1. Introduction

Repeated exposure to environmental stress (such as pathogens) leads to the evolutionary selection of adaptive traits. Many species transfer immunological memory to their offspring to meet immune challenges. In mammals, including humans, known to possess adaptive immune systems, intergenerational protection is achieved by the transfer of antibodies through the placenta or breast milk; other vertebrates, such as birds and fish, transfer antibodies to their offspring via their eggs. Plants and invertebrates that lack the adaptive immunity, pass their defense experience to their progeny through their DNA by boosting the non-specific defenses that make up their offspring’s innate immune system with the advantage of lifelong generational protection [

1].

Transfer factor is among the many mechanisms in humans where transfer of immunological memory can be achieved for enhanced immunological response by a recipient. Multiple hypothesis has been proposed regarding the nature of transfer factor. While some suggest that transfer factor is one or more peptide(s) with the capacity to produce immediate and/or delayed immunological response with molecules mass range of > 3,500 and <12,000 Da, others suggested that transfer factor is a single substance that achieves diverse responses by acting on various cellular receptors [

2]. Likewise, multiple mechanisms of action (MOA) have been proposed for transfer factor. Perhaps the most consistent MOA of transfer factor is at the level of cell-mediated immunity where transfer factor could transmit the ability to express delayed hypersensitivity reactions, and cell-mediated immunity from an individual or donor previously sensitized with an antigen to a non-immune or non-sensitized receptor. This knowledge has advanced its usage for prevention of infections (viral, parasitosis, fungal and mycobacterial), primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs), atopy and cancer [

3]. While the main effects of transfer factors on the immune system are reported as expression of delayed-type hypersensitivity, there still is a possibly that the action is nonspecific that could produce a generalized adjuvant effect leading to an amplified immune response [

4]. In fact, immunologically active peptides have been identified from non-antigen-specific human dialyzed lymphocyte extract produced at the National School of Biological Sciences (IPN, National Polytechnic Institute) [

5] suggesting individuals whose immune systems are intact could gain the benefit of the transfer factor like moiety effect to bolster and strengthen their immune system.

Besides human blood with antigen specificity, other sources of transfer factor such as bovine leukocyte, bovine colostrum and egg yolk have been reported [

6,

7,

8]. Nonantigen specific transfer factor from bovine colostrum and egg yolk sources have been used as oral supplements on the market for nonspecific generalized innate immune support in humans. Despite its significant beneficial effect, the widespread application of transfer factor is limited due to its scarce animal origins sourcing and sustainability. These factors warrant the search for an alternative from natural plant source. In the current report, plant protein/peptides were considered as an alternative source and screened for their efficacy.

Plants have a complex immune system to recognize and protect themselves against pathogens. Plants lack circulating defender cells and an adaptive immune system [

9]. Instead, they have evolved their innate immune system to recognize damage associated molecular patterns and pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern recognizing receptors to launch diverse pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) [

10]. Plant peptides play a significant role in plant defense. Plant defense peptides are believed to be proteins at length of < 100 amino acids [

11]. Well characterized, biologically active plant peptides could have beneficial effects in humans to enhance the innate immune response for a robust protection against daily immune challenges.

Small molecules such as brassinosteroids [

12], gibberellins [

12], kinetin [

13] and peptides like systemins [

14] play important roles in plant innate immunity. In this study, we sought to find plant-based proteins/peptides that behave like a transfer factor to boost human innate immunity. Based on the prior reports of defense peptides in plant immunity [

10,

15,

16,

17,

18] and in-house high-protein- plant study, 4,331 plants in Unigen Phytologix library were screened and a total of 100 plants were selected for this study to isolate those with high protein contents and prior use as immune boosters

The use of cryopreserved human PBMCs in functional and phenotypic immunological assays has granted significant understanding about the role of NK cell function. Natural killer (NK) cells are potent effectors of the innate immune system and form the first line of defense. They are members of the innate immune cell family and characterized in humans by expression of the phenotypic marker CD56 in the absence of CD3. NK cells are the most abundant innate cytotoxic lymphoid in humans with an immediate cytotoxic effect. NK cells do not require prior antigen-priming for their activity, instead their activation is initiated by various receptors with activating or inhibitory functions. NK cells produce diverse cytokines growth factors and chemokines that could shape the immune response of a host by interacting with dendritic cells, macrophages, and T cells [

19]. As NK cells constitute 5-30% of PBMCs [

20,

21], in our primary screening we used PBMCs cytotoxic assay to assess the NK cytotoxic effect against human cancerous lymphoblast cells - K562 cells after incubation with plant peptides through presumed increased activity of NK-cells as an effector without the need for purified NK cells.

2. Results

2.1. Primary screening

PBMCs were incubated overnight with 50 and 100 μg/mL of Aqueous extracts (AE) of the 100 selected plants in duplicate, with water as a vehicle, and IL-2 (20 μg/mL) and Colostrum-based TF (C-TF hereafter) (500 μg/mL) were used as positive controls. K562s were added the next day in a ratio of 25:1 effector:target cells, and a K562 well with no PBMCs was also used as a control. This ratio was selected based on data collected at the time of method optimization. Percent cytotoxicity (measure of effectiveness) of each sample was normalized to the negative control, which had PBMCs and K562s incubated together without pre-treatment, and to the IL-2 positive control, which was set to 100% cytotoxicity

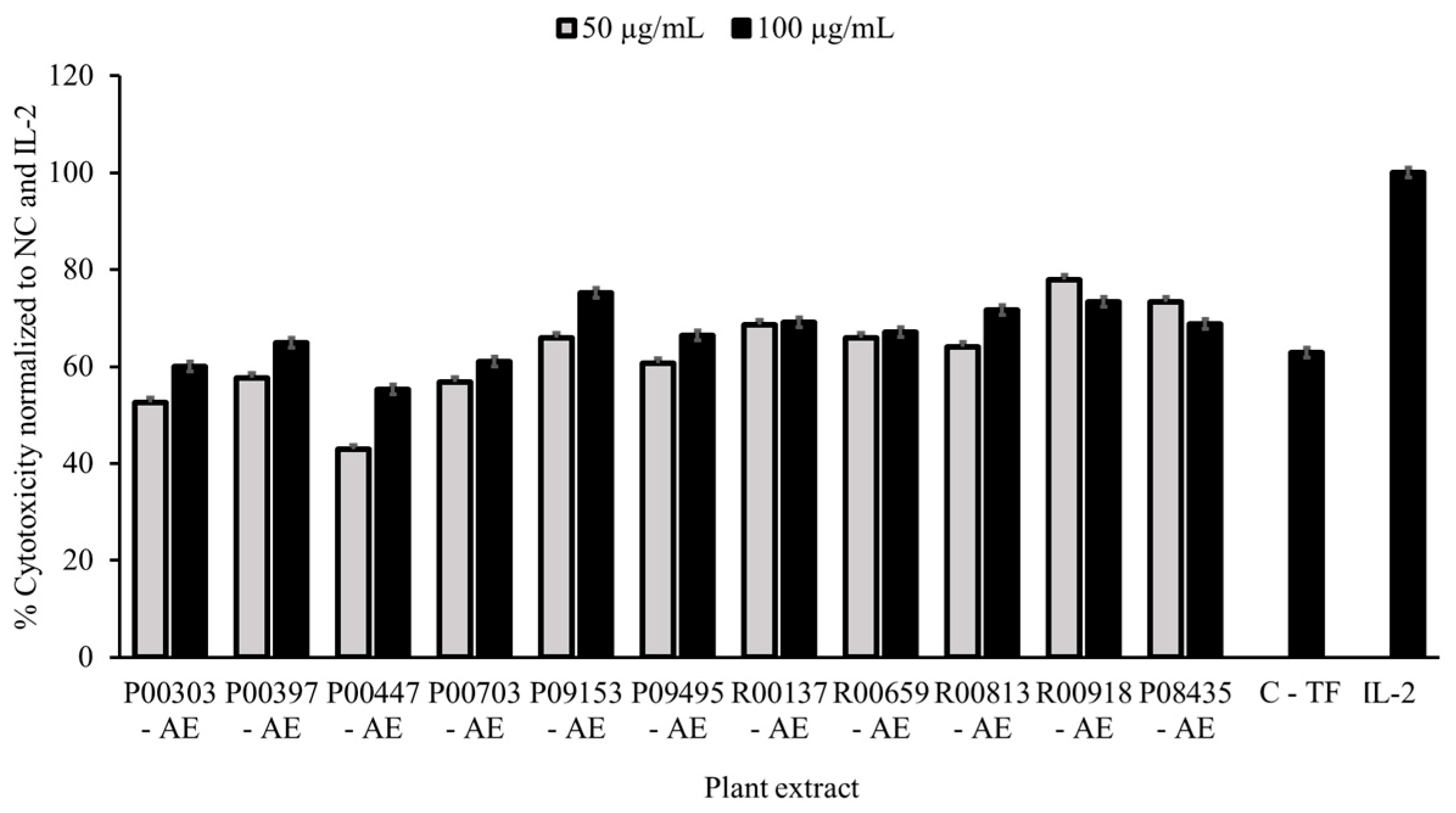

Eleven plant aqueous extracts (AEs) showed significant efficacy in K562 cell killing resulting in 11% hit rate (

Table 1) with the percentage cell killing at 100 μg/mL higher than colostrum as a positive control at 500 μg/mL Effectiveness ranges of 42.9 - 77.9% and 55.3% - 75.2% were observed for these plant extracts at 50 and 100 μg/mL concentration, respectively. These effects were dose correlated for P00303, P00397, P00447, P00703, P09153, P09495 and R00813. While there was no difference in inhibition of growth between the two concentrations for R00137 and R00659, slight increased inhibition in growth at 50 μg/mL than 100 μg/mL was observed for R00918 and P08435 (

Figure 1).

Table 1.

Primary screening hits of Aqueous extracts tested on PBMC assay.

Table 1.

Primary screening hits of Aqueous extracts tested on PBMC assay.

| NO. |

UP_ID |

Species |

Common names |

Part |

Extract* |

| 1 |

P00303 |

Raphanus Sativus |

Radish |

Seed |

AE |

| 2 |

P00397 |

Brassica Juncea |

Mustard greens |

Seed |

AE |

| 3 |

P00477 |

Dendrocalamus Strictus |

Calcutta Bamboo |

Seed |

AE |

| 4 |

P00703 |

Alstonia Scholaris |

Blackboard tree |

Bark |

AE |

| 5 |

P08435 |

Sorghum Bicolor |

Great millet |

Leaf-Stem |

AE |

| 6 |

P09153 |

Solanum Incanum |

Bitter apple |

Fruit |

AE |

| 7 |

P09495 |

Zea Mays |

Corn |

Corn silk |

AE |

| 8 |

R00137 |

Cocos Nucifera |

Coconut |

Fruit meat |

AE |

| 9 |

R00659 |

Beta Vulgaris |

Beet |

Root |

AE |

| 10 |

R00813 |

Taraxacum Officinale |

Common dandelion |

Leaf |

AE |

| 11 |

R00918 |

Psoralea Corylifolia |

Babchi |

Fruit |

AE |

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity data as a measure of activity for primary screening. PBMC cells (250,000 cells/well) in 96-well plate were treated with 50 and 100 μg/mL AE plant extracts overnight in parallel with untreated cells. Cells treated with colostrum-based transfer factor (C-TF) at 500 μg/mL, and IL-2 at 20 μg/mL were used as references. K562 cells were then added to PBMCs at a density of 10,000 cells/well at 25:1 effector:target cell ratio. The plates were scanned for green, fluorescent Calcein-AM on an ImagExpress Pico every hour for four hours. The number of surviving K562 cells was normalized to the untreated control and the IL-2 control. Data are expressed as percent cytotoxicity. NC= normal control.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity data as a measure of activity for primary screening. PBMC cells (250,000 cells/well) in 96-well plate were treated with 50 and 100 μg/mL AE plant extracts overnight in parallel with untreated cells. Cells treated with colostrum-based transfer factor (C-TF) at 500 μg/mL, and IL-2 at 20 μg/mL were used as references. K562 cells were then added to PBMCs at a density of 10,000 cells/well at 25:1 effector:target cell ratio. The plates were scanned for green, fluorescent Calcein-AM on an ImagExpress Pico every hour for four hours. The number of surviving K562 cells was normalized to the untreated control and the IL-2 control. Data are expressed as percent cytotoxicity. NC= normal control.

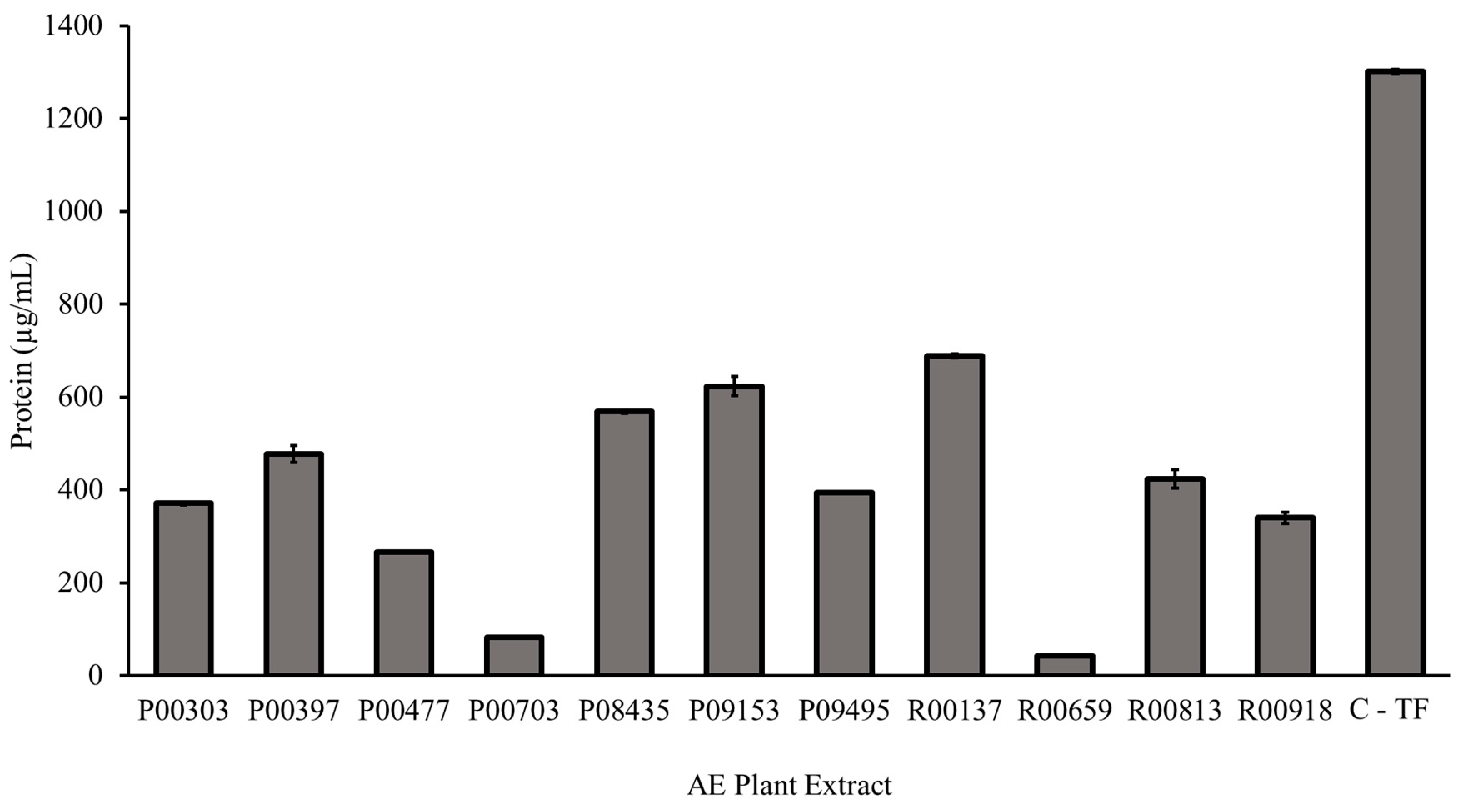

2.2. Protein Content as measured by Bradford assay

The eleven primary hits from the screening were tested in the Bradford Assay for their protein content as described in the methods. Each AE plant extract contained measurable protein. The highest protein content, 688.4 µg/mL, was found in aqueous extract R00137. The least protein content, 43.4 µg/mL, was found in aqueous extract R00659. The C- TF showed 1301.5 µg/mL of total proteins.

Figure 2.

Protein content of 11 primary hits from AE plant extract as measured by Bradford assay. A Bradford assay was used to determin the concentration of protein in each AE plant extract compared to C-TF. 5 μL of standards and plant AE samples were added to 250 μL Bradford Reagent. The assay was incubated for five minutes at room temperature before the absorbance was read at 595 nm. The protein concentration of the aqueous extracts was calculated using a Bovine Serum Albumin standard curve.

Figure 2.

Protein content of 11 primary hits from AE plant extract as measured by Bradford assay. A Bradford assay was used to determin the concentration of protein in each AE plant extract compared to C-TF. 5 μL of standards and plant AE samples were added to 250 μL Bradford Reagent. The assay was incubated for five minutes at room temperature before the absorbance was read at 595 nm. The protein concentration of the aqueous extracts was calculated using a Bovine Serum Albumin standard curve.

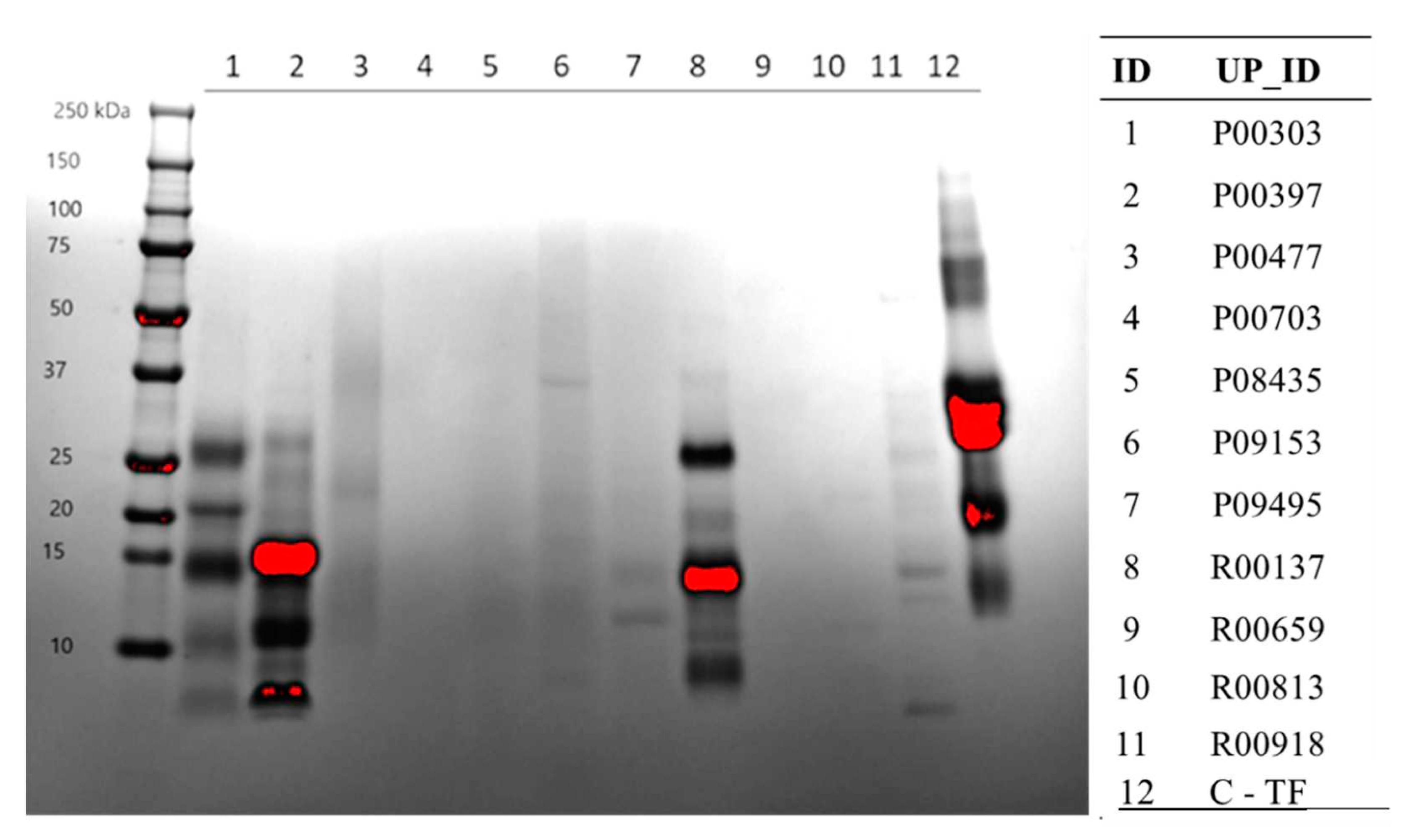

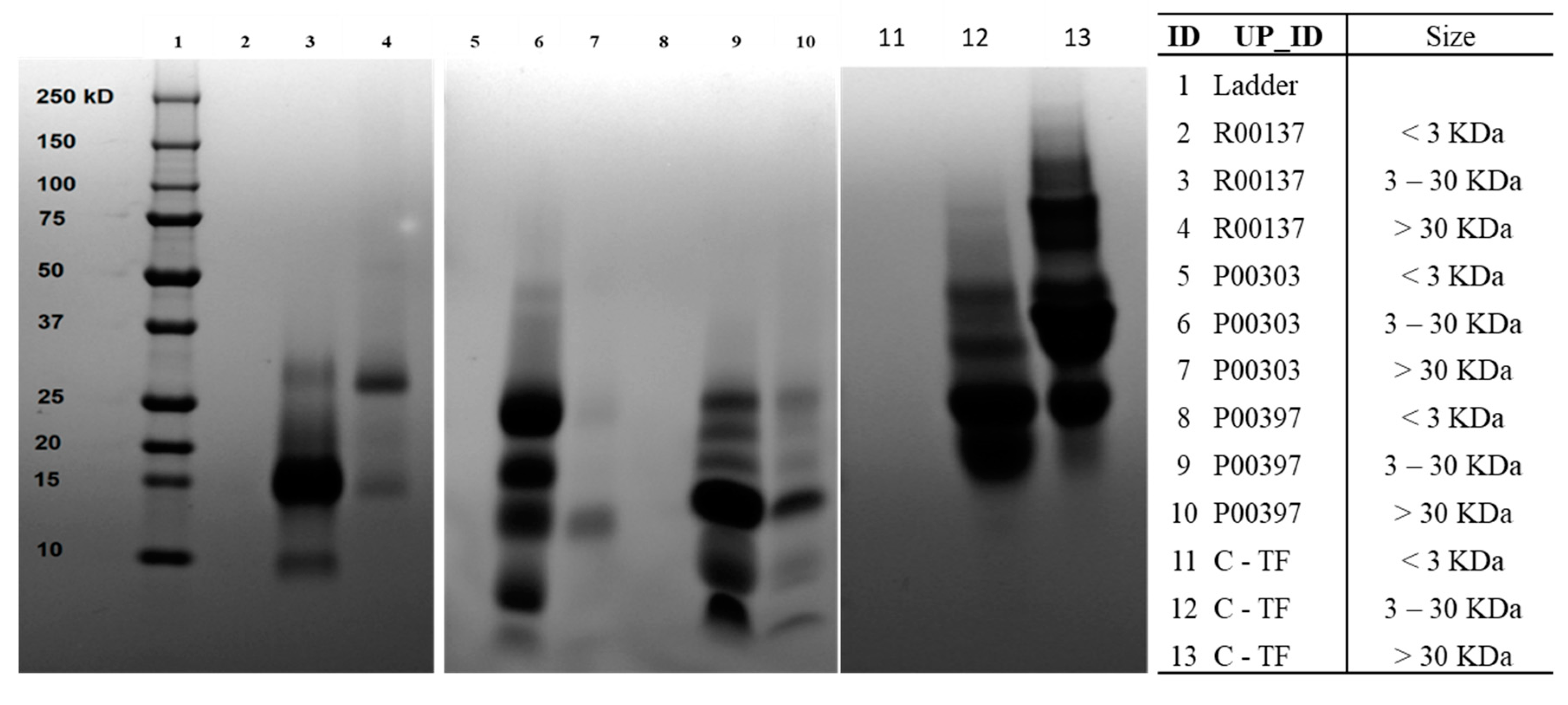

2.3. Protein content on SDS-Page gel

Protein content from the AE extracts of the 11 primary hits were further confirmed on SDS-PAGE gels stained with Coomassie Blue. Here again, extract R00137 showed significant protein content followed by P00303, and P00397. The majority of the protein in these extracts seem to be less than 30 KDa. At least in this method, the protein content for the other extracts was very minimal.

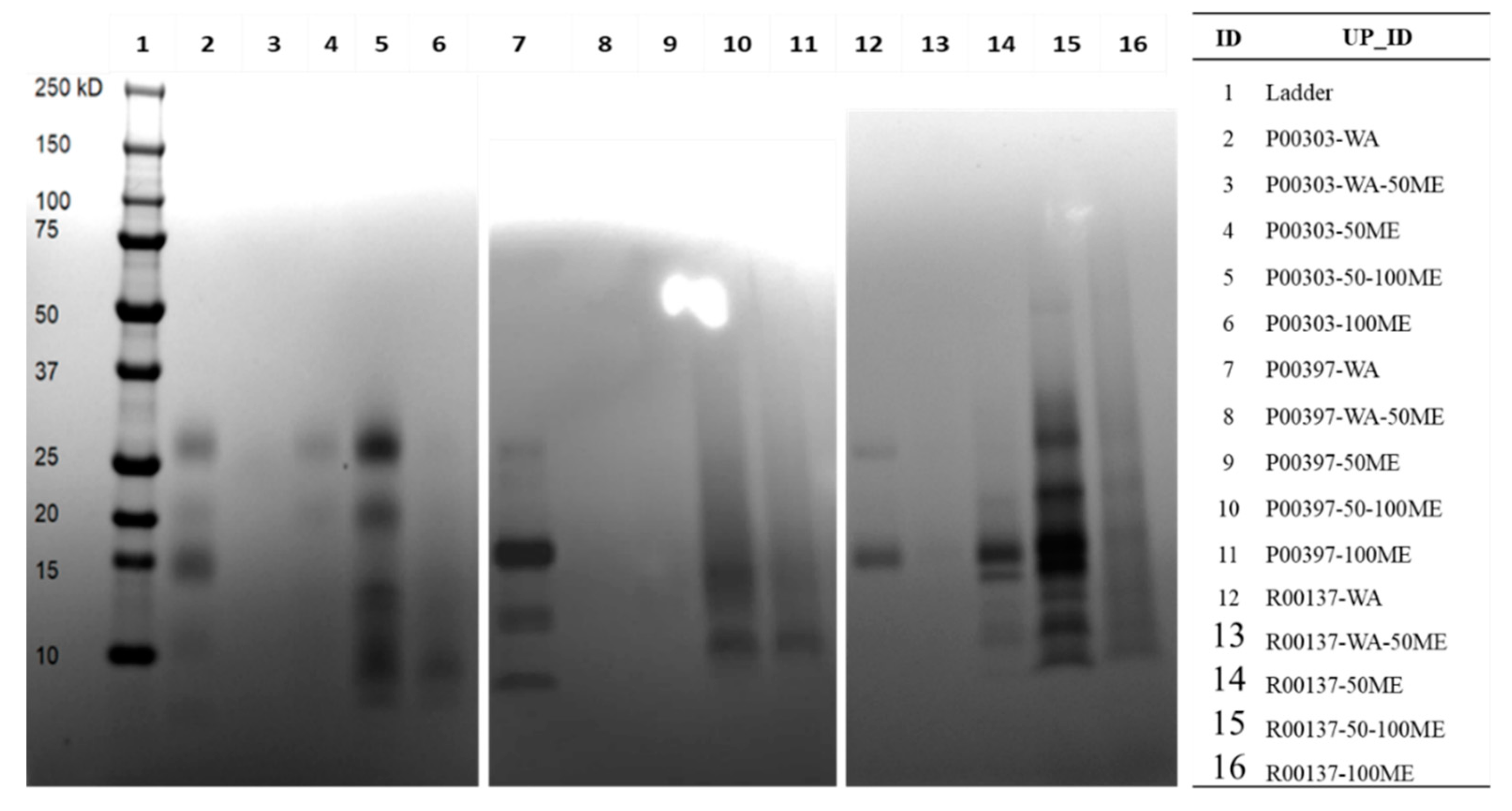

Figure 3.

Confirmation of protein content from the AE extracts of the 11 primary hits on SDS page. An SDS-Page gel visualized protein content of each plant extract denatured in SDS Sample Buffer and resolved by Tris-Tricine gradient gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie for one-hour and destained three times for 30 minutes each with 45% methanol, 10% glacial acetic acid. The gel shows that the extracts with the highest protein content in the range of the gel, were P00303, P00397, R00137, and C-TF.

Figure 3.

Confirmation of protein content from the AE extracts of the 11 primary hits on SDS page. An SDS-Page gel visualized protein content of each plant extract denatured in SDS Sample Buffer and resolved by Tris-Tricine gradient gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie for one-hour and destained three times for 30 minutes each with 45% methanol, 10% glacial acetic acid. The gel shows that the extracts with the highest protein content in the range of the gel, were P00303, P00397, R00137, and C-TF.

2.4. Methanol Fractions of top 3 hits on SDS page

C18 column fractions as illustrated in the methods for the top 3 protein-rich extracts were run on SDS-PAGE to visualize the approximate size and protein contents in those column fractions. Distinct bands of proteins were found in the water fractions for all 3 top hits, P00303, P00397, and R00137 (

Figure 4). It was noticed that there was interference in some of the high methanol fractions, likely because of water insoluble material loaded into the wells of the gels causing streaking.

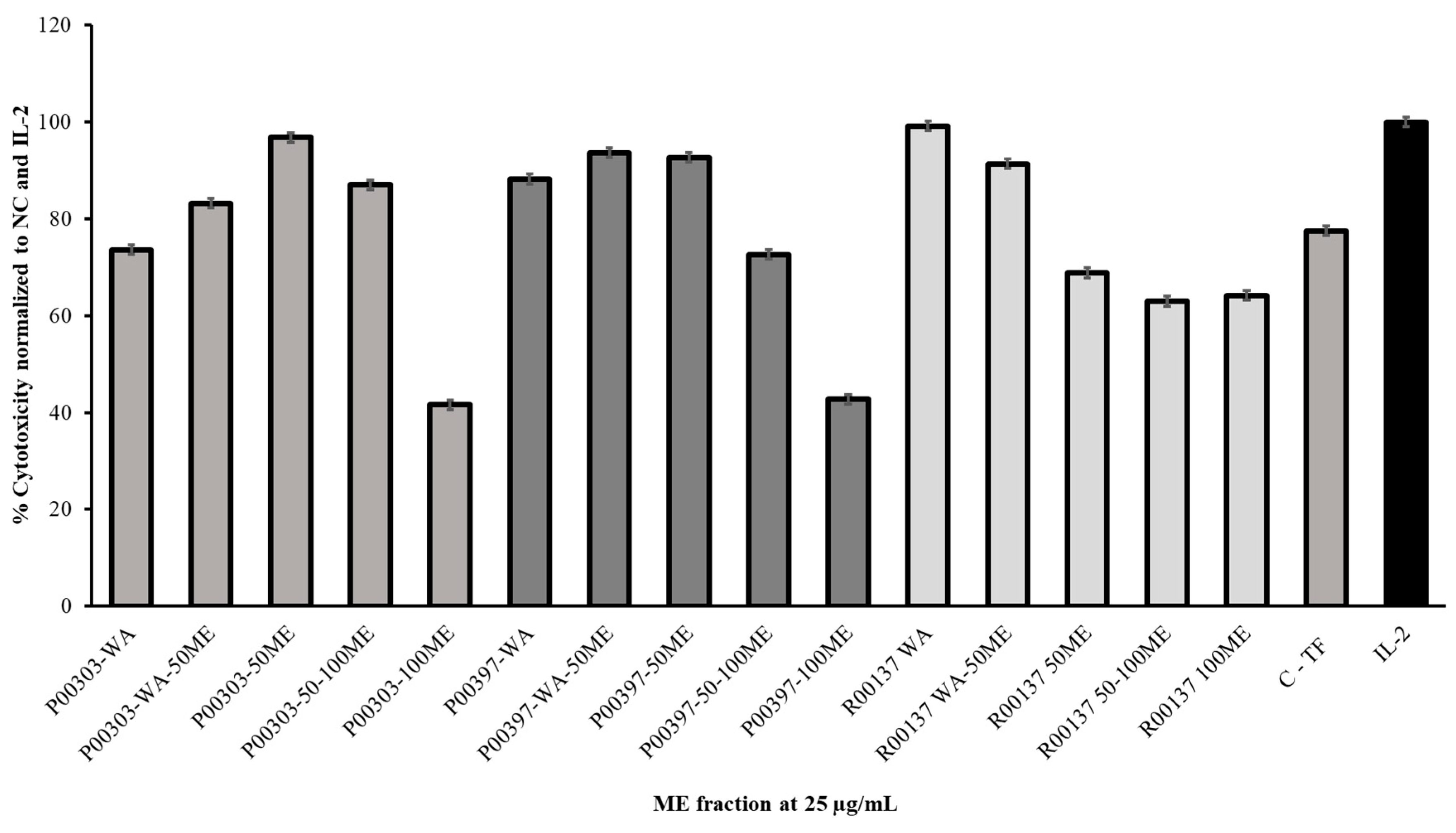

2.5. Activity of C18 column fractionated AE extracts

Aqueous extracts of the 11 top hits were fractionated on a C18 column with a methanol gradient before activity evaluation.

Table 2.

Yields from the C18 column fractionation of the three selected top hits.

Table 2.

Yields from the C18 column fractionation of the three selected top hits.

| ID |

Species |

Part |

Extract (mg) |

WA

(mg) |

WA-50ME |

50ME

(mg) |

50-100ME |

100ME

(mg) |

| C-TF |

- |

- |

1017.3 |

1342.0 |

57.7 |

21.2 |

7.4 |

8.2 |

| P00303 |

Raphanus Sativus |

seed |

2657.0 |

2889.5 |

134.5 |

285.7 |

40.7 |

17.7 |

| P00397 |

Brassica Juncea |

seed |

2083.7 |

2959.4 |

120.5 |

133.4 |

16.6 |

14.6 |

| R00137 |

Cocos Nucifera |

fruit meat |

894.4 |

468.7 |

54.6 |

29.6 |

6.5 |

7.6 |

All c18 column fractions were tested for PBMC cytotoxicity at 25 μg/mL. Measurable activity was observed for each of the fractionates. It was found that fractionated P00303-50ME had the highest activity for the P00303 AE while the P00303-100ME fractionate showed the least activity. In the case of P00397, the highest activity was located at P00397-WA-50ME and P00397-50ME. The least activity was observed at P00397-100ME. P00137 methanol fractionate showed the highest activity for fractionate P00137-WA while the least activity was observed at P00137-50-100ME.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxic effects of top hit C18 column fractionated AE extracts on Calcein-AM stained target cells normalized to the negative and IL-2 controls. Samples were tested at 25 μg/mL. C-TF (500 µg/mL) and IL-2 (20 µg/mL). PBMC cytotoxicity assay using human cancerous lymphoblast cells (K562 cells) as a target was utilized. WA: water; WA-50ME: water to 50% MeOH; 50ME: 50% MeOH; 50-100ME: 50%-100% MeOH; 100ME: 100% MeOH.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxic effects of top hit C18 column fractionated AE extracts on Calcein-AM stained target cells normalized to the negative and IL-2 controls. Samples were tested at 25 μg/mL. C-TF (500 µg/mL) and IL-2 (20 µg/mL). PBMC cytotoxicity assay using human cancerous lymphoblast cells (K562 cells) as a target was utilized. WA: water; WA-50ME: water to 50% MeOH; 50ME: 50% MeOH; 50-100ME: 50%-100% MeOH; 100ME: 100% MeOH.

2.6. Ultrafiltration of high-protein hits

The C18 column water fractions (WA) from the aqueous extracts of the top three hits were further investigated. The water fraction was ultrafiltrated as illustrated in the method into three sub-fractions based on the molecular weight: <3 kDa, 3-30 kDa, and >30 kDa. These sizes were selected based on the majority of the proteins detected on the SDS-PAGE of the top hits. The yields from the ultrafiltration are shown in

Table 3.

The ultrafiltration fractions were run on SDS-PAGE to ensure adequate protein segregation. The 3-30 KDa was found to be the prominent protein in all the top hits that were similar to the molecular weight distribution of Colostrum C18 column water fraction. The colostrum-based TF also contained proteins with molecular weights at 3-30 KDa and >30 KDa.

Figure 6.

SDS-Page gel protein content of ultrafiltrate fractions from WA fraction of top 3 AE hits (R00137, P00303, and P00397.). 250 mg column fraction dried sample was dissolved into 125 mL DI water and used for ultrafiltration. The 3 kDa and 30 kDa membrane discs were used for size segregation of ultrafiltrates. All the ultrafiltration fractions were freeze-dried to remove water and get powdered materials. Each hit was tested at <3 kDa, 3-30 kDa and > 30kDa.

Figure 6.

SDS-Page gel protein content of ultrafiltrate fractions from WA fraction of top 3 AE hits (R00137, P00303, and P00397.). 250 mg column fraction dried sample was dissolved into 125 mL DI water and used for ultrafiltration. The 3 kDa and 30 kDa membrane discs were used for size segregation of ultrafiltrates. All the ultrafiltration fractions were freeze-dried to remove water and get powdered materials. Each hit was tested at <3 kDa, 3-30 kDa and > 30kDa.

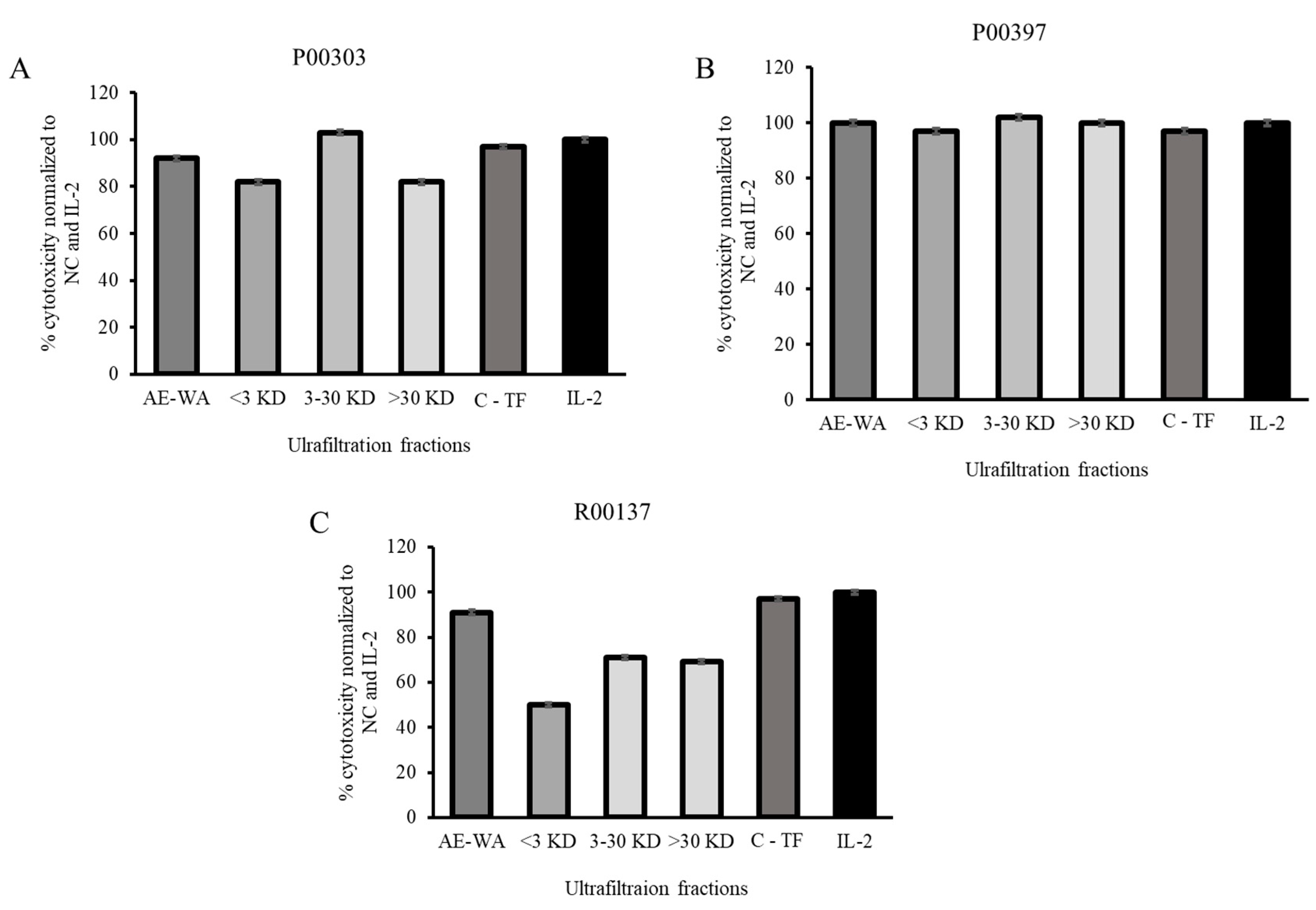

2.7. Activity of ultrafiltrates

The ultrafiltrates were tested for their activity in the PBMC cytotoxicity assay at 12.5 μg/mL. This concentration was chosen in order to discriminate between the fractions with activity at higher concentrations that could be easily saturated the PBMC assay. The AE extract of each top hit was tested at the same concentration as that of the ultrafiltrate. It was found that, in the case of P00303, the 3-30 KDa fraction was the one with the highest activity. This activity was better than the original AE extract at the same concentration and was also comparable to the positive controls TF and IL-2. All three fractions of the P00397 showed comparable activity compared to the original AE extract and comparable to the controls TF and IL-2. None of the fractions of the P00137 showed activity better than the original AE extract or the controls C-TF and IL-2.

Figure 7.

Cytotoxic effects of the three ultrafiltration fractionated samples on Calcein-AM stained target cells normalized to the negative, C-TF (500 µg/mL) and IL-2 (20 µg/mL) controls. The ultrafiltrates were tested for their activity in the PBMC cytotoxicity assay at 12.5 μg/mL. A: P00303; B: P00397, C: R00137.

Figure 7.

Cytotoxic effects of the three ultrafiltration fractionated samples on Calcein-AM stained target cells normalized to the negative, C-TF (500 µg/mL) and IL-2 (20 µg/mL) controls. The ultrafiltrates were tested for their activity in the PBMC cytotoxicity assay at 12.5 μg/mL. A: P00303; B: P00397, C: R00137.

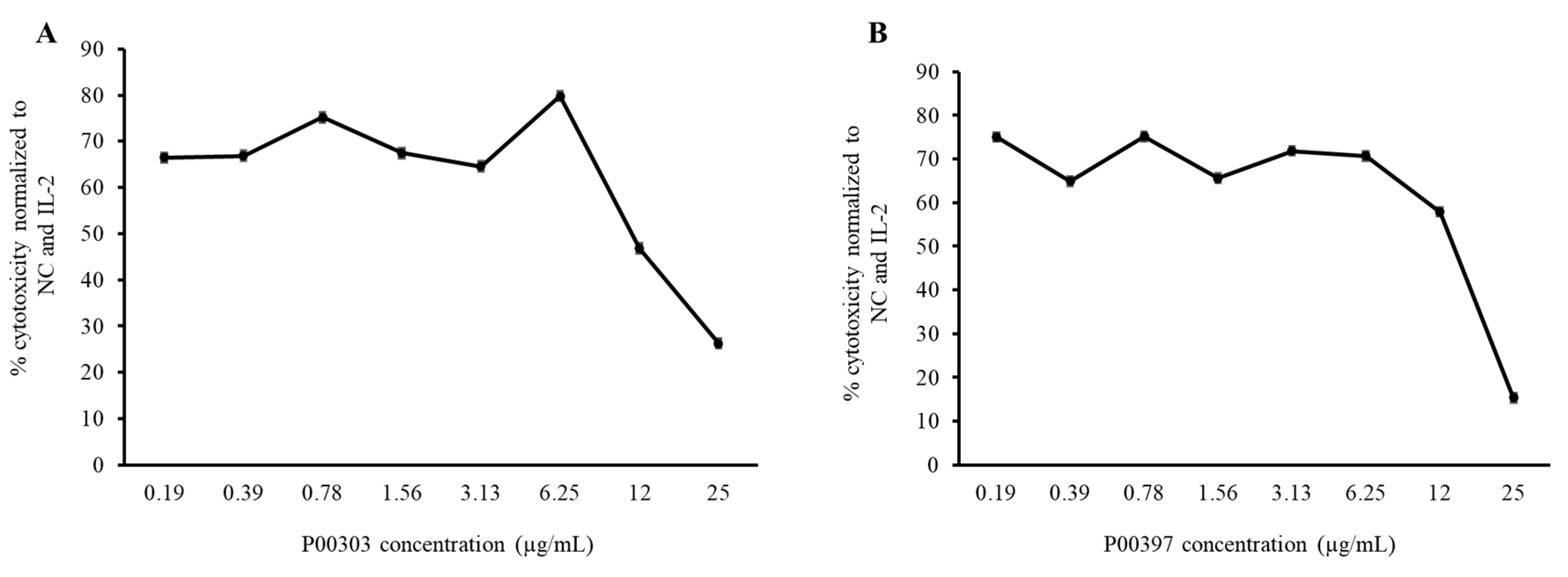

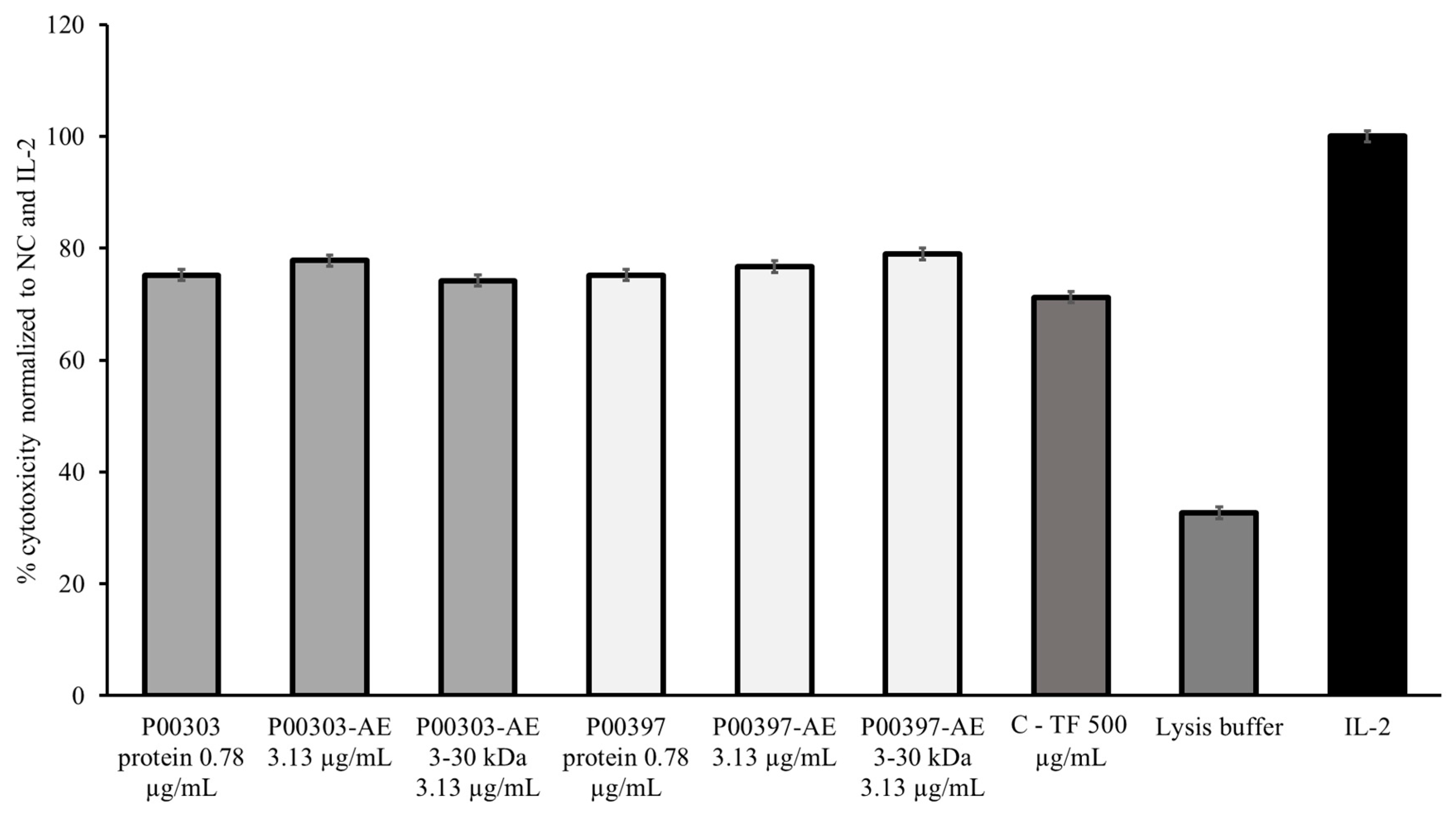

2.8. PBMC cytotoxic Activity confirmation

P00303 and P00397 were selected as the final leads due to their high protein content and high activity in the 3-30 kDa ultrafiltration fractions. Activity of these top leads were confirmed in the PBMC cytotoxicity assay using extraction method focused on protein from the plant parts (i.e., seed) compared against to the original AE extracts and the 3-30 kDa ultrafiltration fractions. To confirm activity, we extracted proteins from raw seed materials and tested them in the PBMC cytotoxicity assay at eight concentrations (0.19, 0.39, 0.78, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12, and 25 μg/mL) (

Figure 8). Higher concentrations showed less activity due to interference with the lysis buffer.

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity dose curve of protein from P00303 (A) and P00397 (B) seed extracts. PBMC cytotoxicity assay using human cancerous lymphoblast cells( K562 cells) as a target was carreid out at eight concentrations (0.19, 0.39, 0.78, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12, and 25 μg/mL).

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity dose curve of protein from P00303 (A) and P00397 (B) seed extracts. PBMC cytotoxicity assay using human cancerous lymphoblast cells( K562 cells) as a target was carreid out at eight concentrations (0.19, 0.39, 0.78, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12, and 25 μg/mL).

Because of the strong and similar activity observed at 0.78 μg/mL in both P00303 and P00397-treated PBMCs, this concentration was chosen to compare to the original AE extracts and the 3-30 kDa ultrafiltration fractions. The P00303 protein extract at 0.78 μg/mL was compared to the original P00303 AE at 3.13 μg/mL and the P00303 AE-WA 3-30 kDa ultrafiltrate fraction at 3.13 μg/mL. The 0.78 μg/mL protein is comparable to the level of protein calculated by the Bradford Assay in the aqueous extract at 3.13 μg/mL. The same concentrations were tested for P00397. Ranges of effectiveness from 74.2 – 77.8% and 75.2 – 79.0% were observed for the P00303 and P00397, respectively. All fractions, extracts, and purified protein tested exhibited comparable or higher activity as the C-TF confirming their effectiveness in this assay (

Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Cytotoxic effects of the ultrafiltrate fractionated samples from P00303 and P00397 compared to protein extracts on Calcein-AM stained target cells normalized to the negative, C-TF (500 µg/mL) and IL-2 (20 μg/mL) controls. The P00303 and P00397 protein extract at 0.78 μg/mL was compared to the original P00303/ P00397 AE at 3.13 μg/mL and the P00303/ P00397 AE-WA 3-30 kDa ultrafiltrate fraction at 3.13 μg/mL. PBMC cytotoxicity assay using human cancerous lymphoblast cells (K562 cells) as a target was used for the caomparison.

Figure 9.

Cytotoxic effects of the ultrafiltrate fractionated samples from P00303 and P00397 compared to protein extracts on Calcein-AM stained target cells normalized to the negative, C-TF (500 µg/mL) and IL-2 (20 μg/mL) controls. The P00303 and P00397 protein extract at 0.78 μg/mL was compared to the original P00303/ P00397 AE at 3.13 μg/mL and the P00303/ P00397 AE-WA 3-30 kDa ultrafiltrate fraction at 3.13 μg/mL. PBMC cytotoxicity assay using human cancerous lymphoblast cells (K562 cells) as a target was used for the caomparison.

2.8. Protein Identification

LC-MS/MS analysis and protein sequencing were carried out for 3-30 kDa ultrafiltration fractions from P00303 and P00397 at Applied Biomics (Hayward, CA) for protein identification. Briefly, the proteins were reduced and alkylated, trypsin digested, and subjected them to nano LC-MS/MS. Homologous protein sequences were searched using the Brassicaceae taxonomy database from the National Center for Biotechnology Information at the National Institutes of Health and generated a list of the proteins identified (

Table 4 and

Table 5). Proteins that were non-native to the plant that was queried (P00303, R. sativus or P00397, B. juncea) were assessed for homology to the queried species. This homology is listed on the right-most column of

Table 4 and

Table 5.

The 3-30 kDa fraction of P00303, Raphanus sativus, contained 17 proteins. Seven of them were known storage proteins, with five of those identified from R. sativus sequences, and two from related species of same genus plant with high homology to R. sativus (

Table 4). There was one R. sativus Defensin protein that accounted for 3% of the total protein in the sample, and there was a kunitz trypsin inhibitor, which is a protease that protects the seed proteins from being degraded by their environment. The remaining nine proteins were in low abundance, and they included one cell wall adaptation protein and one cell signaling protein. Many of the others were hypothetical or uncharacterized, or they had known domains but unknown function (the complete list of proteins is available at the supplement section).

The 3-30 kDa fraction of P00397, Brassica juncea, had 61 proteins (

Table 5). The seven most abundant proteins were all seed storage proteins, Napin, and 2S seed storage proteins. Allergen Bra j 1-E, the only protein found that is native to B. juncea, is also a 2S seed storage protein. There were a number of plant defense and stress response genes that were expressed, including Chitin-binding allergen Bra r 2, which is involved in PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) in plants. The others were involved in defense against microorganisms or environmental stress (the complete list of proteins is available at the supplement section).

Table 5.

Proteins in P00397 Brassica juncea 3-30 kDa fraction sorted from most to least abundant.

Table 5.

Proteins in P00397 Brassica juncea 3-30 kDa fraction sorted from most to least abundant.

| Accession No.* |

Protein Name |

emPAI |

emPAI % |

MW

(kDa) |

% Homology to B. juncea

|

Function |

| gi|75107016 |

Napin-3 [Brassica napus] |

6.90 |

19.76% |

14.04 |

79% |

storage |

| gi|32363444 |

Allergen Bra j 1-E [Brassica juncea] |

6.21 |

17.78% |

14.65 |

|

storage |

| gi|2440684703 |

2S seed storage protein 4 [Raphanus sativus] |

4.44 |

12.71% |

20.14 |

84% |

storage |

| gi|2440727853 |

2S seed storage protein 4 [Raphanus sativus] |

2.23 |

6.39% |

20.83 |

85% |

storage |

| gi|112747 |

Napin embryo-specific [Brassica napus] |

2.19 |

6.27% |

21.02 |

82% |

storage |

| gi|2440727854 |

2S seed storage protein 4 [Raphanus sativus] |

1.66 |

4.75% |

19.94 |

85% |

storage |

| gi|2440715477 |

2S seed storage protein 4 [Raphanus sativus] |

1.65 |

4.73% |

19.97 |

82% |

storage |

| gi|32363456 |

Chitin-binding allergen Bra r 2 [Brassica rapa] |

1.59 |

4.55% |

10.05 |

54% |

Plant defense |

| gi|2334150478 |

Protein C2-DOMAIN ABA-RELATED 6 [Hirschfeldia incana] |

0.31 |

0.89% |

18.16 |

None |

Stress response |

| gi|2440705714 |

Pathogenesis-related thaumatin superfamily protein [Raphanus sativus] |

0.20 |

0.57% |

27.09 |

34% |

Plant defense |

| gi|2440692471 |

PHD finger protein ALFIN-LIKE 6 [Raphanus sativus] |

0.19 |

0.54% |

27.77 |

None |

Stress response |

| gi|2440680072 |

Tubby-like F-box protein 10 [Raphanus sativus] |

0.13 |

0.37% |

41.35 |

33% |

Stress response |

| gi|2440705359 |

DNAJ heat shock N-terminal domain-containing protein [Raphanus sativus] |

0.13 |

0.37% |

41.18 |

52% |

Stress response |

| gi|2440697973 |

Protein RESTRICTED TEV MOVEMENT 2 [Raphanus sativus] |

0.12 |

0.34% |

43.38 |

None |

Stress response |

| gi|2440688005 |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 2 member C4 [Raphanus sativus] |

0.09 |

0.26% |

54.28 |

None |

Stress response |

| gi|2440711253 |

Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase [Raphanus sativus] |

0.04 |

0.11% |

114.72 |

None |

Stress response |

3. Discussion

In the search for plant-based peptides that possess characteristics with a potential of increasing immune responses, we screened a total of 100 protein rich aqueous plant extracts in PBMC cytotoxic assay known to contain high percentage of NK cells. Aqueous extract was chosen understanding that the plant peptides are more likely to reside in the water extract than organic extract. A colostrum-based transfer factor was used for comparative analysis. Raphanus sativus (radish) or Brassica juncea (mustard) were determined to have higher contents of protein and showed higher cytotoxic activities than the reference colostrum controls. Subsequent protein identification of ultrafiltrates from water extract with molecular mass 3-30kDa, the top two leads, Raphanus sativus and Brassica juncea, were found to contain more storage protein than proteins involved in plant defense. There is a possibility that the enhanced NK cells cytotoxicity activity observed in the current screening could be partially explained by the presence of family of peptides in radish and mustard with a defense role.

Living organisms, ranging from microorganisms to vertebrates, invertebrates and plants, have evolved mechanisms to actively defend themselves against pathogens in their ecosystem. Vertebrates use highly developed adaptive immune system to deploy active antibodies and trained killer cells to recognize and eliminate specific attackers [

22]. In contrast, plants protect themselves through their innate immunity, a widespread defense strategy involving the production of antimicrobial peptides. While mammals, like humans, transfer antibodies through their breast milk to protect their offspring from disease early in life, plants transfer their protection against the pathogens and parasites to their seedlings through their DNA which can provide lifelong protection not only to immediate offspring but also to subsequent generations [

23]. It has been reported that the seeds of plants attacked by a pathogen were found to contain higher concentrations of chemical defense compounds that could provide augmented protection to the offspring. For example, when a tobacco plant,

Nicotiana tabacum, was exposed to tobacco mosaic virus, the plant’s progeny was found more resistant not only to the virus but also to some bacteria and molds [

24].

Defense related proteins, Defensin-like protein 192, kunitz trypsin inhibitor 1, Chitin-binding allergen Bra r 2, Pathogenesis-related thaumatin superfamily protein, have been identified in the top two leads (radish and mustard) of the current screening. Plant defensins are families of peptides that make up part of the innate immune system of plants directed against phytopathogens [

25]. They are structurally and functionally related to defensins that have been previously characterized in mammals and insects with molecular masses ranging between 5kDa and 7kDa [

26].

Most plant defensins are seed derived [

27]. For instance, it has been reported that, in radish, defensin protein (Raphanus sativus-antifungal protein, Rs-AFPs, 5-kD cysteine-rich proteins) represents 0.5% of the total protein in seeds functionally found to provide favorable microenvironment to the seedling at the time of germination by suppressing soil fungal growth [

28]. A similar anti-fungal peptide (AFP1) that shares 100% amino acid sequence identity with Raphanus sativus defensin (Rs-AFP1) has also been reported from the seed of B. juncea [

29].

Plant defensins have been found to have immunologic activities in inhibiting infection and inducing apoptosis in human pathogens. For example, induction of apoptosis and activation of caspases or caspase-like proteases in the human pathogen

Candida albicans has been observed from radish antifungal plant defensin RsAFP2 [

30]. Similarly, anti-breast cancer and leukemia cells proliferative activity, and immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase inhibitory activities by ground bean Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) have also been reported [

31].

The cross kingdom defensin biological effect was also investigated in transgenic plants that express the human defensin. Since human beta-defensins and plant defensins share structural homology, functional homology between these defensins of different kingdom were tested.

Arabidopsis thaliana plants expressing human beta-defensin-2 (hBD-2) were found more resistant against broad spectrum fungal pathogen

Botrytis cinerea and that the resistance was correlated with the level of active hBD-2 produced in these transgenic plants [

32].

Higher proportions of storage proteins than defense proteins were found in the top two leads, B. juncea and R. sativus. The seed storage proteins accounted for the bands at 12, 14, and 19-20 kDa, and the next group of kunitz trypsin inhibitor 1, uncharacterized protein Rs2_04757, and the hypothetical proteins likely accounted for the band at 22-24 kDa on the SDS-PAGE. Those were the four major bands in the fraction for radish (P00303). It’s likely that although cruciferin was predicted to be present in the seeds, it was denatured and precipitated during one of the extraction steps, as it is not very thermally stable.

B. juncea is not as well-characterized as R. sativus. The Brassicaceae taxonomy only contained 3,183 B. juncea genes, whereas it contained 115,890 R. sativus genes and 38,740 H. incana genes. So many of the genes that came up from the B. juncea query were from better-characterized species of Brassicaceae. Many of the genes did not have putative homologs in B. juncea, suggesting the possible that those genes could be not yet characterized in B. juncea. Many of the low abundance proteins were uncharacterized or hypothetical proteins, or domain-containing proteins of unknown or various functions. Many of the others were involved in such processes as vesicle trafficking and endocytosis, cytoskeleton remodeling, and protein degradation. It’s unlikely that the proteins with molecular weights of much greater than 30 kDa are actually present in the sample and may be results from a low fidelity peptide sequence, since this sample was ultrafiltered to exclude proteins greater than 30 kDa.

Collectively, data depicted here suggest that water extracts of Raphanus sativus or Brassica juncea could be considered for further characterization and immune functional exploration with a possibility of dietary supplemental use to bolster human recipients’ immune response. If clinically proven, the current report could expand the application of plant-based peptides as an additional safe and efficacious source of oral supplements with immune transfer activity in humans.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Selection

A total of 100 diverse plant aqueous extracts were selected based on their protein contents following a literature review. Plant parts such as root, stem, bark, fruit, seed, leaf, gum resin, aerial part, trunk bark, nut, leaf-stem, seed casing, cob, corn silk and whole plants were used for screening.

4.2. Preparation of Aqueous Extracts

Dried ground plant powder of each plant (20 g) were loaded into 100-ml stainless steel tubes and extracted twice with an organic solvent mixture (methylene chloride/methanol in a ratio of 1:1) using an ASE 300 automatic extractor at 80°C and 1500 psi pressure. The extract solution was automatically filtered and collected, then flushed the plant powder with fresh solvent and purged with nitrogen gas to dry before switching to aqueous extraction at 50°C. The aqueous solution was filtered and freeze-dried to provide aqueous extract (AE).

4.3. Biotage C18 fractionation

Plant aqueous extract (AE) was dissolved in 13 mL DI water and 2 mL DMSO (to improve the solubility). The solution was loaded onto pre-packed Biotage® Sfär C18 column (Duo 100 Å 30 µm, 60 g) and pushed into the column bed. Liquid dripping from the column was collected into waste beaker until solution just reached the frit. The column then was eluted with a gradient with methanol in water as follows: 100% DI water, 2 column volume (CV); 100% DI water to 50% methanol, 1.4 CV; 50% Methanol, 1.3 CV; 50% methanol to 100% methanol, 1.6 CV and 100% methanol, 2 CV. The elution was collected into test tubes and combined into 5 fractions: WA, WA-50ME, 50ME, 50-100ME, and 100ME. Solvents were evaporated with rotavap and the fractions were dried to yield column fractions.

4.4. Ultrafiltration

The selected reverse phase column fractions were ultrafiltered as follows. 250 mg column fraction dried sample was dissolved into 125 mL DI water. Each membrane disc was rinsed by floating its skin (glossy) side down in a beaker with DI water and sonicating for at least 1 hour, changing the water 3 times. The 30 kDa membrane disc was placed in ultrafiltration device with the skin (glossy) side up toward the solution. The solution from step 1 was transferred into the ultrafiltration device and nitrogen gas was applied to begin collecting <30 kDa fraction that passed through the membrane disk. Once completed, the membrane was removed and placed in a beaker with ~250 mL of DI water. It was sonicated for ~1 hour and the fraction was kept as the > 30 kDa fraction. The membrane in the ultrafiltration device was changed to 3 kDa and the <30 kDa fraction was transferred to filter through the new membrane. Once completed, the membrane was removed and placed in a beaker with ~250 mL of DI water. It was sonicated for ~1 hour and the fraction was kept as the 3-30 kDa fraction. The filtrate solution that passed through the 3 kDa membrane was labeled as the <3 kDa fraction. All the ultrafiltration fractions were freeze-dried to remove water and get powdered materials.

4.5. Bradford Assay

5 μL of standards and plant AE samples were added to 250 μL Bradford Reagent (Bio-Rad, 5000202). The assay was incubated for five minutes at room temperature before the absorbance was read at 595 nm. The protein concentration of the aqueous extracts was calculated using a Bovine Serum Albumin standard curve.

4.6. SDS-PAGE

Sample was denatured in SDS Sample Buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 10% β-mercaptoethanol) and boiled for 5 minutes. A 5-15% Tris-Tricine gradient gel was used for resolving the proteins. The gel was stained with Coomassie (45% methanol, 10% glacial acetic acid, 0.25% Coomassie G-250) for one-hour nutating at room temperature, and it was destained three times for 30 minutes each with 45% methanol, 10% glacial acetic acid. The gel was visualized on a ThermoFisher iBright gel and Western blot documentation station.

4.7. Protein Identification

emPAI was calculated according to previously reported methods [

33]. emPAI% was calculated to be the percent abundance of the specified protein in the sample. Molecular weight information and percent homology were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information at the National Institutes of Health. Briefly, for P00303, R. sativus, non-R. sativus proteins that were identified were checked for homology to R. sativus proteins using Protein BLAST. For P00397, B. juncea, non-B. juncea proteins that were identified were checked for homology to B. juncea proteins.

4.8. PBMC Cytotoxicity Assay

The PBMC cytotoxicity assay with image cytometry was adapted from the literature [

34]. Briefly, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs, Millipore Sigma, 0002145) were plated in 96-well cell culture plates at 250,000 cells/well. For screening, these cells were treated with 50 and 100 μg/mL extracts overnight in parallel with untreated cells. Cells treated with colostrum-based transfer factor at 500 μg/mL, and IL-2 at 20 μg/mL were used as references. The next day, one million human cancerous K562 lymphoblasts were resuspended in 2.5 mL cell culture media and 2.5 mL 10 μM Calcein-AM in a 15 mL conical, inverted to mix, and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The K562 cells were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for five minutes to pellet and resuspended in fresh media. They were pelleted and resuspended three times to wash out unbound Calcein-AM. K562 cells were added to PBMCs at a density of 10,000 cells/well (a 25:1 effector:target cell ratio). The 96-well plate was centrifuged at 600 rpm for two minutes to gently settle the suspended cells on the plate bottom. The plates were scanned for green, fluorescent Calcein-AM on an ImagExpress Pico by Molecular Devices every hour for four hours. The parameters were adjusted to detect single, bright green cells, and the number of live cells was calculated at each time point. The number of surviving K562 cells was normalized to the untreated control and the IL-2 control to reduce the variation among individual experiments.

5. Patents

Provisional patent has been filed with title PLANT-BASED COMPOSITION THAT MODULATE CELLULAR IMMUNITY by inventor Dr. DAVID VOLLMER.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MY, TH, QJ; Data curation, MY, TH, and QJ; Formal analysis, MY, TH, SC, and QJ.; Funding acquisition, QJ; Investigation, MY, TH, CS, AO, TT, PJ and MH; Methodology, MY, TH, CS, PJ and MH; Project administration, MY, and QJ; Resources, QJ; Supervision, MY, and QJ; Validation, MY, TH, CS, PJ, MH and QJ; Visualization, MY and QJ; Writing—original draft MY, TH, CS; Writing—review and editing, MY, CS, TH and QJ.

Funding

While the work was sponsored by 4Life, company had no role in study design, data, collection, data analyses, or data interpretation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No animal or human experiments were conducted in this report.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their utmost gratitude to Bill Lee, the owner of Econet/Unigen, Inc., who supported the fulfillment of project.

Conflicts of Interest

MY, CS, PJ, MH, TT and QJ are current Unigen employees, therefore they have competing financial interests.

References

- Hasselquist, D.; Nilsson, J.A. Maternal transfer of antibodies in vertebrates: Trans-generational effects on offspring immunity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009, 364, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, H.S. The transfer in humans of delayed skin sensitivity to streptococcal M substance and to tuberculin with disrupted leukocytes. J Clin Invest 1955, 34, 219e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, A.E.; Guaní-Guerra, E. Transfer Factor: Myths and Facts. Arch Med Res. 2020, 51, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, B.R. Does transfer factor act specifically or as an immunologic adjuvant? N Engl J Med 1973, 288, 908–909. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Rivero, E.; Vallejo-Castillo, L.; Vazquez-Leyva, S.; et al. Physicochemical Characteristics of TransferonTM Batches. Biomed Res Int 2016, 7935181, 1e8. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, H.S.; Borkowsky, W. A new basis for the immunoregulatory activities of transfer factor An arcane dialect in the language of cells. Cell Immunol 1983, 82, 102e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armides Franco-Molina, M.; Mendoza-Gamboa, E.; Castillo-Tello, P.; et al. In vitro antibacterial activity of bovine dialyzable leukocyte extract. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2006, 28, 471e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetvicka, V.; Fernandez-Botran, R. Non-specific immunostimulatory effects of transfer factor. Int Clin Pathol J. 2020, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ngou, B.P.M.; Ding, P.; Jones, J.D.G. Thirty years of resistance: Zig-zag through the plant immune system. Plant Cell. 2022, 34, 1447–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Shi, K. Plant peptides in plant defense responses. Plant Signal Behav. 2018, 13, e1475175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavormina, P.; de Coninck, B.; Nikonorova, N.; de Smet, I.; Cammue, B.P.A. The plant peptidome: An expanding repertoire of structural features and biological functions. Plant Cell. 2015, 27, 2095–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruyne, L.; Höfte, M.; De Vleesschauwer, D. Connecting growth and defense: The emerging roles of brassinosteroids and gibberellins in plant innate immunity. Mol Plant. 2014, 7, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, E.M.; Fathy, M.; Bekhit, A.A.; Abdel-Razik, A.H.; Jamal, A.; Nazzal, Y.; Shams, S.; Dandekar, T.; Naseem, M. Modulatory and Toxicological Perspectives on the Effects of the Small Molecule Kinetin. Molecules 2021, 26, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, M.; Cascone, P.; Madonna, V.; Di Lelio, I.; Esposito, F.; Avitabile, C.; Romanelli, A.; Guerrieri, E.; Vitiello, A.; Pennacchio, F.; Rao, R.; Corrado, G. Plant-to-plant communication triggered by systemin primes anti-herbivore resistance in tomato. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 15522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, M.L.; de Souza, C.M.; de Oliveira, K.B.S.; Dias, S.C.; Franco, O.L. The role of antimicrobial peptides in plant immunity. J Exp Bot. 2018, 69, 4997–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Cândido, E.; e Silva Cardoso, M.H.; Sousa, D.A.; Viana, J.C.; de Oliveira-Júnior, N.G.; Miranda, V.; Franco, O.L. The use of versatile plant antimicrobial peptides in agribusiness and human health. Peptides 2014, 55, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mott, G.A.; Middleton, M.A.; Desveaux, D.; Guttman, D.S. Peptides and small molecules of the plant-pathogen apoplastic arena. Front Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa Pelegrini, P.; Del Sarto, R.P.; Silva, O.N.; Franco, O.L.; Grossi-de-Sa, M.F. Antibacterial peptides from plants: What they are and how they probably work. Biochem Res Int. 2011, 2011, 250349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivier, E.; Artis, D.; Colonna, M.; Diefenbach, A.; Di Santo, J.P.; Eberl, G.; Koyasu, S.; Locksley, R.M.; McKenzie, A.N.J.; Mebius, R.E.; et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On. Cell 2018, 174, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, P.S.; Suck, G.; Nowakowska, P.; Ullrich, E.; Seifried, E.; Bader, P.; Tonn, T.; Seidl, C. Selection and expansion of natural killer cells for NK cell-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016, 65, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascal, V.; Schleinitz, N.; Brunet, C.; Ravet, S.; Bonnet, E.; Lafarge, X.; Touinssi, M.; Reviron, D.; Viallard, J.F.; Moreau, J.F.; Déchanet-Merville, J.; Blanco, P.; Harlé, J.R.; Sampol, J.; Vivier, E.; Dignat-George, F.; Paul, P. Comparative analysis of NK cell subset distribution in normal and lymphoproliferative disease of granular lymphocyte conditions. Eur J Immunol. 2004, 34, 2930–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselquist, D.; Nilsson, J.A. Maternal transfer of antibodies in vertebrates: Trans-generational effects on offspring immunity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009, 364, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, B. How plants and insects inherit immunity from their parents. Nature 2019, 575, S55–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathiria, P.; Sidler, C.; Golubov, A.; Kalischuk, M.; Kawchuk, L.M.; Kovalchuk, I. Tobacco mosaic virus infection results in an increase in recombination frequency and resistance to viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens in the progeny of infected tobacco plants. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stotz, H.U.; Thomson, J.G.; Wang, Y. Plant defensins: Defense, development and application. Plant Signal Behav. 2009, 4, 1010–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho Ade, O.; Gomes, V.M. Plant defensins--prospects for the biological functions and biotechnological properties. Peptides 2009, 30, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, F.T.; Anderson, M.A. Defensins--components of the innate immune system in plants. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005, 6, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terras, F.R.G.; Eggermont, K.; Kovaleva, V.; Raikhel, N.V.; Osborn, R.W.; Kester, A.; et al. Small cysteine-rich antifungal proteins from radish: Their role in host defense. Plant Cell. 1995, 7, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sagehashi, Y.; Oguro, Y.; Tochihara, T.; Oikawa, T.; Tanaka, H.; Kawata, M.; Takagi, M.; Yatou, O.; Takaku, H. Purification and cDNA cloning of a defensin in Brassica juncea, its functional expression in Escherichia coli, and assessment of its antifungal activity. J. Pestic. Sci. 2013, 38, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, A.M.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Lefevre, S.; Govaert, G.; François, I.; Madeo, F.; et al. The antifungal plant defensin RsAFP2 from radish induces apoptosis in a metacaspase independent way in Candida albicans. FEBS 2009, 15, 2513–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.H.; Ng, T.B. Sesquin, a potent defensin-like antimicrobial peptide from ground beans with inhibitory activities toward tumor cells and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Peptides 2005, 26, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, A.M.; Thevissen, K.; Bresseleers, S.M.; Sels, J.; Wouters, P.; Cammue, B.P.; François, I.E. Arabidopsis thaliana plants expressing human beta-defensin-2 are more resistant to fungal attack: Functional homology between plant and human defensins. Plant Cell Rep. 2007, 26, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihama, Y.; Oda, Y.; Tabata, T.; Sato, T.; Nagasu, T.; Rappsilber, J.; Mann, M. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005, 4, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somanchi, S.S.; McCulley, K.J.; Somanchi, A.; Chan, L.L.; Lee, D.A. A Novel Method for Assessment of Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity Using Image Cytometry. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).