Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

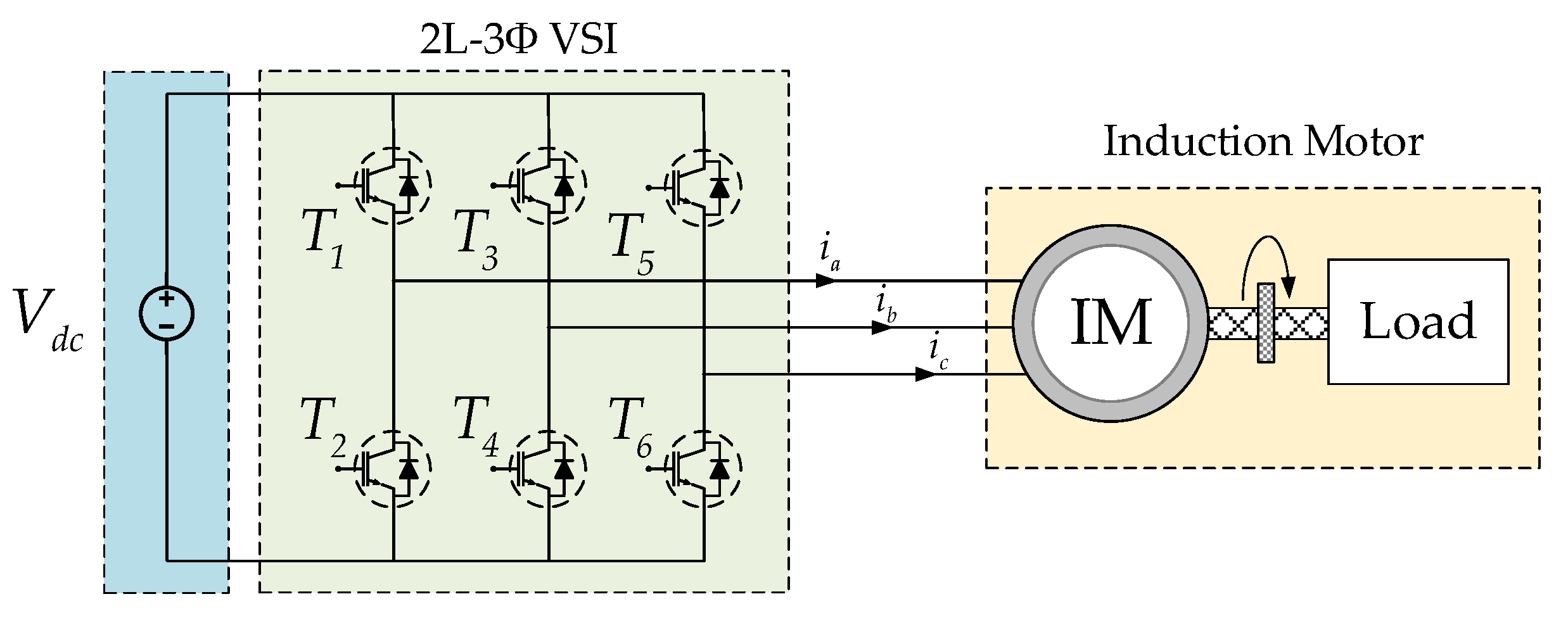

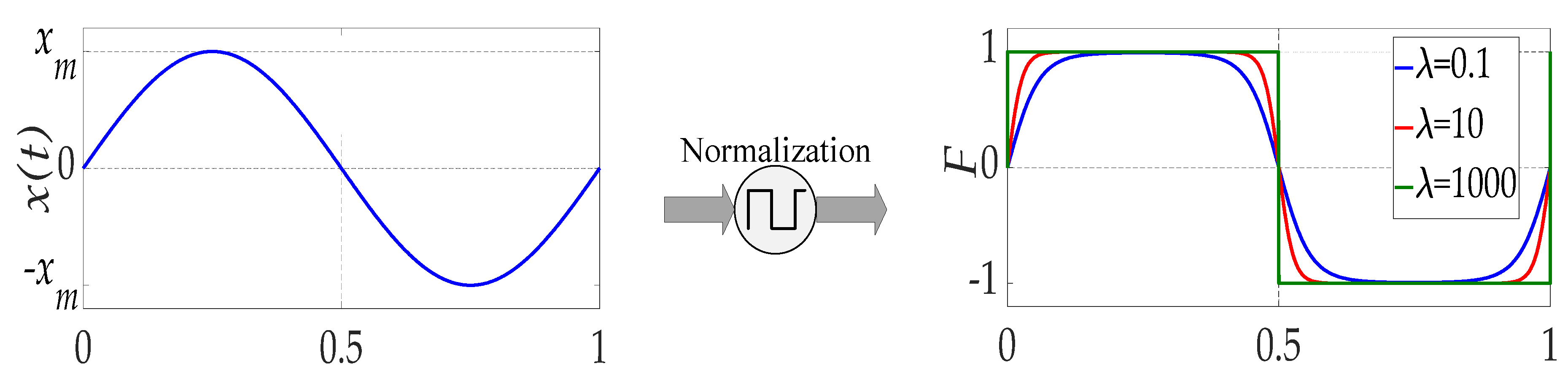

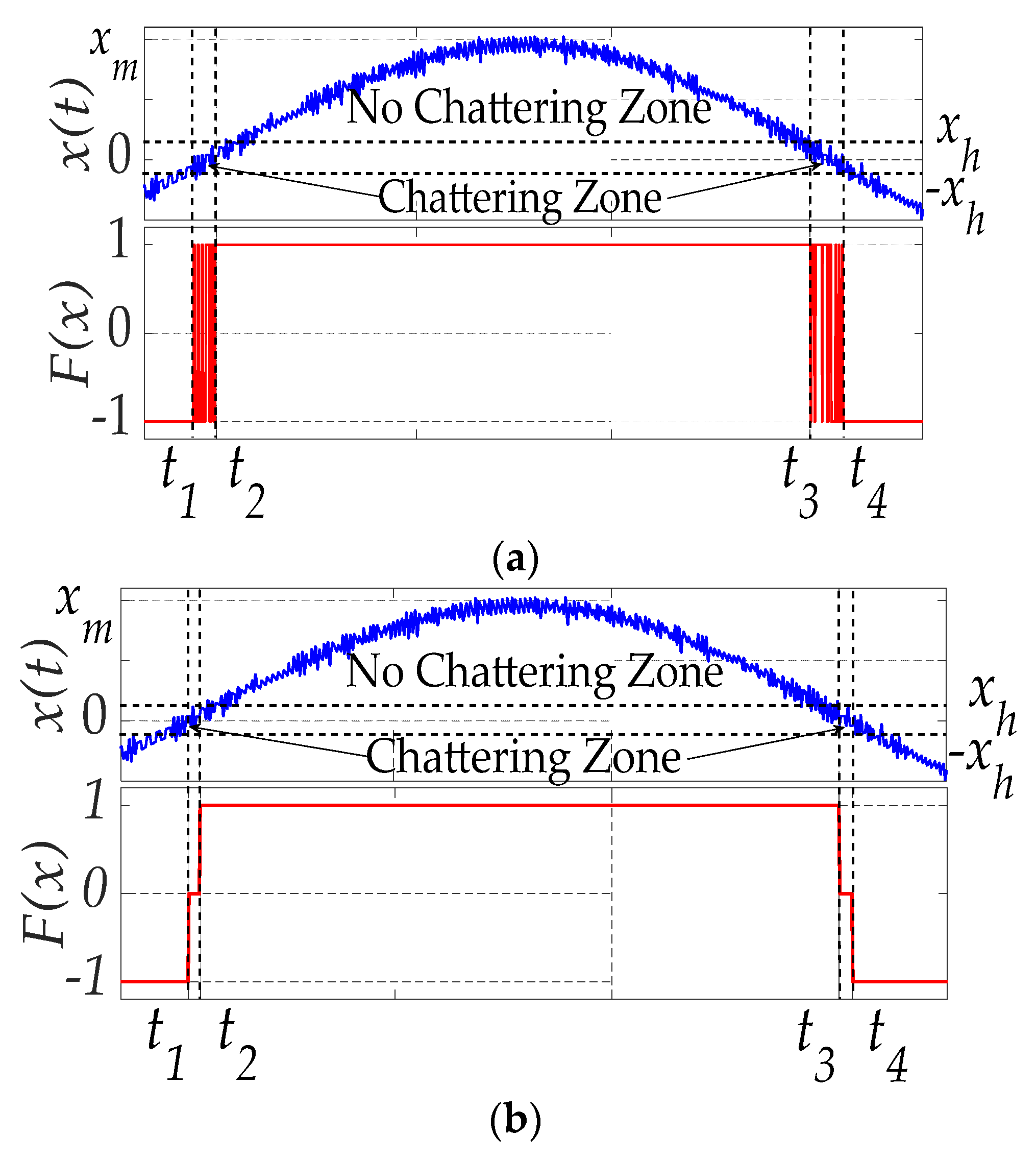

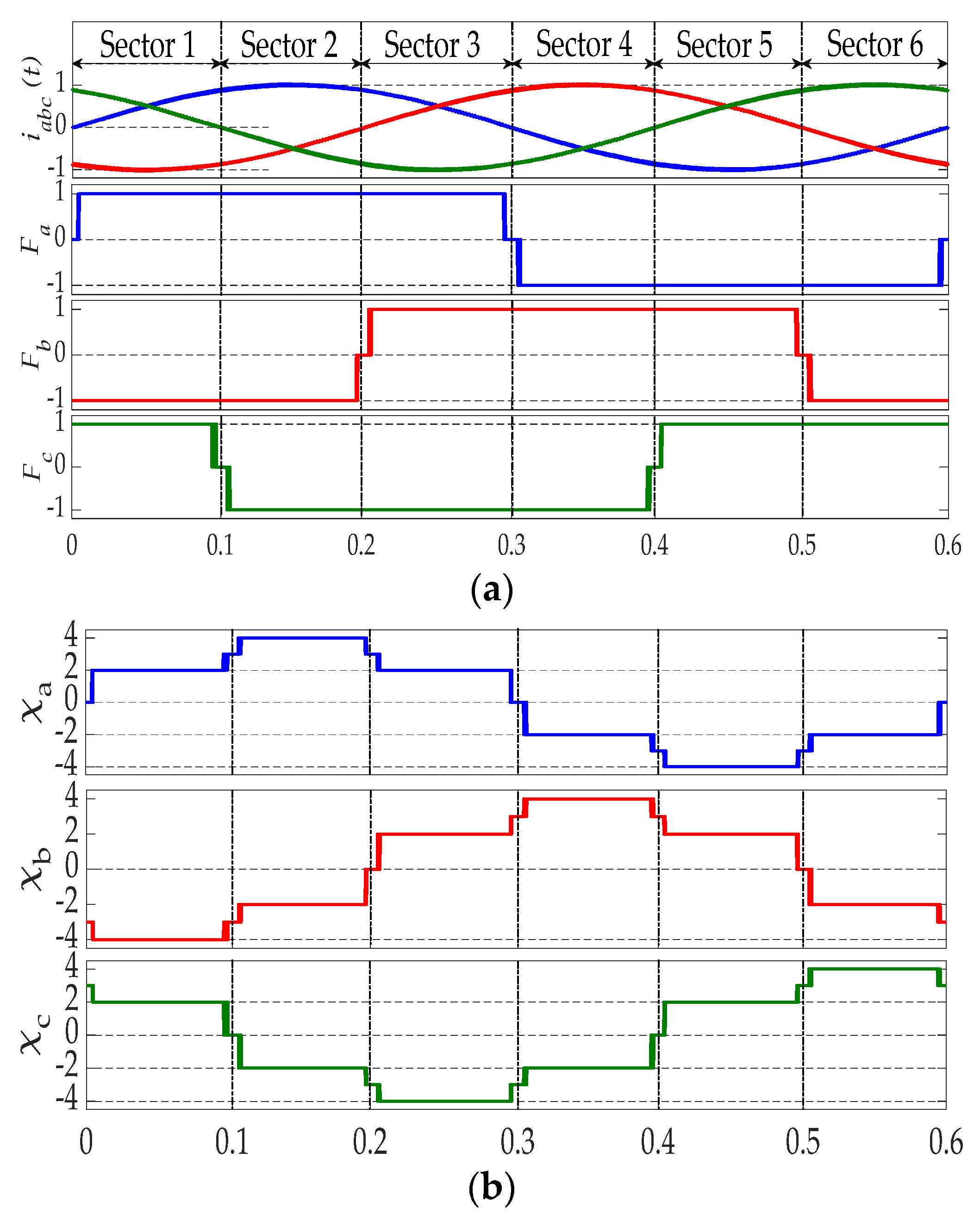

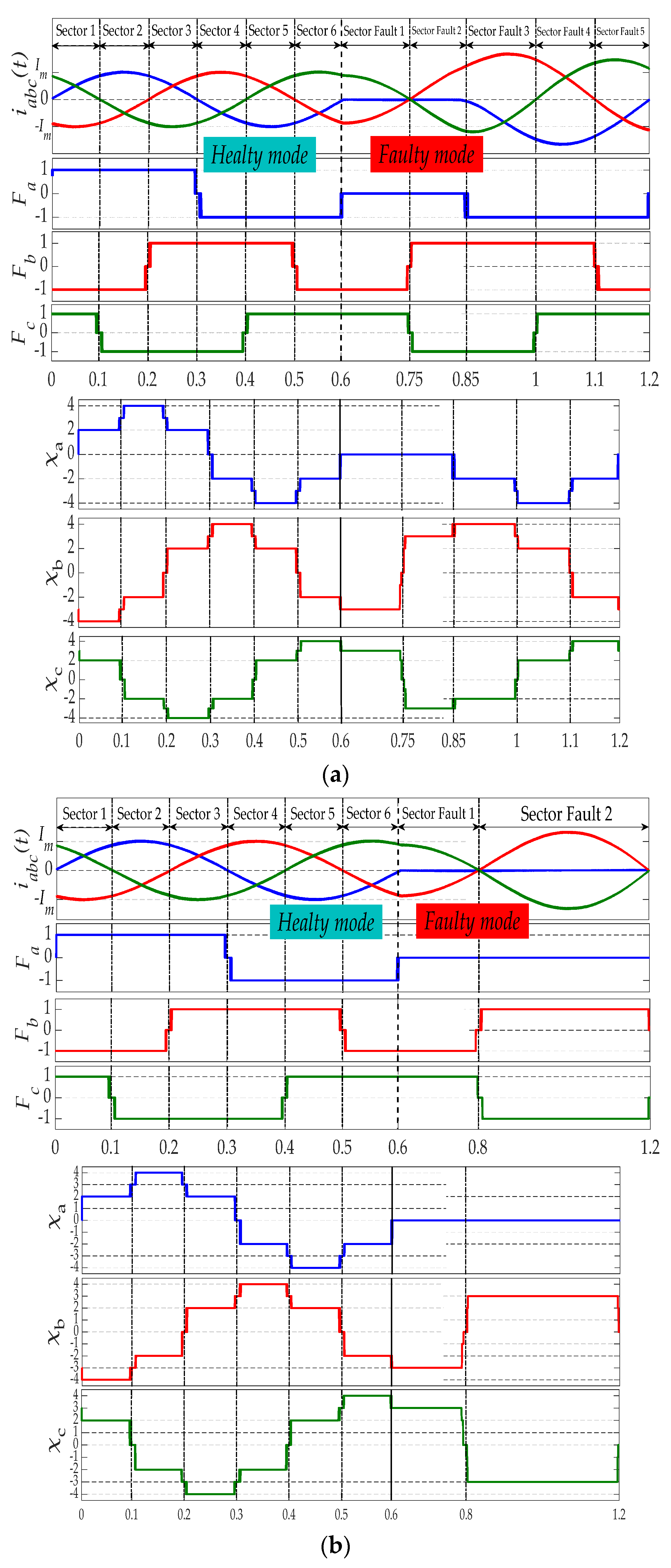

2. Fault Features Analysis

3. LSTM Approach for Fault Diagnosis

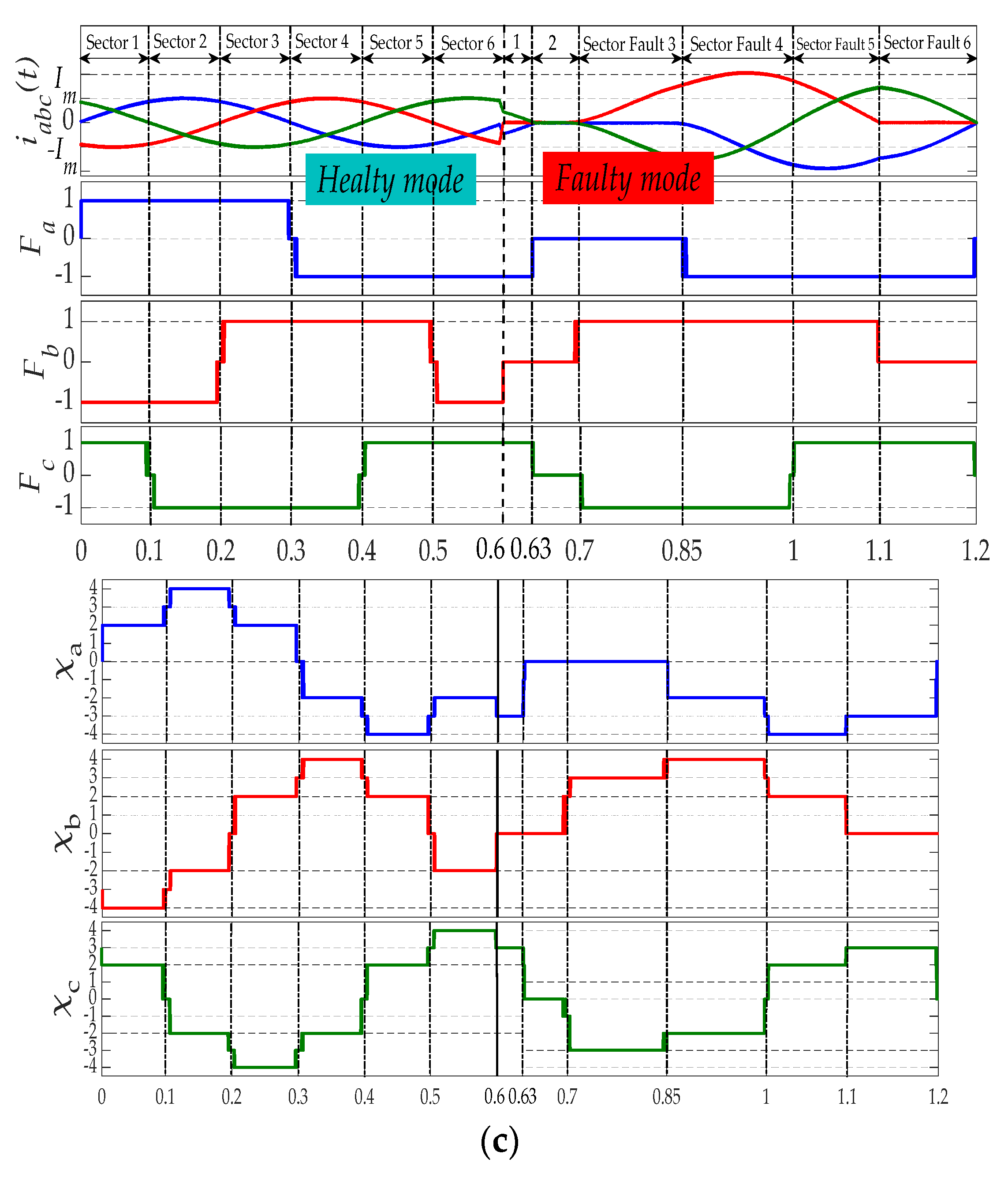

3.1. LSTM Structure

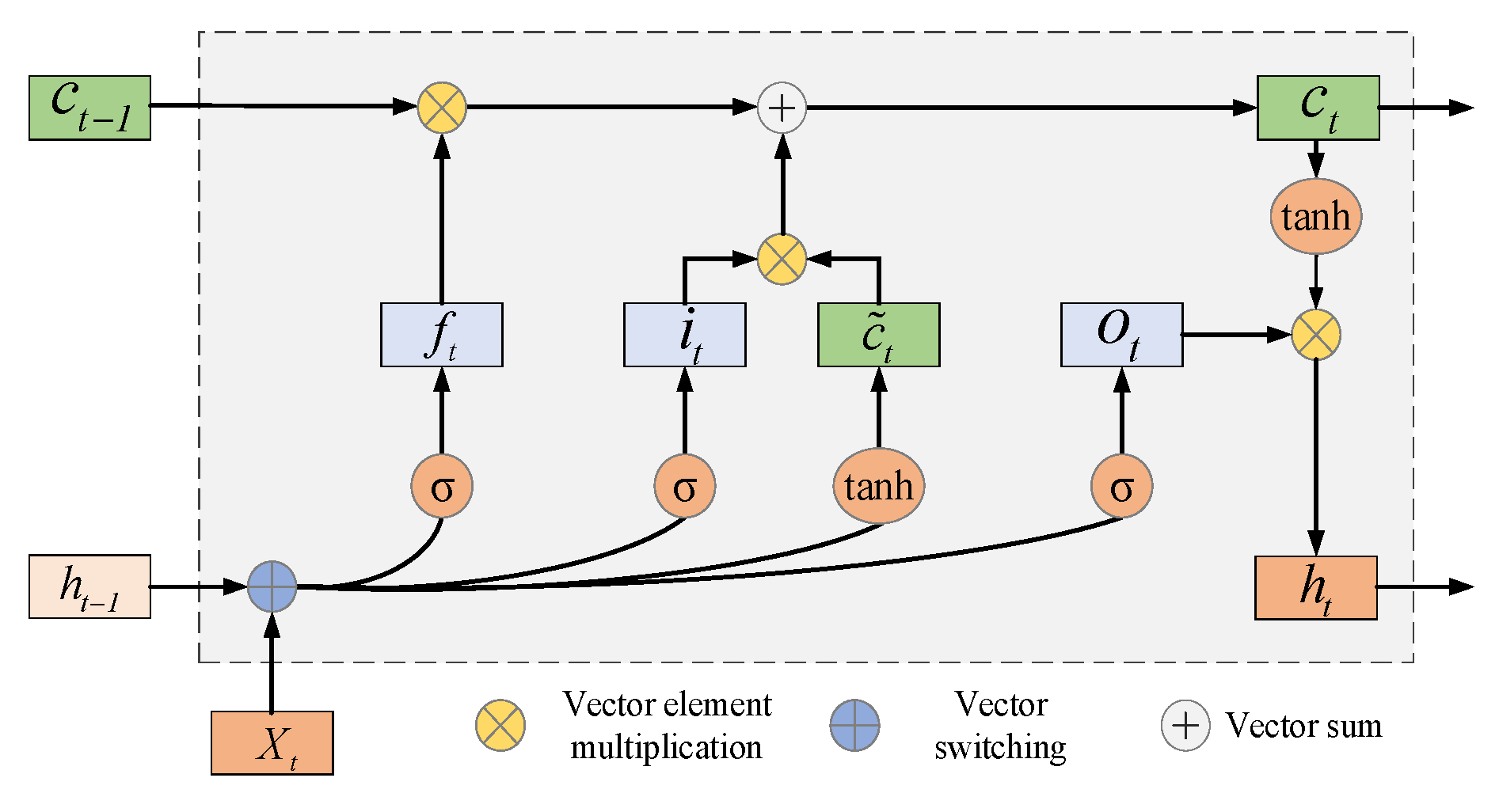

3.2. Stacked LSTM (MLSTM)

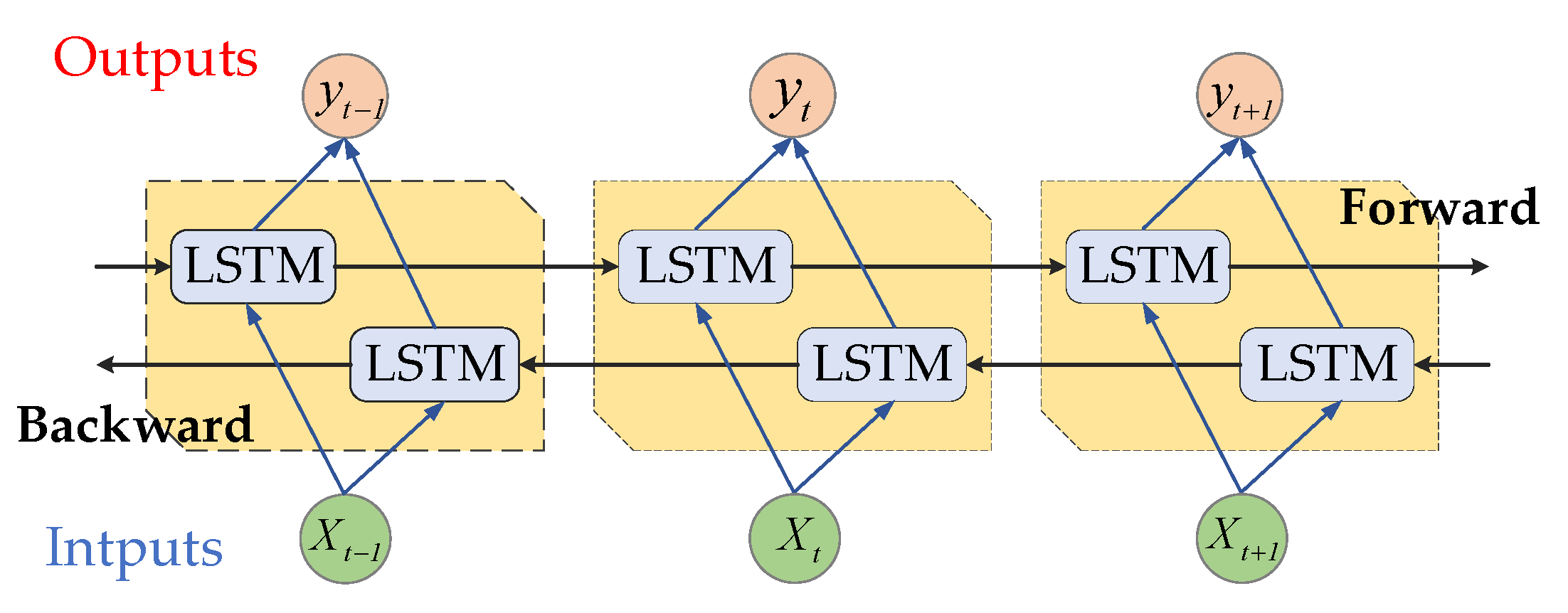

3.3. Bidirectional LSTMs (BiLSTM)

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

3.4.1. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

3.4.2. Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

3.4.3. Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MPAE)

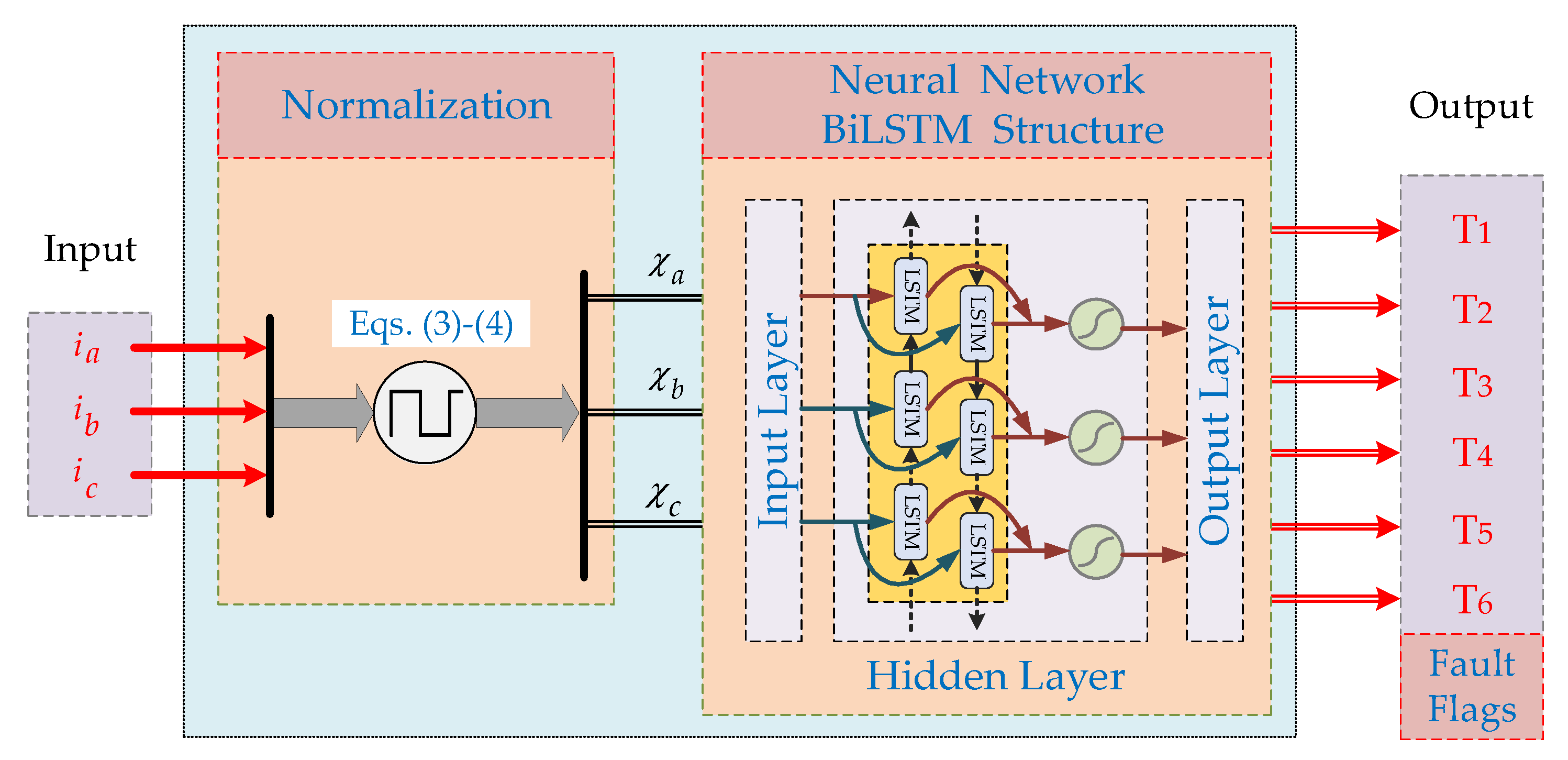

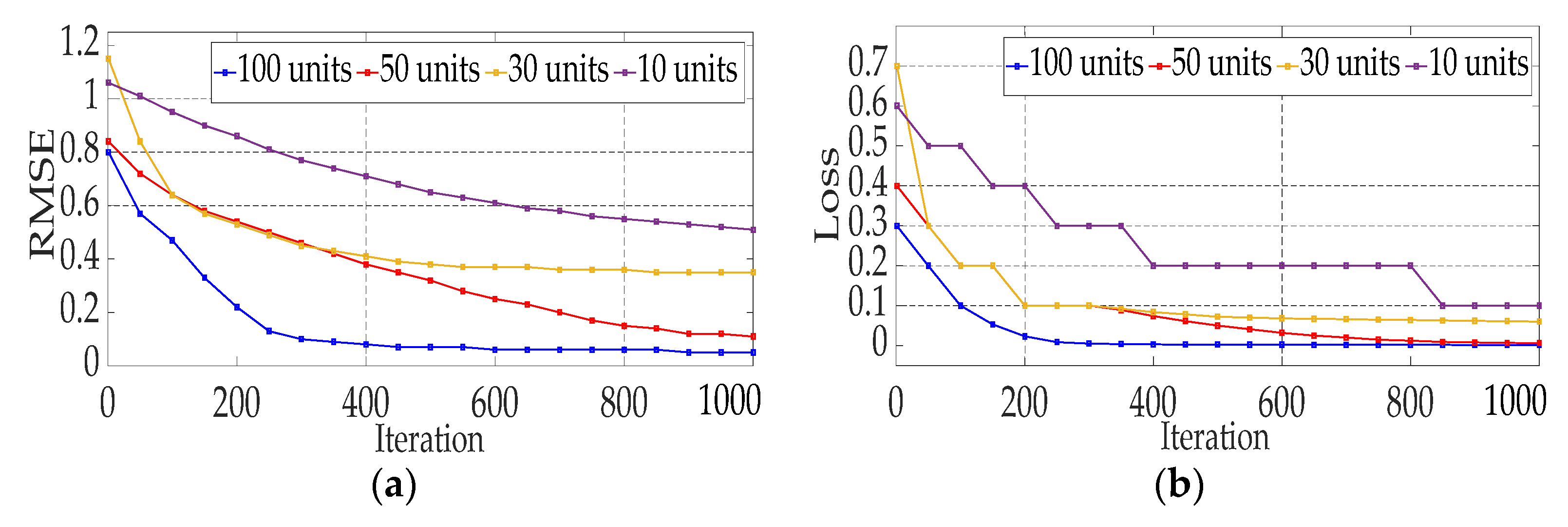

3.5. Diagnostic Network Implementation and Validation

| Algorithm 1: BiLSTM-based Fault Diagnosis Algorithm |

Step 1: Data set collection.

Step 3: Set BiLSTM model.

Step 5: Return the network model . Step 6: Test model. If the evaluation metrics are not satisfactory, then adjust network parameters and go to Step 3. |

4. Simulation Results

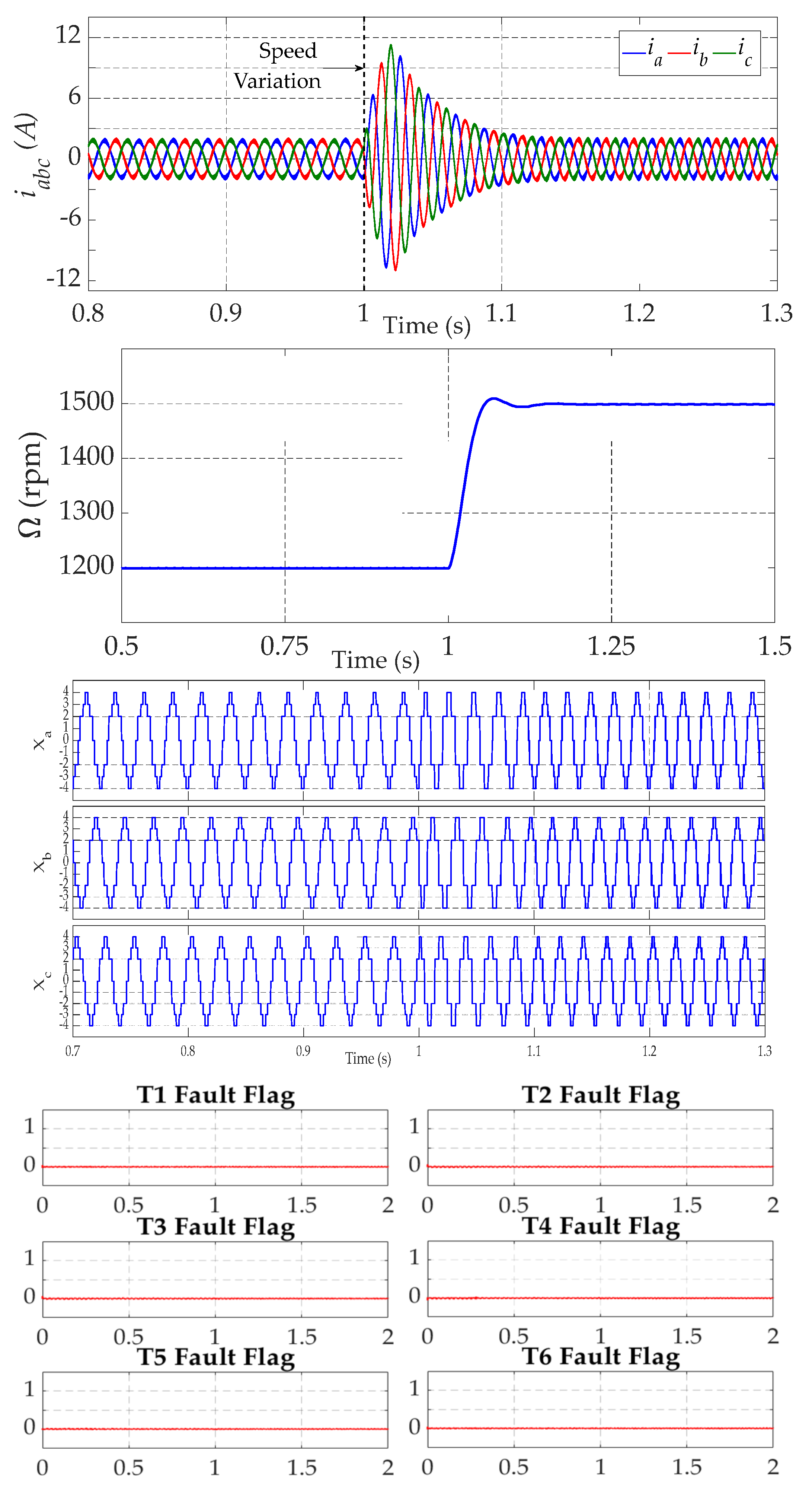

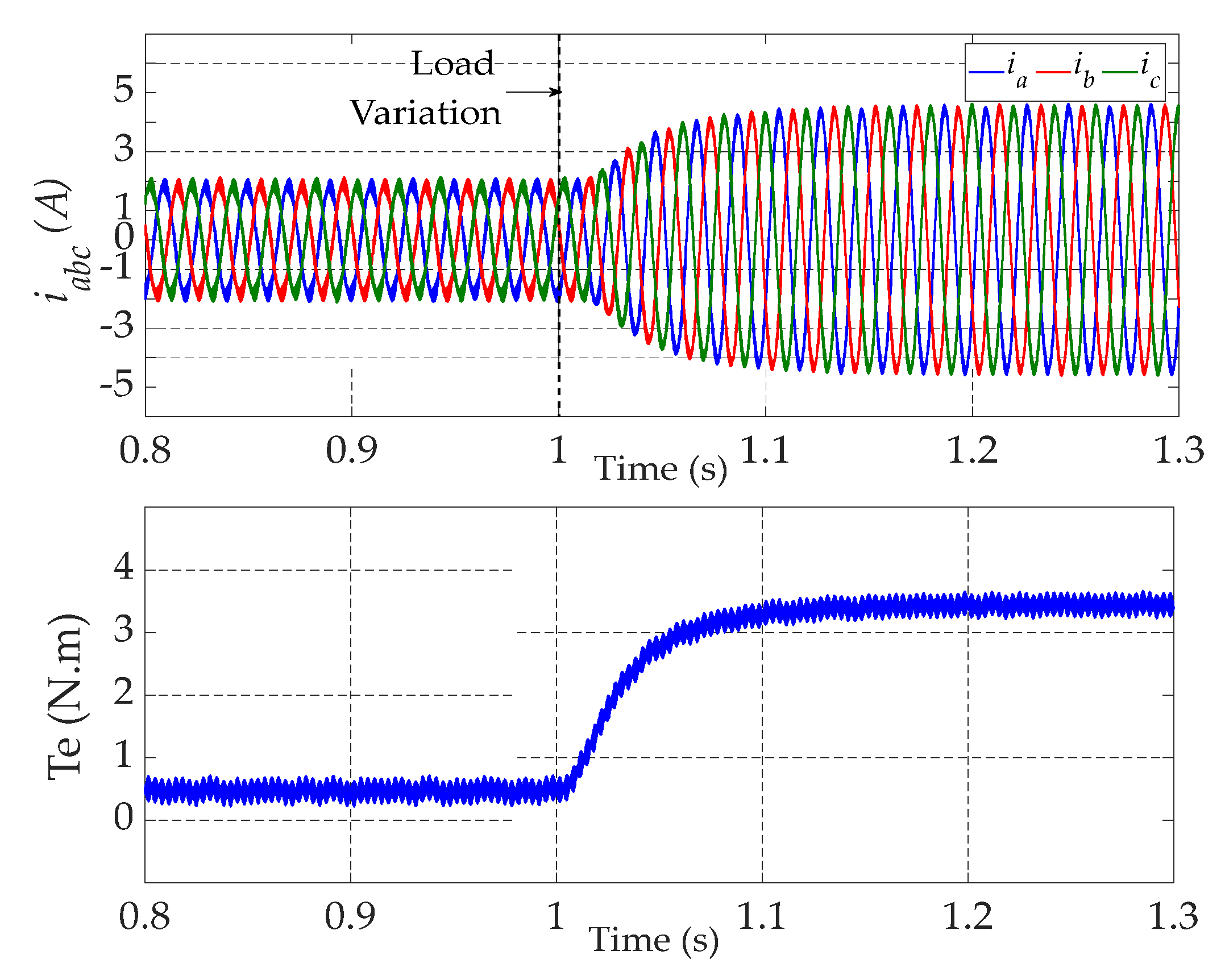

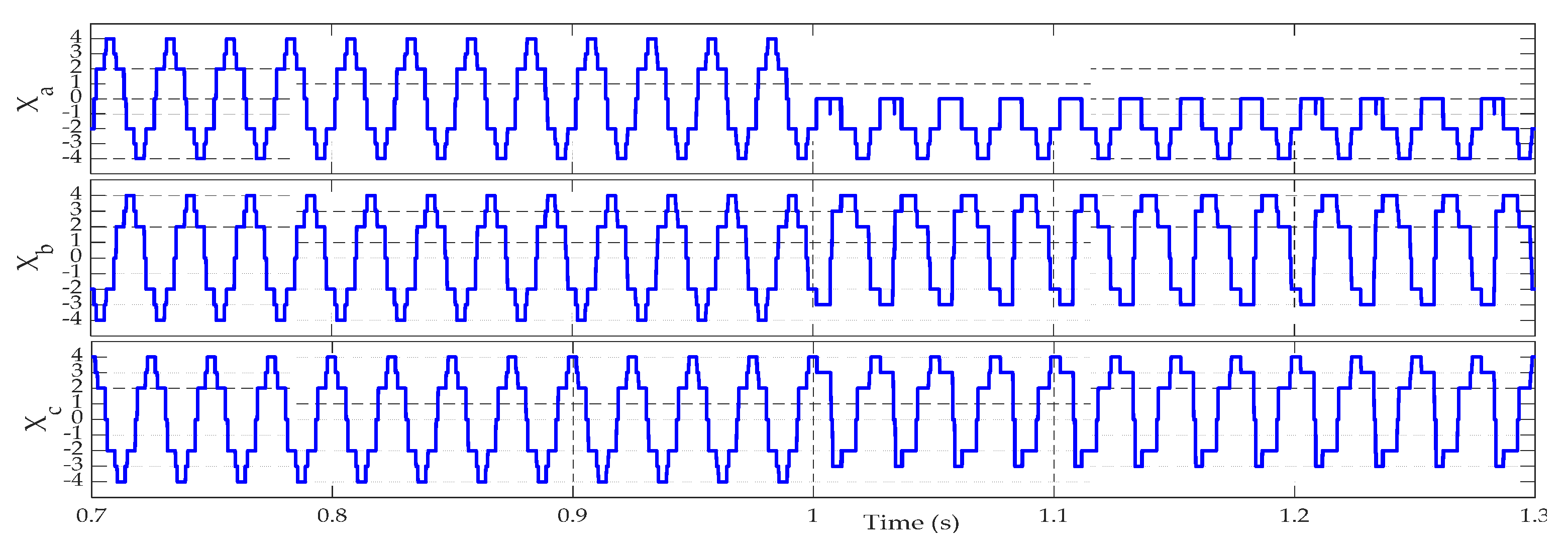

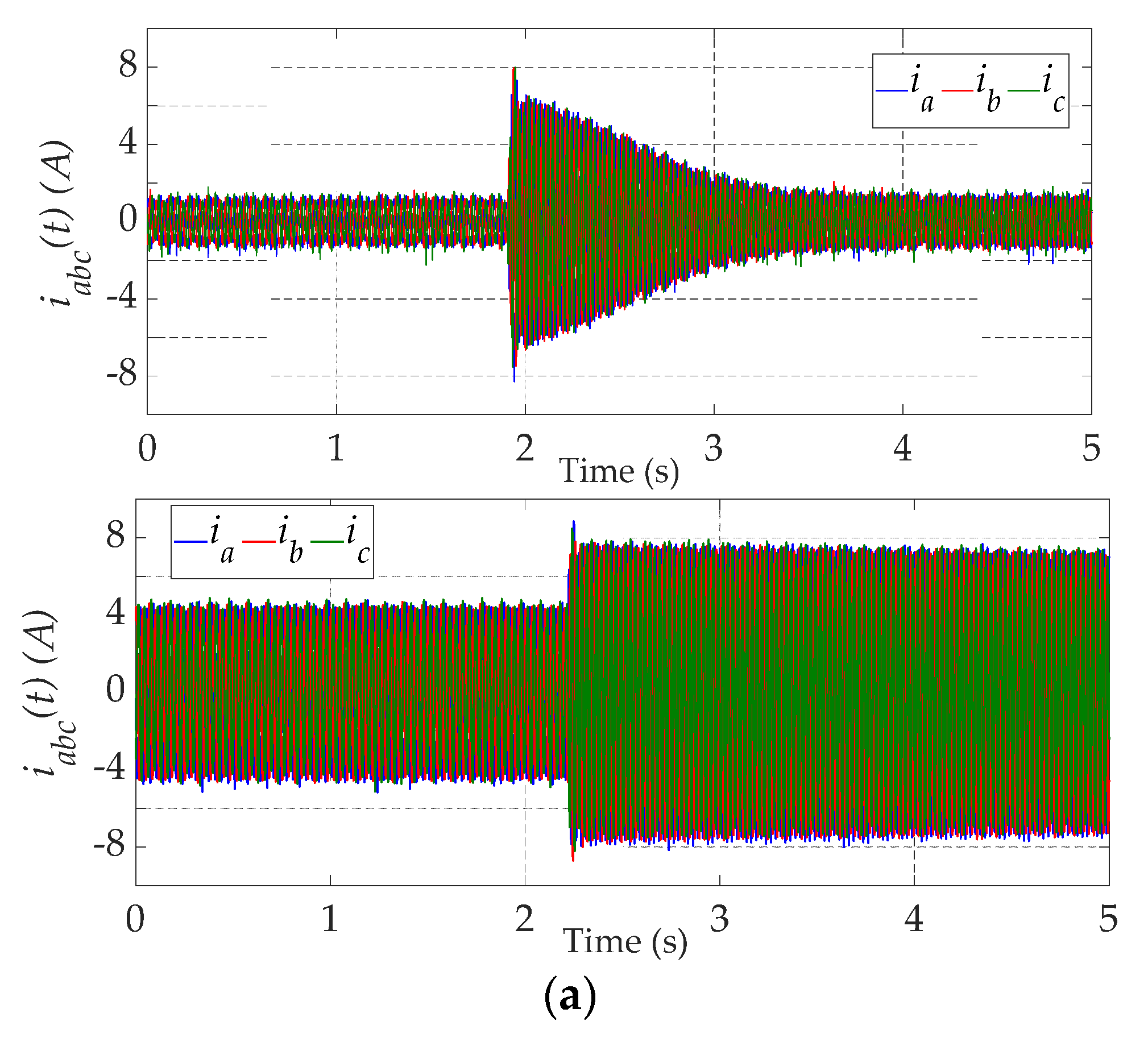

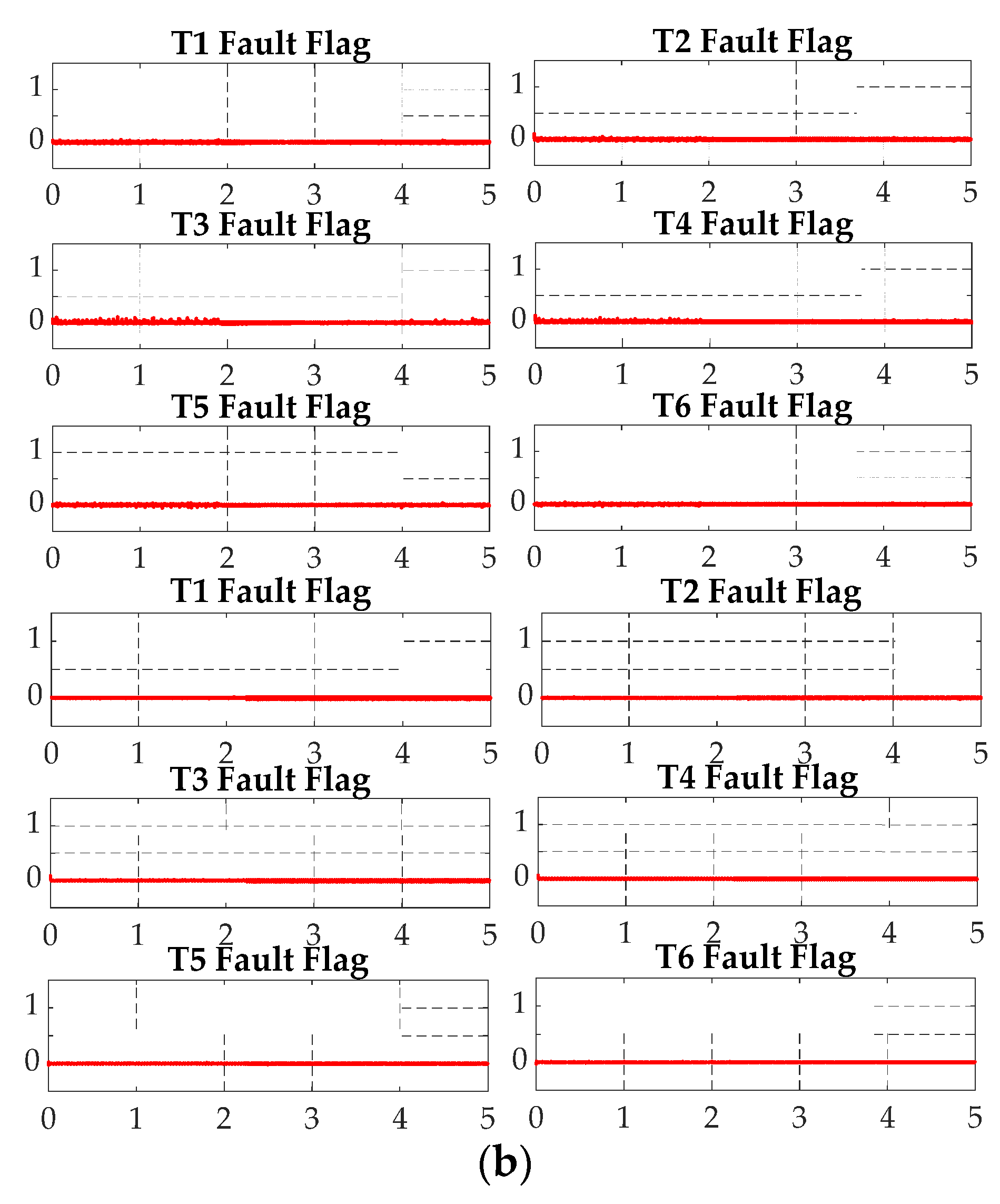

4.1. Robustness under Operating Point Variations

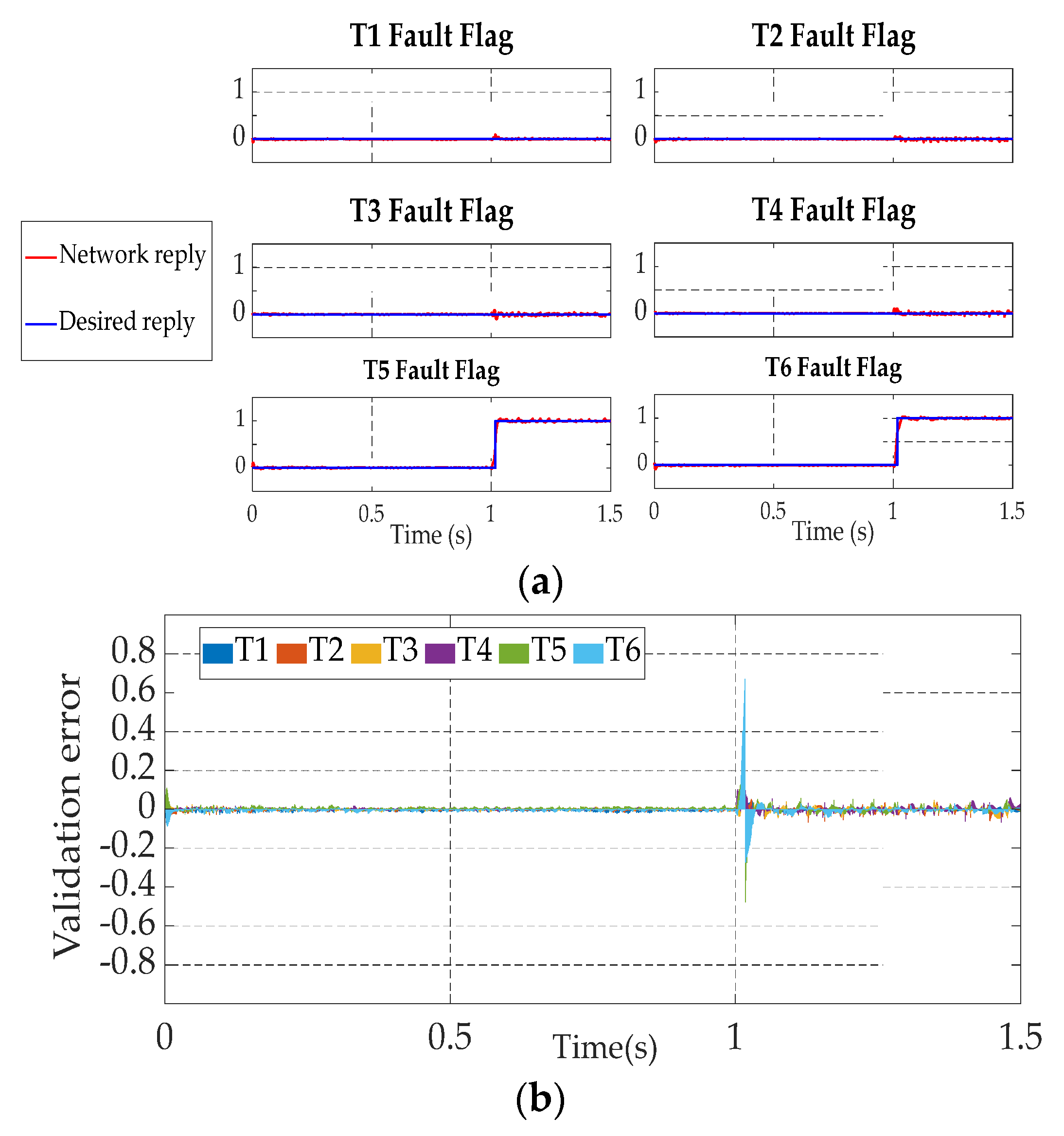

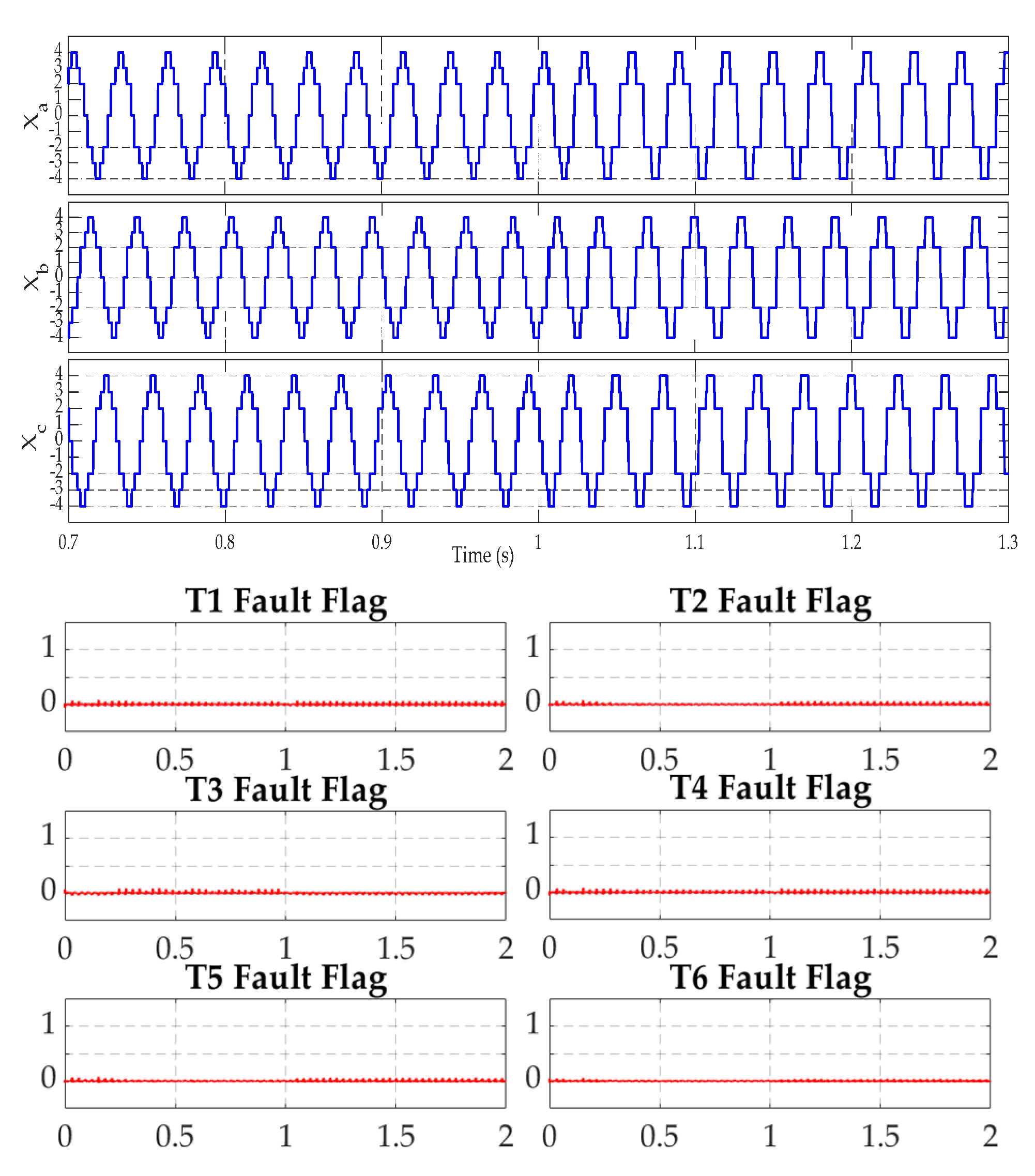

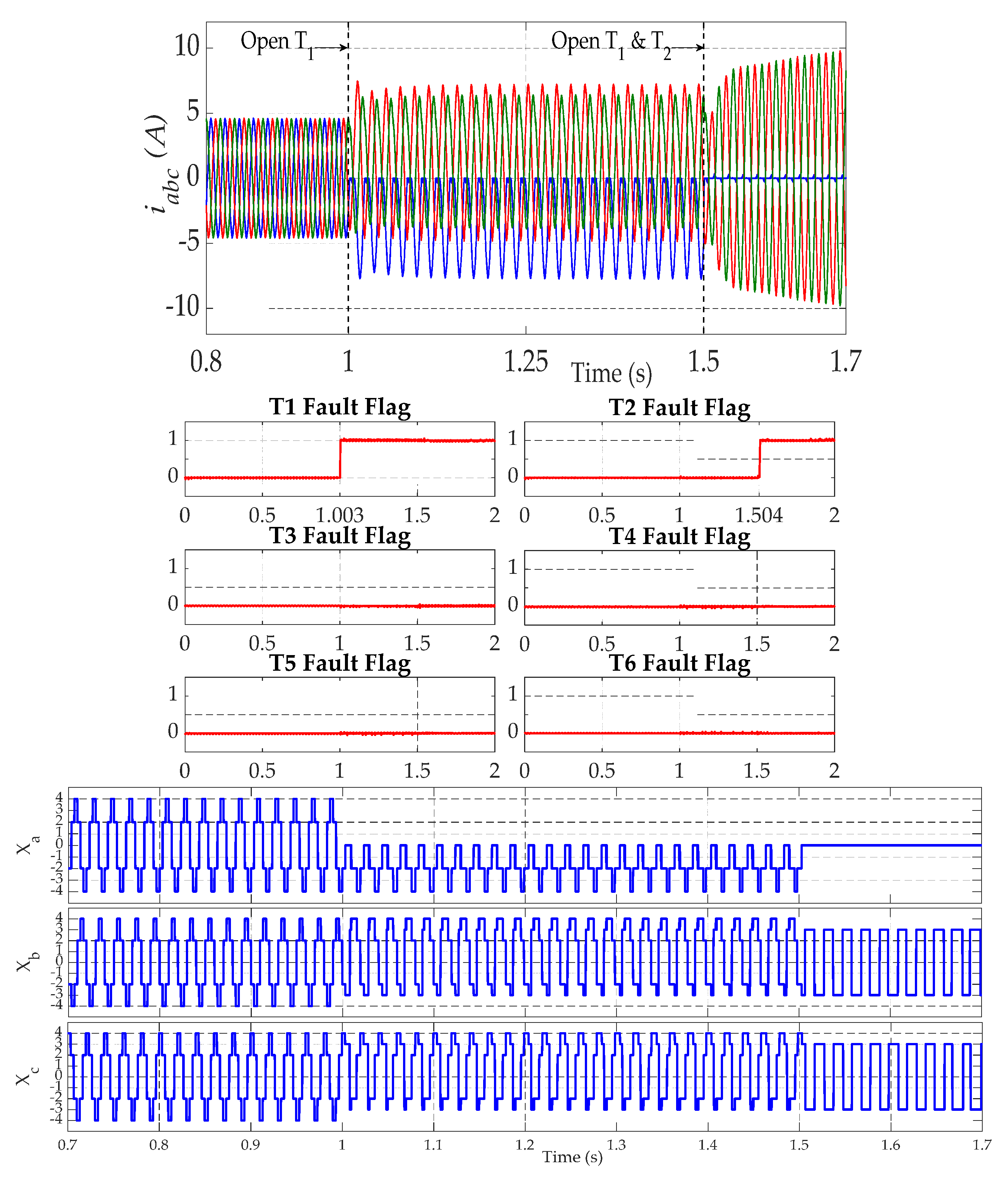

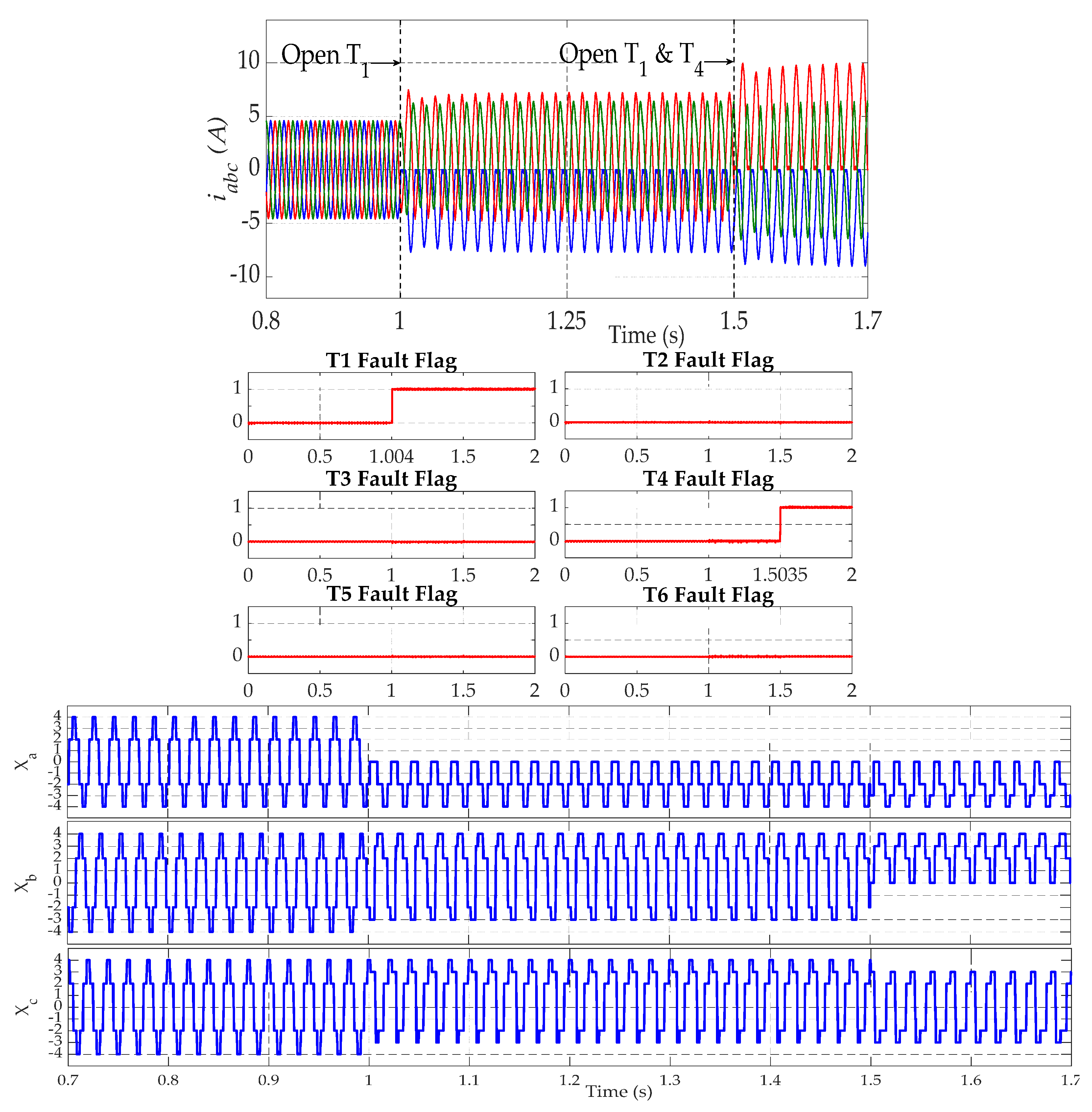

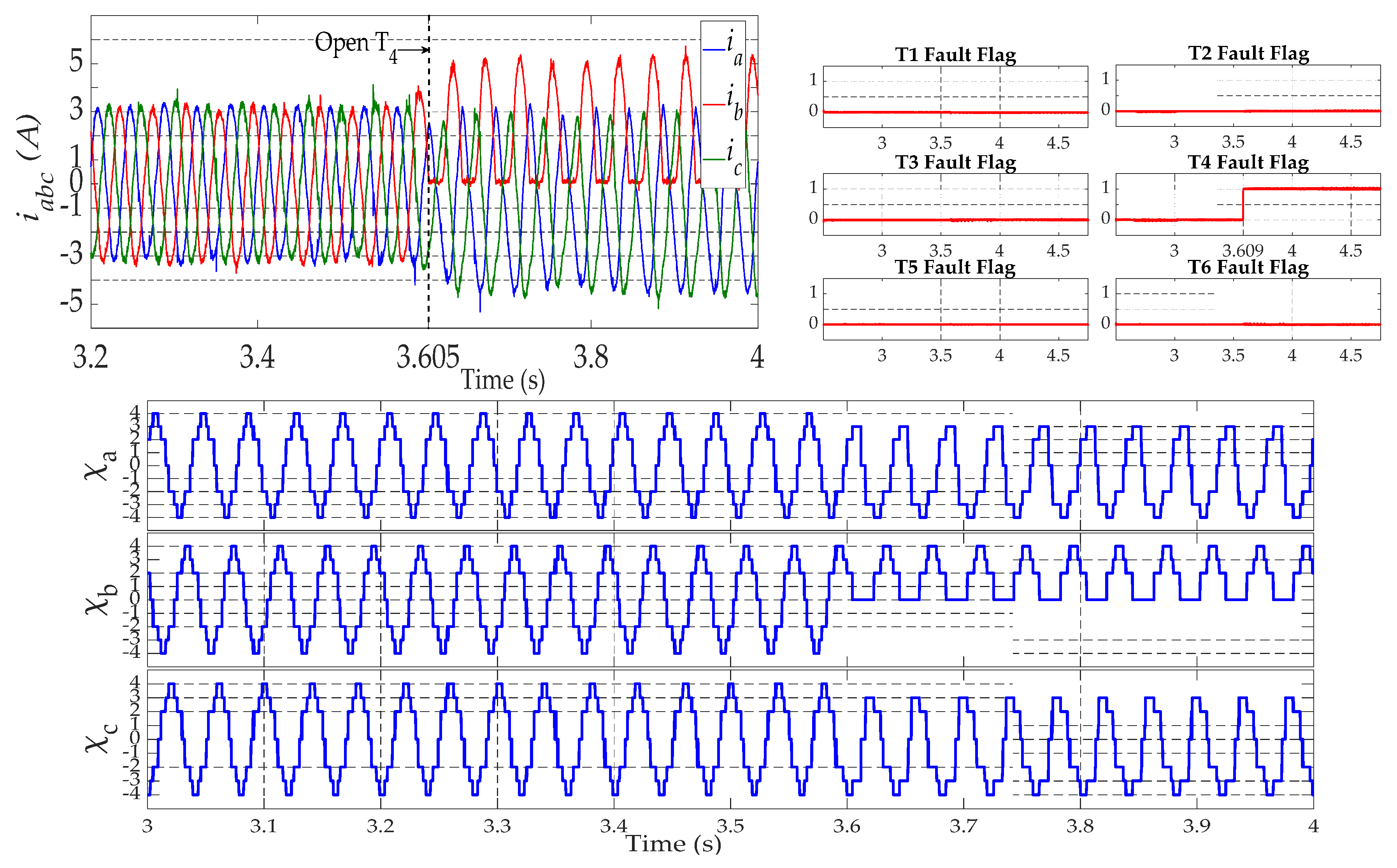

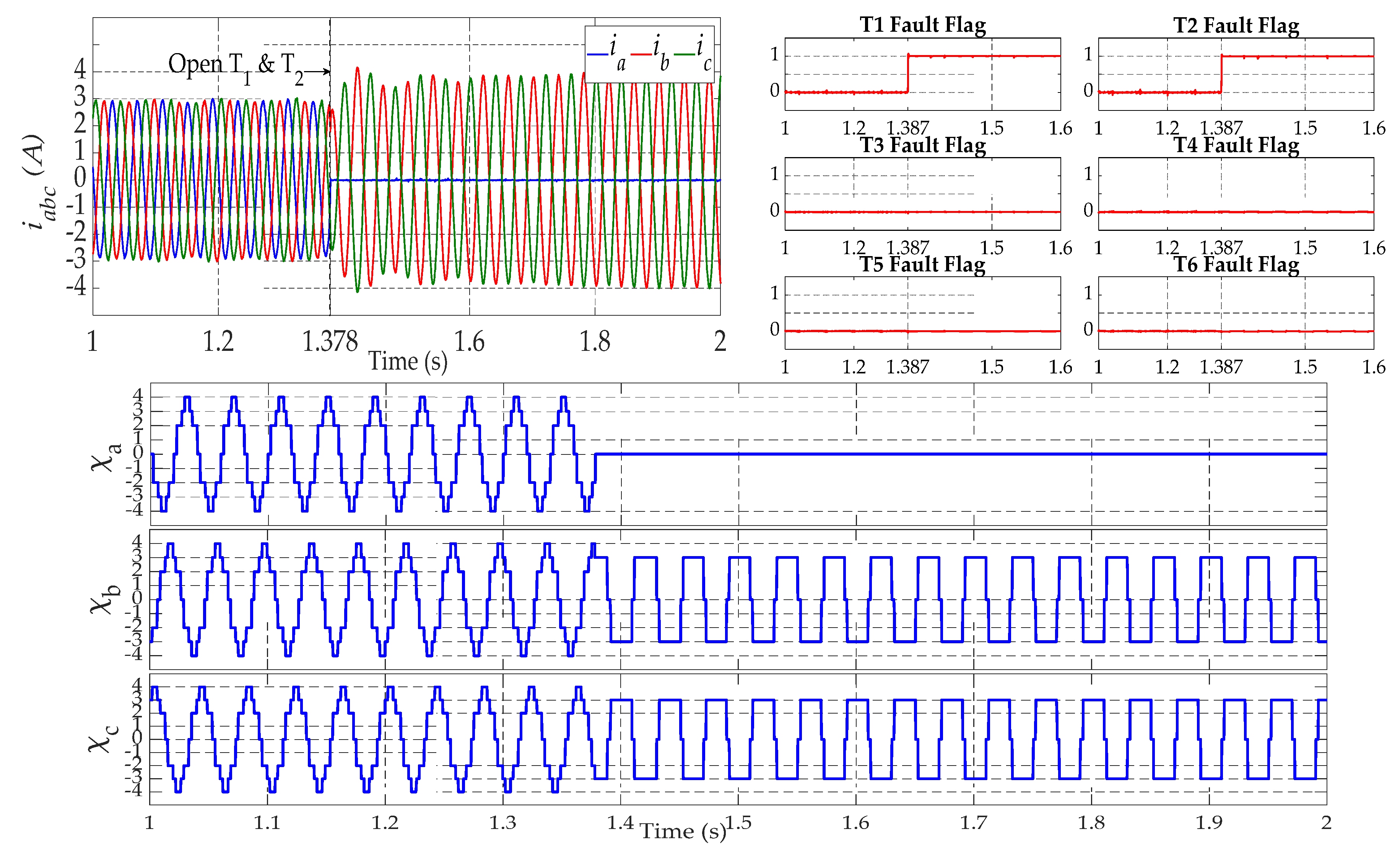

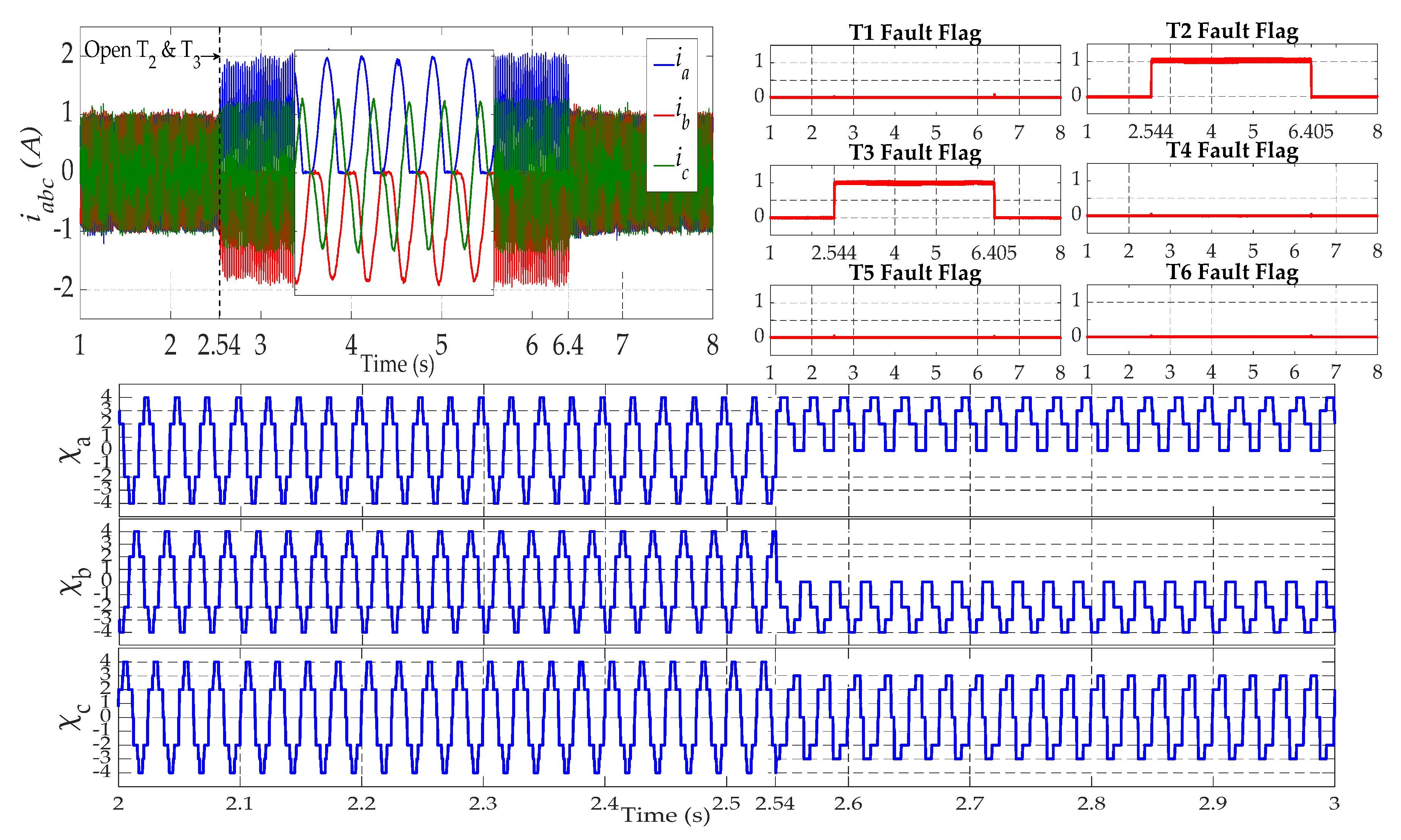

4.2. Open-Switch Fault Detection

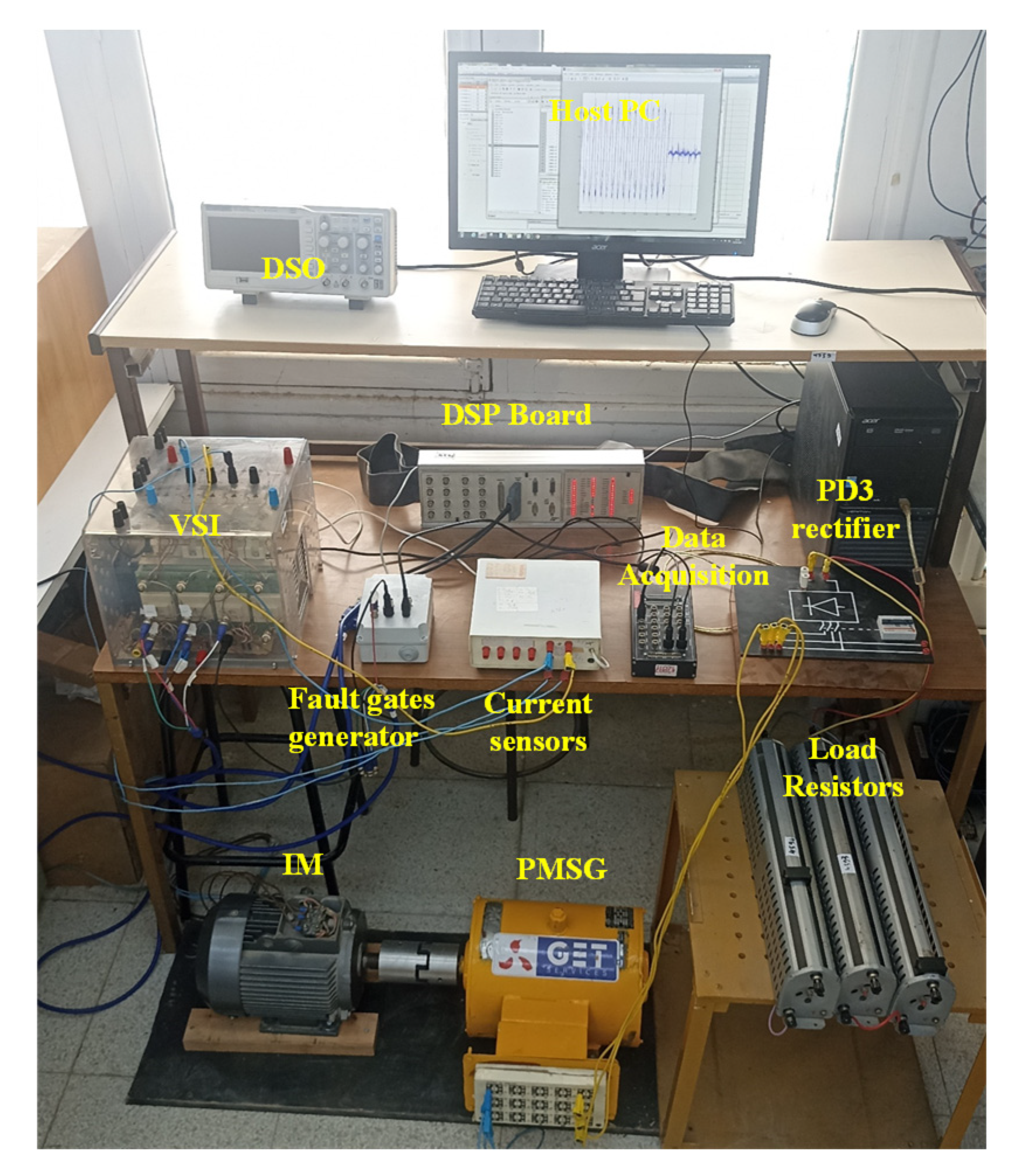

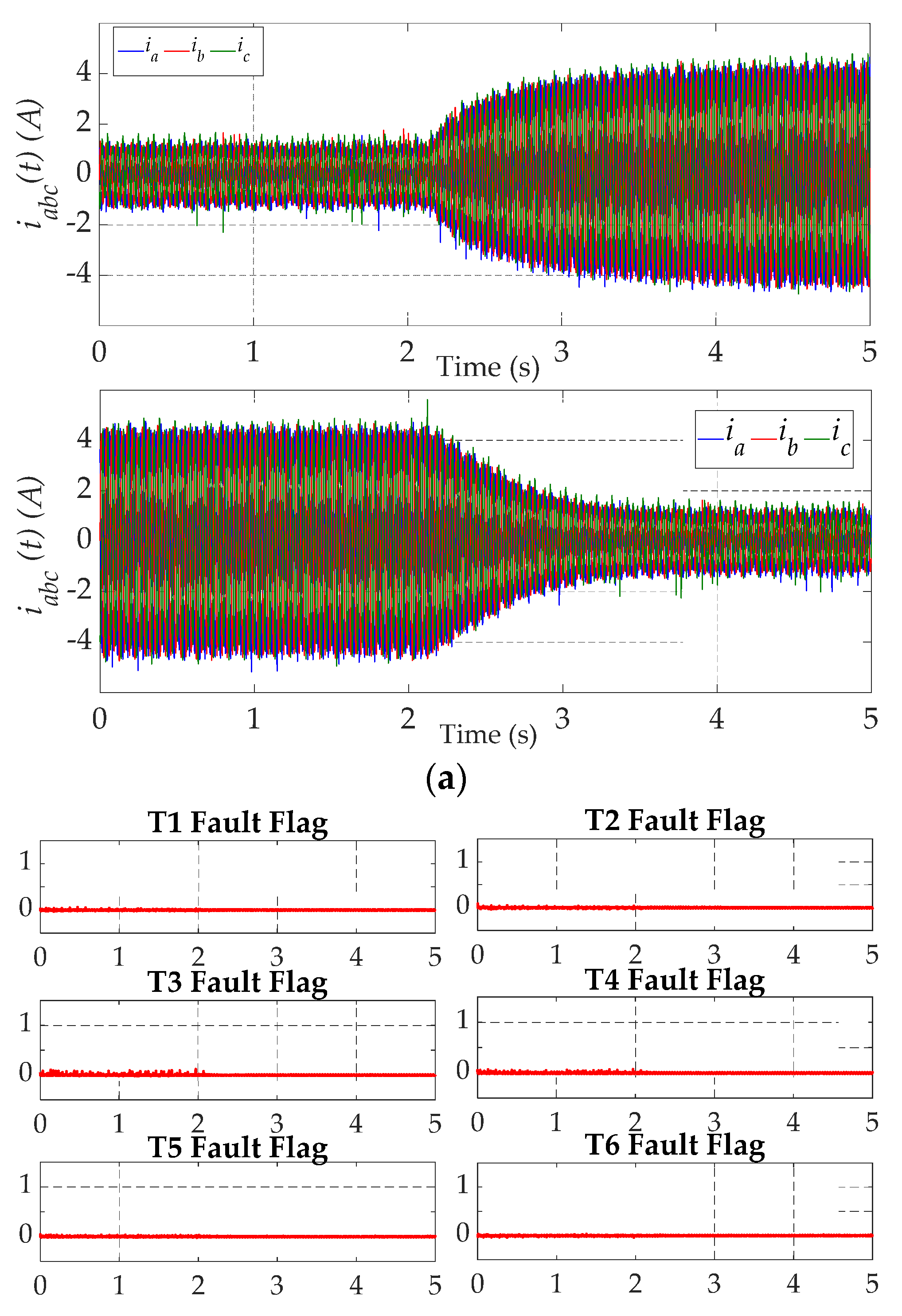

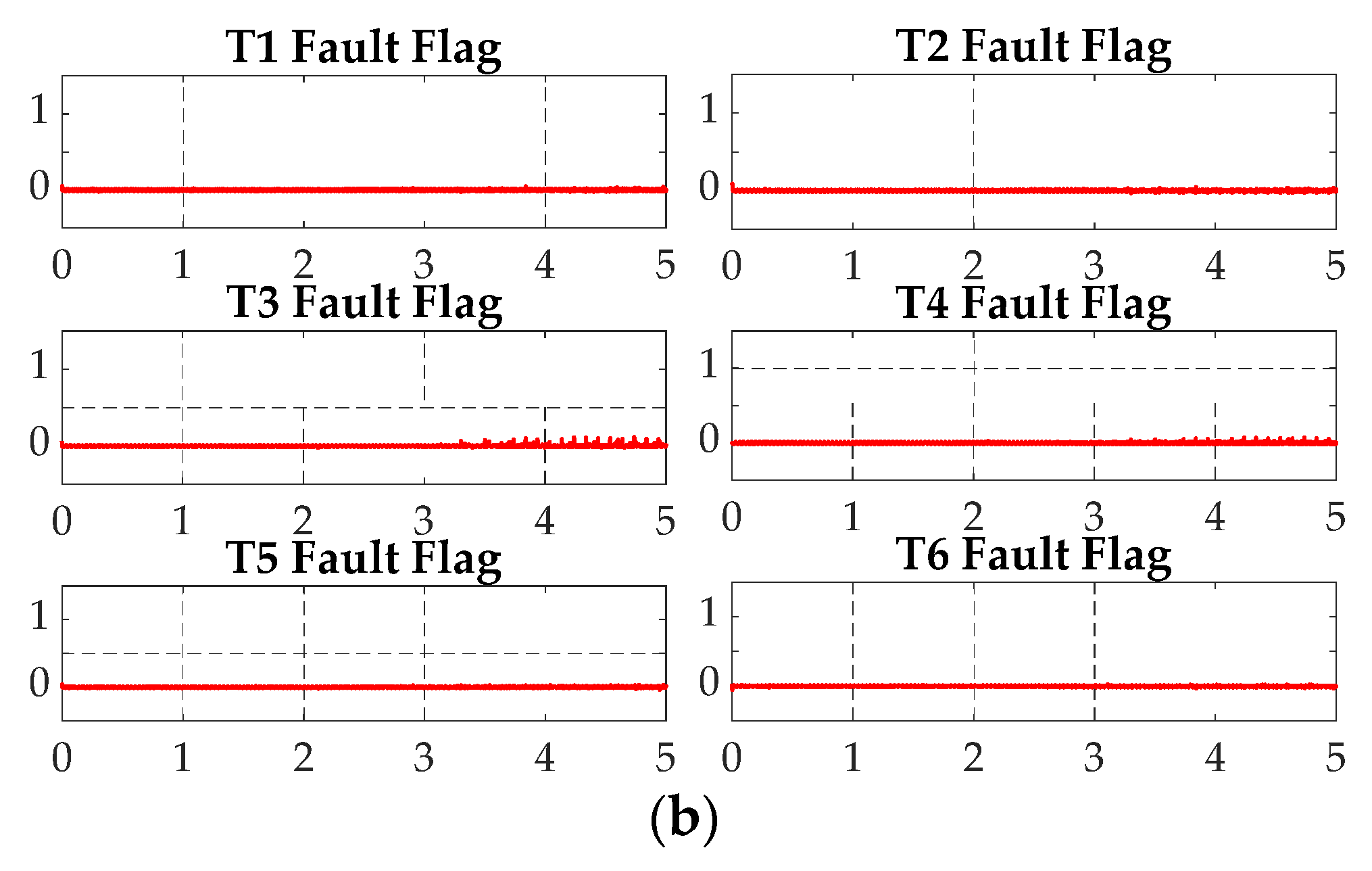

5. Experimental Results

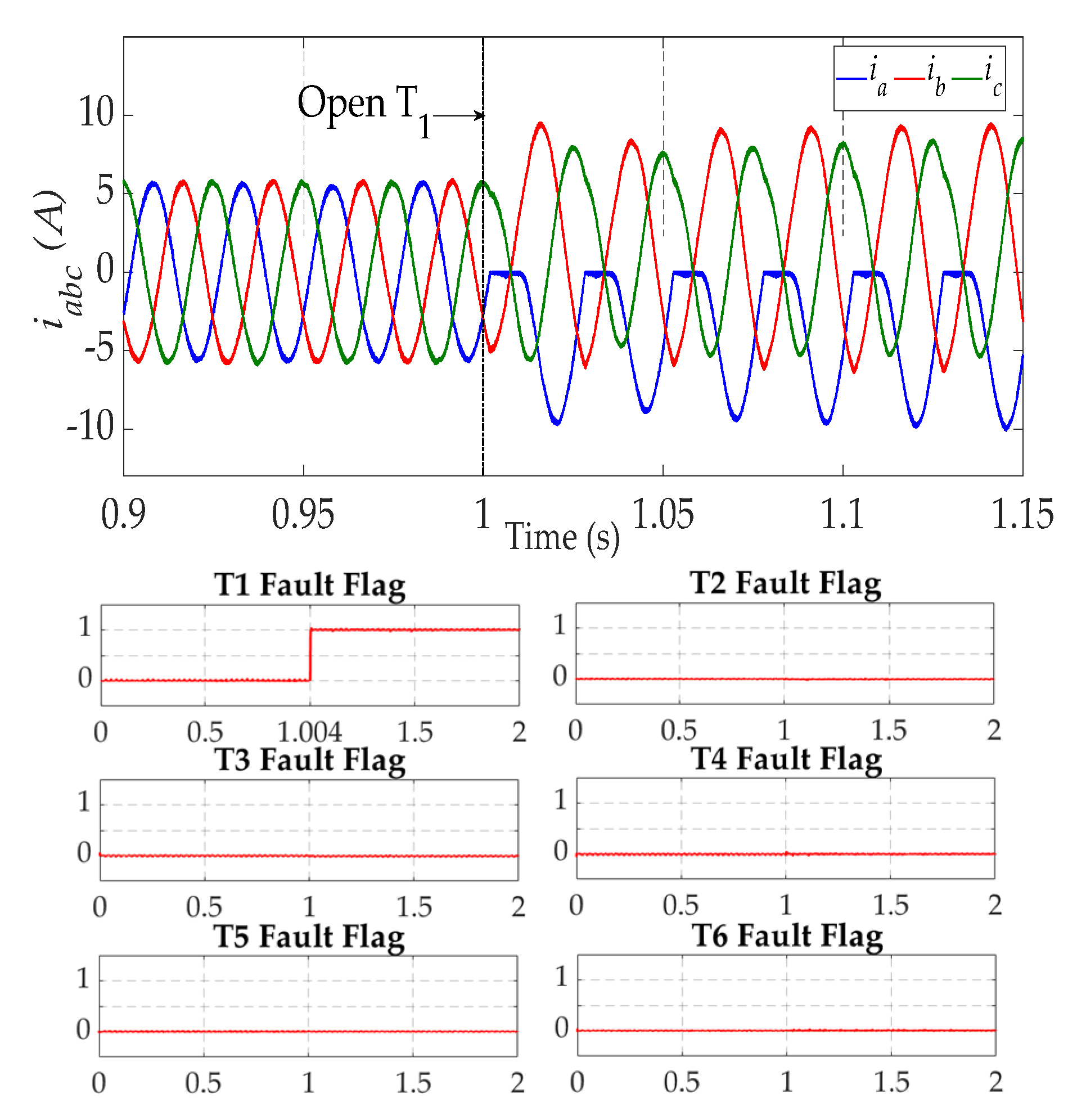

5.1. Robustness under Operating Point Variations

5.2. Open-Switch Fault Detection

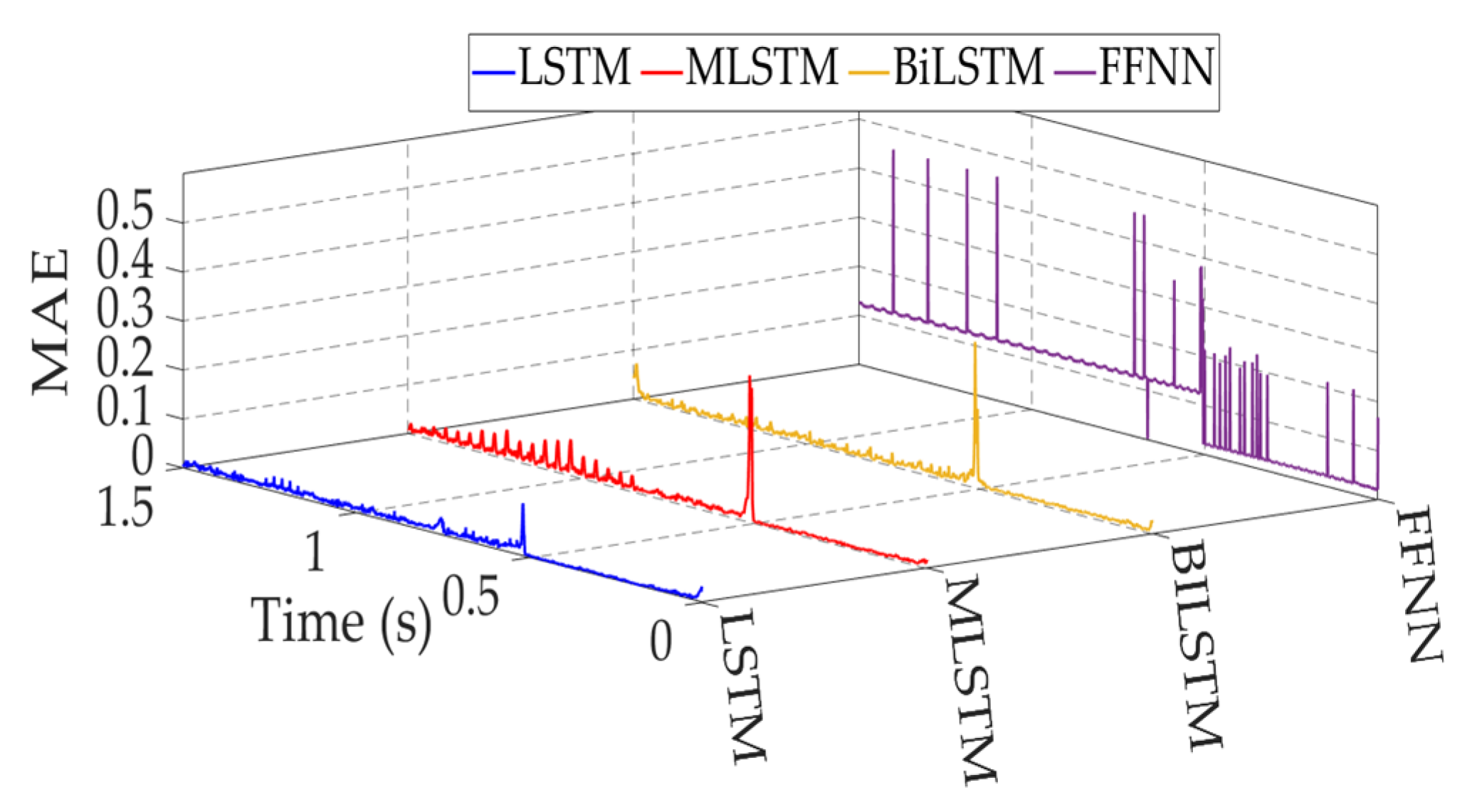

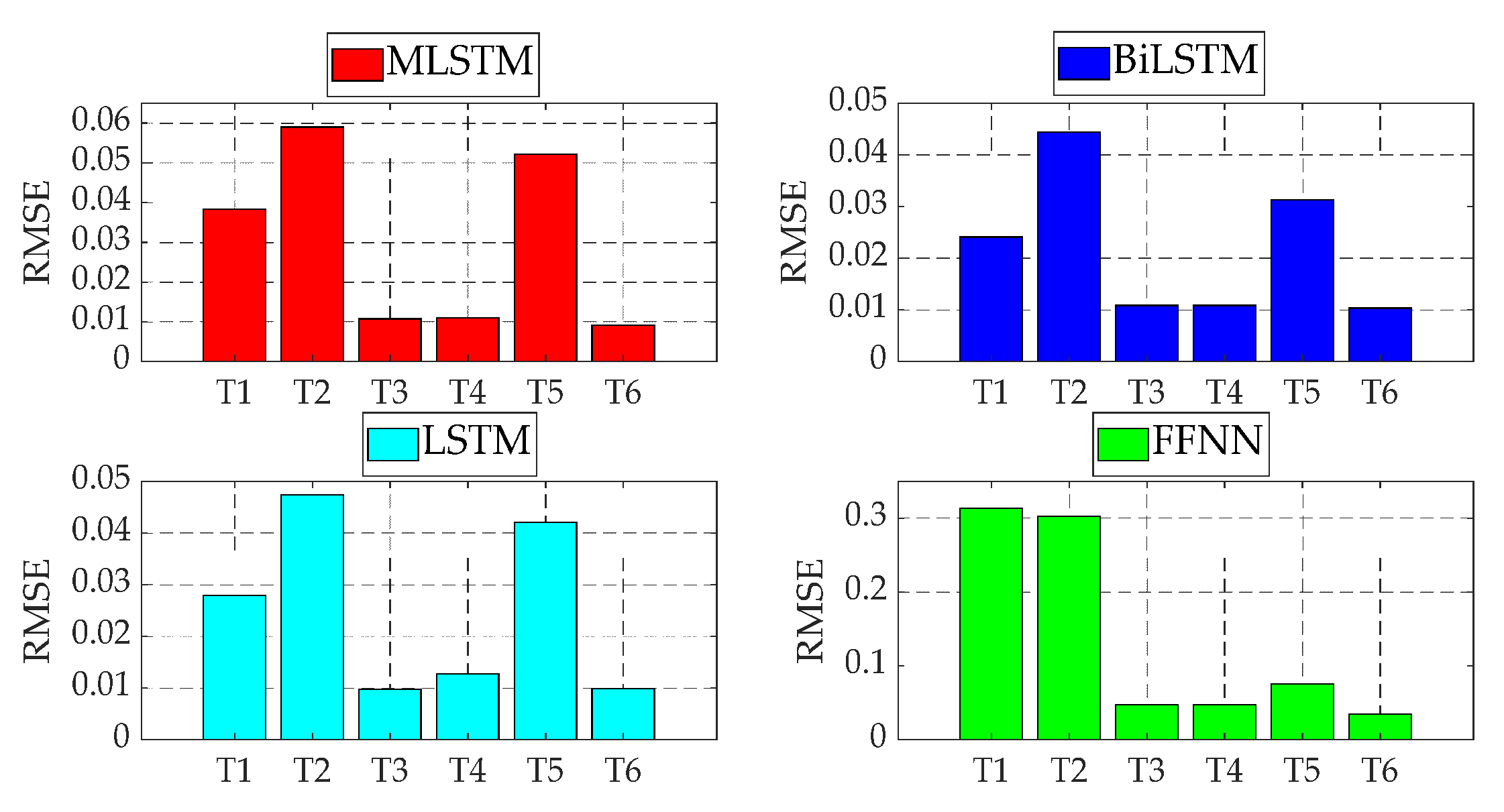

5.3. Performance Evaluation and Comparaison

6. Conclusions

References

- Yepes, A.-G.; Lopez, O.; Gonzalez-Pietro, I.; Duran, M.-J.; Doval-Gandoy, J. A Comprehensive Survey on Fault Tolerance in Multiphase AC Drives, Part 1: General Overview Considering Multiple Fault Types. Machines 2022, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes, A.-G.; Lopez, O.; Gonzalez-Pietro, I.; Duran, M.-J.; Doval-Gandoy, J. A Comprehensive Survey on Fault Tolerance in Multiphase AC Drives, Part 2: Phase and Switch Open-Circuit Faults. Machines 2022, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Sharma, S. A literature review of IGBT fault diagnostic and protection methods for power inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2009, 45, 1770–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Weili, L.; Zhigang, W. Influence of Inverter Open Circuit Fault on Multiple Physical Quantities in the PMSM. IEEE Trans. on Power Electron. 2022, 38, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, U.T.; Blaabjerg, F.; Lee, K.B. Study and handling methods of power IGBT module failures in power electronic converter systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 2517–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowska-Kowalska, T.; Wolkiewicz, M.; Pietrzak, P.; Skowron, M.; Ewert, P.; Tarchała, G.; Krzysztofiak, M.; Kowalski, C.T. Fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant control of PMSM drives–state of the art and future challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 59979–60024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Luo, G.; Gong, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, S. An Embedded Fault-Tolerant Control Method for Single Open-Switch Faults in Standard PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 8476–8487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, V.F.; Cordeiro, A.; Foito, D.; Pires, A.J. Fault-Tolerant Multilevel Converter to Feed a Switched Reluctance Machine. Machines 2022, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jlassi, I.; Estima, J.O.; El Khil, S.K.; Bellaaj, N.B.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Multiple open-circuit faults diagnosis in back-to-back converters of PMSG drives for wind turbine systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 2689–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jlassi, I.; Estima, J.O.; El Khil, S.K.; Bellaaj, N.B.; Cardoso, A.J.M. A Robust observer-based method for IGBTs and current sensors fault diagnosis in voltage-source inverters of PMSM drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 2894–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Zheng, W.; Wang, J.; Chai, Y.; Ma, M. A Simultaneous Diagnosis Method for Power Switch and Current Sensor Faults in Grid-Connected Three-Level NPC Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AN, Q.-T.; Sun, L.; Sun, L.-Z. Current residual vector-based open-switch fault diagnosis of inverters in PMSM drive systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 2814–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamouri, R.; Trabelsi, M.; Boussek, M.; M’Sahli, F. Mixed model-based and signal-based approach for open-switches fault diagnostic in sensorless speed vector controlled induction motor drive using sliding mode observer. IET Power Electron. 2019, 12, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sun, J.; Cui, P.; Lu, Y.; Lu, M.; Yu, Y. A Fast and Robust Open-Switch Fault Diagnosis Method for Variable-Speed PMSM System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 2598–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Liu, Z.; Tasiu, I.; Chen, T. Fault Diagnosis and Tolerance with Low Torque Ripple for Open-Switch Fault of IM Drives. IEEE Trans. Transportation Elec. 2020, 15, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, N.M.A.; Estima, J.O.; Cardoso, A.J.M. A voltage-based approach without extra hardware for open-circuit fault diagnosis in close-loop PWM AC regenerative drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 4960–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Hanbing, D.; Lin, J.; Su, M. Active Common-Mode Voltage-Based Open-Switch Fault Diagnosis of Inverters in IM-Drive Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, H.; Bai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B. Fast transistor open circuit faults diagnosis in grid tied three phase VSIs based on average bridge arm pole to pole voltages and error adaptive thresholds. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 8040–8051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wheeler, P.; Watson, A.J.; Costabeber, A.; Wang, B.; Ren, Y.; Bai, Z.; Ma, H. A Fast Diagnosis Method for Both IGBT Faults and Current Sensor Faults in Grid-Tied Three-Phase Inverters with Two Current Sensors. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 5267–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Pan, Y. A Novel Diagnostic Method for Multiple Open-Circuit Faults of Voltage-Source Inverters Based on Output Line Voltage Residuals Analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 68, 1343–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. A Real-Time Open-Circuit Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Hybrid Model Flux Observer for Voltage-Source-Inverter Fed Sensorless Vector Controlled Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 2539–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S.; Huang, Y.; Hua, W. Cost Function-based Open-Phase Fault Diagnosis for PMSM Drive System with Model Predictive Current Control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 2574–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmati, B.; Jlassi, I.; Khojet El Khil, S.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Open-switch fault diagnosis in voltage source inverters of PMSM drives using predictive current errors and fuzzy logic approach. IET Power Electron. 2021, 14, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, D.; Gaoliang, F. Current Prediction Based Fast Diagnosis of Electrical Faults in PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 4622–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Du, J.; Hua, W.; Lu, W.; Bi, K.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, Q. Current-based open-circuit fault diagnosis for PMSM drives with model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 10695–10704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Xu, Y.; Zou, J.; Fang, Y.; Cai, F. A novel open-circuit fault diagnosis method for voltage source inverters with a single current sensor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 8775–8786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khil, S.K.; Jlassi, I.; Cardoso, A.J.M.; Estima, J.O.; Bellaaj, N.B. Diagnosis of open-switch and current sensor faults in PMSM drives through stator current analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 5925–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estima, J.O.; Cardoso, A.J. M. A new algorithm for real-time multiple open-circuit fault diagnosis in voltage-fed PWM motor drives by the reference current errors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2013, 60, 3496–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Yu, S.; Li, S. Open-Switch Fault Detection Based on Open-Winding Five-Phase Fault-Tolerant Permanent-Magnet Motor Drives. Machines 2022, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, R.; Cherif, B.D.E.; Bendiababdella, A.; Kaddour, A. An Open-Circuit Faults Diagnosis Approach for Three-Phase Inverters Based on an Improved Variational Mode Decomposition, Correlation Coefficients, and Statistical Indicators. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, B.; Xu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Qingli, D.; Ge, X. An Online Data-driven Method for Simultaneous Diagnosis of IGBT and Current Sensor Fault of 3-Phase PWM Inverter in Induction Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 13281–13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Xie, M. A data-driven fault diagnosis methodology in three-phase inverters for PMSM drive systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 5590–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, Y. A transferrable data-driven method for IGBT open-circuit fault diagnosis in three-phase inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 13478–13488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Ma, H. A Model-Data-Hybrid-Driven Diagnosis Method for Open-Switch Faults in Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 4965–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.A.P.; Campos-Delgado, D.U.; Espinoza-Trejo, D.R.; Valdez-Fernandez, A.A.; De Angelo, C.H. Fault diagnosis in grid-connected PV NPC inverters by a model-based and data processing combined approach. IET Power Electron. 2019, 12, 3254–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.Y.; Xiahou, K.S.; Li, M.S.; Ji, T.Y.; Wu, Q.H. Diagnosis of Multiple Open-Circuit Switch Faults Based on Long Short-Term Memory Network for DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Systems. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 2600–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Qi, W.; Ding, N.; Geng, Z. Short-time wavelet entropy integrating improved LSTM for fault diagnosis of modular multilevel converter. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 7504–7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Jiang, J.; Junjie, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C. Fault Diagnosis and Tolerance Control of Five-Level Nested NPP Converter Using Wavelet Packet and LSTM. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 1907–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Ahmed, H.O.; Darwish, M.; Nandi, A.K. Open-Circuit Fault Detection and Classification of Modular Multilevel Converters in High Voltage Direct Current Systems (MMC-HVDC) with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Method. Sensors 2021, 21, 4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.; Tehrani, K.; Jamshidi, M. A Fault Diagnosis Design Based on Deep Learning Approach for Electric Vehicle Applications. Energies 2021, 14, 6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. Battery Fault Diagnosis for Electric Vehicles Based on Voltage Abnormality by Combining the Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network and the Equivalent Circuit Model. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husari, F.; Seshadrinath, J. Stator Turn Fault Diagnosis and Severity Assessment in Converter Fed Induction Motor Using Flat Diagnosis Structure Based on Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electron. 2022. (Early Access). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lao, Z.; Hou, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, S. Mechanical fault time series prediction by using EFMSAE-LSTM neural network. Measurement 2021, 173, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Multilevel feature moving average ratio method for fault diagnosis of the microgrid inverter switch. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2017, 4, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Max training epochs | 1000 |

| Loss function optimizer (solver) | Adam |

| Initial learning rate | 0.001 |

| Loss function | RMSE |

| Gradient Threshold | 0.001 |

| Hidden units | 100 |

| Faulty Switch | FFNN | LSTM | MLSTM (3 layers) | BiLSTM | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | Td (ms) | Accuracy(%) | RMSE | MAE | Td (ms) | Accuracy(%) | RMSE | MAE | Td (ms) | Accuracy(%) | RMSE | MAE | Td (ms) | Accuracy(%) | |

| T1 | 0.2073 | 0.1268 | 1 | 32.9996 | 0.0142 | 0.0093 | 11.5 | 97.8281 | 0.0150 | 0.0101 | 11 | 97.5032 | 0.0135 | 0.0095 | 3.45 | 98.2613 |

| T2 | 0.2002 | 0.1241 | 1.1 | 34.4586 | 0.0209 | 0.0128 | 21 | 96.5231 | 0.0207 | 0.0137 | 23 | 95.7970 | 0.0192 | 0.0128 | 5.2 | 96.5596 |

| T3 | 0.1915 | 0.1222 | 1 | 34.8000 | 0.0186 | 0.0116 | 23 | 96.5823 | 0.0174 | 0.0094 | 24 | 96.8548 | 0.0178 | 0.0116 | 6 | 97.3394 |

| T4 | 0.1977 | 0.1241 | 1 | 33.5121 | 0.0160 | 0.0105 | 16 | 97.3179 | 0.0157 | 0.0102 | 13.5 | 97.5014 | 0.0146 | 0.0099 | 4.88 | 97.9273 |

| T5 | 0.1983 | 0.1235 | 1 | 33.8192 | 0.0167 | 0.0107 | 21 | 97.3560 | 0.0192 | 0.0121 | 24 | 95.1774 | 0.0158 | 0.0098 | 2.5 | 98.1525 |

| T6 | 0.2061 | 0.1242 | 1 | 33.6194 | 0.0162 | 0.0102 | 12 | 97.4939 | 0.0149 | 0.0092 | 13 | 97.0993 | 0.0132 | 0.0089 | 4.02 | 97.8641 |

| T1&T2 | 0.1369 | 0.0935 | 1 | 74.1148 | 0.0250 | 0.0109 | 14 | 98.5637 | 0.0300 | 0.0132 | 17 | 98.1124 | 0.0220 | 0.0105 | 2.57 | 98.8193 |

| T3&T4 | 0.1242 | 0.0775 | 1 | 75.8453 | 0.0244 | 0.0112 | 24 | 98.2274 | 0.0270 | 0.0126 | 19 | 96.8244 | 0.0253 | 0.0109 | 4.66 | 98.3066 |

| T5&T6 | 0.1304 | 0.0796 | 1 | 76.2560 | 0.0302 | 0.0092 | 10 | 99.3372 | 0.0278 | 0.0101 | 16 | 99.2203 | 0.0302 | 0.0101 | 3.75 | 99.4112 |

| Mean | 0.1769 | 0.1108 | 1.0111 | 47.7139 | 0.0202 | 0.0107 | 16.94 | 97.6922 | 0.0208 | 0.0111 | 17.83 | 97.1211 | 0.019 | 0.0104 | 4.11 | 98.07 |

| The bold values represent optimum evaluation metrics | ||||||||||||||||

| References | Method | Detection Time * |

Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maamouri et al. [13] | System model based Sliding Mode Observer (SMO) | 20% | -- |

| Gmati et al. [23] | Predictive current errors and Fuzzy Logic approach | 12-75% | -- |

| Chen et al. [28] | Output line voltage residuals | 5-83% | -- |

| Gou et al. [31] | Online data-driven based Random vector functional link (RVFL) | 110% | 98.83% |

| Xia et al. [33] | Machine learning based transferrable data-driven method | 100% | 96.76% |

| Xue et al. [36] | Classification open circuit faults based LSTM network | 12% | 94% |

| Proposed approach | Prediction open circuit faults based BiLSTM network | 12-30% | 98.08% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).