Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

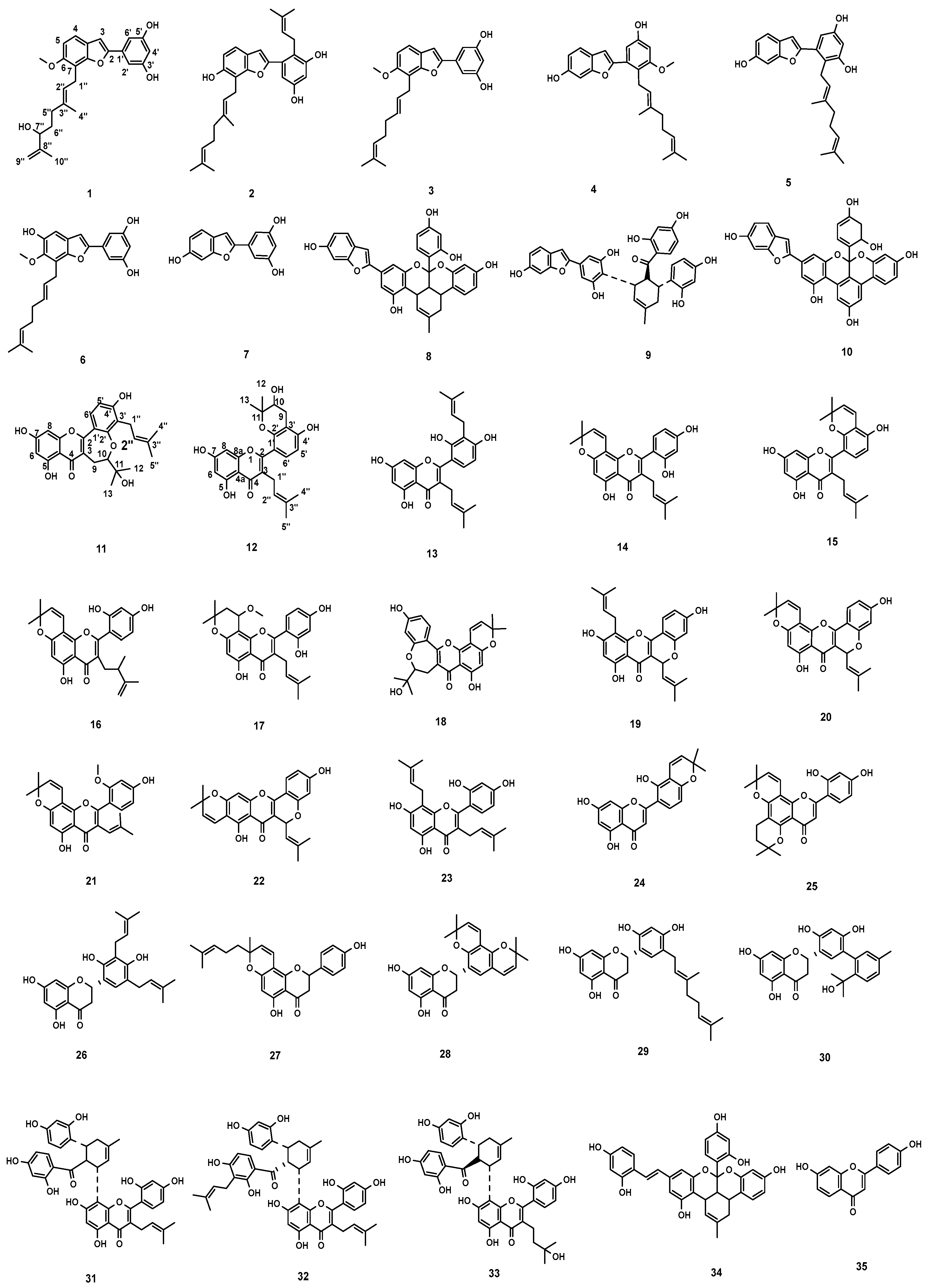

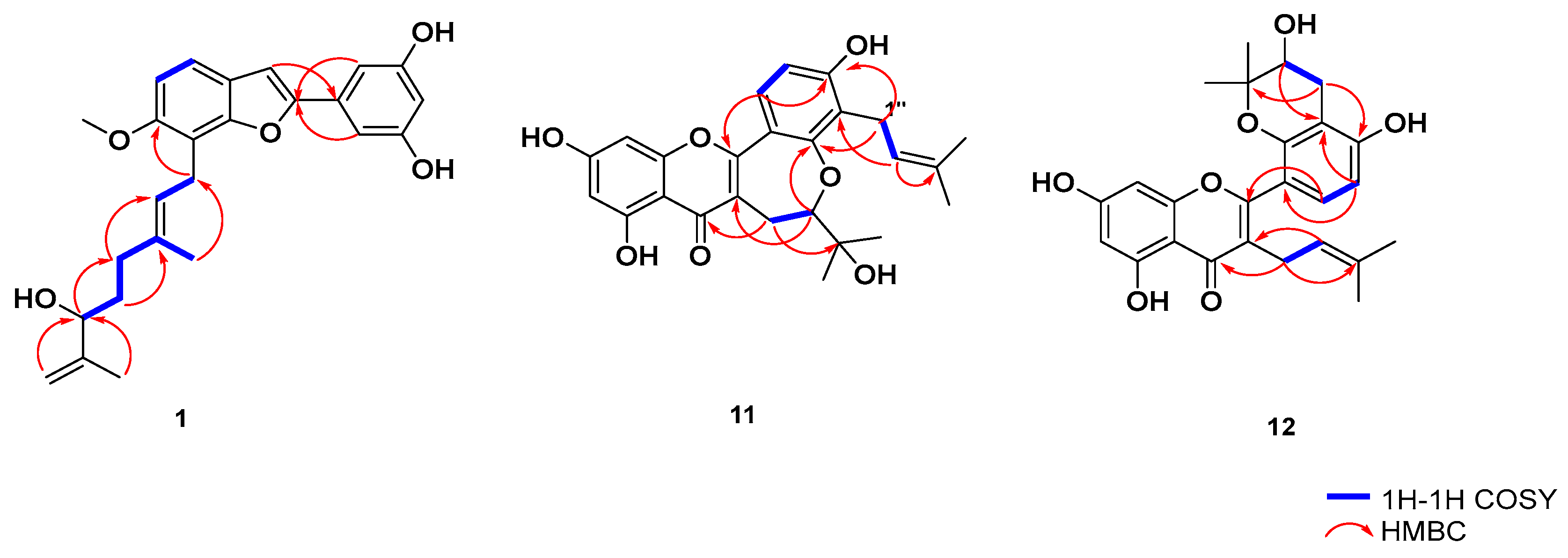

2.1. Isolation and Structure Elucidation

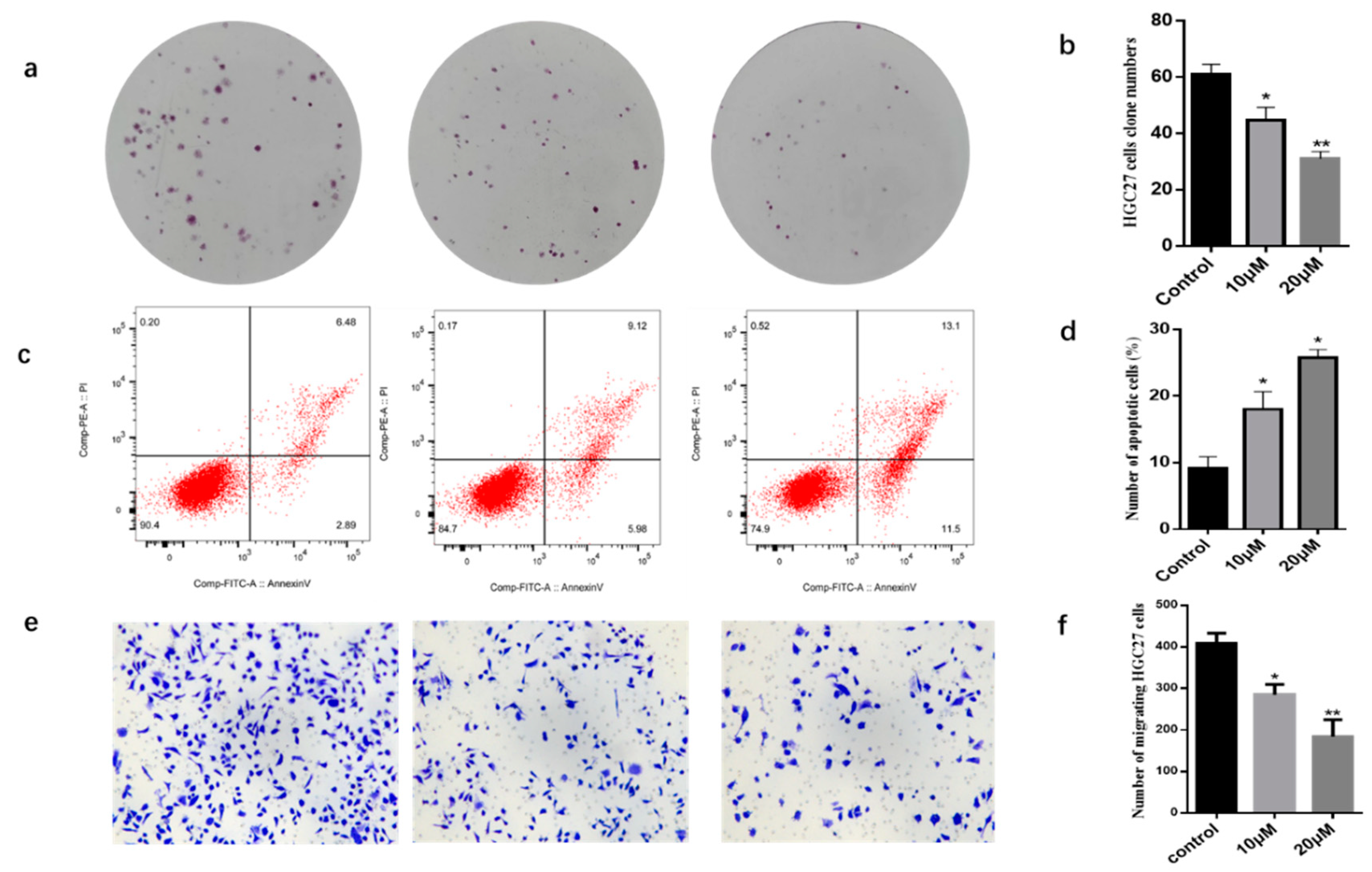

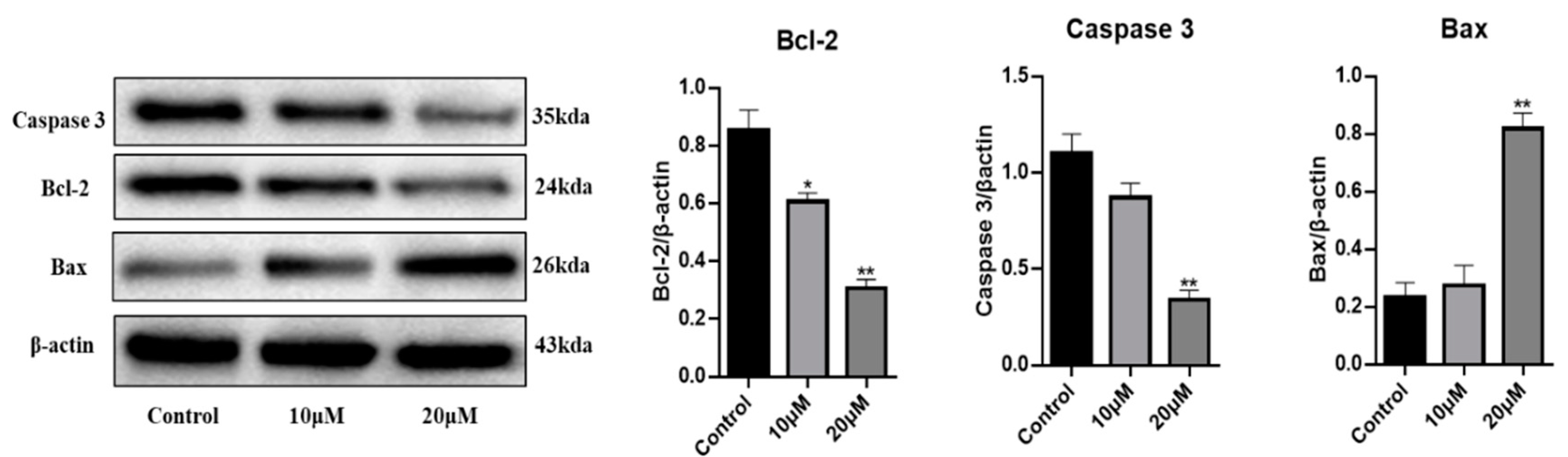

2.2. Biological Activities of Compounds against HGC27 Cancer Cells

| 11a | 12b | |||

| No. | δH (J in Hz) | δC | δH (J in Hz) | δC |

| 2 | 158.6 | 163.1 | ||

| 3 | 115.7 | 122.1 | ||

| 4 | 179.7 | 183.1 | ||

| 4a | 102.0 | 105.4 | ||

| 5 | 157.3 | 163.2 | ||

| 6 | 6.12 brs | 98.9 | 5.91a s | 99.7a |

| 7 | 161.3 | 165.8 | ||

| 8 | 6.33 brs | 93.6 | 6.00a s | 94.0a |

| 8a | 157.3 | 157.1 | ||

| 9α | 2.74 dd (16.2, 6.0) | 23.0 | 2.61 dd (16.8, 5.4) | 27.5 |

| 9β | 3.00 dd (16.2, 3.6) | 2.95 dd (16.8, 7.4) | ||

| 10 | 3.99 dd (6.0, 3.6) | 91.5 | 3.80 dd (16.2, 6.0) | 70.2 |

| 11 | 70.9 | 78.1 | ||

| 12 | 1.18 s | 27.3 | 1.36 s | 25.8 |

| 13 | 1.29 s | 24.1 | 1.28 s | 20.8 |

| 1′ | 114.0 | 113.8 | ||

| 2′ | 159.4 | 154.7 | ||

| 3′ | 119.9 | 110.3 | ||

| 4′ | 156.4 | 157.0 | ||

| 5′ | 6.74 d (9.0) | 110.7 | 6.42 d (8.4) | 109.9 |

| 6′ | 7.67 d (9.0) | 126.8 | 6.98 d (8.4) | 129.5 |

| 1′′ | 3.36*d (6.0) | 22.5 | 3.08 dd (7.2, 5.4) | 24.8 |

| 2′′ | 5.13 t (7.2) | 123.2 | 5.07 t (7.2) | 122.6 |

| 3′ | 130.3 | 132.8 | ||

| 4′′ | 1.61 s | 25.5 | 1.34 s | 17.6 |

| 5′′ | 1.71.s | 17.9 | 1.58 s | 25.8 |

| 5-OH | 13.02 s |

3. Experimental

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

3.4. Spectroscopic Data

3.5. Cell Culture

3.6. Cytotoxicity Assay and CCK-8 Assay

3.7. Colony Formation Assay

3.8. Cell Apoptosis Assay

3.9. Transwell Migration Assay

3.10. Western Blot Analysis

4. Conclusions

References

- State Pharmacopoeia Committee. Chinese Pharmacopoeia; China Medical Pharmaceutical Science and Technology Publishing House: Beijing, China. 2010, p182.

- Asano, N.; Yamashita, T.; Yasuda, K.; Ikeda, K.; Kizu, H.; Kameda, Y.; Kato, A.; Nash, R.J.; Lee, H.S.; Ryu, K.S. Polyhydroxylated alkaloids isolated from mulberry trees (Morus alba L.) and silkworms (Bombyx mori L.). J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2001, 49, 4208–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čulenová, M.; Sychrová, A.; Hassan, S.T.S.; Berchová-Bímová, K.; P. Svobodová, P.; Helclová, A.; Michnová, H.; Hošek, J. Multiple In vitro biological effects of phenolic compounds from Morus alba root bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 248, 112296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Li, D.Z.; Chen, R.Y.; Yu, D.Q. A new benzo-furanolignan and a new flavonol derivative from the stem of Morus australis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2008, 19, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Takara, K.; Toyozato, T.; Wada, K. A novel bioactive chalcone of Morus australis inhibits tyrosinase activity and melanin biosynthesis in B16 melanoma cells. J. Oleo Sci. 2012, 61, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.H.; Wang, J.J.; Lin, H.C.; Wang, J.P.; Lin, C.N. Chemistry and biological activities of constituents from Morus australis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 1999, 1428, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.F.; Zhang, Q.J.; Chen, R.Y.; Yu, D.Q. Four new flavonoids from Morus australis. J. Asian. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 14 3, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Tang, Y.B.; Chen, R.Y.; Yu, D.Q. Three new cytotoxic Diels-Alder-type adducts from Morus australis. Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Zheng, Z.F.; Chen, R.Y.; Yu, D.Q. Two new dimeric stilbenes from the stem bark of Morus australis. J. Asian. Nat. Prod. Res, 2009, 11, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, T.; Nihei, M.; Nagai, H.; Fukushi, H.; Tabata, K.; Suzuki, T.; Akihisa, T. Albanol A from the root bark of Morus alba L. induces apoptotic cell death in HL60 human leukemia cell line. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Lee, H S.; Oh, W K.; Ahn J S. Inhibition of sangginon G isolated from Morus alba on the metastasis of cancer cells. Chin. Herb. Med. (2011), 3, 23–26.

- Agabeyli, R A.; Antimutagenic activities extracts from leaves of the Morus alba, Morus nigra and their mixtures. Intl. J. Biol. 2012, 4, 166–172.

- Devi, B.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, D.; Jeet, K. Morus alba L inn: a phytopharmacological review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharma. Sci. 2013, 5, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.S.; Hong, S.; Lee, H.J.; Mar, W.; Lee, D.A. A new prenylated flavanone from the root bark of Morus. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2013, 34, 2528–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.R.; Wang, S.Y.; Sun, W.; Wei, C. Isoliquiritigenin inhibits proliferation and metastasis of MKN28 gastric cancer cells by suppressing the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3429–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.W.; Xu, Y.Q.; Lei, B.; Wang, W.X.; Ge, X.; Li, J.R. Rhein induces apoptosis of human gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells via an intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2012, 45, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, T.; Fukai, T.; Shimada, T.; Chen, I.S. Mulberrofuran D, a new isoprenoid 2-arylbenzofuran from the root barks of the mulberry tree (Morus australis Poir). Heterocycies 1982, 19, 1855–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Jin, H.G.; Lee, H.; Lee, D.S.; Woo, E.R. Phytochemical constituents of the root bark from Morus alba and their Il-6 Inhibitory activity. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2019, 25, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.L.; Zhang, X.Q.; Huang, X.J.; He, X.M.; Wang, G.C.; Ye, W.C. Chenucal constituents from root barks of Morus atropurpurea. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2010, 35, 1978–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.H.; Ryu, Y. B.; Curtis-Long, M. J.; Ryu, H. W.; Baek, Y. S.; Kang, J. E.; Lee, W.S.; Park, K.H. Tyrosinase Inhibitory polyphenols from roots of Morus Ihou. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2009, 57, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Q.; Fukai, T.; Sakagami, H.; Chang, W.J.; Yang, F.Q.; Wang, F.P.; Nomura, T. Cytotoxic flavonoids with isoprenoid groups from Morus mongolica. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X. He, X. Chao, L. Yang, C. Zhang, R. Pi, H. Zeng, G. Li, Y. Xu, Y. Lin, The research on chemical ingredients of the heartwood of root of Morus atpropurpurea, Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2014 26 (2) (2014) 193-196.

- Jung, J.W.; Koo, W.M.; Park, J.H.; Seo, K.H.; Oh, E.J.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, Y.C.; Lim, D.W.; Han, D.; Baek, N.I. Isoprenylated flavonoids from the root bark of Morus alba and their hepatoprotective and neuroprotective activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.Q.; Chen, H.; . Chen, R.Y. Study on Diels-Alder type adducts from stem bark of Morus yunanensis. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2009, 34, 286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.Q.; Wang, H.Q.; Liu, C.; Chen, R.Y. Study on anti-oxidant phenolic compounds from stem bark of Morus yunanensis. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2008, 13, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.M; Wu, D.L.; Zou, Y.X; Wang, G.C.; Zhang, X.Q.; Liao, S.T.; Sun, J.; Ye, W.C. Chemical constituents from root barks of Morus atropurpurea. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2010, 35, 1978–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, P.; Ni, G.; Guo, W.Q.; Shi, G.R.; Chen, R.Y.; Yu, D.Q. Isolation and identification of pharmaceutical chemical constituents from branches of Morus notabilis. Science of Sericulture 2016, 42, 0307–0312. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.Q.; Tang, G.H.; Lou, L.L.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, B.; Yin, S. Prenylated flavonoids as potent phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors from Morus alba: Isolation, modification, and structure-activity relationship study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 144, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Curtis-Long, M.J.; Lee, B.W.; Ryu, Y.B.; Park, K.H. Isolation of cholinesterase-Inhibiting flavonoids from Morus lhou. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2011, 59, 4589–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, C.A.; Yao, S.Y.; Xue, D.Q.; Zuo, A.; Zhang, X.M; Jiang, Z.Y.; Ma, Y.B.; Chen, J.J. New isoprenylated flavonoid from Morus alba. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2010, 35, 1560–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, T.H.; Chuang, S.K.; Hu, C.C.; Chang, C.F.; Huang, Y.C.; Lin, C.W.; Lee, Y.J. The synthesis of morusin as a potent antitumor agent. Tetrahedron. 2010, 66, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, T.; Hano, Y.; Nomura, T.; Uzawa, J. Components of root bark of cudrania tricuspidata 2. Structures of two new isoprenylated flavones, Cudraflavones A and B. Planta. Med. 1984, 50, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.S.; Yang, C.; Yue, W.P.; Zhao, H.A.; Ho, C.T.; Du, J.F.; Zhang, H.; Bai, N.S. Chemical characterization of the main bioactive polyphenols from the roots of Morus australis (mulberry). Food. Funct. 2019, 10, 6915–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, R.Y. Three new compounds from Morus nigra L. J. Asian. Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 12, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.P.; Tan, H.Y.; Wang, M.F. Tyrosinase inhibition constituents from the roots of Morus australis. Fitoterapia. 2012, 83, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Fan, M.; He, J.; Wu, X.D.; Peng, L.Y.; Su, J.; Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Kong, L.M.; Li, R.T.; Zhao, Q.S. New cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory compounds isolated from Morus alba L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, A.D.; Freyer, A.J.; Killmer, L.; Offen, P.; Taylor, P.B.; Votta, B.J.; Johnson, R.K. A new dimeric dihydrochalcone and a new prenylated flavone from the bud covers of Artocarpus altilis: potent inhibitors of cathepsin K. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.S.; Li, Z.L.; Yang, Y.P.; Xiao, W.L.; Li, X.L. New geranylated 2-Arylbenzofuran from Morus alba. Chin. Herb. Med. 2015, 7, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, G.Y.; Yang, C.X.; Ruan, Z.J.; Han, J.; Wang, G.C. Potent anti-MRSA activity and synergism with aminoglycosides by flavonoid derivatives from the root barks of Morus alba, a traditional chinese medicine. Med. Chem. Res. 2019, 28, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, T.; Fukai, T.; Sato, E.; Fukushima, K. The formation of moracenin-D from kuwanon-G. Heterocycles. 1981, 16, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hano, Y.; Yamanaka, J.; Momose, Y.; Nomura, T. Sorocenols C-F, four new isoprenylated phenols from the root bark of Sorocea bonplandii Baillon. Heterocycles. 1995, 41, 2811–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wu, J.C.; Li, H.L.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.G. Alkaloid and flavonoids from the seeds of Whitfordiodendron filipes. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2016, 52, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Q.; Fukai, T.; Sakagami, H. Cytotoxic flavonoids with isoprenoid groups from Morus m ongolica. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Luo, J.G.; Wan, C.X.; Zhou, Z.B.; Kong, L.Y. Geranylated 2-arylbenzofurans from Morus alba var. tatarica and their α-glucosidase and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitory activities. Fitoterapia. 2014, 92, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.J.; Lin, C.C.; Lu, T.M.; Li, J.H.; Chen, I.S.; Kuo, Y.H.; Ko, H.H. Chemical constituents derived from Artocarpus xanthocarpus as inhibitors of melanin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry. 2015, 117, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan Hiep, N.Y.; Kwon, J.Y.; Hong, S.G.; Kim, N.Y.; Guo, Y.Q.; Hwang, B.Y.; Mar, W.C.; Lee, D.H. Enantiomeric isoflavones with neuroprotective activities from the fruits of Maclura tricuspidata. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | δH (J in Hz) | δC | No. | δH (J in Hz) | δC |

| 2 | 156.7 | 1′′ | 3.62 d (7.2) | 23.6 | |

| 3 | 6.92 s | 102.3 | 2′′ | 5.40 t (7.2) | 123.6 |

| 3a | 124.2 | 3′′ | 135.9 | ||

| 4 | 7.32 d (8.4) | 119.1 | 4′′ | 1.89 s | 16.4 |

| 5 | 6.90 d (8.8) | 109.3 | 5′′ | 2.02 m | 36.7 |

| 6 | 156.4 | 6′′ | 1.60 m | 34.2 | |

| 7 | 114.4 | 7′′ | 3.90 t (6.8) | 76.1 | |

| 7a | 155.3 | 8′′ | 148.6 | ||

| 1′ | 133.8 | 9′′α | 4.79 s | 111.5 | |

| 2′ | 6.80* d (2.0) | 104.1 | 9′′β | 4.72 s | |

| 3′ | 160.0 | 10′′ | 1.62 s | 17.5 | |

| 4′ | 6.26 s | 103.6 | -OCH3 | 3.86 s | 57.0 |

| 5′ | 160.0 | ||||

| 6′ | 6.80* d (2.0) | 104.1 |

| Compound | Cell viability (%) | Compound | Cell viability (%) |

| 1 | 96.42 ± 4.57 | 19 | 95.67 ± 3.65 |

| 2 | 97.88 ± 2.26 | 20 | 93.72 ± 2.86 |

| 3 | 96.27 ± 2.37 | 21 | 98.96 ± 0.92 |

| 4 | 92.08 ± 4.25 | 22 | 96.86 ± 1.84 |

| 5 | 98.38 ± 0.58 | 23 | 83.99 ± 3.92 |

| 6 | 89.04 ± 3.06 | 24 | 94.57 ± 2.74 |

| 7 | 89.47 ± 2.04 | 25 | 88.99 ± 4.62 |

| 8 | 59.92 ± 2.16 | 26 | 95.22 ± 3.30 |

| 9 | 96.62 ± 0.54 | 27 | 92.97 ± 2.72 |

| 10 | 39.71 ± 3.27 | 28 | 102.55 ± 3.06 |

| 11 | 96.27 ± 4.14 | 29 | 98.20 ± 0.37 |

| 12 | 74.89 ± 1.58 | 30 | 46.84 ± 3.02 |

| 13 | 77.66 ± 6.40 | 31 | 98.51 ± 0.97 |

| 14 | 95.05 ± 2.78 | 32 | 83.55 ± 1.51 |

| 15 | 97.90 ± 1.74 | 33 | 88.55 ± 3.20 |

| 16 | 97.01 ± 1.83 | 34 | 98.26 ± 1.03 |

| 17 | 98.36 ± 1.65 | 35 | 90.74 ± 5.24 |

| 18 | 95.05 ± 2.30 | acontrol | 100.00 ± 1.31 |

| Compound | IC50 (%) |

| 5 | 10.24 ± 0.89 |

| 8 | 28.94 ± 0.72 |

| 10 | 6.08 ± 0.34 |

| 30 | 33.76 ± 2.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).