The study investigates if it is possible to represent the impact of the upstream row mistuning on the aeroelastic excitation forces in this reduced domain. Of primary interest are the following topics:

For simplicity, the domain is reduced to the VSV1 and R2 rows. The VSV1 geometries are limited to the 36 deviations obtained from the optical surface scans.

3.1. MPMR Forcing Mixture

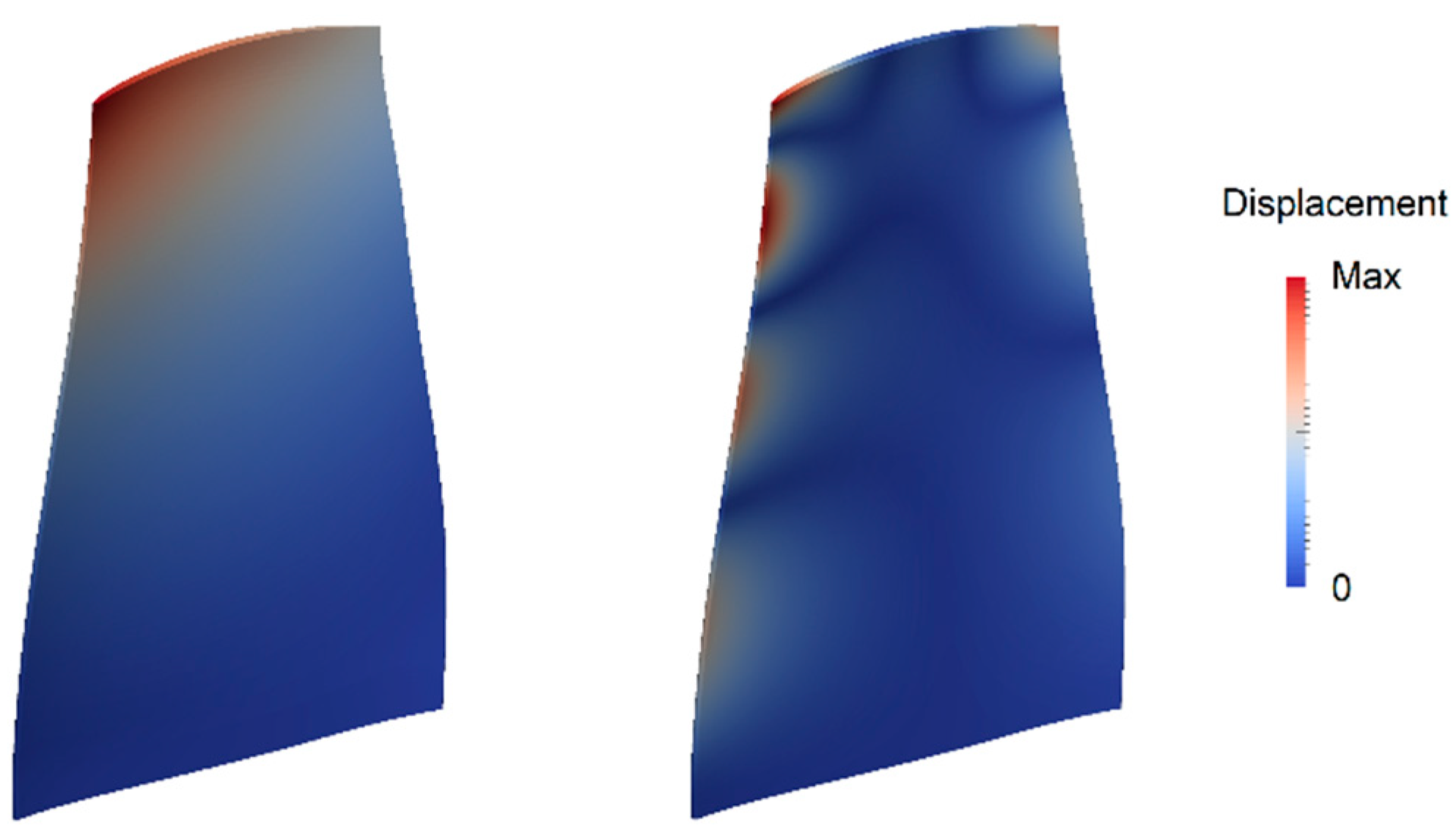

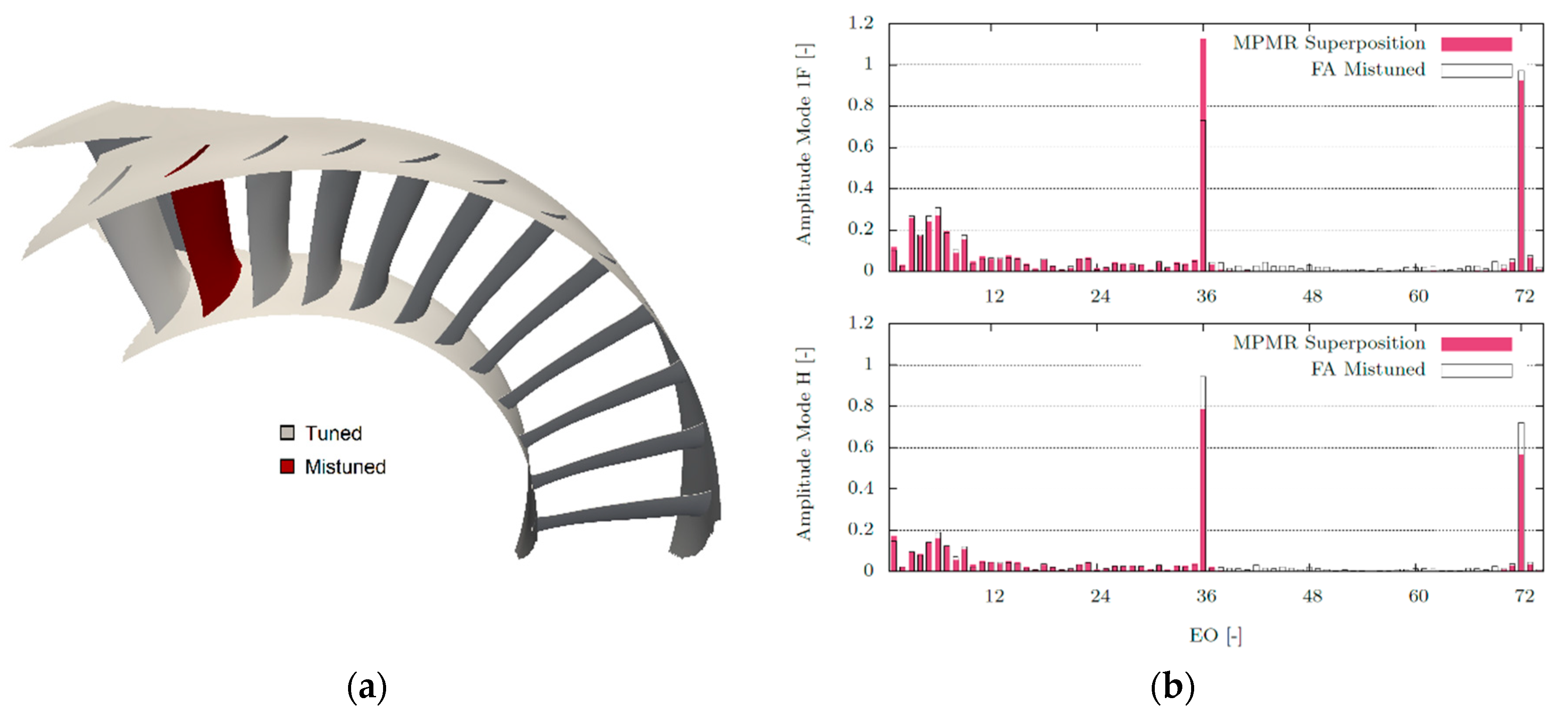

This method aims to verify if the local flow deviations downstream of the single mistuned VSV are sufficient to represent the overall mistuned flow. The reduced CFD setup includes three passages of the stator in a single sector. A single passage of the rotor is added, as for this row, the nominal geometry is used. In

Figure 6a the represented CFD domain is shown.

All three VSV1 aerofoils in each computation include the geometrical deviations modelled. Moreover, the vanes order considered for the investigated FA setup is kept. One simulation is run for each of the 36 assembly vanes. For each run, the geometry of the vane of interest is placed in the centre of the computational domain. The directly adjacent geometries on the suction and pressure side are the respective ones in the FA assembly.

The presence of multiple mistuned vanes in each MPMR solution would be a limitation when looking at a stochastic representation of the geometries. This would imply that the geometrical variability space generated on the single blade deviations would be tripled. The inclusion of 3 mistuned blades per solution is chosen to assess the methods capabilities in an example, using a small sector of the annulus, but with a high fidelity in terms of geometry.

As a result of each simulation, a forcing function on the R2 blade is calculated. The subscripts indicate the VSV1 blade at the centre of the sector and the R2 vibration mode considered. The superscript indicates that these solutions were computed using the CFD setup for the mixture method here presented. We indicate with N the number of total assembly vanes (N = 36 for VSV1).

The FA forcing prediction for the mode is computed as a mixture of MPMR solutions, using the definitions in Equations (6), (7) and (8). Indicating with the time required for a revolution, represents a vane passing time interval. A phase shift is added to the MPMR solutions, such as coincides with the wake of the central assembly vane. This is identified with the position of a minimum for the EO 36 in the nominal forcing function.

To ensure the continuity of the predicted FA forcing, each is mixed with the results centred on the neighbouring blades. This is done in the form of a weighted average over a selected time frame .

The first blade

and the last blade

in the assembly are adjacent. To represent this in a short notation, we define:

and

.

The reconstruction of the modal forcing

over one revolution is obtained as a concatenation of the weighted averages

for the single sectors. The periodic function over the full annulus is defined for a single period of length

, coinciding with the EO 1.

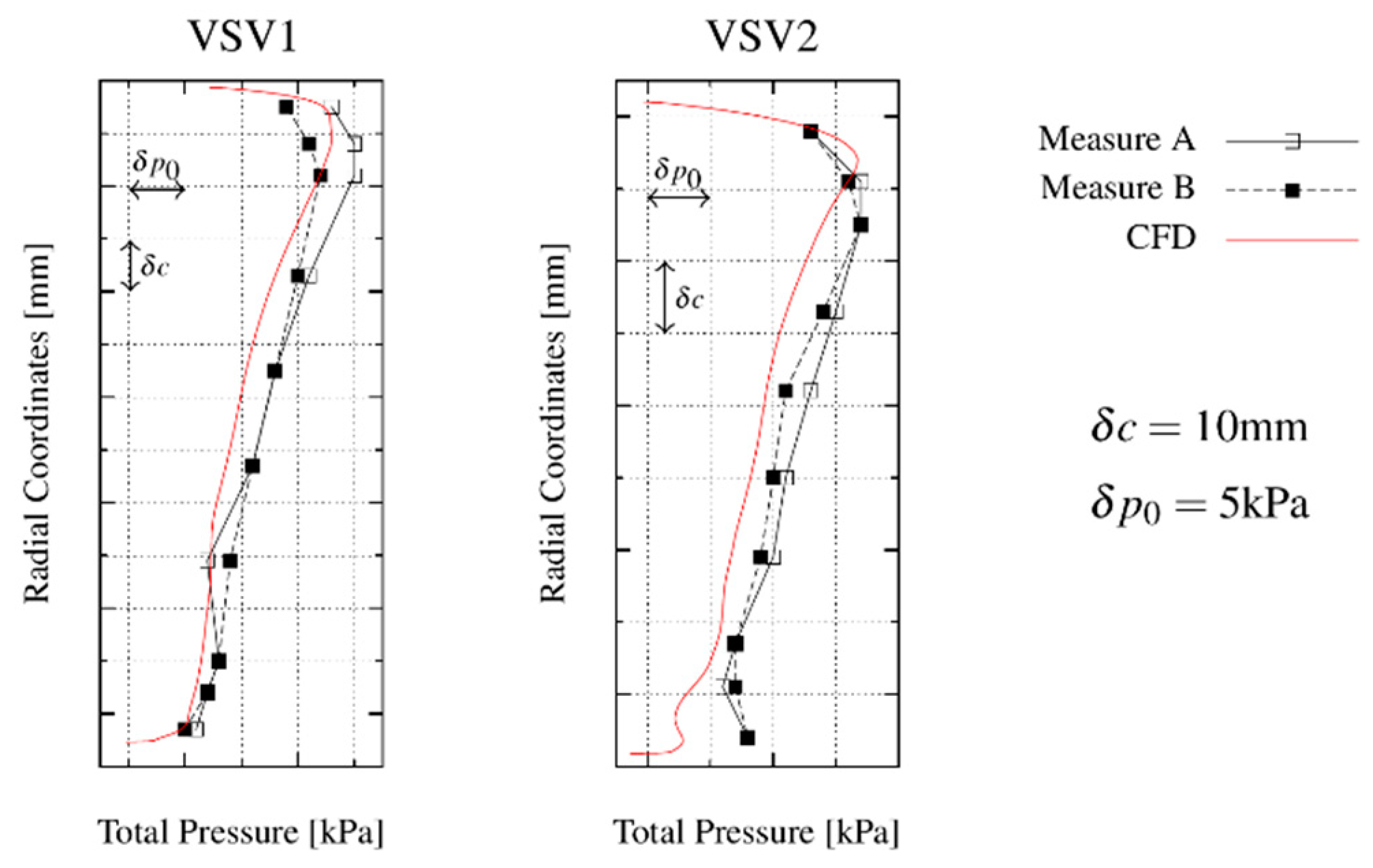

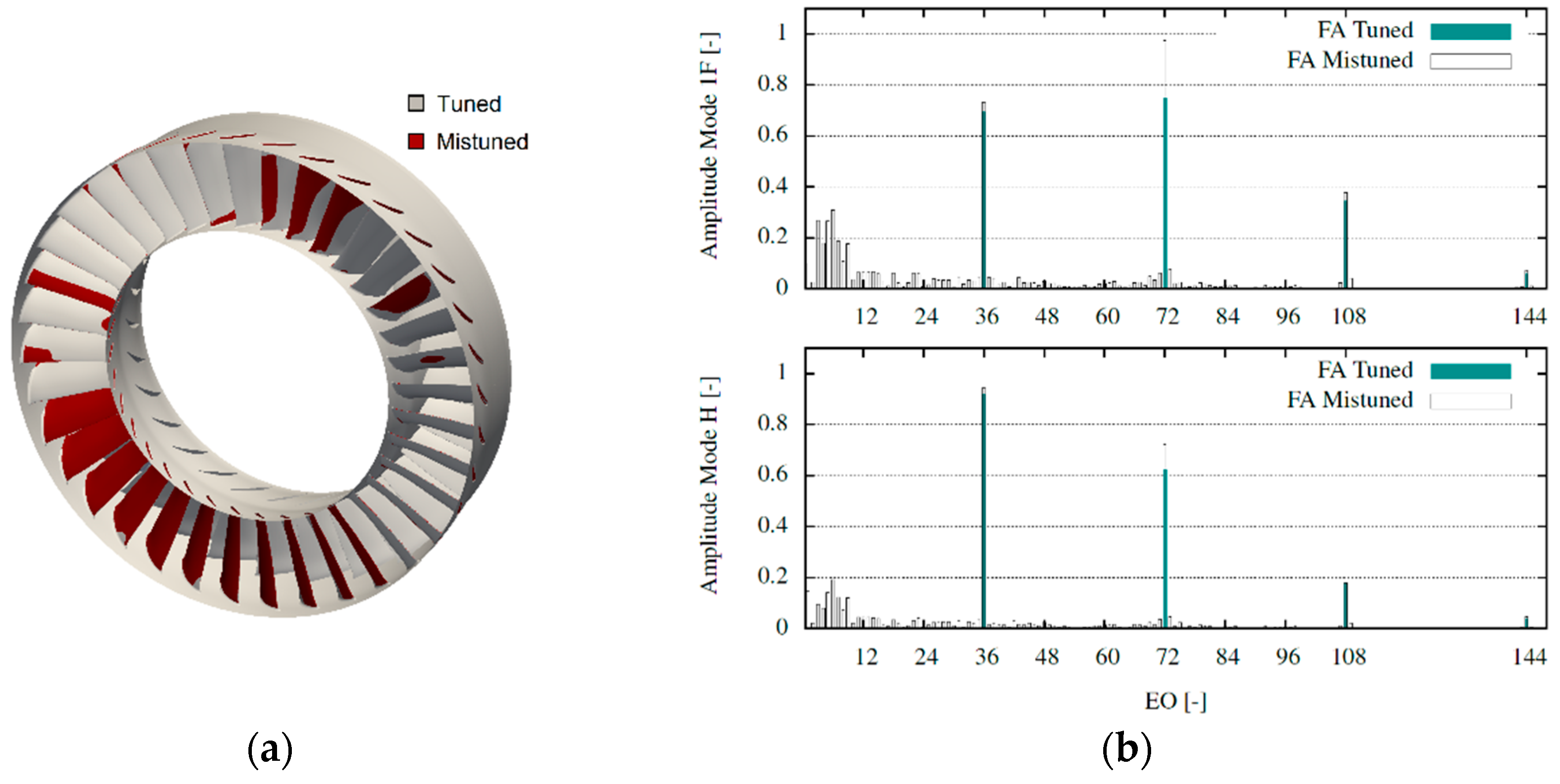

The FA modal forcing predicted from the mixture of MPMR solutions could therefore be analysed in terms of its spectrum. The resulting forcing prediction is computed for the mistuned configuration presented in

Figure 5a. The computed FA CFD solution can therefore be compared with the prediction using the MPMR mixtures. The normalized spectra for the two solution methods are presented in

Figure 6b for the two investigated vibration modes.

The results show an overall good prediction of the excitation harmonics, but the LEO are not captured. The harmonic relative to the vane count of the upstream stator (EO 36) and its upper harmonics are correctly predicted. These are also amplified by the mistuning (see

Figure 5b) and the mixture can represent correctly the amplification. On the other side, the introduced lower harmonics are not represented by the method. It can therefore be concluded that the mixture correctly represents the local deviations, but these are insufficient to represent the lower excitation harmonics.

3.2. MPMR Forcing Superposition

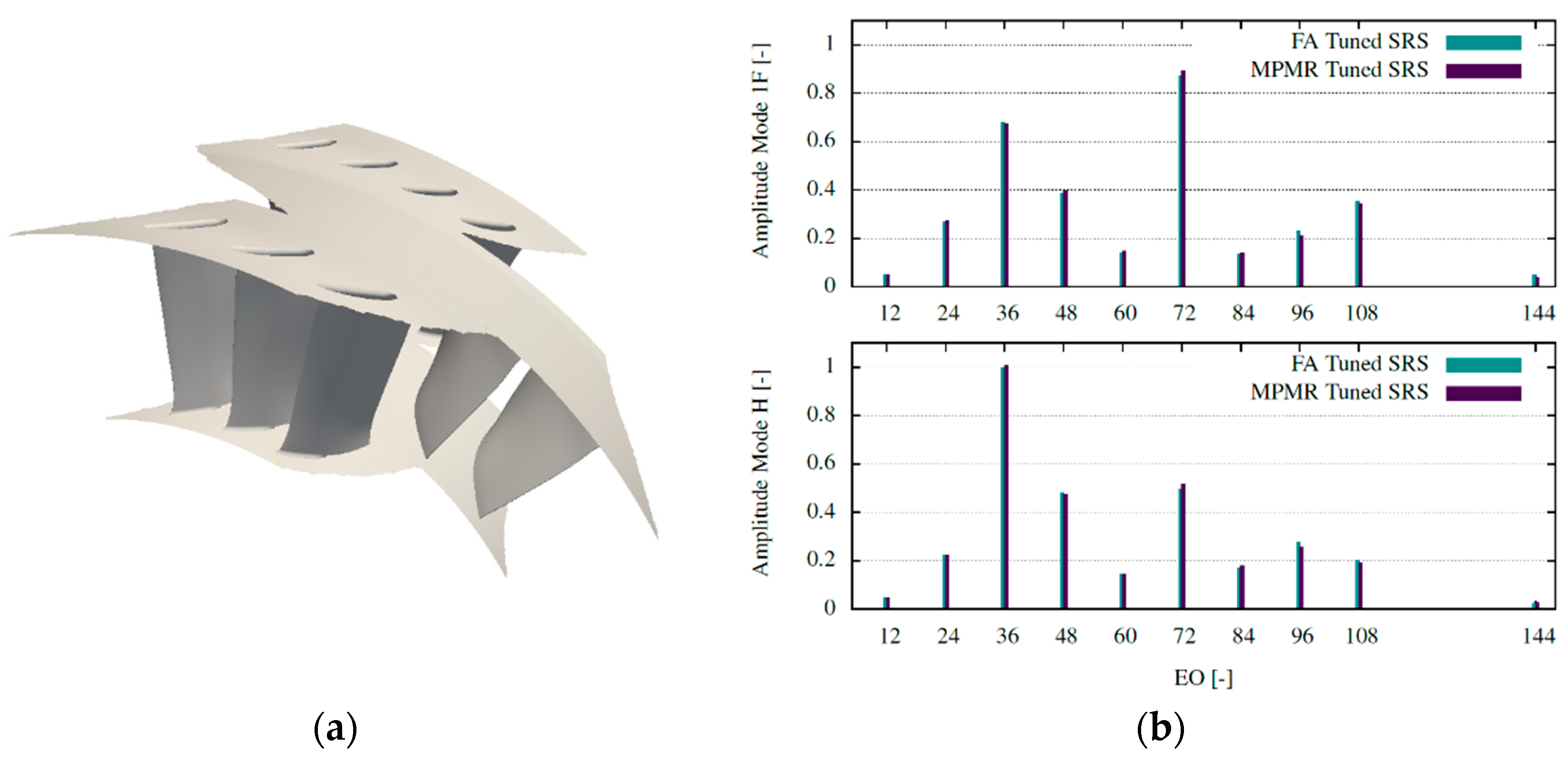

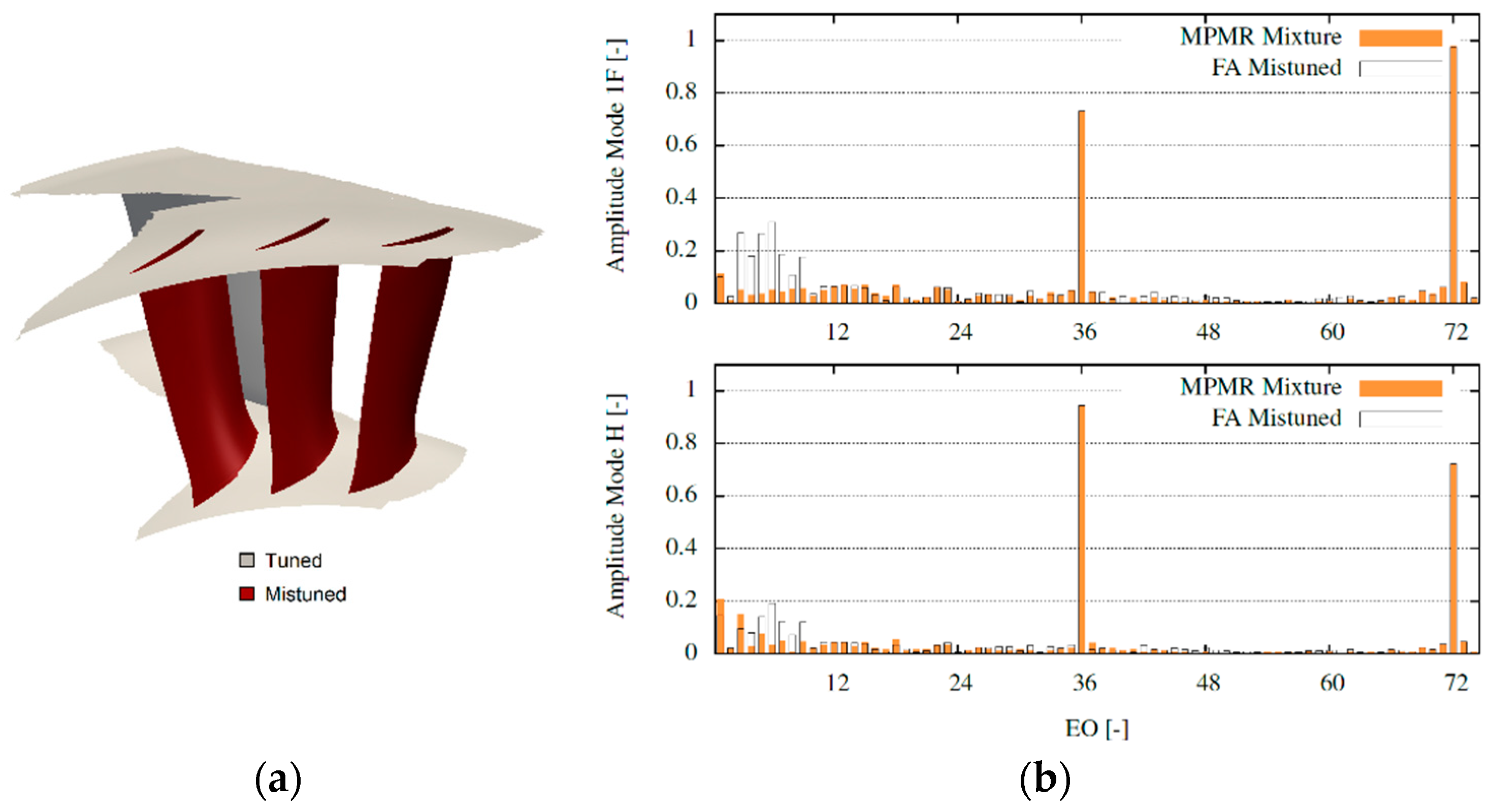

The proposed second and final method aims to represent a larger domain in the CFD to capture also the LEO introduced by the mistuning. The reduced CFD setup in this case included six passages of the stator in a single sector. A single passage of the rotor is still added, as for this row the nominal geometry is used. In

Figure 7a the represented CFD domain is shown.

In this case, a single stator vane in the sector included the geometrical deviations. Further aerofoils are described with the nominal geometry of the vane. This allows to represent individually the disturbances due to the single mistuned geometry, namely the unit responses. Moreover, the geometrical deviations of a single aerofoil per simulation would need to be considered in a probabilistic study. As presented by Figaschewsky et al. [

19] for differences in pitch angle, unit responses computed in a FA setup could be superimposed to represent the total mistuned system. It is of interest here to consider complex three-dimensional deviations of the geometry. Moreover, in order to reduce the computational time, the method is redefined to be adapted to the sector CFD setup.

As a result of each simulation, a forcing function on the R2 blade is calculated. The subscripts indicate the VSV1 single blade with applied geometrical variability in the sector and the R2 vibration mode considered. The superscript indicates that these solutions are computed using the CFD setup for the superposition method here presented.

The FA forcing prediction is computed as a superposition of the MPMR unit responses, using the definitions in Equations (10) to (13). We indicate with N the number of total assembly vanes (N = 36 for VSV1). Being as previously the time required for a revolution, represents a vane passing time interval. Also for the MPMR solutions, the wake of the assembly mistuned vane is identified with a minimum of the EO 36 in the nominal forcing function. This is used to define the time step .

In the MPMR stator vanes sector airfoils are included (here ). This imposes an artificial periodicity to the sector geometry. In particular the solution is representative of blades over the full annulus with applied the same geometrical disturbances, evenly spaced over the circumference. Therefore a period is imposed to the MPMR solutions.

A mean force

is defined from the MPMR solutions. As the

are discrete and periodic, a discrete Fourier transform (DFT) can be applied. The mean force is computed averaging over all the

MPMR solutions only the harmonics which are multiples of

, as these represent the vane passing frequency. The

is computed with the inverse transform to the time domain. This allows to define a forcing disturbance function

for all the MPMR solutions. A filter

is applied to the disturbances, considering a fixed filter window

:

The mean force can be considered periodic. The disturbance for the individual vanes has to be limited in the respective sector. The periodicity of the disturbances, having period length equal , is artificially introduced by the cyclic symmetric boundary. Therefore, only one period per vane has to be used for the superposition. In doing this, the filter ensures continuity to the individual noise terms. The local disturbances have to be expanded to a respective FA disturbance, taking in consideration the respective blade position.

We define the FA disturbance

for each blade

over one shaft revolution as follows. The

values are considered over one period

. The disturbance introduced by each vane is considered null outside the period

for the rest of the revolution. An appropriate phase shift is added to account for the blade

position in the assembly. The FA disturbances are periodic and described over one

period:

The FA forcing prediction

is formulated as follows, superimposing the MPMR unit responses. It is defined as a superposition of the average extracted forcing

and the individual

disturbances for all the vanes:

The FA modal forcing predicted from the MPMR superposition can be analysed in terms of its spectrum. The resulting forcing prediction is computed for the mistuned configuration presented in

Figure 5a, using an according vanes order and phase shift. The computed FA CFD solution is compared with the prediction. The normalized spectra for the two solutions are presented in

Figure 7b for the two investigated vibration modes.

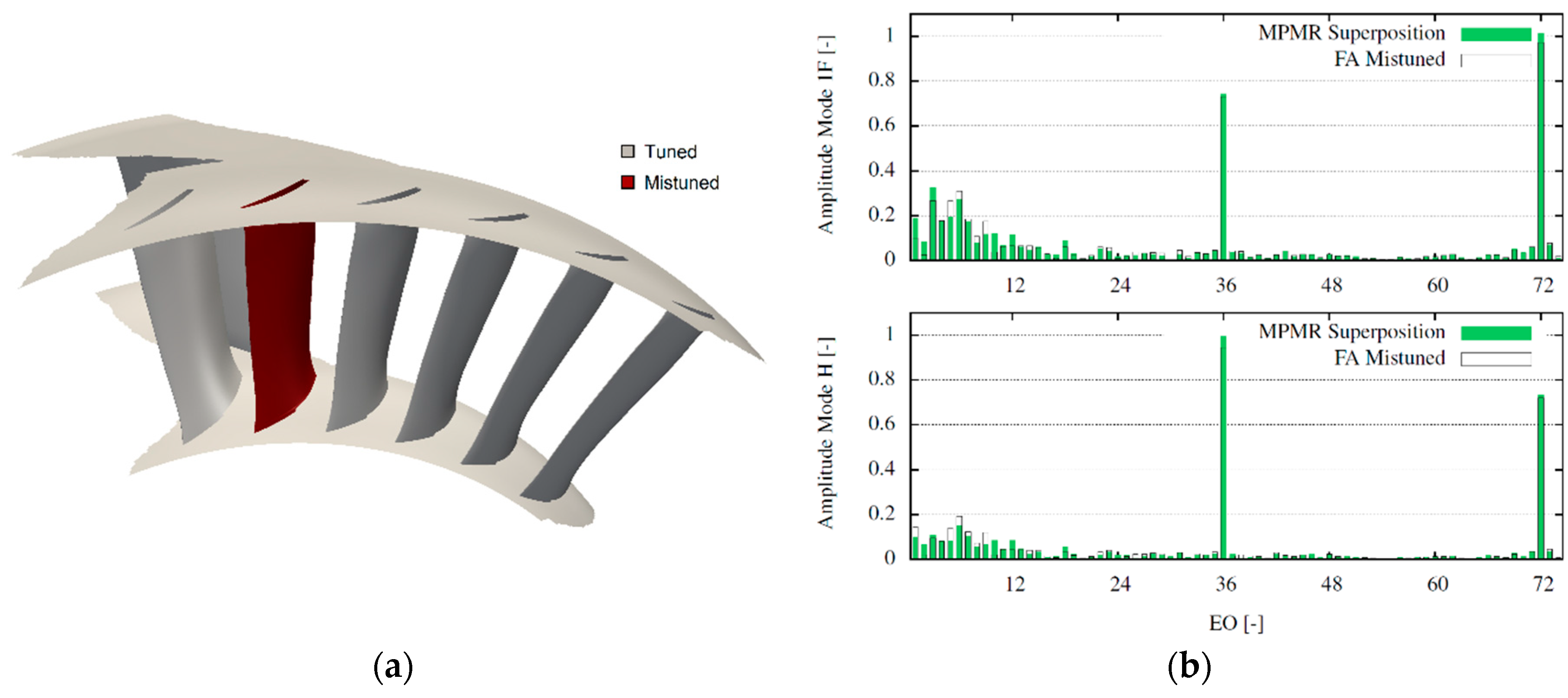

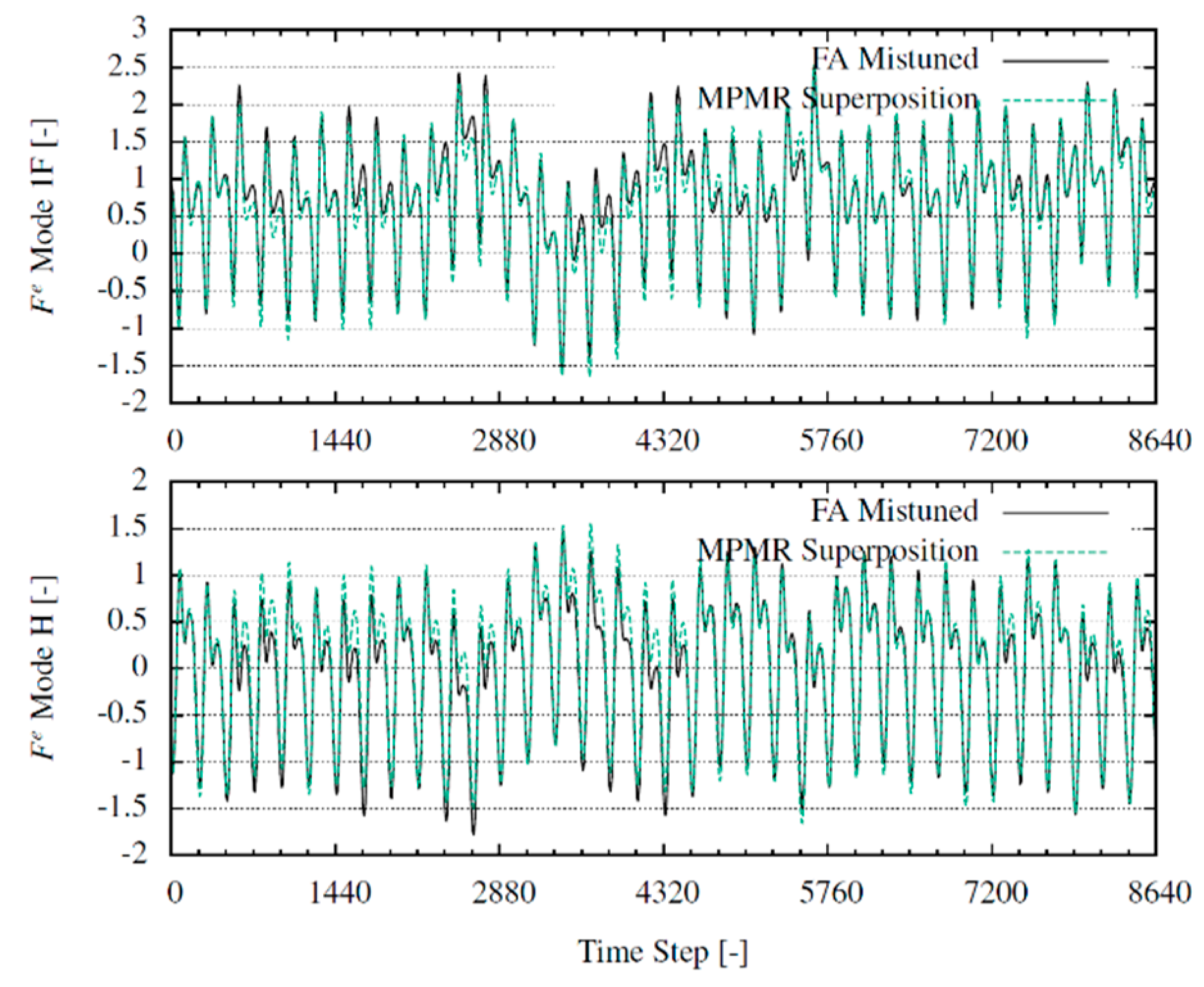

The results show that the method can capture the full spectra of the excitation forces for the two vibration modes. The amplification of the vane passing frequency (EO 36) and its higher harmonics are captured as well as the introduced LEO. It is possible though to see a certain prediction inaccuracy with regard to some of these harmonics amplitude. To verify that the model is representative of the aerodynamic mistuning, in

Figure 8 the excitation forces

are plotted in the time domain. The forces are normalized such as the nominal excitation would oscillate between 1 and -1. It is possible here to compare the results computed with the FA CFD and the MPMR superposition. A period of length

is represented, coinciding with one full shaft revolution. The prediction is shown here to be capable of capturing the physics of the problem correctly.

The loss in accuracy is judged to be caused by an insufficient number of vanes included in the VSV1 sector. The sector in the example represents of the full annulus. Hence, the cyclic symmetry imposed to reduced the CFD domain may be the cause of the inaccuracy. The only set parameter of the method is the filter window , which does not influence significantly the final result. In addition, small changes in the identification of the geometrically mistuned vane wake seem not to affect relevantly the result.

To investigate the influence of the stator sector size on the superposition result, the study was repeated with a larger number

of stator blades. A total of

blades are included in the new setup, equivalent to

of the FA for this specific geometry. The resulting MPMR domain for the calculation of the unit responses is shown in

Figure 9a. In

Figure 9b the resulting rotor forcing superposition for the investigated mistuning pattern is compared with the FA CFD. The results show an increased accuracy in the prediction of the LEO, compared to the

case in

Figure 7b. However, a larger error is observed in the prediction of the EO 36 and 72. This is attributed to the inclusion in the MPMR of several stator blades with the nominal geometry. These EOs showed to be affected by the mistuning (see

Figure 5b). To address this issue in future studies, a mean geometry of the measured aerofoils can be defined to replace the nominal aerofoils in the MPMR unit responses computation. This can give a better representation of the mean flow and therefore a higher accuracy of the reconstruction. This is supported by the high accuracy in the prediction of those harmonics in the “MPMR Forcing Mixture” method.

The results indicate that the problem can be considered linear, even when considering a set of real mistuned stator geometries assembled in an arbitrary order. The disturbances introduced by the individual real stator aerofoils on the flow with respect to the nominal tuned system can be linearly superimposed to represent the assembly. This reduces the problem of modelling this type of flow mistuning to the modelling of the disturbances caused by individual stators. The variability space can therefore be limited to the characterisation of the single aerofoil. Moreover, the CFD domain can be reduced to a sector representation of the stages.

To investigate a different ordering of the stator vanes with this method, it would be sufficient to change the different vanes relative phase. Therefore, having available a set of MPMR solutions, any permutation of those vanes in a FA setup can be solved algebraically.