Submitted:

09 November 2023

Posted:

10 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mathematical Model Of Propeller Optimization

such that Tmin − T(x) ≤ 0,

x∊X

such that x∊X

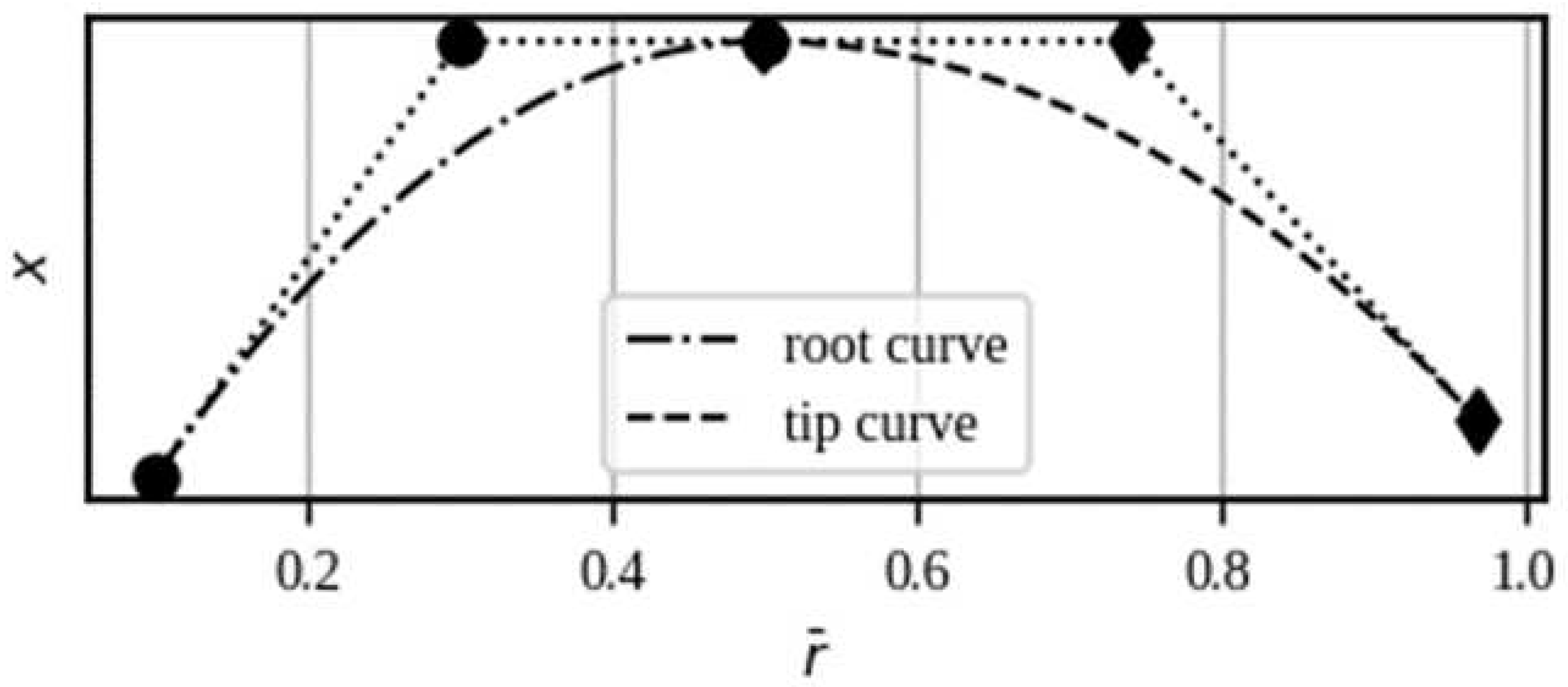

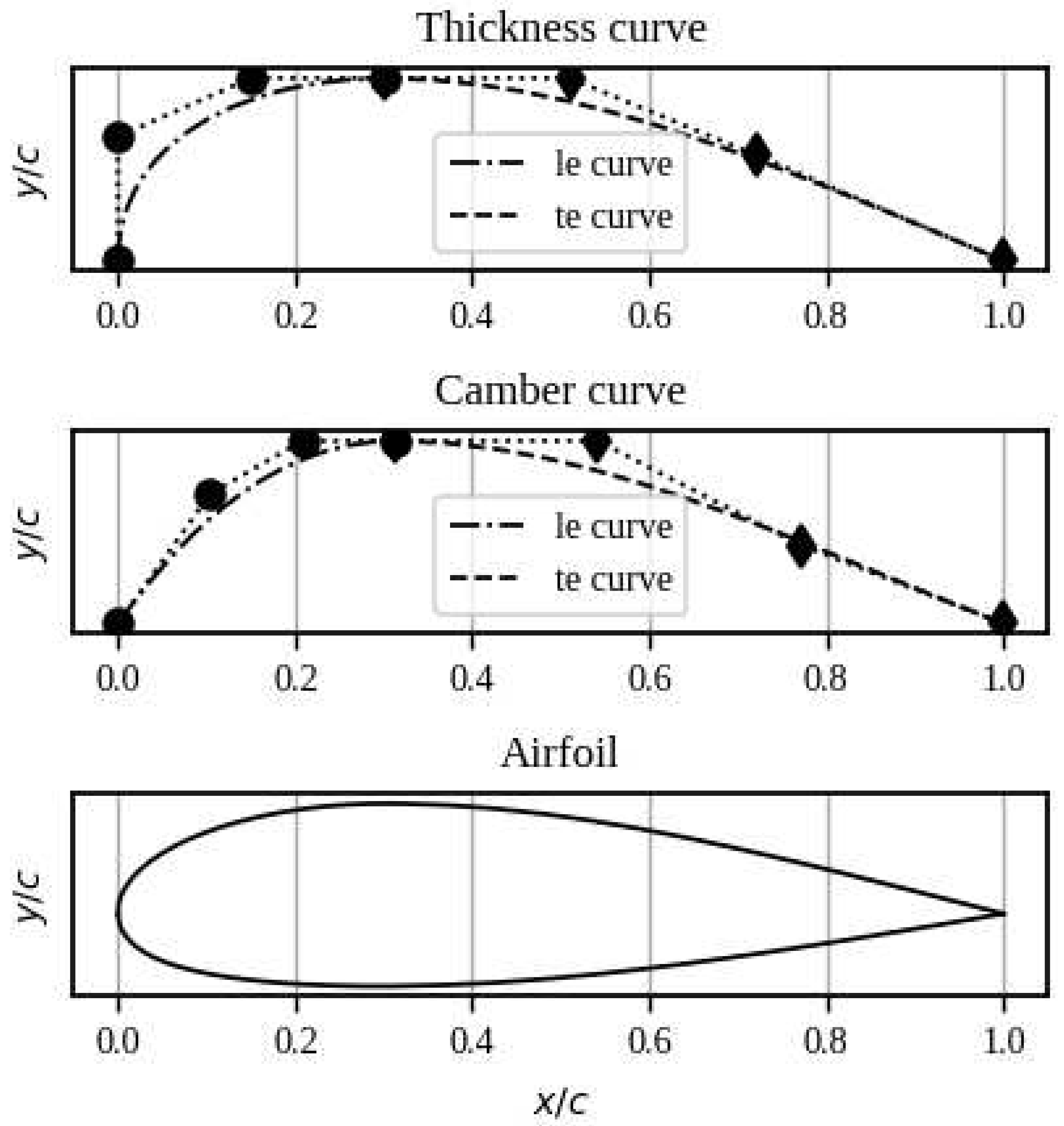

2.2. Selection Of Design Variables

- Root curve

- Tip curve

2.3. Model For The Resolution Of The Objective Function

| Algorithm 1: Subroutine for creation of the Bezier curves and airfoils |

|

, NS; Outputs: (c/d)i, αi, xti, yti, xci, yci, XU, YU, XL, YL; Get Xts,i and Yts,i with (8), (9), (10), (11), (15), (16); Get Xcs,i and Ycs,i with (8), (9), (12), (13), (17), (18); Get θs,i with (14); Create and save the points of the sth-airfoil XU, YU, XL, YL with (19), (20), (21), (22); |

| Algorithm 2: Modified ISM | ||

| Input n, B, V∞, d, ρ, ν, a, c, , [XU, YU, XL, YL], NS; | ||

| R = d/2; | ||

| Get ω with (33); | ||

| Get with (34); | ||

| for s = 1 to NS do | ||

| rs = R; | ||

| Get Res and Ms in each section; | ||

| cls, cds = runXFOIL(αs, [XU, YU, XL, YL]s, Res, Ms); | ||

| 0 →, 0→ | ||

| for l = 1 to 10 do | ||

| Iu = ⌀;; | ||

| for s = 1 to NS do | ||

| Get with (25); | ||

| Get with (26); | ||

| Get with (27); | ||

| Get with (28); | ||

| Get β1s with (29); | ||

| Φs = αs + β1s; | ||

| Ks = cls/cds; | ||

| Get σs with (30); | ||

| Get with (31); | ||

| Get frs with (32); | ||

| Update with (33); | ||

| →; | ||

| fors = 1 to NS do | ||

| Get with trapz(Iu[s:end], [s:end]); | ||

| fors = 1 to NS do | ||

| Get with (34); | ||

| Get with (35); | ||

| ct = trapz(dct, ); | ||

| mk = trapz(dmk, ); | ||

| Get αp, βp and λp with (38), (39) and (40) respectively; | ||

| Get outputs T, W, ηd, and ηs with (36), (37), (41) and (42) respectively; | ||

2.4. Optimization Algorithm

| Algorithm 3: Memory update algorithm in SHADE | ||

| IfSCR ≠ ∅ and SF ≠ ∅ then | ||

| If MCR,k,g = -1 ormax(SCR) = 0 then | ||

| MCR,k,g+1 = -1; | ||

| else | ||

| MCR,k,g+1 = meanWL(SCR); | ||

| MF,k,g+1 = meanWL(SF); | ||

| k++; | ||

| If k > Hthen, k = 1; | ||

| else | ||

| MCR,k,g+1 = MCR,k,g; | ||

| MF,k,g+1 = MF,k,g; | ||

- Exhaustion-based criteria: Due to limited computational resources optimization run might be terminated after a certain generation, number of objective function evaluations or CPU time. Commonly, a maximum number of generations or number of objective function evaluations is used in combination with every stopping criterion to prevent the algorithm from running forever if a criterion is not able to stop the run.

- Distribution-based criteria: For DE algorithms all individuals converge to the optimum eventually. Therefore, it can be concluded that convergence is reached when the individuals are close to each other. Because is assumed that the optimum is not known as for the reference criterion, the distances between the population members are examined. This type of criterion can be applied in the design space or in the objective space.

| Algorithm 4: OpenVINT algorithm | |||

| // Initialization phase | |||

| Input the design constants d, V∞, ρ, ν, a, Tmin, , NS; | |||

| Input the design variables intervals [Xmin, Xmax]; | |||

| Input the optimization conditions G, NP, NPmin, ε, U*, γ, H, p, g=1; | |||

| Initialize of metrics; | |||

| Initialize population Pg with LHS; | |||

| //Parallelized loop by joblib | |||

| for i = 1 to NP do | |||

| Apply Algorithm 1 for xi,g; | |||

| //Parallelized loop by joblib | |||

| for i = 1 to NP do | |||

| Get T(xi,g), W(xi,g), ηd(xi,g), ηs(xi,g) with Algorithm 2; | |||

| Get ψ(xg) with (2) and L(xg) with (1); | |||

| Update U*; | |||

| Save Lavg(xg); | |||

| Save data of generation g; | |||

| Set all values in MCR, MF to 0.5; | |||

| Archive A = ∅; | |||

| k = 1; | |||

| // Main loop | |||

| for g = 1 to G do | |||

| SCR = ∅, SF = ∅; | |||

| for i = 1 to NP do | |||

| ri = select from [1, H] randomly; | |||

| Get CRi,g; | |||

| Get Fi,g; | |||

| Get mutation vector vi,g; | |||

| Get trial vector ui,g; | |||

| //Parallelized loop by joblib | |||

| for i = 1 to NP do | |||

| Apply Algorithm 1 with ui,g; | |||

| //Parallelized loop by joblib | |||

| for i = 1 to NP do | |||

| Get T(ui,g), W(ui,g), ηd(ui,g), ηs(ui,g) with Algorithm 2; | |||

| Get ψ(ug) with (2) and L(ug) with (1); | |||

| Update U*; | |||

| for i = 1 to NP do | |||

| if L(ui,g) ≤L(xi,g) then | |||

| xi,g+1 = ui,g; | |||

| xi,g→ A; | |||

| CRi,g→ SCR, Fi,g→ SF; | |||

| else | |||

| xi,g+1 = xi,g; | |||

| Update memories MCR and MF with Algorithm 3; | |||

| Save Lavg(xg+1); | |||

| if g≥ 3 then | |||

| Get Δg and Δg-1 with (48); | |||

| Get NPg+1 with (46); | |||

| if NPg+1<NPmin then | |||

| Apply (47); | |||

| (NPg – NPg+1)-th worst vectors → A; | |||

| Remove the (NPg – NPg+1)-th worst vectors from Pg+1; | |||

| Save data of generation g+1; | |||

| if |Lavg(xg+1) – Lopt(xg+1)| ≤ε then | |||

| break; | |||

| k++; | |||

| Print metrics plots; | |||

| Output xopt, L(xopt); | |||

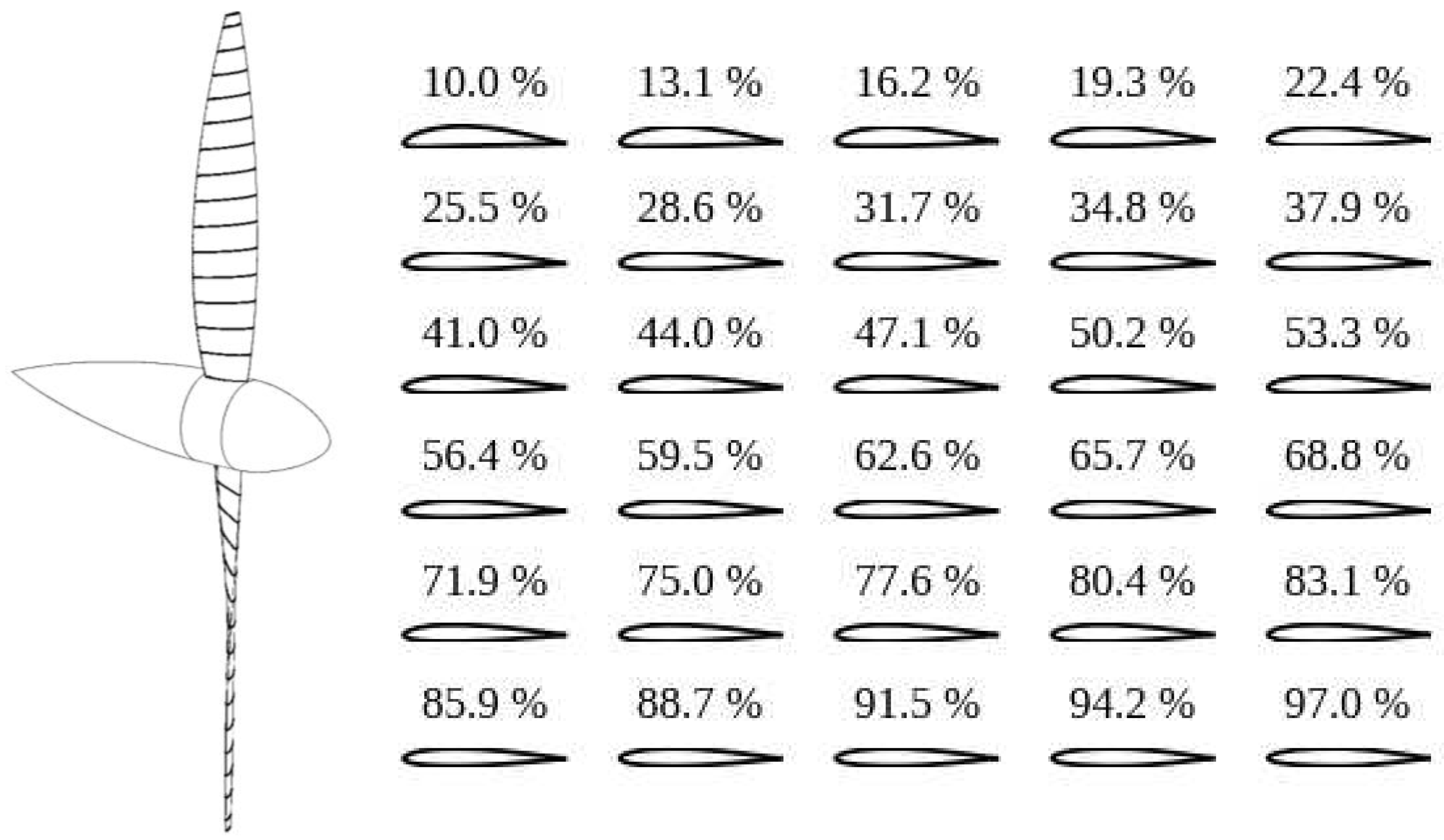

| Drawing the optimal propeller in point clouds; | |||

3. Study Case

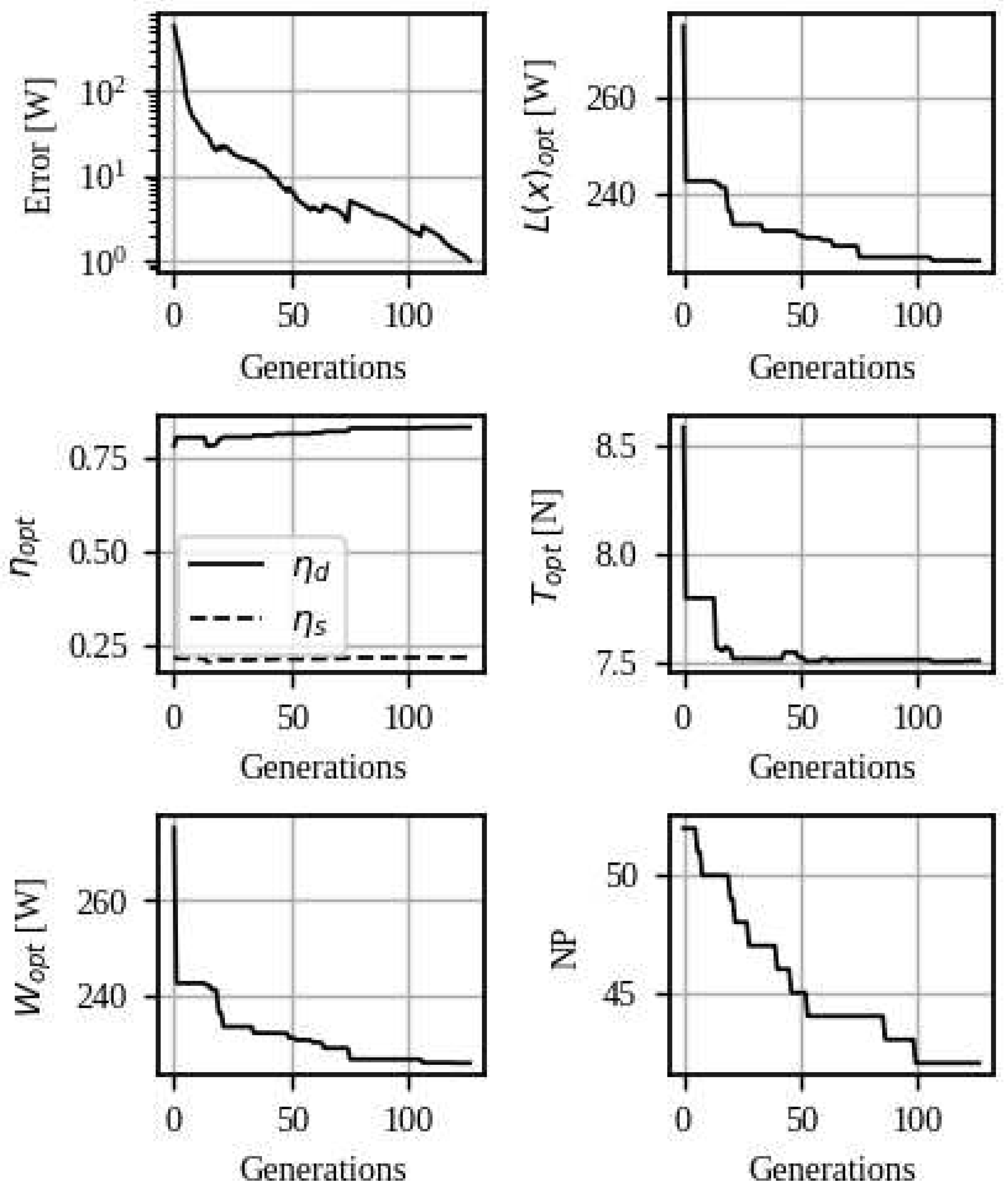

- in real optimization problems it is considered to use at least 50 individuals in the initial population, and as a minimum population 10 individuals were considered;

- the stop conditions contemplated for this case were, a maximum number of evaluated generations of 200, an ε value of 1 W to fulfill the condition indicated in line 48 of algorithm 4;

- a γ factor of 50 was used in equation 64;

- finally, an initial U*-value of 100 W was considered.

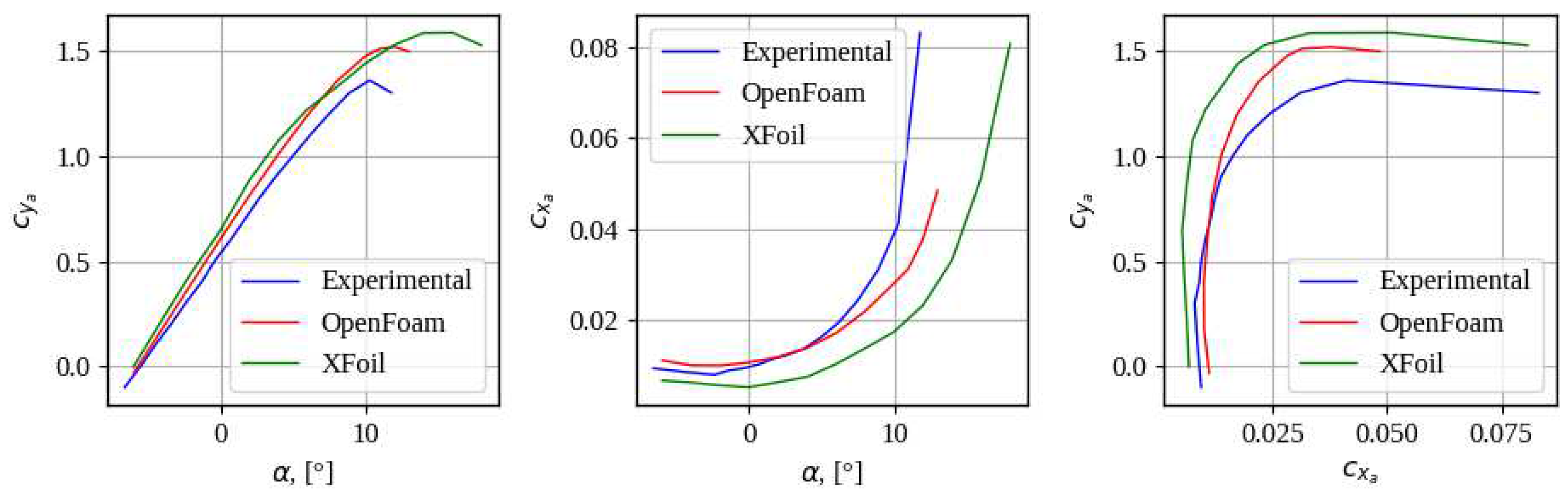

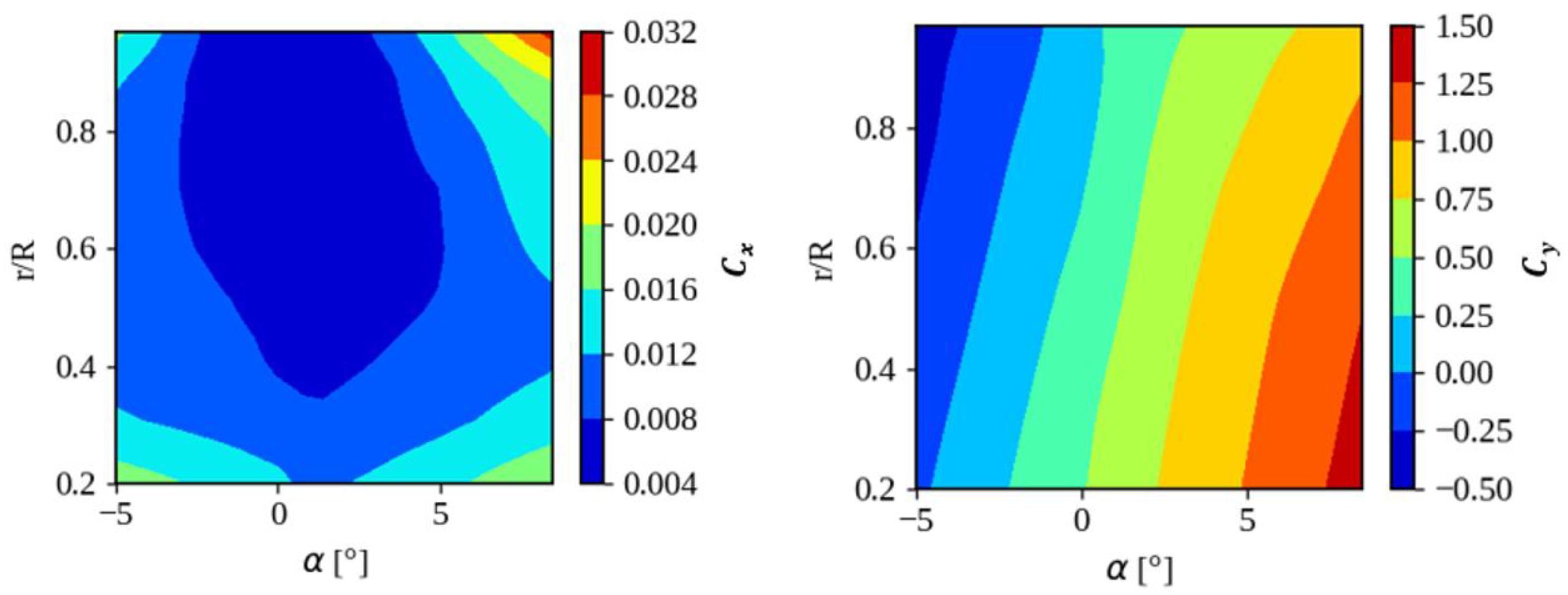

4. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Traub, L.W. Considerations in optimal propeller design. Journal of Aircraft 2021, 58, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, A. Introduction to the Theory of Flow Machines. Oxford: Pergamon Press 1966.

- Betz, A. Schraubenpropeller Mit Geringstem Energieverlust (Screw Propeller with Least Energy Loss). Akademie der Wissenschaften in Gottingen, Germany 1919, pp. 193–217.

- Adkins, C.N.; Liebeck, R.H. Design of optimum propellers. J Propul Power 1994, 10, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B R. Design of Aircraft Aerodynamic Configuration. Beijing: Chinese Aviation Industry Press 1997, pp. 97–130. [CrossRef]

- Colozza, A. High altitude propeller design and analysis overview. NASA/CR 98-208520. 1998.

- Morgado, J.; Abdollahzadeh, M.; Silvestre, M.A.R.; et al. High altitude propeller design and analysis. Aerosp Sci Technol 2015, 45, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, O.; Rosen, A. Optimization of Propeller Bases Propulsion Systems. Journal of Aircraft, 2009, 46, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfling, J.; Rokhsaz, K. Constrained and Unconstrained Propeller Blade Optimization. Journal of Aircraft, 2015, 52, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Peng, J.; Bai, J.; Han, X.; Song, X. Aeroacoustic and Aerodynamic Optimization of Propeller Blades. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2020, 33, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, S. An Energy Efficiency Optimization Method for Fixed Pitch Propeller Electric Aircraft Propulsion Systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, E.G.; Nicklow, J.W. Multi-objective automatic calibration of SWAT using NSGA-II. J Hydrology 2007, 341, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhong, B.W.; Liu, P.Q. Optimization design study of low-Reynolds-number high-lift airfoils for the high-efficiency propeller of low-dynamic vehicles in stratosphere. Sci China Technol Sci 2010, 53, 2792–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Song, B.-F.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Li, Y.-B. Optimal design and experiment of propellers for high altitude airship. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2017, 232, 1887–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munguia, J.; Van Treuren W. Designing small propellers for optimum efficiency. Baylor University, Waco, TX, 76798, 27 p.

- Ali, M.M.; Zhu, W.X. A penalty function-based differential evolution algorithm for constrained global optimization. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2013, 54, 707–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierret, S.S.; Van den Braembussche, R.A. Turbomachinery Blade Design Using a Navier-Stokes Solver and Artificial Neural Net-work. Journal of Turbomachinery 1999, 121, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovkov, A.I.; Voinov, I.B.; Ibraev, D.F. Determination of the Optimal Aerodynamic Shape for a Propeller Blade Based on Parametric Optimization. Izv. VUZ. Aviatsionnaya Tekhnika 2021, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van To, T.; Ngoc Phien, H. Development of Bezier-based curves. Computers in Industry 1992, 20, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zherejov, V.V.; Kusumov A.N. Aehrodinamicheskij raschet nesushchego vinta vertoleta uch posobie po kursovomu i diplomnomu proektirovaniyu (in rus). Russia, Kazan: KGTU 1997, 28 p.

- Derksen, R.W.; Rogalsky, T. Bezier-PARSEC: An optimized aerofoil parameterization for design. Advances in Engineering Software, 2010, 41, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravec, A.S. Kharakteristiki vozdushnykh vintov (in rus). Uchebnoe posobie, Gos. Izd. oboronnoj promyshlennosti, Moscow 1941.

- Eltaeib, T.; Mahmood, A. Differential Evolution: A survey and analysis. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Improving the search performance of SHADE using linear population size reduction. IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) 2014, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.; Liu, W.; Ho, C.H.; Ding, X. Continuous adaptive population reduction (CAPR) for differential evolution optimization. SLAS Technology 2017, 22, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iman, R.L. Encyclopedia of quantitative risk analysis and assessment. John Wiley & Sons 2008, pp. 408-411.

- Zielinksi, K.; Weitkemper, P.; Laur, R.; Kammeyer, K.D. Examination of stopping criteria for differential evolution based on a power allocation problem. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:13358798 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Sharma, H. Lightweight pipelining in Python. Using Joblib for storing the machine learning pipeline to a file. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/lightweight-pipelining-in-python-1c7a874794f4 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

| Variable | Interval | Variable | Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| (c/d)r | [0.03, 0.10] | xtt | [0.30, 0.45] |

| (c/d)m | [0.03, 0.10] | r̅xtm | [0.30, 0.80] |

| (c/d)t | [0.01, 0.02] | ycr | [0.01, 0.05] |

| r̅cm | [0.35, 0.60] | ycm | [0.01, 0.05] |

| αr | [-7, 7] ° | yct | [0.005, 0.05] |

| αm | [-5, 7] ° | r̅ycm | [0.30, 0.80] |

| αt | [-5, 7] ° | xcr | [0.30, 0.40] |

| r̅αm | [0.25, 0.75] | xcm | [0.30, 0.45] |

| ytr | [0.12, 0.20] | xct | [0.30, 0.45] |

| ytm | [0.12, 0.16] | r̅xcm | [0.30, 0.80] |

| ytt | [0.10, 0.12] | nm | [5e3, 10e3] rev/min |

| r̅ytm | [0.30, 0.80] | B | [2, 4] |

| xtr | [0.30, 0.40] | d | [0.3, 0.3] m |

| xtm | [0.30, 0.45] |

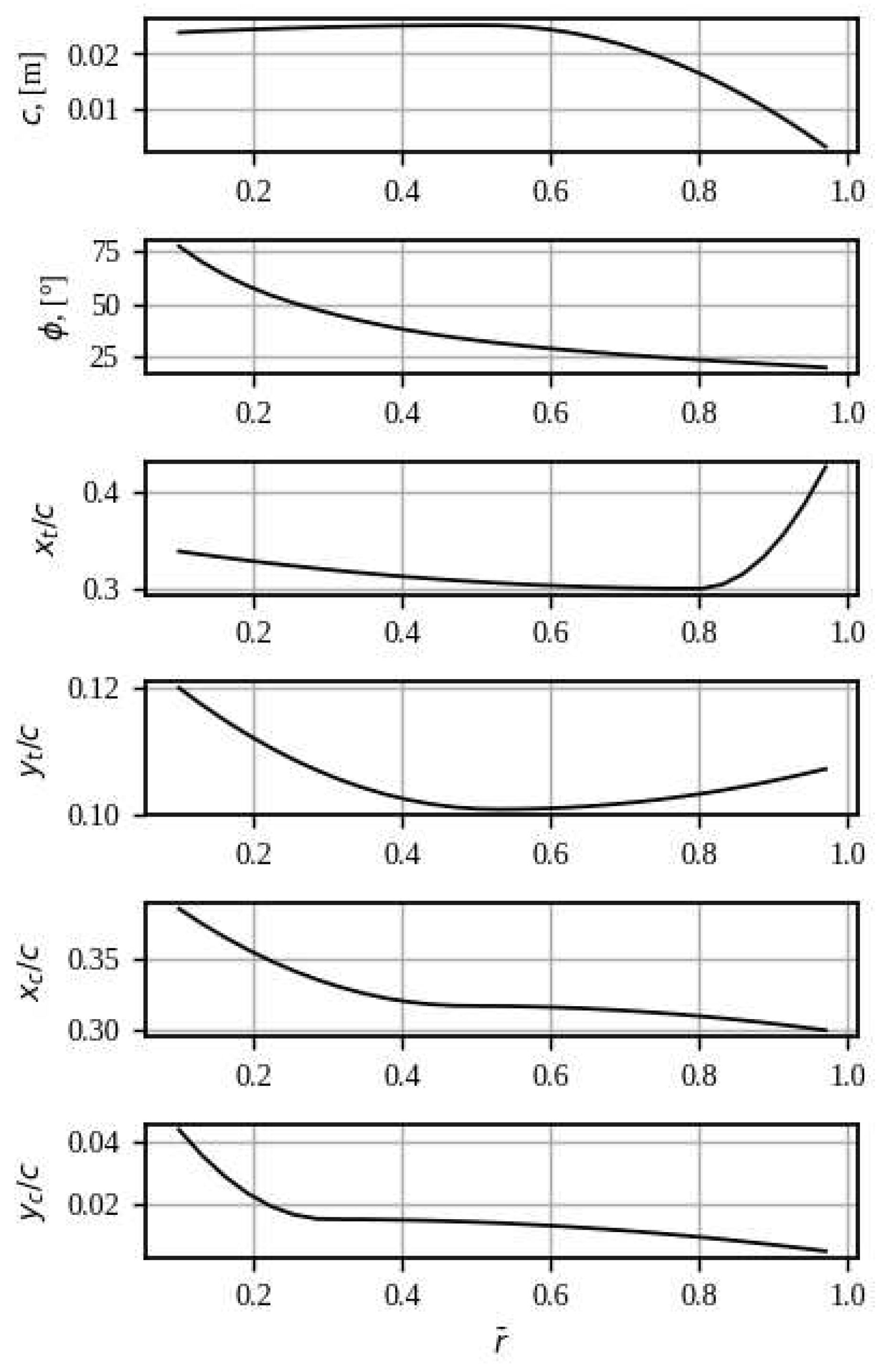

| Variable | Value | Variable | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (c/d)r | 0.0798405 | xtt | 0.42644 |

| (c/d)m | 0.0842341 | r̅xtm | 0.8 |

| (c/d)t | 0.010028 | ycr | 0.0439051 |

| r̅cm | 0.513672 | ycm | 0.0152008 |

| αr | 7 ° | yct | 0.005 |

| αm | 4.71326 ° | r̅ycm | 0.3 |

| αt | 5.23632 ° | xcr | 0.385744 |

| r̅αm | 0.2543 | xcm | 0.317216 |

| ytr | 0.12 | xct | 0.3 |

| ytm | 0.1007486 | r̅xcm | 0.487034 |

| ytt | 0.1071704 | nm | 6896.51 rev/min |

| r̅ytm | 0.52874 | B | 2 |

| xtr | 0.338746 | d | 0.3 m |

| xtm | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).