1. Introduction

Insulin receptor is a tyrosine kinase that guides the action of insulin. It is encoded by INSR by a single gene located on chromosome 19 (19p13.2, Genomic coordinates (GRCh38): 19:7,112,265-7,294,414) which has 22 exons. INSR protein exists are as a tetramer of two alpha and 2 beta subunits linked by disulfide bonds. Binding of insulin molecules to INSR activates the kinase function leading to phosphorylation of multiple downstream substrates which mediate the actions of insulin in human metabolism. Mutations in the insulin receptor gene (INSR, MIM: *147670) are the root cause of multiple genetic disorders [

1,

2,

3,

4] including Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome (RMS, MIM: #262190), which is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder [

5,

6,

7] that affects endocrine, metabolic, and immune systems.

Classic features of RMS include Acanthosis nigricans (MIM: %100600), a skin condition that causes dark, velvety patches; dental abnormalities, growth retardation, and other systemic abnormalities [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Robert Rabson and Edwin Mendenhall reported two siblings with features of diabetes mellitus, acanthosis nigricans, and abnormal dentition in 1956, when the disorder was described for the first time [

8]. From that point forward, only few cases of RMS have been accounted for around the world, and limited reports exist about the clinical and hereditary elements of the issue [

2,

5,

6,

10,

12]. RMS can appear in a variety of ways, and the severity of the condition can vary from person to person [

1,

9,

13]. While some patients present with milder forms of the disorder, others may have more severe manifestations such as early-onset diabetes, severe insulin resistance, and recurrent infections [

12,

14,

15]. It can be difficult to make a diagnosis because RMS’s clinical features may also overlap with those of other metabolic and genetic disorders [

16,

17,

18].

Clinical features, such as the presence of acanthosis nigricans, insulin resistance, and dental abnormalities, as well as laboratory tests that confirm hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, are used to make the diagnosis of RMS [

15,

19,

20]. The diagnosis is confirmed through genetic testing and the identification of a specific variant in the

INSR gene [

21,

22]. The management of RMS includes providing supportive care for dental and other systemic abnormalities, controlling hyperglycemia with insulin therapy, managing other associated conditions like hypertension and dyslipidemia. Individuals with RMS may have better long-term outcomes if they receive early diagnosis and treatment [

9,

10,

14,

18]. Further exploration is expected to grasp the metabolic components of RMS and foster more successful treatment methodologies for this perplexing problem [

13,

17].

2. Results

A 5-year-old girl from Colonel Oviedo, a rural area in Paraguay, first visited the clinic when she was 8 months old for a consultation due to suspected early puberty. Upon physical examination, the girl exhibited distinctive facial features, including acromegalic facies and an ogival palate (

Figure 1). Additionally, she displayed hyperkeratosis, rough skin, dry hair, and generalized hypertrichosis, indicating excessive hair growth across her body (

Figure 1). She had acanthosis nigricans in the neck, axilla, around the belly and inner face of both thighs in the upper third. She also had breast enlargement up to M3. The clitoris was hypertrophied, and the pubic hairs were hyperpigmented but not curly (Tanner 2). Crying revealed an umbilical and epigastric hernia, as well as a globular, distended abdomen without palpable visceromegaly (

Figure 1).

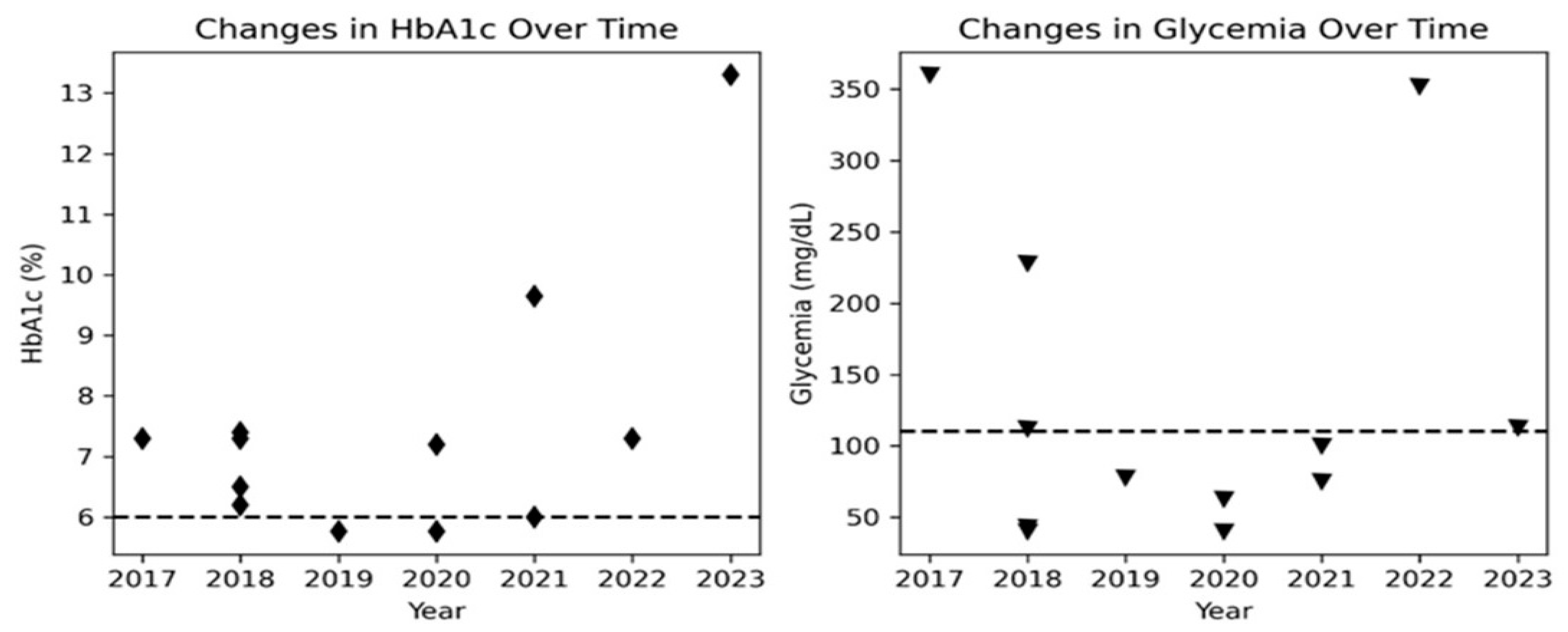

Biochemical laboratory values at the first visit revealed high glucose and insulin in blood (

Table 1), indicating insulin resistance syndrome. As a result, nutritional treatments were used to treat the patient until March 2021. However, she displayed glycaemia oscillations (

Figure 2), occasionally reaching 400 mg/dl and metformin (100 mg/day) was administered to the patient from November 2019. However, metformin treatment was discontinued later due to the patient’s young age [

9,

17,

23]. In 2020, a respiratory tract infection, possibly COVID, caused the patient’s condition, metabolic parameters and acanthosis to worsen. Fruit restriction, increased monitoring, resuming metformin therapy, and referral for genetic testing were all part of the treatment.

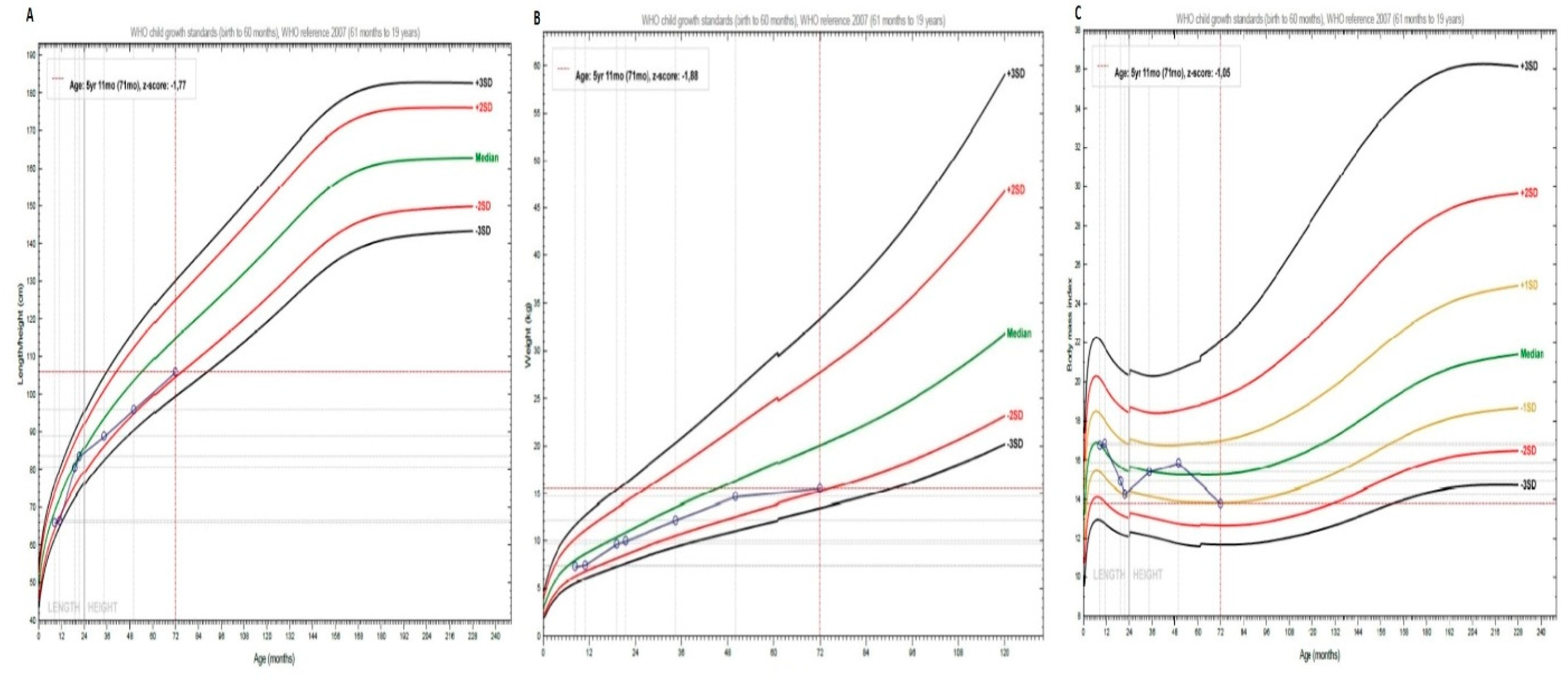

At the initial visit, with 8 months of age the patient showed a length of 66 cm (-2.0 SDS) followed by a transitory catch-up growth at 20 months and subsequently faltering of her growth and height at age 4 and 6 years at -2 SDS (

Figure 3A). The patient always showed an appropriate weight gain up to age 4 years. Between 4-6 years of age she only gained 0.9 kg of weight (

Figure 3B). However, the BMI remained in the normal range with 13.8 kg/m2 (-1.0 SDS) (

Figure 3C).

In summary, her acromegalic facies, ogival palate, hyperkeratosis, rough skin, dry hair, generalized hypertrichosis, breast enlargement, and clitoris hypertrophy are suggestive of RMS [

11,

15,

19].

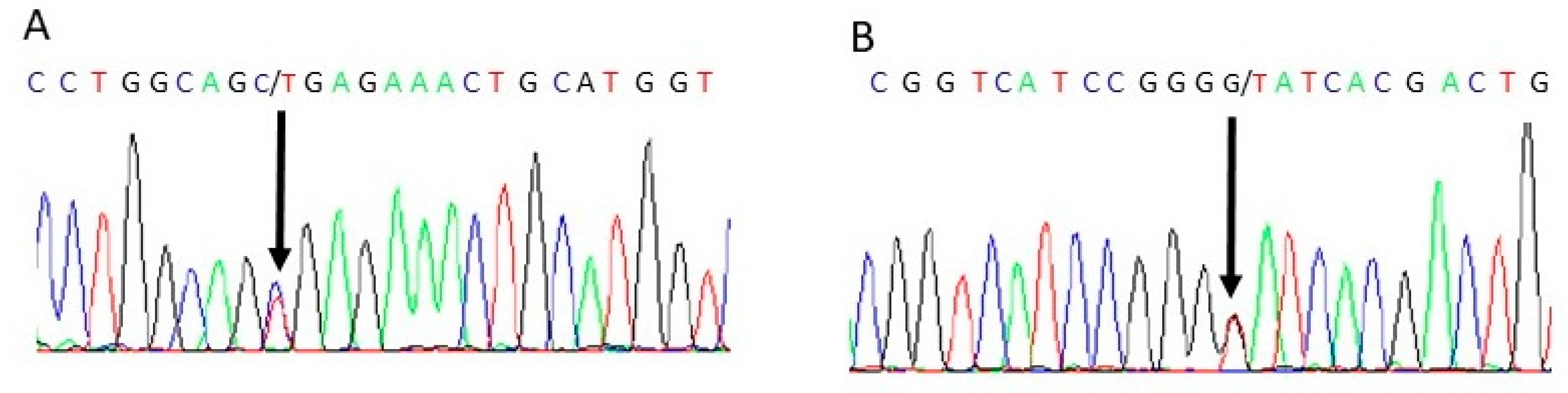

The patient in this case report presented with a constellation of clinical features consistent with RMS. Genetic testing confirmed the suspected diagnosis, revealing two pathogenic variants in the

INSR gene. Specifically, the patient presented in combined heterozygosis the c.332G>T (p. Gly111Val) and with c.C3485T (p. Ala1162Val) and c. G332T (p. Gly111Val) in heterozygous state in exons 18 and 2 of the INSR gene, respectively (

Figure 4).

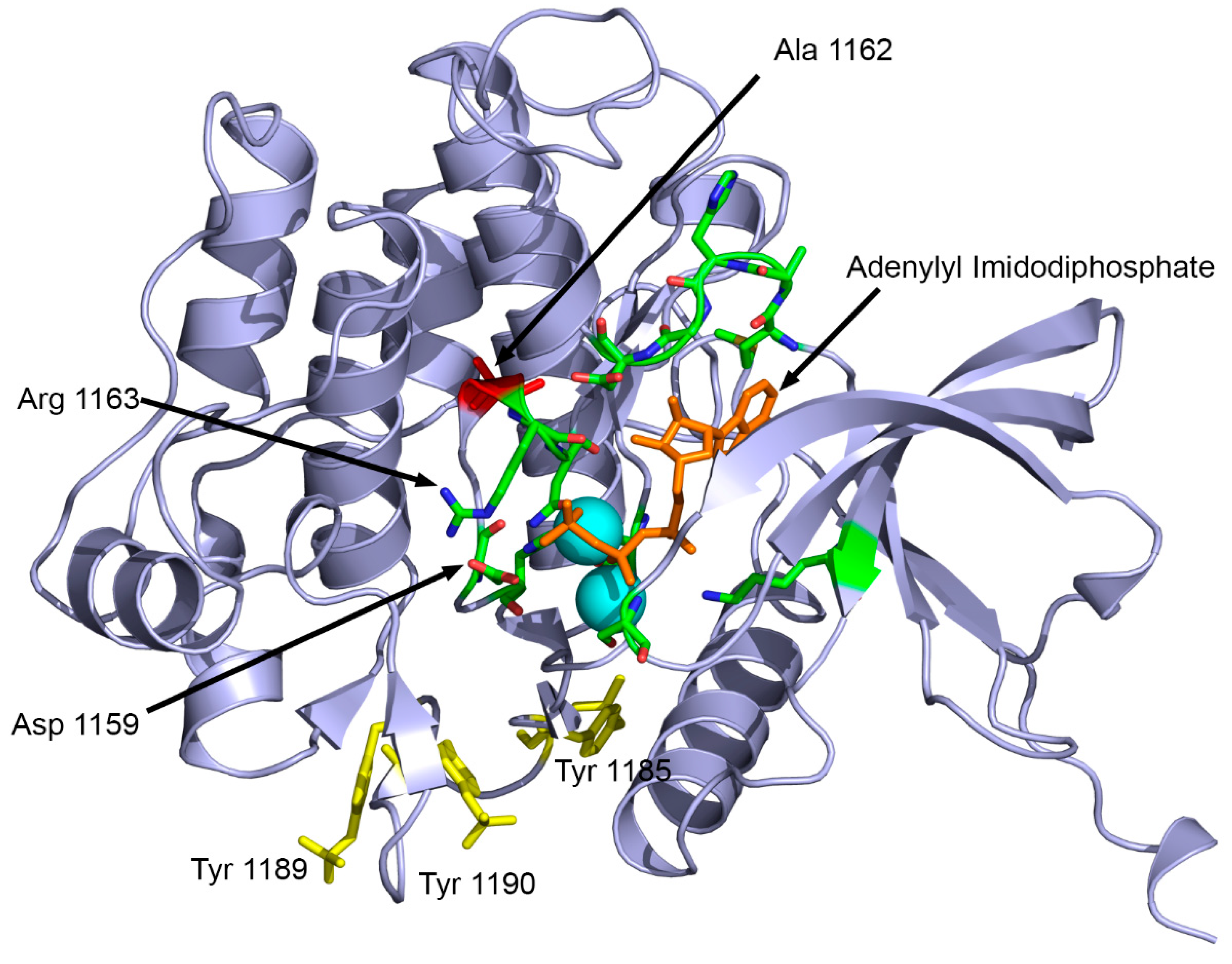

INSR c. C3485T, leads to the substitution of alanine for valine at position 1162 in the protein. This variant has been previously described in the literature in cases of insulin resistance and Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome [

35]. Another study reported a different change in the same residue, where glutamic acid was substituted for alanine 1135 (a different isoform was used as reference sequence, therefore, there is a difference in numbers reported) in the putative “catalytic loop” of the tyrosine kinase domain of the human insulin receptor [

36]. The alanine 1162 is located close to residues involved in ATP binding (1163-1167) and the active site (1159) of INSR (

Figure 5). The mutation Ala1162Val potentially impairs the receptor tyrosine kinase activity of INSR due to disrupted ATP binding.

INSR c. G332T, on the other hand, leads to the substitution of glycine for valine at position 111 in the protein. Although this variant has not been previously described in the literature, several prediction software programs (Provean, SIFT, Polyphen2, Mutation Taster, SNPs&Go, MutPred) predicted it as pathogenic. Further functional studies would be necessary to confirm the pathogenicity of this variant.

3. Discussion

RMS is a rare genetic disorder characterized by severe insulin resistance, resulting in diabetes mellitus, hypertrichosis, acanthosis nigricans, and nephrocalcinosis [

18,

22,

37]. Early diagnosis and management are crucial to prevent complications and optimize the patient’s outcome and quality of life [

17].This case highlights the challenges in managing the complexity of RMS in a low-income setting [

9]. The rarity of this disease and the lack of awareness among healthcare professionals often lead to a delayed diagnosis and inappropriate treatment [

11,

38]. Moreover, genetic diagnosis in low-income families in Paraguay is particularly difficult. This is the first report of RMS in the Paraguayan population, where genetic testing is not readily available. However, genetic testing is essential for the accurate diagnosis and management of this disease [

21], as it can identify pathogenic variants in the INSR gene, such as c. 332G>T and c. 3485C>T and, which were found in this patient. The exact mechanism of pathogenic effects of mutations in INSR gene seem to be variable and include disrupted membrane localization [

39,

40], reduced binding to insulin [

41], impairment of proteolytic processing and transport to cell surface [

36].

The child showed poor linear growth and insufficient weight gain between age 4-6 years. These findings emphasize the need for comprehensive evaluation and management of the patient’s growth. Close monitoring, multidisciplinary intervention, and early interventions such as nutritional supplementation are crucial to optimize the patient’s growth trajectory and prevent potential long-term complications. Regular follow-up and adjustments to the management plan are necessary to track progress and enhance the patient’s overall growth and development [

8,

11,

20].

The insulin resistance and resulting diabetes mellitus are the hallmark features of this disease, and the management of diabetes is particularly challenging in children with this syndrome [

4,

12,

38]. The use of metformin, the first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes, is often limited by its side effects, and insulin therapy may be required at an early stage [

17,

23]. However, due to the young age of the patient, insulin therapy was not initiated, and the patient could be managed with appropriate diet. The nephrocalcinosis observed in this case is a known complication of RMS and reflects the underlying metabolic disruption [

16]. Close monitoring of renal function is essential in these patients, and regular imaging studies are required to detect any changes in the renal structure [

14,

16]. The hypertrichosis and acanthosis nigricans are also typical features of this syndrome and reflect the underlying insulin resistance. The cosmetic impact of these skin changes should not be underestimated, as they can significantly affect the quality of life of affected individuals [

5,

8].

Metreleptin, a recombinant analogue of human leptin, has been approved for the treatment of generalized lipodystrophy, a rare metabolic disorder characterized by loss of adipose tissue [

20,

23,

42]. Although there are no clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of metreleptin in the treatment of Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, some case reports have suggested that it may improve insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in patients with this condition [

20,

35]. However, the high cost of metreleptin therapy presents a significant barrier to access, particularly in low-income countries such as Paraguay. Therefore, while metreleptin may hold promise as a potential therapy for Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, its use is currently limited by economic factors and availability in this setting [

9,

21].

This case calls attention to the need for a multidisciplinary approach to the management of RMS. Regular follow-up visits and close monitoring of metabolic and renal function are essential to prevent complications and optimize the patient’s outcome. This case report emphasizes the importance of genetic testing in the diagnosis and management of rare genetic disorders such as RMS, especially in low-income settings. Early recognition and appropriate management can significantly improve the patient’s outcome and quality of life.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample preparation and DNA extraction

Blood samples were collected from the patient after obtaining written informed consent from parents. Extraction of DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes was performed using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification Kit (Promega, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol.

4.2. Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and bioinformatic analysis

WES was performed by Novogene (Novogene Company Limited, Cambridge, UJK). Libraries were prepared with a SureSelect Human All Exon V6 capture kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and sequenced with a Novaseq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Genome dataset was aligned with human genome GRCh38 and annotated with wANNOVAR [

24]. Variants were filtered by a DSD-related gene list [

25] and to identify rare variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of <1% in publicly available databases (dbSNP, ExAC, gnomAD), using R software (R 4.2.0). The possible effect of identified nonsynonymous genetic variants on the structure and function of the protein using Polyphen-2 (Polymorphism Phenotyping v2) [

26], SNPs&Go [

27], SIFT (Scale-invariant feature transform) [

28], Provean (Protein Variation Effect Analyzer) [

29], Mutation taster [

30] and MutPred [

31]. Variants were classified for pathogenicity according to the standards and guidelines of the ACMG [

32].

Structural analysis of disease causing variant Ala1162Val was performed using the known X-ray crystal structure of the INSR tyrosine kinase domain (PDB: 1IR3) in complex with an ATP analogue [

33] using Pymol (

www.pymol.org) and Yasara [

34].

4.3. Variant Validation:

The variants identified by WES were validated by Sanger sequencing. Primers were designed using SNAPGene and PCR was performed using Taq polymerase with the primers: 5’-CACCAACCCCGTGTTTCTG-3´, 5´-CCTGGCCTGGGTCGTTATG-3´, 5´- ACGAGGCCCGAAGATTTCC -3´ and 5´- CCCCGGGTGATGTTCATCAG-3´. The PCR products were then sequenced in Macrogen INC and the data obtained were analyzed using BioEdit version 7.2.5.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Sanger Sequencing for validation of variants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.R.V. and A.V.P.; methodology, M.N.R.V., F.B., A.A., L.F., V.J., D.D.T., I.M.D.L.; software, I.M.D.L., A.V.P.; validation, F.B., A.A., L.F., V.J., D.D.T., I.M.D.L ; formal analysis, M.J., C.E.F., A.V.P.; investigation, M.N.R.V., F.B., A.A., L.F., V.J., D.D.T., I.M.D.L.; resources, A.V.P..; data curation, M.N.R.V, F.B., A.A, ; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.R.V., F.B., A.A., M.J., ; writing—review and editing, A.V.P.; visualization, M.N.R.V. and A.V.P.; supervision, A.V.P; project administration, A.V.P; funding acquisition, A.V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.N.R.V was funded by the SWISS GOVERNMENT EXCELLENCE SCHOLARSHIP (ESKAS) grant number 2020.0557 and The open access funding was provided by University of Bern and swissuniversities.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects (parents) involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are provided in the paper, except whole exome sequencing data of the patient, which are not provided due to privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hosoe, J.; Kadowaki, H.; Miya, F.; Aizu, K.; Kawamura, T.; Miyata, I.; Satomura, K.; Ito, T.; Hara, K.; Tanaka, M.; Ishiura, H.; Tsuji, S.; Suzuki, K.; Takakura, M.; Boroevich, K. A.; Tsunoda, T.; Yamauchi, T.; Shojima, N.; Kadowaki, T. , Structural Basis and Genotype-Phenotype Correlations of INSR Mutations Causing Severe Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2017, 66(10), 2713–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wan, H.; Zhang, R.; Wang, C.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; Lu, J.; Gao, F.; Xiang, K.; Jia, W. , Functional characterization of insulin receptor gene mutations contributing to Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome - phenotypic heterogeneity of insulin receptor gene mutations. Endocr J 2011, 58(11), 931–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, A.; O’Rahilly, S.; Savage, D. B. , Genetic syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2018, 50, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudes, M.; Barroso, I.; Luan, J.; Soos, M. A.; Yeo, G.; Meirhaeghe, A.; Logie, L.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Schafer, A. J.; Wareham, N. J.; O’Rahilly, S. , Genetic variants in human sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c in syndromes of severe insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2004, 53(3), 842–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Yu, F.; Ma, Z.; Lu, H.; Luo, J.; Sun, T.; Liu, Q.; Gan, S. , INSR novel mutations identified in a Chinese family with severe INSR-related insulin resistance syndromes: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101(49), e32266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Abdelaziz, R.; Ben Chehida, A.; Azzouz, H.; Boudabbous, H.; Lascols, O.; Ben Turkia, H.; Tebib, N. , A novel homozygous missense mutation in the insulin receptor gene results in an atypical presentation of Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Eur J Med Genet 2016, 59(1), 16–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Kadowaki, H.; Ando, A.; Quin, J. D.; MacCuish, A. C.; Yazaki, Y.; Akanuma, Y.; Kadowaki, T. , Two aberrant splicings caused by mutations in the insulin receptor gene in cultured lymphocytes from a patient with Rabson-Mendenhall’s syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 1998, 101(3), 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabson, S. M.; Mendenhall, E. N. , Familial hypertrophy of pineal body, hyperplasia of adrenal cortex and diabetes mellitus; report of 3 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1956, 26(3), 283–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, S.; Shaheen, T.; Asif, R.; Anjum, M. N.; Saeed, A.; Manzoor, J.; Cheema, H. A. , Management challenges of Rabson Mendenhall syndrome in a resource limited country: a case report. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2022, 35(11), 1429–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzanowska, J.; Skarul, J.; Zubkiewicz-Kucharska, A.; Borowiec, M.; Zmyslowska, A. , Incomplete phenotypic presentation in a girl with rare Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Acta Diabetol 2023, 60(3), 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kohli, P.; Kumar, G. , Rare Ocular Complication in a Patient with Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. Indian J Pediatr 2021, 88(2), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushi, R.; Hirota, Y.; Ogawa, W. , Insulin resistance and exaggerated insulin sensitivity triggered by single-gene mutations in the insulin signaling pathway. Diabetol Int 2021, 12(1), 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojek, A.; Wikiera, B.; Noczynska, A.; Niedziela, M. , Syndrome of Congenital Insulin Resistance Caused by a Novel INSR Gene Mutation. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2023, 15(3), 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren Cakir, A.; Saidov, S.; Turan, H.; Ceylaner, S.; Ozer, Y.; Kutlu, T.; Ercan, O.; Evliyaoglu, O. , Two Novel Variants and One Previously Reported Variant in the Insulin Receptor Gene in Two Cases with Severe Insulin Resistance Syndrome. Mol Syndromol 2020, 11(2), 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, W.; Araki, E.; Ishigaki, Y.; Hirota, Y.; Maegawa, H.; Yamauchi, T.; Yorifuji, T.; Katagiri, H. , New classification and diagnostic criteria for insulin resistance syndrome. Endocr J 2022, 69(2), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S. R.; Pendyala, G. S.; Shah, P.; Pustake, B.; Mopagar, V.; Padmawar, N. , Severe insulin resistance syndrome - A rare case report and review of literature. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2021, 12(1), 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, T. J.; Haines, S. T. , Treatment Approach to Patients With Severe Insulin Resistance. Clin Diabetes 2016, 34(2), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Yu, J.; Yuan, X.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, A.; Gu, W. , Clinical and Functional Characterization of Novel INSR Variants in Two Families With Severe Insulin Resistance Syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 606964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, C.; Cochran, E.; Moran, S. A.; Skarulis, M. C.; Oral, E. A.; Taylor, S.; Gorden, P. , Clinical course of genetic diseases of the insulin receptor (type A and Rabson-Mendenhall syndromes): a 30-year prospective. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004, 83(4), 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okawa, M. C.; Cochran, E.; Lightbourne, M.; Brown, R. J. , Long-Term Effects of Metreleptin in Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome on Glycemia, Growth, and Kidney Function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022, 107(3), e1032–e1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.; Barroso, I.; Soos, M.; Yeo, G.; Schafer, A. J.; O’Rahilly, S.; Whitehead, J. P. Genetic variants of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) in syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Functional analysis of Ala513Pro and Gly1158Glu IRS-1. Diabet Med 2002, 19(10), 804–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, R. K.; Savage, D. B.; Cochran, E. K.; Gorden, P.; O’Rahilly, S. , Genetic syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Endocr Rev 2011, 32(4), 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, S. S.; Ramaldes, L. A.; Gabbay, M. A. L.; Moises, R. C. S.; Dib, S. A. Use of a Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor, Empagliflozin, in a Patient with Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. Horm Res Paediatr 2021, 94(7-8), 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, K. , Genomic variant annotation and prioritization with ANNOVAR and wANNOVAR. Nat Protoc 2015, 10(10), 1556–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camats, N.; Fluck, C. E.; Audi, L. Oligogenic Origin of Differences of Sex Development in Humans. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adzhubei, I.; Jordan, D. M.; Sunyaev, S. R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet 2013, Chapter 7. Unit7 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, E.; Calabrese, R.; Fariselli, P.; Martelli, P. L.; Altman, R. B.; Casadio, R. WS-SNPs&GO: a web server for predicting the deleterious effect of human protein variants using functional annotation. BMC Genomics 2013, 14 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3), S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P. C.; Henikoff, S. , SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31(13), 3812–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Chan, A. P. , PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics 2015, 31(16), 2745–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, R.; Proft, S.; Schuelke, M.; Cooper, D. N.; Schwarz, J. M.; Seelow, D. , MutationTaster2021. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49(W1), W446–W451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pejaver, V.; Urresti, J.; Lugo-Martinez, J.; Pagel, K. A.; Lin, G. N.; Nam, H. J.; Mort, M.; Cooper, D. N.; Sebat, J.; Iakoucheva, L. M.; Mooney, S. D.; Radivojac, P. Inferring the molecular and phenotypic impact of amino acid variants with MutPred2. Nat Commun 2020, 11(11), 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W. W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; Voelkerding, K.; Rehm, H. L.; Committee, A. L. Q. A. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 2015, 17(5), 405–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, S. R. , Crystal structure of the activated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase in complex with peptide substrate and ATP analog. The EMBO journal 1997, 16(18), 5572–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, E.; Vriend, G. , New ways to boost molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem 2015, 36(13), 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, R. O.; Zagury, R. L.; Nascimento, T. S.; Zagury, L. , Multidrug therapy in a patient with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome. Diabetologia 2010, 53(11), 2454–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cama, A.; de la Luz Sierra, M.; Quon, M. J.; Ottini, L.; Gorden, P.; Taylor, S. I. Substitution of glutamic acid for alanine 1135 in the putative “catalytic loop” of the tyrosine kinase domain of the human insulin receptor. A mutation that impairs proteolytic processing into subunits and inhibits receptor tyrosine kinase activity. J Biol Chem 1993, 268(11), 8060–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaie, A. S.; Ford-Adams, M.; Buchanan, C. R.; Arya, V. B.; Colclough, K.; Kapoor, R. R. , A novel heterozygous mutation in the insulin receptor gene presenting with type A severe insulin resistance syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2020, 33(6), 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosavi, S.; Sangamesh, S.; Ananda Rao, A.; Patel, S.; Hodigere, V. C. , Insulin, Insulin Everywhere: A Rare Case Report of Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. Cureus 2021, 13(2), e13126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, V. Y.; Hedo, J. A.; Serrano-Rios, M.; Taylor, S. I. , Insulin-Receptor Biosynthesis in Cultured Lymphocytes From an Insulin-Resistant Patient (Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome): Evidence for Defect Before Insertion of Receptor Into Plasma Membrane. Diabetes 1986, 35(7), 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, T.; Kadowaki, H.; Accili, D.; Taylor, S. I. , Substitution of lysine for asparagine at position 15 in the alpha-subunit of the human insulin receptor. A mutation that impairs transport of receptors to the cell surface and decreases the affinity of insulin binding. J Biol Chem 1990, 265(31), 19143–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. I.; Underhill, L. H.; Hedo, J. A.; Roth, J.; Rios, M. S.; Blizzard, R. M. Decreased Insulin Binding to Cultured Cells from a Patient with the Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome: Dichotomy between Studies with Cultured Lymphocytes and Cultured Fibroblasts*. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 1983, 56(4), 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, E.; Young, J. R.; Sebring, N.; DePaoli, A.; Oral, E. A.; Gorden, P. Efficacy of Recombinant Methionyl Human Leptin Therapy for the Extreme Insulin Resistance of the Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2004, 89(4), 1548–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).