Submitted:

28 November 2023

Posted:

29 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Confocal Imaging

Transfection

Image Analysis

Statistics

Beads

3. Results

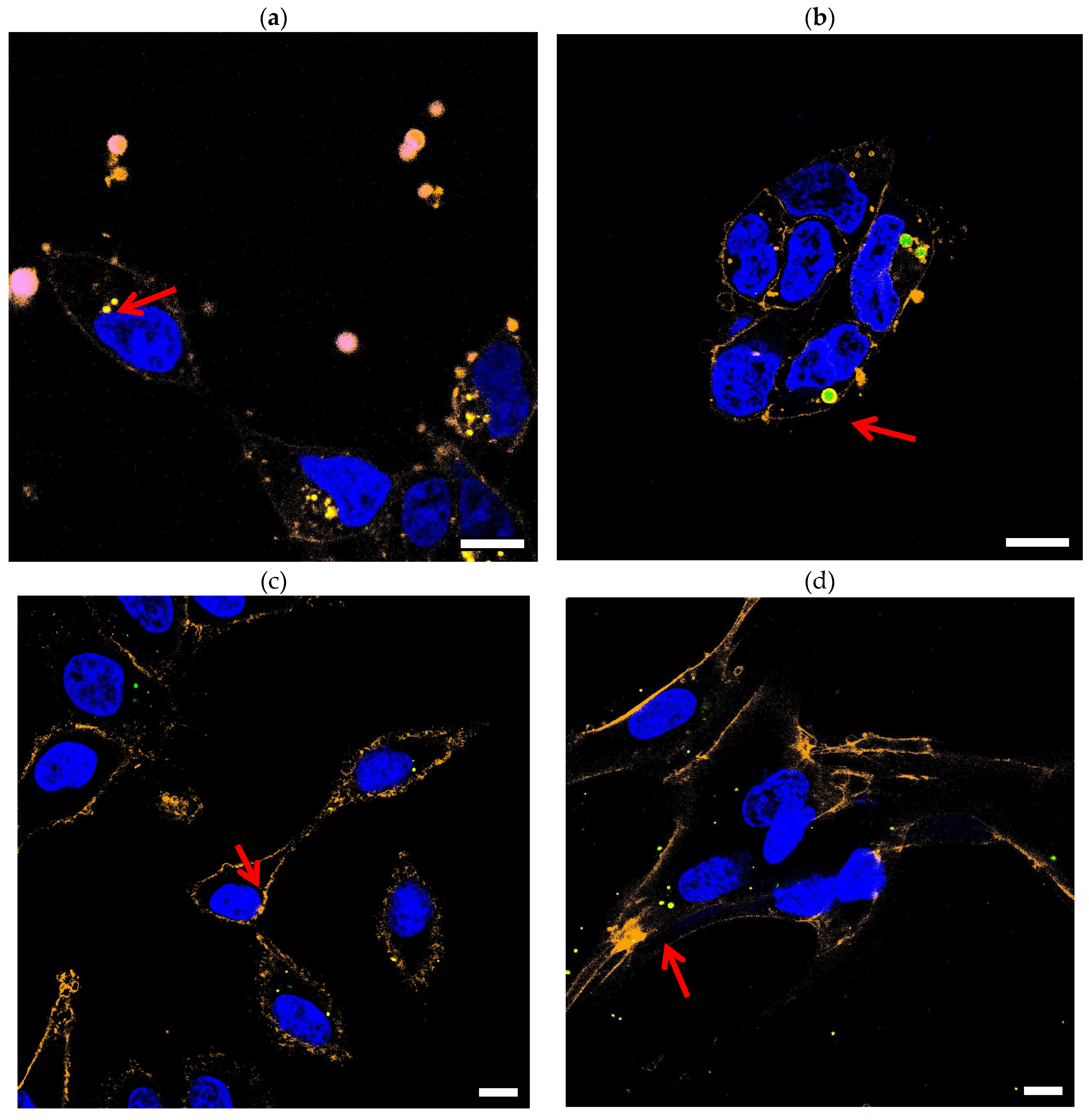

Confocal Imaging

| Figure | (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line | HEK293 | HEK293 | A549 | MRC5 |

| Average size (µm) determined | 0.54 ± 0.29 | 2.03 ± 0.19 | 0.76 ± 0.27 | 0,66 ± 0,47 |

| Average size (µm) of the beads | 0.165 | 2 | 0.165 | 0.165 |

| Polydispersity Index | 9,1 % | 8,9 % | 9,1 % | 9,1 % |

Doubling Time

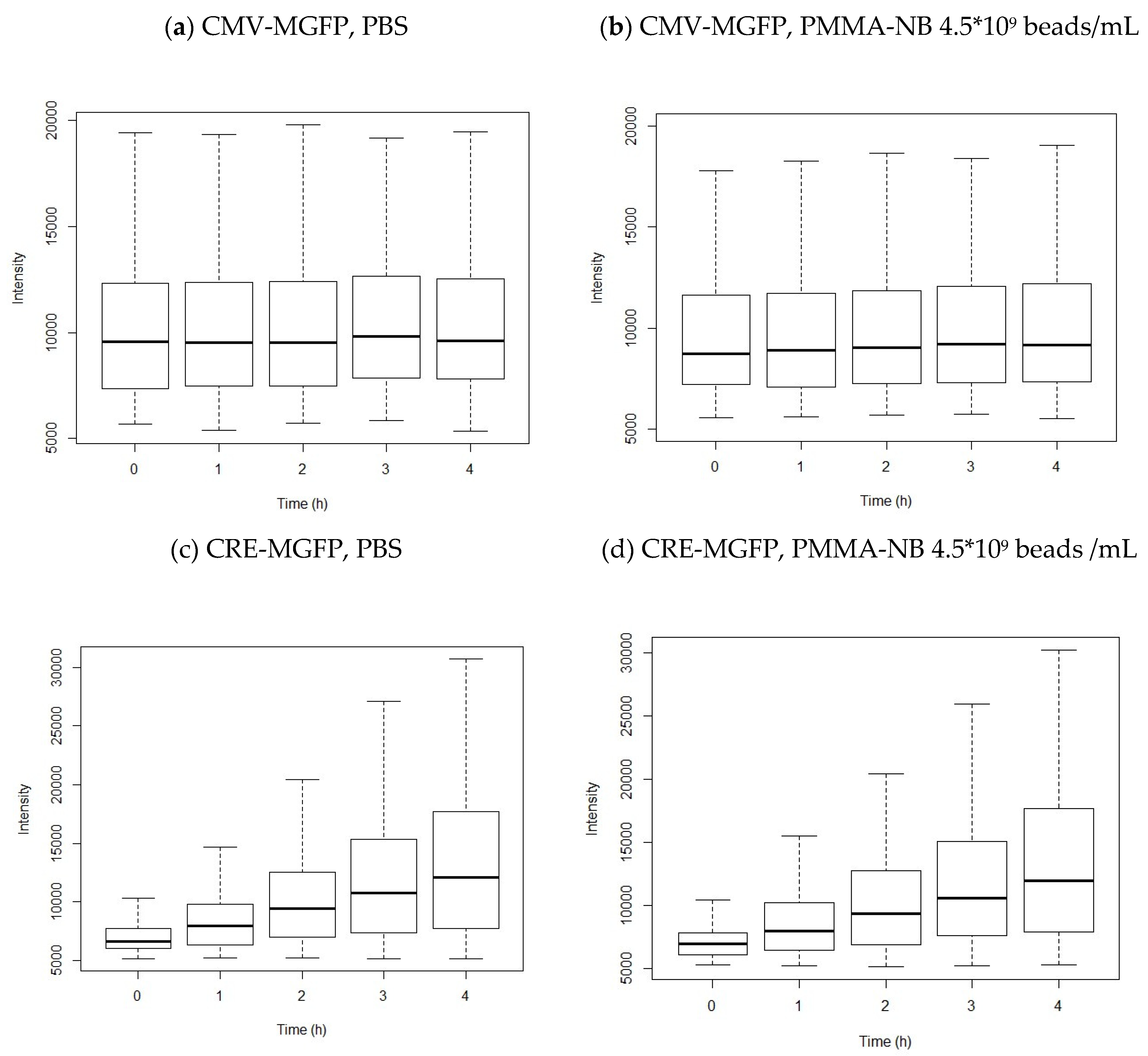

Transfection

4. Discussion

Confocal Imaging

Doubling Time

Transfection

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.J. Synthetic Polymers in the Marine Environment: A Rapidly Increasing, Long-Term Threat. Environ. Res. 2008, 108, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Review of the Methods Used for Identification and Quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, K.; Waterfield, H.; Hastings, C.; Davidson, E.; Kwietniewski, E.; Wells, B. Finding the Missing Piece of the Aquatic Plastic Pollution Puzzle: Interaction between Primary Producers and Microplastics. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2017, 2, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G. Microplastics as Vectors of Contaminants. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Dang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Ding, P.; et al. UV-Aged Microplastics Induces Neurotoxicity by Affecting the Neurotransmission in Larval Zebrafish. Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Sheng, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Lemos, B. Microplastics Induce Intestinal Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Disorders of Metabolome and Microbiome in Zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Chauhan, M.; Vaish, A. Bone Cement. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2013, 4, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Fouda, S.; Al-Harbi, F.; Näpänkangas, R.; Raustia, A. PMMA Denture Base Material Enhancement: A Review of Fiber, Filler, and Nanofiller Addition. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2017, Volume 12, 3801–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Wang, H.; Meng, S.; Zhong, W.; Li, Z.; Cai, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, X.; Du, Q. Structure and Release Behavior of PMMA/Silica Composite Drug Delivery System. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, S.; Jeyaraj, M.; Nagaraj, A.; Sadasivuni, K.K.; Rajan, M. Polymethyl Methacrylate–Ovalbumin @ Graphene Oxide Drug Carrier System for High Anti-Proliferative Cancer Drug Delivery. Appl. Nanosci. 2019, 9, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihan, T.G.; Ionita, M.D.; Popescu, R.G.; Iordachescu, D. Effect of Hydrophilic–Hydrophobic Balance on Biocompatibility of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA)–Hydroxyapatite (HA) Composites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 118, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, W.H.; Borm, P.J. Drug Delivery and Nanoparticles: Applications and Hazards. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2008, 3, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-F.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lu, T.-H.; Liao, C.-M. Toxicity-Based Toxicokinetic/Toxicodynamic Assessment for Bioaccumulation of Polystyrene Microplastics in Mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironti, C.; Notarstefano, V.; Ricciardi, M.; Motta, O.; Giorgini, E.; Montano, L. First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Urine, a Preliminary Study of Intake in the Human Body. Toxics 2022, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A.; Danne, D.; Weigel, C.; Seitz, H. An In Vitro Assay to Quantify Effects of Micro- and Nano-Plastics on Human Gene Transcription. Microplastics 2023, 2, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, S.; Serita, T. Functional Roles of CREB as a Positive Regulator in the Formation and Enhancement of Memory. Brain Res. Bull. 2014, 105, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oike, Y.; Takakura, N.; Hata, A.; Kaname, T.; Akizuki, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yasue, H.; Araki, K.; Yamamura, K.; Suda, T. Mice Homozygous for a Truncated Form of CREB-Binding Protein Exhibit Defects in Hematopoiesis and Vasculo-Angiogenesis. Blood 1999, 93, 2771–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saura, C.A.; Valero, J. The Role of CREB Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Cognitive Disorders. revneuro 2011, 22, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, J.A.; Kozal, J.S.; Jayasundara, N.; Massarsky, A.; Trevisan, R.; Geitner, N.; Wiesner, M.; Levin, E.D.; Di Giulio, R.T. Uptake, Tissue Distribution, and Toxicity of Polystyrene Nanoparticles in Developing Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 194, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Brito, W.A.; Singer, D.; Miebach, L.; Saadati, F.; Wende, K.; Schmidt, A.; Bekeschus, S. Comprehensive in Vitro Polymer Type, Concentration, and Size Correlation Analysis to Microplastic Toxicity and Inflammation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, B.; Pellegrino, M.; Tombelli, S.; Trono, C.; Giannetti, A.; Domenici, C.; Varchi, G.; Sotgiu, G.; Ballestri, M.; Baldini, F. Polymeric Nanoparticles Promote Endocytosis of a Survivin Molecular Beacon: Localization and Fate of Nanoparticles and Beacon in Human A549 Cells. Life Sci. 2018, 215, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.P.; Jones, C.M.; Baille, J.P. Characteristics of a Human Diploid Cell Designated MRC-5. Nature 1970, 227, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, W.C.; Graham, F.L.; Smiley, J.; Nairn, R. Characteristics of a Human Cell Line Transformed by DNA from Human Adenovirus Type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 1977, 36, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assanga, I. Cell Growth Curves for Different Cell Lines and Their Relationship with Biological Activities. Int. J. Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. Res. 2013, 4, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, A.; Schallon, A.; Pietsch, C.; Schubert, S.; Nomoto, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kataoka, K.; Schubert, U.S. A Toolbox of Differently Sized and Labeled PMMA Nanoparticles for Cellular Uptake Investigations. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftig, P.; Klumperman, J. Lysosome Biogenesis and Lysosomal Membrane Proteins: Trafficking Meets Function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.L.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, L.; Hirsch, V.; Balog, S.; Urban, D.; Jud, C.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Lattuada, M.; Petri-Fink, A. Nanoparticle Colloidal Stability in Cell Culture Media and Impact on Cellular Interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6287–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, D.C.; Staiano, L.; Guimas Almeida, C.; Cutler, D.F.; Eden, E.R.; Futter, C.E.; Galione, A.; Marques, A.R.A.; Medina, D.L.; Napolitano, G.; et al. Current Methods to Analyze Lysosome Morphology, Positioning, Motility and Function. Traffic 2022, 23, 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Akhtar, S.; Almohazey, D.; Alomari, M.; Almofty, S.A.; Badr, I.; Elaissari, A. Targeted Delivery of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) Particles in Colon Cancer Cells Selectively Attenuates Cancer Cell Proliferation. Artif. Cells Nanomedicine Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuser, P.E.; Gaspar, P.C.; Ricci-Júnior, E.; Silva, M.C.S.D.; Nele, M.; Sayer, C.; H. H. De Araújo, Pedro. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) PMMA and Evaluation of Cytotoxicity for Biomedical Application. Macromol. Symp. 2014, 343, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windheim, J.; Colombo, L.; Battajni, N.C.; Russo, L.; Cagnotto, A.; Diomede, L.; Bigini, P.; Vismara, E.; Fiumara, F.; Gabbrielli, S.; et al. Micro- and Nanoplastics’ Effects on Protein Folding and Amyloidosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Cong, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, X.; Duan, Z.; Wang, L. Nanoplastic-Protein Corona Interactions and Their Biological Effects: A Review of Recent Advances and Trends. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 166, 117206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell line | Ø | Beads/mL | tD (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293 | 165 nm | 4.5*109 | 26.00 ± 3.85 |

| 4.5*108 | 25.96 ± 3.49 | ||

| 0 | 27.44 ± 2.33 | ||

| 2 µm | 2.53*106 | 28.84 ± 2.95 | |

| 2.53*105 | 29.94 ± 3.01 | ||

| 0 | 29.56 ± 2.75 | ||

| A549 | 165 nm | 4.5*109 | 30.84 ± 1.64 |

| 4.5*108 | 33.17 ± 3.89 | ||

| 0 | 29.86 ± 1.62 | ||

| 2 µm | 2.53*106 | 29.21 ± 1.36 | |

| 2.53*105 | 28.61 ± 3.30 | ||

| 0 | 29.44 ± 2.76 | ||

| MRC5 | 165 nm | 4.5*109 | 51.26 ± 7.91 |

| 4.5*108 | 46.30 ± 4.66 | ||

| 0 | 45.44 ± 4.37 | ||

| 2 µm | 2.53*106 | 45.16 ± 7.56 | |

| 2.53*105 | 47.48 ± 9.07 | ||

| 0 | 46.25 ± 7.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).