Introduction

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is the most common cause of sepsis in adult ICU patients (1). Its incidence varies between centres and countries but has increased significantly during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (2,3). Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the major microorganisms associated with VAP (3,4,5). Its high capacity to adapt and develop antimicrobial resistance (6) makes P. aeruginosa a potentially resistant microorganism when deciding on empirical antimicrobial treatment. Currently, conventional microbiological techniques take a median of 24-48 hours to obtain a positive result from a quality respiratory specimen and more than 72 hours to identify the microorganism and its antimicrobial susceptibility (ATB).

Rapid identification of a sepsis-causing organism is essential for early, targeted and effective antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients (7,8). New technologies for rapid molecular diagnosis using multiplex PCR allow rapid and accurate microbiological diagnosis using relatively simple techniques. Without adequate clinical support from multidisciplinary groups (PROA - Programme for Antimicrobial Optimisation) and the development of decision support algorithms, the implementation of these modern rapid diagnostic technologies can lead to clinician confusion, high variability in practice and suboptimal clinical impact (9,10). Therefore, effective implementation strategies and multidisciplinary involvement are needed to ensure correct interpretation of results and appropriate antimicrobial stewardship so that these new technologies are cost-effective rather than resource-consuming (9-11).

Delayed identification of the microorganism may not only delay the administration of effective antimicrobial therapy, increasing mortality, but may also lead to overuse of empiric broad-spectrum antimicrobials, increasing healthcare costs and antimicrobial resistance (11,12).

The BIOFIRE® FILMARRAY® Pneumonia Panel (BPP) uses automated real-time multiplex polymerase chain reaction technology to identify nucleic acid sequences for 18 bacteria, 7 antibiotic resistance markers and 9 viruses that cause pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections. The BPP and other similar rapid diagnostic systems for the identification of micro-organisms in respiratory specimens significantly reduce the time required to identify the micro-organism (13,14,15), but to really improve the benefit, rapid and effective communication of results and early decision making is required.

Although there is a large literature on the impact of rapid diagnostic tests for GNB infections (13-15), most data focus on measures of microbiological process or antimicrobial administration time. In contrast, data describing the benefits on antimicrobial consumption and the impact on local resistance patterns are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the impact of using a consensus-based decision support algorithm based on rapid microbiological techniques on microbial resistance and antimicrobial use from an epidemiological perspective.

Primary objective

To evaluate the impact on antimicrobial consumption and Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacterial resistance of the application of a consensus-based rapid diagnostic algorithm for decision support in all consecutive critically ill patients admitted to the ICU during the study period.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was to assess variation in overall antibiotic consumption measured in DDD (defined daily doses) and in the resistance pattern of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes included crude ICU mortality in the overall pre- and post-intervention population, length of stay and days under invasive mechanical ventilation.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was annual antibiotic (ATB) consumption measured in defined daily doses (DDD).

The secondary endpoints were the crude annual ICU mortality and the variation in the ATB sensitivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during the post-intervention period.

Material and Method

Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective pre-intervention/post-intervention study comparing the management of critically ill patients admitted to the 28-bed intensive care unit (ICU) before and after the implementation of a consensus-based rapid diagnostic algorithm for decision support. The pre-intervention period was January 2018 through December 2018, and the post-intervention period was January 2019 to December 2021.

In 2018, very high microbial resistance (> 40%) to the antimicrobials used as empirical treatment in respiratory infection (meropenem and piperacillin tazobactam) for

Pseudomonas aeruginosa was evidenced (

Figure 1).

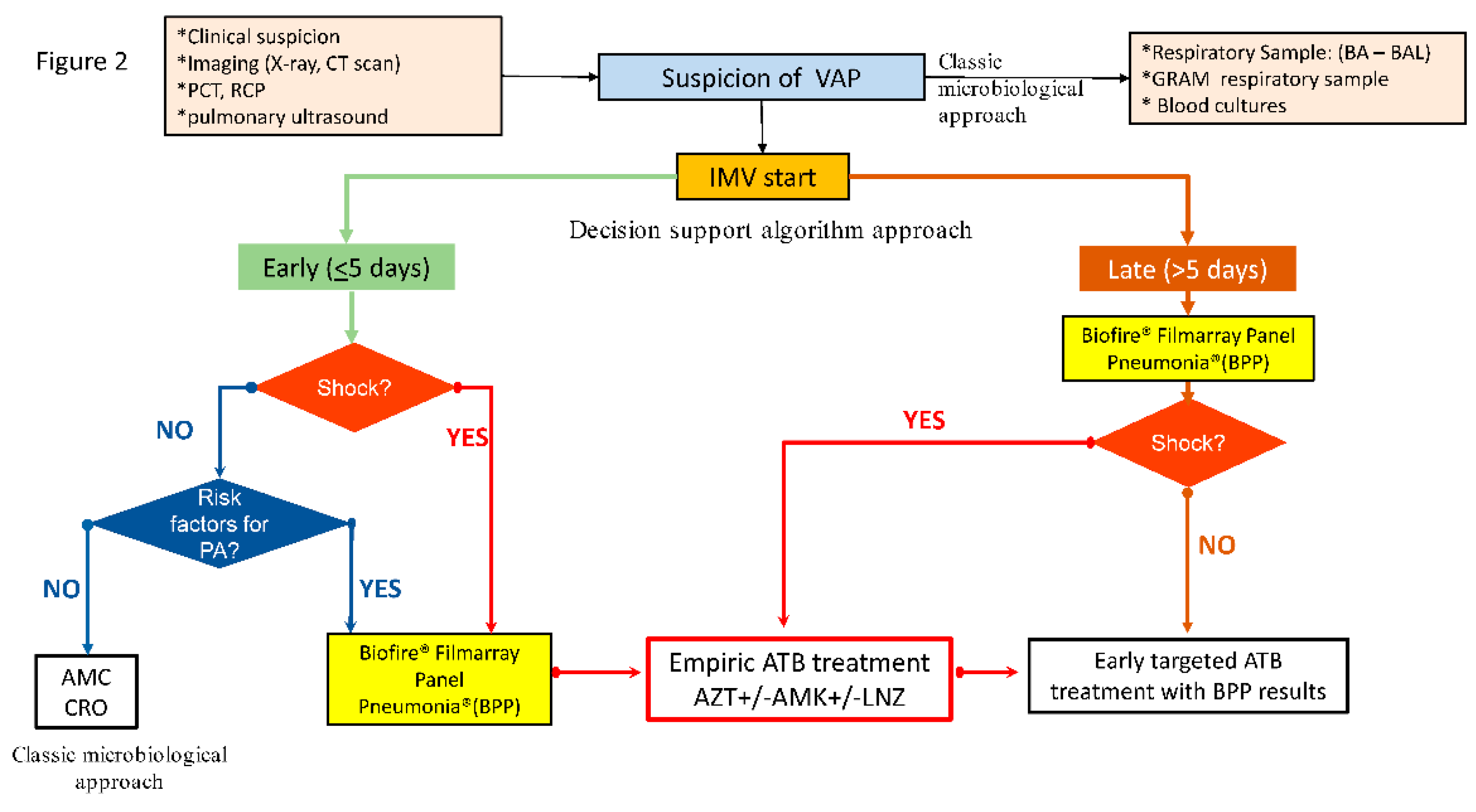

The PROA team agreed on a rapid diagnostic algorithm (

Figure 2) to be applied from January 2019 in all patients with suspected or confirmed lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) at risk of potential MDR

P. aeruginosa (e-Table 1), to reduce the possibility of inappropriate empirical antibiotic treatment. Patients admitted in 2018 were considered the reference group (pre-intervention), and comparisons were made with patients admitted in 2019-2021 (post-intervention group).

To improve compliance with the clinical decision-making algorithm, we employ a clustered approach in different actions:

(1) Dissemination of the clinical decision algorithm to all ICU staff physicians from the PROA team through regular face-to-face meetings.

(2) Educational lectures related to the methodology and impact of antimicrobial treatment optimisation were offered to all ICU medical staff.

3) Real-time communication of Biofire® Panel Pneumonia results to the requesting physician via phone call and electronic medical record.

(4) Prospective audit by the PROA team with real-time intervention and feedback to ICU attending physicians during the intervention period for all patients with suspected LRTI.

Figure 2.

Consensus decision-support algorithm based on rapid microbiological diagnostic techniques applied in the post-intervention period. (PCT: procalcitonin, RCP: Reactive C Protein, VAP: Ventilator associated pneumonia, BA: Bronchial aspirate, BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage, IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation, AMC: amoxicillin/clavulanate, CRO: ceftriaxone, AZT: aztreonam, AMK: amikacin, LNZ: linezolid, ATB: antibiotic).

Figure 2.

Consensus decision-support algorithm based on rapid microbiological diagnostic techniques applied in the post-intervention period. (PCT: procalcitonin, RCP: Reactive C Protein, VAP: Ventilator associated pneumonia, BA: Bronchial aspirate, BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage, IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation, AMC: amoxicillin/clavulanate, CRO: ceftriaxone, AZT: aztreonam, AMK: amikacin, LNZ: linezolid, ATB: antibiotic).

Laboratory Methods

In both the pre- and post-intervention periods, cultures of respiratory samples (bronchial aspirate [BA] or bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL]) were performed according to standard techniques.

Gram stain of respiratory samples was performed in all patients to assess sample quality. Samples considered to be of poor quality were not processed and a new respiratory sample was requested.

During the intervention period, the BIOFIRE® Filmarrays PNEUMONIA® panel was also used according to the manufacturer's instructions following the consensus algorithm.

Reporting Methods

In both periods, the results of the respiratory Gram stain or identification and antibiogram were communicated by telephone to the intensivists from the microbiology service within 30 minutes of Gram or microorganism identification.

During the intervention period, a microbiologist communicated BPP results directly to a member of the ICU care team within 2 hours of obtaining the quality respiratory specimen. Overnight and weekend results were reported directly to the intensivist by the microbiology technician.

No restrictive antibiotic policy was applied, and the attending physician was free to choose the antimicrobial to be administered during his or her night duty if the microorganism was other than Pseudomonas, in which case the algorithm suggested starting aztreonam (AZT) at a dose of 8 g/day in continuous perfusion. Antibiotic treatment was reviewed by the PROA team on the next working morning and adjusted according to pathogen-specific results, clinical interpretation, national guidelines and local antibiogram data.

Nosocomial Infection Prevention Measures

Similar nosocomial infection prevention measures were applied throughout the study (both periods) according to the established national protocols (Pneumonia Zero®, Bacteraemia Zero® and Resistance Zero®) in the ENVIN-HELICS (ENVIN - HELICS (vhebron.net )) Our ICU does not use selective digestive decontamination in patients under mechanical ventilation. No additional prevention bundles were implemented, with the exception of the rapid diagnostic algorithm for LRTI in the post-intervention period.

Data Collection

Clinical and Laboratory Data

Clinical and laboratory data were collected from the from the clinical information system (CIS, Centricity Critical Care® by General Electric) by ETL (extract, transform and load) by SQL and Python. The CIS automatically incorporates data from all upstream devices every 2 minutes as well as laboratory values. In addition, physicians include patient-related information as an adverse event record (e.g. VAP) throughout the patient care process during the ICU stay.

Antimicrobial Consumption Data

To measure antimicrobial consumption according to WHO, we use the defined daily dose (DDD) methodology. DDD is the average daily maintenance dose of an antimicrobial substance used for its primary indication in adults. (16) . The DDDs per 100 occupied bed-days were recorded pre- and post-intervention for all antibiotics with special interest in those with antipseudomonal activity. DDD was calculated by considering the total number of grams of each antibiotic consumed in a hospital unit during a given period, divided by the DDD value set by the WHO for the antibiotic in question and by the number of stays in the same period of time. The consumption data are obtained by the pharmacy computer application and the number of stays by the hospital management computer system. These data are usually calculated on a quarterly and annual basis.

Microbiological Data

The different bacterial isolates were obtained after seeding the samples by conventional quantitative methods according to the protocols of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) (17) Identification was performed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MALDI-Biotyper, Bruker Daltonics©, Bremen, Germany) and antibiotic sensitivity by microdilution technique (MicroScan WalkAway plus, Beckman-Coulter©, CA, USA) following the recommendations of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (18)

Data on incidence density of controlled intra-ICU infections were calculated according to national indicators from the ENVIN-HELICS registry.

Study Definitions

Ventilator-associated Lower respiratory tract infection (vLRTI): A diagnosis of vLRTI was based on the presence of at least two of the following criteria: body temperature of more than 38·5°C or less than 36·5°C, leucocyte count greater than 12 000 cells per μL or less than 4000 cells per μL, and purulent Bronchial aspirate (BA) or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL).

Additionally, all episodes of infection had to have a positive microbiological isolation in the BA of at least 106 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL, or with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of at least 10⁴ CFU per mL. (19)

Ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis (VAT): was defined with the aforementioned criteria with no radiographical signs of new pneumonia. (19)

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP): was defined by the presence of new or progressive infiltrates on chest radiograph. (19)

Other definitions and calculation of incidence densities of controlled infections are shown in the supplementary material.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the pre-intervention and post-intervention cohorts with continuous variables were assessed using the two-sample t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test depending on distribution. Differences between categorical variables were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

To assess the change in incidence density of infectious complications or DDD, we use rate ratio (RR) also known as incidence density ratio (IDR). The RR is a measure of association that compares the incidence of events occurring at different times.

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R.

Results

Overall Population

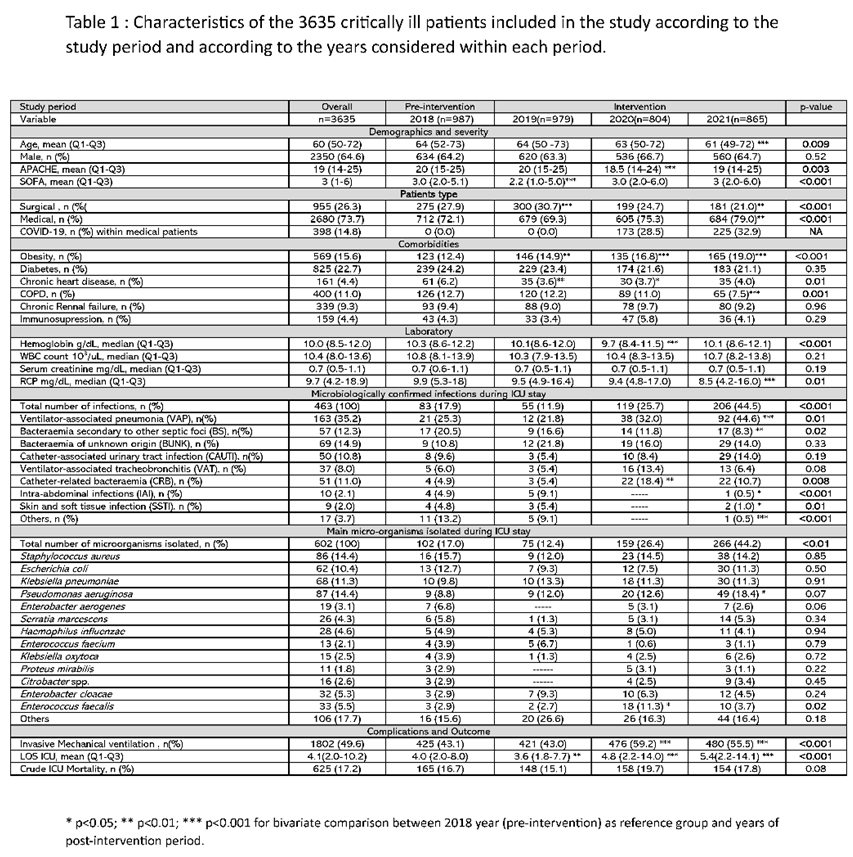

A total of 3635 patients were admitted consecutively during the study period. Of these, 987 (27.1%) were admitted in 2018 and formed the pre-intervention control group. Nine hundred seventy-nine (27.0%), 804 (22.1%) and 865 (23.8%) patients were admitted in 2019, 2020 and 2021 respectively and formed the intervention group (n= 2648) (e-

Figure 1).

The median age was 60 years, 64% male, the vast majority (95%) of patients were admitted as emergencies. The severity level showed an APACHE II of 19 points, with a SOFA of 3 points. Obesity (16.1%) and diabetes (12.1%) were the most frequent comorbidities observed. Mean ICU stay was 4 days with an overall crude ICU mortality of 17.2% and no different between the periods. The complete clinical characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 1.

A decrease in the mean age and severity of patients was observed between the pre- and post-intervention period. Statistically differences were observed in haemoglobin (Hb) concentration and serum CRP levels, but these differences are not clinically significant. (Table 1 and e-Table 2).

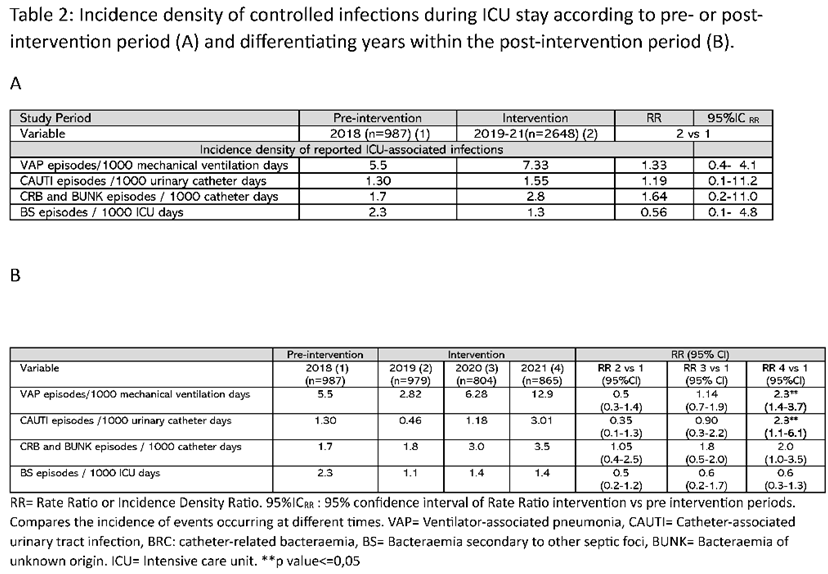

Microbiological Findings

A significant increase in the number of infections was observed between the post- and pre-intervention periods, both when considering the total number of patients (14.3% vs 8.4, p<0.001) (e-Table 1) or the total number of intra-ICU infections controlled, where an increase from 17.9% in 2018 (pre-intervention) to 44.5% (p<0.01) in 2021 (post-intervention) was observed (Table 1). This increase was mainly due to the higher number of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) cases, which increased from 25% in year 2018 to 44.6% (p<0.001) in year 2021. A similar pattern was observed when comparing the incidence density of recorded infections. The rate ratio of episodes per 1000 mechanical ventilation days was 1.3 when comparing the pre- and post-intervention periods and reached 2.3 when comparing 2018 to 2021 (Table 2).

The 2020-2021 period corresponds to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which a higher number of patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (Table 1). However, the proportion of medical and surgical patients was similar in the pre- and post-intervention periods. (e-Table 2)

Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA, 15.7%), Escherichia coli (E. coli, 12.7%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (KP, 9.8%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA, 8.8%) were the 4 most frequent microorganisms isolated in the pre-intervention period. In the post-intervention period Pseudomonas aeruginosa (15.6%, p=0.04) was the most frequent followed by MSSA (14.0%), K. pneumoniae (11.6%) and E. coli (9.8%) (e-Table 3). Despite this increase in P. aeruginosa isolation, extensive drug resistant (XDR) strains appeared less frequently in the post-intervention period (n=3) compared to the pre-intervention period (n=5) (data not shown).

Antibiotic Consumption

The rapid diagnostic algorithm was applied in 354 of 2648 patients (13.4%) with suspected LRTI. Seventy (19.7%) in 2019, 135(38.2%) in 2020 and 149 (42.1%) in 2021. LRTI (VAP + VAT) was diagnosed in 15 patients (21.4%) in 2019, 54 (40%) in 2020 and 105 (70.5%) in 2021. However, P. aeruginosa was only isolated in 4 (20.0%), 9 (16.0%) and 24 (18.2%) respectively (e-Table 3).

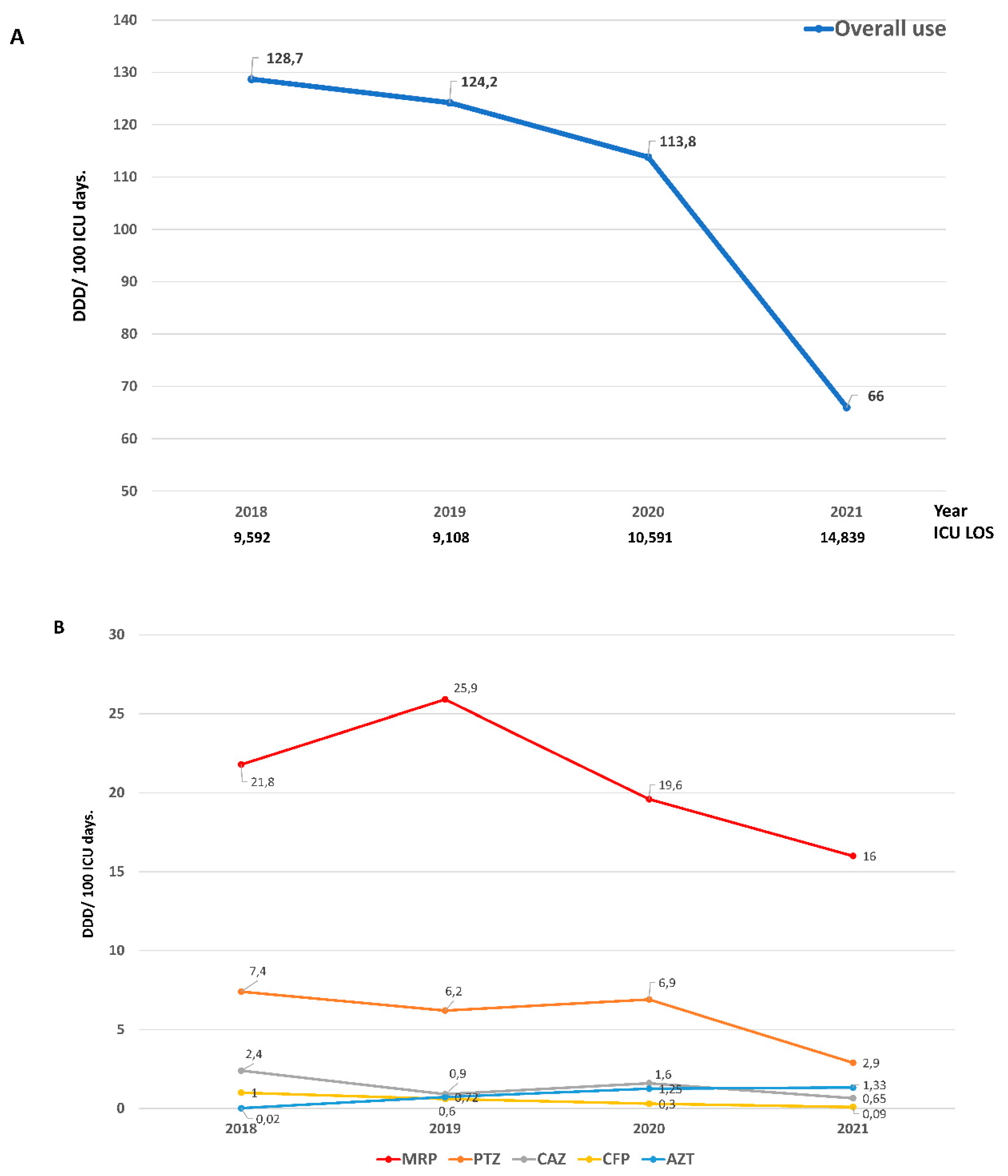

Despite the increase in the number of controlled infections, ATB consumption decreased from 128.7 DDD in 2018 to 66.0 DDD in 2021 (Rate Ratio = 0.51)

Figure 3 A. A marked reduction in the use of meropenem (Rate Ratio = 0.73), piperacillin-tazobactam (Rate Ratio= 0.39) and ceftazidime (Rate Ratio = 0.27) was observed. In contrast and as expected, the use of aztreonam increased markedly (Rate Ratio 66.5)

Figure 3 B and e-Table 4. Despite the reduction in the use of ATB in the post-intervention period, no differences were observed in crude mortality compared to the pre-intervention period (Table 1).

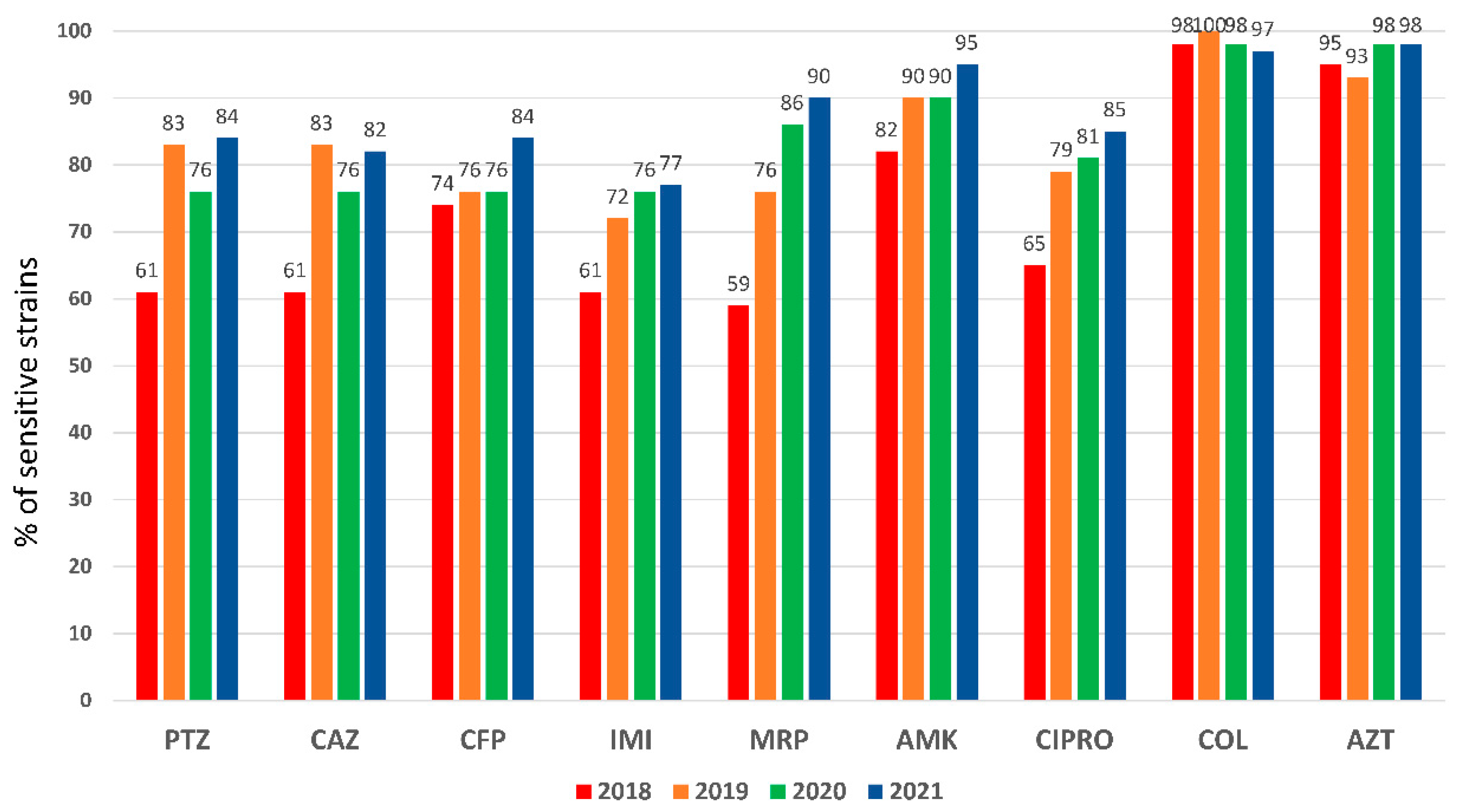

Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Susceptibility Pattern

An elevated

P. aeruginosa resistance pattern was observed in 2018 for almost all antipseudomonal antibiotics (

Figure 1). Particularly for meropenem (41%) and piperacillin-tazobactam (39%), antimicrobials used in the empirical treatment of VAP, which presented higher resistances (closed 50%) in PA isolated from respiratory specimens (e-

Figure 2). A significant recovery of sensitivity to all antibiotics was observed after implementing the rapid diagnostic algorithm. Specifically, an improvement of 23% for PTZ and 31% for MRP were observed (

Figure 1 and e-

Figure 2). The increase in the use of AZT did not affect the sensitivity pattern observed in

P. aeruginosa.

Discussion

While the data presented for the syndromic molecular test for nosocomial pneumonia clearly demonstrate high accuracy and detection of many more pathogens than culture (8-13), there is still little published information demonstrating that this translates into improved antibiotic use or clinical benefit. In this scenario, we conducted an epidemiological study to evaluate the impact of the implementation of a decision support algorithm on antibiotic consumption and microbial resistance patterns not only in patients with LRTI, but in the whole population admitted to the ICU.

Our main finding is that despite an observed increase in the incidence of nosocomial infections, the implementation of a decision support algorithm based on rapid diagnostic techniques was associated with lower antibiotic consumption and recovery of antimicrobial susceptibility in the ICU. Furthermore, this reduction in antibiotic use was not associated with an increase in crude ICU mortality. This suggests that the algorithm led to a reduction in antibiotic overuse.

The development of antimicrobial resistance is a normal evolutionary process for microorganisms, but it is accelerated by the selective pressure exerted by widespread use of antimicrobials (20). There is a strong association between antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial use levels, implying that a reduction in unnecessary antimicrobial consumption could favourably affect resistance. (21,22).

Several risk factors expose critically ill patients to an increased risk of colonization and infection by multidrug-resistant organisms, such as treatment with immunosuppressive drugs, use of invasive devices, exposure to a wide range of antibiotics, and prolonged hospitalizations (23)

Our results support a remarkable increase in LRTI in the post-intervention period. Most of this period (2020-2021) includes the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in an uncontrolled influx of critically ill patients, often receiving unnecessary antibiotic therapy (24,25). A Center for Disease Control (CDC) report published in February 2021 describes outbreaks of antimicrobial-resistant infections in COVID-19 units (26), with a marked increase in nosocomial infections, most of which are caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (27).

We did not observe an increase in XDR strains and overall susceptibility to P. aeruginosa improved over the years. These findings agree with those of Langford BJ et al (28), who reported no association between COVID-19 and the incidence of resistant P. aeruginosa (IRR 1.10, 95% CI: 0.91-1.30), nor with the proportion of resistant cases (RR 1.02, 95% CI: 0.85-1.23).

Despite this increase in the nosocomial infection observed, the application of a decision-support algorithm based on rapid microbiological diagnostic techniques allowed to decrease the consumption of antibiotics and to recover the sensitivity of old antimicrobials.

Different authors (8,13,29-31) have reported that multiplex bacterial PCR testing of quality respiratory samples decreases the duration of inadequate antibiotic treatment of patients admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and risk of Gram-negative bacilli infection. However, most of these studies have been performed in general hospitalization patients (8,29,31), in the hematologic (30) or in paediatric patient groups (13) and little information exists on the impact of these techniques in adult critically ill patients.

To the best of our knowledge only one study has included critically ill patients, and its findings agree with our results. Specifically, Rizk NA et al. (32) reported a decrease in resistance rates among Acinetobacter baumannii to imipenem from 81% in 2018 to 63% in 2020 with the implementation of antibiotic stewardship and infection control policy, especially in ICUs, with a decrease in carbapenem use at the hospital level. In addition, an open label, randomized, parallel, multicenter study (INHALE WP3) (33) has been designed to explore the potential impact of rapid molecular diagnostics coupled with a prescribing algorithm, with the goal of achieving non-inferiority in clinical cure of pneumonia and superiority in terms of antimicrobial stewardship, compared with the standard care. We hope that this study, suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic, can provide valuable information on an unmet demand for intensivists.

LTRI associated with mechanical ventilation represent the most frequent infectious episodes in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) requiring mechanical ventilation (1). LRTIs are associated with a high mortality rate (more than 50%) and a significant impact on ICU length of stay, antibiotic use, and overall healthcare costs (1,4,5). As we have observed in our study, Gram-negative pathogens are responsible for the majority of VAP and, among them, non-fermenting gram-negative pathogens, especially Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This has also been reported by other authors before (19) and during the pandemic period (34). However, a recent meta-analysis that included a study period similar to ours (2019-2021) reported that Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=65) was not the first, but the third most commonly isolated Gram-negative MDR organism after Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=169) and Acinetobacter baumannii (n=148) (35). The study population, the burden of COVID-19, the burden of non-COVID-19 respiratory infections, local epidemiology, and especially antimicrobial prescribing practices may partially explain the difference between the overall data and our findings.

Our study has several limitations that we must acknowledge. First, we did not design our protocol to assess the impact of individual interventions on outcomes. All patients who entered the algorithm received ATB after obtaining microbiological samples and we did not expect an improvement in administration times. Thus, our approach was epidemiological with the aim of studying the impact of the algorithm on "macro" indicators such as the annual consumption of ATB or the variation in sensitivity over the years.

Second, is its retrospective, nonrandomized design. Given the before/after design of the study, the results could be biased due to residual confounding factors not considered. However, the study was designed to address a clinical need and represents real-life data after applying a decision support algorithm.

Third, our study was conducted at a single centre, and the clinical results may not be directly translatable to other centres. It is necessary to consider that the findings may be influenced by the appropriate application and high acceptance of the decision algorithm.

Fourth, we only present the variation in the sensitivity pattern for Pseudomonas aeruginosa because it was the only microorganism that showed a high level of resistance during the pre-implantation period.

Finally, we did not record other outcomes such as the duration or adequacy of antimicrobial treatment. The aim of our study was to assess general indicators that reflect the adequacy of the overall treatment of critically ill patients during the study period.

Conclusion

The implementation of a decision support algorithm based on rapid microbiological diagnostic techniques resulted in a marked reduction in antibiotic consumption and bacterial resistance without affecting the prognosis of critically ill patients. The PROA team is essential for the development and implementation of these decision support algorithms.

Funding

This study was supported by Ricardo Barri Casanovas Foundation (AR). The study sponsors have no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author’ contributions

Rodríguez A, Gómez F, Sarvisé C, Gutiérrez G, Galofre Giralt M, Canadell L, Claverias L, Sans T and Bodí M had substantial contributions to conception and design of the work. Rodríguez A, Gómez F, Guerrero-Torres MD, Pardo-Granell S, Benavent Bofill C, Trefler S, Barrueta J, Esteve E, Teixidó X, and Bordonado L had substantial contribution for data acquisition. Rodríguez A, Gómez F, Sarvisé C, Gutiérrez G, Galofre Giralt M, Sans T, Bodí M, Olona M and García Pardo G had substantial contribution for data analysis and interpretation of data for the work. Rodríguez A, Gómez F, Olona M, Bodi M and Gutierrez G drafting of the manuscript. Sarvisé C, Gutiérrez G, Galofre Giralt M, Canadell L, Claverias L, Pardo-Granell S, Benavent Bofill C, Trefler S and Sans T critically reviewed the draft manuscript. The corresponding author (RA) had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Hospital Universitari de Tarragona Joan XXIII.

Availability of Data Materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this study are available from Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under Hospital Joan XXIII authorization for the present study and are therefore not publicly available. However, the data can be obtained from the corresponding author (RA) upon reasonable request and with the permission of Hospital Joan XXIII.

Acknowledgements

To all the members of the intensive care medicine, pharmacy, microbiology, and laboratory services for their daily work that makes it possible to achieve these objectives.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martín Loeches I, Reyes LF, Nseir S, et al. European Network for ICU-Related Respiratory Infections (ENIRRIs): a multinational, prospective, cohort study of nosocomial LRTI. Intensive Care Med (2023) 49:1212–1222. [CrossRef]

- Pichon M, Cremniter J, Burucoa C,,COVAP Study group. French national epidemiology of bacterial superinfections in ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients infected with COVID-19: the COVAP study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2023, 28;22(1):50. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro Freire M, Brandao de Assis D, de Melo Tavares B et al. Impact of COVID-19 on healthcare-associated infections: Antimicrobial consumption does not follow antimicrobial resistance. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2023;13:78:100231. [CrossRef]

- Tetaj N, Capone A, Stazi GV et al. Epidemiology of ventilator-associated pneumonia in ICU COVID-19 patients: an alarming high rate of multidrug-resistant bacteria. J Anesth Analg Crit Care. 2022,19;2(1):36. [CrossRef]

- Reyes LF, Rodriguez A, Fuentes YV et al. Risk factors for developing ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infection in patients with severe COVID-19: a multinational, multicentre study, prospective, observational study. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 21;13(1):6553. [CrossRef]

- Kothari A, Kherdekar R, Mago V, et al. Age of Antibiotic Resistance in MDR/XDR Clinical Pathogen of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023, 30;16(9):1230. [CrossRef]

- Timbrook TT, Morton JB, McConeghy KW, Mylonakis CE, LaPlante KL.The Effect of Molecular Rapid Diagnostic Testing on Clinical Outcomes in Bloodstream Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017;64(1):15–23. [CrossRef]

- Manatrey-Lancaster JJ, Bushman AM, Caligiuri ME, Rosa R. Impact of BioFire FilmArray respiratory panel results on antibiotic days of therapy in different clinical settings. Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology 2021, 1, e4, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Moore LSP, Villegas MV, Wenzler E, Rawson TM, Oladele RO, Doi Y. Rapid Diagnostic Test Value and Implementation in Antimicrobial Stewardship Across Low-to-Middle and High-Income Countries: A Mixed-Methods Review. Infect Dis Ther 2023,12:1445–1463. [CrossRef]

- Gatti M, Viaggi B, Rossolini GM, Pea F, Viale P. An Evidence-Based Multidisciplinary Approach Focused on Creating Algorithms for Targeted Therapy of Infection-Related Ventilator-Associated Complications (IVACs) Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in Critically Ill Adult Patients. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 33. [CrossRef]

- Pandolfo AM, Horne R, Jani Y, Reader TW et al. Intensivists’ beliefs about rapid multiplex molecular diagnostic testing and its potential role in improving prescribing decisions and antimicrobial stewardship: a qualitative study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021; 10:95. [CrossRef]

- Iregui M, Ward S, Sherman G, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator- associated pneumonia. Chest. 2002;122(1):262–8.

- Kitano T, Nishikawa H, Suzuki R, et al. The impact analysis of a multiplex PCR respiratory panel for hospitalized pediatric respiratory infections in Japan. J Infect Chemother 2020;26:82e85. [CrossRef]

- Kuitunen I, Renko M. The effect of rapid point-of-care respiratory pathogen testing on antibiotic prescriptions in acute infections – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 2023, 10(9), ofad443. [CrossRef]

- Walsh TL, Bremmer DN, Moffa MA et al. Impact of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program-bundled initiative utilizing Accelerate Pheno™ system in the management of patients with aerobic Gram-negative bacilli bacteremia. Infection 2021; 49:511–519. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). DDD Indicators. https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/indicators#:~:text=DDD%20per%20100%20bed%20days,stays%20overnight%20in%20a%20hospital (accessed on 01 August 2023).

-

https://seimc.org/contenidos/documentoscientificos/procedimientosmicrobiologia/seimc-procedimientomicrobiologia25.pdf.

-

https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints.

- Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, Rodríguez A, Curcio D, Suarez D, Mira JP, et al. Incidence and prognosis of ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis (TAVeM): a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3: 859–68. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Antimicrobial resistance. (WHO Fact sheet). Geneva: World Health Organization; February 2018 https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance, accessed 9 august 2022; Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, Zaidi AK, Wertheim HF, Sumpradit N, et al. Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1057–98. [CrossRef]

- Fridkin SK, Edwards JR, Courval JM,Hill H, Tenover FC, Lawton R, et al.; Intensive Care Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemiology (ICARE) Project and the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Hospitals. The effect of vancomycin and thirdgeneration cephalosporins on prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in 126 U.S. adult intensive care units. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135:175–83. [CrossRef]

- Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2096. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Sakr, Y.; Singer, M.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Machado, F.R.; Marshall, J.C.; Finfer, S.; Pelosi, P.; Brazzi, L.; Aditianingsih, D.; et al. Prevalence and Outcomes of Infection Among Patients in Intensive Care Units in 2017. JAMA 2020, 323, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, S.; Hays, J.P.; Kemp, A.; Okechukwu, R.; Murugaiyan, J.; Ekwanzala, M.D.; Alvarez, M.J.R.; Paul-Satyaseela, M.; Iwu, C.D.; Balleste-Delpierre, C.; et al. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global antimicrobial and biocide resistance: An AMR Insights global perspective. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab038; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomczyk, S.; Taylor, A.; Brown, A.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; El-Saed, A.; Alshamrani, M.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Jacob, M.; Löfmark, S.; Perovic, O.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the surveillance, prevention and control of antimicrobial resistance: A global survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 3045–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. COVID-19 & Antibiotic Resistance. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/covid19.html (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Weiner-Lastinger, L.M.; Pattabiraman, V.; Konnor, R.Y.; Patel, P.R.; Wong, E.; Xu, S.Y.; Smith, B.; Edwards, J.R.; Dudeck, M.A. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on healthcare-associated infections in 2020: A summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 43, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford BJ, Soucy J-P R, Leung V, So M, Kwan ATH, S. Portnoff JS et al. Antibiotic resistance associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023 Mar; 29(3): 302–309. [CrossRef]

- Darie AM, Khanna N, Jahn K, Osthoff M, Bassetti S, Osthoff M, et al. Fast multiplex bacterial PCR of bronchoalveolar lavage for antibiotic stewardship in hospitalised patients with pneumonia at risk of Gram-negative bacterial infection (Flagship II): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respi Med 2022, Pages 877-887. [CrossRef]

- Bergesea S, Foxa B, García-Allende N, Elisiri ME, Schneider AE, Ruiz J, et al. Impact of the multiplex molecular FilmArray Respiratory Panel on antibiotic prescription and clinical management of immunocompromised adults with suspected acute respiratory tract infections: A retrospective before-after study. Revista Argentina de Microbiología 2023, (in press). [CrossRef]

- Qian Y, Ai J, Wu J, Yu S, Cui P, Gao Y et al. Rapid detection of respiratory organisms with FilmArray respiratory panel and its impact on clinical decisions in Shanghai, China, 2016-2018. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2020;14:142–149. [CrossRef]

- Rizk NA, Zahreddine N, Haddad N, Ahmadieh R, Hannun A. The Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship and Infection Control Interventions on Acinetobacter baumannii Resistance Rates in the ICU of a Tertiary Care Center in Lebanon. Antibiotics 2022,11, 911. [CrossRef]

- High J, Enne VI, Barber JA, Brealey D, Turner DA, Horne R et al. INHALE: the impact of using FilmArray Pneumonia Panel molecular diagnostics for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia on antimicrobial stewardship and patient outcomes in UK Critical Care—study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Trials 2021; 22:680. [CrossRef]

- Carbonell R, Urgelles S, Rodríguez A, Bodí M, Martín-Loeches I, Solé-Violán J et al. Mortality comparison between the first and second/third waves among 3,795 critical COVID-19 patients with pneumonia admitted to the ICU: A multicentre retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe 2021;11: 100243. [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam RM, Julien DA, Jelinski DC, Larose SL, Rennert-May E, Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (November 2019–June 2021). Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control ,2022:11:45. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).