Submitted:

08 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Collection Process

2.4. Critical Appraisal of the Included Articles

2.5. Quality Assessment

- 1)

- Did the study address a clearly focused research question?

- 2)

- Was the assignment of participants to interventions randomized?

- 3)

- Were all participants who entered the study accounted for at its conclusion?

- 4)

- Was blinding appropriately addressed for participants, assessors, and therapists?

- 5)

- Were the study groups similar at the start of the randomized controlled trial?

- 6)

- Apart from the experimental intervention, did each study group receive the same level of care (i.e., were they treated equally)?

- 7)

- Were the effects of intervention reported comprehensively?

- 8)

- Was the precision of the estimate of the intervention or treatment effect reported?

- 9)

- Did the benefits of the experimental intervention outweigh the harms and costs?

- 10)

- Could the results be applied to your local population/in your context?

- 11)

- Would the experimental intervention provide greater value to the people in your care than any of the existing interventions?

- 1)

- Did the study address a clearly focused issue?

- 2)

- Did the authors use an appropriate method to answer their question?

- 3)

- Were the cases recruited appropriately?

- 4)

- Were the controls selected appropriately?

- 5)

- Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias?

- 6)

- Aside from the experimental intervention, were the groups treated equally, and did the authors account for the potential confounding factors in the design and/or in their analysis?

- 7)

- How large was the treatment effect?

- 8)

- How precise was the estimate of the treatment effect?

- 9)

- Are the results credible?

- 10)

- Can the results be applied to the local population?

- 11)

- Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence?

3. Results

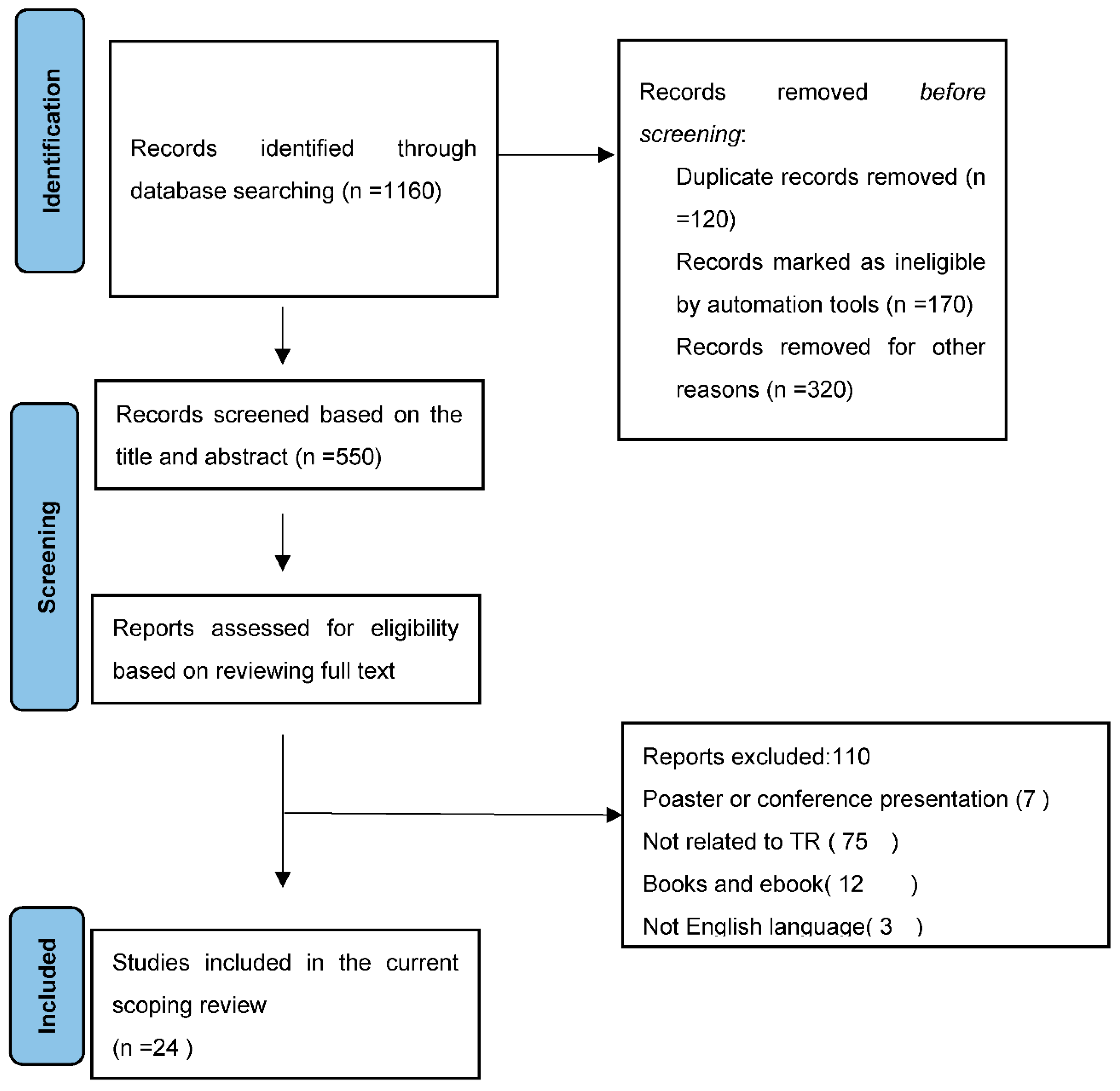

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Participant Characteristics

3.3. Frequently Used Outcome Measures

3.4. ICF, Disability, and Health Domain

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Vellata, C.; Belli, S.; Balsamo, F.; Giordano, A.; Colombo, R.; Maggioni, G. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation on motor impairments, non-motor symptoms and compliance in patients with Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 627999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Tang, K.; Li, X.; Hou, Z. Research hotspots and trends of brain-computer interface technology in stroke: A bibliometric study and visualization analysis. Front Neurol. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, X.; Lian, Z. Impact of wooden versus nonwooden interior designs on office workers’ cognitive performance. Percept Mot Skills. 2020, 127, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhostin Ansari, N. Bahramnezhad, F.; Anastasio, AT.; Hassanzadeh, G.; Shariat. A.; Telestroke: A Novel Approach for Post-Stroke Rehabilitation. MDPI. 2023. p. 1186.

- Laver, KE.; Adey-Wakeling, Z.; Crotty, M.; Lannin, NA.; George, S.; Sherrington, C. Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuteri, D.; Mantovani, E.; Tamburin, S.; Sandrini, G.; Corasaniti, MT.; Bagetta., G. Opioids in post-stroke pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 587050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veras, M.; Kairy, D.; Rogante, M.; Giacomozzi., C.; Saraiva., S. Scoping review of outcome measures used in telerehabilitation and virtual reality for post-stroke rehabilitation. J Telemed Telecare. 2017, 23, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kwong, JS.; Zhang, C.; Li., S.; Sun., F. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: A systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015, 8, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, DA. An examination of instrumental activities of daily living assessment in older adults and mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012, 34, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, C.; Mirela, I.; Sorin, M. Approaches on the relationship between competitive strategies and organizational performance through the Total Quality Management (TQM). Quality-Access to Success. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, D.; Kumar, S.; Brinkman, L.; Ferreira, IC.; Esquenazi, A.; Nguyen, T. Telerehabilitation Initiated Early in Post-Stroke Recovery: A Feasibility Study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2023, 37, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucki, G.; Cieza, A.; Ewert, T.; Kostanjsek, N.; Chatterji, TB. Application of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in clinical practice. Disabil Rehabil. 2002, 24, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, HA.; French, DP.; Brooks, JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Methods Med Health Sci. 2020, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, WW.; Tang, A.; Woo, B.; Goh, SY. Perception of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement of authors publishing reviews in nursing journals: A cross-sectional online survey. BMJ open. 2019, 9, e026271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Dexter, B.; Hancock, A.; Hoffman, N.; Kerschke, S.; Hux, K. Implementing Team-Based Post-Stroke Telerehabilitation: A Case Example. Int J Telerehabili. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, SC.; Dodakian, L.; Le, V.; McKenzie, A.; See, J.; Augsburger, R. A feasibility study of expanded home-based telerehabilitation after stroke. Front Neurol. 2021, 11, 611453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marianna, C.; Francesco, A.; Paolo, T.; Loris, P.; Tiziana, M.; Giuseppe, N. Stroke Telerehabilitation in Calabria: A Health Technology Assessment. Front Neurol. 2022.

- Uswatte, G.; Taub, E.; Lum, P.; Brennan, D.; Barman, J.; Bowman, MH. Tele-rehabilitation of upper-extremity hemiparesis after stroke: Proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial of in-home constraint-induced movement therapy. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2021, 39, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozevink, SG.; van der Sluis, CK.; Hijmans, JM. HoMEcare aRm rehabiLItatioN (MERLIN): Preliminary evidence of long term effects of telerehabilitation using an unactuated training device on upper limb function after stroke. J NeuroEng Rehabi. 2021, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C.; Zhang, B.; Chow, T.; Ye, F.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Z. Home-based self-help telerehabilitation of the upper limb assisted by an electromyography-driven wrist/hand exoneuromusculoskeleton after stroke. J NeuroEng Rehabi. 2021, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S-C.; Lin, C-H.; Su, S-W.; Chang, Y-T.; Lai, C-H. Feasibility and effect of interactive telerehabilitation on balance in individuals with chronic stroke: A pilot study. J NeuroEng Rehabi. 2021, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, PI.; Lara, O.; Lavado, A.; Rojas-Sepúlveda, I.; Delgado, C.; Bravo, E. Exergames and telerehabilitation on smartphones to improve balance in stroke patients. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saywell, NL.; Mudge, S.; Kayes, NM.; Stavric, V. Taylor D. A six-month telerehabilitation programme delivered via readily accessible technology is acceptable to people following stroke: A qualitative study. Physiother. 2023.

- Lee, SJ.; Lee, EC.; Kim, M.; Ko, S-H.; Huh, S.; Choi, W. Feasibility of dance therapy using telerehabilitation on trunk control and balance training in patients with stroke: A pilot study. Med. 2022, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro, C.; Urrútia, G.; Cabanas-Valdés, R. Telerehabilitation for balance rehabilitation in the subacute stage of stroke: A pilot controlled trial. Neurorehabil. 2022, 51, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, S.; Waris, A.; Gilani, SO.; Iqbal, J.; Shaikh, N.; Pujari, AN. Rehabilitation of upper limb motor impairment in stroke: A narrative review on the prevalence, risk factors, and economic statistics of stroke and state of the art therapies. Health. 2022: MDPI.

- Rossetti, G.; Cazabet, R. Community discovery in dynamic networks: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR). 2018, 51, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lach, J.; Lo, B.; Yang, G-Z. Toward pervasive gait analysis with wearable sensors: A systematic review. J Biomed Inform X 2016, 20, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, KA.; Kempen, GI.; Schwenk, M.; Yardley, L.; Beyer, N.; Todd, C. Validity and sensitivity to change of the falls efficacy scales international to assess fear of falling in older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Gerontol. 2011, 57, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, TJ.; Langhorne, P.; Stott, DJ. Barthel index for stroke trials: Development, properties, and application. Stroke. 2011, 42, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, RL.; Godbee, K.; Sigmundsdottir, L. A systematic review of assessment tools for adults used in traumatic brain injury research and their relationship to the ICF. Neurorehabilit. 2013, 32, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year – Country |

Design; Participant’s Age Group; Sex |

Type of Stroke; Phase Of Stroke Rehabilitation |

Type of VR Or TR Brief Description Of The System | CASP |

| Cramer; 2023 – USA | Randomized Clinical Trial; 124 Adult; M=90, F=34, age of 61 |

Stroke with arm motor deficits | TR: intensive arm motor therapy in the clinic (IC), or in the patient’s home using TR to deliver services via an internet-connected computer |

8/11 |

| Toh; 2023 – Hong Kong | Mixed-Methods Study; 11 Adult; M=4, F=7, age≥18 years | Limb telerehabilitation in persons with stroke |

TR: The wearable device, telerehabilitation application | 9/9 |

| Marianna, 2022 – Italy | Clinical Trail study 19 patients M=13F=6 Age: 61.1 ±8.3 years |

Post-stroke patients with a diagnosis of first-ever ischemic (n = 14) or hemorrhagic stroke (n = 5), |

TR: The entire TR intervention was performed (online and offline) using the Virtual Reality Rehabilitation System (VRRS) (Khymeia, Italy). |

9/9 |

| Allegue; 2022 – Canada | Mixed method Case Study; 5 Adult; M=3, F=2 Age: 41-89 |

Stroke Survivors | TR+VR:( VirTele): Virtual Reality Combined With Telerehabilitation |

9/9 |

| Salgueiro; 2022 - Spain | Prospective Controlled Trial; 49 Adult; M=31, F=18, Age: 55-82 | Subjects with a worsening of their stroke symptoms or any of the comorbidities (eg: another neurological disease or orthopaedic problem of the lower limbs) | TR: using AppG | 9/9 |

| Salgueiro; 2022 – Spain | Prospective, Single-Blinded, Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT); 30 Adult; M=20, F=10, being over 18 years of age |

Chronic Stroke Survivors | TR: The practice of specific lumbopelvic stability exercises, known as core-stability exercises (CSE). |

9/11 |

| Anderson; 2022 – USA | Case study design and experimental study , One participants F=1, 37 years old |

Stroke with the etiology was a subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm at the left middle cerebral artery bifurcation | TR: framework for telerehabilitation and the effects of team-based remote service delivery | 9/9 |

| So Jung Lee; 2022 – Republic Of Korea | Randomized Control Trial (RCT); 17 Adult eligible; 14 participants were finished M=10, F=4, Age: Exprimental group=9 Control group =8 |

patients with subacute or chronic stroke | TR: videoconferencing using Zoom | 8/11 |

| Dawson; 2022 – Canada | Pilot, Single-Blind (Assessor), Randomized Control Trial (RCT); 17 Adult; M=9, F=8, Age:42-75 |

Stroke survival with fluent in written and spoken English and have no severe aphasia | TR: A strategy training rehabilitation approach (tele-CO-OP) | 8/11 |

| Uswatte; 2021 - Birmingham | Randomized clinical trials design 24 Adults ≥1-year post- Age: 48-72 M=13, F=11 |

Upper-extremity hemiparesis after stroke |

TR: using a computer-generated random numbers table, to in-lab or tele-health delivery of CIMT | 8/11 |

| Samantha, 2021 | A randomized controlled. M=8 F=3 Age = 66.0 ± 8.4 |

Upper limb function after stroke. |

TR: Home care arm rehabilitation (MERLIN) is a combination of an unactuated training device using serious games and a telerehabilitation platform in the patient’s home situation. | 9/9 |

| Samantha, 2021 | A randomized controlled. M=8 F=4 Age = 64.8 ± 8.5 |

Upper limb function in chronic stroke. | TR: Home care arm rehabilitation (MERLIN): telerehabilitation using an unactuated device based on serious games improves the upper limb function in chronic stroke. | 8/9 |

| Shih-Ching, 2021 | prospective case-controlled pilot study 30 patients F=6 M=9 Age: 51-68 |

chronic stroke | TR: Three commercially available video games | 9/9 |

| Chingyi, 2021 | A single-group trial 11participants F=6 M=5 Age: 44-66 |

chronic stroke(hemorrhagic/ Ischemic) | TR: A home-based self-help telerehabilitation program assisted by the aforementioned EMG-driven WH-ENMS | 7/9 |

| Marin-Pard, 2021 | Case study and Clinical trail studyOne participantsages =67 years oldM=1 | Chronic stroke With upper extremity hemiparesis | TR: Tele-REINVENT system consists of a laptop computer with all necessary programs preloaded, configured, and displayed in an easy-to-use manner, a pair of EMG sensors with the enclosed acquisition board, and a package of disposable electrodes | 7/9 |

| Cramer; 2021 – USA | Prospective, Single-Group, Therapeutic Feasibility Trial ; 13 Adult; M=9, F=4, median age 61 | Home-Based Telerehabilitation After Stroke |

TR: Patients received 12 weeks of TR therapy, 6 days/week, with a live clinic assessment at the end of week 6 and week 12. Patients were free to call the lab with questions. |

9/9 |

| Kessler; 2021 – Canada | Multiple Baseline Single-Case Experimental Design (SCED); 8 Adult; M=6, F=2 Age: 50-83 |

Stroke survivors |

TR: telerehabilitation occupational performance coaching. |

9/9 |

| Saywell, 2020 | Randomized controlled trial ACTIV: n = 47; control: n = 48 N= 95 participants M=49 F=46 |

Participants had experienced a first-ever hemispheric stroke of hemorrhagic or ischemic origin and were discharged from inpatient, outpatient, or community physiotherapy services to live in their own home | TR: Augmented Community Telerehabilitation Intervention | 9/11 |

| Burgos; 2020 , Chile | Clinincal study 6 participants M=3 F=3 |

Chronic stage: in early subacute stroke (seven weeks of progress). | TR: low-cost telemedicine(Therapist monitoring was done by connecting to the web platform and watching games scores daily at the scheduled session time or afterwards based on therapist availability) | 9/9 |

| Ora; 2020 – Norway | Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial; 30 Adult; M=19, F=11 Age> 18 |

Post-stroke with aphasia | TR: using a portable Fujitsu PC (laptop) with necessary software and material. |

9/11 |

| Huzmeli; 2017 - Turkey | Clinical trials study, 10 Adult; M=6, F=4, Age:45-60 |

Patients with Stroke who were hemiplegic and had sufficient equipment | TR: video communication(, TR was applied by contacting the patients via laptops with a camera and microphone and an internet connection) | 9/9 |

| Ivanova; 2017 – Germany | Clinical Trail study6 participants Age: 51-89 years M=4 F=1 |

Motor Relearning after Stroke (Five patients were in the subacute phase; one patient was considered chronic. All participants showed deficits in the motor activity of the shoulder, arm and hand function) | TR: Haptic Devices for Stroke Rehabilitation and Robot-based telerehabilitation system. | 9/9 |

| Dodakian; 2017 – USA | Clinical tails study 12Adult; M=6, F=6 Age:26-75 |

Patients with chronic hemiparetic stroke | TR: Individualized exercises and games, stroke education. |

9/9 |

| Özgün; 2017– Turkey | A Pilot Study, Study 10Adult; M=6, F=4 Age=44-61 |

Patients with Stroke | TR: giving rehabilitation services with computer-based technologies and communication tool. | 8/9 |

| Study (First Author, Year) | Standardized Outcome | Instrument | Reported Findings | ICF Domain | Focus of the Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cramer; 2023 – USA | Upper and lower limb function | Fugel-meyer motor assessment | The findings of this study suggest that telerehabilitation has the potential to substantially increase access to rehabilitation therapy on a large scale. |

b730 | Suboptimal rehabilitation therapy doses |

| Toh; 2023 – Hong Kong | Usability of the wristwatch | the System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire | The results demonstrated that the usability of the proposed wristwatch and telerehabilitation system was rated highly by the participants |

S730 | Upper limb |

| Marianna, 2022 – Italy | Motor recovery | Barthel Index (BI);Fugl-Meyer motor score (FM) and Motricity Index (MI) |

The results demonstrate the TR tool promotes motor and functional recovery in post-stroke patients. |

b730 | Upper limb |

| Allegue; 2022 – Canada | Improvement of UE motor function |

Berg Balance Assessment: Functional Gait Assessment: Activity-specific Balance Confidence Scale ndependently performs |

The results show most survivors of stroke found the technology easy to use and useful. | b730 | Arm feasibility |

| Salgueiro; 2022 – Spain | Balance in sitting position | The Spanish-version of the Trunk Impairment Scale 2.0 (S-TIS 2.0),Function in Sitting Test (S-FIST), Berg Balance Scale (BBS), Spanish-version of Postural Assessment for Stroke Patients (S-PASS), Brunel Balance Assessment (BBA)Gait assessment |

The results show greater improvement in balance in both sitting and standing position. |

b730 | Feasibility of core stability exercises |

| Salgueiro; 2022 – Spain | Balance and gait | Spanish-Trunk Impairment Scale (S-TIS 2.0) Sitting Test Spanish-Postural Assessment Scale |

The results show improvement trunk function and sitting balance. |

b730 | Trunk control, balance, and gait |

| So Jung Lee; 2022 – Republic Of Korea | Trunk control and balance function the functional movement and locomotion necessary for sitting, standing, and walking dependent walker ADLs Health-related QoL |

the Trunk Impairment Scale (TIS) scores the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, Functional Ambulation Categories (FAC), Korean Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI) scores EuroQoL 5 Dimension (EQ-5D) tool. |

The results show significant improvement in the TIS scores. | b730 | Subacute or chronic stroke |

| Dawson; 2022 – Canada | Self-identified in everyday life activities and mood | the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) The PHQ-9 |

The results show high satisfaction and engagement. | b730 | Improvements in social participation |

| Uswatte; 2021 - Birmingham | The outcome is the motor capacity | built-in sensors and video cameras Participant Opinion Survey (POS)1 the Motor Activity Log (MAL) The Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT) |

The results show large improvements in everyday use of the more-affected arm. |

S730 | The focus is on Upper-extremity hemiparesis |

| Samantha, 2021 | Improvement of the upper limb motor ability quality of life, user satisfaction and motivation. |

Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT), arm function tests, The EuroQoL-5D-5L (EQ-5D) The Intrinsic Motiva- tion Inventory (IMI), System Usability Scale (SUS) and Dutch-Quebec User |

The WMFT, ARAT, and EQ-5D did not show significant differences 6 months after the training period when compared to directly after training. However, the FMA-UE results were significantly better at 6 months than at baseline. | S730 | Upper limb |

| Samantha, 2021 | Limb motor ability Quality of life |

Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT), Action Research Arm Test (ARAT), Assessment-Upper Extremity (FMA-UE), EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D). |

The results show progress in monitored game settings, user satisfaction and motivation. | S730 | Upper limb |

| Shih-Ching, 2021 | functional mobility, balance, and fall risk, the degree of perceived efficacy, classifying the strength in each of three lower extremity muscle actions (hip f , Gait |

Berg Balance Scale (BBS) scores. the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, Modifed Falls Efcacy Scale, Motricity Index, Functional Ambulation Category |

The results show improvement in balance. | b730 | Balance |

| Chingyi, 2021 | the upper limb assessment, the upper limb voluntary function, the functional ability and motion speed of the upper limb, the basic quality of participant’s ADLs, spasticity |

The Fugl–Meyer Assessment (FMA),Action Research Arm Test (ARAT), Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT), Motor Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Modifed Ashworth Scale (MAS |

The results show improvements in the entire upper limb. | S730 | Upper limb |

| Marin-Pard, 2021 | EMG Signal Processing | Biofeedback, modular electromyography (EMG) |

The results show development of a muscle-computer interface. | S730 | Upper limb Function |

| Cramer; 2021 – USA | Upper and lower lime function | Fugel-meyer motor assessment | The results show assessments spanning numerous dimensions of stroke outcomes were successfully implemented. |

b730 | Limb weakness |

| Kessler; 2021 – Canada | Satisfaction of using telerehabilitation the Client Satisfaction Scale (CSS) |

the Client Satisfaction Scale (CSS) the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) |

The results show high satisfaction and a strong therapeutic relationship. | b730 | Occupational performance coaching |

| Saywell, 2020 | physical function , Hand grip strength and Balance , Self-efficacy. , Health outcomes |

The physical subcomponent of the Stroke Impact Scale), A JAMAR hand-held dyna-mometer, The Stroke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SSEQ) , The overall stroke recovery rating of the SIS3.0 |

The findings of this trial showed that rehabilitation augmented using readily accessible technology. |

b730 | Physical function |

| Burgos; 2020 , Chile | Balance and functional independence user experience | BBS and Mini-BESTest (MBT) , The Barthel Index (BI), The System Usability Scale (SUS) |

The results demonstrate that a complementary low-cost telemedicine approach is feasible, and that it can significantly improve the balance of stroke patients. |

b730 | Dosage and overall treatment |

| Ora; 2020 – Norway | Feasibility and acceptability of speech and language therapy | The videoconference software called Cisco Jabber/Acano | The results show tolerable technical fault rates with high satisfaction among patients. | b730 | Post-stroke aphasia |

| Ivanova; 2017 – Germany | Motor relearning collection of instant feedback visualizations, incorporating Telerehabilitation, Arm motor gains , Depression , Pain, Speed |

collection of instant feedback visualizations , | The results show tele system for stroke rehabilitation using haptic therapeutic devices is currently being implemented into full functionality. | b730 | Stroke patients in recovering voluntary motor movement capability |

| Dodakian; 2017 – USA | incorporating telerehabilitation , arm motor gains , Depression Pain , Speed |

vital signs, magnetic resonance imaging, FM Scale, Box and Blocks (B&B), NIHSS, Barthel Index, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) question form, Mini- Status Exam (MMSE), Optimization in Primary and Secondary Control Scale (adapted from Mackay et al20), The Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, Mental Adjustment to Stroke Scale (Fighting Spirit subscore), Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale, Modified functional reach forward displacement (cm) Shoulder pain Gait velocity stroke self-efficacy questionnaire |

The results support the feasibility and utility of a home-based system to effectively deliver telerehabilitation. | b730 | Hemiparetic stroke |

| Özgün; 2017– Turkey | cognitive levels balance quality of life |

the Mini Mental State Examination, the Berg Balance Scale, the Short Form- 36 (SF-36) Quality of Life Scale |

The results show the improvement of using TR programs. | b730 | TR in patients with hemiplegia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).