Submitted:

02 November 2023

Posted:

03 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

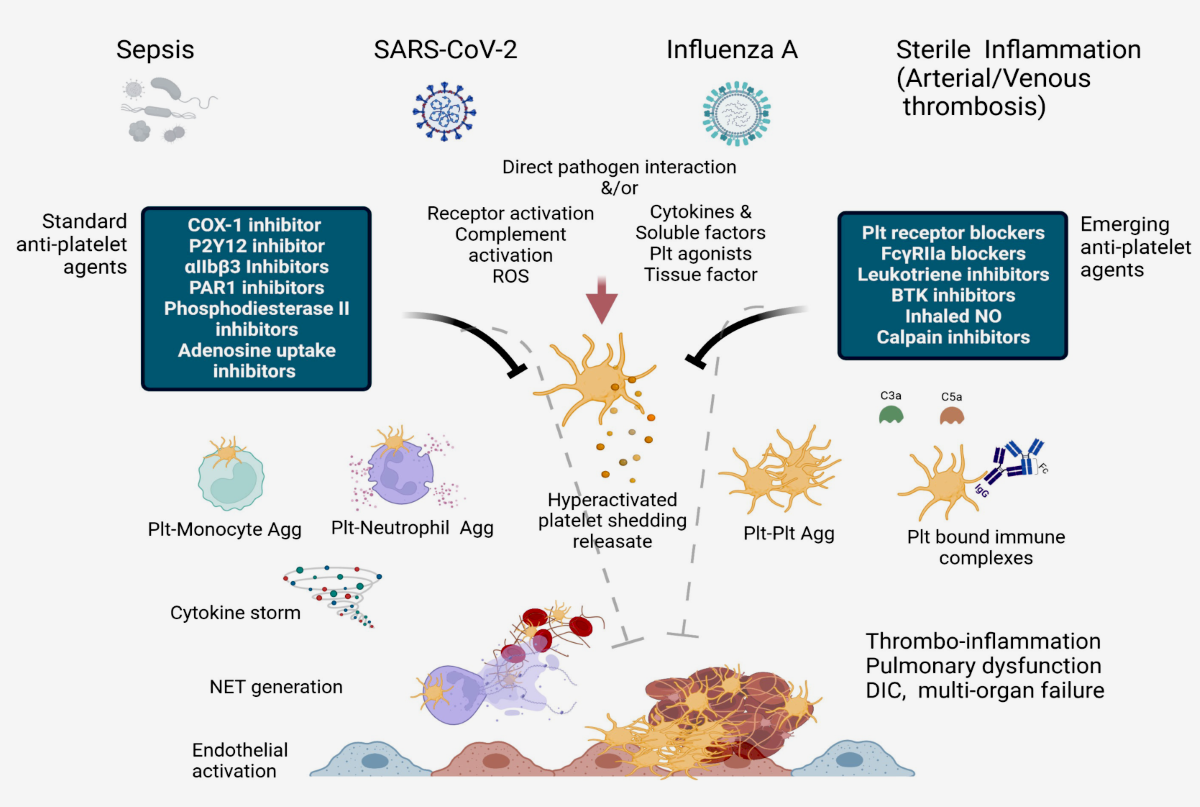

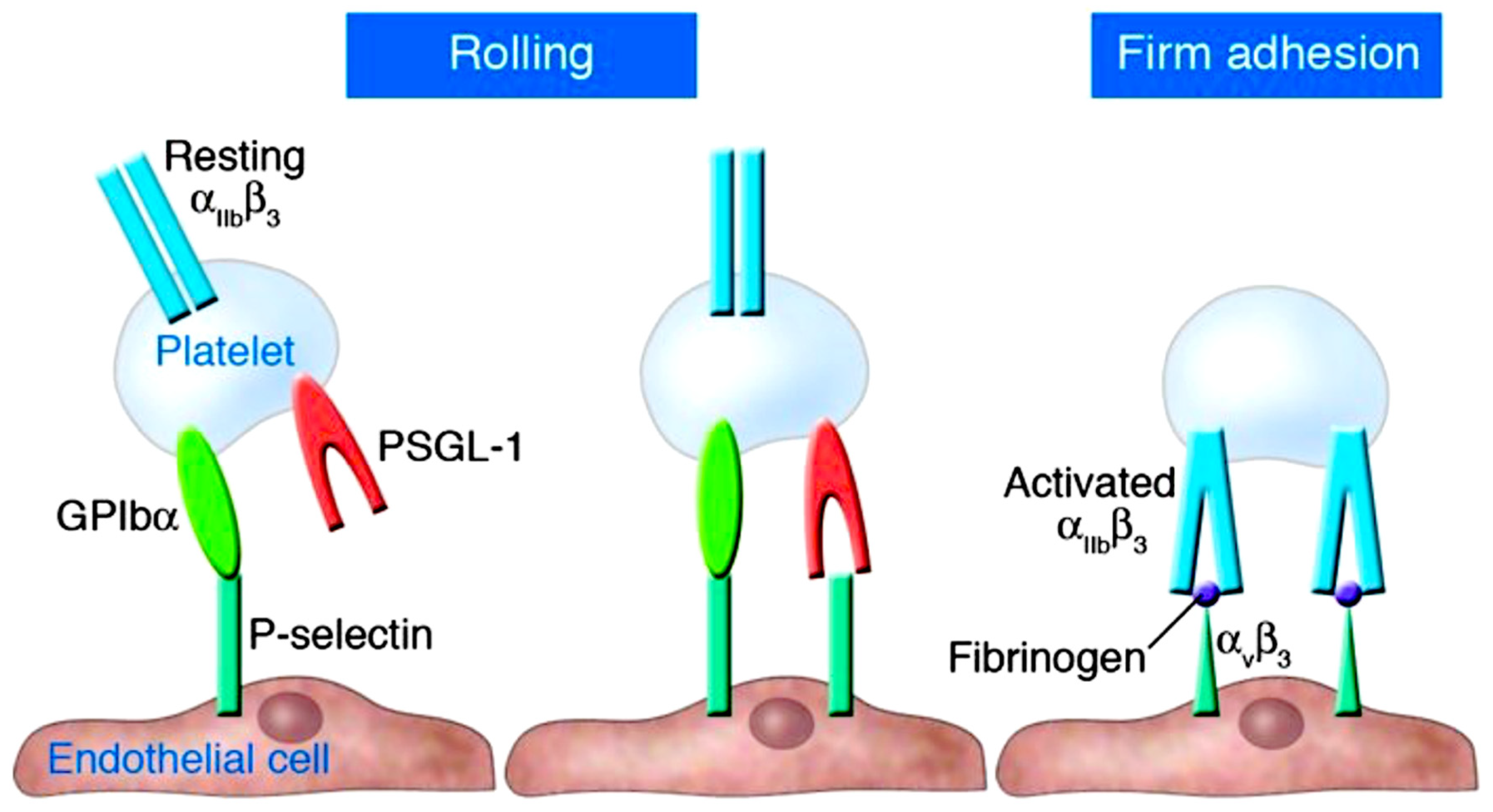

2. Understanding the role of platelets and P-selectin as key actors in thromboinflammation

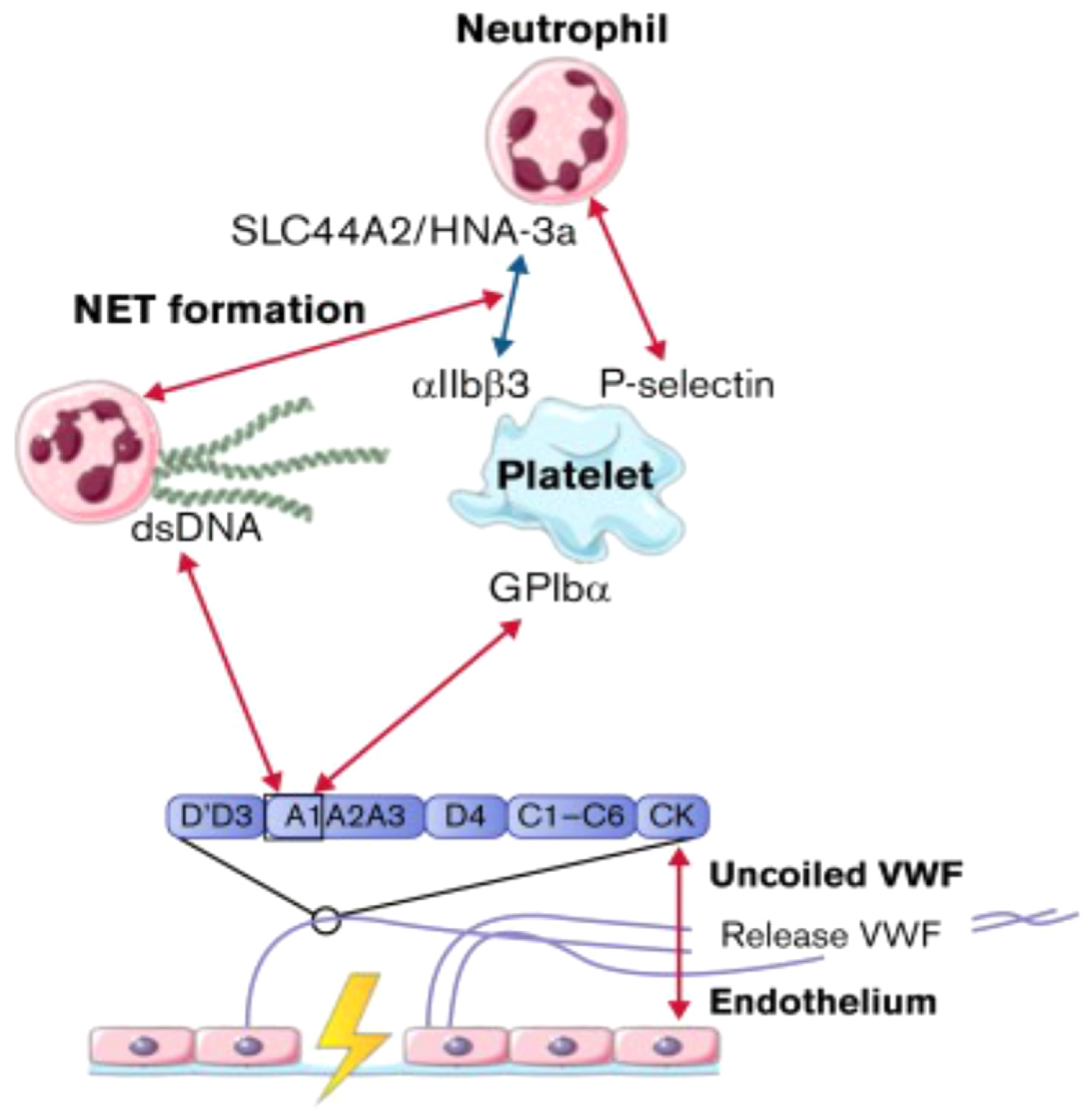

3. Interaction of NETs with Ultra-Large VWF in Thromboinflammatory Vasculopathy

3.1. Identifying the role played by NETs.

3.2. The role of VWF and ADAMTS13

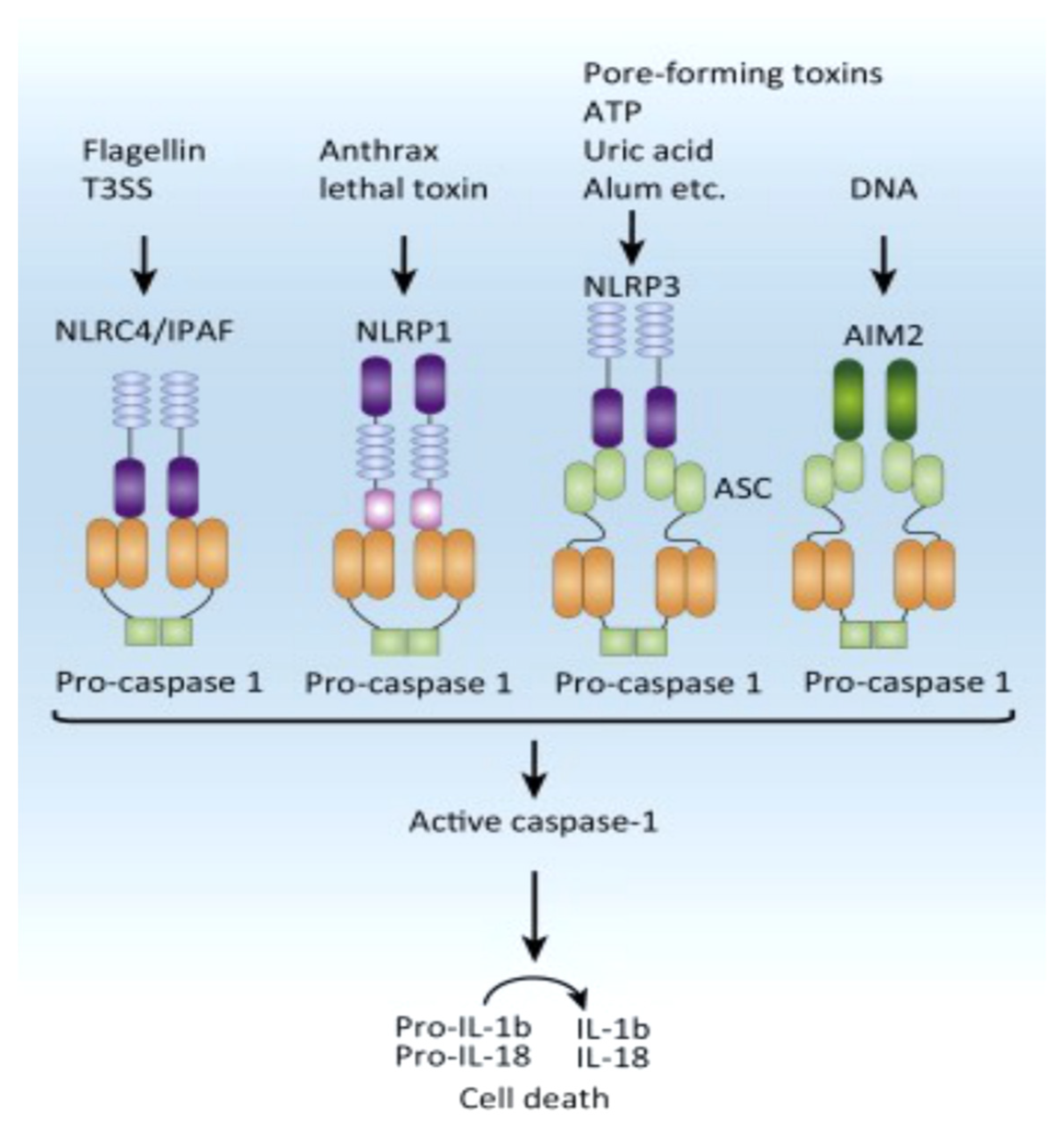

Inflammasone to the direction of all actors

4. Focusing on the thromboinflammation process in atherosclerosis and COVID-19.

4.1. Implication of atherosclerosis

4.2. Implication of Thromboinflammation in COVID-19

5. Conclusion and Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999 Jan 14;340(2):115-26. [CrossRef]

- Trivigno SMG, Guidetti GF, Barbieri SS, Zarà M. Blood Platelets in Infection: The Multiple Roles of the Platelet Signalling Machinery. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr 18;24(8):7462. [CrossRef]

- Wagner DD, Frenette PS. The vessel wall and its interactions. Blood. 2008; 111:5271–5281. [CrossRef]

- Yao M, Ma J, Wu D, Fang C, Wang Z, Guo T, Mo J. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate deep vein thrombosis : from mechanism to therapy. Front Immunol. 2023 Aug 23 ;14:1198952. [CrossRef]

- Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013; 13:34–45. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Tyagi T, Antoniak S. Platelet in thrombo-inflammation: Unraveling new therapeutic targets. Front Immunol. 2022 Nov 14 ;13:1039843. [CrossRef]

- Krott KJ, Feige T, Elvers M. Flow Chamber Analyses in Cardiovascular Research : Impact of Platelets and the Intercellular Crosstalk with Endothelial Cells, Leukocytes, and Red Blood Cells. Hamostaseologie. 2023 Oct;43(5):338-347. [CrossRef]

- Thachil J. Semin Thromb Hemost. Platelets in Inflammatory Disorders: A Pathophysiological and Clinical Perspective 2015 Sep;41(6):572-81. [CrossRef]

- Wagner DD, Burger PC. Platelets in inflammation and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2131–2137. [CrossRef]

- Solomon SD, Lowenstein CJ, Bhatt AS, Peikert A, Vardeny O, Kosiborod MN, Berger JS, Reynolds HR, Mavromichalis S, Barytol A, Althouse AD, Luther JF, Leifer ES, Kindzelski AL, Cushman M, Gong MN, Kornblith LZ, Khatri P, Kim KS, Baumann Kreuziger L, Wahid L, Kirwan BA, Geraci MW, Neal MD, Hochman JS; ACTIV4a Investigators. Effect of the P-Selectin Inhibitor Crizanlizumab on Survival Free of Organ Support in Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation. 2023 Aug;148(5):381-390. [CrossRef]

- Mayadas TN, Johnson RC, Rayburn H, Hynes RO, Wagner DD. Leukocyte rolling and extravasation are severely compromised in P selectin-deficient mice. Cell. 1993; 74:541–554. [CrossRef]

- Hrachovinová I, Cambien B, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Kappelmayer J, Camphausen RT, Widom A, Xia L, Kazazian HH Jr, Schaub RG, McEver RP, Wagner DD. Interaction of P-selectin and PSGL-1 generates microparticles that correct hemostasis in a mouse model of hemophilia A. Nat Med. 2003 Aug;9(8):1020-5. [CrossRef]

- Polgar J, Matuskova J, Wagner DD. The P-selectin, tissue factor, coagulation triad. J Thromb Haemost. 2005; 3:1590–1596. [CrossRef]

- Braun OO, Slotta JE, Menger MD, Erlinge D, Thorlacius H. Primary and secondary capture of platelets onto inflamed femoral artery endothelium is dependent on P-selectin and PSGL-1. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008 Sep 11;592(1-3):128-32. [CrossRef]

- Dole VS, Bergmeier W, Patten IS, Hirahashi J, Mayadas TN, Wagner DD. PSGL-1 regulates platelet P-selectin-mediated endothelial activation and shedding of P-selectin from activated platelets. Thromb Haemost. 2007; 98:806–812. [CrossRef]

- Dole VS, Bergmeier W, Mitchell HA, Eichenberger SC, Wagner DD. Acti- vated platelets induce Weibel-Palade-body secretion and leukocyte rolling in vivo: role of P-selectin. Blood. 2005; 106:2334–2339. [CrossRef]

- Blann AD, Nadar SK, Lip GY. The adhesion molecule P-selectin and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2003 Dec;24(24):2166-79. [CrossRef]

- Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N. Soluble P-selectin and the risk of future cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2001; 103:491–495. [CrossRef]

- Trivigno SMG, Guidetti GF, Barbieri SS, Zarà M. Blood Platelets in Infection: The Multiple Roles of the Platelet Signalling Machinery. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr 18;24(8):7462. [CrossRef]

- Kisucka J, Chauhan AK, Zhao BQ, Patten IS, Yesilaltay A, Krieger M, Wagner DD. Elevated levels of soluble P-selectin in mice alter blood-brain barrier function, exacerbate stroke, and promote atherosclerosis. Blood. 2009; 113:6015–6022. [CrossRef]

- NIHR Global Health Unit on Global Surgery; Elective surgery system strengthening development, measurement, and validation of the surgical preparedness index across 1632 hospitals in 119 countries. COVIDSurg Collaborative. Lancet. 2022 Nov 5;400(10363):1607-1617. [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. SARS-CoV-2 infection and venous thromboembolism after surgery: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2022 Jan;77(1):28-39. Epub 2021 Aug 24. [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative, GlobalSurg Collaborative. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination modelling for safe surgery to save lives: data from an international prospective cohort study.Br J Surg. 2021 Sep 27;108(9):1056-1063. [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia.2021 Jun;76(6):748-758. [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Effects of pre-operative isolation on postoperative pulmonary complications after elective surgery: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2021 Nov;76(11):1454-1464. [CrossRef]

- Nappi F, Giacinto O, Ellouze O, Nenna A, Avtaar Singh SS, Chello M, Bouzguenda A, Copie X. Association between COVID-19 Diagnosis and Coronary Artery Thrombosis: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines. 2022 Mar 18;10(3):702. [CrossRef]

- Fukuhara S, Rosati CM, El-Dalati S. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020 Nov;110(5):e405-e407. [CrossRef]

- Nappi F. Incertitude Pathophysiology and Management During the First Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022 Feb;113(2):693. [CrossRef]

- Troisi R, Balasco N, Autiero I, Sica F, Vitagliano L New insight into the traditional model of the coagulation cascade and its regulation: illustrated review of a three-dimensional view. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2023 Aug 7;7(6):102160. [CrossRef]

- Rolling CC, Barrett TJ, Berger JS. Platelet-monocyte aggregates: molecular mediators of thromboinflammation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023 May 15; 10:960398. [CrossRef]

- Grover SP, Mackman N. Tissue factor: an essential mediator of hemostasis and trigger of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018; 38:709–725. [CrossRef]

- Heestermans M, Poenou G, Duchez AC, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Bertoletti L, Cognasse F. Immunothrombosis and the Role of Platelets in Venous Thromboembolic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Oct 29;23(21):13176. [CrossRef]

- Scholz T, Temmler U, Krause S, Heptinstall S, Lösche W. Transfer of tissue factor from platelets to monocytes: role of platelet-derived microvesicles and CD62P. Thromb Haemost. 2002 Dec;88(6):1033-8. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov II, Apta BHR, Bonna AM, Harper MT. Platelet P-selectin triggers rapid surface exposure of tissue factor in monocytes. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:13397. [CrossRef]

- Hrachovinová I, Cambien B, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Kappelmayer J, Camphausen RT, Widom A, Xia L, Kazazian HH Jr, Schaub RG, McEver RP, et al. Interaction of P-selectin and PSGL-1 generates microparticles that cor- rect hemostasis in a mouse model of hemophilia A. Nat Med. 2003;9:1020– 1025. [CrossRef]

- Burger PC, Wagner DD. Platelet P-selectin facilitates atherosclerotic lesion development. Blood. 2003; 101:2661–2666. [CrossRef]

- Doran AC, Meller N, McNamara CA. Role of smooth muscle cells in the initiation and early progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008; 28:812–819. [CrossRef]

- Burger PC, Wagner DD. Platelet P-selectin facilitates atherosclerotic lesion development. Blood. 2003; 101:2661–2666. [CrossRef]

- Doran AC, Meller N, McNamara CA. Role of smooth muscle cells in the initiation and early progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008; 28:812–819. [CrossRef]

- Libby P, Everett BM. Novel antiatherosclerotic therapies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019; 39:538–545. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Zhao J, Deng L, Ishimwe N, Pauli J, Wu W, Shan S, Kempf W, Ballantyne MD, Kim D, Lyu Q, Bennett M, Rodor J, Turner AW, Lu YW, Gao P, Choi M, Warthi G, Kim HW, Barroso MM, Bryant WB, Miller CL, Weintraub NL, Maegdefessel L, Miano JM, Baker AH, Long X. INKILN is a Novel Long Noncoding RNA Promoting Vascular Smooth Muscle Inflammation via Scaffolding MKL1 and USP10. Circulation. 2023 Jul 4;148(1):47-67. [CrossRef]

- Zhong M, Wang XH, Zhao Y. Platelet factor 4 (PF4) induces cluster of differentiation 40 (CD40) expression in human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) through the SIRT1/NF-κB/p65 signaling pathway. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2023 Sep;59(8):624-635. [CrossRef]

- Yu G, Rux AH, Ma P, Bdeir K, Sachais BS. Endothelial expression of E-selec- tin is induced by the platelet-specific chemokine platelet factor 4 through LRP in an NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Blood. 2005; 105:3545–3551. [CrossRef]

- Stadtmann A, Brinkhaus L, Mueller H, Rossaint J, Bolomini-Vittori M, Bergmeier W, Van Aken H, Wagner DD, Laudanna C, Ley K, et al. Rap1a activation by CalDAG-GEFI and p38 MAPK is involved in E-selectin- dependent slow leukocyte rolling. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2074–2085. [CrossRef]

- Yuan T, Aisan A, Maheshati T, Tian R, Li Y, Chen Y. Predictive value of combining leucocyte and platelet counts for mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients after percutaneous coronary intervention treatment in Chinese population: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2023 Jul 18;13(7):e060756. [CrossRef]

- Duerschmied D, Suidan GL, Demers M, Herr N, Carbo C, Brill A, Cifuni SM, Mauler M, Cicko S, Bader M, et al. Platelet serotonin promotes the recruitment of neutrophils to sites of acute inflammation in mice. Blood. 2013; 121:1008–1015. [CrossRef]

- Etulain J, Martinod K, Wong SL, Cifuni SM, Schattner M, Wagner DD. P-selectin promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation in mice. Blood. 2015; 126:242–246. [CrossRef]

- Yun SH, Sim EH, Goh RY, Park JI, Han JY. Platelet activation: the mecha- nisms and potential biomarkers. Biomed Res Int. 2016; 2016:9060143. [CrossRef]

- Goerge T, Ho-Tin-Noe B, Carbo C, Benarafa C, Remold-O’Donnell E, Zhao BQ, Cifuni SM, Wagner DD. Inflammation induces hemorrhage in thrombocy- topenia. Blood. 2008; 111:4958–4964. [CrossRef]

- Ho-Tin-Noé B, Goerge T, Cifuni SM, Duerschmied D, Wagner DD. Platelet granule secretion continuously prevents intratumor hemorrhage. Cancer Res. 2008; 68:6851–6858. [CrossRef]

- Graca FA, Stephan A, Minden-Birkenmaier BA, Shirinifard A, Wang YD, Demontis F, Labelle M. Platelet-derived chemokines promote skeletal muscle regeneration by guiding neutrophil recruitment to injured muscles. Nat Commun. 2023 May 22;14(1):2900. [CrossRef]

- Gawaz M, Langer H, May AE. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005 Dec ;115(12):3378-84. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, Weinrauch Y, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Novel cell death program leads to neutro- phil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007; 176:231–241. [CrossRef]

- Nappi F, Bellomo F, Avtaar Singh SS. Worsening Thrombotic Complication of Atherosclerotic Plaques Due to Neutrophils Extracellular Traps: A Systematic Review.Biomedicines. 2023 Jan 2;11(1):113. [CrossRef]

- Nappi F, Nappi P, Gambardella I, Avtaar Singh SS. Thromboembolic Disease and Cardiac Thrombotic Complication in COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Metabolites. 2022 Sep 22;12(10):889. [CrossRef]

- Thiam HR, Wong SL, Wagner DD, Waterman CM. Cellular mechanisms of NETosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2020; 36:191–218. [CrossRef]

- Nappi F, Bellomo F, Avtaar Singh SS. Insights into the Role of Neutrophils and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Causing Cardiovascular Complications in Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2022 Apr 27;11(9):2460. [CrossRef]

- Nappi F, Iervolino A, Avtaar Singh SS. Thromboembolic Complications of SARS-CoV-2 and Metabolic Derangements: Suggestions from Clinical Practice Evidence to Causative Agents. Metabolites. 2021 May 25;11(6):341. [CrossRef]

- Wong SL, Wagner DD. Peptidylarginine deiminase 4: a nuclear button trig- gering neutrophil extracellular traps in inflammatory diseases and aging. FASEB J. 2018;32:fj201800691R. [CrossRef]

- Münzer P, Negro R, Fukui S, di Meglio L, Aymonnier K, Chu L, Cherpokova D, Gutch S, Sorvillo N, Shi L, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome assembly in neutrophils is supported by PAD4 and promotes NETosis under Sterile Conditions. Front Immunol. 2021; 12:683803. [CrossRef]

- Wong SL, Demers M, Martinod K, Gallant M, Wang Y, Goldfine AB, Kahn CR, Wagner DD. Diabetes primes neutrophils to undergo NETosis, which impairs wound healing. Nat Med. 2015; 21:815–819. [CrossRef]

- Thiam HR, Wong SL, Qiu R, Kittisopikul M, Vahabikashi A, Goldman AE, Goldman RD, Wagner DD, Waterman CM. Reply to Liu: the disassembly of the actin cytoskeleton is an early event during NETosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020; 117:22655–22656. [CrossRef]

- Sorvillo N, Cherpokova D, Martinod K, Wagner DD. Extracellular DNA NET- works with dire consequences for health. Circ Res. 2019; 125:470–88. [CrossRef]

- Sollberger G, Choidas A, Burn GL, Habenberger P, Di Lucrezia R, Kordes S, Menninger S, Eickhoff J, Nussbaumer P, Klebl B, et al. Gasdermin D plays a vital role in the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci Immunol. 2018;3: eaar6689. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy N, Douda DN, Brüggemann TR, Ricklefs I, Duvall MG, Abdulnour RE, Martinod K, Tavares L, Wang X, Cernadas M, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program-3 Inves- tigators. Neutrophil cytoplasts induce TH17 differentiation and skew inflam- mation toward neutrophilia in severe asthma. Sci Immunol. 2018;3: eaao4747. [CrossRef]

- Yipp BG, Kubes P. NETosis: how vital is it? Blood. 2013; 122:2784–2794. [CrossRef]

- Fukui S, Gutch S, Fukui S, Cherpokova D, Aymonnier K, Sheehy CE, Chu L, Wagner DD. The prominent role of hematopoietic peptidyl argi- nine deiminase 4 in arthritis: collagen- and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced arthritis model in C57BL/6 MICE. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022; 74:1139–1146. [CrossRef]

- Morrell CN, Hilt ZT, Pariser DN, Maurya P. PAD4 and von Willebrand Factor Link Inflammation and Thrombosis. Circ Res. 2019 Aug 16;125(5):520-522. [CrossRef]

- Sorvillo N, Mizurini DM, Coxon C, Martinod K, Tilvawala R, Cherpokova D, Salinger AJ, Seward RJ, Staudinger C, Weerapana E, et al. Plasma peptidy- larginine deiminase IV promotes VWF-platelet string formation and accel- erates thrombosis after vessel injury. Circ Res. 2019; 125:507–519. [CrossRef]

- Franklin BS, Bossaller L, De Nardo D, Ratter JM, Stutz A, Engels G, Brenker C, Nordhoff M, Mirandola SR, Al-Amoudi A, et al. The adaptor ASC has extracellular and ‘prionoid’ activities that propagate inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2014; 15:727–737. [CrossRef]

- Liberale L, Holy EW, Akhmedov A, Bonetti NR, Nietlispach F, Matter CM, Mach F, Montecucco F, Beer JH, Paneni F, et al. Interleukin-1β mediates arterial thrombus formation via NET-associated tissue factor. J Clin Med. 2019;8:E2072. [CrossRef]

- Liman TG, Bachelier-Walenta K, Neeb L, Rosinski J, Reuter U, Böhm M, Endres M. Circulating endothelial microparticles in female migraineurs with aura. Cephalalgia. 2015; 35:88–94. [CrossRef]

- Wu R, Wang N, Comish PB, Tang D, Kang R. Inflammasome-dependent coagulation activation in sepsis. Front Immunol. 2021; 12:641750. [CrossRef]

- Martinod K, Wagner DD. Thrombosis: tangled up in NETs. Blood. 2014; 123:2768–2776. [CrossRef]

- Döring Y, Libby P, Soehnlein O. Neutrophil extracellular traps participate in cardiovascular diseases: recent experimental and clinical insights. Circ Res. 2020; 126:1228–1241. [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, Dagna L, Martinod K, Dixon DL, Van Tassell BW, Dentali F, Montecucco F, Massberg S, Levi M, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:319–329. [CrossRef]

- Lindner, D.; Fitzek, A.; Bräuninger, H.; Aleshcheva, G.; Edler, C.; Meissner, K.; Scherschel, K.; Kirchhof, P.; Escher, F.; Schultheiss, H.P. Association of Cardiac Infection With SARS-CoV-2 in Confirmed COVID-19 Autopsy Cases. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 1281–1285. [CrossRef]

- Novotny,J.;Oberdieck,P.;Titova,A.;Pelisek,J.;Chandraratne,S.;Nicol,P.;Hapfelmeier,A.;Joner,M.;Maegdefessel,L.;Poppert, H.; et al. Thrombus NET content is associated with clinical outcome in stroke and myocardial infarction. Neurology 2020, 94, e2346–e2360. [CrossRef]

- Ducroux,C.;DiMeglio,L.;Loyau,S.;Delbosc,S.;Boisseau,W.;Deschildre,C.;BenMaacha,M.;Blanc,R.;Redjem,H.;Ciccio,G.; et al. Thrombus neutrophil extracellular traps content impair tPA-induced thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2018, 49, 754–757. [CrossRef]

- Blasco, A.; Coronado, M.-J.; Hernández-Terciado, F.; Martín, P.; Royuela, A.; Ramil, E.; García, D.; Goicolea, J.; Del Trigo, M.; Ortega, J.; et al. Assessment of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Coronary Thrombus of a Case Series of Patients With COVID-19 and Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 469. [CrossRef]

- Blasco A, Bellas C, Goicolea L, Muñiz A, Abraira V, Royuela A, Mingo S, Oteo JF, García-Touchard A, Goicolea FJ. Immunohistological analysis of intracoronary thrombus aspirate in STEMI patients: clinical implications of pathological findings. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2017;70(3):170-177. [CrossRef]

- Langseth, M.S.; Helseth, R.; Ritschel, V.; Hansen, C.H.; Andersen, G.; Eritsland, J.; Halvorsen, S.; Fagerland, M.W.; Solheim, S.; Arnesen, H.; et al. Double-Stranded DNA and NETs Components in Relation to Clinical Outcome After ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5007. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Wu Z, Long Q, Huang J, Hong T, Liu W, Lin J. Insights into immunothrombosis: the interplay among neutrophil extracellular trap, von Wil- lebrand Factor, and ADAMTS13. Front Immunol. 2020;11:610696. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Chen J, López JA. Flow-driven assembly of VWF fibres and webs in in vitro microvessels. Nat Commun. 2015; 6:7858. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Chung DW. Inflammation, von Willebrand factor, and ADAMTS13. Blood. 2018;132:141–147. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan AK, Walsh MT, Zhu G, Ginsburg D, Wagner DD, Motto DG. The combined roles of ADAMTS13 and VWF in murine models of TTP, endotox- emia, and thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111:3452–3457. [CrossRef]

- Sadler JE. Pathophysiology of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2017;130:1181–1188. [CrossRef]

- Frenette PS, Atweh GF. Sickle cell disease: old discoveries, new con- cepts, and future promise. J Clin Invest. 2007; 117:850–858. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Zhang D, Fuchs TA, Manwani D, Wagner DD, Frenette PS. Heme- induced neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2014; 123:3818–3827. [CrossRef]

- Springer TA. von Willebrand factor, Jedi knight of the bloodstream. Blood. 2014;124:1412–1425. [CrossRef]

- Arya M, Anvari B, Romo GM, Cruz MA, Dong JF, McIntire LV, Moake JL, López JA. Ultralarge multimers of von Willebrand factor form sponta- neous high-strength bonds with the platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX complex: studies using optical tweezers. Blood. 2002; 99:3971–7. [CrossRef]

- Peetermans M, Meyers S, Liesenborghs L, Vanhoorelbeke K, De Meyer SF, Vandenbriele C, Lox M, Hoylaerts MF, Martinod K, Jacquemin M, et al. Von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 impact on the outcome of Staph- ylococcus aureus sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020; 18:722–731. [CrossRef]

- Vischer UM. von Willebrand factor, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovas- cular disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2006; 4:1186–1193. [CrossRef]

- Hanson E, Jood K, Karlsson S, Nilsson S, Blomstrand C, Jern C. Plasma levels of von Willebrand factor in the etiologic subtypes of ischemic stroke. J Thromb Haemost. 2011; 9:275–281. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan AK, Kisucka J, Brill A, Walsh MT, Scheiflinger F, Wagner DD. ADAMTS13: a new link between thrombosis and inflammation. J Exp Med. 2008; 205:2065–2074. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi C, Motto DG, Jensen M, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. ADAMTS13 deficiency exacerbates VWF-dependent acute myocardial ischemia/ reperfusion injury in mice. Blood. 2012; 120:5224–5230. [CrossRef]

- De Meyer SF, Savchenko AS, Haas MS, Schatzberg D, Carroll MC, Schiviz A, Dietrich B, Rottensteiner H, Scheiflinger F, Wagner DD. Protective anti-inflammatory effect of ADAMTS13 on myocardial isch- emia/reperfusion injury in mice. Blood. 2012; 120:5217–5223. [CrossRef]

- Zhao BQ, Chauhan AK, Canault M, Patten IS, Yang JJ, Dockal M, Scheiflinger F, Wagner DD. von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease ADAMTS13 reduces ischemic brain injury in experimental stroke. Blood. 2009; 114:3329–3334. [CrossRef]

- Michels A, Albánez S, Mewburn J, Nesbitt K, Gould TJ, Liaw PC, James PD, Swystun LL, Lillicrap D. Histones link inflammation and thrombosis through the induction of Weibel-Palade body exocytosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2016; 14:2274–2286. [CrossRef]

- Matsui T, Hamako J. Structure and function of snake venom toxins interacting with human von Willebrand factor. Toxicon. 2005 Jun 15;45(8):1075-87. [CrossRef]

- Colicchia M, Perrella G, Gant P, Rayes J. Novel mechanisms of thrombo-inflammation during infection: spotlight on neutrophil extracellular trap-mediated platelet activation. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2023 Mar 11;7(2):100116. [CrossRef]

- Courson JA, Lam FW, Langlois KW, Rumbaut RE. Histone-stimulated platelet adhesion to mouse cremaster venules in vivo is dependent on von Willebrand factor. Microcirculation. 2022 Nov;29(8):e12782. [CrossRef]

- Ward CM, Tetaz TJ, Andrews RK, Berndt MC. Binding of the von Willebrand factor A1 domain to histone. Thromb Res. 1997; 86:469–477. [CrossRef]

- DeYoung V, Singh K, Kretz CA. Mechanisms of ADAMTS13 regulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2022 Dec;20(12):2722-2732. [CrossRef]

- Wong SL, Goverman J, Staudinger C, Wagner DD. Recombinant human ADAMTS13 treatment and anti-NET strategies enhance skin allograft sur- vival in mice. Am J Transplant. 2020; 20:1162–1169. [CrossRef]

- Gajendran C, Fukui S, Sadhu NM, Zainuddin M, Rajagopal S, Gosu R, Gutch S, Fukui S, Sheehy CE, Chu L, Vishwakarma S, Jeyaraj DA, Hallur G, Wagner DD, Sivanandhan D. Alleviation of arthritis through prevention of neutrophil extracellular traps by an orally available inhibitor of protein arginine deiminase 4. Sci Rep. 2023 Feb 23;13(1):3189. [CrossRef]

- Arisz RA, de Vries JJ, Schols SEM, Eikenboom JCJ, de Maat MPM. Interaction of von Willebrand factor with blood cells in flow models: a systematic review. Blood Adv. 2022 Jul 12;6(13):3979-3990. [CrossRef]

- Black RA, Kronheim SR, Sleath Activation of interleukin-1 beta by a co-induced protease. PR. FEBS Lett. 1989 Apr 24;247(2):386-90. [CrossRef]

- Black RA, Kronheim SR, Merriam JE, March CJ, Hopp TP. A pre-aspartate-specific protease from human leukocytes that cleaves pro-interleukin-1 beta. J Biol Chem. 1989 Apr 5;264(10):5323-6. [CrossRef]

- Krieger TJ, Hook VY. Purification and characterization of a novel thiol protease involved in processing the enkephalin precursor. J Biol Chem. 1991 May 5;266(13):8376-83. [CrossRef]

- Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Muñoz-Planillo R, Nuñez G. The inflammasome: a caspase-1-activation platform that regulates immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2009; 10:241–247. [CrossRef]

- Chan AH, Schroder K. Inflammasome signaling and regulation of interleukin-1 family cytokines. J Exp Med. 2020;217: e20190314. [CrossRef]

- Libby P. Targeting inflammatory pathways in cardiovascular disease: the inflammasome, Interleukin-1, Interleukin-6 and BEYOND. Cells. 2021; 10:951. [CrossRef]

- Kocatürk B, Lee Y, Nosaka N, Abe M, Martinon D, Lane ME, Moreira D, Chen S, Fishbein MC, Porritt RA, Franklin BS, Noval Rivas M, Arditi M. Platelets exacerbate cardiovascular inflammation in a murine model of Kawasaki disease vasculitis. JCI Insight. 2023 Jul 24;8(14):e169855. [CrossRef]

- Rolfes V, Ribeiro LS, Hawwari I, Böttcher L, Rosero N, Maasewerd S, Santos MLS, Próchnicki T, Silva CMS, Wanderley CWS, et al. Platelets fuel the inflammasome activation of innate immune cells. Cell Rep. 2020; 31:107615. [CrossRef]

- Man SM, Kanneganti TD. Regulation of inflammasome activation. Immunol Rev. 2015 May;265(1):6-21. [CrossRef]

- Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Inflammasome activation and regula- tion: toward a better understanding of complex mechanisms. Cell Discov. 2020; 6:36. [CrossRef]

- Grebe A, Hoss F, Latz E. NLRP3 Inflammasome and the IL-1 pathway in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2018; 122:1722–1740. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Feuerstein GZ, Clark RK, Yue TL. Enhanced leucocyte adhesion to interleukin-1 beta stimulated vascular smooth muscle cells is mainly through intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Cardiovasc Res. 1994 Dec;28(12):1808-14. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Feuerstein GZ, Gu JL, Lysko PG, Yue TL Interleukin-1 beta induces expression of adhesion molecules in human vascular smooth muscle cells and enhances adhesion of leukocytes to smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 1995; 115:89–98. [CrossRef]

- González-Carnicero Z, Hernanz R, Martínez-Casales M, Barrús MT, Martín Á, Alonso MJ. Regulation by Nrf2 of IL-1β-induced inflammatory and oxidative response in VSMC and its relationship with TLR4. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Mar 2; 14:1058488. eCollection 2023. [CrossRef]

- Stackowicz J, Gaudenzio N, Serhan N, Conde E, Godon O, Marichal T, Starkl P, Balbino B, Roers A, Bruhns P, et al. Neutrophil-specific gain- of-function mutations in Nlrp3 promote development of cryopyrin- associated periodic syndrome. J Exp Med. 2021;218: e20201466. [CrossRef]

- Vanaja SK, Rathinam VA, Fitzgerald KA. Mechanisms of inflammasome activation: recent advances and novel insights. Trends Cell Biol. 2015 May;25(5):308-15. [CrossRef]

- Mishra N, Schwerdtner L, Sams K, Mondal S, Ahmad F, Schmidt RE, Coonrod SA, Thompson PR, Lerch MM, Bossaller L. Cutting edge: protein arginine deiminase 2 and 4 regulate NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1β maturation and ASC speck formation in macrophages. J Immunol. 2019; 203:795–800. [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, Dagna L, Martinod K, Dixon DL, Van Tassell BW, Dentali F, Montecucco F, Massberg S, Levi M, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021; 21:319–329. [CrossRef]

- Soehnlein O, Libby P. Targeting inflammation in atherosclerosis - from experimental insights to the clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021; 20:589–610. [CrossRef]

- Libby P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2021; 592:524– 533. [CrossRef]

- Nording HM, Seizer P, Langer HF. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. Front Immunol. 2015 Mar 6;6:98. eCollection 2015. [CrossRef]

- Lievens D, von Hundelshausen P. Platelets in atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2011 Nov;106(5):827-38. [CrossRef]

- Blann AD, Nadar SK, Lip GY. The adhesion molecule P-selectin and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2003 Dec;24(24):2166-79. [CrossRef]

- Wagner DD, Heger LA. Thromboinflammation: From Atherosclerosis to COVID-19. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022 Sep;42(9):1103-1112. [CrossRef]

- Woollard KJ, Chin-Dusting J. Therapeutic targeting of p-selectin in atherosclerosis. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2007 Mar;6(1):69-74. [CrossRef]

- Shim CY, Liu YN, Atkinson T, Xie A, Foster T, Davidson BP, Treible M, Qi Y, López JA, Munday A, Ruggeri Z, Lindner JR. Molecular Imaging of Platelet-Endothelial Interactions and Endothelial von Willebrand Factor in Early and Mid-Stage Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015 Jul;8(7):e002765. [CrossRef]

- Methia N, André P, Denis CV, Economopoulos M, Wagner DD. Localized reduction of atherosclerosis in von Willebrand factor-deficient mice. Blood. 2001;98:1424–1428. [CrossRef]

- Doddapattar P, Dev R, Jain M, Dhanesha N, Chauhan AK. Differential Roles of Endothelial Cell-Derived and Smooth Muscle Cell-Derived Fibronectin Containing Extra Domain A in Early and Late Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020 Jul;40(7):1738-1747. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi C, Khan MM, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. ADAMTS13 reduces vascular inflammation and the development of early atherosclerosis in mice. Blood. 2012; 119:2385–2391. [CrossRef]

- Jin SY, Tohyama J, Bauer RC, Cao NN, Rader DJ, Zheng XL. Genetic ablation of Adamts13 gene dramatically accelerates the formation of early atherosclerosis in a murine model. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012; 32:1817–1823. [CrossRef]

- Franck G, Mawson TL, Folco EJ, Molinaro R, Ruvkun V, Engelbertsen D, Liu X, Tesmenitsky Y, Shvartz E, Sukhova GK, et al. Roles of PAD4 and NETosis in experimental atherosclerosis and arterial injury: implica- tions for superficial erosion. Circ Res. 2018; 123:33–42. [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Roig C, Braster Q, Wichapong K, Lee EY, Teulon JM, Berrebeh N, Winter J, Adrover JM, Santos GS, Froese A, et al. Externalized histone H4 orchestrates chronic inflammation by inducing lytic cell death. Nature. 2019; 569:236–240. [CrossRef]

- Violi F, Cangemi R, Calvieri C. Hospitalization for pneumonia and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2015 May 5;313(17):1753. [CrossRef]

- Dalager-Pedersen M, Søgaard M, Schønheyder HC, Nielsen H, Thomsen RW. Risk for myocardial infarction and stroke after community-acquired bacteremia: a 20-year population-based cohort study. Circulation. 2014; 129:1387–1396. [CrossRef]

- Johnston WF, Salmon M, Su G, Lu G, Stone ML, Zhao Y, Owens GK, Upchurch GR Jr, Ailawadi G. Genetic and pharmacologic disruption of interleukin-1β signaling inhibits experimental aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013 Feb;33(2):294-304. [CrossRef]

- Popa-Fotea NM, Ferdoschi CE, Micheu MM. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023 Aug 3;10:1200341. eCollection 2023. [CrossRef]

- Westerterp M, Fotakis P, Ouimet M, Bochem AE, Zhang H, Molusky MM, Wang W, Abramowicz S, la Bastide-van Gemert S, Wang N, Welch CL, Reilly MP, Stroes ES, Moore KJ, Tall AR. Cholesterol Efflux Pathways Suppress Inflammasome Activation, NETosis, and Atherogenesis. Circulation. 2018 Aug 28;138(9):898-912. [CrossRef]

- Parzy G, Daviet F, Puech B, Sylvestre A, Guervilly C, Porto A, Hraiech S, Chaumoitre K, Papazian L, Forel JM. Venous Thromboembolism Events Following Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Based on CT Scans.Crit Care Med. 2020 Oct;48(10):e971-e975. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal K, Keller SP, Akkanti B, Bime C, Loyalka P, Cheema FH, Zwischenberger JB, El Banayosy A, Pappalardo F, Slaughter MS, Slepian MJ. Advanced Pulmonary and Cardiac Support of COVID-19 Patients: Emerging Recommendations From ASAIO-a Living Working Document. Circ Heart Fail. 2020 May;13(5):e007175. [CrossRef]

- Khoo BZE, Lim RS, See YP, Yeo SC. Dialysis circuit clotting in critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection. BMC Nephrol. 2021 Apr 20;22(1):141. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Tecson KM, McCullough PA. Endothelial dysfunction contributes to COVID-19-associated vascular inflammation and coagulopathy. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020 Sep 30;21(3):315-319. [CrossRef]

- Levy JH, Iba T, Olson LB, Corey KM, Ghadimi K, Connors JM. COVID-19: Thrombosis, thromboinflammation, and anticoagulation considerations. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021 Jul;43 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):29-35. [CrossRef]

- Nicolai L, Leunig A, Brambs S, Kaiser R, Weinberger T, Weigand M, Muenchhoff M, Hellmuth JC, Ledderose S, Schulz H, Scherer C, Rudelius M, Zoller M, Höchter D, Keppler O, Teupser D, Zwißler B, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Kääb S, Massberg S, Pekayvaz K, Stark K. Immunothrombotic Dysregulation in COVID-19 Pneumonia Is Associated With Respiratory Failure and Coagulopathy. Circulation. 2020 Sep 22;142(12):1176-1189. Epub 2020 Jul 28. [CrossRef]

- Group RC. Aspirin in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2022; 399:143–51. [CrossRef]

- Investigators R-CWCftR-C, Bradbury CA, Lawler PR, Stanworth SJ, McVerry BJ, McQuilten Z, Higgins AM, Mouncey SJ, Al-Beidh F, Rowan KM, Berry LR, et al. Effect of antiplatelet therapy on survival and organ support-free days in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a random- ized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022; 327:1247–59. [CrossRef]

- Kander T. Coagulation disorder in COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e630–e632. [CrossRef]

- Sinkovits G, Réti M, Müller V, Iványi Z, Gál J, Gopcsa L, Reményi P, Szathmáry B, Lakatos B, Szlávik J, Bobek I, Prohászka ZZ, Förhécz Z, Mező B, Csuka D, Hurler L, Kajdácsi E, Cervenak L, Kiszel P, Masszi T, Vályi-Nagy I, Prohászka Z. Associations between the von Willebrand Factor-ADAMTS13 Axis, Complement Activation, and COVID-19 Severity and Mortality. Thromb Haemost. 2022 Feb;122(2):240-256. [CrossRef]

- Cugno M, Meroni PL, Gualtierotti R, Griffini S, Grovetti E, Torri A, Lonati P, Grossi C, Borghi MO, Novembrino C, Boscolo M, Uceda Renteria SC, Valenti L, Lamorte G, Manunta M, Prati D, Pesenti A, Blasi F, Costantino G, Gori A, Bandera A, Tedesco F, Peyvandi F. Complement activation and endothelial perturbation parallel COVID-19 severity and activity. J Autoimmun. 2021 Jan; 116:102560. [CrossRef]

- Pascreau T, Zia-Chahabi S, Zuber B, Tcherakian C, Farfour E, Vasse M. ADAMTS 13 deficiency is associated with abnormal distribution of von Willebrand factor multimers in patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2021; 204:138–140. [CrossRef]

- Afzali B, Noris M, Lambrecht BN, Kemper C. The state of comple- ment in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022; 22:77–84. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Haematology. COVID-19 coagulopathy: an evolving story. Lancet Haematol. 2020 Jun;7(6):e425. [CrossRef]

- Comer SP, Cullivan S, Szklanna PB, Weiss L, Cullen S, Kelliher S, Smolenski A, Murphy C, Altaie H, Curran J, O'Reilly K, Cotter AG, Marsh B, Gaine S, Mallon P, McCullagh B, Moran N, Ní Áinle F, Kevane B, Maguire PB; COCOON Study investigators. COVID-19 induces a hyperactive phenotype in circulating platelets. PLoS Biol. 2021 Feb 17;19(2):e3001109. eCollection 2021 Feb. [CrossRef]

- Yatim N, Boussier J, Chocron R, Hadjadj J, Philippe A, Gendron N, Barnabei L, Charbit B, Szwebel TA, Carlier N, et al. Platelet activation in criti- cally ill COVID-19 patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11:113. [CrossRef]

- Gue YX, Pula G, Lip GYH. Crizanlizumab: A CRITICAL Drug During a CRITICAL Time? JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021 Dec 27;6(12):946-947. eCollection 2021 Dec. [CrossRef]

- Barnes BJ, Adrover JM, Baxter-Stoltzfus A, et al. Targeting potential drivers of COVID-19: Neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2020;217(6):e20200652. [CrossRef]

- Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss BM, Nguyen JX, Marques MB, Monestier M, Toy P, Werb Z, Looney MR. Platelets induce neutrophil ex- tracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2012; 122:2661–2671. [CrossRef]

- Thomas GM, Carbo C, Curtis BR, Martinod K, Mazo IB, Schatzberg D, Cifuni SM, Fuchs TA, von Andrian UH, Hartwig JH, et al. Extracellular DNA traps are associated with the pathogenesis of TRALI in humans and mice. Blood. 2012; 119:6335–6343. [CrossRef]

- Radermecker C, Detrembleur N, Guiot J, Cavalier E, Henket M, d’Emal C, Vanwinge C, Cataldo D, Oury C, Delvenne P, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps infiltrate the lung airway, interstitial, and vascular com- partments in severe COVID-19. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20201012. [CrossRef]

- Aymonnier K, Ng J, Fredenburgh LE, Zambrano-Vera K, Münzer P, Gutch S, Fukui S, Desjardins M, Subramaniam M, Baron RM, Raby BA, Perrella MA, Lederer JA, Wagner DD.. Inflammasome activation in neutrophils of patients with severe COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2022; 6:2001–2013. [CrossRef]

- Ni H, Denis CV, Subbarao S, Degen JL, Sato TN, Hynes RO, Wagner DD. Persistence of platelet thrombus formation in arterioles of mice lacking both von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen. J Clin Invest. 2000; 106:385–392. [CrossRef]

- Ammollo C.T., Semeraro F., Xu J., Esmon N.L., Esmon C.T. 2011. Extracellular histones increase plasma thrombin generation by impairing thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 9:1795–1803. [CrossRef]

- Brill A., Fuchs T.A., Chauhan A.K., Yang J.J., De Meyer S.F., Köllnberger M., Wakefield T.W., Lämmle B., Massberg S., Wagner D.D. 2011. von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet adhesion is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mouse models. Blood. 117:1400–1407. [CrossRef]

- von Brühl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, Chandraratne S, Konrad I, Lorenz M, Khandoga A, Tirniceriu A, Coletti R, Köllnberger M, et al. Monocytes, neu- trophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous throm- bosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012; 209:819–835. [CrossRef]

- Allam R, Scherbaum CR, Darisipudi MN, Mulay SR, Hägele H, Lichtnekert J, Hagemann JH, Rupanagudi KV, Ryu M, Schwarzenberger C, Hohenstein B, Hugo C, Uhl B, Reichel CA, Krombach F, Monestier M, Liapis H, Moreth K, Schaefer L, Anders HJ. Histones from dying renal cells aggravate kidney injury via TLR2 and TLR4. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Aug;23(8):1375-88. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Zhang X, Monestier M, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones are mediators of death through TLR2 and TLR4 in mouse fatal liver injury. J Immunol. 2011; 187:2626–2631. [CrossRef]

- Colicchia M, Perrella G, Gant P, Rayes Novel mechanisms of thrombo-inflammation during infection: spotlight on neutrophil extracellular trap-mediated platelet activation. J.Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2023 Mar 11;7(2):100116. eCollection 2023 Feb. [CrossRef]

- Damiana T, Damgaard D, Sidelmann JJ, Nielsen CH, de Maat MPM, Münster AB, Palarasah Y. Citrullination of fibrinogen by peptidylarginine deiminase 2 impairs fibrin clot structure. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Feb; 501:6-11. [CrossRef]

- Osca-Verdegal R, Beltrán-García J, Paes AB, Nacher-Sendra E, Novella S, Hermenegildo C, Carbonell N, García-Giménez JL, Pallardó FV. Histone Citrullination Mediates a Protective Role in Endothelium and Modulates Inflammation. Cells. 2022 Dec 15;11(24):4070. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).