1. Introduction

Leprosy is a chronic disease which causes very complex problems around the world [

1]. Indonesia is the 3rd country with largest number of leprosy cases in the world, after India and Brazil [

2]. The prevalence of leprosy in Indonesia in 2021 was 0.45/10,000 with 89% of cases are multibacillary (MB) leprosy [

3]. Leprosy requires a long treatment with combination of antibiotics called multidrug therapy (MDT), which has changed the history of leprosy from a disaster to a curable disease [

4].

Adherence to treatment is one of the main keys to successful therapy of leprosy [

5]. Adherence to treatment is defined as patient behavior in accordance with the advice of health professionals [

6,

7]. Adherence with MDT in the treatment of leprosy will minimize the risk of relapse, prevent drug resistance, and minimize the risk of leprosy reactions and disabilities [

5,

8]. The leprosy program routinely uses treatment completion and withdrawal rates as indirect measure of medication adherence. Patients with paucibacillary (PB) leprosy must complete 6 doses of MDT in 6-9 months, whereas the multibacillary (MB) must complete 12 doses in a period of 12-18 months. Patients who do not reach this target are referred to as dropout (defaulter) [

5,

8]. Defaulter rate which represents the value of medication adherence in leprosy management strategy used so far, actually does not provide any information about treatment behavior and is of little use in preventing irregularity in MDT intake [

5].

To understand patient treatment behavior, factors that cause non-adherence to treatment, as well as for the effectiveness of efforts to increase medication adherence, it is necessary to use a tool that is accurate and practical in measuring medication adherence routinely [

9]. A self-reported questionnaire to assess medication adherence is an easy and inexpensive method, brief, comfortable to patients, valid, reliable, and can provide information about treatment behavior and beliefs. This method can also differentiate the type of non-adherence from different causative factors, thus requiring different interventions [

9,

10,

11]. With the important role of evaluating medication adherence and in effort to overcome the limitations of defaulter rate as parameter of medication adherence to MDT, a valid and reliable measuring tool is needed to assess medication adherence of leprosy patients in daily practice. This research was conducted to answer this need.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a mixed methods research design, consisted of qualitative and quantitative methods, which will be described as follows.

The Questionnaire Development Stage

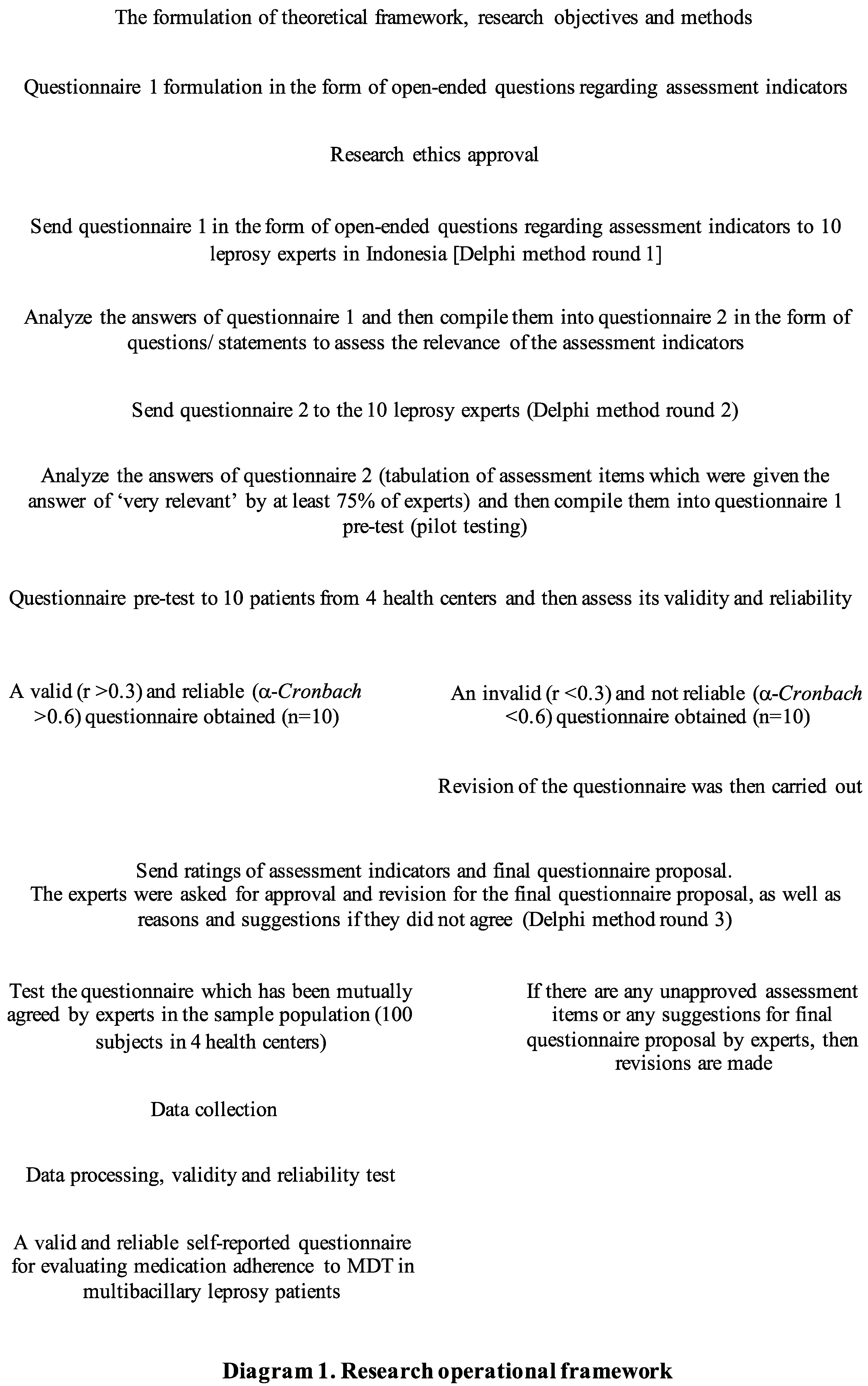

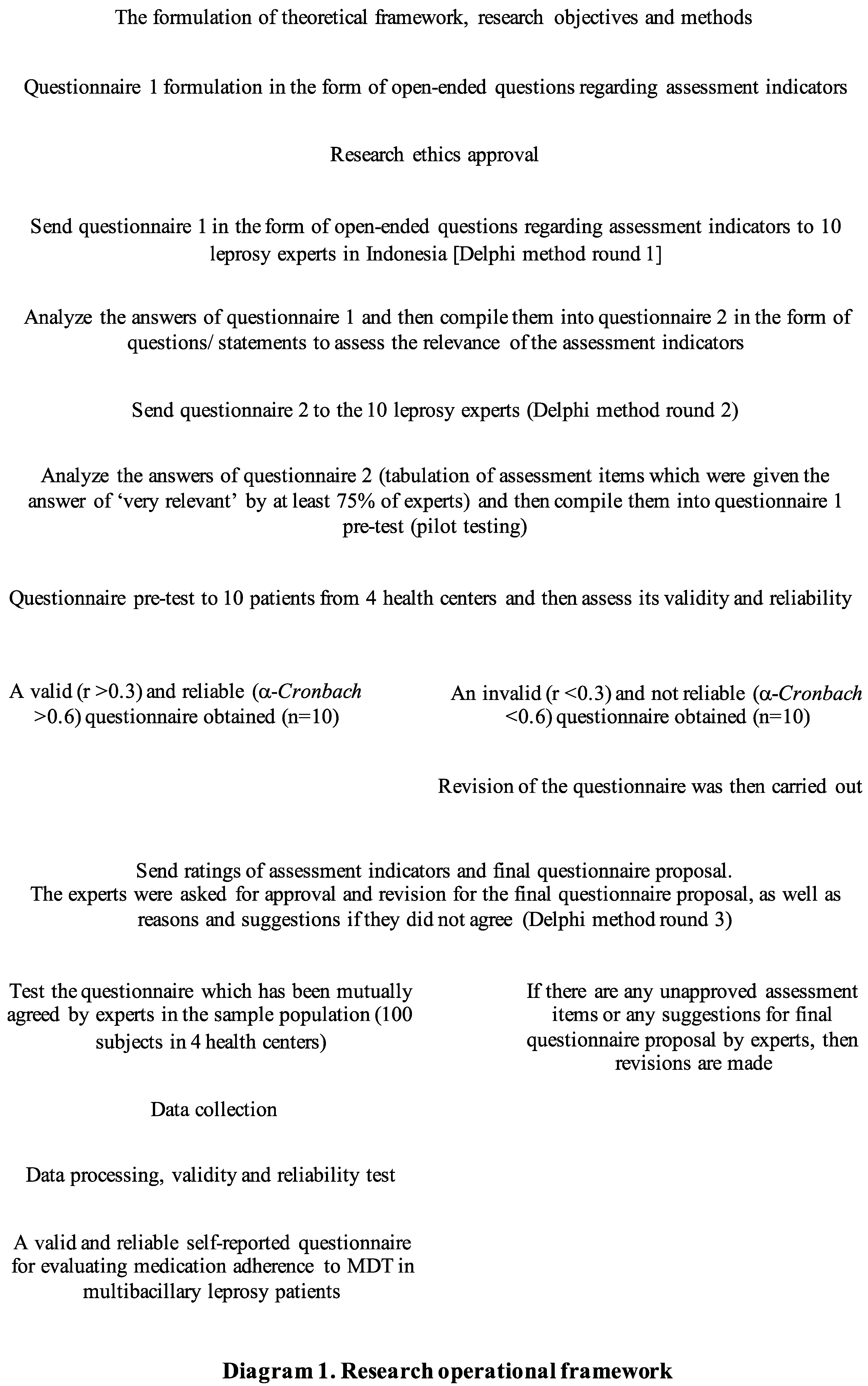

a) The questionnaire development stage based on experts panel using Delphi method

We applied the steps of developing instrument using Delphi method based on 10 leprosy experts i.e.: dermatologists who are also lecturers in the field of leprosy, doctors with minimum of 5 years of experience in MDT provider health centers, and the policy maker of leprosy in Indonesia. This stage was also carried out using a seven-step method based on Fowler and Cosenza (2009), Fowler (2014), and Amir (2015)[

12,

13,

14]. The complete step-by-step description of developing the questionnaire can be seen in the following

Diagram 1.

b) The questionnaire pre-test stage (pilot testing)

The questionnaire pilot testing was carried out on 10 leprosy patients across 4 health centers (Puskesmas Cakung Jakarta, Fatmawati Hospital Jakarta, dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo National Hospital Jakarta, and dr. Sitanala Leprosy Hospital Tangerang).

The Questionnaire Trial Stage

Cross sectional study design was used to collect data for all variables. The validity test of assessment items (internal validity) was done with Pearson moment products at SPSS 24.0, likewise with the external validity test. The inclusion criteria in this trial stage were: (1) male or female between 17-59 years old, (2) diagnosed with multibacillary type leprosy and were undergoing WHO MDT MB treatment regimen for at least 6 months or release from treatment (RFT) in the last 1 month, (3) were using Indonesian language, (4) could read, (5) had a record during treatment, in the form of medical records or MDT record, including treatment time, (6) brought the last current WHO MDT MB blister regimen which were still being consumed or had been consumed, and (7) willed to become study sample and signed the informed consent. While the exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with MDT drop out, (2) patients who experienced psychiatric disorders in the form of psychosis, anxiety, or depression, and (3) patients with cognitive impairments who were assessed using Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) questionnaire. The minimum sample size was obtained by calculating the correlation formula with the r value of 0.3, so it was determined as many as 100 subjects. The assessment item was said to be valid if the p value of the assessment item correlation to the total score <0.05 and the r value >0.3. Reliability test which measured was the reliability of internal consistency, with α-Cronbach >0.60.

3. Results

3.1. The Final Questionnaire

The final questionnaire (

Table 1) was the result of assessment items arrangement which had gone through several stages of revision and the third pilot testing with acceptable values of validity and reliability. Researchers used a Likert scale approach. Each assessment item contains 4 answer choices, therefore the researcher determines the lowest score = 1 for poor adherence answer choices, while the highest score = 4 for the good adherence answer choices. We determined a score of 29-36 as the category of good medication adherence, while a score of ≤ 28 as a category of poor medication adherence.

3.2. Characteristics of the Study Samples

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study samples (N = 100).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study samples (N = 100).

| Characteristics |

n (%) |

Means±SD

|

| Age (years) |

|

37.27 ± 13.45 |

| 17-30 years old |

34 (34.0) |

| 31-45 years old |

38 (38.0) |

| 46-59 years old |

28 (28.0) |

| Gender |

|

| Male |

69 (69.0) |

| Female |

31 (3.0) |

| Marital status |

|

| Single/ never married |

41 (41.0) |

| Married |

57 (57.0) |

| Divorced/ widowed |

2 (2.0) |

| Level of education |

|

|

| Never received school education |

4 (4.0) |

| Low education (kindergarten and elementary school) |

21 (21.0) |

| Middle education (junior high school and senior high school) |

67 (67.0) |

| High education (diploma, bachelor, magister, doctoral) |

8 (8.0) |

| Employment |

|

| Employed |

60 (60.0) |

| Unemployed |

40 (40.0) |

3.3. Validity and reliability test

The length of time to fill out the questionnaire had time range between 85 to 248 seconds. Internal validity relates to the accuracy degree of the study design with the results achieved[

15]. Meanwhile, external validity relates to the generalizability of the study results; whether or not an observed causal relationship can be generalized to and across different measures, persons, settings, and times [

16,

17]. Pill counts have been used by some investigators as adherence indicators, because they were easy to carry out although have some drawbacks [

18]. In this study, pill count was used as criteria to test the external validity of the newly developed questionnaire (

Table 3). Internal consistency reliability test of the ML-MAEQ gave an α-Cronbach value of 0.723.

Table 3.

Results of the internal/ items validity test and the external validity test of medication adherence questionnaire against pill count (N = 100).

Table 3.

Results of the internal/ items validity test and the external validity test of medication adherence questionnaire against pill count (N = 100).

| No. |

Assessment items |

Internal Validity |

External Validity |

| r |

Result |

r |

Result |

| 1 |

My family helped remind me to take MDT medication. |

0.687 |

Valid |

0.233 |

Invalid |

| 2 |

I take MDT every day according to the instructions on how to take medicines from the health worker. |

0.594 |

Valid |

0.590 |

Valid |

| 3 |

I showed the MDT drug blister that I had taken to the health worker. |

0.532 |

Valid |

0.304 |

Valid |

| 4 |

I went to a health facility where I got MDT according to the control schedule. |

0.483 |

Valid |

0.692 |

Valid |

| 5 |

I missed taking MDT medication because of experiencing drug side effects. |

0.583 |

Valid |

0.417 |

Valid |

| 6 |

The long term treatment (12-18 months) made it difficult for me to take MDT medication regularly. |

0.501 |

Valid |

0.096 |

Invalid |

| 7 |

I am sure I can recover by taking MDT medication regularly. |

0.600 |

Valid |

0.395 |

Valid |

| 8 |

I understand the transmission, reactions, and complications of leprosy, so I take MDT medication regularly. |

0.615 |

Valid |

0.324 |

Valid |

| 9 |

Family and people around me help support a comfortable situation, so I take MDT medication regularly. |

0.564 |

Valid |

0.181 |

Invalid |

3.4. Sensitivity and Specificity Test

Although there has been no gold standard instrument used in measuring MDT adherence until now, the pill count method is considered to be quite favourable and it has been recommended to be used periodically to measure medication adherence [

5]. Therefore, in this study the sensitivity and specificity assessment of the new instrument was compared to the pill count (

Table 4). The analysis results of ML-MAEQ diagnostic test was found to have a sensitivity value of 88.46%, specificity of 78.37%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 58.97%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 95.08%.

Table 4.

Results of the medication adherence questionnaire score and pill count (N = 100).

Table 4.

Results of the medication adherence questionnaire score and pill count (N = 100).

| |

|

Pill count |

|

| Result |

Poor adherence |

Good adherence |

Total |

|

| |

Poor adherence |

23 |

16 |

39 |

|

| Questionnaire |

Good adherence |

3 |

58 |

61 |

|

| |

Total |

26 |

74 |

100 |

|

4. Discussion

In selecting and using the medication adherence questionnaire, we need to consider of what the scale actually measures and how well it has been validated [

10]. As every disease has different characters from one another, no questionnaire is a gold standard for medication adherence measurement [

19,

20]. According to Čulig and Leppée, Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) is the nearest to gold standard test tool, however the internal consistency reliability is not better than some other scales, and it is only capable to identify barriers of medication adherence [

10,

20,

21]. Some of the preexisting medication adherence questionnaires were also likely specific for only certain diseases [

10,

20,

21]. The eight-items Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) has better validity and reliability than MAQ, but it has good internal consistency and reproducibility only in a few types of diseases [

22].

Validity and reliability are the two most important and fundamental features in the evaluation of any instrument [

23]. No questionnaire has been tested for its validity and reliability in assessing adherence to MDT. Our study showed that the newly developed instrument or so called the Multibacillary Leprosy Medication Adherence Evaluation Questionnaire (ML-MAEQ) provided good practicality, validity and reliability in Indonesian patients. The causal relationship of one concept to another can be discussed in terms of validity. Internal validity refers to the strength of relationship of a concept to another internal to the research question under study [

24]. Internal validity is an essential thing which must be fulfilled if the researchers want the results to be meaningful. It also takes precedence over external validity test, because unbiased results must be reached first before generalization results [

25]. From the results of internal validity test, the correlation between each assessment item with the total score was good because all statements had a correlation coefficient >0.3. Therefore, it can be concluded that each assessment item in ML-MAEQ is worthy of use and accurately assesses what should be assessed.

Internal consistency was used in the questionnaire reliability test. Internal consistency with an α-Cronbach value of 0.6 is considered sufficient for a newly developed scale. The ML-MAEQ gave an α-Cronbach value of 0.723 which indicates this new instrument has a relatively high to good internal consistency [

26]. Because there were still no questionnaire been tested for its reliability in assessing medication adherence to MDT, so ML-MAEQ has not comparable to other questionnaires.

External validity is one of the most difficult types of validity to achieve. Many studies face problems when it comes to measure the external validity, to prove the study results can be generalized to a wider population. Most of these studies yield in high internal validity but low external validity[

25]. Experts argue that the external validity test results can be invalid if the sample study does not represent the target population [

25]. Although this study has been carried out in a multicenter manner, most samples came from health centers which are referral hospitals, which had many experts in dermatology, except for the first line health center Puskesmas Cakung. These health workers were considered to have more skills in evaluating, managing, and providing education about leprosy and MDT. Therefore, the sample obtained in this study was still insufficient to represent the target population, especially those who seek treatment at various first line health centers. Researchers found that although items number 1, 6, and 9 have a weak correlation coefficient, all have positive values. This means that all variables move in the same direction (parallel or linear) and measure the same manifestations, nothing contradicts. If the observed pattern between two variables is linear, then the correlation coefficient indicates a reliable measure [

27]. In order to obtain good validity of an instrument, a large and representative sample size is generally required [

28].

Sensitivity shows the probability that the instrument correctly identifies patients who actually suffer from certain disease, while specificity shows how often the instrument is negative in patients who do not have certain disease [

29]. ML-MAEQ is worth to be used in screening or evaluating medication adherence to MDT for its good sensitivity and specificity. The PPV indicates how much the result is truly positive when it is found to be positive, while NPV assesses how much an examination result is truly negative when it is found to be negative. These two values have a more profound significance clinical practice for interpretation of results than the sensitivity and specificity [

30].

This study had limitations. Although this instrument can be generalized to all multibacillary leprosy patients who got MDT, but some factors including sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of this study only described the conditions in Jakarta and Tangerang with patients mainly came from a referral health centres. The same results may not be obtained from multibacillary leprosy patients in other areas, other cultures, private clinics, or in the first line health centres with more subjects proportion than in this study.

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which produced a valid and reliable instrument for evaluating MDT medication adherence. Further research will determine whether this instrument is valid in other settings, cultures, and borderline type leprosy patients. In addition, to obtain better external validity results, further research should be involving a larger and more varied subject samples (multicentres).

Author Contributions

LSS, SLM and H contributed to the study conception and design. SLM, KB, H and EM contributed to data analysis and supervision. Data collection, analysis, interpretation, and the first draft of the manuscript were predominantly performed by LSS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Standing Committee for Research Ethics Assessment of Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia, with approval letter number 1089/UN2.F1/ETIK/2018 (October 22nd, 2018) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions eg privacy or ethical.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank all of our Indonesian leprosy experts who were involved in this study i.e: Prof. Dr. dr. Cita Rosita S.P., SpKK(K); Dr. dr. Raden Pamudji, SpKK; Dr. dr. Sri Vitayani Muchtar, SpKK; dr. Hendra Gunawan, SpKK(K), PhD; dr. Emmy Soedarmi S. Daili, SpKK(K); dr. Melani Marissa, SpKK; dr. Linda Astari, SpKK; and dr. Tiffany Tiara Pakasi, MA. The authors are grateful to all respondents for their participation in this study. We also thank Mrs. Sali Rahadi Asih, S.Psi., M.Psi, MGPCC who has opened our horizons regarding the development of behavioral instruments. We thank dr. Stephanie Lukita for her help in data collection and management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Leprosy [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leprosy.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy strategy 2016-2020: Accelerating towards a leprosy-free world. [Internet]. Vol. 1; WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: New Delhi, India, 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/205149/1/B5233.pdf?ua=1.

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Profil Kesehatan Indonesia 2021; Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022; pp.188-192.

- World Health Organization. Multidrug therapy against leprosy: Development and implementation over the past 25 years 2004 [cited 2020 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241591765.

- Weiand D, Thoulass J, Smith WCS. Assessing and improving adherence with multidrug therapy. Lepr Rev. 2012;83:282–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23356029.

- De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2(4):323. [CrossRef]

- Barofsky I. Compliance, adherence and the therapeutic alliance: Steps in the development of self-care. Soc Sci Med Part A Med Psychol Med. 1978;12(C):369–376. [CrossRef]

- Pai V, Rao R, Halwai V. Chemotherapy: Development and evolution of WHO-MDT and newer treatment regimens. In: IAL Textbook of Leprosy, 2nd ed.; Kumar B, Kar HK, editors.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publisher Ltd: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp.448–464.

- Garfield S, Clifford S, Eliasson L, Barber N, Willson A. Suitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: A systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):149. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/149.

- Nguyen T, Caze A La, Cottrell N. What are validated self-report adherence scales really measuring? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;427–445. [CrossRef]

- Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, Elliott R. Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. Rep Natl Co-ord Cent NHS Serv Deliv Organ R D. 2005; pp.1–331.

- Fowler FJ, Cosenza C. The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research. 2nd ed. Bickman L, Rog DJ, editors.; SAGE Publications Inc.: California, 2009; pp.375–412.

- Fowler FJ. Evaluating survry questions and instruments. In: Survey Research Methods, 5th ed.; Fowler FJ, editor.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Boston, 2014; pp.99–109.

- Amir MT. Merancang kuesioner: Konsep dan panduan untuk penelitian sikap, kepribadian dan perilaku, 1st ed.; Kencana: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015; pp.1-233.

- Bolarinwa OA. Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2015;22:195–201. [CrossRef]

- Bracht GH, Glass G V. The external validity of experiments. Am Educ Res J. 1968;5(4):437–74. [CrossRef]

- Calder BJ, Phillips LW, Tybout AM. The concept of external validity. J Consum Res. 1982;9(3):240. [CrossRef]

- Vadher A, Lalljee M. Patient treatment compliance in leprosy: A critical review. Int J Lepr. 1992;60(4):587–607.

- Lavsa SM, Holzworth A, Ansani NT. Selection of a validated scale for measuring medication adherence. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2011;51(1):90–4. [CrossRef]

- Čulig J, Leppée M. From Morisky to Hill-Bone ; self-reports scales for measuring adherence to medication. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:55–62.

- Lam WY, Fresco P. Medication adherence measures: An overview. Biomed Res Int; 2015. [cited 2019 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2015/217047/.

- Jae Moon S, Lee W-Y, Seub Hwang J, Pyo Hong Y, Morisky DE. Accuracy of a screening tool for medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8. 2017;81:1–18. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5667769/pdf/pone.0187139.pdf.

- Mohajan HK. Two criteria for good measurements in research: Validity and reliability. Ann Spiru Haret Univ Econ Ser. 2017;17(3):58–82. [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald MP. Validity, data sources. In: Encyclopedia of social measurement; Kempf-Leonard K, editor.; Elsevier Inc.: California, 2005; pp.939–948.

- Taylor S, Asmundson GJG. Internal and external validity in clinical research. In: Handbook of research methods in abnormal and clinical psychology; McKay DR, editor.; Sage Publications Inc., 2008; pp.23–34.

- Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48(6):1273–1296. [CrossRef]

- Ratner B. The correlation coefficient: Definition [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.dmstat1.com/res/TheCorrelationCoefficientDefined.html.

- Kaplan RM, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. Commentary big data and large sample size : A cautionary note on the potential for bias. Clin Transl Sci. 2014;7(4):342–346. [CrossRef]

- Lalkhen AG, McCluskey A. Clinical tests: Sensitivity and specificity. Contin Educ Anaesthesia, Crit Care Pain. 2008;8(6):221–223. [CrossRef]

- Pusponegoro HD, Wirya IGNW, Pudjiadi AH, Bisanto J, Zulkarnain SZ. Uji diagnostik. In: Dasar-dasar metodologi penelitian klinis, 5th ed.; Sastroasmoro S, Ismael S, editors.; CV Sagung Seto: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014; pp.219–244.

Table 1.

Final questionnaire [Multibacillary Leprosy Medication Adherence Evaluation Questionnaire (ML-MAEQ)].

Table 1.

Final questionnaire [Multibacillary Leprosy Medication Adherence Evaluation Questionnaire (ML-MAEQ)].

| No. |

Assessment Items |

Never |

Sometimes |

Often |

Always |

| 1 |

My family helped remind me to take MDT medication. |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

I take MDT every day according to the instructions on how to take medicines from the health worker. |

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

I showed the MDT drug blister that I had taken to the health worker. |

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

I went to a health facility where I got MDT according to the control schedule. |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

I missed taking MDT medicationbecause of experiencing drug side effects. |

|

|

|

|

| No. |

Assessment Items |

Strongly disagree |

Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly agree |

| 6 |

The long term treatment (12-18 months) made it difficult for me to take MDT medication regularly. |

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

I am sure I can recover by taking MDT medication regularly. |

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

I understand the transmission, reactions, and complications of leprosy, so I take MDT medication regularly. |

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

Family and people around me help support a comfortable situation, so I take MDT medication regularly. |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).