Submitted:

24 November 2023

Posted:

27 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Developing a Novel Approach for Participatory Design of Urban Green Space

2.1.1. Guiding Principles to Develop the Approach

2.1.2. Suggested Process Steps of the Approach

2.2. Testing the Developed Approach in Two Neighborhoods of Maastricht

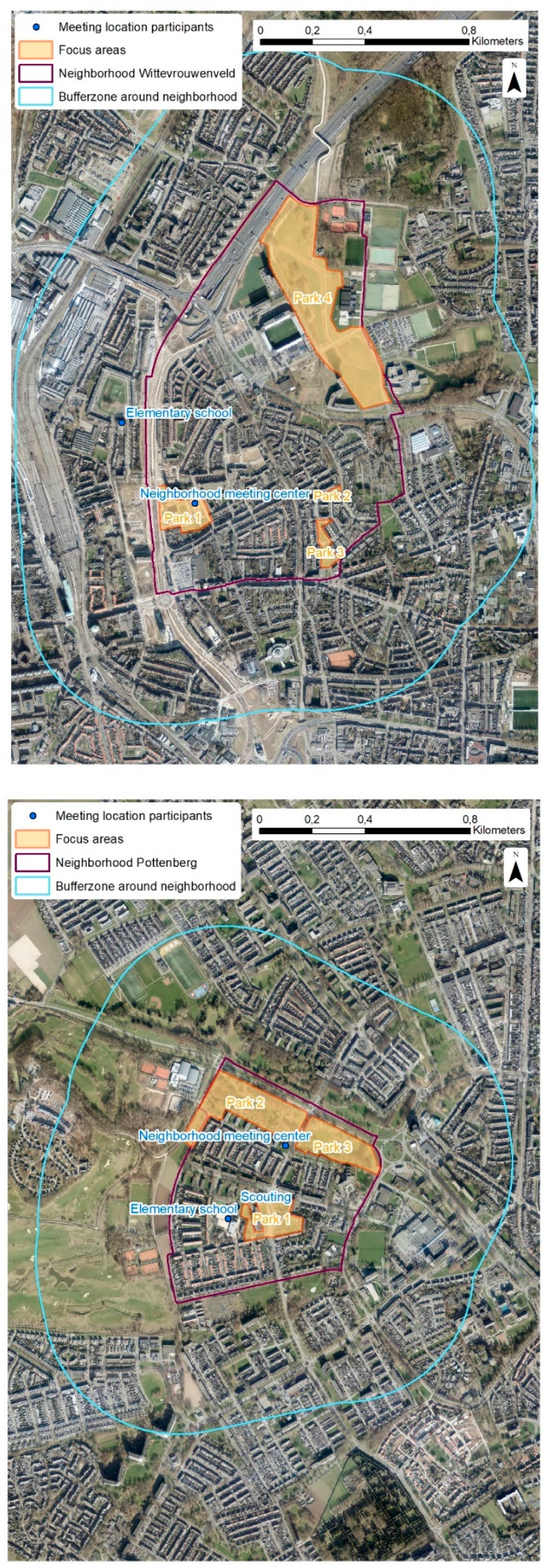

2.2.1. Selecting Neighborhoods, Focus Areas and Participants

-

Socio-economic status

- -

- % Households below the social minimum1

- -

- % Households with a social assistance benefit (allowance)1

- -

- % Households that has difficulty getting by (making ends meet, self-assessed)2

- -

- Average income per resident (value inverted for scoring)1

-

Health

- -

- % At risk of anxiety disorder2

- -

- % Good perceived health (self-assessed, value inverted for scoring)2

- -

- % Socially excluded2

- -

- % Lonely2

- -

- % Overweight2

- -

- % Meets movement norm (value inverted for scoring)2

-

Urban Green Space

- -

- Green index3

- -

- Quantity average reachable green3

- -

- % Green under management of municipality3

2.1.2. Implementation of the Developed Approach in Two Neighborhoods of Maastricht

2.1.3. Development and Application of an Evaluation Framework

3. Results

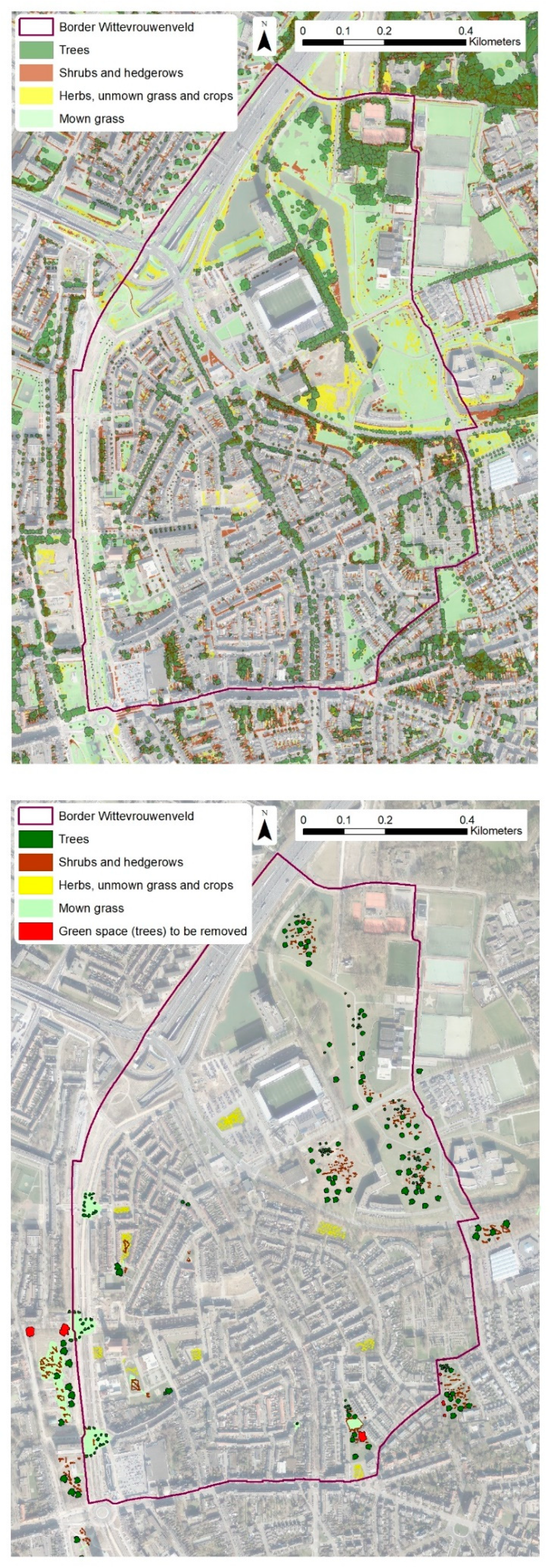

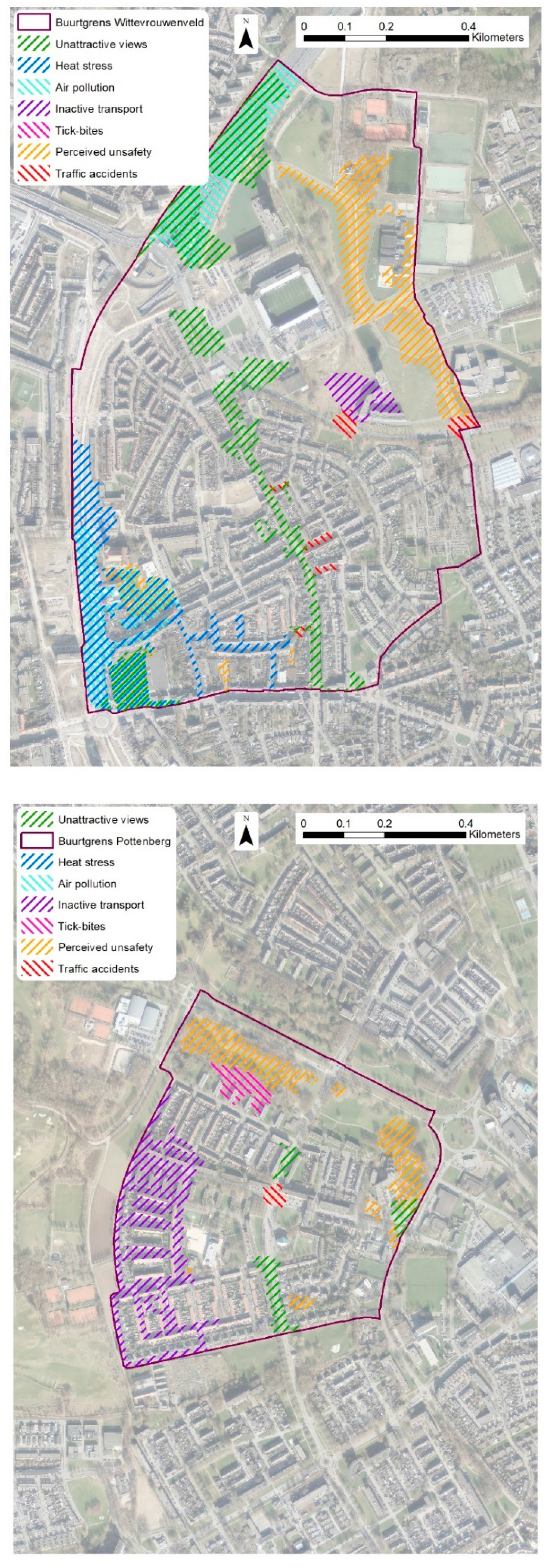

3.1. Implementation of the Developed Approach in Two Neighborhoods of Maastricht

3.2. Evaluation: Strengths and Weaknesses of the Developed Approach

3.2.1. Strengths of the Developed Approach

3.2.2. Weaknesses of the Developed Approach

4. Discussion

4.1. Major Strengths and Weaknesses

4.2. Recommendations for Improvement

4.3. Recommendations for Further Research

4.4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abhijith, K., Kumar, P., Gallagher, J., McNabola, A., Baldauf, R., Pilla, F., . . . Pulvirenti, B. (2017). Air pollution abatement performances of green infrastructure in open road and built-up street canyon environments–A review. Atmospheric Environment, 162, 71-86.

- Al-Kodmany, K. (2001). Bridging the gap between technical and local knowledge: Tools for promoting community-based planning and design. Journal of Architectural and Planning research, 110-130.

- Anderson, J. O., Thundiyil, J. G., & Stolbach, A. (2012). Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. Journal of medical toxicology, 8(2), 166-175.

- Bancroft, C., Joshi, S., Rundle, A., Hutson, M., Chong, C., Weiss, C. C., . . . Lovasi, G. (2015). Association of proximity and density of parks and objectively measured physical activity in the United States: A systematic review. Social science & medicine, 138, 22-30.

- Beeldmateriaal Nederland. (2018). Data. Retrieved from https://www.beeldmateriaal.nl/data.

- Bodnaruk, E., Kroll, C., Yang, Y., Hirabayashi, S., Nowak, D., & Endreny, T. (2017). Where to plant urban trees? A spatially explicit methodology to explore ecosystem service tradeoffs. Landscape and Urban Planning, 157, 457-467.

- Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L. M., Knight, T. M., & Pullin, A. S. (2010). A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Brown, G., & Fagerholm, N. (2015). Empirical PPGIS/PGIS mapping of ecosystem services: A review and evaluation. Ecosystem Services, 13, 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Brown, G., Rhodes, J., & Dade, M. (2018). An evaluation of participatory mapping methods to assess urban park benefits. Landscape and Urban Planning, 178, 18-31.

- Canedoli, C., Bullock, C., Collier, M. J., Joyce, D., & Padoa-Schioppa, E. (2017). Public participatory mapping of cultural ecosystem services: Citizen perception and park management in the Parco Nord of Milan (Italy). Sustainability, 9(6), 891.

- CBS. (2018a). Bevolking; ontwikkeling in gemeenten met 100 000 of meer inwoners. Retrieved from https://statline.cbs.nl.

- de Vries, S., van Dillen, S. M., Groenewegen, P. P., & Spreeuwenberg, P. (2013). Streetscape greenery and health: stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc Sci Med, 94, 26-33. [CrossRef]

- Dougill, A. J., Fraser, E., Holden, J., Hubacek, K., Prell, C., Reed, M., . . . Stringer, L. (2006). Learning from doing participatory rural research: lessons from the Peak District National Park. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 57(2), 259-275.

- Gascon, M., Triguero-Mas, M., Martínez, D., Dadvand, P., Rojas-Rueda, D., Plasència, A., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2016). Residential green spaces and mortality: A systematic review. Environment International, 86, 60-67. [CrossRef]

- Gehrels, H., Meulen, S. v. d., Schasfoort, F., Bosch, P., Brolsma, R., Dinther, D. v., . . . Massop, H. T. L. (2016). Designing green and blue infrastructure to support healthy urban living. Retrieved from http://edepot.wur.nl/384206.

- GGD Zuid Limburg (2018). Health Monitor Adults and Elderly 2016. Retrieved from https://www.gezondheidsatlaszl.nl.

- Gonzalez-Ollauri, A., & Mickovski, S. B. (2017). Providing ecosystem services in a challenging environment by dealing with bundles, trade-offs, and synergies. Ecosystem Services, 28, 261-263. [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., De Vries, S., & Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 207-228. [CrossRef]

- Hassen, N., & Kaufman, P. (2016). Examining the role of urban street design in enhancing community engagement: A literature review. Health & Place, 41, 119-132.

- Honold, J., Lakes, T., Beyer, R., & van der Meer, E. (2015). Restoration in Urban Spaces: Nature Views From Home, Greenways, and Public Parks. Environment and Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Huck, J. J., Whyatt, J. D., & Coulton, P. (2014). Spraycan: A PPGIS for capturing imprecise notions of place. Applied Geography, 55, 229-237. [CrossRef]

- James, P., Banay, R. F., Hart, J. E., & Laden, F. (2015). A Review of the Health Benefits of Greenness. Current Epidemiology Reports, 2(2), 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R., Gray, S., Zellner, M., Glynn, P. D., Voinov, A., Hedelin, B., . . . Hubacek, K. (2018). Twelve questions for the participatory modeling community. Earth's Future, 6(8), 1046-1057.

- Kabisch, N., van den Bosch, M., & Lafortezza, R. (2017). The health benefits of nature-based solutions to urbanization challenges for children and the elderly – A systematic review. Environmental research, 159, 362-373. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M. C., Fluehr, J. M., McKeon, T., & Branas, C. C. (2018). Urban green space and its impact on human health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 445.

- Lee, A. C. K., & Maheswaran, R. (2011). The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. Journal of Public Health, 33(2), 212-222. [CrossRef]

- Literat, I. (2013). Participatory mapping with urban youth: The visual elicitation of socio-spatial research data. Learning, Media and Technology, 38(2), 198-216.

- Lovell, R., Depledge, M., & Maxwell, S. (2018). Health and the natural environment: A review of evidence, policy, practice and opportunities for the future.

- Maes, J., Teller, A., & Erhard, M. (2013). Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services. An Analytical Framework for Ecosystem Assessments Under Action 5 of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020.

- Mendoza, G. A., & Prabhu, R. (2005). Combining participatory modeling and multi-criteria analysis for community-based forest management. Forest Ecology and Management, 207(1), 145-156. [CrossRef]

- Møller, M. S., Olafsson, A. S., Vierikko, K., Sehested, K., Elands, B., Buijs, A., & van den Bosch, C. K. (2019). Participation through place-based e-tools: A valuable resource for urban green infrastructure governance? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 40, 245-253. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M. V., Doick, K. J., Handley, P., & Peace, A. (2016). The impact of greenspace size on the extent of local nocturnal air temperature cooling in London. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 16, 160-169.

- Oosterbroek, B., de Kraker, J., Huynen, M. M. T. E., Martens, P., & Verhoeven, K. (2023). Assessment of green space benefits and burdens for urban health with spatial modeling. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 86, 128023. [CrossRef]

- Pánek, J., Pászto, V., & Šimáček, P. (2017). Spatial and temporal comparison of safety perception in urban spaces. Case study of Olomouc, Opava and Jihlava. Paper presented at the Proceedings of GIS Ostrava.

- Pelucchi, C., Negri, E., Gallus, S., Boffetta, P., Tramacere, I., & La Vecchia, C. (2009). Long-term particulate matter exposure and mortality: a review of European epidemiological studies. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 1-8.

- Ravera, F., Hubacek, K., Reed, M., & Tarrasón, D. (2011). Learning from experiences in adaptive action research: a critical comparison of two case studies applying participatory scenario development and modelling approaches. Environmental Policy and Governance, 21(6), 433-453.

- Reed, M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation, 141(10), 2417-2431. [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A., Browning, M. H., Lee, K., & Shin, S. (2018). Access to urban green space in cities of the Global South: A systematic literature review. Urban Science, 2(3), 67.

- Roman, L. A., Conway, T. M., Eisenman, T. S., Koeser, A. K., Barona, C. O., Locke, D. H., . . . Vogt, J. (2021). Beyond ‘trees are good’: Disservices, management costs, and tradeoffs in urban forestry. AMBIO, 50(3), 615-630.

- Saadallah, D. M. (2020). Utilizing participatory mapping and PPGIS to examine the activities of local communities. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 59(1), 263-274. [CrossRef]

- Sprong, H., Azagi, T., Hoornstra, D., Nijhof, A. M., Knorr, S., Baarsma, M. E., & Hovius, J. W. (2018). Control of Lyme borreliosis and other Ixodes ricinus-borne diseases. Parasites & Vectors, 11(1), 1-16.

- Sterling, E. J., Zellner, M., Jenni, K. E., Leong, K., Glynn, P. D., BenDor, T. K., . . . Jordan, R. (2019). Try, try again: Lessons learned from success and failure in participatory modeling. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 7.

- Tang, Z., & Liu, T. (2016). Evaluating Internet-based public participation GIS (PPGIS) and volunteered geographic information (VGI) in environmental planning and management. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 59(6), 1073-1090.

- Theeuwes, N. E., Steeneveld, G. J., Ronda, R. J., & Holtslag, A. A. (2017). A diagnostic equation for the daily maximum urban heat island effect for cities in northwestern Europe. International Journal of Climatology, 37(1), 443-454.

- Usón, T. J., Klonner, C., & Höfle, B. (2016). Using participatory geographic approaches for urban flood risk in Santiago de Chile: Insights from a governance analysis. Environmental Science & Policy, 66, 62-72.

- Van den Berg, M., Wendel-Vos, W., Van Poppel, M., Kemper, H., Van Mechelen, W., & Maas, J. (2015). Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14(4), 806-816. [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, M., & Sang, Å. O. (2017). Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health–A systematic review of reviews. Environmental research, 158, 373-384.

- van der Jagt, A. P., Elands, B. H., Ambrose-Oji, B., Gerőházi, É., Møller, M. S., & Buizer, M. (2017). Participatory governance of urban green spaces: trends and practices in the EU. NA, 28(3).

- Vukomanovic, J., Skrip, M. M., & Meentemeyer, R. K. (2019). Making it spatial makes it personal: engaging stakeholders with geospatial participatory modeling. Land, 8(2), 38.

- Warburton, D. E., Nicol, C. W., & Bredin, S. S. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Cmaj, 174(6), 801-809.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2016). Urban green spaces and health. Retrieved from Copenhagen: www.euro.who.int.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2017). Urban Green Space Interventions and Health: a Review of impacts and effectiveness. Retrieved from Copenhagen: www.euro.who.int.

- Wolf, K. L. (2006). Urban trees and traffic safety: Considering the US roadside policy and crash data. Arboriculture and Urban Forestry. 32 (4): 170-179., 32(4), 170-179.

- Wong, K. V., Paddon, A., & Jimenez, A. (2013). Review of world urban heat islands: Many linked to increased mortality. Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 135(2).

- Zhou, X., Li, D., & Larsen, L. (2016). Using web-based participatory mapping to investigate children’s perceptions and the spatial distribution of outdoor play places. Environment and Behavior, 48(7), 859-884.

| Step | Name | Instruction for facilitator of the approach | Relates to guiding principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Choose a set of health effects to assess and decide how to assess each health effect | Choose a wide enough spectrum of health effects. Determine which health effects are best assessed by the participants and which best by an available expert method. | 1, 2 (and 8) |

| 2 | Orienting neighborhood walk | Organize a walk through the area of interest and visit all UGS of significance. | 3, (8) |

| 3 | First design session | Construct maps by drawing lines around the border of the areas of interest. Indicate - within the areas of interest - where participants can or cannot change the current situation on the map. | 3, (8) |

| 4 | Pre-processing participant Urban Green Space designs for expert assessment | Process the maps such that they are ready for expert assessment of the health benefits selected during step 1. Consider generalizing or extrapolating designs to make effects more clear to participants at step 6. | 4, (8) |

| 5 | Expert assessment for both current UGS and UGS design situation | Perform expert assessment of the initial (participatory) UGS designs. Process the results of the expert assessment such that the difference between current UGS situation and initial design UGS situation is clearly visible for participants, for example only display hotspots. | 5, (8) |

| 6 | Feedback meeting with participants | Present the digitized initial UGS designs, and explain the health effects. Finally, give the participants the opportunity to make adjustments to their UGS design after being informed about the expert-based health benefits and burdens (‘adjusted UGS design’). | 5, 6, (8) |

| 7 | Determine participant self-assessed score on a selection of health effects | Conduct survey, interviews or other method to determine UGS usage scores for both the current UGS situation and the adjusted UGS design that includes possible adjustments made by the participants. | 7, 4, (8) |

| - | Possibility for iteration of steps 4 to 7 | Optional re-assessment of the adjusted UGS designs by expert and participants by repeating step 4 to 7. | 6, (8) |

| 8 | Report results to local decision makers | Assessment of the final UGS designs by experts. Process the results of the expert assessment such that the difference between the current situation and the adjusted design is understandable for local decision makers. Facilitate an interactive session with the local government. | 8 |

| Neighborhood of most participants* | Group | Number of participants | Average age (year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pottenberg | Elementary school | 9 | 11 |

| Pottenberg | Scouting | 10 | 7 |

| Pottenberg | Seniors social meeting group | 12 | 80 |

| Wittevrouwenveld | Elementary school | 6 | 11 |

| Wittevrouwenveld | Seniors social meeting group | 5 | 55 |

| * In some cases, participants lived around these neighborhoods | |||

| Urban Green Space benefit | Indicator | Type of assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting opportunities increase | Area visiting frequency score 1 - 5 (never - daily) for use as meeting place | Resident self-assessment |

| Stress reduction opportunities increase | Area visiting frequency score 1 - 5 (never - daily) for use to relax | Resident self-assessment |

| Leisure-based physical activity increase | Area visiting frequency score 1 - 5 (never - daily) for use to sport, play or go for a stroll | Resident self-assessment |

| Unattractive views decrease | Unattractive views score (decrease) | Computer modeled |

| Heat stress decrease | Temperature (decrease) | Computer modeled |

| Air pollution decrease | Air pollutant concentration (decrease) | Computer modeled |

| Active transport increase | Walking distance (increase) | Computer modeled |

| Urban Green Space burden | ||

| Air pollution increase | Air pollutant concentration (increase) | Computer modeled |

| Perceived unsafety increase | Perceived social unsafety score (increase) | Computer modeled |

| Tick-bite increase | Tick-bite chance (increase) | Computer modeled |

| Traffic accidents increase | Pedestrian invisibility (increase) | Computer modeled |

| Category | Criterion | Adopted or adapted from |

|---|---|---|

| Data quality for participants | Quality data (e.g. correct location and label) | (Tang & Liu, 2016) |

| Complete / sufficient spatial data | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015; Huck et al., 2014) | |

| Unbiased selection of benefits for mapping | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Data quality by participants | Data allow people to have their views included and well-represented | (Huck et al., 2014; McLain et al., 2013) |

| Participation equality: inclusion of or representativeness of social groups based on study design (e.g. due to provision of access) | (Møller et al., 2019) (Huck et al., 2014; Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| User-provided data not artificially forced into discrete points and polygons | (Huck et al., 2014) | |

| Ability to detect, correct or remove inaccurate spatial records | (Fagerholm et al., 2021) | |

| User | Personalized connections to problems | (Vukomanovic et al., 2019) |

| friendliness | Clear communication of expectations and purpose to participants | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) (Brown & Kyttä, 2018) |

| Mapping benefits appropriate to participant knowledge and ability | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Low mapping effort and high data usability | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Combination with other communication techniques (e.g. social media) | (Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| Clear operational definitions for the benefits being mapped and their attributes | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Building or keeping trust is taken into account in the participatory process | (Brown & Kyttä, 2018) | |

| Co-creation and co-design between different participants is facilitated instead of being a barrier in the process | (Brown & Kyttä, 2018) | |

| Approach avoids conflict between participants | (Huck et al., 2014) | |

| Feasibility | Attraction of / motivation for a sufficient amount of participants | (Tang & Liu, 2016) |

| Ability to engage diverse, relevant, and sometimes reluctant stakeholders | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Success of cooperation with other organizations to facilitate the process | (Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| Continuity of support by the hosting organization during full and multiple sessions | (Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| Continuity of user presence and engagement during full and multiple sessions | (Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| Approach is not too costly | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) (Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| Approach is not too time-consuming for participants | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) (Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| Usefulness for decision makers | Integration of data into actual participatory land use planning decision processes | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) |

| Ability to combine spatial with non-spatial data to improve relevance | (Fagerholm et al., 2021) | |

| Standardization and commensurability of results with other measures of value | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Ability to compare mapped results against current situation | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Provides opportunity for trade-off analyses | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) | |

| Compatible with the social and institutional context of land use decision process | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) (Canedoli et al., 2017) | |

| Extent to which mapped attributes can be generalized to be applied to other place and in other contexts, or to produce a representation of a system | (Fagerholm et al., 2021) | |

| Usefulness for participants | Alignment with participant interests or goals | (Tang & Liu, 2016) |

| Stimulates empowerment of participating social groups (e.g. youth) | (Literat, 2013; Zhou et al., 2016) | |

| Increases public awareness of the issue or problem | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) (Tang & Liu, 2016) | |

| Increases trust in local policy making | ||

| Engages people in planning processes leading to decisions that will directly affect their lives. | (Brown & Fagerholm, 2015) |

| Group | Current use | Self-assessed expected use after design | Summary of designed elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly (n=17) |

A few times per month | A few times per week | Flowers, solitary trees, street trees, extra dog walking area, benches, bushes on roundabouts pruned for traffic safety. |

| Children (n=28) |

A few times per year | A few times per month to a few times per week | Climbing trees and play trees, paths, flowers, shielding shrubs, play bushes, hills, flowers, fallen trees, stepping stones. A few trees removed (because of soccer field, social safety, tick habitat) |

| Benefits of UGS (intended*) | Indicator-value of current green2 | Indicator-value after design2 |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting, stress reduction, and physical activity | Use a few times per month1 | Use a few times per week1 |

| Benefits of green (additional*) | ||

| Unattractive views decrease | 87% | 88% |

| Heat stress decrease | 14% (or 0.3 °C) 3 | 19% (or 0.4 °C) 3 |

| Air pollution decrease | 0% | 0% |

| Active transport increase | 2% (10 meter) 4 | 4% (30 meter) 4 |

| Burdens of green (additional*) | ||

| Air pollution increase | 0% | 0% |

| Perceived unsafety increase | 3% | 7% |

| Tick-bite increase | - | - |

| Traffic unsafety increase | 22% | 22% |

| Benefits of UGS (intended*) | Indicator-value of current green2 | Indicator-value after design2 |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting, stress reduction, and physical activity | Use a few times per month1 | Use a few times per month to a few times per week1 |

| Benefits of green (additional*) | ||

| Unattractive views decrease | 94% | 96% |

| Heat stress decrease | - | - |

| Air pollution decrease | - | - |

| Active transport increase | 3% (20 meter) 4 | 7% (50 meter) 4 |

| Burdens of green (additional*) | ||

| Air pollution increase | - | - |

| Perceived unsafety increase | 30% | 38% |

| Tick-bite increase | 100% 5 | 100% (no extra areas) 5 |

| Traffic unsafety increase | 78% | 78% |

| Criteria category | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Data quality for participants |

|

- |

| Data quality by participants |

|

|

|

User friendliness |

|

|

| Feasibility |

|

|

| Usefulness for decision (maker) support |

|

|

| Usefulness for participants (residents) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).