Submitted:

21 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Basic concepts

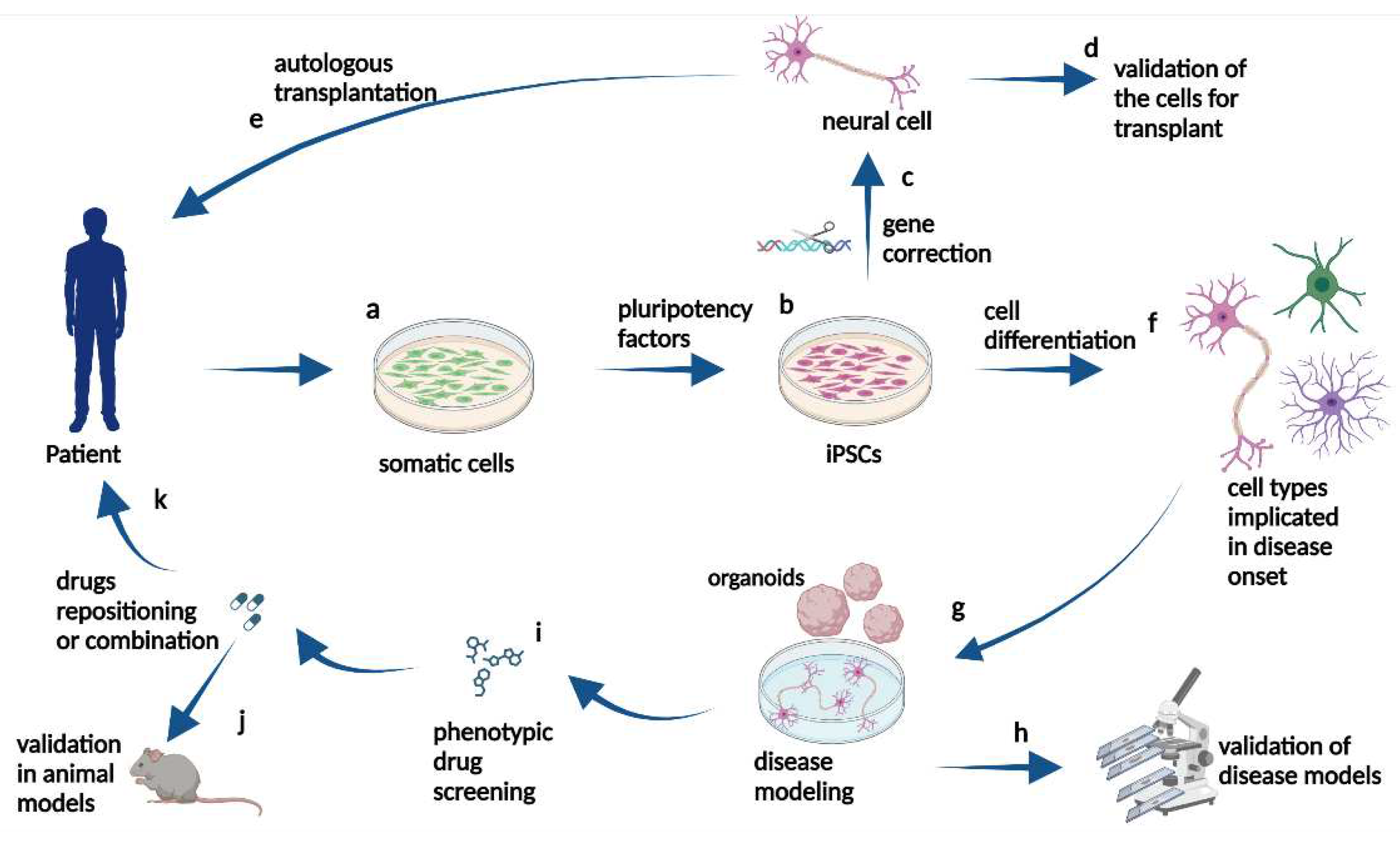

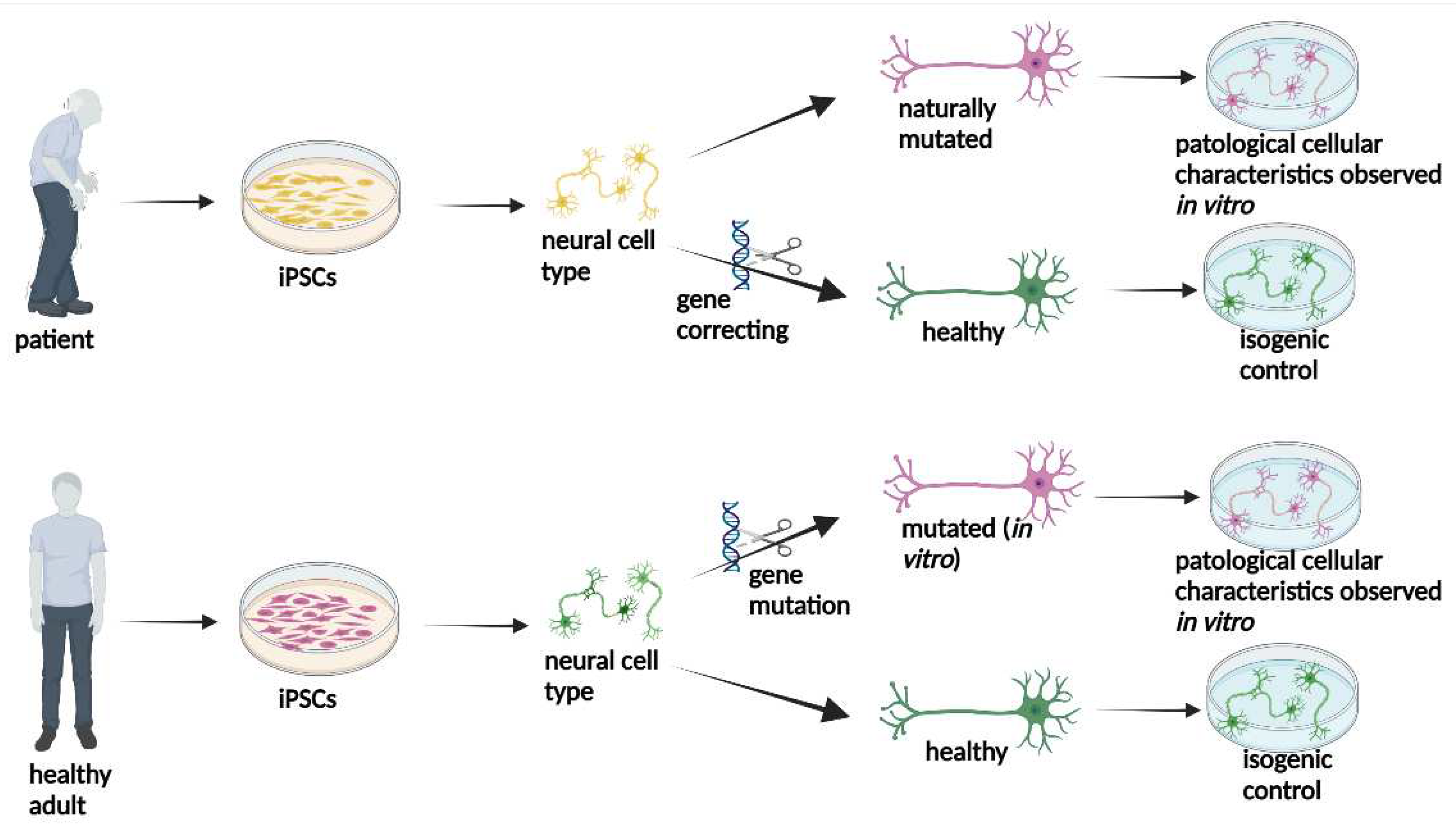

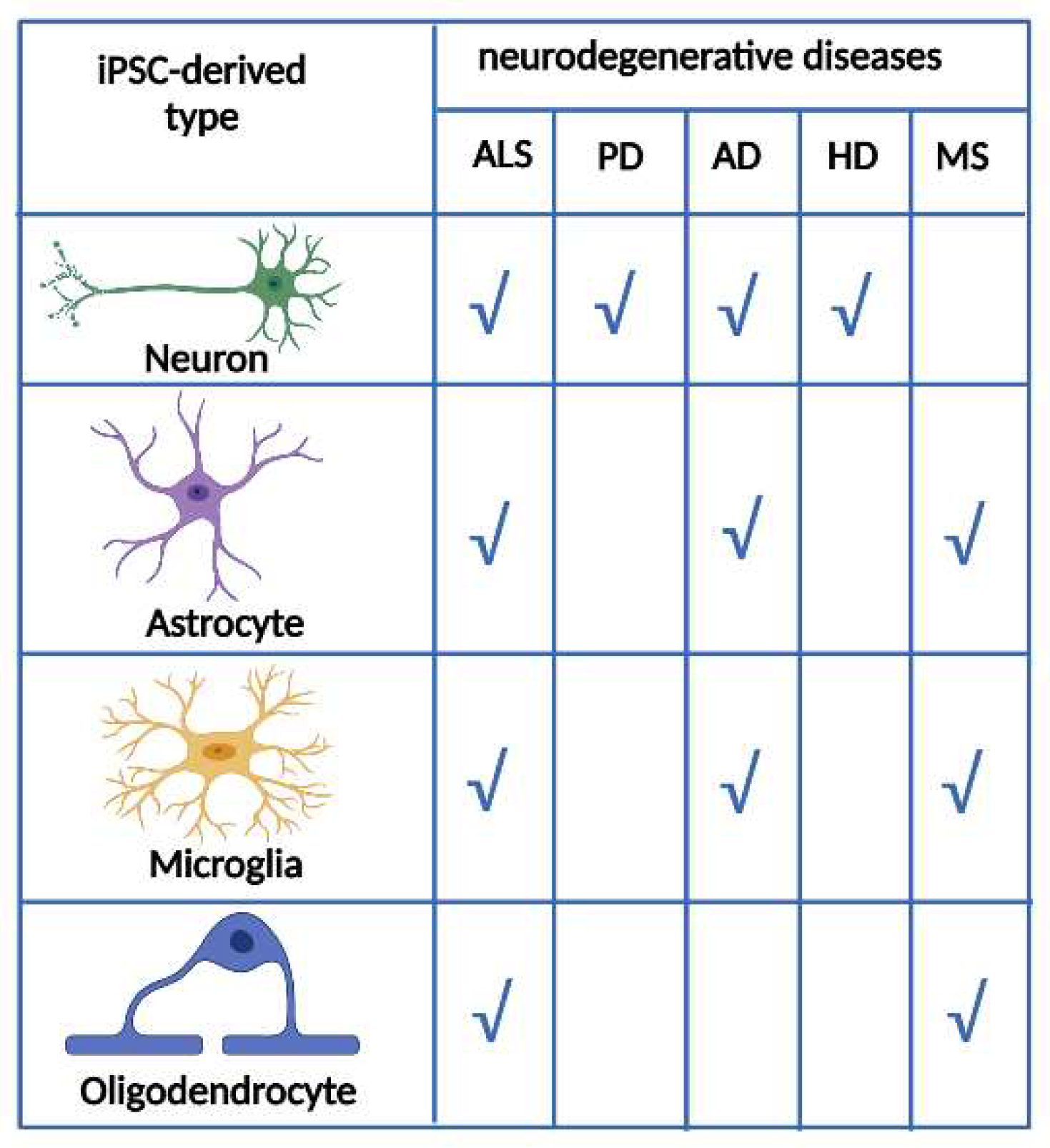

1.2. Neurodegenerative disease modeling by iPSC technology

1.3. Drug testing in neurodegenerative diseases using iPSC

1.4. Advances based on iPSCs for specific conditions

1.4.1. Parkinson disease

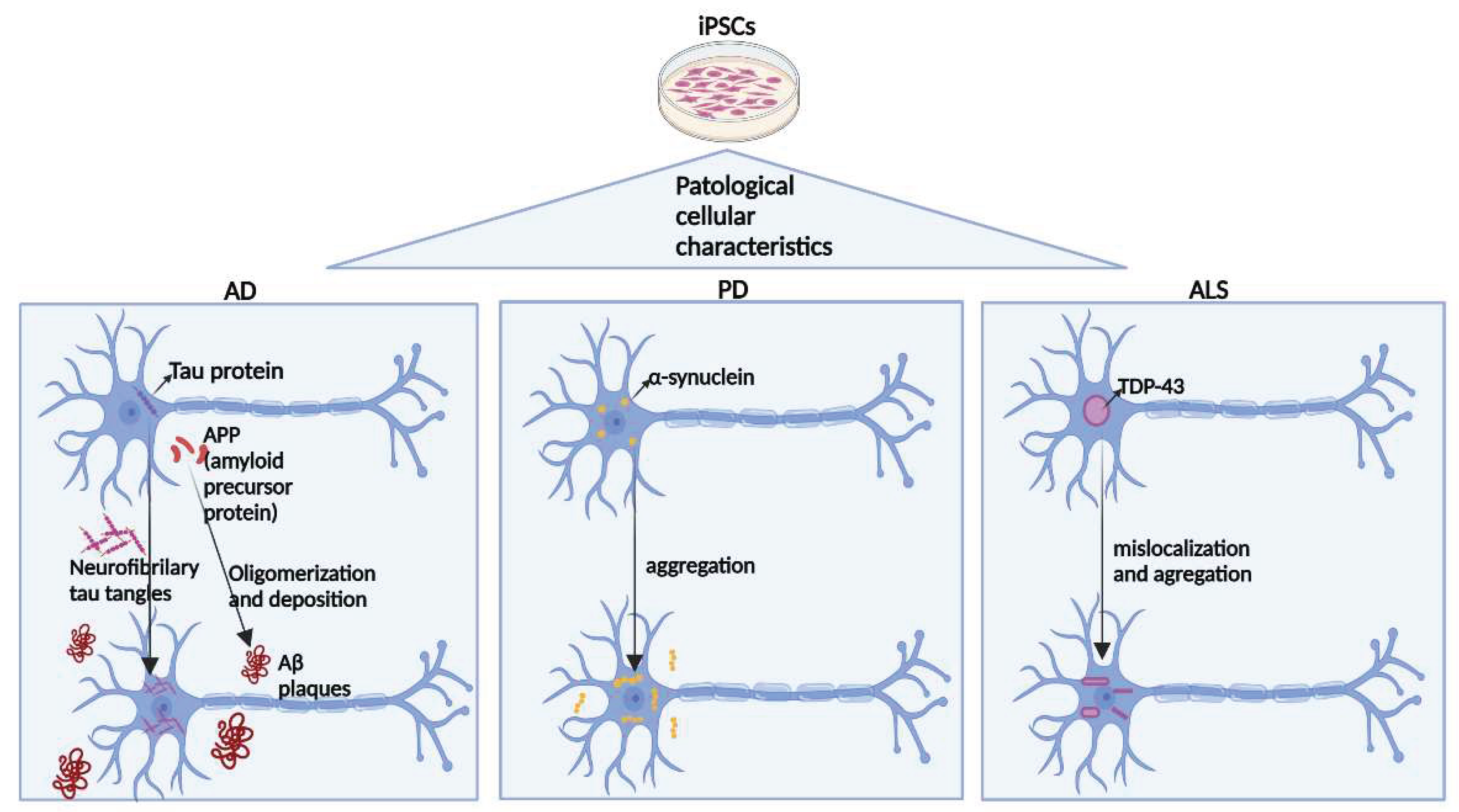

1.4.2. Alzheimer disease

1.4.3. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

1.4.4. Multiple sclerosis

1.4.5. Huntington’s disease

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorsey, E.R.; Constantinescu, R.; Thompson, J.P.; Biglan, K.M.; Holloway, R.G.; Kieburtz, K.; Marshall, F.J.; Ravina, B.M.; Schifitto, G.; Siderowf, A.; et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology 2007, 68, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, K.C.; Calvo, A.; Price, T.R.; Geiger, J.T.; Chiò, A.; Traynor, B.J. Projected increase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from 2015 to 2040. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Kim, J.; Park, H.; Choi, H. Modelling neurodegenerative diseases with 3D brain organoids. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2020, 95, 1497–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Hall, W.C.; LaMantia, A.-S.; White, L.E. Neuroscience, 5a edition ed.; 2012.

- Kamm, F.M. Ethical issues in using and not using embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rev 2005, 1, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GURDON, J.B. The developmental capacity of nuclei taken from intestinal epithelium cells of feeding tadpoles. J Embryol Exp Morphol 1962, 10, 622–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmut, I.; Schnieke, A.E.; McWhir, J.; Kind, A.J.; Campbell, K.H. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 1997, 385, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehring, W.J. Homeo boxes in the study of development. Science 1987, 236, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.L.; Weintraub, H.; Lassar, A.B. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell 1987, 51, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.J.; Kaufman, M.H. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 1981, 292, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.A.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Shapiro, S.S.; Waknitz, M.A.; Swiergiel, J.J.; Marshall, V.S.; Jones, J.M. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 1998, 282, 1145–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.G.; Heath, J.K.; Donaldson, D.D.; Wong, G.G.; Moreau, J.; Stahl, M.; Rogers, D. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature 1988, 336, 688–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusaki, N.; Ban, H.; Nishiyama, A.; Saeki, K.; Hasegawa, M. Efficient induction of transgene-free human pluripotent stem cells using a vector based on Sendai virus, an RNA virus that does not integrate into the host genome. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2009, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Guan, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, T.; Ye, J.; Yang, W.; Liu, K.; et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science 2013, 341, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, L.; Manos, P.D.; Ahfeldt, T.; Loh, Y.H.; Li, H.; Lau, F.; Ebina, W.; Mandal, P.K.; Smith, Z.D.; Meissner, A.; et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 7, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul-Soud, M.A.M.; Alzahrani, A.J.; Mahmoud, A. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)-Roles in Regenerative Therapies, Disease Modelling and Drug Screening. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwer, R.W.; Dubelaar, E.J.; Hermens, W.T.; Swaab, D.F. Tissue cultures from adult human postmortem subcortical brain areas. J Cell Mol Med 2002, 6, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijboom, K.E.; Abdallah, A.; Fordham, N.P.; Nagase, H.; Rodriguez, T.; Kraus, C.; Gendron, T.F.; Krishnan, G.; Esanov, R.; Andrade, N.S.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated excision of ALS/FTD-causing hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 rescues major disease mechanisms in vivo and in vitro. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Fleck, J.S.; Martins-Costa, C.; Burkard, T.R.; Themann, J.; Stuempflen, M.; Peer, A.M.; Vertesy, Á.; Littleboy, J.B.; Esk, C.; et al. Single-cell brain organoid screening identifies developmental defects in autism. Nature 2023, 621, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T. Modeling schizophrenia with iPS cell technology and disease mouse models. Neurosci Res 2022, 175, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sances, S.; Workman, M.J.; Svendsen, C.N. Multi-lineage Human iPSC-Derived Platforms for Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. Modeling Neurological Diseases With Human Brain Organoids. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2018, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Nguyen, H.N.; Song, M.M.; Hadiono, C.; Ogden, S.C.; Hammack, C.; Yao, B.; Hamersky, G.R.; Jacob, F.; Zhong, C.; et al. Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell 2016, 165, 1238–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muguruma, K.; Nishiyama, A.; Kawakami, H.; Hashimoto, K.; Sasai, Y. Self-organization of polarized cerebellar tissue in 3D culture of human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep 2015, 10, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantazis, C.B.; Yang, A.; Lara, E.; McDonough, J.A.; Blauwendraat, C.; Peng, L.; Oguro, H.; Kanaujiya, J.; Zou, J.; Sebesta, D.; et al. A reference human induced pluripotent stem cell line for large-scale collaborative studies. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 1685–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tropepe, V.; Hitoshi, S.; Sirard, C.; Mak, T.W.; Rossant, J.; van der Kooy, D. Direct neural fate specification from embryonic stem cells: a primitive mammalian neural stem cell stage acquired through a default mechanism. Neuron 2001, 30, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Kirwan, P.; Smith, J.; Robinson, H.P.; Livesey, F.J. Human cerebral cortex development from pluripotent stem cells to functional excitatory synapses. Nat Neurosci 2012, 15, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunhanlar, N.; Shpak, G.; van der Kroeg, M.; Gouty-Colomer, L.A.; Munshi, S.T.; Lendemeijer, B.; Ghazvini, M.; Dupont, C.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Gribnau, J.; et al. A simplified protocol for differentiation of electrophysiologically mature neuronal networks from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardy, C.; van den Hurk, M.; Eames, T.; Marchand, C.; Hernandez, R.V.; Kellogg, M.; Gorris, M.; Galet, B.; Palomares, V.; Brown, J.; et al. Neuronal medium that supports basic synaptic functions and activity of human neurons in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, E2725–E2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimos, J.T.; Rodolfa, K.T.; Niakan, K.K.; Weisenthal, L.M.; Mitsumoto, H.; Chung, W.; Croft, G.F.; Saphier, G.; Leibel, R.; Goland, R.; et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science 2008, 321, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskinis, E.; Sandoe, J.; Williams, L.A.; Boulting, G.L.; Moccia, R.; Wainger, B.J.; Han, S.; Peng, T.; Thams, S.; Mikkilineni, S.; et al. Pathways disrupted in human ALS motor neurons identified through genetic correction of mutant SOD1. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Byers, B.; Cord, B.; Shcheglovitov, A.; Byrne, J.; Gujar, P.; Kee, K.; Schüle, B.; Dolmetsch, R.E.; Langston, W.; et al. LRRK2 mutant iPSC-derived DA neurons demonstrate increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 8, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.; Morizane, A.; Doi, D.; Magotani, H.; Onoe, H.; Hayashi, T.; Mizuma, H.; Takara, S.; Takahashi, R.; Inoue, H.; et al. Human iPS cell-derived dopaminergic neurons function in a primate Parkinson's disease model. Nature 2017, 548, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, S.C. Neural Subtype Specification from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcw, J.; Wang, M.; Pimenova, A.A.; Bowles, K.R.; Hartley, B.J.; Lacin, E.; Machlovi, S.I.; Abdelaal, R.; Karch, C.M.; Phatnani, H.; et al. An Efficient Platform for Astrocyte Differentiation from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 9, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, V.; Atkinson-Dell, R.; Verkhratsks, A. Aberrant iPSC-derived human astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease. Nature: cell death & disease, 2017; p e2696.

- Garcia-Leon, J.A.; Vitorica, J.; Gutierrez, A. Use of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cells for neurodegenerative disease modeling and drug screening platform. Future Med Chem 2019, 11, 1305–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, V.C.; Atkinson-Dell, R.; Verkhratsky, A.; Mohamet, L. Aberrant iPSC-derived human astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-León, J.A.; Verfaillie, C.M. Stem Cell-Derived Oligodendroglial Cells for Therapy in Neurological Diseases. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2016, 11, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Tokumoto, Y.; Miyake, J.; Nagamune, T. Induction of oligodendrocyte differentiation from adult human fibroblast-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2011, 47, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouya, A.; Satarian, L.; Kiani, S.; Javan, M.; Baharvand, H. Human induced pluripotent stem cells differentiation into oligodendrocyte progenitors and transplantation in a rat model of optic chiasm demyelination. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bates, J.; Li, X.; Schanz, S.; Chandler-Militello, D.; Levine, C.; Maherali, N.; Studer, L.; Hochedlinger, K.; Windrem, M.; et al. Human iPSC-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can myelinate and rescue a mouse model of congenital hypomyelination. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douvaras, P.; Wang, J.; Zimmer, M.; Hanchuk, S.; O'Bara, M.A.; Sadiq, S.; Sim, F.J.; Goldman, J.; Fossati, V. Efficient generation of myelinating oligodendrocytes from primary progressive multiple sclerosis patients by induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 2014, 3, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, J.; Major, T.; Auyeung, G.; Policarpio, E.; Menon, J.; Droms, L.; Gutin, P.; Uryu, K.; Tchieu, J.; Soulet, D.; et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived oligodendrocyte progenitors remyelinate the brain and rescue behavioral deficits following radiation. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, H.; Shen, M.J.; Ichikawa, D.M.; Sedlock, A.B.; Choi, Y.; Johnson, K.R.; Kim, G.; Brown, M.A.; Elkahloun, A.G.; Maric, D.; et al. Differentiation of human and murine induced pluripotent stem cells to microglia-like cells. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abud, E.M.; Ramirez, R.N.; Martinez, E.S.; Healy, L.M.; Nguyen, C.H.H.; Newman, S.A.; Yeromin, A.V.; Scarfone, V.M.; Marsh, S.E.; Fimbres, C.; et al. iPSC-Derived Human Microglia-like Cells to Study Neurological Diseases. Neuron 2017, 94, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.V.; Hanson, J.E.; Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Renner, M.; Martin, C.A.; Wenzel, D.; Bicknell, L.S.; Hurles, M.E.; Homfray, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Jackson, A.P.; Knoblich, J.A. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 2013, 501, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.T.; Bendriem, R.M.; Wu, W.W.; Shen, R.F. 3D brain Organoids derived from pluripotent stem cells: promising experimental models for brain development and neurodegenerative disorders. J Biomed Sci 2017, 24, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaskovic-Crook, E.; Crook, J.M. Clinically Amendable, Defined, and Rapid Induction of Human Brain Organoids from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1576, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.K.; Wong, S.Z.H.; Pather, S.R.; Nguyen, P.T.T.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, L.; Fang, W.; Chen, L.; et al. Generation of hypothalamic arcuate organoids from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Ramirez, C.N.; Kim, H.; Zeltner, N.; Liu, B.; Radu, C.; Bhinder, B.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, I.Y.; Mukherjee-Clavin, B.; et al. Large-scale screening using familial dysautonomia induced pluripotent stem cells identifies compounds that rescue IKBKAP expression. Nat Biotechnol 2012, 30, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhardt, M.F.; Martinez, F.J.; Wright, S.; Ramos, C.; Volfson, D.; Mason, M.; Garnes, J.; Dang, V.; Lievers, J.; Shoukat-Mumtaz, U.; et al. A cellular model for sporadic ALS using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Cell Neurosci 2013, 56, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naryshkin, N.A.; Weetall, M.; Dakka, A.; Narasimhan, J.; Zhao, X.; Feng, Z.; Ling, K.K.; Karp, G.M.; Qi, H.; Woll, M.G.; et al. Motor neuron disease. SMN2 splicing modifiers improve motor function and longevity in mice with spinal muscular atrophy. Science 2014, 345, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainger, B.J.; Kiskinis, E.; Mellin, C.; Wiskow, O.; Han, S.S.; Sandoe, J.; Perez, N.P.; Williams, L.A.; Lee, S.; Boulting, G.; et al. Intrinsic membrane hyperexcitability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient-derived motor neurons. Cell Rep 2014, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeish, J.; Gardner, J.P.; Wainger, B.J.; Woolf, C.J.; Eggan, K. From Dish to Bedside: Lessons Learned While Translating Findings from a Stem Cell Model of Disease to a Clinical Trial. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, K.D. The impact of levodopa on quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurologist 2010, 16, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundin, P.; Strecker, R.; Clarke, D.; Widner, H.; Nilsson, O.; Åstedt, B.; Lindvall, O.; Björklund, A. Chapter 57 Can human fetal dopamine neuron grafts provide a therapy for Parkinson's disease? In Progress in Brain Research, Elsevier, Ed. 1988; Vol. 78, pp. 441–448.

- Barker, R.A.; Parmar, M.; Kirkeby, A.; Björklund, A.; Thompson, L.; Brundin, P. Are Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Parkinson's Disease Ready for the Clinic in 2016? J Parkinsons Dis 2016, 6, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuhara, T.; Kameda, M.; Sasaki, T.; Tajiri, N.; Date, I. Cell Therapy for Parkinson's Disease. Cell Transplant 2017, 26, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, M.J.; Ryten, M.; Vodicka, P.; Thomson, A.J.; Burdon, T.; Houlden, H.; Cavaleri, F.; Nagano, M.; Drummond, N.J.; Taanman, J.W.; et al. Parkinson's disease induced pluripotent stem cells with triplication of the α-synuclein locus. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, C.M.; Campos, B.A.; Kuo, S.H.; Nirenberg, M.J.; Nestor, M.W.; Zimmer, M.; Mosharov, E.V.; Sulzer, D.; Zhou, H.; Paull, D.; et al. iPSC-derived dopamine neurons reveal differences between monozygotic twins discordant for Parkinson's disease. Cell Rep 2014, 9, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, J.S.; Song, B.; Herrington, T.M.; Park, T.Y.; Lee, N.; Ko, S.; Jeon, J.; Cha, Y.; Kim, K.; Li, Q.; et al. Personalized iPSC-Derived Dopamine Progenitor Cells for Parkinson's Disease. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1926–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard-Bennett, T.; Reijo Pera, R. Treatment of Parkinson's Disease through Personalized Medicine and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanco, J.C.; Li, C.; Bodea, L.G.; Martinez-Marmol, R.; Meunier, F.A.; Götz, J. Amyloid-β and tau complexity - towards improved biomarkers and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, A.; Vitorica, J. Toward a New Concept of Alzheimer's Disease Models: A Perspective from Neuroinflammation. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 64, S329–S338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagi, T.; Ito, D.; Okada, Y.; Akamatsu, W.; Nihei, Y.; Yoshizaki, T.; Yamanaka, S.; Okano, H.; Suzuki, N. Modeling familial Alzheimer's disease with induced pluripotent stem cells. Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20, 4530–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muratore, C.R.; Rice, H.C.; Srikanth, P.; Callahan, D.G.; Shin, T.; Benjamin, L.N.; Walsh, D.M.; Selkoe, D.J.; Young-Pearse, T.L. The familial Alzheimer's disease APPV717I mutation alters APP processing and Tau expression in iPSC-derived neurons. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, 3523–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, T.; Imamura, K.; Funayama, M.; Tsukita, K.; Miyake, M.; Ohta, A.; Woltjen, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Asada, T.; Arai, T.; et al. iPSC-Based Compound Screening and In Vitro Trials Identify a Synergistic Anti-amyloid β Combination for Alzheimer's Disease. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Lei, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.J.; Sun, M.; Nuwaysir, E.; Fan, G.; Zhao, J.; et al. Prevention of β-amyloid induced toxicity in human iPS cell-derived neurons by inhibition of Cyclin-dependent kinases and associated cell cycle events. Stem Cell Res 2013, 10, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, M.A.; Yuan, S.H.; Bardy, C.; Reyna, S.M.; Mu, Y.; Herrera, C.; Hefferan, M.P.; Van Gorp, S.; Nazor, K.L.; Boscolo, F.S.; et al. Probing sporadic and familial Alzheimer's disease using induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2012, 482, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovino, M.; Agathou, S.; González-Rueda, A.; Del Castillo Velasco-Herrera, M.; Borroni, B.; Alberici, A.; Lynch, T.; O'Dowd, S.; Geti, I.; Gaffney, D.; et al. Early maturation and distinct tau pathology in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons from patients with MAPT mutations. Brain 2015, 138, 3345–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeshchik, Y.; Klementieva, O.; Gil, J.; Martinsson, I.; Hansen, M.G.; de Vries, T.; Sancho-Balsells, A.; Russ, K.; Savchenko, E.; Collin, A.; et al. Human iPSC-Derived Hippocampal Spheroids: An Innovative Tool for Stratifying Alzheimer Disease Patient-Specific Cellular Phenotypes and Developing Therapies. Stem Cell Reports 2020, 15, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olabarria, M.; Noristani, H.N.; Verkhratsky, A.; Rodríguez, J.J. Concomitant astroglial atrophy and astrogliosis in a triple transgenic animal model of Alzheimer's disease. Glia 2010, 58, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, M.; Petersen, A.J.; Naumenko, N.; Puttonen, K.; Lehtonen, Š.; Gubert Olivé, M.; Shakirzyanova, A.; Leskelä, S.; Sarajärvi, T.; Viitanen, M.; et al. PSEN1 Mutant iPSC-Derived Model Reveals Severe Astrocyte Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 9, 1885–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konttinen, H.; Cabral-da-Silva, M.E.C.; Ohtonen, S.; Wojciechowski, S.; Shakirzyanova, A.; Caligola, S.; Giugno, R.; Ishchenko, Y.; Hernández, D.; Fazaludeen, M.F.; et al. PSEN1ΔE9, APPswe, and APOE4 Confer Disparate Phenotypes in Human iPSC-Derived Microglia. Stem Cell Reports 2019, 13, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Hebisch, M.; Sliwinski, C.; Lee, S.; D'Avanzo, C.; Chen, H.; Hooli, B.; Asselin, C.; Muffat, J.; et al. A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature 2014, 515, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, W.K.; Mungenast, A.E.; Lin, Y.T.; Ko, T.; Abdurrob, F.; Seo, J.; Tsai, L.H. Self-Organizing 3D Human Neural Tissue Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Recapitulate Alzheimer's Disease Phenotypes. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0161969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.P.; Brown, R.H.; Cleveland, D.W. Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature 2016, 539, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egawa, N.; Kitaoka, S.; Tsukita, K.; Naitoh, M.; Takahashi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Adachi, F.; Kondo, T.; Okita, K.; Asaka, I.; et al. Drug screening for ALS using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 145ra104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, D.; O'Rourke, J.G.; Meera, P.; Muhammad, A.K.; Grant, S.; Simpkinson, M.; Bell, S.; Carmona, S.; Ornelas, L.; Sahabian, A.; et al. Targeting RNA foci in iPSC-derived motor neurons from ALS patients with a C9ORF72 repeat expansion. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5, 208ra149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskinis, E.; Kralj, J.M.; Zou, P.; Weinstein, E.N.; Zhang, H.; Tsioras, K.; Wiskow, O.; Ortega, J.A.; Eggan, K.; Cohen, A.E. All-Optical Electrophysiology for High-Throughput Functional Characterization of a Human iPSC-Derived Motor Neuron Model of ALS. Stem Cell Reports 2018, 10, 1991–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, J.P.; De Calbiac, H.; Kabashi, E.; Barmada, S.J. Autophagy and ALS: mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications. Autophagy 2022, 18, 254–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madill, M.; McDonagh, K.; Ma, J.; Vajda, A.; McLoughlin, P.; O'Brien, T.; Hardiman, O.; Shen, S. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient iPSC-derived astrocytes impair autophagy via non-cell autonomous mechanisms. Mol Brain 2017, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraiuolo, L.; Meyer, K.; Sherwood, T.W.; Vick, J.; Likhite, S.; Frakes, A.; Miranda, C.J.; Braun, L.; Heath, P.R.; Pineda, R.; et al. Oligodendrocytes contribute to motor neuron death in ALS via SOD1-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E6496–E6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamout, B.I.; Alroughani, R. Multiple Sclerosis. Semin Neurol 2018, 38, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-León, J.A.; Kumar, M.; Boon, R.; Chau, D.; One, J.; Wolfs, E.; Eggermont, K.; Berckmans, P.; Gunhanlar, N.; de Vrij, F.; et al. SOX10 Single Transcription Factor-Based Fast and Efficient Generation of Oligodendrocytes from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2018, 10, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, F.J.; Madhavan, M.; Zaremba, A.; Shick, E.; Karl, R.T.; Factor, D.C.; Miller, T.E.; Nevin, Z.S.; Kantor, C.; Sargent, A.; et al. Drug-based modulation of endogenous stem cells promotes functional remyelination in vivo. Nature 2015, 522, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviaud, N.; Chen, E.; Edwards, T.; Sadiq, S.A. Cerebral organoids in primary progressive multiple sclerosis reveal stem cell and oligodendrocyte differentiation defect. Biol Open 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, T.B.; Mason, S.L.; Greenland, J.C.; Holden, S.T.; Santini, H.; Barker, R.A. Huntington's disease: diagnosis and management. Pract Neurol 2022, 22, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, H.i. Induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Huntington's disease show CAG-repeat-expansion-associated phenotypes. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tay, Y.; Sim, B.; Yoon, S.I.; Huang, Y.; Ooi, J.; Utami, K.H.; Ziaei, A.; Ng, B.; Radulescu, C.; et al. Reversal of Phenotypic Abnormalities by CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Correction in Huntington Disease Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 8, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccato, C.; Valenza, M.; Cattaneo, E. Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutical targets in Huntington's disease. Physiol Rev 2010, 90, 905–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekrasov, E.D.; Vigont, V.A.; Klyushnikov, S.A.; Lebedeva, O.S.; Vassina, E.M.; Bogomazova, A.N.; Chestkov, I.V.; Semashko, T.A.; Kiseleva, E.; Suldina, L.A.; et al. Manifestation of Huntington's disease pathology in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons. Mol Neurodegener 2016, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linville, R.M.; Nerenberg, R.F.; Grifno, G.; Arevalo, D.; Guo, Z.; Searson, P.C. Brain microvascular endothelial cell dysfunction in an isogenic juvenile iPSC model of Huntington's disease. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonov, S.A.; Novosadova, E.V. Current State-of-the-Art and Unresolved Problems in Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Dopamine Neurons for Parkinson's Disease Drug Development. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costamagna, G.; Comi, G.P.; Corti, S. Advancing Drug Discovery for Neurological Disorders Using iPSC-Derived Neural Organoids. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balusu, S.; Praschberger, R.; Lauwers, E.; De Strooper, B.; Verstreken, P. Neurodegeneration cell per cell. Neuron 2023, 111, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxi, E.G.; Thompson, T.; Li, J.; Kaye, J.A.; Lim, R.G.; Wu, J.; Ramamoorthy, D.; Lima, L.; Vaibhav, V.; Matlock, A.; et al. Answer ALS, a large-scale resource for sporadic and familial ALS combining clinical and multi-omics data from induced pluripotent cell lines. Nat Neurosci 2022, 25, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Ting, H.C.; Liu, C.A.; Su, H.L.; Chiou, T.W.; Lin, S.Z.; Harn, H.J.; Ho, T.J. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Based Neurodegenerative Disease Models for Phenotype Recapitulation and Drug Screening. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).