Submitted:

11 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Utilizing the discrete ripplet-II transform (DR2T) for feature extraction offers benefits by effectively capturing two-dimensional irregularities and a group of curves in fundus images.

- The golden jackal optimization (GJO) aimed to select the most essential elements from the range of potential solutions, with the goal of eliminating redundant and irrivalant features and LS-SVM (GJO+LS-SVM) to classify better classification accuracy.

- The LS-SVM acts as the classifier and provides a higher level of computational efficiency compared to the conventional SVM.

- Comparison with alternative capable techniques based on classification accuracy and quantity of attributes using three widely recognized datasets.

- The remainder of this article is organised as follows: In Section 2 provides a summary of the literature regarding glaucoma detection. Section 3 provides a comprehensive explanation of our approach, encompassing the suggested methodology. Section 4 explored the experimental discoveries and evaluated the outcomes. This Section 5 highlights the summarization of the research’s results and delineates possible directions for future research.

2. Related works

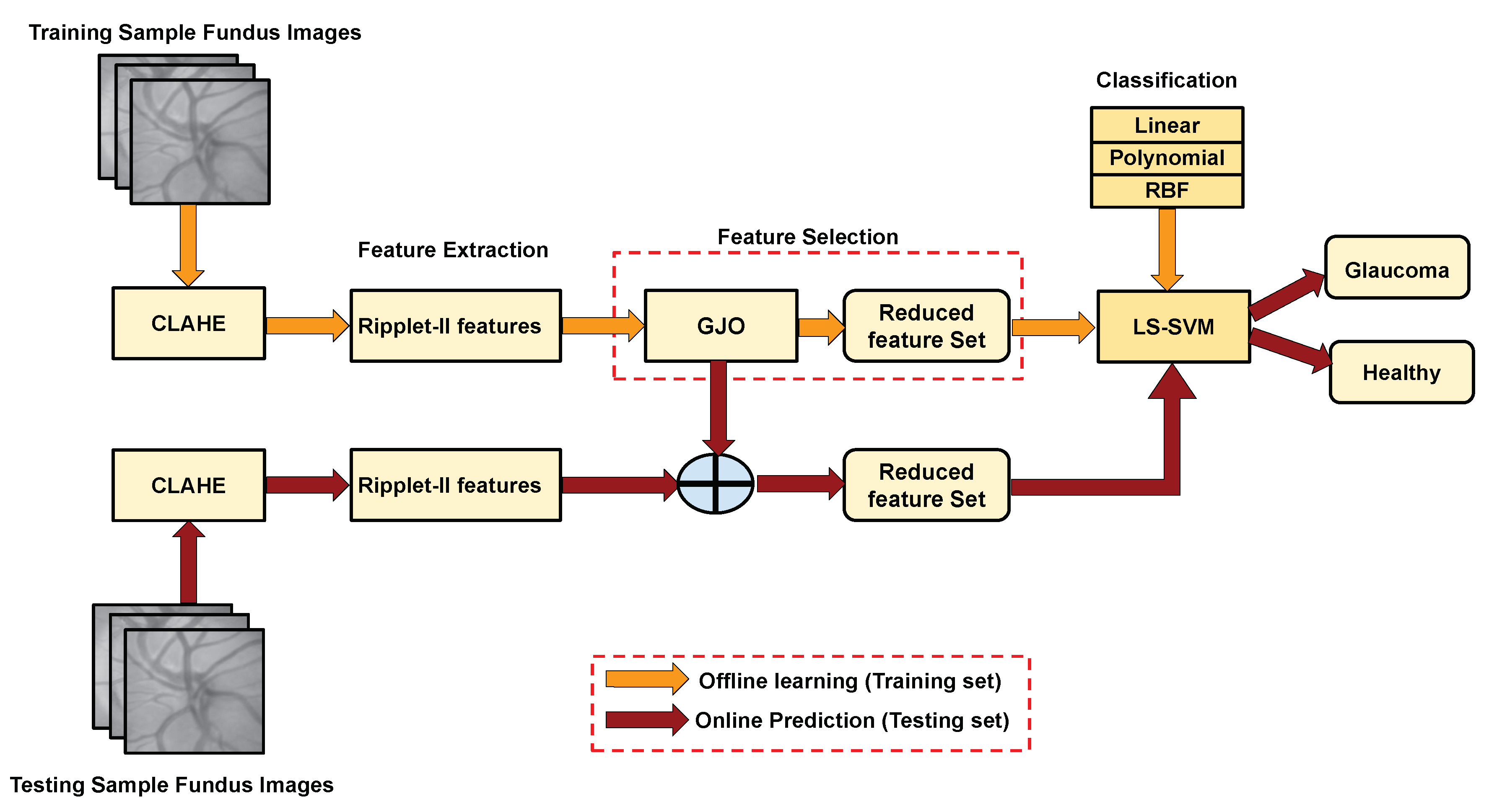

3. Proposed methodology

3.1. Preprocessing

3.1.1. Prepocessing based on CLAHE method

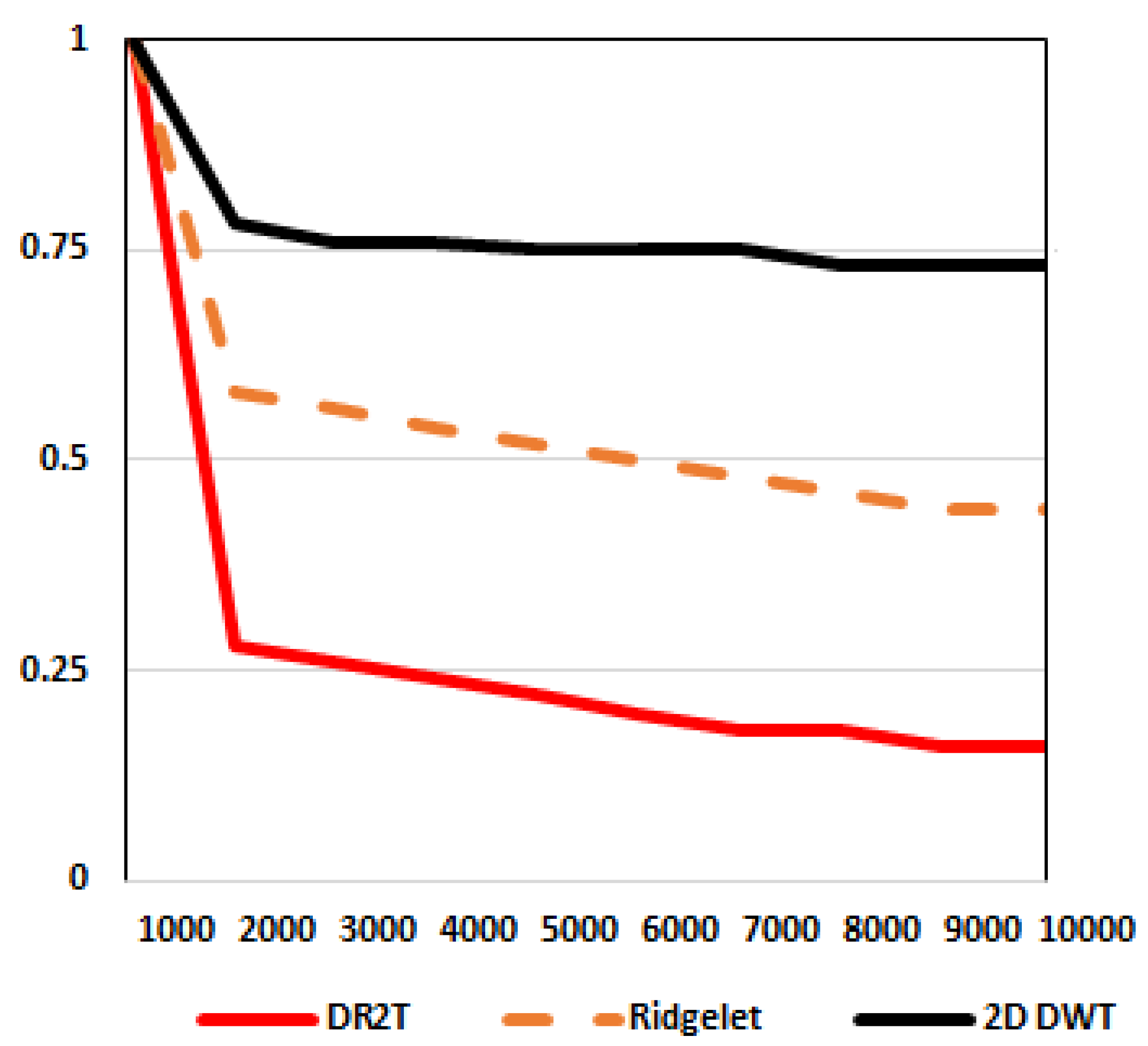

3.2. Feature extracton using discrete ripple-II transform (DR2T)

3.2.1. Ripplet-II transform

- Convert the input function from Cartesian coordinates to polar coordinates, which is to . Update by in . Hence, construct a new image by interpolation after converting polar coordinates to Cartesian cordinates(x,y). Here, the variables x and y store integer values.

- deployed discrete CRT on that generates and then substitue with in as in Equation 7. then obtain the DGRT coofficients .

- Consider 1D-DWT to DGRT coefficients w.r.t and obtain the discrete ripplet-II coefficients.

3.2.2. Feature generation using DR2T

| Algorithm 1:Feature extraction based on discrete ripplet-II tansform |

|

3.3. Feature Selection using meta-heuristic optimization techniques

3.3.1. Golden Jackal Optimization Algorithm

- Finding the target and moving closer to it.

- Catching the quarry and provoking it.

- Hunting down and capturing the prey.

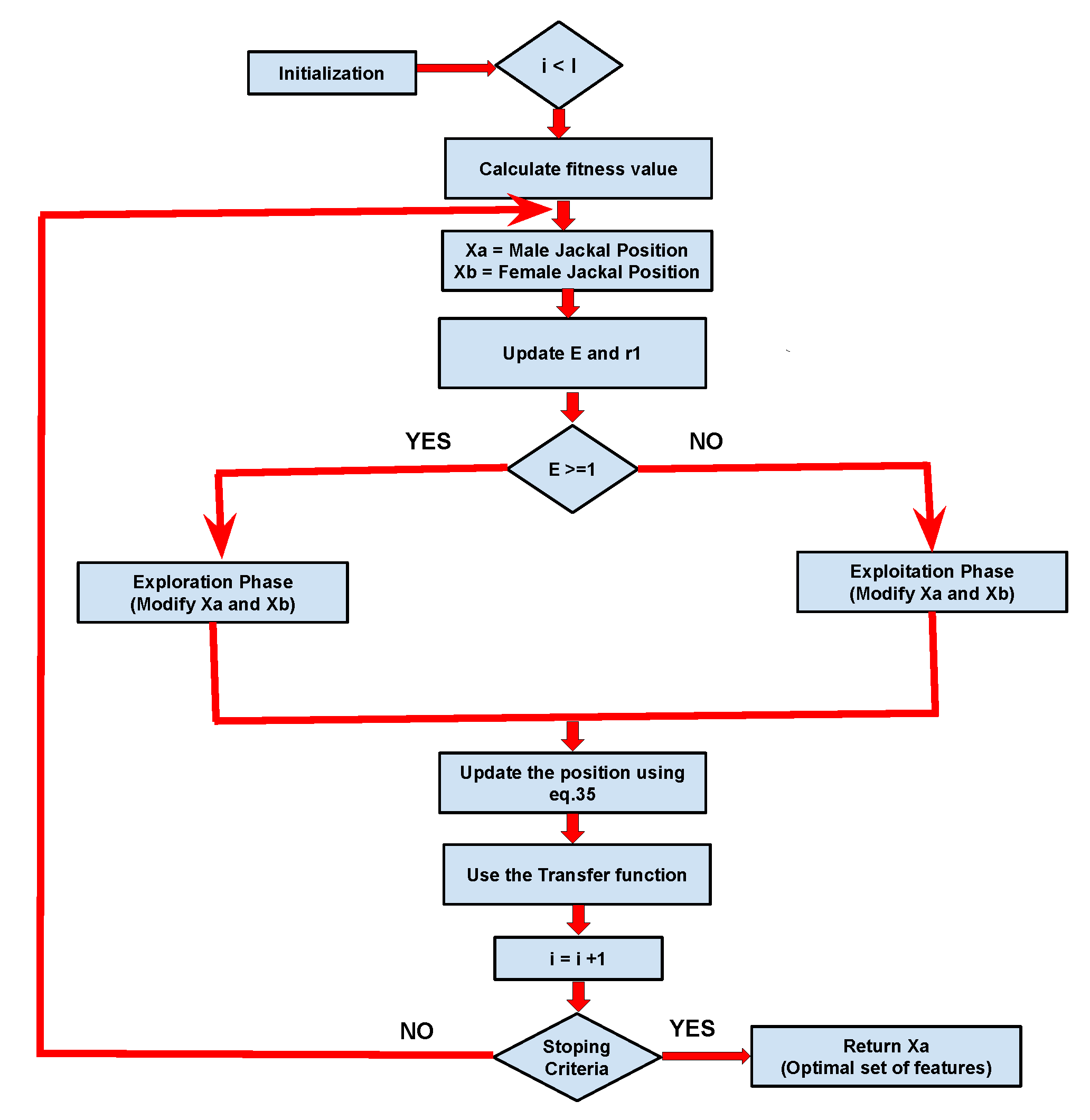

3.3.2. Feature selection using golden jackal optimization algorithm (GJO)

- Initialization: GJO employs a population-centric strategy, much like several other metaheuristic techniques, wherein it uniformly explores the search space, commencing from starting phase. The starting result specified in Equation 23, In this context, represents the minimum limit, signifies the maximum limit, and ’rand()’ is a method that produces values within the range of 0 to 1.Suppose we have ’p’ possible prey items and ’q’ variables that each individual can exhibit, as outlined in the Equation 24. In this context, ’i’ ranges from 1 to ’p’, with each ’i’ representing the position of a single prey’s. Consequently, the prey groups can be represented based on ’p × q’ vector denoted by , as described, Equation 25. Here, ’i’ takes values , and , with each row representing an individual prey, and each column representing a specific variable or dimension. symbolizes the initial prey matrix established during initialization, comprising the two healthiest individuals, one male, and one female jackal.Utilizing an optimization approach involving a set of p prey entities and q variables, the position of each prey entity unveils the characteristics of a particular solution. A performance evaluation function, also referred to as a fitness function, it is used to evaluate the effectiveness of each potential solution during the optimization process. The outcomes of this function for all conceivable solutions have been recorded in a matrix, as illustrated in Equation 26. In this equation, the variable ’i’ ranges from 1 to ’p’ and ’j’ from 1 to ’q’. We capture the performance metrics for each prey in a matrix denoted as . The optimization procedure includes ’p’ prey individuals, and their performance is evaluated using the designated objective function denoted as . The male and female jackals are considered to be the most and second-most adept prey individuals, respectively, often referred to as male jackal and female jackal prey positions.

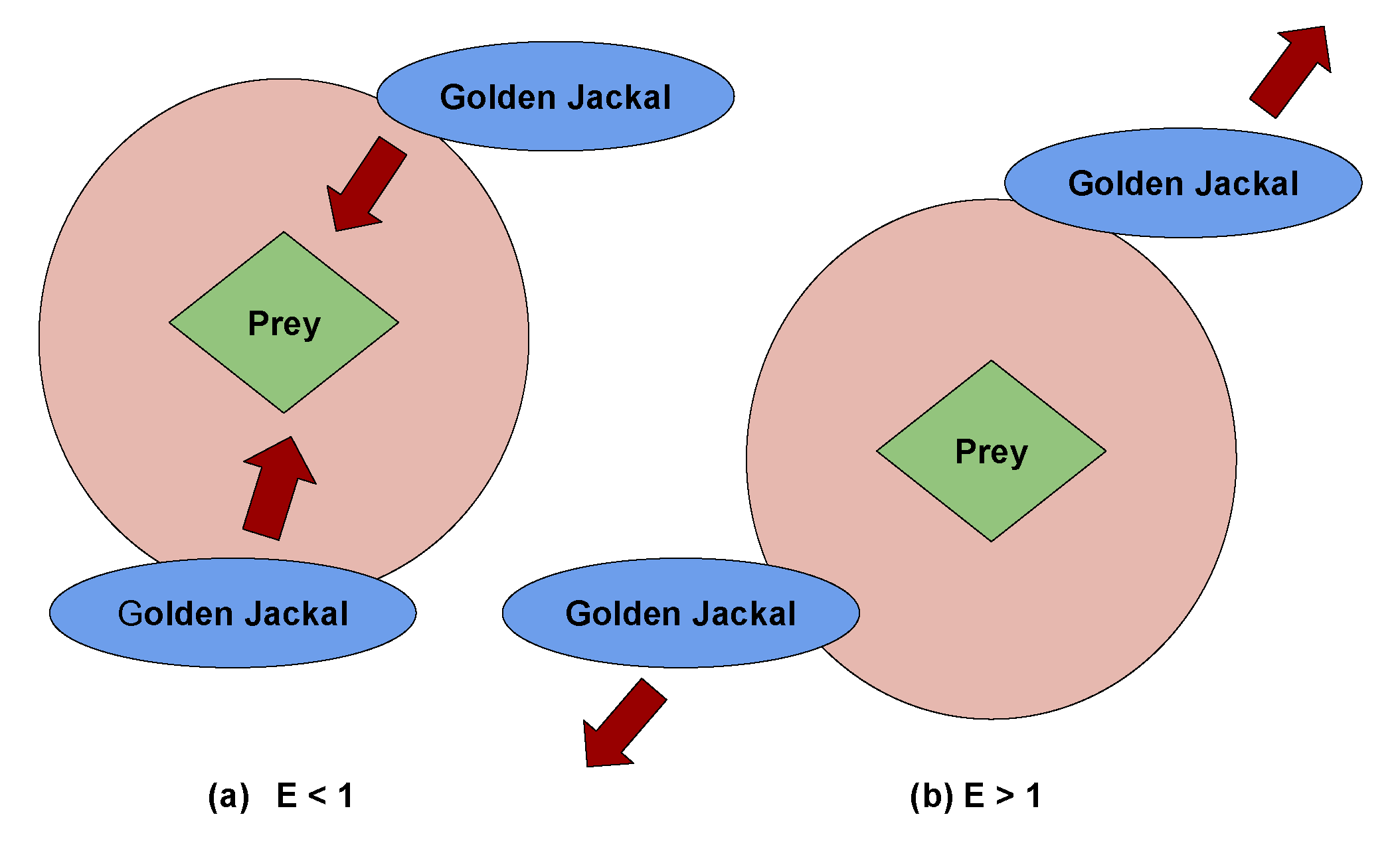

- Exploration Phase: In golden jackal optimization (GJO) method, exploration has achieved based on simulating the actions of a group of golden jackals as they forage for food in an unknown environment. Every jackal, representing a potential result, undergoes random movement based on specified limit to enhance the search area which random movement strategy prevents the algorithm from getting stuck in local optimal solutions and promotes the discovery of novel solutions. Occasionally, the prey may elude capture, but jackals are naturally adept at sensing and tracking it. Consequently, when the prey proves elusive, the jackals explore to seek out alternative destinations. Throughout the hunt, the male jackal assumes the lead position, with the female jackal following closely behind. Equations 27 and 28 outline the process of updating the male jackal’s position in this pursuit.In this scenario, ’Xprey’ signifies the vector indicating the prey’s location, "" represents the male jackal’s location, while "" signifies the female jackal’s position. The instaces ’i’ denotes the recent iteration, while ’’ represents as updated location based on male jackal ’’. ’’ specified as the position adjusted relative to the prey based on the jackal belongs to female groups ’’. For compute the prey’s evasion energy, referred to as ’Ep,’ Equation 29 is applied. Within this equation, ’Ep0’ specified as the current energy of the prey, while ’’ represents as reduction in its energy level.Here, is determined by applying Equation 30, and is computed using Equation 31. In these equations, we utilize the variable ’r,’ a randomly generated number falling within the range of 0 to 1, along with a fix value specifed as ’c1,’ set to 1.5. Furthermore, We introduce the variables ’I’ to denote throughout the iterations and ’i’ to represent the ongoing iteration count. The variable specified as decreasing energy of the prey labeled as ’.’ Its value gradually decreases based on 1.5 to 0, Indicating the gradual decrease in the prey’s vitality.Equations 27 and 28 serve to calculate the jackal’s distance based on prey, specified on . Based on jackal’s positional adjustments are influenced by the prey’s energy level, causing it to shift its position upwards or downwards depending on the proximity based on prey. By using vector s1, which is used in Equations 27, 28 respectively, the sequence of unique values adheres to the Levy distribution, which is a distinct probability distribution. This probability distribution is employed to replicate Levy-type motion and is utilized to model the movement of the prey vector, resembling Levy motion patterns. The procedure for computing ’s1’ is detailed in the subsequent equation 32.The Levy Flight method, represented as LF, is a computational formula used to model stochastic movements within a defined search area. It finds common application in optimization algorithms, serving the same purpose in this particular scenario. The process involves creating random numbers that follow the Levy distribution and utilizing them to alter the position of the search agent. The Levy distribution is a probability distribution recognized for its pronounced tails, enabling occasional substantial movements. It’s quality proves advantageous in optimization assignments since it empowers search agents to venture into far-flung areas within the search space, which would be challenging to access through minor, gradual adjustments. The LF can be calculated by applying Equation 33, where ’u’ and ’v’ are sampled from a normal distribution with standard deviations ’’ and ’u’ respectively. In this context, ’u’ is represented as a normal distribution characterized by a mean of and a variance of . On the other hand, ’v’ follows a normal distribution with a mean of derived from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance , and it also has a variance of v obtained from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance . whre, and The value of is determined on Equation 34.In Equation 35 specified as current position based on jackals’ based on male and female specifications, considering as the mean values derived from Equations 27 and 28.

- Exploitation Phase: This phase replicates how a dominant male golden jackal leads a pack in hunting, gradually wearing down the prey until a male and female jackal duo can encircle it, leading to a swift capture. This collaborative hunting behavior is mathematically shown in Equations 36, 37, with ’i’ denoting the current iteration. ’’ represents the male jackal’s updated position, while ’’indicates the altered positions of the female jackal in relation to the prey. To determine the prey’s elusive vitality, labelled as ’,’ we apply Equation 29, and subsequently, Equation 35 is employed to reposition the jackals. In the exploitation phase, the utilization of ’s1’ is integrated into Equations 36 and 37 in order to enhance exploration, reduce the likelihood of becoming trapped in local optimal solutions, and tackle issues similar to those encountered in actual hunting scenarios ’s1’ assists the jackals in converging toward the prey, particularly in later iterations.

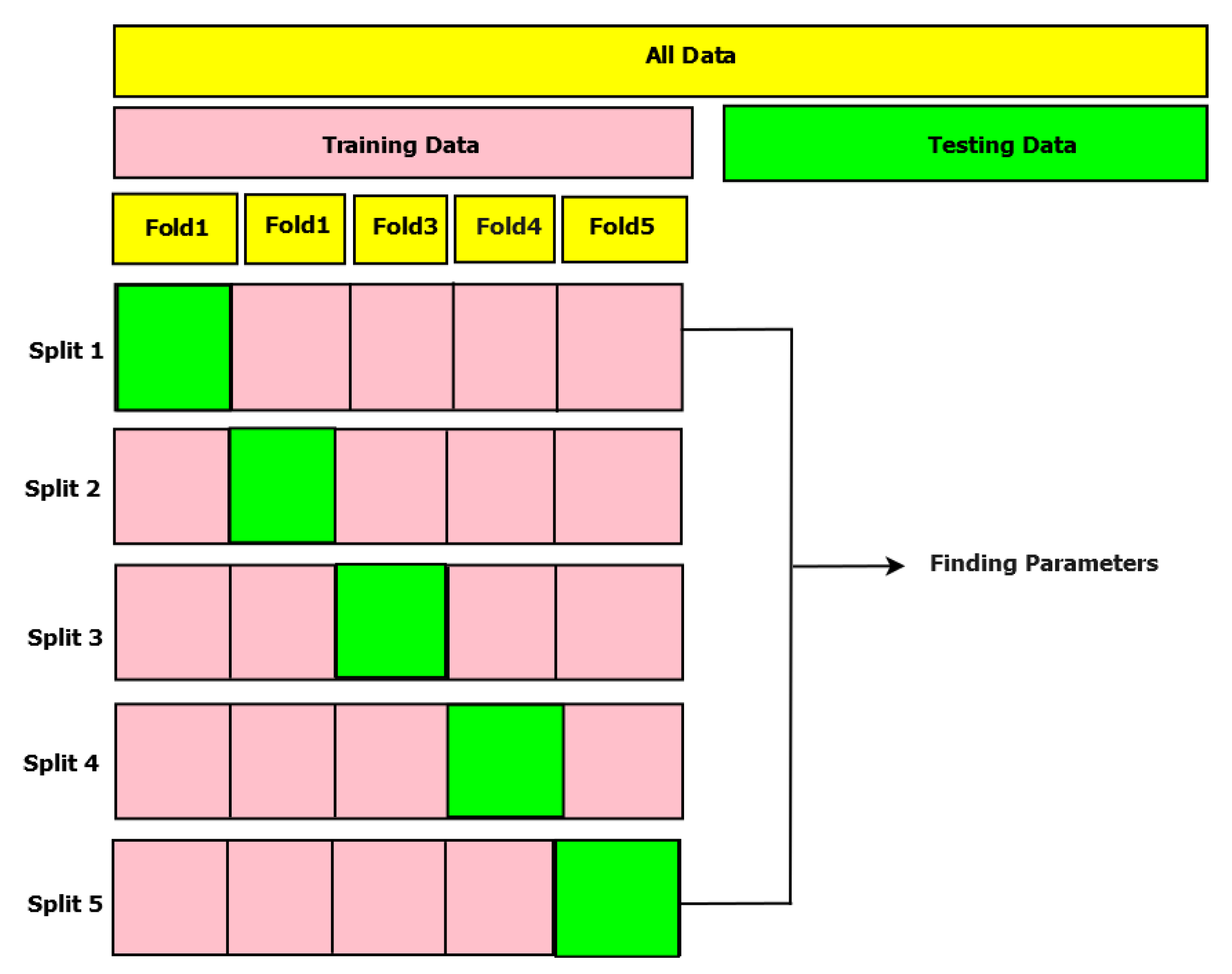

- During fitness calculation and adjustments, the position matrix is converted from continuous values to binary values through the use of a transfer function. In this particular research, a sigmoid transfer function has been presented on Equation 38. The rationale behind selecting this sigmoid transfer function is its ability. To optimize the algorithm’s search efficiency and avoid premature convergence, it is important to transition smoothly from real-number positions to binary values.In this equation, ’X’ stands for the initial position value within the initial matrix, labeled as ’, prior to its transformation into a binary format. The sigmoid function is employed to convert the continuous input ’X’ into a span that ranges from 0 to 1, which allows for the determination of the appropriate binary representation. This conversion ensures that the position values are in binary format, making it easier to use them in the computation of the prey’s fitness. Here, ’fitness’ pertains as assessing a machine learning (ML) classifier’s predictive accuracy. This evaluation involves comparing the classifier’s actual output to its predicted output. The dataset has been splited into traning and testing set with ratio 60:40. The 40% of the dataset is using for testing and rest 60% for training set . The ’fitness’ is determined by utilizing Equation 39, where ’k’ spans from 1 to ’m’, where ’m’ represents the quantity of testing observations, and ’’ represents the prediction error for the ’’ observation. The ultimate outcome is obtained by aggregating these errors and subsequently dividing by ’m’ to produce the mean prediction error.The algorithm makes use of two variables, MaleJackalscore and FemaleJackalscore, which represent the fitness scores of the best-performing male and female jackals that were identified as part of the optimization process. Here, the ’fitness’ specified as fitness value, while MaleJackalscore and FemaleJackalscore serve as the updated fitness values. In this context, if the fitness level of a jackal, denoted as f, is less than the present MaleJackalscore, it indicates that the jackal possesses higher fitness than the current top male jackal. As a result, he position and performance of this jackal will replace those of the current male jackal. On the other hand, if a jackal’s health is superior to MaleJackalscore but inferior to FemaleJackalscore, It implies a higher level of fitness than the current leading female jackal but falls short of matching the fitness of the male jackal. In these instances, the current position and performance of the female jackal will be replaced by those of the new female jackal. After the fitness assessment, the resulting fitness will be expressed according to the Equation 40, with the fitness array labelled as ’,’ comprising p elements, namely , , , and so forth, up to .Each algorithm step assigns a random value ranging from -1 to 1 to the initial energy, . represents the physical strength of the prey, and a decrease between 0 and -1 signifies a decline in the prey’s energy. On the other hand, an increase between 0 to 1 implies an improvement based on prey’s vitality, while declined based on becomes evident as the circular manner unfolds, which depicted in Figure 3. When absolute of magnitude that exceeds to 1, it signifies that the pairs of jackals are exploring various territories in search of prey, indicating that the algorithm is currently in an exploratory stage. Conversely, here, absolute magnitude based on is less than 1, the Algorithm shifts into an exploitation stage, initiating predatory actions on the prey according to the Algorithm 2.

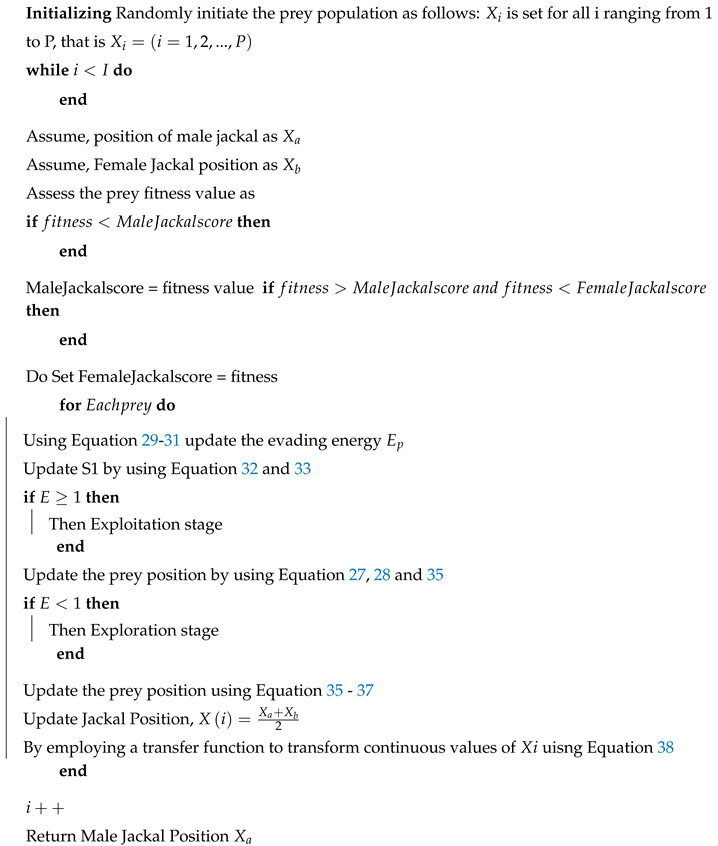

| Algorithm 2: The deployed GJO method for Algorithm |

|

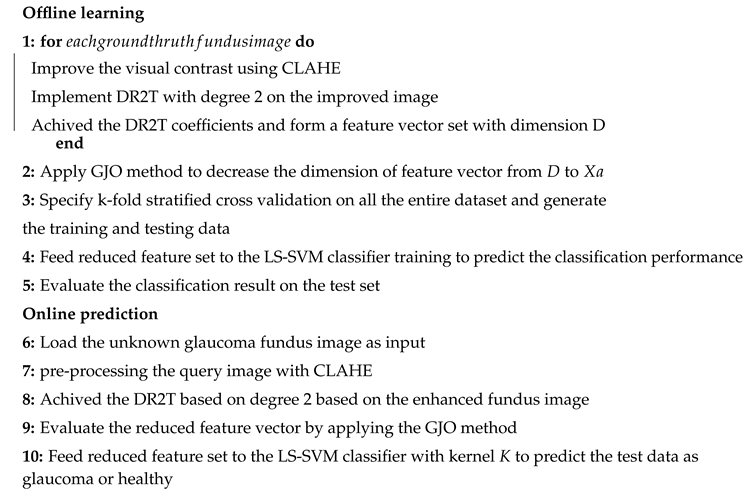

| Algorithm 3:Pseudocode of the proposed system |

|

3.4. Classification using LS-SVM

| Kernel | Defination |

|---|---|

| Linear | |

| Polynomial | |

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) |

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Population size | 30 |

| Maximum iteration | 200 |

| r (Random integer) | 0 to 1 |

| c1(Constant value), | 1.5 |

| Algorithms | Specifications | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost [41] | Learning rate | 0.3 |

| n-estimators | 100 | |

| Scale-pos-wirght | 1 | |

| Random Forest [8] | n-estimators | 100 |

| Criterion | Gini | |

| Min-impurity-decrease | 0 | |

| Number of folds | 5 | |

| Decision Tree [42] | Criterion | Gini |

| Max-features | 0,1 | |

| Min-sample-leaf | 1 | |

| Min-sample-split | 2 | |

| KNN [5] | Nearest neighbors(K) | 1 |

| Nearset neighbor search algorithm | Euclidean distance | |

| List of folds | 5 | |

| BPNN[5] | Learning rate, momentum | 0.001, 0.4 |

| Hidden neurons | 6 | |

| List of folds | 5 | |

| LS-SVM Linear[45] | Dimension space | -1, +1 |

| Kernel type | Linear | |

| List of folds | 5 | |

| LS-SVM Polynomial [45] | Order | 2 |

| Kernel type | Poly | |

| List of folds | 5 | |

| LS-SVM RBF [45] | , | [1-10] |

| Kernel type | RBF | |

| List of folds | 5 |

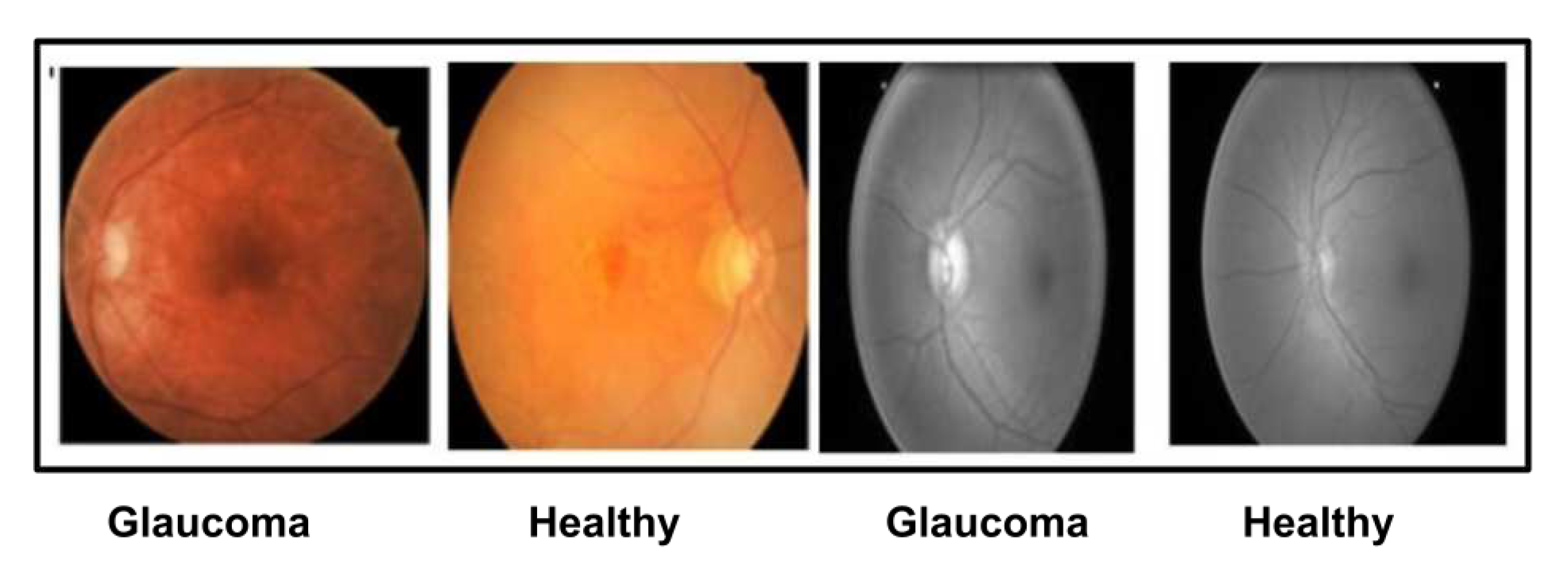

4.1. Preprocessing and feature extraction results

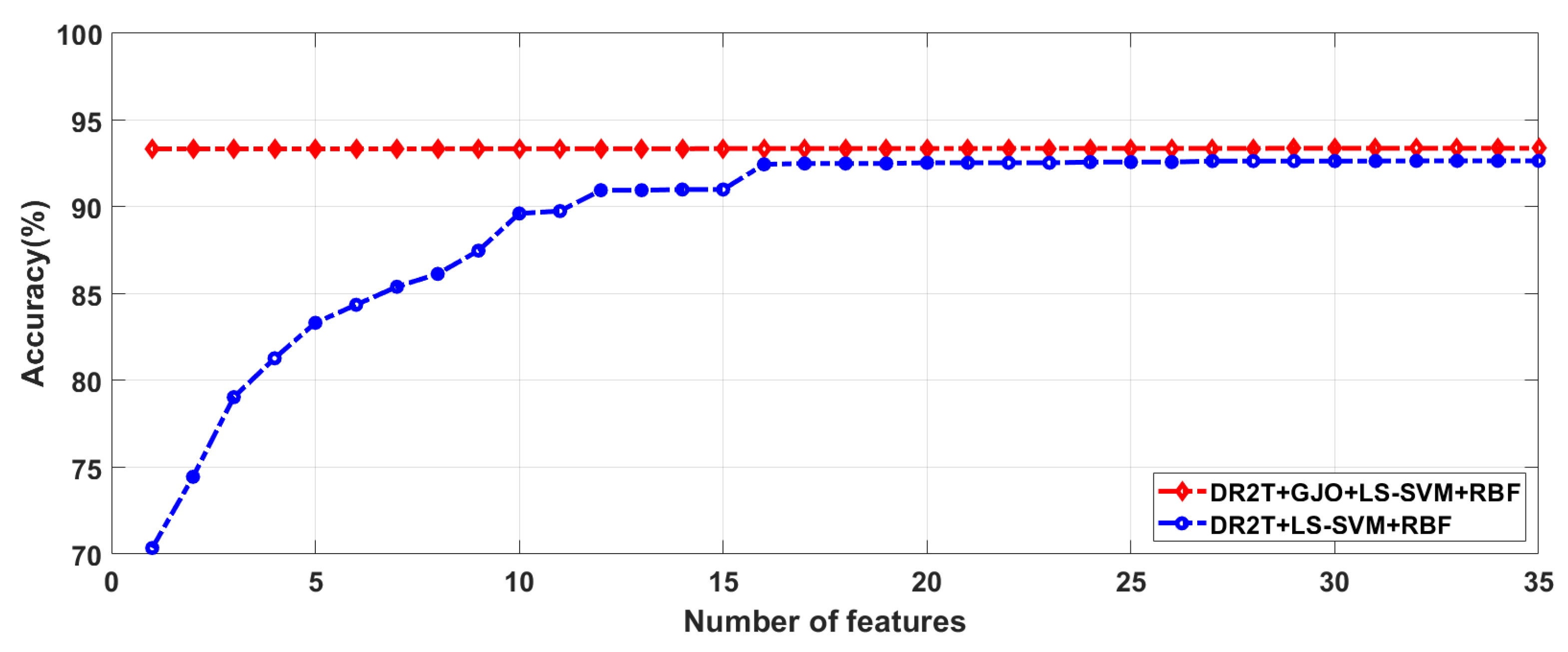

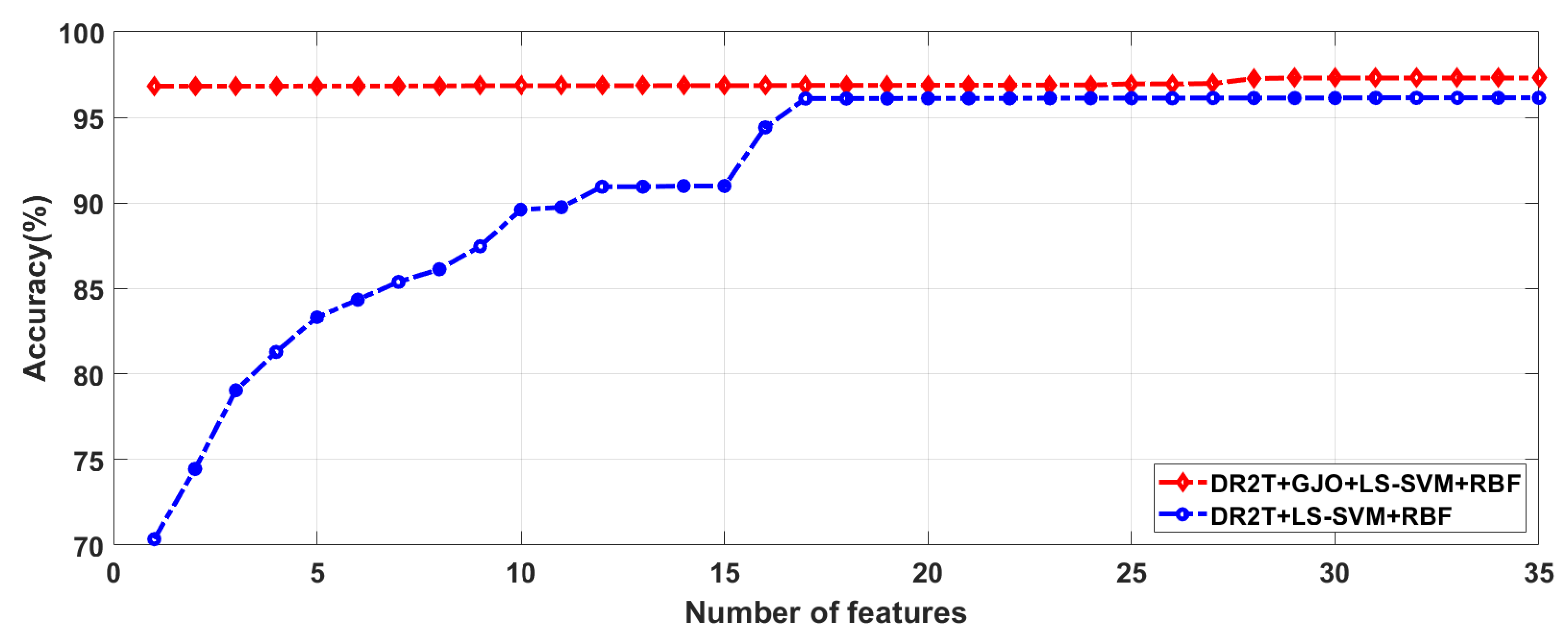

4.2. Feature selection results

| Proposed Method | No. of feature |

G1020 | ORIGA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR2T+LS-SVM+Linear | 32 | 91.42 | 88.14 | 92.76 | 94.62 | 94.03 | 94.82 |

| DR2T+LS-SVM+Polynomial | 32 | 92.16 | 88.98 | 93.45 | 95.38 | 91.04 | 96.89 |

| DR2T+LS-SVM+RBF | 32 | 92.65 | 91.53 | 93.10 | 96.15 | 94.03 | 96.89 |

| DR2T+GJO+LS-SVM+Linear | 29 | 92.63 | 90.60 | 93.45 | 95.77 | 95.52 | 95.82 |

| DR2T+GJO+LS-SVM+Polynomial | 29 | 93.14 | 90.68 | 94.14 | 96.54 | 96.37 | 97.01 |

| DR2T+GJO+LS-SVM+RBF | 29 | 93.38 | 92.37 | 93.79 | 97.31 | 97.01 | 97.41 |

| -Accuracy, -Sensitivity, -Specificity | |||||||

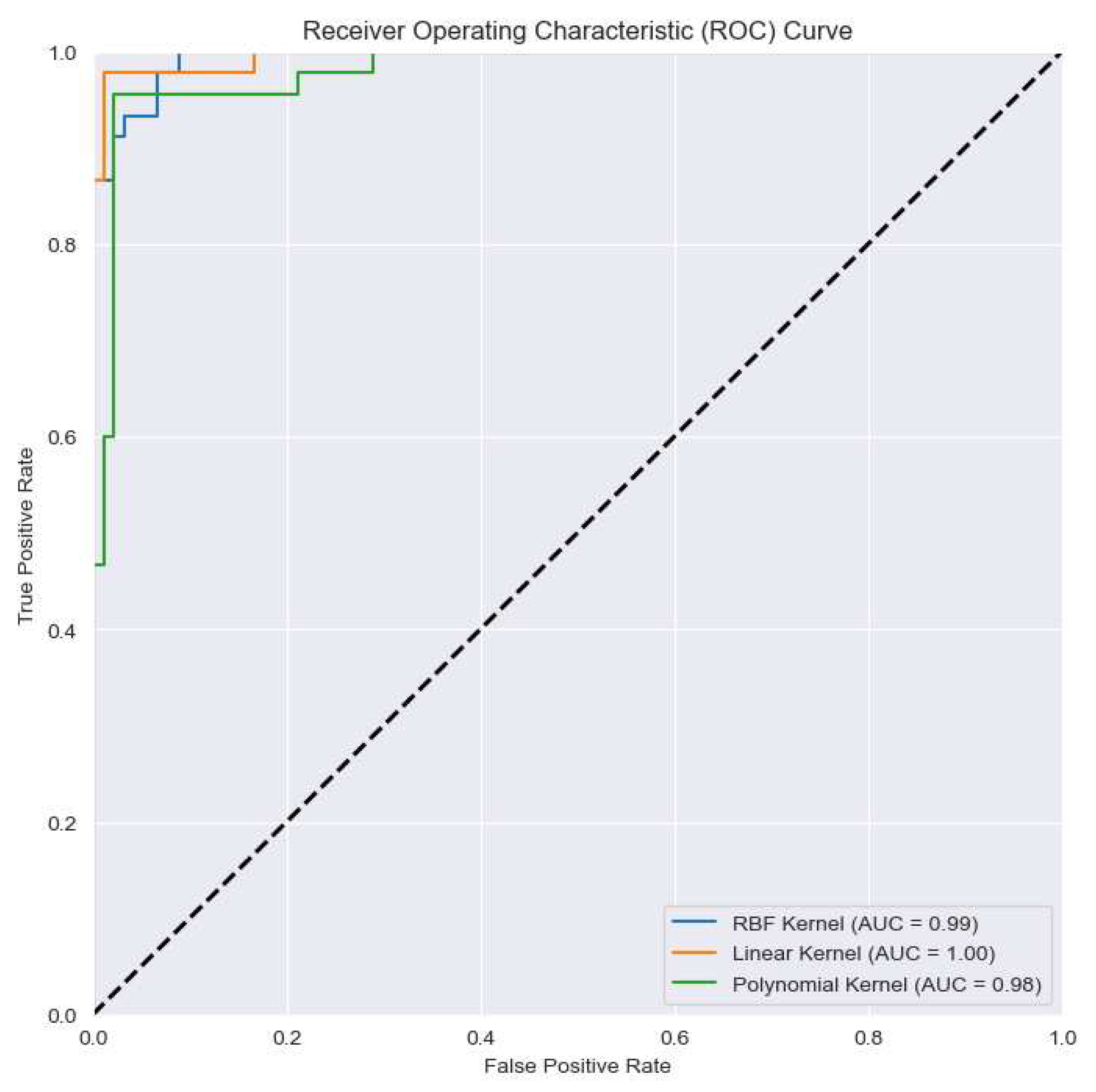

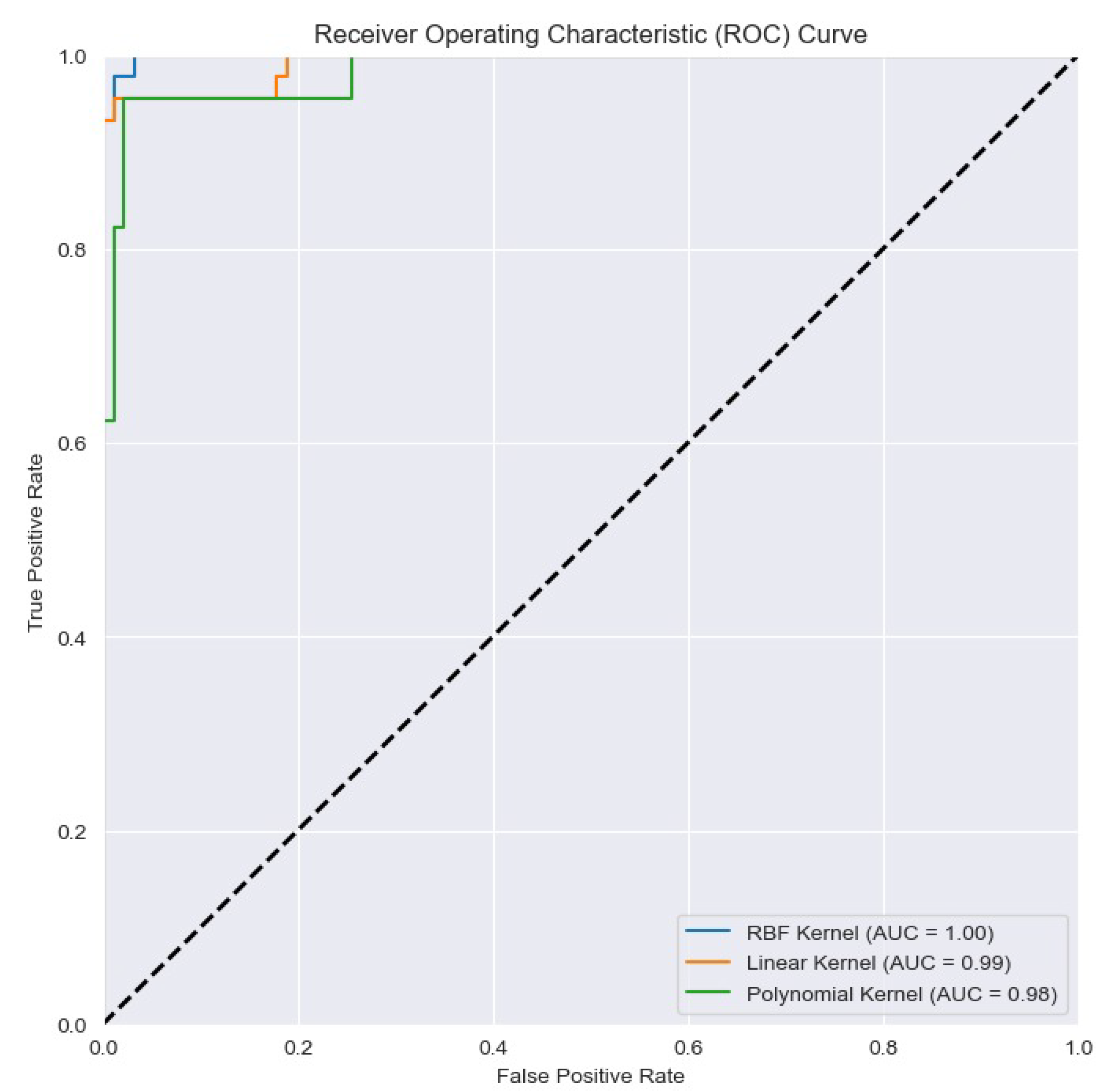

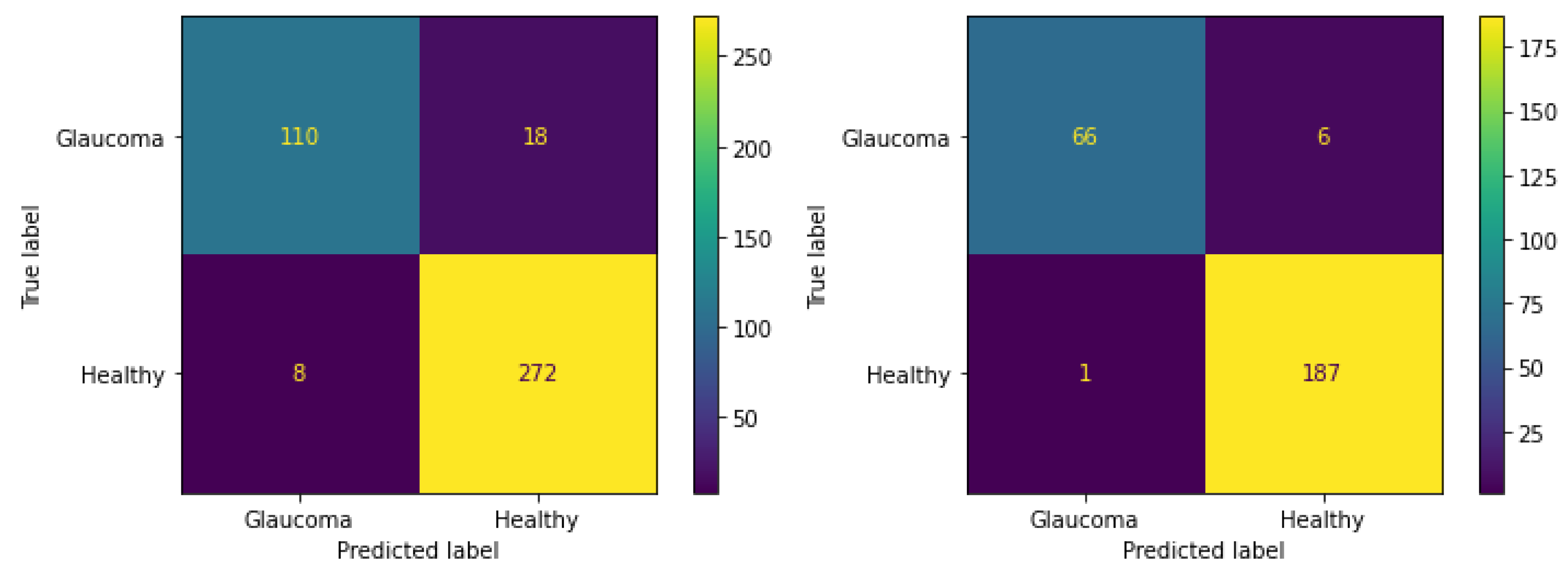

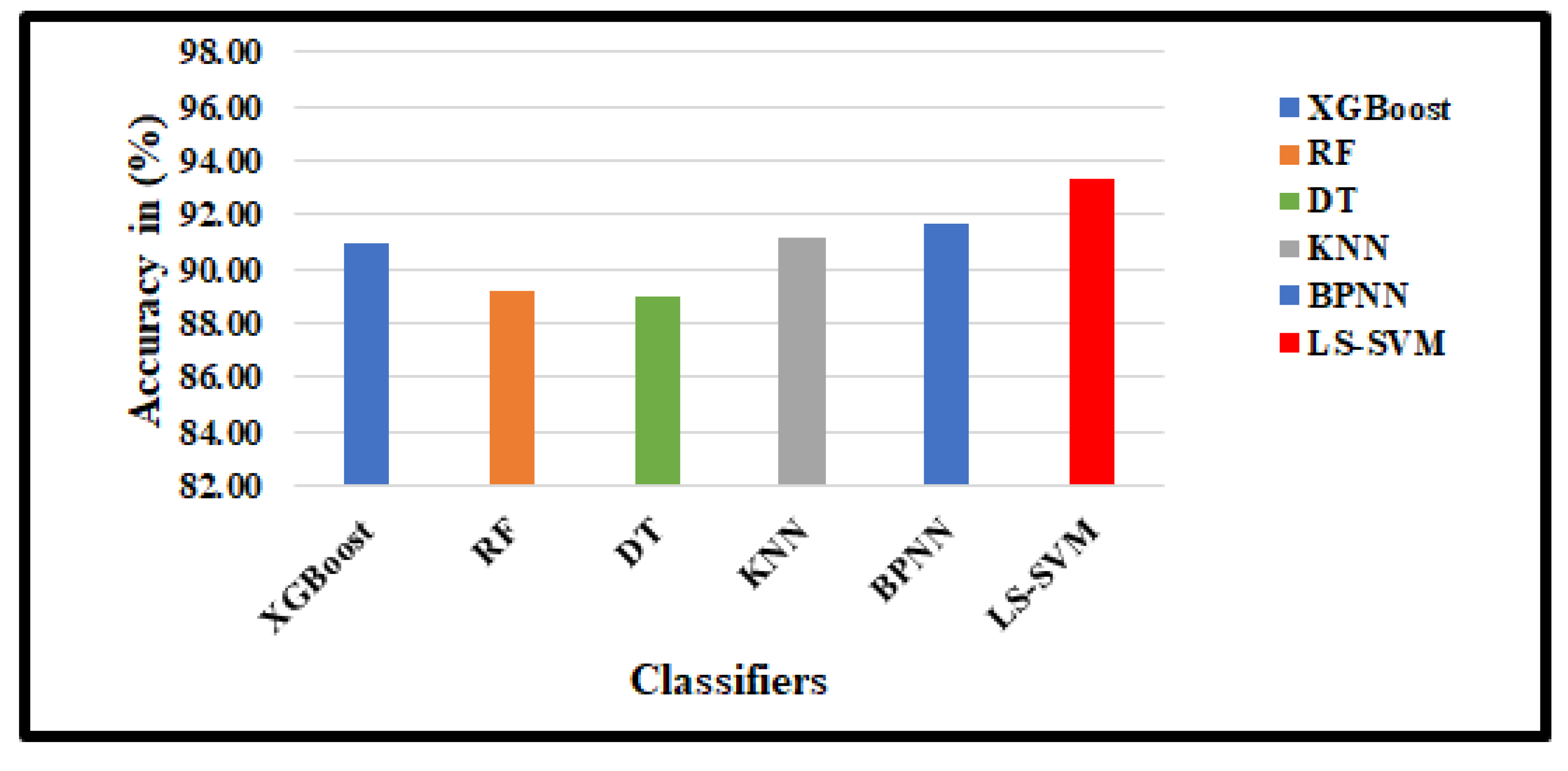

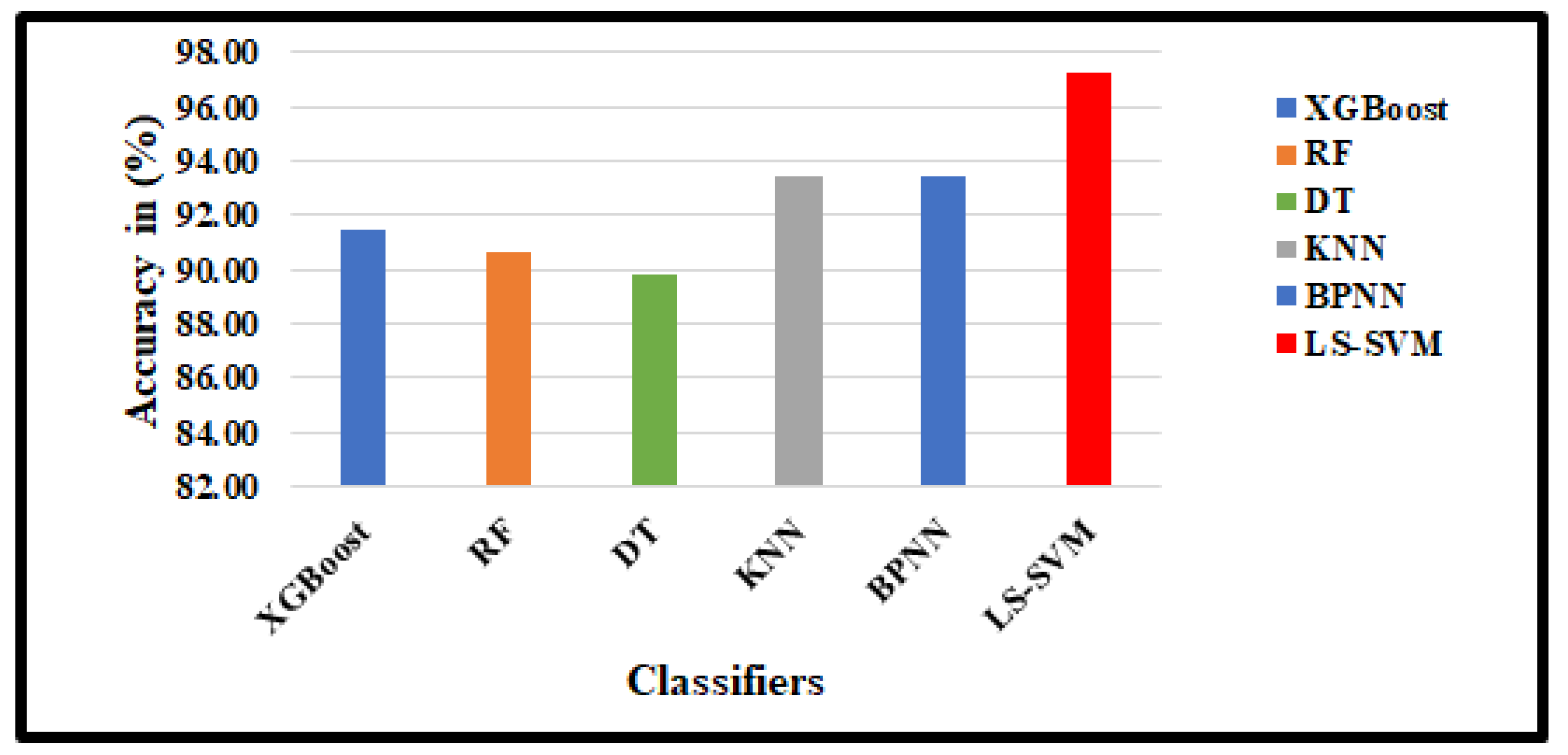

4.3. Classification results

| Classifiers | G1020 Dataset | ORIGA Dataset | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 90.93 | 87.29 | 92.41 | 91.41 | 88.89 | 92.23 |

| RF | 89.22 | 83.90 | 91.38 | 90.63 | 87.38 | 91.71 |

| DT | 88.97 | 86.97 | 90.00 | 89.84 | 85.84 | 91.19 |

| KNN | 91.18 | 87.29 | 92.76 | 93.44 | 92.54 | 93.75 |

| BPNN | 91.67 | 89.83 | 92.41 | 93.46 | 89.55 | 94.82 |

| DR2T+GJO+LS-SVM+RBF(Proposed) | 93.38 | 92.37 | 93.79 | 97.31 | 97.01 | 97.41 |

| : Accuracy, : Sensitivity , : Specificity | ||||||

| Schemes | No. of features | Dataset ( in (%) | |

| G1020 | ORIGA | ||

| DWT+LS-SVM | 32 | 90.20 | 91.92 |

| DWT+GJO+LS-SVM | 32 | 91.42 | 94.23 |

| FDCT+GJO+LS-SVM | 32 | 91.98 | 95.38 |

| DR2T+GJO+LS-SVM | 29 | 93.38 | 97.31 |

| R | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.63 | 92.64 |

| 2 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.65 |

| 3 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.63 | 92.64 |

| 4 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.65 |

| 5 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.65 | 92.65 |

| 6 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 93.65 | 93.65 | 92.65 |

| 7 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.63 | 92.63 | 92.64 |

| 8 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.65 |

| 9 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.65 |

| 10 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.65 | 92.63 | 92.65 | 92.65 |

| Final Result | 92.65 ± 0.0045 | |||||

| : Fold Number, R: Run, : Average Accuracy | ||||||

| R | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.63 | 93.63 | 93.43 |

| 2 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.63 | 93.63 | 93.43 |

| 3 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.3 | 93.3 | 93.30 |

| 4 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.63 | 93.63 | 93.43 |

| 5 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.63 | 93.63 | 93.43 |

| 6 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 |

| 7 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.63 | 93.63 | 93.43 |

| 8 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 |

| 9 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.63 | 93.63 | 93.43 |

| 10 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 | 93.30 |

| Final Result | 93.38 ± 0.0636 | |||||

| : Fold Number, R: Run, : Average Accuracy | ||||||

| R | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.17 |

| 2 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.17 |

| 3 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.08 |

| 4 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.17 |

| 5 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.17 |

| 6 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.08 |

| 7 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.17 |

| 8 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.17 |

| 9 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.27 | 96.17 |

| 10 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.03 | 96.27 | 96.08 |

| Final Result | 96.15 ± 0.0017 | |||||

| : Fold Number, R: Run, : Average Accuracy | ||||||

| R | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 97.31 | 97.30 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 |

| 2 | 97.31 | 97.30 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 |

| 3 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 |

| 4 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 |

| 5 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 |

| 6 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 |

| 7 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 |

| 8 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.30 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 |

| 9 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.30 | 97.31 | 97.31 | 97.31 |

| 10 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 | 97.30 |

| Final Result | 97.31 ± 0.0045 | |||||

| : Fold Number, R: Run, : Average Accuracy | ||||||

4.4. Compariosn with other state-of-the-art models

| Existing Methods | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Datasets | ||

| G1020 | ORIGA | |

| 2D-FBSE-EWT [46] | — | 91.01 |

| SMOTE+RF [47] | — | 78.30 |

| SMOTE+SVM [47] | — | 82.80 |

| HOG+SVM [48] | 83.32 | — |

| HOG +PNN [48] | 87.92 | — |

| HOG+RNN [48] | 85.72 | — |

| DR2T+GJO+LS-SVM+RBF(Proposed Model) | 93.38 | 97.31 |

| - Accuracy | ||

4.5. Advantages and Disadvantages of Proposed Model

5. Conclusions and Future Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, A.; Dutta, M.K.; ParthaSarathi, M.; Uher, V.; Burget, R. Image processing based automatic diagnosis of glaucoma using wavelet features of segmented optic disc from fundus image. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2016, 124, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drance, S.; Anderson, D.R.; Schulzer, M.; Group, C.N.T.G.S.; others. Risk factors for progression of visual field abnormalities in normal-tension glaucoma. American journal of ophthalmology 2001, 131, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Cheng, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wong, D.W.K.; Liu, J.; Cao, X. Disc-aware ensemble network for glaucoma screening from fundus image. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2018, 37, 2493–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garway-Heath, D.; Hitchings, R. Quantitative evaluation of the optic nerve head in early glaucoma. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1998, 82, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, D.; Dash, R.; Majhi, B. Automated breast cancer detection in digital mammograms: A moth flame optimization based ELM approach. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2020, 59, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, D.; Dash, R.; Majhi, B. Automated diagnosis of breast cancer using multi-modal datasets: A deep convolution neural network based approach. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 71, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, D.; Dash, R.; Majhi, B. Fast discrete curvelet transform and modified PSO based improved evolutionary extreme learning machine for breast cancer detection. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 70, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, D.; Priyadarshini, R.; Barik, R.C.; Nanda, S.K.; Barik, R.K.; Roy, D.S. Automated Diagnosis of Breast Cancer using Combined Features and Random Forest Classifier. 2023 6th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Networks (ISCON). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–4.

- Muduli, D.; Dash, R.; Majhi, B. Enhancement of Deep Learning in Image Classification Performance Using VGG16 with Swish Activation Function for Breast Cancer Detection. Computer Vision and Image Processing: 5th International Conference, CVIP 2020, Prayagraj, India, December 4-6, 2020, Revised Selected Papers, Part I 5. Springer, 2021, pp. 191–199.

- Muduli, D.; Kumar, R.R.; Pradhan, J.; Kumar, A. An empirical evaluation of extreme learning machine uncertainty quantification for automated breast cancer detection. Neural Computing and Applications, 2023, pp. 1–16.

- Sharma, S.K.; Zamani, A.T.; Abdelsalam, A.; Muduli, D.; Alabrah, A.A.; Parveen, N.; Alanazi, S.M. A Diabetes Monitoring System and Health-Medical Service Composition Model in Cloud Environment. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 32804–32819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Priyadarshi, A.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Pradhan, J.; Sarangi, P.K. Comparative Analysis of Different Classifiers Using Machine Learning Algorithm for Diabetes Mellitus. In Meta Heuristic Techniques in Software Engineering and Its Applications: METASOFT 2022; Springer, 2022; pp. 32–42.

- Yin, F.; Lee, B.H.; Yow, A.P.; Quan, Y.; Wong, D.W.K. Automatic ocular disease screening and monitoring using a hybrid cloud system. 2016 IEEE international conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE green computing and communications (GreenCom) and IEEE cyber, physical and social computing (CPSCom) and IEEE smart data (SmartData). IEEE, 2016, pp. 263–268.

- Islam, M.T.; Imran, S.A.; Arefeen, A.; Hasan, M.; Shahnaz, C. Source and camera independent ophthalmic disease recognition from fundus image using neural network. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Information, Communication & Systems (SPICSCON). IEEE, 2019, pp. 59–63.

- Maheshwari, S.; Pachori, R.B.; Acharya, U.R. Automated diagnosis of glaucoma using empirical wavelet transform and correntropy features extracted from fundus images. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2016, 21, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Pachori, R.B.; Kanhangad, V.; Bhandary, S.V.; Acharya, U.R. Iterative variational mode decomposition based automated detection of glaucoma using fundus images. Computers in biology and medicine 2017, 88, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausu, T.; Gopi, V.P.; Wahid, K.A.; Doma, W.; Niwas, S.I. Combination of clinical and multiresolution features for glaucoma detection and its classification using fundus images. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2018, 38, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, U.; Bhandary, S.V.; Gudigar, A.; Acharya, U.R. Novel expert system for glaucoma identification using non-parametric spatial envelope energy spectrum with fundus images. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2018, 38, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, D.; Agrawal, D.K.; Tyagi, P.K.; Rathore, N. Automated Glaucoma Classification Using Advanced Image Decomposition Techniques From Retinal Fundus Images. In AI-Enabled Smart Healthcare Using Biomedical Signals; IGI Global, 2022; pp. 240–258.

- Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Ji, J.; Yang, J.; Guo, W.; Gong, Z.; Yi, Y.; Wang, J. Deep sparse autoencoder integrated with three-stage framework for glaucoma diagnosis. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2022, 37, 7944–7967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyla, N.J.; Emmanuel, W.S. Automated classification of glaucoma using DWT and HOG features with extreme learning machine. 2021 third international conference on intelligent communication technologies and virtual mobile networks (ICICV). IEEE, 2021, pp. 725–730.

- Balasubramanian, K.; N. P., A. Correlation-based feature selection using bio-inspired algorithms and optimized KELM classifier for glaucoma diagnosis. Applied Soft Computing 2022, 128, 109432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, J.; Tu, S.; Xiao, C.; Bilal, A.; Ur Rehman, S.; Ahmad, Z. Enhanced Nature Inspired-Support Vector Machine for Glaucoma Detection. Computers, Materials & Continua 2023, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, C.; Gangatharan, N. A hybrid swarm algorithm for optimizing glaucoma diagnosis. Computers in biology and medicine 2015, 63, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, M.N.; Singh, G.A.P.; Neumeier, W.; Malik, M.I.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S. G1020: A benchmark retinal fundus image dataset for computer-aided glaucoma detection. 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–7.

- Zhang, Z.; Yin, F.S.; Liu, J.; Wong, W.K.; Tan, N.M.; Lee, B.H.; Cheng, J.; Wong, T.Y. Origa-light: An online retinal fundus image database for glaucoma analysis and research. 2010 Annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology. IEEE, 2010, pp. 3065–3068.

- Pizer, S.M. Contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization: Speed and effectiveness stephen m. pizer, r. eugene johnston, james p. ericksen, bonnie c. yankaskas, keith e. muller medical image display research group. Proceedings of the first conference on visualization in biomedical computing, Atlanta, Georgia, 1990, Vol. 337, p. 2.

- Pisano, E.D.; Zong, S.; Hemminger, B.M.; DeLuca, M.; Johnston, R.E.; Muller, K.; Braeuning, M.P.; Pizer, S.M. Contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization image processing to improve the detection of simulated spiculations in dense mammograms. Journal of Digital imaging 1998, 11, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.N.; Vetterli, M. The finite ridgelet transform for image representation. IEEE Transactions on image Processing 2003, 12, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candès, E.J.; Donoho, D.L. Ridgelets: A key to higher-dimensional intermittency? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1999, 357, 2495–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candès, E.J.; Donoho, D.L. ; others. Curvelets: A surprisingly effective nonadaptive representation for objects with edges, Department of Statistics, Stanford University USA, 1999.

- Candes, E.; Demanet, L.; Donoho, D.; Ying, L. Fast discrete curvelet transforms. multiscale modeling & simulation 2006, 5, 861–899. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yang, L.; Wu, D. Ripplet: A new transform for image processing. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2010, 21, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, M.; Ghassemian, H. Remote sensing image fusion using ripplet transform and compressed sensing. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2014, 12, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, D. Ripplet transform type II transform for feature extraction. IET Image processing 2012, 6, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormack, A.M. The Radon transform on a family of curves in the plane. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1981, 83, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormack, A. The Radon transform on a family of curves in the plane. II. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1982, 86, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubecka, L.; Jan, J. Registration of bimodal retinal images-improving modifications. The 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE, 2004, Vol. 1, pp. 1695–1698.

- Larabi-Marie-Sainte, S.; Alskireen, R.; Alhalawani, S. Emerging applications of bio-inspired algorithms in image segmentation. Electronics 2021, 10, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.; Prajapati, S.; Gourisaria, M.K.; Pattanayak, R.M.; Alameen, A.; Kolhar, M. Feature Selection Using Golden Jackal Optimization for Software Fault Prediction. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, M.; Shanmugam, K.P.; Shyu, C.R. Application of Machine Learning Predictive Models for Early Detection of Glaucoma Using Real World Data. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Robles, F.; Verdú-Monedero, R.; Berenguer-Vidal, R.; Morales-Sánchez, J.; Sellés-Navarro, I. Analysis of the Asymmetry between Both Eyes in Early Diagnosis of Glaucoma Combining Features Extracted from Retinal Images and OCTs into Classification Models. Sensors 2023, 23, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, D.R.; Dash, R.; Majhi, B. Least squares SVM approach for abnormal brain detection in MRI using multiresolution analysis. 2015 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security (ICCCS). IEEE, 2015, pp. 1–6.

- Suykens, J.A.; Vandewalle, J. Least squares support vector machine classifiers. Neural processing letters 1999, 9, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N.B.; Babu, K.S.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Bakshi, S. Face expression recognition system based on ripplet transform type II and least square SVM. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2019, 78, 4789–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.K.; Pachori, R.B. Automatic diagnosis of glaucoma using two-dimensional Fourier-Bessel series expansion based empirical wavelet transform. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 64, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, F.; Mai, Y.; Tang, J.; Duan, X.; Zou, B.; Jiang, L. Glaucoma screening pipeline based on clinical measurements and hidden features. IET Image Processing 2019, 13, 2213–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananya, S.; Bharamagoudra, M.R.; Bharath, K.; Pujari, R.R.; Hanamanal, V.A. Glaucoma Detection using HOG and Feed-forward Neural Network. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Integrated Circuits and Communication Systems (ICICACS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

| Data sets | Total Images | Training Images | Testing Images | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | H | G | H | G | H | |

| G1020 | 296 | 724 | 178 | 434 | 118 | 290 |

| ORIGA | 168 | 482 | 101 | 289 | 67 | 193 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).