Submitted:

08 November 2023

Posted:

09 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The toxicity analysis

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Experimental design

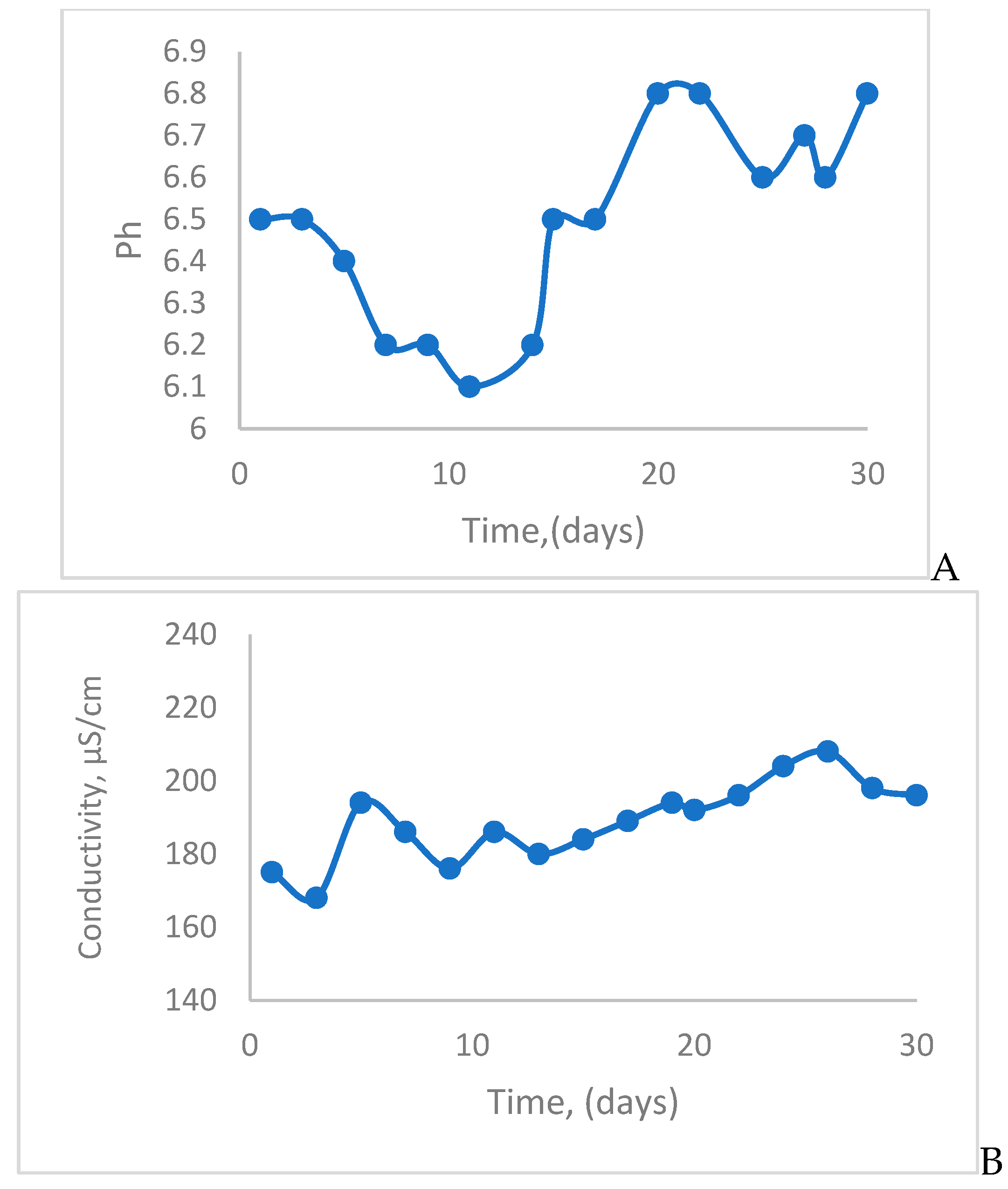

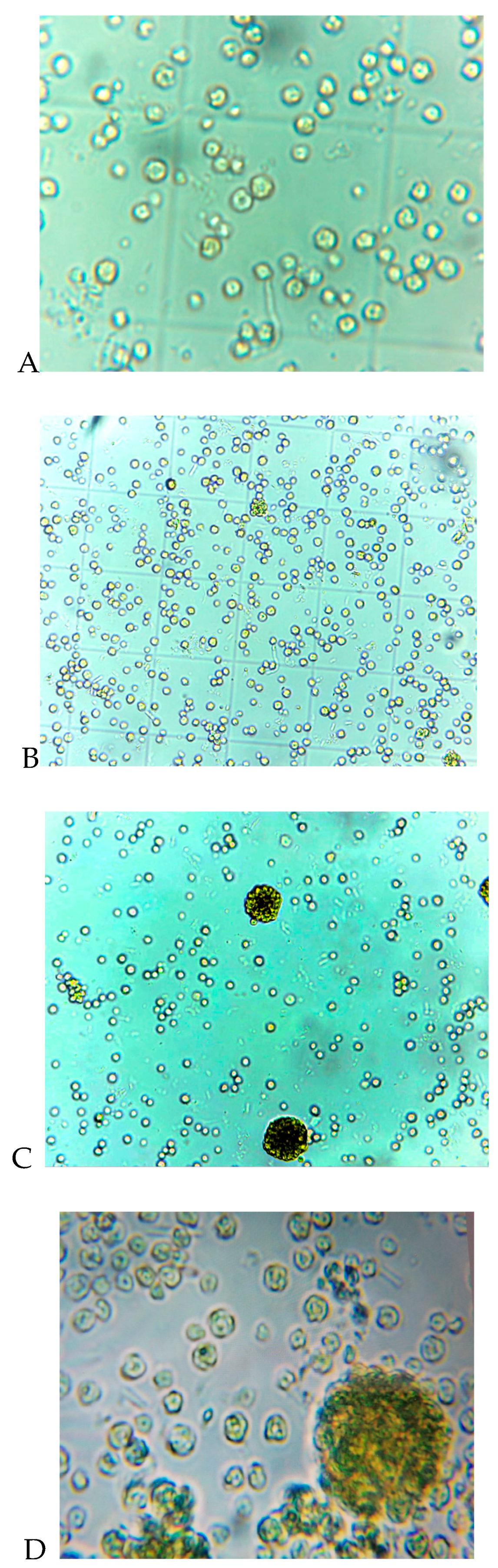

3.2. Biological medium and algae cells

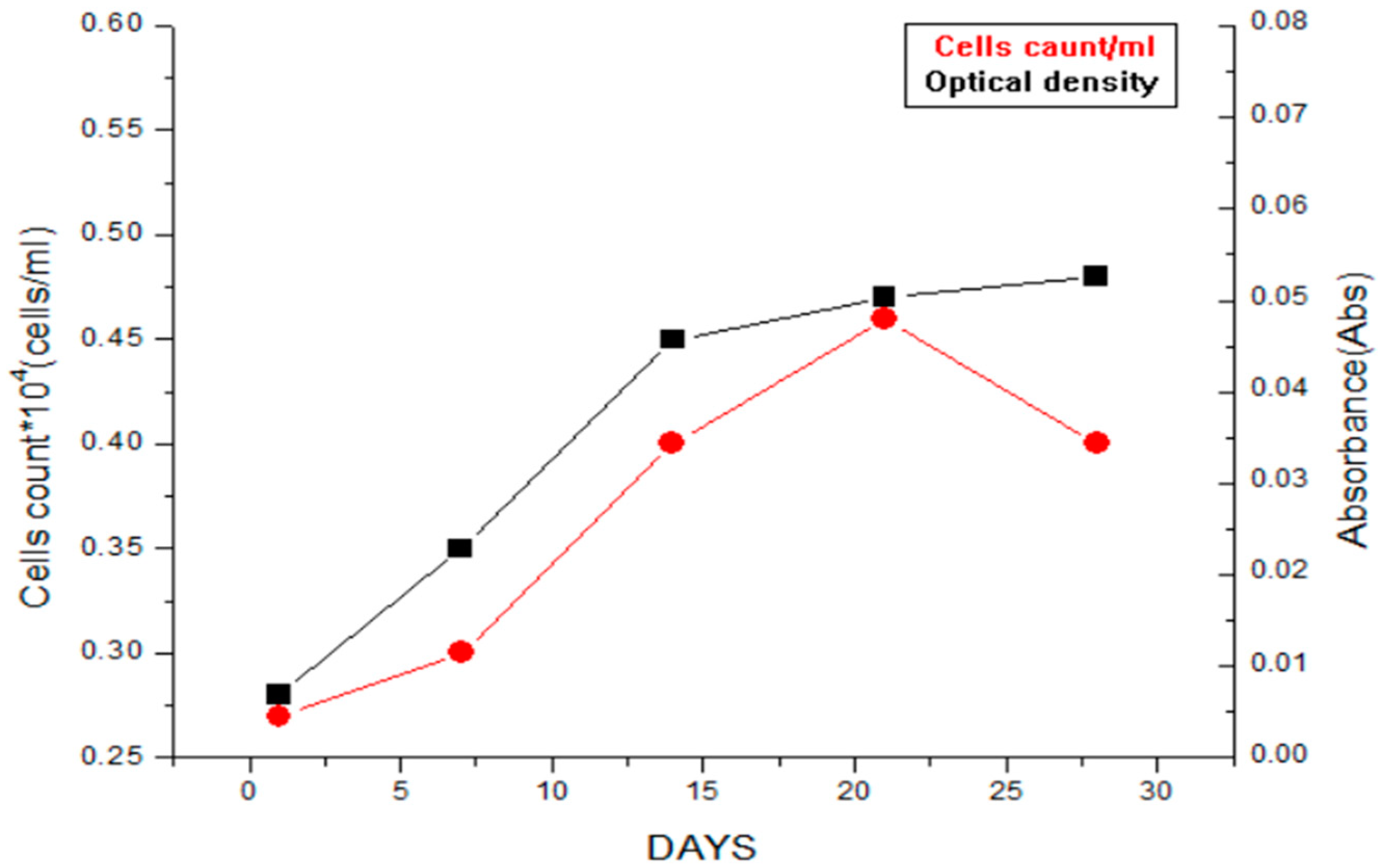

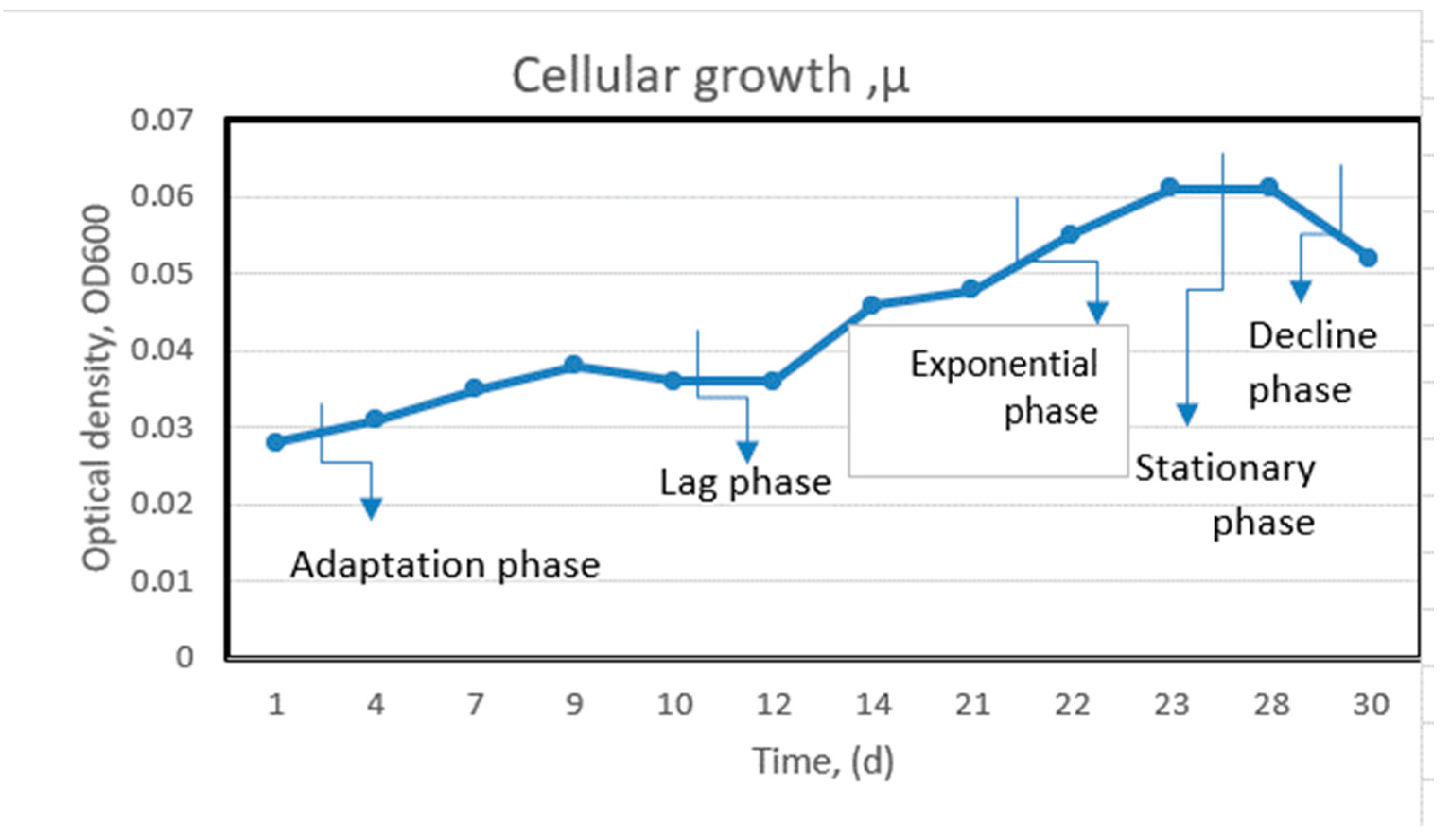

3.2.1. Measurement of cell viability, the average specific growth rate (µ) was calculated as an expression referring to the logarithmic increase in biomass during the exposure period and calculated by Equation (1):

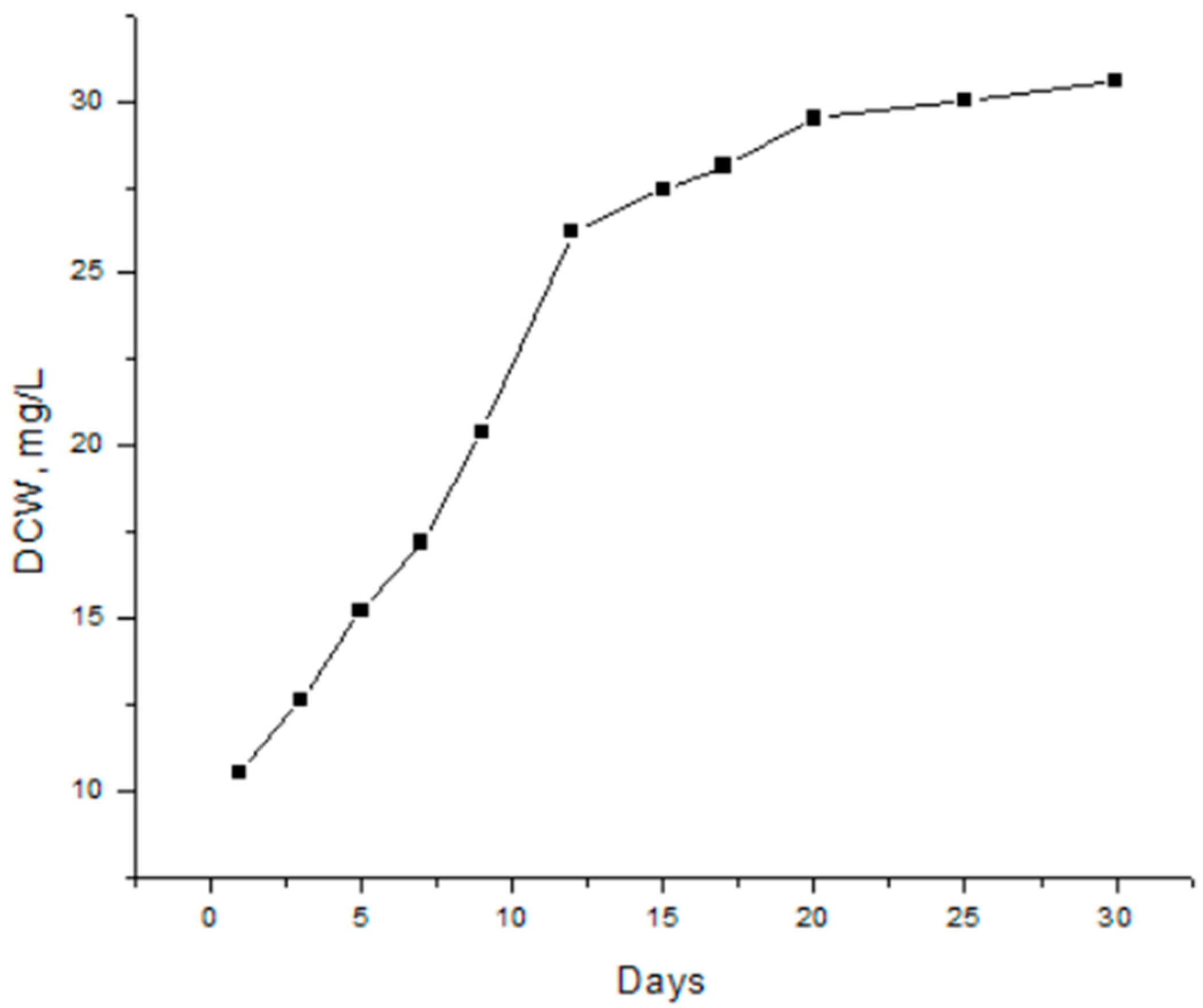

3.2.2. Dry cell weigh DCW, (mg/L) represent the optical density of microalgal culture at 600 nm and was calculated from Equation (2)

3.2.3. Biomass productivity, was calculated from Equation (3) considering the dry cell weight

3.2.4. The flocculation activity (FA) was calculated from Equation (4).

3.3. Preparation of CBM concentrations

3.4. Preparation of the bioreactors with biological samples contaminated with CBM

3.4.1. Preparation of containers for testing the dissolved oxygen

3.5. Determination of oxygen production of algal culture in chemical stress generated by CBM

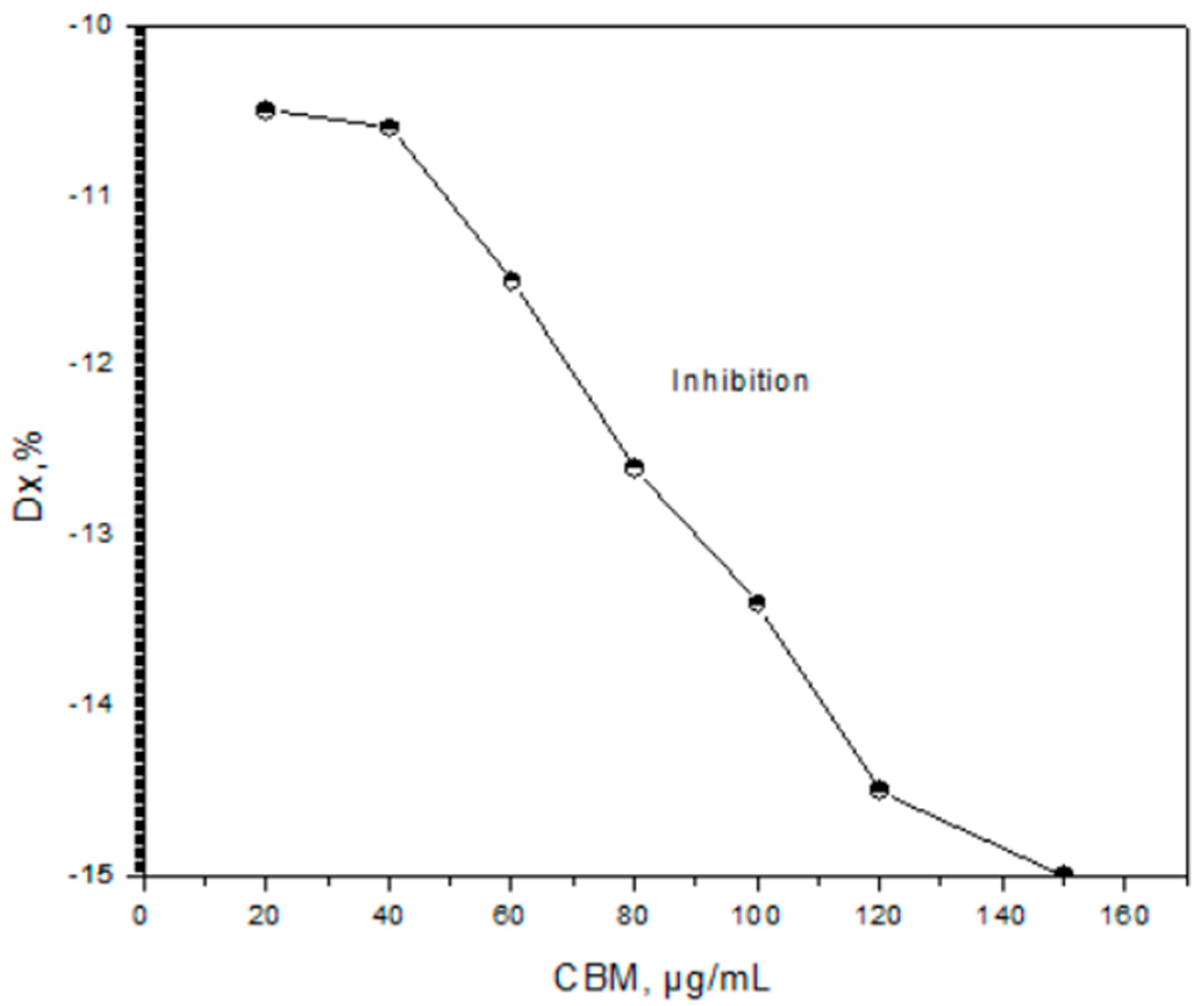

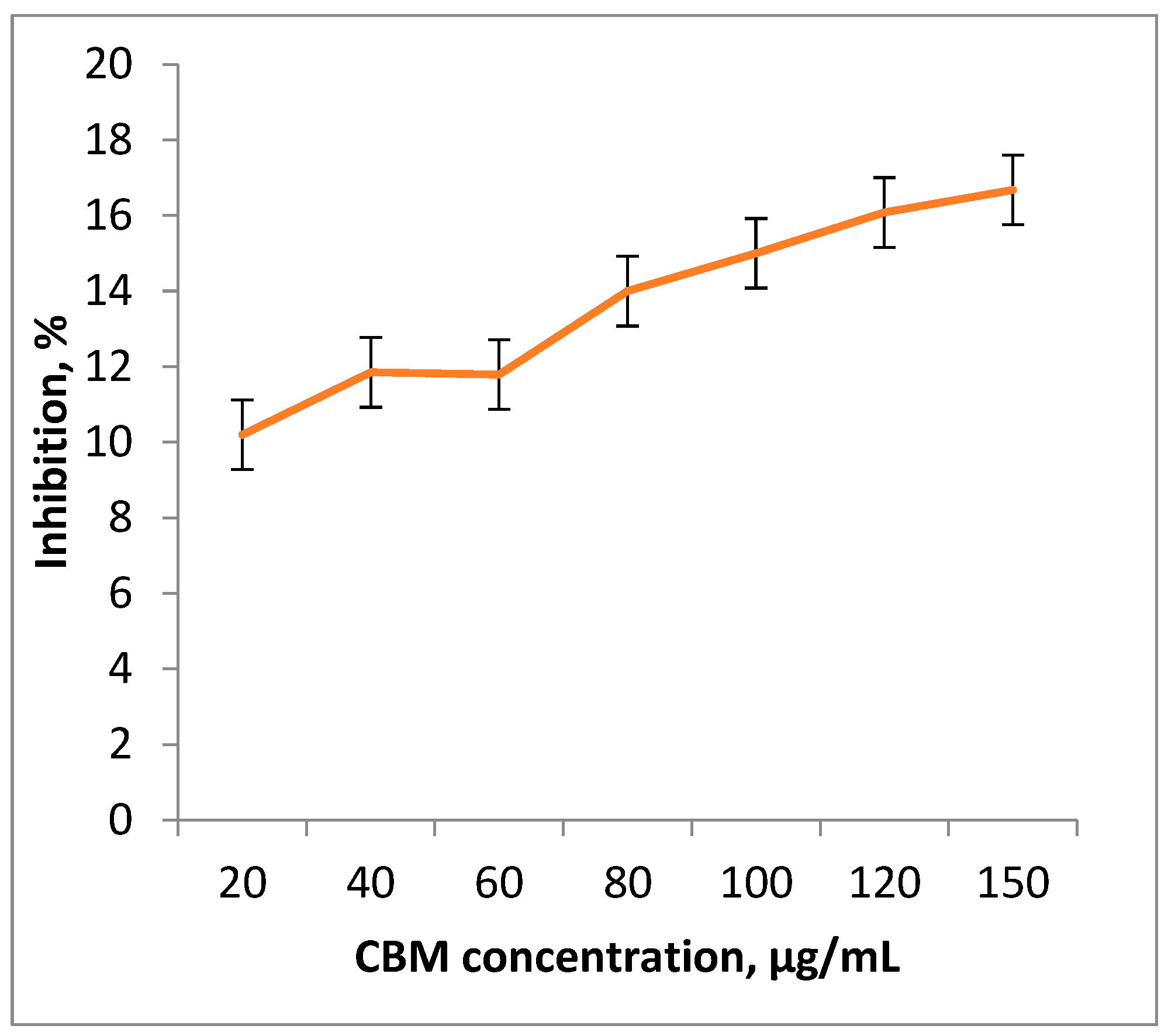

3.5.1. The percentage of cell growth inhibition

3.5.2. The percent inhibition in yield (%I) be calculated uith Equation: (7)

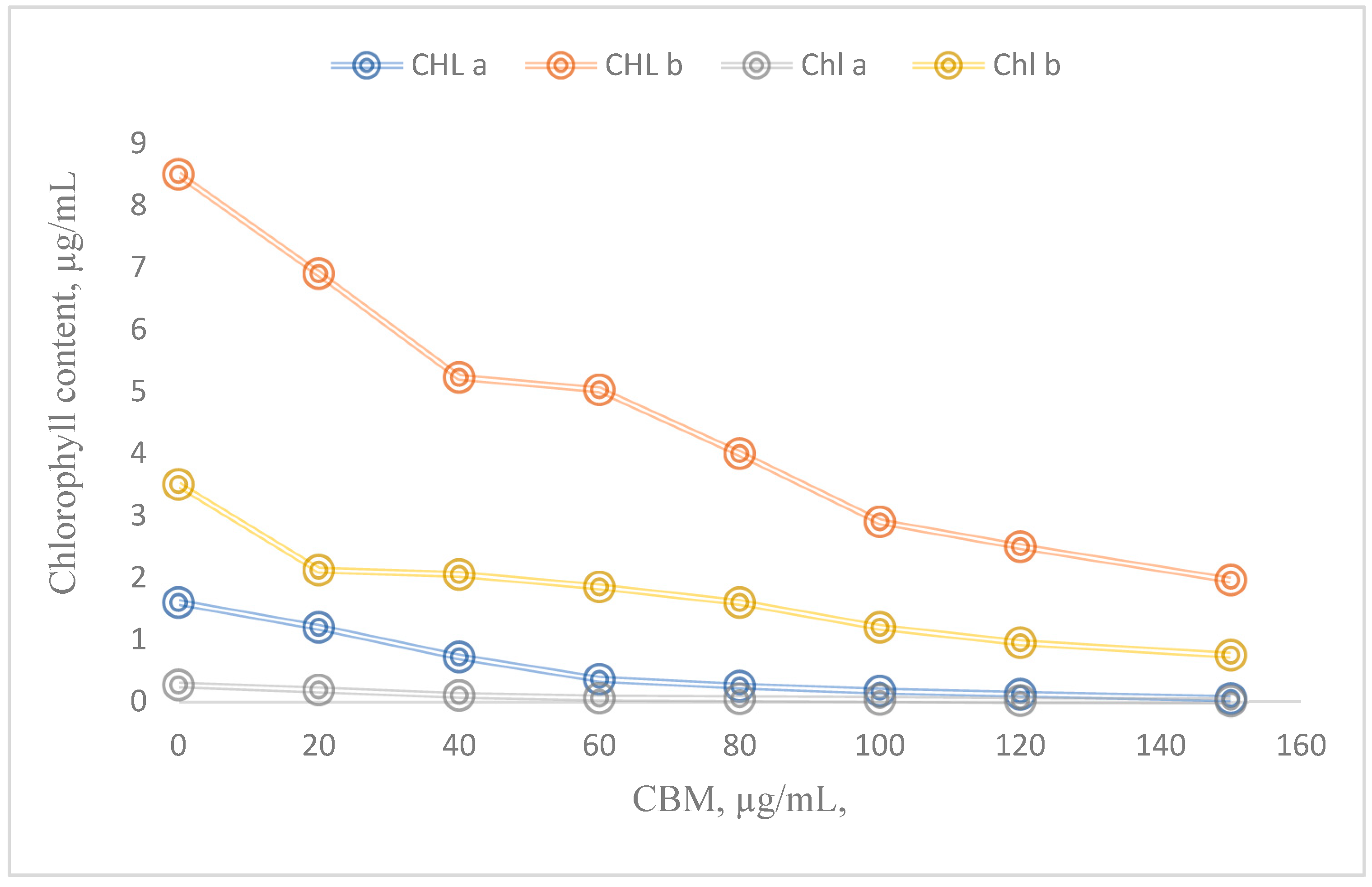

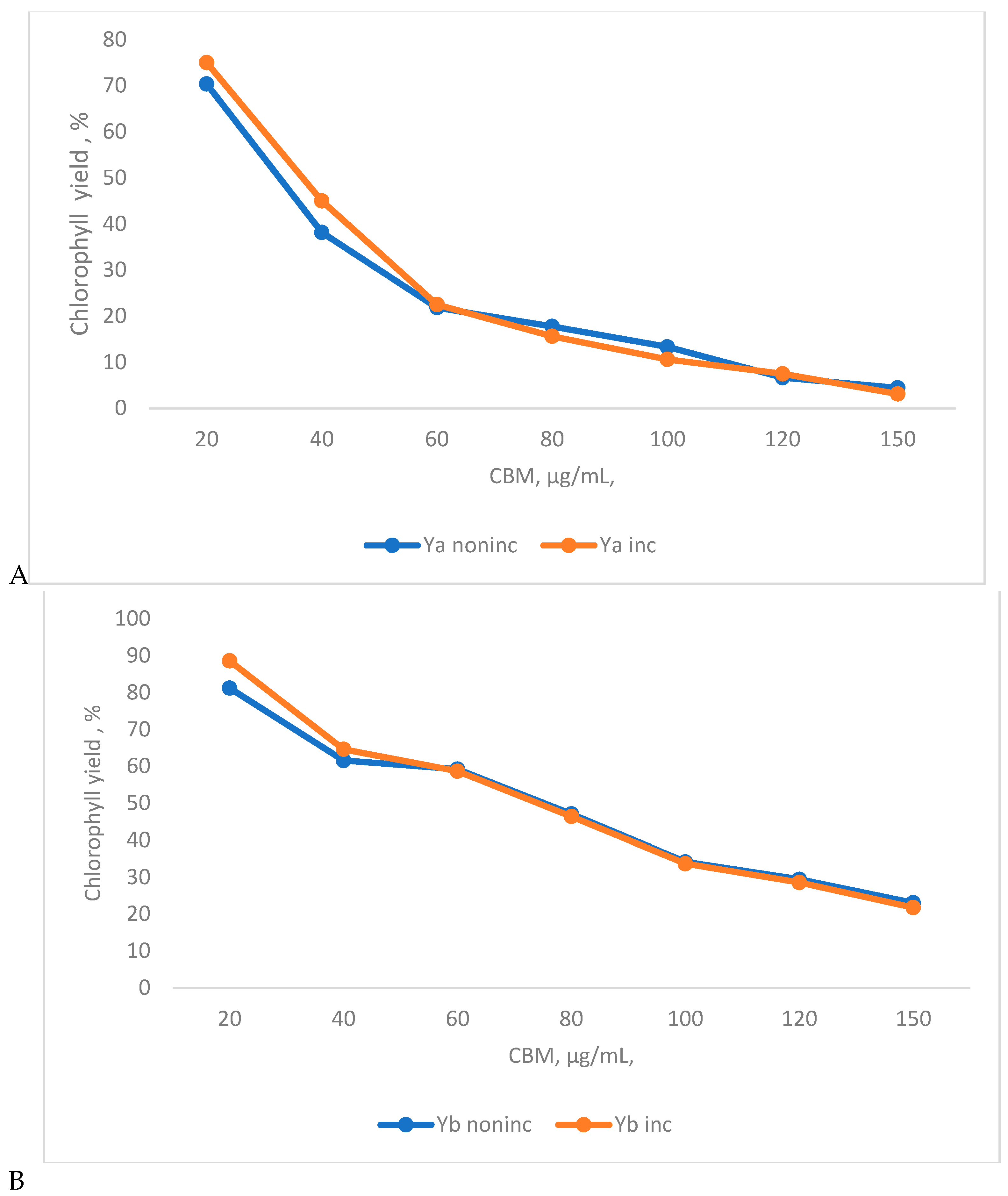

3.6. Contents of photosynthetic pigments

3.6.1. Preparation of bioreactors for chlorophyll “a” and chlorophyll “b” analysis

3.6.2. Chlorophyll fluorescence

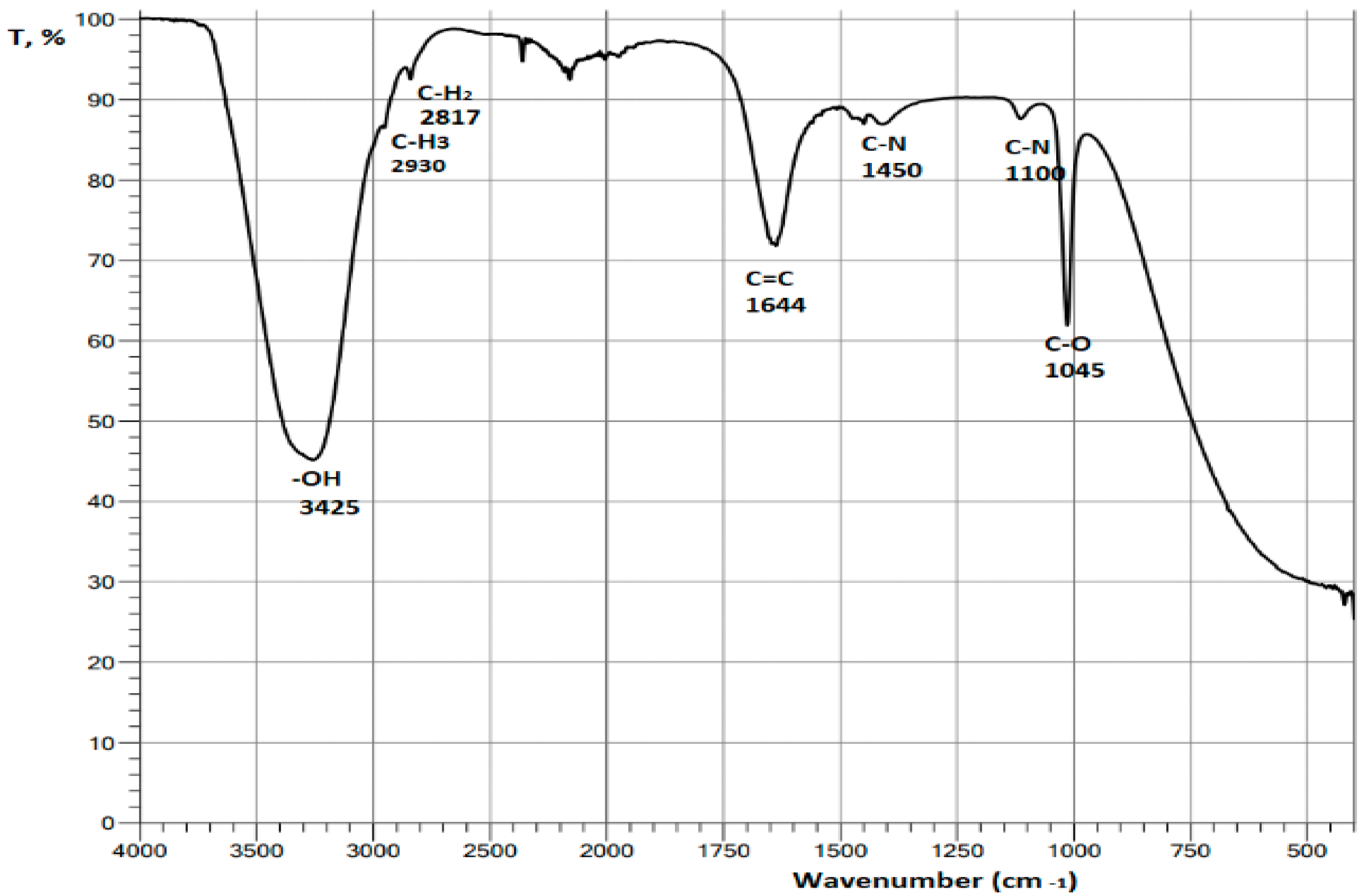

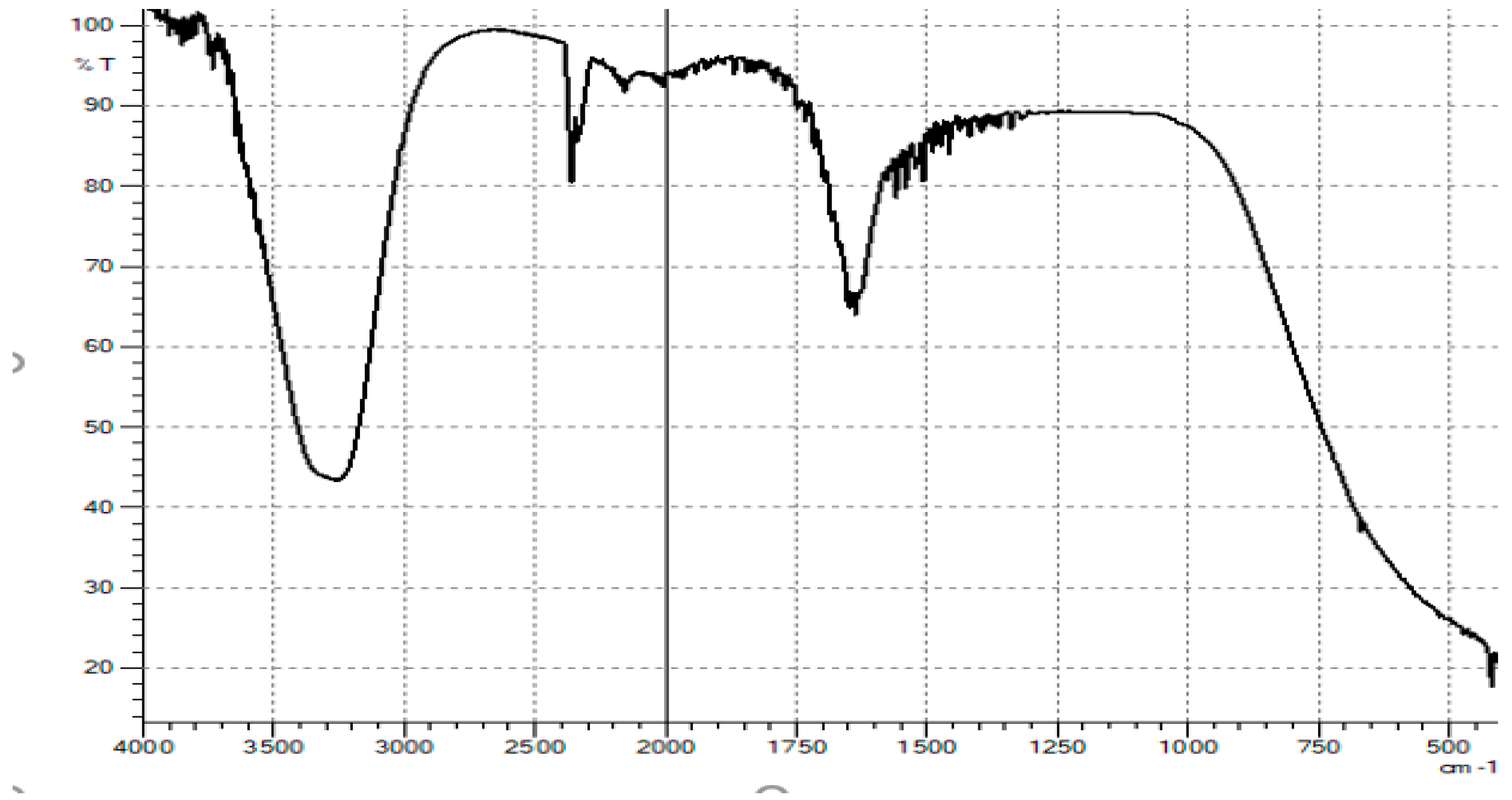

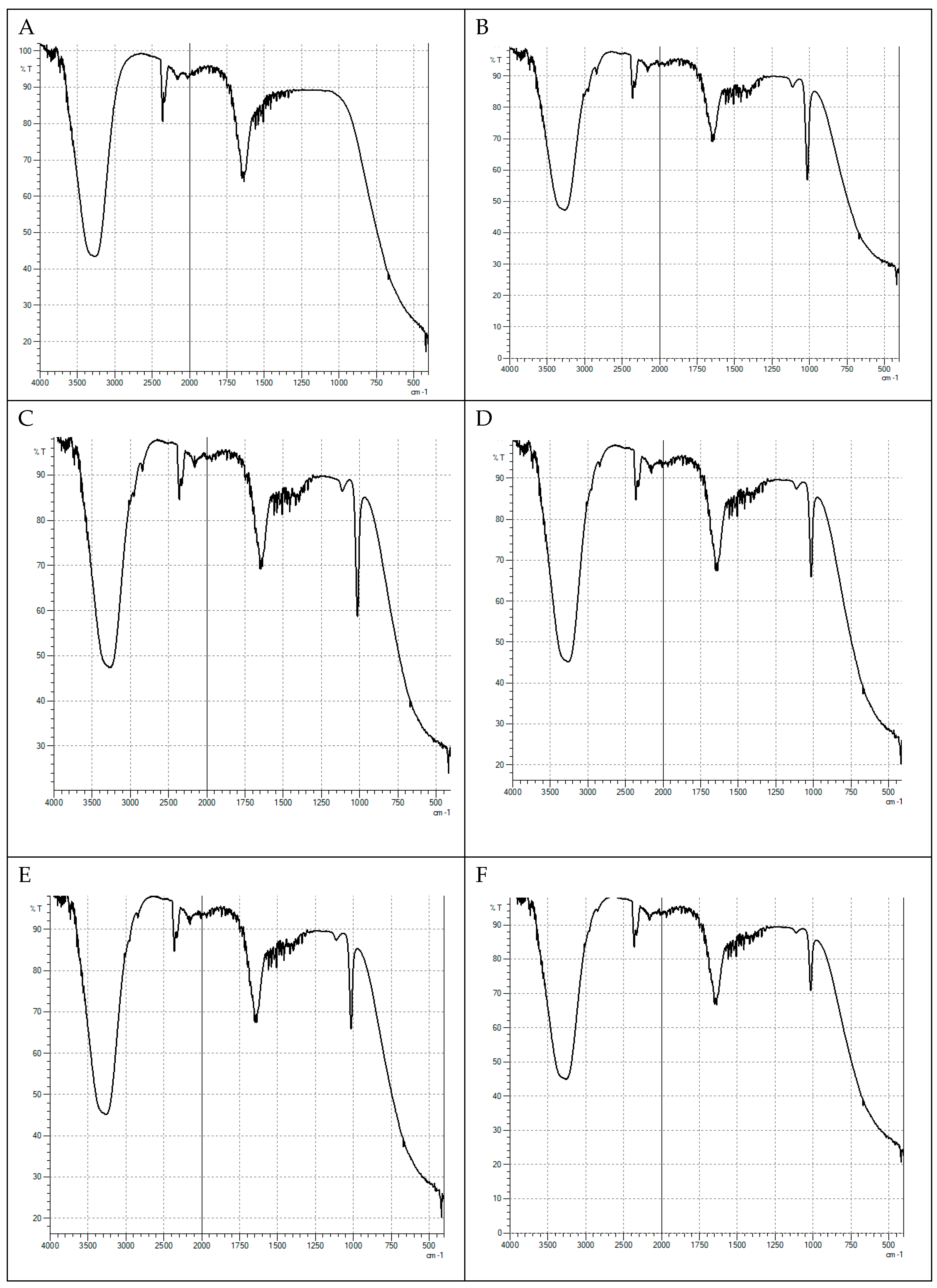

3.6.3. FTIR and fluorescence analysis of the chlorophyll extract

4. Results and Discution

5. Conclusions

References

- D. Kaszeta Restrict use of riot-control chemicals, Nature, 2019, Vol. 573, No 27,.

- A.M.B. Zekri et all Acute mass burns caused by o-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile (CS) tear gas Burns, Volume 21, Issue 8, 1995, Pages 586-589 . [CrossRef]

- P. J. Anderson et all., Acute effects of the potent lacrimator o-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile (CS) tear gas Human end experimental toxicology,1996, doi: 10.1177/096032719601500601. [CrossRef]

- 4. Anderson CO Tsang, et all., Health risks of exposure to CS gas (tear gas): an update for healthcare practitioners in Hong Kong, Hong Kong Med J , Volume 26 No. 2 , 2020. [CrossRef]

- J R. Riches et all. ,The development of an analytical method for urinary metabolites of the riot control agent 2-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile (CS), Journal of Chromatography B, No. 928, 2013, Pages 125-130. [CrossRef]

- 6. Y. Dimitroglou et all., Exposure to the Riot Control Agent CS and Potential Health Effects: A Systematic Review of the Evidence, J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1397-1411. [CrossRef]

- Kluchinsky TA, et all. Liberation of hydrogen cyanide and hydrogen chloride during high-temperature dispersion of CS riot control agent. AIHA J (Fairfax, V) 2002; 63: 493–496. [CrossRef]

- Peter G. Blain , Tear Gases and Irritant Incapacitants 1-Chloroacetophenone, 2-Chlorobenzylidene Malononitrile and Dibenz [B,F].-1,4-Oxazepine Toxicological Reviews volume 22, pages103–110 (2003). [CrossRef]

- E. J. Olajos, H.Salem Riot control agents: pharmacology, toxicology, biochemistry and chemistry Journal of applied toxicology Volume21, Issue5, 2001, Pages 355-391.

- K. Blaho-Owens Chemical crowd control agents Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 2005, Pages 319-325. [CrossRef]

- Possible lethal effects of CS tear gas on Possible lethal effects of CS tear gas on Branch Davidians during the Branch Davidians during the FBI raid on the Mount Carmel compound FBI raid on the Mount Carmel compound near Waco, Texas near Waco, Texas April 19, 1993.

- Directive 2008/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 2008 amending Directive 2000/60/EC establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy, as regards the implementing powers conferred on the Commission.

- Rice, D. Jones, and D. Stanton, A literature review of the solvents suitable for the police CS spray device, Chemical & Biological Defence Establishment, Salisbury, 1997.

- Y. Agrawal, Daniel Thornton, Alan Phipps, CS gas—Completely safe? A burn case report and literature review, Burns, Volume 35, Issue 6, 2009, Pages 895-897. [CrossRef]

- Evaluation Report Enzymatic Decontamination of Chemical Warfare Agents UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, NORTH CAROLINA 2771 EPA 600/R-12/033 | 2013.

- M. Salem, et all., Riot Control Agents, Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Third Edition) 2014, Pages 137-154. [CrossRef]

- R. Borusiewicz Chromatographic analysis of the traces of 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile with passive adsorption from the headspace on Tenax TA and Carbotrap 300 Forensic Science International Volume 303, October 2019, 109933. [CrossRef]

- Analysis of the Toxicity Hazards of Methylene Chloride Associated with the Use of Tear Gas at the Branch Davidian Compound at Waco, Texas, on April 19, 1993.

- Gheorghe, V.; Gheorghe, C.G.; Bondarev, A.; Somoghi, R. Ecotoxicity of o-Chlorobenzylidene Malononitrile (CBM) and Toxicological Risk Assessment for SCLP Biological Cultures (Saccharomyces sp., Chlorella sp., Lactobacillus sp., Paramecium sp.). Toxics 2023, 11, 285. [CrossRef]

- 20. Yu-Chen Chang et all, The effect of different in situ chemical oxidation (ISCO) technologies on the survival of indigenous microbes and the remediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil Process Safety and Environmental Protection, Volume 163, July 2022, Pages 105-115. [CrossRef]

- V Gheorghe, CG Gheorghe, A Bondarev, CN Toader, The contamination effects and toxicological characterization of o-Chlorobenzylidene Manolonitrile Revista de chimie 71 (12), 67-75. [CrossRef]

- S R. Subashchandrabose et all., Bioremediation of soil long-term contaminated with PAHs by algal–bacterial synergy of Chlorella sp. MM3 and Rhodococcus wratislaviensis strain 9 in slurry phase, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 659, 1 April 2019, Pages 724-731. [CrossRef]

- M Chenet all., Study on soil physical structure after the bioremediation of Pb pollution using microbial-induced carbonate precipitation methodology, Journal of Hazardous Materials, Volume 411, 5 June 2021, 125103. [CrossRef]

- N Mohd Nasir et all., Utilization of microalgae, Chlorella sp. UMT LF2 for bioremediation of Litopenaeus vannamei culture system and harvesting using bio-flocculant, Aspergillus niger, Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, Volume 47, January 2023, 102596. [CrossRef]

- V. Gheorghe, C.G. Gheorghe et all., Synthesis, Purity Check, Hydrolysis and Removal of o-Chlorobenzyliden Malononitrile (CBM) by Biological Selective Media, Toxics, 2023, 11(8):672., doi: 10.3390/toxics11080672.

- Zhang Y et all., Photosynthesis Responses of Tibetan Freshwater Algae Chlorella vulgaris to Herbicide Glyphosate Int. J. Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Dec 26;20(1):386. [CrossRef]

- E. Posadas et. all., Influence of pH and CO2 source on the performance of microalgae-based secondary domestic wastewater treatment in outdoors pilot raceways Chemical Engineering Journal 265 (2015) 239–2.

- Slovacey, R.E. and Hanna, P.J. In vivo fluorescence determinations of phytoplancton chlorophyll, Limnology & Oceanography 22,5 (1977), p. 919-925. [CrossRef]

- SR 13328, 1996, R30, Wather quality. Aquatic organisms tests. Pollutants toxicity determinations compared to green algae ICS 1306040.

- OECD GUIDELINES FOR THE TESTING OF CHEMICALS of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),.

- R. Sirohi et. all., Design and applications of photobioreactors- a review Bioresource Technology 349 (2022) 126858. [CrossRef]

- C. G. Gheorghe, et all., Testing of Bacterial and Fungal Resistance in the Water Pollution with Cationic Detergents Chemistry Journal, 62 (7), 707-711.

- H Yu et. All., Weighted gene Co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) reveals a set of hub genes related to chlorophyll metabolism process in chlorella (Chlorella vulgaris) response androstenedione, Environmental Pollution Volume 306, 2022, 119360. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Porra, W.A. Thompson, P.E. Kriedemann Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 975 (1989) 384-394 Elsevier BBABIO 43036 , Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. (Biomedical Division).

- 35. S. Wei et. all., Biomass production of Chlorella pyrenoidosa by filled sphere carrier reactor: Performance and mechanism, Bioresour Technol., 2023 Sep:383:129195 Epub 2023. [CrossRef]

- 36. Yuanyuan Su et all., Biodegradable and conventional microplastics posed similar toxicity to marine algae Chlorella vulgarisAquatic Toxicology, Volume 244, March 2022, 106097. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, C.G.; Dusescu, C.; Carbureanu, M. Asphaltenes biodegradation in biosystems adapted on selective media. Rev. Chim. 2016, 67, 2106–2110.

- Gheorghe, C.G.; Pantea, O.; Matei, V.; Bombos, D.; Borcea, A.-F. Testing the behavior of pure bacterial suspension (Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Micrococcus luteus) în case of hydrocarbons contaminators. Rev. Chim. 2011, 62, 926–929.

- 39. CG Gheorghe, AFBorcea, Pantea, O, V. Matei, D. Bombos The Efficiency of Flocculants in Biological Treatment with Activated Sludge Revista de chimie 62 (10), 1023-1026.

- David WetzelJustin Murdock FT-IR Microspectroscopy Enhances Biological and Ecological Analysis of Algae Applied Spectroscopy Reviews 44(4):335-361 June 2009.

- D Surendhiran, MVijay Influence of bioflocculation parameters on harvesting Chlorella salina and its optimization using response surface methodology Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, Volume 1, Issue 4, December 2013, Pages 1051-1056. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Porra, W.A. Thompson, P.E. Kriedemann Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy Biochimica et biophysica Acta, 975 (1989) 384-394 Elsevier BBABIO 43036.

- 43. R. B. Flück Cellular toxicity pathways of inorganic and methyl mercury in the green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Scientific reports, 2017, 7: 8034. [CrossRef]

- L. Leadbeater, G.L. Sainsbury, D. Utley ortho-Chlorobenzylmalononitrile: A metabolite formed from ortho-chloro-benzylidenemalononitrile (CS) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 25 (1973), p. 111.

- Justin N. Murdock, David L. Wetzel, FT-IR Microspectroscopy Enhances Biological and Ecological Analysis of Algae, Applied Spectroscopy Reviews , Volume 44, Issue 4, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Eugene J. Olajos, Harry Salem Riot control agents: pharmacology, toxicology, biochemistry and chemistryJournal of Applied ToxicologyVolume 21, Issue 5Sep 2001, Pages 353-434. [CrossRef]

- J R. Riches et all., The development of an analytical method for urinary metabolites of the riot control agent 2-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile (CS), Journal of Chromatography B, Volume 928, 1 June 2013, Pages 125-130. [CrossRef]

- Ying Liang , John Beardall and Philip Heraud, Changes in growth, chlorophyll fluorescence and fatty acid composition with culture age in batch cultures of Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Chaetoceros muelleri (Bacillariophyceae), Botanica Marina, Volume 49 Issue 2 . [CrossRef]

- Li et. all., Toxicity of Tetracycline and Metronidazole in Chlorella pyrenoidosa Int J Environ Res Public Health , 2023 (4):3623. [CrossRef]

- 50. S. Sravan Kumar et all., Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis, chlorophyll content and antioxidant properties of native and defatted foliage of green leafy vegetables, Journal of Food Science and Technology volume 52, pages8131–8139 (2015). [CrossRef]

- 51. L. J. Hazeem et all., Investigation of the toxic effects of different polystyrene micro-and nanoplastics on microalgae Chlorella vulgaris by analysis of cell viability, pigment content, oxidative stress and ultrastructural changes Mar Pollut Bull , 2020, 156:111278. [CrossRef]

- Bastert J, Korting HC, Traenkle P, Schmalreck AF Identificationof Dermatophytes by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy.Mycoses , 1999, ISSN 09333. 42: 525-528.

- Hirschmugl, C.J., Bayarri, Z.E., Bunta, M., Holt, J.B., and Giordano, M. (2006) Analysis of the nutritional status of algae by Fourier transform infrared chemical imaging. Infrared Phys. Tech., 49: 57–63. 22.

- Rudolf E. Slovacek, Patrick J. Hannan, In vivo fluorescence determinations of phytoplankton chlorophyll “a” Lumnology and oceanography, Volume22, Issue5, September 1977, Pages 919-925, doi/10.4319/lo.1977.22.5.0919.

- R.J. Porra, W.A. Thompson, P.E. Kriedemann, Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics, Volume 975, Issue 3, August 1989, Pages 384-394. [CrossRef]

- A. Volgusheva et. all., Acclimation Response of Green Microalgae Chlorella Sorokiniana to 2,3',4,4',6-Pentachlorobiphenyl Photochem Photobiol. 2023, 99(4):1106-1114. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Dhivare1, S. S. Rajput Malononitrile: A Versatile Active Methylene Group , International Letters of Chemistry, Physics and Astronomy Online: 2015-08-04 ISSN: 2299-3843, Vol. 57, pp 126-144. [CrossRef]

- S.Hyun Park et all., A Study for Health Hazard Evaluation of Methylene Chloride Evaporated from the Tear Gas Mixture, Safety and Health at Work, Volume 1, Issue 1, September 2010, Pages 98-101. [CrossRef]

- Xiaoli Li et. All., Rapid Determination of Chlorophyll “a”and Pheophytin in Green Tea Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, Molecules 2018, 23(5), 1010. [CrossRef]

- Yu Gao et all., Colorimetric and turn-on fluorescent chemosensor with large stokes shift for sensitively probing cyanide anion in real samples and living systems, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, Volume 271, 15 April 2022, 120882. [CrossRef]

- A Marcek Chorvatova et all., Time-resolved endogenous chlorophyll fluorescence sensitivity to pH: study on Chlorella sp. algae Methods Appl Fluoresc, 2020, Mar 2;8(2):024007. [CrossRef]

- Yuna Jung et all.,Latent turn-on fluorescent probe for the detection of toxic malononitrile in water and its practical applications, Analytica Chimica Acta, Volume 1095, 25 January 2020, Pages 154-161. [CrossRef]

- M Valicaa, M Pipíškaa,, S. Hostina Effectiveness of Chlorella vulgaris inactivation during electrochemical water treatment Desalination and Water Treatment 138 (2019) 190–199.

- G. M. Vingiani Microalgal Enzymes with Biotechnological Applications, Mar. Drugs 2019, 17 (8), 459. [CrossRef]

- Qiang Xiong et all. Ecotoxicological effects of enrofloxacin and its removal by monoculture of microalgal species and their consortium Environmental PollutionVolume 226, July 2017, Pages 486-493. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).