Submitted:

02 November 2023

Posted:

03 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

| Parameter | Intervention Group I (MR) | Intervention Group II (CT) |

| Number of Participants (n) | 47 | 21 |

| Gender (Male) | 47 | 21 |

| Age (years) | 28.4 ± 4.6 | 29.1 ± 3.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 79.6 ± 9.3 | 81.2 ± 10.5 |

| Height (cm) | 181.5 ± 6.3 | 179.8 ± 5.9 |

| Duration of Intervention (weeks) | 12 | 12 |

| Physical Workload (hours/week) | 24.7 ± 2.9 | 24.5 ± 3.1 |

| Weight of Protective Gear (kg) | 33.5 ± 2.1 | 33.4 ± 2.3 |

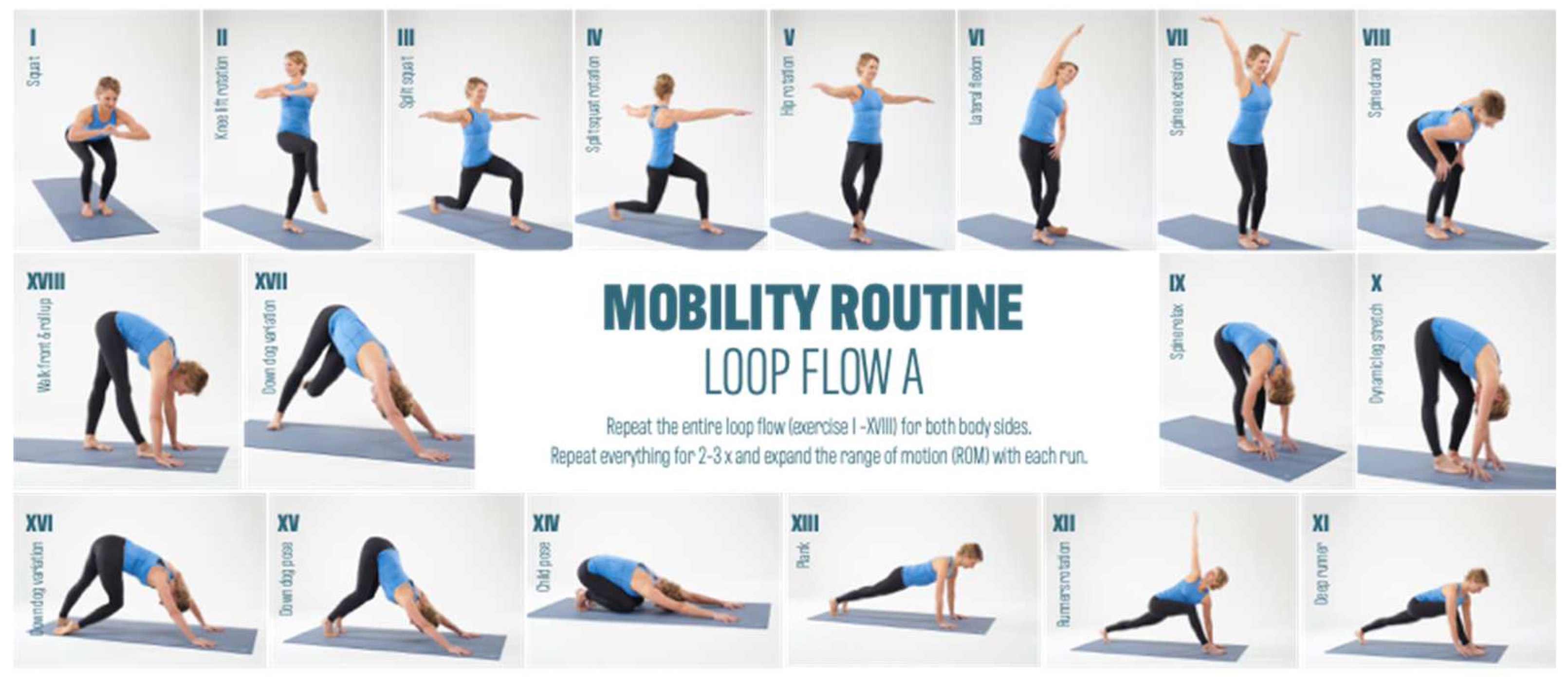

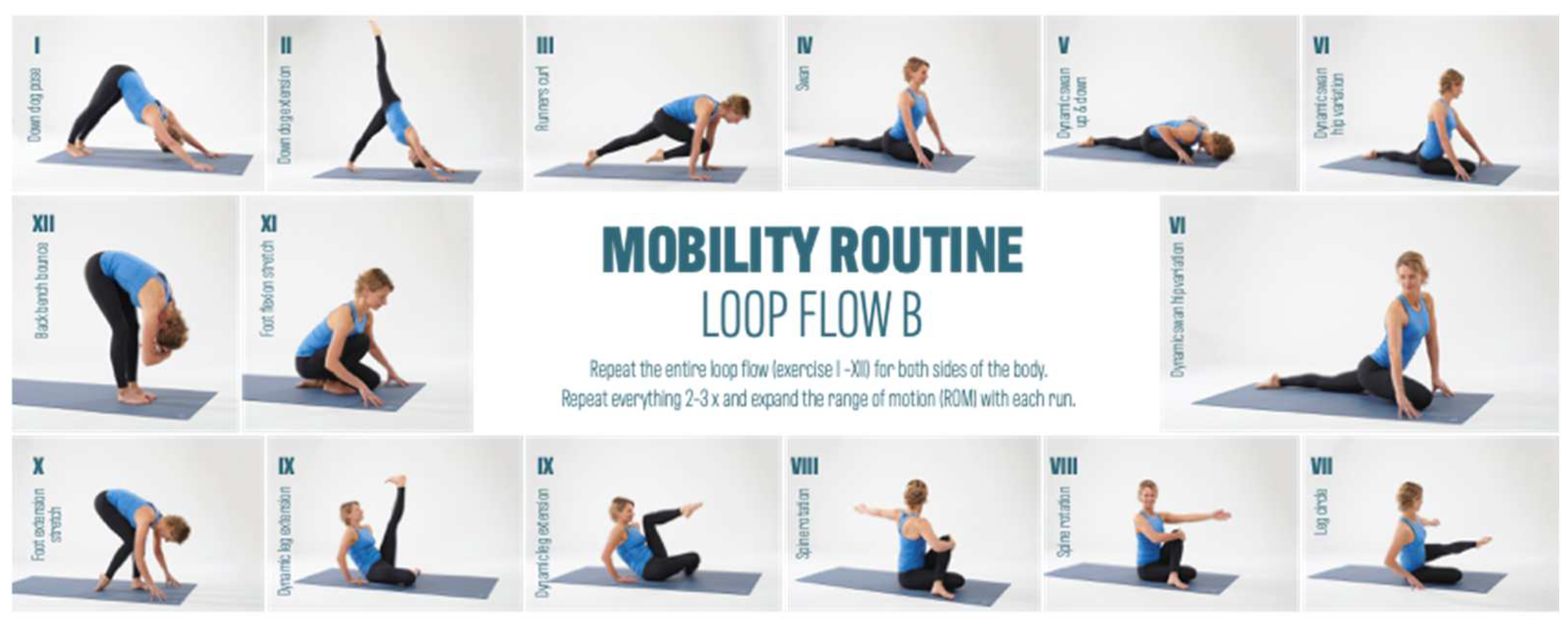

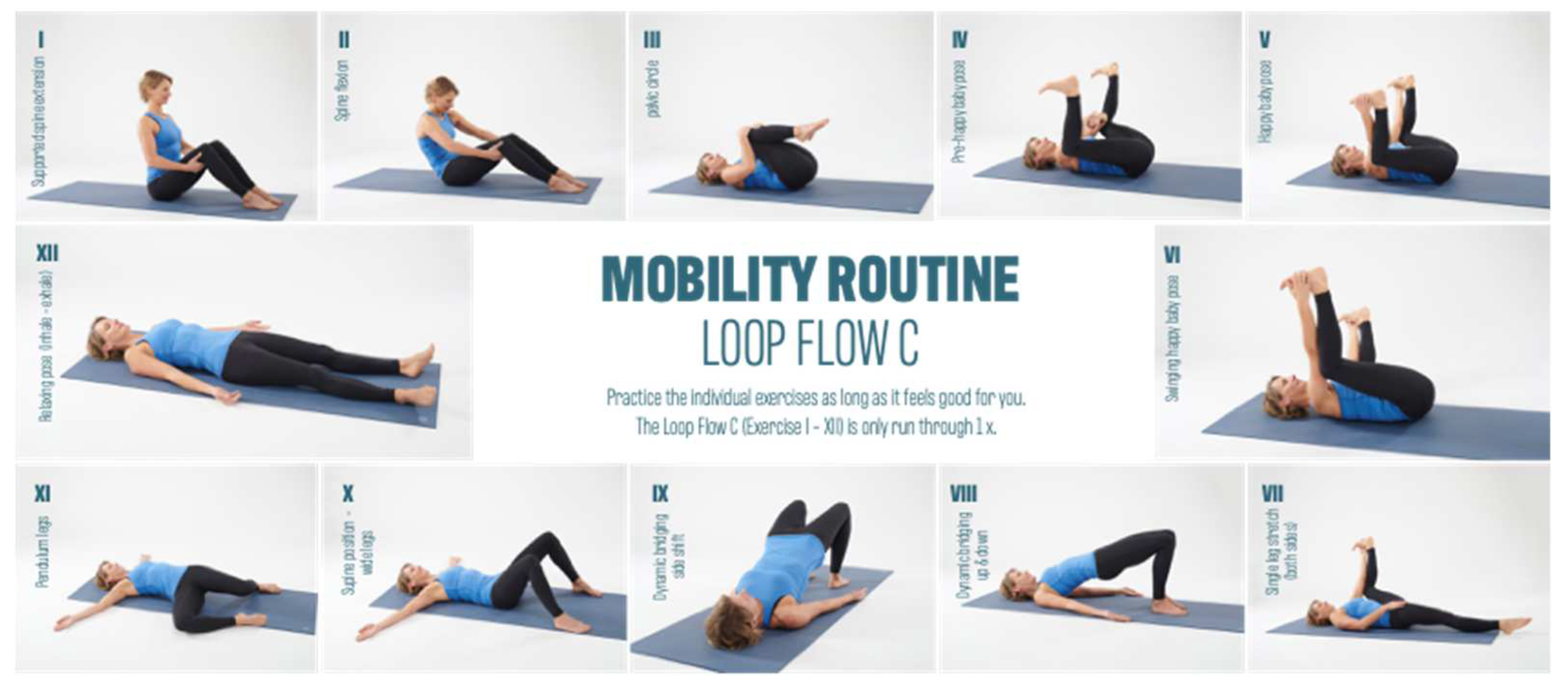

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Measurement Technique

3. Results

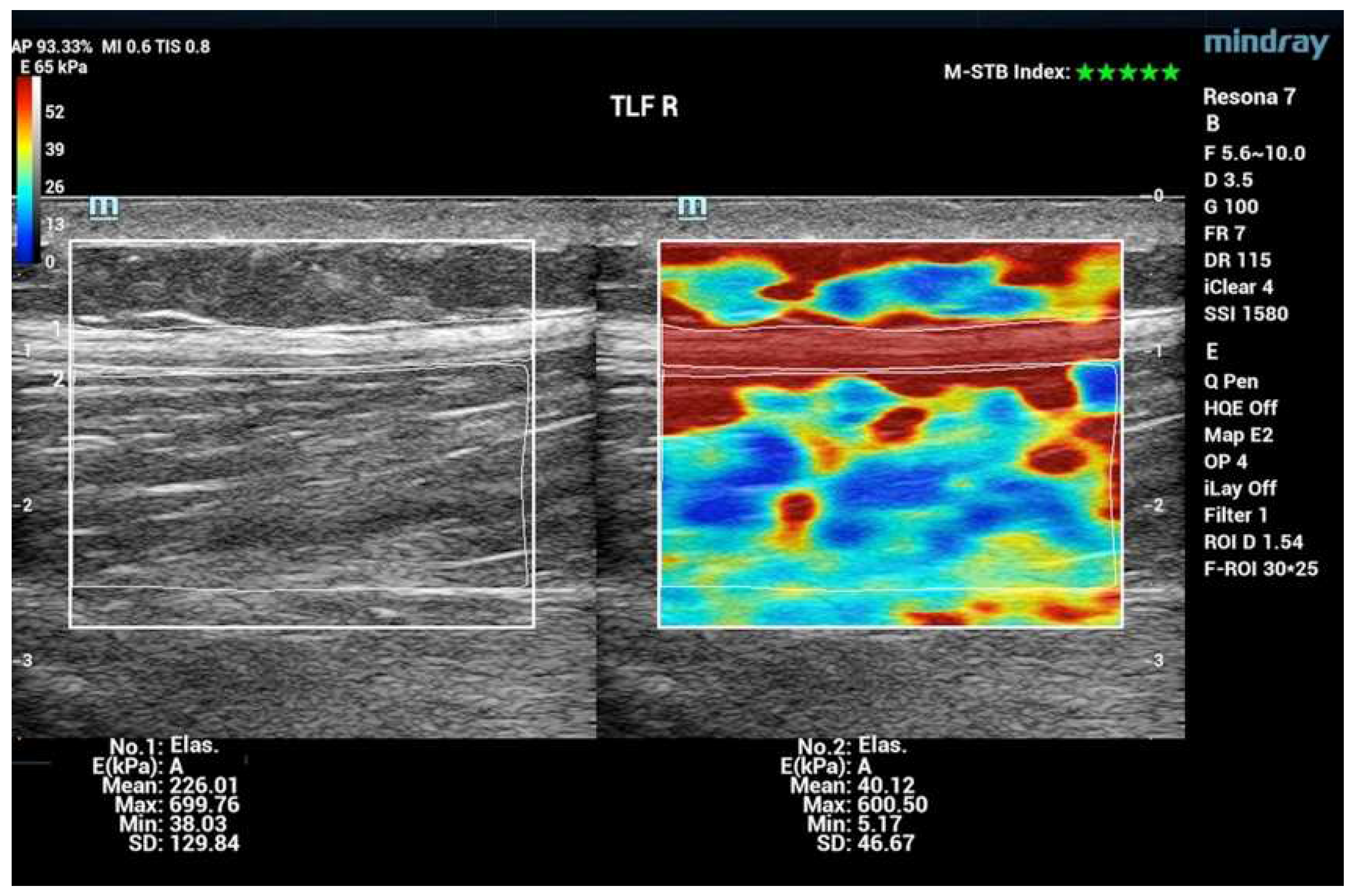

3.1. Shear Wave Elastography (SWE)

3.2. Range of Motion (ROM)

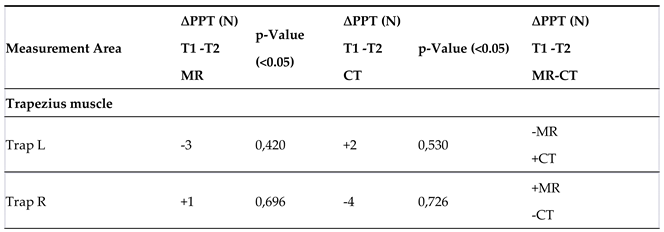

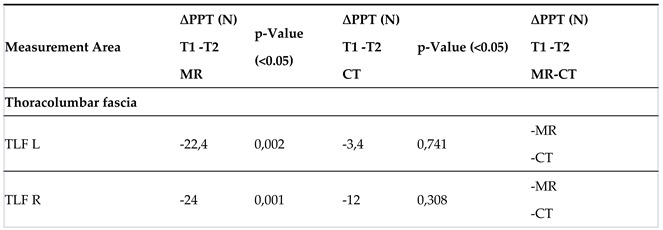

3.3. Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT)

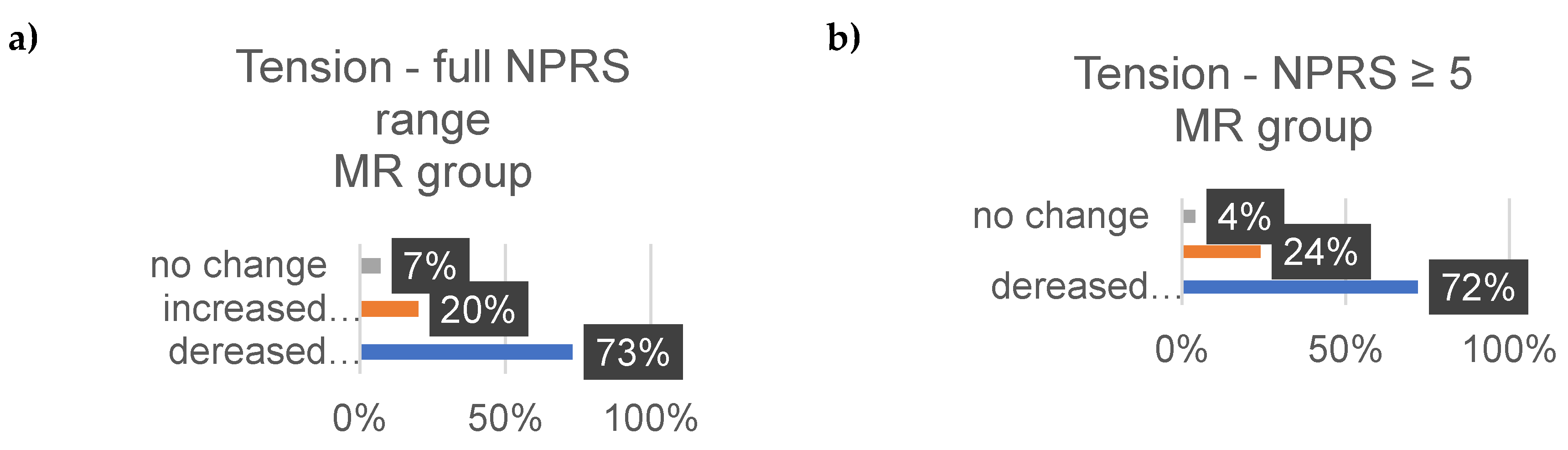

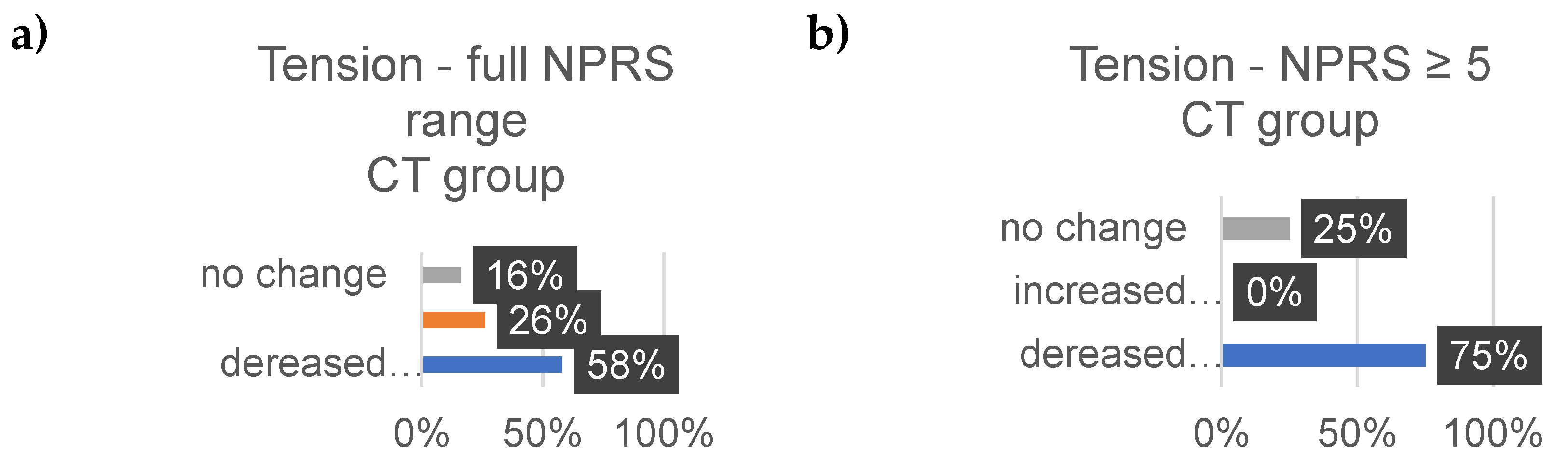

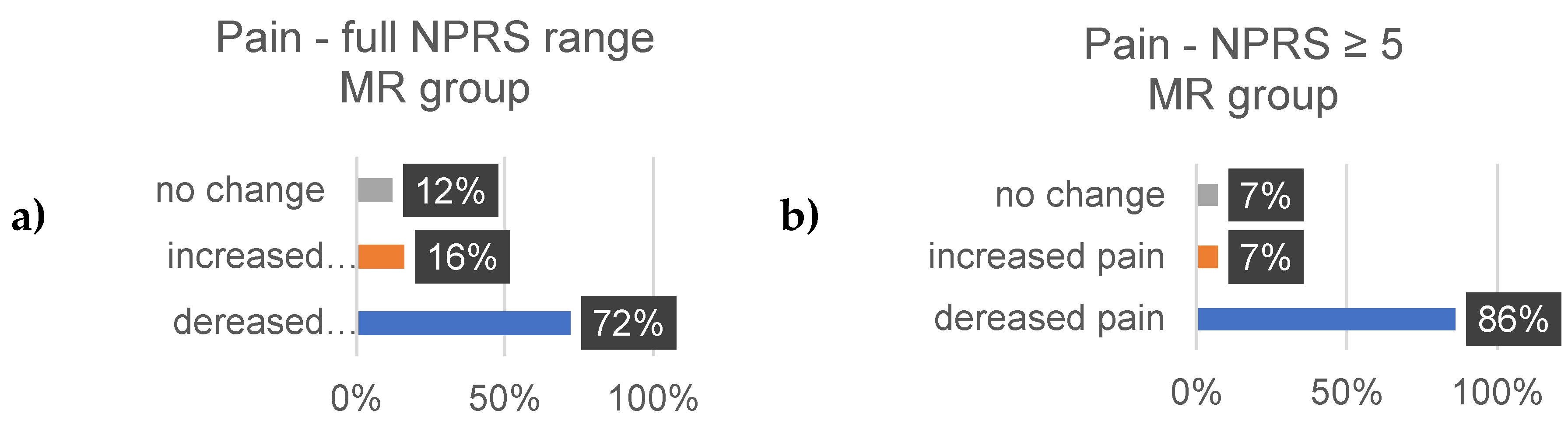

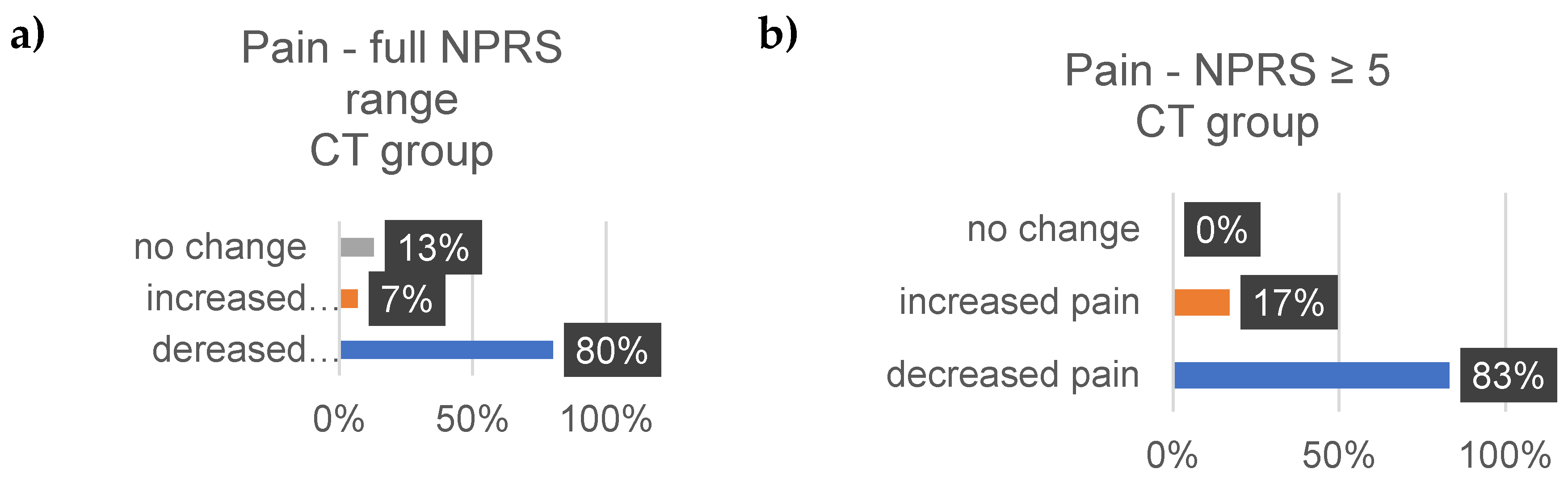

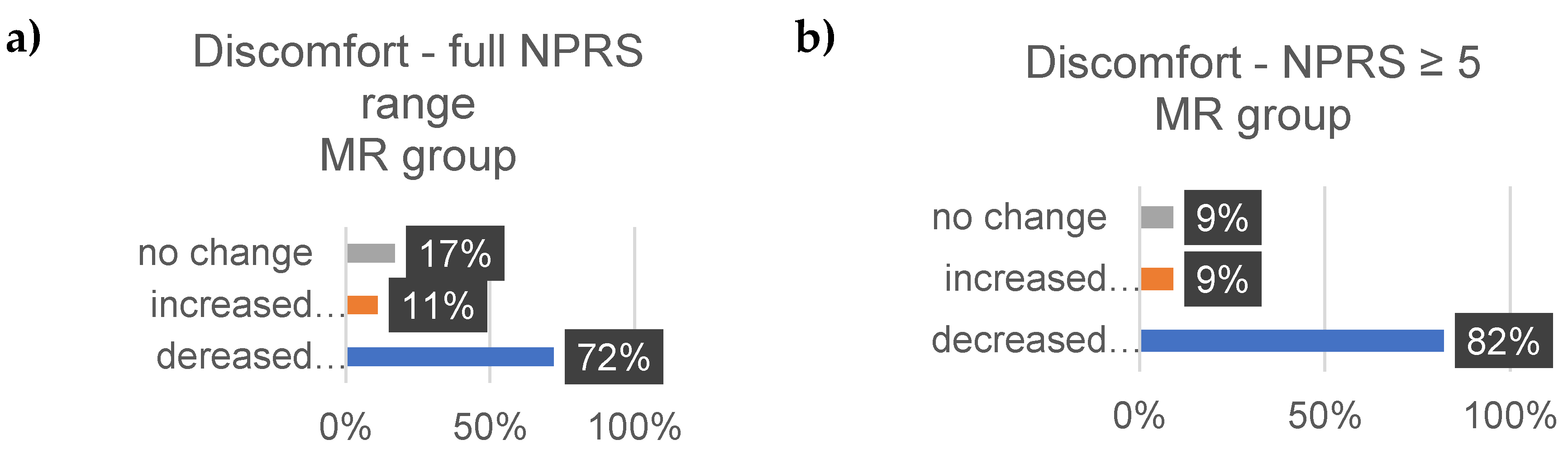

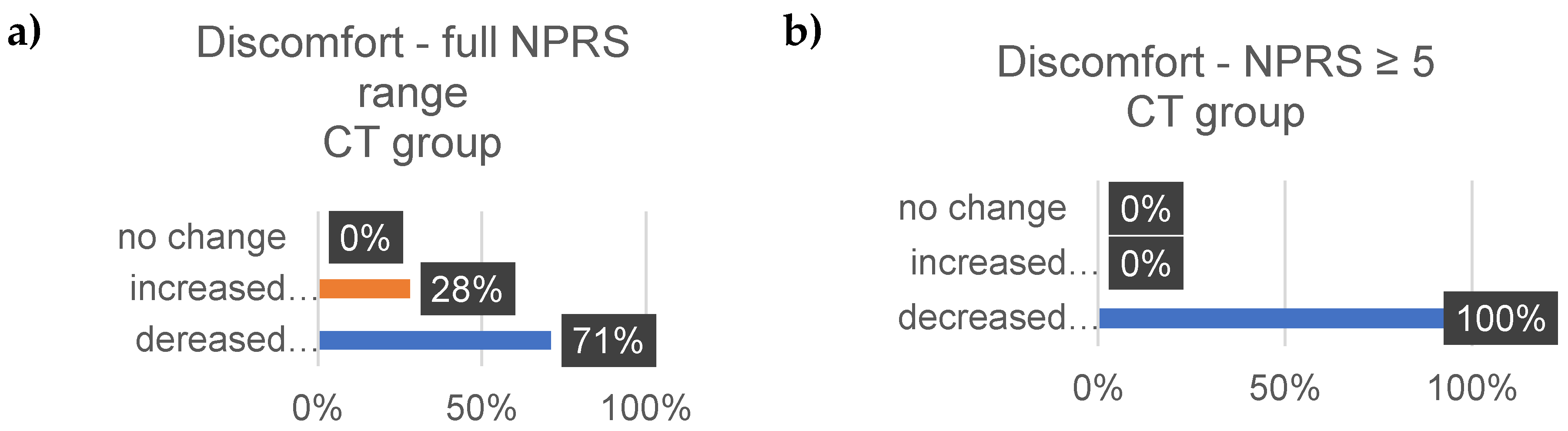

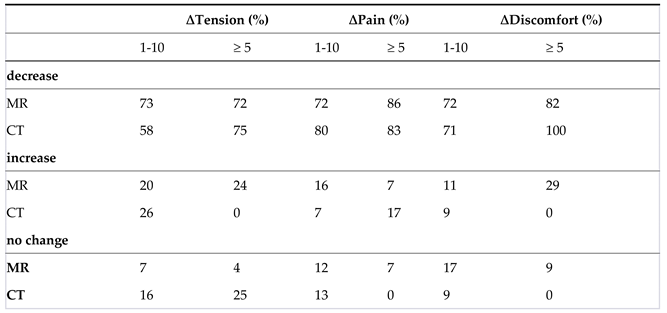

3.4. Well-Being

4. Discussion

Elastic Modulus Analysis:

Range of Motion (ROM)

Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT)

Well-Being

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weishaupt, P.; Obermüller, R.; Hofmann, A. [Spine stabilizing muscles in golfers]. Sportverletzung Sportschaden : Organ der Gesellschaft fur Orthopadisch-Traumatologische Sportmedizin 2000, 14, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maus, U.; et al. [Comparison of trunk muscle strength of soccer players with and without low back pain]. Z Orthop Unfall 2010, 148, 459–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, J.M. Muscle strains: prevention and treatment. The Physician and sportsmedicine 1980, 8, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, P.C.; Lewis, J.; Story, I. , Inter-therapist reliability in locating latent myofascial trigger points using palpation. Manual Therapy 1997, 2, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weishaupt, P.; Obermüller, R.; Hofmann, A. [Spine stabilizing muscles in golfers]. Sportverletz Sportschaden 2000, 14, 55–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaStayo, P.C.; et al. Eccentric muscle contractions: their contribution to injury, prevention, rehabilitation, and sport. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2003, 33, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witvrouw, E.; et al. Muscle Flexibility as a Risk Factor for Developing Muscle Injuries in Male Professional Soccer Players:A Prospective Study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2003, 31, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paternostro-Sluga, T.; Zöch, C. [Conservative treatment and rehabilitation of shoulder problems]. Radiologe 2004, 44, 597–603. [Google Scholar]

- Dexel, J.; Kopkow, C.; Kasten, P. [Scapulothoracic dysbalance in overhead athletes. Causes and therapy strategies]. Orthopade 2014, 43, 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevin, H.M.; et al. Effect of Stretching on Thoracolumbar Fascia Injury and Movement Restriction in a Porcine Model. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2018, 97, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemková, E., O. Poór, and M. Jeleň, Between-side differences in trunk rotational power in athletes trained in asymmetric sports. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2019, 32, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, M.N.; et al. An Evidence-Based Framework for Strengthening Exercises to Prevent Hamstring Injury. Sports Med 2018, 48, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.P.; Cosgrave, C.H. To stretch or not to stretch: the role of stretching in injury prevention and performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010, 20, 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owoeye, O.B.A.; et al. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ Warm-Up Programme in Male Youth Football: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 2014, 13, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzini, M.; Dvorak, J. FIFA 11+: an effective programme to prevent football injuries in various player groups worldwide-a narrative review. Br J Sports Med 2015, 49, 577–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvers-Granelli, H.; et al. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program in the Collegiate Male Soccer Player. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2015, 43, 2628–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mechelen, W.; et al. Prevention of running injuries by warm-up, cool-down, and stretching exercises. Am J Sports Med 1993, 21, 711–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, K.; Bishop, P.; Jones, E. Warm-up and stretching in the prevention of muscular injury. Sports Med 2007, 37, 1089–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; et al. Dysregulation of the Inflammatory Mediators in the Multifidus Muscle After Spontaneous Intervertebral Disc Degeneration SPARC-null Mice is Ameliorated by Physical Activity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018, 43, E1184–e1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauermeister, W. Pesavento, Andreas, Real Time Elastographie of Fascia and Myofascial Trigger Points, in Seminar Series Triggerpoint-Shockwave Therapy. 2000, Sportschule Hennef Germany.

- Langevin, H.M.; et al. Reduced thoracolumbar fascia shear strain in human chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakonaki, E.E.; Allen, G.M.; Wilson, D.J. Ultrasound elastography for musculoskeletal applications. Br J Radiol 2012, 85, 1435–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botanlioglu, H.; et al. Shear wave elastography properties of vastus lateralis and vastus medialis obliquus muscles in normal subjects and female patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Skeletal Radiology 2013, 42, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boettner, C. Interrater reliability of ultrasound elastography to examine stiffness and elasticity of muscles and fascia of the lower extremity in healthy adults. 2018, Technical University Munich Germany.

- Creze, M.; et al. Shear wave sonoelastography of skeletal muscle: basic principles, biomechanical concepts, clinical applications, and future perspectives. Skeletal Radiol 2018, 47, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppenhaver, S.; et al. Reliability of ultrasound shear-wave elastography in assessing low back musculature elasticity in asymptomatic individuals. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2018, 39, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauermeister, W. Ultraschall Elastografie. Stellenwert in der Sportmedizin. Sportärztezeitung, 2019. 02.

- Hvedstrup, J.K., L.T.; Schytz, M.A.; Schytz, H.W., Increased neck muscle stiffness in migraine patiens with ictal neckpain: A shear wave elastography study. International Headache Society, 2020. Schytz, H.W., Increased neck muscle stiffness in migraine patiens with ictal neckpain: A shear wave elastography study. International Headache Society.

- Dubois, G.; et al. Reliable Protocol for Shear Wave Elastography of Lower Limb Muscles at Rest and During Passive Stretching. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2015, 41, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.; et al. Invasive Breast Cancer: Relationship between Shear-wave Elastographic Findings and Histologic Prognostic Factors. Radiology 2012, 263, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frulio, N.; Trillaud, H. Ultrasound elastography in liver. Diagn Interv Imaging 2013, 94, 515–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eby, S.F.; et al. Validation of shear wave elastography in skeletal muscle. Journal of Biomechanics 2013, 46, 2381–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawker, G.A.; et al. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011, 63 (Suppl 11), S240–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.; Hoggart, B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 2005, 14, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Valente, M.A.; Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Jensen, M.P. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 2011, 152, 2399–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karstoft, K.; Pedersen, B.K. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: focus on metabolism and inflammation. Immunol Cell Biol 2016, 94, 146–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillon Barcelos, R.; et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation: liver responses and adaptations to acute and regular exercise. Free Radic Res 2017, 51, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, R.J.; et al. Exercise and the Regulation of Immune Functions. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2015, 135, 355–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farzanegi, P.; et al. Mechanisms of beneficial effects of exercise training on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Roles of oxidative stress and inflammation. Eur J Sport Sci 2019, 19, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, A.E.; Barbe, M.F. Inflammation reduces physiological tissue tolerance in the development of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2004, 14, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Campisi, J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014, 69 (Suppl 1), S4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.P.; et al. Biochemicals associated with pain and inflammation are elevated in sites near to and remote from active myofascial trigger points. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008, 89, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, M.; Huh, Y.; Ji, R.R. Roles of inflammation, neurogenic inflammation, and neuroinflammation in pain. J Anesth 2019, 33, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mense, S. and U. Hoheisel, Evidence for the existence of nociceptors in rat thoracolumbar fascia. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2016, 20, 623–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mense, S. Muskeln, Faszien und Schmerz, ed. 1. 2021: Thieme Verlag.

- Langevin, H.M.; Sherman, K.J. Pathophysiological model for chronic low back pain integrating connective tissue and nervous system mechanisms. Med Hypotheses 2007, 68, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrueta, L.; et al. Stretching Impacts Inflammation Resolution in Connective Tissue. J Cell Physiol 2016, 231, 1621–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørklund, G.; et al. Does diet play a role in reducing nociception related to inflammation and chronic pain? Nutrition 2019, 66, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa-Rodriguez, M.; et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index Scores Are Associated with Pressure Pain Hypersensitivity in Women with Fibromyalgia. Pain Med, 2019. [CrossRef]

- França, M.E.D.; et al. Manipulation of the Fascial System Applied During Acute Inflammation of the Connective Tissue of the Thoracolumbar Region Affects Transforming Growth Factor-β1 and Interleukin-4 Levels: Experimental Study in Mice. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 587373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Region |

Description |

Subject- Position |

|

| 1 | M. trapezius Trap. L |

10 cm paravertebral from the center of the cervical spine acromion |

sitting |

| 2 | M. trapezius Trap R |

10 cm paravertebral from the center of the cervical spine acromion |

sitting |

| 3 | Plantar fascia PLF L |

Calcaneus | prone position |

| 4 | Plantar fascia PLF R |

Calcaneus | prone position |

| 5 | Thoracolumbar fascia TLF L4/5 L | Line ilium upper margin 2 cm paravertebral proc. spinous process |

prone position |

| 6 | Thoracolumbar fascia TLF L4/5 R | Line ilium upper margin 2 cm paravertebral spinous process |

prone position |

| 7 | M. gluteus medius GlutMed L |

2.5 cm distal to the center of the crista iliac | prone position |

| 8 | M. gluteus medius GlutMed R |

2.5 cm distal to the center of the crista iliac | prone position |

| 9 | M. gluteus maximus / GlutMax L | Midpoint between greater trochanter and sacrum | prone position |

| 10 | M. gluteus maximus / GlutMax R | Midpoint between greater trochanter and sacrum | prone position |

| 11 | M. biceps femoris BicFem L |

20 cm from the fibula head in the direction Tuber ischiadicum |

prone position |

| 12 | M. biceps femoris BicFem R |

20 cm from the fibula head in the direction Tuber ischiadicum |

prone position |

| 13 | M. gastrocnemius lateralis / Gastroc L | 12 cm below the popliteal fossa, lateral calf | prone position |

| 14 | M. gastrocnemius lateralis / Gastroc R | 12 cm below the popliteal fossa, lateral calf | prone position |

| 15 | Mm. adductor ADD L |

20 cm from adductor tuberculum dist. femur towards the pubic tubercle | supine position |

| 16 | Mm. adductor ADD R |

20 cm from adductor tuberculum dist. femur towards pubic tubercle | supine position |

| 17 | M. rectus femoris RFM L |

0 cm from the upper edge of the patella in direction. Spina iliaca anterior superior (SIAS) | supine position |

| 18 | M. rectus femoris RFM R |

0 cm from the upper edge of the patella in direction. Spina iliaca anterior superior (SIAS) | supine position |

| 19 | M. tibialis anterior TibA L |

9 cm below the patella, 1 finger width lateral to the margo anterior of the tibia | supine position |

| 20 | M. tibialis anterior TibA L |

9 cm below the patella, 1 finger width lateral to the margo anterior of the tibia | supine position |

| 1 | The measurement positions were determined individually reproducibly on the basis of anatomical features using centimeter measures. |

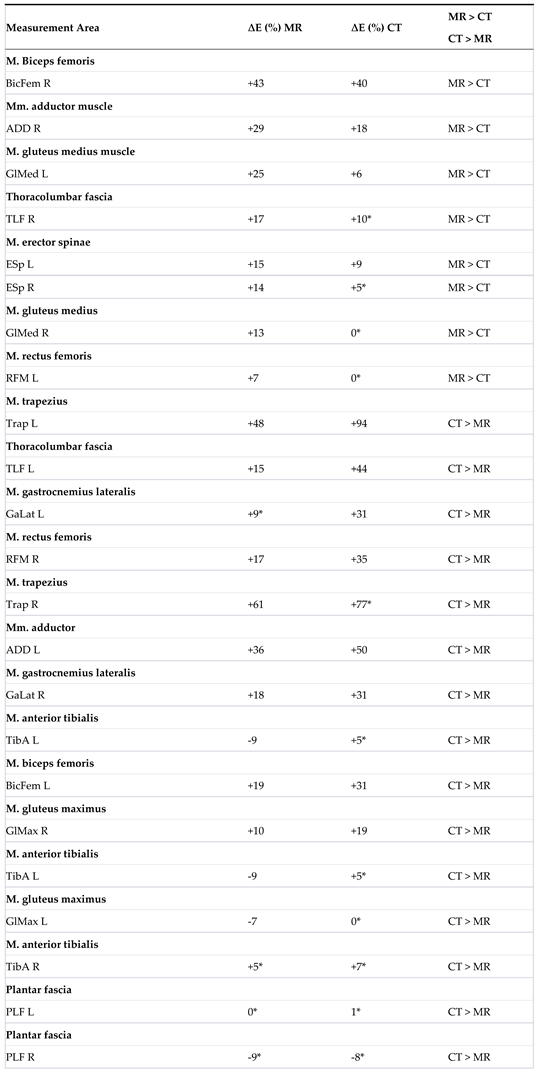

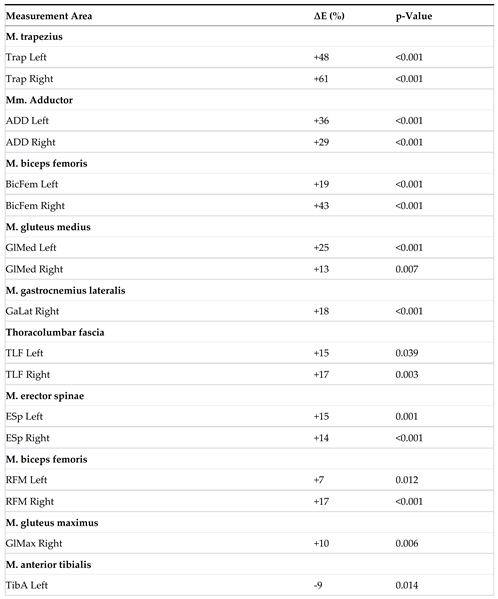

| 2 | The table displays the measurement areas (L = left, R = right) in the MR group T1/T2 (n = 47), where a significant change in the elasticity modulus ∆E was observed. A ‘+’ before E indicates an increase, while a ‘–‘ indicates a decrease. The significance level (p-value) is 0.05. |

| 3 |

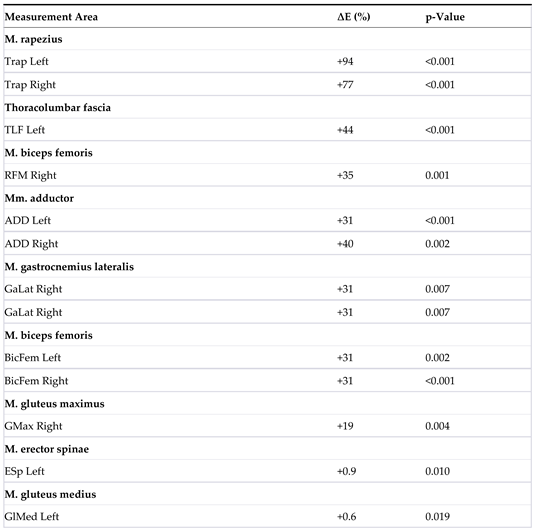

The table shows the comparison of ∆E for the MR and CT groups.

The * indicates that the difference value is based on a parametric distribution of the baseline data.

|

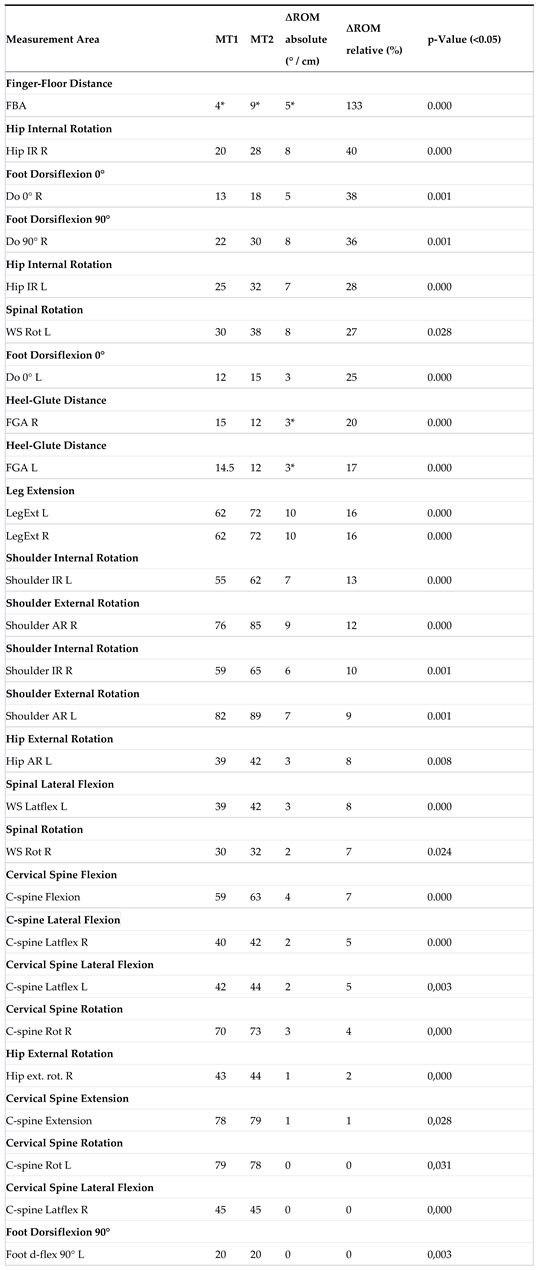

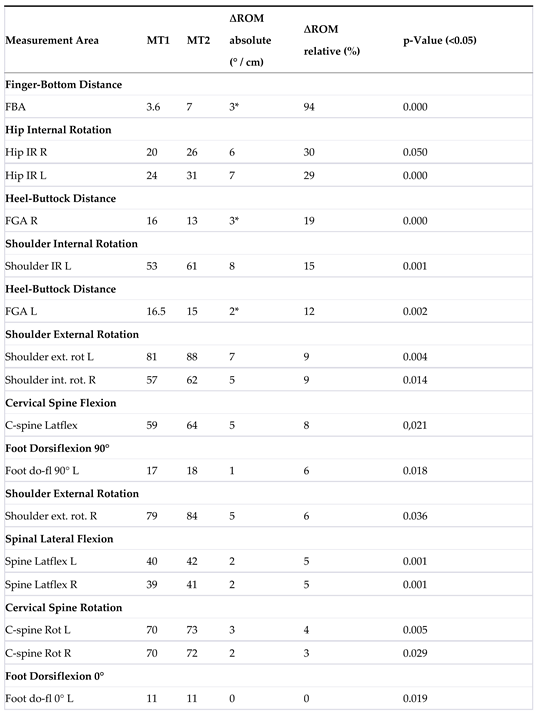

| 4 | Table 6 displays the Range of Motion (∆ROM) for the MR group, consisting of 47 participants. The absolute results are presented in degrees or centimeters (* indicated in centimeters), while the relative results are expressed in percentages. A total of 27 measurement areas were analyzed, of which thirteen were bilateral in nature (significance level= 0.05). |

| 5 | Table 7 illustrates the Range of Motion (∆ROM) for the CT group, comprising 21 participants. The results are presented in degrees or centimeters (* indicated in centimeters), while relative results are expressed in percentages. A total of 27 measurement areas were analyzed, with thirteen of them being bilateral (significance level=0,05). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).