3. Results

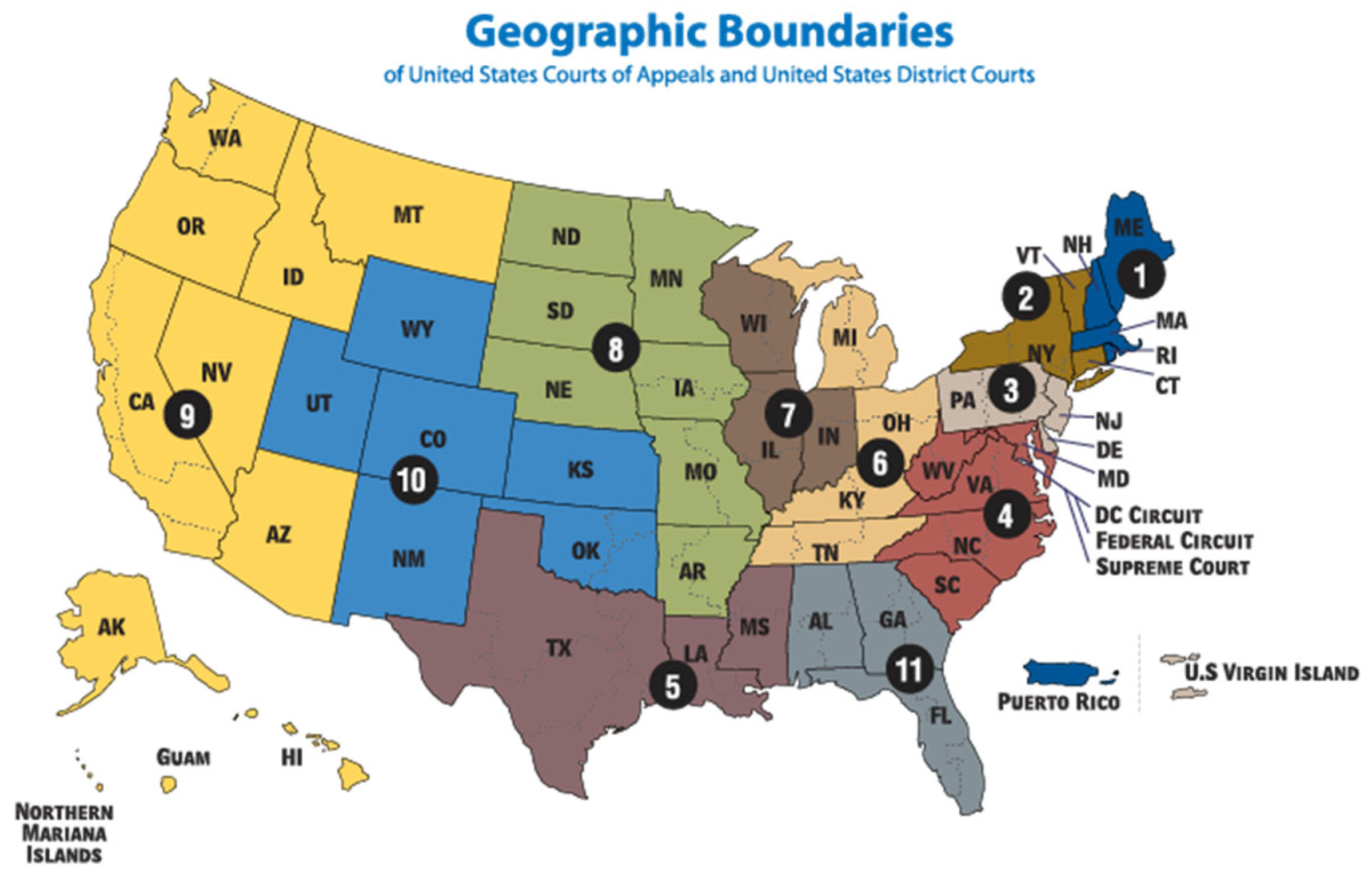

The cases are categorized by type of persecution, Circuit Court, and use of the term trauma. The categories of gender-based asylum claims are Female Genital Mutilation (N=23, including combined cases with forced marriage and rape), Domestic Violence (N=4, including combined cases with rape), Coercive Population Control (N=23, including combined cases with rape), and Rape (N=51). The number of cases for each Circuit Court are: First Circuit (N=10), Second Circuit (N=12), Third Circuit (N=11), Fourth Circuit (N=7), Fifth Circuit (N=3), Sixth Circuit (N=13), Seventh Circuit (N=9), Eighth Circuit (N=5), Ninth Circuit (N=21), Tenth Circuit (N=2), and Eleventh Circuit (N=8). The number of cases by trauma coding are precedent cases (trauma Coding =1) (N=31), psychological trauma (trauma coding =2) (N=58), physical trauma (trauma coding = 3) (N=18), and cases that reference other U.S. policy or reports or international reports (trauma coding = 4) (N=4). Please note that several cases have multiple trauma codes (trauma codes are not mutually exclusive) and the number is more than the total cases.

3.1. Type of Persecution and U.S. Circuit Court

The number of FGM cases (N=23) for each Circuit Court are: First Circuit (N=0), Second Circuit (N=3), Third Circuit (N=1), Fourth Circuit (N=4), Fifth Circuit (N=0), Sixth Circuit (N=5), Seventh Circuit (N=3), Eighth Circuit (N=1), Ninth Circuit (N=3), Tenth Circuit (N=1), and Eleventh Circuit (N=2). There were only four Circuit Court cases with a Domestic Violence claim. The First, Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth Circuit Court had one case each. The number of CPC cases (N=23) for each Circuit Court are: First Circuit (N=2), Second Circuit (N=7), Third Circuit (N=3), Fourth Circuit (N=0), Fifth Circuit (N=1), Sixth Circuit (N=0), Seventh Circuit (N=1), Eighth Circuit (N=0), Ninth Circuit (N=6), Tenth Circuit (N=0), and Eleventh Circuit (N=3). The number of rape cases (N=51) for each Circuit Cout are: First Circuit (N=7), Second Circuit (N=2), Third Circuit (N=7), Fourth Circuit (N=3), Fifth Circuit (N=2), Sixth Circuit (N=7), Seventh Circuit (N=4), Eighth Circuit (N=4), Ninth Circuit (N=11), Tenth Circuit (N=1), and Eleventh Circuit (N=3).

3.2. Type of Persecution and Use of the Term Trauma

The number of cases when a precedent case (Trauma Coding =1) is referenced by type of persecution are as follows: FGM (N=16), CPC (N=8), and rape (N=7). The number of cases when psychological trauma (Trauma Coding =2) is referenced by type of persecution are as follows: FGM (N=5), DV (N=3), CPC (N=12), and rape (N=38). The number of cases when physical trauma (Trauma Coding =3) is referenced by type of persecution are as follows: FGM (N=4), DV (N=2), CPC (N=5), and rape (N=7). There were only four cases that referenced other U.S. policies or reports or international reports, one for a CPC case and three for rape cases.

3.3. Circuit Court and Use of the Term Trauma

The number of cases when a precedent case (Trauma Coding =1) is referenced for each Circuit Court are: First Circuit (N=1), Second Circuit (N=6), Third Circuit (N=2), Fourth Circuit (N=4), Fifth Circuit (N=1), Sixth Circuit (N=3), Seventh Circuit (N=3), Eighth Circuit (N=0), Ninth Circuit (N=7), Tenth Circuit (N=1), and Eleventh Circuit (N=3). The number of cases when psychological trauma (Trauma Coding =2) is referenced for each Circuit Court are: First Circuit (N=8), Second Circuit (N=4), Third Circuit (N=8), Fourth Circuit (N=3), Fifth Circuit (N=2), Sixth Circuit (N=7), Seventh Circuit (N=5), Eighth Circuit (N=4), Ninth Circuit (N=12), Tenth Circuit (N=1), and Eleventh Circuit (N=4). The number of cases when physical trauma (Trauma Coding =3) is referenced for each Circuit Court are: First Circuit (N=1), Second Circuit (N=3), Third Circuit (N=1), Fourth Circuit (N=1), Fifth Circuit (N=0), Sixth Circuit (N=4), Seventh Circuit (N=2), Eighth Circuit (N=1), Ninth Circuit (N=3), Tenth Circuit (N=0), and Eleventh Circuit (N=2). There were only four cases that referenced other U.S. policies or reports or international reports, one of which was in the Third Circuit and three were in the Ninth Circuit.

4. Discussion

4.1. Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

In 1996 the BIA granted Fauziya Kassindja asylum based on her fear of being subjected to the practice of FGM [

58]. Her case,

Matter of Kasinga, set a precedent for FGM being a form of persecution [

59]. It established the legal basis for extending protection to any immigrant woman claiming asylum for herself based on a fear of FGM (future persecution), the occurrence of FGM (past persecution), or the fear that her daughters would experience FGM in the future. The description of FGM outlined in

Matter of Kasinga stated that:

FGM is extremely painful and at least temporarily incapacitating. It permanently disfigures the female genitalia. FGM exposes the girl or woman to the risk of serious, potentially life-threatening complications. These include, among others, bleeding, infection, urine retention, stress, shock, psychological trauma, and damage to the urethra and anus. It can result in permanent loss of genital sensation and can adversely affect sexual and erotic functions.

It is this description of “psychological trauma” that contains the only use of the term trauma in the precedent case.

Of the twenty-three FGM cases analyzed, sixteen reference the term trauma when quoting the Matter of Kasinga case (trauma coding = 1) with fifteen of the cases only using the term trauma from Matter of Kasinga and not in the context of the case that was under appeal. For the thirteen cases that were denied, judges reasoned that FGM was in decline or illegal in the country the applicant fled, that parents who objected could intervene, or that it was not a reasonable fear. Those who had been subjected to the practice and/or feared it happening to their daughters condemned it and recounted memories of fear, anguish, and betrayal when describing their own experiences of FGM. Several cases upheld the legal reasoning that FGM could not be repeated making it impossible to argue that women should not be returned to a country that would harm them as the persecution was in the past.

A Ninth Circuit case, Mohammed v. Gonzales, 400 F.3d 785, changed this logic when the Court granted and remanded it arguing that FGM is a “permanent and continuing act of persecution” using the language of a forced sterilization case, Qili Qu v. Gonzales, 399 F.3d 1195, that the same Circuit Court decided just two days prior. Fear of future persecution can include the applicant and/or the applicant’s daughters, even when the children are U.S. citizens. In Mohammed v. Gonzales, 400 F.3d 785 the Court found that:

Like forced sterilization, genital mutilation permanently disfigures a woman, causes long term health problems, and deprives her of a normal and fulfilling sexual life. The World Health Organization reports that even the least drastic form of female genital mutilation can cause a wide range of complications such as infection, hemorrhaging from the clitoral artery during childbirth, formation of abscesses, development of cysts and tumors, repeated urinary tract infections, and pseudo infibulation. Many women subjected to genital mutilation suffer psychological trauma. In addition, it "can result in permanent loss of genital sensation and can adversely affect sexual and erotic functions." Thus, "in addition to the physical and psychological trauma that is common to many forms of persecution [female genital mutilation] involves drastic and emotionally painful consequences that are unending." Therefore, our precedent compels the conclusion that genital mutilation, like forced sterilization, is a "permanent and continuing" act of persecution, which cannot constitute a change in circumstances sufficient to rebut the presumption of a well-founded fear.

While U.S. citizen children are not under threat of deportation, those in mixed-status families – families comprised of members with varying immigration statuses – either migrate with their deported parents or are left with relatives or others in the U.S. In the Seventh Circuit case Nwaokolo v. INS, 314 F.3d 303, a claimant from Nigeria who feared her two U.S. citizen daughters would be subjected to FGM, the Circuit granted a stay (halting deportation actions against the petitioner) because “a stay promotes the public's compelling interest in ensuring that minor United States citizens are not forced into exile to be tortured.”

The one case that referenced Matter of Kasinga and trauma of the applicant was a Fourth Circuit case, Mame Fatou Niang v. Gonzales, 492 F.3d 505. In this case, the petitioner argued that she would experience psychological harm if her U.S. citizen daughter were forced to undergo FGM. Her own experience of FGM was characterized as physical trauma:

Niang also asserted that her psychological development was "considerably hampered," by the physical trauma that she experienced as a young girl. She stated that "[t]he pains that I went through and the blood that was shed on [the day she was mutilated] keeps on revisiting me up until today."

In this example, the applicant’s retelling of her own experience focused on physical trauma and the fear of future persecution for her daughter was rooted in the psychological realm that had not yet occurred.

Of the twenty-three FGM cases, five referenced psychological trauma (trauma coding =2). In the Seventh Circuit case Kone v. Holder, 620 F.3d 760, the petitioners were a mother and two daughters, the oldest of whom had undergone FGM without the parents’ knowledge or consent and the youngest – a U.S. citizen - whom the parents feared would be cut if they were forcibly returned to Mali. In her immigration court hearing, Kone testified that she would feel “emotional trauma” if FGM were performed on her daughter against her will. Here the emotional trauma was not the daughter’s – the one subjected to FGM – but rather the mother’s trauma who was powerless as she could not prevent it. In the Eighth Circuit case Kipkemboi v. Gonzales, 211 Fed. Appx. 530, Kipkemboi argued that she and her daughter would be subjected to FGM if returned to Kenya and that the “emotional trauma associated with witnessing the pain and suffering of the child would constitute persecution.” In the Ninth Circuit case Azanor v. Ashcroft, 364 F.3d 1013, the petitioner Azanor outlined how she had been subjected to FGM against her will when she was four months pregnant by her boyfriend’s relatives resulting in a premature birth. The following describes the trauma of FGM.

The declaration recounts the events surrounding Azanor's FGM and describes the physical discomfort and psychological trauma she has endured as a result of this procedure. According to the declaration, Azanor still experiences regular pelvic pain, urinary tract infections, and rashes due to her FGM. Memories of the procedure continue to haunt her thoughts, triggering recurring nightmares and panic attacks. A letter from her physician confirms this medical history and indicates further that she has received treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Depressive Disorder associated with her FGM.

The next two cases include FGM and rape as forms of gendered harm. In the Sixth Circuit case Sene v. United States AG, 679 Fed. Appx. 463, the petitioner described racial and other forms of persecution she and her family endured in Mauritania. At the age of ten she was raped by military personal when her family was detained, just five years after she had undergone FGM. In her dissent decision, Justice Donald wrote:

this continuing and permanent effect of female genital mutilation is clearly supported by the facts of this case, and many more like it, where the victim suffers from emotional and psychological trauma stemming from the mutilation well into her adulthood.

Rape and FGM as combined forms of harm appear in other cases too. In the Sixth Circuit case Sene v. Gonzales, 168 Fed. Appx. 61, Mame Sene was kidnapped and tortured by Senegalese security forces. She was gang raped and the soldiers cut her labia minor and majora. The petitioner submitted medical records that indicated both physical and psychological trauma.

Petitioner's psychologist, Adeyinka M. Akinsulure-Smith, wrote “in my clinical and professional opinion, [Petitioner] displays significant symptoms associated with Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. These findings are consistent with the severe physical and emotional trauma that she reports experiencing in the past.

In this example, trauma from FGM and the rape are inextricably linked.

Of the twenty-three FGM cases, four referenced physical trauma (trauma coding =3). In the Second Circuit case Jalloh v. Lynch, 662 Fed. Appx. 97, the petitioner, a father of daughters whom he feared would undergo FGM, had been beaten during the civil war in Sierra Leone from which he suffered physical trauma to his nose and mouth area causing him to lose several teeth. In this case, the physical trauma is not about FGM but the beating the applicant endured. Unfortunately, his testimony was inconsistent and he also said that he did not remember how he hurt his nose and that his problems with his teeth were due to routine dental issues. In the Sixth Circuit case Diallo v. Mukasey, 2007 U.S. App. LEXIS 29641, Cherif Diallo was detained and raped for her political activities in Guinea. Diallo had also undergone FGM at the age of six. Like Diallo, Bah also had FGM when she was young, at the age of seven. In the Sixth Circuit case Bah v. Gonzalez, 230 Fed. Appx. 547, Bah outlined how she had been politically active and was raped in her home and later in prison. Three of the four cases of FGM and rape (all except the Sixth Circuit case Sene v. Gonzales, 168 Fed. Appx. 61) are of women who experienced FGM at a young age and were later raped. During their testimony, they articulated how their motivation for leaving their country was tied to the harm of rape, not FGM.

Three cases include the harm of FGM and forced marriage. In the Fourth Circuit case Haoua v. Gonzales, 472 F.3d 227, the petitioner, Haoua Mahaman feared returning to Niger as her parents had arranged a forced marriage that required she have FGM before the wedding. In the Fourth Circuit case Gomis v. Holder, 571 F.3d 353, Francoise Anate Gomis sought relief from deportation as she too feared being subjected to FGM and a forced marriage in Senegal. Her father had written to her that “I think all means will be necessary to bring you back in Senegal, and I mean it. You'll be circumcised and sent into marriage before my death. I will never forgive you, if you don't return to Dakar for the circumcision.” In these cases, the applicants fled because their families required that they be circumcised so that they could marry. In the Eleventh Circuit case Manani v. Filip, 552 F.3d 894, a woman from Kenya who had experienced FGM as a child and was fleeing a forced marriage by her late husband’s brother after his death. The Court denied her claim and stated that “While Manani stated in her application for asylum that she was "circumcised" as a child and testified before the IJ [immigration judge] that FGM is a "very, very painful" procedure, she did not introduce her personal trauma as an affirmative claim for relief.” Here, the Court referred to the applicant’s trauma as “personal” (meaning FGM) and chastised her for not having it as a central part of her claim implying that the forced marriage component was not sufficient to gain asylum.

4.2. Domestic Violence

The number of domestic violence cases that use the language of trauma is small; a total of four cases made their way to the appellate courts. Two of the domestic violence cases refer to psychological trauma, one referenced physical trauma, and one referenced both psychological and physical trauma. Three of the four include rape as part of the claim. In the Sixth Circuit case Martinez-Martinez v. Sessions, 743 Fed. Appx. 629, the psychological evaluation indicated that Martinez suffered psychological trauma from the physical and emotional abuse of her husband. This was the only domestic violence case that did not also involve sexual assault. In the Ninth Circuit case Gasparyan v. Holder, 707 F.3d 1130, Gasparyan fled Armenia from an abusive husband. She testified that she suffered from “nightmares and other psychological trauma related to the domestic violence she endured.” She lived with her husband’s family in the U.S. and they promised not to reveal to him her whereabouts. She told an immigration judge that her “mental health quickly deteriorated because the trauma she suffered as a consequence of the domestic violence resurfaced while living with her husband's family.” A forensic psychologist examined her, diagnosed her with anxiety disorder, and documented her PSTD symptoms.

The First Circuit case De Pena-Paniagua v. Barr, 957 F.3d 88 only referenced trauma in the context of physical harm. Evidence included “medical records from the hospital visit indicated that she had "bruised trauma of the face, chest, and right arm." De Pena reported this attack to the local police, who labeled the incident, "Death Threat & Attempted Homicide." This was the only reference to trauma even though she had been raped multiple times, including while pregnant. In the Seventh Circuit case Ferreira v. Lynch, 831 F.3d 803, trauma was used to refer to both psychological and physical aspects. Ferreira, a citizen of the Dominican Republic, fled her common-in-law husband who her beat and sexually assaulted her. One medical report documented “the physical and psychological trauma she sustained as a result of the 2007 sexual assault.” The report was among other evidence from a physician that revealed that “bruises and scratches on Jimenez's body, as well as "visible signs and marks of a strangulation attempt" and a "torn inner and outer labia of the vagina, evidencing penetration by force or with resistance on the part of the victim"; and a psychologist's report that states that Jimenez "presents signs and symptoms of tension, worry, fear for her life and the lives of her family" and recommends "[t]hat she be referred immediately to group therapy" to "help her overcome the trauma."

4.3. Coercive Population Control (CPC)

In 1996, the U.S. Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act (IIRRA). While IIRRA overwhelmingly made immigration to the U.S. more restrictive, it provided an opening for migrants from China fleeing coercive population control measures such as forced abortions and forced sterilizations. The Act defined political opinion as the ground on which the persecution was linked. Soon after, several immigration cases made their way to the BIA, challenging how IIRRA was being implemented. In the 1997 case

Matter of C-Y-Z, the BIA ruled that spouses were eligible for asylum if their wife or husband had been subjected to CPC, even if they had not [

60]. A Ninth circuit case,

Ma v Ashcroft, found that this extended to those whom the Chinese government did not recognize as legally married, typically for those who wed without the Chinese government’s approval [

61]. A Third Circuit case,

Chen v Ashcroft, a Fifth Circuit case,

Zhang v Ashcroft, and

Matter of C-Y-Z, upheld the trend that unmarried partners such as boyfriends and finances were not eligible for asylum [

62,

63,

64].

Of the twenty-three CPC cases, eight reference the term trauma in the context of precedent cases (trauma coding = 1). Six of these cases reference the Qili Qu v. Gonzales, a Ninth Circuit case, including the case itself. Qu and his wife were denied a birth permit because of their political affiliation with an organization that was a Christian group that supported pre-communist government policies. They defied the Chinese government by having a child without permission for which their punishment was to have Qu’s wife forcibly sterilized. The Court found that Qu was eligible for asylum based solely on his wife’s persecution (he was not sterilized). The Ninth Circuit found that:

In addition to the physical and psychological trauma that is common to many forms of persecution, sterilization involves drastic and emotionally painful consequences that are unending: The couple is forever denied a procreative life together.

It continued by quoting the BIA’s decision, Matter of Y-T-L, from 2003:

As the BIA explained, The act of forced sterilization should not be viewed as a discrete onetime act, comparable to a term in prison, or an incident of severe beating or even torture. Coerced sterilization is better viewed as a permanent and continuing act of persecution that has deprived a couple of the natural fruits of conjugal life, and the society and comfort of the child or children that might eventually have been born to them [

65].

The Ninth Circuit expanded this logic to forced abortion and stated the following about psychological trauma in a footnote “Forced abortion, as a form of persecution, possesses similar unusual characteristics. Again the pain, psychological trauma, and shame are combined with the irremediable and ongoing suffering of being permanently denied the existence of a son or daughter.”

Three other cases were granted that referenced Qu. In Zi Zhi Tang v. Gonzales, 489 F.3d 987, the Ninth Circuit found that “Both forced abortion and forced sterilization share "unusual characteristics" including the "pain, psychological trauma, and shame" resulting from a forced procedure.” In Zhang v. Gonzales, 434 F.3d 993, the Seventh Circuit granted a case referencing the psychological trauma the Ninth Circuit used in Qu. In Yuqing Zhu v. Ashcroft, 382 F.3d 521, the Fifth Circuit quoted a Ninth Circuit case, Zi Zhi Tang v. Gonzales, 489 F.3d 987 that portrayed CPC practices as creating psychological trauma for both forced abortion and sterilization claims.

Forced abortion and forced sterilization share unusual characteristics including the pain, psychological trauma, and shame resulting from a forced procedure. Both forms of persecution have serious, ongoing effects. A woman who has had a forced abortion has experienced unwanted governmental interference into one of the most fundamental and personal of decisions: whether she will have a child. The effects of that intrusion last a lifetime. There is no way to distinguish between the victims of forced sterilization and the victims of forced abortion for withholding of removal eligibility purposes. There is no reasoned basis for distinguishing between these two recognized forms of persecution in the context of withholding of removal. Thus, the presumption of future harm applies equally to forced abortions.

Three cases were denied, two of which referenced Qu and one other case. In Zhongxiang Zhou v. Lynch, 618 Fed. Appx. 907, the Ninth Circuit denied a case when it cited its own precedent case, Qu, and used the language of trauma to describe CPC practices as “physical and psychological trauma that is common to many forms of persecution.” In Zhang v. Gonzales, 434 F.3d 993, the court also quoted Qu regarding the “psychological trauma” and continued with:

In fact, an even stronger argument may exist that the presumption is necessarily rebutted in involuntary abortion cases, because the applicant may still face additional persecution in the future in the form of more forced abortions, involuntary sterilization, and other coercive population control practices.

In Shi Liang Lin v. United States DOJ, a case of multiple petitioners all of whom were unmarried partners of women who had been forced to abort a pregnancy, the Second Circuit debunked the logic of the BIA and the Ninth Circuit that the harm of CPC practices was as much to the partner as the one who had experienced the forced abortion or sterilization, denied the three petitioners and acknowledged the split between the Circuit Courts. A Ninth Circuit case, Hui Chen v. Gonzales, referenced a precedent case from its own Circuit other than Qu, Zhang v. Gonzales, 408 F.3d 1239, and denied the petitioner as the Court determined that he was not “subjected to the severity of trauma” that Zhang experienced.

A fifth Circuit case, Yuqing Zhu v. Ashcroft, 382 F.3d 521 that was dismissed due to jurisdictional issues quoted a Ninth circuit case, Zi Zhi Tang v. Gonzales, 489 F.3d 987 that compared the psychological trauma of forced abortions and sterilizations. In the Eleventh Circuit case Biru Chen v. United States AG, 181 Fed. Appx. 951, the court cited a case from the Ninth Circuit, Singh, 292 F.3d at 1023, to address trauma that may occur when migrants interact with government officials.

The decisions cited by Chen stand generally for the proposition that airport interviews should be viewed with caution when making credibility determinations because (1) it is unknown what the circumstances of the interrogation were; (2) linguistic problems result in questions not being understood and translations being misinterpreted; (3) the nature of the interrogation is different than the opportunity afforded to explain an asylum application; and (4) the potential trauma that may prevent an alien from disclosing the information surrounding his asylum claim because of previous abusive interrogations by government officials in his home country.

Similar to FGM cases, the Court may grant or deny an appeal even when referencing a precedent case that recognized the harm as persecution.

Of the twenty-three CPC cases, twelve reference the term trauma when discussing psychological trauma (trauma coding = 2). Only three of which were granted an appeal or remanded, including the precedent case Qili Qu v. Gonzales. Themes of how the language of psychological trauma was part of CPC cases include traumatic memory, trauma from others being harmed, such as a relative, and trauma that does not rise to the level of persecution. In several cases, the court considered CPC practices inherently traumatic. In the Second Circuit case Xian Gui Chen v. Gonzales, 157 Fed. Appx. 430 the appeal was denied, in part by upholding the BIA’s justification that Chen did not provide enough detail of his wife’s abortion even though the court stated that “the trauma of a forced abortion might well cause any wife to avoid discussing any details with her husband.” In the Third Circuit case Zhang v. AG United States, 632 Fed. Appx. 680, Zhang was denied an appeal because she did not corroborate her claim that she was persecuted but instead “focused on the emotional trauma that she had suffered in China, and that her "great trauma and pain" should excuse her lack of corroboration.”

The language of trauma is often linked to memory. In the First Circuit case Hong Mei Zhang v. Gonzales, 469 F.3d 51, Zhang did not mention her forced abortion in her application because “she could not face a resumption of the psychological trauma which that memory triggered.” In the Second Circuit case Zhao v. Barr, 791 Fed. Appx. 265, Zhao testified that she was unfamiliar with paperwork documenting her forced abortion. When a copy of her medical visit was presented to the Court Zhao “explain[ed] that she suffered a "memory lapse" not uncommon among trauma victims and posits that she might have "thr[own] [the abortion certificate] in a pile of papers and never looked at it." In the Ninth Circuit case Han v. Garland, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 16753, the applicant was denied based on inconsistent testimony about “when her pregnancies and alleged forced abortions occurred, when she was allegedly arrested for her religion, how many times and where she was sexually assaulted, and who found her and transported her to the hospital following her alleged suicide attempt.” While her “faulty memory due to the passage of time, and trauma” was considered, the case was denied.

In the Third Circuit case

Meishan Zhao v. AG of the United States, 388 Fed. Appx. 135, Zhao argued that corroborating her claim was traumatic. Zhao was taken away by family planning officials and subjected to a forced abortion. She was also involved in a Christian church and while being interrogated she was beaten and raped by a police officer. She argued that “she has post-traumatic stress disorder and that requiring her to corroborate her claims is unreasonable as it would cause her to relive the trauma that she suffered.” The Court ruled that “While Zhao was undoubtedly traumatized by the events she described, we have not held that such trauma relieves a petitioner of the requirement to proffer reasonably available evidence that corroborates her claim,” and cited a Third Circuit case,

Fiadjoe v. Att'y Gen., 411 F.3d 135, noting that “the petitioner, whom, for eleven years was held by her father as a slave and subjected to physical beatings and frequent rape, corroborated her claim with United States Department of State Country Reports and a report by a psychologist who treated her for trauma” implying that even a child can talk about traumatic events [

66].

Two cases use the language of trauma when the petitioner’s trauma was due to a family member’s persecution. In the Ninth Circuit case Zhang v. Gonzales, 408 F.3d 1239, the applicant discussed “the trauma of witnessing her father's forcible removal from her home” to be forcibly sterilized. In the Eleventh Circuit case Qin Liu v. United States AG, 252 Fed. Appx. 964, Liu claimed that “his wife's forced abortion and sterilization resulted in his emotional trauma and psychological persecution.” Both cases were denied.

Two cases did not consider the harm to rise to the level of persecution. In the First Circuit case

Lin v. Holder, 570 Fed. Appx. 4, Lin argued that his wife was forcibly sterilized and that he was beaten in front of his daughter. The Court found that “there is no reason to infer that Lin's psychological trauma was any greater than that of petitioners in two other First Circuit cases where “the effect of watching his father be beaten as a young child, although traumatic, did not amount to persecution” [

67,

68]. In the Second Circuit case

Bing Shui Lin v. Gonzales, 232 Fed. Appx. 54, the Court ruled that Lin’s “harassment by Chinese family planning officials and resulting trauma did not constitute severe abuse or rise to the level of persecution because the officials targeted his parents when [he] was a child.” In both cases the Court considered trauma not to rise to the level of persecution.

Of the twenty-three CPC cases, five reference the term trauma when discussing physical trauma (trauma coding = 3). All were denied except the precedent case Qili Qu v. Gonzales, discussed earlier and all had a male petitioner. In the Second Circuit case Lian v. Holder, 405 Fed. Appx. 524, that also referenced psychological trauma, family planning officials “pushed him and caused him to hit his head” resulting in “head trauma” but that this was only “physical mistreatment” and not persecution. In the Eleventh Circuit case Shijie Huang v. United States AG, 330 Fed. Appx. 871, the Court stated that “Huang's detention and beating do not rise to the level of persecution. It does not appear that Huang required medical treatment following the beating, and there is no evidence that he suffered any lasting effects or other mistreatment” and that his experiences were not the same “level of severity” as others, such as those who experienced “trauma from torture.”

The other two cases reference trauma in the context of credibility. In the Third Circuit case Chen v. Ashcroft, 376 F.3d 215, the Court found that Chen’s testimony was not credible stating that his:

wife had an IUD inserted on the same day she had an abortion as "not only incredible but also implausible." The IJ [immigration judge] reasoned that "due to the physical trauma of an abortion, the Court finds that it is unlikely and most likely physically impossible to insert an IUD in an individual who has earlier that day suffered an abortion."

In the Second Circuit case Wensheng Yan v. Mukasey, 509 F.3d 63, the Court referenced the physical and emotional trauma that accompanies a forced abortion. It stated that:

Any reasonable person would understand why the IJ [immigration judge] here concluded that it is implausible that a man whose wife had just undergone the physical and emotional trauma of a forced abortion would, only days later, travel alone to another country to participate in a vacation with a tour group for no asserted purpose other than pleasure.

In both cases, the Court found the petitioner non-credible given the traumatic physical experience of a forced abortion and what is reasonable regarding other procedures (inserting an IUD) or taking a pleasure trip rather than consoling your wife.

Of the twenty-three CPC cases, only one refers to a U.S. government document (trauma coding = 4) that is the USCIS Asylum Adjudicator’s Manual [

69]. In the Ninth Circuit case

Ming Dai v. Sessions, 884 F.3d 858, the Court cited the USCIS Asylum Adjudicator’s Manual section on “Points to Keep in Mind When Conducting a Non-Adversarial Interview” that stated:

If the interviewee is a survivor of severe trauma (such as a battered spouse), he or she may feel especially threatened during the interview. As it is not always easy to determine who is a survivor, officers should be sensitive to the fact that every interviewee is potentially a survivor of trauma.

4.4. Rape

Of the fifty-one rape cases, seven reference the term trauma in the context of precedent cases (trauma coding = 1). Unlike FGM and CPC cases that tend to coalesce around a single precedent case, none of the seven rape cases cite the same case. Only one case, Longwe v. Keisler, 251 Fed. Appx. 718, from the Second Circuit, references a case that substantively deals with both rape and trauma, Fiadjoe v. AG, 411 F.3d 135, a Third Circuit case which is listed in the table above. This case cites INS Guidelines that explains how “trauma caused by sexual abuse may influence ability to present testimony.” In Longwe, the Second Circuit remanded the case and admonished the lower courts because:

the fact that Longwe failed to provide a specific date for her alleged rape did not undermine her credibility. Although the record reflects that Longwe's testimony regarding her alleged rape was minimal, there was nothing in the record to support the IJ's [immigration judge] speculation that "one normally doesn't forget" the date of such a "traumatic event."

One case from the Third Circuit, Dia v. Ashcroft, 353 F.3d 228, references a case that is about rape in the context of repression of traumatic memory. The Court referenced a case from its own Circuit to explain partial memory recall when it stated that:

Another barrier to understanding the demeanor of petitioners who have experienced trauma is the likely repression of traumatic memories. Such repression only adds to the difficulty of answering questions. Their "detachment when recounting tragic events, sometimes perceived as an indication of fabrication, may reflect psychological mechanisms employed to cope with past traumatic experiences, rather than duplicity [

70].

Both of these cases were remanded to the BIA.

The remaining five cases reference other cases that take up the subject of trauma but not rape as a form of harm. Two were granted or remanded:

Rusak v. Holder, 734 F.3d 894 and

Katyal v. Gonzales, 204 Fed. Appx. 661, both Ninth Circuit cases; three were denied:

Olmos-Colaj v. Sessions, 886 F.3d 168,

Alvizuriz-Lorenzo v. United States AG, 791 Fed. Appx 70, and

Jalloh v. Gonzales, 498 F.3d 148 a First, Eleventh, and Ninth Circuit case, respectively. In

Rusak v. Holder, 734 F.3d 894, the petitioner’s mother had been raped when Rusak was a child. The Ninth Circuit referenced a case from its own Court about children that stated that “As Hernandez-Ortiz held, "a child's reaction to injuries to his family is different from an adult's. The child is part of the family, the wound to the family is personal, the trauma apt to be lasting" [

71]. In

Katyal v. Gonzales, 204 Fed. Appx. 661, the petitioner was threatened with rape and her mother was raped. In this case, the Ninth Circuit referenced a case from its own Circuit to support the position that the fear of persecution can be traumatic even if more severe harm came to other family members when it stated that “emotional and psychological trauma, as well as harm to family members, can rise to the level of persecution” [

72]. In

Katyal v. Gonzales, 204 Fed. Appx. 661, the Court remanded the case to the BIA as it disagreed with the BIA finding that Katal’s experiences did not rise to the level of persecution.

Katyal's father was arrested and beaten severely on two occasions, one of which resulted in a two-week hospitalization. In addition, during the arrest of Katyal and her mother, the police sexually harassed Katyal, raped her mother, and threatened Katyal herself with rape. Because the cumulative effects of the harm rise to the level of persecution, we conclude that substantial evidence does not support the BIA's finding.

The Court cited

Mashiri v. Ashcroft again finding that “emotional and psychological trauma, as well as harm to family members, can rise to the level of persecution” [

73].

Three cases were denied. In the First Circuit case

Olmos-Colaj v. Sessions, 886 F.3d 168 the immigration judge denied the case because the petitioners did not meet the threshold of war-time trauma in Guatemala as the petitioners in a case from the same Circuit had done, even though Olmos-Colaj had relatives who were raped during the civil war when they were children because the harm had not been done to them. [

74] In

Alvizuriz-Lorenzo v. United States AG, 791 Fed. Appx. 70 and

Jalloh v. Gonzales, 498 F.3d 148, the Eleventh and Second Circuit, respectively, referenced an Eighth Circuit case and a BIA case to show how part of determining persecution was “evidence of psychological trauma resulting from the harm" [

75,

76].

Of the fifty-one rape cases, thirty-nine reference the term trauma when discussing psychological trauma (trauma coding = 2). Twenty-one were denied on appeal. Psychological trauma was referenced in the context of medical evaluations and reports, issues of credibility and memory recall, and the rape itself as a form of trauma. It is common for medical experts to testify in immigration court and submit medical affidavits that document asylum seekers’ physical and psychological health. Of the cases examined in this study, there were more of these for petitioners with a rape claim than any other type of harm. In several cases the petitioner was diagnosed with PTSD: Ixcuna-Garcia v. Garland, 25 F.4th 38, Mukamusoni v. Ashcroft, 390 F.3d 110, and Zeru v. Gonzales, 503 F.3d 59, all First Circuit cases, Mikhail v. Ashcroft, 78 Fed. Appx. 187, a Third Circuit case, Ilunga v. Holder, 777 F.3d 199 and Gandziami-Mickhou v. Gonzales, 445 F.3d 351, both Fourth Circuit cases, Mansare v. Holder, 383 Fed. Appx. 522, a Sixth Circuit case, Angoucheva v. INS, 106 F.3d 781, a Seventh Circuit case, and Morgan v. Mukasey, 529 F.3d 1202, a Ninth Circuit case.

In addition to a PTSD diagnosis, medical professionals routinely documented trauma as a reason why applicants did not file within the one-year deadline and omitted rape and sexual assault in the application materials, as well as the inconsistencies in their testimony. In Ixcuna-Garcia v. Garland, a clinical nurse explained that “past trauma prevented Ixcuna-Garcia from speaking about her history of persecution in Guatemala, particularly her rape, and from seeking assistance in applying for asylum within the first year of her entering the United States.” In Mukamusoni v. Ashcroft, 390 F.3d 110, Mukamusoni was documented as having a “restricted range of emotion, which is typical of trauma victims.” When describing the flashbacks that Natasha Angoucheva experienced after being assaulted during an interrogation in Bulgaria, her social worker described how “the smell of cigarette smoke, which reminds Angoucheva of Major Beltchev, can cause a flashback, and that Angoucheva will then experience the same numbness in her hands and feet that she experienced in the days following the assault.” The social worker emphasized that “it would be nearly impossible [for someone] to fake the symptoms which [Angoucheva] has described, in the manner in which she seems to describe them, with emotion and detail" in the case Angoucheva v. INS, 106 F.3d 781. Many reports, such as that submitted by a psychologist in the Eleventh Circuit case Mbi v. United States AG, 348 Fed. Appx. 486, indicated that the petitioner’s “psychological symptoms were "consistent with those commonly found in survivors of trauma, and in particular, survivors of persecution and torture."

Memory and recall were also issues that were raised in appeals for applicants with a rape claim. Some petitioners, such as Hermase Amicy, in the First Circuit case Amicy v. Gonzales, 133 Fed. Appx. 745, could not remember the assault and “claimed that her inability to remember the events surrounding her persecution was the result of significant psychological trauma” and the case was denied. Others, like, Essa Kabba, in the Tenth Circuit case Kabba v. Mukasey, 530 F.3d 1239, “did not always know the exact dates of certain events, [and as the immigration judged noted] Kabba's trauma and his limited education explained the lack of precision in the testimony.” In the Fifth Circuit case, Lopez v. Garland, 852 Fed. Appx. 758, Morales Lopez was repeatedly raped in front of her family by members of a gang that later killed her husband. The immigration judge quoted her psychological assessment that stated “[Morales Lopez] may have difficulty accessing specific details of the trauma she has suffered due to her [post-traumatic stress disorder] diagnosis. These symptoms substantiate rather than undermine, the credibility of her account of traumatic experience."

Other petitioners had partial memory of their rape that led to inconsistent testimony. In the Ninth Circuit case Munyuh v. Barr, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 6377, there was a discrepancy between Munyuh’s declaration and oral testimony about the distance a police truck had travelled before it broke down and she was able to escape from the officers who had had “brutally attacked, beaten multiple times, [and] raped [the petitioner] within a span of less than about 24 hours.” Her counsel argued that “It is reasonable and plausible that the trauma caused by multiple physical and sexual assaults would impair Ms. Munyuh's focus at the time on peripheral matters and therefore on her memory of those matters. Her counsel argued that "considering the harm and trauma that [she] suffered, it w[ould] be highly unlikely that [she] would remember precisely everything that happened to her."

In the Third Circuit case Plumbay v. AG of the United States, 213 Fed. Appx. 144, the Court acknowledged that Plumbay’s inconsistent documents and testimony about whether she was raped during an attempted abduction “resulted primarily from her continuing discomfort discussing the attack” and that it is plausible that the inconsistencies “can be explained by trauma and confusion.” However, the Court acknowledged that it is also plausible that the inconsistencies were instead “the result of fabrication” and ultimately denied the case. In Zeru v. Gonzales, 503 F.3d 59, the First Circuit found the inconsistencies incredible. In the lower court’s ruling, the immigration judge “pointed out that Zeru claimed on different occasions to have been raped once, twice, or three times.” Even though the psychological report indicated that “what can sometimes happen with trauma patients is that they may dissociate" and that their memories "may be repressed" the judge responded with “it would not be unusual for a victim of trauma to confuse dates or sequences of events, but it would be very unusual . . . to simply forget that an event occurred." Yet the medical community often argues that in fact it is quite common to have no memory or partial memory of the event itself.

In other cases, such as

Slyusar v. Holder, 740 F.3d 1068, the Sixth Circuit reprimanded laws that punish asylum seekers who cannot recall details, such as the REAL ID Act, citing a Ninth Circuit case that dealt with this issue by stating “as the Ren Court recognized, "victims of abuse often confuse the details of particular incidents, including the time or dates of particular assaults and which specific actions occurred on which specific occasion; thus, the ability to recall precise dates of events years after they happen is an extremely poor test of how truthful a witness's substantive account is" [

77]. In the Eighth Circuit case

Redd v. Mukasey, 535 F.3d 838, the petitioner testified that he was home the night his wife was raped while his wife testified that he was not. Redd explained this discrepancy “by arguing that his wife's testimony was confusing and incomprehensible because of the trauma from the rape, and, thus, the IJ [immigration judge] should not have considered her testimony in determining Redd's credibility.”

Other aspects of credibility include affect and how asylum seekers tell their stories of persecution. In the Fourth Circuit case Ilunga v. Holder, 777 F.3d 199, the Court recognized that Ilunga was “forced to revisit the trauma” of her rapes while being detained and that emotional retelling such as crying made her more - not less - credible as “the ability to testify in a cool and collected manner about an experience of torture would arguably raise greater credibility concerns” due to from “traumatic memory.” For some petitioners, such as Renee Labib Mikhail, in the Third Circuit case Mikhail v. Ashcroft, 78 Fed. Appx. 187, a “detached emotional state” and “gaps in her recollection” compounded the Court’s rejection of her claim as she reported some instances of persecution to the Egyptian police such as the “burning of her car” but not “the more serious incidents of assault and rape.” Moreover, having not included the rape as part of her application led the Court to rule against her. In the Eight Circuit case, Mambwe v. Holder, 572 F.3d 540, the petitioner did not “seek medical treatment for symptoms of psychological trauma” leading the Court to believe the sexual assaults were not severe enough to merit humanitarian relief even though she testified that she was raped in a refugee camp. In the Third Circuit case Siauw Lan Tjin v. AG of the United States, 191 Fed. Appx. 144, the immigration judge noted that the petitioner “had not provided any medical evidence to corroborate her testimony that she suffered and continues to suffer from mental trauma, even though that evidence could have reasonably been obtained from a psychologist.”

The language of trauma is also used to refer to the rape itself and the emotional toll it takes on those who have been assaulted. In the Eleventh Circuit case Liana Tan v. United States AG, 446 F.3d 1369, Tan was sexually assaulted and her friend was raped (the transcript does not detail why different language was used) and she “suffered from nightmares and emotional trauma as a result of the event.” The immigration judge denied the case and reasoned that if Tan could not file the application within the one year due to the “trauma from the sexual assault” she should not have been able to marry during that same timeframe. In the Ninth Circuit case Zhu v. Mukasey, 537 F.3d 1034, the psychiatrist's evaluation stated that she “re-experience[ed] the trauma of being raped” and Zhu testified that she “finds it difficult to maintain normal sexual relationships with men because of her rape.” The language of trauma included cases of an attempted rape, such as Weiwei Chen v. Holder, 549 Fed. Appx. 567, a Seventh Circuit case. Here, the Court remanded the case to the BIA because “the Board incorrectly discounted the trauma of a sexual assault by reasoning that, because Chen fought off her assailant before he inflicted more harm, she was merely harassed.” In a Ninth Circuit case Marenco-Hernandez v. Garland, 2021 U.S. App. LEXIS 20669, the petitioner who after being raped by members of a gang was forced to carry a pregnancy to term by doctors who sedated her for several months causing “lasting mental trauma.”

Of the fifty-one rape cases, seven reference the term trauma when discussing physical trauma (trauma coding = 3). Only one of these cases, Munyuh v. Barr, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 6377, a Ninth Circuit case that was discussed earlier, references physical trauma related to the rape of the petitioner. Three cases, Lleshi v. Holder, 460 Fed. Appx. 520 and Marouf v. Lynch, 811 F.3d 174, both Sixth Circuit cases, and Bobo v. Holder, 344 Fed. Appx. 269, a Seventh Circuit case, reference physical trauma in the context of a family member (husband or brother) experiencing head trauma or trauma related to a deviated septum because of physical attacks by police or security officers. Two cases, Nikolajuk v. Holder, 527 Fed. Appx. 439 and Yakovenko v. Gonzales, 477 F.3d 631, a Sixth and Eighth Circuit case, respectively, detail petitioners’ experiences with medical reports from hospitals that documented physical trauma such as kidney disease and routine medical issues. In Narayan v. Gonzales, 220 Fed. Appx. 691, the Ninth Circuit referenced physical trauma related to Narayan’s children’s illnesses. All cases but one, Marouf v. Lynch, 811 F.3d 174, a Sixth Circuit case, were denied.

Of the fifty-one rape cases, three cases referenced trauma in policies and reports such as INS Guidelines, a Human Rights Report, a United Nations Report, and a report on Rape Trauma Syndrome (trauma coding = 4). In a Third Circuit case Fiadjoe v. AG, 411 F.3d 135, The INS Guidelines entitled "Consideration for Asylum Officers Adjudicating Asylum Claims from Women" were referenced that stated that:

Women who have been subject to domestic or sexual abuse may be psychologically traumatized. Trauma can be suffered by any applicant, regardless, of gender, and may have a significant impact on the ability to present testimony. The demeanor of traumatized applicants can vary. They may appear numb or show emotional passivity when recounting past events of mistreatment. Some applicants may give matter-of-fact recitations of serious instances of mistreatment. Trauma may also cause memory loss or distortion, and may cause other applicants to block certain experiences from their minds in order not to relive their horror by the retelling. [

78]

The intention of the INS Guidelines was to help adjudicators understand how trauma can explain behaviors that may make them seem noncredible. In a Ninth Circuit case

Kaur v. Wilkinson, 986 F.3d 1216, the UNHCR, Handbook for the Protection of Women and Girls was referenced that stated that "sexual and gender-based violence" of all forms leads to "emotional and psychological trauma." [

79] In

Lopez-Galarza v. INS, 99 F.3d 954, also a Ninth Circuit case, the Court acknowledges trauma from rape and references a journal article about Rape Trauma Syndrome [

80]. In all three of these cases, the use of these documents and reports links to the case at hand to emphasize the trauma of the petitioner. All three cases were granted or remanded.