1. Introduction

Over twenty years of scholarship on the neoliberalism of higher education have captured its features, such as the corporate university, the entrepreneurial university, and the neoliberal university [1,2]. In neoliberal contexts, funding allocations for higher education have typically focused on competitive mechanisms. While higher education has been funded directly by the state, it is usually seen as serving public goods, such as a reduction in inequality and an increase in social mobility. Therefore, related public goods policy initiatives seek to reframe higher education as interrelated with the well-being of society [3–5]. Several governments have adopted the format of a national strategy or development plan by setting out national objectives for better alignment with higher education institutes, for instance, Ireland, the Netherlands, Finland, and New Zealand [6]. On neoliberal campuses, it is overemphasized competition and evaluation. This phenomenon has caused numerous criticisms [7–10]. This study may stand at a turning point to provide a better understanding of the transformation from neoliberalism to public goods in higher education.

In addition, Eryaman & Schneider argue research associations can promote the use of research to service public goods [11]. Some nationwide or international associations have focused on this issue; for example, the Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) identifies its vision of enhancing public goods by promoting, supporting, and improving research [12]; the American Educational Research Association (AERA) recognizes that promotion of research to serve the public goods as the fundamental responsibility of the association [13]. Based on the discussion, it has become a persistent issue that public resources transfer into higher education properly for public goods purposes. Surprisingly, much less attention has been paid to verifying the effect of the allocation of resources for public goods in higher education settings. This study provided an alternative way to detect specific funding allocation for public goods purposes, which can gain a deeper understanding of this issue.

The funding policies in higher education are varied, for example, the UK has shown differently from those of Germany, Italy, and the United States. Even the similar higher education system in Japan and South Korea have specific considerations. Taiwan is part of a different socio-political constellation, based on and driven by different value sets than the neoliberal societies. Taking Taiwan’s Higher Education Sprout Project (HESP) as an example, this study explores how far the specific funding allocation can be transferred with the public goods implemented in higher education. HESP (from 2018 to 2022 stage I) initiated in 2017, it intends to transfer public goods as a policy-driven tool for higher education institutes [14,15]. It is a different direction leading to higher education aligned with the policy. In this study, we argued that higher education for public goods purposes should consider balancing their teaching and research, caring for disadvantaged students to increase social mobility, and balancing global competition and local needs in terms of fulfilling university social responsibility. It also that the higher education system can be expected to sustainable development under the specific funding allocation mechanism.

We wonder when the funding allocation for public goods in neoliberal higher education will happen. This study, focusing on specific policy implementation, can provide an example for enhancing knowledge in this field. With this purpose in mind, this paper proceeds as follows: First, we review funding allocation theories, meanings of public goods, and their transformation logic in higher education. Meanwhile, the focus will be on the policy initiative of HESP as an example of seeking for public goods. Second, the method section will address the data collection and statistical processes conducted to verify the logic of funding allocation. Third, the effect of funding allocation in HESP will be examined with different types of higher education institutes and their structural relationships. Fourth, the discussions will focus on what challenges are confronted in the higher education system when the public goods policy is intended to be implemented. Finally, conclusions will be drawn and suggestions will be provided for higher education.

This study demonstrates that transforming the public good through special funding can play a critical role in neoliberal higher education regardless the sectors. If the transformation model- ITO (input, transform, and outcome) works well, it implies that the public goods initiatives can be implemented in higher education. The findings may encourage that higher education institutes commit to achieving great progress in expanding learning opportunities for all, as UNESCO’s SDGs propose in higher education. With fitting funding for public good purposes, higher education can find ways to respond to the challenges of local and global issues.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Funding Allocation

Funding allocation refers to a process in which a

system or a government transfers resources among the various intended

activities its aims will achieve. There are various funding allocation

theories, and the evidence-based model is one of them to ensure that funding is

invested in the target groups of the greatest need [16].

Management theory is primarily devoted to planning and budgeting for the use of

resources [17]. The resource allocation

process is assumed to be an exemplary process for theory-based instruction to

guide the choices of management. Planning theory has seen management as

providing aggregate goals integrated into sub-goals for each part of the organization

[18,19].

Moreover, critical planning theory is associated

with power, equity, knowledge construction, and related issues to test

professional concepts against the real world [20–22].

Therefore, strategic planning must be systematic, it involves choosing specific

priorities and making decisions about short-term and long-term goals [23,24]. Hoch argued that the theory was only deemed

helpful for a limited number of specialized scenarios, not on a day-to-day

basis [25]. In this sense, applying planning

theory for specific funding allocation in higher education needs more empirical

investigations of actual planning in many different settings. As a national

strategy plan, HESP should confirm its policy effect.

2.2. Meanings of Public Goods in Higher Education

The notion of public goods comes from economics and

is rooted in neoclassical economic theories. Public goods are often assumed

that it is non-competitive and non-excludable [26].

Previous studies argued it is impossible to exclude any individual from

consuming the good [26,27]. The concept of

public goods is never static as it continually is restated by various discourse

communities [28,29]. For example, Daviet,

claimed "a common good is a collective decision that involves the state,

the market, and civil society" [30] (p.

8); Nixon identified the public good as "a good that, being more than the

aggregate of individual interests, denotes a common commitment to social

justice and equality" [31] (p. 1).

Previous studies have shown that the economic conception of public goods has

extended to social and other contexts. Daviet argued how well the economic

conception of public goods provides a fundamental basis for understanding

education's social, cultural, and ethical dimensions [30].

In educational contexts, Locatelli suggested that

the framework of education as a public good and a common good may be seen as a

sort of continuum in line with the aim of developing democratic political

institutes that enable citizens to have a more extraordinary voice in the

decision process [32]. Eryaman and Schneider

indicated “a public good commitment necessitates a mutual understanding

concerning the common goal of public education, an obligation to social justice

and equality, and a focus on that provides learners with the skills needed for

a meaningful role as a citizen” [11] (p. 8).

UNESCO argued that education might confront the weakening of public goods under

the alliance of scientism and neo-liberalism in the report “Rethinking

Education” [5] (p. 78). Regarding higher

education systems, public goods imply various meanings in different settings.

As Marginson’s discussion [33–35], we may

assume that higher education is intrinsically neither a private nor a public,

nor a common good. In addition, “it is potentially rivalrous or non-rivalrous

and potentially excludable or non-excludable, which means that, being nested

into wider social and cultural settings, higher education as a good is policy

sensitive and consequently varies by time and place” [36]

(p. 1051). Hence, it is reasonable to argue that it belongs to the category of

quasi-public goods in China [37]. Previous

studies have focused on conceptual discussions in public good contexts, such as

Hazelkorn and Gibson’s public goods and public policy [6]; Szadkowsk's conceptual approach [38]. Theoretical discussions provide broader

thinking to explore this topic. In the substantive dimension, this study

assumes that public goods initiatives in higher education settings can provide

learners with the skills for playing a citizen role in the well-being of

society, for example, quality education for the young generation, innovative

research, and novel technologies for a better life.

2.3. Transferring Public Goods into Neoliberal Higher Education

Previous studies indicated that the present work on

neoliberal higher education originated from a critical political economy

approach [39,40]. Various researchers pointed

out that academic communities are experiencing the phenomena, often referred to

as ‘academic capitalism’ [41–43]; instead as

the ‘enterprise university’ [44]; or modeled

by a new set of parameters, for example, academic performance, accountability,

rankings, competitive funding schemes, and so on. The ongoing neoliberal

transformation of higher education has influenced the university and everyday

academic life [10]. These phenomena in higher

education are deeply embedded in a market-driven managerial logic. In contrast,

some researchers have emphasized the public contractual funding of universities

as the main lever of market-oriented reforms [45–47].

The market-oriented restructuring emerged in public

research universities in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United

States following the decline of block grants and funding. The perspective has

emerged that the government needs to decide what outcome of public goods is

appropriate for society. Contemporary higher education seeks more conformable

models under neoliberal times. The idea that universities have a mission to

serve society has long been integral to the public imagination regarding higher

education [48]. Public engagement policies in

the UK are older than that of most governments. Governments’ initiated policies

have emerged, for example, shaping the higher education landscape in terms of

outcomes, management, and governance of institutes in Ireland; formulating a

National Research Agenda involving a coalition of regular universities,

universities of applied sciences, university medical centers, national research

organizations, and industries in the Netherlands. Moreover, the EU agenda for

higher education and the new global Education 2030 are committed to promoting

equitable, affordable, and increased access to quality higher education [4,5].

In Asia, during the last 20 years, public or common

goods have also triggered various discussions on higher education in China [37]. Huang and Horiuchi addressed the public goods

of internationalizing higher education in Japan [49];

despite the acceptance of the concept of public goods, changes and reforms in

the system have been dominated by demands from business and industry. In the

international context, the related studies provide various examples of public

goods initiatives in higher education.

2.4. Examples of Funding Allocations from Neoliberal Schemes to Public Goods

Two decades ago, the funding allocation in higher

education was based on a competitive mechanism. The Ministry of Education in

Taiwan has implemented two significant initiatives to enhance the quality of

higher education, namely, the Aim for the Top University Plan [50,51] and the Program for Encouraging Teaching

Excellence for universities and technological universities [14]. One focuses on lifting research performance;

the other focuses on better teaching quality. The specific funds for selected

higher education institutes are based on competitive schemes. Typically, these

kinds of funding allocations are based on the neoliberal scheme.

In 2018, a total of 157 higher education institutes

were funded by the HESP. The government allocated NT$ 17.37 billion for the

first year of the HESP; a total of 65% (NT$ 11.37 billion) was allocated to the

first part of the project, which focused on the quality of teaching and

universities' social responsibility. In addition, 35% (NT$ 6 billion) was

apportioned to the second part, which aimed to enhance the global

competitiveness of universities in terms of pursuing quality research [15].

Analyzing the public goods transformation, we found

the first part of the HESP is composed of the following four components: (a)

promoting teaching innovation and learning effectiveness; (b) enhancing the

publicness of higher education, including financial openness and promoting

social mobility; (c) upholding university’s social responsibility; (d)

developing unique characteristics of universities. The second part of HESP

focuses on pursuing leading international status for selected universities and

research centers. The selected universities for global Taiwan includes National

Taiwan University (NTU), National Tsing Hua University (NTHU), National Chiao

Tung University (NCTU), and National Chen Kung University (NCKU). It revealed

that the funding mechanism has transformed into a non-competition orientation.

There is NT$5.3 billion for the second part of

HESP, including NT$4.0 billion for leading universities and NT$1.3 billion for

research centers [14,15]. In addition, the

Ministry of Education provides NT$2.57 billion for higher education

institutions to implement local concerning projects and support disadvantaged

students. The total funding from the Ministry of Education is NT$16.67 billion.

The Ministry of Science and Technology provides another NT$0.7 billion to

enhance the HESP. The details of the funding scheme in HESP are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Funding allocation scheme in HESP (unit: NT$ billion).

Table 1.

Funding allocation scheme in HESP (unit: NT$ billion).

| HESP |

Funding (MOE) |

Categories |

Funding (MOST) |

| First part |

65% (11.37) |

80% allocated based on the quality of the project |

0 |

| 20% based on the institution's scale |

0 |

Second part

(Global Taiwan) |

35% (5.3) |

4.0 for leading university |

0.7 |

| 1.3 for research centers |

|

| Total |

16.67 |

|

0.7 |

3. Materials and Methods

To explore the effect of HESP, this study employs a mixed method to clarify the issue of funding allocation for public good transformation. The research framework, data collection, and statistical analysis are addressed as follows.

3.1. Research Framework

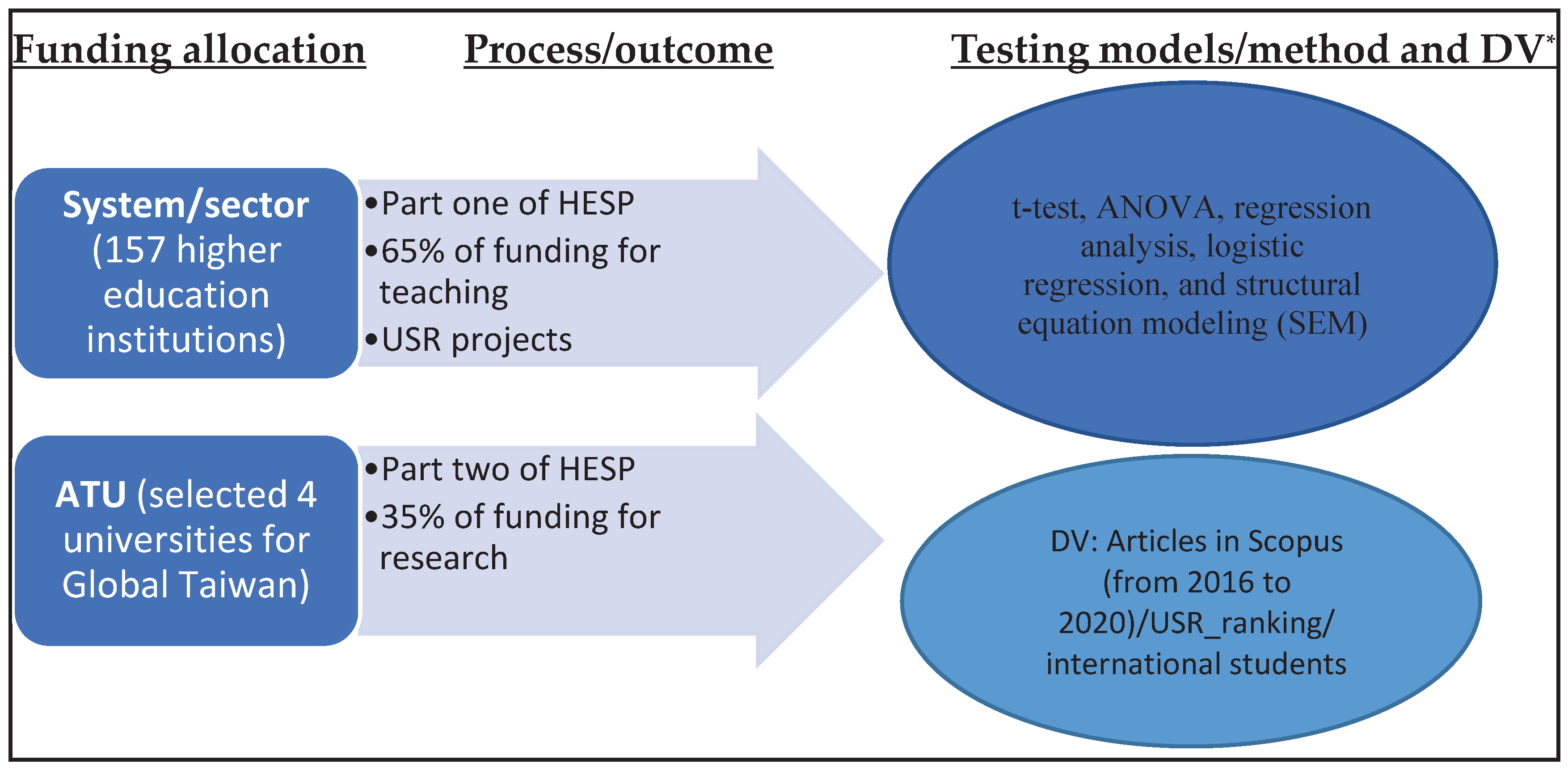

This study conducted an input, transformation, and outcome (ITO) model to explore the effect of funding transformation for lifting the quality of teaching, research, and public goods in higher education. The data were collected from the Ministry of Education in Taiwan and Scopus database based on the targeted higher education institutes. To conduct the statistical tests, we defined the related variables in the ITO model as follows:

3.1.1. Input Funding (I)

It refers to funding at HESP for teaching, research, and public goods purposes. The variables in the input funding include funding for HESP, funding per student, and funding for teaching.

“Funding_in_HESP” refers to the funds for 157 institutes in the target country. The total amount is NT$15.34 billion (excluding the specific funding for selected research centers and the funding supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology).

“Funding_per_student” refers to the number of funds for students, which is the fund in each institute divided by the number of undergraduate students.

“Funding_for_teaching” refers to the fund being for teaching purposes only. The calculation considered the number of funds for teaching divided by the number of undergraduate students in each institute.

3.1.2. Transform Process (T)

It refers to human resources and the mechanism of transformation. The related variables in the transformation process include full-time faculty, international faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students.

“Full_time_faculty” refers to the full-time faculty that the institute hired.

“International_faculty” refers to the full-time international faculty that the institute hired.

“Graduate” refers to the number of graduate students enrolled in the institute.

“Undergraduate” refers to the number of undergraduate students enrolled in the institute.

3.1.3. Expected Outcomes (O)

This study defines the expected outcomes as academic performance, USR_ranking, and international students in each institute.

"Academic-performance" refers to the total number of journal articles for each institute in the Scopus database from 2011 to 2019. These articles have been assumed to relate to the research that will promote social well-being or solve global issues and implies how the institutes face global competition and global issues.

"USR_ranking" refers to the projects for implementing social responsibility to fulfill local needs. This variable has been transferred on a ranking basis to compare the institute's engagement. The ranking was counted by the number of USR projects and their funding.

“International_students" refers to the number of international students enrolled in the institutes representing the global competition.

We consider the "System", which refers to the two different tracks of institutes in terms of university and technological university systems in the target higher education; “Sector” refers to the public and private institutes. The research framework is presented in

Figure 1. The research questions to answer are as follows:

a. What are the influential factors of funding allocation in the HESP?

b. Did the funding allocation in HESP eliminate the diversity between the system and sector for public goods purposes?

c. Did a significant effect of public goods transformation on the target higher education system?

d. Can we set better strategies by way of specific funding allocation towards public goods in higher education?

3.2. Data Collection

This study considered the students, faculty, and funding data in the 157 higher education institutes in Taiwan. The number of undergraduate and graduate students, international students, and faculty members was collected from the databank of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan. Among these institutes, 50 institutes (31.85%) belonged to the public sector, and 107 (68.15%) belonged to the private sector. The university system consists of 71 institutes (45.22%), while 86 institutes (54.78%) are classified under the technological system. The "full-time faculty" range is from 9 to 2,045, and the range of "Academic_performance" is from 44 to 127,006 articles from 2011-2019. The funding and USR data are based on a document published by the Ministry of Education. The institutional "academic_performance" data are based on Scopus databank. Most of the data belongs to secondary data. We integrated and transformed the data to fit the requirements of quantitative approaches.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

In this study, SPSS (the statistical package for social science), AMOS (Analysis of moment structure) and PLS-SEM (Partial least square SEM) were used to analyze statistic data. We employed t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), regression analyses, and structural equation modeling (SEM) to transform related evidence to support our arguments. First, ANOVA was used to determine the group differences with their means and variances. Considering the equal variances assumed or not assumed in the testing model, we conducted Levene's test to justify the equality of variance in SPSS. When Levene's statistic is not significant, it implies the variances in the groups are homogeneity. The Bonferroni test will be used to verify the group differences; otherwise, we will select the Dunnett T3 test [52]. Second, this study compared two different models to check the logic of funding with regression analyses. One includes all the possible variables to interpret the funding in the model. The other excludes the selected top four universities to determine which variables critically influence funding without considering academic excellence purposes. The dependent variables are "Funding_in_HESP" (unit: NT

$10000) and "Funding_per_student." The related independent variables will be selected by the stepwise method to build fitted regression models in these models. Third, logistic regression was used to determine the effects of funding allocation in HESP for the sector and different higher education tracks. Sector and track of universities are coded categorical variables and as dependent variables in the logistic models. Logistic regression estimates the probability of an event occurring, such as voted or did not vote, based on a given dataset of independent variables. Since the outcome is a probability, the dependent variable is bound between 0 and 1. In logistic regression, a logit transformation is applied to the odds—that is, the probability of success divided by the probability of failure. The odds ratio (OR) was calculated to reflect the effect of funding allocation in HESP with the sector and system in the current higher education institutes. The OR was calculated according to the following formula with conditions A and B [53]:

We also considered the stepwise method with more complicated models in logistical regression. The significant tests set the critical value: as α = .05.

Finally, SEM was used to verify the effect of funding allocation in the HESP. Typically, SEM was employed to model the relationship between measured and latent variables or between multiple latent variables. Since multiple regression is restricted to examining a single relationship at a time, SEM can estimate a series of interrelated dependent relationships simultaneously. This technique enables researchers to quickly set up and reliably test hypothetical relationships among theoretical constructs and those between the constructs and their observed indicators. Moreover, SEM is more effective than multiple regressions in parsimonious model testing. It is employed to find the best-fitting model [54].

We select funding for institutes and funding per student, and funding for teaching as formats of funding allocation in HESP; Full-time faculty, International faculty, undergraduate students, and graduate students are human resources variables that represent the transformation process. Academic performance, USR, and international students as expected outcome variables. IBM AMOS was used to verify the proposed model. We assume the following null hypotheses for testing:

Null hypothesis 1: There is no effect of input funding on expected outcomes;

Null hypothesis 2: There is no effect of input funding on the transformation process;

Null hypothesis 3: There is no effect of transformation process on expected outcomes;

Null hypothesis 4: The input funding will not, through the transformation process, impact expected outcomes.

This study considered the overall model fit in SEM using the following goodness-of-fit indices, including Chi-square minimum (CMIN), the ratio of Chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/df < 5.0), goodness-of-fit index (GFI > 0.90), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI > 0.90), parsimonious goodness-of-fit index (PGFI > 0.50), root-mean-square residual (RMR < 0.08), and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC = χ2 – 2 × df) [

55,

56,

57,

58]. Following Shrout & Bolger’s suggestion [

59], the bootstrap method was used to estimate the mediation effect in this study. We selected resampling 2000 for bootstrapping. When Z > 1.96 (Z = point estimate/standardized error), implying that there is a mediation effect among the latent variables [

60,

61]. Considering the differences might exist in public and private sectors, we verify the effect with PLS-SEM. In PLS-SEM model, we will check Cronbach alpha, average extracted variance (AVE), composite reliability (CR), critical path and its coefficient [

62,

63,

64].

4. Results

4.1. Influential Factors in HESP Allocation

This study considered a regression model with 157 institutes to interpret the logic of funding allocation in the HESP, by checking the total funding scheme and funding by each undergraduate student among these institutes. The proposed impact factors include undergraduate students, full-time faculty, international students, international faculty, and total articles on Scopus. The details of regression models are listed in

Table 2.

The regression model reveals that the funding of the HESP for each institute is based on the number of articles in Scopus due to the high relationships between “Funding_in_HESP” and “Academic_performnace". The R is 0.955 in terms of the articles in Scopus, which can explain 91.2% of the funding among these institutes. The finding reveals research focus may be overweight in HESP. Second, in considering the funding by each undergraduate student (Funding_per_student), this study found “Academic_performance” and “Full_time_faculty" were influential factors in interpreting the Funding_per_student in each institute (R = 0.773, R2 = 0.597). If the number of undergraduate students can reflect on the scale of institutes, the result reveals that the funding allocation in HESP needs to consider the scale of institutes properly. In our proposed regression models, the t values and their p reveal that the models are significant. Since the VIF is slim, there are no multi-collinearity problems when the variables fit in the models.

4.2. The Logic of Funding Allocation in HESP

The result reveals the average funding for each higher education institute is NT

$9770.52 (unit: NT

$10000). Regarding the sector, this study found the average funding for public universities shared NT

$20297.72, while funding for the private universities & colleges only shared NT

$4851.27 (

t = 4.686,

p = 0.000). Regarding the system, the average funding for universities shows the sharing of a more considerable amount than that of technological universities & colleges (NT

$15055.94 vs. NT

$5406.98) (

t = 3.011,

p = 0.003).

Table 3 shows that Funding_in_HESP, Funding_per_student, and Funding_for_teaching significantly differ between sector and system in the HESP. The finding reveals the only diversity shown in private technology groups that received less funding from HESP. Since the oversupply issue in higher education has confronted the higher education system, private technology institutes will threaten the declining birthrate in Taiwan. While the findings reveal that the policy intention for funding allocation in HESP and its practice existed a little gap, it is still acceptable considering the equality for most institutes.

4.3. Transformation Diversity between System and Sector

For balancing the system, the result of logistic regression reveals that both university and technological university systems can be explained by “Funding_in_HESP”, “Undergraduate”, “Full_time_faulty”, and “International_students” (R

2 = 0.45, AIC = 124.91). It implies that the four selected variables can explain the effect of the system with 45% of variances in the model. The results processed by the stepwise method in the logistical regression model are shown as follows:

Y' refers to the system, 1 is the university system, 2 is the technology system. The findings suggest that the university system is favored by HESP. While the significant odds ratio over 4 implies a strong influence, in this case, the odds ratios are slim (

Table 4).

An analysis of the effects of the sector shows that both the public and private sectors can be explained by the amount of funding and undergraduate students in the logistical regression model (R

2 = 0.3139, AIC = 152.34). It is:

The result reveals that the model only explained 31.39% of variances with funding and undergraduate students. The ratio of "Funding_in_HESP" for the public sector is 1.0002 for the private sector, and the odds ratio of "undergraduate" for the public sector is 0.9997 for the private sector. The findings reveal that the public and private sector gap is minimal.

4.3. Expected Outcome in Global Taiwan

The academic performance of Global Taiwan universities has shown declining from 2016 (10,322 journal articles) to 2018 (9,678 journal articles). In contrast, the HESP started in 2018, encouraging selected universities and steadily increasing their academic publications (see

Table 5).

4.4. Expected USR Implementation

There are 220 USR projects conducted in 116 institutes. It implies 549 proposals submitted for financial support, while only 40% of them were accepted in HESP. USR refers to university social responsibility, it is also reflected that the institute engaged in social development to fulfill local needs. The result reveals that the university system conducted 102 projects, while the other 118 were implemented in the technological university system. It also shows that 46.36% of the USR projects belong to the public sector, and the other 53.64% belong to the private sector. The change has shown more significant differences than it did before.

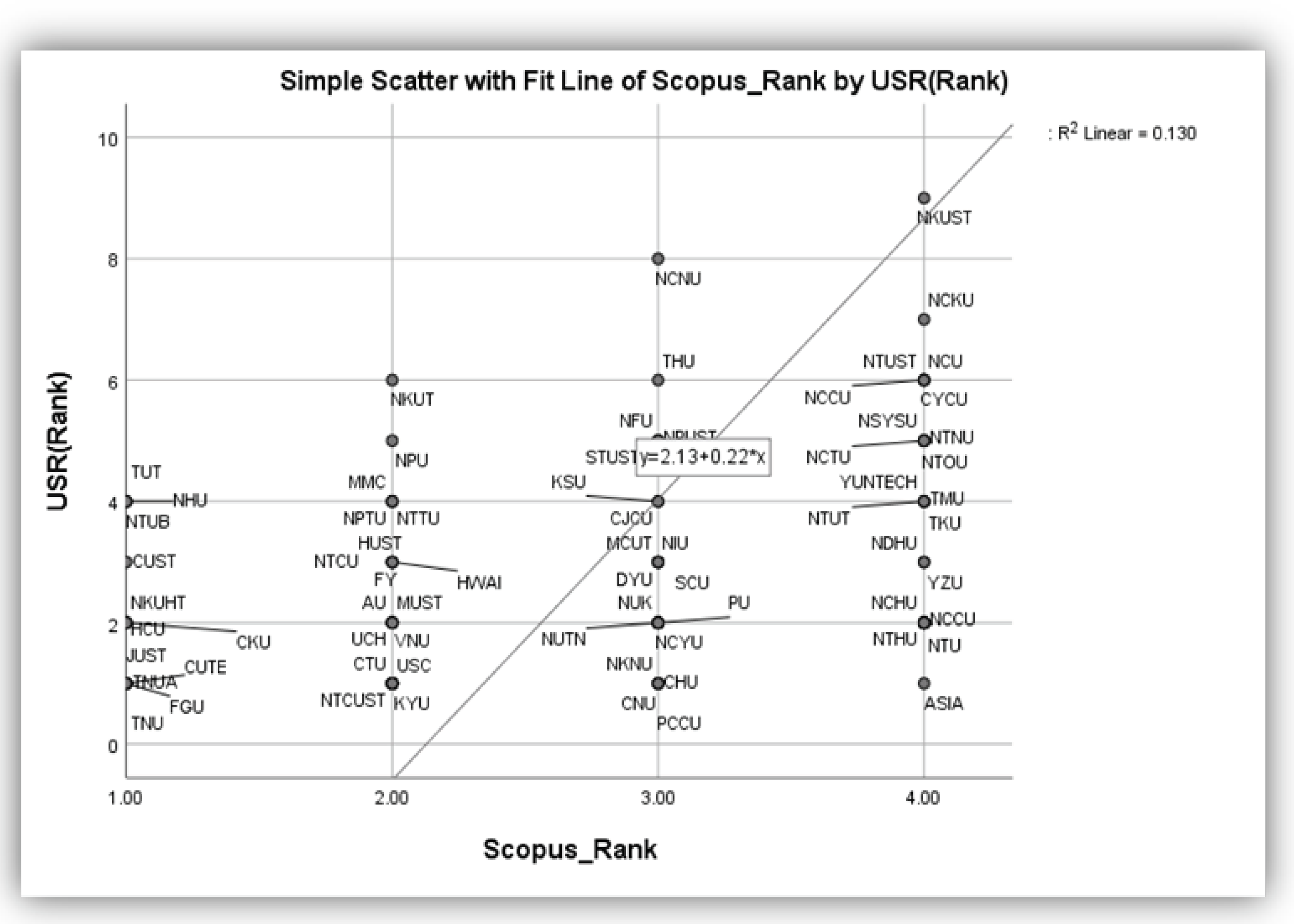

4.5. The Relationship of Academic Performance and USR

Figure 2 displays that academic performance (for global competition) and USR (local needs) implementation has a significant positive relationship among higher education institutes. We divided the number of articles into four groups (Q1 to Q4) in terms of Q4 being the best group, Q1 being the last group compared to their articles in Scopus. USR(Rank) refers to the funding received by ranking the institutes from 1-9 in HESP. It means that the more the special funding received, the stronger the relationship that the institutes will fulfill local development needs and global competition in the HESP framework. The result reveals that both expected outcomes positively correlate with balancing global competition and local needs (R

2 = 0.130,

p < 0.05).

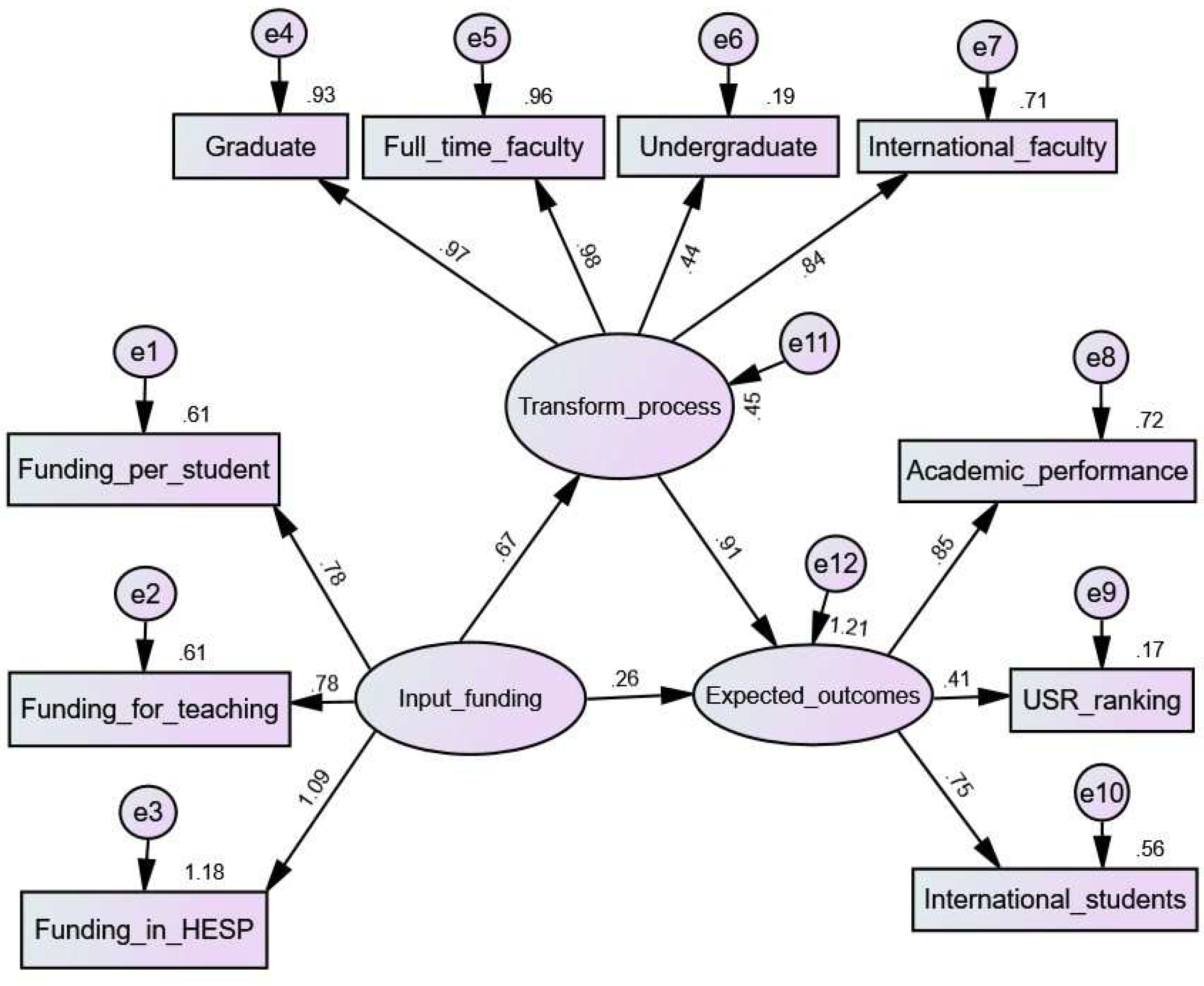

4.6. Testing ITO Model with SEM

This study employed the scale-free least squares (SLS) method to test the proposed model, it indicated that the CMIN was 144.943 and the degree of freedom was 29. The result reveals that the value of χ

2/df was 4.998, which implied an excellent fit (4.998 < 5.00). The related model-fit indices, for example, GFI, AGFI, and PGFI are, exceeded the acceptance levels (that is GFI = 0.956 > 0.90, AGFI = 0.920 > 0.90, and PGFI = 0.522 > 0.50 in the fitted SEM model). The RMR (root-mean-square residual) > 0.08, while AIC is 86.943 (AIC = χ

2 – 2 × df), it tended to be small. The estimated standardized coefficients are 0.256, 0.671, 0.910, and 0.614 in H1 to H4, respectively (see

Table 6). The results of the null hypotheses test are listed as follows:

Null hypothesis 1: There is no effect of input funding on expected outcomes (Rejected);

Null hypothesis 2: There is no effect of input funding on the transformation process (Rejected);

Null hypothesis 3: There is no effect of transformation process on expected outcomes (Rejected);

Null hypothesis 4: The input funding will not, through the transformation process, impact expected outcomes (Rejected).

Since the null hypotheses are rejected, the results suggest that the input funding in HESP and the transformation process have significantly impacted the expected outcomes.

Figure 3 displays the estimated structural relationship. It implies that the effects of transformation are significant.

4.7. Testing Mediation Effect

Based on

Table 6, the estimated coefficients and

p-values have shown they are significant in the SEM model (that is, if

p is less than 0.05, the estimated coefficients are valid). We found that the coefficient β1 (Input funding → Expected outcomes) is also significant (β1 = 0.256,

p = 0.002). β2 (Input funding → Transform process) is significant (β2 = 0.671,

p = 0.001), and β3 (Transform process → Expected outcomes) is significant (β3 = 0.910,

p = 0.000). Since the model demonstrates β2 * β3 > β1, the transform variables might exert a strong mediation effect in this model. We used a bootstrap method to estimate the model's mediation effect with 2,000 samples in AMOS. The result showed that the effect of mediation (Input funding → Transform process → Expected outcomes) was 0.614, and it was significant at the 0.05 level (

p = 0.000). The details of the indirect effect (mediation effect), direct effect and total effect,

p-values, and 95% confidence interval of bias-correction accelerated percentile (BCa) are listed in

Table 7. Based on the

p-values, the estimated coefficients for indirect, direct, and total effects are significant in bootstrapping process with BCa.

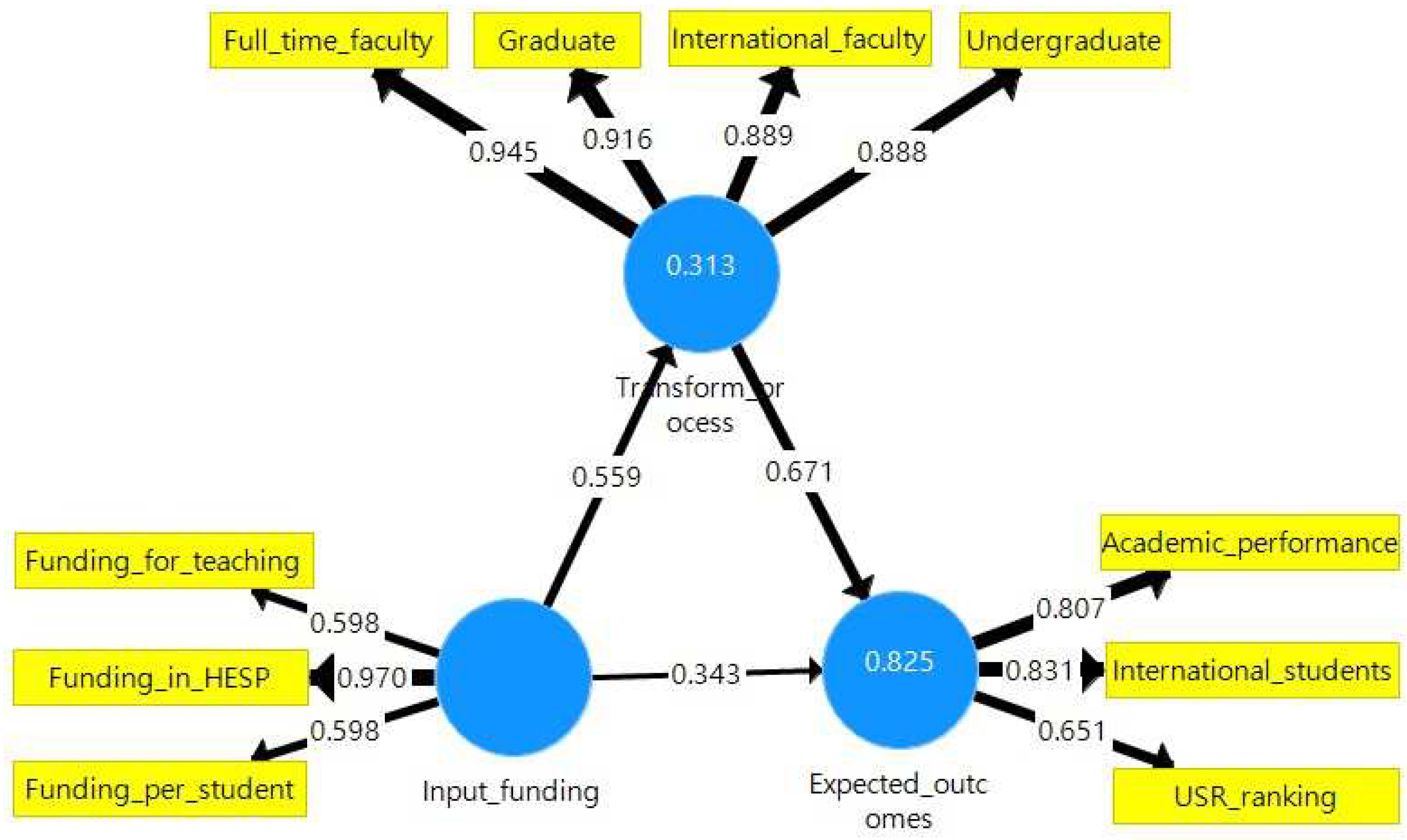

4.8. Verifying the Effect of Private Sector by PLS-SEM

Considering the effect of funding allocation in private sector, we employed PLS-SEM to verify the transformation process. The result of PLS-SEM indicated that Cronbach alpha in input funding, transformation process and expected outcome are 0.811, 0.931, and 0.651, respectively. The model demonstrates the AVE are 0.522, 0.827, and 0.588 in input funding, transformation process and expected outcome, respectively. The composite reliabilities are 0.771, 0.950 and 0.808 in the model. The findings suggest that the testing model for private sector transformation public goods are fitted.

Figure 4 shows the weighted regression coefficients and path diagrams in the model. The transformation process in private sector works well.

5. Discussion

Previously enhanced quality and introduced teaching excellence programs in Taiwan are based on the competitive mechanism [51]. The adverse effects have been reported, for example, over-emphasized the evaluation and the requirement of accountability in a short period [65]. Studies from the perspectives of students and teachers indicated that universities receiving Teaching Excellence Program grants failed to meet their expectations [66,67]. It is why the HESP was initiated. Can public goods work well in higher education with a series of policy-driven reforms in neoliberal contexts? In the beginning, the HESP considered targeting the quality of higher education institutes and balancing institutional excellence and caring the quality teaching for disadvantaged students. A specific fund from HESP is offered for all higher education institutions instead of a competition scheme. In addition, this study found that the expected outcomes are academic performance and international student recruitment, whereas the impact of USR is still limited. In SEM testing, the findings suggest that the initial funding provided by HESP can impact the expected outcomes through the transformation process. The mediation effect of the transform process is significant in the proposed model. Compared with previous policy initiatives, the most significant change in the HESP is implementing USR. The USR consists of strengthening university-industry collaboration, fostering cooperation among universities and high schools, and nurturing talents required by local economies. In the long run, the influence of USR projects will increase in higher education. In this sense, HESP provides an example to demonstrate that USR could be a crucial factor in the model.

In this study, we also raised two crucial questions: How wide is the gap in the funding allocation in HESP between the system and sector for public goods? What are the influential factors for funding allocation in the HESP? HESP encouraged higher education institutes to promote teaching innovation by enhancing learning effectiveness and teaching quality to reduce inequality. Based on the effect of funding allocation, this study found that some issues are emerging in the HESP. First, the HESP aims to secure students' equal rights to access quality and diverse higher education systems. Suppose the equal rights to access higher education should reflect no significant difference in their funding allocation for institutes. While the funding scheme reveals that the institutional scale needed to reflect the funding allocation properly, the gap between universities and private technological universities or colleges has existed. This example may provide an alert to related policy good initiative in higher education. Funding for public good implementation should consider sector balancing in higher education. Fortunately, the result of SEM confirm the transformation process works well in both sectors.

Second, this study found that the funding of the HESP for each institute is based on the number of articles in Scopus due to their high relationship in the testing model. The government encourages higher education institutes to propose their institutional projects with unique characteristics. At the same time, the result reveals there is a similar culture on campuses where encouraging article production is persisted. At this point, how to balance teaching and research needed to be considered in next stage of HESP.

In a global context, higher education policies typically have been shown to provide incentives for universities to develop or strengthen their capacity of the academic profession and performance in neoliberal times [2,7,68,69]. Various funding studies have focused on global competition discussions in neoliberal contexts [10,39,41]. In comparison, we have perceived that various studies indicate that the concept of public goods might play a significant role in higher education [11,34,36]. Like the EU agenda for higher education and the new global Education 2030 [4,5], Ireland's National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 and the Dutch National Research Agenda also provide ambitious purposes for public goods in higher education. It may indicate a possible transition within the neoliberal regime from competition-oriented to public goods-oriented systems.

Can significant policy initiatives transform public goods in neoliberal higher education settings? This study provides an empirical example (an ITO model) to evaluate the core values of public goods and their practices in higher education settings. The findings suggest that when higher education is considered from a public goods perspective, the competitive funding scheme should consider the policy's intention and the effect of implementation. Even though the policy intention is evident in this case study, the change still needs to be faster and more predictable in neoliberal higher education contexts. This study agreed that a common good is a collective decision that involves the state, the market, and civil society [30]. Since it is impossible to exclude any individual from consuming the good [27], higher education policy for public good intervention may need adequate resources for long-term support. The study found that current policy intention and short-term funding support could have fit better. It may reflect that the effects are not satisfied for higher education institutes at this stage.

What does this imply for contemporary higher education? As higher education moved into a globally competitive era, the question arose about putting public goods schemes to work in a neoliberal context. Tian and Liu's study indicated that public or common goods also triggered discussions on higher education in China [37]. Huang and Horiuchi addressed the public goods of internationalizing higher education in Japan [49]. Despite the acceptance of the concept of public goods, changes and reforms in the Japanese system has been dominated by demands from business and industry. In general, performance funding is based on an input-output model of services where services are to be financed by government agencies in terms of output indicators. Many European countries have implemented some form of performance-based funding in higher education. For example, implementing Research Performance Based Funding (RPBF) systems aims to improve research cultures and facilitate institutional changes that can help increase research performance [70]. Many EU countries have introduced, are introducing, or are considering introducing such systems. Some positives have been received. Whereas, considering the implementation of public goods, tuition, and fees have traditionally been low in Europe, reflecting the view that higher education is a public good [71]. There are alternative funding schemes to fit various performance purposes in European countries.

Zerquera and Ziskin’s study indicated that performance-based funding requirements interact with the public-serving mission of urban-serving research universities (USRUs) in the USA and can deepen stratification across a differentiated system [72]. Policymakers, institutions, and researchers must work towards synergistic interactions to deepen understanding and vision for a better society. In the initial transformation stage, it is an essential factor that leads the program to success in higher education. Moreover, various studies have focused on how performance-based funding impacts marginalized students [73,74,75,76], with findings across these studies essentially pointing to adverse effects on access for underrepresented students. This study did not find significant evidence to support that HESP positively affects underrepresented students.

Taking HESP as an example, ITO model may provide a holistic perspective to reflect the issues in neoliberal higher education regardless of the public and private sectors. With higher education institutes, the effectiveness of education, research, and innovation can correctly connect to societies. As stated in previous discussions, the private sector does not usually provide pure public goods; therefore, pure public goods in higher education are a minimal phenomenon [48]. In this study, we demonstrate that the effect of specific funding for public goods are significant regardless the sectors in higher education. The example of HESP may provide a more profound understanding of funding allocation for public goods in neoliberal times. Even though the private sector received limited public funds in HESP, the funding-driven policy encouraged all private institutes in this case study.

6. Conclusions

This study took the HESP in Taiwan as an example to test the effect of transforming public goods in neoliberal higher education. The findings suggest that the government initiated the HESP and targeted the quality of higher education institutes in which institutional excellence and caring for disadvantaged students’ learning could balance. Regarding this core issue, the policy managers need continuous discussions between partners to overcome the funding gaps for public goods purposes. The study reveals that public goods can transform into higher education by reshaping what universities expect to do in an uncertain future. This case study may provide a valuable reference when policy design considers theories and practice issues for transforming public goods.

Moreover, this study focuses on the following concerns for higher education: First, reshaping institutional strategies for public goods and promoting strong institutional characteristics for substantive development in the future is necessary. Second, it is crucial to continue balancing academic excellence and quality teaching; commitment to implementing innovative and quality teaching for disadvantaged groups should be the premier institutional strategy for most institutes. Third, higher education institutes should commit to achieving remarkable progress in expanding learning opportunities for all as the initiatives of the UN's SDGs. With fitting funding, higher education can find ways to respond to the challenges of local and global issues. Finally, we know that sustainable higher education is a long-term goal and needs many resources and partners to support it. We hope this case study can provide a helpful example to explore similar issues in higher education settings further.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan. Grant number MOST 111-2410-H-032-031 (from 1 August 2022 to 31 July 2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data transformation is contained within the article. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bottrell, D.; Manathunga, C. Shedding light on the cracks in neoliberal universities. In Resisting Neoliberalism in Higher Education; Bottrell, D., Manathunga, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zepke, N. Student Engagement in Neoliberal Times: Theories and Practices for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education; Springer: Singapore, Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DES. National strategy for higher education to 2030. Department of Education and Skills. Available online: http://www.hea.ie/sites/default/files/national_strategy_for_higher_education_2030.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a renewed EU agenda for higher education (COM/2017/0247 final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52017DC0247 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- UNESCO. Rethinking Education: Towards a Global Common Good? UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelkorn, E.; Gibson, A. Public goods and public policy: what is public good, and who and what decides? High. Educ. 2019, 78, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olssen, M.; Peters, M.A. Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: From the free market to knowledge capitalism. J. Educ. Policy 2005, 20, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frlie, E.; Musselin, C.; Andresani, G. The steering of higher education systems: A public management perspective. High. Educ. 2008, 56, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottrell, D.; Manathunga, C. Shedding light on the cracks in neoliberal universities. In Resisting Neoliberalism in Higher Education; Bottrell, D., Manathunga, C., Eds.; . Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ergül, H.; Cosar, S. (Eds.) Universities in the Neoliberal Era; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eryaman, M.Y.; Schneider, B. Evidence and Public Good in Education Policy, Research and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE). Submission to the productivity commission inquiry into the National Education Evidence base. Available online: http://www.pc.gov.au/_data/assets/pdf_file/008/199574/sub022-education-evidence.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- AERA. Research and the public good statement. Available online: http://www.aera.net/Education-Research/Research-and-the-Public-Good (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Ministry of Education. Higher Education Sprout Project (final version); Ministry of Education: Taipei, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. The review report of higher education sprout project (2018). Available online: https://www.edu.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=9E7AC85F1954DDA8&s=8365C4C9ED53126D (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand. Funding allocation model. Available online: https://www.msd.govt.nz/what-we-can-do/providers/building-financial-capability/funding-allocation-model.html (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Bower, J. Resource allocation theory. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management; Augier, M., Teece, D.J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1445–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, P. Planning Theory, 3rd ed.; Palgrave Macmillian: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal, B. Planning in theory and in practice: Perspectives from planning the planning school? Plan. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 251–275. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Planning Theory and Urban and Regional Dynamics: A Comment on Yiftachel and Huxley. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2001, 24, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, T. Reviving Critical Planning Theory; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yiftachel, O. Huxley, M. Debating dominance and relevance: Notes on the ‘communicative turn’ in planning theory. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00286(accessed on August 2023).

- Damib, A. Educational planning in theory and practice. In Educational planning and social change: Report on an IIEP seminar; Weiler, H.N., Ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1980; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sevier, R.A. Strategic Planning in Higher Education: Theory and Practice; CASE Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, C. The planning research agenda: Planning theory for practice. Town Plann. Rev. 2011, 82, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarais-Tremblay, M. On the definition of public goods. Assessing Richard A. Musgrave’s contribution. Documents de travail du Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00951577/document (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Musgrave, R.A. Provision for social goods. In Public Economics: An Analysis of Public Production and Consumption and Their Relations to the Private Sectors; Margolis, J., Guitton, H., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1969; pp. 124–144. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbridge, J. On the contested nature of the public good. In Private Action and the Public Good New; Powell, W., Clemens, E., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pusser, B. The role of public spheres. In Governance and the Public Good; Tierney, G., Ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, USA, 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Daviet, B. Revisiting the principle of education as a public good, Education research and foresight series, No. 17. UNESCO. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-theinternational-agenda/rethinking-education/erf-papers/ (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Nixon, J. Higher Education and the Public Good: Imagining the University. Bloomsbury: New York, USA, 2011.

- Locatelli, R. Education as a public and common good: reframing the governance of education in a changing context. UNESCO Education Research and Foresight Working Papers. No 22. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002616/261614E.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Marginson, S. The public/private divide in higher education: a global revision. High. Educ. 2007, 53, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Higher education and public good. High. Educ. Quart. 2011, 65, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Higher Education and the Common Good; Melbourne University Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva, P.; Ilieva-Trichkova, P. From conceptualization to measurement of higher education as a common good: challenges and possibilities. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Liu, N.C. Rethinking higher education in China as a common good. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowski, K. The common in higher education: a conceptual approach. High. Educ. 2019, 78, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Carasso, H. Everything for Sale? The Marketization of UK Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H. A. Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education; Haymarket Books: Chicago, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell, B.; Kauppinen, I. (Eds.) Academic Cpitalism in the Age of Globalization; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Munch, R. Academic capitalism. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-15 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Slaughter, S.; Rhoades, G. Academic Capitalism and the New Economy: Markets, State and Higher Education; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, S.; Considine, M. The Enterprise University: Power, Governance and Reinvention in Australia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.; Lamont, M. (Eds.) Social Resilience in the Neoliberal Era; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, L.; Slaughter, S. Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies and the Entrepreneurial University; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reale, E.; Primeri, E. Reforming universities in Italy. In Reforming Higher Education: Public Policy Design and Implementation; Musselin, C., Teixeira, P., Eds.; . Springer: London, UK, 2014; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bacevic, J. Beyond the third mission: toward an actor-based account of universities’ relationship with society. In Universities in the Neoliberal Era; Ergül, H., Cosar, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Clam, Switchland, 2017; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Horiuchi, K. The public good and accepting inbound international students in Japan. High. Educ. 2019, 79, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Outcomes of ATU (2017). Available online: http://moe.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=7122&ctNode=713&mp=1 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Tang, C.W. Creating a picture of the world class university in Taiwan: A Foucauldian analysis. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljandali, A. Multivariate Methods and Forecasting with IBM SPSS Statistics; Springer: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, J. Odds ratio: Formula, calculating & interpreting. Available online: https://statisticsbyjim.com/probability/odds-ratio/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Cheng, E.W.L. SEM being more effective than multiple regression in parsimonious model testing for management development research. J. Manage. Dev. 2001, 20, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Marcelo, G.; Vijay, P. AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Braz. J. Mark. 2014, 13, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, J.C. Latent variable models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Equation Analysis, 4th ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associate: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Erlbaum Associate: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1987, 82, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R. J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chang, D.-F. Exploring international faculty’s perspectives on their campus life by PLS-SEM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.P.; Wang, L.-T. Who benefits from the massification of higher education in Taiwan? Chinese Educ. Soc. 2012, 45, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, D.-F.; Yeh, C.-C. Teaching quality after the massification of higher education in Taiwan. Chinese Educ. Soc. 2012, 45,5-6, 31-44.

- Chang, T.-S.; Bai, Y.; Wang, T.-W. Students’ classroom experience in foreign-faculty and local-faculty classes in public and private universities in Taiwan. High. Educ. 2014, 68, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codd, J. Selected article: educational reform, accountability and the culture of distrust. In Critic and Conscience: Essays on Education in Memory of John Codd and Roy Nash; Openshaw, R., Clark, J., Eds.; NZCER Press: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Jones, A. Knowledge Capitalism: Business, Work and Learning in the New Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers, K.; Zacharewicz, T. Research Performance Based Funding Systems: A Comparative Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, M. Performance-based funding, higher education in Europe. In The International Encyclopedia of Higher Education Systems and Institutions; Teixeira, P.N., Shin, J.C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Germanny, 2020; pp. 2227–2231. [Google Scholar]

- Zerquera, D.; Ziskin, M. Implications of performance-based funding on equity-based missions in US higher education. High. Educ. 2020, 80, 1153–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Jones, S.; Elliott, K.C.; Owens, L.; Assalone, A.; Gándara, D. Outcomes Based Funding and Race in Higher Education: Can Equity be Bought? Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017.

- Kelchen, R. Do performance-based funding policies affect underrepresented student enrollment? J. High. Educ. 2018, 89, 702–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbricht, M.R.; Fernandez, F.; Ortagus, J.C. An examination of the (un)intended consequences of performance funding in higher education. Educ. Policy 2017, 31, 643–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagood, L.P. The financial benefits and burdens of performance funding in higher education. Educ. Eva. Policy Anal. 2019, 41, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).