1. Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are laboratory-produced molecules that mimic the immune system’s ability to fight off harmful pathogens. mAbs designated to target specific proteins on the surface of cells, which are considered as powerful tools for diagnosing and treating diseases such as autoimmune disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases [

1].

The history of mAbs dates back to the 1970s when scientists discovered that they could produce hybrid cells by fusing a cancerous B cell with an antibody-producing cell. These hybrid cells, known as hybridomas, could produce large quantities of identical antibodies that target a specific antigen [

2].

The first monoclonal antibody was produced in 1975 by César Milstein and Georges Köhler at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England. They used hybridoma technology to create an antibody that targeted sheep red blood cells [

3].

However, researchers developed new techniques for producing mAbs and began using them for a variety of applications. In 1986, the first therapeutic mAb was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of transplant rejection. Since then, mAbs have become an important class of drugs for treating cancer and autoimmune disorders. They work by targeting specific proteins on the surface of cancer cells or immune cells, blocking their activity and preventing them from causing damage [

4].

One of the most prominent examples of a therapeutic mAb is Herceptin (trastuzumab), which was approved by the FDA in 1998 for the treatment of breast cancer. Herceptin targets a protein called HER2/neu that is overexpressed in some types of breast cancer cells [

5].

The process of creating monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) involves isolating and cloning a single type of immune cell (a B cell) that produces a specific antibody. These B cells are then fused with cancer cells to create hybridoma cells that can produce large quantities of identical antibodies [

6].

Monoclonal antibody therapy has become an important tool in treating many diseases, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases. One of the key advantages of this type of therapy is its specificity—monoclonal antibodies can be designed to target only the cells or proteins that are causing the disease while leaving healthy cells unharmed [

7].

Monoclonal antibodies have emerged as a promising antiviral therapy in recent years by being designed to specifically target and neutralize a particular virus, preventing its entry into host cells and halting its replication [

8]. Monoclonal antibody therapy has shown great potential in treating various viral infections, including COVID-19, by reducing the severity of symptoms and improving patient outcomes. This innovative approach offers a targeted and effective strategy to combat viral diseases and holds great promise for the future of antiviral therapy.

The use of mAbs has been successful in treating various diseases such as cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases like COVID-19. However, recent studies have shown that some pathogens can develop resistance to monoclonal antibody therapy [

9].

The emergence of variant resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy can be attributed to several factors. One factor is the genetic variability of viruses. Viruses can mutate and evolve rapidly, leading to changes in their surface molecules targeted by monoclonal antibodies [

10].

Another factor is the selective pressure exerted by monoclonal antibody therapy on viruses. As more patients receive this treatment, there is an increased likelihood that some viruses will develop resistance over time [

11].

To address this issue, researchers are exploring new strategies for developing more effective mAbs that can overcome variant resistance. One approach is to design antibodies that target multiple surface molecules on the virus rather than just one. This would make it harder for the virus to develop resistance since it would need to mutate multiple molecules simultaneously [

12].

Another approach is to combine different types of mAbs with different mechanisms of action. This would increase the likelihood of effectively targeting a virus even if it develops resistance to one type of antibody [

13].

This mini-review highlights the importance of understanding the underlying mechanisms of resistance and designing new therapeutic approaches that can target these mechanisms. Various strategies such as combination therapy, bispecific antibodies, and engineered antibodies are discussed in detail. The article also emphasizes the need for continued research in this area to develop more effective therapies that can overcome resistance and improve patient outcomes.

2. Mechanisms of variants resistance in monoclonal antibodies therapy

Genetic mutations in viral proteins and the development of monoclonal antibodies for antiviral therapy are two interrelated aspects of combating viral infections. The interplay between these mutations and antibodies highlights the ever-changing nature of antiviral treatment [

14]. Scientists must adjust monoclonal antibody formulations to accommodate viral mutations, and the selection of antibodies may depend on the prevalence of specific variants. In some cases, a combination of multiple antibodies with different targets is used to minimize treatment resistance.

Viral infections, like SARS-CoV-2, often result in the formation of a diverse group of viral variants within the human body. This occurs due to the error-prone nature of viral replication. Consequently, there is a constant worry that therapeutic interventions may inadvertently favor the emergence of resistant strains. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which target specific regions on the surface of the virus, recognize only one epitope each. In individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those who are immunocompromised, the initial viral load tends to be higher, and the clearance of the virus is often delayed. This combination of factors creates a challenging situation where treatment-resistant viral strains are more likely to develop [

14].

The presence of a quasi-species swarm, coupled with the limited recognition capability of mAbs and the compromised immune response in certain individuals, provides an ideal environment for the selection and proliferation of resistance mutations. These mutations can render the virus less susceptible to the effects of the monoclonal antibody treatment. Consequently, the development of treatment-emergent resistance becomes a significant concern in managing viral infections, especially in immunocompromised patients with high viral loads [

15].

Understanding the genetic mutations in viral proteins is crucial for developing effective monoclonal antibody-based antiviral therapies. However, the effectiveness of these therapies relies on continuous monitoring of viral mutations and the ability to tailor treatments accordingly [

15].

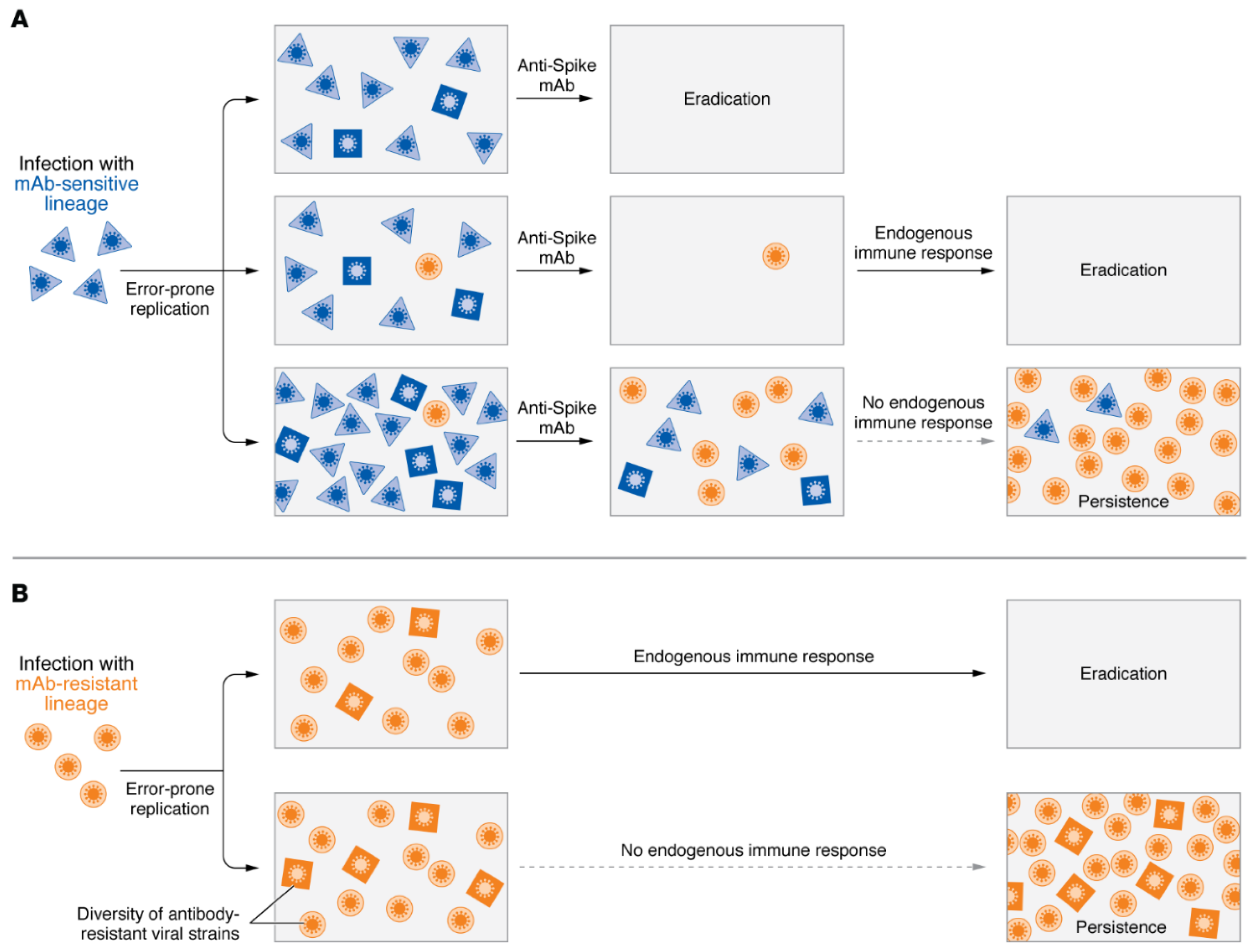

Figure 1.

The administration of mAb therapies during SARS-CoV-2 infection promotes the selection of escape variants. (A) Following mAb therapy, SARS-CoV-2 infection may yield different results when exposed to susceptible viral strains (represented by blue squares and diamonds), including the emergence of strains that are resistant to antibodies (depicted as orange circles). (B) Infection with a virus that cannot be neutralized by mAb (depicted as orange circles) can further diversify viral strains (depicted as orange squares and diamonds), resulting in the development of strains capable of evading vaccine-induced immunity and initiating subsequent waves of infection within the population.

Figure 1.

The administration of mAb therapies during SARS-CoV-2 infection promotes the selection of escape variants. (A) Following mAb therapy, SARS-CoV-2 infection may yield different results when exposed to susceptible viral strains (represented by blue squares and diamonds), including the emergence of strains that are resistant to antibodies (depicted as orange circles). (B) Infection with a virus that cannot be neutralized by mAb (depicted as orange circles) can further diversify viral strains (depicted as orange squares and diamonds), resulting in the development of strains capable of evading vaccine-induced immunity and initiating subsequent waves of infection within the population.

2.1. Genetic mutations in target antigens

The emergence of variants that are resistant to monoclonal antibody therapy has become a significant challenge in clinical practice. Understanding the mechanisms of variant resistance is crucial for developing effective strategies to overcome this problem [

4].

One of the mechanisms of variant resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy is genetic mutations in target antigens. Genetic mutations can alter the structure or expression level of target antigens, making them less susceptible to monoclonal antibodies [

16].

2.2. Epitope masking

Another mechanism of variant resistance is epitope masking or conformational changes. Epitope masking occurs when a variant antigen undergoes structural changes that prevent monoclonal antibodies from binding to their target epitopes [

17]. This can happen due to post-translational modifications or protein-protein interactions that alter the conformation of the antigen. For example, in HIV therapy, variants that escape neutralization by monoclonal antibodies often have mutations that cause conformational changes in viral envelope glycoproteins.

Conformational changes can also occur due to environmental factors such as PH or temperature. Monoclonal antibodies may lose their binding affinity when exposed to extreme conditions that alter the conformation of their target antigens. This phenomenon has been observed in influenza virus therapy, where variants resistant to monoclonal antibodies have been found to have altered hemagglutinin structures due to exposure to acidic PH [

18].

To overcome variant resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy for viral infections, several strategies have been proposed. One approach is to develop combination therapies that target multiple epitopes or signaling pathways. This can reduce the likelihood of variants escaping therapy by targeting multiple vulnerabilities. Another approach is to engineer monoclonal antibodies with enhanced binding affinity or specificity for their target antigens [

19]. This can be achieved through rational design or directed evolution techniques that optimize the antibody-antigen interaction.

2.3. Increased expression of alternative antigens

Monoclonal antibody therapy has revolutionized the treatment of various diseases, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases. However, the emergence of variants that are resistant to monoclonal antibodies has become a significant challenge in the field of biopharmaceuticals. One of the mechanisms of variant resistance is increased expression of alternative antigens.

mAbs are designed to target specific antigens on the surface of cells or pathogens. They bind to these antigens and trigger immune responses that lead to cell death or clearance of pathogens [

20]. However, some variants can escape this mechanism by increasing the expression of alternative antigens that are not targeted by the mAb.

For example, mAbs are used to neutralize viral particles by binding to specific epitopes on their surface [

21]. However, some viruses can mutate their surface proteins and generate variants that have altered epitopes or new ones altogether. These variants can evade the recognition and binding of mAbs and continue infecting host cells [

22].

The increased expression of alternative antigens is a complex process that involves multiple factors such as genetic mutations, epigenetic modifications, and environmental cues. It can occur through various mechanisms such as gene amplification, transcriptional activation, post-transcriptional regulation, or protein stabilization.

To overcome this mechanism of variant resistance, researchers have developed several strategies such as combination therapy with multiple mAbs targeting different epitopes or pathways; engineering mAbs with higher affinity or broader specificity; using bispecific antibodies that can bind to two antigens simultaneously; or using alternative therapies such as small molecules, immunotherapies, or gene therapies.

3. Strategies for overcoming variants resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy

3.1. Development of bispecific antibodies

The emergence of variants that are resistant to monoclonal antibodies poses a significant challenge to their efficacy. To overcome this challenge, researchers have developed several strategies, including the development of bispecific antibodies and combination therapy with other drugs or antibodies [

23].

Bispecific antibodies are engineered molecules that contain two different binding sites, each specific for a different antigen. This allows them to simultaneously bind to two different targets and exert a more potent therapeutic effect [

24]. In the context of monoclonal antibody therapy, bispecific antibodies can be designed to target both the original antigen and its variants that have emerged due to mutations or other mechanisms [

25].

One strategy for developing bispecific antibodies is to combine two monoclonal antibodies that target different epitopes on the same antigen. This approach has been used successfully in the treatment of cancer, where bispecific antibodies targeting both CD3 (a T-cell receptor) and a tumor-associated antigen have shown promising results in clinical trials. By engaging T-cells and redirecting them towards cancer cells, these bispecific antibodies can induce tumor cell killing even in the presence of variants that are resistant to single-target monoclonal antibodies [

26].

Another approach for developing bispecific antibodies is to engineer them using recombinant DNA technology [

27]. This involves fusing two different antibody fragments into a single molecule that can bind to two different antigens simultaneously. One example of this approach is the development of bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), which are designed to engage T-cells and redirect them toward cancer cells expressing specific antigens. BiTEs have shown remarkable efficacy in preclinical studies and clinical trials for various types of cancer [

28].

In addition to targeting variants directly, bispecific antibodies can also be designed to enhance immune effector functions such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). For example, a bispecific antibody that targets both CD20 (a B-cell antigen) and CD3 has been shown to enhance ADCC and induce potent tumor cell killing in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [

29].

3.2. Conjugated antibodies

Monoclonal antibody therapy, when used in combination with other drugs or antibodies, has shown promising results in the field of antiviral therapy. This approach involves the use of specifically engineered antibodies that target and neutralize specific viral antigens, thereby inhibiting viral replication and spread. By combining monoclonal antibody therapy with other therapeutic agents, such as antiviral drugs, the efficacy of treatment can be enhanced, offering a more comprehensive approach to combating viral infections [

30]. This combination therapy holds great potential in the field of antiviral therapy and is an area of active research and development.

In addition to bispecific antibodies and combination therapy, researchers are also exploring other strategies for overcoming resistance to monoclonal antibody therapy. These include the development of next-generation monoclonal antibodies that can bind more effectively to their targets and the use of immunomodulatory agents that can enhance the immune response against disease-causing cells [

31].

3.3. Development of broad-spectrum antibodies

The development of broad-spectrum antibodies has the potential to provide a versatile and effective treatment option against a wide range of viral infections. By targeting conserved regions of viral proteins, broad-spectrum antibodies can neutralize multiple strains of a virus, reducing the risk of resistance development [

32]. This approach holds promise for the prevention and treatment of emerging viral diseases, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, as well as future outbreaks. Continued advancements in the development and optimization of broad-spectrum antibodies will contribute to the improvement of antiviral therapies and ultimately enhance public health.

3.4. Engineering of antibodies to target multiple epitopes or antigens

The emergence of variants or mutations in the target antigen can lead to resistance to monoclonal antibody therapy. This resistance can limit the efficacy of the treatment and pose a significant challenge for clinicians. Therefore, strategies for overcoming variants resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy are crucial for improving patient outcomes [

33].

One promising strategy is engineering antibodies to target multiple epitopes or antigens [

33]. This approach involves designing antibodies that recognize multiple regions on the target antigen or different antigens altogether. By targeting multiple epitopes or antigens, these engineered antibodies can overcome variants resistance and maintain their efficacy even in the presence of mutations.

There are several ways to engineer antibodies to target multiple epitopes or antigens. One approach is to create bispecific antibodies that bind two different antigens simultaneously. Bispecific antibodies can be designed to recognize two different epitopes on the same antigen or two different antigens altogether. For example, a bispecific antibody targeting both CD3 and CD19 has shown promising results in treating B-cell malignancies [

34].

Another approach is to create multispecific antibodies that recognize three or more antigens simultaneously. Multispecific antibodies can be designed using various formats, including tri-specific antibodies (trispecifics) and tetraspecific antibodies (tetraspecifics). Trispecifics are engineered with three binding domains that recognize three different antigens, while tetraspecifics have four binding domains that recognize four different antigens [

35]. These multispecific antibodies have shown potential in treating complex viral infections and other diseases.

In addition to bispecific and multispecific antibodies, other engineering approaches can also be used to target multiple epitopes or antigens. For example, antibody fragments such as Fab fragments and single-chain variable fragments (scFv) can be combined to create bispecific or multispecific constructs [

36]. Similarly, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) can be engineered to target multiple antigens simultaneously, combining the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the other therapeutic agents, and antiviral drugs [

37].

4. Case studies on successful overcoming of variants resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy

Monoclonal antibody therapy has been a promising approach in the treatment of various viral infections. However, the emergence of variants that are resistant to monoclonal antibodies has become a major challenge in the field.

In the case of COVID-19 disease, monoclonal antibodies have shown promising results in reducing hospitalizations and deaths among high-risk patients. However, the emergence of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has raised concerns about their efficacy. Variants such as B.1.1.7 (first identified in the UK) [

38], B.1.351 (first identified in South Africa) [

39], and P.1 (first identified in Brazil) [

40], have mutations in their spike protein that may reduce the effectiveness of monoclonal antibodies.

Despite these challenges, several case studies have demonstrated the successful overcoming of variants resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy for COVID-19 disease treatments. One such case study involved a patient who was infected with the B.1.351 variant and received a single infusion of bamlanivimab and etesevimab, two monoclonal antibodies developed by Eli Lilly and Company [

41]. The patient had mild symptoms at baseline but rapidly deteriorated after receiving treatment due to viral replication despite having detectable levels of both monoclonal antibodies in their blood.

However, after receiving a second infusion of bamlanivimab and etesevimab along with an additional monoclonal antibody, casirivimab, the patient’s symptoms improved significantly, and they were discharged from the hospital within a few days. This case study highlights the importance of using multiple monoclonal antibodies with different binding sites to overcome variants resistance.

In the case of flu, Influenza virus is a highly contagious respiratory pathogen that causes seasonal epidemics and occasional pandemics. The virus undergoes frequent mutations, leading to the emergence of new strains that can evade the host immune response and become resistant to antiviral drugs. Monoclonal antibodies are designed to target specific viral proteins and prevent their entry into host cells or neutralize their activity. However, the variability of influenza viruses poses a challenge to the development of effective monoclonal antibodies that can recognize multiple strains [

42].

An approach is to use combinations of monoclonal antibodies that target different epitopes on viral proteins. This strategy can increase the breadth and potency of neutralization against multiple strains and reduce the risk of resistance development. A study published in Nature Communications in 2019 reported the development of two monoclonal antibodies called 5F7 and 3C2 that target distinct epitopes on the influenza virus hemagglutinin protein [

43]. The researchers found that the combination of 5F7 and 3C2 could neutralize a broad range of influenza A and B viruses, including those that are resistant to current antiviral drugs.

In brief, monoclonal antibody therapy has emerged as a promising treatment option for many viral infections (

Table 1). Despite concerns about variants resistance, several case studies have demonstrated successful overcoming of this challenge through the use of multiple monoclonal antibodies with different binding sites. These case studies provide hope for the continued efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy in the face of evolving variants of SARS-CoV-2, Influenza, and many other viruses.

5. Future directions and challenges

Monoclonal antibody therapy has revolutionized the treatment of various viral infections diseases. However, the emergence of variants resistance poses a significant challenge to the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy. Variants resistance occurs when the target antigen undergoes mutations that alter its structure and reduce its binding affinity to the monoclonal antibody. This article discusses the future directions and challenges of overcoming variants resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy for viral infections, including the potential for personalized medicine approaches and the need for a better understanding of mechanisms underlying variants resistance.

One potential approach to overcoming variants resistance is personalized medicine. Personalized medicine involves tailoring treatment to an individual’s genetic makeup, lifestyle, and environment. In monoclonal antibody therapy, personalized medicine could involve selecting antibodies that are specific to an individual’s unique antigen profile [

44]. This approach would require identifying biomarkers that predict response to specific antibodies and developing assays that can measure these biomarkers accurately. Personalized medicine could also involve combining different monoclonal antibodies or other therapies to target multiple pathways simultaneously.

Another approach to overcoming variants resistance is improving our understanding of the mechanisms underlying it. Variants resistance can arise from various factors such as changes in antigen expression levels or alterations in downstream signaling pathways [

45]. Understanding these mechanisms could help identify new targets for therapy or develop strategies to prevent or overcome variants resistance. For example, researchers could develop antibodies that target multiple epitopes on an antigen or use combination therapies that target different pathways simultaneously.

However, there are several challenges associated with overcoming variants resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy. One major challenge is identifying biomarkers that predict response to specific antibodies accurately. Biomarker discovery requires large-scale studies involving diverse patient populations and sophisticated analytical techniques such as genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Another challenge is developing assays that can measure these biomarkers accurately and reproducibly across different laboratories.

Another challenge is developing new technologies for producing monoclonal antibodies that are more effective against variants. Current methods for producing monoclonal antibodies involve using hybridoma technology or recombinant DNA technology [

46]. However, these methods have scalability, cost, and variability limitations. New technologies such as phage display or yeast display could overcome these limitations by allowing for the rapid screening of large libraries of antibodies and selecting those with high affinity and specificity for the target antigen [

47].

6. Regulatory considerations for approval and use of combination therapies

The emergence of variants and resistance to monoclonal antibodies has become a significant challenge in the field. To overcome this challenge, researchers are exploring new strategies and approaches to improve the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy.

One promising approach is the use of combination therapies that target multiple pathways or antigens simultaneously. This approach can enhance the therapeutic effect and reduce the likelihood of resistance development. However, regulatory considerations for approval and use of combination therapies pose significant challenges.

The regulatory agencies require extensive preclinical and clinical data to demonstrate safety and efficacy before approving any new drug or combination therapy. The development process for combination therapies is more complex than that for single-agent therapies due to the need for additional studies to evaluate drug interactions, dosing regimens, and potential adverse effects.

Moreover, there are challenges in designing clinical trials for combination therapies. The selection of appropriate patient populations, endpoints, and biomarkers is critical to demonstrate clinical benefit. Additionally, there may be ethical concerns about exposing patients to multiple drugs with unknown interactions or adverse effects.

To address these challenges, regulatory agencies have developed guidelines for the development and approval of combination therapies. These guidelines emphasize the need for a comprehensive understanding of drug interactions and safety profiles before initiating clinical trials.

Furthermore, regulatory agencies encourage collaboration between industry stakeholders and academic researchers to facilitate innovation in drug development. This collaboration can help identify new targets or pathways that can be targeted with combination therapies.

7. Conclusion

Monoclonal antibody therapy has revolutionized the treatment of various diseases, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and infectious diseases. However, the emergence of variants and resistance to monoclonal antibodies has posed a significant challenge in clinical practice. In this article, we discussed the overcoming of variants resistance in monoclonal antibody therapy and its implications for future research and clinical practice.

Summary of Key Points:

Understanding the Mechanisms of Resistance: The first step in overcoming variants resistance is to understand the mechanisms behind it. Variants can arise due to genetic mutations or changes in protein expression levels. These changes can affect the binding affinity between the monoclonal antibody and its target antigen, leading to reduced efficacy.

Developing Novel Monoclonal Antibodies: Once the mechanisms of resistance are understood, researchers can develop novel monoclonal antibodies that can overcome these variants. This can be achieved by modifying existing antibodies or developing new ones that target different epitopes on the antigen.

Combination Therapy: Another approach to overcoming variants resistance is through combination therapy. This involves using multiple monoclonal antibodies targeting different epitopes on the same antigen or a monoclonal antibody in combination with other drugs targeting different pathways.

Personalized Medicine: Personalized medicine is another approach to overcoming variants resistance. This involves tailoring treatment based on an individual’s genetic makeup and disease characteristics.

Author Contributions

MM, & MA performed overall writing of the paper including research, literature review, and analysis of data; AA, & HA literature review, and analysis of data; AM Supervision and editing of the review paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at University of Bahri for the supportive cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Singh, S., et al., Monoclonal antibodies: a review. Current clinical pharmacology, 2018. 13(2): p. 85-99. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, V. An overview of monoclonal antibodies. in Seminars in oncology nursing. 2019. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.M., et al., Monoclonal antibody successes in the clinic. Nature biotechnology, 2005. 23(9): p. 1073-1078. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K., The history of monoclonal antibody development–progress, remaining challenges, and future innovations. Annals of medicine and surgery, 2014. 3(4): p. 113-116.

- Sun, B., et al., Aptamer-based sample purification for mass spectrometric quantification of trastuzumab in human serum. Talanta, 2023. 257: p. 124349. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, B., et al., Monoclonal antibody therapies for COVID-19: lessons learned and implications for the development of future products. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2022: p. 102798. [CrossRef]

- Otsubo, R. and T. Yasui, Monoclonal antibody therapeutics for infectious diseases: Beyond normal human immunoglobulin. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2022. 240: p. 108233. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G., Pillai, V.S. and Veettil, M.V., Approaches and advances in the development of potential therapeutic targets and antiviral agents for the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2020. 885, p.173450.

- Zurawski, D.V. and M.K. McLendon, Monoclonal antibodies as an antibacterial approach against bacterial pathogens. Antibiotics, 2020. 9(4): p. 155. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C., M. Bhattacharya, and A.R. Sharma, Emerging mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 variants and their role in antibody escape to small molecule-based therapeutic resistance. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 2022. 62: p. 64-73.

- Lipsitch, M. and G.R. Siber, How can vaccines contribute to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem? MBio, 2016. 7(3): p. 10.1128/mbio. 00428-16.

- Zhao, F., et al., Challenges and developments in universal vaccine design against SARS-CoV-2 variants. npj Vaccines, 2022. 7(1): p. 167.

- Wudhikarn, K., B. Wills, and A.M. Lesokhin, Monoclonal antibodies in multiple myeloma: Current and emerging targets and mechanisms of action. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology, 2020. 33(1): p. 101143. [CrossRef]

- Wohlbold, T.J. and Krammer, F., In the shadow of hemagglutinin: a growing interest in influenza viral neuraminidase and its role as a vaccine antigen. Viruses, 2014. 6(6), pp.2465-2494. [CrossRef]

- Marasco, W.A. and Sui, J., The growth and potential of human antiviral monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nature biotechnology, 2007. 25(12), pp.1421-1434. [CrossRef]

- Brand, T.M., Iida, M. and Wheeler, D.L., Molecular mechanisms of resistance to the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab. Cancer biology & therapy, 2011. 11(9), pp.777-792. [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.L., Raman, R., Clark, T. and Sasisekharan, R., Complexity of viral epitope surfaces as evasive targets for vaccines and therapeutic antibodies. Frontiers in immunology, 2022.13, p.904609. [CrossRef]

- Le Basle, Y., Chennell, P., Tokhadze, N., Astier, A. and Sautou, V., Physicochemical stability of monoclonal antibodies: a review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2020. 109(1), pp.169-190. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y., Pop, L.M. and Vitetta, E.S., Engineering therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Immunological reviews, 2008. 222(1), pp.9-27. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.L., Suscovich, T.J., Fortune, S.M. and Alter, G., Beyond binding: antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2018. 18(1), pp.46-61. [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.R., Williamson, R.A. and Parren, P.W., Antibody and virus: binding and neutralization. Virology, 2000. 270(1), pp.1-3. [CrossRef]

- White, H.N., B-cell memory responses to variant viral antigens. Viruses, 2021. 13(4), p.565. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Chen, Y., Park, J., Liu, X., Hu, Y., Wang, T., McFarland, K. and Betenbaugh, M.J., Design and production of bispecific antibodies. Antibodies, 2019. 8(3), p.43. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Mo, Y., Tang, M., Shen, J., Qi, Y., Zhao, W., Huang, Y., Xu, Y. and Qian, C., Bispecific antibodies: from research to clinical application. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021. 12, p.1555. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Wen, W. and Qin, W., Bispecific antibodies as a development platform for new concepts and treatment strategies. International journal of molecular sciences, 2016. 18(1), p.48. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., van Duijnhoven, S.M., Sijts, A.J. and van Elsas, A., Bispecific antibodies targeting dual tumor-associated antigens in cancer therapy. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 2020. 146, pp.3111-3122.

- Klein, C., Schaefer, W., Regula, J.T., Dumontet, C., Brinkmann, U., Bacac, M. and Umaña, P., Engineering therapeutic bispecific antibodies using CrossMab technology. Methods, 2019. 154, pp.21-31. [CrossRef]

- Einsele, H., Borghaei, H., Orlowski, R.Z., Subklewe, M., Roboz, G.J., Zugmaier, G., Kufer, P., Iskander, K. and Kantarjian, H.M., The BiTE (bispecific T-cell engager) platform: development and future potential of a targeted immuno-oncology therapy across tumor types. Cancer, 2020. 126(14), pp.3192-3201. [CrossRef]

- Gall, J.M., Davol, P.A., Grabert, R.C., Deaver, M. and Lum, L.G., T cells armed with anti-CD3× anti-CD20 bispecific antibody enhance killing of CD20+ malignant B cells and bypass complement-mediated rituximab resistance in vitro. Experimental hematology, 2005. 33(4), pp.452-459. [CrossRef]

- Marasco, W.A. and Sui, J., The growth and potential of human antiviral monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nature biotechnology, 2007. 25(12), pp.1421-1434. [CrossRef]

- McEnaney, P.J., Parker, C.G., Zhang, A.X. and Spiegel, D.A., Antibody-recruiting molecules: an emerging paradigm for engaging immune function in treating human disease. ACS chemical biology, 2012. 7(7), pp.1139-1151. [CrossRef]

- Hangartner, L., Zinkernagel, R.M. and Hengartner, H., Antiviral antibody responses: the two extremes of a wide spectrum. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2006. 6(3), pp.231-243. [CrossRef]

- Norman, R.A., Ambrosetti, F., Bonvin, A.M., Colwell, L.J., Kelm, S., Kumar, S. and Krawczyk, K., Computational approaches to therapeutic antibody design: established methods and emerging trends. Briefings in bioinformatics, 2020. 21(5), pp.1549-1567. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.L., Ellerman, D., Mathieu, M., Hristopoulos, M., Chen, X., Li, Y., Yan, X., Clark, R., Reyes, A., Stefanich, E. and Mai, E., Anti-CD20/CD3 T cell–dependent bispecific antibody for the treatment of B cell malignancies. Science translational medicine, 2015. 7(287), pp.287ra70-287ra70.

- Dong, J., Huang, B., Wang, B., Titong, A., Gallolu Kankanamalage, S., Jia, Z., Wright, M., Parthasarathy, P. and Liu, Y., Development of humanized tri-specific nanobodies with potent neutralization for SARS-CoV-2. Scientific reports, 2020. 10(1), p.17806.

- Holliger, P. and Hudson, P.J., Engineered antibody fragments and the rise of single domains. Nature biotechnology, 2005. 23(9), pp.1126-1136. [CrossRef]

- Marei, H.E., Cenciarelli, C. and Hasan, A., Potential of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell International, 2022. 22(1), pp.1-12. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Kim, E.J., Lee, S.W. and Kwon, D., Review of the early reports of the epidemiological characteristics of the B. 1.1. 7 variant of SARS-CoV-2 and its spread worldwide. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, 2021. 12(3), p.139. [CrossRef]

- Eyal, N., Caplan, A. and Plotkin, S., COVID vaccine efficacy against the B. 1.351 (“South African”) variant—The urgent need to lay the groundwork for possible future challenge studies. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2022. 18(1), p.1917240.

- Silva, M.S.D., Demoliner, M., Hansen, A.W., Gularte, J.S., Silveira, F., Heldt, F.H., Filippi, M., Pereira, V.M.D.A.G., Silva, F.P.D., Mallmann, L. and Fink, P., Early detection of SARS-CoV-2 P. 1 variant in Southern Brazil and reinfection of the same patient by P. 2. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo, 2021. 63, p.e58. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M., Arora, P., Groß, R., Seidel, A., Hörnich, B.F., Hahn, A.S., Krüger, N., Graichen, L., Hofmann-Winkler, H., Kempf, A. and Winkler, M.S., SARS-CoV-2 variants B. 1.351 and P. 1 escape from neutralizing antibodies. Cell, 2021.184(9), pp.2384-2393. [CrossRef]

- Sautto, G.A., Kirchenbaum, G.A. and Ross, T.M., Towards a universal influenza vaccine: different approaches for one goal. Virology journal, 2018. 15(1), pp.1-12. [CrossRef]

- Karakus, U., Thamamongood, T., Ciminski, K., Ran, W., Günther, S.C., Pohl, M.O., Eletto, D., Jeney, C., Hoffmann, D., Reiche, S. and Schinköthe, J., MHC class II proteins mediate cross-species entry of bat influenza viruses. Nature, 2019. 567(7746), pp.109-112. [CrossRef]

- An, Z., Monoclonal antibodies—a proven and rapidly expanding therapeutic modality for human diseases. Protein & cell, 2010. 1(4), pp.319-330. [CrossRef]

- Viloria-Petit, A., Crombet, T., Jothy, S., Hicklin, D., Bohlen, P., Schlaeppi, J.M., Rak, J. and Kerbel, R.S., Acquired resistance to the antitumor effect of epidermal growth factor receptor-blocking antibodies in vivo: a role for altered tumor angiogenesis. Cancer research, 2001. 61(13), pp.5090-5101.

- Parray, H.A., Shukla, S., Samal, S., Shrivastava, T., Ahmed, S., Sharma, C. and Kumar, R., Hybridoma technology a versatile method for isolation of monoclonal antibodies, its applicability across species, limitations, advancement and future perspectives. International immunopharmacology, 2020. 85, p.106639. [CrossRef]

- Azzazy, H.M. and Highsmith Jr, W.E., Phage display technology: clinical applications and recent innovations. Clinical biochemistry, 2002. 35(6), pp.425-445.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).