1. Introduction

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) is a progressive disease that causes central blindness [

1]. The current first-line treatment for nAMD is the injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [

1,

2,

3]. To date, the ranibizumab [

2], aflibercept [

1], and brolucizmab [

4,

5] formulation has been used to stabilize nAMD. Among them, aflibercept has been extensively used and is still the most widely used drug worldwide. Aflibercept is a recombinant fusion protein that fuses consistent portions of the VEGF receptor 1 and 2 extracellular domains to the Fc portion of the human immunoglobulin G, which blocks placental growth factor as well [

6]. In 2022, faricimab was approved after the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials [

7], which were humanized, used bispecific IgG monoclonal antibody, and demonstrated inhibition of VEGF-A and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) [

8]. Ang-2 expression increases in the vascular endothelium and is associated with inflammation or pericyte vessel loss [

6]. These phase-3 trials demonstrated that intravitreal faricimab (IVF) injection was non-inferior to intravitreal aflibercept (IVA) in the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and the stabilization of neovascularization activity in patients with nAMD [

7]. Recently, several studies described the effectiveness of faricimab for treating naïve nAMD in real-world practice, whose effects were similar to those reported in the phase-3 clinical trials [

9,

10]. However, knowledge about choosing between existing drugs and this new drug for their use in treating naïve cases is lacking. Therefore, this study compared the safety and effectiveness between aflibercept and faricimab treatments for patients with nAMD in real-word conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

The Ethics Committee of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number 10039) approved this study and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. The need for informed consent was waived since this study was retrospective in nature.

The study included a consecutive series of patients with treatment-naïve nAMD, who visited Osaka University Hospital and initiated the treatment with intravitreal aflibercept or faricimab injection. We excluded patients with myopia of > − 6 dioptres and a history of vitrectomy. The patients who visited first between June 2022 and September 2022 and between October 2022 and March 2023 were treated with IVA and IVF, respectively. Three monthly intravitreal injections were provided for all patients.

At each follow-up visit, all patients underwent comprehensive ocular examination, including BCVA measurement using Landolt C charts, color fundus photography, and spectral-domain and swept-source optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT; Cirrus HD-OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc, Dublin, CA, and SS-OCT; DRI-SS-OCT, Topcon Inc, Tokyo, Japan).

Intraretinal edema, subretinal fluid, and pigment epithelial detachment were evaluated using both OCT methods. The distance between the internal limiting membrane and the presumed retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) at the fovea was the central retinal thickness (CRT) and was assessed using SD-OCT. The distance between the presumed RPE and chorioscleral interface at the fovea was the central choroidal thickness (CCT) and was evaluated using SS-OCT. AMD was diagnosed using fluorescein angiography and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), and its subtype was determined using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (HRA2; Heidelberg Engineering Inc, Dossenheim, Germany).

The outcomes included BCVA, the resolution rate of exudative change (subretinal fluid, intraretinal fluid, and pigment epithelium detachment), CRT, and CCT at 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

The decimal visual acuity was converted to a logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) units for statistical analyses. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for non-numeric data and the Wilcoxon test for numeric data were used to compare the clinical characteristics between the IVA- and IVF-treated patients and those who did not. The BCVA, CRT, and CCT changes in each group were assessed using one-way analysis of variance. The rates of eyes with residual exudative changes were compared between the IVA and IVF groups using the chi-square test. The unpaired t-test was used to compare the changes in the three parameters at each time point between the two groups. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro version 17 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

Thirty eyes of 28 IVA-treated patients (IVA group) and 30 eyes of 29 IVF-treated patients (IVF group) were included. No cases existed in which the treatment was initiated but interrupted or switched during the 3 months.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the IVA and IVF groups. The two groups showed no significant differences in age, sex, lesion size, or nAMD subtype.

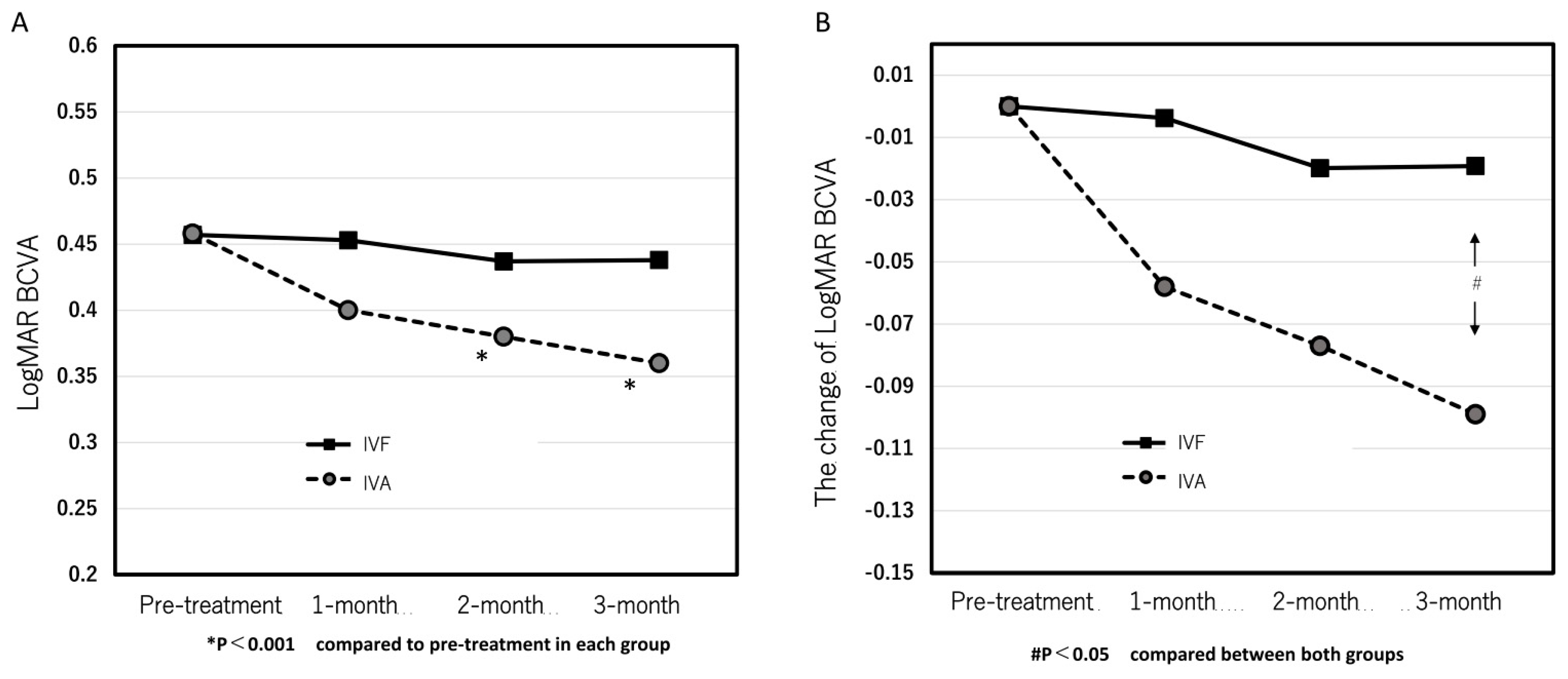

The mean logMAR BCVA at pre-treatment and 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment in the IVA group were 0.46 ± 0.46, 0.40 ± 0.42, 0.38 ± 0.40, and 0.36 ± 0.37, respectively. (

Figure 1A) The significant improvements were seen at 2 and 3 months (p = 0.095, 0.0088, and 0.0031 at 1, 2, and 3 months, respectively). Contrastingly, the mean logMAR BCVA at pre-treatment and 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment were 0.46 ± 0.41, 0.45 ± 0.41, 0.44 ± 0.46, and 0.44 ± 0.45, respectively, in the IVF group and exhibited no significant improvement at all points after the first treatment compared with the pre-treatment (p = 0.89, 0.59, and 0.60 at 1, 2, and 3 months, respectively) (

Figure 1A).

Figure 1B shows the time course of the mean changes of logMAR BCVA from pre-treatment. A significant difference at 3 months was observed between both groups. (p = 0.049)

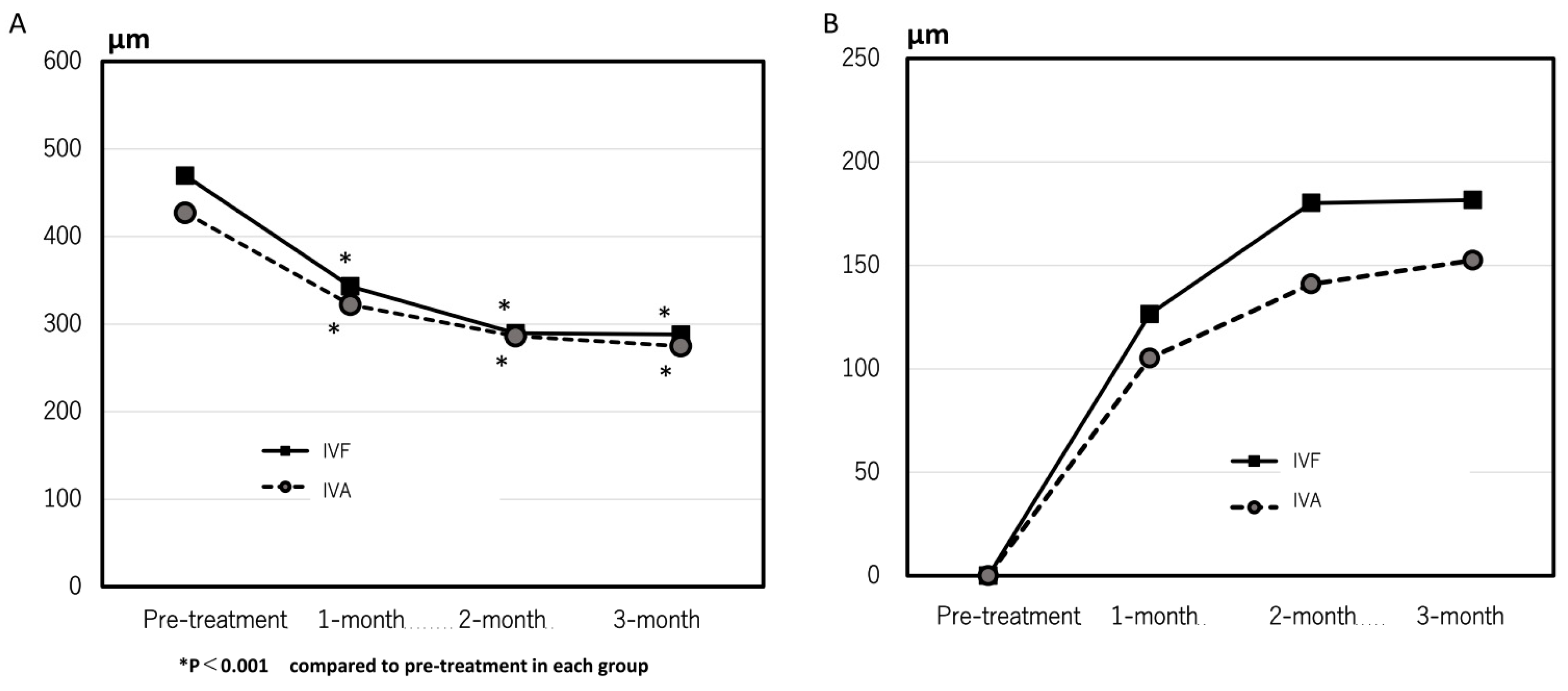

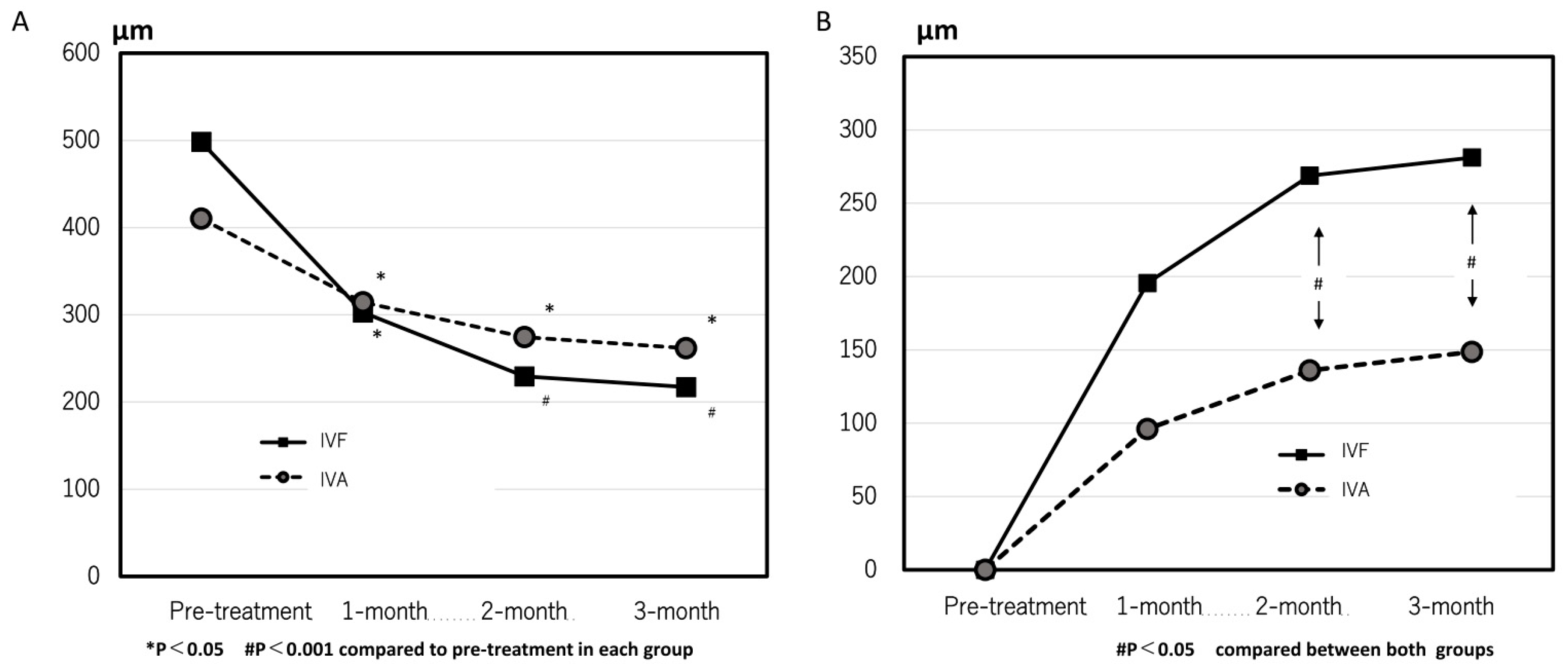

The mean CCT significantly decreased from 205 ± 79 µm and 232 ± 88 µm at pre-treatment to 191 ± 92 µm and 208 ± 100 µm at 3 months in the IVA and IVF groups, respectively. The mean CRT at 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment markedly improved compared with pre-treatment in both groups. (

Figure 2A) No significant difference was observed in the changes in the CRT at all points. (

Figure 2B)

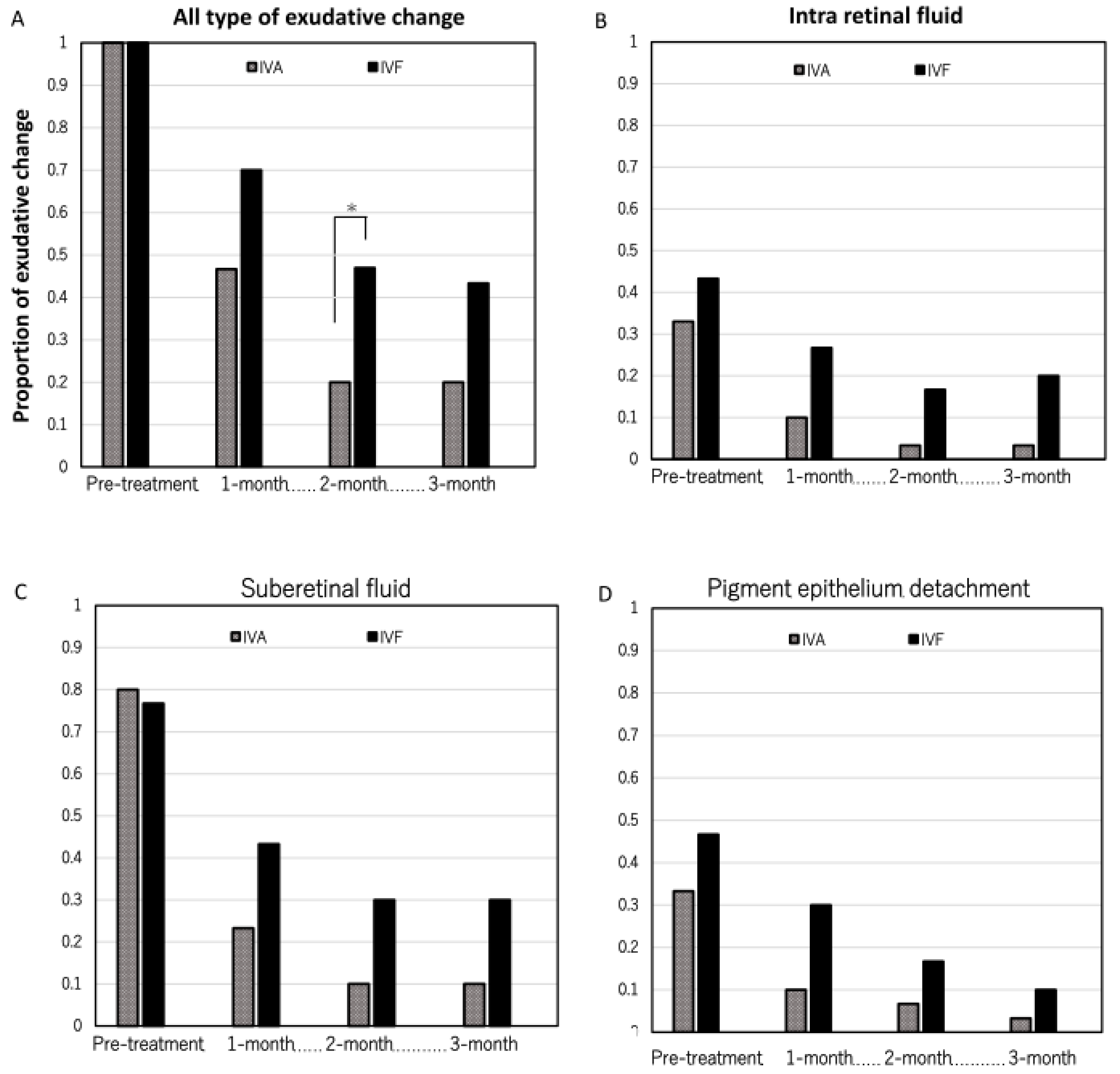

Figure 3A indicates the rate of eyes with residual all types of exudative change in each group. In the IVA group, the rates were 0.47 (14/30), 0.20 (6/30), and 0.20 (6/30) at 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment, respectively. Contrastingly, the rates were 0.70 (21/30), 0.47 (14/30), and 0.43 (13/30) at 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment, respectively, in the IVF group. Significant differences were observed at 2 months between the two groups (p = 0.065, 0.026, and 0.050, respectively).

Figure 3B, C, and D show the rate of eyes with the presence of intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid, and pigment epithelium detachment. No considerable difference was seen in the rate of eyes with each type of exudative change.

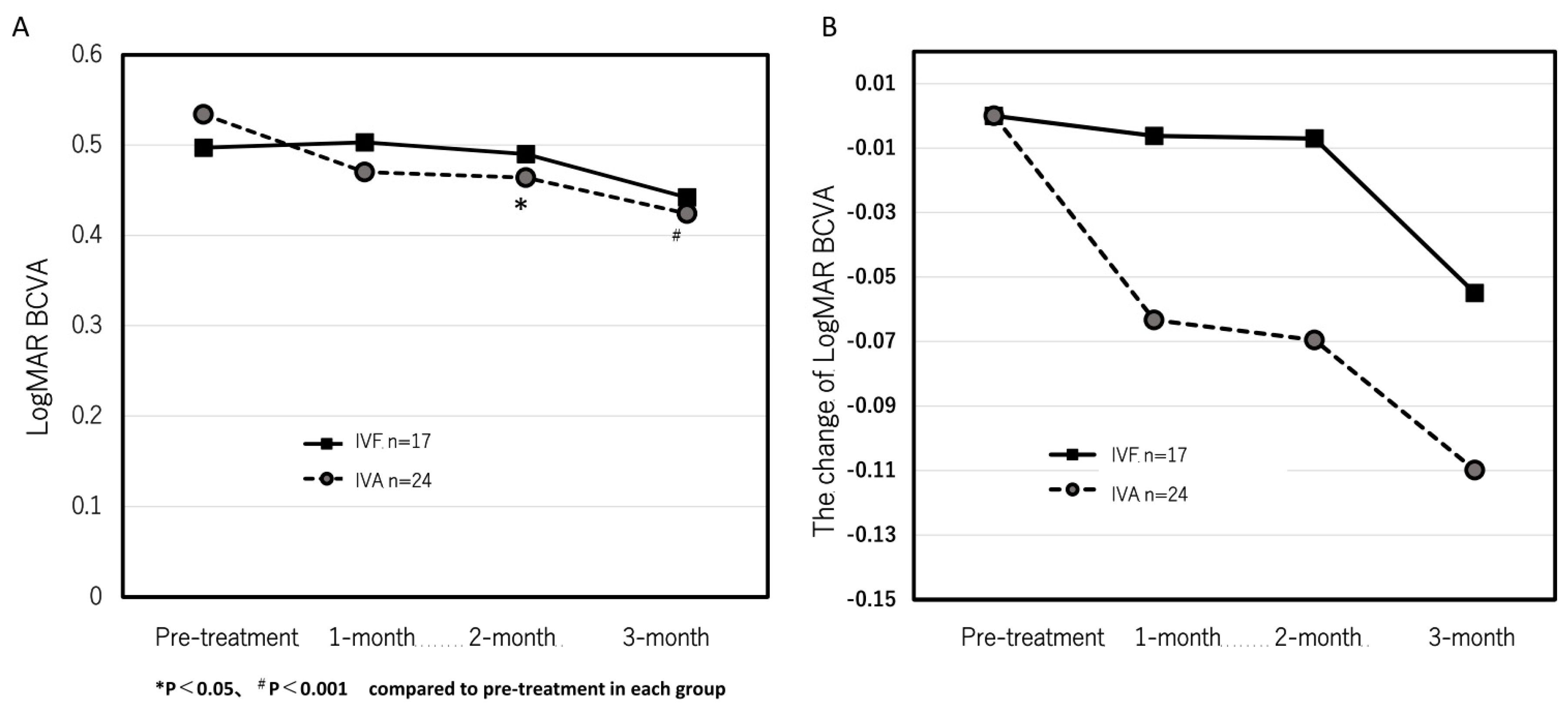

Next, we investigated the patients who obtained complete resolution of the exudative changes after loading dose in both groups to evaluate whether the residual exudative changes were the cause of the lack of visual improvement in the IVF group. In 24 eyes in the IVA group and 17 eyes in the IVF group, complete resolution of the exudative changes after the loading dose was observed. In the IVA group, the logMAR BCVA significantly improved from 0.53 ± 0.48 at pre-treatment to 0.47 ± 0.44, 0.46 ± 0.41, and 0.42 ± 0.41 at 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment, respectively. (

Figure 4A) Significant improvements were observed at the 2- and 3-month points (p = 0.13, 0.035, and 0.0047 at 1, 2, and 3 months, respectively). However, the logMAR BCVA were 0.50 ± 0.50, 0.50 ± 0.49, 0.49 ± 0.55, and 0.44 ± 0.53 at pre-treatment, 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment, respectively, in the IVF group (

Figure 4A). No significant improvement was observed (p = 0.84, 0.88, and 0.20 at 1, 2, and 3 months, respectively).

Figure 4B indicates the time course of the mean changes of logMAR BCVA from pre-treatment. No significant difference was observed between both groups.

In the IVF group, the CRT significantly decreased from 498 ± 227 µm at pre-treatment to 302 ± 146 µm, 229 ± 188 µm, and 217 ± 74 µm at 1, 2, and 3 months after the first treatment, respectively (p = 0.001, <0.0001, and <0.0001, respectively, compared with pre-treatment). In the IVA group, the CRT was 410 ± 257 µm, 314 ± 227 µm, 274 ± 171 µm, and 262 ± 152 µm at pre-treatment, 1, 2, and 3 months, respectively (p = 0.002, <0.0001, and <0.0001 at 1, 2 and 3 months, respectively, compared with the pre-treatment) (

Figure 5A). Changes in CRT were significantly greater in the IVF group than that in the IVA group at 2 and 3 months (p = 0.020 and 0.028, respectively) (

Figure 5B). The rate of eyes with residual exudative changes were 0.38 (9/24) and 0.09 (2/29) in the IVA group and 0.44(7/16) and 0.13(2/16) in the IVF group at 1 and 2 months after the first treatment, respectively. No considerable difference was observed between both groups.

RPE tear occurred in one eye with type-1 MNV in the IVA group. One patient in the IVF group complained of vertigo after treatment initiation. No other ocular or systematic adverse events occurred during the study period.

4. Discussion

Herein, we compared the effects between IVA and IVF for eyes with treatment-naïve nAMD. The rate of eyes that achieved complete resolution of exudative change in the IVF group was significantly lower than that in the IVA group. Furthermore, a significant improvement in the mean BCVA was observed in the IVA group and not in the IVF group. Additionally, when analyzing the eyes that exhibited complete resolution of exudative change, the mean logMAR BCVA did not improve in the IVF group; however, the change in CRT was significantly larger than that in the IVA group.

Several previous studies have reported the effects of three monthly loading doses of IVA for eyes with AMD. The View study, a large clinical trial, reported an improvement of +6-8 letters after the 3-monthly loading dose [

3]. Additionally, other studies have reported an average improvement of +5 letters or 0.1 logMAR [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The results of the present study are comparable to that of previous reports. Recently, few studies have reported the effect of loading doses of faricimab in clinical settings [

9,

11]. Matsumoto et al reported that the logMAR BCVA significantly improved from 0.33 to 0.22 after the loading dose [

9], and Mukai et al reported that the logMAR BCVA significantly improved from 0.40 to 0.32 [

11]. However, the BCVA in this study exhibited no significant improvement in the IVF group. One possible reason for the difference in the change of BCVA improvement in both groups was that the rates of eyes with residual exudative change after the loading dose in the IVF group were higher than that in the IVA group [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Contrastingly, no significant improvement in BCVA was observed even in the eyes that only achieved complete resolution in exudative change. This suggests that other factors besides a higher rate of eyes with residual exudative changes may have been associated with the lack of visual improvement in the IVF group. In the sub-analysis of the TENEYA and LUCERNE trials, the rate of eyes with complete resolution of exudative change in the IVF group was higher than or similar to that in the IVA group [

7,

19]. These differences from the current results were due to some possible reasons. First, the analysis was examined for 8 weeks after 4 consecutive faricimab doses and 3 consecutive aflibercept doses. Second, the only types of exudative changes evaluated were intraretinal and subretinal fluid. Third, racial differences existed (Asians made up < 10% of the total population).

Interestingly, the mean CRT reduction at 3 months with IVF was greater than that with IVA when only eyes that achieved complete resolution of exudative change were considered in this study. In the TENEYA and LUCERNE trials, faricimab tended to reduce CRT more than aflibercept. Furthermore, faricimab possibly has a stronger ability to reduce CRT in effective cases than aflibercept [

7,

19,

20].

The main limitations of this study were its retrospective and single-center nature and short-term outcomes. Furthermore, the number of patients was small, and all patients were Japanese. However, this study had no cases in which treatment was changed midway due to inadequate efficacy, and all patients were examined. Although further prospective studies with larger sample sizes should involve long-term outcomes, we believe that this study is meaningful as a real-world short-term treatment outcome.

5. Conclusions

IVA and IVF treatments are safe and effective in reducing exudation and retinal thickness. However, IVA was more likely to eliminate exudative changes and improve visual acuity in the short term than IVF.

Author Contributions

C.H. analyzed and interpreted the patient data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. M.S, S.F, Y.F, K.S, K.M and S.S acquired patient data. K.N reviewed manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number 10039).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. 2012;379:1728-1738. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. The New Eng J Med. 2006;355(14):1419-1431. [CrossRef]

- Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2537-2548. [CrossRef]

- Dugel PU, Koh A, Ogura Y, et al. HAWK and HARRIER: Phase 3, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Masked Trials of Brolucizumab for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:72-84. [CrossRef]

- Dugel PU, Singh RP, Koh A, et al. HAWK and HARRIER: Ninety-Six-Week Outcomes from the Phase 3 Trials of Brolucizumab for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:89-99. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos N, Martin J, Ruan Q, et al. Binding and neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and related ligands by VEGF Trap, ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Angiogenesis. 2012;15:171-185. [CrossRef]

- Heier JS, Khanani AM, Quezada Ruiz C, et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab up to every 16 weeks for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (TENAYA and LUCERNE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. F 2022;399:729-740. [CrossRef]

- Regula JT, Lundh von Leithner P, Foxton R, et al. Targeting key angiogenic pathways with a bispecific CrossMAb optimized for neovascular eye diseases. EMBO. 2016;8:1265-1288. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto H, Hoshino J, Nakamura K, Nagashima T, Akiyama H. Short-term outcomes of intravitreal faricimab for treatment-naive neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;261:2945-2952. [CrossRef]

- Mukai R, Kataoka K, Tanaka K, et al. Three-month outcomes of faricimab loading therapy for wet age-related macular degeneration in Japan. Sci Rep. 2023;13:8747. [CrossRef]

- Koizumi H, Kano M, Yamamoto A, et al. Subfoveal Choroidal Thickness during Aflibercept Therapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Twelve-Month Results. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:617-624. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto H, Morimoto M, Mimura K, Ito A, Akiyama H. Treat-and-Extend Regimen with Aflibercept for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Efficacy and Macular Atrophy Development. Ophthalmology Retina.2018;2:462-468. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Lee DW, Chang YS, Kim JW, Kim CG. Twelve-month outcomes of treatment using ranibizumab or aflibercept for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a comparative study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:2101-2109. [CrossRef]

- Gillies MC, Nguyen V, Daien V, Arnold JJ, Morlet N, Barthelmes D. Twelve-Month Outcomes of Ranibizumab vs. Aflibercept for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Data from an Observational Study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2545-2553. [CrossRef]

- Jaffe GJ, Kaiser PK, Thompson D, et al. Differential Response to Anti-VEGF Regimens in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Patients with Early Persistent Retinal Fluid. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1856-1864. [CrossRef]

- Guymer RH, Markey CM, McAllister IL, Gillies MC, Hunyor AP, Arnold JJ. Tolerating Subretinal Fluid in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treated with Ranibizumab Using a Treat-and-Extend Regimen: FLUID Study 24-Month Results. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:723-734. [CrossRef]

- Jaffe GJ, Martin DF, Toth CA, et al. Macular morphology and visual acuity in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1860-1870. [CrossRef]

- Waldstein SM, Simader C, Staurenghi G, et al. Morphology and Visual Acuity in Aflibercept and Ranibizumab Therapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the VIEW Trials. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1521-1529. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Cheung CMG, Iida T, et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of faricimab in patients from Asian countries with neovascular age-related macular degeneration: 1-Year subgroup analysis of the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials. Graefe Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023;9:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mori R, Honda S, Gomi F, et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of faricimab up to every 16 weeks in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration: 1-year results from the Japan subgroup of the phase 3 TENAYA trial. Jap J Ophthalmol. 2023;67:301-310. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).