Submitted:

14 November 2023

Posted:

14 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Literature Review

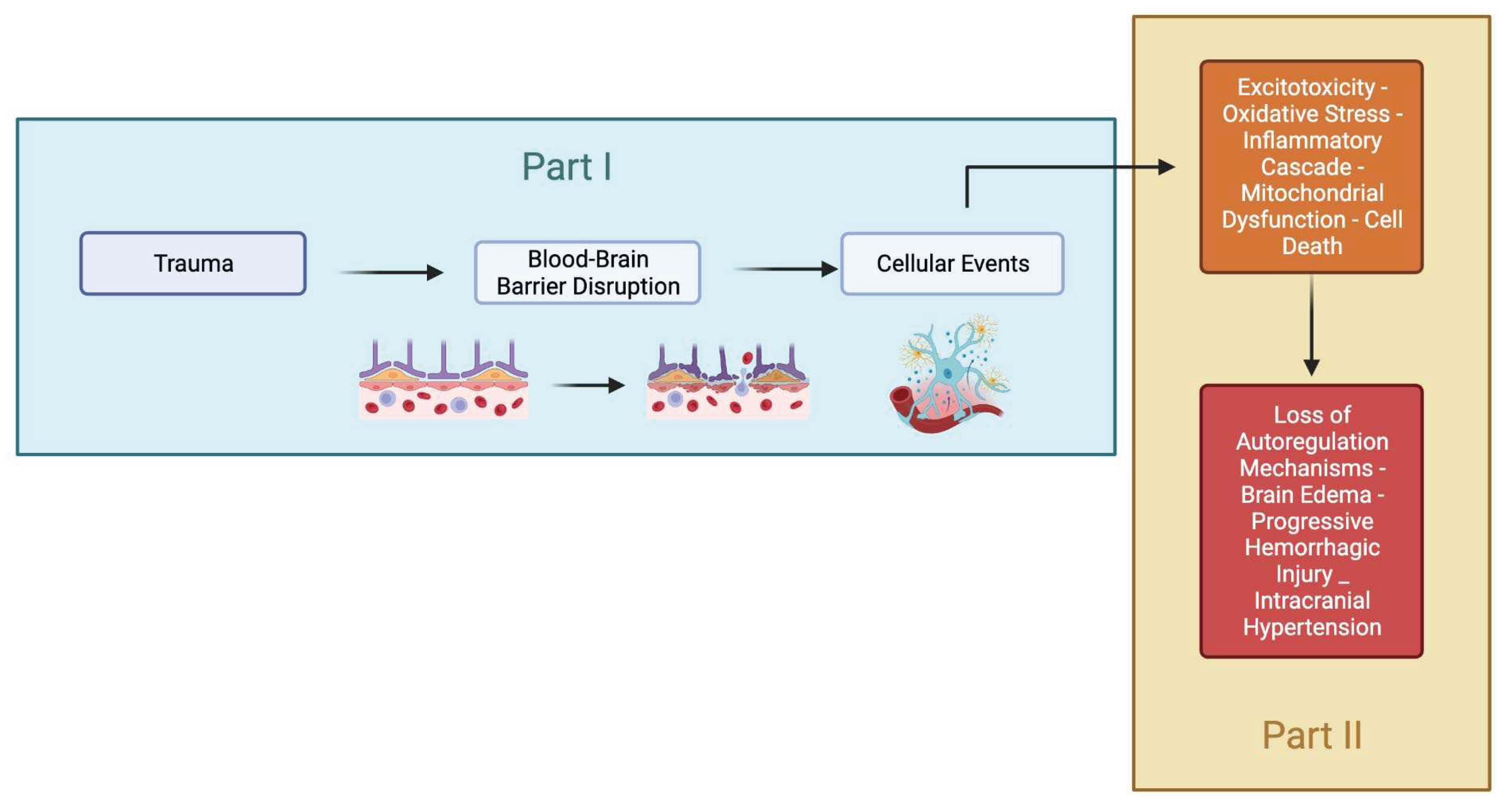

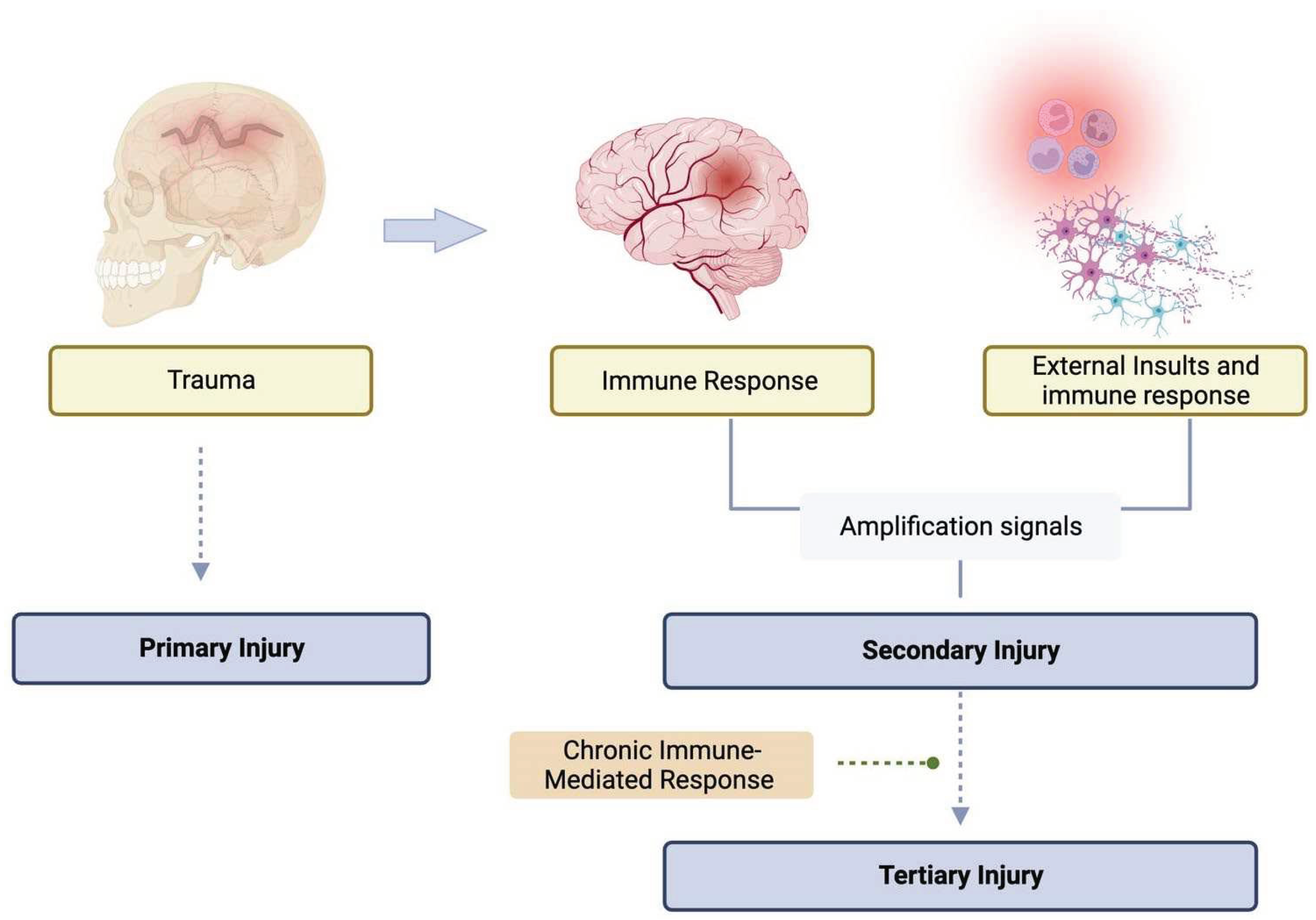

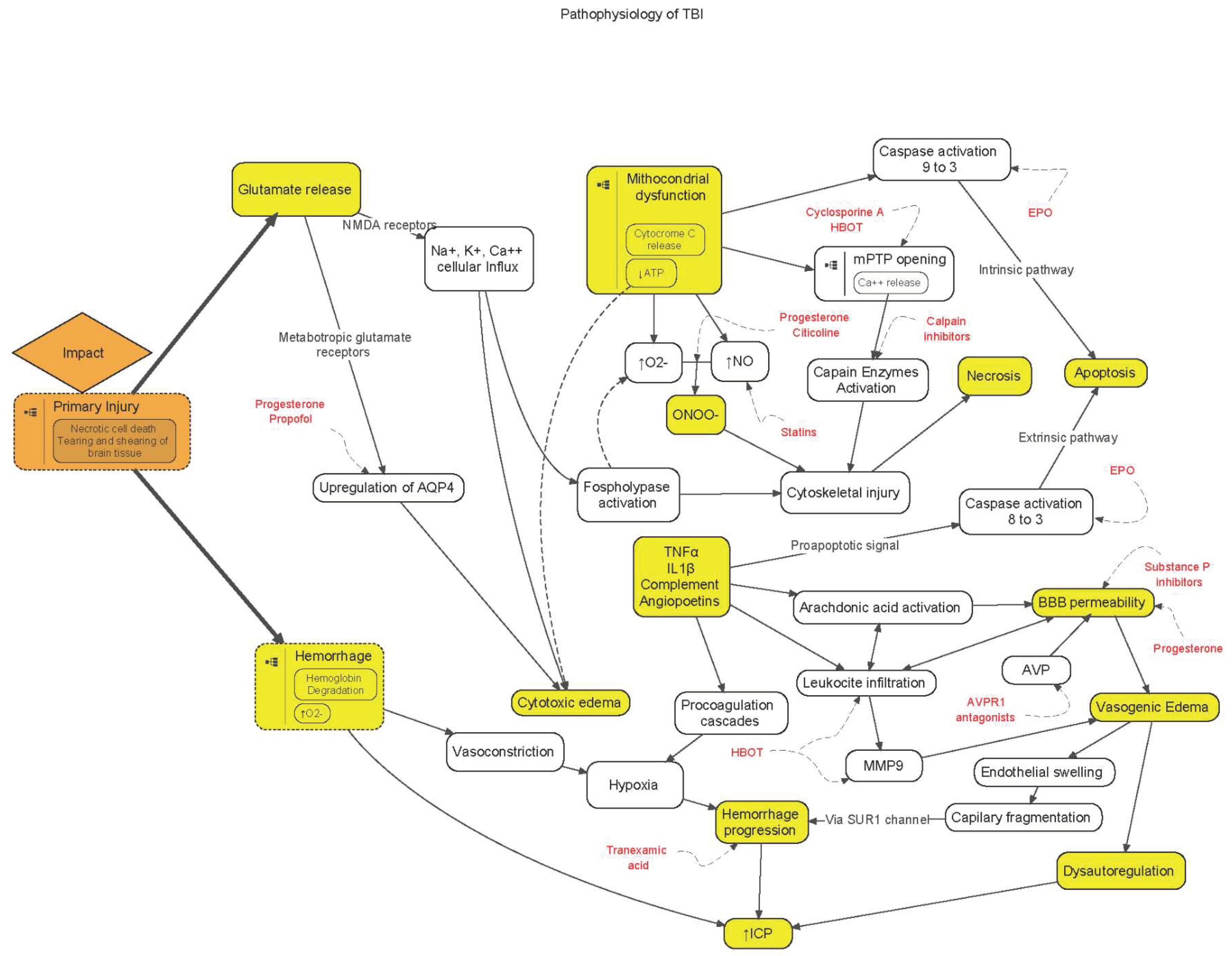

3.1. Pathophysiology of Secondary Brain Injury

3.2. Sequelae from the Primary Impact

3.2.1. Cellular Events

Excitotoxicity and Calcium

Specific Treatment

Free Radicals and Oxidative Stress in Traumatic Brain Injury

Specific Treatment

Inflammatory Mediators and Cascades

Treatments Based on the Pathway Level

Other Neuroinflammatory Components

Specific Treatment

Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Traumatic Brain Injury

Specific Treatment

Cell Death

Specific Treatment

3.2.2. BBB Disruption and Neutrophil Invasion

Specific Treatment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langlois, J.A.; Rutland-Brown, W.; Wald, M.M. The Epidemiology and Impact of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Brief Overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2006, 21, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.Y.; Lee, A.Y.W. Traumatic Brain Injuries: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P.; Sharma, S. Recent Advances in Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. CN 2018, 16, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, A.; Carpenter, K.L.; Menon, D.K.; Pickard, J.D.; Hutchinson, P.J. The Cytokine Response to Human Traumatic Brain Injury: Temporal Profiles and Evidence for Cerebral Parenchymal Production. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011, 31, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhry, S.M.; Trask, A.L.; Waller, M.A.; Watts, D.D. Management of Brain-Injured Patients by an Evidence-Based Medicine Protocol Improves Outcomes and Decreases Hospital Charges. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 2004, 56, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawryluk, G.W.J.; Rubiano, A.M.; Totten, A.M.; O’Reilly, C.; Ullman, J.S.; Bratton, S.L.; Chesnut, R.; Harris, O.A.; Kissoon, N.; Shutter, L.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: 2020 Update of the Decompressive Craniectomy Recommendations. Neurosurg. 2020, 87, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghupathi, R. Cell Death Mechanisms Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Pathology 2004, 14, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahriman, A.; Bouley, J.; Smith, T.W.; Bosco, D.A.; Woerman, A.L.; Henninger, N. Mouse Closed Head Traumatic Brain Injury Replicates the Histological Tau Pathology Pattern of Human Disease: Characterization of a Novel Model and Systematic Review of the Literature. acta neuropathol commun 2021, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Zhong, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Su, Z.; Zheng, W.; Guan, X. The Effects of Magnesium Sulfate Therapy after Severe Diffuse Axonal Injury. TCRM 2016, 12, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, M.; Dreier, J.P.; Fabricius, M.; Hartings, J.A.; Graf, R.; Strong, A.J. Clinical Relevance of Cortical Spreading Depression in Neurological Disorders: Migraine, Malignant Stroke, Subarachnoid and Intracranial Hemorrhage, and Traumatic Brain Injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011, 31, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeev, I.; Carpenter, K.L.H.; Nortje, J.; Al-Rawi, P.G.; O’Connell, M.T.; Czosnyka, M.; Smielewski, P.; Pickard, J.D.; Menon, D.K.; Kirkpatrick, P.J.; et al. Cerebral Extracellular Chemistry and Outcome Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Microdialysis Study of 223 Patients. Brain 2011, 134, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verweij, B.H.; Muizelaar, J.P.; Vinas, F.C.; Peterson, P.L.; Xiong, Y.; Lee, C.P. Impaired Cerebral Mitochondrial Function after Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. Journal of Neurosurgery 2000, 93, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wible, E.F.; Laskowitz, D.T. Statins in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rühl, L.; Kuramatsu, J.B.; Sembill, J.A.; Kallmünzer, B.; Madzar, D.; Gerner, S.T.; Giede-Jeppe, A.; Balk, S.; Mueller, T.; Jäger, J.; et al. Amantadine Treatment Is Associated with Improved Consciousness in Patients with Non-Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2022, 93, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baracaldo-Santamaría, D.; Ariza-Salamanca, D.F.; Corrales-Hernández, M.G.; Pachón-Londoño, M.J.; Hernandez-Duarte, I.; Calderon-Ospina, C.-A. Revisiting Excitotoxicity in Traumatic Brain Injury: From Bench to Bedside. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikonomidou, C.; Turski, L. Why Did NMDA Receptor Antagonists Fail Clinical Trials for Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injury? The Lancet Neurology 2002, 1, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shohami, E.; Biegon, A. Novel Approach to the Role of NMDA Receptors in Traumatic Brain Injury. CNSNDDT 2014, 13, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergouwen, M.D.; Vermeulen, M.; Roos, Y.B. Effect of Nimodipine on Outcome in Patients with Traumatic Subarachnoid Haemorrhage: A Systematic Review. The Lancet Neurology 2006, 5, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temkin, N.; Machamer, J.; Dikmen, S.; Nelson, L.D.; Barber, J.; Hwang, P.H.; Boase, K.; Stein, M.B.; Sun, X.; Giacino, J.; et al. Risk Factors for High Symptom Burden Three Months after Traumatic Brain Injury and Implications for Clinical Trial Design: A Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury Study. Journal of Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Mahmood, A.; Chopp, M. Animal Models of Traumatic Brain Injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-D.; Fang, H.-Y.; Pang, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.-Z.; Zhou, L.-L.; Bai, G.-H.; Sheng, H.-S. Giant Pediatric Supratentorial Tumor: Clinical Feature and Surgical Strategy. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 870951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, V.C. Drug Targets for Traumatic Brain Injury from Poly(ADP-Ribose)Polymerase Pathway Modulation. British Journal of Pharmacology 2009, 157, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, K.M.; Littleton-Kearney, M.T. The Role of Free Radicals in Traumatic Brain Injury. Biological Research For Nursing 2013, 15, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, R.S.; Amiridze, N.; Aarabi, B. Nitrotyrosine as an Oxidative Stress Marker: Evidence for Involvement in Neurologic Outcome in Human Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection & Critical Care 2007, 63, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisenbaum, E.J.; Novikov, D.S.; Lui, Y.W. The Presence and Role of Iron in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: An Imaging Perspective. Journal of Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secades, J.J. Role of Citicoline in the Management of Traumatic Brain Injury. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafonte, R.D.; Bagiella, E.; Ansel, B.M.; Novack, T.A.; Friedewald, W.T.; Hesdorffer, D.C.; Timmons, S.D.; Jallo, J.; Eisenberg, H.; Hart, T.; et al. Effect of Citicoline on Functional and Cognitive Status Among Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: Citicoline Brain Injury Treatment Trial (COBRIT). JAMA 2012, 308, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susanto, M.; Pangihutan Siahaan, A.M.; Wirjomartani, B.A.; Setiawan, H.; Aryanti, C. ; Michael The Neuroprotective Effect of Statin in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurgery: X 2023, 19, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capizzi, A.; Woo, J.; Verduzco-Gutierrez, M. Traumatic Brain Injury. Medical Clinics of North America 2020, 104, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, K.J. Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America 2017, 28, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.L.; Hong, J.-S. Microglia and Inflammation-Mediated Neurodegeneration: Multiple Triggers with a Common Mechanism. Progress in Neurobiology 2005, 76, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corps, K.N.; Roth, T.L.; McGavern, D.B. Inflammation and Neuroprotection in Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurol 2015, 72, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morganti-Kossmann, M.C.; Rancan, M.; Stahel, P.F.; Kossmann, T. Inflammatory Response in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: A Double-Edged Sword. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 2002; 8, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Kroner, A. Repertoire of Microglial and Macrophage Responses after Spinal Cord Injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011, 12, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Loane, D.J. Neuroinflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury: Opportunities for Therapeutic Intervention. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2012, 26, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loane, D.J.; Kumar, A.; Stoica, B.A.; Cabatbat, R.; Faden, A.I. Progressive Neurodegeneration After Experimental Brain Trauma: Association With Chronic Microglial Activation. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2014, 73, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Malik, R.; Singh, G.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Mohan, S.; Albratty, M.; Albarrati, A.; Tambuwala, M.M. Pathogenesis and Management of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Role of Neuroinflammation and Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Inflammopharmacol 2022, 30, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davalos, D.; Grutzendler, J.; Yang, G.; Kim, J.V.; Zuo, Y.; Jung, S.; Littman, D.R.; Dustin, M.L.; Gan, W.-B. ATP Mediates Rapid Microglial Response to Local Brain Injury in Vivo. Nat Neurosci 2005, 8, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.P.-Y.; Tung, J.Y.-L.; Ku, D.T.-L.; Luk, C.-W.; Ling, A.S.-C.; Kwong, D.L.-W.; Cheng, K.K.-F.; Ho, W.W.-S.; Shing, M.M.-K.; Chan, G.C.-F. Outcome of Chinese Children with Craniopharyngioma: A 20-Year Population-Based Study by the Hong Kong Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Study Group. Childs Nerv Syst 2020, 36, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P.; Camandola, S. NF-κB in Neuronal Plasticity and Neurodegenerative Disorders. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 107, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Mu, X.S.; Hayes, R.L. Increased Cortical Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) DNA Binding Activity after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Neuroscience Letters 1995, 197, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.A.; Kang, Y.; Sanchez-Molano, J.; Furones, C.; Atkins, C.M. STAT3 Signaling after Traumatic Brain Injury: STAT3 Activation after Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurochemistry 2012, 120, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonell, W.S.; Mandell, J.W. Transient Neuronal but Persistent Astroglial Activation of ERK/MAP Kinase after Focal Brain Injury in Mice. Journal of Neurotrauma 2003, 20, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, W.D.; Bramlett, H.M. Therapeutic Hypothermia and Targeted Temperature Management in Traumatic Brain Injury: Clinical Challenges for Successful Translation. Brain Research 2016, 1640, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebell, J.M.; Morganti-Kossmann, M.C. Involvement of Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines in the Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherbel, U.; Raghupathi, R.; Nakamura, M.; Saatman, K.E.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Neugebauer, E.; Marino, M.W.; McIntosh, T.K. Differential Acute and Chronic Responses of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Deficient Mice to Experimental Brain Injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999, 96, 8721–8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinz, E.H.; Kochanek, P.M.; Dixon, C.E.; Clark, R.S.B.; Carcillo, J.A.; Schiding, J.K.; Chen, M.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Carlos, T.M.; Williams, D.; et al. Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Is an Endogenous Neuroprotectant after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats and Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1999, 104, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.K.; Aneja, R.K.; Bell, M.J.; Bayir, H.; Feldman, K.; Adelson, P.D.; Fink, E.L.; Kochanek, P.M.; Clark, R.S.B. Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of High-Mobility Group Box 1 and Cytochrome C Predict Outcome after Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, M.D.; Shields, J.S.; Sukumari-Ramesh, S.; Kimbler, D.E.; Fessler, R.D.; Shakir, B.; Youssef, P.; Yanasak, N.; Vender, J.R.; Dhandapani, K.M. High Mobility Group Box Protein-1 Promotes Cerebral Edema after Traumatic Brain Injury via Activation of Toll-like Receptor 4. Glia 2014, 62, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Z.; Savitz, S.I.; Yang, J.; Degterev, A.; Yuan, J.; Cuny, G.D.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Whalen, M.J. Necrostatin-1 Reduces Histopathology and Improves Functional Outcome after Controlled Cortical Impact in Mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008, 28, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, P.M.; Clark, R.S.B.; Ruppel, R.A.; Adelson, P.D.; Bell, M.J.; Whalen, M.J.; Robertson, C.L.; Satchell, M.A.; Seidberg, N.A.; Marion, D.W.; et al. Biochemical, Cellular, and Molecular Mechanisms in the Evolution of Secondary Damage after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Infants and Children: Lessons Learned from the Bedside. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 2000; 1, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, B.; Boraso, M.; Marchetti, N.; Marinovich, M. Perspectives on Neuroinflammation and Excitotoxicity: A Neurotoxic Conspiracy? NeuroToxicology 2014, 43, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, J.D.; Exo, J.L.; Jackson, T.C.; Ren, J.; Gillespie, D.G.; Dubey, R.K.; Kochanek, P.M.; Jackson, E.K. Expression of the 2′,3′-cAMP-Adenosine Pathway in Astrocytes and Microglia: 2′,3′-cAMP Metabolism in Astrocytes and Microglia. Journal of Neurochemistry 2011, 118, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederberg, D.; Siesjö, P. What Has Inflammation to Do with Traumatic Brain Injury? Childs Nerv Syst 2010, 26, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohi, K.; Kraemer, B.C.; Erickson, M.A.; McMillan, P.J.; Kovac, A.; Flachbartova, Z.; Hansen, K.M.; Shah, G.N.; Sheibani, N.; Salameh, T.; et al. Molecular Hydrogen in Drinking Water Protects against Neurodegenerative Changes Induced by Traumatic Brain Injury. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-F.; Hsu, C.-W.; Huang, W.-H.; Wang, J.-Y. Post-Injury Baicalein Improves Histological and Functional Outcomes and Reduces Inflammatory Cytokines after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury: Baicalein Reduces Cytokine Expression in TBI. British Journal of Pharmacology 2008, 155, 1279–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokiko-Cochran, O.N.; Godbout, J.P. The Inflammatory Continuum of Traumatic Brain Injury and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thelin, E.P.; Hall, C.E.; Gupta, K.; Carpenter, K.L.H.; Chandran, S.; Hutchinson, P.J.; Patani, R.; Helmy, A. Elucidating Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Responses after Traumatic Brain Injury in a Human Stem Cell Model. Journal of Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.D.; Peterson, T.C.; Vonder Haar, C.; Kantor, E.D.; Farin, F.M.; Bammler, T.K.; MacDonald, J.W.; Hoane, M.R. Comparison of the Effects of Erythropoietin and Anakinra on Functional Recovery and Gene Expression in a Traumatic Brain Injury Model. Front. Pharmacol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, D.W.; McGeachy, M.J.; Bayır, H.; Clark, R.S.B.; Loane, D.J.; Kochanek, P.M. The Far-Reaching Scope of Neuroinflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury. Nat Rev Neurol 2017, 13, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzeo, A.T.; Kunene, N.K.; Gilman, C.B.; Hamm, R.J.; Hafez, N.; Bullock, M.R. Severe Human Traumatic Brain Injury, but Not Cyclosporin A Treatment, Depresses Activated T Lymphocytes Early after Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 2006, 23, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Ishii, H.; Bai, Z.; Itokazu, T.; Yamashita, T. Temporal Changes in Cell Marker Expression and Cellular Infiltration in a Controlled Cortical Impact Model in Adult Male C57BL/6 Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitner, J.C.S. Inflammatory Processes and Antiinflammatory Drugs in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Current Appraisal. Neurobiology of Aging 1996, 17, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilli, M.; Pizzi, M.; Memo, M.; Spano, P. Neuroprotection by Aspirin and Sodium Salicylate Through Blockade of NF-κB Activation. Science 1996, 274, 1383–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, H.B.; Piantadosi, C.A. Mitochondrial Quality Control as a Therapeutic Target. Pharmacol Rev 2016, 68, 20–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.T.; Ji, J.; Dagda, R.K.; Jiang, J.F.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Kapralov, A.A.; Tyurin, V.A.; Yanamala, N.; Shrivastava, I.H.; Mohammadyani, D.; et al. Cardiolipin Externalization to the Outer Mitochondrial Membrane Acts as an Elimination Signal for Mitophagy in Neuronal Cells. Nat Cell Biol 2013, 15, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.S.; He, Q.; Janczy, J.R.; Elliott, E.I.; Zhong, Z.; Olivier, A.K.; Sadler, J.J.; Knepper-Adrian, V.; Han, R.; Qiao, L.; et al. Mitochondrial Cardiolipin Is Required for Nlrp3 Inflammasome Activation. Immunity 2013, 39, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurr, A.; Payne, R.S. Lactate, Not Pyruvate, Is Neuronal Aerobic Glycolysis End Product: An in Vitro Electrophysiological Study. Neuroscience 2007, 147, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-L.; Lin, T.-Y.; Chen, P.-L.; Guo, T.-N.; Huang, S.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Chan, C.-C. Mitochondrial Function and Parkinson’s Disease: From the Perspective of the Electron Transport Chain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 797833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiebert, J.B.; Shen, Q.; Thimmesch, A.R.; Pierce, J.D. Traumatic Brain Injury and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2015, 350, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, A.G.; Alshboul, O.A. Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2013, 18, 222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia, M.; Kumar, M.; Ahluwalia, P.; Rahimi, S.; Vender, J.R.; Raju, R.P.; Hess, D.C.; Baban, B.; Vale, F.L.; Dhandapani, K.M.; et al. Rescuing Mitochondria in Traumatic Brain Injury and Intracerebral Hemorrhages - A Potential Therapeutic Approach. Neurochemistry International 2021, 150, 105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, W.; Smith, D.H. Axonal Pathology in Traumatic Brain Injury. Experimental Neurology 2013, 246, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, J.P.; Nahed, B.V.; Madden, M.W.; Oliveira, S.M.; Springer, S.; Bhere, D.; Chi, A.S.; Wakimoto, H.; Rothenberg, S.M.; Sequist, L.V.; et al. Brain Tumor Cells in Circulation Are Enriched for Mesenchymal Gene Expression. Cancer Discovery 2014, 4, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wu, F.; Yang, P.; Shao, J.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, R. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Therapeutic Hypothermia in Adult Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care 2019, 23, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdan, M.; Mauritz, W.; Wilbacher, I.; Brazinova, A.; Rusnak, M.; Leitgeb, J. Barbiturates Use and Its Effects in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Five European Countries. Journal of Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, C.; Engelhard, K. Pathophysiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2007, 99, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldadah, B.A.; Faden, A.I. Caspase Pathways, Neuronal Apoptosis, and CNS Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 2000, 17, 811–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács-Öller, T.; Zempléni, R.; Balogh, B.; Szarka, G.; Fazekas, B.; Tengölics, Á.J.; Amrein, K.; Czeiter, E.; Hernádi, I.; Büki, A.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Microglial and Caspase3 Activation in the Retina. IJMS 2023, 24, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatman, K.E.; Creed, J.; Raghupathi, R. Calpain as a Therapeutic Target in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.C.; Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Apoptosis: Controlled Demolition at the Cellular Level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008, 9, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, R.; Fernandez, S.C.; Murai, H.; Trusko, S.P.; Scott, R.W.; Nishioka, W.K.; McIntosh, T.K. BCL-2 Overexpression Attenuates Cortical Cell Loss after Traumatic Brain Injury in Transgenic Mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998, 18, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Yue, J.K.; Zusman, B.E.; Nwachuku, E.L.; Abou-Al-Shaar, H.; Upadhyayula, P.S.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Puccio, A.M. B-Cell Lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and Regulation of Apoptosis after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Clinical Perspective. Medicina 2020, 56, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, A.J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, G.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Shi, D.; Zhang, T.; Sun, B.; He, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Erythropoietin for Traumatic Brain Injury. BMC Neurol 2020, 20, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, R.M.; Kochanek, P.M.; Simard, J.M. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Cerebral Edema in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neuropharmacology 2019, 145, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballabh, P.; Braun, A.; Nedergaard, M. The Blood–Brain Barrier: An Overview. Neurobiology of Disease 2004, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, R.G.; Lira, M.; Cerpa, W. Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanisms of Glial Response. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 740939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkin, J.J.; Vink, R. Mechanisms of Cerebral Edema in Traumatic Brain Injury: Therapeutic Developments. Current Opinion in Neurology, 2010; 23, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minta, K.; Brinkmalm, G.; Al Nimer, F.; Thelin, E.P.; Piehl, F.; Tullberg, M.; Jeppsson, A.; Portelius, E.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; et al. Dynamics of Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Human Traumatic Brain Injury. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 18075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, R.; Gabrielian, L.; Thornton, E. The Role of Substance P in Secondary Pathophysiology after Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Bayraktutan, U. Substance P Reversibly Compromises the Integrity and Function of Blood-Brain Barrier. Peptides 2023, 167, 171048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadanny, A.; Maroon, J.; Efrati, S. The Efficacy of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in Traumatic Brain Injury Patients: Literature Review and Clinical Guidelines. MRAJ 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Effects in TBI | Highlights | |

|---|---|---|

| IL1β | Detrimental | Raised CSF IL1β correlates with both raised ICP and poorer outcome. The balance between members of the IL1 cytokine family, in particular between IL1β and its endogenous inhibitor IL1ra, is an important determinant of the degree of inflammatory response, rather than the absolute concentration of IL1β. In TBI patients, high microdialysate IL1ra/IL1b ratio is associated to favourable outcomes. |

| TNFα | Detrimental in acute phase and beneficial during the healing process | Upregulated in the injured brain early after trauma, reaching a peak within a few hours following the initial injury. This cytokine triggers the apoptotic cascade but also, pathways resulting in activation of pro-survival genes. |

| IL6 | Beneficial | It is a VEGF, a trophic factor that is upregulated in the CNS after injury and promotes neuronal survival and brain repair through astroglia and vascular remodelling. Following TBI, its concentration rises dramatically. |

| Complement | Detrimental | Complement is the major trigger of inflammatory molecules. That ultimately lead to increase BBB permeability, induction of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules and induction of apoptosis and cell death by creation of pores on cell membranes. |

| Angiopoietins | Beneficial (Ang1) and detrimental (Ang2) | They are family of growth factors that are important in regulating angiogenesis and vascular permeability, and also have been implicated in BBB disruption. TBIs models show acute decrease in Angiopoetin-1 expression and concomitant increase in Angiopoetin-2 which is associated with endothelial apoptosis and BBB permeability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).