Submitted:

23 November 2023

Posted:

23 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Osteopenia and osteoporosis

2.1. Bone

2.2. Bone remodeling

2.3. Risk factors

| Bone remodeling regulation system |

Description |

|---|---|

| RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway |

|

| Wnt pathway |

|

| Endocrine regulation |

|

| Paracrine regulation |

|

2.4. Epidemiology and etiology of osteoporosis

2.5. Diagnosis

2.6. Therapeutical approaches

| Drug class | Mechanism of action | Adverse effects | Refs. |

| Anti-resorptive drugs | |||

| Non-nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (NNBP) (Etidronate, Clodronate, Tiludronate) | Induction of osteoclast apoptosis by conversion into ATP analogues in the cytoplasm | Atypical femoral fractures, osteonecrosis of the jaw, acid regurgitation hypocalcemia, esophageal ulcers | [92] |

| Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (NBP) (Alendronate, Risedronate, Ibandronate, Neridronate, Pamidronate) |

Inhibition of mevalonate pathway (cholesterol biosynthesis) | Dysphagia, nausea, constipation/diarrhea, gastritis, flatulence | [93] |

| Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (Tamoxifen, Raloxifene, Bazedoxifene, Ospemifene) | Bind to estrogen receptors with an agonistic effect at bone and hepatic level and a partially antagonistic effect at breast and the genitourinary system level | Hot flushes, leg cramps, risk of blood clots and stroke, increased likelihood of developing uterine cancer, blood clots, and menopausal symptoms | [94,95] |

| RANKL inhibitor (Denosumab) | Binding to RANKL leads to osteoclast inactivation and apoptosis | Jaw osteonecrosis, musculoskeletal pain, atypical femoral fracture, gastrointestinal symptoms | [96] |

| Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) (Estrogen) | Bind to estrogen receptors, inducing osteoclast apoptosis | Breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, venous thrombo-embolic disorders | [97] |

| Calcitonin | Inhibit osteoclast function | Vomiting, nausea, inflammation at the injection site, diarrhea, gastrointestinal signs, stomach pain | [98] |

| Cathepsin K inhibitor (Odanacatib and Balicatib)* |

Inhibit osteoclast resorption | Skin adverse experiences | [99,100,101] |

| Bone-forming drugs | |||

| PTH analogs (Teriparatide) |

Bind PTH1R on osteoblasts, increasing bone formation | Dizziness, nausea, headache, leg cramps, osteosarcoma | [102] |

| Human PTH-related protein (PTHrP) (Abaloparatide) |

Bind PTH1R on osteoblasts, increasing bone formation | Gastrointestinal symptoms, site reaction, osteosarcoma, dizziness, myalgia | [103] |

| Dual-actions drugs | |||

| Anti-sclerostin antibody (Romosozumab) | Binds to sclerostin, preventing the inhibition of the Wnt pathway by sclerostin, and reduces bone resorption | Stroke, cardiovascular disorders, myocardial infarction | [104,105] |

| Strontium ranelate (Protelos, Osseor) | Bind to Ca sensing receptors inhibiting osteoclast activity | Cardiovascular risk and non-fatal myocardial infarctions | [106,107,108] |

3. Nutraceuticals

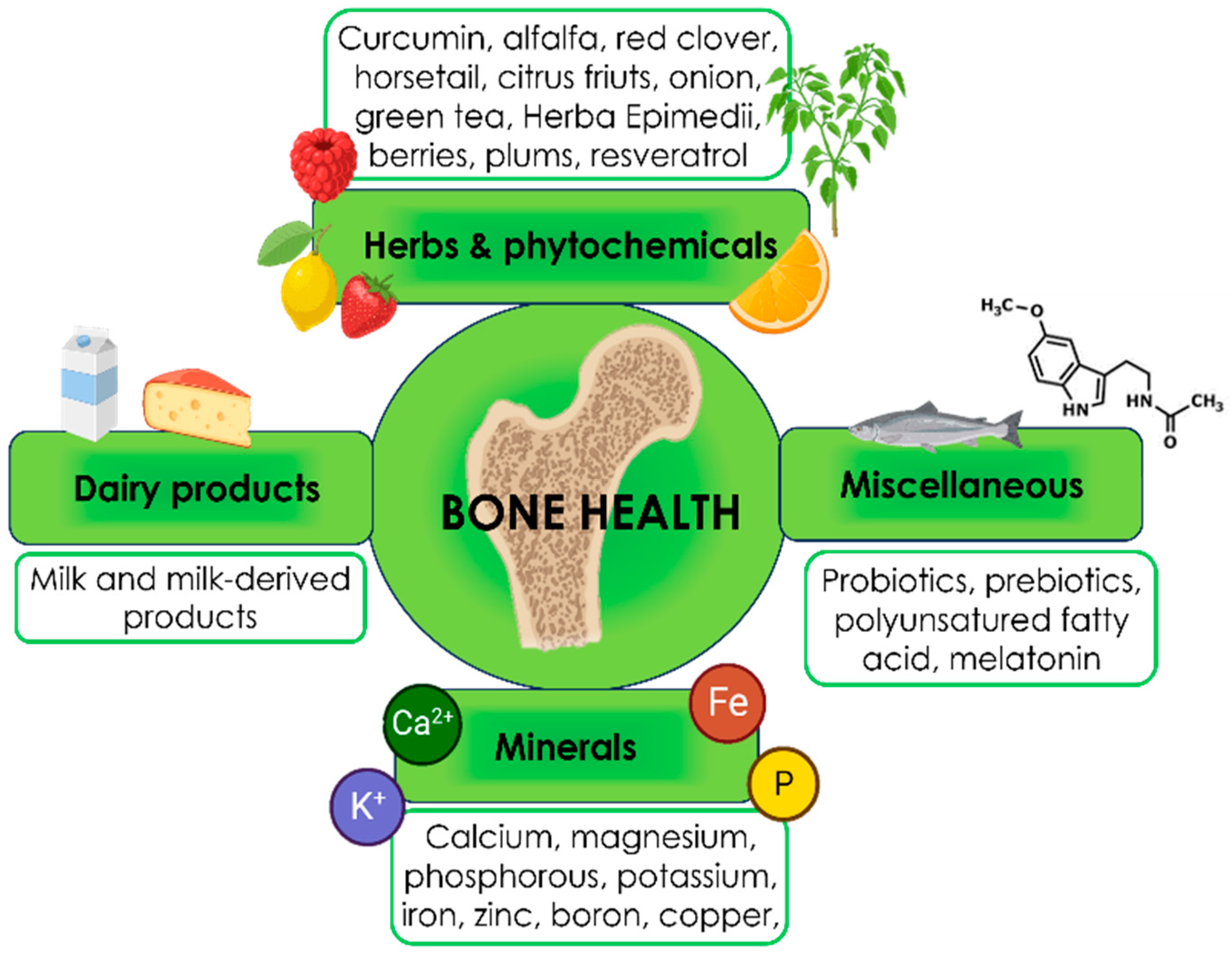

3.1. Nutraceutical for bone health

3.1.1. Minerals

Calcium

Magnesium

Phosphorous

Potassium

Iron

Zinc

Boron

Copper

3.1.2. Herbs & phytochemicals

Curcumin

Alfalfa

Red clover

Horsetail

Citrus fruits

Alliaceae and Brassicaceae

Green tea

Herba Epimedii

Berries

Plums

Resveratrol

3.1.3. Dairy products

3.1.4. Miscellaneous

Probiotics

Prebiotics

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

Melatonin

3.2. Effects on GUT microbiota.

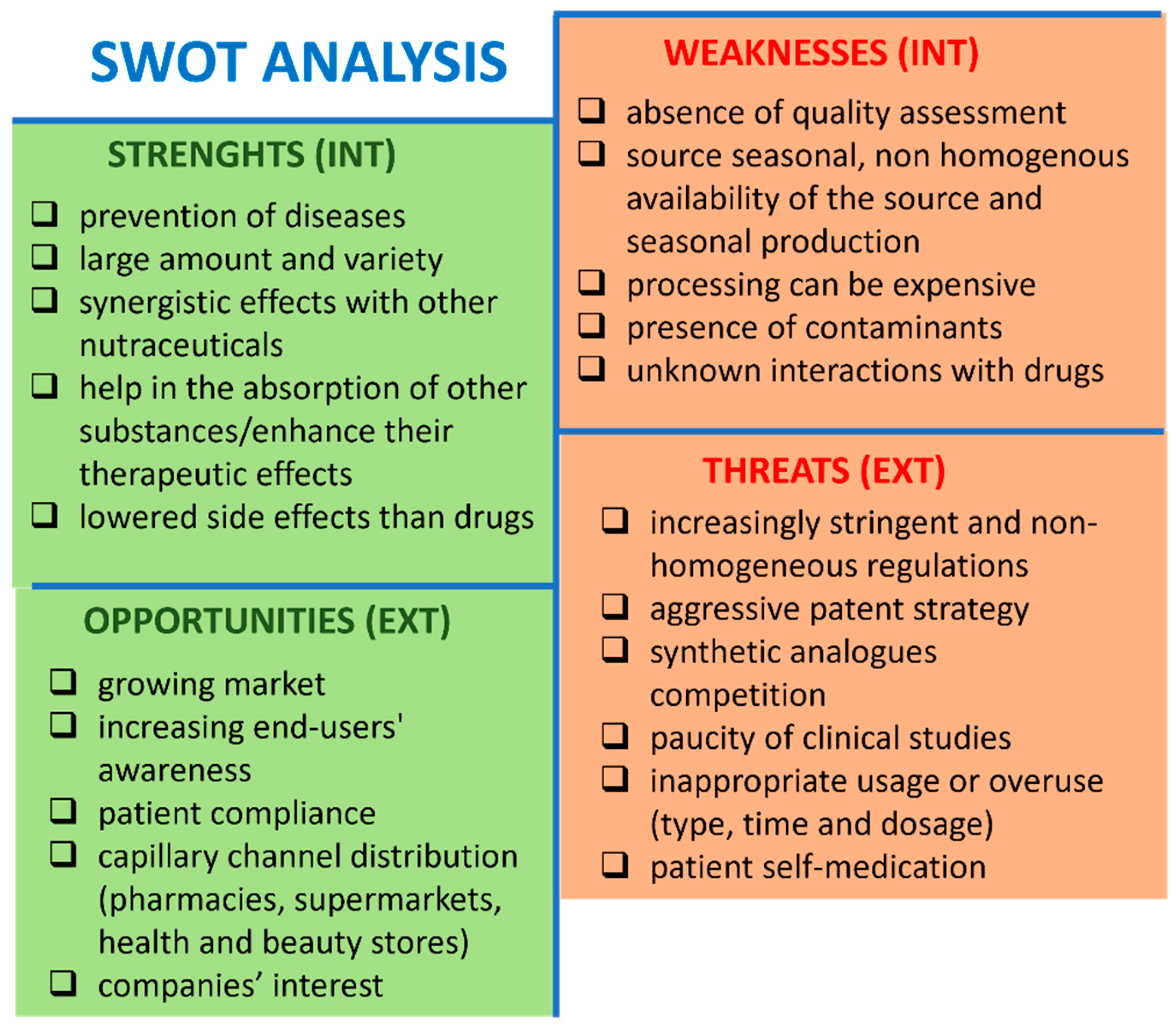

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Weakness

4.3. Opportunities

4.4. Threats

| Area/Country | Regulation | Ref/Link |

| European Union (EU) |

The European Food and Safety Authority (EFSA) is responsible for regulating food legislation and considers food supplements as foods. | EU regulation CE n. 178/2002 |

| The European Commission has established harmonized rules to safeguard consumers against possible health risks for ingredients other than vitamins and minerals. | https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-supplements | |

| New products must meet strict development and quality requirements. Before the products reach the market, EFSA must authorize any health claim, and subsequently, each EU State can decide to set specific approval regulations and/or authorization. However, EFSA does not have any mandate to act against any unsafe products once they are on the market | Directive 2002/46/EC | |

| United States | The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates nutraceuticals differently from “conventional foods” and drugs. In 1994, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) stated that manufacturers must ensure nutraceutical safety and efficacy before market release. It is not mandatory for FDA to approve or register nutraceuticals before producing or selling them. However, nutraceuticals must meet high standards of trial design and patient safety and be reviewed by the Investigational New Drug (IND) application process. FDA is authorized to act against any unsafe product after it reaches the market. |

[213] |

| India | The Food Safety and Standards Act does not assign any specific legal status to nutraceuticals. | Food safety and Standard Act, 2006 No. 34 OF 2006. |

| Australia | Nutraceuticals come under the category of food, and therefore, the national regulations for food are applied. | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) |

| Canada | There are explicit sets of rules for supplements and nutraceuticals that are regulated more closely as a drug than a food category. | [214,215] |

| Latin America | Colombia, Brazil, and Argentina require the registration of a new nutraceutical in the market. In Brazil, animal and/or human clinical studies before product registration are mandatory. Mexico and Chile follow a notification-based approach. |

[213] |

| China and Taiwan | Before product registration, regulators require animal and/or human clinical studies. | [213] |

| Japan | It was the first country to recognize and regulate functional foods through the establishment of Foods for Specified Health Use (FOSHU) in 1991. Later, this evolved into the 2003 Health Promotion Law, which allowed foods with beneficial health activities and meeting FOSHU requirements (including safety and nutritionally appropriate ingredient content) to obtain approval as nutraceutical. Japan has a well-established market in nutraceuticals dating back to the 1980s | [194] |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albrecht, B.M.; Stalling, I.; Foettinger, L.; Recke, C.; Bammann, K. Adherence to Lifestyle Recommendations for Bone Health in Older Adults with and without Osteoporosis: Cross-Sectional Results of the OUTDOOR ACTIVE Study. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio-Rodríguez, A.; Letenneur, L.; Féart, C.; Avila-Funes, J.A.; Amieva, H.; Pérès, K. The Disability Process: Is There a Place for Frailty? Age Ageing 2020, 49, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristea, M.; Noja, G.G.; Stefea, P.; Sala, A.L. The Impact of Population Aging and Public Health Support on EU Labor Markets. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmak, A.R.; Rezapour, A.; Jahangiri, R.; Nikjoo, S.; Farabi, H.; Soleimanpour, S. Economic Burden of Osteoporosis in the World: A Systematic Review. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2020, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, B.R.; Olufade, T.; Bauer, J.; Babrowicz, J.; Hahn, R. Patient-Reported Barriers to Osteoporosis Therapy. Arch Osteoporos 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentin, G.; Ravn, M.B.; Jensen, E.K.; Friis, K.; Bhimjiyani, A.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Hartley, A.; Nielsen, C.P.; Langdahl, B.; Gregson, C.L. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Fragility Fracture Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 61 Observational Studies. Osteoporosis International 2021, 32, 2433–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hejazi, J.; Davoodi, A.; Khosravi, M.; Sedaghat, M.; Abedi, V.; Hosseinverdi, S.; Ehrampoush, E.; Homayounfar, R.; Shojaie, L. Nutrition and Osteoporosis Prevention and Treatment. Biomedical Research and Therapy 2020, 7, 3709–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.K.; Gupta, S.C.; Karelia, D.; Gilhooley, P.J.; Shakibaei, M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Dietary Nutraceuticals as Backbone for Bone Health. Biotechnol Adv 2018, 36, 1633–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosu, O.K.; Ubaoji, K.I. Nutraceuticals: History, Classification and Market Demand. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Florencio-Silva, R.; Sasso, G.R.D.S.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Simões, M.J.; Cerri, P.S. Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGirolamo, D.J.; Clemens, T.L.; Kousteni, S. The Skeleton as an Endocrine Organ. Nature Publishing Group 2012, 8, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, P.; Laue, K.; Ferron, M.; Confavreux, C.; Wei, J.; Galán-Díez, M.; Lacampagne, A.; Mitchell, S.J.; Mattison, J.A.; Chen, Y.; et al. Osteocalcin Signaling in Myofibers Is Necessary and Sufficient for Optimum Adaptation to Exercise. Cell Metab 2016, 23, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosialou, I.; Shikhel, S.; Liu, J.M.; Maurizi, A.; Luo, N.; He, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zong, H.; Friedman, R.A.; Barasch, J.; et al. MC4R-Dependent Suppression of Appetite by Bone-Derived Lipocalin 2. Nature 2017, 543, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldknow, K.J.; MacRae, V.E.; Farquharson, C. Endocrine Role of Bone: Recent and Emerging Perspectives beyond Osteocalcin. Journal of Endocrinology 2015, 225, R1–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubara, Y.; Fushimi, T.; Tagami, T.; Sawa, N.; Hoshino, J.; Yokota, M.; Katori, H.; Takemoto, F.; Hara, S. Histomorphometric Features of Bone in Patients with Primary and Secondary Hypoparathyroidism. Kidney Int 2003, 63, 1809–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubara, Y.; Tagami, T.; Nakanishi, S.; Sawa, N.; Hoshino, J.; Suwabe, T.; Katori, H.; Takemoto, F.; Hara, S.; Takaichi, K. Significance of Minimodeling in Dialysis Patients with Adynamic Bone Disease. Kidney Int 2005, 68, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido, T. Osteocyte-Driven Bone Remodeling. Calcif Tissue Int 2014, 94, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronenberg, H.M. Developmental Regulation of the Growth Plate. Nature 2003, 423, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B. Normal Bone Anatomy and Physiology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008, 3 Suppl 3.

- Mackie, E.J.; Tatarczuch, L.; Mirams, M. The Skeleton: A Multi-Functional Complex Organ. The Growth Plate Chondrocyte and Endochondral Ossification. Journal of Endocrinology 2011, 211, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zhu, L.; Hou, N.; Lan, Y.; Wu, X.M.; Zhou, B.; Teng, Y.; Yang, X. Osteogenic Fate of Hypertrophic Chondrocytes. Cell Res 2014, 24, 1266–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duer, M.J. The Contribution of Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy to Understanding Biomineralization: Atomic and Molecular Structure of Bone. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2015, 253, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Q.; Peng, J.; Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Cell-Derived Extracellular Matrix: Basic Characteristics and Current Applications in Orthopedic Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2016, 22, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentolila, V.; Boyce, T.M.; Fyhrie, D.P.; Drumb, R.; Skerry, T.M.; Schaffler, M.B. Intracortical Remodeling in Adult Rat Long Bones after Fatigue Loading. Bone 1998, 23, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolagas, S.C. Birth and Death of Bone Cells: Basic Regulatory Mechanisms and Implications for the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Osteoporosis; 2000. B: and Death of Bone Cells.

- Hauge, E.M.; Qvesel, D.; Eriksen, E.F.; Mosekilde, L.; Melsen, F. Cancellous Bone Remodeling Occurs in Specialized Compartments Lined by Cells Expressing Osteoblastic Markers. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2001, 16, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, G.J.; Findlay, D.M. Osteocyte Regulation of Bone Mineral: A Little Give and Take. Osteoporosis International 2012, 23, 2067–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallas, S.L.; Prideaux, M.; Bonewald, L.F. The Osteocyte: An Endocrine Cell... and More. Endocr Rev 2013, 34, 658–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, S.; Ishii, K.; Amizuka, N.; Li, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Kohno, K.; Ito, M.; Takeshita, S.; Ikeda, K. Targeted Ablation of Osteocytes Induces Osteoporosis with Defective Mechanotransduction. Cell Metab 2007, 5, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaissé, J.M.; Andersen, T.L.; Engsig, M.T.; Henriksen, K.; Troen, T.; Blavier, L. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP) and Cathepsin K Contribute Differently to Osteoclastic Activities. Microsc Res Tech 2003, 61, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Boyce, B.F. Regulation of Apoptosis in Osteoclasts and Osteoblastic Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 328, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.A.; Martin, T.J. Coupling Signals between the Osteoclast and Osteoblast: How Are Messages Transmitted between These Temporary Visitors to the Bone Surface? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaisse, J.-M. The Reversal Phase of the Bone-Remodeling Cycle: Cellular Prerequisites for Coupling Resorption and Formation. Bonekey Rep 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Irie, N.; Takada, Y.; Shimoda, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Nishiwaki, T.; Suda, T.; Matsuo, K. Bidirectional EphrinB2-EphB4 Signaling Controls Bone Homeostasis. Cell Metab 2006, 4, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, K.; Otaki, N. Bone Cell Interactions through Eph/Ephrin: Bone Modeling, Remodeling and Associated Diseases. Cell Adh Migr 2012, 6, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke Anderson, H. Matrix Vesicles and Calcification. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2003, 5, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Houston, D.A.; Farquharson, C.; MacRae, V.E. Characterisation of Matrix Vesicles in Skeletal and Soft Tissue Mineralisation. Bone 2016, 87, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.C.; Garimella, R.G.; Tague, S.E. THE ROLE OF MATRIX VESICLES IN GROWTH PLATE DEVELOPMENT AND BIOMINERALIZATION. Frontiers in Bioscience 2005, 822–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkre, J.S.; Bassett, J.H.D. The Bone Remodelling Cycle. Ann Clin Biochem 2018, 55, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouresmaeili, F.; Kamalidehghan, B.; Kamarehei, M.; Goh, Y.M. A Comprehensive Overview on Osteoporosis and Its Risk Factors. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018, 14, 2029–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiniakova, M.; Babikova, M.; Mondockova, V.; Blahova, J.; Kovacova, V.; Omelka, R. The Role of Macronutrients, Micronutrients and Flavonoid Polyphenols in the Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demontiero, O.; Vidal, C.; Duque, G. Aging and Bone Loss: New Insights for the Clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2012, 4, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, C.Y.; Nusse, R. The Wnt Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2004, 20, 781–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, T.P.; Später, D.; Taketo, M.M.; Birchmeier, W.; Hartmann, C. Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Prevents Osteoblasts from Differentiating into Chondrocytes. Dev Cell 2005, 8, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sarosi, I.; Cattley, R.C.; Pretorius, J.; Asuncion, F.; Grisanti, M.; Morony, S.; Adamu, S.; Geng, Z.; Qiu, W.; et al. Dkk1-Mediated Inhibition of Wnt Signaling in Bone Results in Osteopenia. Bone 2006, 39, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldring, S.R.; Goldring, M.B. Eating Bone or Adding It: The Wnt Pathway Decides; 2007. T: Bone or Adding It.

- Li, J.Y.; Walker, L.D.; Tyagi, A.M.; Adams, J.; Neale Weitzmann, M.; Pacifici, R. The Sclerostin-Independent Bone Anabolic Activity of Intermittent PTH Treatment Is Mediated by T-Cell-Produced Wnt10b. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2014, 29, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, C.A.; Plotkin, L.I.; Galli, C.; Goellner, J.J.; Gortazar, A.R.; Allen, M.R.; Robling, A.G.; Bouxsein, M.; Schipani, E.; Turner, C.H.; et al. Control of Bone Mass and Remodeling by PTH Receptor Signaling in Osteocytes. PLoS One 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.C.; Bilezikian, J.P. Parathyroid Hormone: Anabolic and Catabolic Actions on the Skeleton. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2015, 22, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Driel, M.; van Leeuwen, J.P.T.M. Vitamin D Endocrine System and Osteoblasts. Bonekey Rep 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, P.H.; Schipani, E. The Roles of Parathyroid Hormone and Calcitonin in Bone Remodeling: Prospects for Novel Therapeutics; 2006; Vol. 6.

- Iglesias, L.; Yeh, J.K.; Castro-Magana, M.; Aloia, J.F. Effects of Growth Hormone on Bone Modeling and Remodeling in Hypophysectomized Young Female Rats: A Bone Histomorphometric Study. J Bone Miner Metab 2011, 29, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, R.S.; Jilka, R.L.; Parfitt, A.M.; Manolagas, S.C. Inhibition of Osteoblastogenesis and Promotion of Apoptosis of Osteoblasts and Osteocytes by Glucocorticoids Potential Mechanisms of Their Deleterious Effects on Bone; 1998; Vol. 102.

- Khosla, S.; Oursler, M.J.; Monroe, D.G. Estrogen and the Skeleton. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012, 23, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.H.; Chen, L.R.; Chen, K.H. Osteoporosis Due to Hormone Imbalance: An Overview of the Effects of Estrogen Deficiency and Glucocorticoid Overuse on Bone Turnover. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Jiang, F.; Guan, D.; Lu, C.; Guo, B.; Chan, C.; Peng, S.; Liu, B.; Guo, W.; Zhu, H.; et al. Metabolomics and Its Application in the Development of Discovering Biomarkers for Osteoporosis Research. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderschueren, D.; Vandenput, L.; Boonen, S.; Lindberg, M.K.; Bouillon, R.; Ohlsson, C. Androgens and Bone. Endocr Rev 2004, 25, 389–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderer, M.; Richards, R.G.; Alini, M.; Stoddart, M.J. Role and Regulation of Runx2 in Osteogenesis. Eur Cell Mater 2014, 28, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wu, X.; Lei, W.; Pang, L.; Wan, C.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, L.; Nagy, T.R.; Peng, X.; Hu, J.; et al. TGF-Β1-Induced Migration of Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells Couples Bone Resorption with Formation. Nat Med 2009, 15, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, K.A.; Raisz, L.G.; Pilbeam, C.C. Prostaglandins in Bone: Bad Cop, Good Cop? Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010, 21, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolini, D.R.; Nedwin, G.E.; Bringman, T.S.; Smith, D.D.; Mundy, G.R. Stimulation of Bone Resorption and Inhibition of Bone Formation in Vitro by Human Tumour Necrosis Factors. Nature 1986, 319, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David Roodman, G. Calcified Tissue International Role of Cytokines in the Regulation of Bone Resorption; 1993.

- Trajanoska, K.; Rivadeneira, F. The Genetic Architecture of Osteoporosis and Fracture Risk. Bone 2019, 126, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Long, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, S. An Analysis and Systematic Review of Sarcopenia Increasing Osteopenia Risk. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, C.; Confavreux, C.B.; Mehsen, N.; Paccou, J.; Leboime, A.; Legrand, E. Severity of Osteoporosis: What Is the Impact of Co-Morbidities? Joint Bone Spine 2010, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, Z.; Quarles, L.D.; Li, W. Osteoporosis: Mechanism, Molecular Target and Current Status on Drug Development. Curr Med Chem 2020, 28, 1489–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deplas, A.; Debiais, F.; Alcalay, M.; Bontoux, D.; Thomas, P. Bone Density, Parathyroid Hormone, Calcium and Vitamin D Nutritional Status of Institutionalized Elderly Subjects. J Nutr Health Aging 2004, 8, 400–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A.Catharine.; Taylor, L.C.; Yaktine, L.A.; Del Valle, B.H.; Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. In Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2011; ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papadimitriou, K.; Voulgaridou, G.; Georgaki, E.; Tsotidou, E.; Zantidou, O.; Papandreou, D. Exercise and Nutrition Impact on Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia—the Incidence of Osteosarcopenia: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, A.E.; Szymczak-Tomczak, A.; Rychter, A.M.; Zawada, A.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Impact of Cigarette Smoking on the Risk of Osteoporosis in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, D. Modulation of Bone Remodeling by the Gut Microbiota: A New Therapy for Osteoporosis. Bone Res 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, D.; Crandall, C.J.; Kupsco, A.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Liao, D.; Yanosky, J.D.; Ramirez, A.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Shen, Y.; et al. Air Pollution and Decreased Bone Mineral Density among Women’s Health Initiative Participants. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snega Priya, P.; Pratiksha Nandhini, P.; Arockiaraj, J. A Comprehensive Review on Environmental Pollutants and Osteoporosis: Insights into Molecular Pathways. Environ Res 2023, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunyecz, J.A. The Use of Calcium and Vitamin D in the Management of Osteoporosis; 2008; Vol. 4.

- Lu, J.; Shin, Y.; Yen, M.S.; Sun, S.S. Peak Bone Mass and Patterns of Change in Total Bone Mineral Density and Bone Mineral Contents From Childhood Into Young Adulthood. Journal of Clinical Densitometry 2016, 19, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Sapra, L.; Mishra, P.K. Osteometabolism: Metabolic Alterations in Bone Pathologies. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varacallo, M.A.; Fox, E.J. Osteoporosis and Its Complications. Medical Clinics of North America 2014, 98, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, J.; Lin, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, Z.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Qiao, J.; Zhang, T.; et al. The Global Burden of Osteoporosis, Low Bone Mass, and Its Related Fracture in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2019. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Norton, N.; Harvey, N.C.; Jacobson, T.; Johansson, H.; Lorentzon, M.; Mccloskey, E. V; Willers, C.; Borgström, F. SCOPE 2021: A New Scorecard for Osteoporosis in Europe. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; McDonald, J.M. Disorders of Bone Remodeling. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2011, 6, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.M.; Pasco, J.A.; Ugoni, A.M.; Nicholson, G.C.; Seeman, E.; Martin, T.J.; Skoric, B.; Panahi, S.; Kotowicz, M.A. The Exclusion of High Trauma Fractures May Underestimate the Prevalence of Bone Fragility Fractures in the Community: The Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 1998, 13, 1337–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.E.; Criddle, R.A.; Comito, T.L.; Prince, R.L. A Case-Control Study of Quality of Life and Functional Impairment in Women with Long-Standing Vertebral Osteoporotic Fracture; 1999.

- Maghbooli, Z.; Hossein-Nezhad, A.; Jafarpour, M.; Noursaadat, S.; Ramezani, M.; Hashemian, R.; Moattari, S. Direct Costs of Osteoporosis-Related Hip Fractures: Protocol for a Cross-Sectional Analysis of a National Database. BMJ Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, G.; Fassio, A.; Gatti, D.; Viapiana, O.; Benini, C.; Danila, M.I.; Saag, K.G.; Rossini, M. Osteoporosis in 10 Years Time: A Glimpse into the Future of Osteoporosis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Study Group, H.O. Osteoporosis International WHO Study Document Assessment of Fracture Risk and Its Application to Screening for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: Synopsis of a WHO Report; 1994; Vol. 4.

- Khashayar, P.; Taheri, E.; Adib, G.; Zakraoui, L.; Larijani, B. Osteoporosis Strategic Plan for the Middle East and North Africa Region. Arch Osteoporos 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, R.; Brandi, M.L.; Checchia, G.; Di Munno, O.; Dominguez, L.; Falaschi, P.; Fiore, C.E.; Iolascon, G.; Maggi, S.; Michieli, R.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Osteoporosis and Fragility Fractures. Intern Emerg Med 2019, 14, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloskey, E. V.; Johansson, H.; Oden, A.; Kanis, J.A. From Relative Risk to Absolute Fracture Risk Calculation: The FRAX Algorithm. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2009, 7, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doosti-Irani, A.; Poorolajal, J.; Cheraghi, Z.; Irani, A.D.; Khalilian, A.; Esmailnasab, N. Prevalence of Osteoporosis in Iran: A Meta-Analysis Association of Body Mass Index with Dyslipidemia among the Government Staff of Kermanshah, Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study View Project GLIMMIX Model Applied to a Study of Food Items and Related Nutrients; Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS). View Project Prevalence of Osteoporosis in Iran: A Meta-Analysis; 2013.

- Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y.; Boonen, S.; Bréart, G.; Diez-Perez, A.; Felsenberg, D.; Kaufman, J.M.; Kanis, J.A.; Cooper, C. Adverse Reactions and Drug-Drug Interactions in the Management of Women with Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2011, 89, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komm, B.S.; Chines, A.A. An Update on Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators for the Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Maturitas 2012, 71, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukon, Y.; Makino, T.; Kodama, J.; Tsukazaki, H.; Tateiwa, D.; Yoshikawa, H.; Kaito, T. Molecular-Based Treatment Strategies for Osteoporosis: A Literature Review. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, M.J.; Mönkkönen, J.; Munoz, M.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Bisphosphonates and New Insights into Their Effects Outside the Skeleton. Bone 2020, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.R. Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators and Bone Health. Climacteric 2022, 25, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, J.G.; Saya, S.; Minshall, J.; Bickerstaffe, A.; Hewabandu, N.; Qama, A.; Emery, J.D. Benefits and Harms of Selective Oestrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) to Reduce Breast Cancer Risk: A Cross-Sectional Study of Methods to Communicate Risk in Primary Care. British Journal of General Practice 2019, 69, E836–E842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.R.; Ferrari, S.; Eastell, R.; Gilchrist, N.; Jensen, J.B.; McClung, M.; Roux, C.; Törring, O.; Valter, I.; Wang, A.T.; et al. Vertebral Fractures After Discontinuation of Denosumab: A Post Hoc Analysis of the Randomized Placebo-Controlled FREEDOM Trial and Its Extension. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2018, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Cho, Y.; Lim, W. Osteoporosis Therapies and Their Mechanisms of Action (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandeira, L.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Bilezikian, J.P. Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Salmon Calcitonin in the Treatment of Osteoporosis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2016, 12, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoch, S.A.; Wagner, J.A. Cathepsin K Inhibitors: A Novel Target for Osteoporosis Therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008, 83, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Wu, Z.; Chu, H.Y.; Lu, J.; Lyu, A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G. Cathepsin K: The Action in and Beyond Bone. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, M.T.; Clarke, B.L.; Oursler, M.J.; Khosla, S. Cathepsin K Inhibitors for Osteoporosis: Biology, Potential Clinical Utility, and Lessons Learned. Endocr Rev 2017, 38, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotra, M.; Rubin, M.R.; Bilezikian, J.P. The Use of Parathyroid Hormone in the Treatment of Osteoporosis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2006, 7, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, E.G.; Mai, Y.; Pham, C. Abaloparatide: Review of a Next-Generation Parathyroid Hormone Agonist. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2018, 52, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B.L. Anti-Sclerostin Antibodies: Utility in Treatment of Osteoporosis. Maturitas 2014, 78, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.Y.; Bolster, M.B. Profile of Romosozumab and Its Potential in the Management of Osteoporosis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017, 11, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilmane, M.; Salma-Ancane, K.; Loca, D.; Locs, J.; Berzina-Cimdina, L. Strontium and Strontium Ranelate: Historical Review of Some of Their Functions. Materials Science and Engineering C 2017, 78, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginster, J.Y.; Seeman, E.; De Vernejoul, M.C.; Adami, S.; Compston, J.; Phenekos, C.; Devogelaer, J.P.; Curiel, M.D.; Sawicki, A.; Goemaere, S.; et al. Strontium Ranelate Reduces the Risk of Nonvertebral Fractures in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis: Treatment of Peripheral Osteoporosis (TROPOS) Study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2005, 90, 2816–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donneau, A.F.; Reginster, J.Y. Cardiovascular Safety of Strontium Ranelate: Real-Life Assessment in Clinical Practice. Osteoporosis International 2014, 25, 397–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riso, P.; Soldati, L. Food Ingredients and Supplements: Is This the Future? J Transl Med 2012, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, M.; El-Sohemy, A.; Cahill, L.; Ferguson, L.R.; French, T.A.C.; Tai, E.S.; Milner, J.; Koh, W.P.; Xie, L.; Zucker, M.; et al. Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics: Viewpoints on the Current Status and Applications in Nutrition Research and Practice. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics 2011, 4, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, J.P. A Current Look at Nutraceuticals – Key Concepts and Future Prospects. Trends Food Sci Technol 2017, 62, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhalifa, A.E.O.; Alshammari, E.; Adnan, M.; Alcantara, J.C.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Eltoum, N.E.; Mehmood, K.; Panda, B.P.; Ashraf, S.A. Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus) as a Potential Dietary Medicine with Nutraceutical Importance for Sustainable Health Applications. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Tiwari, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, K. Nutraceuticals Inspiring the Current Therapy for Lifestyle Diseases. Adv Pharmacol Sci 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scicchitano, P.; Cameli, M.; Maiello, M.; Modesti, P.A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Novo, S.; Palmiero, P.; Saba, P.S.; Pedrinelli, R.; Ciccone, M.M. Nutraceuticals and Dyslipidaemia: Beyond the Common Therapeutics. J Funct Foods 2014, 6, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, A.; Novellino, E. Nutraceuticals - Shedding Light on the Grey Area between Pharmaceuticals and Food. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2018, 11, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.D.; Narayana, R.C.; Narayanan, A. V. The Emergence of India as a Blossoming Market for Nutraceutical Supplements: An Overview. Trends Food Sci Technol 2019, 86, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, A.; Kalaivani, M. Designer Foods and Their Benefits: A Review. J Food Sci Technol 2013, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, V.; Nagpal, M.; Singh, I.; Singh, M.; Dhingra, G.A.; Huanbutta, K.; Dheer, D.; Sharma, A.; Sangnim, T. A Comprehensive Review on Nutraceuticals: Therapy Support and Formulation Challenges. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, R.; Wairkar, S.; Gaud, R. Nutraceuticals for Better Management of Osteoporosis: An Overview. J Funct Foods 2018, 47, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, E.A.; Wehler, C.; Garcia, R.I.; Harris, S.S.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Calcium and Vitamin D Supplements Reduce Tooth Loss in the Elderly; 2001; Vol. 111.

- Price, C.T.; Langford, J.R.; Liporace, F.A. Open Access Essential Nutrients for Bone Health and a Review of Their Availability in the Average North American Diet; 2012; Vol. 6.

- Manske, S.L.; Lorincz, C.R.; Zernicke, R.F. Bone Health: Part 2, Physical Activity. Sports Health 2009, 1, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, C.T.; Langford, J.R.; Liporace, F.A. Essential Nutrients for Bone Health and a Review of Their Availability in the Average North American Diet; 2012; Vol. 6.

- Karpouzos, A.; Diamantis, E.; Farmaki, P.; Savvanis, S.; Troupis, T. Nutritional Aspects of Bone Health and Fracture Healing. J Osteoporos 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sojka, J.E. Magnesium Supplementation and Osteoporosis. Nutr Rev 2009, 53, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondanelli, M.; Faliva, M.A.; Tartara, A.; Gasparri, C.; Perna, S.; Infantino, V.; Riva, A.; Petrangolini, G.; Peroni, G. An Update on Magnesium and Bone Health. BioMetals 2021, 34, 715–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, S.; Cazzaniga, A.; Albisetti, W.; Maier, J.A.M. Magnesium and Osteoporosis: Current State of Knowledge and Future Research Directions. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3022–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, A.; Scambia, G.; Lello, S. Calcium, Vitamin D, Vitamin K2, and Magnesium Supplementation and Skeletal Health. Maturitas 2020, 140, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C. The Role of Nutrients in Bone Health, from A to Z. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2006, 46, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, E.; Yamamoto, H.; Yamanaka-Okumura, H.; Taketani, Y. Dietary Phosphorus in Bone Health and Quality of Life. Nutr Rev 2012, 70, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. Beneficial Effects of Potassium on Human Health. In Proceedings of the Physiologia Plantarum; August 2008; Vol. 133; pp. 725–735. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh, E.; Paragh, G.; Jeney, V. Influence of Iron on Bone Homeostasis. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, K.; Zimmermann, M.B. Nutritional Anemia. In; Kraemer, K., Zimmermann, M.B., Eds.; SIGHT AND LIFE, : Basel, Switzerland, 2007 ISBN 3-906412-33-4.

- Wuehler, S.E.; Peerson, J.M.; Brown, K.H. Use of National Food Balance Data to Estimate the Adequacy of Zinc in National Food Supplies: Methodology and Regional Estimates. Public Health Nutr 2005, 8, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstead, H.H.; Freeland-Graves, J.H. Dietary Phytate, Zinc and Hidden Zinc Deficiency. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2014, 28, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devirian, T.A.; Volpe, S.L. The Physiological Effects of Dietary Boron. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2003, 43, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, L. Nothing Boring About Boron; 2015; Vol. 14.

- Mutlu, M.; Argun, M.; Kilic, E.; Saraymen, R.; Yazar, A.S. Magnesium, Zinc and Copper Status in Osteoporotic, Oshteopenic and Normal Post-Menopausal Women; 2007; Vol. 35.

- Zofkova, I.; Davis, M.; Blahos, J. Trace Elements Have Beneficial, as Well as Detrimental Effects on Bone Homeostasis. Physiol Res 2017, 66, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONLAN, D.; KORULA, R.; TALLENTIRE, D. Serum Copper Levels in Elderly Patients with Femoral-Neck Fractures. Age Ageing 1990, 19, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, C.; Gutiérrez, Á.J.; Revert, C.; Reguera, J.I.; Burgos, A.; Hardisson, A. Daily Dietary Intake of Iron, Copper, Zinc and Manganese in a Spanish Population. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2009, 60, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Gupta, S.C.; Park, B.; Yadav, V.R.; Aggarwal, B.B. Turmeric (Curcuma Longa) Inhibits Inflammatory Nuclear Factor (NF)-ΚB and NF-ΚB-Regulated Gene Products and Induces Death Receptors Leading to Suppressed Proliferation, Induced Chemosensitization, and Suppressed Osteoclastogenesis. Mol Nutr Food Res 2012, 56, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Activation of Transcription Factor NF-B Is Suppressed by Curcumin (Diferulolylmethane)*; 1995.

- Von Metzler, I.; Krebbel, H.; Kuckelkorn, U.; Heider, U.; Jakob, C.; Kaiser, M.; Fleissner, C.; Terpos, E.; Sezer, O. Curcumin Diminishes Human Osteoclastogenesis by Inhibition of the Signalosome-Associated IκB Kinase. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009, 135, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Wang, F.; Gao, Y.; Yin, P.; Pan, C.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. Curcumin Protects Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells against Oxidative Stress-Induced Inhibition of Osteogenesis. J Pharmacol Sci 2016, 132, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandersen, P. Ipriflavone in the Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis<SUBTITLE>A Randomized Controlled Trial</SUBTITLE>. JAMA 2001, 285, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compston, J.E. Sex Steroids and Bone. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhiuto, F.; De Pasquale, R.; Guglielmo, G.; Palumbo, D.R.; Zangla, G.; Samperi, S.; Renzo, A.; Circosta, C. Effects of Phytoestrogenic Isoflavones from Red Clover (Trifolium Pratense L.) on Experimental Osteoporosis. Phytother. Res 2007, 21, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton-Bligh, P.B.; Baber, R.J.; Fulcher, G.R.; Nery, M.-L.; Moreton, T. The Effect of Isoflavones Extracted from Red Clover (Rimostil) on Lipid and Bone Metabolism. Menopause 2001, 8, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Rodrigues, J.; Carmo, S.C.; Silva, J.C.; Fernandes, M.H.R. Inhibition of Human in Vitro Osteoclastogenesis by Equisetum Arvense. Cell Prolif 2012, 45, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Jung, J.W.; Ha, B.G.; Hong, J.M.; Park, E.K.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.Y. The Effects of Luteolin on Osteoclast Differentiation, Function in Vitro and Ovariectomy-Induced Bone Loss. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2011, 22, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perut, F.; Roncuzzi, L.; Avnet, S.; Massa, A.; Zini, N.; Sabbadini, S.; Giampieri, F.; Mezzetti, B.; Baldini, N. Strawberry-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles Prevent Oxidative Stress in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambari, L.; Grigolo, B.; Grassi, F. Dietary Organosulfur Compounds: Emerging Players in the Regulation of Bone Homeostasis by Plant-Derived Molecules. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.X.; Lin, F.J.; Li, H.; Li, H. Bin; Wu, D.T.; Geng, F.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y.; Miao, B.H.; Gan, R.Y. Recent Advances in Bioactive Compounds, Health Functions, and Safety Concerns of Onion (Allium Cepa L.). Front Nutr 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.W.K.; Rabie, A.B.M. Effect of Quercetin on Preosteoblasts and Bone Defects; 2008; Vol. 2.

- Tsuji, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Sato, T.; Mizuha, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Taketani, Y.; Kato, S.; Terao, J.; Inakuma, T.; Takeda, E. Dietary Quercetin Inhibits Bone Loss without Effect on the Uterus in Ovariectomized Mice. J Bone Miner Metab 2009, 27, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suleria, H.A.R.; Butt, M.S.; Anjum, F.M.; Saeed, F.; Khalid, N. Onion: Nature Protection Against Physiological Threats. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2015, 55, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadian, F.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Azaraein, M.H.; Faraji, R.; Zavar-Reza, J. The Effect of Consumption of Garlic Tablet on Proteins Oxidation Biomarkers in Postmenopausal Osteoporotic Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Electron Physician 2017, 9, 5670–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, C.M.; Alekel, D.L.; Ward, W.E.; Ronis, M.J. Flavonoid Intake and Bone Health. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 2012, 31, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, C.H.; Lau, K.M.; Choy, W.Y.; Leung, P.C. Effects of Tea Catechins, Epigallocatechin, Gallocatechin, and Gallocatechin Gallate, on Bone Metabolism. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 7293–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.L.; Chyu, M.C.; Wang, J.S. Tea and Bone Health: Steps Forward in Translational Nutrition1-5. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.P.; Sheu, S.Y.; Sun, J.S.; Chen, M.H. Icariin Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation and Bone Resorption by Suppression of MAPKs/NF-ΚB Regulated HIF-1α and PGE2 Synthesis. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perut, F.; Roncuzzi, L.; Avnet, S.; Massa, A.; Zini, N.; Sabbadini, S.; Giampieri, F.; Mezzetti, B.; Baldini, N. Strawberry-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles Prevent Oxidative Stress in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davicco, M.-J.; Wittrant, Y.; Coxam, V. Berries, Their Micronutrients and Bone Health. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2016, 19, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, Q.; Aslam, N. The Pharmacological Activities of Prunes: The Dried Plums. Article in Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2011, 5, 1508–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Arjmandi, B.H.; Khalil, D.A.; Lucas, E.A.; Georgis, A.; Stoecker, B.J.; Hardin, C.; Payton, M.E.; Wild, R.A. Dried Plums Improve Indices of Bone Formation in Postmenopausal Women; 2002; Vol. 11.

- Tou, J.C. Resveratrol Supplementation Affects Bone Acquisition and Osteoporosis: Pre-Clinical Evidence toward Translational Diet Therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2014, 1852, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Huang, Y.-M.; Xiao, B.-X.; Ren, G.-F. Effects of Resveratrol on Bone Mineral Density in Ovarectomized Rats; 2005.

- Toba, Y.; Takada, Y.; Matsuoka, Y.; Morita, Y.; Motouri, M.; Hirai, T.; Suguri, T.; Aoe, S.; Kawakami, H.; Kumegawa, M.; et al. Milk Basic Protein Promotes Bone Formation and Suppresses Bone Resorption in Healthy Adult Men. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2001, 65, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toba, Y.; Takada, Y.; Yamamura, J.; Tanaka, M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Kawakami, H.; Itabashi, A.; Aoe, S.; Kumegawa, M. Milk Basic Protein: A Novel Protective Function of Milk against Osteoporosis. Bone 2000, 27, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOE, S.; TOBA, Y.; YAMAMURA, J.; KAWAKAMI, H.; YAHIRO, M.; KUMEGAWA, M.; ITABASHI, A.; TAKADA, Y. Controlled Trial of the Effects of Milk Basic Protein (MBP) Supplementation on Bone Metabolism in Healthy Adult Women. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2001, 65, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvaneh, K.; Jamaluddin, R.; Karimi, G.; Erfani, R. Effect of Probiotics Supplementation on Bone Mineral Content and Bone Mass Density. The Scientific World Journal 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz-Ahrens, K.E.; Schaafsma, G.; van den Heuvel, E.G.; Schrezenmeir, J. Effects of Prebiotics on Mineral Metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr 2001, 73, 459s–464s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.M.; Martin, B.R.; Nakatsu, C.H.; Armstrong, A.P.; Clavijo, A.; McCabe, L.D.; McCabe, G.P.; Duignan, S.; Schoterman, M.H.C.; Van Den Heuvel, E.G.H.M. Galactooligosaccharides Improve Mineral Absorption and Bone Properties in Growing Rats through Gut Fermentation. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 6501–6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whisner, C.M.; Castillo, L.F. Prebiotics, Bone and Mineral Metabolism. Calcif Tissue Int 2018, 102, 443–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M.; Artoni, A.; Lauretani, F.; Borghi, L.; Nouvenne, A.; Valenti, G.; Ceda, G. The Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Osteoporosis. Curr Pharm Des 2009, 15, 4157–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satomura, K.; Tobiume, S.; Tokuyama, R.; Yamasaki, Y.; Kudoh, K.; Maeda, E.; Nagayama, M. Melatonin at Pharmacological Doses Enhances Human Osteoblastic Differentiation in Vitro and Promotes Mouse Cortical Bone Formation in Vivo. J Pineal Res 2007, 42, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, A.; Sheeja, A.A.; Janardanan, D. Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity of Melatonin and Its Related Indolamines. Free Radic Res 2020, 54, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresguerres, I.F.; Tamimi, F.; Eimar, H.; Barralet, J.E.; Prieto, S.; Torres, J.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L.; Tresguerres, J.A.F. Melatonin Dietary Supplement as an Anti-Aging Therapy for Age-Related Bone Loss. Rejuvenation Res 2014, 17, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catinean, A.; Neag, M.A.; Muntean, D.M.; Bocsan, I.C.; Buzoianu, A.D. An Overview on the Interplay between Nutraceuticals and Gut Microbiota. PeerJ 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalto, M.; D’Onofrio, F.; Gallo, A.; Cazzato, A.; Gasbarrini, G. Intestinal Microbiota and Its Functions. Digestive and Liver Disease Supplements 2009, 3, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Hazen, S.L. The Contributory Role of Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2014, 124, 4204–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.W.; An, J.H.; Park, H.; Yang, J.Y.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Yim, M.; Baek, W.Y.; et al. Positive Regulation of Osteogenesis by Bile Acid through FXR. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2013, 28, 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, S.; Omata, Y.; Hofmann, J.; Böttcher, M.; Iljazovic, A.; Sarter, K.; Albrecht, O.; Schulz, O.; Krishnacoumar, B.; Krönke, G.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Regulate Systemic Bone Mass and Protect from Pathological Bone Loss. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalvany-Antonucci, C.C.; Duffles, L.F.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; Zicker, M.C.; de Oliveira, S.; Macari, S.; Garlet, G.P.; Madeira, M.F.M.; Fukada, S.Y.; Andrade, I.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and FFAR2 as Suppressors of Bone Resorption. Bone 2019, 125, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kim, S.A.; Choi, Y.M.; Kwon, H.K.; Shim, W.; Lee, G.; Choi, S. Capric Acid Inhibits NO Production and STAT3 Activation during LPS-Induced Osteoclastogenesis. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ma, L.; Ding, Y.; He, L.; Chang, M.; Shan, Y.; Siwko, S.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Y.; et al. Fatty Acid Sensing GPCR (GPR84) Signaling Safeguards Cartilage Homeostasis and Protects against Osteoarthritis. Pharmacol Res 2021, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Song, Y.W.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, F.J.; Wang, X.M.; Zhuang, X.H.; Wu, F.; Liu, J. Association between Bile Acid Metabolism and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women. Clinics 2020, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fu, C.; Li, F. Acetate Affects the Process of Lipid Metabolism in Rabbit Liver, Skeletal Muscle and Adipose Tissue. Animals 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, M.; Alqubaisy, M.; Aljaafari, M.N.; Alali, A.O.; Baqais, L.; Molouki, A.; Abushelaibi, A.; Lai, K.S.; Lim, S.H.E. Nutraceuticals: Transformation of Conventional Foods into Health Promoters/Disease Preventers and Safety Considerations. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godad, A.; Ansari, A.; Bhatia, N.; Ali, A.; Zine, S.; Doshi, G. Drug Nutraceutical Interactions. In Industrial Application of Functional Foods, Ingredients and Nutraceuticals; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 663–723.

- Gil, F.; Hernández, A.F.; Martín-Domingo, M.C. Toxic Contamination of Nutraceuticals and Food Ingredients. In Nutraceuticals; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 825–837.

- Anadón, A.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.R.; Ares, I.; Martínez, M.A. Interactions between Nutraceuticals/Nutrients and Therapeutic Drugs. In Nutraceuticals; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 855–874.

- Santini, A.; Cammarata, S.M.; Capone, G.; Ianaro, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Pani, L.; Novellino, E. Nutraceuticals: Opening the Debate for a Regulatory Framework. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018, 84, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, A.S.; Lordan, R.; Horbańczuk, O.K.; Atanasov, A.G.; Chopra, I.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Jóźwik, A.; Huang, L.; Pirgozliev, V.; Banach, M.; et al. The Current Use and Evolving Landscape of Nutraceuticals. Pharmacol Res 2022, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, G.B. The Quality of Commercially Available Nutraceutical Supplements and Food Sources. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2011, 63, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronis, M.J.J.; Pedersen, K.B.; Watt, J. Adverse Effects of Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2018, 58, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonds, D.E.; Harrington, M.; Worrall, B.B.; Bertoni, A.G.; Eaton, C.B.; Hsia, J.; Robinson, J.; Clemons, T.E.; Fine, L.J.; Chew, E.Y. Effect of Long-Chain ω-3 Fatty Acids and Lutein+zeaxanthin Supplements on Cardiovascular Outcomes: Results of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014, 174, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, G.E.; Thornquist, M.D.; Balmes, J.; Cullen, M.R.; Meykens, F.L.; Omenn, G.S.; Valanis, B.; Williams, J.H. The Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial: Incidence of Lung Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality during 6-Year Follow-up after Stopping β-Carotene and Retinol Supplements. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004, 96, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; Lee, I.-M.; Christen, W.; Bassuk, S.S.; Mora, S.; Gibson, H.; Gordon, D.; Copeland, T.; D’Agostino, D.; et al. Vitamin D Supplements and Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Preziosi, P.; Bertrais, S.; Mennen, L.; Malvy, D.; Roussel, A.-M.; Favier, A.; Briançon, S. The SU.VI.MAX Study A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Health Effects of Antioxidant Vitamins and Minerals.

- Lippman, S.M.; Klein, E.A.; Goodman, P.J.; Lucia, M.S.; Thompson, I.M.; Ford, L.G.; Parnes, H.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Gaziano, J.M.; Hartline, J.A.; et al. Effect of Selenium and Vitamin E on Risk of Prostate Cancer and Other Cancers: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2009, 301, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesso, H.D.; Rist, P.M.; Aragaki, A.K.; Rautiainen, S.; Johnson, L.G.; Friedenberg, G.; Copeland, T.; Clar, A.; Mora, S.; Moorthy, M.V.; et al. Multivitamins in the Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease: The COcoa Supplement and Multivitamin Outcomes Study (COSMOS) Randomized Clinical Trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022, 115, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A. Nutraceuticals in Human Health. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Lewis, E.D.; Antony, J.M.; Crowley, D.C.; Guthrie, N.; Blumberg, J.B. Breaking New Frontiers: Assessment and Re-Evaluation of Clinical Trial Design for Nutraceuticals. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldanha, L.G. US Food and Drug Administration Regulations Governing Label Claims for Food Products, Including Probiotics. In Proceedings of the Clinical Infectious Diseases; February 1 2008; Vol. 46.

- Nuzzo, R. Scientific Method: Statistical Errors. Nature 2014, 506, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaput, J. Developing the Pathway to Personalized Health: The Potential of N-of-1 Studies for Personalizing Nutrition. Journal of Nutrition 2021, 151, 2863–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Fu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Gou, W.; Miao, Z.; Yang, M.; Ordovás, J.M.; Zheng, J.S. Individual Postprandial Glycemic Responses to Diet in N-of-1 Trials: Westlake N-of-1 Trials for Macronutrient Intake (WE-MACNUTR). Journal of Nutrition 2021, 151, 3158–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, T.; Vieira, R.; De Roos, B. Perspective: Application of N-of-1 Methods in Personalized Nutrition Research. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldevila-Domenech, N.; Boronat, A.; Langohr, K.; de la Torre, R. N-of-1 Clinical Trials in Nutritional Interventions Directed at Improving Cognitive Function. Front Nutr 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, J.-S. Application of N-of-1 Clinical Trials in Personalized Nutrition Research: A Trial Protocol for Westlake N-of-1 Trials for Macronutrient Intake (WE-MACNUTR); 8190. A: of N-of-1 Clinical Trials in Personalized Nutrition Research.

- Paller, C.J.; Denmeade, S.R.; Carducci, M.A. Challenges of Conducting Clinical Trials of Natural Products to Combat Cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2016, 14, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tapsell, L.C. The Journal of Nutrition Evidence for Health Claims on Food: How Much Is Enough? Evidence for Health Claims: A Perspective from the Australia-New Zealand Region 1,2; 2008; Vol. 138.

- L’abbé, M.R.; Dumais, L.; Chao, E.; Junkins, B. The Journal of Nutrition Evidence for Health Claims on Food: How Much Is Enough? Health Claims on Foods in Canada 1-3; 2008; Vol. 138.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).