Submitted:

21 November 2023

Posted:

23 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Study Design and Sample Size

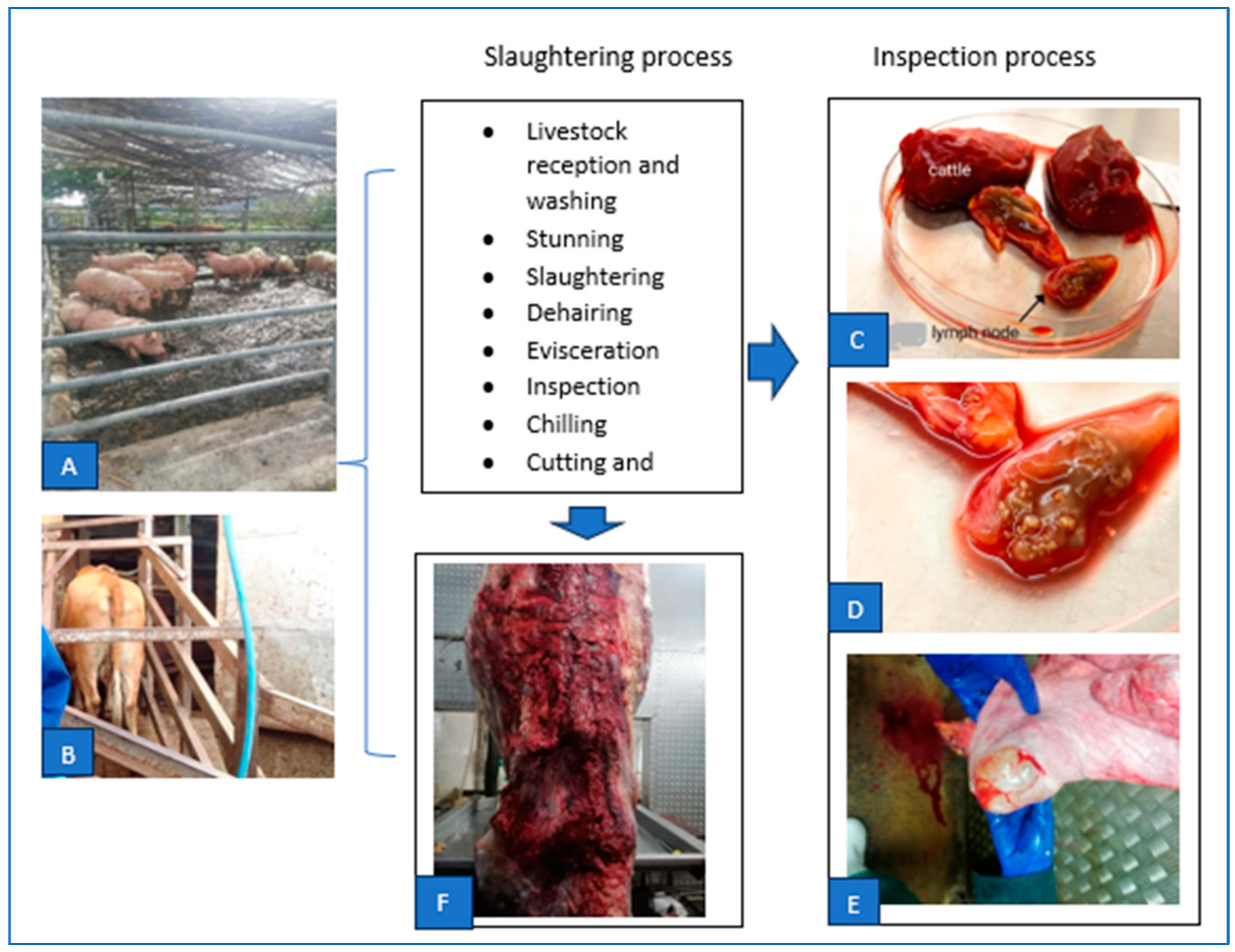

2.3. Samples Collection Procedure

2.4. Sample Processing

2.5. Genomic DNA Extraction

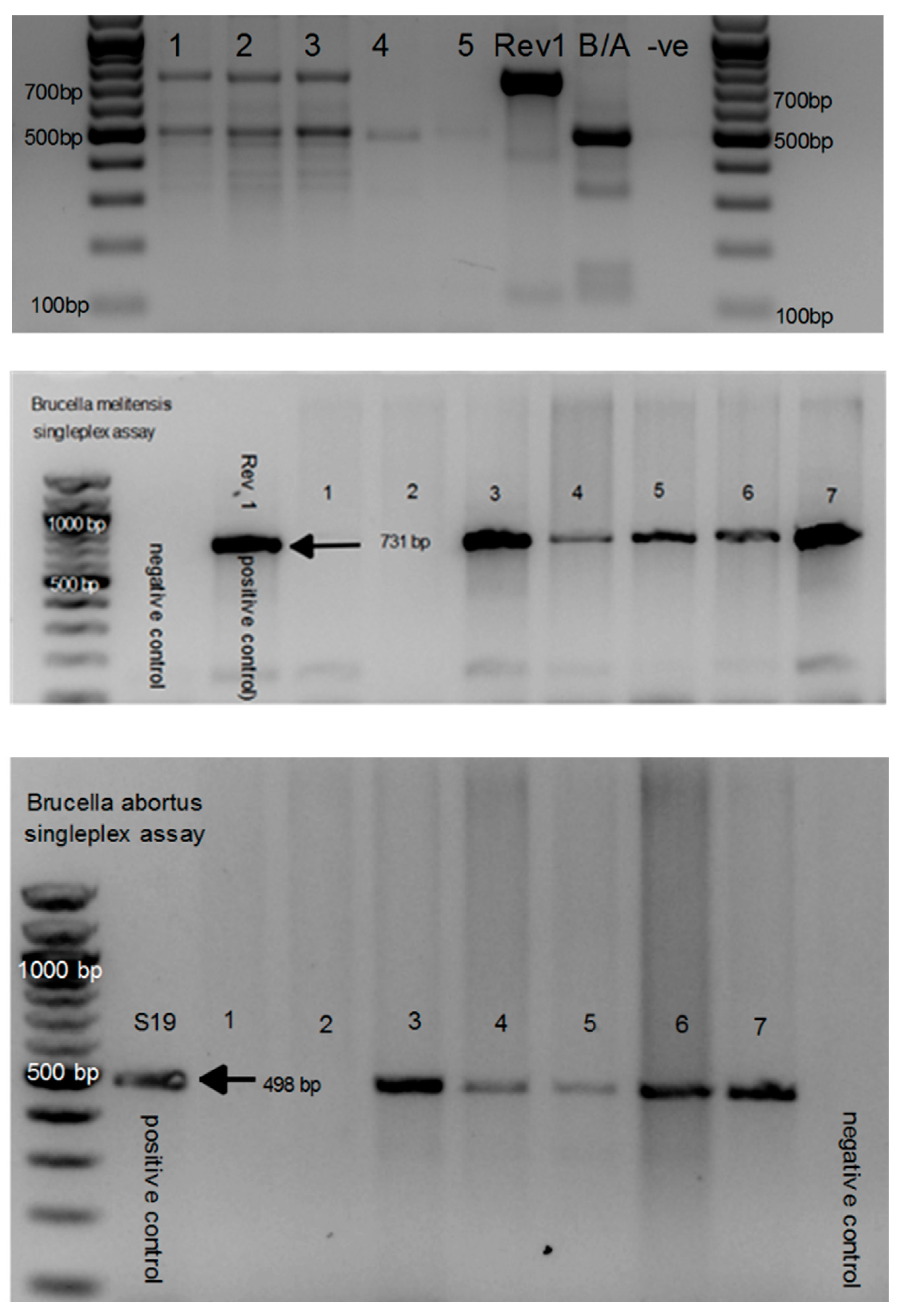

2.6. Brucella Genus PCR Screening Using ITS

2.7. Sample Preparations and Brucella Culture

2.8. Bacteriological Examination

2.9. Identification of Fast-Growing Contaminants

2.10. AMOS-PCR and Bruce-Ladder PCR Assays

2.11. Statistical Analysis

2.12. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Brucella spp. Directly from the Tissues Using 16S-23S Ribosomal DNA Interspacer Region (ITS) PCR Assay

3.2. Identification of Gram-Negative Isolates Using Gram Staining

3.3. Characterisation of Brucella spp. Using AMOS PCR Assay and Seropositivity

3.4. Brucella Isolation amongst Livestock Stratified by Tissue

3.5. Association between Brucella ITS-PCR Positivity and Predictor Variables

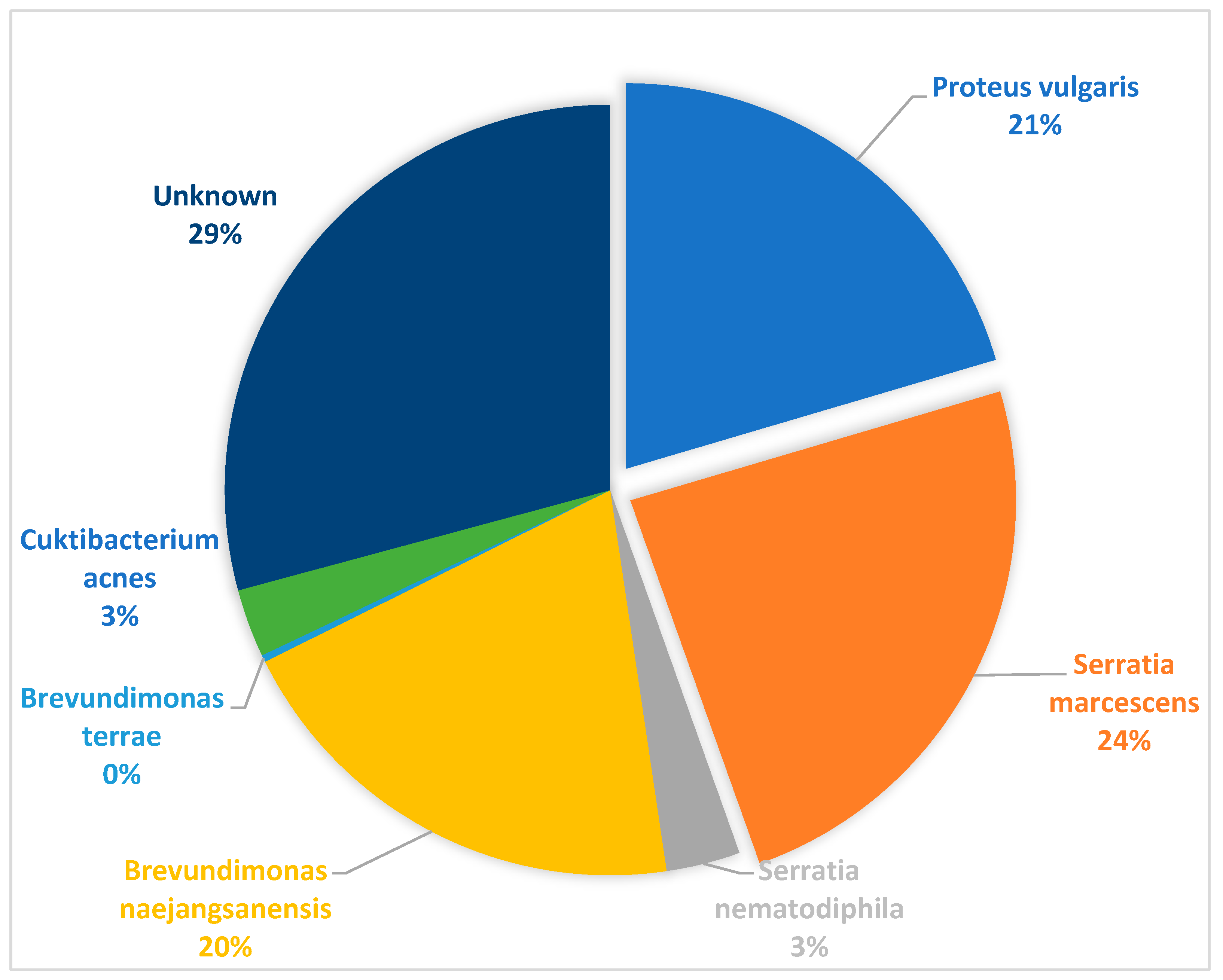

3.6. Sequence Identification of Additional Gram-Negative and Positive Isolates from Culture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

6. Limitations of the study

Supplementary Materials

Declaration of interest

Ethics statement

Role funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Foster G, Osterman BS, Godfroid J, Jacques I, Cloeckaert A. Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology. 2007, 57, 2688–2693.

- Seleem MN, Boyle SM, Sriranganathan N. Brucellosis: a re-emerging zoonosis. Veterinary microbiology. 2010, 140, 392–398.

- Eiken, M. Studies on an anaerobic rod-shaped. Gram-negative microorganism: Bacteroides corro. 1958.

- Deng Y, Liu X, Duan K, Peng Q. Research progress on brucellosis. Current medicinal chemistry. 2019, 26, 5598–5608.

- Ilhan Z, Aksakal A, Ekin I, Gülhan T, Solmaz H, Erdenlig S. Comparison of culture and PCR for the detection of Brucella melitensis in blood and lymphoid tissues of serologically positive and negative slaughtered sheep. Letters in applied microbiology. 2008, 46, 301–306.

- Poester F, Samartino L, Santos R. Pathogenesis and pathobiology of brucellosis in livestock. Rev Sci Tech. 2013, 32, 105–115.

- Megid J, Mathias LA, Robles C. Clinical manifestations of brucellosis in domestic animals and humans. The Open Veterinary Science Journal. 2010, 119–126.

- González-Espinoza G, Arce-Gorvel V, Mémet S, Gorvel J-P. Brucella: Reservoirs and niches in animals and humans. Pathogens. 2021, 10, 186.

- Levin BR, Baquero F, Ankomah PP, McCall IC. Phagocytes, antibiotics, and self-limiting bacterial infections. Trends in microbiology. 2017, 25, 878–892.

- Barquero-Calvo E, Chaves-Olarte E, Weiss DS, Guzman-Verri C, Chacon-Diaz C, Rucavado A, et al. Brucella abortus uses a stealthy strategy to avoid activation of the innate immune system during the onset of infection. PloS one. 2007, 2, e631.

- Rahman MS, Hahsin MFA, Ahasan MS, Her M, Kim JY, Kang SI, et al. Brucellosis in sheep and goat of Bogra and Mymensingh districts of Bangladesh. Korean Journal of Veterinary Research. 2011, 51, 277–280.

- Goswami A, Sharma PR, Agarwal R. Combatting intracellular pathogens using bacteriophage delivery. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2021, 47, 461–478.

- Detilleux P, Cheville N, Deyoe B. Pathogenesis of Brucella abortus in chicken embryos. Veterinary Pathology. 1988, 25, 138–146.

- Pappas G, Papadimitriou P, Akritidis N, Christou L, Tsianos EV. The new global map of human brucellosis. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2006, 6, 91–99.

- Shirima G, Fitzpatrick J, Kunda J, Mfinanga G, Kazwala R, Kambarage D, et al. The role of livestock keeping in human brucellosis trends in livestock keeping communities in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research. 2010, 12, 203–207.

- Navarro E, Casao MA, Solera J. Diagnosis of human brucellosis using PCR. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2004, 4, 115–123.

- Sofos, JN. Challenges to meat safety in the 21st century. Meat science. 2008, 78, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsak N, Daube G, Ghafir Y, Chahed A, Jolly S, Vindevogel H. An efficient sampling technique used to detect four foodborne pathogens on pork and beef carcasses in nine Belgian abattoirs. Journal of Food Protection. 1998, 61, 535–541.

- Lopez-Goñi I, Garcia-Yoldi D, Marín C, De Miguel M, Munoz P, Blasco J, et al. Evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay (Bruce-ladder) for molecular typing of all Brucella species, including the vaccine strains. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2008, 46, 3484–3487.

- Le Flèche P, Jacques I, Grayon M, Al Dahouk S, Bouchon P, Denoeud F, et al. Evaluation and selection of tandem repeat loci for a Brucella MLVA typing assay. BMC microbiology. 2006, 6, 1–14.

- Probert WS, Schrader KN, Khuong NY, Bystrom SL, Graves MH. Real-time multiplex PCR assay for detection of Brucella spp., B. abortus, and B. melitensis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004, 42, 1290–1293.

- Bricker BJ, Halling SM. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1994, 32, 2660–2666.

- De Miguel M, Marín CM, Muñoz PM, Dieste L, Grilló MJ, Blasco JM. Development of a selective culture medium for primary isolation of the main Brucella species. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011, 49, 1458–1463.

- Nielsen, K. Diagnosis of brucellosis by serology. Veterinary microbiology. 2002, 90, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott JJ, Arimi S. Brucellosis in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiology, control and impact. Veterinary microbiology. 2002, 90, 111–134.

- Yu WL, Nielsen K. Review of detection of Brucella spp. by polymerase chain reaction. Croatian medical journal. 2010, 51, 306–313.

- Barbuddhe SB, Vergis J, Rawool DB. Immunodetection of bacteria causing brucellosis. Methods in Microbiology. 47: Elsevier; 2020. p. 75-115.

- Shome R, Kalleshamurthy T, Rathore Y, Ramanjinappa KD, Skariah S, Nagaraj C, et al. Spatial sero-prevalence of brucellosis in small ruminants of India: Nationwide cross-sectional study for the year 2017–2018. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2021, 68, 2199–2208.

- Al Dahouk S, Sprague L, Neubauer H. New developments in the diagnostic procedures for zoonotic brucellosis in humans. Rev Sci Tech. 2013, 32, 177–188.

- Zinsstag J SE, Solera J, Blasco JM, Moriyón I. Brucellosis. In: Palmer SR, Soulsby L, Torgeson PR, Brown DG. Handbook of zoonoses. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press2011. p. 54-62 p.

- Musallam I, Abo-Shehada M, Omar M, Guitian J. Cross-sectional study of brucellosis in Jordan: prevalence, risk factors and spatial distribution in small ruminants and cattle. Preventive veterinary medicine. 2015, 118, 387–396.

- Schrire, L. Human brucellosis in South Africa. South African Medical Journal. 1962, 36, 342–349. [Google Scholar]

- Van Drimmelen, G. A urease test for characterizing Brucella strains. 1962.

- Tempia S, Mayet N, Gerstenberg C, Cloete A. Brucellosis knowledge, attitudes and practices of a South African communal cattle keeper group. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 2019, 86, 1–10.

- Govindasamy K, Etter EM, Geertsma P, Thompson PN. Progressive area elimination of bovine brucellosis, 2013–2018, in Gauteng Province, South Africa: Evaluation using laboratory test reports. Pathogens. 2021, 10, 1595.

- Simpson GJ, Marcotty T, Rouille E, Chilundo A, Letteson J-J, Godfroid J. Immunological response to Brucella abortus strain 19 vaccination of cattle in a communal area in South Africa. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 2018, 89, 1–7.

- Kolo FB, Adesiyun AA, Fasina FO, Potts A, Dogonyaro BB, Katsande CT, et al. A retrospective study (2007–2015) on brucellosis seropositivity in livestock in South Africa. Veterinary medicine and science. 2021, 7, 348–356.

- Goni S, Skenjana A, Nyangiwe N. The status of livestock production in communal farming areas of the Eastern Cape: A case of Majali Community, Peelton. Appl Anim Husb Rural Dev. 2018, 11, 34–40.

- Agriculture WCDo. Animal health and disease control 2023 (Available from: https://www.elsenburg.com/veterinary-services/animal-health-and-disease-control/.

- Langoni H, Ichihara SM, SILVA AVd, Pardo RB, Tonin FB, Mendonça LJP, et al. Isolation of Brucella spp from milk of brucellosis positive cows in São Paulo and Minas Gerais states. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science. 2000, 37, 444–448.

- Mazwi K, Kolo F, Jaja I, Byaruhanga C, Hassim A, Heerden Hv. Serological Evidence and Co-Exposure of Selected Infections Among Livestock Slaughtered at Eastern Cape Abattoirs in South Africa International Journal of Microbiology. 2023.

- Keid LB, Soares RM, Vasconcellos SA, Chiebao D, Salgado V, Megid J, et al. A polymerase chain reaction for detection of Brucella canis in vaginal swabs of naturally infected bitches. Theriogenology. 2007, 68, 1260–1270.

- Ledwaba MB, Matle I, Van Heerden H, Ndumnego OC, Gelaw AK. Investigating selective media for optimal isolation of Brucella spp. in South Africa. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 2020, 87, 1–9.

- Tripathi N, Sapra A. Gram staining. 2020.

- Weiner M, Iwaniak W, Szulowski K. Comparison of PCR-based AMOS, Bruce-Ladder and MLVA assays for typing of Brucella species. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2011, 55, 625–630.

- Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (No Title). 2010.

- Hosein H, El-Nahass E, Rouby S, El-Nesr K. Detection of Brucella in tissues and in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens using PCR. Adv Anim Vet Sci. 2018, 6, 55–62.

- Spickler, AR. Brucellosis: Canine Brucellosis. The Center for Food Security and Public Health. 2018.

- El-Diasty M, Wareth G, Melzer F, Mustafa S, Sprague LD, Neubauer H. Isolation of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis from seronegative cows is a serious impediment in brucellosis control. Veterinary Sciences. 2018, 5, 28.

- Nielsen K, Yu W. Serological diagnosis of brucellosis. Prilozi. 2010, 31, 65–89.

- Corner L, Alton G, McNichol L, Streeten T, Trueman K. An evaluation of the anamnestic test for brucellosis in cattle of the northern pastoral area. Australian Veterinary Journal. 1983, 60, 1–3.

- Tekle M, Legesse M, Edao BM, Ameni G, Mamo G. Isolation and identification of Brucella melitensis using bacteriological and molecular tools from aborted goats in the Afar region of north-eastern Ethiopia. BMC microbiology. 2019, 19, 1–6.

- Mendoza-Roldan JA, Noll Louzada-Flores V, Lekouch N, Khouchfi I, Annoscia G, Zatelli A, et al. Snakes and Souks: Zoonotic pathogens associated to reptiles in the Marrakech markets, Morocco. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2023, 17, e0011431.

- Friman MJ, Eklund MH, Pitkälä AH, Rajala-Schultz PJ, Rantala MHJ. Description of two Serratia marcescens associated mastitis outbreaks in Finnish dairy farms and a review of literature. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 2019, 61, 1–11.

- Das A, Paranjape V, Pitt T. Serratia marcescens infection associated with early abortion in cows and buffaloes. Epidemiology & Infection. 1988, 101, 143–149.

- Kang S-J, Choi N-S, Choi JH, Lee J-S, Yoon J-H, Song JJ. Brevundimonas naejangsanensis sp. nov., a proteolytic bacterium isolated from soil, and reclassification of Mycoplana bullata into the genus Brevundimonas as Brevundimonas bullata comb. nov. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology. 2009, 59, 3155–3160.

- Riedel J, Halm U, Prause C, Vollrath F, Friedrich N, Weidel A, et al. Multilocular hepatic masses due to Enterobius vermicularis. Innere Medizin (Heidelberg, Germany). 2023.

- Wardhana, DK. Risk factors for bacterial contamination of bovine meat during slaughter in ten Indonesian abattoirs. Veterinary medicine international. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bhembe NL, Jaja IF, Nwodo UU, Okoh AI, Green E. Prevalence of tuberculous lymphadenitis in slaughtered cattle in Eastern Cape, South Africa. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2017, 61, 27–37.

- Nagaraja T, Lechtenberg KF. Liver abscesses in feedlot cattle. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice. 2007, 23, 351–369.

- Jaja IF, Mushonga B, Green E, Muchenje V. Factors responsible for the post-slaughter loss of carcass and offal’s in abattoirs in South Africa. Acta tropica. 2018, 178, 303–310.

- Bosman, P. Scheme for the control and eventual eradication of bovine brucellosis (author's transl). Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 1980, 51, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matle I, Ledwaba B, Madiba K, Makhado L, Jambwa K, Ntushelo N. Characterisation of Brucella species and biovars in South Africa between 2008 and 2018 using laboratory diagnostic data. Veterinary Medicine and Science. 2021, 7, 1245–1253.

- Kolo FB, Adesiyun AA, Fasina FO, Katsande CT, Dogonyaro BB, Potts A, et al. Seroprevalence and characterization of Brucella species in cattle slaughtered at Gauteng abattoirs, South Africa. Veterinary Medicine and Science. 2019, 5, 545–555.

- Govindasamy, K. Human brucellosis in South Africa: A review for medical practitioners. South African Medical Journal. 2020, 110, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Massis F, Zilli K, Di Donato G, Nuvoloni R, Pelini S, Sacchini L, et al. Distribution of Brucella field strains isolated from livestock, wildlife populations, and humans in Italy from 2007 to 2015. PloS one. 2019, 14, e0213689.

- Frean J, Cloete A, Rossouw J, Blumberg L.. Brucellosis in South Africa–A notifiable medical condition. NICD Communicable Diseases Communique. 2018, 16, 110–117.

- Caine L-A, Nwodo UU, Okoh AI, Green E. Molecular characterization of Brucella species in cattle, sheep and goats obtained from selected municipalities in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2017, 7, 293–298.

- Godfroid J, Al Dahouk S, Pappas G, Roth F, Matope G, Muma J, et al. A “One Health” surveillance and control of brucellosis in developing countries: moving away from improvisation. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases. 2013, 36, 241–248.

- Health WOfA. Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals. Infect Bursal Dis. 2012;12:549-65.

- Zhang N, Huang D, Wu W, Liu J, Liang F, Zhou B, et al. Animal brucellosis control or eradication programs worldwide: a systematic review of experiences and lessons learned. Preventive veterinary medicine. 2018, 160, 105–115.

| Species | ITS-PCR positive animals (%) | Culture AMOS-PCR animals (%) |

Culture positive animals identified with AMOS-PCR from ITS-PCR positive tissue (%) |

Number positive tissues per animal species |

Sero-negative (RBT, CFT & iELISA) and culture positive animals |

Brucella culture and sero-positive animals | |||||||

| Liver | Spleen | Kidney | Lymph nodes | Tonsils | RBT | ELISA | RBT and iELISA | RBT, iELISA & CFT | |||||

| Cattle | 94/280 (33.6%) | 41/280 (14.6%) |

41/94 (43.6%) |

25/94 (26.6%) |

20/94 (21.3%) |

19/94 (20.2%) |

31/94 (33.0%) |

10/94 (10.6%) |

31/41 (76.6%) |

7/41 (17.1%) |

4/41 (9.8%) |

2/41 (4.9%) |

1/41 (2.4%) |

| Sheep | 29/200 (14.5%) |

15/200 (7.5%) |

15/29 (51.7%) |

11/29 (37.9%) |

10/29 (34.5%) |

11/29 (37.9%) |

8/29 (25.6%) |

- |

13/15 (86.7%) |

2/15 (13.3%) |

0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 |

| Pigs | 4/85 (4.7%) |

2/85 (2.4%) |

2/4 (50.0%) |

0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 2/4 50.0%) |

2/2 (100%) |

0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 |

| Variable | Level | Number of animals positive for Brucella spp. (%) | p-value |

| Abattoir | <0.0001 | ||

| Abattoir A (n=50) | 19 (38.0) | ||

| Abattoir B (n=344) | 48 (14.2) | ||

| Abattoir C (n=45) | 7 (15.6) | ||

| Abattoir D (n=23) | 9 (39.1) | ||

| Abattoir E (n=103) | 43 (41.7) | ||

| Throughput | 0.05078 | ||

| High (n=542) | 118 (21.8) | ||

| Low (n=23) | 9 (39.1) | ||

| Animal species | <0.0001 | ||

| Cattle (n=280) | 94 (33.6) | ||

| Pig (n=85) | 4 (4.7) | ||

| Sheep (n=200) | 29 (14.5) | ||

| Sex | Female (n=276) | 66 (23.9) | 0.4245 |

| Male (n=289) | 61 (21.1) |

| Variable | Category | Odds ratio (CI) | p-value |

| Abattoir | Abattoir B (ref) | ||

| Abattoir A | 4.89 (2.26, 10.57) | <0.0001 | |

| Abattoir C | 0.91 (0.36, 2.30) | 0.8495 | |

| Abattoir D | 7.02 (2.57, 19.15) | 0.000142 | |

| Abattoir E | 5.13 (2.92, 8.99) | <0.0001 | |

| Species | |||

| Pig (ref) | |||

| Cattle | 17.09 (5.66, 51.61) | <0.0001 | |

| Sheep | 5.59 (1.71,18.29) | 0.0043 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | |||

| Female | 0.54 (0.33, 0.89) | 0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).