Submitted:

14 November 2023

Posted:

15 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dengue Virus and Cells

2.2. Original pE1D2 and pcTPANS1 Plasmids

2.3. Construction of the Codon Optimized pEotmD2 and pNS1otmD2 Plasmids

2.4. DNA Vaccine Purification

2.5. Cell Transfection and Immunofluorescence Assay

2.6. Cell Transfection and Flow Cytometry

2.7. Mice Immunization and Challenge with DENV2

2.8. Detection of Antibodies Against the E and NS1 Proteins

2.9. Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT50)

2.10. Interferon Gamma ELISPOT Assay

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Codon Optimization on E and NS1 Protein Expression in Mouse and Human Cells

3.2. The Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses Generated by Optimized or Original DNA vaccines

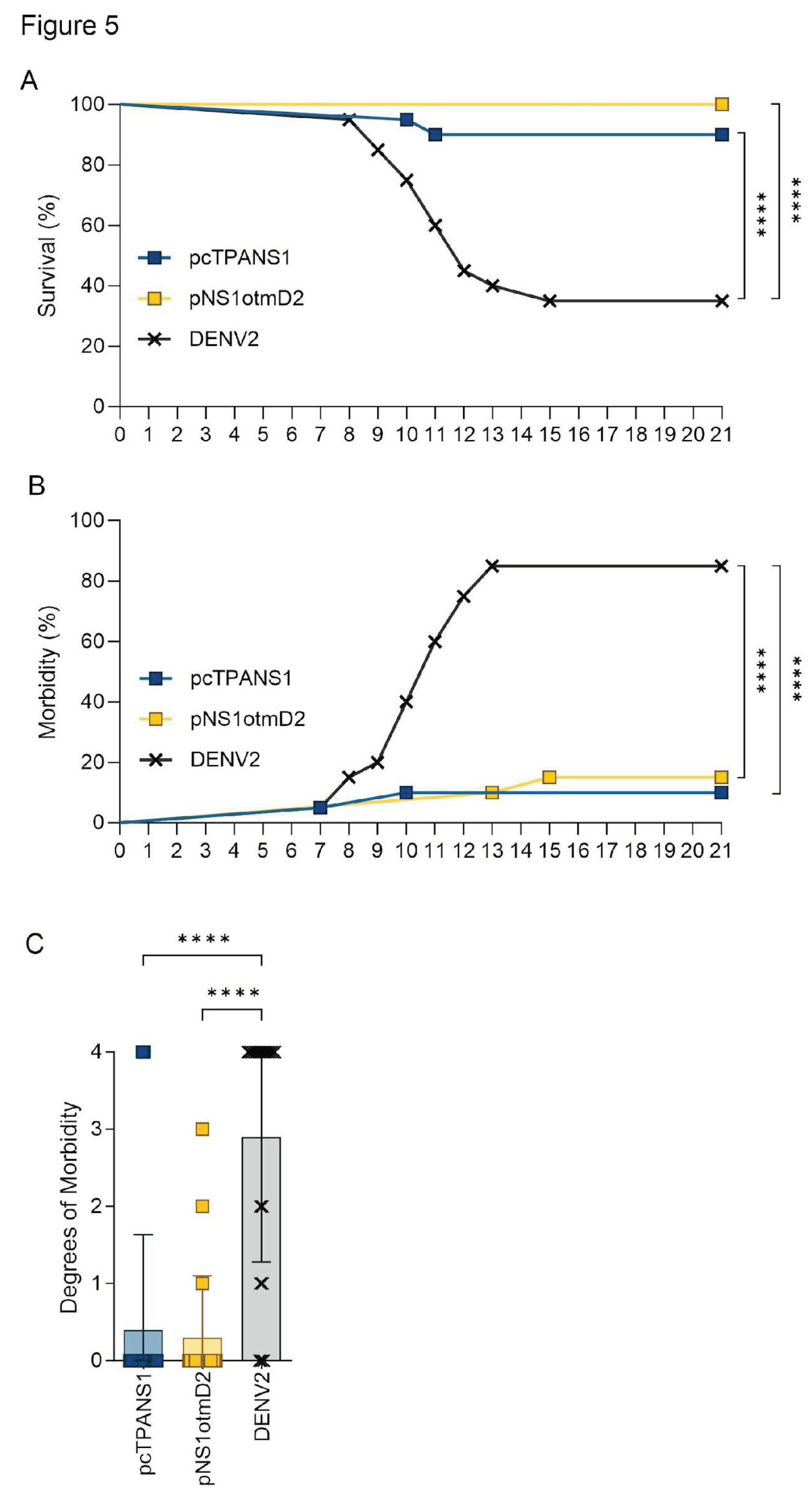

3.3. Codon Optimization Failed to Improve the Efficacy the NS1- or E-Based DNA Vaccines

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brady, O.J.; Gething, P.W.; Bhatt, S.; Messina, J.P.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Moyes, C.L.; Farlow, A.W.; Scott, T.W.; Hay, S.I. Refining the Global Spatial Limits of Dengue Virus Transmission by Evidence-Based Consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012, 6, e1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030: Overview; World Health Organization, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-001879-2.

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Ooi, E.-E.; Horstick, O.; Wills, B. Dengue. The Lancet 2019, 393, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte-Sengupta, S.; Sirohi, D.; Kuhn, R.J. Coupling of Replication and Assembly in Flaviviruses. Current Opinion in Virology 2014, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayal, A.; Kabra, S.K.; Lodha, R. Management of Dengue: An Updated Review. Indian J Pediatr 2023, 90, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman, M.G.; Alvarez, M.; Halstead, S.B. Secondary Infection as a Risk Factor for Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever/Dengue Shock Syndrome: An Historical Perspective and Role of Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Infection. Arch Virol 2013, 158, 1445–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.B.; Gibbons, R.V.; Cummings, D.A.T.; Nisalak, A.; Green, S.; Libraty, D.H.; Jarman, R.G.; Srikiatkhachorn, A.; Mammen, M.P.; Darunee, B.; et al. A Shorter Time Interval Between First and Second Dengue Infections Is Associated With Protection From Clinical Illness in a School-Based Cohort in Thailand. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014, 209, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Gresh, L.; Halloran, M.E.; Mercado, J.C.; Kuan, G.; Gordon, A.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Severe Dengue Disease in Humans. Science 2017, 358, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilder-Smith, A. Dengue Vaccine Development by the Year 2020: Challenges and Prospects. Current Opinion in Virology 2020, 43, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Wang, S.-F.; Wang, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-H. Dengue Vaccine: An Update. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2021, 19, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capeding, M.R.; Tran, N.H.; Hadinegoro, S.R.S.; Ismail, H.I.H.M.; Chotpitayasunondh, T.; Chua, M.N.; Luong, C.Q.; Rusmil, K.; Wirawan, D.N.; Nallusamy, R.; et al. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of a Novel Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine in Healthy Children in Asia: A Phase 3, Randomised, Observer-Masked, Placebo-Controlled Trial. The Lancet 2014, 384, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, L.; Dayan, G.H.; Arredondo-García, J.L.; Rivera, D.M.; Cunha, R.; Deseda, C.; Reynales, H.; Costa, M.S.; Morales-Ramírez, J.O.; Carrasquilla, G.; et al. Efficacy of a Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine in Children in Latin America. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dengue Vaccines: WHO Position Paper – September 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/who-wer9335-457-476 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Halstead, S.B. Safety Issues from a Phase 3 Clinical Trial of a Live-Attenuated Chimeric Yellow Fever Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2018, 14, 2158–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.-H.; Butrapet, S.; Tsuchiya, K.R.; Bhamarapravati, N.; Gubler, D.J.; Kinney, R.M. Dengue 2 PDK-53 Virus as a Chimeric Carrier for Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine Development. J Virol 2003, 77, 11436–11447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, L.; Biswal, S.; Sáez-Llorens, X.; Reynales, H.; López-Medina, E.; Borja-Tabora, C.; Bravo, L.; Sirivichayakul, C.; Kosalaraksa, P.; Martinez Vargas, L.; et al. Three-Year Efficacy and Safety of Takeda’s Dengue Vaccine Candidate (TAK-003). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 75, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, C. First COVID-19 DNA Vaccine Approved, Others in Hot Pursuit. Nat Biotechnol 2021, 39, 1479–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghban, R.; Ghasemian, A.; Mahmoodi, S. Nucleic Acid-Based Vaccine Platforms against the Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19). Arch Microbiol 2023, 205, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, T.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, G.; Saxena, S.K. Tracking the COVID-19 Vaccines: The Global Landscape. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2023, 19, 2191577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobernik, D.; Bros, M. DNA Vaccines—How Far From Clinical Use? IJMS 2018, 19, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Saade, F.; Petrovsky, N. The Future of Human DNA Vaccines. Journal of Biotechnology 2012, 162, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhuang, X.; Shang, C.; Sun, S.; Han, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of a DNA Vaccine Inducing Optimal Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 S Gene in hACE2 Mice. Arch Virol 2022, 167, 2519–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, R.J.; Zhang, W.; Rossmann, M.G.; Pletnev, S.V.; Lenches, E.; Jones, C.T.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Strauss, E.G.; Baker, T.S.; Strauss, J.H. Structure of Dengue Virus: Implications for Flavivirus Organization, Maturation, and Fusion. 2014.

- Stiasny, K.; Kössl, C.; Lepault, J.; Rey, F.A.; Heinz, F.X. Characterization of a Structural Intermediate of Flavivirus Membrane Fusion. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Wu, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, S.; Cheng, A. The Key Amino Acids of E Protein Involved in Early Flavivirus Infection: Viral Entry. Virol J 2021, 18, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modis, Y.; Ogata, S.; Clements, D.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of the Dengue Virus Envelope Protein after Membrane Fusion. Nature 2004, 427, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modis, Y.; Ogata, S.; Clements, D.; Harrison, S.C. Variable Surface Epitopes in the Crystal Structure of Dengue Virus Type 3 Envelope Glycoprotein. J Virol 2005, 79, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-Y.; Lin, H.-E.; Wang, W.-K. Complexity of Human Antibody Response to Dengue Virus: Implication for Vaccine Development. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, A.L. Immunity to Dengue Virus: A Tale of Original Antigenic Sin and Tropical Cytokine Storms. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivino, L. Understanding the Human T Cell Response to Dengue Virus. In Dengue and Zika: Control and Antiviral Treatment Strategies; Hilgenfeld, R., Vasudevan, S.G., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; Vol. 1062, pp. 241–250. ISBN 978-981-10-8726-4. [Google Scholar]

- Flamand, M.; Megret, F.; Mathieu, M.; Lepault, J.; Rey, F.A.; Deubel, V. Dengue Virus Type 1 Nonstructural Glycoprotein NS1 Is Secreted from Mammalian Cells as a Soluble Hexamer in a Glycosylation-Dependent Fashion. J Virol 1999, 73, 6104–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, P.R.; Hilditch, P.A.; Bletchly, C.; Halloran, W. An Antigen Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Reveals High Levels of the Dengue Virus Protein NS1 in the Sera of Infected Patients. J Clin Microbiol 2000, 38, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avirutnan, P.; Zhang, L.; Punyadee, N.; Manuyakorn, A.; Puttikhunt, C.; Kasinrerk, W.; Malasit, P.; Atkinson, J.P.; Diamond, M.S. Secreted NS1 of Dengue Virus Attaches to the Surface of Cells via Interactions with Heparan Sulfate and Chondroitin Sulfate E. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3, e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.M.; Azevedo, A.S.; Paes, M.V.; Sarges, F.S.; Freire, M.S.; Alves, A.M.B. DNA Vaccines against Dengue Virus Based on the Ns1 Gene: The Influence of Different Signal Sequences on the Protein Expression and Its Correlation to the Immune Response Elicited in Mice. Virology 2007, 358, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-R.; Lai, Y.-C.; Yeh, T.-M. Dengue Virus Non-Structural Protein 1: A Pathogenic Factor, Therapeutic Target, and Vaccine Candidate. J Biomed Sci 2018, 25, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasner, D.R.; Puerta-Guardo, H.; Beatty, P.R.; Harris, E. The Good, the Bad, and the Shocking: The Multiple Roles of Dengue Virus Nonstructural Protein 1 in Protection and Pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 227–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayathilaka, D.; Gomes, L.; Jeewandara, C.; Jayarathna, G.S.B.; Herath, D.; Perera, P.A.; Fernando, S.; Wijewickrama, A.; Hardman, C.S.; Ogg, G.S.; et al. Role of NS1 Antibodies in the Pathogenesis of Acute Secondary Dengue Infection. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpio, K.L.; Barrett, A.D.T. Flavivirus NS1 and Its Potential in Vaccine Development. Vaccines 2021, 9, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, J.J.; Brandriss, M.W.; Walsh, E.E. Protection of Mice against Dengue 2 Virus Encephalitis by Immunization with the Dengue 2 Virus Non-Structural Glycoprotein NS1. J Gen Virol 1987, 68 Pt 3, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.M.; Paes, M.V.; Barreto, D.F.; Pinhão, A.T.; Barth, O.M.; Queiroz, J.L.S.; Armôa, G.R.G.; Freire, M.S.; Alves, A.M.B. Protection against Dengue Type 2 Virus Induced in Mice Immunized with a DNA Plasmid Encoding the Non-Structural 1 (NS1) Gene Fused to the Tissue Plasminogen Activator Signal Sequence. Vaccine 2006, 24, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, J.H.; Diniz, M.O.; Cariri, F.A.M.O.; Rodrigues, J.F.; Bizerra, R.S.P.; Gonçalves, A.J.S.; De Barcelos Alves, A.M.; De Souza Ferreira, L.C. Protective Immunity to DENV2 after Immunization with a Recombinant NS1 Protein Using a Genetically Detoxified Heat-Labile Toxin as an Adjuvant. Vaccine 2012, 30, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.J.S.; Oliveira, E.R.A.; Costa, S.M.; Paes, M.V.; Silva, J.F.A.; Azevedo, A.S.; Mantuano-Barradas, M.; Nogueira, A.C.M.A.; Almeida, C.J.; Alves, A.M.B. Cooperation between CD4+ T Cells and Humoral Immunity Is Critical for Protection against Dengue Using a DNA Vaccine Based on the NS1 Antigen. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0004277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, P.R.; Puerta-Guardo, H.; Killingbeck, S.S.; Glasner, D.R.; Hopkins, K.; Harris, E. Dengue Virus NS1 Triggers Endothelial Permeability and Vascular Leak That Is Prevented by NS1 Vaccination. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.S.; Yamamura, A.M.Y.; Freire, M.S.; Trindade, G.F.; Bonaldo, M.; Galler, R.; Alves, A.M.B. DNA Vaccines against Dengue Virus Type 2 Based on Truncate Envelope Protein or Its Domain III. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caufour, P.S.; Motta, M.C.A.; Yamamura, A.M.Y.; Vazquez, S.; Ferreira, I.I.; Jabor, A.V.; Bonaldo, M.C.; Freire, M.S.; Galler, R. Construction, Characterization and Immunogenicity of Recombinant Yellow Fever 17D-Dengue Type 2 Viruses. Virus Research 2001, 79, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.; Wang, Q.; Dai, Z.; Calcedo, R.; Sun, X.; Li, G.; Wilson, J.M. Adenovirus-Based Vaccines Generate Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes to Epitopes of NS1 from Dengue Virus That Are Present in All Major Serotypes. Human Gene Therapy 2008, 19, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, A.L.; Kurane, I.; Ennis, F.A. Multiple Specificities in the Murine CD4ϩ and CD8ϩ T-Cell Response to Dengue Virus. J. VIROL. 1996, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A.M.B.; Costa, S.M.; Pinto, P.B.A. Dengue Virus and Vaccines: How Can DNA Immunization Contribute to This Challenge? Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3, 640964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, P.B.A.; Assis, M.L.; Vallochi, A.L.; Pacheco, A.R.; Lima, L.M.; Quaresma, K.R.L.; Pereira, B.A.S.; Costa, S.M.; Alves, A.M.B. T Cell Responses Induced by DNA Vaccines Based on the DENV2 E and NS1 Proteins in Mice: Importance in Protection and Immunodominant Epitope Identification. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, M.; Villalobos, A.; Gustafsson, C.; Minshull, J. You’re One in a Googol: Optimizing Genes for Protein Expression. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, G.; Coller, J. Codon Optimality, Bias and Usage in Translation and mRNA Decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathy, S.T.; Udayasuriyan, V.; Bhadana, V. Codon Usage Bias. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narum, D.L.; Kumar, S.; Rogers, W.O.; Fuhrmann, S.R.; Liang, H.; Oakley, M.; Taye, A.; Sim, B.K.L.; Hoffman, S.L. Codon Optimization of Gene Fragments Encoding Plasmodium Falciparum Merzoite Proteins Enhances DNA Vaccine Protein Expression and Immunogenicity in Mice. Infect Immun 2001, 69, 7250–7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.-J.; Ko, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, E.-G.; Cho, S.-N.; Kang, C.-Y. Optimization of Codon Usage Enhances the Immunogenicity of a DNA Vaccine Encoding Mycobacterial Antigen Ag85B. Infect Immun 2005, 73, 5666–5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-T.; Tsai, Y.-C.; He, L.; Calizo, R.; Chou, H.-H.; Chang, T.-C.; Soong, Y.-K.; Hung, C.-F.; Lai, C.-H. A DNA Vaccine Encoding a Codon-Optimized Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E6 Gene Enhances CTL Response and Anti-Tumor Activity. J Biomed Sci 2006, 13, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lu, F.; Dai, Y.; Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Lu, S.; Wang, S. Synergistic Enhancement of Immunogenicity and Protection in Mice against Schistosoma Japonicum with Codon Optimization and Electroporation Delivery of SjTPI DNA Vaccines. Vaccine 2010, 28, 5347–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Gao, L.; Gao, H.; Qi, X.; Gao, Y.; Qin, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Codon Optimization and Woodchuck Hepatitis Virus Posttranscriptional Regulatory Element Enhance the Immune Responses of DNA Vaccines against Infectious Bursal Disease Virus in Chickens. Virus Research 2013, 175, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latanova, A.A.; Petkov, S.; Kilpelainen, A.; Jansons, J.; Latyshev, O.E.; Kuzmenko, Y.V.; Hinkula, J.; Abakumov, M.A.; Valuev-Elliston, V.T.; Gomelsky, M.; et al. Codon Optimization and Improved Delivery/Immunization Regimen Enhance the Immune Response against Wild-Type and Drug-Resistant HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase, Preserving Its Th2-Polarity. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Ferrall, L.; Gaillard, S.; Wang, C.; Chi, W.-Y.; Huang, C.-H.; Roden, R.B.S.; Wu, T.-C.; Chang, Y.-N.; Hung, C.-F. Development of DNA Vaccine Targeting E6 and E7 Proteins of Human Papillomavirus 16 (HPV16) and HPV18 for Immunotherapy in Combination with Recombinant Vaccinia Boost and PD-1 Antibody. mBio 2021, 12, e03224-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, A.S.; Gonçalves, A.J.S.; Archer, M.; Freire, M.S.; Galler, R.; Alves, A.M.B. The Synergistic Effect of Combined Immunization with a DNA Vaccine and Chimeric Yellow Fever/Dengue Virus Leads to Strong Protection against Dengue. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.B.A.; Barros, T.A.C.; Lima, L.M.; Pacheco, A.R.; Assis, M.L.; Pereira, B.A.S.; Gonçalves, A.J.S.; Azevedo, A.S.; Neves-Ferreira, A.G.C.; Costa, S.M.; et al. Combination of E- and NS1-Derived DNA Vaccines: The Immune Response and Protection Elicited in Mice against DENV2. Viruses 2022, 14, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, V.P.; Chappell, S.A. A Critical Analysis of Codon Optimization in Human Therapeutics. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2014, 20, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroubek, J.; Krishnan, Y.; McDonald, T.V. Sequence and Structure-Specific Elements of HERG mRNA Determine Channel Synthesis and Trafficking Efficiency. FASEB J 2013, 27, 3039–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertalovitz, A.C.; Badhey, M.L.O.; McDonald, T.V. Synonymous Nucleotide Modification of the KCNH2 Gene Affects Both mRNA Characteristics and Translation of the Encoded hERG Ion Channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 12120–12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agashe, D.; Martinez-Gomez, N.C.; Drummond, D.A.; Marx, C.J. Good Codons, Bad Transcript: Large Reductions in Gene Expression and Fitness Arising from Synonymous Mutations in a Key Enzyme. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-J.; Sauna, Z.E.; Kimchi-Sarfaty, C.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Gottesman, M.M.; Nussinov, R. Synonymous Mutations and Ribosome Stalling Can Lead to Altered Folding Pathways and Distinct Minima. Journal of Molecular Biology 2008, 383, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, P.S.; Siller, E.; Anderson, J.F.; Barral, J.M. Silent Substitutions Predictably Alter Translation Elongation Rates and Protein Folding Efficiencies. Journal of Molecular Biology 2012, 422, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, I.M.; Chaney, J.L.; Clark, P.L. Expanding Anfinsen’s Principle: Contributions of Synonymous Codon Selection to Rational Protein Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 858–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, M.; Cai, G.; He, M. Genetic Code-Guided Protein Synthesis and Folding in Escherichia Coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 30855–30861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.-H.; Dang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhao, F.; Sachs, M.S.; Liu, Y. Codon Usage Influences the Local Rate of Translation Elongation to Regulate Co-Translational Protein Folding. Molecular Cell 2015, 59, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döşkaya, M.; Kalantari-Dehaghi, M.; Walsh, C.M.; Hiszczyńska-Sawicka, E.; Davies, D.H.; Felgner, P.L.; Larsen, L.S.Z.; Lathrop, R.H.; Hatfield, G.W.; Schulz, J.R.; et al. GRA1 Protein Vaccine Confers Better Immune Response Compared to Codon-Optimized GRA1 DNA Vaccine. Vaccine 2007, 25, 1824–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobaño, C.; Sedegah, M.; Rogers, W.O.; Kumar, S.; Zheng, H.; Hoffman, S.L.; Doolan, D.L. Plasmodium: Mammalian Codon Optimization of Malaria Plasmid DNA Vaccines Enhances Antibody Responses but Not T Cell Responses nor Protective Immunity. Experimental Parasitology 2009, 122, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani Fooladi, A.A.; Bagherpour, G.; Khoramabadi, N.; Fallah Mehrabadi, J.; Mahdavi, M.; Halabian, R.; Amin, M.; Izadi Mobarakeh, J.; Einollahi, B. Cellular Immunity Survey against Urinary Tract Infection Using pVAX/ Fim H Cassette with Mammalian and Wild Type Codon Usage as a DNA Vaccine. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2014, 3, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).