameter focal spots in 3D space with separations of in space and ns in time, it is possible to synchronise the arrival of shock wave fronts travelling at high Mach m/ns speeds in the air for THz emission enhancement and polarisation control at the laser pulse intensities of a fully deterministic tunnelling ionisation W/cm2.

The origin of THz emission is the current induced at the crossed plasma density and temperature gradients, called the Biermann battery effect [

38]. This study clarified that the electrostatic current related to the charge separation cannot be excited in plasma. A coalescence of two shocks at the position of the main pulse produces stronger air compression than a single pulse, thus generating a stronger THz emission at a shorter wavelength. Since the electron current is proportional to the electron temperature and inversely proportional to the shock thickness, the way to increase the power of THz emission would be the increase of electron temperature and the strength of the shock.

After the collision of two shocks created by two pre-pulses, the interaction of the main laser pulse with the compressed air creates a plasma with asymmetric density distribution, which affects the intensity and polarisation of the THz emission in a two-fold way. First, the three-dimensional density asymmetry produces the anisotropy of pressure force and permits the current circulation on a picosecond time scale. Second, the shock density gradient is defined by the angle of collision of two shocks created by two pre-pulses. It is not necessarily aligned along the line connecting the pre-pulse and the main pulse, which affects the polarisation of the THz signal. The privileged direction of THz emission is in the plane perpendicular to the laser pulse propagation. This is the theoretical prediction that is verified in the experiment.

An example of a high-density micro-target for the generation of an extreme UV emission at 13.5 nm for the next generation of photolithography is realised by irradiation of 20-

m diameter Sn micro-spheres by a focused 10

m wavelength CO

2 laser [

40]. Similarly, micro-jets of Ga produced by laser pulse showed a strong enhancement of X-ray generation [

41]. In water, micro-droplets and micro-sized gradients of compressed air serve the same purpose of delivering more material into laser pulse/beam, which results in plasma with higher density and temperature [

42,

43].

6. Materials and Methods

All the experiments were conducted in air under atmospheric pressure (1 bar) at room temperature (RT; 296 K). The experimental setup is described in detail elsewhere [

29]. A pulsed femtosecond laser (35 fs, transform-limited,

nm, 1 kHz, Mantis, Legend Elite HE USP, Coherent, Inc.) was used and the output pulses were split into the pre-pulse 1 (linearly-polarized parallel to the

y-axis,

y-pol., 0.2 mJ), pre-pulse 2 (linearly-polarised parallel to the

y-axis,

y-pol., 0.2 mJ) and the main pulse (linearly-polarized parallel to the

x-axis,

x-pol., 0.4 mJ). THz emission is induced by tightly focussing the main pulse with an off-axis parabolic mirror (1-inch diameter, focal length

mm, 47-098, Edmund Optics) into air with a time-delay,

ns, between the main pulse and the pre-pulse arrivals. Under the main pulse focusing condition with effective numerical aperture

, the laser focus area was estimated to be about

m in diameter and

m in length along the axial direction (depth-of-focus) [

29].

Spatial offsets of the two pre-pulses along the

x- and

y-axes,

and

, were made possible with a Liquid Crystal on Silicon-Spatial Light Modulator (LCOS-SLM, X15213, Hamamatsu Photonics). The homemade program used computer-generated holograms (CGHs) that form multiple focal points and display them on the LCOS-SLM. CGHs were optimized by the weighted Gerchberg-Saxton (WGS) algorithm [

44] for the uniform intensity of the focal points. The pre-pulse 1 was set stationary at (

,

,

) = (

m,

m,

m) while the pre-pulse 2 was scanned in three dimensions along the

x-,

y-, or

z-axis using 3D holographic focusing [

45].

The detection of the THz wave emission is achieved by the standard electro-optic sampling method (see

A), THz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS), in the transmission direction along the

z-axis with a

-oriented ZnTe crystal (1-mm thick, Nippon Mining & Metals Co., Ltd.) [

9,

29,

46]. The measurements of the THz polarisation were carried out with a set of wire grids before the detection

-oriented ZnTe crystal following the standard procedure [

47,

48,

49]. Both polarisations of the THz emission

were determined from the event of laser irradiation by the main pulse via calculation of the measured fields

using

orientated wire-grid polarisers in respect to the

x-polariser (high transmission) placed just before the

polariser. The effective repetition of the laser excitation is at 0.5 kHz to restore the same air conditions for subsequent laser shots. Two laser pulses (main) were required to determine

and

components separately. Transient of THz emission was established from separate laser shots for the -5 to 15 ps

-projections.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup with temporal (

= 9.7 ns) and spatial offsets of the the pre-pulse 1 (

,

,

), and the pre-pulse 2 (

,

,

) irradiation positions. THz electric field amplitudes

were calculated from

and

measurements, where

is the angle of the polariser wire-grids:

and

(see

A for details). The pre-pulse position was also tuned to place focus at the up-stream (positive

) and down-stream

locations; see bottom-right inset. The standard polarised THz-TDS detection system was based on a pair of wire-grid polarisers in front of ZnTe crystal (co-illuminated with THz pulse, which is not shown for clarity of figure), a quarter-wave plate (QWP), a Wollaston prism (WP) and a balanced photo-detector (BPD). The lower-inset shows 3D positions of the focal region of both pre-pulses with shockwave fronts (geometry is based on optical shadowgraphy imaging).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup with temporal (

= 9.7 ns) and spatial offsets of the the pre-pulse 1 (

,

,

), and the pre-pulse 2 (

,

,

) irradiation positions. THz electric field amplitudes

were calculated from

and

measurements, where

is the angle of the polariser wire-grids:

and

(see

A for details). The pre-pulse position was also tuned to place focus at the up-stream (positive

) and down-stream

locations; see bottom-right inset. The standard polarised THz-TDS detection system was based on a pair of wire-grid polarisers in front of ZnTe crystal (co-illuminated with THz pulse, which is not shown for clarity of figure), a quarter-wave plate (QWP), a Wollaston prism (WP) and a balanced photo-detector (BPD). The lower-inset shows 3D positions of the focal region of both pre-pulses with shockwave fronts (geometry is based on optical shadowgraphy imaging).

Figure 2.

The THz-TDS waveforms of (a) y-component of the single pre-pulse when the delay time between the pre-pulse and main pulse irradiation is at 9.7 ns. The spatial offset for the pre-pulse irradiation is (, ) = (m, m) for the blue solid line or (m, m) for the red dotted line. (b) The y-component of the dual pre-pulses when (, , ) = (m, m, m) and (, , ) = (m, m, m).

Figure 2.

The THz-TDS waveforms of (a) y-component of the single pre-pulse when the delay time between the pre-pulse and main pulse irradiation is at 9.7 ns. The spatial offset for the pre-pulse irradiation is (, ) = (m, m) for the blue solid line or (m, m) for the red dotted line. (b) The y-component of the dual pre-pulses when (, , ) = (m, m, m) and (, , ) = (m, m, m).

Figure 3.

(a) THz polarization evolution in time shown as a map. (b) Geometry of main pulse (m) and pre-pulses 1,2 (p1,p2). Pre-pulse 1 and the main pulse were fixed, and pre-pulse 2 was scanned along the y-axis. (c) The THz-polarisation intensity as a function of the vertical offset for the second pre-pulse, . is as shown in the inset and is equal to + . The delay time between the pre-pulse and main pulse irradiation is 9.7 ns. The spatial offset for the first pre-pulse irradiation is fixed at (, ) = (m, m) while the position of the second pre-pulse irradiation, and was varied from 0 to m. The blue THz-pol. plot indicates the results from two pre-pulse irradiation with both pre-pulses at 0.2 mJ. The black THz-pol. plot indicates the results from two pre-pulse irradiation with the pre-pulses at 0.2 mJ and the second pre-pulse at 0.05 mJ. The red THz-pol. plot indicates single pre-pulse irradiation condition with the pre-pulse at 0.2 mJ and (, ) = (m, m). The main pulse energy is 0.4 mJ. The red dotted line indicates the THz emission from a single main pulse irradiation in air.

Figure 3.

(a) THz polarization evolution in time shown as a map. (b) Geometry of main pulse (m) and pre-pulses 1,2 (p1,p2). Pre-pulse 1 and the main pulse were fixed, and pre-pulse 2 was scanned along the y-axis. (c) The THz-polarisation intensity as a function of the vertical offset for the second pre-pulse, . is as shown in the inset and is equal to + . The delay time between the pre-pulse and main pulse irradiation is 9.7 ns. The spatial offset for the first pre-pulse irradiation is fixed at (, ) = (m, m) while the position of the second pre-pulse irradiation, and was varied from 0 to m. The blue THz-pol. plot indicates the results from two pre-pulse irradiation with both pre-pulses at 0.2 mJ. The black THz-pol. plot indicates the results from two pre-pulse irradiation with the pre-pulses at 0.2 mJ and the second pre-pulse at 0.05 mJ. The red THz-pol. plot indicates single pre-pulse irradiation condition with the pre-pulse at 0.2 mJ and (, ) = (m, m). The main pulse energy is 0.4 mJ. The red dotted line indicates the THz emission from a single main pulse irradiation in air.

Figure 4.

The THz-polarisation [V2] intensity as a function of the horizontal offset for the second pre-pulse, . The delay time between the pre-pulse and the main pulse is 9.7 ns. The spatial offset for the first pre-pulse irradiation is (, ) = (m, m), while the second pre-pulse is focused at different position with = m (see top-right inset for geometry schematics). The RGB projections () of THz plots are from two pre-pulse irradiation with both pre-pulses at 0.2 mJ. The red THz-pol. plot indicates single pre-pulse irradiation condition with the pre-pulse at 0.2 mJ and (, ) = (m, m). The main pulse energy is 0.4 mJ. The red dotted line indicates the THz emission from single main pulse irradiation in air at V2. The boxed-area (yellow) is V for the -projection maps located at the cross-markers, at which the total intensity is plotted after power calibration. The 3D projection insets illustrate RGB time evolution over a span -5 ps to 15 ps and reveal the sense of polarisation rotation (looking into the beam or time axis); it is plotted for the closest projection RGB markers, respectively.

Figure 4.

The THz-polarisation [V2] intensity as a function of the horizontal offset for the second pre-pulse, . The delay time between the pre-pulse and the main pulse is 9.7 ns. The spatial offset for the first pre-pulse irradiation is (, ) = (m, m), while the second pre-pulse is focused at different position with = m (see top-right inset for geometry schematics). The RGB projections () of THz plots are from two pre-pulse irradiation with both pre-pulses at 0.2 mJ. The red THz-pol. plot indicates single pre-pulse irradiation condition with the pre-pulse at 0.2 mJ and (, ) = (m, m). The main pulse energy is 0.4 mJ. The red dotted line indicates the THz emission from single main pulse irradiation in air at V2. The boxed-area (yellow) is V for the -projection maps located at the cross-markers, at which the total intensity is plotted after power calibration. The 3D projection insets illustrate RGB time evolution over a span -5 ps to 15 ps and reveal the sense of polarisation rotation (looking into the beam or time axis); it is plotted for the closest projection RGB markers, respectively.

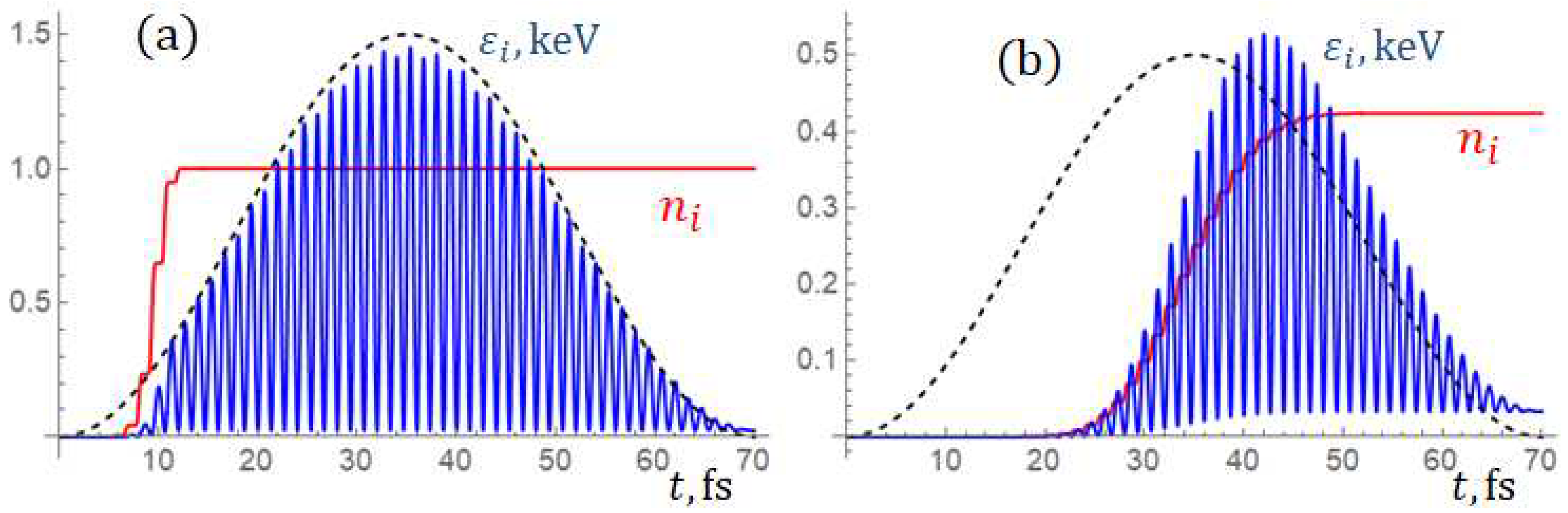

Figure 5.

Ionisation probability (red) and the electron kinetic energy for the parameters of the main pulse interacting with the nitrogen ion and liberation an electron from the level (left) and 5 (right). Pulse duration is 35 fs at FWHM.

Figure 5.

Ionisation probability (red) and the electron kinetic energy for the parameters of the main pulse interacting with the nitrogen ion and liberation an electron from the level (left) and 5 (right). Pulse duration is 35 fs at FWHM.

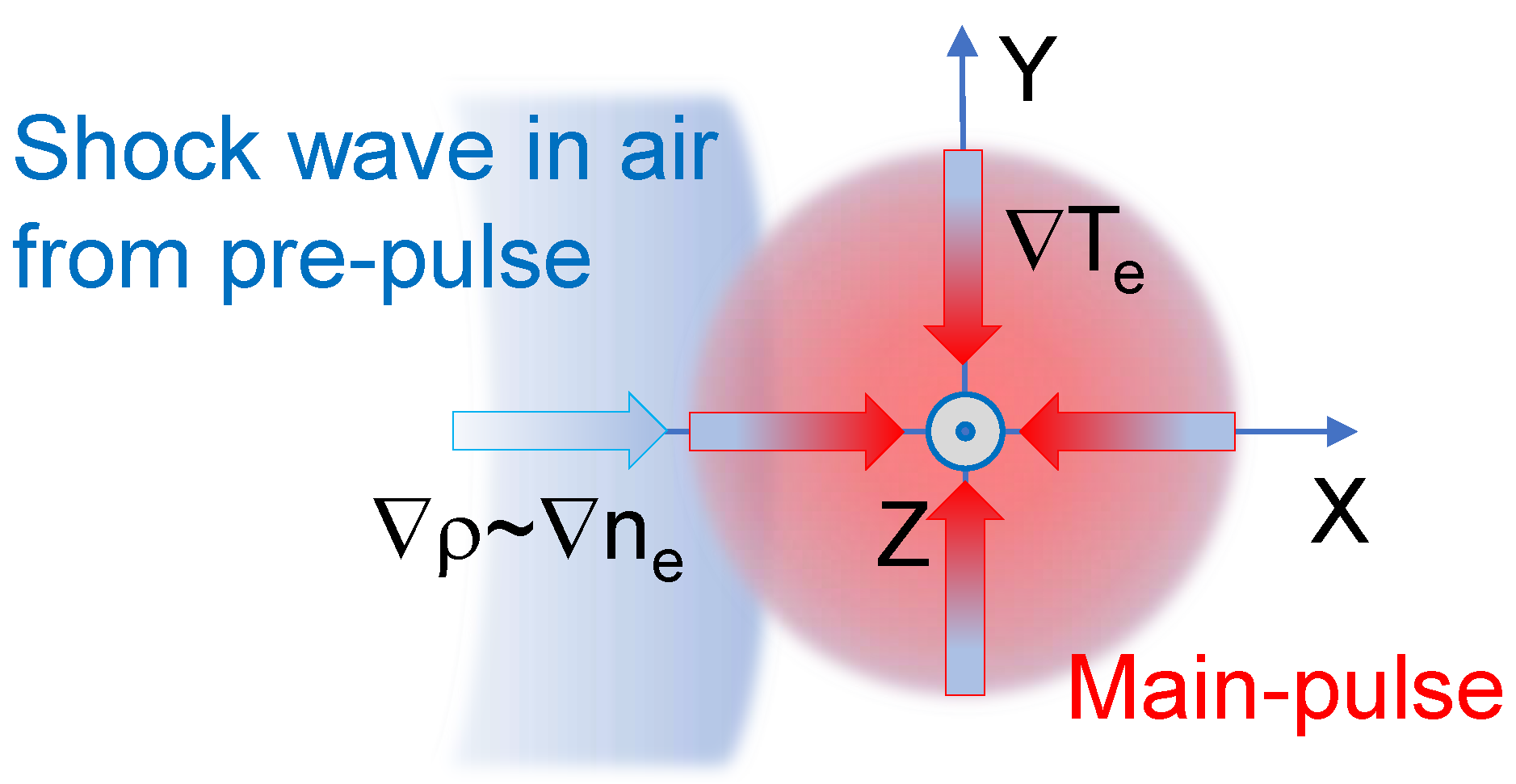

Figure 6.

Two-pulse enhancement of THz generation in air by the spontaneous magnetic field due to coupled non-parallel gradients of and .

Figure 6.

Two-pulse enhancement of THz generation in air by the spontaneous magnetic field due to coupled non-parallel gradients of and .

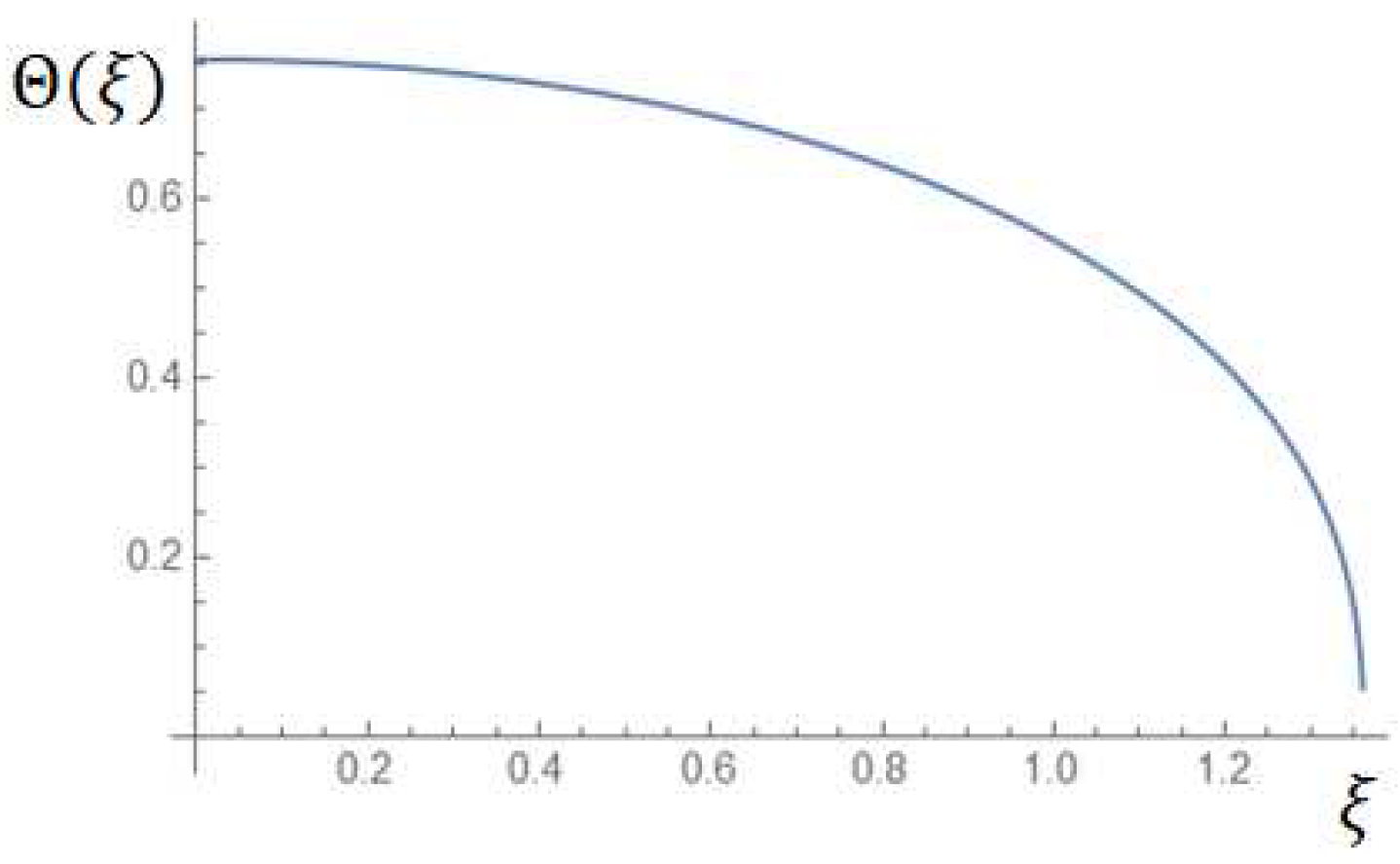

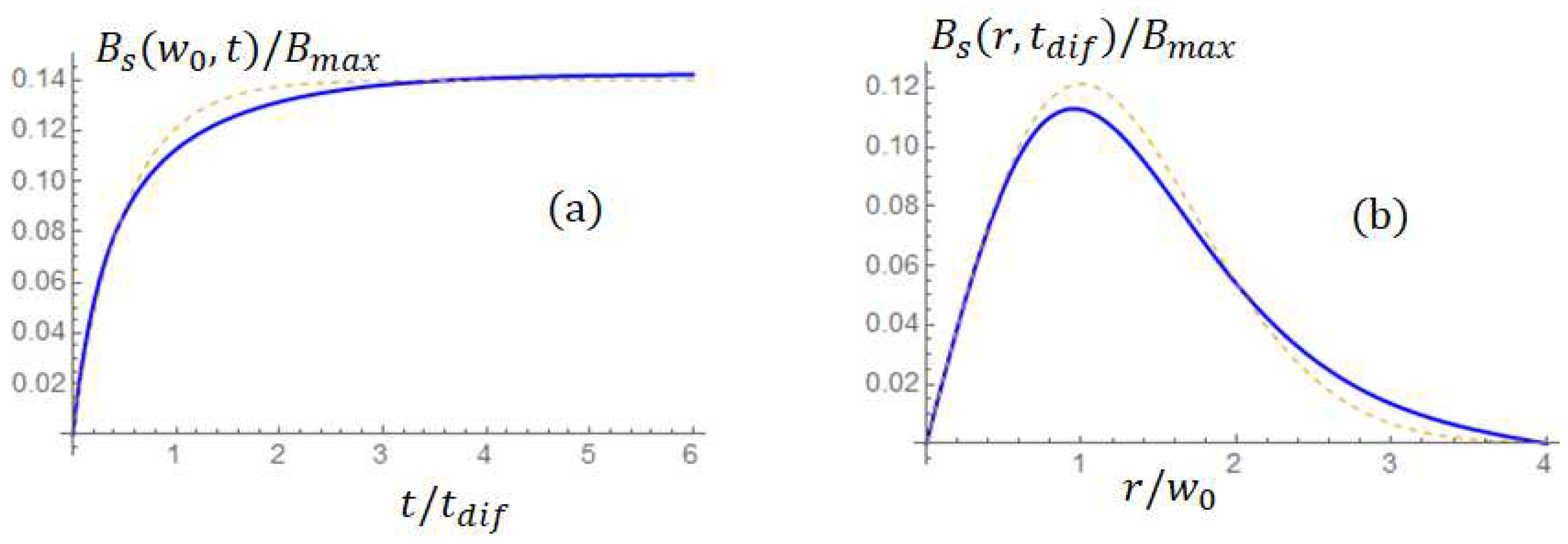

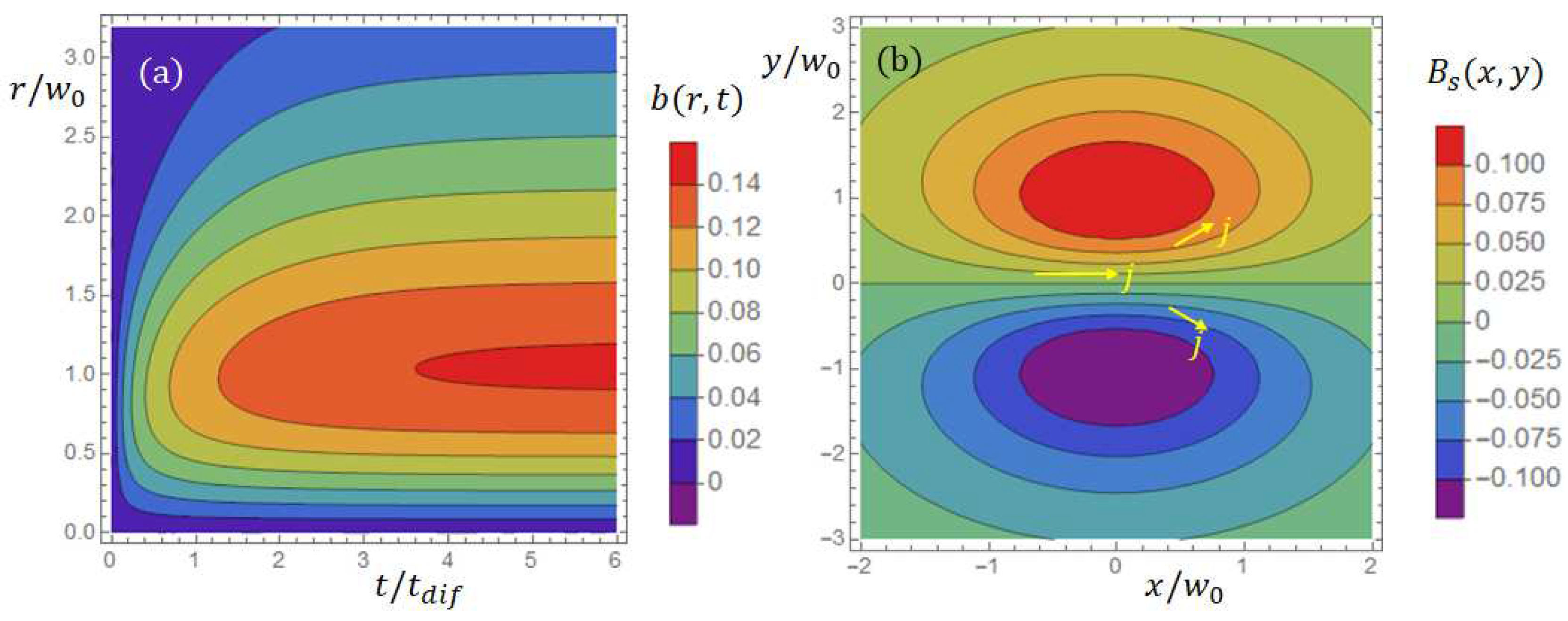

Figure 7.

(a) Time and radial dependence of the dimensionless function

obtained from a numerical solution of Eq. (

9). (b) Distribution of the magnetic field in the plane

obtained from the solution of Eq. (

8) at time

. Arrows show the direction of the electric current. The origin

and

corresponds to the laser beam axis and the maximum of the plasma density gradient.

Figure 7.

(a) Time and radial dependence of the dimensionless function

obtained from a numerical solution of Eq. (

9). (b) Distribution of the magnetic field in the plane

obtained from the solution of Eq. (

8) at time

. Arrows show the direction of the electric current. The origin

and

corresponds to the laser beam axis and the maximum of the plasma density gradient.