1. Introduction

The kidney is a detoxifying organ that filters and transports not only metabolic waste products from the body, but also drugs and potentially toxic xenobiotics. More than 32% of the 200 most important drugs are excreted via the kidney. The epithelial cells of the proximal convoluted tubule are the major players in the reabsorption and secretion of chemical substances [

1,

2]. This critical role makes proximal epithelial cells (PTEC) particularly vulnerable to damage caused by xenobiotics, which can lead to nephrotoxicity. In fact, an estimated 20% of acute kidney injury (AKI) cases in hospitals are attributed to PTEC-mediated drug nephrotoxicity, making PTEC the most studied cells in drug safety evaluations, regeneration therapies and tissue modeling [

3].

However, the tubular system has regeneration potential, which occurs even in the absence of specific insults to continuously replace aged cells to preserve the organ's structural and functional integrity. However, in the event of nephrotoxicity or other damage to the kidney, the basic cell turnover is significantly exceeded by the regeneration process to repair the damaged areas [

4]. This tubule cell regeneration occurs either by local stem cell proliferation or following epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of tubule epithelial cells near the injury site [

5]. Ultimately, one or a combination of these pathways will restore organ structure and function. Despite the replacement of tubule epithelial cells in the kidney, there is unambiguous evidence that the kidney does not regain one hundred percent of its former function, especially in patients with post-AKI. They have an increasing risk of developing chronic kidney diseases (CKD), suggesting that the functioning of existing tubular cells may have been compromised or those cells replacing injured cells are not fully functional upon regeneration [

6,

7]. Moreover, aging, oxidative stress and toxic agents can interfere with repairing damaged areas, possibly resulting in dysfunction, and ultimately increasing the risk of renal failure [

6]. Therefore, for a meaningful risk assessment, it is necessary to investigate the influence of nephrotoxic substances on renal regeneration.

In response to this challenge, the development of hiPSC-based approaches may provide a promising model for toxicity studies to investigate the effects of nephrotoxic agents on renal regeneration [

8]. hiPSC are primarily derived from reprogrammed human stromal cells (mainly fibroblasts). They have proven to be a robust and reproducible source of human cell types for regeneration and disease modelling, as hiPSC are capable of extensive self-renewal and can differentiate into multiple somatic cell types within the three germ layers [

9]. hiPSC allow studies without ethical concerns compared to animal and human embryonic stem cell (hESC) models [

9]. In addition, their use is consistent with the 3R principles for next-generation toxicity assessment: replacement, reduction, and refinement of animal-based experiments with new methodological approaches [

8,

10]. Interestingly, models using hiPSC have the potential to be more accurate in tailored toxicity assessment than traditional animal models, which have low predictive values and suffer from several limitations, including interspecies differences in transporter expression [

11,

12]. They could also be more suitable than hESC-derived human proximal tubule-like cells, which have a low sensitivity [

1,

13]. Moreover, the use of hiPSC would allow the generation of patient-specific immunocompatible tissues through personalized

in vitro models [

14].

Although various methods for direct differentiation of hESC and hiPSC into PTELC have been reported, the focus has mostly been on using these stem cell-derived renal cells to develop a suitable and reliable model for predicting nephrotoxicity [

13,

15,

16,

17,

18]. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the effects of various toxins on the differentiation process as a model for the tubular regeneration process. Therefore, in this study, we adapted one of the previously published differentiation protocols [

13] to generate PTELC and evaluated the progression of hiPSCs to PTELCs based on mRNA and protein expression. With this differentiation protocol, hiPSCs, hiPSCs differentiating into PTELCs, and hiPSCs differentiated into PTELCs were tested for their sensitivity to selected nephrotoxins. This study confirms the potential of hiPSC to differentiate into PTELCs, which serves as a model to evaluate the renal developmental toxicity of potential nephrotoxic agents, which is essential for meaningful renal damage risk assessment and regenerative therapy.

3. Discussion

For the first time, iPSC, iPSC differentiating into PTELC, and iPSC differentiated into PTELC were studied for their sensitivity towards selected nephrotoxins. These included the genotoxic nephrotoxin cisplatin and the non-genotoxic nephrotoxin cyclosporin A. Two iPSC lines generated using different reprogramming genes were employed here to assess whether the effects were similar. The cells at different stages of differentiation showed different sensitivity to the nephrotoxic agents tested, which may be explained in part by the nature of the agents.

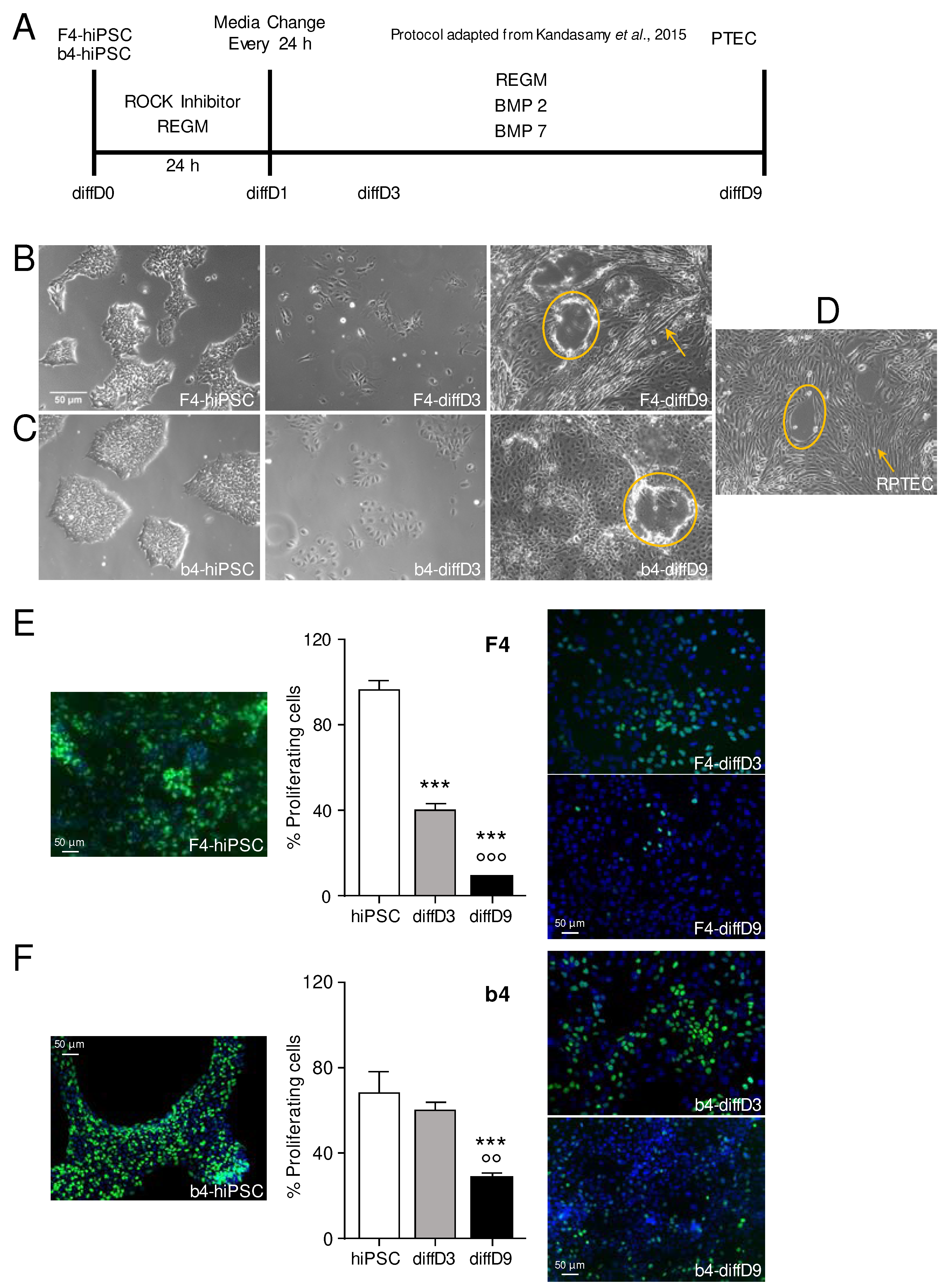

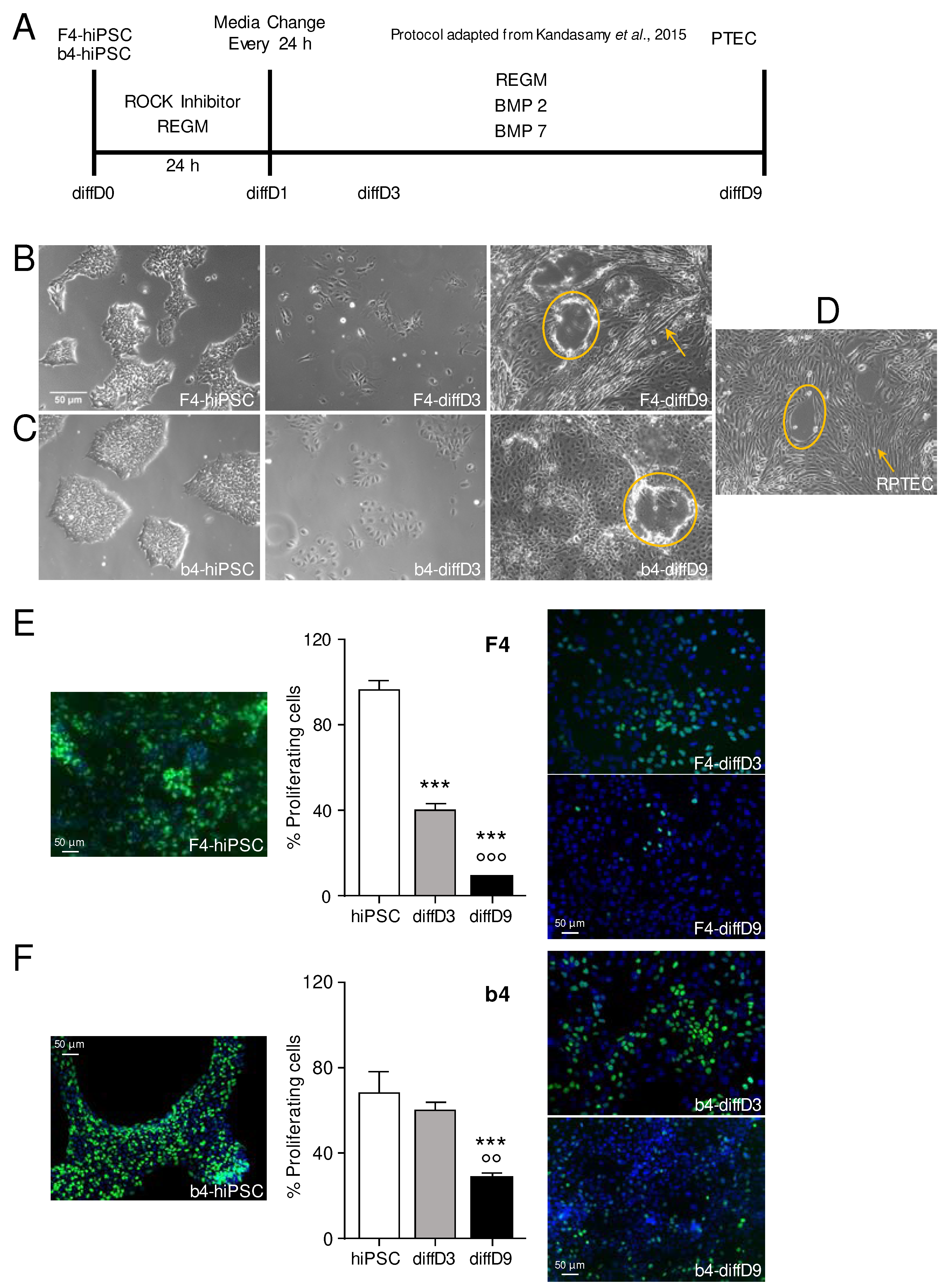

The differentiation of the F4 and b4 hiPSC using the protocol published by Kandasamy et al. [

13] changed the morphology of the cells to a renal cell-like morphology, which also already allowed conclusions about the functional competence of the cells, as they formed tubular like structures and domes. Dome or hemicyst formation occurs by polarized epithelial cells under culture conditions performing trans-epithelial fluid transport [

19]. Furthermore, the strong reduction of proliferation over the time span of the differentiation process equally underlines the distinguished degree of differentiation of the cells after 9 days.

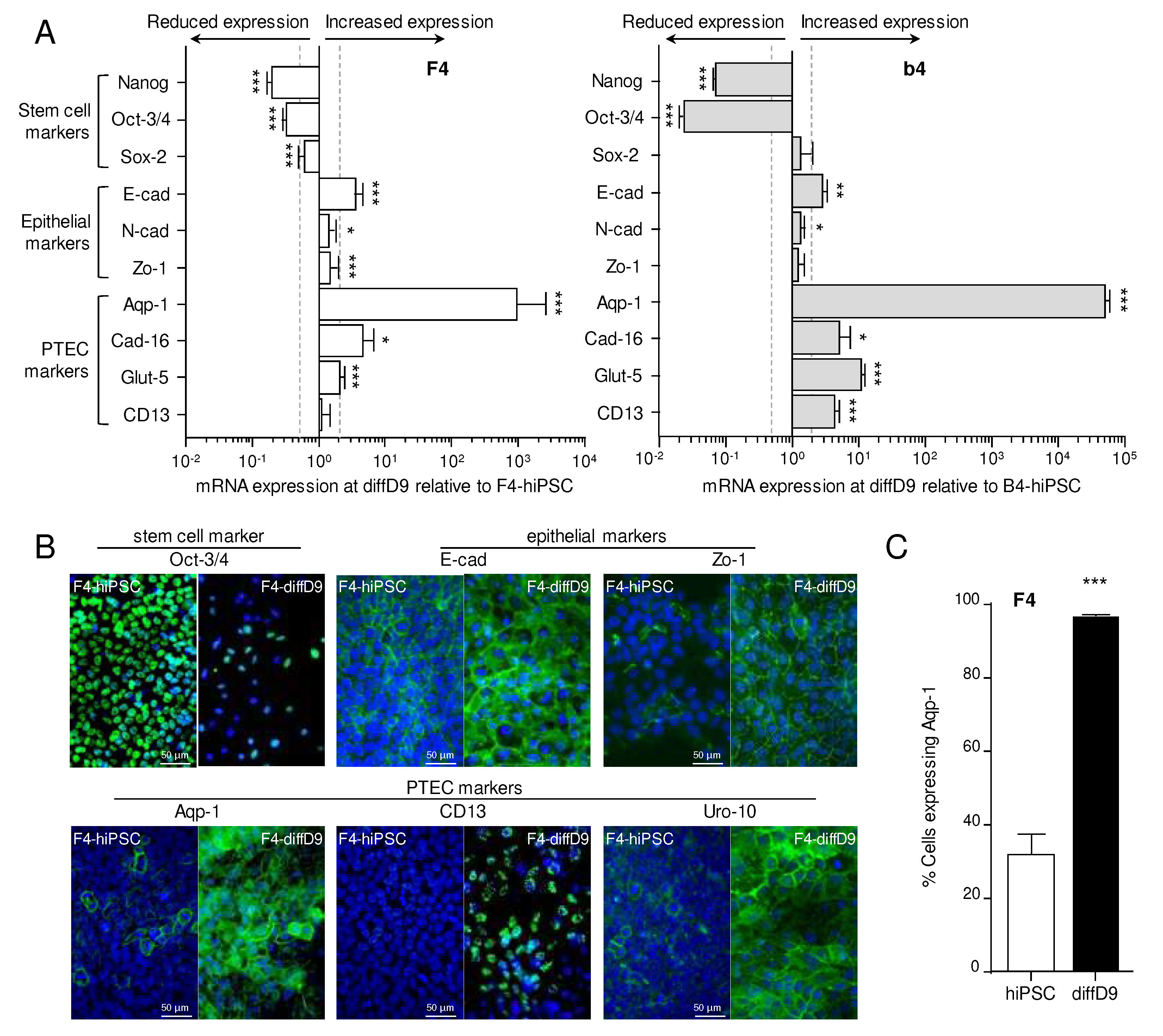

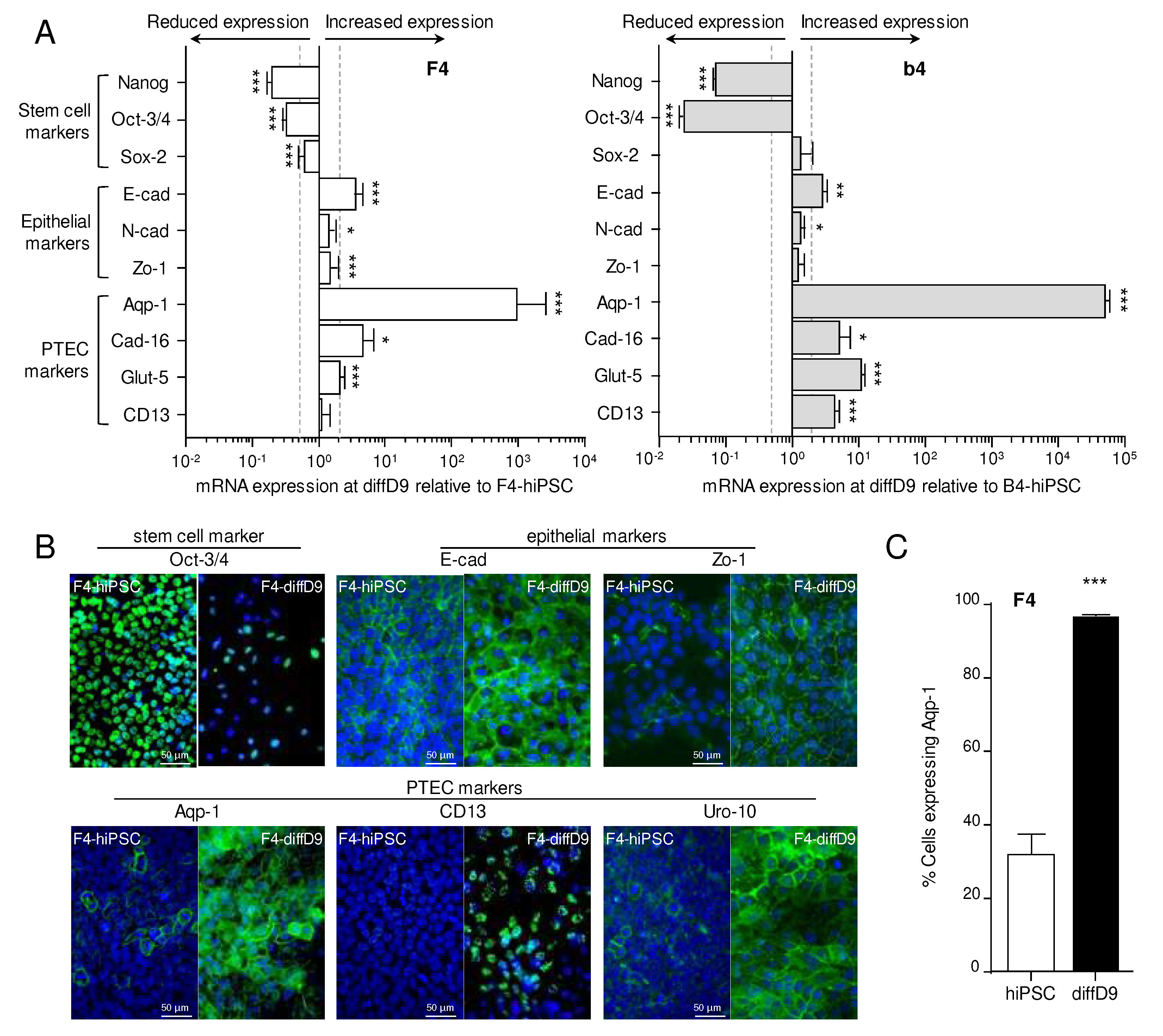

In agreement with Kandasamy et al. [

13], most of the markers analyzed in F4 and b4, such as the stem cell markers Oct3/4, Nanog and Sox2, the epithelial markers E-cadherin and zonula occludens-1, the PTEC markers cadherin-16 and aquaporin-1, and five out of nine transporters showed a comparable change in mRNA expression. The post-differentiation expression levels are also consistent with the data of overlapping markers of PTELC differentiated from iPSC by another research group using an utterly different differentiation protocol [

16]. Consistent with the mRNA data, the stem cell marker Oct-3/4 was also reduced at the protein level after differentiation, as demonstrated by immunocytochemistry, as also shown by Chandrasekaran et al. [

16]. At the same time, epithelial and PTEC markers were also increased with correct cellular localization, except CD-13, which is consistent with the corresponding markers studied by the other two groups [

13,

16]. Moreover, more than 95% of F4 cells were positive for the PTEC marker, aquaporin-1, after differentiation, as quantified by flow cytometry, indicating that the differentiation process was quite efficient, which was also observed by Kandasamy et al. [

13].

However, an important aspect that must be considered when differentiating cells from iPSCs and analyzing expression differences is that RT-qPCR cannot determine an absolute number of genes but only a relative number. This means that the expression of the differentiated cells is related to the expression of the stem cells. Nevertheless, it is not known how much of the examined mRNA the iPSC has already expressed under basal conditions. To reach the pluripotent state during iPSC reprogramming, fibroblasts undergo a mesenchymal to epithelial transition, losing mesenchymal markers and gaining epithelial ones [

20]. They also form adherens junctions, tight junctions, and polarity [

21,

22]. This could explain the minor changes in epithelial markers observed in the gene expression analyses, which were inconsistent with the corresponding protein expression analyses.

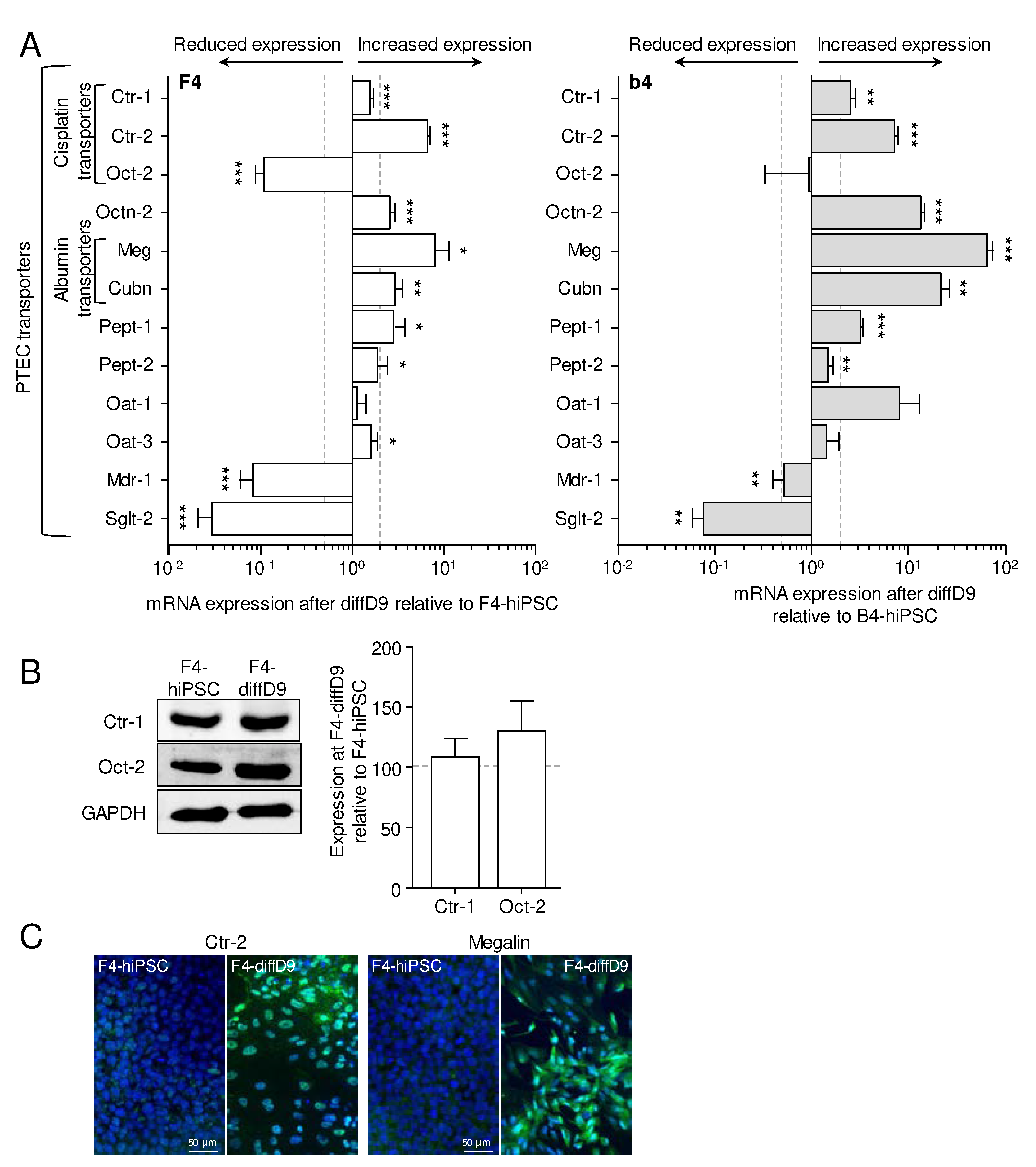

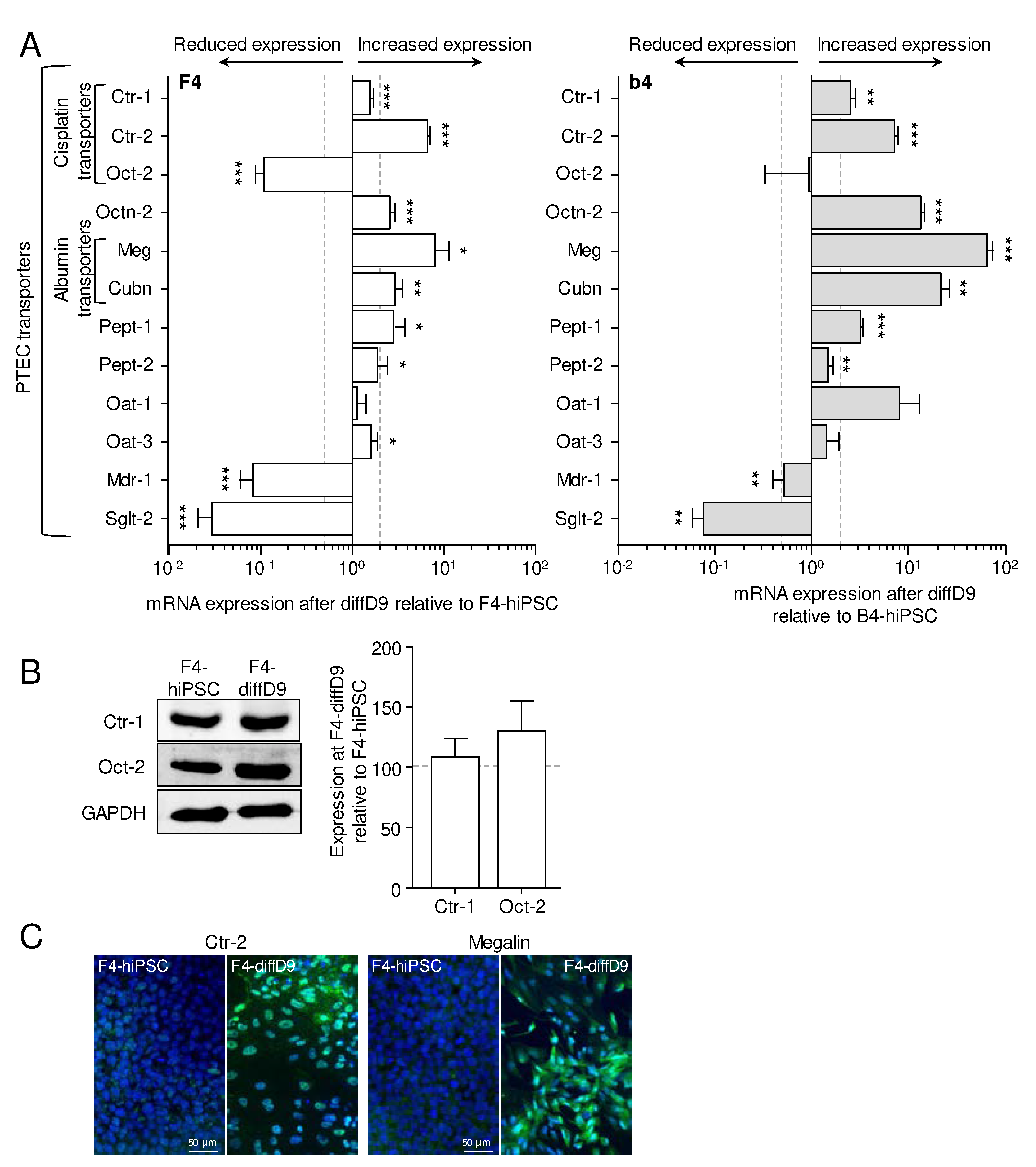

In addition to gene and protein expression patterns similar to those of PTEC, PTELC also expressed essential tubular transporters such as megalin and cubilin, which are responsible for the uptake of albumin, an important function of the proximal tubule and were more highly expressed after differentiation than in F4 and b4. The incorporation of albumin further demonstrates the functionality of our differentiated PTELC, similar to that of LLC-PK1, which served as a positive control. RPTEC/TERT1, on the other hand, had reduced albumin uptake activity. The lack of functional albumin uptake in RPTEC/TERT1 cells has already been reported [

16,

20]. Some of the other studied transporters, like Oct-2, MDR-1, and Sglt-2, decreased their mRNA level compared to the hiPSC. For Oct-2, one of the transporters responsible for cisplatin uptake [

23,

24], we could show no significant difference at the protein level in F4, contrary to the result of a reduced mRNA expression. As cell epithelialization seems crucial to gain pluripotent characteristics [

21], it can be expected that further genes characteristic for epithelial cells besides the common epithelial markers here tested are already basally expressed by the hiPSC, for example, transporters. Reports indicate that some stem cells already express, e.g., the glucose transporter Sglt2 [

25,

26], which appears strongly downregulated in our differentiated cells compared to the hiPSC.

When investigating the sensitivity of cells at different stages of differentiation to cisplatin, it was found that the defense system of the cells against cisplatin must have changed considerably with the differentiation process, as the undifferentiated hiPSC of both lines were the most sensitive, followed by the differentiating cells, while the fully differentiated cells were the least sensitive. This was expected because as a DNA damaging agent, cisplatin interferes with cell division, and the proliferation rate of the differentiated cells was much lower than that of the not yet differentiated cells. Surprisingly, the differentiating F4 cells were as sensitive as the F4-hiPSC, even though the former already exhibited greatly reduced proliferation. Future experiments are needed to reveal whether this comparable sensitivity in the presence of reduced proliferation may be due to the differentiating cells being more susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin. These include mitochondrial damage, direct activation of apoptosis via the TNF family, and triggering of stress at the endoplasmic reticulum (as summarized by [

21]). However, in the case of B4, the differentiating b4 had not yet downregulated their proliferation as much on differentiation day 3, so similar sensitivity to cisplatin was not surprising here.

A few studies have examined the dose-response to cisplatin in stem cells and differentiated cells. The IC

50 values of our F4- and b4-iPSC were in the range of other stem cells, and iPSC and human embryonic stem cells (hESC) were equally sensitive [

22,

23]. A two- to threefold increase in sensitivity between two cell lines, as we saw with b4 and F4, has already been observed by others [

22]. Stem cells derived from amniotic fluid alone were less sensitive [

24]. Cells differentiated from stem cells lose viability only at 10- to 100-fold higher cisplatin concentrations [

25,

26], as did ours. Even far less sensitive to cisplatin are renal organoids generated from stem cells or differentiated PTELC growing on beads [

18,

27]. We are aware of only one study that determined the sensitivity of the differentiated cells as well as the sensitivity of the original iPSC cells, as we did. Here, the IC

50 of the iPSC was in the same range as in our iPSC, whereas the neurons differentiated from them were so resistant that no IC

50 could be determined [

22]. No study measured the sensitivities of cells in the process of differentiation. Cell stages derived from b4 were overall less sensitive (3 to 6 times) to cisplatin than those derived from F4. So far, we have no explanation for this. A possibility might be different levels and activities of multidrug resistance protein-1 (Mdr-1), which is a known exporter of cisplatin, and which needs to be studied in the two hiPSC lines in the future.

With respect to cyclosporin A, the cellular defense system against this substance did not appear to have changed significantly with differentiation as the cells showed concordant sensitivities, suggesting a more general cytotoxic mechanism of cyclosporin A. Effects of cyclosporin A have not been studied in detail in stem cells. Therefore, IC

50 values for cyclosporin A from stem cells or differentiating cells are not available in the literature so far. Most evidence of cyclosporine A in association with stem cells is related to the improved survival of transplanted iPSC due to administered cyclosporine A (i.e., reviewed by Antonios et al. [

28]). Only hiPSC differentiated into brain-like endothelial cells were investigated with regard to their sensitivity to cyclosporin A and showed an IC

50 value of more than 15 µM after a 7-day incubation [

29], which is not comparable to the value of our differentiated cells, which already after 24 h exhibit a lower IC

50. In monocytes, on the other hand, an IC

50 value was determined at approximately 5 µM after 72 h [

30]. In relation to non-stem cells, the literature on cyclosporin A contains very contradictory information. On the one hand, cyclosporin A induces apoptosis, leading to mitochondrial damage and EMT at concentrations between 1 and 5 µM [

30,

31,

32]. On the other hand, it protects against apoptosis and EMT induced by other substances at similar concentrations [

33,

34]. Future studies will reveal which of the acute effects is causing the observed cytotoxicity in our model.

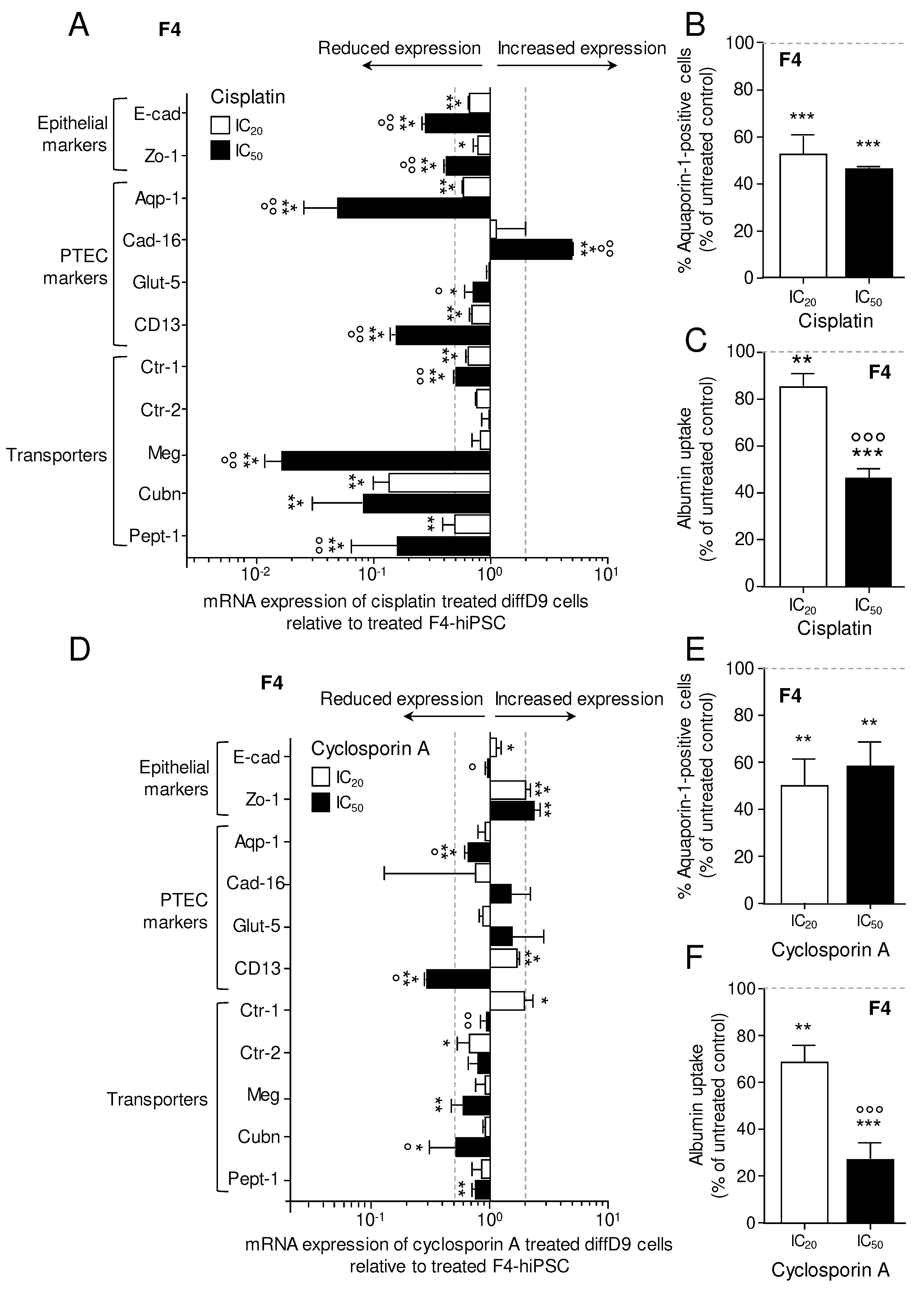

Cisplatin and cyclosporine A treatments not only reduced the viability of the cells tested here but also impaired the fully differentiated cells' function and expression of markers associated with differentiation. Thus, cisplatin, in particular, decreased mRNA expression of a number of transport proteins and reduced albumin uptake. It is known that cisplatin binds to megalin, preventing it from absorbing its ligands, which include albumin [

35]. This could explain the reduced albumin uptake we saw after cisplatin treatment. Other nephrotoxins, such as aristolochic acid, are also known to reduce the expression of megalin [

36]. To our knowledge, this has not yet been reported for cisplatin. However, the mechanism exerted by these toxins seems to be via upregulation of TNF-α [

36], which is also increased by cisplatin [

37]. Aquaporins, on the other hand, have been documented to be reduced in expression by cisplatin exposure, which we also observed, but the mechanism is not yet known for aquaporin-1 [

38,

39]. Cyclosporin A is also known to inhibit various transporters, among them the Mdr-1, peptide transporter-1 (Pept-1), organic anion transporters and sodium transporters [

40,

41,

42]. However, no change in the expression of these transporter molecules could be detected [

42,

43]. Other transporters, such as sodium transporters, are downregulated by cyclosporine A treatment

in vivo, but this is most likely related to a change in blood pressure [

44]. Regarding the impact of cyclosporin A on gene expression of other transporters, only indirect hints could be found: in rats with kidney transplants, several transporters (among them glucose transporter 3, sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter and nucleoside transporter 2) were lower expressed in the animals receiving cyclosporin A compared to the non-treated animals [

45]. No evidence of cyclosporin A reducing the expression of megalin could be found. Because the reduction in mRNA of megalin and cubilin was higher in cisplatin-treated cells than in cyclosporin A-treated cells, but albumin uptake was more impaired in the latter, loss of expression cannot be the only cause of reduced albumin uptake.

Overall, the differentiation protocol adapted from Kandasamy et al. [

13] resulted in cells that resemble proximal tubule cells not only morphologically but also in their mRNA and protein expression pattern. Of course, only part of the transcriptome was verified, but important PTEC markers could be found in the differentiated cells. Functional albumin transport was also detected. The sensitivity of the cells to cisplatin changed dramatically during differentiation, which was only partly due to the decrease in proliferation rate. In contrast, all cell stages were equally sensitive to cyclosporin A. In addition, treatment with the two toxins had an adverse effect on differentiation marker expression and albumin uptake functionality of the terminally differentiated cells.

The results shown here represent a first step towards a model that can be used in the future to investigate the influence of toxins on regeneration processes in the kidney. Cells in the differentiation process are at least as sensitive, if not more sensitive, to the known nephrotoxins used here as model substances, than the finally differentiated cells. This suggests a possible vulnerability of the newly forming cells in injured tubules, which may play a role in the observed loss of kidney function after AKI. This vulnerability has yet to be confirmed for other substances that may be present in the kidney during AKI.

Methods

Cell culture of RPTECs, F4-and b4-hiPSCs, and in vitro differentiation protocol

The human primary renal proximal tubular epithelial cell line (RPTEC-TERT1) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, USA) and expanded as described by [

46]. In brief, cells were grown into a 1:1 composition of DMEM with high glucose and Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMAX (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), 100 U/ml Pen/strep, 5 µg/ml insulin, 5 µg/ml transferrin, 5 ng/ml sodium selenite, 10 ng/ml EGF, and 36 ng/ml hydrocortisone (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). These cells were cultured and used until passage 10.

Foreskin-4 (F4)-human induced pluripotent stem cell line (further referred to as hiPSCs) was purchased from WiCell Stem Cell Bank (Madison, USA) at passage 29. These cells were generated from human foreskin fibroblasts through lentiviral transfection of OCT3/4, Sox2, Nanog, and Lin28 [

47]. b4-iPSC were generated from human foreskin fibroblasts by reprogramming with OCT3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-myc [

48]. Both hiPSC lines were routinely cultured on six-well plates coated with human embryonic stem cell qualified Matrigel for the F4 (Corning, New York, USA) and Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Matrix – Geltrex for the b4 (Gibco, New York, NY, USA) in mTeSR1 medium for the F4 (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and StemMacs medium for the b4 (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), supplemented with 10 mM Y-27632 dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) to keep them in exponential growth, and passaged twice a week at a ratio of 1:6 when cultures reached a confluency of 70-90 %. For differentiation into renal proximal tubular epithelial-like cells (PTELCs), a modified protocol, according to Kandasamy and colleagues [

13], was used as illustrated (Fig. 1A). Briefly, 3000 F4 cells/cm

2 or 750 b4 cells/cm

2 were seeded into 12-well plates coated with growth factor-reduced Matrigel (Corning, NY, USA) or Geltrex (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), respectively, in renal epithelial growth medium (REGM) containing various growth factors and supplements (REGM BulletKit, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) including 0.5% fetal bovine serum and 10 mM Y-27632 dihydrochloride. After 24 hours, the cells were switched to REGM differentiation medium without Y-27632 dihydrochloride but supplemented with 10 ng/ml of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and 2,5 ng/ml BMP7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and cultured under this condition for 9 days with a daily medium change to induce differentiation towards PTELC. hiPSC-derived PTELCs were either directly treated with nephrotoxic substances or harvested for further experiments on day 9.

Analysis of cell viability

After 24h treatment with vehicle controls (DMSO or basal medium) or with different concentrations of the model compounds cisplatin, a genotoxic nephrotoxin (Teva, Petach Tikva, Israel) and cyclosporin A, a non-genotoxic nephrotoxin (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), cell viability of undifferentiated, differentiating and differentiated cells was examined using the Alamar Blue Assay [

49], which measures the reduction of the blue and non-fluorescent resazurin dye (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) into pink and fluorescent resorufin by cell activity. Fluorescence intensity was measured in quadruplicates (excitation: 535 nm, emission: 590 nm on Tecan infinite 200, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Relative cell viability values were normalized to the respective vehicle controls and expressed as percentages.

Analysis of gene expression (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated and purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) and RNase-free DNase Set (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands), either manually or using the automated QIAcube (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). The RNA amount was quantified using the NanoVue Plus Spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, UK), stored at -80 °C, or immediately used for cDNA synthesis. cDNA was synthesized from 2000 ng RNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, CA, USA) in combination with the RiboLock Rnase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using the SensiMix SYBR Hi-ROX (C) Kit (Bioline GmbH, Luckenwalde, Germany) on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and analyzing the data was using the CFX Manager software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All samples were run with three technical replicates. The Cq values obtained for genes of interest were first normalized to the mean Cq values obtained for the housekeeping genes Act-β and Rpl-32 and then to the control samples and expressed as a fold of this mean value. Changes in gene expression of ≤0.5- and ≥2-fold were considered as biologically relevant. Gene-specific primer pairs used for amplification in this study (Supplement,

Table S1) were designed with the help of the NCBI (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/). These primer sets were tested and validated for specificity in a qPCR using different cDNA concentrations.

Immunofluorescence analysis

To monitor the expression of prototypical proximal tubular-related proteins, cells were fixed with 4% cold formaldehyde/PBS (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 15 min, washed with PBS, and permeabilized twice with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min at room temperature (RT). After blocking (5% BSA/PBS, 1 h, RT), incubation with primary antibodies in the dilution indicated in

Table S2 was performed at 4 °C overnight in a humid chamber. After washing with PBS, a fluorescence-labelled secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488/550 goat polyclonal to mouse or rabbit, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added and incubated in the dark (1:1000; 2 h). Nuclear DNA was stained with Vectashield containing DAPI (4′,6-diamidine-2-phenylindole, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Slides were sealed with nail polish and examined on a fluorescence microscope (BX43F Upright Microscope, Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot analysis

Cell extracts were prepared by lysis of cells in Roti-Load buffer (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) followed by heating (95 °C for 5 min). 25 μg of the isolated protein was separated by SDS-PAGE (10 to 12%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked at RT for 1 h (5% non-fat milk in TBS/0.1% Tween 20) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies in the dilution indicated in

Table S2. After washing the membrane with TBS/0.1% Tween 20, incubation with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) was performed (2 h at RT on a shaker). Finally, the membrane was visualized using the ChemiDox™ Touch Imaging System (BioRad, Munich, Germany).

Analysis of cell proliferation by measuring EdU incorporation

To monitor the rate of proliferation during the differentiation of hiPSCs into PTECs, the incorporation of fluorescent 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) into S-phase cells was analyzed using the EdU-Click-488 proliferation assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Baseclick GmbH, Tutzingen, Germany). Briefly, cells cultivated on coverslips were incubated with 10 µM EdU for 2 hours at 37°C. Then, a dye reaction cocktail conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 was added (30 min, RT in the dark), followed by washing with PBS and counterstaining the nuclei with DAPI. Finally, the percentage of EdU-positive cells was determined by fluorescence microscopy (BX43F Upright Microscope, Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan).

Flow cytometry-based quantitative detection of Aquaporin -1

Flow cytometric analysis was performed for quantitative detection of the PTEC marker aquaporin 1. After trypsinization, at least 1x106 cells were pelleted by centrifugation (400 ×g, 4 min, 4 °C) and treated with 0.5% Tween20 in PBS (RT, 15 min). After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in 3% BSA in PBS (RT; 15 min), followed by the addition of the primary antibody against aquaporin-1 (1:250). After washing twice with PBS, a fluorescently labelled secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, goat, polyclonal to mouse, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added (1:1000; 30 min). Quantification of cells expressing aquaporin-1 was performed by flow cytometric analysis (Becton Dickinson, Accuri™ C6 plus, Heidelberg, Germany).

Albumin uptake assay

The ability of PTEC to reabsorb albumin as a surrogate marker of their functionality was assessed by adding fluorescence labelled bovine serum albumin (BSA-FITC, 10 mg/ml) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to the culture medium. After 2 hours of incubation at 37°C, uptake was stopped with ice-cold PBS. At this point, cells were either detached with trypsin, fixed with 0.5% cold formaldehyde in PBS (15 min, RT) and analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Accuri™ C6 plus, Heidelberg, Germany) or fixed with 0.5% cold formaldehyde in PBS (15 min, RT) followed by counterstaining of cell nuclei and visualization by fluorescence microscopy (BX43F Upright Microscope, Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments (n=3). A comparison between the different sample groups was performed using Student's t-test (multiple-comparison test) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistically significant differences between groups were assumed at a p-value ≤0.05.

Figure 1.

Differentiation protocol and physiological changes provoked by it. (A) Scheme of the treatment of hiPSCs (Foreskin-4 (F4)- and b4-human induced pluripotent stem cells) adapted from the protocol of Kandasamy et al. [

13]. Morphological appearance of the F4-hiPSCs and cells on day 3 and day 9 (B) as well as of b4-hiPSCs and cells on day 3 and day 9 (C) of the differentiation process compared to a (D) commercially available proximal tubular cell line (RPTEC/TERT1). Reduction of proliferation after initiation of the differentiation process in F4- (E) and b4-hiPSC (F), quantified by incorporation of fluorescent 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) into S-phase cells. Shown is the mean % of proliferating cells of 3 independent experiments as well as representative pictures. ***p<0.001 vs. hiPSC, °°p<0.01, °°°p<0.001 vs. diffD3 (One-way ANOVA). The scale bars represent 50 µm. Yellow circles highlight dome-like, and yellow arrows, tubule-like patterns in the cell layers of the differentiated cells. BMP = bone morphogenetic protein, diffD = differentiation day, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent stem cells, PTELC = proximal tubular epithelial-like cells, REGM = renal epithelial cell growth medium, ROCK = rho-associated, coiled-coil-containing protein kinase.

Figure 1.

Differentiation protocol and physiological changes provoked by it. (A) Scheme of the treatment of hiPSCs (Foreskin-4 (F4)- and b4-human induced pluripotent stem cells) adapted from the protocol of Kandasamy et al. [

13]. Morphological appearance of the F4-hiPSCs and cells on day 3 and day 9 (B) as well as of b4-hiPSCs and cells on day 3 and day 9 (C) of the differentiation process compared to a (D) commercially available proximal tubular cell line (RPTEC/TERT1). Reduction of proliferation after initiation of the differentiation process in F4- (E) and b4-hiPSC (F), quantified by incorporation of fluorescent 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) into S-phase cells. Shown is the mean % of proliferating cells of 3 independent experiments as well as representative pictures. ***p<0.001 vs. hiPSC, °°p<0.01, °°°p<0.001 vs. diffD3 (One-way ANOVA). The scale bars represent 50 µm. Yellow circles highlight dome-like, and yellow arrows, tubule-like patterns in the cell layers of the differentiated cells. BMP = bone morphogenetic protein, diffD = differentiation day, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent stem cells, PTELC = proximal tubular epithelial-like cells, REGM = renal epithelial cell growth medium, ROCK = rho-associated, coiled-coil-containing protein kinase.

Figure 2.

Expression changes of differentiation markers in F4- and b4-hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubular epithelial cell-like cells (PTELC). (A) mRNA expression of stem cell, epithelial cell, and PTEC markers in differentiated F4- and b4hiPSC relative to expression in hiPSC analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Visualization of selected proteins by immunocytochemical staining on F4-hiPSC and F4 on differentiation day 9. Antibodies against the different markers are visualized with FITC-coupled secondary antibodies, and nuclei are stained with DAPI. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of the PTEC typical protein aquaporin-1 in F4-hiPSC and F4 on differentiation day 9. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR also included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean + SD. *p≤0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. hiPSCs (Student´s t-test). Aqp-1 = aquaporin-1, Cad-16 = cadherin 16, CD13 = alanyl aminopeptidase, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD = differentiation day, E-cad = E-cadherin, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, Gapdh = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, Glut-5 = fructose transporter 5, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cells, Nanog = homeobox protein, N-cad = N-cadherin, Oct-3/4 = octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4, PTEC = proximal tubular epithelial cell, Sox-2 = sex determining region Y-box 2, Uro-10 = urothelial glycoprotein, Zo-1 = zonula occludens 1.

Figure 2.

Expression changes of differentiation markers in F4- and b4-hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubular epithelial cell-like cells (PTELC). (A) mRNA expression of stem cell, epithelial cell, and PTEC markers in differentiated F4- and b4hiPSC relative to expression in hiPSC analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Visualization of selected proteins by immunocytochemical staining on F4-hiPSC and F4 on differentiation day 9. Antibodies against the different markers are visualized with FITC-coupled secondary antibodies, and nuclei are stained with DAPI. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of the PTEC typical protein aquaporin-1 in F4-hiPSC and F4 on differentiation day 9. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR also included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean + SD. *p≤0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. hiPSCs (Student´s t-test). Aqp-1 = aquaporin-1, Cad-16 = cadherin 16, CD13 = alanyl aminopeptidase, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD = differentiation day, E-cad = E-cadherin, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, Gapdh = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, Glut-5 = fructose transporter 5, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cells, Nanog = homeobox protein, N-cad = N-cadherin, Oct-3/4 = octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4, PTEC = proximal tubular epithelial cell, Sox-2 = sex determining region Y-box 2, Uro-10 = urothelial glycoprotein, Zo-1 = zonula occludens 1.

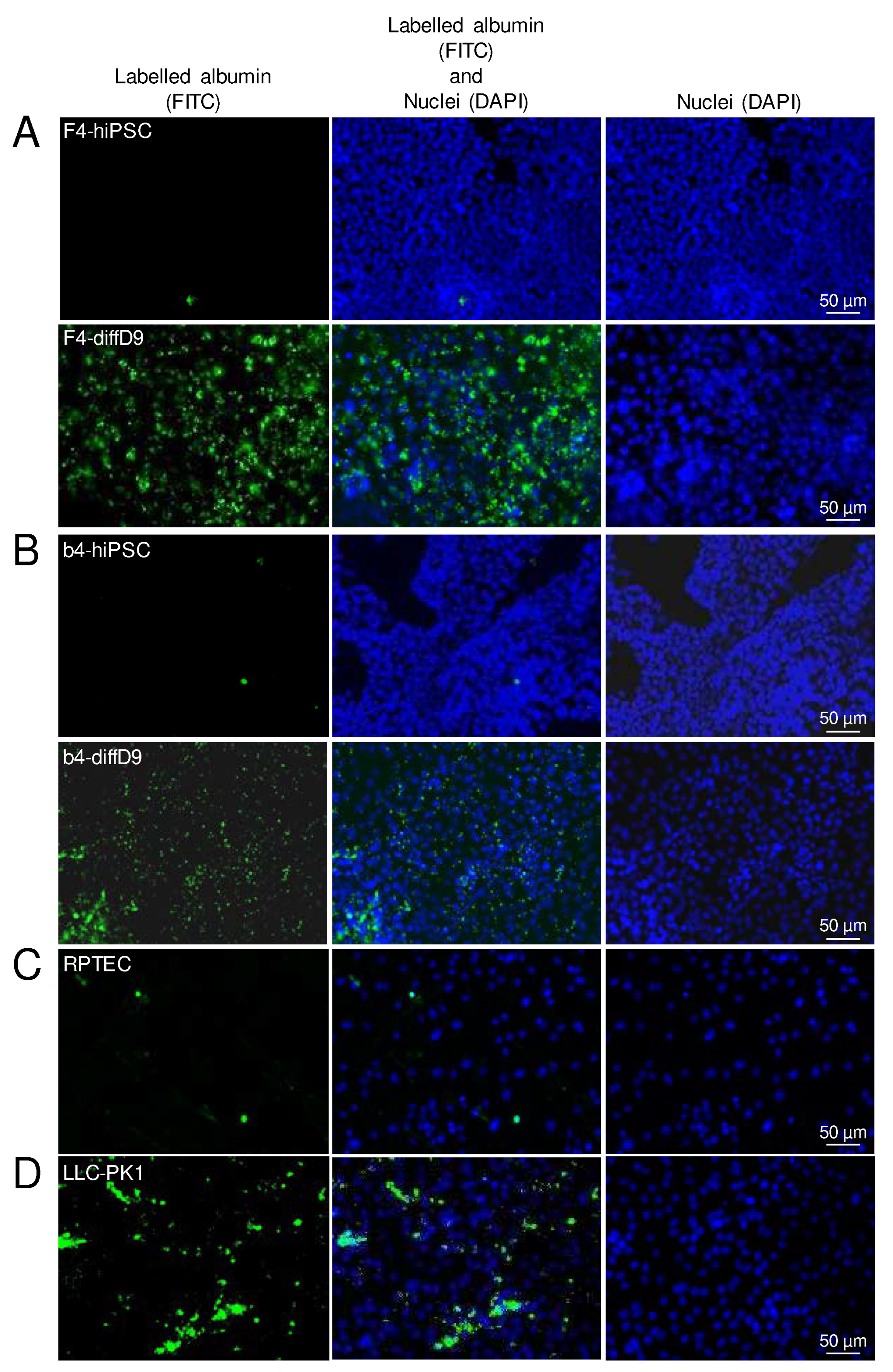

Figure 3.

Expression changes of functional proteins in hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubule epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells. (A) mRNA expression of PTEC transporters and transporters for cisplatin relative to expression in F4- (left) and b4- (right) hiPSC analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Expression of selected transporter proteins in F4 cells analyzed by Western blot. Shown are representative blots as well as their quantification. (C) Visualization of selected proteins by immunocytochemical staining on F4-hiPSC and F4 on differentiation day 9. Antibodies against the different markers are visualized with FITC-coupled secondary antibodies, and nuclei are stained with DAPI. (D) Analysis of albumin uptake into the differentiated F4- (above) and b4- (below) cells with the help of FITC-labelled albumin. Shown are representative pictures, and for F4, the flow cytometric quantification. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR also included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean ± SD. ***p<0.001 vs. hiPSCs (Student´s t-test). Ctr-1/2 = copper transporter 1/2, Cubn = cubilin, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, Mdr-1 = multidrug resistance protein 1, Meg = megalin, Oat-1/3 = organic anion transporter 1, Oct-2 = organic cation transporter 2, Octn-2 = organic cation/carnitine transporter 2, Pept-1/2 = peptide transporter 1/2, Sglt-2 = sodium/glucose cotransporter 2.

Figure 3.

Expression changes of functional proteins in hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubule epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells. (A) mRNA expression of PTEC transporters and transporters for cisplatin relative to expression in F4- (left) and b4- (right) hiPSC analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Expression of selected transporter proteins in F4 cells analyzed by Western blot. Shown are representative blots as well as their quantification. (C) Visualization of selected proteins by immunocytochemical staining on F4-hiPSC and F4 on differentiation day 9. Antibodies against the different markers are visualized with FITC-coupled secondary antibodies, and nuclei are stained with DAPI. (D) Analysis of albumin uptake into the differentiated F4- (above) and b4- (below) cells with the help of FITC-labelled albumin. Shown are representative pictures, and for F4, the flow cytometric quantification. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR also included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean ± SD. ***p<0.001 vs. hiPSCs (Student´s t-test). Ctr-1/2 = copper transporter 1/2, Cubn = cubilin, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, Mdr-1 = multidrug resistance protein 1, Meg = megalin, Oat-1/3 = organic anion transporter 1, Oct-2 = organic cation transporter 2, Octn-2 = organic cation/carnitine transporter 2, Pept-1/2 = peptide transporter 1/2, Sglt-2 = sodium/glucose cotransporter 2.

Figure 4.

Gain of functional albumin transport in hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubule epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells. Analysis of albumin uptake into the undifferentiated and differentiated F4- (A) and b4- (B) cells, as well as in RPTEC- (C) and LLC-PK1 (D) cells with the help of FITC-labelled BSA. Shown are representative pictures. BSA = bovine serum albumin, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, RPTEC = renal proximal tubule epithelial cells.

Figure 4.

Gain of functional albumin transport in hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubule epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells. Analysis of albumin uptake into the undifferentiated and differentiated F4- (A) and b4- (B) cells, as well as in RPTEC- (C) and LLC-PK1 (D) cells with the help of FITC-labelled BSA. Shown are representative pictures. BSA = bovine serum albumin, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, RPTEC = renal proximal tubule epithelial cells.

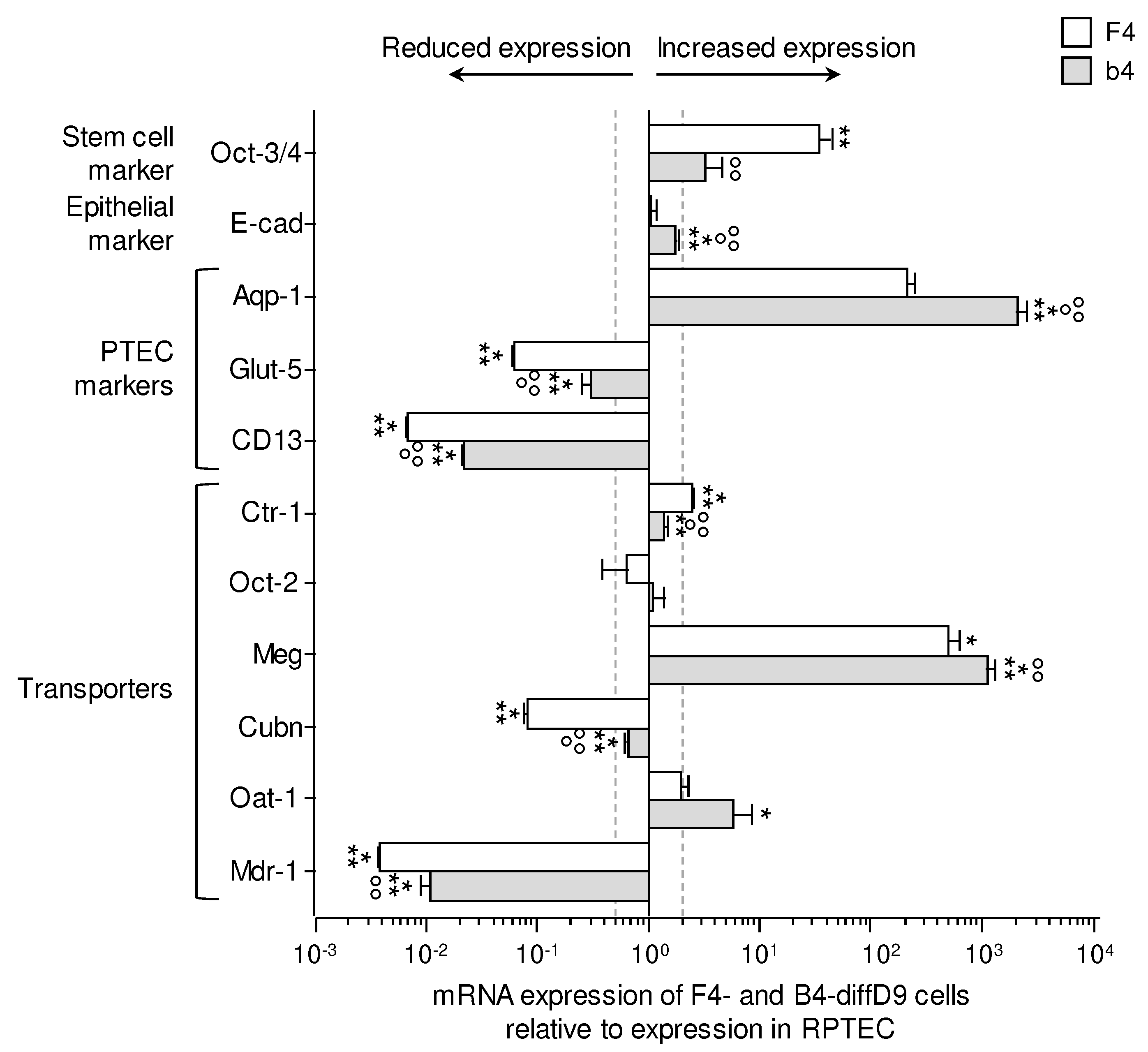

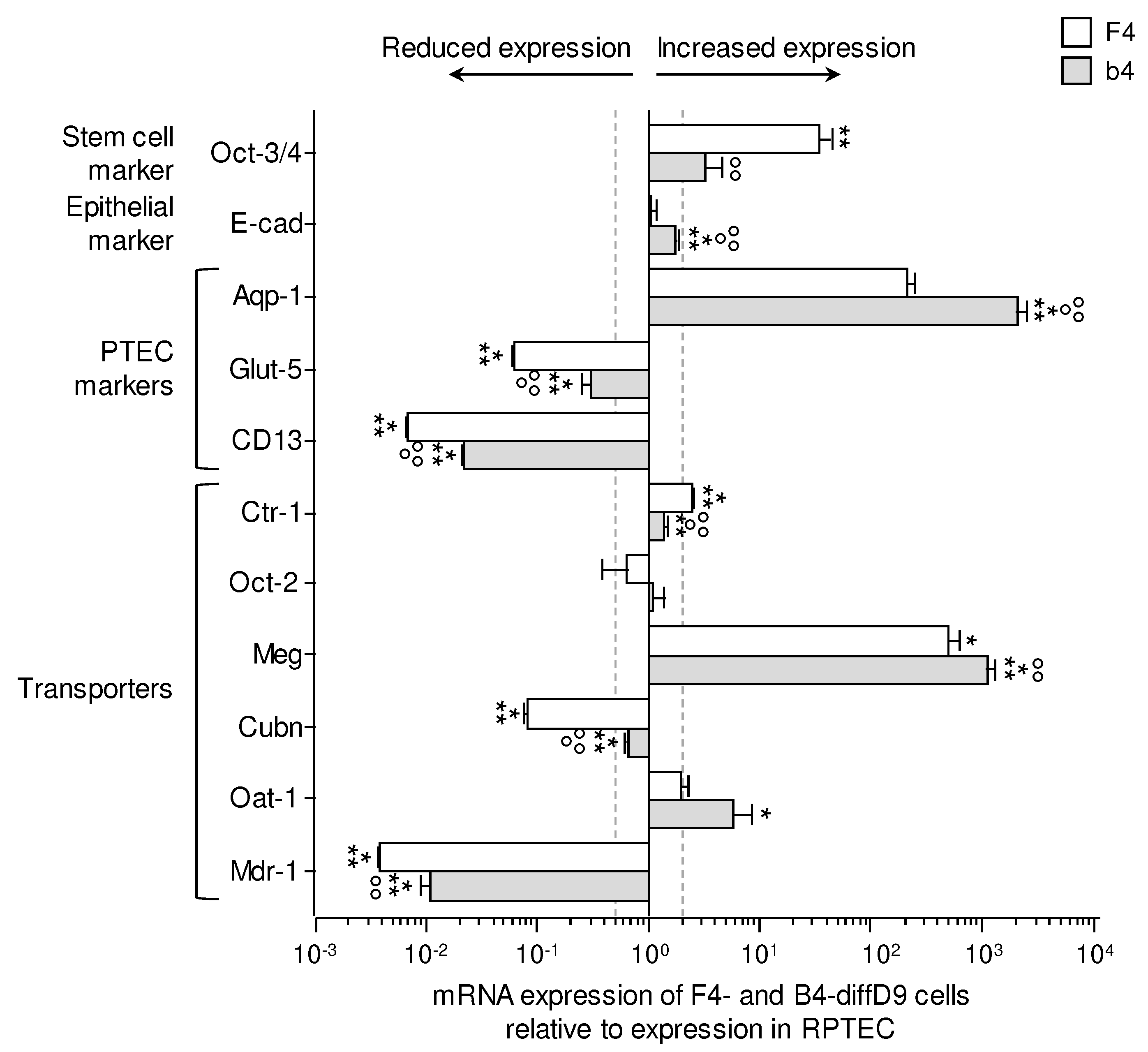

Figure 5.

Expression changes of selected genes in F4- and b4-hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubular epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells compared to the expression in a commercial renal proximal tubule epithelial kidney cell line (RPTEC/TERT1). mRNA expression of a stem cell marker, an epithelial marker, several PTEC markers, and transporters relative to expression in RPTEC/TERT1 were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR also included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean ± SD. *p≤0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. RPTEC/TERT1 (ANOVA). BSA = bovine serum albumin, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell. Aqp-1 = aquaporin-1, CD13 = alanyl aminopeptidase, Ctr-1 = copper transporter 1, Cubn = cubilin, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, E-cad = E-cadherin, Glut-5 = fructose transporter 5, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, Meg = megalin, Oct-3/4 = octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4, P-gp = P-glycoprotein, RPTEC = renal proximal tubule epithelial cells.

Figure 5.

Expression changes of selected genes in F4- and b4-hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubular epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells compared to the expression in a commercial renal proximal tubule epithelial kidney cell line (RPTEC/TERT1). mRNA expression of a stem cell marker, an epithelial marker, several PTEC markers, and transporters relative to expression in RPTEC/TERT1 were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR also included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean ± SD. *p≤0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. RPTEC/TERT1 (ANOVA). BSA = bovine serum albumin, DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, FITC = fluorescein isothiocyanate, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell. Aqp-1 = aquaporin-1, CD13 = alanyl aminopeptidase, Ctr-1 = copper transporter 1, Cubn = cubilin, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, E-cad = E-cadherin, Glut-5 = fructose transporter 5, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, Meg = megalin, Oct-3/4 = octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4, P-gp = P-glycoprotein, RPTEC = renal proximal tubule epithelial cells.

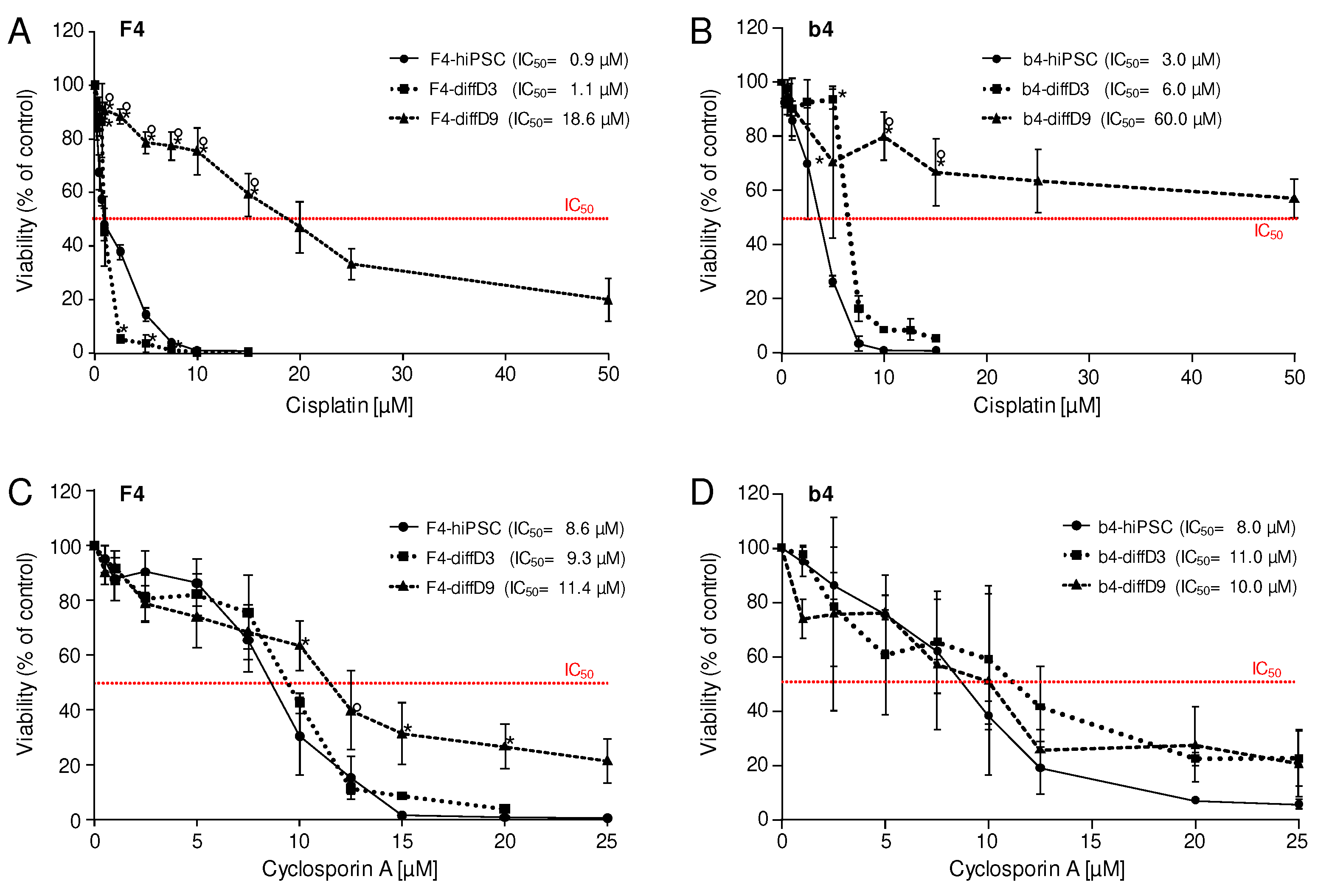

Figure 6.

Sensitivities of hiPSCs and cells on differentiation days 3 and 9 towards selected nephrotoxins. Cell viability was measured with the Alamar Blue assay on F4- (A and C) and b4- (B and D) cells of differentiation days 0 (hiPSC), 3 (diffD3) and, 9 (diffD9) after 24 h treatment with (A and B) cisplatin, (C and D) cyclosporin A, in the indicated concentrations. The concentrations at which 50 % of the cells were dead are given as IC50 values in the graphs. Data from at least 3 independent experiments are shown as mean ± SD. *p≤0.05 vs. hiPSC, °p≤0.05 vs. diffD3 (One-way ANOVA).

Figure 6.

Sensitivities of hiPSCs and cells on differentiation days 3 and 9 towards selected nephrotoxins. Cell viability was measured with the Alamar Blue assay on F4- (A and C) and b4- (B and D) cells of differentiation days 0 (hiPSC), 3 (diffD3) and, 9 (diffD9) after 24 h treatment with (A and B) cisplatin, (C and D) cyclosporin A, in the indicated concentrations. The concentrations at which 50 % of the cells were dead are given as IC50 values in the graphs. Data from at least 3 independent experiments are shown as mean ± SD. *p≤0.05 vs. hiPSC, °p≤0.05 vs. diffD3 (One-way ANOVA).

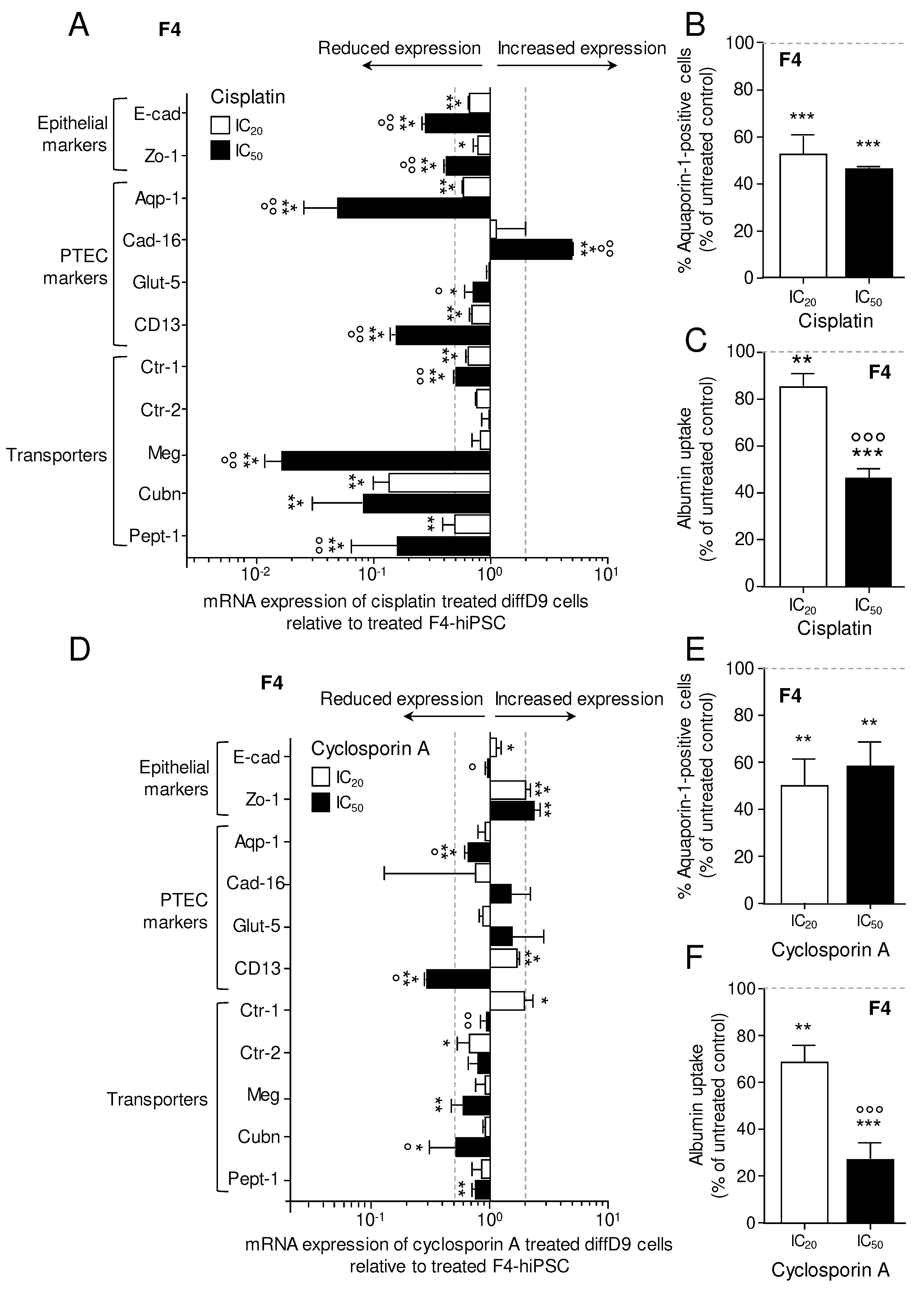

Figure 7.

Effects of cisplatin and cyclosporin A on marker gene expression and transport function in F4-hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubular epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells. mRNA expression of marker genes in diffD9 F4 cells after 24 h treatment with the IC20 and IC50 concentrations of cisplatin (A) and cyclosporin A (D) relative to their expression in F4-hiPSC analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Flow cytometry analysis of the PTEC typical protein aquaporin-1 in diffD9 F4 cells treated 24 h with the IC20 and IC50 concentrations of cisplatin (B) and cyclosporin A (E). Flow cytometric analysis of albumin uptake into diffD9 F4 cells after 24 h treatment with the IC20 and IC50 concentrations of cisplatin (C) and cyclosporin A (F) with the help of FITC-labelled albumin. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean + SD. *p≤0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. treated F4-hiPSCs, °°°p<0.001 vs. diffD9 cells treated with IC20 (ANOVA). Aqp-1 = aquaporin-1, Cad-16 = cadherin 16, CD13 = alanyl aminopeptidase, Ctr-1/2 = copper transporter 1/2, Cubn = cubilin, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, E-cad = E-cadherin, Glut-5 = fructose transporter 5, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, Meg = megalin, Pept-1 = peptide transporter 1, Zo-1 = zonula occludens 1.

Figure 7.

Effects of cisplatin and cyclosporin A on marker gene expression and transport function in F4-hiPSC differentiated into proximal tubular epithelial cell (PTEC)-like cells. mRNA expression of marker genes in diffD9 F4 cells after 24 h treatment with the IC20 and IC50 concentrations of cisplatin (A) and cyclosporin A (D) relative to their expression in F4-hiPSC analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Flow cytometry analysis of the PTEC typical protein aquaporin-1 in diffD9 F4 cells treated 24 h with the IC20 and IC50 concentrations of cisplatin (B) and cyclosporin A (E). Flow cytometric analysis of albumin uptake into diffD9 F4 cells after 24 h treatment with the IC20 and IC50 concentrations of cisplatin (C) and cyclosporin A (F) with the help of FITC-labelled albumin. Data from at least 3 independent experiments (qPCR included 3 technical replicates) are shown as mean + SD. *p≤0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. treated F4-hiPSCs, °°°p<0.001 vs. diffD9 cells treated with IC20 (ANOVA). Aqp-1 = aquaporin-1, Cad-16 = cadherin 16, CD13 = alanyl aminopeptidase, Ctr-1/2 = copper transporter 1/2, Cubn = cubilin, diffD9 = differentiation day 9, E-cad = E-cadherin, Glut-5 = fructose transporter 5, hiPSC = human induced pluripotent cell, Meg = megalin, Pept-1 = peptide transporter 1, Zo-1 = zonula occludens 1.