1. Introduction

With increasing life expectancy, osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (VCF) represent a significant health concern, particularly in aging population, especially postmenopausal women [

1,

2]. The demographics and prevalence of these fractures highlight the scope of the problem [

3]. Approximately, 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men over the age of 50 will experience an osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime, and vertebral compression fractures account for a substantial proportion of these incidents [

3]. Moreover, these fractures are frequently underdiagnosed, leading to undertreatment and prolonged suffering [

4,

5].

The clinical consequences of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures are multifaceted. Patients who experience these fractures often suffer from acute or subacute back pain. This pain can be severe, debilitating and persistent, making it a primary reason for seeking medical attention [

6]. In addition to pain, these fractures result in a loss of vertebral height and can lead to kyphosis or a forward curvature of the spine [

7]. This altered spinal alignment can reduce lung capacity, leading to respiratory compromise, and impair mobility, further diminishing the patient's quality of life. Reduced physical activity and an inability to perform daily tasks add to the burden independently [

8].

Diagnosing and managing osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures presents a unique set of challenges. These fractures are frequently asymptomatic until pain becomes pronounced, making early diagnosis a complex task. Often, they are discovered incidentally on radiological studies performed for other reasons [

6]. Additionally, conventional X-rays may lose sensitivity, and more advanced imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT), are necessary for accurate diagnosis [

6]. However, the lack of awareness and inconsistent screening practices contribute to underdiagnosis.

The challenges in managing these fractures revolve around a multifaceted approach that includes pain management, restoration of vertebral height, and prevention of further fractures [

9]. Medical treatments, such as analgesics and physical therapy, may offer relief from pain, but they do not address the underlying structural problem [

10]. The development of pharmaceutical interventions that can improve bone density and quality is a notable advancement [

11]. However, for patients with acute pain, diminished quality of life, or compromised spinal stability, surgical interventions like kyphoplasty have gained prominence as they provide immediate pain relief, restore vertebral height, and improve function[

11].

Economic Impact of Vertebral Compression Fractures: The economic impact of vertebral compression fractures is a matter of increasing concern. The financial implications extend to both healthcare systems and society at large. Hospitalization costs associated with these fractures are substantial. Patients often require extended hospital stays for pain management and rehabilitation [

11]. Specialized care units, particularly for elderly individuals, are necessary to address their specific needs, adding to the overall expenses. Rehabilitation costs, encompassing physical therapy, occupational therapy, and long-term care, constitute a significant portion of the economic burden [

11]. These services aim to enhance patients' recovery and functional independence, but they also come with substantial financial commitments.

Long-term care and assistance for individuals who continue to experience pain, disability, and impaired mobility following vertebral compression fractures can place a heavy financial strain on both healthcare institutions and families. The cost of caring for these patients extends beyond direct healthcare expenses and includes the indirect costs related to lost productivity and decreased quality of life.

The indirect costs associated with vertebral compression fractures are a significant component of the overall economic burden. Patients experiencing these fractures often face restrictions in their daily activities and may require assistance from family members or professional caregivers. This limitation in independence can lead to lost workdays and decreased productivity, not only for the patients themselves but also for their caregivers [

12]. The emotional toll on patients and caregivers is profound and can result in psychological distress, further exacerbating the indirect costs.

However, there is potential for early intervention, such as kyphoplasty, to alleviate this economic burden. Kyphoplasty, as a minimally invasive surgical procedure, offers several advantages [

11]. It provides prompt pain relief, which can enable patients to return to their daily activities and work sooner. By stabilizing the fractured vertebrae and restoring vertebral height, kyphoplasty aims to improve function and quality of life, potentially reducing the need for extended rehabilitation and long-term care. The economic implications of kyphoplasty, compared to traditional non-surgical approaches, are the subject of ongoing research [

11,

12]. Still, initial findings suggest that the upfront costs of kyphoplasty may be offset by long-term savings in healthcare and indirect costs [

11,

12]. Therefore, kyphoplasty holds promise as an intervention that not only benefits patients clinically but also offers potential economic advantages by addressing the consequences of vertebral compression fractures more effectively [

11,

12].

2. Material and Methods

We carried out a prospective, randomized clinical trial of patients between 50 and 85 years of age who presented dorsal or lumbar VCF treated by Joline (®) double balloon bipedicular kyphoplasty, operated between February 2020 and June 2022.

Patients treated in our institution (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Spain) with double balloon kyphoplasty were eligible to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Age 50-85 years, (2) Acute thoracic or lumbar fracture diagnosed by MR or TC affecting 1 or two vertebral levels (3) VAS >5 despite opioid treatment (4) Clinically fit for anesthesia and surgery, (5) non-pathologic fractures and (6) signed inform consent. Exclusion cirteria were, infection or tumor, vertebra plan, coagulopathy, more than 2 vertebras affected, previous spine surgery

Patients were randomly assigned to a treatment group with single balloon kyphoplasty or double balloon kyphoplasty.

All surgeries were performed at Valladolid University Hospital Spine Department.

During the immediate postoperative period, the patient was allowed immediate walking, and may wear a semi-rigid brace for comfort until the first follow-up visit.

Follow-up visit were performed at months 1,3,6 and 12 postoperatively. We measured in AP and lateral radiographs the anterior, medium and posterior height of the vertebral body, angle of wedging and regional kyphosis.

Clinical outcomes are analyzed using the Visual Analoge Scale (VAS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) questionnaires.

The presence of intraoperative and postoperative complications was recorded.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using IBM SPSS software version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA), using the Student's t-test, with a significance level set at p<0.05.

3. Surgical Technique

The procedure was performed with general anesthesia or local anesthesia and sedation, depending on the characteristics of the patient. The patient was placed in prone position on a radiolucent table.

An incision of less than 1 cm was made at the height of each of the vertebral pedicles.

The procedure was performed placing two fluoroscopy devices simultaneously: one of them in anteroposterior vision, and the other in lateral vision.

Once the entry point was located, the bone access was made through the vertebral pedicle, with the trocar. With a bone drill a working canal is created in the vertebral body.

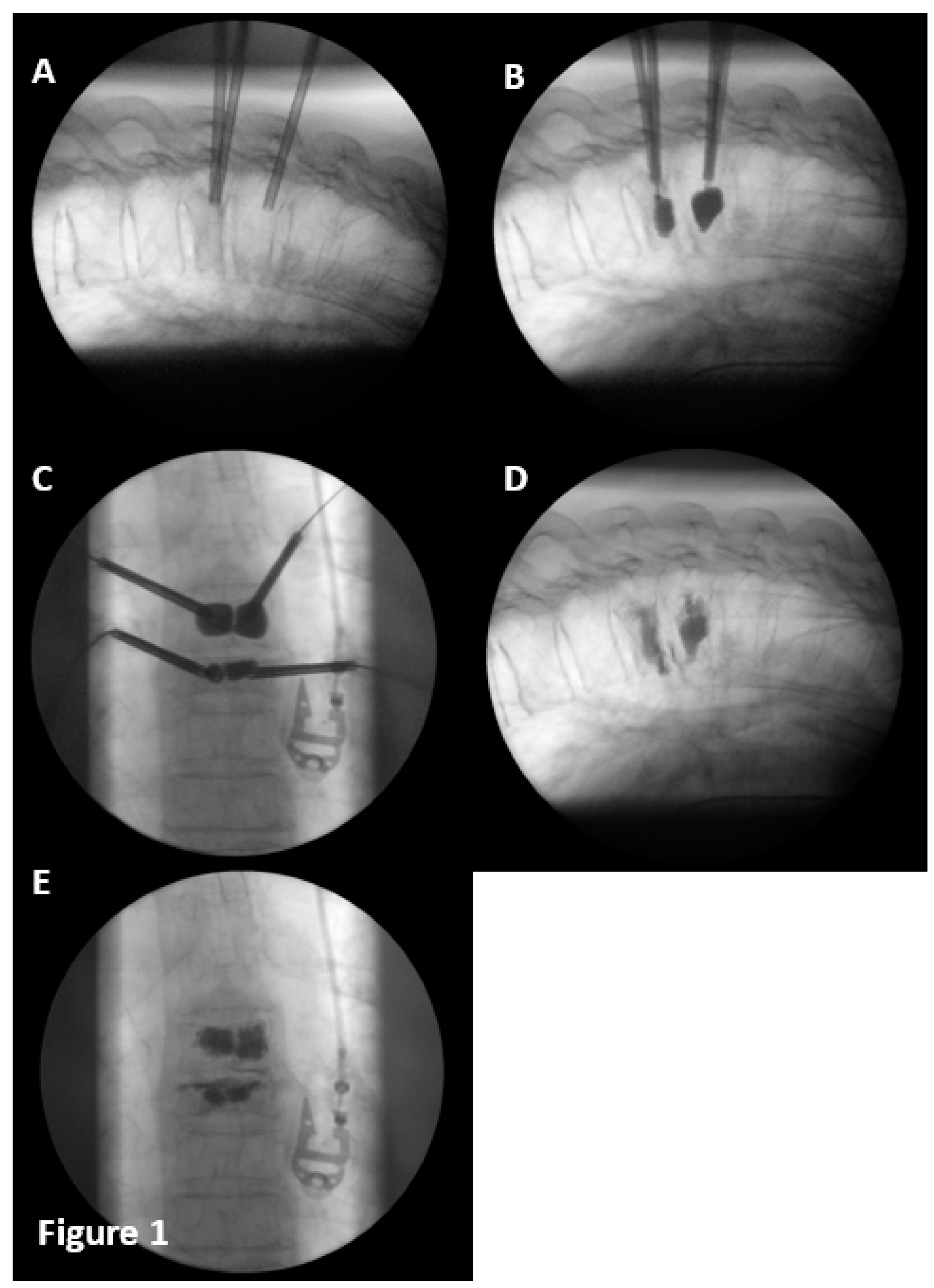

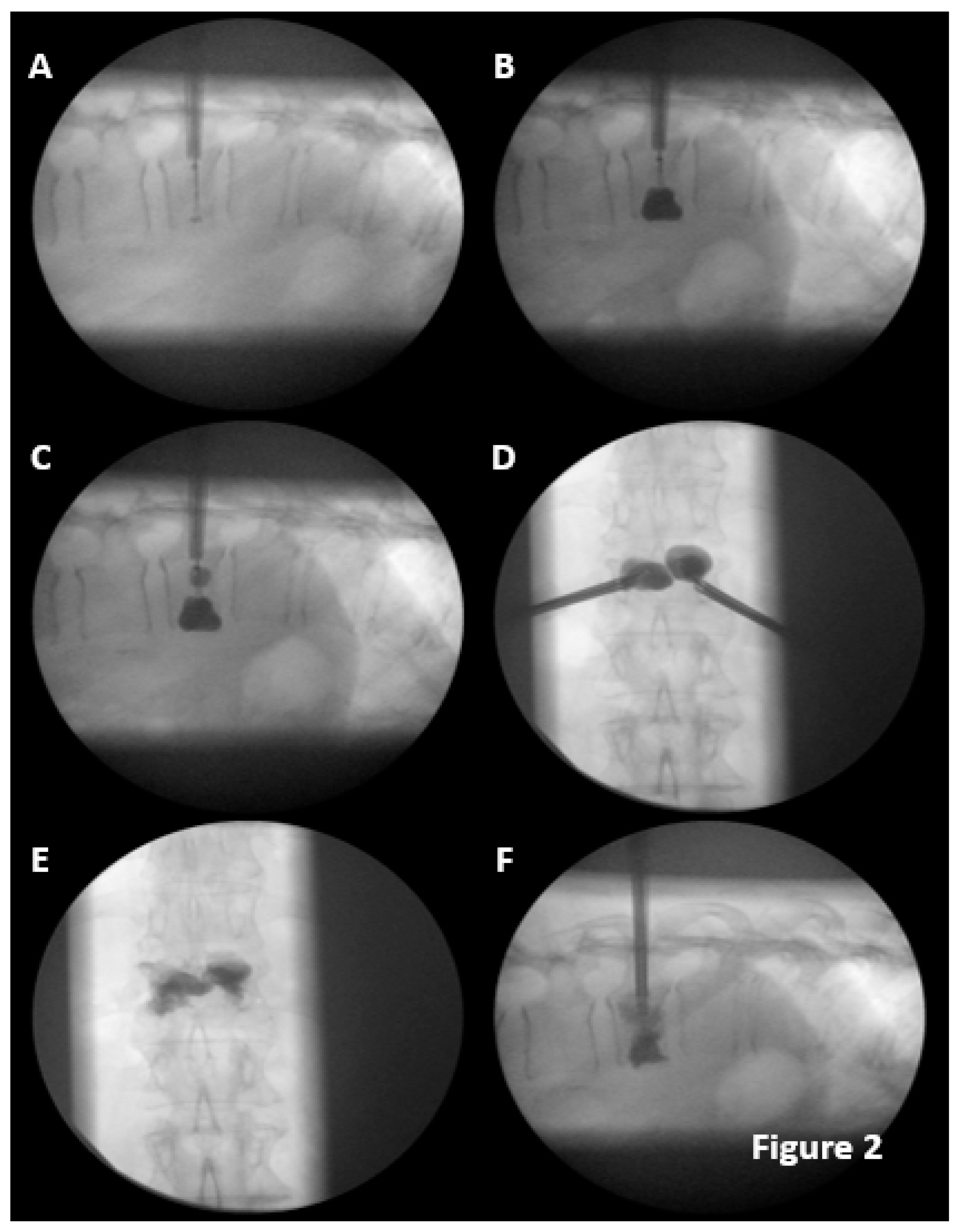

The vertebral reconstruction procedure by balloon kyphoplasty was performed as follows: a simple (

Figure 1) or double (

Figure 2) 8mm balloon was introduced for each vertebral pedicle.

The balloons were independently and gradually inflated until they reach the desired size, and the bone cement was prepared (BoneOs Inject Bone Cement®). The balloons remained inflated until the cement was ready to be introduced.

4. Results

The results of this randomized clinical trial, designed to assess the effectiveness of two different design balloons for kyphoplasty, operated between February 2020 and June 2022, are as follows.

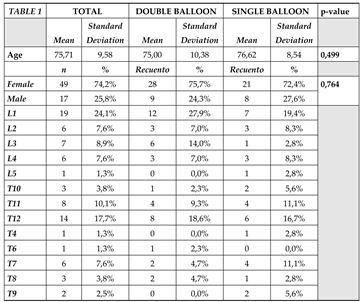

There were no statistically significant differences between both groups in terms of gender, age, and body mass index distribution (

Table 1). The distribution by levels is shown in the table.

As for previous fragility fractures, 3 patients had a history of wrist fractures (2) and humerus fractures (1). Only one patient had antiresorptive treatment and supplementation with calcium and vitamin D. Following surgical treatment, all patients received medical treatment with Calcium-vitamin D and denosumab or Calcium-vitamin D and teriparatide, following the standard treatment guidelines of the hospital. At the 12-month visit, only 54 patients continued with the prescribed medical treatment.

Regarding preoperative anesthetic risk based on the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scale, 46 patients had ASA II, and 21 patients had ASA III.

From the perspective of the anesthetic technique, 51 patients were operated on using local anesthesia and sedation, and 16 patients under general anesthesia.

In total, 5 cement leaks occurred, 2 paravertebral leaks, and 3 disc leaks, with 3 in the double balloon group and 2 in the single balloon group, all of which were asymptomatic. The differences between the two groups were not significant. As for adjacent fractures, 3 occurred in each group, all of which were reintervened using the same technique as the initial surgery, with good clinical outcomes and no complications.

Two patients died one year and three years after the intervention, respectively, due to complications of their underlying pathology not related to the surgical intervention.

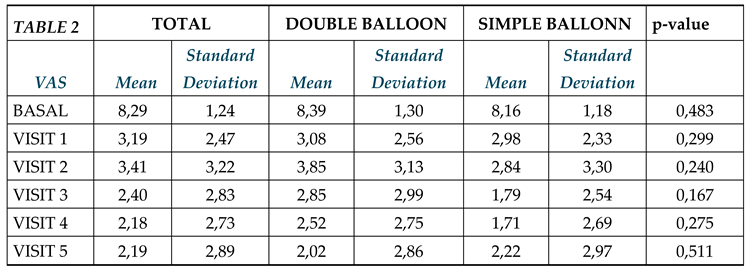

From a clinical point of view, the preoperative overall VAS (Visual Analog Scale) (

Table 2) score, decrease to 5.1 points with a statistically significant after one month. The differences between both groups were not statistically significant in either the preoperative or one-month follow-up values. At one year of follow-up, the VAS scores improved compared to the preoperative and postoperative values in both groups, with statistically significant improvements in both groups.

The average score in the ODI (Oswestry Disability Index) questionnaire prior to surgery was 62 ± 9.53. One month later, the average ODI score was 23.13 ± 11.91. These differences were statistically significant. One year after the intervention, the mean ODI score was 4.57 ± 7.53 (p<0.05). By groups, both in the double balloon and single balloon groups, similar reductions occurred, with no statistically significant differences between them.

From a radiological perspective, in the double balloon group, the anterior vertebral height increased by 2.87 mm at the 30-day review, with a standard deviation of 4.8 mm, remaining stable at the one-year review. In the single balloon group, the increase was 1.64 mm one month after the surgical intervention, with a 0.5 mm loss at one year of follow-up. The differences between the two groups were statistically significant. Regarding the mid-vertebral height, the average increase in the double balloon group was 0.9 mm, with no loss of reduction at 12 months, while in the single balloon group, the height increase was 0.6 mm at the month of surgery, with a 50% reduction at 12 months; the differences between the two groups were not significant. As for the posterior height of the vertebral body, in the double balloon group, there was an increase of 3.02 mm at the month of surgery with a loss of 0.3 mm at one year of follow-up, and in the single balloon group, there was an increase in height of 2.5 mm at the month of surgery with a loss of 0.8 mm at one year of follow-up, with statistically significant differences between groups.

The other radiological parameter was the local vertebral angle. In the double balloon group, a reduction of 2.4° (standard deviation 4.7°) was achieved at the month of surgery, with a loss of 0.2° at one year of follow-up. In the single balloon group, the angular reduction was 1.08° (standard deviation 3.2°) at the month, with a loss of correction at the one-year follow-up. The differences between both groups were statistically significant. In our study, the mean age of patients was approximately 75 years, and there was a relatively even gender distribution.

5. Discussion

The increase of the population over 65 years-old will be exponential in the coming years, estimated at up to 23.4% by 2060 in the USA and up to 1.5 times in the European Union [

13,

14]. This increase will be associated with a greater number of patients with osteoporosis and vertebral compression fractures with associated comorbidities [

15,

16].

The distribution of ASA scores reflects the preoperative anesthetic risk assessment. In your study, a significant portion of patients had ASA II or ASA III, indicating a moderate to severe level of systemic disease. This aligns with what is commonly seen in kyphoplasty procedures involving elderly patients with comorbidities [

6,

17]

The use of local anesthesia and sedation in the majority of cases is in line with the trend in minimally invasive procedures to minimize the risks associated with general anesthesia.

The occurrence of cement leaks and adjacent fractures is noteworthy. The fact that these complications were asymptomatic is consistent with previous findings in the literature [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], suggesting that such events most of the times do not lead to clinical symptoms or complications. It is important that any modification of the previous design, as the double balloon, keeps the safety parameters within line of the existing data.

The similar occurrence of complications in both the double balloon and single balloon groups supports the idea that the choice of balloon design may not significantly impact these complications, so it is understandable that the implementation of the design does not affect the safety of the procedure [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The reduction in VAS scores from 8.29 to 5.1 points at one month and further improvements at one year suggest significant pain relief following kyphoplasty, which is consistent with the literature [

24,

25,

26].

The improvement in ODI scores indicates enhanced functional outcomes. While the exact values may vary, the direction of improvement aligns with previous studies on kyphoplasty [

24,

25,

26].

The improvement in vertebral height, both anterior and posterior, and the reduction in local vertebral angle in the double balloon group are encouraging findings. The literature has shown that restoration of vertebral height and alignment is a crucial aspect of successful kyphoplasty.

6. Conclusions

The differences between the double and single balloon groups in terms of vertebral height restoration and angle reduction, specially at 1 year follow up, should be explored further to understand wether the double balloon provides a higher stability to the VCF and the clinical implications.

Our study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness and safety of kyphoplasty using different balloon designs, demonstrating pain relief, functional improvement, and positive radiological outcomes.

The similarity in outcomes between the double and single balloon groups raises questions about the potential advantages of one design over the other. Further research or meta-analyses could help clarify this aspect.

This study contributes to the body of knowledge on kyphoplasty, and further research may help refine the technique and improve patient outcomes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Silvia Santiago and David C. Noriega; data curation, Silvia Santiago and Jesús Crespo; Formal analysis, Silvia Santiago; Investigation, Silvia Santiago, Jesús Crespo-Sanjuán, Francisco Ardura, Rubén Hernández Ramajo, Gregorio Labrador, María Bragado; Methodology, Silvia Santiago, Franciso Ardura, Alberto Caballero-García, Project Administration, David C Noriega and Alberto Caballero-García; Supervision, David C. Noriega and Francisco Ardura; validation, David C. Noriega, visualization, David C. Noriega and Jesús Crespo-Sanjuán; writing original draft, Silvia Santiago and David Noriega, Writing-review & editing, David C. Noriega and Jesús Crespo-Sanjuán.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to data protection lay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kado, D.M. Osteoporosis in Older Adults: The Importance of Fractures, Falls, and Fracture Risk Assessment. J Am Med Assoc. 2014, 312, 2115–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Atkinson, E.J.; O'Fallon, W.M.; Melton, L.J. Incidence of Clinically Diagnosed Vertebral Fractures: A Population-Based Study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985-1989. J Bone Miner Res. 1992, 7, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. An Estimate of the Worldwide Prevalence and Disability Associated with Osteoporotic Fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006, 17, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C, et al. Risk of New Vertebral Fracture in the Year Following a Fracture. J Am Med Assoc. 2001, 285, 320–323.

- Delmas, P.D.; van de Langerijt, L.; Watts, N.B.; Eastell, R.; Genant, H.; Grauer, A. Underdiagnosis of Vertebral Fractures Is a Worldwide Problem: The IMPACT Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005, 20, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, S.L. Quality-of-Life Issues in Osteoporosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005, 7, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, S.D.; Miller, R.R. Falls: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Relationship to Fracture. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008, 6, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim SH, Kang HS, Kim JH, et al. Compression Fractures of the Spine in Osteoporotic Patients: The Clinical Features and Multidisciplinary Treatment. Int Orthop. 2001, 25, 293–296.

- Cooper C, Campbell L, Egger P, et al. Operation of an Orthogeriatric Service and Its Impact on Hip Fracture Patients. Age Ageing. 1995, 24, 113–119.

- Edidin, A.A.; Ong, K.L.; Lau, E.; Kurtz, S.M. Morbidity and Mortality After Vertebral Fractures: Comparison of Vertebral Augmentation and Nonoperative Management in the Medicare Population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015, 40, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauley, J.A. Public Health Impact of Osteoporosis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013, 68, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, S.L. Quality-of-life aspects in osteoporosis treatment. Osteoporosis International. 2005, 16(Suppl 2):S155-S159.

- United States Census Bureau. An aging nation: projected number of children and older adults. 2019 Oct 8. https://www.census.gov/ library/visualizations/2018/comm/historicfirst.

- Kluge, F.A.; Goldstein, J.R. Transfers in an aging European Union. J Econ Ageing. 2019 May;13: 45-54.

- Wagner, S.C.; Formby, P.M.; Helgeson, M.D.; Kang, D.G. Diagnosing the undiagnosed:osteoporosis in patients undergoing lumbar fusion. Spine. 2016 Nov 1;41(21):E1279-83.

- Diebo, B.G.; Sheikh, B.; Freilich, M.; Shah, N.V.; Redfern, J.A.I.; Tarabichi, S.; Shepherd, E.M.; Lafage, R.; Passias, P.G.; Najjar, S.; Schwab, F.J.; Lafage, V.; Paulino, C.B. Osteoporosis and Spine Surgery: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2020 Jun;8, e0160.

- Halvachizadeh, S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 3 Treatment Arms for Vertebral Compression FracturesA Comparison of Improvement in Pain, Adjacent-Level Fractures, andQuality of Life Between Vertebroplasty, Kyphoplasty, and Nonoperative ManagementJBJS REVIEWS 2021, 9, e21.00045. [CrossRef]

- Voormolen, M.H.J.; Lohle, P.N.; Lampmann, L.E.; van den Wildenberg, W.; Juttmann, J.R.; Diekerhof, C.H.; de Waal Malefijt, J. rospective clinical follow-up after percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. J.

- Korovessis, P.; Vardakastanis, K.; Repantis, T.; Vitsas, V. Balloon kyphoplasty versus KIVAvertebral augmentation—comparison of 2 techniques for osteoporotic vertebral body fractures: a prospective randomized study.Spine. 2013 Feb 15;38, 292-9.

- Dohm M, Black CM, Dacre A, Tillman JB,Fueredi G; KAVIAR investigators. A randomizedtrial comparing balloon kyphoplasty andvertebroplasty for vertebral compressionfractures due to osteoporosis. AJNR Am Neuroradiol. 2014 Dec;35, 2227-36.

- Evans AJ, Kip KE, Brinjikji W, Layton KF,Jensen ML, Gaughen JR, Kallmes DF.Randomized controlled trial of vertebroplasty versus kyphoplasty in the treatment of vertebral compression fractures. J NeurointervSurg. 2016 Jul;8, 756-63.

- Blasco, J.; Martinez-Ferrer, A.; Macho, J.; San Roman, L.; Pom´es, J.; Carrasco, J.; Monegal, A.; Guañabens, N.; Peris, P. Effect of vertebroplasty on pain relief, quality of life, and the incidenceof new vertebral fractures: a 12-month randomized follow-up, controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 May;27, 1159-66.

- Klazen CA, Lohle PN, de Vries J, Jansen FH,Tielbeek AV, Blonk MC, Venmans A, van RooijWJ, Schoemaker MC, Juttmann JR, Lo TH,Verhaar HJ, van der Graaf Y, van Everdingen KJ,Muller AF, ElgersmaOE, HalkemaDR, Fransen H,Janssens X, Buskens E, Mali WP. Vertebroplasty versus conservative treatment in acuteosteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (Vertos II): an open-label randomised trial.Lancet. 2010 Sep 25;376(9746):1085-92.

- Chen D, An ZQ, Song S, Tang JF, Qin H.Percutaneous vertebroplasty compared withconservative treatment in patients with chronicpainful osteoporotic spinal fractures. J ClinNeurosci. 2014 Mar;21, 473-7.

- Wardlaw, D.; Cummings, S.R.; Van Meirhaeghe, J.; Bastian, L.; Tillman, J.B.; Ranstam, J.; Eastell, R.; Shabe, P.; Talmadge, K.; Boonen, S. Efficacy andsafety of balloon kyphoplasty compared withnon-surgical care for vertebral compressionfracture (FREE): a randomised controlled trial.Lancet. 2009 Mar 21;373, 1016-24.

- Rousing, R.; Andersen, M.O.; Jespersen, S.M.; Thomsen, K.; Lauritsen, J. Percutaneous vertebroplasty compared to conservative treatment in patients with painful acute or subacute osteoporotic vertebral fractures: three-months follow-up in a clinical randomized study. Spine. 2009 Jun 1;34, 1349-54.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).