1. Introduction

Phialemonium (Sordariales: Cephalothecaceae) is a cosmopolitan fungus belonging to the phylum Ascomycetes. It is found in various natural environments, including air, soil, sewage, plants, and water [

1]. Several species of the

Phialemonium genus cause opportunistic human infections; however, unlike these species,

P. inflatum promotes plant growth [

2] and its leaf endophytes protect seedlings against root-knot nematode infection [

3,

4]. Furthermore,

P. inflatum reportedly mineralises lignin during primary metabolism [

5], indicating its ability to degrade lignin-like recalcitrant polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Despite the potential usefulness of

P. inflatum, a transformation system to explore gene functions for biological applications is lacking.

Various transformation techniques have been developed for the gene manipulation and functional analysis of fungi including the protoplast-mediated transformation and electroporation [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT) can be applied to budding yeast [

11,

12,

13] as well as filamentous fungi [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. It has the advantage of producing transformed organisms simply by mixing

Agrobacterium cells with asexual spores, mycelia, and even fruiting bodies, without physically removing the cell wall or using cell wall-degrading enzymes. Furthermore, because the Ti-plasmid is randomly integrated into fungal genomes, it provides an advantage in forward genetics [

6,

14,

19,

24].

To apply the ATMT transformation system to fungi, several conditions must be considered [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Firstly, provided the ATMT technique is applicable to the target fungus, the next step is to determine the optimal transformation conditions. The first condition to consider is acetosyringone (AS) application, which may not be necessary for certain fungi [

29,

30]. Additionally, the number of fungal spores and

Agrobacterium cells during co-cultivation can affect the number of resulting transformed cells [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Another factor to consider is the duration of co-cultivation, because a supraoptimal duration can result in additional T-DNA insertions [

27,

28]. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the optimal conditions to establish ATMT in a specific fungus by evaluating these factors.

In this study, we aimed to establish an efficient P. inflatum genetic manipulation system using ATMT, and report an optimised transformation protocol for P. inflatum using strain BCC-F1546, isolated from an aquatic fungus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal strains, growth media, culture conditions, and hygromycin B sensitivity

The wild-type P. inflatum strain BCC-F1546 used in this study was obtained from the Nakdonggang National Institute of Biological Resources, Sangju, Korea. The wild-type stain and its transformants were cultured at 25°C under dark conditions on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco Laboratories) or in potato dextrose broth (PDB, Difco Laboratories). The wild-type strain, along with the transformants generated from it, were stored as spore suspensions in 15% glycerol at -80°C.

The bacterial strain

A. tumefaciens AGL-1, carrying the binary vector pSK1044, was used in this study [

28]. The bacterial strain was cultured at 28°C for two days in Luria Bertani (LB) broth (Difco Laboratories) and stored in 15% glycerol at -80°C.

To determine the optimal hygromycin B concentration for selecting transformants, wild-type P. inflatum strains were evaluated by dropping of 5 μL spore suspension (1×103/mL) on PDA amended with different hygromycin B concentrations (0, 20, 40, and 50 µg/mL). After incubating the PDA plates at 25°C for 10 days, colony growth was evaluated. This test was performed in triplicate.

2.2. ATMT of P. inflatum

The protocol for ATMT was based on previous studies [

27,

28,

31] with slight modifications to suit

P. inflatum. In brief,

A. tumefaciens cells were cultured at 28℃ for two days with shaking (150 rpm) in minimal medium (MM) [

31] containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml). To induce bacterial cells for fungal transformation, the cultured

A. tumefaciens cells were transferred to induction medium (IM) [

32] containing 200 μM AS following collection using centrifugation (5,000 rpm for 5 min.) for the 5 mL cell culture. The transferred bacterial cells in IM medium were cultured at 28℃ in a shaking incubator for 6 h.

For fungal transformation, conidia were obtained from the seven day-old PDA culture. After adding 5 mL of sterilised distilled water (SDW) to the PDA culture, the PDA surface with P. inflatum spores was gently scraped with a spatula and an additional 5 mL of SDW was added. To remove the mycelia, the harvested spore suspension was filtered through two layers of sterilised Miracloth. The spore suspension was then centrifuged (5,000 rpm for 5 min.) to remove the mycelia, and 10 mL of SDW was added, vortexed, and centrifuged again thrice to remove the mucilage on the spore surface. The prepared spores were counted using a haemocytometer. Before transformation, the prepared spores were diluted with 5 mL SDW.

For co-cultivation, 100 μL of P. inflatum spores (104, 105, 106, and 107) and 100 μL of induced A. tumefaciens cells (OD=0.6) were mixed and evenly spread onto cellulose membrane (cellulose nitrate, 47 mm diameter, and 0.45 μm pore, Whatman Ltd., Maidstone, UK) on co-cultivation medium amended with or without 200 µM AS.

After co-cultivation at 28°C for 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h, only cellulose membranes were transferred from the co-cultivation medium to selection media containing hygromycin B (50 µg/mL) and cefotaxime (250 µg/mL). One week after transfer, the mycelia that grew on the cellulose membrane were transferred to a 24-well plate (SPL, Korea) containing selection media with hygromycin B (50 µg/mL) and cefotaxime (250 µg/mL). For the transformants selected for the second time in this way, approximately 10 pieces of mycelia with a diameter of 5 × 5 mm were placed in a solution containing 15% glycerol and then cultured at 25°C for three days. The cultures were then stored at -80°C for long-term preservation.

2.3. Genomic DNA extraction and PCR analysis to confirm T-DNA insertion

Fungal genomic DNA was extracted from mycelia cultured in 5 mL PDB on a 6-well plate (SPL, Korea) at 25°C for one week. The grown mycelia from wild-type and transformants were harvested, freeze-dried, immersed in liquid nitrogen to freeze, and then prepared into fine powder using a Mini-Beadbeater-96 (1001, Biospec products). Genomic DNA was prepared using the NucleoSpin Plant kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to manufacturer instructions. The amount of extracted DNA was measured using a NanoDrop-1000 spectrophotometer.

2.4. Southern blot analysis

Southern blot analysis was performed to determine the copy number of inserted T-DNA in the transformants. Genomic DNA (2 µg) was digested with Hind III and separated by gel electrophoresis using a 0.7% agarose gel at 40 V for 4 h in 1% Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. The DNA fragments in the agarose gel were transferred to Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham International, Little Chalfont, England) using 20× SSC (1.5 M NaCl and 0.15 M sodium citrate) and then cross-linked the DNA fragment on Hybond N+ membrane via ultraviolet (UV).

For probe preparation for Southern blot analysis, the

hph gene was obtained by PCR amplification using pSK1044 [

28] as a template and the primers HygB_F (5′-TCAGCTTCGATGTAGGAGGG-3′) and HygB_R (5′-TTCTACACAGCCATCGGTCC-3′). The resulting fragments were labelled using a direct chemiluminescence labelling system via random priming (AlkPhos Direct

TM Labelling and Detection system, GE Healthcare).

Southern blot analyses and signal detection were performed using the AlkPhos DirectTM Labelling and Detection system (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications. Hybridisation was performed overnight at 55°C. Hybridised blots were washed twice with primary and secondary washing buffers according to manufacturer instructions. Signals were detected using the CDP-StarTM detection reagent, and the signal was exposed to hyperfilmTM ECL (GE Healthcare) for 2 h.

2.5. PCR amplification for transformant confirmation

PCR amplification of the hph and eGFP genes was performed using 20 ng genomic DNA and 10 pmol of each primer using the i-StarMAX II PCR master mix system (iNtRON Biotechnology Inc., Seongnam, Korea). For primers for hph gene amplification, HygB_F and HygB_R described above were used. For eGFP gene amplification, primers eGFP_F (5’-ATGGTGAGCAAGGGCG-3’) and eGFP_R (5’-TTACTTGTACAGCTCGTC-3’) were used. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94℃ for 3 min; 30 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 94℃, 30 s of annealing at 56℃, and 1 min of elongation at 72℃; finally, 5 min of elongation at 72℃ and maintenance at 4℃. The PCR products were confirmed by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel, stained with EcodyeTM DNA staining solution (Solgent Co. Daejeon, Korea), and visualised under UV light.

2.6. eGFP expression observation in transformants

Purified transformants via single spore isolates were observed using a Zeiss Axio Imager A1 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with the following filter settings: 470/40 nm excitation and 525/50 nm emission.

2.7. Identification of T-DNA insertion sites via inverse PCR

Inverse PCR (i-PCR) was performed to recover genomic sequences flanking each inserted T-DNA. A total volume of 7 μL (100 ng of genomic DNA) was placed in a PCR tube, and 2.3 μL of 10 × Taq I enzyme buffer (Takara, Tokyo, Japan), 2.3 μL of bovine serum albumin, and 11.1 μL of SDW were added. Finally, 2 units of Taq I restriction enzyme (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) were added to the PCR tube for a final volume of 23 μL. The melting temperature was set to 65 °C, the PCR tube was placed in the thermocycler, and then processed for 3 h.

To ligate the DNA, 5 μL was transferred to a new PCR tube. To each tube, 2 μL of 10 × T4 DNA ligase buffer (Takara, Tokyo, Japan), and 12.7 μL of SDW, 0.3 μL corresponding to 2 units of T4 DNA ligase (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) were added. The thermocycler was set to 4 °C, tubes were placed in the PCR machine, and were processed overnight.

After transferring 3 μL of self-ligated genomic DNA to new PCR tubes, 10 μL of i-Star MAXII mix was added to each tube. In addition, 1 μL each of 10 pmol/μL RB3 (5′-CCCTTCCCAACAGTTGCGCA-3′) and RBn1R (5′-TTTTCCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAA-3′) primers and 5.0 μL of sterilised distilled water were added to adjust the total volume to 20 μL to perform i-PCR.

PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 32 cycles of 94°C for 3 min, 94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min, followed by a final PCR step at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were confirmed on a 0.8% agarose gel. The PCR products obtained were sequenced and analysed for T-DNA insertion as previously described [

24].

2.8. Mitotic transformant stability

The mitotic stability of hygromycin B resistance of three randomly selected transformants was tested by growing them on PDA without hygromycin B for three generations at 25 °C. Finally, the growing mycelial edge of the colony was transferred to PDA containing 50 μg/mL hygromycin B.

2.9. Data analysis

Normal one-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analyses in this study, and the significance of differences among treatments was determined using Duncan’s multiple range test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Data shown are means ±standard deviation. Significance was defined at P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. ATMT establishment for P. inflatum

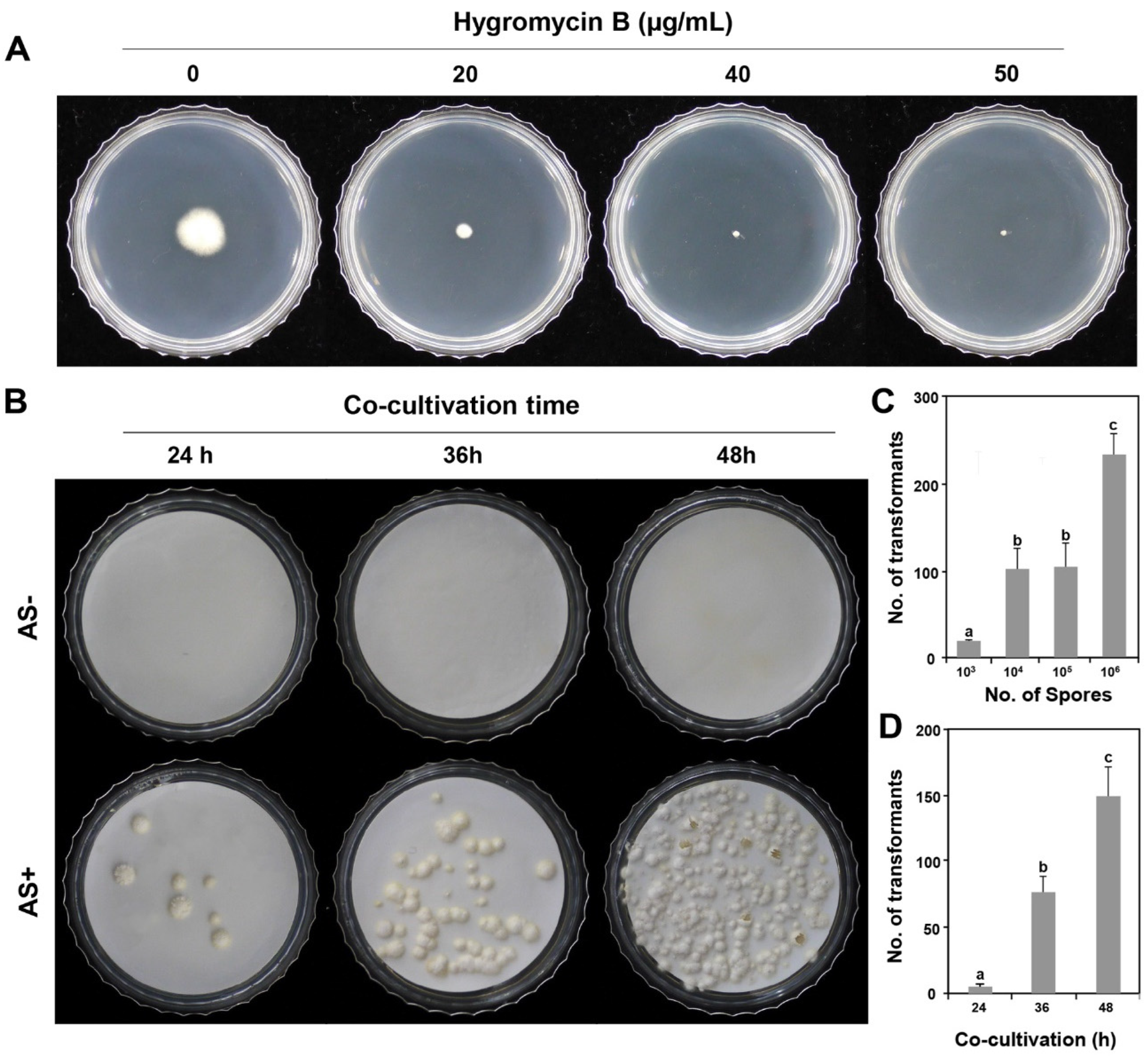

The

hph gene was used as a marker to select transformants. To use

hph as a selection marker, we determined the dosage of hygromycin B for the wild-type

P. inflatum FBCC-F1546 strain. When

P. inflatum was inoculated on PDA medium supplemented with 0, 20, 40, and 50 μg/mL hygromycin B, the wild-type fungal mycelia were completely inhibited at 50 μg/mL hygromycin B (

Figure 1A), indicating that the appropriate hygromycin B concentration was 50 μg/mL to screen for

P. inflatum transformants.

ATMT may only be possible when AS is absent in some fungi or present in others [

29,

30]. Here, we tested whether the presence or absence of AS affects the efficiency of ATMT in

P. inflatum. As shown in

Figure 1B, 200 µM AS was essential for the ATMT of

P. inflatum during the induction stage of

A. tumefaciens and the subsequent co-cultivation stage.

To determine the appropriate number of spores for efficient transformation, we used different numbers of spores. When 1 × 10

3 spores per plate were used for ATMT, 19.0 ± 1.0 transformants were generated. In addition, when 1 × 10

4 and 10

5 spores were added to each plate, 101. 3 ± 23.8 and 103. 7 ± 27.2 transformants were generated, respectively, which is approximately five times more than when 1 × 10

3 spores were seeded per plate. The highest number of transformants was produced when 1 × 10

6 spores were applied, which was twice as many as when 1 × 10

4 or 10

5 spores were used (

Figure 1C). The results showed that to maximise the transformation efficiency of

P. inflatum, the largest number of transformants could be obtained when 1 × 10

6 spores were applied.

Next, to determine the effect of co-culture time on ATMT, we divided the co-culture time into 24, 36, and 48 h. The same number of spores (1 × 10

5) was used per plate. As a result, 5.3 ± 2.1, 77.0 ± 12.0, and 149.0 ± 21.9 transformants were obtained when co-cultured for 24, 36, and 48 h, respectively (

Figure 1D). These results indicated that 48 h was the optimum co-cultivation time for obtaining the largest number of transformants.

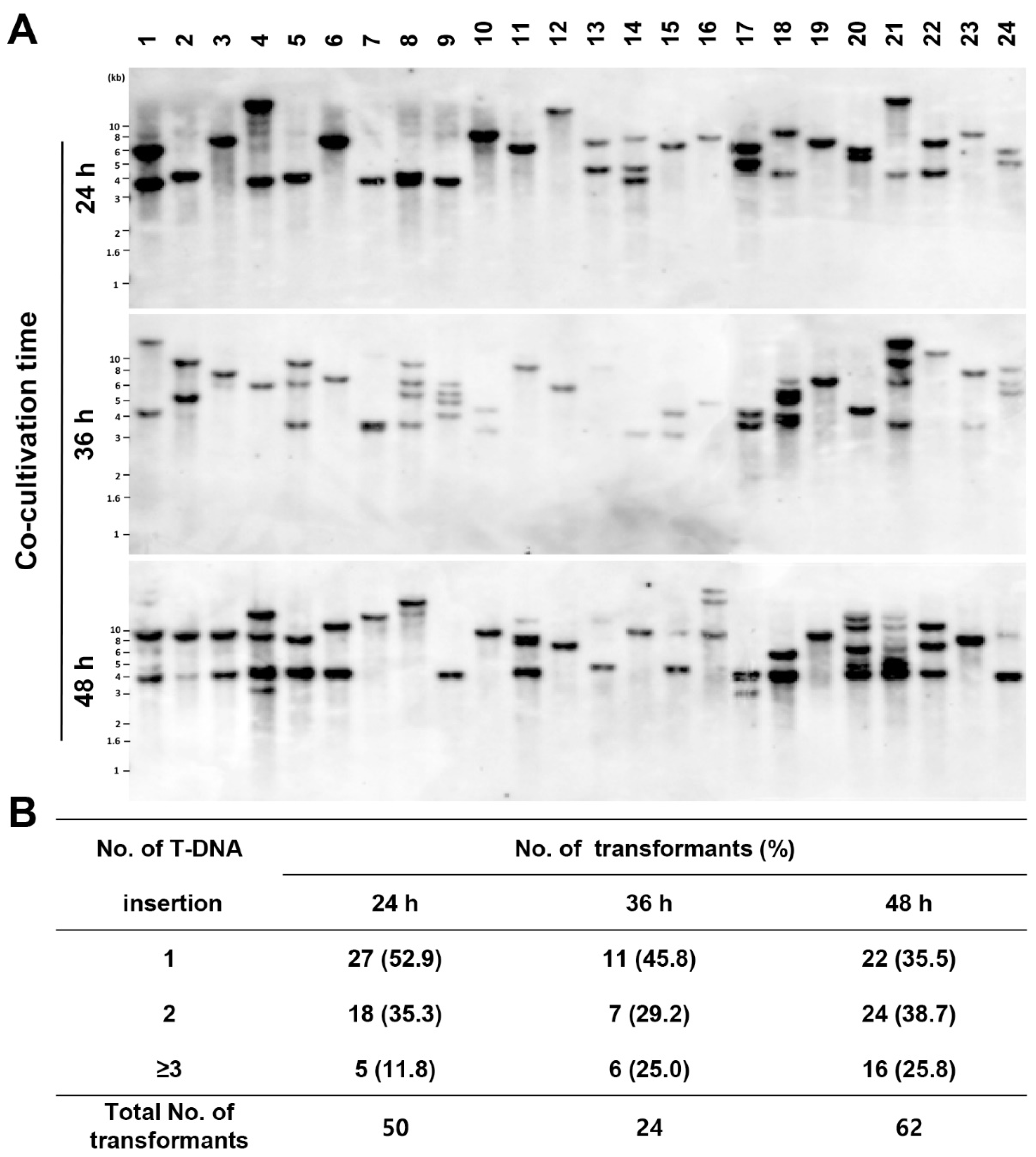

3.2. Analysis of T-DNA insertion among the generated transformants

We showed that the number of transformants increased with increasing co-cultivation time (

Figure 1D). However, this result does not indicate that T-DNA is preferentially integrated as a single copy into the

P. inflatum genome. To determine the effect of co-cultivation time, we randomly selected 24 transformants from each of the co-culture time points (24 h, 36 h, and 48 h) and confirmed the number of T-DNA insertions by Southern blot analysis (

Figure 2A). Single-copy T-DNA integration was confirmed to be 52.9%, 45.8%, and 35.5% after 24, 36, and 48 h under co-cultivation, respectively (

Figure 2B). This result indicated that co-cultivation for 24 h was sufficient to obtain single-copy T-DNA integration in

P. inflatum.

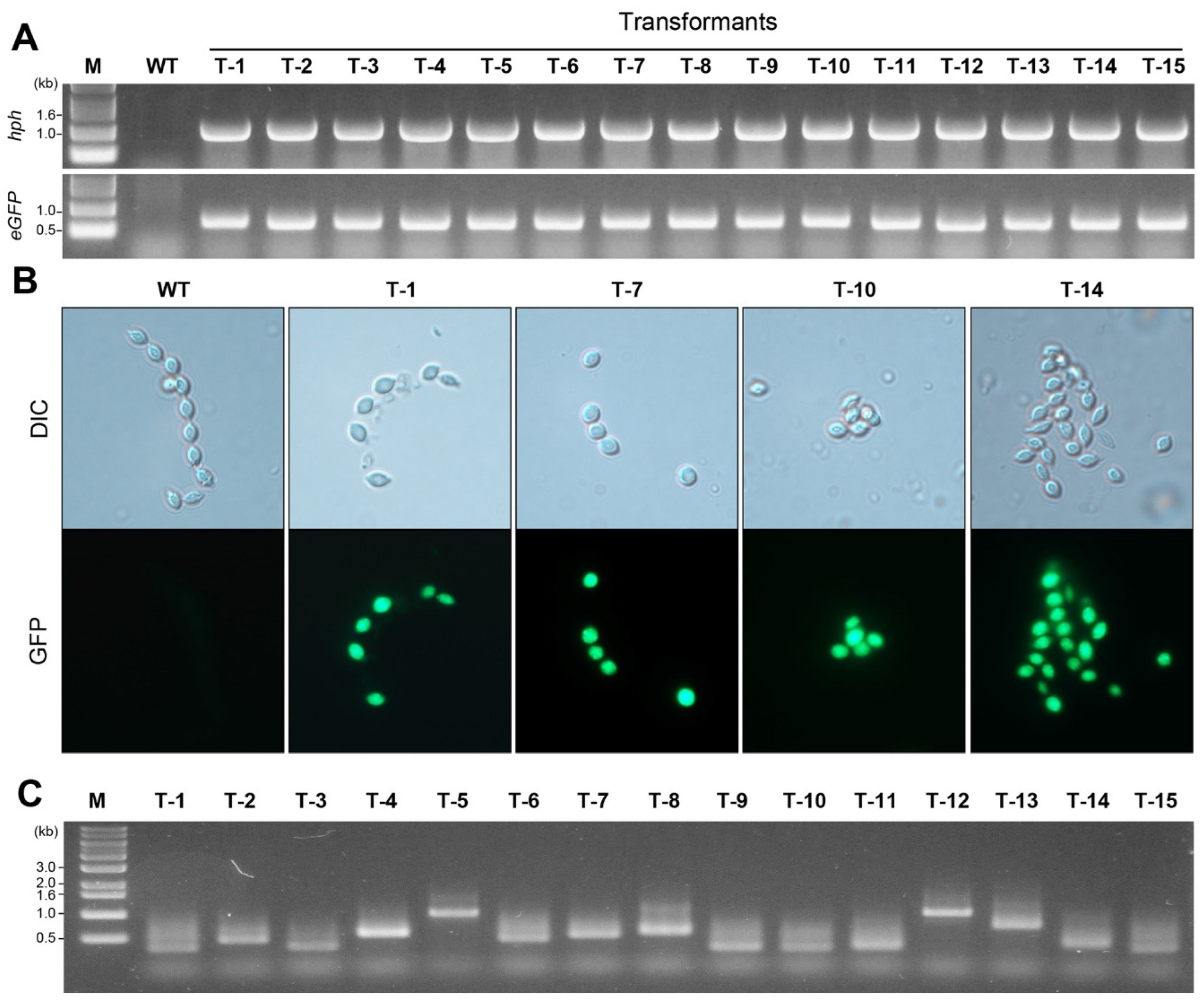

3.3. Confirmation of the integration of the hph and eGFP genes in the P. inflatum genome

It is important to confirm the presence of both the

hph and

eGFP genes carried by T-DNA in the genome of

P. inflatum using PCR amplification. In this study, we randomly selected 15 transformants to identify the genes in their genomes. In the wild-type, neither

hph (

Figure 3A upper picture) nor

eGFP (

Figure 3B lower gel picture) was amplified, whereas in transformants, both genes (1 kb for the

hph gene and 0.7 kb for the

eGFP gene) were amplified, indicating that all 15 randomly selected transformants were T-DNA inserted transformants.

Green fluorescence under a microscope was used to identify transformants. All 15 transformants were examined for eGFP expression under a fluorescence microscope. Strong green fluorescence was observed in all the transformants, whereas no fluorescence was detected in the wild-type.

Figure 3B shows the blight-field (DIC mode) and GFP observations from four representative transformants (T-1, T-7, T-10, and T-14) and the wild-type.

3.4. Identification of genomic sequences flanking inserted T-DNA in the generated transformants

I-PCR and subsequent sequencing were performed to identify the genomic location of the T-DNA insertion in the 15 selected transformants. After i-PCR, agarose gel analysis showed PCR products of different size, ranging between 0.3–1 kb (

Figure 3C). Sequence comparison among the 15 flanking regions suggested that the T-DNA was randomly inserted without preferential sequence contexts (

Table 1). Truncated T-DNA was not detected in any of the 15 randomly selected transformants (

Table 1).

3.5. Stability of transformants in P. inflatum

We assessed the mitotic stability of transformants after subculturing randomly selected transformants (T-1, T-7, and T14 in

Figure 3B) for three rounds on medium in PDA without hygromycin B. Finally, we transferred the hygromycin B-resistant transformants to medium containing hygromycin B (50 µg/mL). All three transformants maintained resistance to hygromycin B, suggesting that the inserted T-DNA was mitotically stable.

4. Discussion

In order to harness the valuable fungi for large-scale industrial processes, molecular genetic tools are essential. Indeed, various products are being produced from commercially utilized

Aspergillus niger,

A. oryzae, and

A. sojae. The main substances include glucoamylase, citric acid, cellulose, protease, and kojic acid [

33]. These industrial products are used in food, beverages, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics, among other applications. It is important to establish a genetic transformation system in order to obtain fungal strains with higher efficiency for the production of these products. However, the transformation efficiency is generally low in filamentous fungi [

34]. In particular, the application of the transformation technique via polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated protoplast transformation, restriction enzyme-mediated integration (REMI) with protoplasts is unsuccessful if the fungal cell wall is not sufficiently digested. ATMT has been successfully applied for the genetic transformation of a wide variety of fungal species including industrial fungi (

Saccharomyces cerevisiae,

Trichoderma reesei, and

Aspergillus spp.), mushrooms (

Pleurotus eryngii,

Agaricus bisporus,

Coprinopsis cinereus, and

Volvariella volvacea), and plant pathogenic fungi (

Magnaporthe oryzae,

Fusarium verticillioides,

F. oxysporum, and

Verticillium dahliae) [

23,

26,

35].

The fungus

P. inflatum has tremendous potential to produce very useful metabolites, with nematocidal, plant growth promotion, and PAH degradation activities [3-5]. Especially, the capability of degrading PAHs such as lignin and phenanthrene has been known to be present in white rot fungi (

Trametes versicolor,

Lentinula edodes, and

Phanerochaete chrysosporium) [

5]. Kluczek-Turpeinen et al. reported that

P. inflatum can produce laccases without peroxidase activity [

5]. Development of transformation system for

P. inflatum may help us to understand the production of various useful substances within this fungus. Because no transformation system was available for any

P. inflatum strain, the primary aim of this study was to develop a

P. inflatum transformation system.

We successfully developed and applied a transformation method to the conidia of

P. inflatum via the ATMT method and generated 3,689 hygromycin-resistant transformants that stably maintained the resistant cassette. In the previous study, uninucleate conidia in filamentous fungi have been considered more suitable for transformation than multinucleate conidia [

28]. We observed that conidia of

P. inflatum produce a relatively high number of transformants within a short co-cultivation time compared to other fungi [15,19-21,36-40]. Possibly, the insertion of T-DNA from ATMT may have occurred more rapidly and easily in

P. inflatum, which has single-nucleate conidia, compared to other fungi with multinucleated conidia.

ATMT has not been previously used in this fungus as a tool for insertional mutagenesis. Thus, the T-DNA from the binary vector pSK1044 was efficiently transformed and correctly expressed in the genome. Previous studies on ATMT in ascomycetous fungi reported that T-DNA insertion prefers single-copy integration [

14,

25,

26]. This finding suggests that ATMT is a useful transformation strategy in forward genetics [

6,

14,

24,

25,

41]. If the number of available transformants with a higher probability of single-copy integration increases, this will be the optimal condition for ATMT of the target fungi. As shown in

Figure 1D, the yield of transformants was highest after 48 h of co-cultivation and was > 30 times higher than that after 24 h of co-cultivation. Such short co-cultivation period results in a lower number of transformation events compared to 36, 48, or 72 h [

13,

14,

28,

29,

37,

42,

43].

Regardless of transformation efficiency rate, the phenotype of a gene deletion-mutation cannot be accurately tested when gene replacement is performed through homologous recombination via ATMT, as extra copies of T-DNA may be inserted into the genome, potentially interfering with major traits. Thus, it was necessary to reduce the co-cultivation time to < 24 h to increase single-copy T-DNA insertion (

Figure 2B). As shown in

Figure 2B, the probability of single-copy T-DNA insertion after 48 h decreased by 17% compared to that after 24 h. Our data imply that functional genomic studies on

P. inflatum should be conducted under co-cultivation conditions of < 24 h to prevent the insertion of extra copies of T-DNA. Because the genome of

P. inflatum FBCC-F1546 is currently being sequenced, we will use the optimal ATMT protocol developed here for the functional genetic analysis of

P. inflatum.

We found that both exogenous genes,

hph and

eGFP, were effectively expressed in

P. inflatum. We also found that transformants with

hph and

eGFP gene expression under the control of the

Aspergillus nidulans trpC and

Cochliobolus heterostrophus GAPD promoters, respectively, exhibited stable and constitutive expression in this fungus. This result demonstrates that both promoters can be used to express genes of interest in this fungus. Although two promoters have been conventionally used for gene overexpression, including genes that are generally expressed at low levels in a number of ascomycetous fungi [

7,

44,

45], our data clearly indicated that these two promoters can be used for the overexpression of

P. inflatum.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to establish an efficient transformation system for

P. inflatum to facilitate molecular genetic studies. We demonstrated that the ATMT method could be successfully applied to

P. inflatum. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of genetic

P. inflatum transformation via

Agrobacterium. Unlike previous studies [

13,

14,

28,

29,

37,

42,

43], the optimal conditions for single-copy T-DNA integration in

P. inflatum were established. These conditions required a 24 h co-cultivation time with AS (200 µM) and 1 × 10

6 spores per 5 cm plate. In addition, we successfully expressed the

hph and

eGFP genes in

P. inflatum under the

A. nidulans trpC and

C. heterostrophus GAPD promoters, respectively. Ultimately, our findings will assist functional genetic analysis of

P. inflatum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and S.-Y.P.; methodology, S.-Y.P.; validation, J.Y., Y.K., H.J, and S.-Y.P.; formal analysis, J.Y., Y.K., H.J, M.-H.J., S.-H.J., S.K., J.P., M.J., S.A., and J.P.; investigation, J.Y., Y.K., H.J, M.-H.J., S.-H.J., S.K., J.P., M.J., S.A., and J.P.; resources, S.P. and J.G.; data curation, S.-Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G. and S.-Y.P.; writing—review and editing, J.G. and S.-Y.P.; visualization, J.Y., Y.K., H.J., and M.-H.J.; supervision, J.G. and S.-Y.P.; project administration, J.G. and S.-Y.P.; funding acquisition, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through a project to make multi-ministerial national biological research resources a more advanced program funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (2021003420003).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Perdomo:, H.; Garcia, D.; Gene, J.; Cano, J.; Sutton, D.A.; Summerbell, R.; Guarro, J. Phialemoniopsi, a new genus of Sordariomycetes, and new species of Phialemonium and Lecythophora. Mycologia 2013, 105, 398–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Vega, L.J.; Grunseich, J.M.; Aguirre, N.M.; Valencia, C.U.; Sword, G.A.; Helms, A.M. A beneficial plant-associated fungus shifts the balance toward plant growth over resistance, increasing cucumber tolerance to root herbivory. Plants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.B.; Simoneau, P.; Barret, M.; Mitter, B.; Compant, S. Editorial special issue: the soil, the seed, the microbes and the plant. Plant Soil 2018, 422, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wheeler, T.A.; Starr, J.L.; Valencia, C.U.; Sword, G.A. A fungal endophyte defensive symbiosis affects plant-nematode interactons in cotton. Plant Soil 2018, 422, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczek-Turpeinen, B.; Tuomela, M.; Hatakka, A.; Hofrichter, M. Lignin degradation in a compost environment by the deuteromycete Paecilomyces inflatus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 61, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.; Park, S.Y.; Chi, M.H.; Choi, J.; Park, J.; Rho, H.S.; Kim, S.; Goh, J.; Yoo, S.; Park, J.Y.; et al. Genome-wide functional analysis of pathogenicity genes in the rice blast fungus. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, M.H.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.H. A novel pathogenicity gene is required in the rice blast fungus to suppress the basal defenses of the host. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthachalam, K.; Klosterman, S.J.; Kang, S.; Hayes, R.J.; Subbarao, K.V. Identification of pathogenicity-related genes in the vascular wilt fungus Verticillium dahliae by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated T-DNA insertional mutagenesis. Mol. Biotechnol. 2011, 49, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, R.; Gao, N.; Lv, J.; Ji, C.; Liang, H.; Li, S.; Yu, C.; Wang, Z.; Lin, X. Enhancement of torularhodin production in Rhodosporidium toruloides by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation and culture condition optimization. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debler, J.W.; Henares, B.M. Targeted disruption of scytalone dehydratase gene using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation leads to altered melanin production in Ascochyta lentis. J. Fungi 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundock, P.; den Dulk-Ras, A.; Beijersbergen, A.; Hooykaas, P.J. Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 3206–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundock, P.; Hooykaas, P.J. Integration of Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome by illegitimate recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 15272–15275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piers, K.L.; Heath, J.D.; Liang, X.; Stephens, K.M.; Nester, E.W. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 1613–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, M.J.; Bundock, P.; Hooykaas, P.J.; Beijersbergen, A.G. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of filamentous fungi. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouka, R.J.; Gerk, C.; Hooykaas, P.J.; Bundock, P.; Musters, W.; Verrips, C.T.; de Groot, M.J. Transformation of Aspergillus awamori by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated homologous recombination. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, M.C.; Crespo, A. Comparison of development of axenic cultures of five species of lichen-forming fungi. Mycol. Res. 2000, 104, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malonek, S.; Meinhardt, F. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated genetic transformation of the phytopathogenic ascomycete Calonectria morganii. Curr. Genet. 2001, 40, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikosch, T.S.; Lavrijssen, B.; Sonnenberg, A.S.; van Griensven, L.J. Transformation of the cultivated mushroom Agaricus bisporus (Lange) using T-DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Curr. Genet. 2001, 39, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rho, H.S.; Kang, S.; Lee, Y.H. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of the plant pathogenic fungus, Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Cells 2001, 12, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combier, J.P.; Melayah, D.; Raffier, C.; Gay, G.; Marmeisse, R. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation as a tool for insertional mutagenesis in the symbiotic ectomycorrhizal fungus Hebeloma cylindrosporum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 220, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, C.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.; Kang, S. A dual selection based, targeted gene replacement tool for Magnaporthe grisea and Fusarium oxysporum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michielse, C.B.; Arentshorst, M.; Ram, A.F.; van den Hondel, C.A. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation leads to improved gene replacement efficiency in Aspergillus awamori. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielse, C.B.; Hooykaas, P.J.; van den Hondel, C.A.; Ram, A.F. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation as a tool for functional genomics in fungi. Curr. Genet. 2005, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, E.; Romaine, C.P.; Chen, X.; Geiser, D.; Raina, R.; Kang, S. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Fusarium oxysporum: An efficient tool for insertional mutagenesis and gene transfer. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, R.J. A guide to binary vectors and strategies for targeted genome modification in fungi using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 87, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idnurm, A.; Bailey, A.M.; Cairns, T.C.; Elliott, C.E.; Foster, G.D.; Ianiri, G.; Jeon, J. A silver bullet in a golden age of functional genomics: the impact of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of fungi. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2017, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, M.H.; Kim, J.A.; Kang, S.; Choi, E.D.; Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.; Jeon, M.J.; Yu, N.H.; Park, A.R.; Kim, J.C.; et al. Optimization of Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Xylaria grammica EL000614, an endolichenic fungus producing grammicin. Mycobiology 2021, 49, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Jeong, M.H.; Wang, H.Y.; Kim, J.A.; Yu, N.H.; Kim, S.; Cheong, Y.H.; Kang, S.; Lee, Y.H.; Hur, J.S. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of the lichen fungus, Umbilicaria muehlenbergii. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Chen, L.; Ma, A. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of the king tuber medicinal mushroom Lentinus tuber-regium (Agaricomycetes). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2018, 20, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.K.; Kuhad, R.C. Genetic transformation of lignin degrading fungi facilitated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. BMC Biotechnol. 2010, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daboussi, M.; Djeballi, A.; Gerlinger, C.; Blaiseau, P.; Bouvier, I.; Cassan, M.; Lebrun, M.; Parisot, D.; Brygoo, Y. Transformation of seven species of filamentous fungi using the nitrate reductase gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Current genetics 1989, 15, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, M.J.; Bundock, P.; Hooykaas, P.J.; Beijersbergen, A.G. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of filamentous fungi. Nature biotechnology 1998, 16, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-Lugo, R.; Zimmermann, J.; Rizk, A.M.; Fernandez-Lahore, M. Development of a transformation system for Aspergillus sojae based on the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated approach. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Diaz, B. Strategies for the transformation of filamentous fungi. J. Apple. Microbiol. 2002, 92, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Ha, B.S.; Ro, H.S. Current technologies and related issues for mushroom transformation. Mycobiology 2015, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Guo, A.; Lu, Z.; Tan, S.; Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Zheng, J.; Xi, J.; et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of a hevein-like gene into asparagus leads to stem wilt resistance. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.H.; Wang, S.T. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation method for Fusarium oxysporum. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2391, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Spain, S.; Andrade, P.I.; Brockman, N.E.; Fu, J.; Wickes, B.L. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Candida glabrata. J Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Kim, W.; Paguirigan, J.A.; Jeong, M.H.; Hur, J.S. Establishment of Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Cladonia macilenta, a model lichen-forming fungus. J Fungi 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z. An effective method for Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Jatropha curcas L. using cotyledon explants. Bioengineered 2020, 11, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Park, J.; Jeon, J.; Chi, M.H.; Goh, J.; Yoo, S.Y.; Jung, K.; Kim, H.; Park, S.Y.; Rho, H.S.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of T-DNA integration into the chromosomes of Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 66, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Hou, H.; Huang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Tu, H.; Wang, L. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Coniella granati. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 182, 106149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, M.R.A.; Massa, G.A.; Colabelli, M.N.; Ridao, A.D.C. Efficient Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation system of Diaporthe caulivora. J Microbiol Methods 2021, 184, 106197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khang, C.H.; Berruyer, R.; Giraldo, M.C.; Kankanala, P.; Park, S.Y.; Czymmek, K.; Kang, S.; Valent, B. Translocation of Magnaporthe oryzae effectors into rice cells and their subsequent cell-to-cell movement. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 1388–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Chi, M.H.; Khang, C.H.; Park, S.Y.; Kang, S.; Valent, B.; Lee, Y.H. The ER chaperone LHS1 is involved in asexual development and rice infection by the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).