1. Introduction

The advancement of highly automated vehicles holds a critical position in the field of automotive engineering. Key advantages of highly automated driving include improving road safety, particularly by minimizing driver errors and making efficient use of commuters’ travel time [

1,

2]. Perception, trajectory planning and control are three main parts in the structure of automated vehicles, where the control part allows the car to follow the trajectory, which has been determined in the trajectory planning parts. Because of the complex interconnections between the vehicle’s lateral and longitudinal dynamics, designing a controller needs to be considered carefully [

3] and it continues to remain a challenge. There are various control techniques that have been used for trajectory tracking in automated vehicles, such as: PID [

4,

5], Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) [

6,

7,

8,

9], Sliding Mode Control (SMC) [

10,

11], Robust Control [

12], Model Predictive Control (MPC) [

8,

9,

12,

13,

14,

15] and Reinforcement Learning [

16,

17]. However, most of them are used to control longitudinal and lateral dynamics separately. Recently, controlling both longitudinal and lateral dynamics has been applied. Nada et al. [

18] designed a multi-input–multioutput (MIMO) linear MPC with some constraints in the vehicle dynamics, in which the reference path is tracked based on the steering angle and angular velocity. In [

4], Zhou et.al adopted the MPC and Nonliner Model Predictive Control (NMPC) method to cope with the nonlinear MIMO problem for the vehicle’s lateral stability. Although MPC controller can use for nonlinear dynamics to solve with constraints, MPC prevents conducting an experiment on a real-time system because of the increasing of model complexity and constraints as well as the huge amount of computation. SMC technique is proposed to control by combining lateral and longitudinal dynamic [

19]. However, when applying SMC technique the chattering phenomenon often appears when acquiring robustness. To overcome this obstacle, in [

20] the authors applied a new sliding mode that reduces chattering and makes state variables converge faster. However, rough road surfaces can lead to compromised path tracking accuracy and overall system stability.

LQR approach is used popularly in automated vehicle controllers because of algorithmic simplicity, high-precision performance and satisfaction with dynamic constraints. Zhang [

21] compared the robust controller with LQR and MPC in terms of performance as well as computation. In the parking scenario, the LQR controller has better performance. Regarding computation, LQR requires less in comparison with MPC while it has the same performance indicators in some cases. However, LQR methods usually do not consider disturbances which can contribute to system errors. To cope with this problem, Kapania et al. [

22] designed a controller by combining feedback and feedforward steering. The aim is to keep the stability of the vehicle under hard maneuvering conditions as well as minimize path deviation. However, the steady-state path deviation drastically increases at high velocity. In [

23] the authors aslo proposed a LQR controller using feedforward and predictive steering for lateral dynamic, which helps vehicle driving in complex conditions. Although LQR controllers have been widely applied to automated vehicles, most of LQR choose weight factors based on empirical consideration. To get rid of empiricism, some studies added algorithms to optimize LQR controller in order to improve performance. In [

24,

25,

26] the authors used GA, fuzzy control and PSO to choose the optimize weight factors for LQR controller. The results show the effectiveness of these algorithms regarding tracking accuracy and stability of vehicle. Although promising results are shown in these studies, there is still potential for further improvement in the accuracy of the controller.

On the other hand, because the requirement for automated vehicles level is higher, the scenarios for testing become complex. Consequently, novel challenges to the reliability of automated vehicles emerge in testing and validation. Additionally, the growing need for testing and validation in terms of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) as well as Automated Driving technologies arises because real-world road scenarios have covered more and more [

27,

28]. Consequently, X-in-the-Loop (XiL) has emerged and become a predominant approach for scenario-driven simulation testing of automated vehicles. The "X" expressed the various development focuses: model, software, processor, hardware, vehicle, and driver. Hye Young An [

29] proposed a path planning algorithm and Pure Pursuit in real-time to control vehicle by considering detected lanes and some constraints. The authors considered only a single lane and the error is approximately 1.147m when the car exits the roundabout. Taekgyu Lee el at. [

30] employed a DNN-based controller to control the car. This method reduces the computational load in comparison with the previous NMPC method. In [

31,

32], the authors also used MPC and NMPC to control automated vehicles in real-time system, the results show the efficiency, robustness as well as feasibility of these methods. In [

33] the authors used a low-level MPC to control the small-scale race cars. Based on the simulation and experimental findings, it appears that opting for a more cautious approximation with the discriminating kernel leads to a safer driving style. Most of the previous works did not compare the gap between office simulation and real-time system. This happened because of the differences in purpose, complexity, resources, and constraints.

The key contributions of this study are:

Three optimization algorithms, namely Artificial Bee Colony, Particle Swarm Optimization, and Genetic Algorithm are implemented to find the best coefficient of the LQR controller. The primary objective is to eliminate the external disturbances arising from the desired trajectory. The algorithm optimizations is simulated on CarMaker and Matlab/Simulink software. The effectiveness of three algorithmic enhancements is compared to LQR controller performance without using them. Afterward, the results obtained from three algorithm optimizations are compared together to choose the best algorithm for the Model-in-the-Loop (MiL) simulation.

The best algorithm for MiL simulation is used to simulate on a real-time system to assess performance. The chosen algorithm is simulated on MiL and Hardware-in-the-Loop (HiL). The outcomes reveal the gap between the MiL simulation and HiL for the vehicle model under consideration.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows:

Section 2 contains the vehicle dynamic of the model, the framework of Apollo as well as the optimization. In

Section 3, the model and controllers are simulated on an office environment and real-time system using the multibody software CarMarker.

Section 4 discusses about results and the

Section 5 summarizes the research.

2. Vehicle Dynamics and Control

Apollo is a widely recognized open-source SAE Level 4 AD platform that was introduced by Baidu company [

34]. It includes a comprehensive suite of hardware and software solutions for various aspects of AD, including perception, planning, and control.

2.1. Vehicle Model

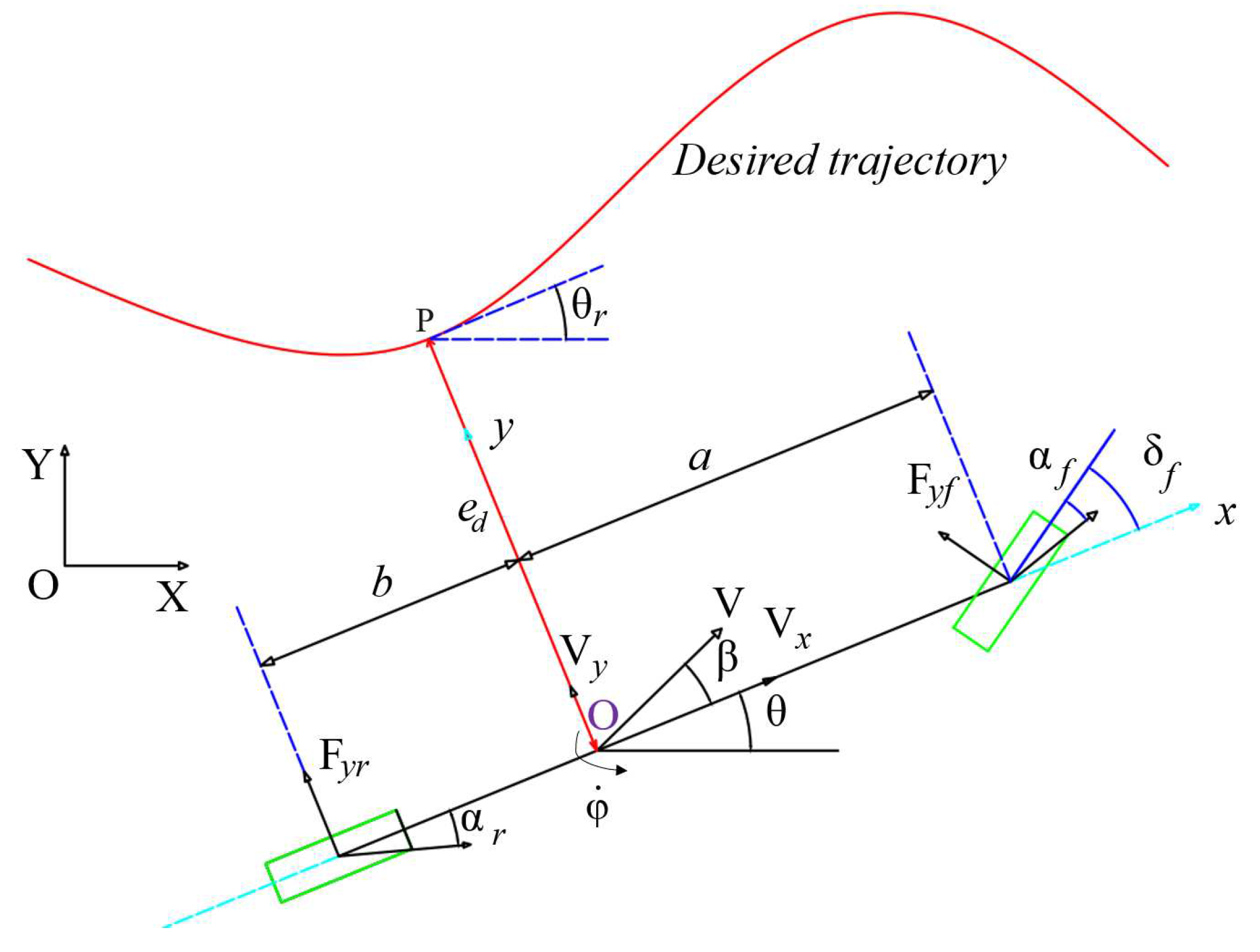

Figure 1 depicts the vehicle dynamic model as:

In this model, we assume that the model is simplified as the lateral dynamic model with two degrees of freedom, vertical movement is ignored since the vehicle drives in a single plane. , are steering angles in the front and rear wheels, respectively. The front and rear steering angle are small and noted by and , so the lateral force and side slip angle has a linear relationship, which is acceptable for tire slip angles about 3 degree. The lateral load transfer effects which occur due to lateral acceleration is neglected and the suspension system’s effect is not considered.

O is mass center point, a and b are the distances from O to the front and rear axles, is the yaw angle, is yaw rate. and are the lateral stiffness of the tires in the front and rear wheels, is the lateral force of the front wheel and is the lateral force of the rear wheel. , are vehicle’s longitudinal and lateral velocity, respectively.

The dynamic equations of this model are noted as [

35]:

where

m is the mass of vehicle,

is the rotation inertia of vehicle around vertical axis.

Because the front wheel steering angle is small, so the lateral force and side slip angle has a linear relationship, the dynamic equations (

1) (

2) is obtained as follows:

When vehicle follows a reference path, lateral error and heading angle error will occur. Illustrated in

Figure 1, the lateral error, denoted as

represents the shortest distance between the point

O and projected point

P on the reference path. Meanwhile, the heading angle error, referred to as

is the difference between the actual heading angle of the vehicle

and the reference heading angle

. For the sake of simplicity, the side slip angle is assumed

= 0 at the point

O, and the heading angle error is calculated as

=

-

. In practical control, the controller’s task is to promptly eliminate these two errors in real-time to ensure the vehicle stays on track with the planned path. With these errors in mind, it becomes possible to compute the first-order derivatives of the lateral error

and the heading angle error

:

The Equations (

5) and (

6) are substituted in Equation (

4), can be obtained:

The equations (

7) to (

8) can be rewritten as:

Equation (

9) can be rewritten in the state - space representations as:

with: X = [

] is the state vector; U = [

] is the control input.

2.2. Lateral Controller

In this study, the path planning process involves a series of reference points. This discretization of data is necessary for practical implementation. To control the vehicle along this discrete trajectory, a discrete Linear-Quadratic Regulator (dLQR) controller is used. The Equation (

10) is discretized to design dLQR controller, which governs the vehicle’s dynamics. During this process, we neglect the effect of

and apply the midpoint Euler and the forward Euler approach to clarify the model while preserving essential characteristics. As a result, we obtain the equation that describes the discrete tracking errors as:

with:

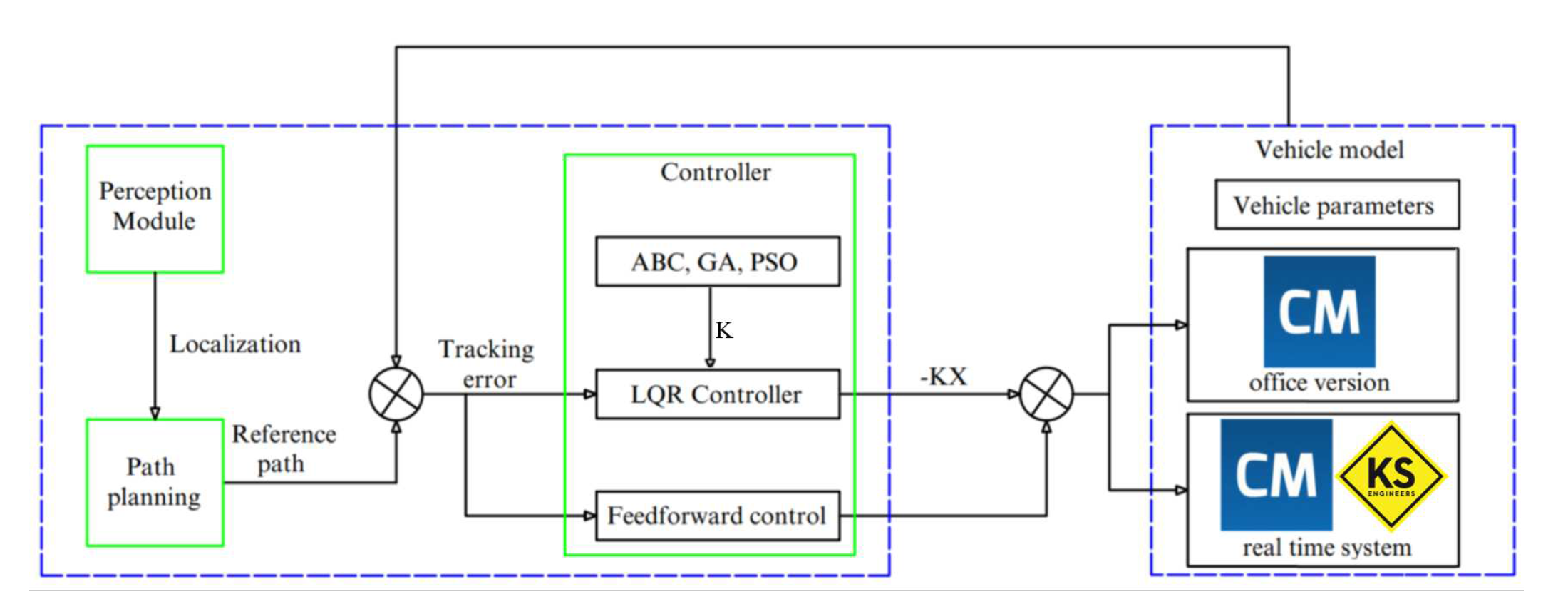

Figure 2 shows the entire structure of the LQR controller for an automated vehicle, which includes four main parts: perception, path planning, controller and vehicle model. In path planning, the EM planner [

36] is used to generate reference path and path tracking errors. As the path planning module is not the focus of our work, the exact algorithm can be referenced in the GitHub project [

37].

The LQR controller is the main center of the second part. In this study, we use three algorithm optimizations (ABC, GA, PSO) to find the optimized matrix K for the LQR controller as well as calculate in the Feedforward control step. Then, the steering angle is sent to the vehicle model to control a car. We use the BMW5 car model and IPG Carmaker software as a simulation environment. After comparing the K value from three optimization algorithms, we find the best algorithm for the car. Finally, we use this algorithm to simulate on the real-time system and compare the gap results between the MiL and HiL.

The cost function of LQR controller is defined as:

Where Q weighting matrices of the state error and R is weighting matrices of the control signal.

,

are the weight factors of lateral error, lateral error rate, heading error, heading error rate and the steering angle in the front wheel, respectively. Substituting equation (

11) into (

13), the Lagrange multiplier approach is employed to build the constraints as follows:

The Hamiltonian function is defined as:

From equation (

17) and (

16) obtain:

The extreme value of equation (

18) is achieved:

where

is solved by Riccati equation: P = Q + -

Equation (

19) can be rewritten as:

where K =

is the gain of the LQR controller. Substituting equation (

20) into equation (

10) obtains:

According to equation (

21), irrespective of the specific value assigned to the gain K, the distance error and heading error of an automated vehicle can not be zero during the control process, indicating the presence of a steady-state error in the system. Consequently, the influence of C

is removed and use feedforward control

follow as:

Substitute equation (

22) into (

10), so that when

=0, the formula for the state variable without steady-state error is as follows:

By solving and simplifying equation (

23), the following is obtained:

Following the Equation (

24), when

= 0, the feedforward control is:

In Equation (

6), we assume that the real heading error can be calculated as

. Reducing the heading error to zero, as well as ensuring that

is crucial when the vehicle reaches a stable state. Consequently, there is no need to devise a feedforward controller for eliminating the steady-state error in

. Additionally, Kapania et al. [

22] demonstrated that achieving steady-state equilibrium is still possible even when there are non-zero values for lateral error as well as heading angle error.

2.3. Calibration Optimization

Matrix K is the gain of the LQR controller and can be calculated from equation (

19). The key to the LQR controller lies in the choose of the weight factors of matrices Q and R in equation (

14), (

15). In the previous study [

38], Li el at. chose these weight factors based on the empirical method. First, Q is optimized by setting to R an intermediate value (arbitrarily chosen to be in the order of

) and Q is considered diagonal to simply tuning. Q is tested for a small value

(close to 0) and later for a large value

(in the order of

). The two results are compared, then an intermediate value

is tested and the process is repeated by considering as new “small” and “large” limits

and the value between

and

that yielded the best result. The process is then repeated by choosing a new intermediate value between the two limits until an acceptable result is produced. For R optimization the same approach is followed setting Q to the optimized value just found.

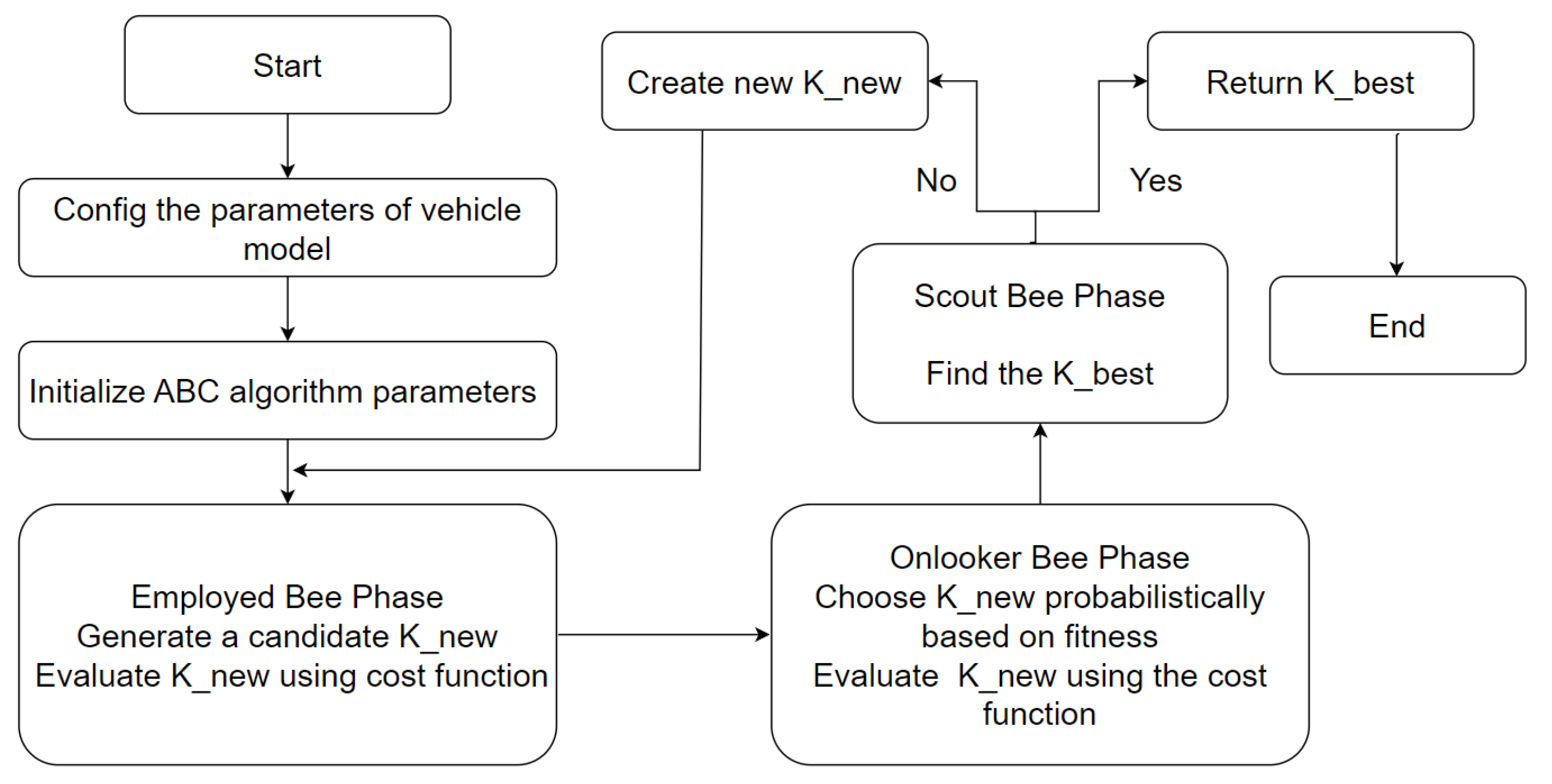

The flowchart of the ABC algorithm and LQR controller is shown in

Figure 3. The employed bees actively seek K values in the vicinity of their remembered food source, all the while communicating information about these K values to the onlooker bees. The onlooker bees are likely to select good K values from those based on the fitness function and also evaluate K values using the cost function. A few employed bees translate into the scout bees and search for new food sources until satisfy the condition.

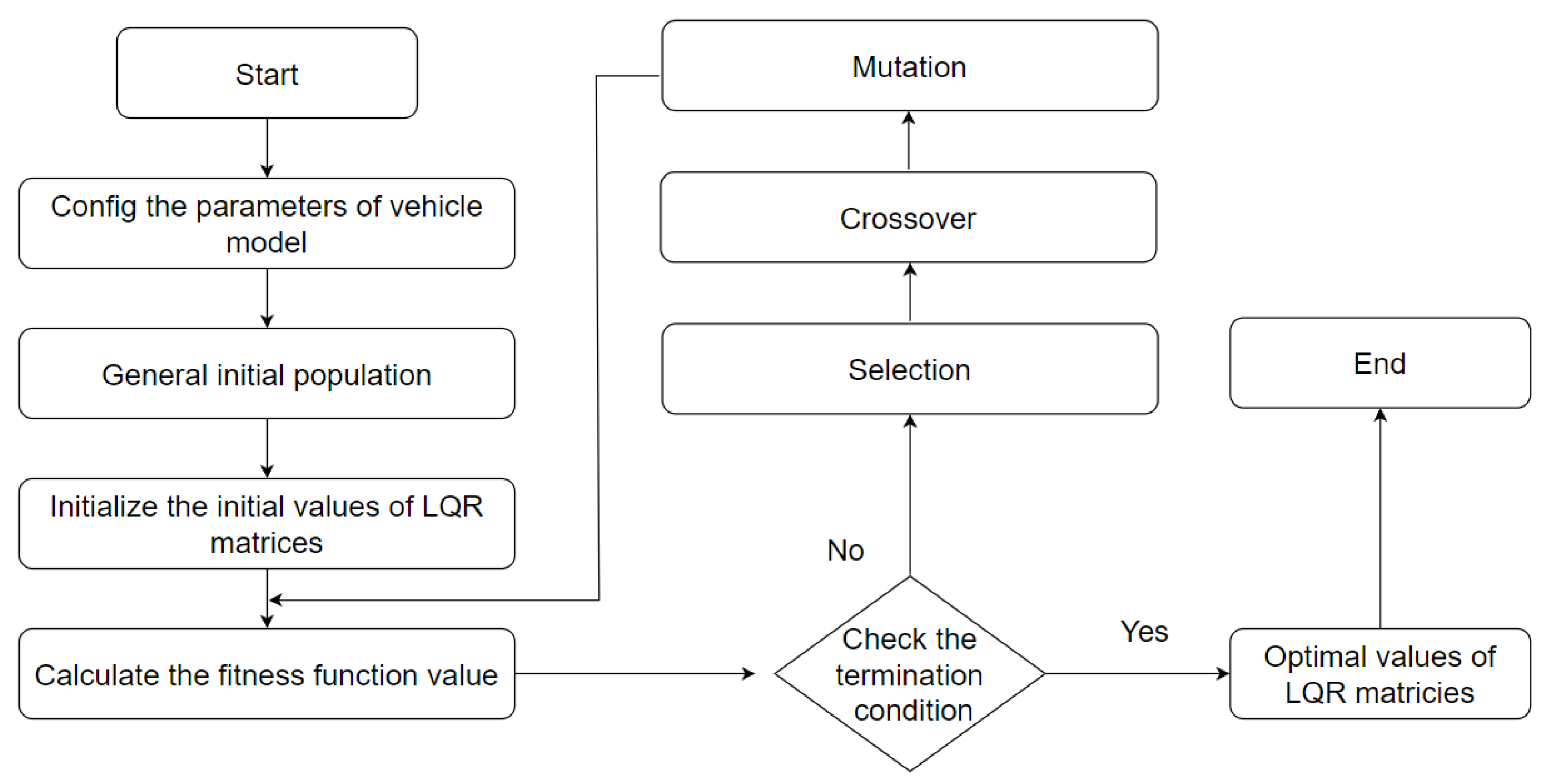

The GA drawing inspiration from biological principles such as mutation, crossover, and selection. The GA commences with config the parameters of BMW car, initial K values as well as randomly generate individuals, initiating the evolutionary journey. In each generation, the fitness of every individual is evaluated, typically by assessing the value of the fitness function. Stochastic selection is employed to favor more fit individuals from the current population. These selected individuals’ genomes are then subject to modifications, such as recombination and possibly random mutations, to generate a new generation of candidate solutions. This cyclic process continues, with the newly formed generation becoming the basis for the subsequent iteration. The GA advances through iterations until it reaches a termination condition. The flowchart of GA-LQR is shown in

Figure 4.

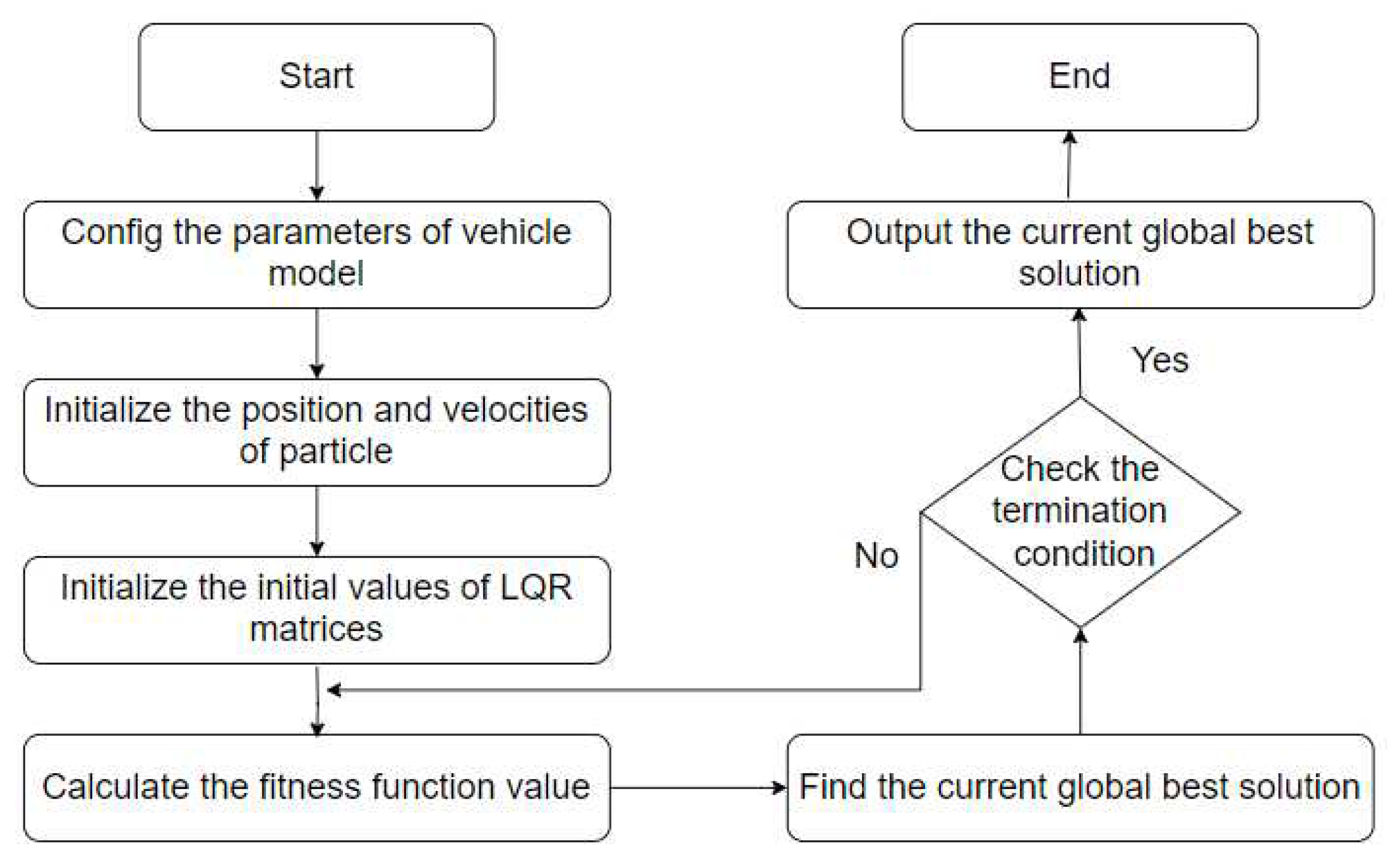

Figure 5 illustrates the flowchart of PSO algorithm and LQR controller. The optimal weight factor is found by searching on the global in order to enhance the LQR controller performance. Firstly, the parameters of BMW car model are configured. Then, we set the initial particles’s position and velocities as well as the initial values of LQR matrices. After that, the algorithm will calculate the fitness function value and find the global best solution. If the condition is satisfied, the algorithm is stopped, otherwise, the algorithm continues to run until satisfies the condition.

3. Simulation and Results

3.1. Model-in-the-Loop Simulation

In this study, a BMW5 model is used for simulation. The model was calibrated with experiments done in the Institute of Automotive Engineering laboratory and on a proving ground. Firstly, test the BMW 5 car on the real road to measure parameters and save it into the datasheet. Then, a simple model with parameters adjustment from the datasheet is created. After that, the car was simulated on the test road, compared the parameters were measured with the simulation. Finally, calibrate the steering model and stabilizer model for good fitting of the curves and choose the best tire model.The results of the model calibration refer to [

39]. The BMW5 model is simulated in the CarMaker environment on a 50-meter circular road, as depicted in

Figure 6. Lateral position error was evaluated during a total driving duration of 48 seconds, with a maximum speed is 50km/h.

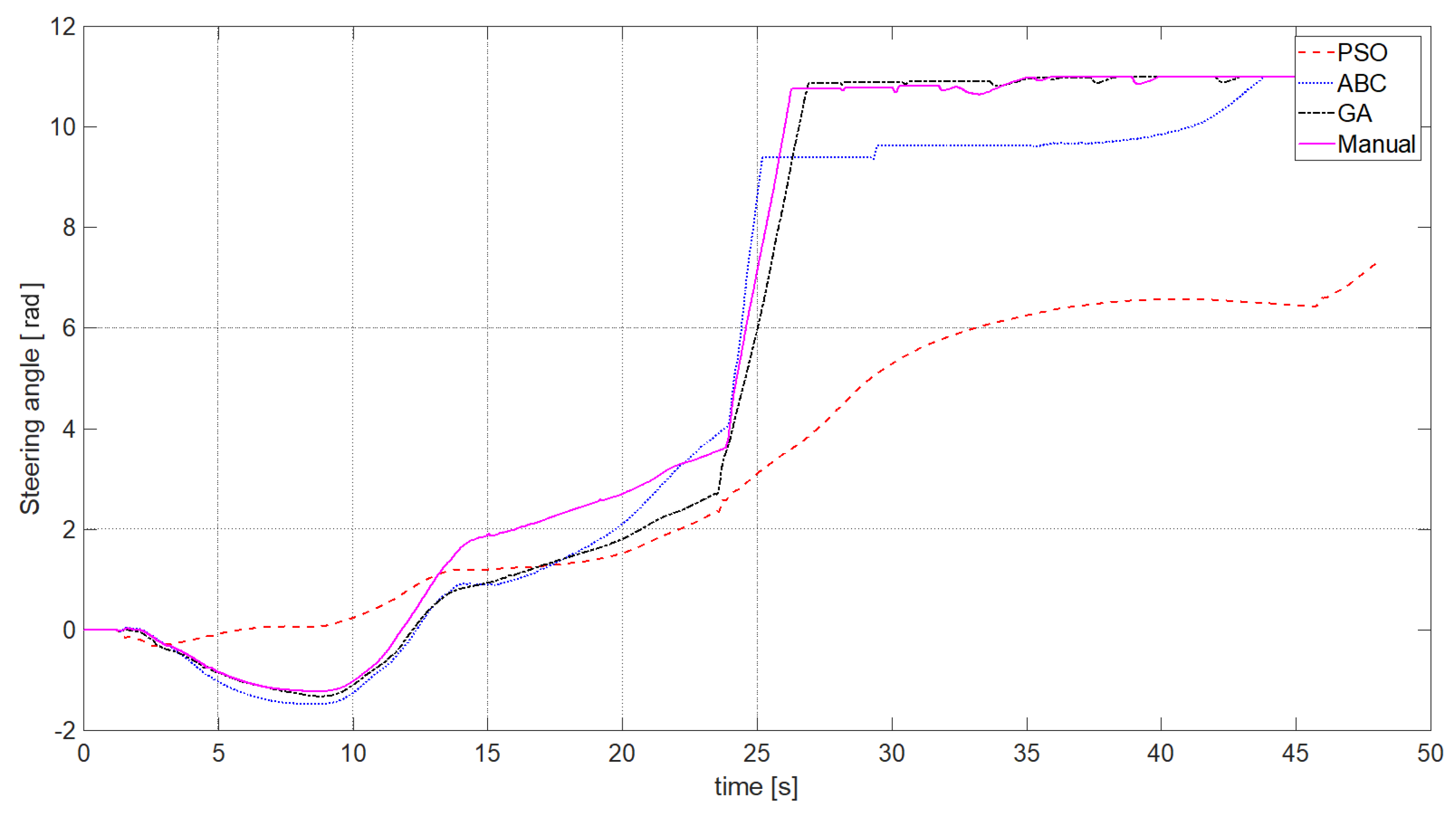

Figure 7 illustrates the vehicle’s steering angle under four control schemes: the manual LQR controller, the PSO based on LQR (PSO-LQR) controller, the ABC based on LQR (ABC-LQR) and GA based on LQR controller (GA-LQR).

Table 1.

Lateral error comparison between optimization algorithms.

Table 1.

Lateral error comparison between optimization algorithms.

| Compare |

Manual |

ABC |

GA |

PSO |

| Absolute max values dL |

1.2026 |

2.6069 |

1.5611 |

0.0576 |

| Absolute mean values dL |

0.0249 |

0.0242 |

0.0207 |

0.0061 |

| Absolute max values L |

3.5481 |

4.4860 |

3.5151 |

0.7532 |

| Absolute mean values L |

0.5854 |

0.7696 |

0.5549 |

0.1582 |

3.2. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation

In the previous works, Li et al. [

27,

28,

40] the co-simulation framework for Virtual Vehicle Test Bench is introduced. CarMaker and Matlab/Simulink are used together to build a co-simulation software system. The Multi-Body Simulation (MBS) environment is provided by CarMaker software, including vehicle dynamics, sensor models as well as virtual environment. The CarMaker is implemented on a real-time processing unit called "Xpack4". Both CarMaker and Xpack 4 are from IPG Automotive GmbH [

41]. Moreover, the whole vehicle test bench is controlled by the automation-system software Tornado from KS Engineers [

42]. The users has capacity to configure Virtual Vehicle Test Bench using Tornado. In adddition, ADAC (5 kHz) from KS Engineers [

42], which is real-time testing, controlling and monitoring system which developed for the Virtual Vehicle Test Bench in real-time. EtherCAT topology protocol enables real-time synchronous simulation communication between Tornado, ADAC and XPack4 real-time systems. In this study, the same framework is used, which comprises a virtual environment and a Virtual Vehicle Test Bench. This framework (RT-ADF) allows multiple software are integrated and executed on real-time hardware platforms. This work demonstrates an offline Virtual Vehicle Test Bench. If the simulation model is successfully executed and validated offline, it can be transferred to the real test bench. Therefore, this is a good approach to improve efficiency and optimize the work.

Table 2 depicts the results of the vehicle model in a real-time system.

In [

43], a quantitative comparison method is the Relative Error Criterion (REC) is used to validate results as:

We use the calculate the maximum absolute value of the error as:

4. Discussion

Figure 7 shows the steering angle of the vehicle in four cases using manual calibration, ABC, GA and PSO algorithms. In the interval spanning from the 4th to the 10th second, alterations in the steering angle were observed for the Manual calibration, GA, and ABC algorithms, registering an approximate variation of 1.9 rad. Conversely, the steering angle adjustment remained negligible when employing the PSO algorithm. Moreover, at the 24th second, a sudden soar in the steering angle occurred within a span of 3 seconds, for the Manual calibration, GA, and ABC algorithms. This value then stabilized thereafter at approximately 11 rad. In contrast, the steering angle change generated by the PSO algorithm exhibited a gradual increment, culminating at 8 rad by the conclusion of the aforementioned timeframe. Therefore, PSO algorithms can prevent the centrifugal acceleration experienced in the vehicle. Consequently, this incremental approach has the capacity to enhance both the precision of lateral displacement and lateral velocity measurements.

Table 1 compares the lateral error and lateral velocity using three algorithms as well as manual calibration. Regarding root mean square values for lateral displacement, the PSO algorithm exhibits a value of 0.2274 meters, outperforming manual calibration (1.124 meters), ABC (1.5092 meters), and GA (1.0747 meters). Moreover, the results across various values in the PSO algorithm consistently demonstrate superior performance compared to the other algorithms under consideration.

The lateral displacement and lateral velocity differences between the MiL and HiL are evident in

Table 2. Notably, simulation values obtained from the HiL are larger than those generated by the MiL. Similarly, there are errors between the results obtained from the MiL and the HiL, particularly up to 53.23% with lateral displacement and 78,89% lateral velocity when we use REC method to validate. Because the value of lateral velocity is too small, this REC value is too much. When we use the maximum absolute value method to validate the difference between the results obtained from the MiL and the HiL, the figure for lateral displacement and lateral velocity are 2.35m and 0.28m/s, respectively. This divergence can be caused by the cyclic delay existing between Xpack and ADAS and the computer.

5. Conclusions

This study presents three optimization algorithms ABC, GA and PSO to fine-tune LQR parameters based on open source software for automated vehicle Apollo frameworks. These algorithms aim to overcome the reliance on empirical methods and enable a data-driven approach to LQR calibration. The study highlights the superiority of the PSO algorithm by comparing the outcomes of this optimization algorithm to the manual, ABC, GA LQR controller within the MiL simulation. Finally, the PSO algorithm is simulated on a HiL, the result shows the gap between the MiL and the HiL simulation.

In the future, our works will continue to focus on optimizing and enhancing our system, especially focusing on the controllers and path planning, where MPC and Reinforcement learning can be applied. Moreover, the more complex traffic scenarios will be used to test and validate the reality of Apollo on the test bench and real car.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, D.B. and H.L.; methodology, D.B. and H.L.; software, D.B. and H.L.; validation, D.B., H.L. and F.D.; formal analysis, D.B. and H.L.; investigation, D.B. and H.L.; resources, D.B. and H.L.; data curation, D.B. and H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, D.B., H.L., F.D. and A.E.; visualization, D.B. and H.L.; supervision, A.E.; project administration, A.E.; funding acquisition, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding by the Graz University of Technology. This activity is part of the research project InVADE (FFG nr. 889349) and has received funding from the program Mobility of the Future, operated by the Austrian research funding agency FFG. Mobility of the Future is a mission-oriented research and development program to help Austria create a transport system designed to meet future mobility and social challenges.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Zhengguo Gu for his valuable internship support, which greatly contributed to the success of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Additionally, the authors declare that this study received funding from the Austrian research funding agency FFG within the scope of the research project InVADE. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Singh, S. Critical reasons for crashes investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey, 2018.

- Paden, B.; Čáp, M.; Yong, S.Z.; Yershov, D.; Frazzoli, E. A survey of motion planning and control techniques for self-driving urban vehicles. IEEE Transactions on intelligent vehicles 2016, 1, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebly, A.; Talj, R.; Charara, A. Coupled longitudinal/lateral controllers for autonomous vehicles navigation, with experimental validation. Control Engineering Practice 2019, 88, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jia, F.; Jing, H.; Liu, Z.; Güvenç, L. Coordinated longitudinal and lateral motion control for four wheel independent motor-drive electric vehicle. IEEE transactions on Vehicular Technology 2018, 67, 3782–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Xiao, Y. Data-driven control of autonomous vehicle using recurrent fuzzy neural network combined with PID method. 2018 37th chinese control conference (ccc). IEEE, 2018, pp. 5239–5244.

- Yang, T.; Bai, Z.; Li, Z.; Feng, N.; Chen, L. Intelligent vehicle lateral control method based on feedforward+ predictive LQR algorithm. Actuators 2021, 10, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.; Liu, X.; Lu, C. Lateral control using parameter self-tuning LQR on autonomous vehicle. 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Automation and Systems (ICICAS). IEEE, 2019, pp. 913–917.

- Xu, S.; Peng, H. Design, analysis, and experiments of preview path tracking control for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2019, 21, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, B.; Swamy, N.; Mukherjee, S. Trajectory tracking of autonomous vehicles using different control techniques (pid vs lqr vs mpc). 2020 International conference on smart technologies in computing, electrical and electronics (ICSTCEE). IEEE, 2020, pp. 84–89.

- Tagne, G.; Talj, R.; Charara, A. Design and comparison of robust nonlinear controllers for the lateral dynamics of intelligent vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2015, 17, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Niu, C.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, G. Research on intelligent vehicle trajectory planning and control based on an improved terminal sliding mode. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Tang, X.; Qin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Pu, H. Comparative study of trajectory tracking control for automated vehicles via model predictive control and robust H-infinity state feedback control. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2021, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, E.; Puig, V.; Quevedo, J. LPV-MPC control for autonomous vehicles. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.; Borrelli, F.; Asgari, J.; Tseng, H.E.; Hrovat, D. Predictive active steering control for autonomous vehicle systems. IEEE Transactions on control systems technology 2007, 15, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.A.; Milman, R.; Eklund, J.M. Obstacle avoidance in real time with nonlinear model predictive control of autonomous vehicles. Canadian journal of electrical and computer engineering 2017, 40, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkers, A.; Rick, M.; Büskens, C. Controlling an autonomous vehicle with deep reinforcement learning. 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE, 2019, pp. 2025–2031.

- Dai, X.; Li, C.K.; Rad, A.B. An approach to tune fuzzy controllers based on reinforcement learning for autonomous vehicle control. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2005, 6, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, N.; Lasheen, A.; Elnaggar, M.; Kamel, A. Model predictive control with fuzzy logic switching for path tracking of autonomous vehicles. ISA transactions 2022, 129, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohara, H.; Murakami, T. A stability control by active angle control of front-wheel in a vehicle system. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2008, 55, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, J.; Zhang, H. Lateral Stability Analysis of 4WID Electric Vehicle Based on Sliding Mode Control and Optimal Distribution Torque Strategy. Actuators 2022, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. A robust lateral tracking control strategy for autonomous driving vehicles. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2021, 150, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapania, N.R.; Gerdes, J.C. Design of a feedback-feedforward steering controller for accurate path tracking and stability at the limits of handling. Vehicle System Dynamics 2015, 53, 1687–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhao, R. LQR-MPC-Based Trajectory-Tracking Controller of Autonomous Vehicle Subject to Coupling Effects and Driving State Uncertainties. Sensors 2022, 22, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.; Lu, Z.; Li, R.; Tian, G. Adaptive LQR Path Tracking Control for 4WS Electric Vehicles Based on Genetic Algorithm. 2022 6th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Wang, Z.; Sun, K.; Ma, S.; Sun, L.; Gao, W.; Dong, Z. Improved Linear Quadratic Regulator Lateral Path Tracking Approach Based on a Real-Time Updated Algorithm with Fuzzy Control and Cosine Similarity for Autonomous Vehicles. Electronics 2022, 11, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhao, F. Research on Path Planning and Tracking Control of Autonomous Vehicles Based on Improved RRT* and PSO-LQR. Processes 2023, 11, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Nalic, D.; Makkapati, V.; Eichberger, A.; Fang, X.; Tettamanti, T. A real-time co-simulation framework for virtual test and validation on a high dynamic vehicle test bed. 2021 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1132–1137.

- Li, H.; Makkapati, V.P.; Wan, L.; Tomasch, E.; Hoschopf, H.; Eichberger, A. Validation of Automated Driving Function Based on the Apollo Platform: A Milestone for Simulation with Vehicle-in-the-Loop Testbed. Vehicles 2023, 5, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.Y.; Choi, W.S.; Choi, S.G. Real-Time Path Planning for Trajectory Control in Autonomous Driving. 2022 24th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT). IEEE, 2022, pp. 154–159.

- Lee, T.; Seo, D.; Lee, J.; Kang, Y. Real-Time Drift-Driving Control for an Autonomous Vehicle: Learning from Nonlinear Model Predictive Control via a Deep Neural Network. Electronics 2022, 11, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J. Real-time Parameter Updating and Path-following Control for Autonomous Vehicles on Slope Roads. International Journal of Control, Automation and Systems 2022, 20, 2178–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Gonzalez, I.; Gonzalez-Garcia, A.; Sotelo, C.; Sotelo, D.; Castañeda, H. A Real-Time NMPC Guidance Law and Robust Control for an Autonomous Surface Vehicle. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liniger, A.; Lygeros, J. Real-time control for autonomous racing based on viability theory. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2017, 27, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://developer.apollo.auto/index.html.

- Jazar, R.N. Vehicle dynamics; Springer, 2008; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.; Zhu, F.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhuang, L.; Li, D.; Zhu, W.; Hu, J.; Li, H.; Kong, Q. Baidu apollo em motion planner. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1807.08048. [Google Scholar]

- 2022. Available online: https://github.com/ApolloAuto/apollo.git.

- Li, H.; De Cristofaro, F.; Orucevic, F.; Zhengguo, G.; Eichberger, A. Quantitative Analysis of the Impact of Baidu Apollo Parameterization on Trajectory Planning in a Critical Scenario. ZIRP 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erik, R.B. Aufbau von validierten Fahrzeugmodellen; Master thesis. submitted to Graz University of Technology, 2023.

- T. Kanuric BSc, H. T. Kanuric BSc, H. Li MSc, A.P.D.I.D.t.A.E. Advanced Lane Detection Model for the Virtual Development of Highly Automated Functions. International ViennaMotor Symposium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Technical report. Available online: https://ipg-automotive.com/en/products-solutions/software/carmaker/.

- Technical report. Available online: https://www.ksengineers.com/.

- Proposed CM-S-014 Modelling & Simulation – for consultation. Technical report, European Union Aviation Safety Agency, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).