Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design, participants, and assessment of clinical parameters

2.2. Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

2.3. Flow cytometry staining

2.4. Flow cytometry staining

2.5. Determination of plasma levels of cytokines/chemokines (LEGENDPlex)

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics of patients with cardiovascular disease and symptomatic acute SARS-CoV-2 infection

3.2. Characterization of immune cell subsets in peripheral blood using a 36-color spectral flow cytometry panel

3.3. SARS-CoV2-infected CVD patients showed significant differences in the distribution and the phenotype of immune cell populations compared to uninfected CVD patients

3.4. Chemokine and cytokine profiling showed significant differences between SARS-CoV-2-infected and uninfected CVD patients

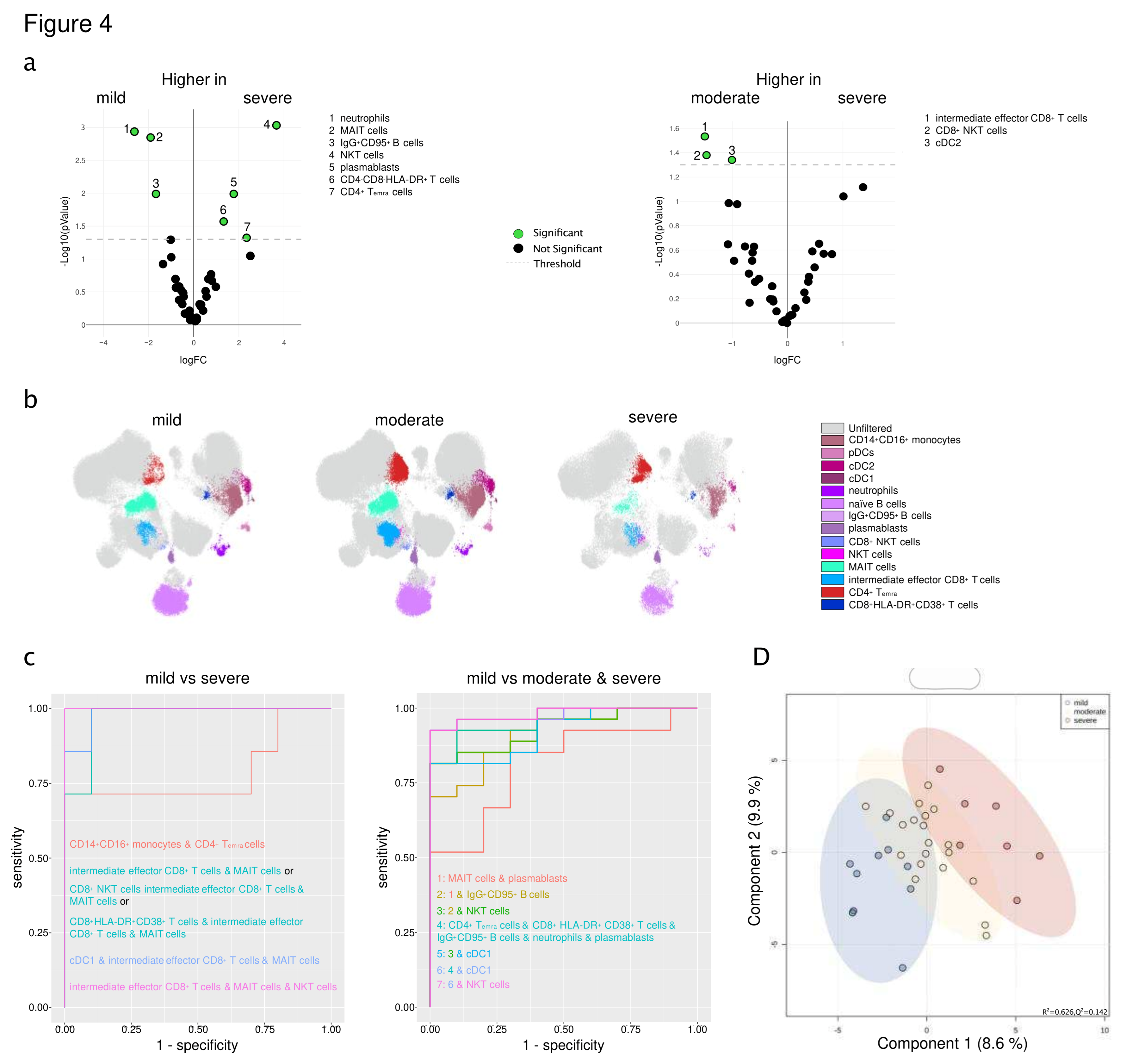

3.5. An immune signature of SARS-CoV-2-infected CVD patients is associated with the severity of COVID-19

3.6. Immune signature is predictive of severity and the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koutsakos, M.; Kedzierska, K. A race to determine what drives COVID-19 severity. Nature 2020, 583, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, Y.; Ling, Y.; Lu, G.; Liu, F.; Yi, Z.; Jia, X.; Wu, M.; Shi, B.; Xu, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, B.; Jiang, L.; Yu, S.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, G.; Wang, S.; Chen, S.; Lu, H. Viral and host factors related to the clinical outcome of COVID-19. Nature 2020, 583, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thevarajan, I.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; Koutsakos, M.; Druce, J.; Caly, L.; Sandt CE van de Jia, X.; Nicholson, S.; Catton, M.; Cowie, B.; Tong, S.Y.C.; Lewin, S.R.; Kedzierska, K. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19. Nat Med 2020, 26, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuri-Cervantes, L.; Pampena, M.B.; Meng, W.; Rosenfeld, A.M.; Ittner, C.A.G.; Weisman, A.R.; Agyekum, R.S.; Mathew, D.; Baxter, A.E.; Vella, L.A.; Kuthuru, O.; Apostolidis, S.A.; Bershaw, L.; Dougherty, J.; Greenplate, A.R.; Pattekar, A.; Kim, J.; Han, N.; Gouma, S.; Weirick, M.E.; Arevalo, C.P.; Bolton, M.J.; Goodwin, E.C.; Anderson, E.M.; Hensley, S.E.; Jones, T.K.; Mangalmurti, N.S.; Prak, E.T.L.; Wherry, E.J.; Meyer, N.J.; Betts, M.R. Comprehensive mapping of immune perturbations associated with severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol 2020, 5, eabd7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, D.; Giles, J.R.; Baxter, A.E.; et al. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science 2020, 369, eabc8511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.-X.; Tang, X.-J.; Shi, Q.-L.; Li, Q.; Deng, H.-J.; Yuan, J.; Hu, J.-L.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, F.-J.; Su, K.; Zhang, F.; Gong, J.; Wu, B.; Liu, X.-M.; Li, J.-J.; Qiu, J.-F.; Chen, J.; Huang, A.-L. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, C.; Wong, P.; Klein, J.; et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature 2020, 584, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, A.G.; Lorenc, A.; Barrio I del M del; et al. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MDPCH; MDYW; MDPXL; PhDPLR; MDPJZ; MDYH; MDPLZ; MSGF; MDc, J.X.; PhDXG; MDPZC; MDTY; MDJX; MDYW; MDPWW; MDPXX; MDWY; MDHL; MDML; MSYX; PhDPHG; PhDPLG; MDPJX; MDPGW; MDPRJ; MDPZG; PhDQJ; PhDPJW; MDPBC Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506.

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; Guan, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Tu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Cao, B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, R.J.; Manuel, A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. The Lancet Respiratory, 2020; 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Mangalmurti, N.; Hunter, C.A. Cytokine Storms: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 2020, 53, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiology ES, of. ESC Guidance for the Diagnosis and Management of CV Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020:1–119.

- Oren, O.; Yang, E.H.; Molina, J.R.; Bailey, K.R.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Kopecky, S.L. Cardiovascular Health and Outcomes in Cancer Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. The American journal of cardiology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.-Y.; Redwood, S.; Prendergast, B.; Chen, M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 1798–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.W. SARS-CoV-2: a potential novel etiology of fulminant myocarditis. Herz 2020, 45, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; Gong, W.; Liu, X.; Liang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, H.; Yang, B.; Huang, C. Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Jama Cardiol 2020, 5, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, J.-Y.; Lim, P.L.; Marimuthu, K.; Sadarangani, S.P.; Ling, L.M.; Ang, B.S.P.; Chan, M.; Leo, Y.-S.; Vasoo, S. De-isolating COVID-19 Suspect Cases: A Continuing Challenge. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, ciaa179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Bai, H.; Chen, X.; Gong, J.; Li, D.; Sun, Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Zirlik, A.; Ley, K. Beyond vascular inflammation—recent advances in understanding atherosclerosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015, 72, 3853–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Ley, K. Immunity and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2019, 124, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrar, H.; Bekkering, S.; Stienstra, R.; Netea, M.G.; Riksen, N.P. Innate immune memory in cardiometabolic disease. Cardiovasc Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swirski, F.K.; Nahrendorf, M. Cardioimmunology: the immune system in cardiac homeostasis and disease. Nature 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollard, K.J.; Geissmann, F. Monocytes in atherosclerosis: subsets and functions. Nature reviews Cardiology 2010, 7, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P.; Orecchioni, M.; Ley, K. How the immune system shapes atherosclerosis: roles of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DesPrez, K.; McNeil, J.B.; Wang, C.; Bastarache, J.A.; Shaver, C.M.; Ware, L.B. Oxygenation Saturation Index Predicts Clinical Outcomes in ARDS. Chest 2017, 152, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; Lancellotti, P.; Muraru, D.; Picard, M.H.; Rietzschel, E.R.; Rudski, L.; Spencer, K.T.; Tsang, W.; Voigt, J.-U. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015, 28, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parasuraman, S.; Walker, S.; Loudon, B.L.; Gollop, N.D.; Wilson, A.M.; Lowery, C.; Frenneaux, M.P. Assessment of pulmonary artery pressure by echocardiography—A comprehensive review. IJC Hear Vasc 2016, 12, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. Arxiv 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gassen, S.V.; Callebaut, B.; Helden, M.J.V.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Demeester, P.; Dhaene, T.; Saeys, Y. FlowSOM: Using self-organizing maps for visualization and interpretation of cytometry data. Brinkman RR, Aghaeepour Nima, Finak Greg, Gottardo Raphael, Mosmann Tim, Scheuermann RH, eds. Cytometry Part B: Clinical Cytometry 2015, 87, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzara, S.; Rossi, R.L.; Grifantini, R.; Donizetti, S.; Abrignani, S.; Bombaci, M. CombiROC: an interactive web tool for selecting accurate marker combinations of omics data. Sci Rep-uk 2017, 7, 45477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombaci, M.; Rossi, R.L. Proteomics for Biomarker Discovery, Methods and Protocols. Methods Mol Biology 2019, 1959, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Boccard, J.; Rutledge, D.N. A consensus orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) strategy for multiblock Omics data fusion. Anal Chim Acta 2013, 769, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, L.M.; Lannigan, J.; Jaimes, M.C. OMIP-069: Forty-Color Full Spectrum Flow Cytometry Panel for Deep Immunophenotyping of Major Cell Subsets in Human Peripheral Blood. Cytom Part A 2020, 97, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reizis, B. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells: Development, Regulation, and Function. Immunity 2019, 50, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Martins., V.M.; Teixeira., M.; Santos., R.D.; Stein, R. COVID-19 and Thromboinflammation: Is There a Role for Statins? Clinics 2021, 76, e2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blankenberg, S.; Tiret, L.; Bickel, C.; Peetz, D.; Cambien, F.; Meyer, J.; Rupprecht, H.J.; Investigators, A. Interleukin-18 Is a Strong Predictor of Cardiovascular Death in Stable and Unstable Angina. Circulation 2002, 106, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, T.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Alexander, R.W.; Anderson, J.L.; Cannon, R.O.; Criqui, M.; Fadl, Y.Y.; Fortmann, S.P.; Hong, Y.; Myers, G.L.; Rifai, N.; Smith, S.C.; Taubert, K.; Tracy, R.P.; Vinicor, F. Prevention C for DC and, Association AH. Markers of Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2003, 107, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, T.; Baba, M.; Nishimura, M.; Kakizaki, M.; Takagi, S.; Yoshie, O. The T Cell-directed CC Chemokine TARC Is a Highly Specific Biological Ligand for CC Chemokine Receptor 4*. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 15036–15042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinks, T.S.C.; Zhang, X.-W. MAIT Cell Activation and Functions. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wei, G.; Liu, D. CD19: a biomarker for B cell development, lymphoma diagnosis and therapy. Exp Hematology Oncol 2012, 1, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, W.H.; Wong, K.L.; Shimasaki, N.; Teo, E.C.Y.; Quek, J.K.S.; Yong, H.X.; Diong, C.P.; Bertoletti, A.; Linn, Y.C.; Wong, S.C. CD16 is indispensable for antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity by human monocytes. Sci Rep-uk 2016, 6, 34310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ni, H.; Zhao, P.; Chen, G.; Xu, B.; Yuan, L. The role of CXCR3 and its ligands in cancer. Frontiers Oncol 2022, 12, 1022688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilk, A.J.; Lee, M.J.; Wei, B.; et al. Multi-omic profiling reveals widespread dysregulation of innate immunity and hematopoiesis in COVID-19. J Exp Med 2021, 218, e20210582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breton, G.; Mendoza, P.; Hägglöf, T.; Oliveira, T.Y.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Gaebler, C.; Turroja, M.; Hurley, A.; Caskey, M.; Nussenzweig, M.C. Persistent cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Exp Med, 2021; 218. [Google Scholar]

- Kvedaraite, E.; Hertwig, L.; Sinha, I.; et al. Major alterations in the mononuclear phagocyte landscape associated with COVID-19 severity. P Natl Acad Sci Usa 2021, 118, e2018587118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsakos, M.; Rowntree, L.C.; Hensen, L.; et al. Integrated immune dynamics define correlates of COVID-19 severity and antibody responses. Cell Reports Medicine 2021, 2, 100208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, A.; Radrizzani, D.; Viganò, P.; Mazzone, A.; Brando, B. Decrease of Non-Classical and Intermediate Monocyte Subsets in Severe Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cytom Part A 2020, 97, 887–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, Y.M.; Schrama, T.J.; Ruijten, R.; et al. Stratification of hospitalized COVID-19 patients into clinical severity progression groups by immuno-phenotyping and machine learning. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, K.A.L.; Langnau, C.; Günter, M.; Pöschel, S.; Gekeler, S.; Petersen-Uribe, Á.; Kreisselmeier, K.-P.; Klingel, K.; Bösmüller, H.; Li, B.; Jaeger, P.; Castor, T.; Rath, D.; Gawaz, M.P.; Autenrieth, S.E. Numbers and phenotype of non-classical CD14dimCD16+ monocytes are predictors of adverse clinical outcome in patients with coronary artery disease and severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cardiovasc Res 2021, 117, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winheim, E.; Rinke, L.; Lutz, K.; Reischer, A.; Leutbecher, A.; Wolfram, L.; Rausch, L.; Kranich, J.; Wratil, P.R.; Huber, J.E.; Baumjohann, D.; Rothenfusser, S.; Schubert, B.; Hilgendorff, A.; Hellmuth, J.C.; Scherer, C.; Muenchhoff, M.; Bergwelt-Baildon M von Stark, K.; Straub, T.; Brocker, T.; Keppler, O.T.; Subklewe, M.; Krug, A.B. Impaired function and delayed regeneration of dendritic cells in COVID-19. Plos Pathog 2021, 17, e1009742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; To, K.K.-W.; Wong, Y.-C.; Liu, L.; Zhou, B.; Li, X.; Huang, H.; Mo, Y.; Luk, T.-Y.; Lau, T.T.-K.; Yeung, P.; Chan, W.-M.; Wu, A.K.-L.; Lung, K.-C.; Tsang, O.T.-Y.; Leung, W.-S.; Hung, I.F.-N.; Yuen, K.-Y.; Chen, Z. Acute SARS-CoV-2 infection impairs dendritic cell and T cell responses. Immunity 2020, 53, 864–877.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georg, P.; Astaburuaga-García, R.; Bonaguro, L.; et al. Complement activation induces excessive T cell cytotoxicity in severe COVID-19. Cell 2022, 185, 493–512.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizurini, D.M.; Hottz, E.D.; Bozza, P.T.; Monteiro, R.Q. Fundamentals in Covid-19-Associated Thrombosis: Molecular and Cellular Aspects. Frontiers Cardiovasc Medicine 2021, 8, 785738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, B.A.; Elemam, N.M.; Maghazachi, A.A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors during COVID-19 infection. Comput Struct Biotechnology J 2021, 19, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiser, A.; Mueller, A.; Wise, E.L.; McDonagh, E.M.; Petit, S.J.; Saran, N.; Clark, P.C.; Williams, T.J.; Pease, J.E. The Chemokine Receptor CXCR3 Is Degraded following Internalization and Is Replenished at the Cell Surface by De Novo Synthesis of Receptor. J Immunol 2008, 180, 6713–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, G.; Lindquist, J.A.; Arhel, N.; Felder, E.; Karl, S.; Haas, T.L.; Fulda, S.; Walczak, H.; Kirchhoff, F.; Debatin, K.-M. CD95 co-stimulation blocks activation of naive T cells by inhibiting T cell receptor signaling. J Exp Med 2009, 206, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, S.R.; Ho, A.; Pius, R.; et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. Bmj 2020, 370, m3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.-J.; Liang, W.-H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 2020, 55, 2000547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | All patients (n=94) |

|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Age (y) | 58 (42-74) |

| Male | 45 (47.9) |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 25 (22-28.2) |

| ICU admission | 11 (11.7) |

| ARDS | |

| mild | 19 (20.2) |

| moderate | 8 (8.5) |

| severe | 5 (5.3) |

| Horovitz Index | |

| HI > 300 mmHg | 70 (74.5) |

| HI 201 - 300 mmHg | 4 (4.3) |

| HI 101 - 200 mmHg | 11 (11.7) |

| HI ≤ 100 mmHg | 9 (9.6) |

| High flow 02 Therapy | 5 (5.3) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 8 (8.5) |

| Vasopressor | 6 (6.4) |

| Lymphocyte count at Nadir (1000/µl) | 0.8 (0.6-1.2) |

| Bacterial Co-Infection | 14 (14.9) |

| Dialysis | 5 (5.3) |

| Acute hepatic injury | 4 (4.3) |

| Symptoms on admission | |

| Cough | 18 (19.1) |

| Dyspnea | 18 (19.1) |

| Fever | 20 (21.3) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Arterial hypertension | 43 (45.8) |

| Dyslipidemia | 30 (31.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (11.7) |

| Current smokers | 11 (11.7) |

| Obesity | 21 (22.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14 (14.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7 (7.4) |

| COPD | 3 (3.2) |

| Malignoma | 8 (8.5) |

| NYHA | |

| 1 | 10 (10.6) |

| 2 | 2 (2.1) |

| 3 | 2 (2.1) |

| Parameters of echocardiography | |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 22 (23.4) |

| Right ventricular function | 3 (3.2) |

| Right ventricular dilatation | 13 (13.8) |

| PE | 17 (18.1) |

| Bilateral nodular opacities | 19 (20.2) |

| Ground-glass opacities | 9 (9.6) |

| Peribronchial thickening | 2 (2.1) |

| Focal consolidations | 9 (9.6) |

| Venous congestion | 6 (6.4) |

| Atelectasis | 1 (1.1) |

| Parameters of electrocardiography | |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 76 (67-84) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 140 (130-151.3) |

| Heart Rhythm | |

| Sinus rhythm | 85 (90.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 (4.3) |

| PM | 1 (1.1) |

| SVT | 1 (1.1) |

| Laboratory parameters and biomarkers | |

| Leukocytes (1000/µL) | 6925 (5120-8715) |

| Lymphocytes (1000/µL) | 1315 (705-1977) |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.3 (12.1-13.9) |

| Platelets (1000/µL) | 224.5 (166.8-297.3) |

| INR (%) | 1 (1-1.1) |

| PTT (s) | 24 (22-27) |

| D-Dimer (µg/dL) | 0.8 (0.6-1.8) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.7-1) |

| GFR-MDRD (ml/m2) | 79.8 (52.8-101.8) |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 (137-140) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1 (0.1-3.3) |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0.1 (0.1-0.2) |

| IL-6 | 24.3 (8.7-34.5) |

| hs TNI (ng/dL) | 7.5 (3-18) |

| NT-pro-BNP (ng/L) | 202 (95.3-887.3) |

| CK (U/L) | 100 (66-175) |

| AST (U/L) | 24 (16.8-39) |

| ALT (U/L) | 22 (16-41) |

| LDH (U/L) | 211 (171-276) |

| HbA1c (%) | 6 (5.5-6.4) |

| Concomitant cardiac medication at study entry | |

| Oral anticoagulation | 11 (11.7) |

| ACE-I or ARB | 36 (38.3) |

| Diuretics | 15 (16.0) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 12 (12.8) |

| Beta-blockers | 23 (24.5) |

| Statins | 29 (30.9) |

| ASA | 23 (24.5) |

| P2Y12 inhibitors | 5 (5.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).