Submitted:

07 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Growth and Development Characteristics

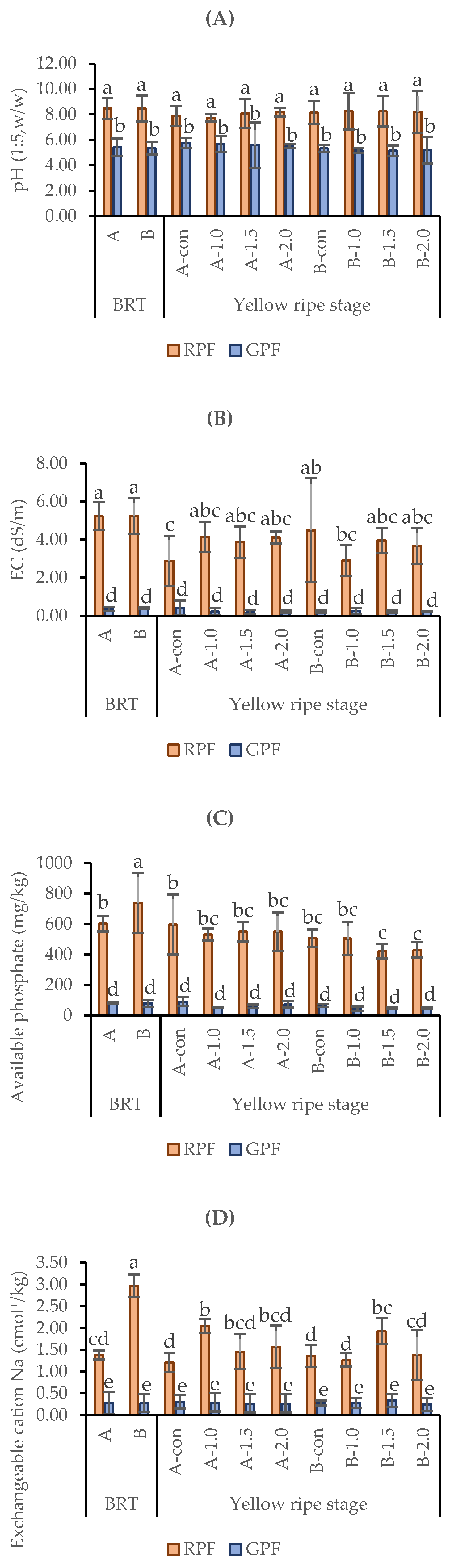

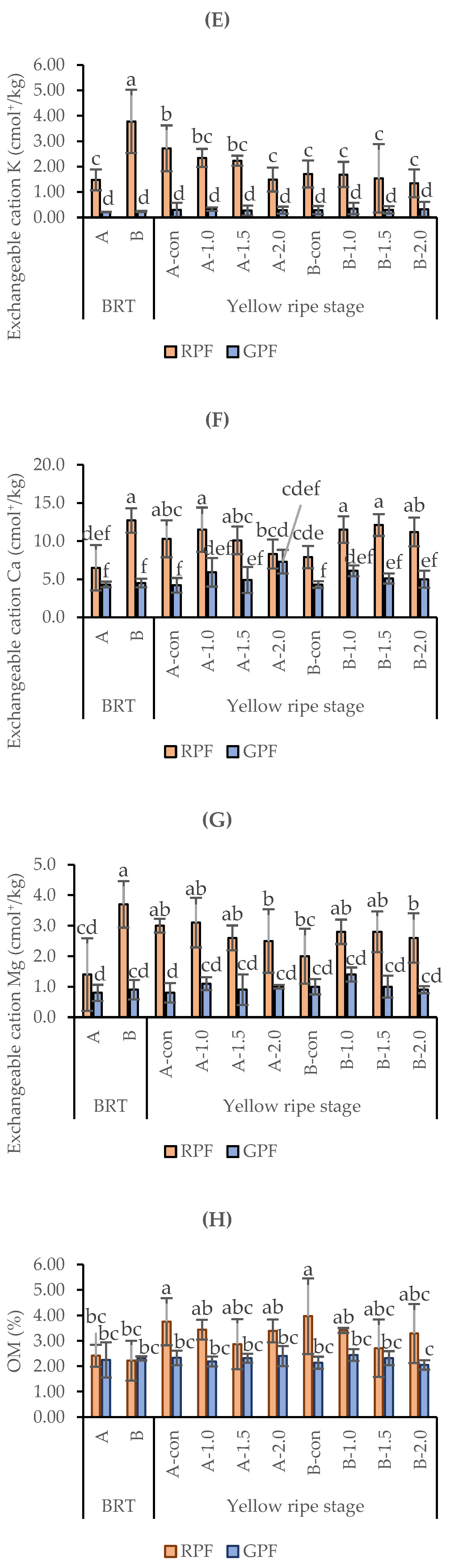

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.3. Yield

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental design

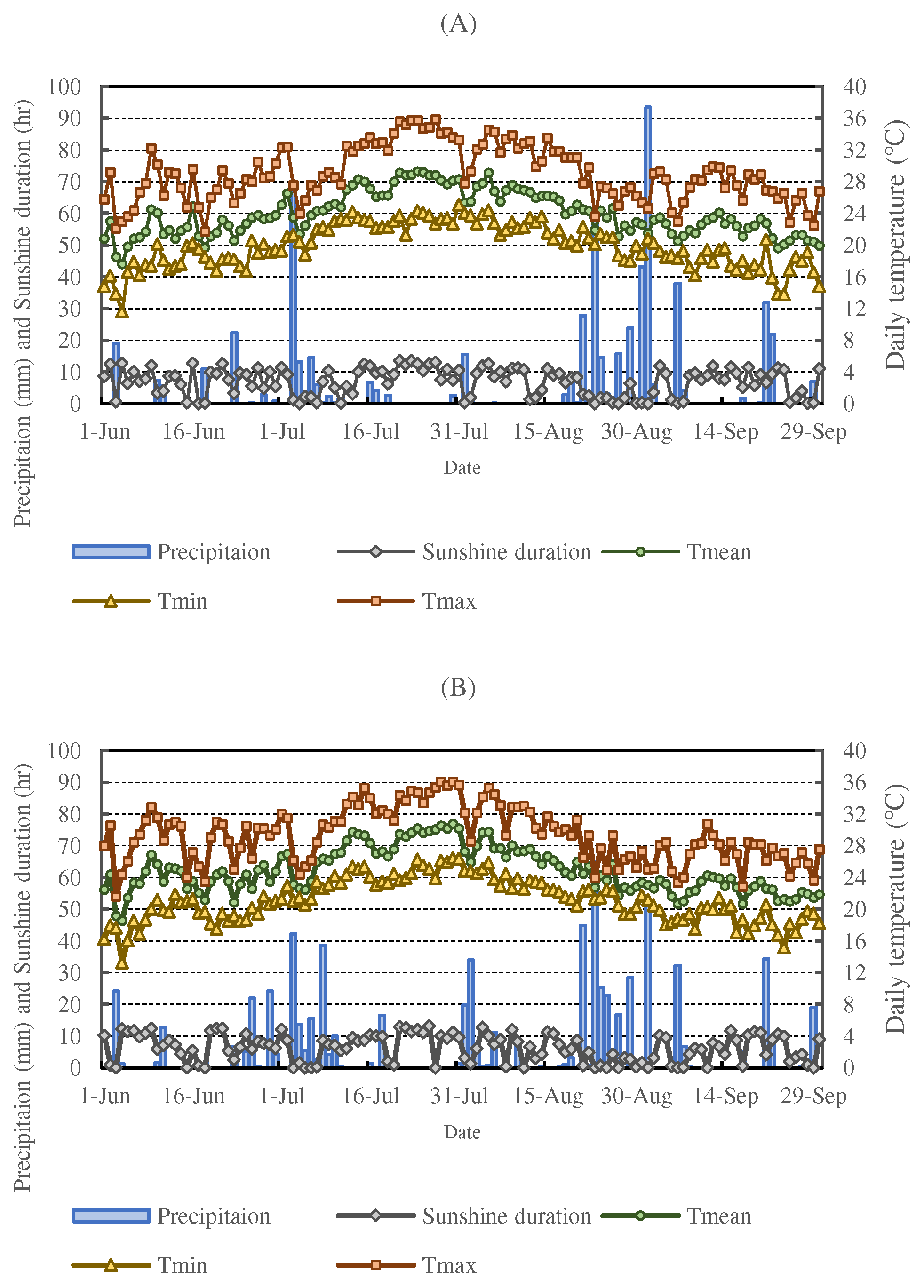

4.2. Weather and Respective Field Conditions

4.3. Measurement of Growth Characteristics of Rice

4.4. Chemical analysis for forage quality

[DDM (%) = 88.9-(ADF(%) × 0.779, DMI(%) = 120/NDF(%)]

4.5. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Linquist, B.A.; Phengsouvanna, V.; Sengxue, P. Benefits of organic residues and chemical fertilizer to productivity of rain-fed lowland rice and to soil nutrient balances. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2007, 79, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhout, B.; Bouwman, A.F.; van Zeijts, H. The role of nitrogen in world food production and environmental sustainability. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 116, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Wei, G.; Li, Z. Beneficial bacteria activate nutrients and promote wheat growth under conditions of reduced fertilizer application. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Effect and Mechanism of Rice-Pasture Rotation Systems on Yield Increase and Runoff Reduction under Different Fertilizer Treatments. Agronomy 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant. Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.A.; Sarkhosh, A.; Khan, N.; Balal, R.M.; Ali, S.; Rossi, L.; Gómez, C.; Mattson, N.; Nasim, W.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Insights into the physiological and biochemical impacts of salt stress on plant growth and development. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Irfan, M.D.; Ahmad, A.; Hayat, S. Causes of salinity and plant manifestations to salt stress: A review. J. Environ. Biol. 2011, 32, 667–685. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, B.Y.; Chang, W.K.; Hong, S.; Song, S.J.; Park, J.; Kwon, B.O.; Khim, J.S. Environmental and ecological effects of Lake Shihwa reclamation project in South Korea: A review. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, K.; Lee, M.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, W.J.; Park, J.G.; Yang, J. sam Enhanced benthic nutrient flux during monsoon periods in a coastal lake formed by tideland reclamation. Estuaries and Coasts 2009, 32, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G. The evolution of coastal wetland policy in developed countries and Korea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.H.; Beon, M.S.; Jeong, J.C. Dynamics of soil salinity and vegetation in a reclaimed area in Saemangeum, Republic of Korea. Geoderma 2018, 321, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R. Modernization, Development and Underdevelopment: Reclamation of Korean tidal flats, 1950s-2000s. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Harris, P.J.C. Potential biochemical indicators of salinity tolerance in plants. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Sharavdorj, K.; Nadalin, P.; Lee, S.; Cho, J. Growth and Forage Value of Two Forage Rice Cultivars According to Harvest Time in Reclaimed Land of South Korea. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y.-M.; Jeon, G.-Y.; Song, J.-D.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, M.-E. Effect of soil salinity variation on the growth of barley, rye and oat seeded at the newly reclaimed tidal lands in Korea. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2009, 42, 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Bae, H.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Kang, J.-G.; Kim, H.-K.; Lee, K.-B.; Park, K.-H. Effect of Soil Salinity Levels on Silage Barley Growth at Saemangeum Reclaimed Tidal Land. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2013, 46, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.B. The effects of forage policy on feed costs in Korea. Agric. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.-M.; Shin, K.-S.; Hwang, W.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, C.-H. Nutrient Value and Yield Response of Forage Crop Cultivated in Reclaimed Tidal Land Soil Using Anaerobic Liquid Fertilizer. Korean J. Org. Agric. 2012, 20, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.-B.; Park, T.-S.; Park, H.-K.; Kim, H.-S.; Choi, I.-B.; Bae, H.-S. Effect of Seeding and Nitrogen rates on the Growth characters, Forage yield, and Feed value of Barnyard millet in the Reclaimed tidal land. Weed Turfgrass Sci. 2017, 6, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.Y.; Son, J.G.; Choi, J.K.; Song, C.H.; Chung, B.Y. Surface and subsurface losses of N and P from salt-affected rice paddy fields of Saemangeum reclaimed land in South Korea. Paddy Water Environ. 2008, 6, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.T.; Berdanier, A.B.; Grace, P.R. Patterns and trends in nitrogen use and nitrogen recovery efficiency in world agriculture. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2013, 27, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; De Vries, W.; Bonten, L.T.C.; Zhu, Q.; Hao, T.; Liu, X.; Xu, M.; Shi, X.; Zhang, F.; Shen, J. Model-Based Analysis of the Long-Term Effects of Fertilization Management on Cropland Soil Acidification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3843–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Shi, J.; Zeng, L.; Xu, J.; Wu, L. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on the acidity and salinity of greenhouse soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 2976–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemati Matin, N.; Jalali, M. The effect of waterlogging on electrochemical properties and soluble nutrients in paddy soils. Paddy Water Environ. 2017, 15, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, R. Ferrolysis, a hydromorphic soil forming process. Geoderma 1970, 3, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balemi, T.; Negisho, K. Management of soil phosphorus and plant adaptation mechanisms to phosphorus stress for sustainable crop production: A review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 12, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Suarez, D.L. Interactive effects of pH, EC and nitrogen on yields and nutrient absorption of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 194, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, H.; Dukes, J.S. Effects of warming and altered precipitation on plant and nutrient dynamics of a New England salt marsh. Ecol. Appl. 2009, 19, 1758–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, H.E.; Angell, J.H.; Fulweiler, R.W. Salt Marsh Greenhouse Gas Fluxes and Microbial Communities Are Not Sensitive to the First Year of Precipitation Change. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2019, 124, 1071–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengasamy, P.; De Lacerda, C.F.; Gheyi, H.R. Salinity, Sodicity and Alkalinity. Subsoil Constraints Crop Prod. 2022, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvanitha, S.; Mahendran, S. Effect of salinity on plant height, shoot and root dry weight of selected rice cultivars. Sch. J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq, A.; Ali, A.; Safdar, L. Bin; Zafar, M.M.; Rui, Y.; Shakeel, A.; Shaukat, A.; Ashraf, M.; Gong, W.; Yuan, Y. Salt stress induces physiochemical alterations in rice grain composition and quality. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, T.; Lu, J.; Ming, R.; Li, P.; Hussain, S.; Cong, R.; Li, X. Heterogeneity in rice tillers yield associated with tillers formation and nitrogen fertilizer. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsiddig, A.M.I.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, G.; Nimir, N.E.A.; Suliman, M.S.E.; Ibrahim, M.E.H.; Ali, A.Y.A. Nitrogen fertilizer promoting salt tolerance of two sorghum varieties under different salt compositions. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2023, 83, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Morita, S.; Kitagawa, H.; Wada, H.; Takahashi, M. Grain Yield Response to Planting Density in Forage Rice with a Large Number of Spikelets. Crop Sci. 2012, 52, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setter, T.L.; Laureles, E. V.; Mazaredo, A.M. Lodging reduces yield of rice by self-shading and reductions in canopy photosynthesis. F. Crop. Res. 1997, 49, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Hou, Z.; Wu, L.; Liang, Y.; Wei, C. Effects of salinity and nitrogen on cotton growth in arid environment. Plant Soil 2010, 326, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Bhattacharya, A.K.; Nair, T.V.R.; Singh, A.K. Nitrogen loss through subsurface drainage effluent in coastal rice field from India. Agric. Water Manag. 2002, 52, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Castorena, M.; Ulery, A.L.; Catalán-Valencia, E.A.; Remmenga, M.D. Salinity and Nitrogen Rate Effects on the Growth and Yield of Chile Pepper Plants. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.E.H.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, G.; Ali, A.Y.A.; Ahmad, I.; Elsiddig, A.M.I. Nitrogen fertilizer reduces the impact of sodium chloride on wheat yield. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.E.P.; Zocchi, S.S.; Baron, D. Reconciling the Mitscherlich’s law of diminishing returns with Liebig’s law of the minimum. Some results on crop modeling. Math. Biosci. 2017, 293, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ge, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Xu, K.; Wei, H.; Dai, Q. Improved physiological and morphological traits of root synergistically enhanced salinity tolerance in rice under appropriate nitrogen application rate. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajighasemi, S.; Keshavarz-Afshar, R.; Chaichi, M.R. Nitrogen fertilizer and seeding rate influence on grain and forage yield of dual-purpose barley. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-B.; Yang, C.-I.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Shin, Y.-S.; Lee, K.-S.; Choi, Y.-H.; Jeong, O.-Y.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Hong, H.-C.; et al. A Late-Maturing and Whole Crop Silage Rice Cultivar “Mogwoo. ” J. Korean Soc. Grassl. Forage Sci. 2013, 33, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudduth, K.A.; Kitchen, N.R.; Wiebold, W.J.; Batchelor, W.D.; Bollero, G.A.; Bullock, D.G.; Clay, D.E.; Palm, H.L.; Pierce, F.J.; Schuler, R.T.; et al. Relating apparent electrical conductivity to soil properties across the north-central USA. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Planting density | Fertilizer | Tiller number | Productive tiller | Plant height | Culm length | SPAD | LAI(m2) | Lodging | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flag leaf | Third leaf | ||||||||||

| (No./m2) | (cm) | 0-100% | |||||||||

| RPF | 16 | ||||||||||

| Control | 193.6f | 127.6f | 160.0cd | 106.6c | 44.9abc | 44.2ab | 2.7e | 0 | |||

| 1.0 | 255.2ef | 233.2ef | 180.7a | 120.9abc | 44.4abc | 43.4ab | 3.2cde | 0 | |||

| 1.5 | 321.2cdef | 167.2cdef | 172.2abc | 115.5abc | 44.8abc | 46.8a | 4.8bcd | 10 | |||

| 2.0 | 294.8def | 286.0def | 168.5abc | 116.3abc | 40.6c | 43.5ab | 2.3e | 80 | |||

| 10 | |||||||||||

| control | 310.2cdef | 303.6cdef | 159.8cd | 112.6bc | 45.6abc | 44.1ab | 2.5e | 0 | |||

| 1.0 | 455.4ab | 415.8ab | 177.0ab | 120.5abc | 46.8abc | 43.3ab | 4.7bcd | 10 | |||

| 1.5 | 488.4a | 468.6a | 171.0abc | 119.3abc | 43.6abc | 43.5ab | 4.9bcd | 20 | |||

| 2.0 | 429.0abc | 409.2abc | 181.1a | 129.8a | 43.8abc | 46.6a | 3.8cde | 90 | |||

| GPF | 16 | ||||||||||

| Control | 238.3ef | 231.0ef | 148.0de | 112.2bc | 31.3d | 27.3d | 2.9de | 0 | |||

| 1.0 | 245.7ef | 238.3ef | 164.9bc | 123.0ab | 41.7bc | 38.0bc | 3.5cde | 0 | |||

| 1.5 | 348.3bcde | 341.0bcde | 167.0abc | 118.7abc | 47.3ab | 43.4ab | 5.2bc | 10 | |||

| 2.0 | 264.0ef | 223.7ef | 171.1abc | 114.0bc | 46.5abc | 41.1abc | 4.2cde | 30 | |||

| 10 | |||||||||||

| Control | 401.5abcd | 401.5abcd | 139.5e | 107.0c | 33.2d | 33.9cd | 4.9bcd | 0 | |||

| 1.0 | 500.5a | 489.5a | 166.4abc | 123.6ab | 44.7abc | 38.0bc | 6.5b | 0 | |||

| 1.5 | 495.0a | 484.0a | 168.3abc | 117.4abc | 48.9a | 40.6abc | 9.3a | 20 | |||

| 2.0 | 506.0a | 500.5a | 158.7cd | 111.5bc | 44.5abc | 42.2ab | 9.6a | 70 | |||

| CV (%) | 21.5 | 23.8 | 5.5 | 7.2 | 8.3 | 11.4 | 26.6 | - | |||

| Lovation (L) | NS | ** | *** | NS | * | *** | *** | - | |||

| Planting density and Fertilizer (P) | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | NS | *** | - | |||

| LⅹP | NS | NS | NS | NS | *** | NS | *** | - | |||

| Location | Planting density | Fertilizer | CP | NDF | ADF | TDN | Hemicellulose | RFV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | ||||||||

| RPF | 16 | |||||||

| control | 9.7bcd | 59.7d | 37.0abcd | 59.7abcde | 22.7abc | 94bc | ||

| 1.0 | 8.3cde | 61.2d | 36.1abcd | 60.4abcde | 25.1ab | 92bc | ||

| 1.5 | 9.7bcd | 62.1d | 37.8bcd | 59.0bcde | 24.2abc | 89bc | ||

| 2.0 | 9.9bc | 63.1d | 36.1abcd | 60.4abcde | 27.0a | 90bc | ||

| 10 | ||||||||

| Control | 7.3ef | 57.4d | 36.2abcd | 60.3abcde | 21.2abc | 98bc | ||

| 1.0 | 10.0b | 60.5d | 36.4abcd | 60.1abcde | 24.0abc | 93bc | ||

| 1.5 | 8.1de | 62.5d | 37.5bcd | 59.3bcde | 25.0ab | 89bc | ||

| 2.0 | 10.6ab | 61.9d | 41.0d | 56.5de | 20.9abc | 86bc | ||

| GPF | 16 | |||||||

| Control | 4.9g | 53.9bcd | 36.4abcd | 60.2abcde | 17.6abc | 104a | ||

| 1.0 | 6.2fg | 59.1d | 35.5abcd | 60.8abcde | 23.6abc | 96bc | ||

| 1.5 | 10.6ab | 63.4d | 39.7cd | 57.6cde | 23.7abc | 85bc | ||

| 2.0 | 11.7a | 55.2cd | 31.8abc | 63.8abc | 23.4abc | 108a | ||

| 10 | ||||||||

| control | 5.6g | 46.6abc | 30.4ab | 64.9ab | 16.2bc | 130a | ||

| 1.0 | 9.3bcd | 45.9ab | 32.0abc | 63.6abcd | 13.9c | 130a | ||

| 1.5 | 8.3cde | 43.4a | 28.2a | 66.6a | 15.2bc | 144a | ||

| 2.0 | 10.9ab | 63.6 | 43.2d | 54.7e | 20.3abc | 81c | ||

| CV (%) | 10.0 | 8.7 | 12.6 | 5.9 | 25.3 | 11.7 | ||

| Lovation (L) | ** | *** | NS | NS | ** | *** | ||

| Planting density and Fertilizer (P) | *** | ** | * | * | NS | *** | ||

| LⅹP | *** | ** | NS | NS | NS | *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).