1. Introduction

Coronaviral diseases are well-known in both veterinary and human medicine. The ability of these viruses to spread from one species to another is also observed in many cases [

1]. Viruses in the

Coronaviridae family have positive-sense, single-stranded, enveloped RNA with outstanding genetic plasticity (eg. mutations and recombinations); this also explain the remarkable host adaptation ability.

The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first discovered in 2019 in Wuhan, China (

Figure 1). Since then, the disease caused by the virus (COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019) spread rapidly worldwide and induced a pandemic, declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the 11

th of March 2020. Until now, globally there have been almost 772 million confirmed cases, including cc. 7 million deaths, reported to WHO [

2].

The origin of SARS-CoV-2 is controversial, but according to the hypothesis, the spread and maintenance include animals as intermediate hosts, most likely [

3]. Besides having potential zoonotic origins, there are several descriptions in the literature, that the virus spreads from humans to companion or zoo animals (anthropozoonosis) [

4,

5,

6,

7] in natural circumstances. Felids are expressly susceptible to the infection, presumptively due to the similarity of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors compared to human ACE2 receptors [

8]. There is a single interacting amino acid residue conserved between human and feline species, but not in canine species. In most cases, the infected pets are asymptomatic, and only retrospective studies of seroprevalence reveal their formerly infected status [

9,

10]. In case they show clinical signs, they are mostly very mild upper respiratory symptoms, sometimes gastrointestinal signs, but the fatal disease is rare, especially in felids [

5]. Clinical cases have been described sporadically, e.g. in Belgium, Hong Kong, the USA, France, Spain, the UK, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland [

11].

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of coronaviruses, the place of SARS-CoV-2 (Balka et al., 2020; [

12]).

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of coronaviruses, the place of SARS-CoV-2 (Balka et al., 2020; [

12]).

Although it seems to be very unlikely for the disease to be caught by humans from companion animals, there is one case published where a veterinarian in Thailand developed COVID-19 presumably after having contact with an infected cat [

13]. Moreover, the virus’s ability to replicate in various hosts maintains the risk of the emergence of new strains and variants which means potential and constant human health risks.

This study shows clinical, pathological, and laboratory aspects of a fatal case of SARS-CoV-2 infection of a domestic cat. Detailed data provided here can be helpful in the future to recognize and manage more susceptible animals, like feline species, to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and animal experimentation

With regard to the EU conform Hungarian laws (Act XXVIII of 1998; Decree 40/13), this case did not contain animal research, the animal was treated according to its clinical symptoms. The clinical procedures involving the animal were carried out in accordance with biosafety and ethical guidelines. Necropsy and further auxiliary examinations were carried out with the consent of the cat’s owner.

2.2. Clinical evaluation

A seven-year-old European shorthair neutered male cat was presented to Blöki Veterinary Clinic, Hungary, with mild upper respiratory signs. We recorded the patient history, body weight, heart rate, body temperature, and results of physical examination (especially respiratory status). Additionally, we carried out laboratory analyses to further clarify the cat’s clinical status. Serum and EDTA-anticoagulated blood were collected for biochemical and hematologic examination from the cephalic vein. Hematologic analysis was carried out with an Advia 560 System (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., United States). Clinical biochemistry was made with Vetscan VS2 Chemistry Analyzer (Zoetis, Parsippany–Troy Hills, NJ, USA) – serum total protein, albumin, urea, creatinine, ALT, ALKP, GGT, α-amylase, lipase, CK, phosphate, and potassium levels were measured. Both examinations were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Pathologic examination and sample collection

The carcass of the cat was admitted for necropsy to the Department of Pathology, University of Veterinary Medicine, Budapest, after cc. 12 hours of cooling at 4°C. Gross postmortem examination was made at dorsal recumbency: after external examination and skinning of the animal, we opened the body cavities and took approximately 1 cm3 sample of organs (spleen, liver, kidneys, mesenteric lymph node, adrenal gland, lungs [from each lobe], heart [from both ventricles], bronchial lymph node, skeletal muscle, brain [both from cerebrum and cerebellum]) or 1 cm sections of the stomach, small and large bowels, trachea, for histopathology and/or in situ hybridization (ISH). Parallelly, we took pictures of pathologic lesions for documentation.

2.4. Histopathology and in situ hybridization

Histopathologic and ISH samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 hours at room temperature. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and submitted to routine histological examination.

For the RNAscope ISH assay, we cut 5 µm thin sections, which were mounted on Super-Frost Plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) [

14]. The steps of ISH were performed manually, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (with RNAscope 2.5 high definition (HD) red kit; Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) as described formerly [

15]. In brief, the sections were deparaffinized in xylene (2–5 minutes), then they were rehydrated in a series of 96% alcohol (2–3 minutes). After 10 minutes of incubation in hydrogen peroxide at room temperature, sections were exposed to a retrieval buffer for 15 minutes at 95–102°C and treated with protease at 40°C for 30 minutes. Hybridization with the target RNA-specific oligonucleotide probe for COVID (RNAscope Probe-V-nCoV2019-S [catalog no. 848561]) on experimentally infected hamster lung sections and our case of cat samples, a housekeeping positive control (RNAscope positive control probe Fc-PPIB [catalog No. 455011]), and a bacterial negative control (RNAscope negative control probe-DapB [catalog 310043]) was implemented for 2 hours at 40°C. After the hybridization, signal amplification steps with amplifiers 1–6 were done according to the manufacturer’s instructions – the labeled probes containing a red chromogenic enzyme bind to multiple binding sites on the amplifiers. For counterstaining, we used Gill II modified hematoxylin treatment for 1 minute, then the slides were cover-slipped after 15–20 minutes of air drying at 60°C. Each single targeted viral RNA transcript molecule appeared with light microscopy as a distinct dot of red chromogen precipitate.

2.5. Molecular diagnostics, RT-qPCR

During the autopsy, mostly parallel samples (n=28) were obtained for both histopathology assays and molecular diagnostics: native tissue samples (n=21), body fluids (n=3), and swab samples (n=4) were taken into Viral Transport Medium (VTM). Tissues: mesentery, jejunum, colon, penis, mesenteric lymph node, adrenal gland, spleen, liver, kidney, bronchial lymph node, heart, parotid gland, macroscopically intact lung, inflamed lung, stomach, tongue, mandibular lymph node, thyroid gland, spinal cord, frontal lobe, cerebellum. Body fluids: urine, ascites, vitreous body. VTM: lower respiratory discharge, eye discharge, nasal discharge, and esophageal discharge.

Collected native tissue samples were homogenized in 1000 µL Dulbecco′s Modified Eagle′s Medium (DMEM) using a ceramic bead-based MagNA Lyser instrument (Roche Life Sciences, Basel).

Viral RNA was isolated from 200 µL specimens using the Roche MagNA Pure LC 2.0 Instrument and the MagNA Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche Life Sciences, Basel). To detect viral RNA, RT-qPCR was performed on the LightCycler 480 Instrument II platform using the LightCycler Multiplex RNA Virus Master kit (Roche Life Sciences, Basel). The applied primers and probe were specific for the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid 1 (N1) gene [

16]. The virus copy number was calculated according to a standard curve of a commercial copy control standard (EURM-019) purchased from the European Commission Joint Research Center.

To investigate, whether the cat had other viral diseases, we performed end-point PCR for FIV (feline immunodeficiency virus), RT-PCR for FeLV (feline leukemia virus), real-time RT-PCR for FHV (feline hepadnavirus), and FeMV (feline morbillivirus). Primers used in these examinations are indicated in

Table 1. Protocols for FIV and FeLV were described earlier [

17]. For the detection of FHV and FMV, we used the QuantiNova SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer activation and binding happened at 95°C for 5 minutes, then denaturation was 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 minutes. Annealing and extension were 60°C for 10 seconds [

18,

19].

2.6. Next generation sequencing

Whole genome sequencing was conducted by the National Public Health Center, National Biosafety Laboratory, Hungary from the samples marked with # in

Table 2. For viral genome amplification, the ARTIC V3 primer scheme was used. According to the low viral load, some modifications were performed to the original protocol. Library preparation was performed using the Illumina Nextera XT protocol according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, USA). For sequencing V2 chemistry (300 cycles) with 2×150 bp paired-end reads were performed using Illumina MiSeq (Illumina Switzerland GmbH, Zurich, Switzerland). Bioinformatics analyses were performed using Geneious Prime software. Clade assignment and phylogenetic visualization were determined using the Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak Lineages (PANGOLIN) software (

https://pangolin.cog-uk.io/) and the Nextstrain online software (

https://clades.nextstrain.org/).

2.7. Virus isolation on cell culture

Virus isolation was performed on specimens with a possibly adequate viral load on confluent Vero E6 (ATCC CRL-1586) and Vero E6-TMPRSS (VCeL-Wyb051) cells in DMEM medium containing Cell Culture Guard (VWR International, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 7 days under BSL-3 conditions.

2.8. Bacterial cultivation

To rule out bacterial infections, cultivation from lungs, liver, and spleen was made on bloody agar both under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, at 37°C.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical evaluation

A seven-year-old European shorthair neutered male cat was presented to Blöki Veterinary Clinic, with signs of hyperthermia and bilateral serous nasal discharge. It weighed 3.8 kg, and the body condition score (BCS) was 4 on a scale of 9. The owners did not know about any other, former diseases. Five days previously, almost the whole family had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection with mild upper respiratory symptoms, and the cat had contact with these family members. The cat soon developed a fever. Treatment included amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, tolfenamic acid, Salsol and Duphalyte infusion, and vitamin B12. Its general condition soon got worse despite the treatments. After two days, it showed bilateral serous conjunctivitis, sneezing, anorexia, and mild anemia. With physical examination, we could hear moderately coarse crackles and reduced breath sounds in the lower third of the thorax.

Regarding serum biochemical findings, we found mild elevation of urea (19.1 mmol/L) and creatinine (234 μmol/L) levels. Regarding hematologic analysis, a higher white blood cell count (7.8×109/L) and lymphocyte ratio (65%), but a lower red blood cell count (3.4×1012/L) and hematocrit (24 L/L) level were found.

Due to worsening clinical status, antibiotic treatment was changed to marbofloxacin, but the hematocrit level further decreased, and the animal developed severe mixed-type dyspnea. We found severe crackle noise in the upper third, and no breath sounds in the lower third of the thorax. A single dose of methylprednisolone (75 mg) was administered, but five days after the initial clinical signs the cat became critically ill. It died on day 6.

3.2. Postmortem evaluation

The cat was in poor condition, BCS was lower than normal. As we opened the abdominal cavity, a low amount of fresh (cc. 100 ml), and a larger amount of coagulated blood were found, mainly situated around the liver. Some clots adhered to the liver lobes. The gastric mucosa at the antral and pyloric part was scattered with erosions and ulcers. The pelvic area of the right kidney was dilated. In the thoracic cavity, we observed heavy, fluid-filled lungs – especially the left lobes affected. We also found thick mucoid discharge in the distal part of the trachea and in the lower airways (

Figure 2).

3.3. Histopathologic and ISH findings

With routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, we observed severe lesions in the liver and lungs, moderate lesions in the kidney, and the above-described erosions and ulcers in the gastric mucosa. In the liver, we noticed multifocal-to-coalescing necrosis with smaller and bigger spots of hemorrhages. The right kidney showed multifocal interstitial plasmacytic infiltration accompanied by fibrosis (

Figure 3). With the examination of the lungs, we observed the same type of lesions as we can see in human patients who died due to COVID-19. In all lobes, but most severely in the left lobes, we found extreme alveolar edema, extensive alveolar damage, and diffuse hyaline deposition. Besides the lung lesions, we also detected signs of multifocal heart muscle degeneration, although macroscopically the heart seemed to be intact (

Figure 4).

In the case of in situ hybridization, although we could detect strong positive staining (red chromogen precipitates) on positive control slides of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters and the housekeeping control, we could not detect any sign on sections gained from the cat.

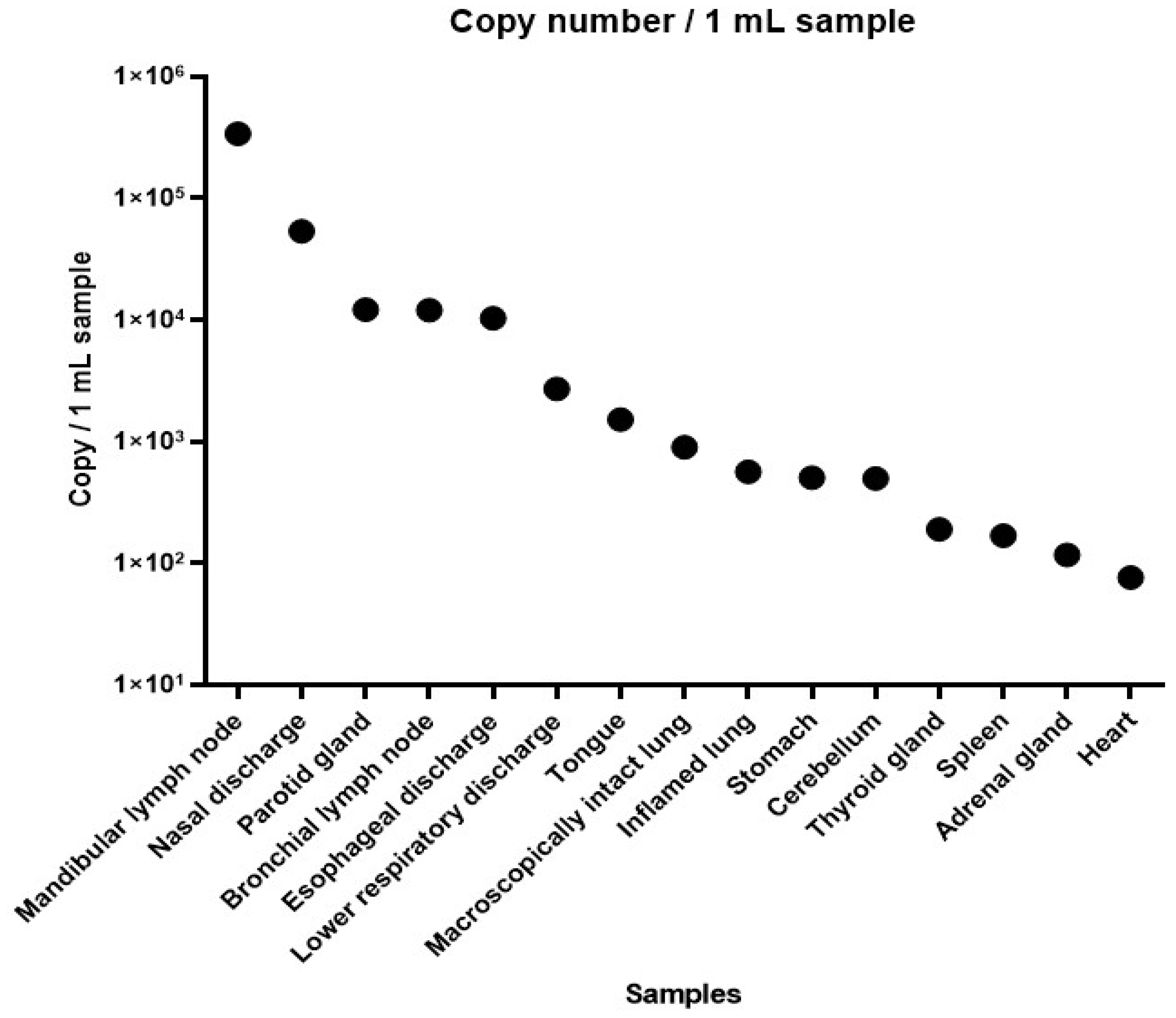

3.4. Molecular diagnostic findings

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detectable in 15 out of 28 collected specimens as seen in

Table 2. Ct values were between 25.88 (highest viral load) and 37.99 (lowest viral load) (

Figure 5).

3.5. Whole genome sequencing

All genomes shared high levels of identity to SARS-CoV-2 (99.96–99.98%) and contained the characteristic mutations of the B.1.617.2 variant. All genomes were compared with the reference sequence Wuhan-Hu-1 (MN908947). The genomes had high ambiguity scores (0,97-0,99) and belong to the Delta variant/B.1.617.2-AY.43 clade. While we screened the GISAID database, we found that only 20 whole genome sequences were uploaded in connection with Delta variant/B.1.617.2-AY infections in domestic cats and none of them were Delta variant/B.1.617.2-AY.43.

3.6. Virus isolation

Unfortunately, the virus isolation was unsuccessful in all specimens, namely mandibular lymph node, nasal discharge, bronchial lymph node, and parotid gland (Ct 25.88, 28.53, 30.69, and 30.68 respectively).

3.7. Bacterial cultivation

Bacterial cultivation was negative in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, therefore bacterial infections could be excluded from the background of observed lesions.

4. Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 is still causing thousands of deaths around the globe, although epidemiological measures and vaccination could take hold on the pandemic. Its impact cannot be underrated on the human population, and on human – companion animal relationships. Questions about the zoonotic potential (either animal to human or human to animal) have yet to be thoroughly answered. This case presents a rare, but potential outcome of anthropozoonosis of COVID-19. A domestic European short hair cat has died after 5 days of showing symptoms of COVID-19 - the owners have tested positive previously. With gross and microscopic examination, we could detect typical lesions referring to the disease. Unfortunately, in situ hybridization could not detect the pathogen in the tissues examined, however, the low viral load can be in the background of this phenomenon, even though RNAscope ISH is an exceptionally sensitive detection method. Other diseases, such as retroviral infections, morbilliviral and hepadnaviral diseases, and bacterial infections could be excluded with additional testing.

To confirm the presence of the virus, we performed RT-qPCR examinations. The SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected with a higher viral load on the mandibular, bronchial lymph node, and parotic gland. The mandibular lymph node showed the highest copy number, which in human cases is known as a reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 [

20]. Other organs had a relatively low copy number or even negative results of the virus which may arise that the carcass was not immediately dissected. We don’t have data about the level of RNAse activity of the organs, which may be behind the high Ct values and the unsuccessful virus isolation.

Whole genome sequencing is a powerful tool to identify the different SARS-CoV-2 variants and their unique mutations respectively. We performed a whole-genome sequencing pilot study of the SARS-CoV-2 samples derived from an infected domestic cat using the ARTIC protocol, which was previously implemented in the Illumina MiSeq platform and is a well-proven method for identifying the SARS-CoV-2 variant from samples with low viral copy numbers. All the samples gave identical results for the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant/B.1.617.2-AY.43, which was previously also detected from human autopsy samples. B.1.617.2 clade was the predominant clade in Hungary in the period of the study. As far as we know, we described the first case in a domestic cat infected with B.1.617.2-AY.43 SARS-CoV-2 in Hungary.

The presented case can contribute to further understanding of the pathomechanism of SARS-CoV-2 in feline companion animals. In spite of the fact that COVID-19 usually does not lead to mortality in felines, we have to keep the possibility in mind, especially when there is a known/suspected source of infection, such as an infected owner. In this case, we could not detect any underlying condition, which would facilitate the course of COVID-19 (eg. immunosuppression, other diseases). This can mean, that the initial dose of the virus was extremely high, although we can not prove this. The severity of the disease and the fact that the cat died pose further questions about SARS-CoV-2 in zoonotic cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Sz. and Gy.B.; methodology, L.D. and B.P.; software, D.D.; validation, D.D., J.H. and B.P.; formal analysis, A.Sz.; investigation, P.K. and A.Sz.; resources, M.M. and B.P.; data curation, A.Sz. and Gy.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Sz. and B.P.; writing—review and editing, Gy.B.; visualization, L.D.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, A.Sz. and P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Renáta Pop and Kitti Schönhardt for their contribution to histopathologic examinations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sykes, J.; Greene, C. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 4th ed.; Elsevier Saunders, Missouri, USA, 2012; 92.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland,. https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed , 2023). 10 October.

- Jo, W.K.; Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Rasche, A.; Greenwood, A. ; Osterrieder, K; Drexler, J. F. Potential zoonotic sources of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 68, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, E.C.; Reid, T.J. Animals and SARS-CoV-2: Species susceptibility and viral transmission in experimental and natural conditions, and the potential implications for community transmission. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1850–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosie, M.J.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hartmann, K.; Egberink, H.; Truyen, U.; Addie, D.D.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Frymus, T.; Lloret, A.; et al. Anthropogenic Infection of Cats during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2021, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haake, C.; Cook, S.; Pusterla, N.; Murphy, B. Coronavirus Infections in Companion Animals: Virology, Epidemiology, Clinical and Pathologic Features. Viruses 2020, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, G.; Javed, A.; Akter, S.; Saha, S. SARS-CoV-2 host diversity: An update of natural infections and experimental evidence. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2021, 54, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathavarajah, S.; Dellaire, G. Lions, tigers and kittens too: ACE2 and susceptibility to COVID-19. Evol. Med. Public Heal. 2020, 2020, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienzle, D.; Rousseau, J.; Marom, D.; MacNicol, J.; Jacobson, L.; Sparling, S.; Prystajecky, N.; Fraser, E.; Weese, J.S. Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection and illness in cats and dogs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczorek-Łukowska, E.; Wernike, K.; Beer, M.; Wróbel, M.; Malaczewska, J. High Seroprevalence against SARS-CoV-2 among Dogs and Cats, Poland, 2021/2022. Animals. 2022, 12, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/MM/A_Factsheet_SARS-CoV-2__1_.pdf accessed on 30th 23. 20 October.

- Balka, Gy.; Bálint, A. , Cságola, A. ; Farsang, A.; Jerzsele, A. et al. The biology of coronaviruses, with special regards to SARS-CoV-2-and COVID-19 – Literature review. Magy. Allatorvosok Lapja. 2020, 142, 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Sila, T.; Sunghan, J.; Laochareonsuk, W.; Surasombatpattana, S.; Kongkamol, C. Suspected Cat-to-Human Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Thailand, July–September 2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Flanagan, J.; Su, N.; Wang, L.-C.; Bui, S.; Nielson, A.; Wu, X.; Vo, H.-T.; Ma, X.-J.; Luo, Y. RNAscope: A Novel in Situ RNA Analysis Platform for Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissues. J. Mol. Diagn. 2012, 14, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szilasi, A.; Dénes, L.; Jakab, C.; Erdélyi, I.; Resende, T.; Vannucci, F.; Csomor, J.; Mándoki, M.; Balka, G. In situ hybridization of feline leukemia virus in a primary neural B-cell lymphoma. J. Veter- Diagn. Investig. 2020, 32, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.

- Szilasi, A.; Denes, L.; Kriko, E.; Murray, C.; Mandoki, M.; Balka, G. Prevalence of feline leukaemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus in domestic cats in Ireland. Acta Veter- Hung. 2020, 68, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, M.; Shi, M.; Barrs, V.R.; McLuckie, A.J.; Lindsay, S.A.; Jameson, B.; Hampson, B.; Holmes, E.C.; Beatty, J.A. A Novel Hepadnavirus Identified in an Immunocompromised Domestic Cat in Australia. Viruses 2018, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Wong, B.H.L.; Fan, R.Y.Y.; Wong, A.Y.P.; Zhang, A.J.X.; Wu, Y.; Choi, G.K.Y.; Li, K.S.M.; Hui, J.; et al. Feline morbillivirus, a previously undescribed paramyxovirus associated with tubulointerstitial nephritis in domestic cats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 5435–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuck, B.F.; Dolhnikoff, M.; Duarte-Neto, A.N.; Costa Gomes, G.M.S.; Sendyk, D.I. Salivary glands are a target for SARS-CoV-2: a source for saliva contamination. J. Pathol. 2021, 254, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).