1. Introduction

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preeclampsia (PE) are two obstetrical complications that occur mainly in the context of ischemic placental disease. PE impacts approximately 2% to 8% of pregnancies and exerts a significant toll, contributing to more than 70,000 maternal deaths and approximately 500,000 fetal demises annually [

1]. Typical clinical manifestations of PE are represented by de-novo hypertension, after 20 weeks of gestation, proteinuria and/or specific organ disfunction (liver dysfunction, acute kidney injury, pulmonary edema, focal neurological manifestations, hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, etc) [

2].

PE can determine maternal complications such as HEELP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count) syndrome or eclampsia (maternal convulsive seizures), and fetal complications such as IUGR and preterm birth, thus its screening and early detection are important elements of obstetrical management that allow clinicians to offer preventive measures (administration of aspirin before 16 weeks of gestation) or to perform an individualized monitoring program [

3,

4,

5].

IUGR can be described as the inability of the fetus to attain its inherent genetic growth potential [

6]. The most important tool for IUGR screening and diagnosis is ultrasound, and the diagnostic criteria include an estimated fetal weight (EFW) < 3

rd percentile or EFW < 10

th percentile in combination with abnormal fetoplacental Doppler parameters [

7]. IUGR itself can be accompanied by important fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, and the long-term consequences include a higher risk of neuropsychomotor disorders or metabolic syndrome [

8,

9,

10].

Most international societies of obstetrics and gynecology (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists- ACOG, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence- NICE, and the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy- ISSHP) recommend a targeted screening of PE in the first trimester of pregnancy, in the presence of maternal risk factors, while the screening of IUGR is recommended to be universally performed, even in the absence of maternal risk factors [

1,

11,

12,

13].

Nowadays, a combined first trimester screening of these disorders is preferred, and it includes maternal characteristics, ultrasound markers, and maternal serum biomarkers. Numerous studies have demonstrated the superiority in terms of predictive performance of a combined screening in comparison with a screening based only on maternal risk factors, and a plethora of maternal biomarkers have been evaluated in order to obtain the best prediction [

14,

15].

PlGF (placental growth factor) is a proangiogenic marker, abundantly expressed in the placenta, vascular endothelial cells, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, smooth muscle cells, and monocytes [

16]. It has been shown that low levels of PlGF are associated with the development of preeclampsia and IUGR [

17,

18,

19].

PP-13 (placental protein-13) is another serum biomarker, member of the galectin family involved in the spiral artery remodeling and placental inflammation, that has demonstrated good predictive performance for IUGR and preeclampsia [

20,

21,

22].

Lately, several studies indicated that predictive models based on artificial intelligence such as artificial neural networks and machine learning-based algorithms could improve the screening strategies of obstetrical disorders and their complications [

5,

8,

23,

24].

The aim of this study was to determine and compare the predictive performance of 4 machine learning based algorithms for the prediction of preeclampsia, IUGR and their association in a cohort of singleton pregnancies with at least 1 risk factor for ischemic placental disease.

2. Results

In the first step of our analysis, we comparatively evaluated the demographic and clinical characteristics of 210 pregnant patients (table 1). Our results indicated that smoking during pregnancy was significantly more frequently encountered in the group of patients who later developed IUGR (n= 6, 40%, p= 0.004) in comparison with other groups. The patients in this group had also a significant personal history of autoimmune disorders (n= 3, 20%, p< 0.001) and adverse pregnancy outcomes (n=3, 20%, p= 0.007) compared to other groups.

On the other hand, patients who later developed PE presented a significant personal history of chronic hypertension (n= 4, 36,3%, p< 0.001) and chronic kidney disease (n= 1, 9%, p= 0.001). Moreover, patients who were later diagnosed with PE and IUGR had a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes melilites compared with other groups (n= 1, 25%, p= 0.01).

The examined groups were similar when we evaluated maternal age, mode of conception, parity, and BMI. Thus, we could not outline a significantly statistical difference regarding these characteristics between groups.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the studied groups.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the studied groups.

| Clinical characteristics |

PE group (n= 11 patients) |

IUGR group (n= 15 patients) |

PE and IUGR group (n= 4 patients) |

Control group (n= 180 patients) |

p value |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) |

29.6±6.19 |

26.12±5.74 |

27.32±5.14 |

29.22±5.31 |

0.52 |

| Spontaneous conception (n/%) |

Yes= 8 (72.7%) |

Yes= 12 (80%) |

Yes= 3 (75%) |

Yes= 155 (86.1%) |

0.56 |

| IVF conception (n/%) |

Yes= 1 (9%) |

Yes= 2 (13.3%) |

Yes= 1 (25%) |

Yes= 15 (8.3%) |

0.64 |

| ICSI conception (n/%) |

Yes= 2 (18.1%) |

Yes= 1 (6.6%) |

Yes= 0 (0%) |

Yes= 10 (5.5%) |

0.18 |

| Nuliparous (n/%) |

Yes= 6 (54.5%) |

Yes= 10 (66.6%) |

Yes= 2 (50%) |

Yes= 95 (52.7%) |

0.77 |

| BMI, kg/m2, (mean and standard deviation) |

25.86± 4.97 |

24.15± 5.01 |

23.62± 3.11 |

23.86± 4.16 |

0.15 |

| Smoking habit (n/%) |

Yes= 2 (18.1%) |

Yes= 6 (40%) |

Yes= 1 (25%) |

Yes= 17 (9.4%) |

0.004 |

| Diabetes (n/%) |

Yes= 1 (9%) |

Yes= 1 (6.6%) |

Yes= 1 (25%) |

Yes= 3 (1.6%) |

0.01 |

| History of chornic hypertension (n/%) |

Yes= 4 (36.3%) |

Yes= 2 (13.3%) |

Yes= 2 (50%) |

Yes= 5 (2.7%) |

< 0.001 |

| History of autoimune disorders (n/%) |

Yes= 1 (9%) |

Yes= 3 (20%) |

Yes= 1 (25%) |

Yes= 3 (1.6%) |

< 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease (n/%) |

Yes= 1 (9%) |

Yes= 0 (0%) |

Yes= 0 (0%) |

Yes= 4 (2.2%) |

0.001 |

| History of adverse pregnancy outcomes (n/%) |

Yes= 2 (18.1%) |

Yes= 3 (20%) |

Yes= 1 (25%) |

Yes= 11 (6.1%) |

0.07 |

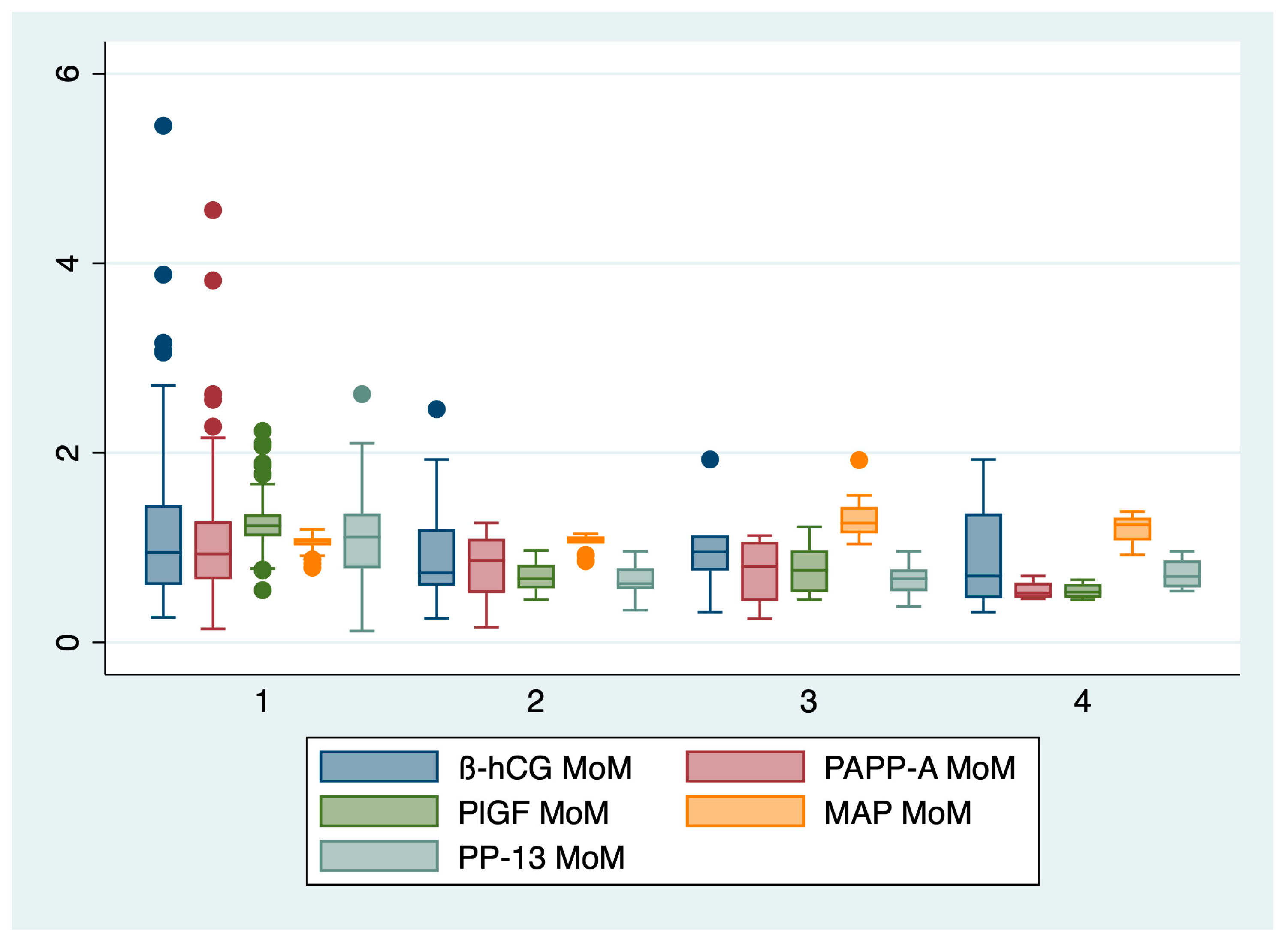

In the second step of our analysis, we compared the biochemical markers and mean arterial pressure between groups, and the results are presented in table 2 and in figure 1.

The ANOVA analysis followed by Bonferroni posthoc test indicated a statistically significant difference between the evaluated groups regarding the following markers: PAPP-A (p= 0.002), PlGF (p= 0.02), PP-13 (p< 0.001), and MAP (p< 0.001). The serum β-HCG levels determined in the first trimester of pregnancy did not significantly differ among groups (p= 0.16).

The mean arterial pressure was significantly higher for patients who later developed preeclampsia (1.34± 0.24 MoM), while the serum values of PAPP-A, PlGF, and PP-13 were significantly lower for patients who later developed preeclampsia and/or IUGR in comparison with the control group.

Table 2.

Comparisons of the first trimester biochemical markers and mean arterial pressure between groups.

Table 2.

Comparisons of the first trimester biochemical markers and mean arterial pressure between groups.

| Marker |

PE group (n= 11 patients) |

IUGR group (n= 15 patients) |

PE and IUGR group (n= 4 patients) |

Control group (n= 180 patients) |

p value |

| β-HCG, MoM (mean ± SD) |

0.96± 0.41 |

0.96± 0.65 |

0.91± 0.70 |

1.14± 0.75 |

0.16 |

| PAPP-A, MoM (mean ± SD) |

0.73± 0.34 |

0.81± 0.34 |

0.55± 0.11 |

1.05± 0.57 |

0.002 |

| PlGF, MoM (mean ± SD) |

0.77± 0.27 |

0.69± 0.14 |

0.54± 0.09 |

1.27± 0.24 |

0.02 |

| PP-13, MoM (mean ± SD) |

0.67± 0.19 |

0.66± 0.17 |

0.72± 0.18 |

1.09± 0.44 |

<0.001 |

| MAP, MoM (mean ± SD) |

1.34± 0.24 |

1.06± 0.09 |

1.20± 0.19 |

1.06± 0.06 |

<0.001 |

Figure 1.

Boxplot representing the comparison of the first trimester markers between groups. 1- control group, 2- IUGR group, 3- PE group, 4- PE and IUGR group.

Figure 1.

Boxplot representing the comparison of the first trimester markers between groups. 1- control group, 2- IUGR group, 3- PE group, 4- PE and IUGR group.

In the third step of our analysis, we included the clinical characteristics and marker values determined in the first trimester of pregnancy into a database that was used for testing and training of 4 machine learning-based algorithms. The results are comprised in table 3.

When we evaluated the predictive performance of the 4 machine-learning based algorithms for the prediction of preeclampsia, we found that RF algorithm obtained the best results, with a sensitivity (Se) of 90.9%, specificity (Sp) of 96.6%, false positive rate (FPR) of 3%, and accuracy of 96.3%. Both NB and SVM obtained similar results in terms of sensitivity (81.8%), specificity (95.5 versus 96.6%), and accuracy (94.7 versus 95.8%).

RF (Se- 93.3%, Sp- 96.1%, and accuracy 95.9%) and SVM (Se- 93.3%, Sp- 95.5%, and accuracy-95.3%) had similar performances for the prediction of IUGR, followed by NB (Se- 86.6%, Sp- 96.1%, and accuracy- 95.3%) and DT (Se- 73.3%, Sp- 95%, and accuracy 93.3%).

Early onset IUGR was similarly predicted by all algorithms, but RF obtained the best results in terms of accuracy (96.2%). Late onset IUGR was also best predicted by RF, with a Se of 88.8%, specificity of 95.5%, and accuracy of 95.2%.

Finally, all algorithms had modest performance for the prediction of PE-IUGR association, but the best overall accuracies were achieved by NB and RF (95.1%).

Table 3.

Predictive performance of 4 machine learning-based algorithms for the prediction of PE, IUGR and their association.

Table 3.

Predictive performance of 4 machine learning-based algorithms for the prediction of PE, IUGR and their association.

| ML model |

Groups |

Se (%) |

SP (%) |

FPR (%) |

Matthews coefficient |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision |

F1 score |

| DT |

IUGR (15 patients) |

73.3 |

95 |

5 |

0.45 |

93.3 |

0.55 |

0.62 |

| Early IUGR (6 patients) |

83.3 |

93.8 |

6 |

0.48 |

93.5 |

0.31 |

0.45 |

| Late IUGR (9 patients) |

77.7 |

93.3 |

6 |

0.50 |

92.6 |

0.36 |

0.50 |

| PE (11 patients) |

72.7 |

94.4 |

5 |

0.55 |

94 |

0.44 |

0.55 |

| PE+IUGR (4 patients) |

75 |

94.4 |

5 |

0.76 |

94 |

0.23 |

0.35 |

| NB |

IUGR (17 patients) |

86.6 |

96.1 |

3 |

0.72 |

95.3 |

0.65 |

0.74 |

| Early IUGR (6 patients) |

83.3 |

96.1 |

3 |

0.57 |

95.7 |

0.41 |

0.55 |

| Late IUGR (11 patients) |

77.7 |

94.4 |

5 |

0.53 |

93.6 |

0.41 |

0.53 |

| PE (11 patients) |

81.8 |

95.5 |

4 |

0.63 |

94.7 |

0.52 |

0.64 |

| PE+IUGR (4 patients) |

75.1 |

95.5 |

4 |

0.43 |

95.1 |

0.27 |

0.40 |

| SVM |

IUGR (17 patients) |

93.3 |

95.5 |

4 |

0.74 |

95.3 |

0.63 |

0.75 |

| Early IUGR (6 patients) |

83.3 |

95 |

5 |

0.52 |

94.6 |

0.35 |

0.50 |

| Late IUGR (11 patients) |

66.6 |

94.4 |

5 |

0.46 |

93.1 |

0.37 |

0.48 |

| PE (11 patients) |

81.8 |

96.6 |

3 |

0.67 |

95.8 |

0.6 |

0.69 |

| PE+IUGR (4 patients) |

0.75 |

0.95 |

5 |

0.41 |

94.5 |

0.25 |

0.37 |

| RF |

IUGR (17 patients) |

93.3 |

96.1 |

3 |

0.76 |

95.9 |

0.66 |

0.77 |

| Early IUGR (6 patients) |

83.3 |

96.7 |

3 |

0.59 |

96.2 |

0.83 |

0.58 |

| Late IUGR (11 patients) |

88.8 |

95.5 |

4 |

0.64 |

95.2 |

0.5 |

0.64 |

| PE (11 patients) |

90.9 |

96.6 |

3 |

0.73 |

96.3 |

0.62 |

0.74 |

| PE+IUGR (4 patients) |

75 |

95.5 |

4 |

0.43 |

95.1 |

0.27 |

0.40 |

Finally, we evaluated the main pregnancy outcomes among groups, and the results are presented in table 4. Neonates that were born from mothers diagnosed with preeclampsia or presented a growth restriction pattern during pregnancy had significantly more frequently adverse neonatal outcomes such as preterm birth (mostly iatrogenic), low Apgar score (7 or less), ARDS, invasive ventilation and NICU admission (p< 0.001).

Table 4.

Neonatal outcomes of the evaluated groups.

Table 4.

Neonatal outcomes of the evaluated groups.

| Neonatal outcome |

PE group (n= 11 patients) |

IUGR group (n= 15 patients) |

PE and IUGR group (n= 4 patients) |

Control group (n= 180 patients) |

p value |

| Preterm birth (n/%) |

Yes= 8 (72.7%) |

Yes= 12 (80%) |

Yes= 3 (75%) |

Yes= 25 (13.8%) |

< 0.001 |

| Low Apgar score (n/%) |

Yes= 4 (36.3%) |

Yes= 5 (33.3%) |

Yes= 2 (50%) |

Yes= 10 (5.5%) |

< 0.001 |

| ARDS (n/%) |

Yes= 3 (27.2%) |

Yes= 4 (26.6%) |

Yes= 2 (50%) |

Yes= 8 (4.4%) |

< 0.001 |

| Invasive ventilation (n/%) |

Yes= 2 (18.1%) |

Yes= 1 (6.6%) |

Yes= 2 (50%) |

Yes= 5 (2.7%) |

< 0.001 |

| NICU admission (n/%) |

Yes= 2 (72.7%) |

Yes= 1 (80%) |

Yes= 2 (75%) |

Yes= 5 (13.8%) |

< 0.001 |

3. Discussion

The prediction of preeclampsia and IUGR remains a persistent challenge for obstetricians since these disorders are associated with important morbidity and mortality rates for both mothers and newborns. The classical screening program of these disorders, based only on maternal risk factors, has proven to be limited in terms of predictive performance, but it is still used in countries with limited financial resources [

25]. Recent advances in screening strategies for these obstetrical disorders have increased predictive performance, and include a variety of markers [

26]. The problem with this approach is the limited number of parameters included, as well as the high amount of human and financial resources required for their completion.

Every screening program can be improved, and in this study, we aimed to test the predictive performance of 4 machine learning-based algorithms for the prediction of PE and IUGR, as well as their association, that encompassed maternal clinical characteristics, serum biomarkers and MAP determined in the first trimester of pregnancy. We hypothesized that this approach would offer at least comparable results in terms of predictive performance as the combined screening strategies.

Our results indicated that RF performed the best when used to predict PE, IUGR and its subtypes, as well as the association between PE and IUGR. The overall predictive performance of DT for all these disorders was inferior to RF, NB, and SVM. Both SVM and NB had similar accuracies for the prediction of PE, while NB performed better than SVM for the prediction of IUGR.

These results could be explained by the fact that RF is a complex algorithm, capable of operating with complex datasets, that demonstrated good overall predictive performance when used to predict obstetrical syndromes. For example, in a recent study by Melinte-Popescu et al., the authors indicated that RF achieved an accuracy of 92.8% for the prediction of PE [

24]. Also, Liu et al., demonstrated in a retrospective study that RF outperformed other machine learning-based algorithms such as DT and SVM for the prediction of PE, with an accuracy of 74% [

27].

Rescinito et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, analyzing data from 20 studies that examined the use of artificial intelligence/machine learning models for predicting IUGR [

28]. The results of this analysis indicated that these techniques demonstrated a favorable overall diagnostic performance. Specifically, the sensitivity was found to be 0.84 (95% CI 0.80-0.88), the specificity was 0.87 (95% CI 0.83-0.90), the positive predictive value was 0.78 (95% CI 0.68-0.86), and the negative predictive value was 0.91 (95% CI 0.86-0.94). Furthermore, the researchers demonstrated that the combination of random forest and support vector machine (RF-SVM) yielded the highest level of accuracy (97%) in predicting intrauterine growth restriction [

28].

Previous research has indicated that the prediction of early fetal growth restriction may pose greater challenges [

29,

30]. This phenomenon could be attributed to the possibility that certain risk factors linked to intrauterine growth restriction, such as maternal health conditions or placental abnormalities, may not manifest until the later stages of pregnancy. The machine learning algorithms we employed yielded comparable outcomes to traditional screening approaches for both early and late intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) [

30,

31].

For an individualized management, it is important to identify maternal risk factors for IUGR, PE, and other pregnancy complications [

5,

23,

24,

32]. In our study, we found out that IUGR group had significantly more frequently a positive personal history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, autoimmune disease, and smoking habit in comparison with the other groups. On the other hand, patients who later developed PE presented a significant personal history of chronic hypertension and chronic kidney disease. These results are supported by recent literature data, that outlined the impact of comorbidities and lifestyle on the occurrence of pregnancy complications [

8,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

Numerous biochemical and ultrasound markers have been proposed for the prediction of IUGR and PE, but only a few have achieved good predictive performance [

20,

38,

39,

40]. Our results indicated significantly lower serum values of PAPP-A, PlGF, and PP-13 lower for patients who later developed preeclampsia and/or IUGR in comparison with the control group, and are in line with current literature data [

41,

42]. The mean arterial pressure was significantly higher for patients who later developed preeclampsia. On the other hand, the mean values of MAP and UtA-PI determined in the first trimester of pregnancy did not significantly differ between groups. This result could be explained by the small cohort of patients, with heterogenous characteristics.

Machine learning-based algorithms or other artificial intelligence algorithms could be used for the prediction of various disorders or complications, for the classification or for diagnosis and surveillance, and can include a variety of parameters, from clinical data, to biochemical and ultrasound markers, and proteomic and genomic data [

43,

44]. In this prospective study we chose to use an additional serum biomarker, PP-13. It is a member of the galectin family involved in the spiral artery remodeling and placental inflammation, that has demonstrated good predictive performance for IUGR and preeclampsia [

20,

21,

22].

As far as we know, this would be the first prospective study that evaluated this particular combined screening approach on a cohort of singleton pregnancies. Nevertheless, it is important to interpret the findings of this study while taking into account certain limitations. These limitations include the relatively small sample size of patients, the inclusion of only a limited number of clinical and paraclinical characteristics, and the presence of imbalanced data sets. Machine learning algorithms possess the capability to effectively function with limited datasets, rendering them potentially valuable for risk stratification purposes. Conversely, the incorporation of predictive models grounded in machine learning techniques and the prospective design of our research are notable strengths.

Further studies, on larger cohorts of singletons pregnancies, could include various approached of screening into machine learning-based algorithms, and could offer a broader perspective over their predictive performance and utility for clinical practice.

4. Materials and Methods

This prospective study was conducted at “Cuza Voda” Clinical Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Iasi, Romania, between 3rd of January 2023 and 10th of September 2023. The study included pregnant patients with singleton pregnancies and at least 1 risk factor for ischemic placental disease from the following list: maternal age> 35 years old, smoking habit, obesity (body mass index, BMI > 25 kg/m2), family or personal history of preeclampsia or IUGR, maternal comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, chronic hypertension, autoimmune disorders), and who underwent conventional first trimester Down syndrome screening between 11 and 13+6 weeks of gestation.

The exclusion criteria comprised multifetal gestations, maternal age under 18 years old, incorrect first trimester dating of the gestational age, first and second trimester abortions, fetal death in utero, loss of follow-up, incomplete medical records, or the mother’s inability to offer informed consent.

The study was conducted during the project "Net4SCIENCE: Network for Applied Doctoral and Postdoctoral Research in the Fields of Smart Specialization - Health and Bioeconomy," project code SMIS: 154722, and ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy ‘Grigore T. Popa’ (No. 151/13 February 2022).

All patients underwent ultrasound examination, between 11 + 0 and 13 + 6 weeks of gestation, by certified obstetricians using an E8/E10 (General Electric Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) scanner for the measurement of crown–rump length (CRL), uterine artery pulsatility index (UtA-PI), and nuchal translucency (NT).

We collected a blood sample of 5 mL from all participants included in the study, which was stored at -20oC until processing. From the extracted serum we determined values of the following markers: β-HCG, PAPP-A, PlGF (using Brahms Kriptor analyzor, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany) and PP-13 (quantitative sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay- ELISA). The serum values of these markers were transformed into multiple of medians (MoM).

Using a calibrated device (Omron M3 COMFORT; Omron Corp, Kyoto, Japan), blood pressure was measured in accordance with the Fetal Medicine Foundation (FMF) recommendations and the mean arterial pressure (MAP) was noted and transformed into MoMs [

45].

245 patients were monitored during pregnancy, but only data from 210 patients was analyzed in this study due to a lack of information about the pregnancy outcomes. The following data was recorded from all patients: demographic data, BMI, smoking status, personal and family history of adverse pregnancy outcomes (PE, IUGR, preterm birth, abruptio placentae, etc), maternal comorbidities, gestational age at the onset of PE/IUGR, gestational age at birth, birthweight, Apgar score, and adverse neonatal outcomes such as neonatal intensive care unit admission (NICU), intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, or the need of invasive ventilation.

Preeclampsia was defined according to the new ISSHP recommendations [

1], as gestational hypertension accompanied by one or more of the following new-onset conditions at ≥20 weeks’ gestation: a) proteinuria; b) other maternal end-organ dysfunction (neurological complications, pulmonary edema, hematological complications, acute kidney injury, or liver impairment); c) uteroplacental dysfunction.

IUGR was defined and classified using the Delphi consensus [

46], that is based on EFW and abnormal fetoplacental Doppler parameters: into early IUGR (< 32 weeks of gestation), and late IUGR (≥ 32 weeks of gestation).

The following groups were examined, which corresponded to the main outcomes of our study: preeclampsia group (n= 11 patients), IUGR group (n= 15 patients), PE+IUGR (n= 4 patients), and control group (n= 180 patients). Secondary, we evaluated the predictive performance of machine learning algorithms for early (n= 6 patients), and late IUGR (n= 9 patients).

In the first phase of our analysis, we used descriptive statistics, and comparison of categorical variables (Pearson's χ2 test) or continuous variables (ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test) between our groups. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. These analyses were performed using STATA SE (version 17, 2023, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

In the second phase of our analysis, we constructed 4 predictive models based on machine learning: decision tree (DT), naïve Bayes (NB), support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF), that included the following data: maternal characteristics (age, BMI, smoking status, personal or family history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, comorbidities), MAP, values of serum biomarkers such as BHCG, PAPP-A, PlGF, and PP-13. Data was segregated into 70% testing and 30% training, and underwent 5-fold cross validation.

A sensitivity analysis was performed for characterizing the predictive performance of these models for PE, IUGR, PE+IUGR, early IUGR and late IUGR. The models were constructed and analyzed using Matlab (version R2023a, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

5. Conclusions

Ischemic placental disease prediction is a vast field of research and innovative approaches are needed in order to optimize our current screening strategies.

Our approach included a combined screening strategy into 4 machine learning-based algorithms for the prediction of PE, IUGR, and their association, with the best predictive performance of these obstetrical disorders being achieved by RF.

Further studies could validate this approach on larger cohorts of patients, and our research could use as a basis for an integrative perspective over ischemic placental disease prediction.

Author Contributions

This paper was written as part of a doctoral program of I.A.V. at UMF “Grigore T. Popa”. Conceptualization, I.A.V, I.S.S., I.P., B.D., A.C., A-S.M-P., P.V., V.H., M.M-P., A.H., and D.N.; methodology, D.S., E.M., and M.S.C.; software, D.S., E.M., and M.S.C.; validation, D.S., E.M., and M.S.C.; formal analysis, D.S., E.M., and M.S.C.; investigation, I.A.V, I.S.S., I.P., B.D., A.C., A-S.M-P., P.V., V.H., M.M-P., A.H., and D.N.; resources, I.A.V.; data curation D.S., E.M., and M.S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.V, I.S.S., I.P., B.D., A.C., A-S.M-P., P.V., V.H., M.M-P., A.H., and D.N.; writing—review and editing, I.A.V, I.S.S., I.P., B.D., A.C., A-S.M-P., P.V., V.H., M.M-P., A.H., and D.N.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, D.N., and B.D.; project administration, I-A.V.; funding acquisition, I.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This article was published with the support of the project “Net4SCIENCE: Applied doctoral and postdoctoral research network in the fields of smart specialization Health and Bioeconomy”, project code POCU/993/6/1/154722.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of ‘Grigore T. Popa’ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi, Romania (No. 151/13 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are part of Ingrid-Andrada Vasilache doctoral research, and are available from this author upon a reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Magee LA, Brown MA, Hall DR, Gupte S, Hennessy A, Karumanchi SA, et al. The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;27:148-69. [CrossRef]

- Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, Magee LA, De Groot CJM, Hofmeyr GJ. Pre-eclampsia. The Lancet. 2016;387(10022):999-1011.

- Dimitriadis E, Rolnik DL, Zhou W, Estrada-Gutierrez G, Koga K, Francisco RPV, et al. Pre-eclampsia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Chang KJ, Seow KM, Chen KH. Preeclampsia: Recent Advances in Predicting, Preventing, and Managing the Maternal and Fetal Life-Threatening Condition. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4). [CrossRef]

- Melinte-Popescu M, Vasilache IA, Socolov D, Melinte-Popescu AS. Prediction of HELLP Syndrome Severity Using Machine Learning Algorithms-Results from a Retrospective Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(2). [CrossRef]

- Gaccioli F, Aye I, Sovio U, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GCS. Screening for fetal growth restriction using fetal biometry combined with maternal biomarkers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2s):S725-s37. [CrossRef]

- Lees CC, Stampalija T, Baschat AA, da Silva Costa F, Ferrazzi E, Figueras F, et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: diagnosis and management of small-for-gestational-age fetus and fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2020;56(2):298-312.

- Vicoveanu P, Vasilache IA, Scripcariu IS, Nemescu D, Carauleanu A, Vicoveanu D, et al. Use of a Feed-Forward Back Propagation Network for the Prediction of Small for Gestational Age Newborns in a Cohort of Pregnant Patients with Thrombophilia. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(4). [CrossRef]

- Monteith C, Flood K, Pinnamaneni R, Levine TA, Alderdice FA, Unterscheider J, et al. An abnormal cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) is predictive of early childhood delayed neurodevelopment in the setting of fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3):273.e1-.e9. [CrossRef]

- D'Agostin M, Di Sipio Morgia C, Vento G, Nobile S. Long-term implications of fetal growth restriction. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(13):2855-63. [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee Opinion, No. 743: Low-Dose Aspirin Use During Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):e44-e52.

- [NG133]. Ng. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. . https://wwwniceorguk/guidance/ng133 [Accessed 14 September 2023]. 2023.

- McCowan LM, Figueras F, Anderson NH. Evidence-based national guidelines for the management of suspected fetal growth restriction: comparison, consensus, and controversy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2s):S855-s68. [CrossRef]

- Chaemsaithong P, Sahota DS, Poon LC. First trimester preeclampsia screening and prediction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2s):S1071-S97.e2. [CrossRef]

- Rolnik DL, Wright D, Poon LCY, Syngelaki A, O'Gorman N, de Paco Matallana C, et al. ASPRE trial: performance of screening for preterm pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(4):492-5. [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, B. Biology of preeclampsia: Combined actions of angiogenic factors, their receptors and placental proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2020;1866(2):165349. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal S, Shinar S, Cerdeira AS, Redman C, Vatish M. Predictive Performance of PlGF (Placental Growth Factor) for Screening Preeclampsia in Asymptomatic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hypertension. 2019;74(5):1124-35. [CrossRef]

- Sherrell H, Dunn L, Clifton V, Kumar S. Systematic review of maternal Placental Growth Factor levels in late pregnancy as a predictor of adverse intrapartum and perinatal outcomes. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2018;225:26-34. [CrossRef]

- Conde-Agudelo A, Papageorghiou A, Kennedy S, Villar J. Novel biomarkers for predicting intrauterine growth restriction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2013;120(6):681-94. [CrossRef]

- Vasilache IA, Carauleanu A, Socolov D, Matasariu R, Pavaleanu I, Nemescu D. Predictive performance of first trimester serum galectin-13/PP-13 in preeclampsia screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2022;23(6):370. [CrossRef]

- Akolekar R, Syngelaki A, Beta J, Kocylowski R, Nicolaides KH. Maternal serum placental protein 13 at 11–13 weeks of gestation in preeclampsia. Prenatal Diagnosis: Published in Affiliation With the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis. 2009;29(12):1103-8. [CrossRef]

- Chafetz I, Kuhnreich I, Sammar M, Tal Y, Gibor Y, Meiri H, et al. First-trimester placental protein 13 screening for preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;197(1):35. e1-. e7. [CrossRef]

- Harabor V, Mogos R, Nechita A, Adam A-M, Adam G, Melinte-Popescu A-S, et al. Machine Learning Approaches for the Prediction of Hepatitis B and C Seropositivity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20(3):2380. [CrossRef]

- Melinte-Popescu A-S, Vasilache I-A, Socolov D, Melinte-Popescu M. Predictive Performance of Machine Learning-Based Methods for the Prediction of Preeclampsia—A Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(2):418. [CrossRef]

- Tan MY, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, Rolnik DL, O'Gorman N, Delgado JL, et al. Screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11-13 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52(2):186-95. [CrossRef]

- Stepan H, Galindo A, Hund M, Schlembach D, Sillman J, Surbek D, et al. Clinical utility of sFlt-1 and PlGF in screening, prediction, diagnosis and monitoring of pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023;61(2):168-80. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Yang X, Chen G, Ding Y, Shi M, Sun L, et al. Development of a prediction model on preeclampsia using machine learning-based method: a retrospective cohort study in China. Front Physiol. 2022;13:896969. [CrossRef]

- Rescinito R, Ratti M, Payedimarri AB, Panella M. Prediction Models for Intrauterine Growth Restriction Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(11). [CrossRef]

- Lees CC, Romero R, Stampalija T, Dall'Asta A, DeVore GA, Prefumo F, et al. Clinical Opinion: The diagnosis and management of suspected fetal growth restriction: an evidence-based approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(3):366-78. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Zhang C. Risk evaluation of fetal growth restriction by combined screening in early and mid-pregnancy. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36(7):1708-13. [CrossRef]

- Figueras F, Caradeux J, Crispi F, Eixarch E, Peguero A, Gratacos E. Diagnosis and surveillance of late-onset fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2s):S790-S802.e1. [CrossRef]

- Melinte-Popescu AS, Popa RF, Harabor V, Nechita A, Harabor A, Adam AM, et al. Managing Fetal Ovarian Cysts: Clinical Experience with a Rare Disorder. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(4). [CrossRef]

- Maftei R, Doroftei B, Popa R, Harabor V, Adam AM, Popa C, et al. The Influence of Maternal KIR Haplotype on the Reproductive Outcomes after Single Embryo Transfer in IVF Cycles in Patients with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss and Implantation Failure-A Single Center Experience. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5). [CrossRef]

- Zonda GI, Mogos R, Melinte-Popescu AS, Adam AM, Harabor V, Nemescu D, et al. Hematologic Risk Factors for the Development of Retinopathy of Prematurity-A Retrospective Study. Children (Basel). 2023;10(3). [CrossRef]

- Vicoveanu P, Vasilache IA, Nemescu D, Carauleanu A, Scripcariu IS, Rudisteanu D, et al. Predictors Associated with Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in a Cohort of Women with Systematic Lupus Erythematosus from Romania-An Observational Study (Stage 2). J Clin Med. 2022;11(7). [CrossRef]

- Socolov D, Socolov R, Gorduza VE, Butureanu T, Stanculescu R, Carauleanu A, et al. Increased nuchal translucency in fetuses with a normal karyotype-diagnosis and management: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(29):e7521. [CrossRef]

- Cucu A, Costea C, Cărăuleanu A, Dumitrescu G, Sava A, Scripcariu I, et al. Meningiomas Related to the Chernobyl Irradiation Disaster in North-Eastern Romania Between 1990 and 2015. Revista de Chimie -Bucharest- Original Edition-. 2018;69.

- Nemescu D, Constantinescu D, Gorduza V, Carauleanu A, Caba L, Navolan DB. Comparison between paramagnetic and CD71 magnetic activated cell sorting of fetal nucleated red blood cells from the maternal blood. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(9):e23420. [CrossRef]

- Pedroso MA, Palmer KR, Hodges RJ, Costa FDS, Rolnik DL. Uterine Artery Doppler in Screening for Preeclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2018;40(5):287-93. [CrossRef]

- Alina-Madalina L, NEMESCU D, SCRIPCARIU S-I, HARABOR A, Ana-Maria A, HARABOR V, et al. ADVANCING PRETERM BIRTH PREDICTION: A PROSPECTIVE MULTICENTRIC STUDY INVESTIGATING THE PREDICTIVE PERFORMANCE OF PARTOSURE, FETAL FIBRONECTIN, AND CERVICAL LENGTH. The Medical-Surgical Journal. 2023;127(2):229-36.

- Birdir C, Droste L, Fox L, Frank M, Fryze J, Enekwe A, et al. Predictive value of sFlt-1, PlGF, sFlt-1/PlGF ratio and PAPP-A for late-onset preeclampsia and IUGR between 32 and 37 weeks of pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;12:124-8. [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe G, Mensink I, Twisk JW, Blankenstein MA, Heijboer AC, van Vugt JM. First trimester screening for intra-uterine growth restriction and early-onset pre-eclampsia. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31(10):955-61. [CrossRef]

- Adam AM, Popa RF, Vaduva C, Georgescu CV, Adam G, Melinte-Popescu AS, et al. Pregnancy Outcomes, Immunophenotyping and Immunohistochemical Findings in a Cohort of Pregnant Patients with COVID-19-A Prospective Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(7). [CrossRef]

- Crockart IC, Brink LT, du Plessis C, Odendaal HJ. Classification of intrauterine growth restriction at 34-38 weeks gestation with machine learning models. Inform Med Unlocked. 2021;23. [CrossRef]

- Gallo D, Poon LC, Fernandez M, Wright D, Nicolaides KH. Prediction of preeclampsia by mean arterial pressure at 11-13 and 20-24 weeks' gestation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2014;36(1):28-37. [CrossRef]

- Gordijn SJ, Beune IM, Thilaganathan B, Papageorghiou A, Baschat AA, Baker PN, et al. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):333-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).