Introduction

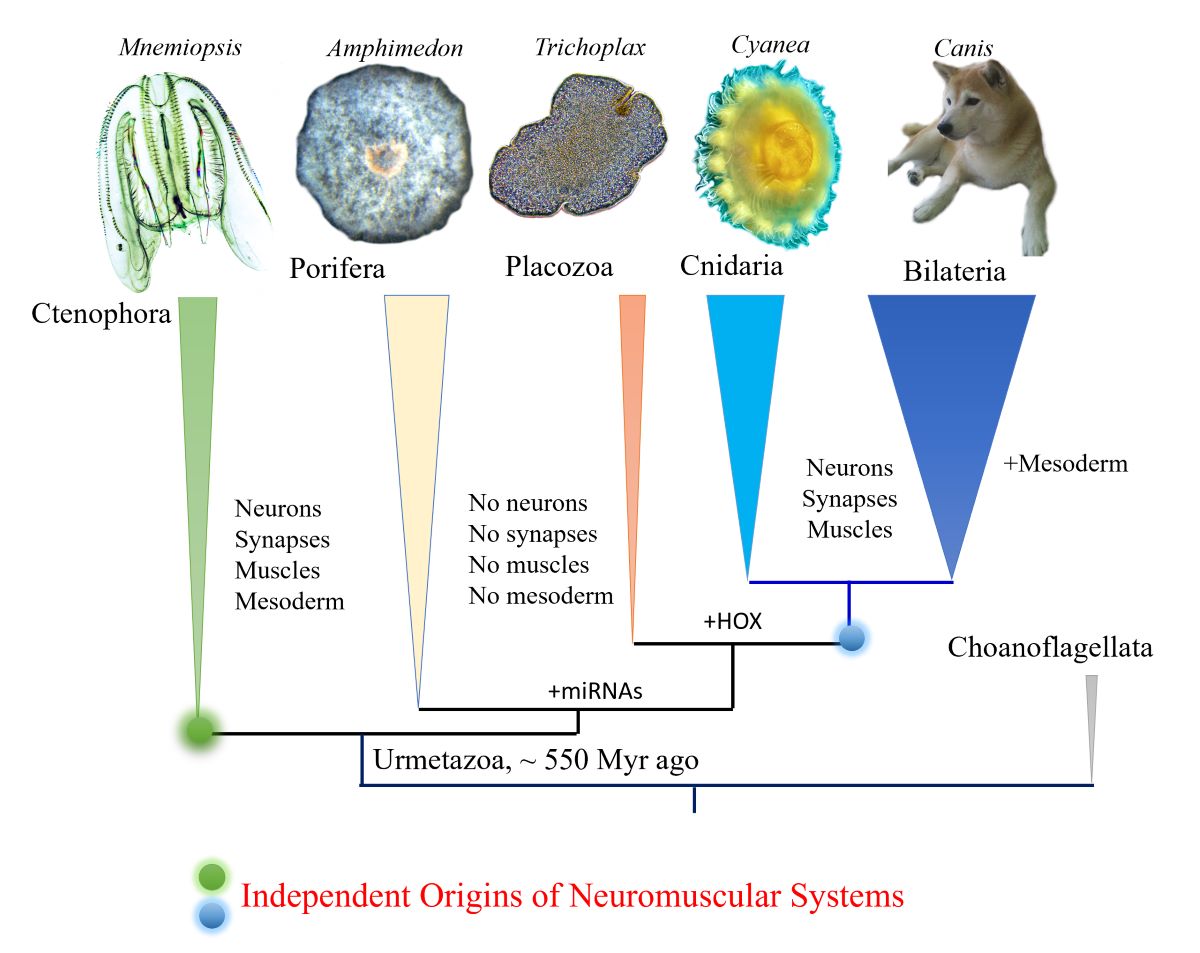

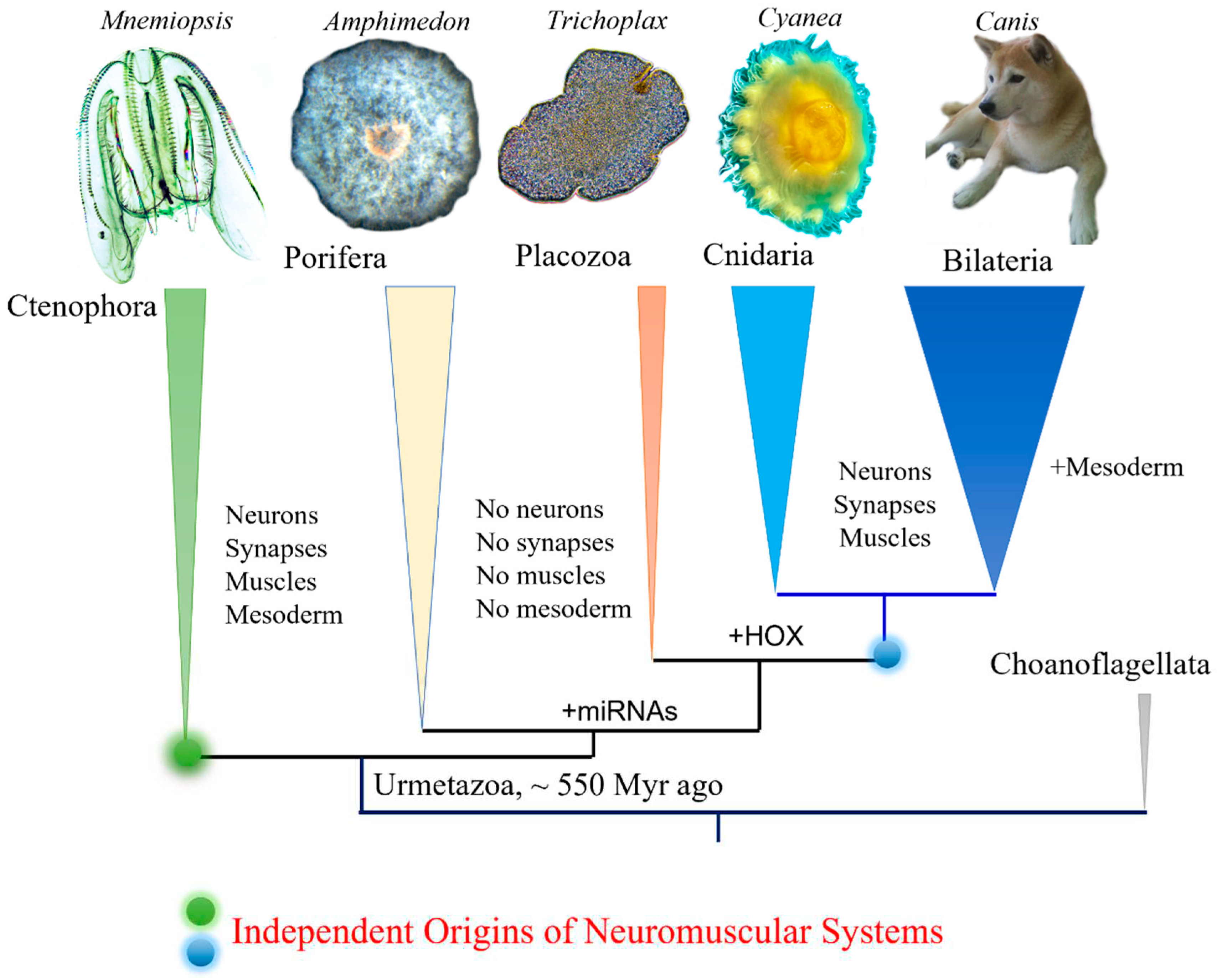

Ctenophores or comb jellies possess one of the most unique neural organizations of enigmatic origins; and there are no recognized homologies to any other phylum. The recent integrative

1 and comparative genomics

2-6, especially cross-phyla chromosome level synteny

7, analyses strongly confirmed a surprising hypothesis that morphologically and behaviorally complex ctenophores are descendants of the earliest metazoan branch, followed by simpler nerveless sponges (Porifera) and Placozoa (

Figure 1). Moreover, the molecular deciphering of neural toolkits in ctenophores reveals their unique molecular organization

8, including reduced representation of canonical bilaterian neurogenic and synaptic gene complement, distinct molecular profiling of ctenophore neurons as well as the apparent lack of classical low molecular weight transmitters

1,9. It is possible to state that ctenophores use remarkably different chemical language for intercellular communications with a unique (mostly unknown) subset of signal molecules as the hallmark of their neural architecture.

Specifically, both the complement of neurotransmitter synthetic enzymes and, most importantly, direct microchemical analyses of neurotransmitters themselves1,9 indicate that acetylcholine, serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, adrenaline, and histamine are not produced by ctenophores studied so far, including Pleurobrachia and Mnemiopsis1,10. Furthermore, initial pharmacological tests also failed to observe noticeable behavioral effects of these low molecular weight ‘classical’ transmitters1,11. Thus, we concluded that monoamines and acetylcholine are true bilaterian innovations10,12,13, later confirmed with the additional comparative survey of synthetic and metabolic enzymes14. Glutamate was initially proposed as a neuromuscular transmitter and a possible interneuronal transmitter in ctenophores1,8,9,15. In contrast, ctenophores (including Pleurobrachia and Mnemiopsis with two sequenced genomes at that time) developed several dozen small signaling peptides and neuropeptides, which have no detectable homologs outside Ctenophora1,10 (with two possible exceptions16).

The obtained interdisciplinary evidence leads to the conclusion that ctenophores independently developed neural systems1,17 and independently evolved synaptic organization10,13. Therefore, ctenophore neurons are not homologous to cnidarian and bilaterian neurons. Thus, we attempted to refine and broaden the definition of neurons and also used terms of alternative neural and integrative systems13,18. In other words, neurons are synaptically coupled polarized and highly heterogenous secretory cells at the top of behavioral hierarchies with learning capabilities; and we postulated that neurons are functional rather than genetic categories10.

In summary, ctenophore neurons result from convergent evolution with their very own array of chemical transmitters, including ctenophore-specific neuropeptides. Recent immunohistochemical and pharmacological experiments confirmed this hypothesis and showed specific distribution and behavioral effects of ctenophore-specific neurotransmitters in

Mnemiopsis19 and

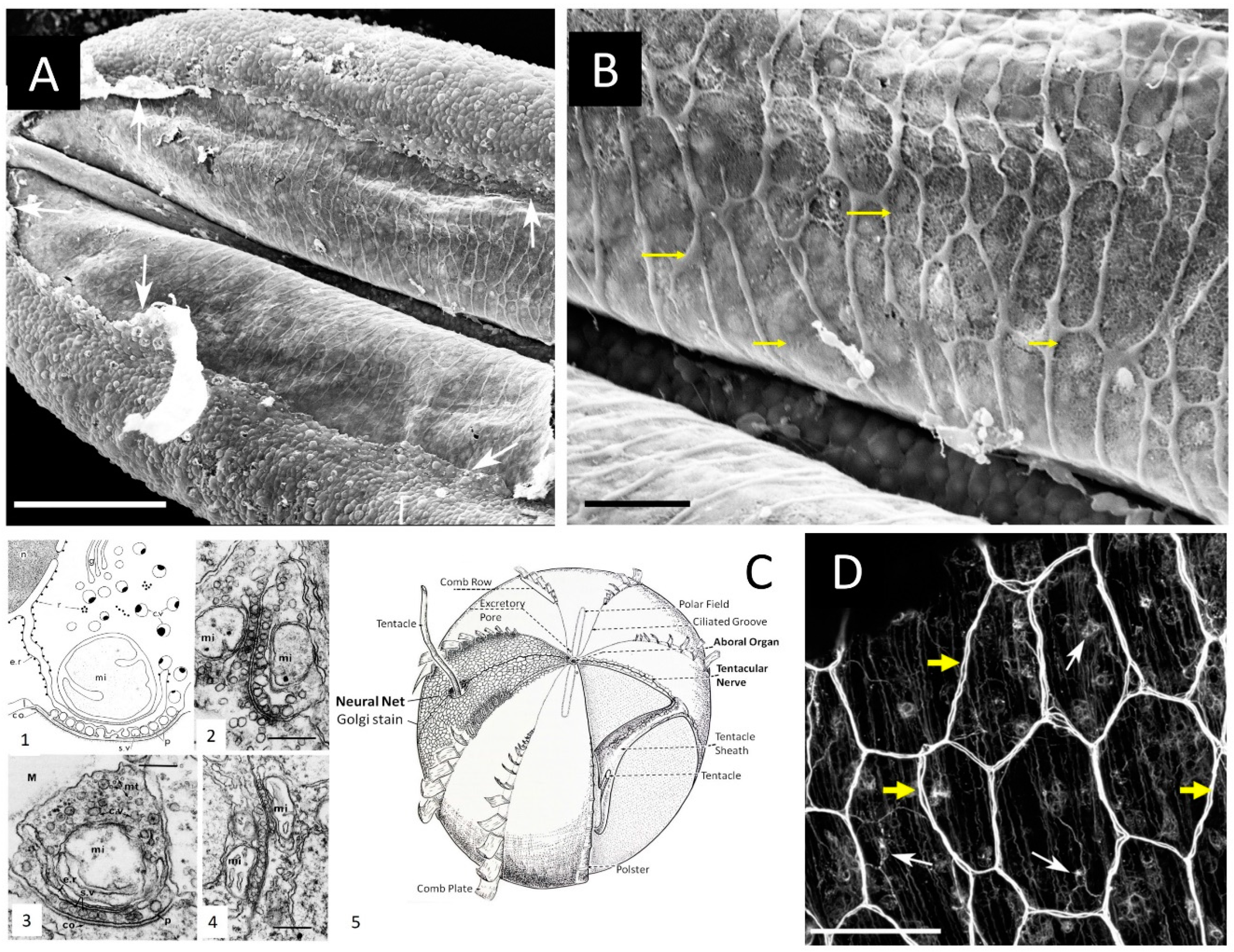

Bolinopsis20. The overall assessment was that ctenophores broadly used chemical (volume) and more localized synaptic signaling as the dominant way of interneuronal communications with more than 100 signaling molecules

13. Earlier transmission electron microscopy data identified unique chemical synapses across structures and species in ctenophores, as summarized by Mari Luz Hernandez-Nicaise

21, see also

Figure 2C.

Structural uniqueness of ctenophore neural systems

Recent and remarkable ultrastructural data with volume microscopy validate the uniqueness of neural systems and synapses in ctenophores19,22, further reinforcing our earlier hypothesis of their independent origins10. However, besides the canonical neural organization with distinct synapses, ctenophores likely possess syncytial-type connectivity in some neuronal populations, such as components of subepithelial nerve net and possibly in the gut22. This 3D electron microscopy reconstruction of neural nets highlighted an apparent ‘resurrection’ of the original Golgi’s reticular theory22. Furthermore, the initial perception of the novel volume microscopic data might be that non-[chemical]synaptic transmission is the distinct characteristic of ctenophore organization in general23,24, in contrast to other animals and the Cajal’s neuronal doctrine. Moreover, recent discussions and news releases might represent these ultrastructural data as evidence that all ctenophore neurons form the neuroid-type syncytium and have reduced chemical transmission across all neural circuits. Or this situation might be viewed as the predominance of syncytial organization for electrical propagation of signals vs. chemical transmitter-mediated signaling. Experimental functional exploration is needed to understand the cellular bases of ctenophore behaviors.

Toward this discussion, I think that ctenophore neural communications are primarily chemical, with deep ancestry of chemical signaling at the base of animal and neural organization. Here, I summarize this viewpoint and the prospects for future studies.

Chemical synapses and signaling in ctenophores vs. direct reticular coupling

The Neuron Doctrine postulated anatomical and functional identities of individual neurons as the foundation of any neural organization, stressing morphological and physiological discontinuity of neurons in central and peripheral neural systems. Nevertheless, in his vision of the Neuron Doctrine, Raymon y Cajal ‘wisely considered that “neuronal discontinuity… could sustain some exceptions”25,26. Coupling cells and neurites into functional syncytia might occur with and without electrical synapses. Ctenophores present an exceptional opportunity to readdress 130-year-old concepts of neuronal architectures.

There are three groups of questions. (i) How universal are ctenophore neural syncytia during development and across species? (ii) Is syncytial organization unique to ctenophore neurons? (iii) What are relationships between neuroid syncytia and chemical signaling with distinct secretory machinery in behavioral integrations of ctenophores? Interdisciplinary comparative studies would be needed to address these questions experimentally.

Burkhard and colleagues performed their remarkable 3D electron microscopy observations on small, just-hatching larval/juvenile animals of the lobate ctenophore, Mnemiopsis leidyi19,22, with developing neural systems consisting of a few dozen putative neurons 27. Whether or not the syncytial organization is preserved within a greater neuronal diversity in adult Mnemiopsis must be determined.

First, the neural syncytium within some ctenophore neural nets is possible and likely exists in other species, such as the cydippid

Pleurobrachia bachei (e.g.,

Figure 1c in Moroz et al. (2014)

1). For example, we did observe such architecture within the nerve net of tentacle pockets

28 of adult

Pleurobrachia (

Figure 2A,B), the species with an estimated ~10,000 individual neurons

28,29. Nevertheless, most subepithelial neural nets in

Pleurobrachia and more than ten other investigated species have neurons with two or more neurites within their orthogons (

Figure 2D, see details in

28-31, and in contrast to one neurite of studied microscopic

Mnemiopsis, suggesting that different types of communications are involved.

Second, although syncytial types of networks are relatively rare, neuroid-type syncytia, similar to these found in ctenophores, were observed in the representatives of at least six animal phyla. However, this list can be expanded since most ‘minor’ phyla remain unexplored. Syncytial-like neural nets might exist in the colonial polyp Velella32,33 (Cnidaria). In the cephalopod stellate ganglion, neuronal processes are fused to form giant axons34. Neuronal membrane fusion was also reported in gastropod molluscs, annelids (leeches), nematodes, and mammals35-37. Specifically, neurite and synaptic fusion occur during neural development and neuroplasticity in Drosophila38 (Arthropoda) and mammals39 (Chordata), likely contributing to metabolic coupling, fast propagating, axon and dendrite pruning, and integration of signaling.

Third, based on published data, only a limited fraction of ctenophore neurons make a syncytial nerve net22. In the recent reconstruction, only 5 of 33 studied neurons in the early stages of Mnemiopsis can form a syncytium with fused plasma membranes22. Still, these characterized neurons revealed diverse chemical synapses with characteristic ctenophore-specific presynaptic triads of organelles arranged in layers of synaptic vesicles, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondrion21,40.

Burkhard and colleagues did not report chemical synapses between subepithelial neurons; however, 3D reconstruction revealed chemical synapses from subepithelial neurons to multiple effector cells such as ciliated structures – polster cells in combs22. Furthermore, 4 of 5 studied populations of sensory neurons make morphologically recognized synapses to subepithelial and mesogleal neurons as well as among themselves and comb cells22, confirming the widespread distribution of chemical synapses within neural systems of Mnemiopsis.

It is worth noting that all ctenophore neurons and their neurites contained a diversity of secretory vesicles, suggesting recruitments of multiple neurotransmitters with possible co-localization of signal molecules within the same neuron. The presented ultramicroscopic images indicate about 60-70 sites with dense-core vesicles within a 2-3 neuronal soma diameter area22, suggesting that even this anastomosed subnet can be a neurosecretory system without identified gap junctions among subepithelial neurons. Indeed, the anastomosed neurites contain endogenous neuropeptides (e.g., ML02736a19) as possible secretory products of these nets.

Structural constraints of the discovered syncytial-like net are equally essential in understanding the directional propagation of neural signaling in ctenophores. Burkhard and colleagues visualized distinct “blebbed or ‘pearls-on-a-string’ morphology” of neurites in the subepithelial layer with a chain of secretory vesicles22. Of note, secretory vesicles are separated by extremely narrow (~50-60 nm) cytoplasmatic bridges, sufficient for few microtubules to pass through. A similar type of organization was also recently observed in some rodent axons41. How these vesicles are transported to these locations or maintained is unclear. How, for example, electrical signals can be propagated along these ultranarrow channels with apparently high resistance are unanswered questions. Saltatory electrical conduction combined with the volume release of neurosecretory molecules might occur. Unfortunately, the majority of signal molecules are unknown in the ctenophore lineage. The current subset of transmitters includes (i) L-/D Glutamate1,9 and (ii) glycine as a potential agonist of some ionotropic glutamate receptors in ctenophores42,43, (iii) gaseous nitric oxide (NO)44, plus (iv) several ctenophore-specific neuropeptides1,19,20, and possibly some catecholamines45. Many surprises are expected with apparently alternative chemical “syntax” and even the chemical “alphabet” of signaling molecules in this still very enigmatic lineage of basal metazoans.

Conclusion

Ctenophore nets are structurally and molecularly unique compared to other metazoans. The syncytial-type organization occurs in neural nets within the subepithelium, the gut of Mnemiopsis 22, and the Pleurobrachia tentacle pocket 28. These ultrastructural data provide additional support for the convergent nature of ctenophore neurons 1,10.

Unique tripartite synapses, unique molecular neural and synaptic toolkits, unique expression of transcription factors, and diversity of unique ctenophore-specific neuropeptides, plus deficiency of bilaterian+cnidarian low molecular weight transmitters, are arguments for the hypothesis of independent origins of ctenophore neural systems, as proposed earlier 1,17,46,47.

Whether the syncytial organization of some ctenophore larval neurons is a primarily or secondary traits remains to be determined by ongoing comparative analyses of other ctenophore species. More likely, neuroid syncytia are evolutionarily derived events and relatively rare specializations for particular functions, as evident from other fused neurons in some cnidarians and bilaterians.

The directionality of neuronal signaling in ctenophores is evident from the behaviors of these animals as ambush or active predators. Existing information favors the predominance of chemical signaling in ctenophores and its essential role in neuronal integration and behavioral control. For example, suppression of synaptic transmission in high magnesium solutions eliminated the coordinated activity of cilia in intact and semi-intact ctenophore preparations11.

The emerging peptidergic nature of the ctenophore neural systems1,19,20 is consistent with the hypothesis that neurons evolved from secretory cells17,46,47. Moreover, the astonishing diversity and higher information capacity of classical synapses and volume transmission indicate that chemical signaling is the hallmark of neural and other integrative systems regardless of their origins13,18,27. Cajal’s neuronal doctrine applies to ctenophores in full and “...could sustain some exceptions”25,26 as secondary specializations.

Finally, in addition to neuronal systems, the ctenophore evolved several parallel electrical conductive systems in the ciliated furrows via gap junctions formed by at least 12 innexins21,30,48-54. We might also expect the presence of alternative integrative (electrical and chemical) systems in this still enigmatic group of early-branching metazoans.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (IOS-1557923) and, in part, by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01NS114491. The content is solely the author's responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Moroz, L. L. et al. The ctenophore genome and the evolutionary origins of neural systems. Nature 510, 109-114. (2014) . [CrossRef]

- Whelan, N. V., Kocot, K. M., Moroz, L. L. & Halanych, K. M. Error, signal, and the placement of Ctenophora sister to all other animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 5773-5778. (2015) . [CrossRef]

- Whelan, N. V. et al. Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 1737-1746. (2017) . [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Shen, X. X., Evans, B., Dunn, C. W. & Rokas, A. Rooting the Animal Tree of Life. Mol Biol Evol 38, 4322-4333. (2021) . [CrossRef]

- Whelan, N. V. & Halanych, K. M. Available data do not rule out Ctenophora as the sister group to all other Metazoa. Nat Commun 14, 711. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. F. et al. The genome of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and its implications for cell type evolution. Science 342, 1242592. (2013) . [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D. T. et al. Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals. Nature 618, 110-117. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L. Convergent evolution of neural systems in ctenophores. J Exp Biol 218, 598-611. (2015) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L., Sohn, D., Romanova, D. Y. & Kohn, A. B. Microchemical identification of enantiomers in early-branching animals: Lineage-specific diversification in the usage of D-glutamate and D-aspartate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 527, 947-952. (2020) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L. & Kohn, A. B. Independent origins of neurons and synapses: insights from ctenophores. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371, 20150041. (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Norekian, T. P. & Moroz, L. L. Recording cilia activity in ctenophores: effects of nitric oxide and low molecular weight transmitters. Front Neurosci 17, 1125476. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L. & Kohn, A. B. Unbiased View of Synaptic and Neuronal Gene Complement in Ctenophores: Are There Pan-neuronal and Pan-synaptic Genes across Metazoa? Integr Comp Biol 55, 1028-1049. (2015) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L., Romanova, D. Y. & Kohn, A. B. Neural versus alternative integrative systems: molecular insights into origins of neurotransmitters. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 376, 20190762. (2021) . [CrossRef]

- Goulty, M., Botton-Amiot, G., Rosato, E., Sprecher, S. G. & Feuda, R. The monoaminergic system is a bilaterian innovation. Nature Communications 14, 3284. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L., Nikitin, M. A., Policar, P. G., Kohn, A. B. & Romanova, D. Y. Evolution of glutamatergic signaling and synapses. Neuropharmacology 199, 108740. (2021) . [CrossRef]

- Yañez-Guerra, L. A., Thiel, D. & Jékely, G. Premetazoan origin of neuropeptide signaling. Molecular Biology and Evolution 39, msac051 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L. The genealogy of genealogy of neurons. Commun Integr Biol 7, e993269. (2014) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L. & Romanova, D. Y. Alternative neural systems: What is a neuron? (Ctenophores, sponges and placozoans). Front Cell Dev Biol 10, 1071961. (2022) . [CrossRef]

- Sachkova, M. Y. et al. Neuropeptide repertoire and 3D anatomy of the ctenophore nervous system. Curr Biol 31, 5274-5285 e5276. (2021) . [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, E. et al. Mass spectrometry of short peptides reveals common features of metazoan peptidergic neurons. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 1438-1448. (2022) . [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Nicaise, M.-L. in Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates: Placozoa, Porifera, Cnidaria, and Ctenophora Vol. 2 (eds F. W. F.W. Harrison & J. A. Westfall) 359-418 (Wiley, 1991).

- Burkhardt, P. et al. Syncytial nerve net in a ctenophore adds insights on the evolution of nervous systems. Science 380, 293-297. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C. Neurons that connect without synapses. Science 380, 241-242. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Lenharo, M. Comb jellies' unique fused neurons challenge evolution ideas. Nature. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Cajal, S. R. y. Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates, N. Swanson, L.W. Swanson, Trans., (Oxford Univ. Press, 1995).

- Bullock, T. H. et al. Neuroscience. The neuron doctrine, redux. Science 310, 791-793. (2005) . [CrossRef]

- Norekian, T. P. & Moroz, L. L. Development of the nervous system in the early hatching larvae of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. J Morphol 282, 1466-1477. (2021) . [CrossRef]

- Norekian, T. P. & Moroz, L. L. Neuromuscular organization of the Ctenophore Pleurobrachia bachei. J Comp Neurol 527, 406-436. (2019) . [CrossRef]

- Norekian, T. P. & Moroz, L. L. Development of neuromuscular organization in the ctenophore Pleurobrachia bachei. J Comp Neurol 524, 136-151. (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Norekian, T. P. & Moroz, L. L. Comparative neuroanatomy of ctenophores: Neural and muscular systems in Euplokamis dunlapae and related species. J Comp Neurol 528, 481-501. (2020) . [CrossRef]

- Norekian, T. P. & Moroz, L. L. Neural system and receptor diversity in the ctenophore Beroe abyssicola. J Comp Neurol 527, 1986-2008. (2019) . [CrossRef]

- Mackie, G. O. The structure of the nervous system in Velella. J. Cell Sci. s3-101, 119-131 (1960). [CrossRef]

- Mackie, G. O., Singla, C. L. & Arkett, S. A. On the nervous system of Velella (Hydrozoa: Chondrophora). J. Morphol. 198, 15-23 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Young, Z. Y. Fused neurons and synaptic contacts in the giant nerve fibres of cephalopods. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 229, 465-503 (1939).

- Giordano-Santini, R., Linton, C. & Hilliard, M. A. Cell-cell fusion in the nervous system: Alternative mechanisms of development, injury, and repair. Semin Cell Dev Biol 60, 146-154. (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Giordano-Santini, R. et al. Fusogen-mediated neuron-neuron fusion disrupts neural circuit connectivity and alters animal behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 23054-23065. (2020) . [CrossRef]

- Oren-Suissa, M., Hall, D. H., Treinin, M., Shemer, G. & Podbilewicz, B. The fusogen EFF-1 controls sculpting of mechanosensory dendrites. Science 328, 1285-1288. (2010) . [CrossRef]

- Yu, F. & Schuldiner, O. Axon and dendrite pruning in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol 27, 192-198. (2014) . [CrossRef]

- Faust, T. E., Gunner, G. & Schafer, D. P. Mechanisms governing activity-dependent synaptic pruning in the developing mammalian CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci 22, 657-673. (2021) . [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Nicaise, M. L. The nervous system of ctenophores. III. Ultrastructure of synapses. J Neurocytol 2, 249-263. (1973) . [CrossRef]

- Griswold, J. M. et al. Membrane mechanics dictate axonal morphology and function. bioRxiv, 2023.2007.2020.549958. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Alberstein, R., Grey, R., Zimmet, A., Simmons, D. K. & Mayer, M. L. Glycine activated ion channel subunits encoded by ctenophore glutamate receptor genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, E6048-6057. (2015) . [CrossRef]

- Yu, A. et al. Molecular lock regulates binding of glycine to a primitive NMDA receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E6786-E6795. (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L., Mukherjee, K. & Romanova, D. Y. Nitric oxide signaling in ctenophores. Front Neurosci 17, 1125433. (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Townsend, J. P. & Sweeney, A. M. Catecholic Compounds in Ctenophore Colloblast and Nerve Net Proteins Suggest a Structural Role for DOPA-Like Molecules in an Early-Diverging Animal Lineage. Biol Bull 236, 55-65. (2019) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L. On the independent origins of complex brains and neurons. Brain Behav Evol 74, 177-190. (2009) . [CrossRef]

- Moroz, L. L. Multiple Origins of Neurons From Secretory Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 669087. (2021) . [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Nicaise, M. L. Specialized connexions between nerve cells and mesenchymal cells in ctenophores. Nature 217, 1075-1076. (1968) . [CrossRef]

- Tamm, S. L. Cilia and the life of ctenophores. Invertebrate Biology 133, 1-46 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Tamm, S. L. & Tamm, S. Novel bridge of axon-like processes of epithelial cells in the aboral sense organ of ctenophores. J Morphol 254, 99-120. (2002) . [CrossRef]

- Tamm, S. L. & Moss, A. G. Unilateral ciliary reversal and motor responses during prey capture by the ctenophore Pleurobrachia. J Exp Biol 114, 443-461 (1985). [CrossRef]

- Tamm, S. L. Mechanical synchronization of ciliary beating within comb plates of ctenophores. J Exp Biol 113, 401-408 (1984). [CrossRef]

- Tamm, S. L. in Electrical conduction and behavior in "simple" invertebrates 266-358 (Clarendon Press, 1982).

- Tamm, S. Mechanisms of cilliary co-ordinations in ctenophores. Journal of Experimental Biology 59, 231-245 (1973).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).